Part I

Antiseptic burns in a way that feels righteous. It bites the skin as if scolding flesh for failing to stay intact. I remember that sting. I remember the fluorescent light that made everything look like copy paper and the metallic echo of a curtain ring hooking along its rail. Mostly I remember my father’s voice on speaker, tinny and impatient over the noise of the emergency department.

“Are you dying?” he said. “Because Clare just bombed an interview and she’s spiraling. She needs me right now. Don’t call me in a panic.”

Then the line went dead.

A nurse with freckles sprinkled across her nose like powdered sugar glanced up at me as if to say: you heard it, I heard it. She tightened the blood pressure cuff one more notch and hit a button. Numbers bloomed green on a screen. “Toes?” she asked, nodding toward the bulky temporary splint they’d wrapped from my shin to mid-foot. “Can you feel me pressing?”

“A little,” I said. It was true. Nerves fired like distant fireworks—there but barely.

“Good,” she murmured, more to her chart than to me. “Doctor’s on his way. We’re fast-tracking you to CT.”

The accident itself was a blur of math and metal. Red light, right-of-way, someone’s text message winning a small war over their attention on the other street. The screech. The sideways slide. The strange moment of weightlessness just before impact when time held its breath as if it could negotiate. Then glass was glittering in the air and the steering wheel was a fist against my ribs and my left leg lit up with such white-hot pain that the world went quiet around it.

Paramedics had disciplined compassion, the kind you can trust. One of them—Darnell, according to the tape on his vest—kept a hand on my shoulder and his voice in my ear all the way to the hospital. “Stay with me, Stella. You’re doing great.” A statement, not a compliment. Facts are steadier than praise when you’re counting breaths.

I knew too much and too little at once. I’m not a doctor, but I’ve been the adult daughter filling out intake forms in enough ERs to recognize the cadence: questions stacked like towels, signatures multiplied, the slippery feeling of consent when what you’re consenting to is being carried by other people’s competence. I kept my eyes on the light above me to avoid looking at the blood on my shirt. The light didn’t flinch.

When the nurse stepped away to grab what I assumed was IV tubing, I reached for my phone. The screen spiderwebbed but still woke up, a small mercy. “Emergency contact?” it asked. My thumb hovered and then moved out of habit more than thought. Dad. A call button. Voicemail. Try again. Ring. Nothing. Third time, charm. A pickup and a sigh.

“Stella, what. Clare’s—” Papers shuffling. A muffled voice in the background. “I have my hands full here.”

“I’m at County General. I was in a car accident,” I said. Words felt like they had to earn their place. “My leg—there’s a fracture. They’re saying possible internal—”

“Okay, okay,” he cut in. “Are you dying? If you’re not, do not do this to me right now. She’s fragile. You know how she gets.”

“I’m alone,” I whispered, because that seemed like the one non-negotiable fact to put on the table.

“You’re strong,” he said, in the tone people use when they’re actually saying you’re inconvenient. “You’ll be fine. Don’t call me unless it’s… unless it’s life or death.”

“Dad—”

“Text me updates,” he said. Then nothing. Then the tiny hollow sound a call makes when it ends without a goodbye.

The worst part wasn’t the rejection. It was its familiarity—like my body recognized a pattern and loosened to fit it. I lay there under government-grade lighting and thought of every time that exact hierarchy had quietly arranged our family. Clare first. Clare the sensitive one. Clare the delicate creative—the soul, Dad had said, with an awe that tasted like sugar. Clare who cried pretty, who overwhelmed easily, who moved through rooms like weather. Me? “You’re stable, Stel,” he would say, the way people praise furniture for holding up a sagging bookshelf.

Birthdays told the story if nothing else did: mine a quiet dinner with store-bought cake and Dad’s hand landing on my shoulder in a perfunctory pat; Clare’s a backyard Jupiter of fairy lights and an ostentatious three-tier cake that leaned and made everyone love it more for the imperfection. At my high school graduation, he missed the ceremony to sit with Clare because a class grade had tipped from A to B+ and her sky was falling. “You understand,” he’d said, which was the permission slip to overlook me he’d been forging my whole life.

I used to believe that made me noble. The easy kid. Independent, resourceful, low maintenance—words that sound like compliments until you realize they’re financial products: high yield for the investor who never checks the account until they want a withdrawal. When I took on two jobs in college to cover tuition shortfalls, he sent Clare rent money and bought her a new laptop because “hers makes her anxious.” When my keys stuck in the ignition of my fifteen-year-old sedan every other week, he suggested I YouTube it. “You’ve got this,” he’d text, using encouragement like a trapdoor.

The nurse returned. “Deep breath,” she said gently, and advanced the IV catheter with the kind of confidence that makes people forgive you for needles. Warmth crept up my arm, dizziness slipped in behind it. Then I was rolling—doors, tiles, ceiling tiles arranged like graph paper, numbers scrawled in marker near the edges: maintenance notes, I guessed. The CT scanner was a mouth; I let it swallow me.

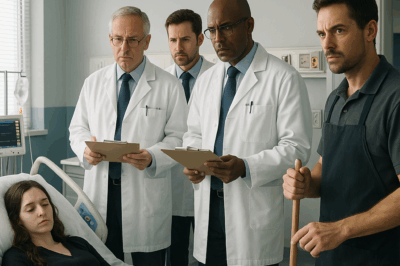

Back in the bay, they did the medical version of tucking me in: vitals cycling, pain meds, a blanket pulled up, a hand on the rail. “Orthopedics will be down,” someone promised, which in hospital time means anything from ten minutes to never. I stared at the curtain’s fabric, the repeating pattern of pale green squares trying to hypnotize me into believing I was part of a system. I was part of a system. I’d just mistaken which one.

My phone was a cracked moon on the tray beside me. I turned it over as if that could hide it from me. Then I turned it back and scrolled past “Dad” and past “Clare” and stopped at a name that didn’t carry history like a rusted anchor: Eliza Grant.

We’d met when a landlord tried to keep my deposit on a technicality so flimsy it should have been printed on tissue paper. Eliza had dismantled him with three emails and two laws I didn’t know existed. She was sharp without hurrying and kind without performing. I’d saved her number the way you save a fire extinguisher: unlikely to need, powerful to have.

She picked up on the second ring. “Grant Law.”

“It’s Stella,” I said, and surprised myself by not crying. “I’m at County. Car accident. I’m okay—mostly. But I need… help.”

“Are you safe?” she asked first, which calibrated the room correctly. “Is someone with you?”

“I’m safe,” I said. “I’m… not with anyone.”

“Tell me what you need.”

“I want to make it so they can’t take from me anymore,” I said, and the words were a key turning in a lock. “Financially, legally. Everything I’ve ever given them access to—I want it revoked, changed, guarded. Power of attorney, beneficiaries. Bank access. All of it.”

She didn’t say wow. She didn’t ask why now. “Do you have documentation of what you’ve already provided?” she asked instead.

“Yes.” The answer surprised us both. Over the last year, I’d quietly started saving evidence in a folder on my laptop: bank transfers for “one month of Clare’s rent” or “Dad’s co-pay this time,” Venmo screenshots with emojis meant to make money cute, emails from Dad with subject lines like “Quick favor” and content lines like “Clare’s phone broke again, can you…?” I hadn’t known why I was collecting it. Maybe the part of me that can’t not be prepared had finally stopped waiting for permission from the part that still wanted to be loved for being useful.

“Good,” Eliza said. “Don’t move anything tonight. Rest. I’ll be at the hospital in the morning. We’ll get your signatures and I’ll start notifications. You don’t have to do this alone.”

She said it like a fact, not a mercy, which is how you talk to people who’ve built their lives on quiet competence. When the call ended, the room didn’t feel bigger. It felt correctly sized. Dizziness lifted like someone had walked to the wall and turned down the dimmer switch. The nurse returned with a grin and a syringe. “Pain meds time,” she said, cheerful like Santa.

“Bless you,” I said, and meant it with a fervor I don’t usually commit to strangers.

Night in the trauma wing is louder than daytime but somehow gentler. Machines beep with less insistence. Shoes squeak in the hall like apologies. The curtain shivered when staff passed by like a horse breathing. I learned the bed adjacent to mine belonged to an older man who narrated everything as if a grandson were at the foot of his bed taking notes. “Well, see,” he told someone, “that there is my appendix scar.” Hospitals turn private life inside out; our bodies become family albums for second shifts.

Sometime after two, an orthopedist came in and spoke in a pleasant monotone about tibial fractures and plates and how they’d fix me. He asked how I’d gotten here. I said, “A distracted driver,” and did not specify which one. He asked if I had someone to drive me home when they discharged me. The pause after my “yes” was the length of a sigh.

By morning, the pain was dull enough to be a background singer instead of the headliner. Eliza appeared at nine a.m. like an emissary from a saner planet: navy suit, low heels, hair pulled back not because she was trying to intimidate but because she wanted no nonsense in her face while she worked. She moved a rolling table closer to my bed and opened her laptop. “Morning, Stella,” she said, the corners of her mouth lifting. “Let’s get your life back.”

I handed her my phone and the cheap thumb drive I’d told the admitting clerk was “essential valuables.” On it: months of quiet math. The list made me wince even as fingers moved: $300 here “just until Friday,” $600 there “so she’s not embarrassed,” $1,000 for “damage to Dad’s bumper” after Clare’s backing incident was renamed a “learning experience.” Notes line up with transfers like choreography.

Eliza built a spreadsheet with a surgeon’s economy. The total at the bottom looked like a down payment, like a year of grad school, like the safety net I’d thought I didn’t deserve. She didn’t say “why would you do this.” She said, “This is a dependency pattern. The language in these messages—” She tapped one where Dad had written, You know you’re the strong one. “—is emotional coercion in a friendly tone. We can’t retroactively bill them for your love, but we can stop the bleeding.”

We went through the checklist as if triaging a different kind of trauma. Revocation of the general power of attorney I’d signed on a day when Dad had called it “just in case.” Removal of both him and Clare as beneficiaries on life insurance and retirement accounts. Changing contact information at banks. New passwords and a passphrase that would make a hacker cry. Healthcare proxy updates. “Your emergency contact?” Eliza said.

I looked at the line like it was a riddle. “This is pathetic,” I said, attempting a laugh that didn’t quite land. “I don’t have a bench.”

Eliza looked at me for a calibrated second. “You know a lot of competent people,” she said. “Pick the one who shows up without you asking. It doesn’t have to be forever. It just has to be now.”

“Jules,” I said, surprising myself with the answer. My cousin who messages me memes at two a.m. and remembers my coffee order from when we were twelve and mall-food counted as cuisine. I typed her name and watched it become official in a way that felt less like betrayal and more like relief.

We notarized what we could with a tablet and a stylus and a nurse witness named Teresa who said, “Honey, my favorite part of this job is getting to hurt men with paperwork.” Then Eliza popped open a crisp folder and slid in copies. “I’ll file the rest this afternoon,” she said, standing. “I’ll also send formal notice to your father and sister. Assume they’ll come in hot. Do not engage. Forward anything to me.”

“Clean and boring,” I said, repeating a mantra she’d once used about leases and now about lives.

She smiled. “Boring saves money.”

They came at 4:47 p.m., because of course they did—late enough to be dramatic, early enough to catch me between Dilaudid naps. Dad entered first, loosened tie, concern arranged on his face like a table setting. Clare followed, oversized sunglasses perched on her head like a headband, jaw set to Wounded Artist. Their eyes hit Eliza like a hand on a hot pan.

“Who is this?” Dad demanded, already mastering the indignation of a man who believes he’s owed explanations.

“My attorney,” I said, sitting up slow and discovering that pain has opinions about leverage. “You can sit if you want to talk. Or you can leave.”

Clare barked a laugh. “An attorney? Dramatic much?”

“Clare,” Dad warned, then turned to me with a tone he probably believed was gentle. “Let’s not escalate. You scared me earlier. You know I hate that emergency rooms make me panic.”

“You didn’t panic,” I said quietly. “You prioritized. Like always.”

“Don’t be cruel,” he snapped, because nothing confuses a man quite like a woman choosing accuracy over forgiveness.

Eliza stood with the unbothered posture of someone who has never needed to raise her voice. “Mr. Ames, Ms. Ames: as of this morning, my client has revoked all financial and legal access previously granted to either of you. Notices are being served and receipts logged. If you have counsel, please direct future communication through them.”

Dad blinked. “Excuse me?”

Clare’s lip curled. “You can’t cut us off. We’re family.”

“You’re blood,” I said, my voice steady enough to convince us all. “That’s not the same thing.”

Dad’s face mottled red in a way I’d seen in courtrooms and crowded gyms. “After everything I did for you—”

“You raised me,” I said. “That was your job. I’m done paying you for doing it.”

He opened his mouth. I lifted my hand. “One more thing.” I nodded at Eliza. She tapped her phone. The room filled with the recording I hadn’t planned to use unless he lied: his voice crackling, weary and annoyed: “Are you dying? Don’t call in a panic. Clare needs me now.” And Clare’s voice, a echo behind him: “You’re so self-centered, Stella.”

Silence in a hospital has a gravity of its own. For a moment, the beeps seemed embarrassed to be making noise. Clare went pale under her artful makeup. Dad looked like a man who had tripped and was calculating whether anyone had seen.

“You recorded us?” he said finally, as if that fact offended some principle he’d forgotten to observe in the last thirty years.

“After you hung up,” I said. “Because I knew what would happen when I tried to tell this story later.”

Eliza opened the door with a nod so neutral it should be in museums. “We’re done here,” she said.

They left, not in a rage—rage would have been honest—but in the brittle way people leave when their favorite lines no longer work. When the door clicked shut, the heaviness in my chest didn’t evaporate. It settled differently, the way a storm settles after it’s blown the furniture around. Eliza gathered the files, slid them back into her case, and gave me a look that was mercy without pity. “They’ll try again,” she said. “Let me try for you.”

I nodded. “I can do silent.”

“Good,” she said. “Silence is a sentence. Use it.”

That night the text messages winged in like moths flinging themselves at a porch light. Clare: I can’t believe you humiliated me like that. You’ve always been jealous. You want to be the victim because it gets you attention now. Dad: After all we did for you. This is how you repay me. Then the Facebook post, vague enough to be virtuous: Sometimes the people you love the most hurt you the deepest. Loyalty matters. Comments below with hearts and prayers hands and Aunt Lorraine’s favorite sermon about how “we raised our kids better than that.”

I didn’t respond. I mute-buttoned my history and fell asleep to the soft mechanical sounds of a ward making it through another night. Near dawn, a message came from a direction I hadn’t expected: my cousin Jules. Saw the post. Just wanted you to know: I remember. Clare was always the storm. They handed you an umbrella and called it a personality. I’m proud of you.

I cried then—not the simmering tears I’d learned to swallow but the clean kind that rinse. When the nurse came in to check my vitals, I smiled at her through the blur and said, “Can you note ‘finally hydrated’ in the chart?”

She laughed like a bell. “I’ll write, ‘Patient within normal human limits,’” she said, and squeezed my hand.

By morning, with the IV pump clicking like a metronome and the first thin light sneaking through the blinds, I understood I was not, as I’d told my father, dying. Something had died, though. And in the space it vacated, there was room for a different kind of life—one that didn’t make me audition for love by bleeding quietly.

I called my therapist and left a message that said, “It’s time.” I texted Jules and wrote, Emergency contact?—and when she wrote back ten seconds later, Hell yes, I sent her a screenshot of the form. I set a timer, and when it went off, I did not check social media. I looked at the dais of my knees under hospital blankets and thought: this is a body in repair. The rest of me can follow.

Part II

Hospitals like to call the moment between crisis and discharge “medically stable.” The phrase is both promise and warning: you are well enough to leave, and too unwell to pretend the world won’t still hurt when you step back into it.

The morning after my father and sister stormed out, the ortho attending came by with a resident whose hair stuck up in a way that suggested a losing battle with sleep and humidity. “We’ll fix the tibia today,” he said, as if we were discussing a squeaky hinge. “Two screws, one plate. Clean break, dirty story.”

“Will I run again?” I asked, because hope and foolishness sometimes share a bench.

He cocked his head. “You will walk without thinking about it,” he said. “Which is what most of us call running once we’re past thirty.”

They wheeled me to the OR with a blanket tucked under my chin like I was some beloved aunt who needed to be humored. The anesthesiologist had a voice that made me want to confess things, so I told him everything I needed him to know: nausea with morphine, a tendency to wake up anxious, a father allergic to emergencies that don’t involve my sister.

“We’ll keep you comfortable,” he said, the way pilots say, We’re expecting a little turbulence. Count backwards. Lights dim. A familiar falling that for once felt chosen.

I came back in pieces: first sound, then weight, then pain negotiated down to a manageable quarrel. The nurse turned my face toward her voice. “All done,” she said. “You did beautifully.”

“I slept,” I croaked.

“Sometimes that’s the bravest thing,” she said.

By afternoon I had a new geography—a line of staples like a zipper along my shin, a cast that made my leg feel both armored and trapped. Physical therapy arrived in the form of a short woman named Carlene who wore her hair in a bun so tight I suspected it had its own credentialing. “Up we go,” she said, producing crutches like a magician. “We’re going to get you walking before your fear has time to grow teeth.”

The first step was a revelation in humility. My armpits discovered opinions. My thigh quivered with the outrage of suddenly being asked to do its job alone. “Breathe,” Carlene said. “Good. Again. You look like a woman who apologizes when she needs things. Consider these your apology blockers.”

I laughed, and the laugh surprised me with how easy it felt coming out of a body held together by hardware and stubbornness. In the hallway, a kid in a Spider-Man gown watched me wobble past. “You need a cape,” he announced.

“I do,” I said. “Preferably in black.”

“Red,” he said firmly. “Red is for heroes.”

“Duly noted,” I said, and made it to the fire extinguisher before my calf trembled and my pride gave up on pretending I could go farther without turning into a cautionary tale.

Eliza visited between her hearings and filings, a metronome of order in my life’s sudden jazz. “Notices sent,” she said, scrolling. “Beneficiaries updated. The bank flagged two attempts this morning to log in from an unknown device using your old passphrase. They locked it down.”

“Dad,” I said.

“Likely,” she said, neutral as a lab result. “I also received an email from a ‘family friend’—your Aunt Lorraine—inquiring whether it was ‘legal’ for you to betray the people who raised you.”

“What did you say?”

“I forwarded her a copy of your revocation of power of attorney and advised her to obtain counsel if she had further questions,” Eliza said, deadpan. “Then I blocked her.”

I wanted to kiss her and also buy her an expensive coffee machine. “What’s next?”

“You heal,” she said. “I mop.”

Evenings blurred into a slow parade of small mercies. Emily from work arrived with groceries and the kind of chatter that fills rooms without asking anything back. She brought plums so ripe you could bruise them by looking too closely. “Your mailbox looked… busy,” she said delicately, handing me a stack of sympathy cards addressed to my father. We’re praying for your family during this difficult time. One even had the audacity to say Children can be so ungrateful. Emily placed them face down in a neat pile. “I brought you the good yogurt.”

“Greek?”

“I’m not a monster.”

Nora texted every morning with a single sentence I wanted to staple to my wall: You don’t owe anyone your survival. Jules sent memes and pictures of her dog wearing sunglasses, and one night when sleep refused to show up for its shift, she called and we played categories until my brain bored itself into quiet.

The hospital discharged me on a Thursday under a sky that looked scrubbed. “Friend coming to get you?” Carlene asked, parking my crutches against the wall with precision that bordered on art.

“My cousin,” I said. “And my neighbor. And my therapist’s voice in my head reminding me to take the pain meds on schedule.”

“Good,” she said. “We like redundancy.”

Jules drove my car because my left leg looked like a sculpture of a threat. Mrs. Lively from next door met us in the lobby of my apartment building with a vase of daffodils and the authority of a woman who has never not been in charge of something. “I’ve already yelled at the elevator,” she announced. “It knows it’s carrying precious cargo.”

My apartment smelled like clean and lemon and relief. Emily had put groceries away. Nora had left Tupperware with casseroles labeled in her kindergarten teacher handwriting: Spinach lasagna: eat me day two. Jules helped me to the couch and then, in a ceremony that felt like it required music, dropped my old spare key into my palm.

“Change the locks?” she asked.

“Already scheduled,” I said. “Five o’clock.”

“Look at you,” she said, mock-dabbing at her eyes. “A functional adult with boundaries.”

“Don’t start,” I said, and we both laughed long enough to make Mrs. Lively bring water and a stern reminder that stitches do not care for hilarity.

At 4:58 p.m., a locksmith in a van with a punny name (KEY-nesian Economics) knocked and within twenty minutes my front door had a new vocabulary. He apologized for the noise; I thanked him like he had repaired a damaged organ. When he left, I held the new keys under the kitchen light and felt something loosen inside me. Not victory. Not even safety. Permission.

The smear campaign blossomed online like mold in a forgotten container. Dad posted Photos Of Us that had always been cropped to him and Clare in the center, my shoulder at the edge—evidence of my presence used to prove my absence. The comments judged me without variation: ungrateful, dramatic, a late-blooming traitor. I followed Eliza’s rule and did not engage. The one time my thumb hovered over the keyboard like a drunk on a high dive, Nora texted, Put the phone down. Pick up a book or a bagel.

I picked up both.

Therapy turned the volume up on truths I had kept at a polite murmur so they wouldn’t interrupt dinner. My therapist, a woman whose office plants looked better watered than my old boundaries, listened without blinking. “You weren’t loved for who you are,” she said finally. “You were rewarded for what you give. That’s a marketplace, not a family.”

I wanted to argue and then realized I didn’t. “What do I do with that?”

“You grieve,” she said. “You build a life where love doesn’t require an invoice. And you practice asking for help like a person learning a second language—badly at first, then with less apology.”

It turns out asking is a muscle you can rehabilitate. I asked Jules to sleep on my couch the first two nights because the dark felt louder than I wanted to admit. I asked Emily to sit with me while I made the first post-accident shower attempt, and we laughed so hard at the choreography of trying to keep a cast dry with a garbage bag and duct tape that I forgot to be embarrassed. I asked Nora to drive me to my first outpatient PT appointment and to promise me she’d stop me if I tried to impress Carlene by doing too much. “You have never impressed anyone by over-functioning,” Nora said, steering with one hand and sipping iced coffee with the other. “Sit down and be mediocre with me.”

PT was both religion and penance. The clinic smelled like rubber bands and resolve. Carlene had relocated from hospital to office, but her bun still made its case. “Okay,” she said. “We’re going to teach your brain that your leg is a friend again.”

“My brain is stubborn,” I warned.

“Good,” she said. “So am I.”

We breathed. We lifted. We swore creatively. I learned the difference between pain that protects and pain that lies. The first time I managed four steps on the parallel bars without clinging as if to a cliff face, I cried. Carlene handed me a tissue without commentary. “Grief in motion,” she said, like a diagnosis.

Three weeks out, my father came to my building. I knew he would eventually; men who control narratives hate closed doors. Jules was at work, Mrs. Lively at church, Nora on a field trip to the zoo with twenty-three seven-year-olds and a patience I would canonize if I could. The knock sounded like a demand.

I opened with the chain engaged. “Now is not a good time,” I said through the crack.

He leaned in, eyebrows arranged into what he must have practiced in mirrors: Concerned Father. “You’re making this so much bigger than it needs to be,” he said. “We can fix this if you stop punishing us.”

“I’m not punishing you,” I said. “I’m protecting me.”

“From who?” he scoffed. “Your family?”

“From the people who call it love when it’s actually using.”

His face hardened. “After everything I sacrificed for you—”

“Eliza advised me not to talk to you,” I said, and watched the name land like a gavel. “So I won’t.”

“You’re being brainwashed by your lawyer,” he said.

“Good,” I said. “My brain needed washing.”

His mouth opened and closed. He tried a softer approach. “Clare’s really struggling,” he said. “She can’t sleep. She’s not eating. She cries all day.”

“She can call her therapist,” I said. “If she doesn’t have one, I can recommend mine. Actually no—I can’t. My therapist is too good for her.”

“You’re cruel,” he said.

“I’m consistent,” I said. “Go home, Dad.”

He took a step back, and for the first time, I saw something behind the anger: confusion. As if the machine he’d been operating for decades had suddenly refused to turn on. He looked older—gray at his temples, the lines around his mouth cutting deeper with the work of clenching. “I don’t know how we got here,” he said finally, almost to himself.

“I do,” I said, and closed the door.

I slid down it and sat on the floor, back against wood, breathing like I’d run a race in a leg that wasn’t yet ready. I texted Eliza: He came. She replied with a thumbs-up and a copy of the already-sent cease-and-desist letter she’d drafted for exactly this moment. Her efficiency was a quilt I pulled up to my chin.

Clare tried once more by proxy: an email from a new address, subject line “For Your Records.” Inside, a long paragraph cataloging her ailments, injustices, and the ways I had failed to be a sister. The last line: Someday when Dad is gone, you’ll regret this.

I drafted three replies. I deleted three replies. I forwarded the email to Eliza and then to my therapist, who wrote back: That last line is a curse, not a concern. Return it to sender in your mind and keep your peace.

I kept my peace like a precious thing.

Out in the world beyond my phone, other people did what families are supposed to do when someone comes home with fresh scars. Emily threw a Tuesday game night and made everyone give up their phones at the door; we played Scrabble with ferocious moral debates about whether “yeet” had entered the canon (it had, and Carlene, who came straight from clinic, argued her case like a Supreme Court brief). Mrs. Lively taught me how to hard-boil eggs that peel without rage and left a mason jar of chicken soup on my counter every Sunday with a note: Heat me. You deserve warm things. Nora brought over a pile of books with women’s names on the spines and said, “Pick any. Or none. We can just sit.”

One afternoon I found myself staring at a framed photo I had always kept on a bookshelf without really seeing it: me at five with a bowl-cut catastrophe, my mother bending down to tie my shoe. She had been love in motion—quiet and efficient, the kind of care that noticed before being asked. When she died, something in our family unlatched and my father mistook Clare’s noise for need and my silence for strength. “I would forgive you for dying all over again if you could just come back and teach him,” I told the picture, and then startled myself by laughing at the sacrilege of it.

“Talking to ghosts?” Jules asked from the doorway, holding a grocery bag and an expression that had very little patience for tenderness she couldn’t joke about.

“They’re better listeners than most people,” I said.

“True,” she said, setting the bag down and pulling out a bouquet of tulips the improbable color of sherbet. “Also, they never ask for money.”

I opened the new savings account Eliza had suggested and named it something I would not be ashamed to see when I logged in: Self-Respect Fund. I set an automatic transfer for the day I used to call Dad to ask which bills needed covering this month. The first time the transfer went through, I felt the same guilty jolt I had felt when sneaking candy into a movie theater. Then I felt giddy.

On my kitchen counter, I taped a paper I had written at the top the way surgeons label anatomy: BOUNDARIES. Underneath, I wrote the sentences I wanted to be fluent in:

“No” is a complete sentence.

Silence is not absence.

I do not have to set myself on fire so other people can feel warm.

When I forgot, Nora pointed at the paper over my shoulder like a coach. When I remembered, Carlene made me tell her how proud I was of myself until I rolled my eyes and then she made me say it again.

The day my cast came off, the saw sounded like a lawn mower and smelled like fear. The resident joked with the ease of someone who has never yet had to forgive his own body for breaking. The cast split and the air hit skin that hadn’t seen light in weeks. It felt like the first page of a book that finally decided to turn.

“Ready?” the resident asked.

“Ask me again tomorrow,” I said.

He laughed. “Fair.”

The scar looked angrier than I felt. I touched the skin above it and whispered, “Good work,” because I had learned in PT that talking to your body kindly makes it want to keep you. On the way out, Carlene high-fived me so hard my palm stung.

Outside, the sky was the color of a fresh start. I stood at the curb and realized I had nowhere I needed to rush. I listed the things I wanted: coffee strong enough to insult, a bagel with too much cream cheese, an hour in a park watching other people’s dogs learn their names. I took the long way to all of them, because for the first time in months, my legs could.

At home, the answering machine—yes, I still have one because the landline number keeps the spam calls from aging relatives off my cell—blinked a single message. I pressed play. Dad’s voice, softer than I’d heard it in a year. “I’m… I’m going to give you space,” he said, as if this generosity came from him and not from a cease-and-desist letter. “I don’t understand, but… okay.” A pause. “Clare’s moving in with me for a while. Just thought you should know.”

The relief I felt was not neat. It was jagged and complicated and mixed with a loneliness I hated to admit. I sat on the couch and let both truths sit beside me without picking a fight. My phone buzzed. Jules: Ice cream? Celebratory or consolatory. Dealer’s choice.

“Both,” I texted back.

We ate from a pint with two spoons and bad TV. When the credits rolled, Jules said, “So. How does it feel?”

“Like I’m on crutches,” I said. “But the crutches are invisible. And they’re mine.”

She clinked her spoon against mine like a toast. “To ugly progress,” she said.

“To ugly progress,” I echoed, and smiled at the ceiling like it had finally forgiven me for believing fluorescent light was the only kind I deserved.

Part III

The first day I went back to work, my left leg hummed like a power line. I wore flats that made me feel like a substitute teacher and carried a tote bag heavy with the illusion that I could pick up exactly where I’d set my life down.

Emily met me in the lobby with a coffee strong enough to apologize for everything it wasn’t fixing. “There she is,” she said, and her smile was the kind that doesn’t ask for a performance. “You look like a woman who won a fight with stairs.”

“I negotiated a ceasefire,” I said. “The stairs have legal counsel.”

The office had rearranged itself without me, the way rooms do to pretend they were always like that. My desk was where I’d left it, but someone had stuck a Post-it to my monitor with a doodle of a crutch and the words GO, LEG, GO. I sat down and let the chair take me. For the first time in weeks, my inbox felt like progress instead of a threat. Answer. Archive. Decline a meeting I didn’t need to be in with a simple, Can proceed without me. Each small act of refusal felt like a stitch holding in the new shape.

At ten, a colleague with a penchant for urgency that wasn’t urgent stopped by with a sheaf of papers. “Can you review these by lunch?” he asked, placing them on my keyboard like a man who believed my work surface existed to stage his. “We’re in a crunch.”

Old me would have said yes, rearranged my morning, eaten resentment like mints. New me glanced at my calendar, felt the throb in my leg, and said, “I can have notes tomorrow. If it’s a crisis, bring it to the stand-up.”

He blinked. “Tomorrow?”

“Yes,” I said. Silence stretched, looked at itself in the mirror, and sat down. “Tomorrow.”

He recovered, laughed the brittle laugh of people for whom boundaries are a foreign language. “Cool, yeah, tomorrow is fine.”

“Great,” I said, and turned back to my screen. My heart did its old race and then slowed when nothing exploded except a myth I used to live in.

At lunch, Nora called from the teachers’ lounge. “How’s your leg? How’s your life? How’s your ‘no’?”

“It’s a sentence,” I said. “Period.”

“Punctuation queen,” she said. “I’m proud of you.”

An hour later, my phone flashed a number I didn’t recognize. The bank’s fraud department has a voice you learn to respect. “Ms. Ames,” a woman said, “we’re calling to verify a credit card application that appears to have been submitted in your name this morning. We flagged it for unusual activity.”

“What activity?” I asked, the taste of metal back on my tongue.

“New card request, expedited shipping to an alternate address,” she said, and read off a street that didn’t belong to me but did belong to a woman I had once helped move twice in one year because jobs made her itchy. Clare.

“Deny,” I said, because sometimes you get to pick the right word on the first try.

“We’ll deny and place additional alerts,” she said. “Do you want to file a fraud report now or wait for our packet?”

“Now,” I said. We went through the dance—verification, passwords, security questions that felt like answering riddles to get back into my own house. When we hung up, I texted Eliza: Identity theft attempt. Bank flagged. Denied. She replied with a link: instructions to file a police report so the paper trail would be boring on purpose.

I stared at the wall for a full minute, then closed my eyes and imagined the precise angle of Clare’s jaw when the courier failed to arrive with two inches of plastic she thought she deserved because life kept telling her yes after me.

I filed the report. It felt like flossing—unglamorous, mildly unpleasant, necessary.

That night Jules arrived with dumplings and a spreadsheet titled Security Stuff. We toggled through settings like women who had decided to be uninteresting to thieves: two-factor, alerts, a password manager with a master key so long it might as well be literature. “I’ve been waiting my whole life to be this boring,” Jules said, high-fiving me after we successfully enabled a freeze on my credit.

“When did we become the kind of people who celebrate Firewalls & Chill?” I asked.

“When the other kind of party stopped being worth the cleanup,” she said.

We were still laughing when the buzzer sounded at 8:13 p.m. Jules glanced at me. “Expecting anyone?”

“No,” I said, which used to mean surprise and now meant threat.

Clare’s voice came thin and sharp through the speaker. “Stella, buzz me up. We need to talk.”

Jules and I looked at each other for the beat you take before deciding whether to run toward a fire or call the department. “Stay,” I said, and pressed the intercom. “You can say what you want at the door.”

A pause. “I’m not shouting in a hallway.”

“Then you can send an email.”

“You’re really doing this?” she demanded. “To me? I’m your sister.”

“You’re a person who used my name to try to open a line of credit,” I said. “You’re a person who left me in an ER to cry over a rejection email.”

“That is not—”

“Deny it,” I said. “Say the words I did not submit that application and we will proceed from there.”

Silence crackled through the speaker. The old electricity of our fights. “I need help,” she said finally, and there it was, the note that always made my father’s spine fold and his wallet open. “I can’t pay rent. I can’t go back to Dad’s—he’s being impossible. I’m trying.”

“I believe you,” I said. “And I made a list.” I pulled a paper from the drawer near the door, the one Eliza had suggested I keep ready: community resources, job sites, a sliding-scale therapy directory, the number for a financial counselor at a nonprofit who had taught me how to budget when the only number I knew was zero. “I’ll tape it to the glass.”

A sound that wasn’t quite a laugh. “Are you serious?”

“Deadly.”

“You are unbelievable,” she hissed. “You’ve always been jealous.”

Jules, who had come to stand behind me with her arms crossed, leaned toward the intercom. “She’s been tired,” she corrected. “There’s a difference.”

“Who is that?” Clare demanded.

“My emergency contact,” I said, and reveled in the accuracy as a petty sport.

I taped the list to the inside of the building door and stepped back. Through the glass, I saw Clare in the low light of the vestibule—hair artful, eyeliner exact, the kind of pretty that refuses to admit it’s work. She stared at the paper like it had personally insulted her lineage.

“This is humiliating,” she said.

“It’s help,” I said.

“I need money,” she said.

“You want money,” I corrected. “You need a plan.”

She looked up at me the way she used to when we were kids and I’d found her in the closet after she’d set off her own storm—eyes huge, a hand already reaching out for the soft part of me. “Please,” she said.

Every muscle in me that had learned to move without permission lit up. I pressed my palm against the glass—an impulse I hated and loved at once. “I wish I could help the way you want,” I said. “I can’t. I won’t.”

She stepped back like I’d pushed her. “Dad was right,” she spat. “You’ve changed.”

“Thank God,” I said, and clicked the intercom off.

Her fist hit the door once, then again. Mrs. Lively opened the lobby door from the hallway with the righteous speed of a woman who considers all foyers her jurisdiction. “No pounding in this building,” she announced. “If you want to make noise, come to choir on Wednesday.”

Clare flinched. “Who are you?”

“Management of the moral variety,” Mrs. Lively said. “And a friend. Move along.”

Clare did, with a final flourish of dignity that would have been more impressive if it hadn’t come with the sound of her heel catching on the threshold.

We stood there, three women in a triangle of light. I let out a breath I hadn’t realized I’d been keeping like a spare. “I didn’t cave,” I said.

“You practiced,” Jules said. “We’re going out for celebratory pie.”

“I have stitches,” I said.

“You have Uber,” Mrs. Lively said. “I’ll get my purse.”

Pie tasted like absolution. Blueberry, the kind that leaks onto plates and stains the underside of your tongue the color of ambition. We ate and talked about nothing—I mean everything—work gossip and which neighbor had bought a wind chime so loud it counted as a cry for help, a movie where the protagonist finally refused to answer a ringing phone and the audience cheered like it was a revolution. It was.

I slept that night like a person who had finally moved the heavy thing out of the doorway and could get into the room she’d been paying rent on for years.

The next morning, a letter arrived in an envelope my father always used when he wanted to look serious: cream, heavy, embossed return address that meant nothing to anyone but him. I’d seen those envelopes for tuition notices, for “family updates,” for invitations that were actually instructions. I sat at the kitchen table and slit it open with a butter knife.

Stella, it began. No “Dear.” Straight to the case. I’m going to give you the space you asked for. As if it were a gift he was affording me. I never meant to hurt you. The apology people write when they want to keep the story’s protagonist in the mirror. Your mother always understood your heart better than I did. A sentence that made my throat close. I’m retiring next month. There’s a dinner. You’re invited. A line I couldn’t tell whether to read as olive branch or stage direction.

I carried the letter to therapy like a student who needed a grade. My therapist read it, set it down, and asked, “What do you want to do?”

“I don’t want to go,” I said honestly. “But also I want to be the kind of person who doesn’t light anything on fire by accident.”

“What would going cost you?” she asked.

“Two hours of old choreography,” I said. “Probably more.”

“What would not going cost you?”

“Nothing,” I said, and then tested the word again because sometimes the truth is simple and you’re the only one who doesn’t trust it. “Nothing.”

We drafted a reply together: short, necessary, pointed toward a future that did not require the past to be denied. Congratulations on your retirement. I won’t be attending. I wish you well. No reasons to argue with. No holes to stick hooks into. I printed it. I signed it. I mailed it. I went home and washed my hands like I’d touched insulation.

Two days later, the call came—not from him. From Jules. “Hospital,” she said, skipping the preamble because that’s what emergency contacts do. “Dad’s in the ER. Chest pain at work. They called me because your forms were updated to list me first and his paperwork still has you as second.”

My body remembered everything fluorescent all at once. The antiseptic. The noise. The ceiling tiles arranged like a crossword with no clues. “Are you there?” I asked, a hand already on my keys.

“I’m in the parking lot,” she said. “I wanted to ask what you wanted before I went in and became our generation’s sacrificial lamb.”

“I’m coming,” I said, and surprised myself with how certain it sounded.

“Are you sure?” she asked.

“Yes,” I said. “On my terms.”

The drive to County General was muscle memory. The lot looked like it always does at crisis o’clock: too full, a nurse cutting across traffic with a gait that said she had a reason, a man smoking under a NO SMOKING sign because he didn’t know what else to do with his hands. Jules waited by the automatic doors in leggings and a hoodie that said Not Today in block letters. She squeezed my fingers. “We can leave any time,” she said. “Even if our feet are still in the building.”

Inside, the ER smelled like it had its own weather—antsy and antiseptic, the barometric pressure dropping just enough to make everyone’s blood rise. We gave the desk his name. “Family?” the registrar asked without looking up.

“Cousin,” Jules said. “And daughter,” I said, and felt something in my chest snap and set at the same time.

They led us back past bays and beeps and a man insisting he was fine while holding a towel to a gash that disagreed. Dad was upright in a bed, a monitor wearing his heart like a graph. Clare sat in a plastic chair, mascara in a fine stalactite along her lower lashes. The sight of her did not cut me in the ways it used to; it tugged instead, like a sweater snagging on a nail.

Dad’s face when he saw me went through shock to anger to something like relief and then—God help us—to performance. “You came,” he said, and found a way to make gratitude sound like victory.

“I’m here until we meet the doctor,” I said. “Then I’m going home.”

Clare made a noise like a cough that didn’t finish. “We didn’t think you’d show.”

“I wasn’t invited,” I said evenly. “Jules called. I’m here because I decided to be.”

Dad looked smaller. Vulnerable. It would have been easier to be kind if I hadn’t spent thirty years being good. “I had chest pain,” he said. “It’s probably nothing.”

The monitor insisted on its right to exist. A nurse came in, took his blood pressure with the efficiency of someone who had no interest in joining a play in progress. “Doctor will be in,” she said. “Any questions?”

“Yes,” I said. “Has he consented to share information with us?”

Dad nodded. “Of course,” he said.

“Then I’d like a patient advocate looped in,” I said. “He’s… he’s not great at hearing things the first time.”

Clare scowled. “What does that even mean?”

“It means I’m not in charge,” I said. “It means he can have support that isn’t a daughter pretending to be his mother.”

The doctor came—a cardiology fellow with a calm that suggested he’d met a hundred men who thought they could outrun mortality. “We’re going to admit you for observation,” he said. “Your EKG shows some changes we want to watch. Bloodwork will help us rule out a heart attack.”

Dad nodded like he knew what any of that meant. “So I can go home tonight,” he said.

“We’ll see,” the doctor said. “We’re cautious with hearts.”

After he left, Dad shifted on the bed, the sheet catching against his leg. He looked at me with that expression he had when he wanted me to come do the thing he didn’t feel like standing up to do himself. “There’s paperwork,” he said—of course there was—gesturing toward the tray table. “They need a contact. And a… power of something.”

My bones remembered the crash of fluorescent, the sting of antiseptic, the sound of his voice on the phone saying, Are you dying? I took a breath that tasted like lemon cleaner and said, “Your contact is Clare. Or Jules. Not me. And you don’t need a power of attorney today. You need to let the team care for you.”

His mouth opened, then tightened. “This is what I get for raising you to be independent,” he said, a line he’d used so many times it had worn grooves in our walls.

“This is what you get,” I said, “for assuming independence was love.”

He looked at the ceiling and then at me and then at the space between us where family used to go to flex. The grief in his face was almost enough to make me offer him a bridge I would have to build and carry. Almost. “Okay,” he said, so quietly the monitors and the curtain and my heart drew closer to hear it. “Okay.”

I stayed another half hour. I used the call button when he tried to tough it out. I asked the nurse for a blanket that actually covered a body. I answered exactly two questions: Do you want me to call anyone else? and Do you want me to pray? The first—no, not yet. The second—not my language, but go ahead if it’s yours.

On my way out, Clare stood and blocked the door like a dog protecting a bone. “This is your fault,” she hissed, a reflex so old I almost admired its muscle memory.

“What is?” I asked.

“He’s stressed out,” she said. “You’re making him sick.”

“I didn’t hand him a phone and teach him to say no to me,” I said. “You can sit with him for once. Be the strong one.”

Her mouth opened; nothing came out. I stepped around her and into the hall, where Jules waited with a look that said everything without scaring the art off the walls.

We walked toward the elevator together, my leg remembering and forgiving, my breath finding its new rhythm. “Pie?” Jules asked.

“Pie,” I said.

In the lobby, we passed the same mural I’d stared at the day of my accident: a field of painted sunflowers bent toward a painted sun. I stopped, looked up into yellow that didn’t ask me to pretend, and thought: I came back to a place that hurt me to prove to myself I could leave it on my own terms.

Outside, the air felt honest. I tightened my scarf, tucked my new keys into my pocket, and let the door whisper shut behind me.

Part IV

The next morning I woke with the uncanny feeling that someone had moved the walls while I slept. Daylight did its best to soften corners, but recovery has a way of insisting you keep noticing. My shin pulsed in a steady metronome; my inbox pulsed in another. Between the two, a message from Jules: Update. They kept him overnight. Small heart attack. Stent this morning. Stable.

Stable. The word that had started to mean you’re okay enough to be in charge of yourself again.

I texted back: Thanks for being there. I’ll swing by later with coffee for the nurses. Then I put the phone down and stood in my kitchen long enough to let the urge to fix someone else pass. Habit is sneaky; it likes to dress up as urgency.

Work ran on its hum. Emily appeared in my doorway with a sticky note that said you’re not late; time is late and a muffin the size of a basketball. At eleven, I turned down a meeting I didn’t belong in and sent a tidy bullet point summary instead. At noon, Carlene texted a photo of a red ribbon. PT graduation incoming, she wrote. Prepare a speech about how much you love lunges. I sent back a skull emoji and a heart because grief and joy had started to share the same alphabet.

By three, the hospital itch had me. I drove to County General with a tray of coffees arranged like offerings and left them at the nurses’ station with a note: for the people who kept my spine from turning into a question mark. Then I stopped by the gift shop, because if capitalism insists on smushing comfort into plush form, who am I to resist a ridiculous stuffed sunflower.

Dad was propped in bed, post-procedure paler, monitor spelling his name in numbers. Clare slouched in the chair with her phone balanced on her knee, thumbs moving. The moment she saw me, her chin lifted into a shape that said she was ready to debate the facts of gravity if I asked her to pick up a cup.

I set the sunflower on the tray. “For your room,” I said. “It looks less like illness and more like stubborn photosynthesis.”

Dad huffed a laugh, then winced. “They say I’ll be out in a couple days,” he said. “Then cardiac rehab. Can you…?” He gestured to the stack of paperwork at his elbow. Of course there was paperwork.

“I can sit while you read,” I said. “I won’t sign anything for you.” His face showed the quick flare of annoyance—familiar as his watch—but it faded. He picked up the top sheet.

Clare dropped her phone into her lap. “Why are you here?” she asked, not curious so much as offended that my presence didn’t come with a condition she could argue against.

“Because I decided to be,” I said. “And because Jules called.”

She rolled her eyes and muttered something about boundary cults under her breath. I took out a pen and circled the nurse call button on Dad’s sheet. “Use it,” I said. “Let people help you.”

He nodded. For the first time in a very long time, he looked like a man who might listen to somebody’s instructions other than his own.

The cardiology fellow came, explained stents again, explained platelet inhibitors like a patient teacher. Dad nodded more. Clare asked if there was a natural alternative. The fellow smiled politely and said, “A different heart.” When he left, I stayed five more minutes, long enough to see Dad pick up water on his own and push the button when the monitor beeped. Small victories count when you’re re-learning how to inhabit a body without trying to out-think it.

In the hallway, I ran into a nurse who’d been on during my accident nights. “You’re walking better,” she said. “Or at least pretending better.”

“Both,” I admitted. “Is that allowed?”

“It’s encouraged,” she said, and took a coffee from the tray with a grin that felt like a secret handshake.

I didn’t go back the next day. I texted Jules for updates and sent an Uber gift card so Clare wouldn’t turn Dad’s discharge into a chance to make anyone’s guilt pay surge-pricing. When he finally went home, I got a photo of the sunflower in a living room I used to vacuum as a teenager with resentment like lint. The flower looked ridiculous. I smiled at my phone: sometimes you fight darkness with dignity; sometimes you throw a bright, silly thing at it and let it be both.

PT graduation involved a handshake from Carlene, a printout of home exercises that looked like punishment for crimes I had never been charged with, and a cheap red ribbon she tied around my crutch like it had won a county fair. “You don’t need it anymore,” she said. “But keep it somewhere you’ll trip over it. Proof.”

“Proof of what?” I asked.

“That you can be helped,” she said. “People like you forget.”

I took the ribbon home and tied it to the inside of my hall closet. Every time I grabbed a coat, it brushed my knuckles. A little flare of color in a dark place. A reminder disguised as decoration.

The retirement invitation hovered like a cloud I refused to stand under. I did not RSVP yes. I did not RSVP with an essay. I sent the card I wrote with my therapist’s hands under mine, and when a cousin texted, You’re really not coming? I replied, I’m really not and turned my phone face down. The night of the dinner, I ate takeout with Emily and Nora and Jules on my rug, and we told stories that did not require me to defend the main character from herself.

The next morning, Aunt Lorraine posted a photo of Dad in a suit at the podium, face a careful arrangement of humility and triumph. The caption read, We did it. I stared at those three words longer than they deserved. The “we” was not mine. It never had been. I put the phone down, picked up my “Self-Respect Fund” app, and moved my weekly transfer a day earlier. Petty? Maybe. Effective? Absolutely.

Clare’s next attempt landed with the precision of a drunk throw. An email titled “bridges” that began with I want to repair ours and slid quickly into Venmo handles and a suggestion that I “front” a deposit for an apartment near an art district that would “inspire” her. It ended with Dad says we’re both being stubborn. Be the bigger person for once.

I didn’t reply. I forwarded it to Eliza. She wrote back: We can send one last boundary letter, or we can do nothing. Your choice. I chose nothing. Sometimes silence is heavier than a gavel.

A week later, a different note arrived in an envelope with handwriting I hadn’t seen since sophomore year of high school: my mother’s. Found this going through boxes, Dad’s post-it read. Thought you should have it. The letter inside was one she’d written me the summer she was sick and given to Dad to pass along “when the timing felt right,” which apparently took him fifteen years and a cardiac event.

I read it on the couch with my left leg swung over pillows like a cat. She wrote in her teacher’s cursive: how she loved the way I solved problems without announcing them, how she worried that my competence made the world forget I needed things, too. I hope you never mistake being needed for being loved, she wrote. You can set things down. The good people will still be there when you look up. I cried the way my body cries when it recognizes a voice it thought it had forgotten how to hear.

I photocopied the letter, put one copy in the safe with my passport, one on my fridge under a magnet shaped like a lemon, and one in my wallet for the day I’d try to buy my way back into a story that didn’t deserve me.

Work pressed in, then receded like a tide that had finally learned my shoreline. I took lunch breaks. I said “no” without checking if it was contagious. One afternoon my boss called me into his office and said, “We’re restructuring. I want you to lead the client team. You’ll need to delegate—actually delegate, not the kind where you hand someone a task and then do it anyway.”

“And why do you think I do that?” I said.

He grinned. “Because you’re good. And because you used to think being good meant doing it all. I’ve noticed you don’t do that anymore.” He paused. “It’s made you better.”

I accepted. That night I celebrated by cleaning my stovetop like it had personally offended me and then texting Nora, who replied with a photo of a gold star sticker on her forehead.

Cardiac rehab made Dad humble, or maybe just tired. He called once, left a message I noticed without playing for two days. When I did play it, he said, “I’m learning to walk fast without pretending I’m running.” He didn’t ask for anything. I saved the audio and labeled it A new sentence.

He asked to meet for coffee when his rehab finished. I said yes with conditions: public place, Jules two tables away, one hour. We met at a diner that had lived in our town long enough to gather a patina of everyone’s secrets. Dad slid into the booth with the caution of a man who’d been taught by his own heart that bodies keep score.

He started with weather. I let him; small talk can be anesthesia for people who want to get to the point without screaming on the way. Finally, he said, “I’m seeing someone. A counselor.” The word sounded stiff in his mouth, like a foreign vowel.

“Good,” I said. “Stick with it.”

“I thought love and worry were the same thing,” he said, eyes on the laminates. “Especially with Clare. I thought… if I didn’t hold her up, she’d fall. And then I… I used you like a beam.”

“You did,” I said. When he flinched, I added, “I’m not saying it to hurt you. I’m saying it so we stop pretending we don’t know the words.”

“I can’t… undo,” he said.

“No,” I said. “You can act differently forward.”

He nodded. “I’m sorry,” he said. Not if or but. Just the two words that actually enter rooms without knocking something off a shelf. I nodded back. Moved, not repaired.

He looked up. “I have some of your mother’s journals,” he said. “If you want them.”

“I do,” I said, then placed my hands on the table so he could see they were empty. “And I still won’t be your emergency plan.”

“I know,” he said. “Clare…” He sighed. “She… I can’t make her.”

“You can’t,” I said. “It took me a decade to learn that you can’t rescue someone from a chair they won’t stand up from. You can sit nearby. That’s it. The getting up—that’s hers.”

We ate diner pancakes like diplomats. When the hour ended, I checked my watch and he smiled a little. “You’re leaving on time,” he said.

“I am,” I said. “You’ll survive.”

He did. I did, too.

Spring stepped onto the stage with the kind of show-off energy that makes even cynics water plants. My scar faded from angry punctuation to a pale line you’d miss unless you looked for it. Carlene texted a photo of the ribbon on her own bulletin board—“Graduates I actually liked.” Emily got engaged to a woman who laughs like a cello. Nora’s class released butterflies and one insisted on landing on Nora’s hair and staying there long enough for twenty-three seven-year-olds to scream in spiritual delight. Jules started dating a baker who believes pie crust is a love language and argued me into a second slice more often than I said yes to anything else this year.

Clare went on the internet less. Or maybe I just stopped visiting the edges of rooms where everyone gathers to shout and pretend it’s singing. Once, months later, an email landed with a subject line that didn’t try to sell me anything: I got a job. The body read: Part-time at a ceramics studio. It’s small. It’s… it’s something. No ask. No hook. I wrote back: That’s good, Clare. I hope you like the clay under your nails. She sent a single dot back. It was the most honest exchange we’d had in a decade.

On a slow Sunday, I drove past County General and, on impulse, pulled into the lot. I walked into the lobby where the sunflower mural still leaned into a painted sun, and I stood there long enough to say thank you without sounding ridiculous. A teenage volunteer pushing a book cart smiled at me, and I smiled back because we were two people in a place built to hold the worst of our days while letting us get to the next ones.

The antiseptic smell still hit me like a memory. It didn’t knock me down anymore. It didn’t even need to be forgiven. It was a smell, doing its job, reminding me of mine: to leave when I can, to stay when I choose, to keep the keys to my own house in my own pocket.

On the way home, the light turned green at the exact second I reached it. A small, stupid grace. I laughed out loud, by myself, in a car that had learned my new routes, and decided to take the long way for no reason other than I finally could.

When I got home, the red ribbon brushed my knuckles. The letter on the fridge lifted in the AC breeze and settled again. The phone stayed face down until it buzzed with a text I actually wanted—Nora sending a photo of her students’ butterflies on the loose, the caption Chaos, but pretty.

I set water to boil for pasta and threw in too much salt because it tastes like oceans and I needed to taste something bigger than my own questions. I thought about the fluorescent ceiling, about the antiseptic sting, about the recorded call I kept in a file named For When I Doubt Myself. I will never forget those minutes—not to keep them alive, but to make sure I remember the door out.

You don’t have to bleed to be loved. You don’t have to be the strong one to deserve someone sitting beside your bed. You don’t have to be perfect to keep your own peace.

That night, I locked the door. Not because I was scared, but because I could. I turned off the light. Not because I was alone, but because I wasn’t. In the dark, I heard the quiet domestic noises of a life I chose: the tick of a cooling stove, the thrum of a neighbor’s washing machine, the soft whirr of the fan overhead. Small, ordinary mercy.

When sleep came, it didn’t ask me to explain myself. It just arrived. And I let it.

The End.

News

📕I Cared for Her Through Cancer—stood by every chemo and fear—yet she married her first love instead… CH2

Part I: The first time the chemo pump beeped, I thought it sounded like a bedside alarm—one of those cheap…

He put a wedding ring on his mistress and said I was just a burden,I can’t live without him… CH2

Part I The plus sign was faint. Barely there, the softest whisper of pink crossing a white stick on my…

I OVERHEARD MY MOM CALL ME DUMB IN FRONT OF THE WHOLE FAMILY. THEY ALL CLINKED GLASSES, “HERE’S TO… CH2

Part I: I didn’t hear the toast so much as feel it—like a fork raked down a chalkboard somewhere inside…

Twenty Doctors Failed to Diagnose the Heiress — But the Single Dad Janitor Saw One Tiny Clue… CH2

Part I: Night Shift The silence in Room 1219 wasn’t really silence. It was a quilt of soft, mechanical assurances—steady…

“Get her ready to welcome Skylar home.” “Sir, she’s gone—leaving only the divorce papers.” CH2

Part I: The first time Ethan Cole disappeared after another woman, I told myself it was a phase. The second…

My Sister Slept With My Husband And Got Pregnant, My Parents Sided With Her And Demand I Support… CH2

Part I My name is Lisa Wyn, and I learned early that responsibility wears a face. It looks like the…

End of content

No more pages to load