Part I:

I used to think Christmas at my parents’ house was like a snow globe: sealed, shiny, and fake. You could shake it and watch the glitter drift, but nothing inside ever changed. There was always the same roast—too dry, but no one noticed because compliments were mandatory. The same threadbare tinsel and glass ornaments that cut your hands if you tried to fix them. The same predictable small talk as if we were all acting in a civic theater production called Normal Family, now in its thirtieth year.

I kept showing up, the way people keep pressing a bruised spot just to prove to themselves the pain is still there. It was tradition: dinner on Christmas Eve, gifts on Christmas morning, polite smiles pasted like decals. My mother would do her little ceremony, like the queen of good behavior issuing proclamations: who had “shined” this year and who “needed work.” The words were sweetened by a laugh, a tinkling spoon on a glass, and the varnish of “we’re only teasing.” When I was growing up, it was always me who needed work. The girl with the scuffed knees and straight A’s that didn’t count, the one sent to the kitchen while my older sister Adrienne practiced smiling at angles in the mirror so the camera would love her.

By the time I was thirty-five, married to Dean, with a seven-year-old named Mila who loved loud songs and quiet books in equal measure, I believed I had taught myself to swallow all of it—the pageantry, the small humiliations, the way my parents measured worth in appearances and favors. I told myself I could endure two days of glitter and grit for the sake of the storybook: grandparents, cousins, the big tree, the tin of sugar cookies, the doorway where someone pretended to catch you under the mistletoe.

I told myself a lot of things.

That year, I hung Mila’s red velvet dress next to her winter coat, combed her hair into a loose braid, and let her paint her nails the tender pink she called “peppermint blush.” She hummed the way children hum when they are narrating their own happiness. She believed in magic the way a sail believes in wind.

Adrienne arrived first at my parents’ house—of course she did—her daughters Anna and Stella in matching plaid skirts and patent leather shoes. They were ten and eight and already practiced at looking bored when adults watched them. It was a performance: We are nearly teenagers. But when they thought no one was looking, they were all jitter and eyes, two small comets skimming around the tree, cataloging boxes.

We ate dinner and nodded at my father’s stories about the plant. My mother kept springing up to refresh the coleslaw, which didn’t need refreshing, and to adjust the candles, which didn’t need adjusting. They liked movement; it suggested control. They liked guests to say, “Oh, don’t fuss, everything is perfect,” so they could say, “Well, we try,” and sit back down as if they had just been knighted.

After the dishes, we did the ritual of the couch, the children on the floor, the grown-ups arrayed in a half-circle like judges. The tree in the corner blinked its tired lights. The house smelled like cinnamon, which my mother misted from an aerosol can. Mila scooted forward on her knees and looked up at the ceiling as if the night might open and let a sleigh bell fall through.

Then my father did something he had never done in my entire life. He walked out wearing a red robe, a floppy hat, and a fake beard that looked like someone had glued cotton balls to a potholder.

There was a gasp, a squeal, a theater hush: Santa had entered the room. Mila’s hands flew to her mouth; her eyes were planets. She looked at me with a question that was really a prayer: Is it real? And because I wanted her to have the softness, the miracle, the gentle lie that tells the truth about generosity, I nodded.

“Ho ho ho!” my father said, and his voice was lighter than I had heard it in years. He was making a show. He liked being the center. But even then, even as I clapped and the girls fanned around his boots, something snagged. He hadn’t asked me about Mila’s present; it was still in the trunk of our car, tucked under a blanket. I had planned to sneak it under the tree later, after midnight when Mila slept and the house finally exhaled. I told myself he had a little trinket up his sleeve. A puzzle, maybe. A book. Something small and fine.

He started with Anna. “Santa has seen a very responsible girl this year,” my father boomed, and my mother’s mouth twitched into the kind of smile she saved for good china. Out came a wrapped box. A Nintendo Switch Lite revealed itself under the paper with a chorus of ohhhh from the room. Anna screamed. My mother clapped like she had just won a regional bake-off.

Then Stella. “So kind and caring,” he intoned. “So helpful.” A big box, white and glossy, with a cartoon girl on the front. An American Girl doll with a wardrobe and a tiny suitcase. Stella glassed it up with her hands, showed off the miniature shoes and the little coat, the doll’s hair smooth as a satin ribbon.

Mila sat with her legs folded, fists closed, eyes bright. She was made of waiting, which is what belief is for a child: a kind of breath held without pain.

And then my father reached into the sack and pulled out a small, lumpy bag. He called Mila’s name. She scrambled forward, practically on all fours, and took the bag like it might be fragile. She tore the paper with care. The room leaned in. I leaned in.

Crinkled newspapers. Candy wrappers. An empty yogurt cup. And in the bottom, a palm-sized lump of coal. Real. Black and chalky. A joke from old songs, except the song had never been sung this way.

Silence. The kind that buzzes because it doesn’t know how to die.

Mila frowned at the objects in her palm, then lifted her eyes. “Uh…what—what’s this?”

“That’s your gift, Mila,” my father said in his Santa voice, jovial like a knife is jovial. “Because you’ve been a bad girl this year.”

Something in me turned to ice and heat at the same time. Dean’s hand closed on mine, a pressure that said: Are we hearing this? But I waited for a chuckle, the bait-and-switch where Santa pulls out the real present. There was no second act. There was only my mother’s approving hum and Adrienne’s feline smile.

Mila’s lower lip trembled. “But I’m good,” she said, crying without crying yet.

My father shook his head. “Selfish. You didn’t share your toys. Santa sees everything.”

“But Stella broke my doll,” she said, and every syllable was a try at logic. “I only said no that one time.”

My mother’s eyes were wet in a way that suggested pity for herself. “Santa’s right,” she said gently, deadly. “Good children share. You wouldn’t even hug your grandma. You were noisy, disobedient, disrespectful.”

Adrienne added her flourish: “Exactly. That’s why Santa’s upset. Maybe next year, if you learn your lesson.”

Mila looked at me. And there it was: the first earthquake. She believed Santa himself had ruled on her soul like a judge. She believed the adults who were supposed to light her path had rolled her in soot. She raised her voice, a thin glass scream. “I’m not bad!”

Something in me snapped like a twig that had been held too long in a clenched fist. I stood up. “Enough,” I said, and the word surprised me with its weight. “Cut the crap.”

I walked to my father, grabbed the beard, and tore it off in a single, ugly motion. “See, sweetie?” I said to Mila, pitching my voice low like I was handing her a blanket. “This isn’t Santa. It’s just Grandpa. And this is his pathetic idea of a joke.”

Mila’s eyes were wide lanterns. I could see the double wound: Santa had called her bad, and now Santa was dead. Beside me, Stella started crying, fat tears, “Where’s the real Santa?” she sobbed, and for the first time, Adrienne’s mouth flickered with something like doubt.

Maybe I killed the magic for them all. Maybe. But what my parents had done was not magic; it was a staged humiliation in a red robe.

I took the crumpled trash from Mila’s hands and let it drop to the floor. Then I crouched, even though my knees complained, and I looked squarely into my daughter’s eyes. “You are a good girl,” I said, and I made each word a post to hold up a tent. “The real Santa knows that, always.”

Dean came to us. He scooped Mila into his arms the way you scoop a bird you found stunned on a sidewalk. “Of course,” he murmured. “I bet the real Santa’s gift got misplaced. It’s probably waiting under our own tree. We’ll check when we get home, okay?”

“Okay,” she whispered, a child’s okay that means I want to believe you because I still can.

I turned to the room. To my parents. To Adrienne. “What you just did is cruel,” I said, and I kept my voice flat so it would cut. “You humiliated a seven-year-old and wrecked her Christmas. For what? A power trip dressed up as a lesson?”

My mother lifted her chin, the crown of a petty kingdom. “She needs to learn to behave and understand that actions have consequences.”

“She learned something,” I said. “She learned exactly how her grandparents treat her. And here’s the consequence: we’re leaving. And you will never get another chance to hurt her again.”

Adrienne’s voice trilled, not quite steady. “Oh, come on, Heidi, you’re overreacting.”

My father, unmasked, added with a thin smile, “We wanted to teach discipline. For her own good.”

Dean had Mila’s coat in his hands. He had never moved so fast. We were at the door when my father said, “You’ll regret this.” But he had already been wrong once that night.

In the car, Mila cried the kind of cry that made me feel like I was trying to hold rain in my fingers. I sat next to her, stroking her hair in slow, useless circles. “Why did Grandpa do that?” she asked into my shoulder, so quiet it broke me.

“Because he was wrong,” I said. “He thought it was funny, but it wasn’t. It’s his fault, not yours. The real Santa loves you and would never say those things.”

She was quiet for a long time. “But maybe I really am bad,” she whispered. “Grandpa said it. Grandma too. And Aunt Adrienne.”

There are sentences you wish you could physically pull out of the air before they reach your child’s ears. There are ideas you wish you could banish like moths. “No, baby,” I said. “You are wonderful and kind and brave and so very you. Dad and I love you more than anything. If someone says otherwise, they are wrong. Their words don’t matter.”

Dean’s voice came steady from the driver’s seat. “Remember this, Mila. We’re proud of you. You’re the best kid we could ever ask for.”

She sighed, a tiny surrender to safety, and her body loosened against me. The road unspooled in the dark. I stared out the window and thought, This ends tonight. The cage I grew up in—the polite cage with lace trim—would not be inherited. Not by her.

At home, the tree lights cast a gentle pattern on the wall. The house smelled like real cinnamon and turkey we had prepped the day before. I reheated everything, and we ate at the kitchen table, just the three of us, while the snow made no particular effort outside. We gave Mila cocoa with too many marshmallows. She yawned and wrapped her fingers around the mug like it was a pet. Dean lifted her and carried her to bed. I tucked her in and sat beside her until her breath went even and slow.

In the quiet, I made tea because rituals are scaffolds when the house in your head is falling down. I turned the mug in my hands and replayed everything. The costume. The coal. The chorus of adults making moral theater out of a child’s honesty. That bag of garbage wasn’t an impulse. It was a plan. It was a script they’d written after Thanksgiving, when Mila wouldn’t share something precious that had already been mistreated, when she refused a kiss she didn’t want to give, when she told my father—accurately—that he was grumpy.

They called that spoiled. I called it boundaries. But spoiled fit their favorite narrative: that love is a resource to be rationed and that compliance is the ticket you buy to get it.

I opened my laptop and made the kind of decisions that never make for good movie scenes. Clicks, passwords, deletions. I canceled the monthly transfer to my parents, the pension top-up that was never framed as charity, only as what a good daughter does. I removed my card from their extra health insurance. I deleted the property tax autopay and the homeowner’s insurance I’d been covering since “that one leaky roof year.” I closed the little emergency fund I’d been topping up for their house repairs and car “surprises.” Grown adults can sell a knickknack or call a contractor. Grown adults who play Santa with garbage can field their own bills.

Dean set a hand on my shoulder. “You think they’ll notice right away?”

“Oh, they’ll notice,” I said. “People keep track of rivers you pour into their fields.”

Next tab: Adrienne. I was surgical. Off the family cell plan. Off the internet bundle. Cable severed. All those little “it’s easier this way” arrangements undone. I emailed the dance studio and the art teacher and the camp I had, like a fool, prepaid. “Please remove my card,” I wrote. “Future charges to the parent.” I stopped the school lunch top-up. Schools are very good at contacting parents when the balance hits zero. I didn’t laugh, but something in me relaxed for the first time in years, the way your shoulders drop when you set down a bag you didn’t know was heavy until it’s gone.

The phone stayed quiet for a few days. After New Year’s, my parents didn’t see their usual direct deposit, and Adrienne’s card got declined at the dance studio. The calls began like an orchestra tuning up—first the strings of concern, then the brass of outrage, then the percussion of guilt.

“You must have forgotten,” my mother said.

“I didn’t forget,” I said. “I’m just not doing it anymore.”

“How could you? We’re family.”

“Exactly,” I said. “And family doesn’t humiliate a seven-year-old on Christmas.” I hung up.

Texts from my father: Ungrateful. We raised you. From Adrienne: The girls will lose their activities. Don’t punish them for our disagreement. The word punish made me bark a laugh I didn’t recognize. If only they knew the difference between consequences and revenge.

They tried going around me once, catching Mila at school pickup. My mother bent low and whispered, “It was just a joke, tell your mom not to be mad.” That night, I filled out paperwork for a restraining order. I don’t play with fire once I’ve seen it burn.

We drew our boundary not with chalk but with stone. And inside that circle, our house got lighter. Mila decorated the dollhouse we had bought her—the one waiting under our tree, with tiny lights that glowed like hope—and she made a garden from plastic flowers and paper seedlings. “Rule number one,” she announced, arranging two small chairs at the kitchen table. “You don’t touch other people’s things without asking.” She said it primly, then grinned, and I felt something unclench in my chest that had been tight since I was a girl in a kitchen being told to smile more.

On the second morning after all of it, I found Mila on the rug, braiding the doll’s hair. She looked up and said, as if reporting on the weather, “Mom? I still believe in Santa. Just not the one who was at Grandma’s.” I knelt down. “Me too,” I said. “I believe in the Santa who writes notes in silver pen and smells like peppermint, not the one who keeps score.”

I wanted to tell her everything then: how I had spent years paying tithes to a temple that never loved me back; how I had mistaken obligation for belonging; how I had thought I could buy kindness the way you buy an insurance policy. But she was seven, and she had scraped her knee on grown-up cruelty already. It was enough to be safe. It was enough to be seen.

You hear people say that cutting ties is a last resort, that forgiveness is the moral victory. But there are some ropes that are strangling you, and the merciful blade is the only tool that counts as love. I didn’t draft a speech. I didn’t write a manifesto. I unplugged my life from theirs and waited for the silence to teach me what I already knew.

It did.

And in that new quiet—no buzzing phone, no “can you just” messages, no calendar reminders for someone else’s bills—I heard Mila humming again. I heard Dean whistling off-key in the shower. I heard myself think in a voice that didn’t apologize for existing.

The night they broke Christmas, I thought I had also broken something—the soft myth of Santa, the little glow around the edges of childhood. But sometimes breaking a false thing is what allows the true thing to breathe. Sometimes you have to rip off the beard to find out what you’ll never let in your house again.

I didn’t know yet that what I had done would set off a chain reaction my parents didn’t see coming, that the real consequences were just warming their hands. But I knew this: the snow globe had cracked, and the glitter was real snow now, cold and honest, falling wherever it wanted.

I tucked Mila’s “Dear Mila” book—signed in my careful, loopy “Santa” hand—back under the tree for her to read again in the morning. I kissed Dean good night. The house sighed. And I slept the kind of sleep you get when the lock on your door finally works.

Part II:

The first Monday of January, the air was brittle, like it would shatter if you breathed too hard. I drove Mila to school, her backpack bumping in the backseat. She hummed, still trying out her new guitar pick like it was a jewel. She was lighter, almost buoyant. Children bounce; that’s their gift. But I knew the bruise was still there, quiet beneath the skin.

By the time I pulled into my office parking lot, my phone was already blooming with missed calls. Mom. Dad. Adrienne. A chain of messages in the family chat that lit the screen like a wildfire:

Dad: We need to talk. You’re making a big mistake.

Mom: We can’t pay the house insurance without you. Do you want us homeless?

Adrienne: Anna and Stella were embarrassed at the studio today. My card got declined. Do you have any idea what you’re doing to them?

Dad: You’re punishing innocent children because you’re angry at us. That’s not who you are.

I stared at the words and realized something simple: they had mistaken me for the girl in their kitchen, chopping salad while Adrienne smiled on cue. They didn’t understand yet that the girl was gone.

I put the phone in a drawer and opened my case files. Divorce hearings, property disputes, contracts. People who paid me for the same clarity I had just exercised on my own life: this belongs to you, that belongs to them, draw the line, sign the paper. Justice isn’t always dramatic. Sometimes it’s boring arithmetic.

I worked until lunch. When I opened the drawer, there were thirty new notifications. My father’s last message:

Dad: If you think you can just walk away, you’ll regret it.

Funny. He had said the same thing the night in the Santa robe. He was still wrong.

The fallout began in little cracks. My mother called my office phone pretending to be a client, only to hiss into the receiver when I answered. “You’ve humiliated us. Do you know what the neighbors are saying? That our daughter abandoned us.”

I let her talk until her voice went hoarse. Then I said, “You abandoned me years ago. I just stopped paying rent for the privilege.” Click. Dial tone.

Dean asked me that night if I felt bad. I told him the truth: “Not bad. Free.”

Adrienne cracked next.

It started at the school pickup line, where she cornered me between SUVs. Her girls sat in the back seat, arms crossed, pretending not to watch. Adrienne’s lipstick was smeared, her hair frizzing in the winter air.

“You can’t just cut me off,” she hissed. “The girls need their lessons. Do you want them to fall behind their friends? Do you want them to be the only ones without—”

“Without what?” I asked. “Dance costumes? New iPhones? I thought you said you wanted them to grow up humble.”

“That was before my husband left,” she snapped. “You don’t know what it’s like to be alone.”

“I know exactly what it’s like,” I said. “I was alone in that house for decades. And you helped make it that way.”

Her face pinched, but I wasn’t finished.

“You’ve mistaken me for your safety net. I’m not. Not anymore.”

“You’re heartless,” she spat, and slammed her door so hard the window rattled.

From the back seat, Stella’s voice floated out before she could stop it: “But Mom, maybe we can just…not do dance this year?” Adrienne shushed her violently. I walked to my car with something that felt like justice but burned like fire.

January rolled into February, and my parents started showing teeth. Letters arrived in my mailbox—handwritten, dramatic, underlined words. We sacrificed everything for you. We raised you. You’ll be sorry when we’re gone.

I shredded them without reading the endings.

Then they tried a different angle: shame. They called my in-laws, left voicemails about how “our daughter has turned cruel,” how Mila was being “poisoned against her family.” Dean’s parents, practical people from Minnesota, called us after listening to one such voicemail. His mother’s voice was dry as toast.

“Well,” she said, “sounds like they’re desperate. Don’t worry, honey. We know who you are. And we’re proud of you.”

That was the first time I cried since Christmas. Not because I was weak. Because someone said we’re proud of you without conditions. I had waited thirty-five years to hear it. It came from the wrong parents. And it was enough.

But if my parents were fire, Adrienne was smoke. She spread stories in whispers: that I had grown cold, greedy, selfish. At the grocery store, old neighbors gave me looks that said how could you. At church, someone asked if it was true I had “cut my mother off.”

I smiled. “Yes. Isn’t it wonderful?” Their shocked face was better than communion wine.

Through it all, Mila healed in small increments. One night she crept into our room holding the “Dear Mila” book from Santa, and whispered, “Mom, do you think Grandpa still thinks I’m bad?”

I pulled her into bed and kissed her hair. “Sweetheart, Grandpa’s opinion doesn’t matter. The only people who get to decide who you are…are you and us. And we know the truth. You’re kind. You’re brave. You’re loved.”

Dean added, half-asleep but sharp as ever: “And the coal? That was his mistake. He should’ve kept it for himself.”

Mila giggled. It was the first time she laughed about it. That sound was worth every battle I’d started.

March brought court dates. My restraining order application against my parents was scheduled for hearing. Dean came with me, suit pressed, jaw tight. The courtroom smelled like dust and stale air. My parents sat across the aisle, rigid, their lawyer whispering.

The judge asked me to state why I believed the order was necessary. My throat was dry, but my voice was steel. I told the story: the Santa suit, the garbage, the coal, the humiliation. The phone calls to Mila. The ambush at school.

My mother dabbed her eyes. “It was just a family joke,” she said.

The judge’s eyebrows rose. “A joke?”

My father cleared his throat. “We were trying to discipline her. That’s our right as grandparents.”

The judge leaned forward. “Discipline does not include emotional abuse. Especially not staged in front of other children.”

The gavel fell like thunder. Order granted.

As we walked out, my father muttered, “Ungrateful. You’ll regret this.”

Dean leaned close to me and said, “Funny. That’s three times he’s been wrong.”

Spring thawed the snow, and our life grew lighter still. Mila started guitar lessons, tiny hands on big strings. She sang off-key in the living room, her voice fearless again. Dean worked on the porch, fixing a loose railing. I argued cases, signed contracts, cooked dinners.

And slowly, the silence around us stopped feeling like absence. It felt like space. Like air. Like breathing.

My parents stopped calling eventually, though their shadow lingered in the form of rumors. Adrienne grew sharper, more brittle, until even her friends started avoiding her. I heard whispers that she might lose her apartment. That she was asking around for loans. The old me would have rushed in, wallet open. The new me made tea, sat with Dean, and said, “Not my problem.”

And it wasn’t.

The ledger was clean now. I had erased the debts I never owed. But fire leaves scars. Some nights, I woke with the memory of Mila’s voice—But maybe I really am bad—and it knifed me. Some scars are invisible, but you feel them every time the air changes.

One such night, I found myself in the kitchen, tea steaming, staring at the window. Dean padded in, hair mussed, eyes half-shut.

“Can’t sleep?” he asked.

“Just thinking.”

“About them?”

I nodded.

“You know,” he said, leaning against the counter, “you didn’t just end it for Mila. You ended it for you. That’s the real gift.”

I looked at him, at the man my family had dismissed as boring. And I thought: boring is peace. Boring is safe. Boring is gold.

By June, six months after the coal, Mila had her first recital. She strummed clumsy chords on her kid-sized guitar, the notes wobbling but true. Dean and I clapped until our hands hurt. She bowed, cheeks red, eyes shining.

On the drive home, she said, “Mom, Dad? You know what? I don’t care what Grandpa thinks. He doesn’t know music anyway.”

We laughed. And that laugh was the final cut of the scissors. The tie was gone.

I had worried that breaking from them would feel like exile. Instead, it felt like opening a door. For the first time, Christmas wasn’t looming like a storm. It was a season we could shape ourselves. No pageants. No coal. No garbage. Just light.

And in that light, I saw clearly: the fire I had walked through hadn’t burned me. It had burned the cage.

Part III:

Summer came in thick and humid, the kind of air that made curtains stick to the window frames. Mila spent her days barefoot, running through sprinklers, her laughter stitching the backyard together. Dean grilled on the patio while I sat at the table with case notes, the smell of charcoal and cut grass in the air.

It felt like a new life, one that didn’t require permission or apology. But freedom is never free—it comes with a price tag, and sometimes that tag is other people’s rage.

Adrienne was the first to show the cracks.

It started with whispers through mutual friends. “She’s behind on rent.” “She’s pulling the girls from camp.” “She asked if she could borrow money for groceries.”

At first, I felt the old tug—the reflex to reach for my wallet, to solve her problems so mine wouldn’t get worse. But then I remembered Mila clutching that lump of coal, crying, But maybe I really am bad. That was the cost of my generosity: humiliation for my daughter. No more.

Adrienne called one afternoon in July. I let it go to voicemail, then sat at the kitchen counter while her voice filled the room.

“Heidi, it’s Adrienne. Look, I know you’re mad, but this isn’t about us. It’s about the kids. They’re going to be embarrassed at school without the right supplies. You’ve always helped before, and I’m asking you one last time. Please.”

Her voice cracked on the please.

Dean came in, heard the message, and raised his eyebrows. “Well?”

“Well, nothing,” I said. “I deleted my subscription to guilt six months ago.”

He kissed the top of my head, smiling. “Good. Keep it canceled.”

I didn’t call her back.

By August, my parents’ house had begun to show its age. A neighbor mentioned their grass was overgrown, the gutters sagging. Without my monthly transfers, the little luxuries had vanished. No more weekend getaways. No more new gadgets.

I knew they were telling everyone that I had abandoned them. That I was a selfish daughter who cared more about money than family. But the truth was simpler: they had mistaken me for a wallet, and I had corrected them.

One evening, my father left a voicemail that almost made me laugh.

“You think you’ve won, Heidi? You think you can just walk away? But blood is blood. You’ll be back. You’ll regret this.”

That word again—regret. As if it were a curse he could cast by repeating it.

But regret is only heavy when you carry it. I had set mine down.

Meanwhile, Mila grew taller, braver.

She started second grade in September, walking into the classroom with her new guitar pick dangling from her backpack zipper like a badge. When kids asked what it was, she grinned and said, “I play guitar.” Not embarrassed. Not shy. Just proud.

One night, while she was practicing, she looked up and said, “Mom, do you think Grandma and Grandpa are still mad?”

I froze, then asked, “Why do you ask?”

“Because…if they’re mad, it doesn’t matter. Right?”

I hugged her. “That’s exactly right. Their anger is their problem, not yours.”

She nodded, strummed a wrong chord, and laughed. The sound was freedom, pure and clear.

But freedom has a way of drawing fire.

In October, I ran into Adrienne at the grocery store. She looked tired, her hair pulled back in a messy knot, the girls trailing behind her like wilted flowers. Her cart held the bare minimum: bread, peanut butter, milk.

“Heidi,” she said, blocking my path by the frozen vegetables.

“Adrienne.”

Her eyes darted around, as if checking for witnesses. “Do you feel good about this? Watching us struggle?”

I took a breath. “I don’t feel good about any of it. But I feel better than I would if I kept teaching Mila that being used is the price of being loved.”

“You’re twisting it,” she snapped. “We’re family. Families help each other.”

“Families also don’t hand coal to a seven-year-old and call it discipline,” I said flatly. “That night made everything clear.”

Her face flushed. “It was a joke.”

“No,” I said. “It was cruelty. And it cost you my help. Actions have consequences, remember?”

For once, she had no comeback. She turned her cart sharply, muttering, “You’ll regret this.”

That word again. Always that word.

The breaking point came just before Christmas, a full year after the coal.

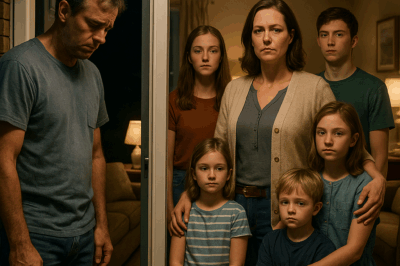

We were decorating our tree when there was a knock at the door. Dean opened it. My parents stood there, bundled in coats, Adrienne hovering behind them. Snowflakes clung to their hats.

Mila gasped and ran to me, eyes wide.

“Stay back,” I said softly. She obeyed.

My father’s voice was hoarse. “We came to talk.”

“There’s nothing left to say,” I replied.

My mother stepped forward, tears streaking her cheeks. “Heidi, please. The holidays—”

“No,” I cut her off. “Not after what you did last year. Not after the way you treated Mila.”

Adrienne’s voice rose, sharp. “You’re being cruel! You’ve turned into someone I don’t even recognize!”

I looked her dead in the eye. “No. I’ve turned into someone you can’t control.”

The silence was heavy, broken only by the sound of snow hitting the porch.

Finally, Dean said, calm but firm, “Leave. Now.”

They hesitated, then turned away, their footsteps crunching on the driveway. Mila pressed her face into my side, whispering, “Are they gone?”

“Yes,” I said. “And they’re not coming back.”

That Christmas, our house glowed like a lantern. Mila woke to find a dollhouse expansion kit, new furniture, and another note in silver pen:

Dear Mila, thank you for being kind, honest, and brave. Santa always sees you. Merry Christmas.

She hugged the note to her chest, smiling so wide it hurt my heart.

We ate cinnamon rolls, played board games, sang carols badly on the guitar. And when the snow fell outside, we didn’t feel trapped. We felt free.

Freedom isn’t neat. It’s messy, with jagged edges and scars.

Adrienne still tells people I ruined Christmas. My parents still complain about their “ungrateful daughter.” Maybe some people believe them. Maybe not.

But here’s what I know:

Mila believes in herself.

Dean believes in us.

And I finally believe that love doesn’t come with a ledger.

That is the cost of freedom: losing the family that only loved you when you paid their price. But it’s also the gift—because the ones who remain are real.

And when I tucked Mila into bed that night, she whispered, “Mom? This was the best Christmas ever.”

I kissed her forehead. “Get used to it, sweetheart. They all will be from now on.”

Part IV:

The year after the coal incident passed like a storm that never stopped rumbling on the horizon. Even when the sky looked clear above our little house, I could feel the thunder of my family’s disapproval somewhere out there, waiting. They were voices in the distance, but I didn’t let them near.

Still, when December rolled around again, my chest tightened. Christmas had always been theirs—my parents’ show, Adrienne’s stage. Now it was ours. And I needed it to be right. Not perfect. Just true.

Dean and I decided early: no pageantry, no scripts. We’d let Mila help shape the holiday.

“Can we make gingerbread houses?” she asked one night.

“Absolutely,” I said.

“And can we eat them before Christmas?”

“Half now, half later,” Dean bargained, grinning.

We baked cookies, hung lopsided ornaments, let Mila tape paper snowflakes to the windows until the glass disappeared under crayon and glue. It wasn’t elegant. It wasn’t curated. But it was alive.

Dean built a wooden sled in the garage, sanding it smooth, painting the runners red. Mila came home from school and gasped when she saw it.

“Is it for me?”

“It’s for us,” he said. “Family sled.”

She hugged him around the waist, and I thought: this is what legacy should look like. Not control. Not cruelty. Just love carved into wood and paint.

Around mid-December, the letters started again.

My mother’s shaky cursive, my father’s blocky script. Adrienne’s slanted handwriting on pastel stationery. They came in threes, as if coordinated.

Heidi, please, the holidays are no time for grudges.

We miss Mila. Children need grandparents.

The girls are asking why their cousins aren’t around. You’re punishing them.

This year has been so hard without your help. We’ve had to cut back on everything. Isn’t Christmas about forgiveness?

I read them at the kitchen counter, then slid them into a drawer. Not ripped. Not burned. Just set aside.

Dean asked if I wanted to respond.

“No,” I said. “The silence says more than I ever could.”

He nodded. He understood.

Two days before Christmas Eve, Adrienne showed up at my office. She walked in without an appointment, without knocking, the receptionist trailing helplessly behind her.

“Heidi,” she said, voice tight, “we need to talk.”

I gestured to a chair. “Make it quick.”

She sat, wringing her hands. “The girls don’t understand why you’ve cut us out. They think they did something wrong.”

“They didn’t,” I said firmly. “But you and Mom and Dad did. And actions have consequences.”

Her eyes brimmed. “Don’t do this. You’re leaving them without family.”

I leaned forward. “No. I’m leaving them without you. There’s a difference.”

She stared at me, searching for weakness. “You can’t just erase us.”

“I didn’t erase you,” I said. “I erased your power over me.”

Her lip curled. “You’ll regret this.”

That word again. Always that word. I almost laughed. “No, Adrienne. I’ll regret if I let Mila grow up believing she’s only loved when she obeys. That’s the regret I won’t live with.”

She left in a huff, heels clicking on the tile. The receptionist poked her head in, eyes wide. “Should I…screen calls?”

“Yes,” I said. “All of them.”

We woke on Christmas Eve to a blanket of snow so thick it muffled the world. Mila pressed her face to the window, whispering, “It’s magic.”

We spent the day sledding down the hill at the park, our laughter echoing through the crisp air. Dean wiped out spectacularly once, rolling into a drift, and Mila laughed so hard she couldn’t breathe.

That night, we lit candles, ate turkey, and opened one gift each: pajamas. Mila’s were red with snowmen. Ours matched. She shrieked with delight when she realized. “We’re a team!” she said.

“Yes,” I whispered. “Always.”

Mila woke before dawn, tiptoeing into our room. “Santa came,” she whispered, eyes shining.

We stumbled to the living room, where the tree glowed, presents piled beneath. She tore into them: books, art supplies, a telescope. And one small box with a note in silver ink:

Dear Mila, thank you for being strong, honest, and kind. Santa sees your heart. Merry Christmas.

Inside was a silver charm bracelet with a single star dangling from it. Mila slipped it on and held her wrist up to the light. “It’s perfect,” she breathed.

Dean put his arm around me. “You did good, Mom,” he said softly.

“No,” I said. “We did.”

That afternoon, while Mila played with her telescope, there was a knock at the door. My stomach dropped. Dean opened it, and sure enough—my parents stood there again, Adrienne behind them.

Mila froze.

“Please,” my mother said, voice trembling. “We just want to see her. Just for a moment.”

Dean blocked the doorway. “No.”

My father’s face hardened. “You can’t keep her from us.”

“Yes, we can,” I said, stepping forward. “Because protecting her is our job. And you failed yours the moment you handed her garbage and coal.”

Adrienne’s voice wavered. “It was one mistake—”

“No,” I cut in. “It was the truth of who you are. And we’re done.”

The silence was sharp as icicles. Then I closed the door.

Mila ran to me, tears in her eyes. “Will they come back?”

“Not if we don’t open the door,” I said.

She nodded slowly. “Good.”

That night, after Mila was asleep, Dean and I sat by the fire. I held the letters from the drawer in my lap. One by one, I fed them into the flames. They curled and blackened, words turning to ash.

Dean squeezed my hand. “Feels final?”

“Yes,” I said. “Finally.”

We watched the fire eat the paper until nothing was left.

Months later, in the spring, Mila wore her charm bracelet to school every day. When her teacher asked about it, she said, “It’s from Santa. The real one. Not the fake one at Grandma’s.”

The teacher laughed, but kindly. Mila didn’t. She was serious.

And in that moment, I realized something. Christmas hadn’t been ruined that night with the coal. It had been rewritten. We had taken it back, made it ours.

Not about appearances. Not about control. Just about love, simple and steady.

The cost of freedom was high—silence, rumors, lost family. But the reward was priceless: a daughter who knew she was good, and a home where no one ever had to earn love again.

When I tucked Mila into bed that Easter, months past the holiday that had once broken me, she whispered, “Mom? I’m glad Santa likes me.”

I kissed her forehead. “Sweetheart, Santa doesn’t just like you. He loves you. Always.”

She smiled, closed her eyes, and drifted off, safe in the knowledge that some magic is real—the kind you make yourself when you finally choose freedom.

The End.

News

PART II: He Threw His Wife and 5 Children Out of the House… BUT WHEN HE CAME BACK HUMILIATED, EVERYTHING HAD CHANGED! CH2

The discovery of Octavio’s remains hit Guadalajara like a storm. It was not just news; it was a revelation that…

“I Cheated for 4 Years Long Ago—Now He Refuses to Believe I Ever Loved Him”…CH2

Part I Look, I know how it sounds. I can hear the chorus already—homewrecker, liar, fraud—like a crowd warming up…

My Parents Texted “We Need Space From You, Please Don’t Reach Out Anymore At All” My Aunt Packed… CH2

Part I My name is Eliza Hart. I’m twenty-seven years old, and if you think abandonment kills the soul, wait…

“Husband Brings Pregnant Best Friend Home to Ask for Divorce — I’m Overjoyed and Sign the Papers Immediately.” CH2

Part I The night began with the kind of soft, golden light that makes even a quiet Seattle living room…

Mistress Mocked Pregnant Wife In Court—But Judge Asked Her One Question That Ended It All… CH2

Part I: The cold, sterile air of the Mecklenburg County Courthouse in Charlotte carried the weight of broken promises. The…

📕I Cared for Her Through Cancer—stood by every chemo and fear—yet she married her first love instead… CH2

Part I: The first time the chemo pump beeped, I thought it sounded like a bedside alarm—one of those cheap…

End of content

No more pages to load