Part I

The courtroom was quiet, but not the kind of quiet that helps. It was the kind that made every breath sound like an excuse and every heartbeat sound like a confession. I’d dressed Zaden in a little gray jacket with brass buttons that morning because my mother said judges notice neatness. He was eight and too small for the bench; his legs swung with a rhythm that didn’t match anything happening in the room.

Damian stood at the table with his attorney like he was posing for a photograph he planned to frame. The suit was new. The smirk was not. He nodded at our son the way you nod at a stranger who recognizes you but doesn’t know you. He didn’t look at me. He rarely does when there’s an audience.

The judge—Callahan—wore his glasses halfway down his nose, flipping papers with the slow care of a man who wants you to know he can make you wait. When he looked up, the air changed.

“Mr. Carter,” he said, “you’re asking for a change in custody. You’ve told this court your son has expressed a desire to live with you. Is that correct?”

Damian’s confidence grew a size in the space between question and answer. “Yes, Your Honor. Zaden told me he’s not comfortable in his current living situation. He wants to live with me full-time.”

The words landed like stones. I didn’t look at Damian. I looked at my son. His fingers were knitted together in his lap. He didn’t look scared, exactly. But he looked like a boy doing long division in his head while the room wanted him to perform a magic trick.

Judge Callahan turned those steady eyes toward Zaden. His voice softened, the way people think you should talk to children. “Son,” he said, “is that true? Do you want to live with your father?”

Everything in me stopped. My heart, my breath, my instinct to stand up and shout that this wasn’t fair, that you don’t put a child on a stage and ask him to pick between love and relief. I kept my hands folded and my mouth closed because somewhere in the mess of the last few years I’d learned silence can be stronger than screaming.

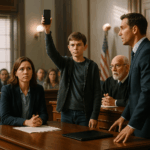

Zaden stood. He didn’t answer. He reached into his pocket and pulled out the old phone I’d given him months ago—the one with the cracked corner and the dinosaur game he liked. He held it up like a hall pass. “May I play the recording from last night?” he asked.

The air left the room like someone had opened a window. The bailiff took half a step forward on instinct; the judge lifted a hand and the bailiff stopped. Damian turned—really turned—to look at our son, and the smirk on his face slid, like a mask that didn’t fit anymore.

“A recording?” Judge Callahan asked.

Zaden nodded. “Yes, sir. From my dad. Last night.” He swallowed and glanced at me, just once. “I didn’t know what to do. I just recorded it so… someone would believe me.”

I’ve had a lot of moments where I wanted to be stronger than I felt. That one sits near the top. I wanted to reach for him. I wanted to tell him we didn’t need proof to be true. But I also knew he’d been living in a world where proof was the only language people listened to.

“Bring the phone here,” the judge said.

Zaden walked across the room, the rubber of his sneakers whispering against the wood. He set the phone on the bench like it was fragile and alive. When he returned to his seat, he didn’t look at me. He slid his hand along the bench until it found mine and he squeezed twice, the way we do at home when the movie gets tense and we both pretend we’re not scared.

The judge pressed play.

People ask me why I stayed with Damian as long as I did. They don’t ask it like a question with room for answers—they ask it like a riddle with one correct solution. The easy one is love. The truer one is fog. You don’t know you’re in it until you realize you haven’t seen your own feet in months.

We met when I was twenty-two and every door still looked like possibility. He filled rooms. I was not small, but I felt like I could be if I stood beside him, and for a while that felt like safety. He noticed things—my laugh, the way I reread the same page when I was tired—and fed them back to me as proof that I existed. I didn’t know some people learn you so they know where to apply pressure when they need you to fit the shape they’ve already decided on.

The boundaries slid like furniture rearranged at night. He didn’t like a few of my friends—said they were bad for me. He wanted me home more—said that was what real women did. When I got pregnant, the rules multiplied like rabbits. He would provide. I would keep house. It sounded like a plan, and plans are seductive when you don’t know how to ask for what you need. By the time Zaden was two, I didn’t have a debit card. I didn’t drive without texting timestamps. If I wore makeup, I was trying too hard. If I didn’t, I’d let myself go. It didn’t matter, because the script always ends with you being wrong.

The last night was about juice. A red stain on a beige carpet and a five-year-old who wanted to cry. Damian’s voice did that thing—it filled corners, it pressed the air against your eardrums. I stepped between them, shaking because sometimes bravery and terror arrive in the same car. “You don’t yell at him like that,” I said. He turned that look on me—the one I knew too well, the one that always came before a sentence I would have to apologize for later. That night I didn’t wait. I packed a backpack with what I could carry, woke my son, and took the keys off the hook.

We stayed with my mother for two weeks. Evelyn ironed her disapproval into pillowcases and fed me soup without asking the questions I couldn’t answer yet. Then a one-bedroom with thin walls and a door that locked. Two jobs: circulation desk by day, office cleaning by night. The math never added up neatly, but it was our math, and no one demanded more than we had to give. Zaden learned the way the washing machine hums in old buildings and the sound of my keys in the hall. He slept better. I did, too, even when I didn’t.

Damian didn’t fight me for custody at first. Alternate weekends. Drop-offs that always came with a gift I couldn’t afford and a smile too wide. He liked to act like visitation was charity he performed for the less fortunate. Then something shifted six months ago. He arrived with a lawyer in a blue tie and the first suit I’d ever seen him in that wasn’t rented. He wanted full custody. He said I was unstable. He said Zaden wanted to live with him.

Watching him talk was like watching someone explain a painting you’d never seen. I knew it wasn’t true. But I also knew how good he was at making other people believe his version of our lives. He’s always been two people—the charming one who shakes hands and tips baristas, and the one who lived in my house.

In the weeks before the hearing, Zaden stopped sleeping. He asked questions with too much math for an eight-year-old. Who talks first? Does the judge have kids? Will they be mad if a kid says the wrong thing? One night, he crawled into my bed and whispered into the pillow like he was afraid the air would carry his words to the wrong ears. “What if someone lies and people believe them?”

“Then we tell the truth,” I said. “Even when it’s hard.”

He nodded like he wanted to borrow my certainty and tuck it under his own pillow. I didn’t know it then, but he’d already decided to protect himself the way adults fail to do. He’d already looked at the tangled knot and found both ends.

Two days before court, he was quiet after Damian dropped him off. He fiddled with the old phone—my hand-me-down with the cracked corner—like it was a puzzle. “Can I take this with me Monday?” he asked.

“Sure,” I said. “Why?”

“So I can listen to music,” he said. He looked at me a moment too long, then looked away. I didn’t ask more because I didn’t want to be the kind of mother who makes a safe place feel like an interrogation. I also didn’t want to hear the answer.

The morning of the hearing, Evelyn ironed Zaden’s jacket like the judge was going to run a hand along the seams. She kissed his head and told him he was brave without using the word. I drove with both hands on the wheel like if I took one off I might let go of everything.

Inside the courtroom, there were rows of seats, a rail that kept you where you belonged, a bench that sat higher than everyone else. There were lawyers who’d learned how to look grave without actually having to feel anything. There was my ex-husband with his new smile.

When the bailiff said “All rise,” the room stood like it was pretending to be a single body. We sat when we were told. The clock ticked and didn’t apologize. And then Damian did what Damian does—spoke with the authority of a man who never had to stay to clean up the messes his sentences made.

“Zaden told me he wants to live with me,” he said, and the lie fell with the dull sound of a familiar thing.

When the judge asked my son if it was true, every muscle I had wanted to catch him, hold him up, take this down for him. But my boy stood up, put his small hand in his jacket pocket, and pulled out the one thing he thought could talk louder than both of us.

“May I play the recording from last night?” he asked.

He carried the phone across the room like it was the only honest thing we had left. He gave it to the judge and sat back down. He found my hand. I squeezed twice and he squeezed back, like we were counting.

The recording started with static—the sound of a cheap microphone in a dark kitchen. Then his voice—Damian’s—sharp, familiar, too close to the speaker. “If you don’t say you want to live with me, I swear I’ll make sure your mother disappears. You understand me?”

There was a hitch on the audio. I watched my son hear his own breath again. “But I want to stay with Mommy,” his small voice said, too careful, like he was holding his words with both hands.

“That’s not your choice,” Damian snapped. The pop of a consonant made the room flinch. “You’re just a kid. Say what I told you or things are going to get worse for her.”

Something moved in the gallery—the human sound people make when they’re trying not to say what they’re thinking. I didn’t look at anyone. I watched the judge listen.

When the recording ended, Judge Callahan didn’t speak. He took off his glasses, wiped them with a cloth he pulled from his sleeve like a magician, and put them back on. He pressed play again. The words ran through the room a second time, dragging every lie Damian brought to the courthouse like a net.

“Mr. Carter,” the judge said finally, looking at Damian the way you look at a stain you can’t explain. “Is that your voice?”

Damian’s mouth opened and nothing sensible came out. He looked at his lawyer, who leaned in like he thought he could be a life raft. The judge didn’t wait.

“Did you threaten your son last night?”

Before Damian could answer, the judge turned to me. “Ms. Ray,” he said, using my last name with a formality that felt like protection, “has your son ever expressed concern for your safety before this?”

I cleared my throat. “Yes, Your Honor. He’s been… afraid. Especially after visits. He’s asked if people will believe the truth.”

The judge nodded once. “Court will recess for fifteen minutes,” he said, voice even, like he had to keep steady or he’d break something he couldn’t fix. He banged the gavel and the sound was an agreement the room had to accept.

People stood. Lawyers conferred. The bailiff put a hand on a man’s shoulder who didn’t need a hand yet but maybe would. I didn’t move. My legs were concrete.

“You recorded that?” I whispered to my son, turning toward him like I was asking for rain.

He nodded. His eyes shone, but no tears fell. “I didn’t know if they’d believe me,” he said. “I thought maybe they’d believe him.”

He looked so small. He looked so big. He looked like a person who’d learned the rule I didn’t know how to teach him: when the truth isn’t enough, you bring proof to hold its hand.

My mother came to us from the gallery. Evelyn crouched until she was eye level with a boy who had just done a very adult thing. “You raised a brave one, Marley,” she said without looking away from him. “You did that.”

“I didn’t,” I said, and she squeezed my wrist the way mothers say a thousand sentences at once.

When the judge returned, the courtroom stood again, like it was pretending to be respectful. The gavel hadn’t even settled when I knew something had shifted. The quiet was different. It wasn’t the silence of dread. It was the kind of quiet you get just before someone says the right thing.

“I have reviewed the recording multiple times,” Judge Callahan said. “There is no question that it is authentic. Mr. Carter, your voice, your words, and your intent are clear. You threatened a child in an attempt to influence the outcome of this case.”

Damian exhaled like a badly punctured tire. His lawyer stared at the table as if it would save him.

“Effective immediately,” the judge went on, “your petition for a change in custody is denied. All visitation is suspended pending a formal review. You will undergo psychological evaluation and complete a parenting program before this court will consider supervised visitation.”

He turned to Zaden. “Young man,” he said, and the words wore something like kindness, “what you did today took courage. I heard you.”

Zaden didn’t speak. He nodded once. His hand squeezed mine hard enough to make my fingers tingle.

The gavel came down. People started moving again. This is the part where everyone congratulates their own restraint with a handshake. I didn’t shake anyone’s hand. I turned to my son and put my palms on his cheeks, thumbs brushing away tears that still hadn’t fallen.

“You were so brave,” I said. “You didn’t have to do that, but you did.”

“I just wanted them to know,” he said. “I didn’t want you to get hurt.”

There are sentences that break you and put you back together in the same breath. That was one. I hugged him tightly. Across the aisle, Damian walked out with nothing left to carry. He didn’t look back.

Outside, sunlight was real again. The steps of the courthouse were just steps, not a stage. Zaden looked up at me and the boy I know reappeared—the one who sings to the cat and asks for extra syrup and thinks being an astronaut sounds fun until he hears about the bathroom situation. The fear that had been living in his shoulders was gone.

That was the day everything changed. Not because a judge ruled the way I prayed he would. Because my son found his voice, used it, and believed it mattered.

That night, Evelyn warmed a pot of chicken soup like it was medicine and told us, “Eat first, talk later.” Zaden curled into bed under his superhero blanket. The house settled. I watched his chest rise and fall like I needed to memorize it. “Am I in trouble?” he asked, eyes half-closed.

“No, baby,” I said. “You told the truth. That’s never wrong.”

“Will Daddy be mad?”

“He might be,” I said. “But being mad at the truth doesn’t make it not true.”

He nodded, rolled to his side, and fell asleep faster than he had in months. I sat there for a while and realized my own body had forgotten how easy breathing could be.

In the weeks after, Damian’s lawyer called twice. I let voicemail do the talking. When the calls came from an unknown number at 11:13 p.m. on a Tuesday, I turned the phone over on the nightstand until the light stopped.

Zaden started laughing again. He rode his bike. He asked for waffles and got whipped cream on the dog when he tried to sneak a dollop. One night at the sink with dish soap on his wrists, he said, “I think I want to be a lawyer.”

“Why?” I asked.

“They listen to people who tell the truth,” he said. Then he smiled. “The good ones.”

I opened a journal I hadn’t touched in years and wrote a sentence that felt true enough to keep: My son saved us. Not with anger, not with revenge. With proof.

We talk a lot about protecting children. We do less of it than we should. Sometimes children protect us. Sometimes they remind us courage doesn’t always shout. Sometimes it lives in a small voice saying, “May I play the recording from last night?” and the world rearranges itself to hear it.

I don’t know what happens in anyone else’s courtroom. I know what happened in ours. The quiet that morning wasn’t peace. It was waiting. And my son walked into it and made a sound that changed what the silence meant.

Part II

People think the story ends when the judge bangs the gavel. They imagine credits rolling and soft music and a long hug in a hallway. In real life, the sound of wood on wood is a start gun. What you run toward after that is a life you have to keep building one careful day at a time.

The morning after court, I slipped the old phone—the one that had changed everything—into a zip-top bag and labeled it with a piece of masking tape: Zaden’s Recording — 10/18. I tucked it in the top drawer of my dresser next to a passport I almost never use and the birth certificate I still take out sometimes just to remember what he looked like on paper before he looked like my entire world.

The calls started before breakfast. One from the court clerk, politely confirming the judge’s temporary order in writing; one from a social worker named Chelsea who would be handling the supervised-visitation intake; one from a detective who said the district attorney’s office wanted to talk to me about a potential charge—witness tampering, they called it—with the kind of clinical distance that made me simultaneously relieved and nauseated.

“Do I have to bring Zaden in for another interview?” I asked, already picturing my son under fluorescent lights with a stranger holding a clipboard.

“Not if the recording and the judge’s transcript suffice,” the detective said. “We have what we need. If anything changes, we’ll go through CPS with a child advocate present. We’re not going to put him through more than necessary.”

I thanked him three times because I didn’t know what else to do with the sudden threat of relief in my throat.

Evelyn showed up with a new padlock for our storage closet and a bag of groceries she pretended was a coincidence. “Soup again?” I asked, smiling despite myself.

“Therapy in a bowl,” she said. “You can roll your eyes, but you’ll eat two helpings.”

Zaden padded out in socks with misfit stripes, hair flat on one side from sleep. He pushed into me at the sink like a cat and I wrapped an arm around him without turning off the water. “We could both call in sick and spend the day under a blanket,” I murmured.

He tipped his head back to look up at me. “I have P.E., though,” he said, serious. “Coach says we’re running the tall cones.”

“Ah,” I said. “Tall cones.”

“You can come,” he added quickly, like he didn’t want to make me feel left out.

“I’ll be there at the fence at 1:30, shouting ‘tall cones’ as if I know what it means,” I promised.

He smiled for real. It was small, but it was all sunlight.

Two days later, we sat in a beige room with a couch that had survived too many families and a bookshelf full of dog-eared parenting books. A woman with kind eyes and a stern chin introduced herself as Rachel, a licensed clinical social worker who’d see us weekly for a while. The state would cover it, she said. Usually, sentences like The state will cover it make me suspicious, but this time it felt like a door.

She spoke directly to Zaden in a tone I recognized—soft but not condescending, practical but not cold. “Do you know what I do?” she asked.

“You help kids talk about big things when their throats feel small,” he said. Evidently my son speaks fluent metaphors.

Rachel didn’t hide her smile. “Exactly. You don’t have to tell me everything today. You don’t ever have to tell me something if you don’t want to. We can play checkers or draw or build a city with blocks. We can talk about the best French fries in town instead of anything heavy. The goal is simple: when you leave this room and go home, your shoulders sit lower than they did when you walked in.”

By the third session, the Jenga tower on her coffee table had more secrets than a diary. He didn’t spill them; he set them gently in the space between pulls. “When you made the recording,” she asked once, not even looking at him, eyes on the way her piece slid out without toppling the whole structure, “what did your stomach feel like?”

“Like it swallowed a bee,” he said.

“What made you press the button anyway?”

“Mom says truth is like a flashlight in a bad basement,” he said, stacking his piece on top. “I brought my battery.”

I cried silently, ugly, behind a tissue Rachel offered me without commentary.

The email about supervised visitation came with seven attachments and a tone that made me wonder if I had accidentally enrolled in summer camp. The visits would take place at The Bridge Room, a facility decorated in primary colors to remind everyone emotions have options. There would be cameras, two-way mirrors, a staff person in the room to make sure nobody said anything they shouldn’t. There would be toys and puzzles and a sign-in sheet.

“You don’t have to send him,” my attorney said on the phone. “You can ask for a continuance; you can argue it’s too soon. The court may push for early reunification attempts if the evaluation comes back favorable, but it’s your call. You know him best.”

I looked at my son on the floor building a fortress out of LEGOs with more towers than sense. “If we say yes now,” I asked, “can we say no later if it goes badly?”

“Yes,” she said. “You can say no any time it’s not safe or healthy.”

I hung up. “Buddy?” I said, sitting cross-legged next to the fortress. “There’s a place where kids see their dads with other grownups watching to make sure everything stays safe. If the judge said you had to go for one hour, and if you knew I’d be in the next room, would you want to try?”

He pressed a red block onto a blue one and didn’t look up. “Can I bring a timer?” he asked.

“Yes.”

“Can I leave if my stomach eats a bee?” he asked.

“We leave if your stomach even thinks about bees,” I said.

He nodded, and for once, that felt like enough consent to build a small plan.

The Bridge Room smelled like Lysol and crayons. The staffer assigned to us, a woman in her fifties with silver roots and a no-nonsense kindness, explained the rules without surprise. “No talk about court,” she said. “No interrogating. No coaching. If Dad slips, I stop him. If you feel yucky, we end. You don’t have to hug.”

I put my palm flat on the glass of the observation room and watched my son walk in with his timer in his hoodie pocket. Damian sat at the little table, his hands folded in front of him as if waiting to recite lines. For a moment, the old smirk tried to resurrect itself, then remembered where it was and rearranged into something like contrition.

Zaden sat in the chair across from him and took out the timer. He set it to sixty minutes and put it in the middle of the table like a neutral referee. “Hi,” he said. Not cheerful. Not angry. Just a syllable.

“Hey, champ,” Damian said. I could see the staffer’s spine stiffen—champ is sometimes a landmine. “Look at you—big man.”

“We can play Connect Four,” Zaden said, and pushed the plastic grid toward him.

They dropped checkers into the slots. Damian traced the rim of his cup with his thumb. Three minutes in, he started to talk about school lunches. Nine minutes in, he asked about the cat. At the twelve-minute mark, he slipped.

“You know,” he said, voice low, “if you had just—”

“Mr. Carter,” the staffer said, voice firm. “We don’t do ifs about court.”

Damian swallowed and smiled too widely. “Right. Sorry.”

At twenty-two minutes, Zaden won a game and didn’t gloat. At thirty-five, he excused himself to the bathroom, and the staffer followed him down the hall. I met them by the water fountain. “How’s your stomach?” I asked softly.

“It ate a bee and spit it out,” he said. Then, after a sip: “I don’t like the way he looks when he thinks nobody can see him. But Ms. Toni can see him. So I’m okay.”

At minute fifty-nine, the timer buzzed. Zaden stood. “Time,” he said, and put his hands in his pockets. Damian looked up at the camera like a man trying to locate the lens he should perform to next. He didn’t try to hug. He didn’t ask. He just said, “See you next time.”

Zaden walked out and right into me, and that hug he didn’t give his father landed where it belonged.

We tried again two weeks later. Then a third time. Each visit was a lesson in how slowly people change and how much faster kids learn how to hold their own ground. After the third, Rachel asked Zaden if he wanted to continue. He thought hard. “Not every week,” he said. “Maybe… once a month. Moms need weekends. And my stomach needs a break.”

We wrote that on the visitation form under Child’s Preference. The court didn’t laugh. They took it seriously. That felt like a miracle and also like the bare minimum.

Around Christmas, I got a call from a blocked number that didn’t leave a message but sent an email instead. From: Assistant District Attorney L. Sinclair. Subject: People v. Carter. Inside: a line I had to read twice.

The office intends to pursue a misdemeanor charge of intimidation of a witness / victim. You and your son will not be required to testify. We are filing based on the recording and judge’s findings. We will keep you apprised. Please contact Victim Services for support resources.

I pictured Damian Carter and the State of Whoever We Are printed on the same piece of paper. It should not have felt like justice; it felt like weather changing. Evelyn put a hand on my shoulder when I showed her. “Accountability is work,” she said. “Let the state do some of it for once.”

I put the old phone back in the drawer and slid it shut. The hum of the house sounded a little like mercy.

On a Saturday in March, Zaden and I sat at the kitchen table with a stack of magazines and a glue stick. His class was making collages of Things That Make You Brave. He cut out a mountain and a lion and a picture of a bowl of spaghetti. “Comfort food counts,” he told me solemnly.

“What about this?” I asked, holding up a tiny photo of a microphone from a music ad.

He studied it. Then he shook his head. “Not microphones.”

“Why not?”

“Because microphones make things louder,” he said. “Brave is what makes things clear.”

“You’re not wrong,” I said.

He paused, scissors hovering. “Should I put a phone?” he asked. “Or is that weird?”

“It’s your collage,” I said. “And phones are just tools. It’s the hands that matter.”

He nodded, cut a tiny rectangle from the corner of a full-page ad, and pasted it in the bottom right. He drew a gold star next to it with the marker that always leaves a smear on his palm. “Not too big,” he said. “Just to remember.”

That night, after he went to bed, I found my old journal and opened to the page where I’d written that he’d saved us with proof. Under it, I added: He saved himself with clarity.

People started finding me. A woman from Zaden’s school pulled me aside after pickup and cried in the nurse’s office because her ex was trying to rewrite their daughter’s fear. I gave her the number to Chelsea at CPS and the name of the free legal clinic that helped me with my first forms. She texted me a week later: Thank you. She told them.

A man from my building whose English is better than his nerves asked if I would look over his petition for a protective order. I made him tea and sat with him on the stoop while he practiced saying things he hadn’t said out loud. He won his order. He left a plate of cookies at our door with a note that said, For the brave kid.

I didn’t set out to be anyone’s anything. But it turns out people whisper to each other in the aisles between canned tomatoes and cereal when they think they might be allowed to fight. If Zaden was brave enough to talk, maybe they could be, too. The world didn’t get softer. People did.

The second hearing—Review of Visitation and Final Orders—arrived in June with heat that made the courthouse smell like old paper. Damian’s psychological evaluation came in at four skinny pages with big words arranged into the sentence we all already knew: prone to coercive control; limited insight; high need for power; low tolerance for challenge. The recommendation at the bottom looked like a concession and a warning: Supervised contact only; monthly; subject to the child’s stated wellbeing.

He wore a different suit. The smirk put itself back together during the elevator ride and tried to climb onto his face again. It didn’t fit any better.

My attorney spoke first, then his. The words were careful, the way you talk when you know there’s a transcript that will follow you. Judge Callahan listened with the patience of a man who had learned silence is sometimes a better tool than a gavel.

“Mr. Carter,” he said finally, “have you completed the program?”

Damian handed over a certificate like a child at show-and-tell. “Yes, Your Honor.”

“And your evaluation?”

His lawyer stood. “Submitted to the court.”

The judge glanced at the paper, then back up. “Here is the order of this court: custody remains with Ms. Ray. Visitation continues at one hour per month, supervised, contingent upon the minor’s preference and ongoing therapeutic input. No phone calls, no unsupervised contact. You will not contact Ms. Ray outside of scheduling through the court-approved app. If you do, I will revisit sanctions.”

Damian looked like he wanted to argue. The judge lifted a hand. “You have already spoken too loudly where quiet was required.”

He turned to me. “Ms. Ray, the court commends your provision of a stable home. I encourage you to maintain the child in counseling as long as he finds it helpful.”

“I will,” I said. My voice did not shake.

When it was over, we walked outside into light that felt like it had been waiting for us. Evelyn kissed Zaden’s head and said, “Ice cream,” like a benediction. Zaden chose shark sprinkles. He drew teeth on his napkin while I signed the last of the forms with a pen that kept skipping. I didn’t mind writing letters twice. I liked the look of my name when I took my time.

That night, I tucked him in under the superhero blanket. “Do you want to go to the visit next week?” I asked. “You can say no. You can say maybe. You can say yes now and no later.”

He considered, the way he does when the stakes are orange-juice-versus-apple-juice high. “I’ll go,” he said. “I’ll bring the timer. But can we get tacos after?”

“Tacos after,” I said. “Every time.”

He grinned, then grew serious. “Mom?”

“Mm?”

“Can you keep the phone in the drawer still?”

“Yes.”

“Will we ever need it again?”

“I hope not,” I said. “But hope isn’t a plan. The plan is the drawer.”

He nodded, satisfied. He closed his eyes. “Good plan,” he said, already halfway to sleep.

Years don’t jump forward in stories the way they do in real life. They move in small increments—homework, checkups, sneakers in bigger sizes, new teachers who pronounce his name right on the first try. But important things happen in increments, too. Zaden’s shoulders, which used to live just under his ears, learned to lower themselves. His laughter came back with roots and branches. He joined a robotics club and built a claw that could pick up a marshmallow and a pencil with the same gentleness. He learned to make pancakes without burning the first one. He slept. I slept. Evelyn retired from her part-time at the florist and started coming to his soccer games with a thermos of coffee and a commentary that made other parents lean in to hear.

The visits continued monthly. Sometimes he went, sometimes he didn’t. When he felt generous and strong, he would sit for the hour and play a board game with his timer on the table. When he didn’t, he would say, “Not this month,” and we would go to the park instead. I stopped waiting to see if Damian’s face would change into someone new. I let the man he was be the man he was, in a room with a staffer and a clock and my boy’s boundaries.

Around Zaden’s tenth birthday, Rachel asked if he wanted to stop seeing her. He looked at me first, which he no longer does for every question, and then at her. “Can I come back later if my stomach eats a bee?” he asked.

“You always can,” she said.

On our way out, the receptionist let him pick a prize from the basket for graduating from therapy. He chose a tiny flashlight on a keychain and clipped it to his backpack. In the car, he turned it on and shone it into the cup holder. “Truth,” he said, approving. “Portable.”

I laughed so hard I had to pull over.

The last hearing—Final Order—was shorter than I expected. It was formalizing what had already been true. Judge Callahan read the findings in a tone that suggested he’d stopped needing to make words sound important for them to be. “Full legal and physical custody with Ms. Ray. Supervised visitation at one hour per month, subject to the child’s preference, to continue for twelve months at which time the court will review. Mr. Carter shall have no unsupervised contact. He shall complete an additional parenting course if he wishes to petition for modification. Any communication shall go through the app.”

He looked at me once more. “Ms. Ray, thank you for protecting your son from the adults’ fight.”

“Thank you,” I said, and meant for seeing us.

Outside, the sky had every color it could hold. Zaden ran down the courthouse steps and jumped the last two like he was jumping into a pool. “Tacos?” he called over his shoulder.

“Tacos,” I said. “And a milkshake if you tell me the joke you didn’t finish in the car.”

He grinned. “Deal.”

On our way to the car, I turned back to look at the building one last time. I don’t know if anyone else does that. Maybe they hurry away. For me, it felt important to say goodbye to the place where my son had found his voice. I didn’t owe it gratitude, exactly, but I did owe it acknowledgment.

In the glove compartment, an envelope with my handwriting on it waited: For Zaden, when he’s older. Inside were copies of the orders, the letter to myself from the night after court, and a photo Evelyn had taken of me and my boy on the courthouse steps, my hand over his like we were sealing something important.

At home, we ate tacos with too much lime and watched a movie with a talking dog who learns his kid doesn’t need him to be brave. I tucked him into bed. He reached for the flashlight on his backpack, clicked it on, and shone it at the ceiling. A circle of light, steady. “Mom?” he said, eyes on the glow. “When I’m old, like forty—”

“Rude,” I said.

“—when I’m old and I have a kid, and if something like this happens—”

“I hope it doesn’t,” I said.

“I know. But if it does—will you give me the phone from the drawer?”

I took a breath that felt like the first one all day. “I’ll give you the phone,” I said. “And the journal. And the flashlight.”

He smiled into his pillow. “Okay,” he said. “Good plan.”

He fell asleep. I stood in the doorway longer than necessary, watching the small rise and fall that makes every other part of the story worth telling.

Then I went to my room, opened the top drawer, and touched the plastic bag gently. Not worship. Not fear. A cataloging. Evidence of what a small voice can do in a room that mistakes itself for power.

People want the story to end with the phone. I don’t blame them. It’s cinematic. But the real ending is a boy’s breathing evening out because he knows his truth will be believed. It’s a woman waking up and not bracing for the day. It’s a grandmother bringing soup and locks and showing up and never saying “I told you so.”

It’s tacos after a hearing and a flashlight clipped to a backpack and a timer on a table that buzzes no matter who wants it to stop.

And yes, somewhere in it, a cracked phone in a drawer, resting. Not needed every day anymore. A reminder: brave is not a microphone. It’s clarity. It’s proof. It’s the quiet conviction that when someone asks you to choose between your safety and someone else’s performance, you reach into your pocket and pull out your good plan.

Part III

By April, the house had learned to breathe at night.

Sleep came without bargaining. The dishwasher’s hum sounded like routine instead of survival. On Saturdays, we made waffles and Zaden perfected the art of sneaking whipped cream without leaving evidence, which meant I found little constellations of sugar on the cabinet we both pretended not to see. At school, he joined robotics, a club that attracted kids who are very sure machines make more sense than people. He loved it. Evelyn sat at the kitchen table threading wires with him one afternoon and declared, “These screws are smaller than my patience,” which is how the cat acquired the name Patience when Zaden insisted the universe had made a pun and we had to honor it.

On a Thursday in late spring, the school held Bravery Night, which is something only elementary schools can organize without irony. Parents balanced phones and toddlers. A banner in Comic Sans told us COURAGE IS A MUSCLE. In the multipurpose room, kids read poems about trying the monkey bars again, about telling the cafeteria lady they didn’t want peas, about swimming without floaties. When it was Zaden’s turn, he didn’t pick a poem. He stood behind the music stand, clicked his tiny flashlight on, and shone it at the ceiling.

“Sometimes brave is loud,” he said, voice steady enough to make Evelyn grip my wrist, “and sometimes brave is clear. This is my flashlight. It’s not big. But it helps.”

He didn’t say anything else. He clicked it off and went to sit cross-legged with his class. The room didn’t clap right away. Then—like people remembered how to be an audience—we did. Loudly. He didn’t smile. He tucked the flashlight into his pocket like a secret. On the drive home, he said, “Ms. Hahn asked if I wanted to read the poem about the lion. I said lions are obvious.”

“You’re insufferable,” I said, and he glanced at me in the rearview mirror and grinned. “I’m your son,” he said.

We kept the monthly supervised visits at The Bridge Room because keeping them meant we chose the terms. The timer was always on the table; Ms. Toni always sat in the corner with a clipboard that could have been sheet music for the way she knew when to make a note and when to let silence play out. Some visits were awkward but uneventful—Connect Four and questions about school projects and him saying “fine” the way children do when they mean I’m not giving you more. Twice, Zaden opted out and we went to the park instead and raced to the third bench and pretended not to notice that I let him win.

The third Thursday in May, the air tasted like rain and impatience. We arrived early. Zaden set the timer and his tiny flashlight on the table like a treaty. Damian walked in ten seconds late with an expression that wanted to be a smile and couldn’t remember how. For the first twenty minutes he played by the rules. He asked about Patience. He asked whether Zaden still liked the blue cleats or the green ones. He lost two games and didn’t make a fuss. Then, while Zaden slid a red checker into the fourth slot, Damian leaned forward, voice dropped to a whisper he must have believed wouldn’t carry.

“If you tell the judge you want more time with me, I’ll get you the gaming system you wanted. We can—”

“Mr. Carter,” Ms. Toni said, not looking up. “Rule number three.”

“I’m just—” he started.

“Rule number three,” she repeated, and her tone made even the clock behave.

He sat back, rocked the chair on two legs, then let it thump onto the floor. Thirty-one minutes. The timer ticked louder. At thirty-four minutes, he tried again, softer, threaded into a sentence about summer camps: “We’d have a big house. Your friends could come over—all you have to do is—”

“Time,” Zaden said, and reached for the timer that still had twenty-five minutes on it.

“It isn’t,” Damian snapped.

“For me it is,” Zaden said, eyes on the plastic grid. He stood, turned to Ms. Toni, and pointed at his stomach. “Bees,” he said.

“Visit ends,” Ms. Toni said, and stood without rushing. She didn’t touch Zaden. She didn’t have to. Her presence made a line in the room. Zaden crossed it. She handed him his flashlight and his timer with an efficiency I wish I’d had three years ago.

I met them in the hall. “Home?” I asked.

“Home,” he said.

Damian’s voice chased us down the corridor, but not loud enough to count as a violation of anything but dignity. “This is ridiculous,” he hissed. “I’m trying. He needs his father.”

In the car, Zaden clicked his flashlight on and off until the small circle found his kneecap. “I don’t like the way he looks when he thinks the rules are breakable,” he said. “I like that there are grownups who know how to say no.”

When we got home, I wrote an email. To: The Bridge Room admin; copy to the court-approved app; copy to my attorney; copy to myself. Subject: Rule Violation During Supervised Visit, 5/19. In the body, I wrote exactly what happened, no adjectives, only verbs and nouns. I attached the form Ms. Toni handed me in the parking lot, her handwriting tidy, her signature crisp. By morning, there was a reply from the administrator: Video confirms staff intervention at minutes 31 and 34. Report forwarded to Court Services. Three hours later, a new email from the court: Emergency Review Set — Monday, 9:00 a.m.

The quiet of that weekend was different than the one in the courthouse months earlier. It wasn’t dread. It wasn’t anticipation. It was the stillness of waiting for a tide you know is coming because the moon is reliable even when men aren’t.

In court on Monday, the lights were terrible and the carpet was worse and none of that mattered. Damian sat at counsel’s table with a new lawyer who kept his glasses on the end of his nose as if the world might reflect differently if he tilted them. Ms. Toni took the witness chair and told the truth the way professionals do—no embellishment, no satisfaction, just the facts arranged in a line.

“Did Mr. Carter attempt to influence the minor’s statements about court during the supervised visit?”

“Yes,” she said.

“How many times?”

“Twice.”

“Did you intervene each time?”

“Yes.”

“Did the minor end the visit early?”

“Yes,” she said. “He indicated he felt unwell. He used the word bees.”

There was a tiny laugh in the gallery. Judge Callahan looked up, not unkindly, and the laughter stopped.

“Based on the reports, the video, and the testimony here today,” the judge said after exactly four minutes of silence and paper shuffling, “this court finds Mr. Carter violated the terms of supervised visitation. Effective immediately, visitation is suspended for ninety days. Mr. Carter will enroll in an additional parenting program, focused specifically on coercive control. Future visitation—if any—will be reevaluated with input from the minor’s therapist and the visitation staff. Any further attempt to manipulate the minor, directly or indirectly, will result in an order of no contact.”

The gavel didn’t sound triumphant. It sounded tired. It sounded like a man who had decided he would spend his career making boundaries for people who never learned how.

Outside, Zaden leaned against the courthouse pillar and watched a pigeon hop sideways on one foot and still make decent time. “Do you think he’ll ever stop trying?” he asked.

“I don’t know,” I said. “It’s not our job to change his car. It’s our job to follow our map.”

He considered that, then nodded as if he had decided to approve of my metaphors. “Can we get dumplings?” he asked.

“Dumplings,” I said. “And if you want, we can eat them on the couch and watch the one with the panda who learns to do karate by accident.”

He didn’t smile. He beamed.

Two weeks later, the district attorney’s office emailed again. Damian had accepted a plea—misdemeanor intimidation of a witness/victim, twelve months probation, fifty-two-week batterer’s intervention program, fines, a five-year protective order for me and Zaden, with criminal consequences for any violation. There was a line about “no admission of guilt required,” which made my teeth grind for a full minute until I remembered acceptance of constraints is sometimes more valuable than an apology a judge can’t enforce.

Evelyn read the email and leaned back in her chair like she’d been holding her shoulders against a wind that had finally softened. “The state did work,” she said. “Let it hold its corner. You hold yours.”

Summer grew on us like a vine. Zaden learned a skateboard trick that made my blood forget how to be inside my veins. He lost his first molar and wrote a note to the tooth fairy explaining inflation. He chose the library’s reading challenge theme—Find the Clue—and arranged the table so kids had to follow a map between book stacks to find the stickers. He put a small basket of flashlights at the end with a handwritten sign: Borrow. Be clear. He brought his keychain trinket and clipped it to the basket with the solemnity of ceremony.

One evening in August, he crawled into my lap on the couch like he hadn’t grown two shoe sizes in a year and said, “Do you think I should change my name to your name?”

I didn’t speak. I let the sentence sit between us like a thing with its own heartbeat.

“I don’t have to,” he rushed. “Kids don’t care. They call me Z. And my name is my name. But sometimes when they take attendance and they say it and then they look at you and then they look at me, I wish—” He stopped.

“You can,” I said. “Or you can wait. Or you can never. You can also add a name instead of replace one. You can be complicated. Complicated is honest.”

“What would you do?” he asked.

“I would ask what name makes me feel safest,” I said. “And then I would use that one every day I could.”

He thought. He nodded. “Can we ask the judge?” he asked. “The one who knows how to tell grownups no.”

“We can,” I said.

A month later, we walked into a different courtroom—smaller, brighter, with a clerk who wore lemon-colored glasses and a sign that said NAME CHANGE PETITIONS—TUESDAYS ONLY. Zaden wore his jacket with the brass buttons and held my hand without needing to. Judge Howell had a smile he didn’t hide and a way of talking to kids like he wasn’t pretending. He asked why Zaden wanted to change his last name.

“Because I like my mother’s better,” Zaden said. “And I live in her house.”

“That’s a perfectly good reason,” Judge Howell said. “And because it’s your choice.”

“Also that,” Zaden said.

The judge stamped the papers in a way that made the lemon-glasses clerk smile. “You are now—” he read carefully, making sure to pronounce each syllable correctly—“Zaden Ray.”

We walked out with a certified copy and two lemon candies from the clerk’s dish. Outside, Zaden tried his new name on like a jacket you’ve wanted for a while and finally have. He spun. “It fits,” he said.

“It does,” I said. “It always did.”

At home, we opened the top drawer. I took out the zip-top bag with the old phone and the masking tape label. I set it on the dresser and didn’t touch it for a full minute. Zaden stood next to me, shoulder against my hip.

“Do we still need it?” he asked.

“Probably not,” I said. “But I don’t believe in throwing away tools that work.” I hesitated. “Do you want to—” I searched for the right verb—“retire it?”

He tilted his head. “Like a jersey?”

“Exactly.”

We made a little ceremony neither of us would admit was a ceremony. We found an old shoebox and lined it with a piece of blue felt. He wrote a note in his careful second-grader handwriting: This phone told the truth. He put the flashlight in beside it, then took it out again and clipped it to his backpack.

“I still need this,” he said. “Sometimes the basement is metaphorical.”

“Insufferable,” I said again. He laughed the deep laugh that makes mothers both proud and terrified.

We slid the shoebox onto the top shelf of the closet where the winter sweaters live. It didn’t feel like burial. It felt like archiving.

By the time school started again, the protective order had become a quiet boundary in our lives—like a fence that was just part of the landscape. Damian violated it once in November with a one-line email that said You know this isn’t over. He sent it at 2:14 a.m., when men like him think the world is asleep and rules melt. The court app logged it; the DA’s office filed a motion; the judge scheduled a hearing and said the word sanctions in a voice that made the meaning clear. Damian stopped emailing at 2:14 a.m.

We marked the anniversary of the first hearing with tacos and a small cake and a polite refusal to make a speech. Evelyn took a picture of us on the couch—me holding the cat, Zaden holding the flashlight. There were no gavel sounds, no costumes. Just a boy and his mother in a living room that had learned how to be simple.

Sometimes people still ask me why I stayed as long as I did. I learned to say two things that are both true: “Because leaving is a process, not a moment,” and “Because I didn’t know I could.” Then I tell them about a cracked phone and a boy who made his voice clear. If they want practical advice, I give them phone numbers and names and the kind of lists you can fold into your pocket and carry to a courthouse. If they want balm, I say, “Soup helps.”

On a Sunday afternoon in late winter, Zaden and I stood on a footbridge over the river that cuts our town in half and argued about whether ducks are brave or just hungry. He found a flat stone, turned it in his hand, and said, “Can I make a wish?”

“You’re eight,” I said. “You can make a plan and a wish.”

He closed his eyes. He threw the stone. It skipped twice. He didn’t tell me the wish because he knows the rules. He opened his eyes and grinned. “Tall cones,” he said for no reason other than the world is better when you bring old jokes with you.

“Tall cones,” I echoed.

We walked home under a sky that promised nothing and gave us the evening anyway. At the door, he paused and looked up at me.

“Hey, Mom?”

“Yeah?”

“I don’t need the phone to tell the truth anymore.”

“No,” I said. “You don’t.”

He reached into his pocket and clicked the tiny flashlight on, shone it at the ceiling of the porch, and then at my face. “But I’ll keep the light,” he said.

“Good plan,” I said.

We went inside. The house breathed. So did we.

The End.

News

My Son Broke a Bully’s Arm. His Father Came For Me, Then I Said The One Word That Made Him Flee… CH2

Part I On Maple Street, the morning always started with sunlight and simple math. Two eggs, over easy. One travel…

Cheating Wife Walked Into The Kitchen & Froze When She Saw Me,”You Didn’t Leave?”… CH2

Part I The saw kicked back and bit deep into my palm, splitting skin like wet paper. A scarlet V…

My Parents Hid My Tumor, Calling It “Drama”—Then the Surgeon’s Discovery Stunned Everyone… CH2

Part I The lump started like a bad idea: small, ignorable, something you tell yourself you’ll “deal with later.” I…

My Dad Left Me On The Emergency Table Because My Sister Had A Meltdown – I’ll Never Forget This… CH2

Part I Antiseptic burns in a way that feels righteous. It bites the skin as if scolding flesh for failing…

‘RACHEL, THIS TABLE IS FOR FAMILY. GO FIND A SPOT OUTSIDE.’ MY COUSIN LAUGHED. THEN THE WAITER DROPP… CH2

Part I The leather folder landed in front of me like a trap snapping shut. I didn’t flinch. I didn’t…

I spent 3 nights watching over my mother in the hospital. I came home one day early. No one was… CH2

Part I My mother always said hospitals breathe like sleeping whales—vast, humming, heavy with the weight of lives passing over…

End of content

No more pages to load