I was shrugging on my coat for Sunday dinner when my phone buzzed like a hornet trapped in a jar.

Three missed calls from Gerald, my attorney.

Then the text that made my blood run cold:

Tom, call me now. Don’t go to your daughter’s house. I mean it.

I froze in my foyer with one sleeve halfway up my arm, the late-afternoon light cutting across the hardwood like a warning flare. My daughter Lindsay had been unusually insistent this week. Dad, you never come over anymore. The kids miss you. I’m making your favorite pot roast—just like Mom did.

How do you say no to that?

I set the coat back on the bench like it had turned to lead and sank onto the leather couch my late wife, Margaret, and I had picked out three decades earlier—back when we were still renting and thought a good sofa could make a home. She’d known what to do in a crisis. Margaret always had. But she’d been gone four years, and I’d been feeling my way through this new world alone.

My thumb found Gerald’s contact. The call connected on the second ring.

“Tom,” he said. His voice was tight, professional, but I heard something underneath it—concern, maybe even fear. “Where are you right now? Are you alone?”

“I’m at home,” I said. “What’s going on? You’re scaring me.”

“Good. Stay there,” he said. “Lock your doors. I’m coming over. There are documents you need to see with your own eyes.”

He hung up. I stared at my phone for a beat, then did as told—bolting the front door, sliding the chain across, checking the back slider even though we live in a quiet part of Denver where the biggest threat most days is a teenager blasting music at a stoplight.

Twenty minutes later, Gerald was at my dining table, dropping a manila envelope and a laptop like he was staging an evidence exhibit. He’s sixty, fit, silver hair that makes juries trust him on sight. We’ve known each other since the company softball league back when I was a petroleum engineer working the DJ Basin and he was a kid in the DA’s office learning how to sink his teeth into a case.

He took a breath, slid a stack of papers toward me, and said the words that made the room tilt.

“Three days ago, your daughter Lindsay and her husband Derek filed a petition in Denver District Court—probate division. They’re asking the court to declare you mentally incompetent. They want guardianship and conservatorship. In plain English, they want to control your medical decisions and take over your assets.”

For a second, my ears filled with a high-pitched ring like altitude sickness. “That’s… insane,” I said. “I’m sixty-seven, not ninety-seven. I do the Sunday crossword in ink. I renew my driver’s license on time. I volunteer twice a week at the food bank and manage my own investments.” My voice was rising without my permission. “Why—why would they do this?”

Gerald opened the laptop and angled the screen toward me. “Because of this.”

There it was, a tidy spreadsheet and a set of screenshots that made my life look like a balance sheet. The house I’d lived in for thirty-two years in Hilltop, bought when Margaret and I were young and stretching every dollar, was now worth about $2.4 million. The retirement portfolio I’d built through market dips and oil shocks and a hundred nights staring at SEC filings was around $1.8 million. Pensions and savings brought the total north of five.

“I knew I was comfortable,” I said, hearing my voice like it belonged to somebody else. “Margaret and I—we worked hard, saved, didn’t… blow it.” I couldn’t make my mouth say spent. “Lindsay joked last Christmas that I was ‘sitting on a gold mine.’”

“It wasn’t a joke,” Gerald said. He tapped another tab. “Your daughter and Derek are in financial trouble. Heavy mortgage on a house in the outer suburbs—Cherry Hills Village, five-bedroom beast with a three-car garage. They’re paying private-school tuition for your grandson Josh: thirty-eight a year. Property taxes are a small fortune. And Derek put a chunk of money into a crypto venture with a business partner. They lost almost four hundred thousand.”

My neck went hot. “How do you even know all this?”

“Because they attached their finances to their petition,” Gerald said. “They framed it as justification for protecting your estate from your supposed decline. But it reads like motive.”

He pulled out a new stack of papers. “Tom, they’ve been building a case for six months.”

He showed me photos of me at the grocery store looking at a shelf like I’d never seen cereal before. That day, I’d been trying to find the exact brand Margaret used to buy—the one with the cluster of oats she swore kept my cholesterol in check. He showed me a note from our family doctor, Dr. Patel, stating I’d been “disoriented” during an annual exam. That day, I’d had a head cold and forgot whether I’d already taken the blood pressure pill that morning. He played an audio clip where I hesitated before giving my cell number—I’d switched providers the week before and kept defaulting to the old digits I’d had for twenty years.

Every ordinary moment of aging twisted into a narrative of incompetence.

“This is fraud,” I said. It came out hollow, a whisper with no roof over it. “This is elder abuse.”

“Yes,” Gerald said. “And it’s more common than people think. Adult children don’t always wait until a parent dies to go after money. Guardianship petitions weaponized as estate grabs—that’s a thing now.”

He clasped his hands like he was about to deliver bad medical news. “The hearing is in fourteen days. They moved fast, probably hoping to catch you flat-footed.”

“What happens if they win?”

He didn’t sugarcoat it. “They control your accounts. They control your house. They can sell it. They can place you in assisted living, consent to medical procedures you don’t want, limit who you see. You’d lose autonomy.”

I pictured the house—the scratch marks on the pantry door where we measured Lindsay’s height every September, the soffit Margaret made me paint three times because the first two whites weren’t “friendly” enough, the upstairs bedroom where Margaret took her last breath with my hand in hers. The idea of strangers staging it with rental furniture and an espresso-scented candle made my throat close.

“They can’t do this,” I said. “Lindsay wouldn’t…”

“I’m sorry,” Gerald said gently. “But the record suggests otherwise.”

I thought back to my minor fender-bender last spring—a teenager ran a red light near 6th Avenue and clipped the front end of my car. The police report made it clear I wasn’t at fault. Still, Lindsay had insisted on coming to follow-up appointments. She took notes on her phone while I talked to doctors. I’d thought, sweet kid, looking out for her dad. Now I saw the angle.

“What do I do?” I asked. The words felt like sand in my mouth.

“We fight back,” Gerald said. The concern in his eyes didn’t change, but something sharpened around the edges—a litigator’s gear shift. “But Tom, I need to know if you’re ready. This won’t be clean. This will put a crater through what’s left of your family.”

I saw Lindsay at five in a pink jacket with a missing button, falling off her bike and launching herself into my arms before the bruise even bloomed. I saw her at twenty-two in her mother’s wedding veil, laughing through her tears. I saw her last week asking if I could come for pot roast.

Tell me what we need to do.

Gerald nodded once—like he’d been waiting for that—and smiled the way a professional smiles before he steps into a fight he thinks he can win.

“First,” he said, “we document everything. Starting now, you keep a detailed daily log. What you do, choices you make, who you talk to, what you read, what you decide—not a diary; evidence. Timestamps. Screenshots. Receipts. You do your crosswords in ink? Keep them.”

I nodded.

“Second, we get an independent geriatric psychiatric evaluation by a specialist—someone respected, with courtroom experience. Not your family doctor—no offense to Dr. Patel—but someone who owes nothing to anyone. We’re looking for clear cognitive testing and a formal report.”

“Fine.”

“Third—and this is the hard one—you don’t let them know you know,” he said. “You keep every plan you’d already made. You respond like normal. You don’t sound rattled. If they sniff we’re onto them, they’ll change tactics, accelerate, or destroy evidence.”

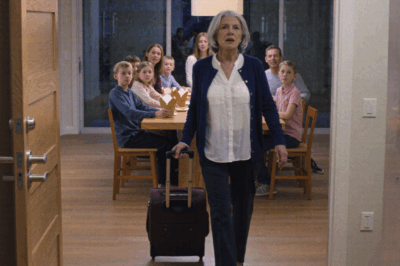

My mouth went dry. “That dinner invite tonight—”

“Best-case, they wanted you to sign something under the guise of ‘estate planning.’ Worst-case, they planned to manufacture an incident—turn a small moment of confusion into a performance for the camera. Either way, you’re not going.”

He slid a legal pad toward me. “Start the log now.”

I wrote: 5:42 p.m.—Received emergency call from attorney Gerald R. Sanders instructing me not to go to daughter Lindsay’s house. Stayed home.

That night, I wrote pages: the time I turned on the evening news, the decision to make a chicken salad instead of ordering takeout because I wanted to keep sodium low, the impulse I fought to pour a whiskey and instead made tea. It felt silly and it felt necessary. If I learned anything in forty years of engineering, it’s that a paper trail can save you when someone starts rewriting reality.

Monday morning, Gerald called with an appointment. “Dr. Sarah Chen. Top of her field. She can see you Wednesday and Friday and wrap the testing by next week.”

Dr. Chen had the calm, disarming presence of someone who has ushered hundreds of families through storms and knows exactly how to keep both the truth and the patient intact. She asked me to remember lists, draw intersecting shapes, subtract by sevens—then switched to tougher tasks that felt less like games and more like a stress test. She probed judgment, reasoning, executive function. She asked about grief and sleep and routine. By the end of the second session, I was emotionally wrung out and oddly grateful, like someone had finally flipped on the fluorescent lights in a room where I’d been told to stumble in the dark.

On Friday afternoon, she called me into her office and delivered the kind of verdict you wish had a drumroll. “Mr. Morrison,” she said, “I can state with confidence that you show no signs of cognitive decline. In fact, your testing performance is above average for your age group. Memory, attention, executive function—they’re not just intact, they’re strong.”

Outside on the sidewalk, I sat on a low concrete wall and laughed for the first time all week. I texted Gerald a photo of the report cover page and then walked two extra blocks to buy myself a scoop of mint chip, just because.

The hardest part was pretending with Lindsay. On Wednesday she called with a voice sugar-coated to the edge of brittle.

“Dad, I’m so sorry about Sunday,” she said. “Derek’s mom had a fall—complete chaos. Can we reschedule for this weekend?”

“Of course, sweetheart,” I said, and hated the way my mouth formed sweetheart like I was borrowing the word from a stranger. “Is she okay?”

“Oh, she’s fine,” she said. “You know how dramatic she can be.” She laughed that laugh I used to adore on her—musical, quick. “Actually… while I have you—Derek and I wanted to talk to you about setting up a trust. For estate planning, just to make sure everything’s organized in case… well, you know, we’re not getting any younger.”

There was a small silence. I could almost hear Derek off-screen, stage-directing.

“That sounds like a good idea,” I said, even. “Let me think about it.”

“Don’t think too long, Dad,” she said lightly. “These things are time-sensitive. You never know what might happen.”

Was that a threat? A nudge? A thoughtless cliché? I couldn’t tell anymore.

That night, my grandson Josh called. Fifteen, tall, still a little coltish in the way he stood—elbows out, feet too big for his body. He’s a good kid. At least I’d always thought so.

“Grandpa Tom, can I come over?” he said. His voice was breathless, like he’d run to a payphone in a seventies movie even though kids now live glued to their screens. “I need to talk to you. Alone.”

“Of course,” I said. “Is everything okay?”

“I don’t know,” he said. “I just need to see you. Please.”

He showed up twenty minutes later on his bike, cheeks flushed. He looked like he wanted to be brave and like his bravery might come apart if I touched it wrong.

“Grandpa,” he said, standing in my kitchen with his helmet dangling from his fingers, “you have to promise not to tell Mom and Dad I told you.”

My stomach dropped. “What is it, Josh?”

He pulled out his phone, hands shaking. “I heard them talking last week. They didn’t know I was home. I—” He swallowed, shame and fear tied in the same knot. “I recorded it. I know that’s… wrong. But I thought you should hear.”

He hit play.

The kitchen filled with my daughter’s voice. “Hearing’s in two weeks,” Lindsay said briskly, like she was discussing carpools. “Gerald Morrison might be his lawyer, but we’ve got Dr. Patel’s note and the photos. We have a pattern.”

Then Derek’s low rumble: With what? We’ve been systematic. Every time he forgot something. Every missed appointment. The judge will see cognitive decline. Even if he fights, it will cost him hundreds of thousands. By the time it’s over, there won’t be much estate left anyway. And if we win—when we win—the house goes on the market immediately. Even in this market, we should clear one point eight after the mortgage. That covers the crypto loss. Then we liquidate his investments, pay off ours, set up the trust for Josh—

“What about your dad?” Lindsay said. There was a pause, and then her voice came back, colder than I’ve ever heard it. There’s a lovely assisted-living facility in Aurora that’s half the cost of where he is now. He’ll be fine. He won’t even know the difference soon enough.

Josh was crying, tears slipping down his cheeks like he was embarrassed to be a person in front of me. “I’m sorry,” he whispered. “I didn’t know what to do. I love you. And they were talking like you don’t—like you’re—” He couldn’t say alive. He couldn’t say real.

I pulled him into a hug. I smelled sweat and the faint bite of grass and the laundry detergent my wife used to buy because it “smelled like clean on purpose.” This boy had done what adults don’t—looked at what he didn’t want to see and chosen right anyway.

“You did the right thing,” I said into his hair. “You did exactly the right thing.”

I sent Gerald the audio file. He called me on speaker while Josh sat at the counter demolishing the emergency pizza I’d ordered because feeding a teenager is the fastest way to stop a panic spiral.

There was a long silence when the recording finished. “Tom,” Gerald said finally, voice flat with something like fury held steady, “this changes everything. This is intent. This is motive. This is conspiracy. We don’t just defend—we go on offense.”

“What does that mean?”

“It means we file a counterclaim,” he said. “Fraud. Attempted financial exploitation of a vulnerable adult—yes, I know you’re not vulnerable; the statute phrase is the statute phrase. Civil conspiracy. We ask for sanctions. And we make sure the court understands this isn’t a messy family disagreement. This is a calculated attempt to strip you of rights and assets. With this tape and Dr. Chen’s report, we have a story that makes sense. Judges like stories that make sense.”

He paused. “Also, from this minute forward, Josh doesn’t go back there unless you say so. His safety matters.”

I looked at Josh. “You can stay tonight,” I said. “Tomorrow, we’ll talk more.”

He nodded like a swimmer who’s just made it to the wall.

The next fourteen days were a crash course in a world I never wanted to enroll in. I wrote my log like it was a job. I started each day by reading the paper and recording a decision I’d made: Chose to donate to the food bank this morning; compared last year’s giving to this year’s budget; decided to match Margaret’s annual number. I kept grocery receipts and noted why I bought what I bought: Picked low-sodium broth; want to keep blood pressure steady without adding a diuretic. It felt absurd, and yet—there was a quiet dignity to it, too. The recognition that autonomy is something you can demonstrate in a thousand small ways. I’d spent my career proving out ideas with numbers and notes and tests; now my life was the prototype under review.

Josh came over after school every day that week and “accidentally” left a hoodie and a physics notebook on my dining table. Saturday, he “forgot” his Xbox controllers. Sunday, he asked if he could do his laundry here because “your washer is faster.” I nodded each time and pretended I believed the story he needed me to pretend to believe.

On Tuesday night, as I was cleaning up after dinner, Lindsay called. Her voice was tight with annoyance dressed as concern.

“Dad, we haven’t seen you,” she said. “You didn’t come Sunday. Is everything okay? Derek says you’ve been… distant.”

“I’m fine,” I said. “Been busier at the food bank. We’re training new volunteers.”

“You didn’t forget your medication again, did you?” she asked. Casual, like a lion strolling by a herd of zebra.

“I’m fine,” I said again, and then, because I couldn’t help myself: “How are you, sweetheart?”

She missed a beat. “We’re great,” she said. “I just worry about you. Hey—Derek says his friend can do your taxes this year. Cut your bill in half. You should let him.”

“I already filed,” I lied, making a mental note to put a sticky on the fridge: CALL RICHARD—TAXES—MOVE UP APPOINTMENT.

We went to court on a bright morning that couldn’t decide if it wanted to be spring or lie about it. I wore the navy suit I’d bought for Margaret’s funeral and had only pulled out since for weddings and graduations. Josh sat beside me in a too-small blazer he refused to shed even though he was sweating through his undershirt. Across the aisle, Lindsay and Derek sat with a man I recognized from a billboard off I-25—Probate Problems? Call Calvin! His tie cost more than my first car.

Judge Maria Rodriguez took the bench with the controlled weariness of someone who has seen enough human drama to last three lifetimes and still shows up because the law is supposed to make order out of it.

Lindsay’s lawyer went first. He stood and painted me as a tragedy in slow-motion, the kind of story that makes people nod about the ravages of time. He held up photos. He cited Dr. Patel’s note. He presented a notebook of “incidents” with tabs and dates and a title Lindsay must have printed at Staples: Dad’s Memory Concerns. He used words like pattern and decline and for his own good.

Gerald stood when the judge nodded at him and slid Dr. Chen’s report onto the lectern like a magician laying down the card you never saw him pull from his sleeve.

“Your Honor,” he said, crisp. “We submit Dr. Chen’s evaluation, completed last week. Dr. Chen is board-certified in geriatric psychiatry, has testified in more than fifty guardianship cases, and found no cognitive impairment. In fact, Mr. Morrison’s performance exceeded norms. Memory, concentration, judgment—sound. The best evidence of capacity is performance. He has performed.”

The judge read in silence for a long minute. I didn’t breathe.

Gerald continued. “Next, we’d like to address the so-called incidents. The grocery store photograph—Mr. Morrison was searching for a brand his late wife preferred; he took extra time. The doctor’s note—the day in question, he had influenza with a fever of 101. The phone number confusion—he had changed providers the week before after twenty years with the same number. Troublesome if chronic, perhaps. But isolated and explained, they do not rise to incompetence.”

He let that hang there just long enough.

“And lastly, Your Honor, we submit evidence of the petitioners’ motive and method.”

Calvin-from-the-billboard objected on reflex—foundation, authenticity—but Gerald had laid the groundwork. A custodian affidavit from Josh. A chain of custody. A hash value to show the file was unaltered. I don’t understand half of what that means, but the judge did.

Gerald pressed play.

It sounded worse in a courtroom than it had in my kitchen—the words uglier against the high ceilings and the weight of the seal over the bench. House goes on the market immediately. Liquidate the investments. He won’t even know the difference soon enough. Derek’s voice came through like gravel run through a tumbler; Lindsay’s like ice snapping.

When the audio stopped, you could hear the fluorescent bulbs hum.

“In short,” Gerald said, voice level, “this isn’t a case of a loving daughter trying to protect a father in decline. This is a calculated attempt to seize control of a living man’s assets—by manufacturing a narrative, manipulating medical records, and turning ordinary forgetfulness into a diagnosis. The petitioners are in severe financial distress. That distress is their motive; this petition is their tool.”

Calvin popped up like a jack-in-the-box. “Your Honor, this so-called recording—setting aside its questionable provenance—was obtained without my clients’ knowledge or consent. It is inadmissible under Colorado wiretap law—”

“In a criminal case, perhaps,” Judge Rodriguez said, cutting him off without looking away from the file on her bench. “But this is a civil guardianship proceeding. The rules of evidence are looser, and I am, to put it mildly, interested in context.” She turned her gaze to Lindsay. “Ms. Fletcher—would you like to explain why you were discussing your father’s assets as if they were already yours to dispose of?”

Lindsay’s lips parted. For a second, I thought she’d tell the truth, that she’d leap at the one thin thread left and say I panicked or we made mistakes or we were scared. But she looked at Derek’s lawyer instead, and whatever she saw there closed something in her face.

“That clip is out of context,” she said. “We were talking about hypothetical estate planning. Dad keeps… forgetting things. We just want what’s best.”

“Hypothetical estate planning that includes putting your father in assisted living in Aurora and selling his home of thirty-two years,” Judge Rodriguez said. Her voice didn’t rise. It didn’t need to. “Ms. Fletcher, I have presided over these proceedings long enough to recognize attempted financial elder abuse when I see it.”

Calvin started to speak again. He didn’t get far.

Judge Rodriguez set the recording aside, removed her glasses, and looked directly at me. “Mr. Morrison,” she said, and the steel in her voice softened around the edges. “I’m sorry this has happened to you.”

She turned back to the petition. “The court finds insufficient evidence to establish incapacity or the need for guardianship or conservatorship. The petition is dismissed with prejudice.” She paused to let the words land. “Furthermore, given the evidence presented, the court enters a two-year protective order. Ms. Fletcher and Mr. Fletcher are prohibited from contacting Mr. Morrison except through counsel and from coming within one hundred yards of his residence. The court also refers this matter to the District Attorney for review of potential criminal charges.” She glanced down at her notes, then up at Lindsay and Derek. “And I award Mr. Morrison his reasonable attorney’s fees and costs. Petitioners to pay.”

The gavel sounded like a door slamming on a bad dream. Then it sounded like a beginning.

Lindsay stood with tears on her face—tears I should have recognized, because I’d wiped them when she was three and scraped her knee and at sixteen when her boyfriend kicked her heart in. But these weren’t the same tears. These were the kind you cry when the thing you tried to steal is snatched back.

“Dad, please,” she said, her voice breaking. “You have to understand.”

I turned and looked at her and felt my heart do the worst thing a heart can do: remember and break at the same time.

“I understand,” I said. “I understand that you were willing to trade me for money.”

Josh’s hand found mine like it had been looking for it for weeks.

Outside, on the courthouse steps, Gerald stood with us in the thin sunshine.

“That was brutal,” he said, no smile. “How are you holding up?”

“I don’t know,” I said honestly. I looked down at Josh. “But I know this: not all family is blood, and not all blood is family.”

He squeezed my hand. “Can we go home now, Grandpa?”

“Yes,” I said. “Let’s go home.”

The day after the hearing, I called Gerald and said the words I never thought I’d say about my own flesh and blood. “I need to update my will.”

“Are you sure?” he asked. “That’s permanent unless you change it back. And if you don’t plan carefully, disinheriting a child can invite challenges.”

“I’m sure,” I said. “And I want the will to be explicit. If she contests, I want any judge who reads it to see exactly why.”

“Then we’ll draft a no-contest clause with a specific statement of reasons,” he said. “And we’ll set up a trust for Josh—education, health, maintenance, support. Make sure he has what he needs without handing him a lottery ticket at eighteen.”

“Good,” I said. “Do it.”

Josh moved in three days later because sometimes there isn’t a graceful way to do what a heart knows. His parents didn’t ask him to leave. They made it impossible to stay. He rode his bike over with a duffel bag and a shoebox of old baseball cards he insisted were going to be worth something someday if I’d just stop throwing them out during spring cleaning. He set the box in Margaret’s old sewing room and said, “Can this be my room?” and my throat closed up because the last time that room had a person in it whose whole future was unwritten was before cancer started leaving sticky notes all over our days.

We built a routine like you build a fence—post by post, level by level, checking the line against the land and the sky and each other. Breakfast together before school: scrambled eggs and toast on weekdays, pancakes on Saturdays because life is too short to pretend you don’t love syrup. Homework at the dining table with Josh explaining physics to me like I hadn’t spent four decades applying math in oilfields because the math looks different when it’s written by a teenager’s hands. Yardwork on Sundays, planting tomatoes where Margaret had kept roses because both require tending if you want them to give you something back.

One Saturday, we installed a small bronze plaque at the edge of the garden—Margaret’s name and dates, and a line Josh found online that made my eyes sting: Family is not always blood. It’s the people who stand by you when everyone else walks away.

“Do you think Grandma would have liked it?” he asked.

“I think she would have loved it,” I said. “And she would have been proud of you.”

Weeks turned to months, and the call finally came: Gerald’s number lighting my phone at 7:12 p.m. when Josh was at the table chewing his pencil over algebra.

“The DA filed charges,” Gerald said. “Attempted fraud. Elder exploitation. They took a plea—suspended sentences, two years’ probation, restitution of your fees. It’s on their record.”

I looked at Josh and felt something I hadn’t felt in a long time that wasn’t grief or anger or fear. Peace, small and stubborn as a sprout in late frost. “Thank you,” I said. “For everything.”

That night, I read while Josh worked, and the house sounded like a home again—pages turning, pencil scratching, dishwasher humming. The kind of sounds that don’t make headlines and don’t trend, but that make a life.

Lindsay tried to reach out once, then again—messages through Gerald that read like apologies written by a PR firm. I didn’t respond. Forgiveness, I told Josh when he asked, isn’t about them; it’s about how you decide not to poison what’s left of your life. Do I forgive what she did? No. Will I set fire to my remaining years keeping score? Also no. I have too much living left to do. And I have a grandson to help me do it.

If you’re reading this and you feel the slow creep of the same nightmare—someone you love building a tidy dossier that reduces you to a liability to be managed—let me tell you what I wish someone had told me sooner: fight back. Get a lawyer who doesn’t flinch. Document everything. Trust your instincts when something you’re being told is “for your own good” tastes like someone else’s payday. Remember that your worth is not a line item and your dignity is not a negotiable term.

And if you’re the adult child of an aging parent and you’re thinking inheritance is just “money early,” hear this from a man who has worked too many years and buried too much love to mince words: your parents don’t owe you anything but what they choose to give. If you try to take it by trick, by petition, by rewriting their story so a judge believes you, you might win dollars for a minute. But you will lose something you will not get back. You will lose yourself.

As for me, I am sixty-seven and learning new things about the world I thought I had already mapped. I have learned that trust is earned, that love is a verb, and that there are worse things than being alone—like being surrounded by people who see you as a vault they’re waiting to crack. I have learned that some days the bravest thing you do is ask for help and the second-bravest is accept it. I have learned that a house can be an investment and an asset and—most importantly—a home, all at once.

In the evenings, when the sun slants across the kitchen Margaret designed with more drawers than anyone needs, Josh sits at the table and tells me about torque and vectors and the way the world turns. I make tea and sometimes hot chocolate because you are never too old for hot chocolate, and we watch the light move across the plaque we put in the garden. The tomatoes are coming in strong. The weeds are stubborn but beatable. The fence is straight. The gate swings without squeaking because Josh learned to oil it without being asked.

Sometimes, when I’m alone by the window and the house is quiet, I let myself think about Lindsay at five again, on that pink bike, the smile before the fall, the fall before the tears, the tears before my arms. I let myself remember the feel of her small hand in mine and the way she curled against my chest when she fell asleep on the sofa during thunder.

Then I let her go.

Because sometimes love is holding on, and sometimes love is refusing to let what someone did to you define what you do next. And because I have a life left to live. And because the person across the table, pencil in his mouth and future in his eyes, needs me to keep moving.

“Hey, Grandpa,” Josh says, looking up from his homework, “what’s the derivative of—”

“Ask your calculator,” I say. “But if you want to talk compound interest, I’m your guy.”

He laughs and shakes his head and looks back down, and I look out the window at the small square of earth that holds our plaque and our tomatoes and our future, and I think: This is what we keep. This is what they couldn’t take.

Epilogue — Two Years Later

On a bright June morning, Josh crossed a high-school stage to a roar that shook the rafters. I stood in the aisle with a program in my hand and Margaret’s wedding ring in my pocket like a talisman, cheering so hard my voice frayed. After the ceremony, he found me by the gym doors and wrapped me in a hug that smelled like sunshine and cut grass and whatever the future smells like when it’s wide open.

“Full ride,” he grinned, waving an envelope from the scholarship committee. “Mechanical engineering. I figured I’d keep the family tradition—only, you know, with fewer oil rigs.”

We celebrated at the house in Hilltop with pancakes for dinner and a new brass plate on the garden plaque—And the ones who stayed became our future. When dusk settled, we watered the tomatoes, checked the gate, and sat on the back steps listening to sprinklers tick across the block. Somewhere a neighbor laughed. Somewhere a dog barked. Inside, the dishwasher hummed, steady as a heartbeat.

I thought about what we lost and what we kept. The law had done its part; so had courage, and documentation, and a boy who chose the right thing when it cost him everything. But what saved us—what always saves us—was simpler: the stubborn decision to show up for each other, day after day, until safety returned like muscle memory.

Josh bumped my shoulder. “Ready, Grandpa?”

“For what?”

“For whatever’s next.”

I stood, felt the years in my knees and the light in my chest, and smiled. “Yeah,” I said. “I am.”

THE END

News

The Sniper Dropped His Rifle — And The Nurse Saw The Signal That Not Even The Marines Noticed

PART 1 Lauren Michaels had never imagined her life would lead her to a forward operating base in Helmand Province,…

Pilots Thought She Was a Mechanic — Until the F-22 Responded to Her Voice Command

Part I The sun hadn’t even topped the horizon when she arrived—barely a silhouette at first, walking with the slow,…

My Daughter-in-Law Invited Everyone to My Grandson’s Birthday—Except Me. Her Text Message Was the Final Straw

I never imagined I would become the kind of mother-in-law people whisper about—the lonely one, the one left behind. But…

My sister yanked my son by his hair across the yard, screaming, “Your brat ruined my dress!” Mom laughed and added,

The Price of a Dress I never imagined a dress could cost my son his dignity. It was a warm…

The Day My Mother Hugged My Boyfriend and Revealed the Truth That Shattered Me

My name is Lina. I’m twenty years old and in my final year of design school. My friends often say…

MY SISTER SPENT MY HOUSE FUND ON A CAR. WHEN I DEMANDED ANSWERS, MOM SIGHED:…

PART 1 I knew something was wrong the moment I walked into my kitchen and saw her— my sister, Amber,…

End of content

No more pages to load