Part I

I never imagined my daughter’s first birthday would end in sirens and handcuffs, or that a seven-year-old in a purple unicorn dress would be the bravest person in the room. But if there’s one thing teaching third grade has taught me, it’s that kids know exactly when to step up—usually the minute the adults forget how.

I’m Bethany—thirty-two, lover of picture books and construction paper, and the kind of mother who thinks a party theme deserves a spreadsheet. I married Trevor three years ago, and if kindness could be a job, he’d have tenure. He came with Willow, a quiet-eyed four-year-old who hid behind his legs the first time we met and asked, in a voice like a secret, if I knew how to braid hair like Elsa. I learned that night. I’ve been learning ever since.

Hazel arrived after a pregnancy that took my breath away and then took my bed—three months on strict rest with more daytime television than I thought a human brain could absorb. She came out with Trevor’s dark hair and my stubborn chin, and I looked at her and understood the phrase heart outside your body. Today was her first birthday, unicorn-themed by popular demand (Willow, mostly), and I’d been planning it for weeks. Pink-and-gold bunting swayed along the fence. Tissue-paper pompoms dotted the ceiling like pastel planets. A bubble machine waited on the back patio like a promise.

But there was a shadow in my house and her name was Geraldine.

My mother-in-law is the kind of woman who uses “dear” like a dagger and color-codes her pantry. She retired from a bank at fifty-eight, but you’d never know it—spreadsheets rustle when she walks by. From the first dinner we shared—“a public school teacher,” she’d said, as if I’d announced a criminal record; “and still paying student loans at twenty-nine?”—I’ve been a project she didn’t authorize and therefore couldn’t endorse.

Trevor’s father, Dennis, learned long ago that silence is the cheapest kind of peace. He’s sixty, lives in golf polos, and has perfected the faraway stare of a man who always has a tournament to get back to. He’s not unkind. He’s… absent, like furniture that’s been in the same place so long you forget what it’s for.

I had three goals for the day: keep Hazel happy, keep Willow close, and keep Geraldine from detonating the room. Two out of three, I thought, and we could call it a win.

By 7:00 a.m., the kitchen smelled like vanilla and my nerves. The cake—three layers of hand-beaten buttercream, a fondant unicorn with a gold horn I’d dusted with edible shimmer until it glowed—sat on a pedestal in the dining room, a monument to sugar and maternal overachievement. I’d piped tiny pink roses along the side and written HAPPY 1ST, HAZEL in my best kindergarten teacher cursive, which is to say, immaculate.

My sister, Fiona, arrived at eight with coffee that could resurrect the dead and a hug that did the rest. She’s twenty-nine, a pediatric nurse with a mouth that only tells the truth, and if I could pack a person for emergencies, it would be her.

“Your shoulders are up by your ears,” she said, handing me a mug.

“Balloons are at proper jaunty angle. Fruit platters are… Instagram is calling.”

“Geraldine’s coming, isn’t she?” Fiona asked, pretending it was a question.

“She’s Trevor’s mother,” I said. “I can’t not invite her to Hazel’s first birthday.”

“You’re a saint,” she said. “I would’ve banned her after the Christmas Incident.”

The Christmas Incident is how we refer to the year Geraldine gifted Willow a DNA kit “for fun—to see your heritage,” as if the subtext weren’t screaming. Willow had looked at me, then Trevor, then the box, then me again. I made hot chocolate and pretended not to hear my heart crack.

Today will be different, I told myself. Enough is enough.

My parents arrived at eight-thirty, right on time and carrying so much joy the house pressed out to make room. Mom smelled like lavender and love. Dad hauled in a stuffed elephant roughly the size of a compact car.

“Our first grandbaby’s first birthday,” Mom said when I protested the sheer volume of gifts. “We absolutely did have to.”

“Hazel’s going to think the elephant is her ride home,” Dad said, kissing my forehead. He retired last year from the police department and has never once let a bully slide on principle.

Willow sailed into the kitchen in her purple unicorn dress, hair in a ribboned braid we had achieved together after three attempts and a minor breakdown (mine). She rotated for compliments, accepted them solemnly, and asked, “Mommy, can I help with anything? I want everything perfect for Hazel.”

“You can be the Candle Boss,” I whispered, touching the tip of her nose. “When the time comes, you put it in place.”

Her eyes lit like someone turned on a room behind them. “You trust me with the special job?”

“I trust you with everything,” I said, and meant it.

By midmorning, the house murmured with happy chaos: neighbors balancing paper plates, my colleague Rachel arriving with an ungodly good spinach dip, Trevor’s cousin James carrying in a cooler, children turning the living room into a town with invisible rules. Trevor moved through it all—hauling chairs, fixing the bubble machine, double-checking the playlist—with the kind of competence that made me want to marry him again in the backyard, right then, flowers or no.

He appeared in the doorway with his phone. His face did a thing like weather changing. “They’re twenty minutes out,” he said.

Twenty minutes. I had twenty minutes before Geraldine imported her climate.

I used them like a person who knows the apocalypse is scheduled: topped off the punch, re-fluffed the pompoms, rechecked the unicorn’s angle on the cake (“It’s a cake, Beth, not Versailles,” Fiona said, but then adjusted it anyway), kissed Hazel’s fat cheeks until she squeaked, and reminded myself: This is her day. No one takes this from her.

The Mercedes eased to a stop at the curb at exactly the minute the text predicted. Of course it did. Geraldine exited in a black sheath dress and pearls, like she was attending a board meeting about my failure. She looked like money and a decision. Dennis followed in khakis and resignation.

“Showtime,” Fiona muttered. She squeezed my hand. “Kill her with kindness. If that fails, I brought sarcasm.”

I opened the door with my biggest hostess smile. “Geraldine. Dennis. We’re so—”

“Where is my son?” she asked, as if I were the concierge.

“In the back, with the bubble machine. Hazel’s in the living room if you want to—”

But she had already swept through, heels clicking across hardwood like a countdown. Dennis lingered just long enough to mumble, “Hey there, Beth,” eyes warm with apology he wasn’t brave enough to spend.

Willow watched Geraldine pass the living room without stopping. “Did Grandma see me?” she asked, puppet still on her hand for the show she was doing for the babies.

“She’s looking for Daddy first,” I said. “Keep doing your show, sweetheart. You’re amazing.”

We both knew the truth: Geraldine didn’t see Willow. Not really. Not even when Willow waved like a flag.

The party reoriented when Geraldine entered the backyard, the way water changes when you drop something heavy into it. Conversation didn’t stop; it softened. Trevor straightened. “Mother,” he said, letting her air-kiss his cheek. “Thanks for coming.”

“This machine is rented, I assume,” she said of the bubble contraption pumping out happiness like a factory. “Seems excessive for a one-year-old who won’t remember any of this.”

“I bought it,” Trevor said. “The kids will use it for years.”

“Wasteful,” she murmured, then turned to the food table. “Caterers? On a teacher’s salary?”

“I made everything,” I said lightly, stepping in with Hazel on my hip. “Would you like to hold your granddaughter?”

Geraldine looked at Hazel the way one looks at a salad one didn’t order. “I’m wearing dry-clean-only,” she said. “Perhaps later.”

Hazel, sweet unoffended bird, squealed and reached anyway. Geraldine stepped back like Hazel was contagious. “She seems drooly,” she observed. “Is she sick?”

“She’s teething,” Trevor said, jaw tightening. “It’s normal.”

What followed was a masterclass in passive aggression, performed without notes. Rachel complimented the decorations. “Pinterest has made party planning so easy even amateurs can manage something decent,” Geraldine smiled. Mrs. Johnson from next door told Hazel she was advanced. “All babies seem advanced to their parents. Reality sets in later,” Geraldine replied, voice full of the charity reserved for people you don’t plan to tip. She “helped” during gifts by narrating every present’s failings: “Overstimulating,” “Below age level,” “Tacky.” The air around her curdled. People adjusted their positions without noticing, the way you lean away from a candle that’s burning too hot.

Willow kept trying. She showed Geraldine the birthday crown she’d made for Hazel—a cardboard miracle bedazzled within an inch of its life. “Mm,” Geraldine said, eyes already elsewhere. Willow offered punch. “I don’t drink anything made by children,” Geraldine said with a laugh that made the sentence sound like a punch line.

“Why don’t you go play with the twins?” I whispered when I saw Willow’s eyes shine. “You can be the boss of the bubble machine.”

“I want to help with the cake,” she said, clinging to me like an anchor. “You promised I could put the candle on.”

“And you will,” I said. “You’re Candle Boss. That job doesn’t get outsourced.”

Dennis had found James and was discussing the moral universe of eighteen holes. Bless him. There are men who hold lines. There are men who hold golf clubs.

Mom, sweet diplomat, tried for common ground. “You must be so proud,” she said to Geraldine, nodding at Willow by the fence teaching the twins to pop bubbles without touching them. “Willow is such a special girl, and now baby Hazel, too.”

“Willow isn’t mine,” Geraldine said, crisp as a receipt. “She’s from Trevor’s first marriage. His actual marriage in a church,” she added, tossing me a lemon, “not some beach ceremony anyone could perform.”

“We are legally married,” my father said, stepping into the line of fire like he was born for it. “And both girls are your granddaughters.”

“Biology matters,” Geraldine said, looking at me as if I were a substitute teacher who’d lost control of the class. “Some connections are real. Others are just… legal technicalities.”

Fiona’s hand found mine under the table and squeezed so hard it hurt. Willow had heard every word. I saw it land and bruise.

“Time for cake!” I sang, too bright, as if volume could reroute the moment. I summoned everyone to the dining room—over the threshold and into my arena. The cake stood gleaming and ridiculous, the unicorn’s golden horn catching sunlight like a small miracle. “Beth, it’s stunning,” Rachel breathed. “Open a bakery, please.”

“A bit much for a baby,” Geraldine said, positioning herself beside the table the way a hawk positions itself above a field. “All that sugar. Though I suppose dietary discretion isn’t a priority in this house.”

Fiona inhaled sharply. I lit the pink candle with a match that trembled, then steadied. Trevor lifted the camera. Hazel clapped at the flame, chanting her favorite word, “Ba! Ba! Ba!” as if she had personally invented birthdays.

We sang. Everyone smiled, even the twins, who had frosting already and didn’t know how. As the last notes wobbled into silence, I leaned in to guide Hazel’s breath over the candle. That’s when I saw Geraldine’s hand move.

It happened fast. It happens forever.

Her palm hit the edge of the cake plate just so—deliberate, a perfect little physics lesson in ruin. The pedestal scraped, the cake tilted, slid, and then the crash: three layers detonating across hardwood, buttercream splattering the wall in a creamy constellation, the unicorn’s horn snapping and skittering under a chair. Pink roses scattered like something abandoned. For a heartbeat, the room was bakery quiet, which is to say not quiet at all, just held breath.

“She doesn’t deserve this family,” Geraldine said into that breath, words sharp as broken sugar. “This child. This whole charade. You trapped my son with your pregnancy, you gold-digging little opportunist.”

Hazel wailed, a sound that split me from sternum to spine. A dozen gasps followed, a chorus of shock. Rachel moved for paper towels. Mom stepped forward like a storm. Fiona’s phone appeared like a weapon. Trevor—my Trevor—stayed frozen, camera still lifted, eyes on his mother like he’d never seen her before.

I looked down at my shoes, frosting-ruined, then up at the cake carnage, then at Willow, whose purple dress was now dappled with pink like a watercolor accident. Her face had collapsed into the kind of grief children aren’t supposed to know. Then, before any of us could move, I watched something quiet and enormous happen behind her eyes. Tears still on her cheeks, she straightened her small shoulders, wiped her face with the back of her hand, and stepped toward Geraldine, voice steady in a way that made the hairs on my arms stand up.

“Grandma,” she said. “Should I show them your secret video?”

The room stopped. Even Hazel hiccuped herself silent. Color drained from Geraldine’s face like someone had pulled a plug. “What are you talking about, child?” she said, but the edge in her voice had gone wobbly.

“The video from last month,” Willow said matter-of-factly, turning toward the living room. “When you were in Daddy’s office. You didn’t see me. I was under his desk in a fort with the tablet.”

“Children make up stories all the time,” Geraldine snapped, the words too fast, the sentence breaking past her teeth. “I was checking email.”

Trevor set the camera on the buffet like it had suddenly become heavy. “Willow,” he said gently, “what video?”

She walked to her backpack by the couch, pulled out Trevor’s old tablet—the one he’d given her for reading and math games and recording dramatic tableaus starring her stuffed animals—and tapped the screen with those small serious fingers. “I was recording myself reading for a school project,” she said. “You came in. You seemed really mad. I kept recording and stayed hidden.”

Geraldine reached. Willow stepped back with the reflexes of a girl who’s learned who and what not to trust. “No,” she said, holding the tablet to her chest. “You’re mean to my mommy. You whisper at her when Daddy isn’t looking and then pretend you didn’t. You made her cry on Mother’s Day.” Her voice cracked and then reassembled. “You said she’s not my real mom. But she is.”

Dennis said, “Geraldine?” in the tone of a man who has finally turned around.

“She’s lying,” Geraldine said. “Kids—”

“Let’s watch it,” Trevor said. His voice was very calm, which scared me more than shouting would have. He crouched to Willow’s level. “Can I hold it, sweetheart?”

She looked at me. I nodded. She handed over the tablet like it was a baby. Trevor kissed her forehead. “You did the right thing,” he whispered loud enough for all of us to hear.

Geraldine lunged. Mark and James—six feet of ethics apiece—stepped into her path.

“I think we all need to see this,” Mark said, steel in his tone.

Trevor turned the volume up. The screen showed his office from a low angle, the view you’d get if you were small and hiding under a desk. We saw Geraldine’s legs first—sensible heels, control in motion—then heard drawers opening. Her voice filled our house, familiar and suddenly horrifying.

“Trevor’s too naïve to protect himself,” Recording Geraldine said. “That girl probably poked holes in the condoms to get pregnant. Well, I’m not letting another gold digger take my son for everything he’s worth.”

I felt Mom’s hand find my arm. Fiona sucked in a breath that sounded like she’d been hit.

On the video, Geraldine opened a locked drawer, pulled out a small notebook—Trevor’s passwords—and flipped. “Retirement, checking, savings, portfolio,” she murmured. “Perfect.” She photographed each page with her phone, then sat at Trevor’s computer and began to type.

“Fifty thousand should do for now,” her voice said conversationally. “Small enough transfers that Trevor won’t notice immediately. Large enough to build a safety net. I’ll tell him it’s for his own protection.”

My father moved closer to the screen, not as Dad but as Detective, retired but still alive to the law. “That’s identity theft,” he said quietly. “Wire fraud. Embezzlement.”

The video cut to a voice memo: “March fifteenth. Successfully accessed Trevor’s accounts. Transferred fifteen from retirement, twenty from savings, fifteen from investments. Trust account now has fifty protected from that parasite. Next month, another twenty.”

“Protected?” Rachel whispered, disgusted curling her mouth. “From who? Her own delusions?”

Trevor’s face crumpled and then hardened into something I hadn’t seen before. “You’ve been stealing from us,” he said, voice breaking and then leveling. “From our children.”

“I was protecting you,” Geraldine snapped, mask off, claws out. “Just like I protected you from that waitress who trapped you the first time.”

“Don’t you dare talk about Shannon,” Trevor said, and the way he said it told me stories I hadn’t asked for. “She left because of you. Because you were always there, always judging, always—” He swallowed. “I was too blind to see what you were doing.”

Willow tugged my dress. “There’s more,” she said, a tremble under the plainness. “From last week when Mommy was at the school for conferences.”

“What more could there be?” Rachel said, then immediately looked like she wished she hadn’t asked.

Willow tapped the screen. A new video. Hazel’s nursery. The crib, white and peaceful. Hazel sleeping, a fist near her ear, lashes dark on her cheeks. Geraldine leaning over her like a nightmare in silk.

“You don’t deserve the family name,” Video Geraldine whispered to my sleeping baby. “You’re probably not even Trevor’s. Your mother’s nothing but a cheap opportunist who saw a software engineer and dollar signs. But don’t worry, Grandma’s making sure you won’t inherit what doesn’t belong to you.”

The room broke.

Mom surged forward. Dad held her by the shoulders with hands that had kept people from worse mistakes. Fiona was already on her phone, voice clipped, deadly: “Yes, we need officers. We have video evidence.”

“How dare you,” I said, and my voice surprised me—quiet, yes, but steady the way bridges are steady. “How dare you stand over my baby’s crib and pour poison into the air where she sleeps.”

“Everything I did was out of love,” Geraldine said, which is what people say when they mean control.

“Call the police,” Trevor said to my father. He didn’t look at his mother. “I want her arrested.”

“You wouldn’t,” Geraldine said, and for the first time since I’d known her, she sounded unsure.

Dennis spoke, finally choosing a side, his voice sounding older than it had an hour ago. “He would,” he said. “And he should.”

Sirens live under everything in this country; you just have to call them. Fiona did. While we waited, while the videos replayed in whispers across phones, while the children were shepherded into the backyard by saints disguised as neighbors, while Hazel hiccuped and then sighed asleep against my chest, while my heart pitched between fury and the kind of grief that eats spoons, Willow stood beside me like a sentry, small and straight and fierce, her hand warm in mine.

When the doorbell rang, Dad showed the officers his retired badge and then the videos. They took notes. They asked questions. They put Geraldine in handcuffs. She tried everything—denial, tears, threats, nostalgia—but none of it stuck to the moment.

“You’ll regret this,” she said to Trevor as they led her out.

“The only thing I regret,” he said, “is not seeing you sooner.”

The door closed. The house exhaled. For ten seconds, no one moved. Then the world flooded back in—neighbors with trash bags, Rachel grabbing her keys (“Sheet cake emergency!”), James right behind her (“I’ll drive!”), Mrs. Johnson directing a clean-up crew with the authority of a woman who’s balanced toddlers, dogs, and a marriage through three house moves. The ruined cake was swept, the frosting mopped, the unicorn horn rescued and placed gently on the counter like a fallen soldier waiting for the right ceremony.

We sang Happy Birthday again, this time around a grocery-store rainbow, and it was perfect because Hazel squealed and smeared purple frosting across her cheeks and Willow—oh, Willow—held the candle with both hands, set it straight, and blew out that light with her sister, face tilted up like a prayer answered.

That night, after the last dish and the last text and the last child asleep, Trevor and I sat at the dining table and opened our accounts. The numbers told a story ugly and precise—eighty-seven logins in eight months, transfers that started small and grew bold. Seventy-three thousand dollars. Gone.

“How did I not see it?” he kept asking, the question punching holes in the air.

“Because she was your mother,” I said. “We don’t look for knives in the hands that held us. Not until they cut.”

He cried. I did, too. Then we made a plan.

And in her bed down the hall, our seven-year-old hero slept with chocolate on her lip and glitter in her hair, her small tablet charging on the nightstand like a medal.

Part II

In the morning, the house smelled like cold buttercream and lavender detergent, the ghosts of yesterday mingling like two people who don’t know whether to hug or shake hands. Hazel woke up singing to herself as if yesterday had been nothing but a nap between presents. Willow padded into the kitchen in dinosaur pajamas and climbed into my lap like she was six again and the world made more sense at that height.

“Do we have to see Grandma today?” she asked, small voice, big eyes.

“No,” I said, meaning it the way doors mean it when they latch. “You don’t have to see her at all.”

She nodded, relieved and guilty at once, the double helix of children who think loving and protecting are always supposed to be the same thing. “Okay,” she said. “I’m Candle Boss forever, though, right?”

“Forever,” I said, and she grinned into my sweatshirt.

Trevor shuffled in, rumpled and hollowed out the way sleep hollows out someone who bumped into grief on the way to bed. He kissed Hazel’s head, kissed Willow’s, kissed my temple and lingered.

“I kept seeing it,” he said into my hair. “Her hand. The plate sliding. The… everything.”

“We’re going to make a plan,” I said. “We do the boring heroic stuff. We call the bank. We call your HR. We call the detective. We shore up the floor.”

He half-laughed, a sound made of apology and relief. “I love when you sound like a teacher.”

“That’s because teachers fix the world with staplers and lists,” I said, reaching for a pen. “Step one: breakfast. Step two: lock the money doors.”

By nine, my father had texted the name and direct line of the detective assigned—Morales—and a checklist that made my nervous system purr: file incident report numbers, upload video evidence to the secure portal he linked, freeze suspicious accounts, contact the bank’s fraud division, contact Trevor’s HR to put a note on his file that his accounts had been compromised by a family member. “Family member” was such a tidy way to say someone you once trusted opened your drawers and rifled through your life.

At ten, we were at the bank. The lobby’s quiet was the expensive kind, designed to whisper, You’re safe here, your money is safe here, nothing bad happens between marble and brass. The branch manager, a woman with unflappable hair and a nameplate that said S. Koenig, met us with a smile that was twenty-five percent empathy, seventy-five percent protocol.

“I’m so sorry you’re experiencing this,” she said to Trevor after we showed her the video and printed statements. “We’re going to secure your accounts and escalate to our fraud investigation team. We’ll also place a note on any profiles associated with your social security number. If anyone attempts movement, we’ll know.”

Trevor signed forms with the intense concentration of someone learning a new alphabet. I signed where a spouse signs because the law likes its ducks in rows and its jurisdictions tidy.

“Do you have two-factor authentication enabled?” Koenig asked gently.

“I did,” Trevor said, cheeks flushing the color of shame. “I turned it off because my mother… she kept getting locked out when she checked her investments on my computer. It was a temporary—”

He stopped. The sentence looked at itself and sat down.

“It’s okay,” Koenig said, tone not quite maternal but in the neighborhood. “We’re going to set up hardware keys today. They’re annoying in the way seatbelts are annoying.”

We left with a folder of words that were going to help—freeze, alert, restore, investigate—and a baggie of small gray keys on lanyards that looked like toys and could make thieves cry. Boring heroism, Part I.

At noon, Detective Morales called. Her voice was brisk without being cold, like someone who has seen everything and still refuses to shrug. “I’ve watched the videos,” she said. “They are… clear. We’ve already flagged the trust transfers. We’ll be coordinating with the DA. We’ll also put in a seizure request to freeze whatever’s left in that trust.”

“What happens to Hazel’s college fund?” Trevor asked, and his voice cracked on our baby’s name the way a bridge cracks when you learn it was built with the wrong bolts.

“We’ll work it,” she said. “I can’t promise timing, but the paper trail here is helpful. I also need statements from both of you. And from your father, if he’s willing.”

“He’s willing,” I said, surprising myself with my own certainty. The Dennis from yesterday had stood up. I had to let him keep standing.

At two, Trevor’s HR director—Darlene with the kind eyes and the wicked laugh at holiday parties—called to say they’d flagged all internal access. “You’d be surprised how often it’s family,” she said softly. “I’m sorry. Let me know what documentation you need from our end for the DA.”

By three, the group text labeled FAMILY (Geraldine’s creation, of course) began belching smoke. Cousin Lorraine: “This is being blown out of proportion.” Aunt Meg: “Bethany should have kept the peace for the baby’s sake.” Uncle Marty, who once called me “pretty smart for a teacher”: “Trevor, you don’t put your mother in jail.”

Trevor typed for a long time, deleted for a longer time, then handed me the phone. “I want to say something that doesn’t set the whole forest on fire,” he said.

He typed again: We are not discussing this here. There is a legal case. We have video evidence. Any messages excusing theft or harassment will be screenshotted and forwarded to our attorney and the detective. There is a five-year no-contact order pending. Respect it. We will not be attending family gatherings. We will not be fielding calls on this topic. Do not contact Bethany or the girls. This is the only statement you’ll get. -T

He hit send. The typing bubbles appeared—outrage takes no time at all to draft—and then disappeared. Dennis messaged privately: Proud of you, son. I’m here. Whatever you need.

At four, there was a knock. I opened the door ready to fight and found Dennis on the step with a paper bag full of groceries and a face wrenched into something like humility.

“I didn’t know what to bring,” he said. “So I brought spaghetti.”

“You brought the entire national meal of recovery,” I said, letting him in.

He put the bag down and pulled an envelope out of his pocket, thick like it attached itself to debt and wanted to die a hero. “This is… restitution,” he said, the word careful and heavy. “From my personal account. With interest. I’ve already filed for divorce.” He swallowed. “Forty years I told myself peace was worth anything. Turns out it wasn’t even peace.”

Trevor stared. Then he took the envelope, then his father’s hand, then pulled that man into an embrace so sudden it looked like they had both tripped into it. “Thank you,” he said into the polo. “For not looking away.”

Dennis nodded into his son’s shoulder. When he let go, he turned to Willow, who had been watching from the kitchen island, chin in her hands like a jury of one.

“I’m sorry,” he said to her. The words staggered a little, unused to coming out. “I should have protected you from her. I should have made her stop. I… didn’t. I’ll do better.”

Willow looked at him in that long, careful way children have when they are measuring you for real. “Okay,” she said. “Do you want to play chess later?”

He blinked. “I… do. I’d like that.”

After he left—after the spaghetti simmered into something that made the house smell like Sundays—Fiona arrived with a stack of Tupperware and her nurse voice. “Okay: hydration, nutrition, one thousand deep breaths, and here’s the number for a child therapist whose entire superpower is teaching quiet kids how to use their loud voice without setting themselves on fire.”

Willow listened with interest. “Do I have to draw my feelings?” she asked.

“Only if you want,” Fiona said. “Also, the waiting room has an aquarium.”

“I’ll go,” Willow said immediately. “I want to tell someone with a fish.”

Hazel threw a noodle onto the floor and laughed like she’d reinvented gravity. The sound slid into all of us like light.

The arraignment was three days later in a courtroom that smelled like coffee and consequences. Geraldine wore gray and a mouth that had learned something about closing. Her attorney—a man so polished he reflected—argued that the transfers were “protective actions,” that my video was “taken without consent,” that my stepdaughter’s recording was “inadmissible,” that my husband had “granted implied access.” Detective Morales’s affidavit and the bank’s logs and the trust paperwork sat on the judge’s desk like three brick walls.

“I am not making findings today,” the judge said, bored and excellent. “But I am making conditions. No contact with the victims for five years pending resolution. No access to any accounts. Surrender passports. Stay away from the residence and place of employment. Understood?”

Geraldine nodded once, twice, the way people nod when they think the right answer might be yes.

When the bailiff called the next case, the gallery exhaled as one organism. In the hallway, reporters hovered, sniffing for drama. We passed them by like a storm passing a diner.

“Do you feel vindicated?” one called after us.

“No,” I almost said. “I feel like my baby’s cake hit the floor and I can’t get the buttercream out of the baseboards.” Instead I said, “We feel grateful for the process.”

“Who taught you media answers?” Trevor laughed in the elevator, forehead to mine.

“Third grade,” I said. “You think PTO moms aren’t press?”

If a life breaks, you don’t glue it together with big gestures; you use small ones over and over until it holds. The week after court, the neighborhood showed up with casseroles and offers to walk our dog we do not have. Mrs. Johnson organized a do-over birthday for Hazel: same theme, smaller guest list, more laughter, absolutely no pearls.

“I’m making a cake,” I told Fiona the night before. “Not a three-layer masterpiece. Just… a cake that tastes like choosing joy.”

“Make two,” she said. “For the part of you that still wants to throw one at a wall.”

We baked side by side like we were sixteen again and learning yeast’s moods. Willow sifted flour with the concentration of a surgeon. “This one is armor,” she said, tapping the bowl. “So the cake can’t be pushed.”

“It’s going to be on a low table in the backyard,” I said. “No pedestals. We’ll surround it with people.”

“I like that plan,” she said. “People armor.”

We iced the cake with thick swirls that looked like clouds and wrote HAZEL IS TWO!! in slightly crooked purple, which is my favorite font. Rachel arrived early with confetti cannons we never fired, because the sunlight did that job better. Mark fixed the bubble machine like he was disarming a bomb. James set up a playlist labeled “Happy on Purpose.”

Dennis brought Hazel a wooden puzzle chest with shapes you have to learn to unlock. “I thought she could start practicing,” he said. “For a world that sometimes tries to keep her out.”

Hazel, wearing a tutu and a grin large enough to be illegal, opened the chest and immediately put a triangle in a circle hole, then laughed like she’d been waiting all day to fail publicly. Willow clapped, the first into every joy.

We sang. Willow placed the candle with both hands again. Hazel made a sound like a steam engine and the flame went out. Everyone cheered for absolutely no reason and all the best ones.

After cake, Willow tugged Dennis toward the chessboard we’d set up on the porch. He sat. She arranged white. He played black. Her opening was aggressive and charming. His defense was patient and proud. I snapped a photo—not for social media, not for a future courtroom, just for the small altar of ordinary miracles I was building in my phone.

Later, when the backyard was nothing but crumbs and a half-deflated unicorn pool float, Trevor and I sat on the steps and watched the girls chase dusk. Hazel toddled in circles squealing “Ba!” every time a bubble kissed her, which was far too often; the machine was drunk with success. Willow pretended to catch the sun in her hands and put it in her pocket.

“I hate that she did this here,” Trevor said, eyes on the spot on the dining room wall where a faint smear of frosting lived under new paint. “In our house. Where we’re supposed to be safe.”

“It’s the right place for the truth to out,” I said. “Houses should hear the truth. Then the walls can hold it.”

He was quiet a long time. The air did that pink-orange thing that makes you forgive a day its rudeness. “I should have seen it,” he said finally, not looking at me. “All of it. For years.”

“You were a son,” I said. “Sons want their mothers to be better than they are. That doesn’t make you blind. It makes you human.”

He turned. “You didn’t say I failed you.”

“You didn’t,” I said. “Not when it counted.”

He reached for my hand and for a moment we were the two people on the beach again, Willow throwing petals and wind grabbing my veil, promises easy because we didn’t know how hard promises can be. I squeezed. He squeezed back.

Inside, my phone buzzed: a text from Ms. Carter, Willow’s teacher. I saw Willow’s “birthday cake splat” drawing during quiet time. We sat with Ms. Patel, and she told the story like a journalist. We talked about helpers. She said, “I was a helper.” I told her yes. Just wanted you to know you are raising a truth-teller.

I showed Trevor. “She saved us,” he said, reverent. “A seven-year-old with a tablet.”

“She saved herself first,” I said. “That’s where all good saving starts.”

The legal machine is a glacier, but this one moved with surprising speed. Geraldine’s attorney requested a plea deal eight weeks after the arraignment. Detective Morales called me on a Wednesday in May while I was helping my students glue popsicle sticks into “bridges” that wouldn’t pass any inspection but love.

“She’s willing to plead to identity theft and fraud, drop the rest,” Morales said. “Restitution is already in process thanks to Dennis. Probation, community service, mandated counseling, and a five-year no-contact. You’ll have input at sentencing.”

“Do you need a statement?” I asked, already thinking in paragraphs. You can take the girl out of an essay, but you can’t take the essay out of the girl.

“I do,” she said. “Tell the court what the cake didn’t show.”

At night, after Hazel fell asleep with frosting in her hair (again) and Willow pretended to be asleep but was just reading by flashlight (again), I sat at the dining table—the scene of the crash, the scene of the second singing—and wrote. I wrote about the cake and the whispered poison over a crib and seventy-three thousand dollars that were supposed to be future books, future braces, the future itself. I wrote about a seven-year-old shaking and then standing, about a marriage that had to learn to breathe without a woman who kept closing windows, about a family that discovered you can love someone and still ask the state to step in.

At sentencing, the courtroom was less full and more honest. Geraldine looked smaller. That was new. The judge read my statement aloud for the record, voice devoid of drama in a way that let every sentence do its own work. When he reached the line, “My mother-in-law taught me that protection without respect is control; my daughter taught me that truth without cruelty is courage,” he paused, and in that pause I hoped the words might climb into someone else’s pocket for later.

The judge issued two years probation, three hundred hours of community service, restitution credited by Dennis’s check, and a five-year no-contact order. He recommended counseling. He recommended time away from spreadsheets. He recommended “learning to be a mother to your adult son by becoming the kind of person he would choose as a friend.”

When we left the courthouse, the sky had the clarity of a screen wiped clean. Dennis stood on the steps waiting. He looked ten years older and five pounds lighter and like a man who had finally set down a bag he didn’t realize he’d been carrying since college. He hugged Willow first. “Teach me your new opening,” he said. She did, on the hood of our car, chess pieces clacking like applause.

The school year ended the way school years do: messy, sweet, too fast and somehow not fast enough. My class performed a reader’s theater version of Charlotte’s Web that made three parents cry and an entire row of eight-year-olds ask, “Is death like a nap?” and I said, “No, it’s like a book closing. But sometimes there’s a sequel.”

On the first Friday of summer, we held Hazel’s “Two and a Half” party because Willow decided it sounded like important math. The cake was small and round and defiant. The unicorn horn sat upright. Willow placed the candle. Hazel blew and screamed victory. Trevor kissed me in front of everyone like a teenager in a movie who learned something about priorities.

After the guests left, Dennis stayed behind and washed dishes at my sink like he’d trained for it. “I start therapy next week,” he said to the plates. “A man named Brian who looks like a washer repairman and talks like a third base coach. I think he’s going to make me cry.”

“Good,” I said. “You have forty years to wring out.”

He smiled into the suds. “I’m sorry,” he said again, not as penance anymore, but as punctuation. “And thank you.”

“For what?” I asked, handing him a towel.

“For letting me start over here,” he said.

We all were.

That night, when the house was finally quiet and the dishwasher hummed its soft apology for not being human, I stood in the dining room and looked at the wall that had once bloomed buttercream. If I squinted, I could still see a faint pink smear under the paint, a whisper of sugar and rage. I pressed my palm to it like a blessing and then turned off the light.

In bed, Willow crawled in between us like a punctuation mark—an em dash of a person connecting two clauses that thought they’d have to stand alone. Hazel snored in her room like a small bear with big plans. Trevor slid his foot along the sheet until he found mine, a ritual we invented when the world was ordinary and kept when it wasn’t.

“We’re okay,” he murmured. “We’re better than okay.”

“We’re ours,” I said, and slept.

Part III

Summer came early like it had been waiting in the driveway, engine running. School ended with paper crowns and popsicle-stained smiles, and I packed away bulletin boards the way a person folds a map after learning the roads by heart. Hazel discovered her elbows and the word “mine,” added to her vocabulary with the solemnity of a judge. Willow graduated from first grade with a certificate that said “Most Observant,” which felt like the universe taking notes.

The house felt different. Not just safer—lighter, as if the windows had learned to lift themselves. The financial restoration dripped in like a leaky faucet that, for once, did not make me hate plumbing. The bank untangled accounts. Detective Morales emailed updates every other week in sentences that were both dry and heroic. Dennis came by on Tuesdays to lose at chess to Willow on purpose and by accident. Trevor started therapy on Thursdays, returning home a little quieter and a little more present, like he had set something down in an office with a soft rug and good lamps.

We practiced boring heroism. Hardware keys on lanyards. Locked drawers with nothing in them. Password managers. A framed list by the front door that read in Willow’s careful block letters: We do not open the door for guilt. We do not feed shame after midnight. We say “no” like we’re watering a plant.

The letter from the court arrived in June. The plea was official. Probation laid out like a contract with decency. No-contact order stamped in ink that looked startlingly cheerful for something so serious. “Do you need to frame it?” Fiona asked, only half joking. I tucked it in a folder labeled “Family Safety” and put the folder on the highest shelf. I didn’t need to look at it to believe it. Belief had moved into the house and started paying rent on time.

On a humid Tuesday, we met Ms. Patel, the child therapist Fiona had recommended. Her waiting room had an aquarium big enough to count as the ocean and a basket of squishy toys that looked like stress relief learned to glow. Willow sat with her knees together and her hands in her lap like she was at a fancy restaurant.

“Do you want to draw your feelings?” Ms. Patel asked once we were in her office, a room made of soft colors and sturdy furniture.

“Sometimes,” Willow said. “But sometimes I want them to use their words.”

Ms. Patel smiled in the way of grown-ups who are very good at listening. “We can do both,” she said. “We can make your feelings bilingual.”

They built a vocabulary together: stone stomach, sparkle proud, lava mad. They made a “brave plan” for moments when past and present tried to switch places without permission. It was simple and perfect: three breaths, one truth, a boundary. Willow picked a small blue stone from a bowl to carry in her pocket on hard days. “This is my No Stone,” she told me in the car, turning it over in her palm. “I’ll rub it and remember I don’t have to let people in.”

We made August plans the way you make summer plans with children: big, adjustable, with snack breaks. One Saturday, we drove to the beach where Trevor and I had been married, the “embarrassingly casual” ceremony that had somehow held up under storms. The pier had had a paint job. The ice cream shack had a new sign. The water did what it always does: kept going without needing us to narrate.

“Do you think we should do it again?” Trevor asked quietly, the two of us watching Willow teach Hazel how to throw a shell in so it made two plops.

“Get married?” I pretended shock. “To you?”

He grinned, white-sand smile I married on purpose. “Say the words again,” he said. “But this time, with our house listening.”

He meant a vow renewal. He meant a ritual not because the first one didn’t count but because sometimes you plant a second tree beside the first to make more shade.

We did it a month later, late afternoon so the heat could soften into something that felt like a blessing. Fiona officiated with a printed script that made her tear up at the part where she listed the boring heroics as sacred acts. Rachel brought cupcakes and paper napkins that said “YES” in gold letters. Mark wrangled a Bluetooth speaker into pretending it was a string quartet. Dennis wore a tie that looked surprised to be invited to the beach. A handful of friends stood in the sand with bare feet and generous hearts. Hazel wore a white cotton dress with a strawberry juice stain like a medal. Willow wore purple, because the world is better that way, and had a new job title on a pin she had made herself: CANDLE BOSS. She kept touching it with two fingers, like checking if bravery is still there when you’re not looking directly at it.

Trevor took my hands. A wave went shyly up the sand and then back down, as if it had miscounted. “I married you before I understood what it would require,” he said, voice shaking a little and therefore perfect. “Now I know. I promise to hear you first and defend you fast. I promise not to confuse keeping peace with keeping quiet. I promise to be your partner with my mouth and my spine.”

“I married you before I learned the shape of what we’d carry,” I said. “I promise to tell you the hard truth and not punish you for listening. I promise to build doors we can lock without locking each other out. I promise to love you out loud in front of our girls.”

We exchanged nothing expensive. Rings were already in place, history already written on skin. Willow stood between us for the kiss, cheeks cranked up to max happiness, holding a single tea light she’d insisted on. “You can kiss now,” she announced, and blew the tiny flame out herself. My favorite kind of tradition was born: the Candle Boss always gets the last say.

After, we ate cupcakes with the same intense focus we had exchanged vows, which is to say, properly. Hazel fell asleep on Dennis’s chest, frosting in her hair a second time this summer. On the drive home, Willow hummed to herself in the backseat, a song that sounded like a kitchen window open in spring.

One morning in late September, I received an email with the kind of subject line that makes you sit down: Consent to Adoption. It was from a law office in Los Angeles. For a second, the room got both bigger and smaller, like grief and hope had bumped into each other.

Shannon.

Trevor read over my shoulder. “It’s from her attorney,” he said, searching my face as if he could keep anything too sharp from landing. “She wants to talk. About… rights.”

We had never told Willow much about Shannon beyond the kind truth: that she had loved her and left when she couldn’t stay, and that sometimes adults break promises not because the person isn’t worth it but because they can’t meet a promise and still breathe. We didn’t villainize. We didn’t saint. We named the quiet.

Shannon and Trevor spoke first on the phone without me, because history deserves a hallway to itself before it walks into the living room. When he hung up, he sat with me on the couch, elbows touching, shoulder to shoulder the way you sit when you’re waiting for a wave to decide whether it’s going to be gentle.

“She’s sober,” he said. “Three years. She’s in therapy. She saw… everything.” He meant the articles, the court records that are public whether you want them to be or not. “She says she can’t give Willow what she needs from a mother. She wants to sign consent for a step-parent adoption. She wants to do it kindly. She asked if she can write a letter.”

We told Willow together that night. We used language that had practice and love and caution braided into it. “Shannon wants to make the thing that is already true… true on paper,” I said. “If you want that.”

Willow thought a long time, head tilted, eyes doing their measured inventory. “She can write a letter,” she said. “I want to read it. Then I’ll decide.”

Shannon’s letter was three pages handwritten in a looping script that tried very hard not to look like regret. She didn’t apologize for leaving. She apologized for the silence, which is a different and sometimes more important apology. She wrote a paragraph about Willow as a baby that made my chest ache—specifics that proved love had existed: the way she hiccupped at exactly seven minutes into every nap, the triangle birthmark under her left shoulder blade, the way she put her toes on the bar of the highchair like a tiny queen on a footrest. She wrote: I was drowning. I thought running was breathing. I was wrong. You deserved someone who knew the difference. You have her now. If you want Bethany to be “Mom” on paper I will carry the emptiness of that line with pride if it makes your home feel truer.

Willow read it twice. She touched the paper like it might be a cat that would spook if you moved too fast. Then she said, “Okay.”

We did the paperwork. There is, it turns out, a lot of it when you are adopting a child you have already been mothering for years. Background checks. Home visits. A fire extinguisher check that made me laugh in a way that startled the social worker and then made her laugh, too. “I know,” she said, pointing her pen at me like we were co-conspirators. “Forms for love. Bureaucracy is how the state tries not to fail people. It fails anyway. But sometimes it works.”

Adoption day was scheduled for a Tuesday morning in October. Courtrooms look different when the docket is joy. The judge had a drawer of stuffed animals. He came down from the bench to shake Hazel’s hand like she was someone whose vote he wanted, and gave Willow a sticker that said SUPER SIBLING. Dennis wore that surprised tie again. Fiona brought a bouquet of pencils because she knows paper is my love language. Rachel took photos in which no one blinked. Ms. Patel patched in on FaceTime so Willow could hold up her No Stone in a court of law like a talisman and a thesis.

The judge asked Willow if she wanted to say anything. She cleared her throat and did, because of course she did. “I have two moms,” she said, steady as a lighthouse. “One who made me. One who stays. I want the staying one to be my mom in the government, too.”

“So ordered,” the judge said, tapping his gavel once in the way you tap a page to draw attention to your favorite line. Hazel clapped because everyone else did. I cried for a clean thirty seconds and then again at random intervals for the rest of the day.

We had pancakes after, because pancakes are how Americans absorb joy. Willow poured the syrup like a scientist and announced she wanted to hyphenate her last name, “so the past can walk next to the present without pushing.” Trevor kissed the top of her head and said, “You can call yourself Willow Sunshine Pancake if you want; you get to choose your own story.”

That night, Willow gave me the Candle Boss pin to keep “for emergencies,” and I put it in the jewelry box with the bracelet my grandmother left me and the ring I don’t wear to work because glue sticks have opinions. I lay in bed and wondered if a body could be too full of gratitude. It felt like holding a warm bowl in winter. It felt like every window open without a draft.

If life were a movie, that would be the last scene before the credits. But there was one more chapter the story wanted to write, the kind with fewer fireworks and more maintenance—my favorite kind now that I know its value.

In November, Riverside Elementary held its first “Helpers Assembly,” an idea Ms. Carter and I cooked up in the copy room when the laminator jammed in a way that made us philosophical. “We do fire drills to practice leaving,” she said. “We should do hero drills to practice staying.”

We invited community helpers—nurses and librarians and a mail carrier whose route included our school and whose smile included everyone. Detective Morales came in a blazer that made the kids whisper “cool jacket” and spoke about telling the truth without making the truth mean you don’t love someone. Dennis came, too, at Ms. Carter’s invitation, his hands shaking and his posture not. He told the kids that sometimes the bravest thing you can do is admit you were wrong and then do right so loudly you can hear it from the other room.

I stood behind the curtain with the third graders while the second graders sang a song about kindness that would be ridiculous if it didn’t make ten adults cry. Willow stood in the wings, purple dress (of course), Candle Boss pin like a tiny lighthouse. She didn’t want to speak on stage, and we didn’t ask her to. But when the assembly ended, and everyone started to file out and the cafeteria smell reasserted itself from the far end of the building, she tugged Detective Morales’s sleeve and said, “Thank you for believing the video, even though I’m small.”

“I didn’t believe the video because I’m a detective,” Morales said, kneeling to be eye to eye. “I believed the video because you were brave. My job is to notice bravery.”

Willow nodded solemnly as if she had just been inducted into a club with good jackets.

On the way out, a grandmother I didn’t know stopped me at the door. “My daughter is going through a divorce,” she said, sweating grief. “Her mother-in-law is… something else. Today helped. I didn’t know we were allowed to name things out loud.”

“We are,” I said. “We are allowed to name everything.”

The first snow fell a week before Thanksgiving, fat flakes that made the town look like it had put on a sweater. Hazel pressed her hand to the window and said “Mine” to every snowflake. Willow built a fortress in the front yard and declared it a Boundary Castle where only people who knew the password could come inside. The password was NO. She taught the twins from next door to say it with their whole bellies and then giggle like the world might just work out after all.

On Thanksgiving morning, we cooked the bird and the pies and the green beans like we were auditioning for a family the Pilgrims would have wanted to visit. Dennis carved. Fiona basted and roasted and narrated like a sports announcer. Rachel set a table so pretty the mashed potatoes straightened their posture. We went around and said what we were grateful for, which always sounds cheesy until it’s your actual life.

“I’m grateful for boring heroism,” Trevor said.

“For No Stones,” Willow added, holding hers up.

“For naps,” Hazel announced, then promptly took one in the middle of the floor.

“For people armor,” I said, looking around the table at exactly that.

Dennis cleared his throat. “For second starts,” he said. “And for a house where the doors are clear.”

After dinner, after dishes and football and someone falling asleep with a napkin on their chest, I stood in the hall and looked at the spot on the dining room wall where the buttercream stain used to be. You couldn’t see it unless you knew. I knew. I pressed my palm to the paint anyway, the way I had that night, the way I might for years to mark the place where something bad happened and something good started.

We still get mail for her sometimes—charity solicitations, alumni newsletters, catalogs that think they know her size. We mark them return to sender. We light a candle on Hazel’s birthday and let Willow blow it out like a benediction and a shield. We keep the hardware keys on their lanyards by the door and the passwords in a manager that insists we be more complicated than we want to be. We leave the no-contact order on the high shelf.

And when the world is too loud, or my chest is too full, or the past does that rude thing where it tries to sit in the front seat again, I make pancakes. I call Fiona. I read. I look at a photo on the fridge of four people on a beach and a tiny candle between them, flame just about to go out because a girl has decided it’s time for cake.

The worst day of my daughter’s first year tried to take our house. It failed. It made us better. It made us careful in ways that feel like love. It gave a seven-year-old the chance to be heard and a sixty-year-old the chance to be new and a thirty-two-year-old the right to say no into her own kitchen until it sounded like yes to the life standing in front of her.

Family is not the people who can ruin a party and call it protection. Family is the people who pick up a broom, a phone, a pen, and each other.

When people ask me now—the way strangers do online, the way other teachers do in break rooms, the way the clerk at the hardware store did when he saw the lanyards on my keys—if it was worth it to bring the truth into the light, I think of Willow saying, “Should I show them your secret video?” I think of Hazel squealing at a store-bought cake like it was manna. I think of Trevor holding our daughters and saying, “This is my family.” I think of Dennis learning to lose at chess with deep, honest joy.

“Yes,” I say. “Yes, and.”

Because the truth didn’t just save us. It taught us how to keep being saved, one ordinary, brave, boring day at a time.

— The End —

News

Cheating Wife Packed Her Stuff And Said, You Didn’t Want To Open Our Marriage So I’m Taking The Kids… CH2

Part I At twenty-seven, I thought my life was a line you could draw with a straightedge. Career in a…

At The Work Party, My Pregnant Wife Leaned Over To Her Boss & Said, “He’s My Work Husband,… CH2

Part One: Love doesn’t survive splinters. It can live with dents and scratches and a cracked tile or two, but…

My mom slipped a gold necklace into my 15-year-old daughter’s bag and got her ARRESTED for shoplifti… CH2

Part One: The bench outside the juvenile intake room was too small for any grown-up to sit on without looking…

I Inherited a Stranger’s House by Mistake. The Real Heir Changed My Life Forever… CH2

Part I I was halfway up a ladder in the back of Murphy’s Hardware, stripping rotten trim from a second-story…

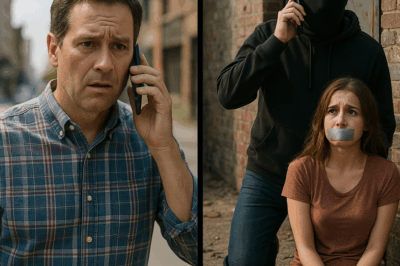

A trafficking ring took my daughter and told me to forget her, They didn’t know who I was… CH2

Part I The morning sun spilled into my kitchen as if it had someplace important to be. It turned the…

My Nephew Came Through a Snowstorm Carrying a Baby: “Please Help, This Baby’s Life Is in Danger!… CH2

Part One: The wind battered Harry Sullivan’s old farmhouse as though the storm had a grudge against him personally. Snow…

End of content

No more pages to load