Part I — The Night of the Lie

Her body gave out the moment she crossed my threshold, the way a bridge finally fails after too many trucks. One second my daughter was standing in the porch light, the next she folded into me, and the world shrank to the weight in my arms. Her face was swollen in a way that made the features I had memorized at birth unfamiliar: lip split and slick, left eye purpling shut, cheek already ballooning under the skin. The smell of copper and shampoo. The tremor that ran through her like an aftershock.

“I—I fell,” she whispered through clenched teeth.

A lie should come with a different temperature. It should fog the air the way breath does in winter, reveal itself. This one arrived room-temperature, practiced, already fitted to her mouth. She shivered once, like a body that had learned to apologize without sound, and I carried her inside.

“Shoes,” I told myself, because thinking about laces was easier than thinking about ribs. I kicked them away with my heel. “Keys,” I thought next, the way you catalog small things when the big one won’t let you look at it directly. I set the keys in the bowl by the door because we needed at least one thing to be where it belonged.

“Hospital,” I said out loud, to anchor us both.

“No,” she said immediately. “I tripped. It’s stupid. I’m fine.”

She had used that voice on me when she was four and didn’t want anyone to see the scrape on her knee. She was twenty-seven now. The scrape covered half her face.

I didn’t argue. You don’t argue with someone who has been forced to rehearse. I wrapped an old high-school sweatshirt around her shoulders and got her into the car. Every jolt of the street made pain ripple through her. In the rearview, her eye fluttered shut and opened again; the left side of her mouth throbbed with its own heartbeat; at her wrist, a bruise already ripened in a shape no staircase makes.

The ER smelled like antiseptic and a thousand stories at once. We waited under fluorescent hum and a TV with the volume turned to nobody. I kept my hands open on my knees because I could not trust what they would do if I balled them into fists. A nurse called her name—a softball player with a ponytail and tired eyes—and my daughter flinched as if her name itself could bruise.

Descriptions of pain. Questions asked in a voice that did not want to scare. X-rays. A doctor who kept his expression neutral until he had to look me in the eye for the first time. I have spent a lifetime reading financial reports, watching the little numbers march under the big ones until they tell the truth. I know the face people make when they want to say “pattern” and have no right to.

“This isn’t a fall,” his silence said, and then, when he did speak, the sentences were all careful: a small fracture along the orbital rim; no need for surgery; swelling to be managed; ice; rest. “Be gentle at home,” he added to me, like I had arrived in that building with no idea what to be.

When he stepped away to tap something into a computer, the nurse leaned just slightly toward me. Not a conspiracy, not even a promise, just a human angle. “If you want to talk,” she said in a voice that had carried better grief than mine, “ask for a social worker. You don’t have to decide anything alone tonight.”

“I fell,” my daughter told the nurse before I could answer.

The nurse nodded like a person placing flowers at a grave that should not exist. “Okay,” she said. “We’ll write that down.” She looked at me again, not asking permission, exactly, but offering a future.

They sent us home at two in the morning with a sheaf of paper folded in an envelope stamped with the hospital’s name in navy letters. My daughter slept in the back seat the way toddlers do after a holiday—deep, loose, unwilling—but even in sleep she flinched when the road gathered itself under us. I watched her in the mirror, one eye open to the asphalt, the other to the thing I had avoided naming out loud.

I called him in the parking lot before the nurse wheeled her out. Her husband. The man I had toasted with whiskey and confidence the day he promised me my daughter’s life would be the thing he learned to keep. He answered on the third ring. His voice came sharp, like something used to cutting.

“She fell,” he said before I finished the second sentence, impatience coming through the speaker like meanness. “Don’t be dramatic.”

I am not a dramatic man. The closest I get is counting to ten more often than other men count to five. But something about those four words sliced something clean in me. “She fell” is what a child says when she needs you to pretend with her until she is ready to tell the truth. “Don’t be dramatic” is what an abuser says when he needs to teach the room which part it will play.

At home, I tucked her into the bed she used to climb into on Saturday mornings and pretend was a boat. She slept with her face turned away from the ceiling, the way animals do when they want to protect the soft parts. I took the hospital report out of my coat and flattened it against the kitchen counter because at least paper stays where you put it.

When the sun found the window, she woke up and the performance resumed. “I fell,” she recited, and the rehearsed line cracked as it left her. She wouldn’t look at me. Silence has dialects. Hers had learned how to answer questions before they were asked.

“All right,” I said, and made her tea she could not drink through a swollen lip. Then I did what I have always done when the answer someone gives me refuses to add up: I started checking the numbers.

Not with her. With the world around her. People tell you no and yes in ways they don’t mean when they’re only trying to survive. Paper tells you what you ask if you frame the question right. So I stopped asking and started looking.

Phone records came first. I have access to nothing I shouldn’t, but I know how to request the things you’re allowed to get when you’re paying the bill for the family plan. Calls after midnight, three nights in a row, to a number labeled “Services.” A second number that showed up twice a week between eleven and midnight. Neither one saved. I wrote them down and circled them even though it felt like the actions of a spy in a movie I had never wanted to be in.

Then bank statements. Small transfers that didn’t match the grocery store or the gas station, little drips into accounts I did not recognize, sand-colored names with no logos. I emailed the bank like a man with questions about a charge for a lawn chair he never ordered and learned enough to know money can hide in places that look like other people’s thoughts.

And then pictures—because someone is always filming the world while we’re busy pretending nobody is. The neighbor two doors down had installed a camera that showed more driveway than burglar. “Of course,” he said when I asked him for the last three weeks of history. “My wife loves your apple pie.” I took the thumb drive home like it held a second child.

In the grainy gray of the camera’s night setting, the shapes were simple as mathematics. A figure stumbling. Another shape half-familiar as movement—his car door, his hand, the blur of someone reaching for balance and finding none offered. Volume down, light up. I could see enough to make an equation.

I did not confront him. Control looks for an argument it can turn into a script and make you perform your part. I decided my rage would not be an extra in his play. I smiled when required. I shook his hand when expected. I asked after his work and let him explain it to me as if I had never balanced anything more complicated than a checkbook.

“Dad,” my daughter said at dinner two Sundays later, flinching when he reached for the salt. “He makes the mashed potatoes better than you do.” She laughed then and the sound stopped just before her eyes. His hand found her wrist under the table and squeezed there for a heartbeat too long. He smiled at me like a man who thinks being charming is the same thing as being good.

I told no one. I told everyone who needed to be told: the nurse, the doctor, the camera, the bank, the phone company. The social worker at the hospital called me at noon on a Tuesday. “I can’t discuss your daughter’s case,” she said, doing her duty. “But you should know we offer safety planning for people who… fall… a lot.” Her voice did not sharpen the word, but the ellipsis did.

At our second visit to the ER, a different doctor looked at the chart and then at me with eyes that have seen too many rehearsals. “This isn’t the first time,” he said, and the room felt smaller. He folded a copy of the injury report into my palm so quickly it could have been a handshake.

And then his arrogance did the work money had been doing: a call to the landline at my house. We keep it because the neighborhood board requires a number on file even though nobody uses it. He called in the late afternoon, before five, as if threats smelled less like threats then. He forgot himself when he forgot the machine picks up on four rings.

“If you tell your father,” his voice said, smooth as the curb had been rough when he shoved her against it, “you’ll regret it. Remember what happened last time.” Click. He hung up. I stood in my kitchen with the worst thing I had ever heard sitting under a magnet disguised as a cow. I pressed “play” again, and again after that, until his sentences could have been mine.

That night I invited them over for dinner. Steaks and a salad that looked like care. Mashed potatoes he liked to make as if cooks and husbands were both verbs you can choose. My daughter stood at the counter chopping cilantro like she could not feel the knife. When he arrived, he kissed the top of her head the way actors in old movies do before betrayal. His hand found the small of her back like someone staking a claim on a lot.

“Drink?” I asked, already pouring. “Let’s eat,” he said, reaching for the salad with his left hand and for her wrist with his right.

Halfway through, I stood and walked to the hutch where I keep the good things—porcelain, my father’s army photograph, the old tape recorder I used to capture my mother’s stories before she forgot the ends of them. I set the recorder on the table between the salt and the mashed potatoes and pressed the button. The small machine clicked and whirred and then the living room filled with his own voice.

If you tell your father, you’ll regret it. Remember what happened last time.

My daughter froze, knife in midair. A carrot roll stopped on the plate like a wheel. He had an expression I have only seen once before, in the exact second a market crashes and men realize the floor they are standing on is made of the air they had been selling.

“It’s—it’s not what it sounds like,” he stammered.

“What does it sound like?” I asked, my voice calm for the first time in months.

I slid a folder across the table like a final course: medical reports with the doctor’s careful silence pressed flat across them; bank transfers to accounts with neutral names; phone records with calls made at the hour when people who want to be caught pretend they don’t; the stills from the neighbor’s camera, my daughter’s figure, his hand, the math you can do without numbers.

“You thought she’d stay quiet,” I said, not raising my voice because silence wanted something else from me tonight. “Her silence was never yours to own.”

He reached for an excuse and found none. He reached for her and she flinched hard enough to make the chair leg scrape. He reached for me and I leaned back like a man reaching for a noose that is actually a rope.

I didn’t shout. Shouting is weather he knows how to pretend to be afraid of. I didn’t push him. Pushing is choreography he practiced when he was alone. I looked him in the eye and used the line my father used once when a man tried to sell him a business he didn’t own.

“Leave,” I said. “Tonight. Before the police see this.”

His confidence crumbled so fast it made no sound. He looked at my daughter as if she could confirm a story he had written for her. She kept her eyes on her lap. He stood, placed his napkin on the table with ridiculous care, and walked out carrying nothing.

I listened to the car back out of my driveway, the tires a little too fast, the way boys are when they need witnesses to believe they are not running.

I sat at the table a long time, the recorder quiet between the salt and the bowl of potatoes no one had touched. Upstairs, my daughter slept with the exhaustion of a person who had held the world together by pretending she could. The house made the small sounds houses make when they are trying not to be noticed.

I felt no victory. Revenge doesn’t taste like anything. I felt clarity, which is worse, and a steadiness I had not known I could grow at this age. He had tried to bury the truth under her fear, the way men have since stories learned to walk upright. He had tried to bury me under her silence. He had forgotten that I had spent a lifetime reading numbers and learning the ways they refuse to lie. He had forgotten that silence is not only something you can give; it is something you can prepare.

He taught her silence. That night, at my table, I taught him consequence.

The food went cold. The recorder cooled. I washed the dishes alone because even rituals deserve to keep their place. When I climbed the stairs to check on her, I stood in the doorway and watched her breathe. I remembered the night she was born and how the world had been loud for an hour and then finally soft. I remembered the promise I made to the ceiling then. I remembered the sentence the social worker had offered: You don’t have to decide everything alone tonight.

I did not. Morning would ask for more decisions. Court would ask for paper. People would ask for proof in rooms designed to pretend they can carry proof without breaking. Therapy would ask for words. My daughter would ask for a house that does not teach her to whisper when she is asking for water. I would ask to borrow the kind of quiet that doesn’t mean agreement.

Downstairs, the little machine sat where I had left it. I picked it up, rewound it forty seconds, and pressed play again. Not because I needed to hear him. Because I needed to hear myself not shouting while I finally did something.

Part II — What Paper Can Hold

Morning did not wait for me to be ready. It came through the blinds with its usual officiousness, spilled across the floorboards, found the recorder where I’d left it. My daughter woke with a sound like a hinge. She touched her lip before she opened her eyes and flinched when her fingers forgot and remembered at the same time.

“Coffee?” I asked from the doorway, like we were people who still knew how to start a day with small talk.

She nodded, tried to sit up, paused when her ribs argued. I looked at the bruises along her temple, the yellow beginning along the edges like surrender flags, and made myself breathe evenly.

“I have to go home,” she said when I handed her the mug.

“You are home,” I said.

Her laugh cracked. “You know what I mean.”

I did. I know the gravity of the familiar, even when the familiar is a cliff. “Not today,” I said.

Something in her face—call it a child who remembers who carried her—let my voice be the floor for a minute. “I have… a meeting,” she tried. “He’ll worry.”

“He will worry that the narrative has changed,” I said, and watched the word narrative land in the room we had always reserved for simpler vocabulary. She stared at the steam rising off the mug. “He—” She stopped. “I fell,” she said, obedient to the version that had been drilled like a fire alarm. The sentence sounded smaller in daylight.

“I know,” I said, because arguing about the past is a luxury people in safe rooms like to pretend is useful. “Today we do logistics.”

“Logistics?” The word steadied her. Work. Tasks. Boxes to tick that looked like moving forward and were also protection disguised as chores.

“First, we call the hospital social worker,” I said. “Then I call a lawyer. Then we change the locks.” I slid the folder—now thicker—with the paper we had become native to back across the table. “Later, we call the police.”

“You’re going to ruin his reputation,” she said, because the voice she had been living under wanted to keep living in the air. “You’ll make him angry.”

“He is already angry,” I said. “That is not a thing I caused. It is a thing he chooses.”

She swallowed. She put her hand on the table palm down, like she was feeling for a pulse there. “Okay.”

The social worker from the hospital picked up on the second ring. Her name was Ellen and she had the unhurried cadence of people who have learned not to gallop toward bad news lest it throw you when you arrive. “I’m glad you called,” she said, and I felt my throat tighten with a relief I had not given permission to exist.

She asked if my daughter wanted to be on speaker. “No,” my daughter said immediately, and then, after a heartbeat that looked like a decision, “Put me on.”

Ellen did not ask for a confession. She asked for a plan. “I’m sending you the safety planning document,” she said. “It’s a checklist. Alarms. Locks. An overnight bag. Copies of important documents somewhere he doesn’t know about. We’ll talk restraining order. We’ll talk advocacy.”

“Restraining order?” my daughter repeated, as if the phrase were a thing you use for other girls in a slideshow.

“Emergency protective order first,” Ellen said. “It’s a short-term wall you can build quickly. We’ll file it with the court and ask a judge to sign it today. It will forbid him from contacting you. If he violates it, it gives police a handle—they can pick it up. It tells the world which story we are in.”

“I don’t want him to get… in trouble,” my daughter whispered, because worry is a leash abusers hand whispering women as if it were jewelry.

“He is already in trouble,” Ellen said, using my sentence and a tone I wanted to store for later. “We’re asking the court to recognize it.”

She told us about an advocate named Mariah who could meet us at the courthouse, about a clerk who had a stack of forms and a pen that still had enough ink for this, about a judge who would read what we wrote and weigh it against what the world had trained him to think about people like my daughter. “If you’d like,” she added, “I can also call the police department’s domestic violence unit and request a detective meet you at your house. It can help to move in tandem.”

“Detective,” my daughter repeated, as if trying on a jacket.

“It can help to have someone whose notebook has lines,” Ellen said.

After we hung up, I changed the locks myself because I am good with my hands when given a thing they can fix. The deadbolt resisted at first, then yielded. The key turned. The sound it made was clean and analog, not unlike the click of the recorder.

I filed the paperwork for the protective order with Mariah in a hallway that smelled like hand sanitizer and old plans. My daughter sat next to me and held the pen like it had weight. “Name,” the form said. “Address,” “Describe the incident,” “Describe past incidents,” “Describe your fear,” “Do you have children?” Bureaucracy is the other language of trauma. We filled the form anyway, because the court cannot hold your story unless you put it in a shape it was designed to carry.

On the line where it asked for what we wanted a judge to do, my daughter paused. “Keep him away,” she wrote. Three words, letters careful. Then, after a second, “Let me breathe.” She looked at me like a child turning in homework that might be too much.

“It will do what it can,” Mariah said, which is the closest to honesty anyone will tell you in a hallway where hope comes stapled to paper. “He’ll be served. If he tries to contact you, call the police. Do not answer. Do not negotiate. The order is your sentence now.”

Back home, the detective stood in my living room thirty minutes after Ellen hung up. Detective Ramirez. He wore a tie that had seen too much and shoes that had seen more. He sat at my table like a person setting a tool on a bench. His notebook had lines, just like Ellen promised. He did not ask, “What did you do?” He asked, “What happened?” and then, separately, “What has happened before?” He asked, for the record, “Do you want to give a statement?” and my daughter’s mouth tried to lift the old lie.

“You can say ‘Not yet,’” he said, as if he had seen that lie become a lodging.

“Not yet,” she said, and her voice sounded like a hand leaving a rope.

He asked if he could listen to the tape. I pressed play, and the small machine did its job. The detective’s face did not change. He wrote down the words and their time stamps and then asked if we’d like a forensic nurse exam. “This isn’t about rape,” he said quickly when my daughter flinched. “It’s a separate examination we use to document injury more thoroughly than an ER sometimes does. It goes into a file the district attorney can read. Future helps cannot be built without past proof.”

“Numbers on a page,” I said, and he nodded like he had been reading the same books.

He photographed the bruises with a ruler in the frame. He photographed the stills from the neighbor’s camera. He wrote down license plates and dates and a description of a hand nobody should have to describe. He called the number that had called our house and asked nicely for a voluntary interview. He left his card on the table—a rectangle of paper that looked like a promise in a language the world still speaks.

While we waited for the order to be signed, I called a lawyer. Her name was Donna Picard and she spoke like a person who had been telling the truth for long enough that it exhausted her, but she kept telling it anyway. “We’ll file for legal separation now,” she said. “We will ask for exclusive use of the residence for your daughter so she can exhale in a room without checking the door. We’ll ask the court to enjoin him from emptying accounts, moving assets, disappearing into technicalities. We will do this with paper.”

“People will say I am… interfering,” I said.

“Good,” she replied. “Interfere with violence. That’s what the law is for.”

The protective order arrived by email at three in the afternoon with a PDF that looked like a firewall. It had a case number, the judge’s signature, boxes checked: No contact. Stay 300 feet away from the residence, workplace, vehicle. Surrender firearms. The language of safety is never as romantic as movies would like, but it is exquisite anyway. I printed three copies and taped one inside the front door.

The process server called at four. “Served him at his office,” she said. “He acted surprised.” The way she used the verb acted made me imagine that shock as a performance for witnesses and not a thing he felt. “We’ll file proof with the court.”

At six, he called anyway. Not the house phone this time. My daughter’s cell lit up with his name. She stared at it for one ring, two, three. Then she put the phone on the table between us like she was carrying a bomb and mute-screamed at me with her eyes. “Don’t,” I mouthed, and she let it ring to the emptiness that is the only place threats belong. He left a voicemail. He said if she “continued this drama,” he would tell the court she had a history of… he paused, groping for a word that would make a woman look like the problem and came up empty. “He will say you made me do it,” my daughter said in a small voice after she put the phone down.

“That is not a viable defense anymore,” I said, though I know that in rooms without lines on paper, it still is.

At midnight, the motion lights in the backyard flicked on. I was at the kitchen table reading the safety plan for the fourth time. The cat lifted its head but did not bother to pretend the world had changed. I went to the window and saw nothing. “He will test the fence,” Ellen had said. “Abusers always do. He will knock without knocking.”

At two in the morning, someone jiggled the back gate handle. The sound echoed the way small things do when the house has learned to listen. I’d installed a security camera that afternoon on the breath between calls. It caught a blurred shoulder, a hand in a suit jacket tugging on metal. I did not go outside. I called 911 with a voice that sounded like someone else’s—calm, full, boring.

“Officers are on their way,” the dispatcher said, and eighteen minutes later two men with flashlights and report pads walked the perimeter of my ordinary life and declared it intact. One officer asked if there was a protective order. “There is,” I said, and held the printed pages up like a sacrament. “Good,” he said. “Now he knows we know which side of the line he lives on.”

My daughter slept through it, which feels like both evidence and indictment.

The next morning, the forensic nurse met us in a clinic painted in reassuring colors. She had brown hair braided tight and a voice that understood what women had been taught to hate about their own bodies. She measured the bruises in millimeters, recorded locations with the patience of someone mapping a night sky. “This could be admissible,” she said, “depending on what happens next.” She slid her card into my daughter’s palm. “What happens next,” she added, “will also be healing. Trust takes longer than paperwork. Let it.”

“Let it,” my daughter repeated, as if the word permission itself could be the start of a thing.

On the way home, she asked me to stop at the grocery store for yogurt and ibuprofen and a plant she saw in the window. “I want something alive,” she said. “He hates plants.”

We bought a snake plant that does not care how often you forget it and set it in the kitchen where the light is good. After we watered it, my daughter looked at me with a face made of all her ages and said, “I’m sorry.”

“For what?” I asked, because training sometimes replaces truth.

“For not telling you,” she said. “For thinking I could be small enough he wouldn’t need to hurt me to fit me in.”

“You do not owe me confession,” I said, and my voice tried to be the floor again. “You owe yourself a different story.”

“I taught myself to be quiet,” she said.

“He taught you,” I corrected gently.

She thought about that. “You taught him consequence,” she said, and we both looked at the plant as if it were listening.

Two days later, a station wagon idled across the street at noon. It was his—leased, polished, pretending harmlessness with a car seat in back nobody had the right to strap in. He rolled down the window and stared at the house with the face of a man who still believed ownership and guarantees were synonyms. The protective order on the inside of my door was not an incantation that could stop him from driving on asphalt. It was, however, an incantation the police understood when I called and said, “He is within my world again.”

“Do not go outside,” the operator said kindly. “The order will do that for you.”

This time, he did not leave when the patrol car pulled behind him. He got out, used the posture of a man about to deliver a sermon on the street, and declared to the officer that his wife had gone crazy. He gestured at my house like it had offended him by becoming a person. The officer stood with his hands on his duty belt and let my neighbor’s camera do the work of testimony. He told him about the 300-foot line the judge had drawn on paper. He told him about contempt. He used words like violation and custodial risk as if he were handing out vocabulary cards for a class the man had failed to attend.

The officer took a report. He wrote a number down on a pad. He drove away and the station wagon followed. The camera watched the rectangle of street become itself again. I exhaled a piece of air I had apparently been hoarding since the night he called my landline and forgot that machines record the words people try to put back in their mouths.

In the quiet after, my daughter scrolled aimlessly and landed on a calendar someone else had set once. “Our anniversary is Monday,” she said. “It would have been.” She laughed without any pleasure in it. “We had reservations,” she added, because humiliation becomes absurd when it runs out of places to go.

“We’ll order in,” I said, and she rolled her eyes but put a hand on the plant like a girl making friends.

That night, when I went to my room, there was a message on my pillow. My daughter’s handwriting had always leaned forward like a person trying to hear a quiet secret. She had written three sentences:

He taught me silence.

You taught me consequence.

I am learning my own voice.

Underneath, she had drawn a line and written two words twice: thank you. sorry. I ran my finger under the words like a child learning to read and said out loud, to the ceiling and the quiet and the shape of my father in the way I stand: “I forgive you. I forgive me less quickly, but I am learning.”

I went downstairs and pressed play on the recorder one more time, not because I needed proof of what I had heard, but because I needed to practice hearing something and not shouting in response.

Then, for the first time since that night on the porch, I slept.

The call came a week later from the district attorney’s office. A woman named Patel with a voice like an anchor asked if my daughter would be willing to come in for an interview. “We have enough to file charges,” she said. “The recording, the forensic report, the violations. If she gives a voluntary statement, it helps us build the pattern. If she can’t yet, we can file anyway. The decision belongs to her. I want her to know what decisions are hers again.”

“She’s… learning,” I said, and heard the gratitude in my own words.

When I told my daughter, she looked at me for a long time, the way she used to when she was five and deciding whether the playground was worth a skinned knee. “Will you come?” she asked.

“Yes,” I said.

She nodded. “Okay,” she said. “I want him to know I am not afraid of rooms anymore.”

We went together. The DA’s office had chairs that did not look like punishment. The detective was there with his lined notebook. The advocate sat quietly with a pen she never used. My daughter told the truth in a voice that seemed surprised to find itself in her mouth. She did not add adjectives. She did not fill silence with excuses. She said what happened. She said what happened again. She recognized the difference between her voice and his.

After, back in the car, she stared at her hands. “My wedding dress is still in his closet,” she said suddenly, and laughed. “I’ll never get the deposit back.”

“I’ll buy you pie,” I said. “Pie holds a lot of grief.”

At home, we ate pie standing up. The plant in the kitchen looked like the only one of us unfazed by the day. She watered it and said, “He hates plants,” again, and this time her voice had a tone I recognized from when she was small and learned that she could ride a bicycle fast without anyone’s hand on the seat.

“He can hate whatever he wants,” I said. “He doesn’t water things.”

The court date arrived on a paper rectangle with a seal. In another life, I would have thought “arraignment” sounded like a fancy bow. Now I know it is when the state turns to the person who hurt your child and says, “We see you.” My daughter sat on a bench with her back straight. He kept his eyes on the floor. His attorney whispered in his ear. The judge spoke words that sounded like scaffolding: no-contact order continued, surrender firearms within 24 hours, check-ins. He set a hearing for a longer order later. Dates. Times. Nouns.

We walked out. The sky was too blue. On the steps, my daughter leaned into me in the way she did when she was two and the world was too tall. “I am angry,” she said into my jacket.

“Good,” I said. “Let it be more than fear.”

“Will you ever forgive him?” she asked.

“No,” I said. “That’s a thing I will not do this life.”

“Will I?” she asked after a breath.

“That’s not for me to say,” I answered. “You’re allowed not to. You’re allowed to forgive yourself first.”

She nodded. “That sounds like a thing Ellen will say in more expensive words,” she said, and I laughed because laughter is not treason when the sun is out and the recorder is quiet.

I drove her home—my home—where the locks clicked the way they learned. The plant sat in its spot like a flag. She touched it in passing, the way you pat a dog. Upstairs, she fell asleep on top of the covers with the court paper under her hand. I went to the kitchen and made a list of things that needed doing: call Donna; forward Detective Ramirez the video of the gate; grocery run; print copies of the order for her wallet; install a second motion light. At the bottom, I wrote sit for five minutes without moving and checked it off after I did it badly.

That night, for the first time, she told me a story about the first time he grabbed her. On the landing. After a party where she had tried to be easy because easy keeps men from being dangerous. “I thought if I didn’t make trouble,” she said, “the trouble would pass me by. He grabbed my wrist and I felt like I had been introduced to a part of the world nobody had warned me about.” She looked at me as if I might say I had failed the warning. I did not.

“You survived the introductions they never should have made,” I said. “Now you get to write the rest. I will carry the papers in the rooms where paper matters.”

She exhaled. “He taught me silence,” she said again, but this time I heard an “until.”

“Yes,” I said, and reached for the recorder. I opened the battery compartment. I slid the batteries out. I placed the machine in the drawer by the stove next to the takeout menus and the scissors and the twine. “We’ll keep it,” I said. “We just won’t worship it.”

She laughed the smallest laugh. “Okay,” she said. “Okay.”

Down the street, somebody’s motion light clicked on and then off. Inside our house, the plant turned toward the window the way plants do, which looks like bowing until you remember it’s reaching.

Part III — The Long Work

A case is not a moment. It is hours braided into weeks braided into a calendar you didn’t ask to keep. The law moves like furniture—heavy, necessary, occasionally elegant if you squint.

We learned new rooms. In one, Assistant District Attorney Patel sat with a legal pad and a patience that made me wish I had known her when numbers first tried to lie to me. “We build patterns,” she said. “He will try to call this an incident. Incidents are lies that forgot their birthdays.” She asked my daughter to tell the same story three ways—chronological, sensory, then only the part with the bruise on the wrist. “Juries are a roomful of strangers with their own ghosts,” she said. “They need both maps and street-level directions.”

In another room, Donna—my daughter’s divorce attorney—made lists without raising her voice. “We file for exclusive occupancy,” she said. “We ask the court for a ten-year order of protection that mirrors the criminal one. We freeze joint accounts pending equitable distribution. We request temporary support while you sort the pieces. We set a status conference for the end of the month. We bring everything to the judge like a child bringing a broken toy and asking a grown-up to try.”

My daughter attended therapy with a woman named Sheridan who kept tissues in places that did not humiliate you. “We stack safeties,” Sheridan said. “Locks. Plans. People who answer phones. Words you can say. Your body tells on you when your mouth won’t. Let’s teach your mouth to keep up.”

I went to a support group once. For fathers, for brothers, for the people who love the people who learned silence. It met in a church basement that had seen too many casseroles and not enough apologies. Men spoke without competing for pain. One man said, “I want to put my hands around the throat of the boy who taught my daughter to whisper.” Another said, “Me too,” and then his silence did more than his rage would have.

The neighbor printed larger versions of the stills from his camera and brought them over in a manila envelope. “For Patel,” he said, almost shy. “We should have bought a better one,” his wife said, and the apology she aimed as a joke nearly broke me. “You caught enough,” I said. “You caught enough.”

Two weeks after the arraignment, the station wagon returned. This time it came at noon on a Tuesday and parked half a block down, like a child playing hide-and-seek who doesn’t understand lines of sight. He sat there for long enough that the heat waves made the hood look like water. Then he got out and walked down the sidewalk holding a paper bag as if delivery men were absolved of distance.

He stopped at the mailbox and took our mail as if paper belonged to him. He flicked through the envelopes looking for something with a seal on it. He looked up at the window at the same time I looked out. We saw each other. He raised the paper bag in a little shrug. He didn’t think I would call because good men don’t tell. He forgot I was done performing.

When Detective Ramirez arrived, he stood on the sidewalk and spoke in verbs that belonged in reports. “Served.” “Stolen.” “Violated.” The officer with him wrote June 14 on a line. Paper loves dates. The detective looked at my daughter and said, “Do you want to swear out a complaint?” Her mouth did the old thing and then the new thing won. “Yes,” she said. His pen moved.

That night an email arrived from an address with his name in it and a nine-digit number as if he thought arithmetic could disguise intent. “I miss you,” it said, and then, in the sentence every abuser uses when they want the room to believe it’s helping, “Let’s handle this privately like adults.” My daughter forwarded it to Patel and deleted it. We learned not to collect poison for art.

He pushed on other edges. A drone hovered above the backyard once and my daughter went inside and closed the blinds. Two days later, a florist called to confirm an order for an arrangement I hadn’t placed. “White lilies,” the woman said. “For sympathy.” The order had my daughter’s name on it and his credit card number. When I told Detective Ramirez, he sighed the sound of men who carry other people’s wreckage for a living and added a line to the file called harassment.

The day after that, a man I didn’t recognize tried to talk to my daughter in the grocery store. “He says he’s sorry,” the stranger said, soft. “He misses her. He can change.” My daughter looked at the stranger’s lanyard—employee badge from a place that sells electronics—and then at his hands, then at me, then at the avocados. “Tell him the protective order doesn’t recognize oaths,” she said. We abandoned the cart and went home. She emailed Patel the time and aisle number like it was a meeting.

Patel called that afternoon. “He’s escalating,” she said. “We’re filing a motion to revoke bail. The violations make it easy.” Easy is a word that does not belong in this story, but I accepted it like a chocolate on a pillow in a cheap hotel. He was arrested at his office two days later. A picture appeared online—grainy, off-center, taken by a man who sells toner on the fourth floor. The caption said more than the image: The suit didn’t save him.

I saw him once. In the courthouse parking lot. Not because I wanted to. Because the world is small. He came around a row of cars and the shape of him pressed on the air. He looked older than thirty-two and younger than his choices. His eyes did not know where to land. He saw me. Anger did the cheap trick it always does—tried to make me perform.

“What do you think you’ve done?” he started, and I held up my hand. I did not put my finger in his chest. I did not list the things I had collected. I said, evenly, the only sentence I wanted the parking lot to remember: “I counted.” Then I walked to my car and drove away at the speed limit.

When the phone rang that night, I recognized his new place as “unknown caller.” I let it go to the recorded woman who belongs to all phones. He left a message for my daughter telling her he forgave her, which is the strangest thing men like him do. He said he wished her the best. He said he would “pray on it.” He said God had a plan for brokenness. He did not say he was sorry. We added the message to the file and did not listen to it twice.

The safety plan moved from the table to the refrigerator. The plant in the kitchen leaned toward the window as if it had always believed in sunlight. My daughter started watering more than it needed. “Overwatering is a kind of worry,” Sheridan told her. “It’s hard to learn the right amount of care after someone has tried to drown you.”

She made a new friend in group—Tania, a nurse who put both hands on the table when she talked. They went for walks at the track behind the high school and counted laps. “Seven,” my daughter texted me one day as if laps were another kind of paper. “No panic at the corner.”

She bought a lamp because she liked the way the shade made the room warm. She bought a new toothbrush because some things deserve to be replaced even if they still work. She slept in my house without waking up when the neighbor’s cat knocked over a planter and the motion lights went on like a show.

Donna called with the first good piece of news that did not need to be worried at before it stuck. “The judge granted exclusive occupancy,” she said. “He cannot return to the marital residence.” Marital. It is a word that tastes like legal paper and cake. “Pack his things with a witness,” she added. “We’ll coordinate with the police for a civil standby. You get to keep the house while we sort the math.”

We boxed his life into labeled squares the way you pack a problem when you’ve decided to stop living inside it. Shirts. Books. Chargers. A framed diploma that looked smaller without its wall. My daughter’s wedding dress hung inside plastic like a sentence in a play nobody wanted to perform. “Donate it?” she asked, not unkindly. “Someone else can have a white promise that comes true.” We took it to a thrift store that benefits a shelter. The woman behind the counter smiled like she understood exactly which ghosts come folded in garment bags.

Of the things he left in the night he walked out, only the tie on the bedroom doorknob confused me until my daughter laughed. “It was never kinky,” she said, voice dry for the first time in months. “He just never learned how to hang things back up.”

Patel sent us a subpoena schedule on a Friday: forensic nurse Monday, neighbor Wednesday, me Thursday. “You can’t be in the room for each other,” she said. “But I’ll tell you how it went afterwards.” She wore her hair up that day. People tell you they are prepared in ways they don’t mean to.

The forensic nurse spoke first about millimeters and locations and color changes over time. The neighbor spoke about cameras and angles and how he wished he’d had a better lens. “You caught enough,” Patel told him, and the way he straightened his shoulders made me want to bake him a pie. I spoke last. I kept my words to nouns: phone calls, recordings, the night at the table when I pressed play; the hospital report that had been folded in my coat; the plant on the kitchen counter on purpose.

The defense tried old tricks. “Isn’t it true your daughter is… emotional?” the lawyer asked the nurse, as if tears change bone. “Isn’t it true she sometimes bruises easily?” he asked the neighbor, as if skin is evidence of guilt. “Isn’t it true you don’t like him?” he asked me.

“I liked him fine when he pretended to be someone he isn’t,” I said, and the judge pretended not to smile.

At a pre-trial hearing, his attorney floated a plea deal like a lifeboat with holes. “Misdemeanor assault,” he said. “Anger management classes. Six months probation.” Patel said no. “We don’t trade felonies for feelings,” she said. “He left handprints.” The judge set a trial date and I bought a tie because some wars are fought in clothes you don’t mind sweating in.

The week before trial, he wrote a letter. Donna opened it at her desk and then forwarded it without commentary. He called his behavior “unfortunate.” He used the phrase “to the best of my recollection” about things that were not memory but muscle. He invoked his childhood. He invoked God. He did not invoke my daughter’s name. I printed it and put it in the file and resisted feeding it to the plant.

The night before his lawyer was to pick a jury, he changed his plea. The risk, he later told a judge, had become too great. He pled guilty to felony assault and misdemeanor criminal contempt for violating the order. The judge asked the questions that make a plea stick to ribs: “Did you do this?” “Are you pleading of your own free will?” “Has anyone coerced you?” He said yes to the ones he needed to and no to the ones he should, and then the court spoke the sentence he would live inside instead of ours.

Two to four years upstate. Five years of post-release supervision. Ten-year order of protection concurrent with the criminal and family courts’. Surrender of firearms. Completion of a batterer intervention program if parole wanted him to be eligible for sunlight sooner.

He looked back only once—instinct, not apology—and his face met the back of a room that had stopped being his. The bailiff put a hand on his elbow politely, the way men put hands on other men when they will now decide where they go.

Outside, my daughter sat on the bench and shook. Relief is a species of earthquake.

“I thought trial would be a better story,” she said, almost ashamed.

“Pleading guilty is a better ending,” I said. “It’s just not cinematic.”

“We don’t need a movie,” she said. “We need a calendar.”

We bought lunch at a deli that puts too much mustard on everything. We ate in the car with the windows down because air is free when it wants to be. She wiped her mouth with a napkin and looked at me the way she did when she was eight and asked whether people can die of embarrassment. “Do you still hate him?” she asked.

“Yes,” I said. “And I am fine with that.”

“I don’t know if I do,” she said. “I thought I did. Maybe I hate the gravity that made me orbit him. Is that different?”

“It is,” I said. “Hate the gravity. It never apologizes.”

She exhaled, a sound with edges. “Okay,” she said. “Okay.”

Back at the house, the plant had unfurled a leaf. It was a ridiculous thing to notice on the day a man learned the inside of a cell. It was also exactly the thing to notice. She touched it. “You’re dramatic,” she told it, gentle. “You’re allowed.”

That evening, for the first time since I picked up a recorder and made it say what people had been pretending not to hear, we ate dinner and left the dishes in the sink. We sat on the couch and watched a show about people building houses they will eventually sell to other people who will pretend they don’t want the life in the brochure. The clock ticked. The motion lights stayed off. At ten, my daughter leaned her head on my shoulder and fell asleep with her mouth open. I sat very still and let the weight of her do what it needed to.

You expect victory to taste like triumph. It tastes like water. It tastes like not checking the door every eight minutes. It tastes like the absence of a car parked at the curb with the engine running.

I put the recorder away in the drawer with the scissors and the twine. We had learned what silence could do as a weapon. We were practicing what it could do as a room.

Part IV — The Clear Ending

As with all stories that are true, the ending did not arrive with trumpets. It came with Tuesdays. It came with forms. It came with the way the plant insisted on living and then did so, boldly, as if that had been the plan all along.

The divorce finalized in a courtroom with a stiff flag and a clerk who had seen too much to be moved. Donna slid me a copy of the order that called my daughter’s house her residence, his name removed from the deed. “Equitable distribution,” the judge said, making arithmetic with a gavel. Retirement accounts were divided like sums that had forgotten they once added up to a promise. My daughter kept the car he always hated for being practical. He kept the images he had placed on shelves as if aesthetics were character.

At the family court, a different judge extended the order of protection to ten years and coordinated it with the criminal order so that one system didn’t make a hole where the other one thought it had put a wall. “No contact,” he said again. The phrase had become a benediction. The paper—two pages stapled—said what no poem would have.

He wrote once from prison. He called himself humbled by his circumstances. He underlined Bible verses in a way that made me wish God charged rent. He said he wished my daughter healing, as if he were a priest. He did not ask for forgiveness. We did not reply. Donna sent the letter to Patel. Patel sent it to a file. The plant leaned toward the window in a show of solidarity.

My daughter found a job. She had been a project manager before her life became managing a man’s project. She took a position at a small nonprofit that teaches high-school girls to fix things other people shouldn’t have broken—leaky faucets, bike chains, a cabinet door that refuses to sit right on its hinge. She came home with knuckles scuffed and a grin that had a shape I had not seen since she fell off her bike at seven and stood up bloody and alive. “One kid said ‘lefty-loosy, righty-tighty’ like a mantra,” she laughed. “I told her it works for jars and also the rest of your life.”

On Wednesdays, she went to group and sat in a circle that had learned to keep its own weather. On Fridays, she watered the plant with exactness. On Sundays, she learned to bake pie crusts that did not crack with Margaret. They spoke about butter and control like the same thing under different names. Sometimes they spoke about nothing. Silence keeps its own ledger.

We replaced the front door because the neighbor recommended it and I decided to let people recommend things again. The new one made a different click. I kept the old lock in a drawer because some talismans you earn. We left motion lights on and then forgot to notice them. We ate spaghetti with the volume turned down because Isa had been right; quiet spaghetti is a sound that means you are alive.

In late spring, the DA’s office sent a letter about a parole hearing scheduled for the end of summer. Patel called first. “I’ll appear,” she said. “You can send a statement if you like. You do not need to be in any room he can breathe in.” My daughter sat at the kitchen table and wrote a page and a half with the gravity of a person signing a treaty. She did not curse. She did not call him names. She wrote: I am not your narrative. I am not your silence. I am not your consequence, either. I am my own voice. She wrote: Do not bring him back to my neighborhood where my body learned fear. She wrote: I am not afraid of rooms anymore. I just don’t want to waste them.

Patel read the statement into the record standing at a table behind a partition next to a man who had carried our papers for months. The board declined parole that year. They cited “pattern of violence,” “violations,” and, in a surprise that made me consider writing a thank-you note to bureaucracy, “impact on survivor.” You cannot build your life on courts, but you can breathe a little easier when they hand you air.

We drove north in July and stood by a lake that had always that summer belonged to somebody else’s photographs. My daughter swam for the first time in two years. She said the water made her feel like calendars were small. When she came out, her hair flattened against her head and the world looked exactly like it should: sun, wind, humans, no watcher in a car making ownership noises under his breath.

On the way home, she said, “I don’t think I hate him,” and I did not lecture. “I think I hate that I spent so long narrating myself for someone else’s story,” she added. “That hatred is heavy. I might put it down.”

“You get to decide what you carry,” I said. “The scar stays anyway. The wound is closed. They’re different.”

She looked out the window at the trees turning light into confetti. “I am not healed,” she said. “I am healing.”

“Me too,” I said, because some truths are a chorus and not a solo.

We planted things. Literally, because that is how stories insist on their metaphors. A hydrangea that refused to pretend it didn’t want to be blue. A row of cherry tomatoes that made our thumbs smell like July. Sunflowers that became a joke—we measured them each week against a yardstick like they were cousins visiting from out of town. My daughter took pictures of nothing—the space in a room sunlight makes when it decides to sit down. She hung one by the door, framed. She said it made the house tell the truth to itself.

When the first anniversary of The Night arrived, we did not make a cake for it. We took the recorder out of the drawer and put it on the table between the salt and the plant and then we did not press play. We poured coffee. We wrote two lists that were not ballads. The first said: What We Built—locks, friends who show up when you say come, a habit of checking the stove, recipes that do not hurt, a file full of paper we no longer have to carry around everywhere we go. The second said: What We Let Go—arguments we were rehearsing, the feeling that we could have rewound to the night before the porch, hope that a man would apologize and look like he meant it, the need to win rooms.

“You know,” my daughter said, touching the recorder like a pet you do not want to startle, “if you had shouted that night, I would have had to keep protecting him. I would have had to choose his embarrassment over my fear.”

“I was afraid of your choice,” I said. “That’s why I chose silence.”

“It was the only time silence wasn’t the cage,” she said.

We hugged in the awkward way people do when they are learning that their bodies can hold weight without adding more. The plant had another new leaf and we laughed at it because it insisted on details.

Sometimes, on bad days, the old weather tries to return. The light outside my bedroom window bends wrong and my heart does math. A car idling two streets over makes me count. My daughter stands at the sink and stares at a fork as if it has become a weapon in a story she has to decide to turn back into a utensil. On those days, Sheridan has her make a list of five things that are not dangerous and three that are for future reference and are also under control. Toaster. Brick buried under leaves at the park. The way the neighbor says hello too close. “Then pet the plant,” Sheridan says. “Because it is arrogant and it makes air.”

There are graduations to healing. Paper first. Then locks. Then laughing at a leaf. Eventually, friends at a table who do not need to rehearse their concern. Eventually, kitchens where you share recipes that have nothing to do with survival. Eventually, a voice that can tell a story without apologizing to the room for being the subject. Not forgiveness. Not forgetting. Just expectancy that isn’t ruined by evidence.

On the last day of summer—before the parole board wrote denied on a line and the court wrote converted to permanent on an order and the plant decided we had earned another leaf—my daughter made spaghetti and did not ask me to listen at the door while the water boiled. I sat at the table and read the paper like a person the house trusted. She set the bowl down softly. The sound it made is the sound I will remember when I can’t remember any of this: a gentle landing.

I picked up my fork. She picked up hers. We ate in a room that did not require performance or prophecy. After a while—not dramatic, not a climax, just a sentence that arrived when it wanted—she said, “He taught me silence. You taught him consequence.”

She twirled pasta. I put my fork down and waited.

“I taught myself,” she added, the smallest smile, “a voice.”

I raised my glass of water because it was the only toast necessary. Outside, somebody’s motion light flicked on then off because the world still has cats, and the plant leaned toward the window like a hand raised in attendance.

That night, after we washed the plates and turned the deadbolt and put the recorder back in the drawer without ceremony, I went to my room and wrote the last line of this story on a piece of paper I did not intend to file. I folded it and slid it under the plant.

The truth is this: my daughter is healing; I am scar and steady; he is consequence. There is no victory in any of it. Only clarity. The lock turns. The calendar fills. The house is quiet. And the quiet means peace.

News

His wife said, “I regret marrying my husband, I should have chosen his friend instead,” What He Did… CH2

Part I — The Sentence That Changed the Room Kennedy didn’t mean to hear it. He wasn’t snooping, not then,…

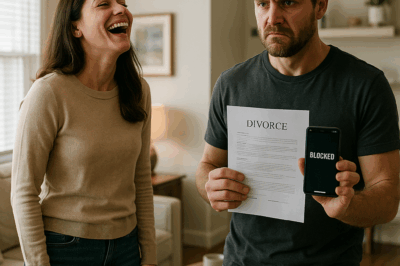

I Laughed That Some Of His Friends Tried Me—Now He’s Filing Papers And Blocking Me CH2

Part I Rowan spends the entire Sunday dinner being a cathedral. By the time Margaret sets the roast down and…

My daughter shaving her sister’s head before prom was the best thing she ever did. CH2

Part I You never think the sound of clippers will be the sound that saves your child. It started as…

Husband Has Baby with Sister, Dumps Me ➡ 3 Years Later, Surprise Meeting, Ex’s Shocked Face. CH2

Part I If you’d asked me to name the moment my marriage cracked, I’d say it wasn’t big. Not the…

Sister-in-law happy at funeral because my surgeon brother left her lots of money. CH2

Part I The day we buried my brother, the sun came out like it had been paid to. It turned…

“We Left My Stupid Husband Miles AWAY From Home as a JOKE, But When He Returned It Was NOT Funny…” CH2

Part I I can tell you the exact moment I should have trusted my gut. It wasn’t the tight smile…

End of content

No more pages to load