Part I

You never think the sound of clippers will be the sound that saves your child.

It started as a buzz behind a closed bathroom door, a note wrong for a Saturday morning. I’d been folding towels at the end of the hall, listening for the usual soundtrack of teenage life—music through earbuds, the thump of drawers, the thunder of a hairdryer—when the hum turned unmistakable. Clippers. In our house, clippers live in the back of a cabinet for trimming bangs and the dog’s summer paws. They do not, as a rule, sing before prom.

“Reese?” I called. “Kayla?”

Nothing. The hum got louder, bolder. There was a giggle I didn’t recognize and then a sharp inhale, like somebody had backstage discovered the curtain wasn’t ready.

I ran.

Kayla was in pajama shorts and a sports bra, stood in front of the mirror, one hand white-knuckled on the sink. Reese—eight years old, all knees and elbows and eyes too big for her face—stood behind her on a stepstool with the clippers buzzing in her hand. Kayla’s honey-brown hair—her pride, the kind you pay for if God doesn’t give it to you—fell in fat, stunned ropes around her bare feet.

“What are you doing?” The words came out strangled.

Kayla’s eyes flashed to mine and then back to her reflection like saying it out loud would make it too real. Reese didn’t look away. She set the clippers down, put both small hands on her sister’s head—scalp already a stubborn pale crescent—and said, in the serious voice she uses for reading the backs of medicine bottles: “Saving her.”

“Reese,” I said, because sometimes a name is the only thing that keeps you from drowning.

“Mom,” she said back, clippers revived in her hand, “tonight is the party at Jake’s house. He told her he wants her to wear the black dress and curl her hair and that they’re going to talk about their future and then he laughed.” She ran the blades in a neat line behind Kayla’s ear. Hair slid like silk snakes to the tile. “He said stuff when he came over Thursday and I recorded it because you didn’t believe me the other times.”

A tap on the door. My husband, shoulder broad in the frame. “What’s going—”

He stopped. Your husband, for the rest of your life, will have a face you will never forget. That was the face he wore then, one that asked what forest he had wandered into.

“Reese,” he said slowly, “why are you shaving your sister’s head?”

“Because if she looks bad, he can’t take her to the party,” Reese said. “And he can’t do the bad thing he said he’d do.”

Kayla made a small sound at the back of her throat. “It’s just hair,” she said to me, and then, to the girl in the mirror with the bare, brave scalp, “it’s just hair.”

My husband stepped forward and pulled the plug. The clippers whined down like a plane losing altitude. In the silence that followed, the word Reese had said wrong—that adolescent, seventeenth-cousin of saving—thudded in my chest. Saving. Shaving. Maybe the difference mattered less than my bones thought.

“Reese,” I said, softer. “What did you record?”

She reached into the pocket of her pajama shorts and pulled out a pink digital recorder the size of a business card. She held it like a talisman. “He talks so loud,” she said. “You don’t have to get that close.”

“Who?” my husband asked, though he already knew.

“Steven,” Reese said, then pressed Play and the bathroom filled with a voice I had been trying not to hear for months.

The recording was muffled, my kitchen in the background if I strained—cupboards, the refrigerator cycle—but Steven was right there with us, careless in the way boys are when they’ve never been told no and made to keep it. “Jake’ll have the good stuff,” his voice bragged. A snort. “She’ll be fun tonight. She always gets stupid-funny when she drinks. And Tyson’s got something better than vodka, so—” A laugh that turned my stomach. “It’s time, man. Lock her down before she goes to college and thinks she’s too good for me.”

Lock her down. Before college. The words were a toss-and-catch game between boys as if pregnancy were a prank, consent just a syllable they hadn’t bothered to memorize.

“Turn it off,” my husband said, and then he grabbed the counter to steady himself, knuckles white.

Kayla turned, eyes wide, a sheen across them like the linoleum. “I didn’t know she recorded it,” she whispered. “I don’t— I thought if I just— If I didn’t make him mad, he’d—”

The upstairs hall narrowed to a tunnel. A noise started somewhere in the bones of the house, low and mean: a voice on the stairs, a sneer grown legs. “What the hell is this?” Steven said, upside-down in our home, backwards in a house that had fed him spaghetti and permission for months.

He filled the doorway, baseball sweatshirt, cap backwards, that easy boulder looseness boys use when they’ve learned the world is more reluctant to restrain them. “What’d you do to her hair?” he laughed, then saw the recorder in Reese’s hand and stopped laughing.

Something in his eyes went bright. “Give me that,” he said, and the thing behind my heart—the animal that wakes when children are in rooms with men like this—sat up.

“Get out,” I said, and my voice came out steadier than I felt. I pulled my phone from my pocket, thumb finding the red circle I’d never used in my life. “Get out of my house, Steven. Leave now.” I held the screen up like a cross.

He smirked. “You think recording me means anything? My dad’ll destroy you for this. You don’t know who you’re messing with.” Then he shoved my husband hard enough to slam his shoulder into the wall, our wedding photos rattling against drywall like an old joke.

It is important to remember that courage doesn’t feel like courage. It feels like your hands shaking while you use them. I stepped between Steven and my family, held the blinking red light like a candle at a vigil, and said, “Then let him. Get out.”

He backed into the hall, anger a weather front across his face. As he thundered down the stairs he threw his shoulder into the gallery wall, family photos crash-crashing to the steps. We followed, my husband a step behind him, me behind my husband, both of us between Kayla and that boy. Steven yelled about lawyers and false accusations and how we’d be sorry. The door slammed so hard a picture in the hall fell that he hadn’t touched. Then his engine howled and his car peeled away from our curb. For a moment, the house held its breath. Then it breathed again.

We locked ourselves in the master bedroom, the four of us. Kayla sat on the bed with her bare scalp reflecting a slice of morning. Reese climbed up beside her and wrapped herself around her like a ribbon. My husband sat heavy next to them and put his head in his hands. He looked up at me and said something that made me want to take twelve years of motherhood and wear them like armor.

“I’m sorry,” he said. “Two weeks ago I saw bruises on her wrist at dinner.”

The anger in the room pivoted, turned its lighthouse on me and my husband alike. He told us how he’d gone to the school the next day, waited in the parking lot after baseball practice, grabbed Steven by the shirt and shoved him against his car. “If you ever touch my daughter again, I’ll kill you,” he’d said into the boy’s face, and Steven had smiled and pressed Record on his own phone.

“Why didn’t you tell me?” I asked, voice thin because there was barely enough air for my family.

“Because he played it for me,” my husband said. “Because he said if I interfered, he’d go to the police and press charges for assault for me putting my hands on him. Because his dad is who he is.”

The shame in his voice made me want to bite something. “We’re calling the police,” I said. “We’re calling now.”

He nodded. Kayla cried, saying it was her fault, that she didn’t want Dad arrested because she picked a boy who would do this. “It’s not your fault,” Reese said fiercely, our eight-year-old defense attorney. “Bad people do bad things. That’s on them. Not the people they hurt.”

I called the non-emergency line because I’m the kind of person who still worries about tying up 911. Maybe it’s the Midwest still in my tongue. The dispatcher answered and I heard my voice say words I hadn’t thought I’d ever say in a kitchen with cereal bowls in the sink and a school portrait magnet on the fridge. “We need to report domestic violence and a planned assault,” I said, mouth full of metal. “We have… evidence.”

She said she was sending officers and asked if we were safe. I told her yes, now, for this minute. She told us to lock the doors and not to open them for anybody but police.

While we waited, I asked Kayla for her phone. It came out like a confession, trembling. The messages were there like a crime scene you walk into too late: what to wear, which friends she could call, apologies—I’m sorry you made me mad—threats—I’ll make sure everybody knows you’re a liar—one that said outright what my stomach already knew: I own you. There were months of them. I screenshotted until my fingers cramped and sent them to my own phone, my inbox filling with the evidence of how you boil a frog.

“Why didn’t you tell us?” I asked, and I didn’t mean it as a weapon. “How did we miss it?”

Kayla stared at her knees. Reese raised her hand like we were in church. “I tried,” she said, not unkind. “You said I was jealous. So I started taking pictures. And then I remembered the recorder Daddy uses to practice speeches and I put it in my pocket.” She looked at me, eyes enormous. “You always say grown-ups want proof.”

The doorbell rang. Two officers came up the stairs quiet as grown men can. They stood in my bedroom like it was a new place to be brave and listened to Steven’s voice on the recording and Kayla’s small breaths while she showed them the marks. One officer called a detective. “Given the planned nature,” he said softly. “And a minor.” He used the words victim and survivor in the right ways in the same sentence, and I could have kissed his badge.

Detective Nora Gomez arrived in jeans and a blazer like ambition on a Saturday. She introduced herself in a voice that didn’t put pressure on us to be anything but what we were. She asked to speak to each of us separately. When it was my turn, I handed over everything—photos, files, screenshots, the pink recorder. She wrote down Julian Franks’ name and didn’t roll her eyes when I said big firm. She said we’d done the right things in the right order and for a moment I felt an unfamiliar pride for having met a crisis like a grown-up.

She talked to my husband and he told her about grabbing Steven by the shirt. Detective Gomez nodded, let him finish, and said, “I understand a father’s instinct. I’ll note the context in my report.” When she sat with Reese, our daughter straightened her skinny back and told the detective exactly why she had done what she had done. Detective Gomez asked if shaving Kayla’s head had been the best plan and Reese shook her head, no, but then added with a little shrug, “It was the only one I could do all by myself.”

“Sometimes the only plan you can do is better than the perfect plan you can’t,” the detective said, and I put the sentence in my heart like a postcard from a country I wanted to live in.

She told us to take Kayla to the emergency room to document the injuries. The doctor there was gentle as a handkerchief. She measured every bruise with a ruler and spoke to Kayla like she was a person in a terrible story and not the story itself. Seventeen bruises in various stages of healing. The nurse photographed each one. They gave us copies with times and dates and we put them in a folder with a red tab as if organization could be a raft.

A social worker came in with a folder full of pamphlets that looked like anything but help until she started speaking. “We’re required to report this,” she said. “You’ve already done it. I can give you resources. I can give you names and phone numbers that answer on weekends. I can give you a plan for if he tries to contact her again.” She had the kind of voice that makes kids trust her and men careful and women feel not stupid for crying.

My husband’s phone rang while we were initialing discharge papers. He put it on speaker without warning, and Julian Franks’ voice filled the small hospital room like a cheap suit. “You will pay for this,” he barked. “False accusations. Defamation. Assaulting a minor— I will own you before Sunday.”

The social worker didn’t say a word. She pressed her own record button on her phone and raised her eyebrows at me like you seeing this? My husband said we were at the hospital documenting his client’s abuse and hung up. The social worker said she would add the recording to the file as evidence of witness intimidation. She handed me a business card with her cell number in pen.

We drove home in a line of quiet—my husband checking mirrors like he believed in followers, Reese with her hand locked in Kayla’s hand like a puzzle piece, me watching the house get closer like a tide coming in. We turned onto our street and saw a black car idling at the curb by our mailbox. Steven’s car. Engine still on, like an animal ready.

“Drive past,” I said, and dialed Detective Gomez from the card in my hand. “Don’t stop. We’ll go to the grocery store. We’ll wait where there are cameras and cart corrals and men in orange aprons.”

She told us officers were en route. Ten minutes later, she called back. We could return. Two patrol cars had bracketed Steven’s car and there was a young officer leaning by the driver’s window with a pen and the patience of a saint.

“He says he was just driving by,” the officer told us when we parked and piled out. “We’ve warned him he’s not to come near you or your property. We’ve taken photos of his car in front of your house. It will go in the file as a violation.”

Steven peeled away when they released him. The officers stood and waited while we went inside. The house felt different with them there, like good ghosts.

That evening, the phone rang with a voice that introduced herself as Mattie Coleman from the school counseling office. “I heard what happened,” she said, gentle without pity. “I can set up a plan so Kayla doesn’t have to walk the same halls. We can change her locker. We can give her a safe room—two, three. We’ll get her assignments sent home. You don’t have to do this part alone.”

An hour later, Detective Gomez called back to say she’d found Jake and the boy had crumbled under the simple weight of decency. He’d told them Steven asked him to make sure Kayla’s drinks were “extra strong” and had mentioned getting “something special” from his brother. The detective said she was working with a judge to secure warrants for Steven’s car and phone. “Tyson’s had three arrests for pills,” she added, words matter-of-fact instead of malicious. “We’re moving.”

The next morning, Child Protective Services called to schedule a home visit. “Standard,” the woman said. “Not punitive.” Standard and not punitive is what I chant now when I’m about to break. She arrived with a clipboard and a face you want to pass. She talked to each of us separately, nodded when Reese showed her the little pink recorder and the photo she took before clippers, smiled when she finished and said, “You’re doing so much right.” She left us pamphlets on trauma in kids and permission to believe what the detective had told us: we had done the right things in the right order.

That afternoon, a woman named Tabitha Wise called. Victim advocate, she said—emphasis on advocate. “You can file for an emergency protective order,” she told me. “I can help with the paperwork. I like paperwork.” She laughed and it sounded like a porch in June. She came to our kitchen with a laptop and a tote bag that produced snacks like a carnival trick and sat with us for two hours while we sorted photos, recordings, medical documentation, the pink recorder—a life becoming a case. “This is strong,” she said. “A judge will likely grant it right away.”

A certified letter arrived the next day from Julian’s office, three pages heavy with grammar and threat. I took pictures of each page and sent them to Detective Gomez, who called within minutes. “Perfect,” she said, the way chefs say it when a sauce breaks and you’ve somehow saved it. “Keep everything. We’re building a wall.”

On Monday morning, I drove Kayla to school. She wore a beanie to cover what we hadn’t had time to finish, her hand squeezing mine so tight I felt the bones move. The whispers started as soon as we walked through the doors—boys smirking, girls’ mouths in mean little flowers, a steady hum that wants to grow into a hymn. A boy stepped out of a doorway and said, “I believe you.” He said it plain. He didn’t ask for proof. It hit me like church.

The principal waited in the office with Mattie from counseling, who had produced a new schedule with routes that kept Kayla away from Steven’s old patterns—different hallways, a new locker, a “safe room” with a couch and tissues and no questions asked. As we walked the new path, my phone buzzed. Detective Gomez.

“I have what I need,” she said. “We searched the car. there was a bag under the driver’s seat. We’re rushing a test, but I know what pills look like. We will not let this get as far as he wanted it to.”

Within two hours, I watched on the local station’s website as two officers walked Steven out of his house. He looked small in daylight. He was charged with possession of controlled substances and conspiracy to commit sexual assault. His father posted bail before dinner, but there was a case number now and a thing the adults could do.

Three days later, we sat in a courtroom for an emergency protective order hearing. Tabitha sat next to us with her tote bag like a guard dog in human form. The judge had the kind of face that could spare you or spare you nothing and still be right. I stood and told him everything. He listened to the recording of Steven planning to drug my daughter and his face got harder in layers. He asked my husband about grabbing a boy by the shirt. My husband told the truth. The judge nodded and said he understood a father, but this was about men who use girls. He granted the restraining order, five hundred feet, now and always, and set a hearing for a longer one later.

At the school, they convened their own hearing. They suspended Steven immediately and banned him from graduation. His father stood and threatened the biographies of the school board members and their grandchildren’s grandchildren and the building itself. No one flinched.

That night, with the girls tucked into the same bed like when they were small, I stood in the doorway and watched Reese rub Kayla’s back the way Kayla used to do for her during thunderstorms. My husband checked every lock in the house twice and then a third time, then came and stood beside me.

“I keep thinking of her with the clippers,” he said.

“Me too,” I said. There was love in the picture and something else, something fierce and ancient and bigger than this one story. Call it family. Call it God. Call it stubborn survival in a bathroom with a stepstool.

Tomorrow there would be detectives and affidavits and a Constitution around which you must learn to wrap your fear. Tonight there was my daughter’s bare scalp shining like a moon and my younger daughter’s hand moving slow, slow, back-and-forth, back-and-forth in the dark.

Part II

Child Protective Services arrived at nine on the dot—clipboard, flats, a mouth set for bad news that softened a fraction when she saw the cereal bowls in the sink and the seven thousand crayon drawings on the fridge. Her name was Ms. Dalton, and she smelled like hand sanitizer and peppermint. She took the girls one at a time, Reese first. Our little saboteur sat on the edge of her bed, heels knocking the frame, and told the story straight: the hair, the hidden recorder, the photos she’d been taking with my phone when she “borrowed” it to play games.

“There’s something funny about a kid who collects evidence,” I said later, when Ms. Dalton and I sat at the kitchen table and she wrote no safety concerns on a line my eye kept finding. “Why didn’t she just tell us?”

“She did,” Ms. Dalton said, not unkindly. “You didn’t speak the same language yet. Kids do what they can with the tools in their belt. Some become translators. Some become archivists. Both save lives.”

She left us a stack of pamphlets with anxious fonts about trauma in children and an assurance that someone would call within two days to offer therapy. “You’re doing a lot right,” she said at the door. “Let me know if you need anything that isn’t in those brochures.”

By afternoon, the house had been visited by more acronyms than I knew how to thank. The doorbell brought a woman named Tabitha Wise—victim advocate—with a canvas tote that clicked with highlighters and tabs. “Emergency protective order,” she said, pulling up a chair. “We’ll file today. Judges like clean timelines, clear evidence, and parents who look like you do when you look at your kids.”

“How do we look?” my husband asked, trying for light and landing in weary.

“Like people who want to protect more than they want to punish,” she said. “That helps.”

We spent two hours at the table making a wall out of paper: hospital photographs with rulers in the frame, the text messages where I own you sat on the screen like a bruise, Reese’s pink recorder now saved as a WAV file and emailed to three different inboxes, the detective’s card, the social worker’s note from the hospital, the report number the patrol officer had written in neat, proud digits.

Then a certified letter slid through the slot like insult in stationery: three pages from the Law Offices of Julian Franks, all defamation and assault and withdrawal of baseless claims and we will sue you into a kind of homelessness you cannot imagine. My husband’s face flushed the color of bad wine.

“Forward it to the detective,” Tabitha said, unruffled. “Threats in suits are still threats. Keep the envelope. Judges love envelopes.”

The school called to say Kayla could finish the week at home. On Monday, they’d make a plan. “Is she comfortable riding the bus?” the woman asked.

“Not today,” I said. “Maybe not for a while.” She didn’t argue. “We’ll walk her in,” she said. “We’ll meet you at the door. We’ll change the route every time until the halls belong to her again.”

At six, my phone rang with a number I didn’t recognize and a voice I now would: “It’s Gomez,” the detective said. “We got the warrants. We found pills under the driver’s seat. We won’t know for sure until the lab sings, but I’ve been doing this long enough to call what I see.”

“Even with Tyson’s history?” I asked, my brain already trying to work a defense that wasn’t mine to consider. It’s a weird skill you gain when you’ve spent years making peace between the wildly different stories people tell you about themselves: your mind drafts opposing counsel before you want it to.

“History helps,” she said. “But what helps more is the bag under the driver’s seat and the boy who asked his friend to make her drinks extra-strong and the recording of a plan he was proud enough to brag about.* These things were not what you’d call subtle. I don’t win cases on luck,” she added, and I could hear the edge under her patience. “You only see us at the moment we knock on a door. You don’t see the nights we wait in parking lots or the awkward hours we spend convincing boys named Jake to be better men.”

She called again two hours later. “He’s in cuffs,” she said simply. “Possession and conspiracy. Dad posted bail. You’ll sleep tonight knowing there’s a case number.”

Sleep was a generous word. But I lay down on the couch anyway while the girls fell asleep in a braid of limbs in Kayla’s bed and my husband checked the locks for the third time. Reese’s recorder sat on the coffee table between us like a small pink heart that had learned to beat fists.

Monday morning, the school did what it could—the practical kind of protection that says not we care but we will make it harder for him. The principal met us in the lobby with a woman from counseling, Mattie, who looked like she’d been running an emergency inside the building since dawn. “New routes, new locker,” she said, sliding a schedule across the desk. “Floors with more eyes.” She pointed out a room that wasn’t a room so much as a promise: couch, tissues, a lamp that threw warm light instead of interrogation. “If she needs to sit down and cry, she can do it here and no one will ask her to explain her grief on a bell.”

We walked the routes quietly, Kayla in a beanie and long sleeves, my hand tense in hers. In the hallways, girls watched us with mouths in mean little shapes and boys looked away the way they do when decency costs them status. One boy stepped forward and said “I believe you” and I wanted to lay down in gratitude. You spend months braced for a community to turn on you and then you realize communities are a quilt built out of moments like that and Matties with clipboards and principals who say no to men in suits without asking to phone a friend.

As we walked past the front office, my phone buzzed. Detective Gomez again. “I’m greedy,” she said. “We want the phone too. His, hers, everyone’s. We’ll likely get it. The lab is moving.”

Kayla squeezed my hand. “Tell her thank you,” she said, and I did. It wasn’t the detective’s job to love my kid, but she had decided to do it anyway with nouns and dates and signatures.

She called again two hours later. “Charged,” she said. “Possession. Conspiracy. Dad scraped bail together before supper, but there’s ink on paper that says this happened. We’ll see them in court.”

The hearing for the emergency protective order happened in a room made to feel like justice even when justice takes a while to arrive. The judge looked like he’d survived three divorces and learned things from each. I stood and said the sentences I’d practiced into the mirror with Tabitha nodding at the right parts. The judge listened to Reese’s recording without interrupting; his jaw clenched exactly once. When my husband confessed to grabbing a boy by the shirt in a parking lot, the judge said, “Not ideal,” and then, “context matters,” and then signed the order with a flourish like it held back something with teeth.

Back at home the work of healing arrived like homework: Kayla’s therapist appointment card on the cork board, a refrigerator schedule with Family Check-In blocked out at six p.m., a bag on the table from the domestic violence shelter with care kits Reese would help assemble for kids who had to leave home in a hurry—small blankets, toothbrushes with cartoon characters, cards that said You are brave; it’s not your fault in Reese’s careful print. The social worker had told us the hospital reported as a matter of law. Our call had beat them to it by half an hour—one brisk use of a phone that will be my favorite for the rest of my life.

We went to the emergency room because Gomez said so. We opened our front door when the CPS knock came, because Ms. Dalton reminded us what “standard” looks like when it’s on your side. We sat at our kitchen table and let a stranger help us proofread our pain into boxes a judge would recognize.

“You keep saying it felt too easy,” our therapist would say later, her pen cap chewing through the worst of us. “As if outcomes negate efforts. You only saw the parts of the system that landed. You missed the ice under the tip of her knock. It’s okay to be grateful for what worked without apologizing for the parts that didn’t have to show you their sweat.”

Kayla went back to school with a beanie and a new route and a pass stamped SAFE by a secretary who didn’t make her whisper. I bought her three hats like a cliché and she told me shut up with her eyes and I laughed and shut up. Reese took to sleeping in her sister’s bed and tracing the peach fuzz at the back of Kayla’s head like a rosary. We learned to hold silence without trying to fix it and we taped Detective Gomez’s card next to the emergency numbers on the fridge.

Three days later, Steven walked out of his front door in cuffs. The neighbors watched from their driveways with the kind of nosiness that finally understands what it’s for. Julian posted bail with a flurry of signatures and a breath-stealing check. When he called to rage, the social worker hit record and took notes like a stenographer for a future judge.

“Why does it feel like things keep arriving exactly when we need them?” I asked our therapist in the first family session. She smiled.

“It’s not magic,” she said. “It’s logistics. And sometimes it’s practice. You’ve been practicing telling the truth. Systems like it when you speak their language.”

Kayla started seeing Ms. Rao, who specialized in teenagers whose bones had learned to expect impact. The first week, Kayla refused to talk about Steven at all. She cried and stared at the carpet and said she hated the smell of the office and the way Ms. Rao’s pen sounded on paper. The second week she pointed at the diagram on the wall that said trauma responses and asked why the word freeze had to be there at all. The third week she said Steven’s name like it was a foreign word that had finally decided to translate itself. “He hit me in the stomach,” she said, voice flat, “so no one would see,” and Ms. Rao nodded in a way that said I know and I hate that too.

The therapist gently handed the rest of us our work. “You don’t get to carry only your part of this,” she said. “You all come to dinner with different ghosts. Let’s give them chairs and see which ones still need feeding.” She assigned us journals and told us to write one paragraph a day: a fact, a feeling, a wish—no edits, no apologies. We had to do one “check-in” at dinner: what’s one thing I needed today, what’s one thing I got. Reese drew pictures with colors that were more honest than any of our sentences.

We filed papers with Tabitha and she filed them with the court and the court stamped the order and slid it back with an ink that actually feels like it holds you. The school slid a fresh badge into a sleeve around Kayla’s neck and told her she could duck into the attendance office anytime without asking. Mattie walked her past every adult in her new route with one sentence that turned strangers into sentries: “This is Kayla.” She didn’t say what happened. She didn’t need to. People know the face of a kid who almost got taken and didn’t.

That night, when the house had finally settled and the dishwasher sang its low hum, Reese—who had been asking for days if cutting hair gets you jail—came to the couch and climbed into my lap like she was three again. “Do grown-ups always do the right thing once they see proof?” she asked.

“No,” I said. “But more of them do when a kid as brave as you speaks their language.”

She leaned into me with a satisfied snotty sniff. “That’s why I recorded,” she said. “Grown-ups like proof more than feelings.”

“Some of us do,” I said, and kissed the back of her head.

“Next time,” she said, without looking up, “I’ll tell you louder.”

“Next time,” I said, “I’ll listen sooner.”

At the courthouse for the protective order, I watched the judge’s face harden by increments as Reese’s recording filled the room and Steven’s lawyer tried to call it teen drama. The judge’s pen tapped. “No,” he said. “This pattern is a form of control older than any of us. It uses phones as leashes and girls’ fear as a leash. It stops here for now.” He signed the papers and the bailiff handed us copies with the case number circled like a halo.

The school board held a hearing of their own in a room that did not know what to do with rage in a pressed suit. Steven’s father stood up and promised ruination and the principal, who had been teaching other people’s children for thirty years, put her hand on the table and said, “No.” They banned him from the campus, from ceremonies, from the graduation he’d postured toward like a toddler demanding cake. It was not justice. It was something that felt like its cousin.

On Tuesday, a counselor at the hospital invited Kayla to a support group for teenagers who had been banged up by people who said they loved them. The first meeting, she didn’t speak. She listened to a boy describe a girlfriend who locked him in a closet when he wouldn’t answer questions fast enough, and a girl who talked about a boy who “liked to squeeze” her arms when she wore tank tops, and another who said, “I didn’t think I could leave because I introduced him to my parents.” The second meeting, Kayla said “me too” once and went home and slept nine hours. The third meeting, she brought a cookie cake and wrote Firsts on it in icing.

Steven’s friends began to deliver his messages because the brave heart of a restraining order is that abusive boys rarely write their own notes. Abusers outsource. A basketball teammate slipped a paper into Kayla’s locker that said He still cares, and two girls with matching ponytails approached her and said, “He’s really sorry,” like it were their apology to give. We photographed each attempt and forwarded it to Detective Gomez and she forwarded them to the prosecutor and called Steven’s lawyer and said, “Attempted contact is contact.”

Sometimes I would catch myself at the sink, water running over a dish, wondering in a horrible corner of my brain if this was too neat. A detective who always called back within the hour. A school counselor who knew which hallway to change. A social worker with a recording app and a sense of timing. Pills under a seat. Two other girls coming forward right as we needed them.

At the next session, I told Ms. Rao about my conspiracy theory brain. She smiled. “It feels like magic when a system works because we only hear when it fails. Allow yourself grace,” she said, “for living in a world where it usually doesn’t. Let the days it does be the days you sleep.”

We slept some. We learned some. We waited for court.

Part III

Monday came like a dare. Kayla tugged a knit beanie low over the soft stubble of her scalp and stared at the front door as if it might have an opinion. “I’ll walk you in,” I said. She took my hand so hard my bones announced themselves.

The parking lot already hummed when we pulled up—kids pressed to windows, screens lifted like binoculars. Inside, the whispering started in little gusts and grew, boys huddled with their backs to lockers, girls with mouths making mean flowers. A boy stepped out of a doorway and said, simply, “I believe you.” Kayla didn’t look up, but her fingers eased a millimeter around mine.

The principal waited in the office with the counselor I’d spoken to on the phone—Mattie Coleman, a woman with the practiced calm of people who spend their days catching falling things. She spread a new schedule across her desk, her pen clicking with purpose. “Different hallways,” she said, tapping routes. “New locker. Extra eyes. This is a safe room.” She pointed at a small space with a couch and a lamp that threw warm light instead of interrogation. “If you need to cry, you can do it here. No permission slips for tears.”

My phone buzzed as we walked the new route. Detective Gomez again, voice like a hand at the small of a back. “We executed the warrant,” she said. “Bag under the driver’s seat. Pills. We’ll rush the test, but I don’t miss what I’ve been looking at for fifteen years.”

Even with my gratitude, a snotty corner of my brain tried to work a defense that wasn’t mine. “His brother Tyson…” I started.

“Helps the story,” she said. “The bag under the seat helps more. The boy asking his friend to make her drinks extra-strong helps most. The recording helps best. This isn’t luck,” she added, reading my mind. “You see me when the door knocks. You don’t see me waiting in parking lots or begging boys named Jake to be better men.”

Two hours later she called again. “He’s in cuffs,” she said. “Possession. Conspiracy. Dad posted bail by supper. But we’ve got a case number and ink on paper. That’s something to sleep on.”

Sleep was a kind word. But I closed my eyes that night and let the idea of ink on paper be a pillow.

The emergency protective order hearing met us in a courtroom that tried its best to look like justice even when justice drags its feet. Tabitha took the chair beside me, her tote bag full of highlighters and faith. The judge looked like he’d run out of patience years ago and learned to ration what was left on people who deserved it.

I stood and told our story, the sentences catching on the edges of words I didn’t want to say out loud—bruise, plan, pills. The judge listened to Reese’s recording without interrupting. His jaw got harder with each sentence until it looked like it belonged to a statue. He asked my husband about the parking-lot incident, and my husband told the truth straight. “Not ideal,” the judge said, “but context matters.” Then he signed the order—five hundred feet, now and later—and the bailiff handed us copies with the case number circled like a halo.

The school board held its own hearing in a room that felt like a town hall on a hot night, only this town understood its job. The principal laid out the evidence. They suspended Steven pending the criminal case and banned him from campus and all ceremonies, including graduation. Julian stood and promised to peel their lives apart in court, and the superintendent—twenty-six years in education, hair a permanent compromise—said, “No.” Sometimes the right word is one syllable.

Kayla started therapy with Ms. Rao, who wore boots and kindness and spoke to teenagers like they were people who pay their own taxes. The first week, Kayla refused to say Steven’s name. She traced the pattern on the office rug with her sneaker and cried. The second week, she pointed at a poster that listed fight, flight, freeze, and asked why the world needs a word for the thing your body does when it refuses to move even though your heart is beating like a trapped bird. The third week, she said, “He hit me in the stomach,” voice flat, “so no one would see.” Ms. Rao nodded the kind of nod that says I know and I hate that and here is how we live anyway all at once.

We started family therapy every Thursday after school. The therapist—Dr. Loomis, a woman with gray streaks that looked intentional—sat us in a circle and handed out journals. “Three lines a day,” she said. “A fact, a feeling, a wish. No edits. No qualifiers. No apologizing for adjectives.” She taught us to do “check-ins” at dinner: What did I need today? What did I get? Reese drew pictures instead—storm clouds on days she was scared, suns on days she laughed, spirals on days when both lived in the same sky. We learned new grammar for sorrows we had been trying to sentence correctly for months.

Reese went twice a week to a child therapist who had a dollhouse and no patience for euphemism. “Protecting your sister was brave,” the therapist told her. “Cutting hair wasn’t the right choice. Both things can be true.” Later, when Reese’s guilt about the buzzcut curled around her like a second skin, the therapist suggested restorative justice. Reese wrote Kayla a three-page letter in pencil—no erasing—apologizing for taking the scissors to something that wasn’t hers, explaining she was scared all the time and the only way she could think to keep Kayla safe that night was to take the party away. She started volunteering at the domestic violence shelter, sorting donations with a focus that made the coordinator cry. She drew hearts on care packages and tucked in notes that said, You are brave. You deserve safe. The coordinator told me the women saved Reese’s drawings in their wallets like lucky pennies.

The district attorney called three weeks after the arrest. “We’re moving forward,” she said. Charges for assault, conspiracy to commit sexual assault, possession of controlled substances with intent. She mentioned Kayla might need to testify. I felt my back go straight as if bracing for a punch. Kayla listened from the doorway, quiet as a deer. She sat down next to me and said, “I’ll do it. Other girls should know you can speak.”

Two other girls from school came forward after hearing about Kayla. Neither wanted to press charges (I did not blame them), but both described the pattern in familiar strokes—grabbing too hard, pushing into lockers, gifts afterward big enough to buy silence. Their statements, Detective Gomez said, might help the prosecutor show a jury that this wasn’t clumsy teenage love; it was a skill.

Steven violated the protective order by proxy. Notes appeared in Kayla’s locker—He misses you. He’ll change. Boys Kayla didn’t know tried to walk her to class, saying “He says sorry” like it were theirs to give. We photographed each violation and sent it to Gomez, who added them to the stack and called Steven’s lawyer every time. Attempted contact is contact. That sentence now lives in my head next to ink on paper and no as the three best words I learned this year.

Kayla started going to a support group at the hospital on Tuesday afternoons. The first week she sat and listened to seven kids name their hurt, and the sound felt like someone opening a window on a hot day. The second week, she said “me too” once and went home and slept like the house forgave her. The third week, she brought cookie cake and iced Firsts across it with shaky hands.

There was a boy in the group named Eric. His ex-girlfriend had broken his arm. He had a laugh that made other kids look up from their shoes. He asked permission before he hugged anyone. He palmed a baseball in his hand like other men hold cigarettes. After a month of sitting in the same circle, he walked Kayla to the parking lot and asked if he could call her sometime. “Just to talk,” he added quickly. “My mom can pick us up if you ever want to leave early.” Kayla smiled for real. Two months later, when they finally kissed, he asked, “Is this okay?” as if the word kiss itself had a seat in a council of elders.

Letters from Julian kept arriving, certified and smug. Our lawyer—hired for the purpose of ending these letters—sent one back that said, boiled down, stop or we will make you stop. The legal term was “harassment,” but in my bones it translated to you are not the only one who can speak in rooms with wood paneling. After that, the letters slowed from a flood to a trickle to silence.

The trial began six months after Reese’s clippers sang. By then, Kayla had buzzed her hair again on purpose, deciding she liked the look of herself without anything to hide behind. She wore the dress she’d planned for prom—a bright blue thing that made her shoulders look like she’d decided to carry less than she used to. We sat on a hard bench and watched Steven walk in wearing a suit that didn’t quite fit. His mother cried. Julian looked like a man furious that his name wasn’t a spell.

Steven’s lawyer called it “a teenage romance gone wrong.” The prosecutor called it “a pattern.” She painted our case with nouns that felt heavy in my mouth—possession. conspiracy. assault. The lab technicians testified about pills that turned out to be exactly what Detective Gomez thought they’d be. The judge allowed Reese’s recording because our house is not a place where the person planning a crime gets to claim privacy over his own bragging. In the audio, Steven laughed about “locking her down” and making sure Kayla couldn’t say no. You could feel the jurors’ faces change: a woman put her hand to her mouth and didn’t remove it until the clip ended; a man shook his head in the slow way men do when they realize they could have missed this if the world had tipped a degree.

Kayla testified on a Wednesday when the sun decided it didn’t care about the weather inside. She walked to the witness stand in that blue dress with her head up, hands shaking so hard the bailiff adjusted the mic low so she wouldn’t have to reach. She told the truth: how he’d grab her arms hard enough to leave marks, how he’d push her into walls, how he hit her in the stomach where no one would see because he didn’t want to have to think up lies. How he’d cry after and buy flowers or bracelets and say he loved her so much he couldn’t help himself. How, after a while, she stopped recognizing the part of herself that wanted anything other than peace.

The jury leaned in like they were listening to a lullaby they hadn’t heard since childhood. The prosecutor kept her questions clean, no adjectives. Steven’s lawyer tried to get Kayla to admit she’d stayed because she’d liked the attention. Kayla said, “I stayed because he said he would ruin me if I left.” The judge watched the lawyer watch the jury and decided not to save him from himself.

Reese wore her unicorn dress to court and held my hand until the bailiff said she had to hold up her own right hand and promise to tell the truth. Her feet didn’t touch the floor when she sat in the big chair. The judge’s mouth did a tiny thing it didn’t do for anyone else—something like tenderness. When the prosecutor pressed Play on a copy of her little pink recorder, the room went so quiet my ears rang. Steven’s voice filled the air in that expensive room and told on him better than any of us could have. Reese explained afterward, in her serious voice, why she recorded him. “Grown-ups don’t always believe girls,” she said. “But they believe proof.” The court reporter absently wiped her eye. The judge did not. He just nodded like a man who understood that his gavel was late to most rooms.

Gomez testified like a metronome. She had dates and times and names and the kind of patience that, when it ends, ends with an economy of mercy. The lab report did what lab reports do—made it fact for people who cannot hear it any other way. Two other girls testified that Steven had grabbed and pushed and apologized and bought and promised. None of them looked at him.

We waited four hours in a hallway with bad coffee and a vending machine sandwich that could have doubled as a doorstop. My husband kept standing up to check a door that didn’t need checking. Reese fell asleep with her head in my lap. Kayla sat with her hands palms-up on her knees like she’d just received something and was waiting to learn what it was.

“Verdict,” the clerk called, and the hallway turned into a wave. We filed back in and the foreman stood. “Guilty,” he said. On possession. On conspiracy. On assault. Steven’s mother started to cry for real, no mascara left. Julian’s jaw clenched so hard you could see the calculation in it: appeal, appeal, appeal.

Three weeks later at sentencing, the judge gave Steven two years in juvenile detention, three years probation, mandatory counseling, and a restraining order with the kind of permanence that lives on in databases long after suits go out of style. In the parking lot, Julian cornered us. He told us we’d ruined his son’s future over “teenage drama.” My husband stepped forward—not in aggression, just in accuracy—and said, “Your son is a predator who finally got caught. Maybe if you had been a better father—” He didn’t need to finish. There were cops everywhere. Julian got in his Mercedes and left tire on asphalt like a child.

Things changed in quiet ways after that. Doors stopped being something to jump at when they closed. Kayla slept. She started seeing herself as other than broken. She talked to Mattie about using assembly time for something other than pep rallies. The first day she stood on a stage and told three hundred juniors that love does not make you afraid, she cried halfway through and people clapped anyway. Three girls came up after and said they needed help. A boy stood at the edge and waited until the crowd thinned and told his counselor later about a girlfriend who had been hurting him. The school board brought in experts to train teachers on teen dating violence. They added a unit in health class about healthy relationships that didn’t read like a pamphlet printed in 1993.

Kayla kept her hair short on purpose. She said the stubble reminded her that love sometimes looks like an eight-year-old with clippers and faith. Reese poured her fierce into better places. She organized a donation drive at school for the shelter. She made signs with simple messages and convinced the principal to let her give age-appropriate talks in fifth-grade classrooms so that little girls would know that “I don’t like that” is a sentence they can say and be taken seriously.

Detective Gomez called every few weeks, start with How are the girls? before getting to here’s what the docket says. She told us Steven had been in three fights his first month inside. “He keeps picking on kids smaller than him,” she said, not with satisfaction, just with an observant sorrow. “Sometimes patterns are the only witness that matters.”

Kayla graduated under a sky that remembered how to be blue. Her hair was a pixie cut now, clips holding back pieces she called cowlicks, her smile easier than math. She walked across the stage to the kind of yelling that makes strangers smile. The program named her salutatorian, and in her speech she thanked Reese for saving her life. Reese cried and then laughed, weird little hiccups like joy tripping over itself.

Crowds are noisy. Grief is quiet. Relief is somewhere in between. When Kayla hugged me after, caps flying and programs crumpling underfoot, she whispered, “I thought I’d be dead,” and I said, “Me too,” and it felt like a prayer answered late but answered.

She chose a college three hours away—far enough to become someone else, close enough to come home for soup. We went dorm shopping. She picked bright colors. She put a photo of our family on her desk, the one from after the verdict where both girls are laughing at something on Reese’s phone and my husband looks like a man who has learned how to be present even when his fear wants to run.

The night before we drove her to campus, she crawled into Reese’s bed like they used to do when they were little. In the morning, I found them tangled, Reese’s arm slung over Kayla like a seatbelt. In the car, they whispered something that made both of them cry and laugh at the same time. I didn’t ask what. Not every sacred thing belongs to the person who pays the insurance.

When we pulled away from the curb in front of her dorm and Kayla waved and the RA yelled about room keys, I thought of the bathroom floor covered in hair, of a pink recorder the size of a playing card, of a detective who returned calls, of a social worker who hit record at the right moment, of a judge who said “No” like a benediction, of a school counselor with a safe room and good light, of my husband’s hand shaking on a steering wheel and my own shaking on a phone.

You never think the sound of clippers will be the thing that saves your child. But I do now. I think it every time I hear a buzz behind a door and remember: sometimes the loud thing is the right thing. Sometimes the plan you can do is the plan that keeps a girl alive.

Part IV

Three weeks after we left Kayla in her dorm room under fairy lights that made everything look like good timing, the house learned the shape of missing. I found her mug in the cabinet—blue, chipped, the one that never kept tea warm—and put it on the shelf facing out like a portrait. Reese started setting an extra fork at dinner and then laughing at herself and then leaving it because ritual is a kind of seatbelt.

College has its own kind of weather. Kayla called the first weekend and told us about a roommate who labeled her butter and a girl in her hall who wore flip-flops in November. She called the second week and didn’t say anything for a minute and then said she was fine and then cried anyway, and I sat on the back steps and let her breathe into my ear like a tide. She called the third week from the campus counseling center’s waiting room and told me she’d made an appointment—no prompting, no push—because the smell of a certain cologne in a lecture hall had transported her to a hallway she wasn’t walking anymore. Scents are time machines. We put that in the journal next to ink on paper and attempted contact is contact and no as another useful sentence for survival: It makes sense that my nose remembers what my brain forgot to say out loud.

The school held a Take Back the Night march in October. Kayla sent a photo of candles cupped in hands and a video of a girl telling a room that shame is a gag you can chew through. In the video’s last seconds, there was Kayla at a microphone, her hair grown out to a purposeful pixie, a scrap of paper shaking in her hand.

“I used to think bravery looked like fighting in parking lots or saying clever things on the internet,” she said. “It turns out bravery can look like walking into an office and telling the truth to a stranger with a clipboard. It can look like being a good witness to your own life.”

Campus police stayed a block away and did no speeches and carried no bullhorns. Sometimes institutions learn; sometimes they simply keep their distance. Either way, the candles didn’t go out. Kayla went back to her dorm and slept eight hours.

Reese, meanwhile, turned nine with the righteousness of a small activist and the appetite of a Labrador. She finished the restorative justice project with a steadiness that surprised even the therapist. The program asked for a repair that wasn’t punishment—a contribution that acknowledged harm and honored the why. Reese wrote Kayla another letter, this one about trust, the hand-scrawled sentences fatter now: I am going to be loud when I see things that look wrong. I will use words first. If words don’t work, I will get help from tall people. She ended with I love you more than your hair, which made us all laugh until we cried.

She kept going to the shelter on Saturdays, more sure-footed now in the room with donation bins and women who both needed and hated to need. Reese learned to fold baby clothes with one snap undone because trauma hands are clumsy. She put stickers on the kids’ bags—dinosaurs for the boys, unicorns for the girls, stars for whoever didn’t want either—and wrote notes that didn’t promise anything they couldn’t give: Today you get to be safe. The coordinator pinned Reese’s drawings on the staff fridge. “On the worst days,” she told me, one hand on her chest, “that fridge keeps us upright.”

Our family learned the choreography of “after.” Thursday therapy. Sunday dinners. Tuesday support group ride-shares. Family check-in at six p.m.—sometimes on the floor with pizza, sometimes at the table with vegetables, always a place to bring a hard thing and set it down without someone adding a bow or a moral. We asked and answered the questions Dr. Loomis had given us. What did I need? What did I get? The girls learned to say “I felt scared when…” without someone correcting their grammar or their emotion. My husband learned to say “I felt ashamed when…” without using his fists on himself. I learned to say “I missed that” without adding “but.”

CPS closed its file quietly and sent a letter with a stamp that had a squirrel playing a trumpet. No further action, it said. Sometimes bureaucracy surprises you by letting you go.

In November, Julian filed a civil suit so dramatic I could hear the flourish from the mailbox. Our lawyer filed a response so boring it could lull a wolf. The judge—same one who had banged the gavel on the restraining order—dismissed the suit in a hearing that lasted nine minutes. “This is harassment disguised as litigation,” he said. “Do not bring this into my courtroom again.”

Julian appealed. The appellate court affirmed without comment. I printed the decision and taped it inside a cabinet next to the ultrasound photos and the list of “after” groceries we now keep on rotation: tea, tissues, freezer dumplings, hope.

In December, Kayla came home with a bag of laundry and a stack of handouts from Women’s Studies and a boy. Eric shook our hands and called me Mrs. even when I told him he could stop. He stood in the kitchen and chopped carrots with the dignity of a man who has learned to be useful without applause. He and Kayla spent an hour on the living room floor assembling a bookshelf with more laughter than instructions. The girls’ support group hosted a panel at the hospital and Kayla invited him to sit in a row of folding chairs in a fluorescent room and learn. He took notes. He asked if somebody could send him the reading list. I fell a little in love with him myself and then remembered that was not my job.

On Christmas Eve, my parents sent a card—no money, no critique—just We are here. We are learning. Tea in the spring? We did tea in the spring: public place, daylight, pencils down. They did not cry like people who needed me to mop. My father explained the word coercion in a way that made me forgive him a percentage point. My mother said she would never again choose quiet over discomfort. They did therapy, which they told me only when I asked. They did not ask for the girls yet. They did not show up at our door. They mailed a letter in January that said We are proud of her and by her they meant Kayla and then Reese and then, in tiny print at the bottom like a footnote they had to work for, you.

Spring did what spring does—arrived late and all at once. Kayla’s hair grew into a shape she called “bird’s nest chic.” Reese brought home a certificate with a foil star that said CITIZENSHIP and we taped it to the fridge and then to her door and then to the underside of the kitchen table because she wanted to see it from below. Detective Gomez stopped by once on a Saturday morning with a box of donuts and no agenda, sat at our island and told the girls about her dog and nothing else. “You need to see me without a crisis attached,” she said, dexterity with chocolate glaze impressive.

At the end of April, the school hosted a “healthy relationships week.” Mattie asked Kayla if she would help plan the assemblies. “I’m not an expert,” Kayla said, and Mattie said, “You survived. That’s expertise.” They built talks that didn’t scold and didn’t terrify; they taught simple scripts and exit plans and what to do when your gut says “no” in a voice your friends make fun of. They taught teachers how to hear the phrase I’m fine and translate it into Please notice that I am disappearing.

The night before the first assembly, Kayla stood at our kitchen counter with index cards and a Sharpie and wrote RED FLAGS in caps. She put isolation and jealousy as love and apologies with strings. Then she added one more line: Your sister knows. She held the card up to the light like it might catch fire. “I want to say her name,” she said. “Is that… okay?”

“Ask her,” I said. Reese nodded solemnly. “You can use my name when it helps people,” she said, the magnanimity of nine-year-olds making saints look like laggards. Kayla added thanks, Reese in parentheses and carried her cards upstairs like prayer.

The assemblies were messy and loud and imperfect. The freshmen clapped at the wrong parts, the juniors leaned back in their chairs like not being impressed had currency, and somewhere in the back a boy yelled “What about boys?” and Kayla said “Them too” without missing her place. After the first talk, a girl with chipped nail polish stopped Kayla outside the auditorium and whispered that her boyfriend liked to “give marks” and bought her things after. Kayla walked her to Mattie’s office and texted me later: People are telling the truth. I texted back: Firsts. She sent a photo of the cookie cake from her college group: We’re consistent.

Summer came and with it a surprise I thought would make me faint and instead left me weirdly calm. Reese asked if she could get a haircut at a salon. “I want to raise money for the hospital fund,” she said. “They said they sometimes do head-shaving fundraisers for kids with cancer. But I’m not a kid with cancer, so I’ll just cut it short and make a sign and talk about not hitting and believing kids and maybe people will give money because my hair is my thing.”

“Are you sure?” I asked, a flicker of the bathroom in my chest.

“I’m sure,” she said. “This time I ask first.”

Kayla surprised me by saying, “Me too.” She had grown out her hair long enough to hide behind again if she wanted. She didn’t. “Let’s reclaim the sound,” she said, the word reclaim new in her mouth and fitting.

On a Saturday afternoon, we set up two chairs in the shelter’s parking lot under a string of paper lanterns. A line of people stood around with cups of lemonade and small bills. The hairdresser from down the block volunteered her clippers and laid a towel around Reese’s shoulders with the same ceremony she uses for brides. “This time,” she said, “we cut because we want to.”

The clippers hummed and the sound was the same and entirely different. Reese grinned like she was making a tornado laugh. Kayla closed her eyes and tears leaked out anyway and she lifted her chin into the buzzing like a blessing. When they were done, we swept the hair into bags and gave it to a man from the cancer center who thanked us for being the right kind of dramatic.

We raised $742. When Reese handed the shelter coordinator a ziplock full of twenties and singles with a gummy bear stuck to one, the woman put a hand on Reese’s head and said, “We’re going to put this into the hands of someone who needs to feel held.” Reese nodded as if she’d been told a bedtime story she’d written herself.

In August, Kayla moved into an off-campus apartment with two roommates who had rules posted on the fridge about dishes and consent. She taped a photo of Reese with a buzzcut to the mirror and wrote hero underneath in dry-erase marker. Eric carried boxes and installed curtain rods, then left the drill on their counter because he had learned men get to be gentle without leaving women tool-less.

I went back to work part-time at the library, taught a class on how to find the right answer instead of the loud one. My husband started leaving work at four on Thursdays without apologizing to anyone and made spaghetti that tasted like relief. We held our family check-in at the park when the weather let us and in the car when it didn’t. Reese started fourth grade and argued with her art teacher about why glue is a metaphor. Kayla took a self-defense course and learned how to say “no” while walking backwards and how to use her voice as a thing with edges. She called me after the class and said, “I didn’t know you could teach confidence like a skill.”

In October of Kayla’s sophomore year, Julian tried one more trick—filed a motion to seal the juvenile record and erase the restraining order when Steven turned eighteen. Our lawyer filed a response that used words like ongoing risk and attached a detention report with four fights and three attempts to contact Kayla via proxies. The judge denied the motion with a note in the margin that said, in handwriting suspiciously like fury, No. That one syllable has become my favorite prayer.

On the anniversary of the morning the clippers sang, we ate cake for breakfast. I told the girls I wanted to take a picture. Reese rolled her eyes and then positioned us like a director who pretends not to care about angles. Kayla stood between me and my husband, her head bare because she had shaved again last week for a fundraiser on campus. She looked into the camera like she had forgiven it for stealing. My husband put his hand on my back and said, “We did okay,” and I said, “We’re doing,” and he kissed my shoulder like a vow.

That evening, when the house went quiet and the streetlight cast its simple gold across the sidewalk, I took out the list taped inside the cabinet and added one more line, in pen, not pencil: We kept the door open for the love that knows how to knock. Then I closed the cabinet and left the porch light on because this is the house where girls come home to people who believe them.

We are not the first family to survive a boy like Steven. We won’t be the last. I wish systems always moved this way for everyone. I wish every Gomez got the budget she needs and every Mattie got three more counselors and every judge learned to say “No” with mercy and steel. I wish for less clatter and more quiet bravery and that it didn’t take a nine-year-old with a recorder to teach adults their work. But wishes are only useful when you pick one and put it in your pocket and use it to hold open a door.

Sometimes, months later, I still hear the buzz behind that bathroom door. My body goes hot at the memory and then cools with the truth: we are here; she is safe; the sound that terrified me is also the sound that stopped time from running off with my child. The noise lives on in my bones like a warning and a hymn.

You never think the sound of clippers will be the sound that saves your child.

But I have learned to make peace with unlikely music.

I hear it now in other rooms—in the steady hum of a detective’s voice on the phone, in the click of a judge’s pen, in the buzz of fluorescent lights over a support group where kids teach each other how to translate fear into language, in a hairdresser’s careful hands as she returns control to a head that took it back. I hear it in my daughters’ laughter down the hall, in the soft snick of our front door, the lock sliding home.

And sometimes, just before I turn off the kitchen light, I take the pink recorder from the drawer and hold it for a second. It’s quiet, which feels like a miracle and a promise. I put it back. I turn off the lamp. I leave the porch light on.

The End

News

His wife said, “I regret marrying my husband, I should have chosen his friend instead,” What He Did… CH2

Part I — The Sentence That Changed the Room Kennedy didn’t mean to hear it. He wasn’t snooping, not then,…

MY DAUGHTER CAME BACK FROM HER HOUSE, HER FACE SWOLLEN AND BLOODY. I HELD HER CLOSE AND CRIED… CH2

Part I — The Night of the Lie Her body gave out the moment she crossed my threshold, the way…

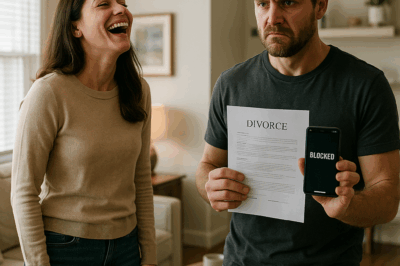

I Laughed That Some Of His Friends Tried Me—Now He’s Filing Papers And Blocking Me CH2

Part I Rowan spends the entire Sunday dinner being a cathedral. By the time Margaret sets the roast down and…

Husband Has Baby with Sister, Dumps Me ➡ 3 Years Later, Surprise Meeting, Ex’s Shocked Face. CH2

Part I If you’d asked me to name the moment my marriage cracked, I’d say it wasn’t big. Not the…

Sister-in-law happy at funeral because my surgeon brother left her lots of money. CH2

Part I The day we buried my brother, the sun came out like it had been paid to. It turned…

“We Left My Stupid Husband Miles AWAY From Home as a JOKE, But When He Returned It Was NOT Funny…” CH2

Part I I can tell you the exact moment I should have trusted my gut. It wasn’t the tight smile…

End of content

No more pages to load