The Knock of Heels

The call came at 1:17 p.m., just as the office coffee machine shuddered and died with a sound like a mechanical sigh. I’d been staring into a spreadsheet so long the cells had begun to look like city blocks. When my phone flashed Sacramento General Hospital, I said hello already braced for a wrong number.

“Mrs. Thompson?” a woman asked. “This is the emergency department. I’m calling about your husband, David.”

The copy machine on the other side of the bullpen clicked and whirred its way to a new life. The office noise fell away until her voice was the only thing left.

“He was in a motor vehicle collision. An eastbound driver ran a red light and struck his sedan on the driver’s side at Third and L. Paramedics intubated him en route. He is in surgery now. The doctor would like to speak with you as soon as you arrive.”

“Is he—” The word alive wouldn’t leave my mouth. “Is he—”

“He’s in critical condition,” she said. “Please drive carefully.”

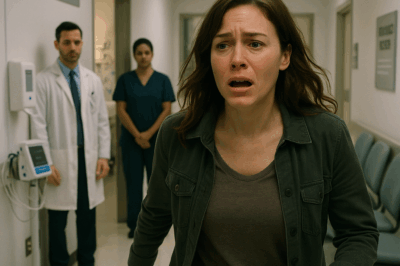

I don’t remember crossing the lobby or the elevator ride that lasted forever. I do remember my colleague Sarah catching me as my knees buckled halfway to my desk.

“Rachel, what’s wrong? You’re white as a sheet.”

“David,” I said. “Accident. Hospital.”

“Go,” she told me. “I’ll tell Mark. I’ll cover your client call.”

The keys shook in my hand so hard I missed the ignition twice. On the third try, the engine caught and the radio blared a car commercial that promised nobody pays more than they have to. I slapped it off and drove twelve minutes that felt like an hour, stopping at reds because the math of how accidents happen had never seemed so clear. Everywhere, people were living their lives unaware that my husband was between anesthesia and a darkness I refused to name.

At Sacramento General, a volunteer gave me a visitor badge and a strange little smile like condolences and good luck tangled in the same thread. A doctor met me before I’d even sat down—fifties, white coat, gentle hands that held severity like it was part of his job.

“I’m Dr. Johnson,” he said. “Your husband suffered a severe closed head injury. There was subdural bleeding. Our neurosurgical team evacuated the hematoma. We’ve controlled the intracranial pressure for now. The next twelve hours will be critical.”

“Is he… will he wake up?” My voice felt like it was coming from somewhere outside my body.

“I don’t know,” he said, honest in a way that didn’t feel cruel. “But the surgery went as well as we could have hoped.” He slid a paper across the counter—consent for something I signed without reading because time suddenly had teeth. “You can see him for ten minutes. ICU rules.”

“Ten minutes,” I repeated, as if the number could be negotiated by repeating it.

I called Emma’s school and tried to sound like a woman who wasn’t shaking. “This is Rachel Thompson—Emma Thompson’s mother. There’s been a family emergency. I need to pick her up early.”

When I reached the car, my hands belonged to someone trying to hold water. On the drive to the school, the red lights were too long and the green lights were too short. I parked at a crooked angle and jogged to the office with the gait of a person who had forgotten what walking was for.

“Mom?” Emma said, surprised and delighted all at once when she hopped into the Honda, pink backpack bumping against her shoulders. “Why so early?”

“Dad’s been hurt a little,” I said, aiming for breezy and missing. “We’re going to visit him at the hospital.”

“Is Dad okay?” Her eyes searched my face the way kids do when they’ve learned the truth is a moving target.

“He’ll be fine,” I said. “He’ll definitely be fine.”

I said it for her. I said it for me. I said it because it felt like prayer.

In the ICU, machines hummed and heart monitors did their slow green cursive. When the nurse pushed open the glass door to David’s bay, I had the sudden, foolish thought that he would sit up and laugh and tell me the whole thing had been a spectacular misunderstanding. Instead, there was my husband—bandage wrapped around his head, tubes everywhere, the ventilator pushing and pulling his chest in a rhythm that didn’t belong to him. He looked like a photograph of a man I knew taken from very far away.

“Daddy!” Emma cried, flinging herself toward the bed. Her voice broke on the second syllable.

“Sweetheart,” I said, catching her and pulling her close before she could touch a line the wrong way. “Soft voices, okay?”

A nurse with eyes that had seen too much and were still kind touched my elbow. “Talk to him,” she said softly. “Hearing is often the last sense to go and the first to come back.”

I took his hand. It was colder than it had ever been and still familiar. “David,” I whispered. “It’s me. I’m here. Emma’s here.” I pressed my cheek against his knuckles the way you might check if a stone is warm from sun. “Please wake up.”

Emma climbed on the chair and leaned over. “Daddy,” she announced, because proclamations are how eight-year-olds keep the world from tilting. “Something funny happened at school today, but I’m not telling until you wake up.”

We stayed our ten minutes like they were a window we could prop open. Then a nurse with contrition in her posture ushered us back to the waiting room and handed me a blanket the color of lost things.

“Tonight is critical,” Dr. Johnson told me later, with the steady cadence of a man who has learned to speak hope without lying. “We’ve controlled the swelling for the moment, but swelling can be stubborn. Will someone be staying?”

“Yes,” I said. “I will.”

Emma fell asleep with her head on my lap, the blanket tucked up around her chin, thumb pressed between the fox and her mouth the way she’d done when she was a toddler who needed proof the world existed. I stroked her hair and watched the doors as if, through vigilance, I could keep bad news from entering the room.

Somewhere around three, a medic called out impenetrable numbers as he rolled a new patient past. At four, an ambulance siren sounded faint and far. At five, a phlebotomist laughed at a joke as if laughter were proof you could bring into a room.

At seven, Dr. Johnson found me with coffee and the only mouthful I could swallow.

“He seems to have passed the acute crisis,” he said. “The numbers are holding. That doesn’t mean we’re out of the woods. But we’re not lost in them either.”

Relief hit so hard my knees went weak and I had to sit down. I cried for the first time since the call—quiet, ugly tears that didn’t improve anything and made breathing possible. Emma woke, blinking up at me as if she were rising from a deep lake.

“Did Daddy wake up?” she asked.

“Not yet,” I said. “But he’s fighting. He always was stubborn.”

The next three days were a new kind of time. Work colleagues brought food and murmurs in the language of casseroles. Friends texted hearts and prayer hands and here if you need anything. Emma colored in a book with a seriousness I had seen only twice before—once when she learned to tie her shoes and once when she discovered grief is a town you can live in. David’s eyelids fluttered on the second day like a bird trapped in a window. On the third, the ventilator settings changed and the nurse said, “That’s good,” the way people in crisis redefine words.

“Mom,” Emma said that evening, just before visiting hours ended, “should we go home tonight? You look crumpled.”

“You have school tomorrow,” I said, smoothing her hair back. “Yes, let’s rest at home. We’ll be back in the morning.”

She closed her picture book, but then tilted her head like a bird that has heard something only it can hear.

“Emma?”

Her hand shot out and gripped my wrist. It wasn’t the grip of a child; it was the grip of someone who has made a decision that will change the room.

“Mom,” she whispered. “Hide.”

“What?”

She didn’t explain. She pushed me—small hands with impossible force—toward the supply closet at the back of the ICU bay. It was a narrow space where gauze and spare IV pumps lived, a place for bandages and breathers, not wives. She tugged open the door, nudged me inside, and left a finger-width of air before easing it mostly closed.

“Emma,” I hissed. “What are you doing? Why would we—”

“You’ll understand,” she whispered through the crack. “Please, Mommy. Be quiet.”

I crouched among saline bags and a rolling stand, heart slamming, mind a blank whiteboard. Through the slim wedge of light, I watched my daughter climb onto the bedside chair, swing her legs under her, and fold her hands like a small dignitary at a large meeting.

The corridor’s ambient murmur stilled into something more specific: the click of heels. Nurses wear soft soles that whisper. These heels announced themselves. Firm. Certain. Practiced.

The ICU door opened. “Excuse me,” Emma said in her careful inside voice, “visiting hours are—”

“David,” a woman’s voice said, warm and trained to sound like home. “It’s me. I was so worried.”

My stomach dropped so hard I thought it might make a sound. The voice was unfamiliar. It was not a stranger’s voice. It was an intimacy I had never met.

She stepped into my sliver of view—a blonde woman in a nurse’s uniform so crisp it might have been folded in a magazine. Hair pulled back with effortless precision. Hands manicured into competence. She moved like she belonged in rooms where serious things happened and people deferred to her expertise. She set a bag on the counter, ignored the visitor’s chair, and took David’s hand with a touch that was practical and proprietary at once.

She leaned forward and kissed his forehead. It was not the brisk kiss a nurse gives to a patient because ritual helps. It was the kiss I gave him in kitchens and in doorways and after arguments.

“Who are you?” Emma asked, standing so quickly the chair scraped backward.

The woman smiled, small and exact. “Jennifer. Jennifer Miller. I’m a nurse here.”

“And?” Emma pressed, and I wanted to laugh because eight is the age you learn there’s always an and.

“And,” the woman said, pausing for emphasis, “I’m David’s wife.”

The closet was suddenly very small. The air was gone, replaced by a static that made it hard to hear my own breath.

“That’s a lie,” Emma said, and just like that, I loved my daughter in a brand-new way. “Mom is Dad’s wife.”

Jennifer reached into her bag and produced a stiff-looking stack of papers with blue ink where the state likes it. She held one out at Emma’s chest like authority was contagious. “Marriage certificate,” she said. “David Thompson & Jennifer Miller. Ten years ago.”

My knees bent against the mop bucket and didn’t find the floor. Ten years ago is when David and I had married. Ten years ago is where our Christmas ornaments start.

“Who are you people anyway?” Jennifer asked, warmth gone, efficiency slipping. “David and I are the real married couple. We have a son. Michael. He’s seven.”

The name hit me like an oar. The number did too. I thought of David’s recent headaches and his sudden need to “work late” twice a week. I thought of the look on Emma’s face sometimes when he said he’d be back by dinner and wasn’t. You catalog these things because it makes you feel like you were prepared. You never are.

“Mom,” Emma said—my name a breath—and the closet door was suddenly a punishment. I pushed it open and stepped into a room that didn’t belong to any of us.

“You’re the mother,” Jennifer said, giving me a cool once-over. “The other woman David always talked about.”

“What do you mean, other?” My voice was shaking too hard to hold static. “I’m David’s wife. Rachel Thompson. We married ten years ago. Emma is our daughter.”

She laughed—a sound that had learned how to wound. “Poor thing,” she said. “You’ve been deceived.” She brandished the paper like a weapon. “Face reality. David and I are legally married. I’m listed as his spouse on every hospital form. We have a son. What you have is a romance with a liar.”

“Those documents are fake,” I said, even as the blue ink glowed legal. “I have our certificate at home.”

“Oh, that,” she said, pity sharpening into something vicious. “That’s the fake. David’s very good with printers.” She tilted her head as if she were diagnosing me. “He fooled you for five years.”

The number lodged behind my ribs. We’d been together five years. By her count, she’d had him for ten. The math added up to a man divided into two lives like a magician’s trick with a box and a saw.

“Emma,” I said, my voice finding something steadier than outrage, “come here.”

She moved to my side with relief and defiance. Her hand found mine and squeezed in a rhythm that matched my heart.

Jennifer checked her watch like visiting hours had an opinion. “Starting tomorrow,” she said, “I’ll stay with him. You don’t need to come anymore.”

“What gives you the right to even speak to us like that?” I asked. It came out quieter than I intended. Rage was there, but it had nowhere to live yet.

“The law,” she said, already reaching for her bag. “When he wakes up, this will all be cleared up. Your… charade will be over.”

She said the word charade like it rhymed with parade. She left her cologne behind.

The door clicked shut. The heels receded. The room was suddenly enormous and completely insufficient.

“Mom,” Emma said, tugging at my sleeve. “She’s lying, right? She’s lying.”

I knelt so my face was level with hers. My daughter’s eyes had Brennan’s exact earnestness in them. I saw my own fear reflected there too.

“I don’t know yet,” I said. My voice wouldn’t bend to a lie. “But we’re going to find out.”

The next morning I stood in the hospital records office with a pen I wasn’t going to sign anything with.

“I’m sorry,” the receptionist said, matching my urgency with professionalism. “The emergency contact we have on file is Jennifer Miller. Listed as spouse.”

“But I’m his wife,” I said, setting my driver’s license on the counter like an artifact.

“I understand,” she said, and she did, you could hear it. “But the record shows a spouse already. You could bring your… documentation? We can add an ‘also notify.’”

“Also notify,” I repeated. It landed in the space where I used to breathe.

From there I went to a law office because it seemed like a place where the world was forced to make sense. The attorney was mid-fifties and wore her competence like armor.

“Let me see yours,” she said, and studied our marriage certificate like it had confided in her before. “Legitimate,” she said finally. “Filed properly. Which means if Ms. Miller’s is legitimate as well, your husband’s guilty of bigamy.”

“Bigamy,” I said, as if saying it might make it sound less medieval.

“Criminal,” she said. “Also civil. In California, a subsequent marriage is void if a prior one still exists. The first in time is presumptively valid. But this is not a verdict—this is a diagram. We need facts. We verify her certificate. We timeline everything. Meanwhile, you have rights as a defrauded spouse. And your daughter has rights to support regardless.”

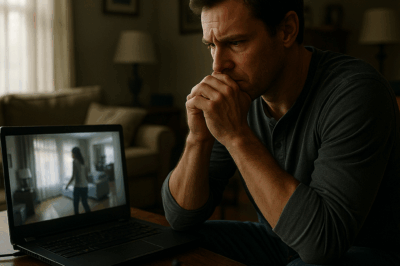

I left with a retainer agreement and the sensation of something under me shoring up by inches. Then I walked three blocks to a narrow storefront above a locksmith, where a rectangular sign read Tom Harris, Investigations and a ceiling fan worked hard.

Tom had a suit that said he’d bought it when Clinton was president and a face like a good detective novel. He listened without interrupting and wrote down names like they were pieces on a board.

“Common,” he said, not to minimize but to categorize. “Men with travel jobs. Two phones. Two sets of everything. We’ll pull county records, run addresses, map employment, look at the IRS angle. Give me forty-eight hours.”

He took forty. On the phone his voice was neither triumphant nor surprised. “Jennifer Miller married David Thompson ten years ago,” he said. “Sacramento County. They have a seven-year-old, Michael. David’s registered official addresses at two places—apartment downtown and a ranch-style in Fair Oaks. Payroll deposits split between accounts. Withholding inconsistent. He’s not just a liar; he’s probably a tax evader.”

“How long?” I asked, although I already knew.

“Five years,” he said. “Half the week here, half there, occasional trips that were actually the other wife. There’s a pattern. There always is.”

When the call ended, I sat on the floor of our living room with the photo albums that had defined our life and realized how light they were.

That afternoon, the ICU called. David was waking. His eyes were open. He was breathing around the tube. Post-operative delirium likely. Come.

I went. Jennifer was already there. Of course she was. She sat in the chair I had memorized for three days and looked like she owned it.

“Rachel,” David said when I stepped into his field of view, and my name on his tongue felt like a theft.

“I want an explanation,” I said, and the way my voice didn’t crack surprised me. “All of it.”

Jennifer stood, folded her arms, and shifted the weight of the room like a dancer hitting a mark. “Enough,” she told him. “You don’t need to play.”

He stared at the ceiling tiles because eye contact requires a kind of courage he no longer had. “I’m sorry,” he said, tears edging without falling. “I married Jennifer ten years ago.” He swallowed. “Then I met you. I didn’t— I couldn’t—” He closed his eyes, perhaps searching for the script. “I didn’t want to lose either.”

“So you created a fake marriage,” I said, and it wasn’t a question.

“At first I thought it would be short,” he said. “But then Emma—” He stopped, as if her name were a cliff. “I loved you both,” he said, like confession were absolution. “I loved you all.”

“If you loved us,” I said, “why has every single moment since the day we met been a lie?”

Jennifer slid a photo out of her bag and held it toward me like a trophy. A boy with David’s eyes and a cowlick grinned into a California sun. “This is Michael,” she said. “Your daughter’s half brother.”

The word brother did the math for me: weekends he’d “swung by the hardware store,” late meetings that had become rituals, the way Emma had flinched when the phone buzzed after nine.

“So my marriage is legally invalid,” I said to the air, the wall, the God who had not signed any of these documents.

“Correct,” Jennifer said briskly. “You have no legal standing. You can’t even—”

“That’s not quite true,” a voice said from the doorway.

My attorney, Ms. Hsu, stepped in like a second act that changes the play. She nodded at the nurse reflexively and then at me. “Even in fraudulent marriages, victims have rights,” she said, as if she were speaking to a much wider room. “You can seek civil damages. Your child has an absolute right to support. And Mr. Thompson”—she glanced at the bandage, then at his eyes— “may be charged criminally with bigamy and fraud.”

David put his hand over his face. The monitor beeped faster and then, mercifully, settled.

I left before someone told me to. In the hall, Emma sat on a vinyl chair the color of wilting celery, legs swinging, backpack at her feet, hands on her knees like she’d practiced being in charge while I was gone.

“Mom,” she asked, voice steady and small, “did Dad tell the truth?”

“Yes, baby,” I said, crouching so my forehead could find hers. “He did.”

She studied my face the way she used to study picture books, index finger tracing lines. “Is it just us now?”

“It’s us,” I said. The answer felt like a landing, not a fall. “We’re a real family.”

She nodded, as if a piece of the map had finally matched the terrain. “Okay,” she said. “Can we have pancakes for dinner?”

“Yes,” I said, laughing on a breath that held tears. “We can have pancakes for every dinner if you want.”

“Not every dinner,” she said seriously. “We’ll get bored.”

In the elevator down, a nurse got on with a cart full of sterile packages. She looked at Emma, then at me, and smiled in the way medical people do when they get to be human.

“Big day?” she asked.

“You have no idea,” I said.

In the car, Emma buckled herself in and then leaned forward to tap my shoulder, the way she did when she wanted to underline her point.

“Mom,” she said, “when I pushed you in the closet… did you think I was weird?”

“I thought you were brave,” I said.

“I could tell the heels weren’t nurse heels,” she said matter-of-factly. “Nurses don’t walk like that when people are sleeping.”

I gripped the steering wheel and let my daughter recalibrate my universe.

“Thank you,” I said.

“Okay,” she said, and pulled out her fox to show him the sunset.

Outside, the sky was the color of things that survive fire. I drove toward an apartment we didn’t live in yet and a life we hadn’t started. In my head I made a list: a lawyer, a private investigator, a therapist, a new school form, a recipe for pancakes that never failed.

I didn’t think about Jennifer. I didn’t think about the boy in the photo. I didn’t think about David’s eyes when he said both. I thought about a closet where my daughter had put me to save us both from a worse hiding place.

In the mirror, the first star caught on the glass like an error someone had left for us to find.

We were going to start over. We were going to start clean. We were, whether the law believed it or not, a family made of a mother who wouldn’t lie and a child who knew how to listen to footsteps.

The Paper War

The morning after the closet and the confession, the light over Sacramento looked indecently ordinary. The world, it turned out, doesn’t rearrange itself to match your catastrophe. Your catastrophe has to learn how to sit in the world and not knock over the furniture.

Ms. Hsu called at 7:14 a.m. “I’ve filed a petition for status determination and emergency relief,” she said. “It asks the court to recognize your marriage as voidable due to fraud, to establish Emma’s custody and child support immediately, and to preserve assets. We’ll also file a criminal complaint with the DA’s office. Do not speak to David without me, even if his feelings show up with flowers. Understood?”

“Understood,” I said, staring at the morning sunlight making stripes on the living room wall like a crime scene they hadn’t dusted yet.

“And Rachel?” she added, softer. “You’re going to want to solve everything today. You can’t. Pick the next right thing and do that. Then the next.”

The next right thing was coffee and a lunchbox for Emma and a note to her teacher that said “family change” in a bland handwriting that didn’t betray a house burning down. When I pulled into the school circle, she put a hand on my wrist.

“You’re not lying to me, right?” she asked, eyes so steady I had to look away first.

“No,” I said. “Not now, not ever.”

She nodded like she had just granted me a license. “Okay,” she said, and did the bravest thing I saw all week: she climbed out of the car and went to school.

At Tom Harris’s office—the one above the locksmith with the fan that never stopped—he had a stack of files already tabbed. He slid one to me like an indictment and a mercy.

“Two addresses,” he said, tapping the photos. “Downtown apartment you know. Fair Oaks ranch you don’t. Your man split everything except his reflection. He used a payroll diversion to funnel cash into a separate account. He told Jennifer he had corporate travel to LA and Portland. He told you he had regional trainings in Reno and Boise. He was mostly in Citrus Heights, mowing a lawn.”

I breathed in through my nose and tasted pennies. “Can I see the house?” I asked, surprising us both.

He tested my face like a carpenter checking a joint. “I can take you by,” he said. “But it’s trespass if we go in. You don’t need another crime.”

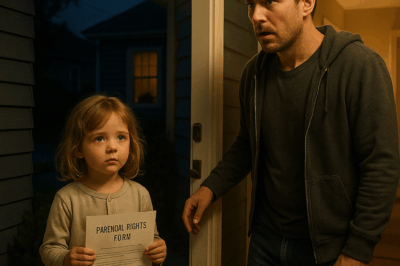

We drove past the Fair Oaks place like tourists. It was exactly what it should have been: a low-slung California ranch with bougainvillea climbing the trellis and a basketball hoop slightly off level over the driveway. There was a scooter on its side near the porch and a plastic dinosaur army lined up on the railing. A woman I didn’t know drove up as we slowed. She put the car in park and got out, a little boy’s backpack slung over her shoulder. Michael ran past her and cannoned toward the front door, banging it open and shouting for his mother. Jennifer stepped into view, hair pulled back, still that effortless precise. She laughed—warm this time—and caught the boy as he launched himself, then disappeared inside.

“Okay,” I said, when I remembered I had a voice. “Okay.”

Tom didn’t say I’m sorry because he’s good at his job. Instead he asked, “Want the tax angle?”

“No,” I said. “I want to survive the next hour.”

He nodded and pointed at a line on the document. “I can also tell you he’s been making deposits into an account in Emma’s name. Small. Regular. Might have believed that made him a good person.”

“That’s for her college,” I said, and then laughed because sometimes rage hooks humor and drags it to the surface. “Or for therapy. Or a fundraiser for fireworks.”

Back downtown, Ms. Hsu texted: Hearing at 2:30. Dept. 14. Judge McEwan. Bring your ID and copy of your marriage certificate. Also bring a picture of Emma because judges are people.

Courtrooms smell like industrial cleaner and fear. Department 14 had a high ceiling and a low tolerance for nonsense. Judge McEwan looked like he’d been born scowling and then found out it made him popular. He shuffled papers like they had misbehaved.

“Ms. Hsu?” he said, when our case was called.

She stood, immaculate and lethal. “Petitioner seeks emergency orders,” she said crisply. “Recognition of her status as defrauded spouse, exclusive custody of the minor child, temporary support, and mutual restraining orders preventing dissipation of assets.”

The opposing side wasn’t there; David was too busy learning to sit up and Jennifer had a seven-year-old who needed peanut butter and cartoons. It didn’t matter. The law had a script for this too.

“On the papers presented,” the judge said—which is courtroom for you came prepared—“the court finds good cause to issue temporary orders. Petitioner is awarded temporary sole legal and physical custody of the minor. Respondent is ordered to pay guideline child support and maintain existing health coverage. Petitioner is granted exclusive use and possession of the family residence. Both parties are restrained from transferring or encumbering assets without further order.”

I exhaled a breath I hadn’t realized I’d held since the closet. Paper armor, Ms. Hsu had called it. I felt the weight of it settle around us.

“Counsel,” the judge added, peering over his reading glasses, “advise your client the criminal exposure here is not theoretical. The DA’s office has a unit that takes an interest in bigamy when it involves fraud. I suggest he find counsel who can count to two and advise him which marriages to keep in his mouth.”

“Yes, Your Honor,” Ms. Hsu said.

Outside on the courthouse steps, the sun made the white stone look self-righteous. A reporter I’d never met approached with a microphone and the entitled look of someone who has never had to hide in a closet.

“Mrs. Thompson? Any comment on your husband’s double life?”

“Yes,” I said, and watched her prepare for a sound bite. “We’re fine. My daughter and I are going to make pancakes.”

She blinked. “Pancakes,” she repeated, like I’d mispronounced justice.

“Blueberries,” I added, then walked away while she tried to figure out the angle.

At home, Emma sat on the rug in her room drawing a house with two windows, a door, and a sun so large it took up the entire top third of the page.

“Where should I put the fox?” she asked, and I realized she was drawing ourselves into a place so we could live there.

“In the window,” I said. “So he can watch for us.”

We made pancakes. We burned the first one because that’s required by a law no judge has to sign. We ate the rest at the table where we had eaten everything that had happened to us so far. After dinner, Emma took a deep breath, then announced as if at a press conference, “I don’t want to see Dad when he asks to visit.” She looked at me for the push-back she’d learned to expect from adults.

“You don’t have to,” I said. “Not now. Maybe not ever. Visitation exists, but so does your voice. We’ll tell Ms. Hsu.”

She nodded like she had just negotiated a treaty. “Okay.”

The paper war marched forward with the slow, steady brutality of a tide. Ms. Hsu filed a civil complaint for fraud, intentional infliction of emotional distress, and constructive trust on the marital income earned during the years David played husband twice. We requested financial records. Banks obliged. We served subpoenas on employers. HR departments sent PDFs with the bored efficiency of people who have seen worse. We filed a criminal complaint with the DA; an investigator with a mustache shaped like a threat took our statements and said he would be in touch.

Jennifer’s lawyer—slick, late, and expensive—filed a petition for dissolution on her behalf, citing irreconcilable differences with a footnote that should have read also there’s another wife. In a rare moment of symmetry, she asked the same court for custody of Michael, child support, and damages. She did not ask me for forgiveness. She did not need it.

Twice a week I went to the hospital and sat at the edge of David’s bed while he stitched himself back together. The first time I went without Ms. Hsu, I almost reached for his hand out of habit. Then I remembered I had signed something else: a promise to myself.

“We’re divorcing,” I told him. “And I’m filing civilly and criminally. Emma doesn’t want to see you right now.”

He turned to the window. “She will,” he said. “She’s a daddy’s girl.”

“No,” I said, and the word left my mouth like a clean cut. “She’s Emma. You tried to make her job be loving you. I’m not going to let her keep it.”

He pursed his lips, a child denied dessert. “I loved you,” he said, as if the sentence could unindict him. “Both of you. All of you.”

“You loved the way we looked at you,” I said. “That’s not the same.”

Jennifer arrived for the next slot, her perfume rushing into the room a second before she did. She took the chair like it was a podium.

“You can stand down,” she said. “The hospital has corrected the emergency contact. I’m primary.”

“I’m not competing with you,” I said. “There’s no prize at the end of this. Enjoy the paperwork.”

She blinked, caught off guard. She had been told there would be a contest. She did not know what to do with a field not marked.

“You’re smug for someone whose wedding album is going in the trash,” she said.

“I already took it off the mantle,” I said. “We needed the space.”

Ms. Hsu met me in the corridor and handed me copies of filings like a priest with sacraments. “There’s a concept called putative spouse,” she said. “California recognizes it. It means a person who enters into a marriage in good faith, unaware of impediments, is entitled to equitable relief. It was a doctrine born to keep women like you from being ruined by men like him. It’s old law. It’s good law. It’s yours.”

“Is there a doctrine for putting your lawyer in your will?” I asked.

“Yes,” she said, deadpan. “It’s called a conflict.”

We moved into a two-bedroom apartment with a balcony like a promise. It had a kitchen that worked and a living room that accepted our rug without complaint. I hung three things on the wall: Emma’s sun-dominant house drawing, a framed print of a fox in a sweater, and a calendar with no business trips on it.

On the second Saturday, I took Emma to Target to buy stupidly perfect new towels and an unnecessary pillow shaped like a star. In the bedding aisle, she asked, “Do we have to change our names?”

“We’re Thompsons because you are,” I said. “But if you ever want to be something else—if you want my maiden name, or your own invention—we’ll talk about it. We can be whatever we decide is true.”

She nodded and then did what children do when they’ve had enough adult: she begged for slime.

“Fine,” I said. “But it lives on the balcony.”

“Agreed,” she said solemnly, extending a hand to shake.

In the weeks that followed, Emma thrived in the way kids do when the person who is supposed to show up actually shows up. She slept through the night. She stopped listening for a car that might or might not come. She learned to do a cartwheel with the kind of wild inconsistent success that makes a mother clap until her hands hurt. She told her fox secrets and the fox told me none.

The DA’s investigator called to say they were charging David with bigamy and filing an enhancement for fraud. His public defender reached out to Ms. Hsu to ask if we would be open to a plea. “We’re open to him saying guilty,” she replied. “We’re open to him writing checks.”

David pled to a misdemeanor bigamy count and a felony fraud charge that bought him two years of suspended time and a career that was suddenly very allergic to him. His company—bravely, belatedly—terminated him for cause. The HR email said integrity, values, trust, and tasted like a meeting that should have happened years ago. He moved into a small apartment with beige carpet and a view of the parking lot. He texted twice to ask if he could see Emma. Both times I replied with Ms. Hsu’s number.

Jennifer texted me once, out of the blue, a message that read: We’re both victims, aren’t we? I stared at it a long time while the kettle boiled. I typed Yes and then deleted it. I typed Sometimes and deleted that too. In the end, I wrote, We’re both survivors. She replied Okay, and that was the last time we spoke.

By month three, the paper war had settled into filings and counters, orders and compliance. Money moved through channels it should have floated through all along. Emma and I had a routine: breakfast, school, work, dinner, bath, book. On Thursdays, pancakes. On Fridays, movie night with a blanket that smelled like laundry and a bowl of popcorn big enough to qualify as a mistake. On Sundays, the farmer’s market and a walk by the river where the geese judged us and we judged them back.

One night after dinner, Emma looked up from her homework and asked, “What’s a real family?”

I put down the dish towel and leaned against the counter because nothing should be answered mid-task.

“A real family is people who tell the truth and show up,” I said. “People who pick you up when you’re tired and put you down when you’re asleep. People who make pancakes when the world falls apart and who don’t make you feel like you have to be small to be loved. Blood helps. It doesn’t define.”

She thought about that, nodding the way you nod when you decide to remember something. “Then we’re a real family,” she said.

“We are,” I said. “The best one I know.”

She grinned, then returned to adding fractions, which suddenly seemed easier than any of the math we’d been asked to do.

Six months to the day after the ICU and the heels, we stood on the balcony of our apartment hanging laundry in a sun that felt like something you get to keep. Emma pegged socks to the line with fierce concentration.

“Can I invite Sarah this Sunday?” she asked. “For pancakes? She says her mom’s pancakes are good but not as good as yours.”

“I will accept that challenge,” I said.

We had done it. We had built a life out of documents and breakfast. We had survived the paper war. There were still filings to file and checks to be cashed and a court date for a dissolution that would be a formality because our marriage had been a story, structurally unsound, beautifully decorated, not permitted. But what mattered had found its shape: a child asleep in a bed that didn’t expect her to keep secrets; a woman who knew how to turn off a phone; a fox on a dresser watching the door, just in case.

At night, when the balcony breeze moved the curtain, I could smell someone else’s laundry soap and the faint sweet of the neighbor’s jasmine. I would sit with a book I wasn’t reading and let the ordinary cover me like a blanket.

Sometimes, I would see David in a parking lot or a grocery store aisle, eyes down, shoulders curved. He would look up and our looks would meet and pass like weather fronts. Once he lifted a hand, then lowered it, as if he had to relearn every small gesture. He said nothing. Good. Because I had no appetite left for his sentences.

On a Tuesday, Ms. Hsu called to say the civil settlement was signed. Damages. Fees. A constructed trust that caught the money he had tried to send in too many directions and channeled it toward Emma’s future. “It’s done,” she said, and I realized I had been holding myself at a slight angle, waiting.

After I hung up, I went to Emma’s room. She was building a city for her fox out of blocks. “What should we name it?” she asked.

“Whatever you want,” I said.

She stacked two red ones and placed a blue across the top like a bridge. “Truth,” she said. “It’s called Truth.”

I laughed and then didn’t, because it was the right name.

“Truth it is,” I said, and helped her raise a wall that would hold.

Rooms With Doors

The day of the dissolution hearing dawned gray, the kind of colorless sky that tells you not to expect drama. I packed Emma’s lunch, double-checked her homework folder, and kissed the top of her head before dropping her off at school. She skipped toward the doors, her fox sticking out of her backpack like a passenger.

“Good luck in court, Mom!” she called, loud enough that two teachers turned their heads.

I smiled, though my stomach twisted. Eight-year-olds shouldn’t have to wish their mothers luck in court. But this was the life David had signed us into with his two signatures, his two vows, his two households.

The Courthouse

In Department 9, the air smelled like coffee burned two hours ago and floor polish. Judge McEwan presided again, eyebrows still carved into permanent disapproval. On the other side, David sat next to a public defender, his head bandaged less dramatically now but his posture a study in defeat. Jennifer sat behind them with her attorney, her son Michael in the hallway with a babysitter.

My lawyer, Ms. Hsu, rose first. “Your honor, we are here on a dissolution petition that is somewhat unusual. Mr. Thompson contracted two marriages, one in 2013 to Ms. Miller, and one in 2013—subsequently—to my client, Rachel Thompson. Under California Family Code, the first is valid, the second is voidable. However, my client entered into the second marriage in good faith, believing she was free to marry. She qualifies as a putative spouse and is entitled to equitable relief.”

The judge tapped his pen. “Mr. Thompson?”

David’s attorney stood. “We concede the facts. We do not contest the putative spouse doctrine, nor the requests for custody and child support. My client only asks for leniency in the allocation of debts.”

Ms. Hsu’s mouth quirked. “Debts incurred to sustain a fraudulent double life should not burden the victim of that fraud. We request sole legal and physical custody of Emma Thompson, guideline child support, and damages already negotiated in civil court.”

The judge nodded, scanning the file. “Orders are granted. Custody to Ms. Thompson. Support as calculated. Civil judgment affirmed. As for Mr. Thompson—” He paused, fixing David with a gaze sharp enough to shave. “You stand before a court that has seen lies before, but rarely lies this deep. You’ve betrayed not just one household but two. Your suspended sentence in the criminal case remains, but any violation will activate it. You’d better learn to live honestly. Case closed.”

The gavel fell. Paper shuffled. That was it—the end of a marriage that had been more performance than contract.

After the Hearing

Outside the courtroom, reporters hovered again. One asked Jennifer if she felt vindicated. She shook her head. “I feel tired,” she said. For the first time, I almost believed her. We were both women who had been lied to, both mothers patching up children who didn’t ask for any of this.

I didn’t speak to David. He didn’t look at me. It was better that way.

When I picked up Emma from school, she ran to me with the kind of abandon that makes strangers smile. “Are we divorced now?” she asked, panting.

“Yes,” I said. “We’re free.”

She grinned. “Can we get pizza?”

“Of course.”

The Apartment

The new apartment became ours in the way places do when you fill them with routines. We painted Emma’s room lavender, hung fairy lights across the ceiling, and placed her fox on the pillow as if he were a landlord. On weekends we made pancakes for her friends, the smell of butter and syrup turning the small kitchen into a cathedral of ordinary joy.

One Saturday morning, Emma asked, “Do you miss Dad?”

I stirred batter, buying time. “I miss who I thought he was.”

She nodded solemnly. “But not who he really was.”

“Exactly.”

She grinned. “Good. Then we match.”

Rooms With Doors

Therapy became part of our weeks—Emma with a child counselor who taught her how to name feelings, me with a woman who reminded me that betrayal isn’t an identity. We learned language we didn’t know we needed: boundaries, resilience, closure.

Emma drew a picture in one session: a house with three doors. She explained, “This is our house now. One door for you, one for me, and one that locks forever for people who lie.”

“That’s smart,” the therapist said.

“It’s true,” Emma replied.

I realized then that she had given me the metaphor I needed: rooms with doors. We could build our own house of truth, room by room, each with doors we chose who to let in.

Six Months Later

David pled guilty to bigamy and fraud, receiving a suspended sentence and probation. He lived alone in a dull apartment, working a job beneath his qualifications. He texted once asking to see Emma. She answered on my phone: I don’t want to. I respected that.

Jennifer divorced him too. She raised Michael with quiet determination. We met once at the lawyer’s office, both of us gaunt from the war. She said, “We were both victims.”

“Yes,” I said. “But now we’re survivors.”

We shook hands and went back to our separate lives.

The Picnic

On a bright Saturday, Emma and I carried sandwiches to the park. She spread out the blanket, fox in tow. We ate, laughed, and let the sun soak into our bones.

“Mom?” she asked, looking up at the sky.

“Yes?”

“Are we a real family now?”

I brushed her hair back and kissed her forehead. “We always were. But now we know it.”

She smiled, took my hand, and whispered, “Best family in the world.”

As the sun sank and the first stars pricked through, I understood something final: our family wasn’t defined by marriage certificates or betrayals or courts. It was defined by trust, by love, by the sound of my daughter’s laughter echoing across the park.

We had rooms with doors. We had truth. We had each other. And that was enough.

✅ THE END

News

Locked in a hot storage by husband & MIL. Hospital called: “They’re dead.” But what I saw there… CH2

The Decision That Wasn’t Mine The day my life got small started with a sentence that sounded like a favor…

I Got A CALL From My Neighbor About A Moving Truck At My HOUSE While I Was At Work—When I Arrived…CH2

The Call My name is Meline, but everyone who’s known me since I was five calls me Maddie. The dual…

I Forgot To Tell My Wife About The Hidden Cameras I Installed, So I Decided To Just Watch…’ CH2

The Ceiling, the Stain, and the Lenses I Never Meant to Use At two in the morning the ceiling was…

My 4 year old Niece showed up at midnight with a parental rights form CH2

The Knock at 12:03 When the knock came, I thought it was a branch on the siding. The mountain does…

My Husband Kicked Me in Front of His Friends—And My Revenge Was Not What They Expected CH2

By the time the elevator eased open on the executive floor, the building had learned to be quiet around me….

The comedy star who impersonated a White House official has the Internet abuzz with the rumors she spreads along with it CH2

In the high-stakes world of politics, where every statement is analyzed and every public appearance is scrutinized, moments of levity…

End of content

No more pages to load