In thirty-eight years as an educator, I learned that phone calls after midnight never bring good news.

Parents don’t call to thank you at 2:17 a.m. Kids don’t dial your number in the dark unless something has gone terribly wrong. Hospital administrators, police, panicked teachers—those were the voices I’d grown used to hearing in the small hours back when I ran the district.

But I was retired now.

I should’ve been done with those calls.

So when my cell phone shattered the silence at 2:17 a.m. on a Friday in October, buzzing angrily against the nightstand, my first thought was what it had been for the past few years whenever the phone rang late: something happened to my late son’s boy.

Jake.

I was right.

Just not in the way I imagined.

I fumbled for the phone, my fingers clumsy with sleep, and managed to hit accept on the third try.

“Hello?”

“Grandpa.”

His voice came through cracked and thin, like it had been dragged over asphalt.

I knew immediately he’d been crying.

“Grandpa, I’m at the police station,” he said. “Coach Webb—he… I attacked him. They’re saying I might go to jail. Mom’s here, but she—she doesn’t believe me.”

For a second, the room tilted. All I could see was the glowing red of the digital clock: 2:18.

“Jake, slow down,” I said, throwing the blankets back and swinging my legs over the side of the bed. “Tell me exactly what happened.”

“I tried to tell them the truth,” he said, the words tumbling over each other. “But Coach already gave his statement. He’s got bruises on his face and they think I did it. But Grandpa, I swear, he came at me first. I only pushed him away. And Mom…”

His voice dropped to a whisper.

“She keeps telling me to stop lying. She says Coach Webb would never hurt me. That I must have done something to provoke him.”

The line went quiet except for his ragged breathing.

In that moment, I heard something that took me back to my early years as a vice principal, sitting in cramped offices with kids who’d been shoved into fights they never wanted and then blamed for making adults uncomfortable.

It was the sound of a child who’d been failed by every adult around him.

“I’m on my way,” I said, already reaching for my clothes. “Don’t say another word until I get there. Do you understand?”

“They want me to sign something,” he said. “Some form.”

“Jake, look at me through this phone,” I said, trying to put every ounce of authority I’d ever had into my voice. “Do. Not. Sign. Anything. Do not answer any more questions. Tell them your grandfather is coming and you want to wait for him. Say those words.”

I heard muffled voices, the scrape of the phone against his shirt.

“Uh… Sergeant? My grandpa… he says I shouldn’t sign anything. That he’s coming. I want to wait for him.”

Another voice came on, deeper, irritated.

“Who’s your grandpa, kid?”

“Robert Hayes.”

There was a pause. Even over the phone, I could feel the air change.

Then Jake again.

“Grandpa, hurry. Please.”

“I’m already moving,” I said, jamming my feet into shoes. “Hang on, kiddo.”

The drive from my small house on Maple Street to Riverside Police Station should’ve taken twenty minutes.

I did it in fourteen.

The roads were empty, just me, the occasional eighteen-wheeler, and the halo of streetlights over intersections. Riverside at night is a different town—no marching band on Main, no crowds at the diner, no kids cutting across lawns. Just shadows and the memory of noise.

The station sat on the corner of Main and Third, a squat brick building that had been there since I was a boy. I’d walked past it a thousand times. I’d only been inside twice.

Once when my own son, Tom, got caught shoplifting at sixteen, stubborn and angry and trying to get my attention the only way he knew how.

Once when I helped organize a D.A.R.E. program back in the ’90s, still believing those three letters would change something fundamental.

I never thought I’d be walking through those doors for Tom’s boy.

The fluorescent lights in the lobby made everything look harsher—too bright, too clean. A young woman in uniform sat behind the front desk, flipping through something on her computer. She glanced up without much interest.

“Can I help you?”

“I’m here for Jake Lawson,” I said. “I’m his grandfather, Robert Hayes.”

Her fingers paused over the keyboard. Her eyes flicked up again, more focused.

“Hayes… as in the Hayes who used to run the school district?”

“That’s right,” I said. “Where’s my grandson?”

Her posture straightened as if someone had pulled a string.

“Let me get Sergeant Morrison,” she said, pushing back her chair so quickly it rolled into the wall behind her.

Morrison.

That name was familiar.

It took me a second to place it, then another to see the face it belonged to.

Dennis Morrison. Class of ’89. I’d given him detention more times than I could count when he was a hotheaded kid who thought the rules didn’t apply to him.

Now he was apparently running the station on Friday nights.

Fate has a sense of humor.

He came out three minutes later, broader than I remembered, with a shaved head and the same hard jaw and suspicious eyes he’d had at seventeen.

“Mr. Hayes,” he said. Not warm, not cold. Careful.

“Dennis,” I said. “I’m here for Jake.”

He crossed his arms over his chest.

“The kid’s in some trouble, sir,” he said. “Coach Webb came in with some serious allegations. Assault. Destruction of property. We’ve got witnesses.”

“Where is my grandson?” I asked.

“Interview room two,” he said. “But Mr. Hayes, he’s not making this easy. He won’t give us a straight story. Keeps changing details—”

“Because you’re not asking the right questions,” I said. I kept my voice level, but my hand tightened around the strap of my jacket. “I want to see him. Now.”

He studied me for a long moment. I watched him weigh his options behind his eyes: old grudges, old authority, current politics.

Then he nodded.

“This way,” he said.

Interview room two looked like every interview room I’d ever seen on TV and a few I’d seen in life: metal table, four metal chairs, single fluorescent light, cinder block walls, a mirror I’d bet my pension was two-way.

Jake sat in one of the chairs, his shoulders hunched, his right wrist wrapped in an elastic bandage that I knew damn well hadn’t been there when he left for practice that afternoon.

His lip was split. A bruise was blossoming along his cheekbone, the kind that would be purple by morning.

Melissa—my daughter, his mother—stood in the corner, arms crossed so tightly across her chest they were almost wrapped around her. Her face was set in a mask of exhaustion and something that looked dangerously like disappointment.

When she saw me, something flickered in her eyes. Relief, maybe. Or shame.

“Dad, I—” she started.

I held up a hand.

“Later,” I said.

I walked to the table and sat down across from Jake.

He wouldn’t meet my eyes at first. Just stared at his hands clenched in his lap. The knuckles were raw, skin scraped.

“Jake,” I said quietly. “Look at me.”

He did.

In his face, for a second, I saw a younger version of my son. The same strong nose, the same stubborn set to the jaw when he was trying not to cry.

“Tell me what happened from the beginning,” I said. “The truth. No matter what it is.”

He glanced at his mother, then back at his hands.

“Coach was…” He swallowed. “He was angry about the game. We lost to Cedar Ridge and he said it was my fault because I fumbled in the third quarter.”

I remembered the score from the paper. 21–17, Cedar Ridge. A tight game. One fumble could swing it.

“After everyone else left,” Jake continued, “he made me run stairs. Kept making me run even though my knee was already hurting from the first half.”

“Your knee’s been bothering you?” I asked.

“For three weeks,” he said. “I told Coach, but he said I was being soft. That if I wanted scouts to notice me, I had to play through pain.”

“Tonight?” I asked. “After the stairs?”

“Tonight…” He flexed his bandaged wrist and winced. “He grabbed my jersey and slammed me against the locker. Said I was an embarrassment. Said I was lucky he even let me play considering my dad was—”

He stopped.

“Considering what?” I pressed gently.

Jake’s voice hardened.

“He said, ‘Considering your dad was a failure who couldn’t even stick around,’” he said. “That’s when I pushed him. I just wanted him off me. But he fell and hit his face on the bench. I swear, Grandpa. I didn’t mean to—”

“That’s not what Coach Webb told us,” Dennis said from the doorway.

I turned.

He had his arms folded, leaning against the frame like he’d been there long enough to hear more than I’d have liked.

“He says Jake attacked him without provocation,” Dennis went on. “Says he tried to discipline him for violating team curfew last night and Jake went off.”

“Team curfew?” I asked, turning back to Jake. “Were you out past curfew?”

“No,” Jake said. “I was home by nine-thirty. Mom, you saw me.”

Melissa’s face crumpled slightly.

“I… I went to bed early,” she said. “I didn’t actually see you come in. But I texted you. You responded.”

She looked at Jake, then at me.

“Dad, Coach Webb has been nothing but good to us,” she said, her voice strained. “He got Jake on varsity as a sophomore. He helped with his college recruitment prospects. Why would he lie?”

Jake’s hands tightened into fists.

“Why would I?” he asked, his voice breaking. “Why would I make this up, Mom?”

The silence in the room grew thick enough to choke on.

I stood and faced Dennis.

“Sergeant, I need to see the incident report,” I said. “And I want photos of Jake’s injuries documented right now.”

“Mr. Hayes,” he began, “with all due respect—”

“Dennis,” I said, using the tone I’d used when he was a student sneaking cigarettes behind the gym. “I worked with this department for nearly four decades organizing school resource programs. I know the protocol for juvenile cases. And I know that boy is supposed to have medical evaluation before he gives any statement. Has that been done?”

His jaw tightened.

“Coach Webb didn’t think it was necessary,” he said. “Said it was just a scuffle—”

“Coach Webb isn’t a medical professional or a police officer,” I interrupted. “My grandson has visible injuries, including what looks like a sprained wrist and contusions. I want a doctor to examine him. Now.”

Dennis stared at me.

The room was so quiet I could hear the hum of the fluorescent light.

Finally, he pulled out his radio.

“I’ll call for an EMT,” he said.

“Thank you,” I replied.

As he left, I turned to Melissa.

“Sweetheart,” I said softly. “I need you to trust me on this.”

She shook her head, tears starting to spill.

“Dad, this is Coach Webb,” she whispered. “He volunteered extra hours with Jake after Tom died. He said Jake had potential. He—he’s done so much for us. For him.”

“Look at your son,” I said. “Really look at him.”

She did.

I watched the doubt creep in as her gaze took in the bandaged wrist, the split lip, the bruise on his cheek.

“Those could have happened during the game,” she said weakly.

“Did they?” I asked Jake.

He shook his head.

“The wrist happened tonight,” he said. “Coach grabbed it when I tried to pull away. The cheek was when he shoved me into the locker earlier, before I pushed him.”

She sank into a chair, the fight draining out of her.

The EMT arrived twenty minutes later, a competent woman in her forties with tired eyes and steady hands. She introduced herself, then examined Jake with professional detachment, calling out observations as an officer snapped photographs.

Bruising on the cheekbone. Swelling of the right wrist. Tenderness along the inside of the left knee.

“This knee isn’t a fresh injury,” she said, looking up. “This is at least two, maybe three weeks of repetitive stress without proper healing time. Have you been playing on this?”

Jake nodded, eyes on the floor.

“Coach said I had to,” he murmured. “We needed to make playoffs.”

The EMT looked at me.

I saw recognition in her eyes.

This was not the first kid she’d seen pushed past limits.

“Mr. Hayes,” she said, “I’m going to recommend a full medical evaluation at Riverside General. There could be ligament damage in the knee. If he’s been playing through this kind of pain…”

“He’ll get it,” I said. “Tonight, if possible.”

Dennis came back with a printed report.

I read it carefully.

According to Webb’s statement, Jake had shown up intoxicated to an extra practice session, become belligerent when confronted, and attacked him when he attempted to send the boy home. Two assistant coaches had allegedly witnessed Jake stumbling and smelling of alcohol.

“Jake,” I said. “Did you drink anything tonight?”

“Just water and Gatorade,” he said. “Grandpa, I swear.”

I looked at Dennis.

“Let’s add a blood alcohol test to that hospital visit,” I said.

“That’s not standard procedure—”

“If Coach Webb is claiming intoxication, we can verify it,” I said. “Either my grandson’s lying, and we deal with that, or he isn’t and this charge falls apart. But we’re going to know.”

He nodded slowly.

“I’ll arrange it,” he said.

The hospital smelled like antiseptic and old fear.

While Jake was examined and scanned and poked, Melissa and I sat side by side in the waiting room, saying very little.

Every so often she’d twist the strap of her purse until her knuckles went white.

“Coach really loves that program,” she said finally, staring at the floor. “Football. He… he got Jake on track after… after Tom died. Jake was so angry and lost. Football gave him something to focus on. Webb was like a father figure to him.”

I cleared my throat.

“When’s the last time you attended one of his games?” I asked.

She flinched like I’d hit her.

“Dad, you know I work double shifts at the diner on Fridays,” she said. “I can’t just—”

“I know,” I said. “I know you’re working yourself to death trying to keep the lights on. But when’s the last time you really talked to Jake? Not about homework or chores. Really talked.”

Her eyes filled.

“I’m doing the best I can,” she whispered.

“I know you are,” I said, squeezing her hand. “But the best you can doesn’t include handing over your authority as his parent to a man whose job is to win football games.”

Before she could answer, the doctor came in.

“Mr. Hayes?” he asked, his gaze flicking between us. “Ms. Lawson? Jake’s tests are back.”

He rattled off stats and phrases: grade 2 MCL sprain in the left knee, likely two to three weeks old; sprained right wrist; contusions consistent with impact against a hard surface, not a direct punch.

The blood test came back clean.

Zero alcohol.

Zero drugs.

Every piece of medical evidence lined up with Jake’s story.

Back at the house, Jake fell asleep almost before his head hit the pillow. Melissa hovered in the doorway, arms wrapped around her torso, watching him like he might disappear.

“What happens now?” she asked, voice barely audible.

“Now,” I said, “I make some calls.”

I’d spent my career in Riverside.

Teacher, then vice principal, then principal, then superintendent.

I’d shaken hands with school board members, boosters, principals, coaches. I’d attended more barbecues, fundraisers, and Chamber of Commerce luncheons than any human being has a right to.

I knew where some of the bodies were buried.

I also knew how this kind of thing tended to go.

A beloved coach versus a kid with injuries that could be explained away as “part of the game.” A community that equated success on the field with virtue. Parents who wanted scholarships more than they wanted accountability.

On Monday morning, I started making calls.

Dennis stopped taking them.

The assistant principal at Riverside High—Kelly Bryant, who I’d mentored when she was a nervous first-year teacher—suddenly couldn’t discuss “ongoing investigations.”

The superintendent’s office sent me to voicemail.

When Melissa went to pull Jake from the program, she was told that doing so would constitute breach of some “commitment” to the team and that he’d have to pay back equipment fees—eight hundred dollars she didn’t have.

The message was clear: fall in line, or we’ll make this harder than you can handle.

That evening, my phone rang.

“Bob,” a familiar voice said. “It’s Pat. Pat Wong.”

She’d been the school nurse at Riverside for twenty years before retiring last spring. Tough as nails under a calm exterior, with a way of making kids tell her what was really wrong when they came in complaining of stomachaches.

“I heard you were asking questions about Webb,” she said. “You need to be careful.”

“What do you know, Pat?” I asked.

More silence than I liked.

“More than I could prove,” she said finally. “That’s why I kept quiet.”

“Tell me anyway.”

She took a breath.

“Three years ago, I started noticing a pattern,” she said. “Kids coming to me with injuries during football season. Nothing huge at first. Sprains. Minor fractures. Concussions that weren’t being properly reported. When I tried to enforce the mandatory rest protocols, Webb went to the principal, said I was interfering with the program.”

“What happened?” I asked, though I already knew.

“The principal sided with Webb,” she said. “Football brings in money. Prestige. Riverside hasn’t had a losing season in six years. That matters to boosters. Boosters matter to the district budget. I was told, nicely, to ‘stick to bandaging and leave coaching to the coaches.’”

She laughed, but there was no humor in it.

“So I backed off,” she continued. “Officially. Unofficially, I documented what I could. Kept my own files. But I couldn’t make anything stick.”

“Do you still have those files?” I asked.

“Yes,” she said. “But Bob, if Webb finds out I talked to you—”

“He won’t hear it from me,” I said. “Can I see them?”

We met that evening at a coffee shop twenty miles outside town.

She slid a thick manila envelope across the table to me like we were in a spy movie instead of two retirees sharing a pot of burnt coffee.

Inside were records—copies of injury reports, notes from visits, her own annotations.

Concussion symptoms downplayed.

Return-to-play dates pushed up.

Kids playing back-to-back games with injuries that should’ve sidelined them for weeks.

One entry caught my eye.

Carlos M., junior running back. Lost consciousness during practice. Diagnosed with concussion. Recommended rest: 14 days minimum. Returned to full practice in 5 days. Complained of headaches, sensitivity to light. Coach says “kid is milking it.”

Beside it, in Pat’s neat handwriting: Spoke to principal. Told “we’ll monitor.” No follow-up.

“Why didn’t you take this to the state?” I asked.

“I tried,” she said. “Called the district athletic compliance office. Spoke to a woman who said she’d look into it. A week later, I was called into the superintendent’s office and told that if I kept making ‘unfounded accusations,’ I’d be terminated for cause and lose my pension.”

She stared into her coffee.

“I had eight months until retirement, Bob,” she said. “And my husband’s cancer bills piled on the counter. I couldn’t risk it.”

“This wasn’t your fault,” I said.

“Wasn’t it?” she asked. “How many kids got hurt because I chose my pension over their safety?”

I didn’t have an answer.

“Who else knows about this?” I asked.

“The principal,” she said. “Definitely. Maybe the superintendent. And there’s something else.”

She lowered her voice.

“Webb runs a summer camp,” she said. “Invitation-only. For ‘elite players.’ The kids who go come back faster, stronger. A few of them have had scholarship offers that don’t make sense. Full rides to Division I schools for kids who are good, but not that good.”

“You think he’s doing something illegal?” I asked.

“I think he’s not following any rules,” she said. “And I think someone likes it that way.”

That night, sleep didn’t even pretend to show up.

At three in the morning, I got up, made coffee I didn’t need, and sat at the kitchen table with a yellow legal pad.

I started making a list.

People I could still call.

Lawyers I trusted.

Reporters who might give a damn.

By the time the sun crept over the trees, I had a plan.

It wasn’t elegant.

It wasn’t guaranteed to work.

But it was better than sitting around hoping the system would police itself.

Tom Brennan answered on the third ring.

“Jesus, Bob,” he rasped. “You know what time it is in Arizona?”

“An hour earlier than here,” I said. “You always did skip time zones.”

He snorted.

“Smartass,” he said. “What’s going on?”

I told him.

I told him about the 2:17 a.m. call, the injuries, the conflicting statements, the district’s sudden radio silence, Pat’s file, the pattern that stretched back three years and likely beyond.

Tom had gone to law school with me before deciding he liked the courtroom better than the classroom. He’d spent thirty years in civil rights law before retiring to play golf and complain about his HOA.

Now he listened without interrupting, which is about the highest compliment a lawyer can give.

“Bob,” he said finally. “You know what you’re doing here, right? If there’s a cover-up involving the district, going after it means going after people you hired. People you promoted. People you sat next to at graduation.”

“I know,” I said.

“Your reputation’s on the line,” he said. “If you’re wrong—”

“I’m not wrong,” I said. “And Tom, if I don’t do this, who will? Jake’s terrified to go back to school. Melissa’s getting pressure from other parents to make him apologize to Webb. The system’s closing ranks, and my grandson is the one they’re going to throw under the bus.”

Tom was quiet.

“All right,” he said. “Send me everything you’ve got. I’ll look it over. And I’ve got a friend—Rachel Cordero, sharp as they come—still practicing down in Houston. This smells like something she’d take on.”

By Friday, Rachel had my file.

By Monday, she had questions.

By Wednesday, she had a plan.

“I’m filing a complaint with the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights,” she said when we spoke. “Pattern of negligence, deliberate indifference to student safety, retaliation against whistleblowers. Based on what you and Ms. Wong have collected, there’s more than enough to open an investigation.”

“How long does something like that take?” I asked, though I suspected the answer.

“Months,” she said. “Maybe longer. Federal investigations move like glaciers. Meanwhile, your grandson’s still going to school with this man as his coach.”

“And Webb’s still on the sidelines,” I said.

“For now,” she said. “Bob, listen to me. If you push too hard, too fast, you’ll tip your hand. They’ll bury evidence before we can get it. Let the process work.”

I’d spent my career telling angry parents some version of that same line.

I knew how hollow it could sound.

I wanted to believe her.

I also knew that every day Webb kept his whistle around his neck was another day some kid’s safety came second to a scoreboard.

The breaking point came two weeks later.

Jake came home on a Wednesday with a purple bruise blooming around his left eye.

He tried to slip past me on the way to his room.

“Hey,” I said. “Hold up.”

He froze.

“What happened?” I asked.

“Nothing,” he mumbled. “Just… messed around in gym.”

I stepped closer. The skin around the bruise was swollen, the kind of swelling that comes from a direct hit, not a gym accident.

“Jake,” I said. “Look at me.”

His eyes were glazed, not from injury, but from something worse: resignation.

“It doesn’t matter,” he said. “Coach says if I hadn’t tried to ruin his career, none of this would be happening.”

“None of what?” I asked. “Who hit you?”

He shook his head, lips pressed tight, and ducked into his room, closing the door.

The phone rang half an hour later.

“Mr. Hayes?” a boy’s voice said. “It’s Tyler. Tyler Jenkins.”

I knew Tyler. Wide receiver. Jake’s best friend since middle school. The kid who’d eaten dinner at our table often enough that I knew his preference for extra cheese and no onions.

“Tyler? What’s going on?”

“Webb’s been telling the team that Jake’s a snitch and a liar,” Tyler said, the words coming fast. “He said Jake’s trying to destroy the program because he’s not tough enough for ‘real coaching.’ Today, some of the guys cornered him after practice. I tried to stop them, but…”

His voice cracked.

“Webb saw it happen,” he said. “He walked away. Just turned and walked away.”

The words tasted like bile.

“Thank you for telling me,” I said. “Stay out of it as much as you can, Tyler. I don’t want you getting hurt too.”

“What are you going to do?” he asked.

“I’m going to talk to Coach Webb,” I said.

The athletic building at Riverside High smelled exactly the way it had when I retired five years earlier: sweat, laundry detergent that never quite killed the sweat, and something sharp and metallic underneath—the smell of boys trying too hard to be men before their bones were ready.

The lights were on in the football office wing.

I didn’t knock.

Webb was in his office, feet up on the desk, headset on, watching game film on a flatscreen mounted to the wall. When he saw me in the doorway, he paused the video but didn’t stand.

“Hayes,” he said. “Figured you’d show up eventually.”

“We need to talk,” I said.

He sighed and swung his legs off the desk.

“Not much to talk about,” he said. “Your grandson assaulted me. I was generous enough not to press charges. In return, you smear my name all over town. File bullshit complaints. Try to turn parents against the program.”

“You put your hands on a fifteen-year-old boy,” I said. “You made him play on an injured knee for three weeks and you’ve encouraged players to retaliate against him since he told the truth.”

He stood.

It was then I saw him the way the boys must have seen him: big, broad-shouldered, a jaw like a cinder block. A man who had never been told “no” in a way that stuck.

“I built this program from nothing,” he said, coming around the desk. “We’ve got district titles. We’ve got kids going to college who never would’ve had a shot. You think anyone’s going to believe your conspiracy theories over that record?”

“I think patterns have a way of revealing themselves,” I said. “So does federal oversight. There’s an investigation coming. Not just into what you did to Jake, but into the way you’ve run this team. The concussions. The painkillers. The retaliation.”

Something flickered in his eyes.

“What investigation?” he asked.

“The one the Office for Civil Rights is opening,” I said. “The one based on three years of documentation from the school nurse, sworn statements from former players, and medical records that say you risked kids’ lives to win football games.”

“You smug son of a—” he began.

He moved toward me, his arm cocked back.

I was sixty-two.

He was in his forties, built like the linebacker he’d once been.

I saw the punch coming too late to avoid it completely, but old instincts—ones I hadn’t used since breaking up fights in hallways—kicked in.

I stepped to the side.

His fist grazed my shoulder instead of my jaw.

Pain shot down my arm, white and hot.

He stumbled, catching himself on the filing cabinet, papers sliding to the floor.

“Webb!” someone shouted from the doorway.

We both turned.

Tyler stood there, eyes wide, phone in his hand, camera pointed at us.

“I called the cops,” he said, voice shaking but steady. “I got it on video. You swung first. Twice.”

Webb’s face went from red to pale.

“This isn’t what it looks like,” he said quickly, raising his hands. “He came at me. I was just defending—”

“Don’t say another word,” I said. “You’ll want a lawyer present for the rest.”

The police arrived eight minutes later.

Different officers this time. Not Dennis.

They took statements, watched Tyler’s video, and separated us.

One of them, Sergeant Perkins—who’d been a fresh-faced patrolman when I was still at the district—pulled me aside.

“Mr. Hayes,” he said. “You want to press charges?”

I looked through the office window at Webb, sitting slumped in a chair, a towel of ice pressed to his knuckles.

He looked smaller somehow.

Not physically.

But the aura of untouchable authority he’d worn like a second skin had cracks in it.

“Yes,” I said. “I do.”

Webb was arrested that night for assault.

The District Attorney’s office declined to charge me with anything, ruling that I’d been acting in self-defense.

Tyler’s video made sure there was no room for Webb’s version of the story to breathe.

When the federal complaint Rachel had filed landed on the superintendent’s desk three days later, it did so in a different world than the one in which we’d first started.

More parents came forward.

More kids found their courage.

What had been whispers became statements.

What had been rumors became evidence.

The investigation took six months.

Six months of tension in grocery store aisles, sideways looks at the post office, “snitch” spray-painted on my driveway one night by a kid who I later saw at the library looking too ashamed to meet my eyes.

Six months of Jake adjusting to a new school in the next district over, new teammates, a new sport—baseball instead of football. Less glory. Less pressure. Fewer concussions.

Six months of Melissa going to therapy for the first time in her life, unpacking her grief over Tom, her guilt over not believing her son when he needed her.

Six months of me, an old man, learning that retirement didn’t mean my obligation to kids in this town had ended when I turned in my keys.

When the results came back, they were worse than even I had imagined.

Webb had been distributing banned supplements to players at his “elite” summer camp. He’d falsified injury reports and intimidated students and families who questioned his methods. The principal and athletic director had known. The superintendent had dismissed three separate internal complaints as “personality conflicts.”

They all lost their jobs.

Riverside High’s football program was suspended for two years.

The district quietly settled with seven families. One of those kids, Carlos Martinez, sent me a graduation photo with a note that said, “Thank you for giving me my life back.”

Webb was convicted on charges of assault and reckless endangerment. The charges related to distributing controlled substances took longer, but he eventually pleaded to a lesser offense as part of a deal that ensured he’d never coach again.

The town was split.

Some people stopped talking to me.

Some started talking to me more.

At the grocery store, a man I didn’t recognize but who clearly recognized me muttered, “You ruined Riverside football,” as he walked past.

At the park, a woman I’d sat next to at countless school programs squeezed my arm and said, “You saved my nephew and you don’t even know it.”

They were both probably right in their own ways.

One Saturday morning, about eight months after that first 2:17 a.m. phone call, Jake came by my place unannounced.

I was in the garage, sanding the top of an old workbench I’d been meaning to restore for years.

“Grandpa?”

I looked up.

He’d grown.

He always looked older to me in bursts, as if my mind had to catch up between visits.

“What’s up, kiddo?” I asked.

He leaned against the door frame.

“Can I show you something?” he asked, holding up his phone.

“It better not be another TikTok of someone falling off a roof,” I said. “My heart can’t handle it.”

He rolled his eyes and tapped the screen.

“It’s from the school board meeting last night,” he said. “I thought you’d want to see.”

On the screen, the district auditorium came into view. The dais. The board members. A microphone on a stand in the center aisle.

Pat walked up to it.

Her hair was more silver than gray now, and she leaned a little on the cane she’d started using after a fall last winter. But her voice, when she spoke, was as clear as it had been the day she’d chewed out a principal for trying to send a sick kid back to class.

“I’m here,” she said, “to talk about a new policy you’re voting on tonight.”

She looked up at the board members, some of whom shifted in their seats.

“It’s called the Hayes Protocol,” she said. “It requires independent medical evaluation for all sports injuries, mandatory rest periods for concussions and ligament damage, and whistleblower protections for any staff who report violations.”

She glanced toward the back of the room as if she knew I’d be watching, even though I hadn’t gone.

“It will not fix everything,” she said. “No policy can. But it’s a start. And it exists because one grandfather refused to accept that ‘that’s just how it is’ when a coach hurt his grandson.”

She smiled then, a little sad, a little proud.

“Because Robert Hayes decided one child’s safety mattered more than protecting a broken system,” she said. “Others followed. And now we’re here. Let’s make sure no nurse, no teacher, no kid has to go through what they did in order to be heard.”

Jake paused the video.

“Pretty cool, Grandpa,” he said. “Having a rule named after you.”

I set the sander down and leaned on the workbench, my eyes suddenly a little blurry.

“Yeah,” I said. “Pretty cool.”

We worked on the bench together for a while after that, in companionable silence. Sanding, wiping, measuring. Simple tasks with satisfying results.

I thought of my son, Tom—angry teenager-turned-good man taken too soon by a highway and a drunk driver—and wondered what he’d say if he could see us.

I hoped it would be something like, “Good job, Dad.”

That night, just as I was about to turn out the light, my phone buzzed again on the nightstand.

I checked the display.

Unknown number.

Different area code.

For a moment, the old dread rose up.

I answered anyway.

“Hello?”

“Mr. Hayes?” a woman’s voice asked, tight with something I recognized too well: fear and shame and a lack of sleep.

“Yes,” I said. “This is Robert Hayes.”

“My name is Jennifer Dalton,” she said. “I got your number from Mrs. Wong. My son… he’s on the basketball team at Lincoln. The coach… something’s not right. He won’t tell me what’s happening, but I can see he’s scared. I don’t know what to do.”

I sat up and reached for the notepad I kept on my nightstand now.

“Okay, Jennifer,” I said. “Take a breath. Tell me everything. Start from the beginning.”

Because I had learned something in those months I spent fighting for Jake, something that went beyond policies and protocols and federal complaints.

Sometimes, the system doesn’t protect kids the way it’s supposed to.

Sometimes, it shields the people who hurt them and punishes the ones who speak up.

Sometimes, what it needs isn’t another memo.

It needs one person—old, tired, retired—who refuses to look away.

It isn’t always easy.

It isn’t always appreciated.

But it is always necessary.

And I wasn’t done.

Not by a long shot.

THE END

News

“Where’s the Mercedes we gave you?” my father asked. Before I could answer, my husband smiled and said, “Oh—my mom drives that now.” My father froze… and what he did next made me prouder than I’ve ever been.

If you’d told me a year ago that a conversation about a car in my parents’ driveway would rearrange…

I was nursing the twins when my husband said coldly, “Pack up—we’re moving to my mother’s. My brother gets your apartment. You’ll sleep in the storage room.” My hands shook with rage. Then the doorbell rang… and my husband went pale when he saw my two CEO brothers.

I was nursing the twins on the couch when my husband decided to break my life. The TV was…

I showed up to Christmas dinner on a cast, still limping from when my daughter-in-law had shoved me days earlier. My son just laughed and said, “She taught you a lesson—you had it coming.” Then the doorbell rang. I smiled, opened it, and said, “Come in, officer.”

My name is Sophia Reynolds, I’m sixty-eight, and last Christmas I walked into my own house with my foot in…

My family insisted I was “overreacting” to what they called a harmless joke. But as I lay completely still in the hospital bed, wrapped head-to-toe in gauze like a mummy, they hovered beside me with smug little grins. None of them realized the doctor had just guided them straight into a flawless trap…

If you’d asked me at sixteen what I thought “rock bottom” looked like, I would’ve said something melodramatic—like failing…

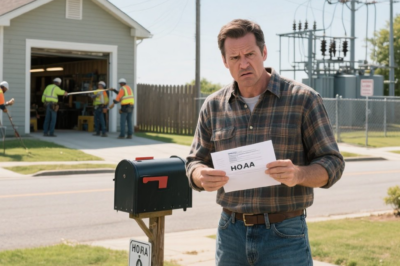

HOA Cut My Power Lines to ‘Enforce Rules’ — But I Own the Substation They Depend On

I remember the letter like it was yesterday. It came folded in thirds, tucked into a glossy HOA envelope that…

I Overheard My Family Planning To Embarrass Me At Christmas. That Night, My Mom Called, Upset: “Where Are You?” I Answered Calmly, “Did You Enjoy My Little Gift?”

I Overheard My Family Plan to Humiliate Me at Christmas—So I Sent Them a ‘Gift’ They’ll Never Forget I never…

End of content

No more pages to load