Part I

On the morning I was supposed to become Mrs. Ethan Lou, my sister Willow sent me a text with two emojis—🤫💋—and a grainy photo of highway taillights disappearing into fog.

I didn’t understand what I was looking at until the wedding planner knocked on the bridal suite door, eyes glassy, whispering the words like they might shatter if she said them too loud: “Ethan… left. He’s with— I’m so sorry, Grace.”

Every small thing my mother had drilled into me about being gracious under pressure fled. I stood there in my slip and veil, a paper flower in a hurricane, staring at the rack of chiffon that suddenly looked like costumes for a play that had been canceled.

My father tried to bluster useful. My mother tried to turn back time. My friends tried to get me to breathe with them. I ended up in the church kitchen, sitting on a crate of seltzers, eating a cupcake with bare hands while strangers’ voices buzzed through the walls: “Can you believe—” “The sister?” “Like a soap opera.”

The strange mercy was that no one asked what I wanted. I didn’t know. If I had known then what I know now—that the next twenty-four hours would end with me signing a different paper, a different name—I don’t think I would have done anything differently. Not because I planned it. Because life did.

He arrived just after noon, when the flowers were already wilting and my mascara had made its little black roads down my cheeks. He walked through the kitchen with the kind of authority only certain men inherit—a presence that made space without asking. Taller than Ethan by a head, shoulders broad under a charcoal suit, tie still tightened like a man who doesn’t break dress codes even on bad days.

“Grace,” he said.

I had met him twice before—once at a family dinner where he ate in silence and then paid for everyone without letting anyone thank him, and once at the engagement party where he stood in a corner and watched Willow sing “At Last” like a girl trying on a life too big. I knew his name was Marcus. I knew he ran the family company that Ethan liked to talk about controlling someday. I knew the rumors: ruthless, cold, the kind of man who put out fires by burning the building down.

“Your father is trying to move the guests to the cocktail hour,” he said. He wasn’t a man for preambles. “Your mother is attempting to kill your sister by telepathy. My brother is—” He didn’t finish. He didn’t need to.

“Are you here to drag him back?” I asked. The words came out flat.

“I’m here to make sure you don’t end up alone in a room full of people who want to feed off your pain,” he said. “And to offer you an option.”

I laughed then—a harsh, surprised sound that tasted like salt. “An option?”

“We can fix the optics,” he said. “Not for them—for you. You don’t deserve to become a punchline. We can end the day with the family still owing you respect.”

“By…?”

“Marrying me,” he said, like it was a translation. “Right now.”

The air left my lungs. “You can’t be serious.”

“I’m not interested in humiliation,” he said, and something in his voice shifted—less CEO, more boy who had once learned to survive by making fast calculations. “Not yours. Not mine. My brother is impulsive. He always has been. He is also my responsibility in a way he has never been yours. If you marry me, you stay where you earned your place—inside the room, not outside it. The rest I will handle.”

I stared at him like he’d offered me a parachute I didn’t know I wanted until the plane door opened. “What do you get out of it?”

“Clarity,” he said. “An end to speculation. And the answer I prefer to the question people are already asking about this family.”

“What’s the question?”

“Who’s in charge.”

My mother would have called this a deal with the devil. My father would have called it smart. I didn’t call it anything. I thought about the aisle I would not walk, the dress I would not wear, the vows I would not say to a man who had decided he preferred the drama of rescue to the patience of love. I thought about the way Willow had smiled when she tried on my shoes “just to see,” and the way Ethan had laughed when he told me, weeks before, that Marcus was “a machine, not a man,” and how he said it like it was an insult when I could hear the envy underneath.

“Okay,” I said, surprising both of us. “Okay.”

He didn’t smile. He nodded, crisp, like the conclusion of a meeting that had gone as expected. “We’ll do it at the courthouse,” he said. “Less theater. Fewer witnesses.”

We left through the service door because fairy tales and exits are always complicated. He drove; I stared straight ahead so I wouldn’t see the church in the rearview. At City Hall, the clerk squinted at us like she wanted to ask for a backstory and then decided her pension meant more than her curiosity. He filled the form efficiently, his handwriting the careful kind of a man who knows signatures become footprints.

“Are you sure?” the clerk asked me, the only stranger that day who bothered to offer me an out.

“No,” I said honestly. “But I’m here.”

The ring was a thin band the clerk pulled from a drawer, the sort of thing they keep for people who forgot jewelry but remembered determination. He slid it onto my finger with steady hands. I said “I do” with a voice that sounded like it came through a wall. A stamp landed on paper. A stranger said “Congratulations.” There were no violins. No doves. Just fluorescent light and the feeling that a page had turned audibly.

Back at the hotel, the cocktail hour had become a murmuring hive. People lifted their heads when we walked through, the way animals do when they sense weather changing. My mother’s face did a thing I didn’t know faces could do—rage, relief, and calculation all struggling for real estate.

“Thank you, Marcus,” she said, as if she had planned it. “We always knew you were the reliable one.”

“My pleasure, Mrs. Chen,” he said, voice polite as a blade.

Ethan wasn’t in the room. Willow wasn’t either. For an hour, we played our roles—he, the unflappable elder son; me, the woman who had found a different way to survive the day. He held my elbow when we moved; I remembered to sip water between words. When someone offered pity like a canapé, I let it slide to the floor.

We did not see them until the airport the next morning.

I was at the VIP lounge bar, trying to learn how to drink coffee again, the ring still unfamiliar on my hand, when Ethan appeared in the mirror behind the bottles, eyes bloodshot, hair messier than I had ever seen it small-hours messy. Willow hovered at his shoulder in a hoodie too expensive to be casual, her mouth a thin red line.

“Grace,” he said, and my name didn’t sound like mine anymore. “We need to talk.”

I turned. “Do we?”

He opened and closed his mouth. “Yesterday was— it was a mistake. I panicked. Willow— it’s complicated. We were going to come back. I was going to—”

“Be the hero,” I said. “Kick in your brother’s door and demand he forgive you, and then marry me after the town stopped laughing.”

His face twitched—the recognition of being read accurately. “You don’t know what I—”

“I know you didn’t call,” I said. “I know you let me find out from a wedding planner who didn’t earn that job. I know my sister took my shoes and my groom and sent me a photo of a highway like a brag. I know you chose a story over a person.”

He swallowed. “Grace, please—”

A shadow fell over us. Marcus had arrived without me sensing him; he had a talent for appearing like consequence. He didn’t look at me. He looked at Willow like she was a problem a junior associate should have solved.

“You are Willow,” he said, voice flat as a ledger.

She flinched. “Yes.”

He nodded once, as if confirming inventory. Then he reached into his inner pocket, took out a red booklet, and dropped it on the table. The marriage certificate looked obscene in the lounge light—too intimate in public. He set another on top of the first. They glared up at Ethan like wounds.

“Marcus,” Ethan said, a warning and a plea layered together. “You can’t—”

“I can,” Marcus said. “I did.”

Willow’s face went the color of oversteeped tea. “This is a mistake,” she said, but she was looking at me, not at him.

“It’s a decision,” I said. “You made yours yesterday.”

Ethan stared at the red booklets like he could set them on fire by glare. “Grace, you don’t know him. He’s—”

“Efficient?” I said. “Heartless? Practical? Yes. And none of those things left me at an altar.”

Marcus’s arm settled around the back of my chair. He didn’t touch me. He didn’t need to. The message was as readable as a billboard: mine.

Willow’s face crumpled into a performance of fragility. “We never meant to hurt you,” she whispered. “I thought light would save me. It pushed me into darkness.”

“She posts like that,” I murmured, too tired to be polite.

Ethan’s jaw flexed. “Grace, don’t be cruel.”

“My cruelty looks like paperwork,” I said. “Yours looked like running.”

He didn’t have an answer for that. He never had been good at answers that didn’t come with applause.

We left them there, flanked by luggage and bad choices, and walked into the heat. Marcus didn’t speak until we were inside the car. The Bentley swallowed city noise the way money always does.

“Feel better?” he asked.

“Good enough,” I said.

“That will do,” he said, and looked back at his phone like the matter had been moved to a different file.

Marcus’s home was not a house. It was a statement. Glass and steel, long planes of marble, a view that made the city look like a model on a table smoothed by someone’s palm. A butler in a suit so perfect it made me sit up straighter took our coats and offered a dinner prepared “for two.” The only color in the room came from a bowl of lemons so carefully arranged I wanted to rearrange them quietly out of spite.

“Miss,” the butler said with a small nod I couldn’t interpret. “A room has been prepared for you.”

Prepared. Like a hotel. Like a stage.

Marcus ate in silence. It wasn’t the silence of punishment; it was the silence of a man who considered eating a task, not a pleasure. The food was exquisite; I tasted none of it. When I stood, he said, “Family dinner tomorrow. My grandfather insists. Do not embarrass me.”

“By existing?” I asked.

“By giving them what they want,” he said. “A spectacle.”

“What do you want?”

He looked at me like I’d asked him what weather he preferred. “Results.”

In the room they had prepared for me, there was a faint scent of sandalwood and a small incense burner on the nightstand. The sheets were so crisp they whispered when I lay down. My phone vibrated on the table—Ethan’s name, then a number I didn’t know, then a message that read Answer. Please. I blocked both. The screen went dark. The quiet grew large enough to feel like company.

Minutes later, my social feed lit. Willow had posted a photo of black ocean. Some light, thought to be salvation, pushed me into deeper darkness. Comments arrived in a cascade of empathy from people who always sided with the most fragile voice in the room. Sweetie, call me. Who did this to you? We’ve got you, babe.

I almost threw the phone. I didn’t. I set it facedown. A chime pinged. Marcus had posted for the first time in the history of his pristine profile: a photograph of a red booklet held by a hand with knuckles that looked like they could make decisions. Caption: Mine.

Crafty, I thought, with a smile I did not approve of even as it landed.

A knock at the door. Marcus stood there in a black silk robe tied like a concession to sleep he had granted himself unwillingly. He held out his phone. “Tell her to delete it,” he said.

“I have no leverage,” I said.

“I do,” he said. “And I used it.”

He had. The post was gone. His eyes were the kind of dark that isn’t a color but a temperature. “Do not entangle yourself with people beneath contempt,” he said, as if reciting a clause in the contract we had not signed but both understood.

“Understood,” I said.

He paused, like he was about to add a sentence and decided against it. “Eight o’clock. Don’t be late.”

He left. I leaned against the door and realized my palms were cold. Deals with devils aren’t just about the price. They’re about what you become to afford it.

The Lou family estate wasn’t a house either. It was a museum that had learned to eat. A long mahogany table, portraits that seemed to track you with stern disapproval, a patriarch at the head whose cane thunked against the floor when the conversation displeased him. Ethan sat on one side, the bruise on his mouth faint under makeup, Willow beside him, pale and pointed inward, a doll who had been dropped.

Marcus put ribs on my plate. “The chef knows what he’s doing,” he said. “Eat.”

“Yes, dear,” I said, because if I was going to be theater I could learn my lines.

Ethan’s chopsticks creaked in his hands. Willow’s gaze fluttered like a moth trying to find a dark corner. The soup came—a fragrant broth in delicate porcelain. Willow stood with a tremble anyone with eyes could read as rehearsal.

“For you, Grace,” she breathed, and took a single step that looked like a dance.

She fell. The soup did not. It lifted and flew in a bright arc toward my face.

I didn’t see Marcus move. I felt him, though—his arm a bar, his body between me and heat. The soup struck his back and he grunted like a man refusing to make sound out of pain. The room went still. The butler appeared with a first aid kit like he had been waiting out of frame. Ethan knelt beside Willow and forgot the man who had just shielded me with skin.

“Willow, are you burned? Tell me where it hurts,” he asked in a panic edged with theater.

“You think she did this?” Marcus asked him, voice flat as a lake in winter.

“Who else?” Ethan snapped, not looking up. “She hates Willow.”

Marcus set his phone on the table and tapped play. The feed from a discreet camera blinked onto the screen—Willow’s face, a pause too long to be anything but choice, the twist of ankle too neat to be chance, the tilt of the bowl a perfect arc.

“I liked the new fixtures,” Marcus said. “I record what I like.”

Grandfather’s cane struck the tile, the sound like a gavel. “Disgrace,” he said. “Shameful.”

Willow folded in on herself. Ethan’s face did a different kind of falling, the kind that leaves a man older in seconds. He looked at me then, and the look wasn’t anger anymore. It was something worse. It was realization.

I didn’t say anything. I didn’t have to. Marcus’s back reddened under the ruined shirt like a warning flare. I stood and held the ice pack to him in the car on the way home, and when he hissed I said, “Tell me if it’s too much,” in a voice I hadn’t used since before the church kitchen cupcake.

“Why didn’t you defend yourself?” he asked, watching me in the rearview.

“Would anyone have believed me?” I said.

He didn’t answer. He closed his eyes like that question had a way of fitting under his ribs and pressing.

We reached the house. He stepped out and said, “Move into the master bedroom.”

I blinked. “Why?”

“I dislike trouble,” he said. “This arrangement creates less of it.”

His reasons always came dressed in discipline. I nodded. We walked inside the fortress we were learning to call a home.

That night, I slept hard in a room too big for one person and woke to the sound of someone sobbing outside the gate. Ethan. He had found a new number. He had found his way to the one place we still had in common—the street we used to share in a different story.

“Five minutes,” he begged through the intercom. “Please.”

“Three,” I said, pulling a coat over pajamas, stepping into cold that felt like an honest thing.

He stood against the car like a man auditioning for grief, cigarette butts at his feet, eyes red in a way that did not flatter. “Grace,” he said. “Leave him. I was wrong. I— I’ll fix it. I’ll fix everything.”

“I don’t need to be fixed,” I said. “I need to be respected.”

He took a step, the anger reemerging like a bad habit. “What did you do to him? How did you—”

A shadow moved at the edge of the property. Marcus. He didn’t speak. He didn’t need to. He walked down the steps, crossed the yard like a weather system, and hit his brother once, clean and humiliating.

“My property,” he said quietly. “My person. You will not touch either.”

The butler and two men I hadn’t seen before lifted Ethan by his elbows and took him away. The world went quiet again.

Marcus looked at my wrist, red where Ethan had grabbed it through the bars, and went inside to get the first aid kit like anger made him efficient. He dabbed the ointment on with a tenderness that didn’t match the bruise he had put on his brother’s face. He looked up from that small work and asked a question I didn’t expect.

“What he said,” he said. “Is it true?”

“What?”

“That you were something he didn’t want.”

I met his eyes. For a second, the room narrowed to that line between us. “In your eyes,” I asked, “am I?”

He paused. Not for effect. To choose an answer. “No,” he said finally, with a weight that made it sound like something he hadn’t planned to hand to anyone. “You are the only thing I would reclaim at any cost.”

It was absurd. It was terrifying. It was the first honest thing either of us had said all day that wasn’t barbed.

The next morning, the company announced a “strategic reassignment.” Ethan—formerly the heir apparent, the second son with a taste for attention—was “promoted” to a vice presidency in a region far from where anyone would notice if he fell. The congratulations came with a laugh behind the hand. The gossip fed and starved itself in a loop. People looked at me like I had found a new shortcut through the city, and I looked back at them like they hadn’t earned a map.

By afternoon, Ethan’s mother called. She had always liked me, in the way women like daughters they think will be manageable.

“Grace,” she said at the tea room, stirring a cup she wasn’t drinking. “I hear my son has been… reassigned. You might talk to your husband.”

“My husband,” I repeated. The word sat strange and then settled.

She slid an envelope across the table. “This will help,” she said. “Ten million. Ask Marcus to be merciful. For Ethan’s sake. For yours.”

I pushed the envelope back. “Ethan and I are over,” I said. “And this isn’t a math problem.”

Her expression shifted—soft hardness, the kind people call concern when it’s really control. “Marcus,” she said, “is not a good man.”

“He is my husband,” I said. “I’ll find out for myself.”

She drew back like I had insulted her living room. “You’ll regret this,” she said.

“I used up regret at the church,” I said, and stood.

When trouble returned, it wasn’t wearing pearls. It staggered through the garden with whiskey breath and shouting my name. Marcus handled it the way a storm handles a weak fence: one strike, then quiet.

And after—the ointment, the question, the answer—I sat on a too-large bed and stared at the ceiling and thought, for the first time since the paper we didn’t sign: Maybe, just maybe, the thing I had done out of rage and humiliation and strange, cold logic could make room for something else. Something that looked like safety. Something that looked, if you squinted, like a different kind of love.

Part II

The quiet that followed Ethan’s removal from our gate didn’t feel like peace; it felt like a held breath. I filled the days with motion so the nights wouldn’t catch me—lists, laundry, a flower-arranging class where widows with strong opinions corrected my stems, a baking workshop where my butter never softened as quickly as anyone else’s. Marcus left early and returned late. We practiced a choreography of avoidance, intersecting only at the threshold of the evening and morning.

The house wasn’t warm, but it had rules, and rules are a kind of kindness you can measure. A light left on in the living room. A glass of milk covered with a saucer at midnight that I pretended not to notice and he pretended not to have placed. The butler, whose name I finally learned was Mr. Zhou, developed a habit of coughing in rooms where he found the two of us lingering too long in silence, as if he could ventilate the air by force.

Then the rain came. Sterling City rain has a way of making you forget summer ever made promises. I ran from the curb to the door and didn’t run fast enough. By evening, my sinuses were a fist and my forehead a kettle. I lay on top of the sheets in the second-largest bed I had ever seen and drifted down into a fever that sounded like airport announcements in a language I almost understood.

A cool cloth touched my face. I surfaced, surprised. The room was dim. Marcus sat on the edge of the mattress like a man who had been deputized by circumstances he did not respect. He touched my forehead, then his own, frowning. “Still hot,” he murmured, as if the temperature had personally offended him.

“Don’t go,” I said. I don’t know whether I meant don’t go get the medicine or don’t go back to your study or don’t go back to the way we were before this moment.

His hand stilled. Something in his shoulders surrendered very slightly—less a slump, more a recalibration. He didn’t go. He sat and held my hand while the fever argued with me. His palm was cool and dry, and I fell asleep trying to count the bones of it the way children count sheep.

When I woke, morning and ordinary had returned. He was gone. On the nightstand: two tablets and a glass of water with condensation soldered to the coaster. The world had not changed. Except that it had.

Downstairs, he sat at the dining table with a folder of contracts and shadows under his eyes. “Feeling better?” he asked without looking up.

“Mm,” I said, embarrassed by the intimacy of gratitude.

“That’s good,” he said, and turned a page like he was closing the subject.

Halfway through breakfast he said, as if it were as routine as the weather, “Next weekend there’s a charity gala. You’ll come with me.”

“I figured,” I said. It felt like performing community service for a crime I had not committed. I did not say that out loud. My grandmother taught me to flatter fate where it could hear.

He had a dress sent—midnight blue, beadwork that caught the light like a story you tell yourself, cut low enough to make me self-conscious and then, when I stood in front of the mirror and squared my shoulders, not self-conscious at all. The ring the courthouse clerk had slid on my finger looked like it suddenly understood it had a context.

The gala was held in the sort of ballroom that makes cameras forgive people, with white flowers that smelled like wealth translated into scent. Marcus worked the room the way generals work maps. People came to him with faces they had rehearsed. He gave them nods calibrated to send them away satisfied. I stood on his arm and pretended my feet did not belong to me.

At the bar, a man with a drink and a smile too slippery leaned toward me. “Mrs. Lou,” he said, glancing at my ring. “You’re even more beautiful than your reputation.”

“Reputations don’t have cheekbones,” I said, and was proud of the way it sounded until he laughed like I’d given him something.

Marcus was suddenly there, his hand at the small of my back in a way that shifted my center of gravity. He wasn’t smiling. The man retreated with a murmur. “You don’t have to save me,” I said to Marcus, pleased at the steadiness of my voice.

“I don’t,” he agreed, and did not remove his hand.

Across the room, I saw Willow. The sight of her felt like a finger pressed to a bruise I thought had gone. She had lost so much weight that her collarbones looked like parentheses. She was with a man who couldn’t decide whether to touch her elbow or count the room. He had a steak of oil on his tie that said his appetite was not limited to food. Willow saw me seeing her and the expression that crossed her face was not the old triumphant brightness; it was a knife: jealousy, hatred, humiliation, hunger.

I leveled an elegant smile at a woman beside me who had raised her glass in friendly appraisal and turned away from the place where old wounds had set up shop.

At some point the air inside the room thinned. Marcus led me out onto the terrace. The city spread below us like an argument that had been resolved temporarily. “Tired?” he asked.

“A little,” I admitted, rolling my ankles in my shoes.

Before I could protest, he knelt. “What are you— Marcus.” The word came out in a whisper that sounded like someone else’s. He took my foot in his hand like it was a problem he could solve, slid the heel free, and his thumb pressed at the joint in a way that made an entire muscle group forgive me at once.

“Don’t move,” he said. A couple moving past on their way out gasped quietly the way people do when a story they thought they knew suddenly changes narrators. My cheeks burned.

“People are staring,” I said.

“They always stare,” he said, and lifted my other foot. His hands were blunt but careful. He had the face of a man refining a tool.

By the time my feet belonged to me again, I had trouble remembering what my name was. He reached into his jacket pocket and slid something onto my left ring finger.

It was not a diamond the size of a grudge. It was a slim band, plain and lovely, with one small engraved letter inside. G.

“What is this?” I asked. My voice betrayed me by trembling.

“Ten years ago,” he said, still kneeling, the terrace light setting his face in a relief I’d never seen. He looked up and it felt like a lens had turned. “Ten years ago I got thrown out of my father’s house. I hadn’t learned yet how to be useful enough to keep. I slept rough for a week under the eaves of a building near the art college and told myself stories about what kind of man didn’t take care of his son. On the last day of that week, I was hungry enough to barter my last pride for a piece of bread. Before I did, a girl in a white dress handed me a roll and two hundred dollars and said, ‘Tomorrow will be a different day.’”

I saw it as he said it—the bread, the boy, the way afternoons get darker faster when you haven’t eaten. There are kindnesses so small you forget them as soon as you give them, because giving them feels like breathing. My memory tilted. A missing puzzle piece slid into place with a click I felt in my ribs.

“It was you,” I whispered. “I— I gave you—”

He nodded. “I looked for you,” he said. “I learned how to be useful and then I learned how to be feared and then I learned how to be in charge. I kept a picture of your dress in my head like a talisman against the parts of the world that break first. Three years ago, my little brother brought home a fiancée. She laughed in a way that made other people look at the source. She had two dimples when she smiled. She cut the crusts off his sandwiches because he said he liked them better that way. I recognized her at the door and did not introduce myself.”

“You didn’t— why?”

“Because if I said it out loud,” he said, getting to his feet, “I would have scared you with the size of it. And because,” he added, very quietly, “I wanted to see if I was remembering the right person. I watched you be kind to a man who hadn’t earned it. I thought I had learned patience. I had not.”

My throat closed. The idea that men like him tracked old mercies the way the rest of us track debts did something to me I was neither ready for nor eager to undo.

“The rumors—” I began, fumbling for the pieces of a different story. “You and Willow—”

He smiled then, a cruel, brief thing that terrified me and thrilled me and made me want to step closer and step away. “I understood my brother,” he said. “He prefers the damsel to the wife. A woman in distress makes him feel taller. I gave him what he loved to carry. If you want to kill a rotten beam, you don’t pull it out and hope the roof holds. You put weight on it and let it crack in daylight.”

“You— you planned—” I swallowed, shocked by the part of me that understood and the part that recoiled. “You gambled with me.”

“I gambled on you,” he said. “Not on your pain—on your pride. I knew you would not stay where you were not wanted. And I told myself if I was wrong I would learn to live with watching you choose someone who didn’t deserve you.” He reached out and touched my cheek, the barest brush of his knuckles, as if he was afraid the pressure could bruise. “I did not calculate that I would go mad watching you set places at a table I knew would be kicked over.”

The city hummed. The party behind us proceeded. I stood in a dress he had chosen, with a ring he had carried in his pocket like a solution he refused to force, and I felt a story that had been written in me without my consent shift its tense.

“I am not a project,” I said, because I needed to hear the refusal out loud.

“I know,” he said. “You are an answer.”

It was absurd. It was beautiful. It was the worst idea I had ever heard. It was the only thing that had made complete sense to me in months. My throat hurt. My eyes did something I had tried not to let them do since the church kitchen. I let them. When he stepped into me, when his forehead touched mine the way people huddle in storms, I did not step back.

On the drive home, the city’s triangles of light blurred. He told me the rest—his mother’s quick death, his father’s graceless remarriage, the years of being family on Tuesdays and employee on Thursdays, the night under the eaves and the roll and the money and the way my voice had rewritten the next day in his head. He spoke like a man opening drawers in a room no one else had been allowed to enter. I listened like a woman being offered a key.

He kissed me in the foyer the way men kiss when they have finally arrived at the address they have been driving past on purpose. I kissed him back with the relief of someone who had spent months speaking through glass and suddenly found a door unlocked.

“Grace,” he said against my mouth, as if my name had weight.

“Yes,” I said, and felt the floor find me.

We were no longer a contract keeping two egos from embarrassment. We were a problem and a solution in the same room, and if that terrified me, it also steadied me. We did not become simple. We became honest.

In the weeks that followed, I learned the shape of his tenderness and the stubbornness of his habits. He brought me an herbal tea one morning, grimacing like he’d lost an argument with a search engine, when cramps turned me into a woman who wanted to set small fires. I drank it and pretended I didn’t notice the way he watched my face. He framed a napkin doodle I made absent-mindedly during a call—three lines and a crooked house—and hung it in his study like a gallery had demanded it. He waited up when I stayed up too late working, failing at pretending he had drifted off on the couch. I woke in our bed, blankets tucked around me with the efficiency of a man who knows how to secure a shipment.

I learned how he carried exhaustion—silently, as if it were an inheritance he refused to sue. I learned the tone his voice took when he was angrier at himself than at anyone else. I learned that his laughter did exist, low and sudden like a secret handshake with joy.

News of Willow arrived in our social circles as if through a bad radio—staticky and too loud. She’d been seen at a karaoke bar with an investor whose hands did not listen. She’d drunk from a bottle that should not be put to a mouth. Her friend filmed her for laughs and then forgot to stop. I did not feel victorious. I felt tired in a deep place where empathy goes when it has been dampened for too long.

Ethan did not go bankrupt. Marcus said he never planned to let him. “Going broke would make him interesting,” he said. “I prefer him boring.” He assigned him to a region where ambition goes to dry out. When the Northwest venture showed promise, Marcus let him taste the high and then pulled the rug. “He needs to learn that work is not a performance,” he said. “He needs to learn it with his own hands.”

One night, we found ourselves at the window together, curtains open, city a living thing outside. Marcus said, out of nowhere, “I am afraid of two things.”

I turned. “Spiders?”

“Not what I had in mind,” he said. “Losing you. And becoming the man my father trained me to be when I am tired.”

“You won me,” I said. “And you are allowed to be tired.”

He looked at me like I had offered him a chair in a room where everyone else was still standing. He rested his forehead against the glass and breathed once, slow.

In the morning, he brought me coffee with the ratio I like and did not speak of fear as if saying the word had used it up like air from a lung.

To be continued…

Part III

Sterling’s centennial rolled around with the sort of grandiosity that makes city councils rehearse their ribbon-cutting smiles in mirrors. The celebration took over the green that cuts through downtown and turned it into a maze of white tents and donor walls. Our names were large on the banner because Marcus paid for the kind of good press you buy without letting anyone call it that.

I wore red because the stylist Mr. Zhou had hired winked at me and said, “Let the headlines work for once,” and because when I looked at myself in the mirror the color did something to my spine. A small swell pressed against the fabric—a secret that wouldn’t be secret much longer. Marcus asked me every thirty minutes if I wanted to sit without making his voice hover. He watched the pavement like it was a problem that might trip me.

We shook hands and took photos. I learned the names of people I had only ever known by the way they glanced at price tags. Marcus carried me through the event without touching me, the way certain men carry entire rooms.

I stepped outside the main tent to breathe air the crowd had not already processed and saw Willow in the shadow of a pillar. If grief has stages, hers had all set up chairs and demanded a seat at the table. She wore a dress that had been expensive when it was bought by someone else. Her makeup sat on her skin like a mask she had borrowed from a woman who knew how to place it. Her smile was an injury.

Her gaze flicked to my stomach and something in it—jealousy, rage, ruin—flared and went out. She didn’t come closer. Some hungers, once they learn they are never going to be satisfied, retire from the front lines. A young man with a lanyard texted beside her, eyes sliding over her like she was a billboard he’d seen too many times to read anymore. She walked away without performing collapse. For the first time since the church kitchen, I did not feel like a participant in her show. I felt like a witness and then a passerby.

“Grace,” a voice said, and my name did not punch me in the stomach this time. It arrived like a messenger who had been told to knock softly.

Ethan.

If Willow looked worn, Ethan looked hollow. The Northwest sun had darkened his skin and thinned him out, the way deprivation sometimes carves rather than flays. His suit had been pressed by a valet who didn’t understand that no one notices creases if the man inside the suit looks like a bad bet. His eyes were bloodshot in a way that suggested late nights not spent learning new virtues.

“Mr. Lou,” I said, because the formal bluntness freed me from older reflexes.

“I’m leaving,” he blurted. “Another country. I won’t be back.”

I nodded. “I hope you find work that doesn’t require applause.”

He swallowed. “Could we— privately—”

“No,” I said, not unkindly. “We don’t do private well.”

His mouth opened and closed. He reached out, instinct more than intention, the way men do when they want to anchor you to a conversation by touching your sleeve. Before he came close enough for me to decide whether to step back, Marcus was there, a line between us made of jaw and heat.

“What do you think you’re doing?” he asked, not raising his voice.

Ethan flinched and withdrew his hand like he’d brushed a live wire. “I wanted to apologize,” he said, eyes on me, because all of the old calculations had arrived late to a party where they were no longer welcome. “Grace, I— I thought— I believed you would… wait.”

I smiled the way people smile at children being sincere about a thing that is not relevant anymore. “Thank you for not marrying me,” I said. “It’s the kindest thing you ever did.”

Color drained from his face. He staggered back a step and looked, for a second, like a boy outside a church with his tie improperly knotted. We walked past him. I did not turn around.

Marcus was quiet in the car until the lights of downtown thinned. I poked his arm. “Say it.”

He stared at the windshield like it had opinions. Then he pulled over, put the car in park, and held me like someone had just told him I was breakable and he’d realized everyone else already knew. “I am terrified,” he said into my shoulder. “That some part of you is in a room I can’t enter.”

“Marcus,” I said, and put my hands on his face, forcing him to look at a thing he did better than most—recognize an equation that had an answer. “From the beginning, from the kitchen, from the courthouse, through soup and gates and ridiculous rings under stars, there has only ever been one room I wanted to be in. It has your name on it.”

His laugh was a broken, grateful thing. He kissed me, forehead first, as if the brain needed to agree before the body could.

Nine months later our son arrived with the ferocity of a man who intended to be listened to. He came out yelling and then made a sound I didn’t know I needed—contentment. Marcus cried like a man who didn’t know he had been allowed to. Mr. Zhou cried like a man who had seen too many dinners turned into battlefields and was relieved to see a table set for something else. I named the child Peace because I wanted to write it into our days as if language could guard us.

We brought him home. The house felt less like a museum and more like a place where milk could be spilled without everyone resigning. The framed napkin hung in the study and Mr. Zhou pretended to be scandalized when the baby threw a spoon at it. Marcus learned how to fold a swaddle with the seriousness he brought to a hostile takeover. He learned how to burp a newborn without bargaining for better terms.

People asked about Ethan. I said, honestly, that I didn’t know. I didn’t want to. At some point, a headline appeared far down my newsfeed about a mid-level manager in a foreign port who had “left abruptly.” The story was three paragraphs long. I didn’t click. Once, in a café reading the paper like a throwback, I thought I saw him across the street. It could have been anyone. When ghosts stop checking city maps, they fade.

We held Peace’s first birthday in the garden behind the glass. He smashed cake into his hair like he had misunderstood where sugar belongs. We let him. Willow did not RSVP; I had not invited her. She had moved to another city; rumor had it she worked in a showroom where dresses looked better on hangers than on people. I hoped the hours were regular and the men in charge kept their hands where she could see them. That is not forgiveness. That is the minimum I wish for girls who built their lives on mirrors.

Sometimes, late, when the city went quiet enough to hear the refrigerator click, Marcus would stand in the doorway of Peace’s room and look at our son like he was staring at proof that he had not been the man his father made. Sometimes he would turn and see me and say, “I owe a girl in a white dress my life.”

“You paid it forward,” I’d say. “And I took interest.”

The DA’s office finished what it had started. A notary cried in a courtroom and said she was sorry. A firm settled without admitting wrongdoing, which is legal for lying. The judge used words like “abuse of process” and “bad faith actors” and “this court will not tolerate.” The papers ran the story below the fold. That was perfect. I didn’t need page one. I needed ink.

After the gala night under the stars, after Willow in the shadow and Ethan in the hallway, there were still small battles—misunderstandings, schedules, the way two strong opinions collide in kitchens. He would close a door too hard when an email threw a match at his day. I would go quiet in the way women go quiet when they don’t trust the room to hold their volume. We learned. He learned how to arrive softer. I learned how to say, “That hurt,” without adding, “and your mother would have enjoyed it.”

I still kept the herbs he brought the first month. They were useless now—expired and dusty—but I liked the way they took up space. I liked the reminder that he had mismeasured care and then measured it correctly. I liked having proof that people can be taught by love to give it the way it is asked for rather than the way they assumed would pass inspection.

One evening, after Peace had outlawed bedtime again and bribed us with a smile to forget the treaty, Marcus came into the bedroom carrying a box that had not been there before. He placed it on the bed as if it were a proposal. Inside, wrapped in tissue, lay the courthouse ring, the terrace ring, and a third: a slim circle of platinum with a stone that was not ostentatious but took light and did something unarguably beautiful with it.

“Too much?” he asked.

I shook my head. “Just enough.”

He slid it on my finger where it joined the story the other two had been telling. “You know,” I said, tracing the engraving inside the terrace band—G—with my thumb, “you could have told me sooner.”

He nodded. “I could have. But then I wouldn’t have seen you do that thing you do where you choose yourself in a room where everyone expected you to choose them. And I needed to know you would do that, because I plan to spend the rest of my life choosing you, and reciprocity is a vice I have.”

“That’s not a vice,” I said. “That’s survival. And love.”

He kissed me. Outside, neon did its quiet blinking. Inside, breath did its older work.

The very last time I saw Willow was at a stoplight six months later. She stood at the corner with a coffee and a paper bag and the kind of purse that holds more than it should. She looked both ways and did not cross. Our eyes met for two seconds—it is a long time at a stoplight—long enough to tilt the past and look at the underside. She nodded once. Not forgiveness. Not apology. Not even truce. Recognition. Then she walked the other way. I let the light turn green without pressing the accelerator. Marcus didn’t speak. We moved when it was time.

Years later, on mornings when Peace wakes with the sun and the dog we did not plan to get decides breakfast at five is an emergency, I make toast and pour coffee and step out onto the terrace. The city wears weather like a coat. I press my hand to the scar under my ring where soup once fell and think of the girl in the white dress telling a boy a thing she did not know would come true—that tomorrow will be a different day.

It was. It kept being.

When people ask how we happened, I sometimes say, “My fiancé eloped with my sister on our wedding day.” That’s the hook; it lets them think they know the genre. Then I say, “So I married his brother,” and watch their eyebrows perform the gymnastics of judgment. If they are kind and I think they understand what it means to be forgiven by a future you almost said no to, I add, “When he learned, he was angry. But anger is currency that spends itself fast. The man I married deals in longer-term investments.”

They always ask, “Do you regret it?” And I always answer honestly: “I used up regret in a church kitchen. Everything after that has been accountability and luck.”

At night, when the city and the baby and the dog finally nap in their respective rhythms, Marcus and I sit at the kitchen island like conspirators in a better plot. We talk about nothing. We talk about everything. Sometimes he catches my left hand and turns it palm up, tracing the lines like a businessman pretending to be superstitious. “What do you see?” I ask.

He squints. “Long life. Short patience. A husband who got lucky because a girl didn’t let pain make her smaller.”

“And what do you see?” I ask, flipping his hand and threading our fingers.

“Two rings and a promise,” he says.

“Three,” I correct, wiggling the newest band so it flashes.

He smiles. “Three rings,” he agrees. “And a promise I intend to keep until men like me stop wanting to prove it.”

We go to bed. We sleep. We wake. We carry what we choose to carry. The rest, finally, we set down.

THE END

News

My Niece Was Begging for Food, and No One Knew Her Secret… CH2

Part I John Kepler had always believed his brother’s daughter was safe.He’d told himself that after Robert’s funeral. He’d told…

I Cut Off My Family’s Secret Financial Support. They Had No Idea I’d Been Paying Their Bills… CH2

Part I The steakhouse was the kind of place that makes you walk a little straighter, as if the waiters…

My neighbor called, voice tense. “Man, someone’s dril/ling your wife at your house—and the whole neighborhood can hear it.” CH2

Part I My phone rang in the middle of a Friday that had already overstayed its welcome. The stamping press…

Mid-labor, through the pain, I looked up—and froze. The doctor delivering my baby… was my ex. Gritting my teeth, I screamed, ‘Hurry up and pull your son out!’ CH2

Part I There’s a racket the air makes in July when it hits hot pavement and a car with no…

“Reborn, I smiled and said yes—to the man my sister once loved and ruined. She’ll never know what she truly lost.” CH2

Part I The halls at North Ridge High smelled like pencil shavings, old radiators, and cafeteria pizza—exactly the perfume you’d…

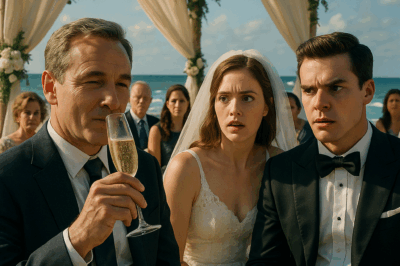

AT MY DAUGHTER’S BEACH WEDDING, HER FIANCE SMIRKED, “PAY $50K FOR THIS LUXURY OR VANISH FOREV… CH2

Part I The champagne flute trembled in my hand, but no one noticed. They thought it was nerves, age, maybe…

End of content

No more pages to load