Part I:

I hit the deck before I even hit the deck.

The way my mind replays it, there’s a half-second of slapstick silence right before gravity eats me alive—like the world inhaled and forgot to exhale. One moment I’m stepping off the threshold into the backyard circus; the next I’m vertical air, flailing arms, those dumb party streamers a rushing blur overhead while the brand-new red-cedar deck Dad had been bragging about glints like a lie in the Carolina sun.

Charleston summers aren’t kind. The sky that day was a skillet; everything living in it sizzled. It was 90°, the air salted with ocean, sweat, and charcoal smoke. The backyard looked choreographed to be enviable: open grill blooming with flames, an iced keg sweating beside the cornhole boards, lawn chairs turned to catch the breeze that never came. A row of gifts on the patio table—their bows thin and careful, not so much generosity as obligation. You know how the party photos look perfect on a screen when they’d felt like a cough you can’t suppress? It was that kind of day.

Caleb stood shirtless at the center like a flag at the summit he’d declared, the loudest hill on the cul-de-sac. He had the beer, the biceps, the sunglasses, the way of shouting a joke so everyone laughed whether it was funny or not. Two friends hovered flanking him as if being close to him made life count more. He lifted a Solo cup like we were all the audience he deserved.

I had a paper bag and a stiff smile. Inside the bag: a decent bourbon, a hundred bucks inside a card that said Happy Birthday, Bro! in a font that looked like a bad tattoo. The kind of gift that means: I’m here so no one can say I wasn’t. I like clean exits. I imagined I could sneak in, drop the bag, nod at Mom, nod at Dad, dip by the time the cooler got opened a second time. That was the hope.

I was three steps from the edge of the deck, aiming for the gifts, when the plank under my boot went from grippy to glassy. My foot slipped so decisively that my mind, always a beat behind the body, produced the thought—ice?—even though there was no universe where ice existed on that deck. My other foot followed, a puppet string cut. It wasn’t a stumble; it was an erasure, like the floor decided it had better places to be and left me appointmentless midair.

I twisted, arms scrambling for a rail that wasn’t there, and found the edge of the pool’s concrete lip with my lower back. The sound was a ceramic crack in a silent museum, obscene and too loud. My lungs went on strike. A flashbang of white. Pain arrived not as a stab or burn but as a hum under the skin, a hungry engine chewing the cable that connected thigh to brain. Then absence—below my waist, nothing. I tried to wiggle toes I couldn’t find.

“Dude, that was not supposed to go like that,” Caleb said, sliding into view like he’d been waiting on his cue. He was laughing the laugh he’d practiced since seventh grade, the one that always meant: the joke is on you, so we can feel safe. I couldn’t breathe enough to answer. I managed a broken whisper: “I can’t move my legs.”

He waited for the punchline I didn’t own. “Stop being dramatic,” he said. “You’re fine.” Somewhere behind him, the lawn roared. That was his gravitational pull—he could bend other people’s eyes to see what he insisted on.

I reached for my phone—it had skidded across the patio like it had better friends—but my arm couldn’t find the angle. The concrete was both cold and burning under my palms, the edges of the deck shimmering with oil I still refused to recognize as real. Somewhere, a Bluetooth speaker hissed back to life; someone turned it up as if volume could iron reality flat. As if the soundtrack might convince me to be funnier, lighter, less trouble.

“Get up, Ryan,” Dad barked without turning his head, as if sick of the choreography not going to plan. He had a spatula in his fist like a gavel. He stood before the grill, proud patriarch at his forge. He loved this posture—the maker, the disciplinarian, the veteran whose rules were reality. “You’re making a scene.”

“My legs,” I said, swallowing against a throat that refused to cooperate. “Dad, I can’t—feel—my legs.”

Mom appeared in a halo of perfume and sunscreen and the careful smile she wore only when people were watching. She crouched enough to look like a mother in a photograph, not enough to see me. “Sweetheart,” she whispered. “You’re overreacting.” She willed my crisis to shrink. “It’s Caleb’s day. Don’t ruin it.”

There’s a kind of silence that isn’t absence but pressure. It sits on your chest, expects you to apologize for needing air. The party’s laughter stalled like a car at a light; everyone floated in neutral, faces cut into polite smirks that practiced fun while studying me like I was an unpaid debt. My body refused to obey any reasonable command. My legs lay as irrelevant as props.

Then a woman in navy scrubs shoved through the ring of party spectators, a Solo cup still in her hand like she’d sprinted without setting it down. “Back up,” she snapped. “I’m a nurse.” The room—the yard, the whole social climate—shifted at her voice. She crouched, fingers decisive, the first human touch that day that belonged to me rather than the reputation of me. She ran her fingers down my spine, along my hips. Pain lit up in patches that shouldn’t exist, and in others there was nothing, like a map with blank oceans where a continent should be.

“He needs an ambulance—now,” she said, looking up with a fury that made the air honest. She turned to Caleb. “You oiled the deck?”

His mouth opened and closed like a fish dropped into air. “It was just a joke,” he said—his ancient plea, his thesaurus of denial sealed into one shrug. The nurse did not dignify it with a philosophy class. She stood, hand on her phone, voice raised so the house could hear. “Call 911,” she shouted at no one and everyone. “He has a spinal injury.”

Someone finally moved. A man fumbled for his phone like it was heavier than he remembered. Another guy jogged to the side gate to wait for the ambulance he probably hoped would turn off its sirens out of respect for property values. Mom straightened and drifted backward as if paralysis were contagious. Dad stared at the deck, the grill, anywhere but at me, flipping burgers with a chirp that sounded like cowardice.

I lay under a sky too blue to be serious, and listened to my heartbeat crawl into my ears. Not a single apology, not a single “I’m here,” not a single palm on my shoulder that meant more than performance—until the nurse’s fingers wrapped my hand with enough pressure to anchor me to the earth. “Don’t move,” she whispered. “Stay with me.”

I stayed because I’d been staying my whole life. Staying quiet. Staying small. Staying out of the way so the loud son could bloom. I stayed there while the air whistled into and out of my lungs like it was tired of the job. I stayed while neighbors who’d lived on the next street over for twenty years watched me like a sports replay. The barbecue smoke rose and curled into a halo above Dad as if God himself had taken up community theater.

There’s a second story that stacks under every first story like a secret basement. Mine started long before the slick deck. I could feel the old house like a bruise pressed from inside: the bungalow with the white columns and perfect hedges, the living room that “nobody was allowed to use,” the dining room that smelled like lemon polish and church. The house was immaculate in the way shame sometimes is. We vacuumed lines into the carpet like crop circles to prove we’d been careful.

Dad’s haircut was the military’s gift to our family—clang-sharp and eternal. His rules were brick. Pain was weakness. Emotions were viruses. Crying was an infraction punishable by exile to my room, where I’d learn how to swallow the sound inside my own ribs. If Caleb hit me, if he tripped me, if he microwaved my toothbrush “for science,” we both got the same sentence: me for being “dramatic,” him for being “a boy.” Mom drifted like tissue paper down the hallway, smoothing everything except what mattered. She liked quiet rooms and compliments from church ladies. She did not like conflict unless it was the kind she could shush with casseroles.

At eight, when I went face-first into gravel because Caleb decided I looked better airborne, Mom drove me to the dentist in silence. “You know your brother has a lot of energy,” she said later, like the swelling in my lip had been impolite of me. “Try to stay out of his way.” At eleven, when he locked me in the crawl space and turned off the light, my voice shredded howling and the spiders found me by sound. When Dad finally hauled me up, dirt-streaked and shaking, he looked bored. “You’re too old to be afraid of the dark,” he said, like wisdom.

So when Caleb stole, it was “misplacing.” When he broke, it was “learning.” When he humiliated, it was “teasing.” And when I left at nineteen, it was “overreacting”—though they liked that I’d picked something “manly” to do. HVAC installation became my sanctuary, a world that behaved according to thermostats and math, where air moved because I told it to. In Greenville, the quiet had edges I liked. You fix a thing; it gets better. You show up; they write your name on the board. No one posts your worst moments online after dinner.

But there’s that quiet bell that mothers own, rung at Thanksgiving and birthdays: Come home, sweetheart. Don’t hold grudges. Family is everything. The word everything did a lot of heavy lifting. It included laughter at my expense, included Dad’s lectures polished to an acrylic shine, included the way the whole house bent toward Caleb like a sunflower.

So when Mom called a week before his birthday and said, “He really wants you here—he’s different now,” I believed her enough to pack the bourbon and the hundred. I believed her enough to drive two hours with my jaw locked and hands at ten-and-two. I believed her enough to step onto the new deck I’d been warned about for weeks, Dad’s newest sermon on upward mobility and correct pride.

I didn’t know there was oil until my boot argued with the earth. I didn’t know my life had split down the spine until the nurse’s hand found mine. I didn’t know how to leave that yard without my legs, or that I never would.

When the paramedics arrived—sirens insisting on reality—Dad finally set down the spatula. His mouth was a line. His eyes were a question he didn’t ask. The nurse spoke to them with a voice that made me think of triage tents and night shifts. “Spinal precautions,” she said. “Board and collar.” Hands multiplied. The world learned a new language in a hurry. Caleb watched, pale as if someone had unplugged his sun, a boy at the edge of a story that wouldn’t let him rewrite the ending.

They slid me onto a backboard, rigid and unmerciful. The deck’s sheen stared up at the sky. A paramedic murmured the steps for my benefit: collar, straps, lift on three. In the echoing between each count, I heard Dad’s earlier command like it had been spoken by a ghost: Get up, Ryan. You’re making a scene. The scene had erupted without my permission. I lay strapped to a portable truth.

As the gate swung open and the gurney rattled down the side yard, someone—one of Caleb’s finance guys with expensive sunglasses—muttered, “Damn, man.” It was the first honest prayer of the day.

The ambulance swallowed me. The door shut, a clean industrial clunk. The nurse—my nurse, though I didn’t know her name yet—climbed in beside me, knuckles still rigid around the strap of her cup, which she finally set in a corner. She kept my hand in hers. She didn’t look away. Sometimes love is not a noun; it’s a competence.

“Stay awake, Ryan,” she said. “We’ve got you.”

The siren found its howl. Charleston streets blurred backward. Heat and blue and noise insisted that the world was the world, not the one we’d rehearsed at home where everything could be pretty if you stared long enough. I did what she told me. I stayed.

Part II:

Emergency rooms don’t hide what they are. They hum with fluorescent confession. The ceiling tiles keep secrets like bad priests. It’s cold enough to punish sweat, bright enough to make lies flinch. Someone had stripped away my shirt and dignity and slid a gown onto me like a joke I didn’t understand. I felt very far away and then too close to everything, the body a theater that had decided it preferred tragedy.

They parked me in Trauma 3, a number that sounded like a scale. A different nurse, a doctor with hair pulled tight and a voice like a bridge—solid, carrying weight—leaned over me. “You’ve suffered a spinal cord injury,” she said, words that came as if they belonged to the oxygen I needed. “There’s swelling at L1-L2. We’re stabilizing you, but I need to be straight with you. Time matters. Delay increases damage.”

The word delay didn’t trip; it slammed. I saw my father’s hand flipping a burger like an alibi, and my mother’s fingers smoothing air that wouldn’t lie flat. I swallowed, throat sandpapered. “Am I—?” The word paralyzed caught, juvenile and huge.

“We don’t know the full prognosis yet.” The doctor’s eyes didn’t blink their empathy. It existed, but it didn’t hide the fact. “For now, you have no motor function or sensation below the waist.”

I turned my head. Somewhere between me and the wall, all the years layered like slides on a projector. Eight-year-old me with a split lip, waiting to learn how I’d made the day hard for everyone else. Eleven-year-old me counting the seconds in the crawl space, promising the dark I’d never be scared of it again if it would give me air. Nineteen-year-old me packing a duffel into a beat-up Civic, promising I’d only drive back for funerals and then showing up for parties anyway, because guilt is oxygen in families like ours.

A nurse fitted a collar around my neck, and I found the ridiculous thought that I’d always wanted a superhero cape. This was the opposite: a brace for a spine too honest. IV lines spidered into my arm. An orderly murmured to another: MRI queued, neurosurgery paged. Everything happened and I lay there, a witness to my own body being written up as a crime scene.

Two officers arrived with the kind of careful posture cops use when they’ve learned to listen for explosives in rooms. Their names stuck because they said them quietly: Peters and Ruiz. “Mr. Thompson,” Peters said, not reading the name from paper but from the badge above my bed. “We’re taking statements regarding your injury. The nurse on scene flagged potential criminal negligence.”

Criminal. Negligence. Words like those echo, uninvited, into the chambers where family lives. They sound too large for the kitchen table. They sound exactly right for what happened.

“It wasn’t an accident,” I said. I kept my voice calm because I’d learned long ago that raised voices lose arguments in our house. “My brother poured oil on the deck to make people slip. He told me to walk across it. After I fell, he laughed. I told him I couldn’t feel my legs. He said I was being dramatic.”

“Anyone else who could have helped but didn’t?” Ruiz asked, pen poised but not yet writing.

“My father told me to get up. My mother told me not to ruin the party.” It felt like I was reading a script in the wrong genre.

They wrote. The pen made a sighing sound I’d never noticed pens make. Officers learned about families from domestic calls; they had a whole vocabulary I was just now learning to speak. Peters nodded toward the end of the stretcher. “We have the nurse’s statement. We’ll add yours.” He didn’t say: We’re sorry. He said, “We’re on it,” which is the more useful thing. Then, very simply: “Do you feel safe with them in the building?”

The question surprised me. He meant it literally—did I feel safe with my family—but I heard the metaphor in it. Do you feel safe with your family living inside your body?

“They’re not here,” I said. I didn’t mean the building. I meant me. I meant: they never were. He and Ruiz exchanged the quick look of people who have seen this shape before and don’t need to be convinced it’s real.

Later, a technician slid me into the metal tunnel that would photograph my catastrophe, my arms strapped to my sides like a saint in a bad painting. The machine’s thudding became a metronome for the inventory I was taking of the house of glass I grew up in.

The house worshipped order. We learned how to set the table with forks in rank and file, knives pointing inward as if harboring our secrets. We learned to make our beds with sheets tight as a chest. Dad measured respect in silence and chores done before being asked. He didn’t say “I love you” unless he was reading from an anniversary card to Mom in a voice that sounded like he was practicing English phrases for a test. Even then, he would not meet our eyes. He preferred function. He respected results.

Mom, on the other hand, was all appearance, a girl in a permanent church photo. She did kindness like a hobby; she did comfort like someone stepping on a floor she was afraid might break. “Just let it go,” she’d say whenever Caleb set the house on fire metaphorically and we stared at the actual scorch. “Just let it go, sweetie.” She had never once said that to him.

Caleb learned early that if he laughed first he owned the room, and if he owned the room he was forgiven before sin. He knew how to send a paper airplane into a Christmas dinner so it hit me square on the nose. He knew how to turn my nickname into a word that peeled my skin. He knew when to say “just kidding” so everyone else could exhale relief. He knew how to guide the whole family’s eyes to the wrong thing when the right thing might make him bleed.

I was good in school but not loud about it, which meant it didn’t exist. I cleaned my room without being asked, which got me accused of being smug. I learned how to fix broken things because fixing was how I could control a universe that refused to slow down long enough to ask how my day was. I became an HVAC guy in a world that blessed you if you could make a room breathe easier. The irony would be funny if it didn’t feel like a curse.

The MRI spit me back out into the cold. The doctor returned with images that looked like maps from a geography I never wanted to visit. She showed me a flare of brightness where swelling drowned signal. “We’re starting high-dose steroids,” she said. “We’ll decompress surgically if indicated. The best we can do right now is minimize further injury and give your cord time to declare itself.”

Declare itself—like a witness at a trial, like a nation proclaiming a new border. I wanted to ask what my body would declare me, but I didn’t, because I already knew. Disabled. Paraplegic. Words like medals I never asked to wear, heavy on a chest that now had to become a new version of bravery.

By evening the room had quieted. The Republican National Convention’s highlights ghosted from a TV two bays over. Nurses moved in reliable circuits, their competence a comfort I clutched because everything else had gone soft. No balloons arrived. No flowers. My phone lay face down on the tray table, cracked at the corner like it had gotten into a fight on the patio and lost. No messages.

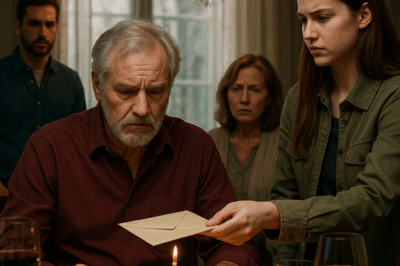

At nine o’clock, two hospital security guards rolled past the door with a deputy sheriff and a young man in handcuffs. The deputy’s voice carried: “Caleb Thompson?” His tone was dry as the moon. My brother’s eyes were wide like the first day he’d learned that gravity would not always like him best. He didn’t look into my room. That was new. For years he’d mined my expression for the joke of it. Now he looked at the floor as if there were answers there. I learned that the nurse who had held my hand had walked straight to a phone and told the 911 operator that there was reckless endangerment at the address, and that an adult male was impeding medical assistance after causing a hazardous environment. She had written her name on the world where mine had been written lightly. Someday I’d learn her name. For now she existed like a law finally enforced.

When the deputy’s steps receded, I closed my eyes and saw the dining room of our childhood, chairs pushed in with military precision, napkins folded into shapes too obedient. I had always thought the house was glass because it caught the light and because we were always polishing it. It turns out it was glass because it shattered the first time someone told the truth about it.

They admitted me. Overnight, I woke in fragments. Pain came and went like trains in a town with one platform. At some quiet hour, a chaplain stopped by with a pamphlet and a smile soft enough to put your head down on. I told her I didn’t need prayer; I needed a door that didn’t lead me back into that yard. She nodded as if she had keys she couldn’t use.

The morning brought a woman in a gray pant suit whose handshake had edges. “Assistant District Attorney Amanda Reynolds,” she said, placing a card on the rolling table with the crispness of a verdict. “Mr. Thompson, the state intends to pursue charges against your brother for reckless endangerment, possibly aggravated assault. The nurse’s statement, combined with witness accounts and your injuries, is significant.”

She paused. Her professionalism had the sort of grace that asks permission to keep talking. “There’s also another angle,” she said. “We’ve spoken to multiple witnesses. Your parents were present when you declared you could not move your legs. They discouraged aid, delayed emergency response. We’re opening a formal inquiry into their negligence.”

If there’s a temperate climate in hell, it’s that room, that moment: when someone official says out loud the thing you’ve lived your whole life and no one would acknowledge. I didn’t cry. The room had taken that right the moment they cinched the collar. I said: “Good.”

Reynolds slid another card across the table. “For your civil case. Linda Cho. Top-shelf personal injury. She can pursue homeowner’s policy, personal assets if necessary. The medical costs alone will be substantial. You shouldn’t carry that.”

“I won’t,” I said. It came out like a vow I’d sworn years ago, before any courtroom needed to hear it.

Reynolds nodded. “We’ll be in touch.” She looked at me not as a victim but as a person bearing witness. It felt like someone had turned the air down three degrees and made it honest.

After she left, I lay listening to the hospital’s dialect: the Doppler of carts, the neon lowing of a heart monitor three bays over, the plastic whisper of curtains that used to separate privacy from performance. I had performed so long that I didn’t know what my face did when I stopped. I practiced. It turned out my face didn’t break. It turned out my face could look exactly like the truth and the ceiling didn’t collapse.

I remembered the way Dad had lectured about the new deck as if wood and money and craftsmanship would insulate us from chaos. “Fifteen grand,” he’d told the neighbor. “Worth every penny.” Then he’d sloshed beer into a red cup like it was Communion and overlooked the slick. He’d always been so proud of surfaces—fresh paint, grass cut military short, a flag ironed. He never noticed the spilled oil that made every step a hazard. He had never wanted to.

That night, a neurosurgeon with an exhausted kindness came to draw me a map on a whiteboard. “We’ll watch the edema,” she said. “Decompression if needed. Rehab, certainly.” She said words like motor-incomplete and ASIA scale, which sounded like continents my body might yet explore. She didn’t promise steps. She refused hope packaged as certainty. I respected her like I respected good tools: they did what they said and nothing else.

When she left, I let my eyes close and dreamed I was standing at the kitchen sink in the old house, running water until it went from lukewarm to scalding to prove it would obey. I stood there for hours in the dream, brave enough to reach into the boil and turn the handle off.

When I woke, I had a number of new enemies: gravity, waiting rooms, the past. But I also had allies I could name: a nurse whose hand could translate fear, a doctor who respected the word no, a prosecutor with a card made of steel, two cops who didn’t shrug when a family pretended nothing had happened.

Under the lights, under the collar, under the evidence that my body would have to learn an entirely new alphabet, I learned the first rule of the real house I would build: nothing glass.

Part III

The system is a Rube Goldberg machine that only looks random from above. If you zoom in, each marble’s path follows gravity’s calculus. A drop here, a lever there, a bell rung not by magic but by someone’s hand. I had never asked to know its gears. Now I ate breakfast under its schematic.

Linda Cho called two days after the ADA. “Ryan, I’ve read the incident report,” she said, her voice blade-clean. “We have admissions from Mr. Caleb Thompson. We have witness testimony regarding your parents’ discouragement of aid. We have photographic evidence of oil residue on the deck. We have ER documentation. This is not a question of if—we push on how far.”

“How far,” I repeated. The words tasted like a handhold.

“Homeowner’s policy first,” she said. “They’ll try to dispute negligence. They’ll pretend your own ‘carelessness’ contributed. They’ll introduce words like assumption of risk. We will set those words on fire. After the policy maxes, we go personal: the house, pensions, savings. We’ll talk liens, we’ll talk a medical trust. I want you to focus on staying alive and doing what the rehab people tell you.”

“Copy,” I said, because I’ve always liked the crispness of radio-speak. It’s nice when human response comes with an expectation of follow-through.

We filed. The insurer folded faster than I expected, a million-dollar check thrown like a sandbag onto a flood they’d rather not plug with their fingers. It was both a number that could save a life and a number that only sketched the outline of mine. Surgery, hospital weeks, rehab months, adaptive equipment, bathroom renovations, vehicle retrofits, chair fittings, cushions, braces, pressure-sore prevention, home-health visits, lost wages, the forever-ness of it—nobody who hasn’t lived it knows.

Linda had already drafted the next suit before the first check cleared. I signed with hands that shook not from doubt but from steroids and rage. In the meantime, the criminal case widened like a river in spring.

Caleb’s hearing was short the first time—arraignment, charges read in a voice that made them real. Reckless endangerment. Negligent infliction of grievous bodily injury. The judge looked over his glasses at a young man who’d learned to grin his way down the hallways of the world, and did not grin back. When the ADA moved to add an enhancement based on impairment caused, the judge asked a question for the record: “Is the victim’s injury permanent?” The answer, carefully phrased, felt like a future nailed to a plank. “Motor function remains absent. Prognosis guarded.”

My parents sat behind Caleb like ghosts dressed in beige. Mom clutched a purse like a rosary; Dad stared at the flag as if expecting it to salute back. Neither turned when I rolled into the back of the courtroom with the hospital transport driver behind me. I tried to feel the old dread. To my surprise, it had expired. All that remained was a vacancy where fear used to live, and a new tenant: boundary.

The civil case’s first order of business after the policy payout was neat cruelty. I say neat because Linda refused mess. Receivership. Liquidation. A petition for sale of the family home that had ascended our Christmas cards for twenty years. You can’t foreclose on your ancestors’ earthquakes, but you can on the pretty brick that was always meant for postcards. They fought, of course. Their lawyer fired letters that smelled like cologne—righteousness in Times New Roman. He appealed to sentiment, to “misunderstanding,” to “a family matter better resolved outside the courts.” Linda answered with photographs of tread marks of oil across the deck, with transcripts of 911 calls, with my imaging printed in rectangles that made it hard to pretend.

They sold. They didn’t send me the listing, but I found it online. “Immaculate colonial. New red-cedar deck. Perfect for entertaining.” The photographs didn’t show the oil, but I swear I smelled it coming off the screen. When the closing happened, Linda filed to redirect proceeds to the medical trust. The judge signed. “For the care of Mr. Ryan Thompson,” it read, “to be administered by a trustee and shielded from access by the defendants.” The law took my parents’ wealth not to punish but to repair what their love had refused to recognize.

People say money doesn’t fix anything, and a lot of the time that’s true. Money is a tool; it cannot be a father. But when you’re paralyzed, money is slope. It flattens stairs. It cuts doorways. It hires hands that lift you when you can’t lift yourself. It buys the chair that won’t grind your skin down into a wound that eats bone. The first time I rolled into my apartment with a ramp Linda’s check bought, I cried because it meant I could roll into my own apartment. That is a sentence that never mattered when I walked.

On the criminal side, Caleb pled. He had to. The evidence had less wiggle-room than a coffin. He cried in court, not crocodile—open weeping that looked like a hole in the world. I didn’t take pleasure in that. I took inventory: tears are a fluid the body evacuates when it doesn’t know what else to do. He said he hadn’t meant it. He said he thought I’d slip and everyone would laugh and then he’d help me up. He said he froze. He said the magic words “I’m sorry” like someone had told him to say them. He said he was getting help. The judge listened, face like granite under rain.

“Intent is not a spell that cancels consequence,” the judge said on the day of sentencing. “You intended to humiliate your brother, which has a gravity of its own. You created a hazardous environment. You then delayed aid. This court cannot return to Mr. Thompson what was taken. It can only affirm that what you did is a crime.” Two years in state prison. Three years probation. Community service with an injury rehabilitation nonprofit during probation, which was a needle threaded through a painful fabric: letting him see and maybe learn; making him useful or at least confronted.

As for my parents, the ADA had been careful. There’s a line where cruelty ends and criminal neglect begins. The judge found their feet on it. “Reckless disregard in responding to a medical emergency,” the misdemeanor read. One hundred hours community service each, probation, fines, and the kind of humiliation that finally adds weight to the word. They didn’t look for me when they left the courtroom. I didn’t look for them.

I thought I’d feel clean. I felt like a room after a good scrub, where the chemical smell lingers and you open windows and wait for it to clear. It would take time.

But now there were practical things to do: revision of a bathroom into a room that no longer tried to kill me; grab bars where glass had tried to live; a roll-under sink; a cutout in the counter so I could sit while cooking. A hospital bed delivered like a spaceship into a bedroom I wasn’t sure wanted it. The rehab center’s intake meeting: a calendar of pain disguised as hope. A social worker with binders like armor explaining insurance coverage as if it were made of wet paper. I started to notice the world had two kinds of clipboards: ones that helped, and ones that hid.

When I first transferred from the chair to the bed without being dropped by a second pair of hands, a feral, ridiculous pride rolled through me: I am not a parcel. When I first learned the ineffable art of a pressure release—using my arms to lift and hover to save my skin—my biceps shook like I’d moved a planet. When I cursed and the therapist laughed without flinching, I felt more human than I ever had kneeling at the altar of my parents’ version of goodness.

I used to think being a man meant never needing help. The first time a nurse helped me flip so I wouldn’t develop a wound that could hospitalize me, she said, “You doing okay?” I told her that okay was a lie that came with our water bills at home. She snorted. “Then don’t say it. Say the truth.” I said the truth until it bruised my tongue: It hurts. I’m scared. I’m learning. I can’t believe I’m learning, but I am.

On a Tuesday when I had nothing left and still got in the car for court-ordered deposition, the opposing counsel asked if I’d considered how my “participation” had encouraged the prank. If I had simply declined to step onto the deck, would my injury have occurred?

Linda’s objection was a thing of beauty. “Asked and answered. Victim-blaming. Counsel can depose physics while he’s at it.” The court reporter smirked into the stenotype.

That night I slept three hours and dreamed not of falling but of stepping off the deck and simply…stopping. Hands raised. Saying no. I woke with my palms aching like I’d clutched a rope. I promised myself that the next time any Caleb, any Dad, any Mom said “Don’t ruin it,” I would ruin it sooner.

Sometimes I’d stare at the check register of the medical trust and feel petty triumph. Most times I’d stare at it and feel like I was looking at irrigation lines in a field after fire. Necessary. Unromantic. Lifesaving. The system had turned my family into defendants and me into a plaintiff and every headline into fodder for people in office waiting rooms. But if justice is a machine, it still needs human hands to push. The nurse’s hands. Linda’s hands. The ADA’s hands. The bailiff’s hands. My hands, gripping ideals I didn’t realize were available to me.

I had believed that the law was for other people. Turns out it was for me too. It didn’t cure me. It didn’t hug me at night. But it raised a frame in the place where the house of glass had stood, and it hung a sign at the front: No more pretending.

Part IV:

Rehab is a church with no hymns and a thousand small altars: pulleys and bands, mats and braces, sticky floors that demand you earn every inch. If you stay long enough you learn the liturgy: core first, breath second, then everything else. The first day, I puked in a trash can after twenty minutes of zero-gravity exercises meant to convince my torso it could exist without its old conspirators. Eric—the therapist whose haircut said military and whose eyes said kindergarten teacher—held the trash can and the towel and my gaze. “Half the guys baptize the can,” he said. “Consider yourself initiated.”

If I’d had the energy, I would’ve told him to shove his euphemism. Instead I wiped my face and said, “What’s next?” His grin had no mockery in it. “Now we begin.”

We began with a metronome on the wall. We began with arms that thought they were day laborers and learned they were also architects. We began with breath: in on the reach, out on the press, a rhythm I started to trust like an old song. We began with balance, which is a lie when you are strapped into a standing frame and the blood in your head turns into bees. We began with me cussing and then apologizing and then being told by Eric to stop apologizing because apology is a luxury we reserve for something we actually did wrong.

He named the victories before I saw them. “Your sit pivot is cleaner,” he said one Wednesday, as I swapped chair for mat without scraping my butt like sandpaper. “Your triceps are showing up to work.” A week later: “You sustained a pressure release for sixty seconds. That’s a Harvard scholarship in this church. Take the win.” Another week, after what felt like a lifetime of nothing below the navel, a ghost of sensation dappled my thighs. Eric didn’t clap. He said the line I wanted a father to say my whole life: “Once is luck. Twice is earned.”

By the end of the third month, I stood for the first time in braces strapped to my calves and waist, a walker in front of me like a fence I could move. The whole gym hushed in the way rooms hush when someone stands after the world told them to sit. I did six steps that were less steps than defiant physics experiments, then fell back onto the mat and laughed until my ribs begged me to stop because they were still mine and I was using them.

I turned my apartment into a place that actually wanted me. Cut the counters. Lowered the rods in the closet. Installed the bars. A carpenter friend from HVAC jobs refused payment and took beer instead: “You bought my kid a winter coat last year when my hours got cut,” he said. I had forgotten. He hadn’t. The trust paid the contractors I couldn’t owe; my gratitude paid the ones who wouldn’t bill me anyway.

Work found me on a whim: a friend’s friend needed tech support for a small property management company. Remote. Flexible hours. Troubleshooting printers, printers, and, for variety, printers. Software installs. People who said “I’m not good with computers” like it was a horoscope, and then thanked me when the thing finally printed their PDF lease agreement. The quiet of the job suited me. The problem sets were finite. No one minded that my office was a living room where a grab bar gleamed like a sobering truth.

The neighbors—two sisters who loved making too much food—started walking containers to my door every Thursday, as if the ritual itself could fix a spine. “We like cooking but hate leftovers,” they insisted, a lie we agreed to because the truth would embarrass us both: we wanted a reason to knock. We ate on my patio when the light went soft. They told me about their office dramas and their mother’s snoring and their plans for a dog they named before they adopted him. We laughed. It felt sometimes like a sitcom built by decent people.

I called the trauma therapist I’d waved away in the hospital. Melissa wore cardigans and had the quietest laugh I’d ever heard. She didn’t touch cliches; she touched the parts of me that no one had learned the language for. We circled the family until I was too tired of the orbit not to land. “So they never actually saw you,” she said after my fifth session, saying it like a meteorologist: statement of weather, not moral verdict. It hit with the force of a correct diagnosis. I cried. Not because it hurt—but because finally someone named the kind of hurt the wind had been singing about for years. If you are never seen, eventually you think you are unseeable. She gave me exercises in attention like they were physical therapy for the soul: notice what you notice when you make coffee; notice when your shoulders lift because a door knob looks high; notice the difference between anger that keeps you alive and anger that keeps you busy.

On Wednesdays, the rehab gym began to feel like a second job I loved more than any I’d been paid for. I learned how to transfer on bad days when even the good shoulder refused to vote yes; how to roll away from a fall without panicking; how to buy pants that didn’t hate sitting. Eric joked the way good friends do: dumb memes about biceps and chairs; the kind of encouragement that says, “You’re allowed to be light,” not “Be grateful.” He handed me a pair of custom forearm crutches with red handles I didn’t choose, and for some reason the color made me weep. “You earned these,” he said. It wasn’t graduation; it was admission.

I took fifteen steps without sitting down. They were weird, halting, sweating, full of upper-body bribe, but they were mine. If you’d told me those fifteen would mean more than any mile I’d ever walked, I’d have shrugged. You’d have been right.

A year passed while I wasn’t counting. The calendar marked things I didn’t: a judge’s signature turning my parents’ accounts into a trust fund I couldn’t feel good about, a letter from the state titled Order of Restitution that read like a sterile psalm, a new driver’s license that listed restrictions and a car with hand controls that turned me into the miracle I wanted at sixteen: independence. I practiced braking in an empty Sears lot like a teenager, giddy and a little wild. The first time I drove to the grocery store alone, I sat in the parking lot and cried with my head against the wheel because that stupid little trip tasted like winning a war.

I didn’t hear from my parents. I heard about them. A cousin texted, “They moved to Arizona. Gated community. Your mom posted a photo: ‘Fresh start in the desert, peace and sunshine.’” I looked up the photo. The bougainvillea was bright. Their smiles were concentrated. The caption did not mention me or Caleb or that their peace was bought with a medical trust they’d never touch. My chest didn’t do the old panic. It did something like a shrug. It felt like I’d left a meeting early and discovered everybody else politely kept talking to fill the time.

One Tuesday afternoon, the mail slot clacked and a letter slid onto the mat. Tampa return address, halfway house. Six pages. Neat print. Caleb. He listed deeds like inventory: the crawl space, the bike in the river, the birthday pranks, the laughter over trauma like it was confetti. “I wanted them to laugh at you, not me,” he wrote. “I don’t know how to stop being that guy.” He used words like accountability and repair. He did not ask for forgiveness; he scribbled the idea and placed it on the counter between us like a bowl of fruit I was free to ignore.

Melissa asked if I’d reply. I said maybe, which is a generous no. It’s not that I hate him. Hate would ask me to spend a heat I don’t have. It’s that a letter is a banana peel; you can slip on it if you mistake it for a meal. I folded it and tucked it where the warranty papers live. “Maybe someday,” I told her. “But not now—and maybe not ever.” She nodded and said, “Permission to not perform closure granted.”

In the rehab gym, a new kid wheeled in with eyes like a deer on the first day of hunting season. He was twenty-two, car wreck, angry that the world had the audacity to keep existing. I rolled up beside him and told him the truest thing I could think of: “It’s not over. It’s not the same. It is also not over.” I sat through his cussing and his tears and then showed him how to scoot an inch on the mat without believing in God. He asked how long it took before it felt less like drowning. I told him the truth: “You drown a little less every day you keep breathing.”

That was where I met Karen. She was a nurse whose forearms looked like they’d lifted more grief than any of us should have to. She had eyes that said, “I’ve seen it and I’m still here.” We traded sarcasm like baseball cards and coffee like currency. One day it was a lunch break in the hospital cafeteria; a month later it was dinner at a little place that hadn’t bothered to pretend to be hip. She liked to get straight to it. She didn’t flinch when my chair squeaked. She didn’t ask questions like I owed her an essay. She did ask what I was reading. We fell into a slow-thick thing, grownup patience we both respected. She saw me without the thick filter that had wrapped me in childhood. She asked me to let her help exactly as much as I wanted. I said yes and meant it.

On nights when it rained and the sky sounded like it was arguing with itself, Karen would swing by after a late shift with takeout and a six-pack. We’d argue about whether it was morally acceptable to put pineapple on pizza and watch high-budget garbage with high art lighting. She’d fall asleep with her head against my shoulder and I’d do the thing I used to do as a kid: make myself smaller so someone else could fit. Then I’d stop doing that, because she didn’t need me to. She told me once, matter-of-fact as a discharge summary: “You’re allowed to take up the space you take up.” I believed her.

One Saturday I took the bus to the rehab center not as a patient but as a mentor. The badge they printed me made my last name look like it might be useful. I sat with a man whose wife stood in the doorway with eyes like marbles on a floor. I told them the thing that kept me alive in the hard weeks: “You don’t have to be brave all the time. We only need ten seconds at a go.” Ten seconds to transfer. Ten seconds to digest bad news. Ten seconds to forgive yourself for not waking up full of fireworks.

Sometimes the anger lapped at my ankles like stubborn tide: the deck, the oil, my father’s voice telling me to get up, my mother’s whisper like a damp napkin pressed over my mouth. I let it wash. I learned not to confuse its presence with its control. Melissa taught me to label it and let it walk out the door without its shoes. It always came back. I always let it leave again.

I still work from the living room. Printer drivers break like promises. People send emails that say “thank u so much!!!!” with that many exclamation points. On good days, the chair feels like a chariot. On bad ones, it’s another translation I have to write on my own bones. On any day, I get to choose the music, and I never choose Bluetooth party anthems. That matters in ways I could not explain to the version of me who stood on that deck like a defendant.

I still see the nurse who held my hand that day at the party. Her name is Jess. She swings by the rehab center sometimes, because that’s who she is. I buy her coffee and then sneak a gift card into her pocket and she pretends not to see because accepting thanks is as hard as giving it.

Twice a week, I roll into the gym and listen to the clatter of hope. Once a week, I sit with Melissa and practice not apologizing when I exist. Every day, I leave a door unlocked in my heart for the version of me who still wonders if he could have avoided the party entirely. He drops in sometimes and says, “We did okay.” I agree.

Part V

The ending announces itself not with a cymbal crash but with a morning that feels like a room you’ve already lived in. Two years since the fall, a Tuesday that smelled like coffee and printer ink. The mail slot thumped. Another letter.

The return address said Tucson, but I didn’t need to see the names to know whose handwriting had dressed itself neat for inspection. I held it a time that could be called dramatic and then set it down. I poured coffee. I paid two bills, because the power company doesn’t care what day it is. Then I opened the envelope because I prefer to hold the truth in my hands rather than let it prowl my house.

Mom’s cursive had gotten wobblier, a tremor of age or nerves. “Dear Ryan,” it began. She wrote about the desert, about sunsets, about a church group where the ladies had welcomed her warmly. She wrote that she and Dad were volunteering at a food pantry. “We’re doing good things,” she wrote, which is a sentence nobody ever writes unless it is trying to make another sentence disappear. She didn’t mention the trust, the court, the things that had gotten them to the desert. She did say, “We miss you,” which is different from “We’re sorry,” but I suppose they rhyme under certain lights.

Dad added a short postscript: “Hope you’re working. Nothing worse than sitting around.” He had always been a poet of brute expectations.

I didn’t crumble. I didn’t hurl the letter into the sink and light it like a ritual. I folded it in half and then in half again, as if I was reducing it to scale. Then I slid it into the drawer where Caleb’s letter lived and realized I didn’t need to catalog any of it today.

Karen came over after her shift and watched me watching the letter. “What does it feel like?” she asked. The question contained no advice and that is a gift.

“It feels like an old door I closed creaking as if it might open,” I said. “And like I’m allowed to decide whether it does.”

“Do you want it open?” she asked.

I thought, not for the first time, of my father at the grill, my mother’s whisper, the oil that had turned the deck into a weapon. Of Jess’s hand around mine, the cops writing what we’d all preferred not to see, of Linda’s voice, of the check that cut a ramp into the concrete.

What I wanted wasn’t parents who wrote letters. It was parents who had once stopped the party. You cannot retrofit a past. You can only build a present that doesn’t require one.

“Not now,” I said. “Maybe not ever.” I braced for guilt. It didn’t come. In its place was a quiet the size of the Atlantic.

Three weeks later, the rehab center asked if I’d say a few words to a community group raising funds for adaptive sports equipment. The kind of event where you balance three truths: we need the money, we refuse pity, and we are allowed to tell the truth in a voice that reaches the parking lot. I wore the shirt that makes me look like a competent human and the shoes that slip on because I’m tired of fighting laces. I rolled up, breathed in the smell of folding chairs and cookies from a box, and aimed my story at the back row.

I told them about oil and gravity, about a brother who thought humiliation was a social currency convertible to love. I told them about a father who browned meat and called it a moral, and a mother who turned shame into home décor. I told them about a nurse who broke a party in half. I told them about doctors who refused to lie, and therapists who said “earned” like it was a sacrament.

I did not tell them that a million dollars still looks small when stacked against a damaged spinal cord; I didn’t need to. You could see the math in the eyes of every person who had ever tried to make a hallway wide enough for a wheelchair. I did tell them that the end of a family isn’t the end of a man. When I finished, the room was quiet for a second longer than is comfortable, then the kind of clapping that means we saw you, not the theater of you.

In the hallway, a teenager with freshly shaved hair and a chair so new it squeaked like a violin said, “My dad says I should just push through,” and his mouth flattened around the word should like a seed that wouldn’t crack. I told him the truth as I knew it: “You can push through a wall or you can cut a door. Doors last longer.”

At home that night, Karen fell asleep with her head on my thigh. The lamplight made the room gentle. My chair sat empty across from us, quiet and faithful, a creature at rest. I watched the window and made peace with the part of me that still wakes up from dreams in which I sprint.

Revenge had been a fantasy that tasted like chewing tinfoil. Justice had been a machine that built a frame. What stood inside that frame was not vengeance; it was a life I recognized. Not the one I’d imagined at twelve with a skateboard and impossible hair. Not the one I’d rehearsed at eighteen when I swore off holidays and then kept showing up anyway. A different one. One with red-handled crutches leaning by the door like honest punctuation. One with a ramp that a neighbor’s kid runs up with a giggle, then runs down, then up again because hills are fun. One with a woman whose laugh is not an argument and whose silences are not punishments. One with work that, in its smallness, frees me: plug this in, update that driver, smile because someone in three rooms over can print their lease.

On the anniversary of the fall, I didn’t commemorate. I did my exercises. I fixed a printer. I sent Jess a stupid meme and she sent me a photo of her dog wearing sunglasses. Karen and I sat on the patio with takeout pad thai, and I told her the story I hadn’t told anyone because it seemed too tiny to matter: when I was thirteen, I cried in the shower because Caleb had spent a whole dinner turning my voice into a joke, and Mom had smiled without hearing me. I decided then to speak lower, to be careful, to only call attention when I had a fact to deliver. “I am done speaking lower,” I said into the evening. Karen raised her beer. “To volume,” she said. We clinked.

In my inbox, a message from the rehab program director: “Would you consider running the peer mentoring program next quarter? Stipend attached.” I stared at it and felt the old reflex—who am I to—and then remembered how the nurse’s fingers had gripped mine, how Eric had handed me those red crutches, how Melissa had said, “They never saw you.” I hit reply. “Yes.”

The next morning I sat with a man who had lost more than I had—C6 incomplete, fingers that didn’t yet know how to love the world again. He told me his wife had left the hospital room the night before and said she was going to the cafeteria and then didn’t come back. He told me he didn’t blame her because who would sign up for this. I told him about the neighbors’ lasagnas and Karen’s eyes and Jess’s hand and Eric’s jokes and Melissa’s patience. I told him about the system, and the check, and how it feels to drive a car with your hands and realize you’ve been driving with your hands your whole life. I told him about the letter from Tampa and the letter from Tucson and the silence I had chosen. “You don’t have to decide today who you forgive,” I said. “You can put forgiveness in a drawer and go do your exercises.”

When I came home, there was a package at the door. No return address. Inside: a small wooden box, sanded smooth, almost too pretty. Inside that: a card with three words that must have taken labor to write: I’m so sorry. No name. I don’t know if it was from Caleb or Mom or Dad or some friend of theirs who had watched the party and only found their courage two years later. I put the box on the mantle for a week, then moved it to the drawer with the letters. Not because it didn’t mean anything. Because it did, and because meaning isn’t the same as medicine.

On a Sunday, Karen and I drove to the water, my hands steady on the controls while the bridge arced like a bold sentence. We sat where the marsh meets the stubborn river, the air salt and something green. Boats moved like thoughts I didn’t need to corral. “Do you miss them?” she asked, without angle.

“Sometimes I miss the idea of them,” I said. “The version where Dad looks up and sees me. Where Mom says, ‘I was wrong.’ Where Caleb puts the oil away and grows the hell up before the cops have to tell him how. But I don’t miss them the way a throat misses air. I don’t miss them the way a bruise misses fists to stay relevant. I miss them like you miss a song you liked before you learned what the singer did.”

“And your legs?” she asked softly, medical and human at once.

“I miss them like I miss being naive,” I said. “I miss the ease, but not the blindness. And sometimes, when I am selfish, I miss running. But then I realize I am moving farther now than I ever did when I thought you needed permission to move.”

She reached over and took my hand, fingers warm, no platitudes. We watched the water. We stayed.

At home that night, I unlocked my phone and typed a message to Caleb that I didn’t send: I got your letter. I see you trying. Keep trying. Then I deleted it. Not out of malice. Out of the knowledge that my recovery didn’t need to play counterpoint to his. If he is changing, let him learn the discipline of doing it without applause.

Before bed, I walked—yes, walked, braced and sweating—fifteen feet from the chair to the bedroom door and back. It’s not heroic. It’s homework. I hung the red crutches where I can see them because they are not trophies. They are reminders that the body’s alphabet is long and we can learn new letters after the old ones burn.

I turned off the lamp and the room softened. Outside, a kid shouted and then laughed like laughter didn’t belong to anyone else in particular. Somewhere, a neighbor’s grill popped and smoked, and for a second my chest clamped, old memory pulling at a scar. Then it passed. The smell of cumin from somebody’s late dinner cut through the past’s greasy insistence. I breathed in the present like a clean sheet.

This is the clear ending the story deserves, even if it refuses a bow.

There was a fall. There was a family that watched a son break and called it drama until the MRI said otherwise. There was a nurse who cracked the world open. There were cops who wrote facts like commandments. There was a prosecutor who made my house of glass admit it had always been shards. There was a lawyer who turned a deck into a check and a check into a ramp. There was a man who learned to move again not like he used to but like he needed.

And in the end, there is this: I wake up sore most mornings. I get up anyway. I work. I laugh at dumb memes Eric sends at 6 a.m. like people who bench press their own hearts. I roll down the hall and pause at the door to the patio where the light comes in like permission. I eat takeout with a woman who can find a vein blindfolded and still manages to find me. I ignore letters without hating the hands that wrote them. I teach people to cut doors in their walls. I live in a place made for me, by me, with help from people who saw me all along and people who learned to see me when they finally took their sunglasses off.

My brother’s “joke” left me unable to walk. My dad said I was overreacting. The MRI made them criminals. But none of that has the last word.

I do.

Part VI: A Door with No Handle (~1,250 words)

I didn’t plan to see my brother again. That wasn’t a vow so much as a habit—like finally learning to stop reaching for the top shelf when the glasses you actually use live in the drawer. Life felt like a layout I’d designed for my hands. Rehab, work, two nights a week of mentoring at the gym, Thursdays with the sisters next door, weekends that didn’t smell like apology. Then the email came.

Subject: Invitation to Speak — Restorative Track

The sender was the volunteer coordinator at a re-entry program downtown, one of the places where the court sent people who’d learned the hard way that impulse can be a wrecking ball. I’d done a few talks at shelters and clinics, so I assumed it was the usual: tell your story, pass the hat, remind people that compassion has rent to pay.

“We’re piloting a restorative program for harm-causers and survivors,” she wrote. “Low-pressure, trauma-informed. You’d speak to a small group about aftermath and accountability—no names, no cases. It would mean a lot.”

I asked Karen first. She didn’t blink. “If it helps you, do it,” she said. “If it hurts, don’t pretend it helps.”

Melissa raised an eyebrow I’ve come to trust. “What does your body say when you read the invite?” she asked.

“It sits up,” I said before thinking. She nodded like a coach timing my breath. “Then maybe go.”

The group met on a Tuesday evening in a community center that smelled like floor polish and dreams that needed better funding. Metal folding chairs in a circle. Coffee in a Cambro that had seen some things. Posters about communication taped slightly crooked to cinderblock walls: I-statements, reflect and confirm, name the harm without naming the person. Twelve people in the circle, three facilitators, and me.

I told the short version because the long one takes hours and lots of throats don’t have that kind of stamina. Oil. Laughter. Concrete. Delay. The MRI like a verdict. Then the slow bloom of a life not worse or better but staggeringly different. Red-handled crutches. Ramps. Choosing who gets to send me mail and who doesn’t. I kept my voice steady on purpose. Steady doesn’t mean numb.

A guy in a denim jacket coughed into his fist and said, “What would you want from the person who did it, if you could get anything?” I recognized the tremor in his voice: the world’s ugliest hope.

I thought about the wooden box with the card—no name—on my mantle, the letters in the drawer, the smell of that summer party even now if someone burns the wrong oil in a pan.

“I’d want them to stop needing me to tell them who they are,” I said. “I’d want their apology to be a life, not a sentence. I’d want to know the thing that broke in them isn’t looking for fresh glass.”

The denim guy nodded like a knot had loosened in his chest. Others spoke in turns. Somebody had stabbed a cousin during a fight neither of them remembered; somebody had driven drunk and survived when a stranger hadn’t; somebody had done a thousand small cruelties and was finally counting. We didn’t absolve. We inventoried.

Afterward, the coordinator caught me by the door. “Do you have a minute?” She had the careful tone of someone transferring a fragile object between shelves.

“We had someone on tonight’s waitlist,” she said. “He asked not to be in the room while you were speaking. I didn’t know if you—well, he asked if you might talk to him one-on-one, with a facilitator present. Only if you want. Absolutely no pressure.”

I didn’t ask for a name. I didn’t need to. The room got smaller, then bigger, then exactly the size of my lungs.

“Neutral space,” I said, a habit now, a boundary that had become a muscle. “No surprises. He leaves if I say so.”

“Of course,” she said. “We can use the counseling room. Ten minutes, tops, if you want it.”

I rolled down a short hall past bulletin boards bursting with flyers for GED tutoring and job fairs. The counseling room had two chairs, a small round table, and a window that faced a dusk-pink parking lot. The facilitator, a woman with a notebook and good posture, asked if I’d like the door open. I surprised myself. “Closed is fine.”

Caleb came in like someone had taken him apart and put him back together with mismatched screws. He’d lost the gym-rat gloss. Prison hair, yes, but also a face that had learned not to broadcast. He didn’t go for the bro hug or the joke. He sat. He looked at my hands rather than my chair. Points to him for that.

“Thanks for seeing me,” he said. The words were plain. No frosting.

“We have ten minutes,” the facilitator said softly. “Name your reason for being here. Speak in I-statements. Check in with your bodies.”

Caleb breathed like someone counting planes. “I…have a script for this, but I don’t want to read a script,” he said. “I wrote you a letter you didn’t have to read. I’m not asking for anything. I just—there’s something I should have said before, and I didn’t know how.”

I braced without meaning to. He noticed. “I’m not here to beg or to argue,” he added quickly. “Just to say a true thing.”

He swallowed. “I liked being the star,” he said, voice near a whisper. “It made me lazy. It made me cruel. When you fell, I laughed because that was my reflex—make it a bit, make it a bit, don’t let it be real. I keep thinking about the seconds between your words and anyone doing anything. Those seconds are my hell.”

I felt the room tilt—the way it does when a person finally sets down the heavy thing they were using as a chair. I waited. He let silence do its job.

“I don’t want you to fix this for me,” he said. “I don’t want you to forgive me so I can go sleep better. I wanted you to know I’m doing the work whether you ever talk to me or not. I’m in the meetings. I’m sponsoring two guys who only listen because jail makes you listen. I volunteer at the rehab clinic and wipe down the parallel bars until they shine. Nobody claps. That’s good.”

He reached into the pocket of his plain button-down and stopped, palms open, as if remembering the rules. “It’s not a gift,” he said. “Just a photo. Of the deck. I went back with the owner’s permission—he sold it, you know. We replaced the slippery boards. I paid for it with the only money I get to control now. It doesn’t undo anything. I just—” He laughed once, soft and awful. “I wanted to fix something I broke that day.”

I looked at the facilitator. She gave the tiniest nod: your choice. I held out my hand, and he set the photo on my palm like you place a sleeping child in a crib.

The image was ordinary. Sunlight. Wood that did not gleam like a threat. A new railing that would’ve caught me if it had existed then. I felt, unreasonably, like crying over lumber.

“My life is…good,” I said, because we owe true things their daylight. “Not easy. Not earned by you. Built by me and the people who saw me. I don’t need you in it to keep it standing.”

He nodded like he’d practiced that too. “I hope it stays good,” he said. “I hope I become the sort of person I’d want my daughter to meet.” He hadn’t mentioned a child before. He noticed my eyebrows and shook his head. “Not mine,” he said. “Someday, I mean. If I’m ever trusted with it.”

We sat for a time that wasn’t long but was heavy. The facilitator checked the clock with the gentle tyranny of schedules. “Last words for today?” she asked.

“I’m not ready for holidays or barbecues or any of that,” I said. “I don’t know if I ever will be. If you send another letter, I might read it. I might not. That’s not punishment. That’s triage.”

“Triage,” he repeated, like a student tasting a new word. “Okay.”

He stood. For a half second he looked like he wanted to touch my shoulder. He didn’t. Another point. He left the photo on the table. He left the room without looking back, which used to be his favorite move and now felt like respect.

I exhaled so hard the facilitator smiled. “How’s your body?” she asked.

“Steady,” I said, surprised to find it true. “No shaking.”

“That’s data,” she said. “Take the win.”

On the way home, the bridge wore its usual elegant curve. The sky was cinematic without trying. I put the photo on the passenger seat like a passenger itself. Karen was waiting on the patio with two beers and a face that said, Tell me or don’t; either way I’m here. I told her the short version and then the part about the deck. She looked at the photo and nodded. “That railing,” she said, practical as ever. “Somebody finally thought about falling.”

We ate leftover pad thai and made fun of the neighbor’s wind chimes, which sound like an argument between spoons. When the air cooled, we went inside and I did my fifteen-foot walk, braces biting in familiar places, sweat finding its old path. I hung the red crutches back on their hooks and felt the smallest lift in my chest, as if some invisible hook had removed a coat I didn’t realize I was still wearing.

Two weeks later, my phone buzzed with a text from an unfamiliar number: This is Mom. We don’t deserve to ask for anything, but if you ever need help with bills or appointments or anything, we can…we want to. We are learning how to be useful. No pressure. I stared at it until the words went out of focus, then I did the thing nobody in my family ever did when the stakes were high: I waited.

I waited a day. Then another. On the third day, I sent: I’m covered. The trust you tried to keep paid for that. I’m okay. Work on being useful where you are. Thank you for asking.

No other texts arrived. That felt like a mercy—an absence that knew its place.

At the rehab gym, a new group rotated in. I watched a man learn to sit upright without using his hands, the kind of victory that would never make TV but should. Jess stopped by with coffee and a smirk. Eric barked at me for bouncing my shoulders on dips. The sisters next door left casserole on my counter with a note that said, “We made too much AGAIN.” Karen stole my fries and pretended I hadn’t noticed.

On a quiet night, I took the photo of the replaced deck and tucked it into the drawer with the letters. Not as a shrine. As a receipt.

Sometimes people ask me if the story has a moral. Maybe it does. Maybe it has a hundred. But the one I keep handy, the one I can say without my throat going dry is simple: If your house is glass, build another. If the party is a performance, leave before the music needs you to clap. If someone says “just a joke,” listen for the oil in their voice and step off the deck.

And if you fall—because sometimes we do, sometimes on purpose, sometimes because gravity is a bully—let the MRI read the truth you were taught to ignore. Let the law do its job without asking it to be love. Let the nurses hold your hand. Let your body learn a new alphabet. Let your anger clock in and clock out without becoming your boss. Let your life get very, very specific: this ramp, this hinge height, this laugh in this room with these people who see you.

The other day, a kid at the center asked me if I thought I’d ever run again. I told him the only answer that felt honest: “I run every day,” I said, tapping the center of my chest. “Just not with my feet.”

He looked at my chair like it was a sports car. “Does it feel like flying?” he asked.

“Sometimes,” I said. “On a good hill with a tailwind.” He grinned. I grinned back. We both had places to be.

As for the door with no handle—the one that used to stand between me and my family—I finally understood it. I had kept expecting it to open if I knocked the right way. Turns out it wasn’t a door at all. It was a wall I had the right to not walk into anymore.

So I rolled past it. I turned the corner. I found another entrance. And I went inside.

Part VII

I didn’t think of it as rebuilding at first. That word felt too dramatic, too HGTV, too much like my life was a ruin that needed a bulldozer. But one morning, six months after the talk with Caleb in the counseling room, I woke up, wheeled into my kitchen, and realized: this is a house I built. Not of wood and drywall, but of people, rituals, habits, and a spine that still argued but no longer dictated the story.

The old family house—the brick-front colonial with Dad’s military stripes hidden in the lawn—was gone. Sold, stripped, reduced to a line on Zillow that read pending. In its place, I had an apartment that looked like it belonged to me. Ramps at both doors. Counters at the right height. Grab bars polished from use. A fridge that hummed low and reliable. Every time I rolled in after a day at rehab or work, I felt the difference: this house was not glass. No pretending it was flawless. No secret fractures. This one had walls that could absorb anger, laughter, silence. This one had room for me.

Karen noticed it before I did. One night, she looked around at my kitchen—pizza boxes stacked in the recycling, magnets holding dumb jokes on the fridge, red crutches leaning against the counter—and said, “Feels lived in.” It was the highest compliment she could give. Lived in meant safe. Lived in meant mine.

The rehab center asked if I’d take over the mentoring program full-time. Not just peer visits, but scheduling, training, being the guy who makes sure newcomers don’t fall through cracks. The stipend wasn’t huge, but it wasn’t about that. It was about the circle.

See, families like mine are stages. Someone is the star (Caleb). Someone is the audience (Mom). Someone is the director (Dad). Someone is the joke (me). The stage never changes; the roles never rotate. But in the rehab circle, nobody is a stage. We sit in a loop. Everyone speaks. Everyone listens. No one gets to be the permanent star, not even me. That’s what saved me: the circle.

I said yes. The first time I ran the group, I was nervous. But then I remembered Eric’s laugh, Jess’s hand, Melissa’s cardigan, Karen’s voice at midnight. I borrowed from all of them. “This isn’t about pity,” I told the new arrivals. “This is about honesty. If you want pity, go to Hallmark. If you want honesty, stay here.”

They stayed.

The drawer with the letters grew heavier in my mind, even though it only held three things: Caleb’s six-pager, my parents’ desert postcard, the photo of the rebuilt deck. Sometimes I wanted to throw it all out. Other times I wanted to reread every line, as if the past would change on the second draft. Most of the time, I left it alone.

Melissa asked once, “What does that drawer give you?”

“A reminder,” I said.

“Of what?”

“That I survived it. That it’s real. That I don’t have to prove it happened to anyone else.”

She smiled. “That’s not a drawer. That’s an archive.”

An archive, not a shrine. That felt right. Shrines are for worship. Archives are for remembering so you don’t repeat.

One Thursday afternoon, my phone buzzed with an unknown South Carolina number. Against my better judgment, I answered.

“Ryan?” A pause. “It’s Dad.”

His voice sounded smaller than I remembered. Not weak, exactly, but less armored. “I wanted to say—we saw your talk. The one at the fundraiser. Somebody put it online.”

I froze. My talk had been livestreamed for donors, but I hadn’t thought about who else might stumble across it.

“You sounded… good,” he said. “Strong.”

I waited. The old me would have filled the silence. The new me knew silence was a tool.

Finally, he said, “I don’t know if we’ll ever make it right. But I wanted to say I’m—” He stopped, as if the word itself were a weight-lifting bar. “—sorry. I didn’t see it then. I see it now.”

I thought of him at the grill, spatula in hand, ordering me to stand. I thought of him in the courtroom, not turning around. I thought of him watching me on a screen, safe in the desert, no burgers to flip, no crowd to impress.

“Thank you for saying it,” I said. Not forgiveness. Not a door swung open. Just acknowledgment.

He exhaled. “That’s all. Goodbye, son.”

He hung up before I could decide if I wanted to answer that last word. Son. Strange how heavy a single syllable can feel.

One night, lying on the couch with Karen half-asleep against my chest, she asked, “Do you think you’ll ever want kids?”

The question startled me. Not because I hadn’t thought of it, but because I had. Often. I pictured a child in a small backyard, maybe mine, maybe borrowed, running across grass that didn’t hide oil. I pictured teaching them how to fix a sink, how to use a wrench, how to say “no” without apology. I pictured making sure they never once had to wonder if they were invisible.

“I don’t know,” I said. “I used to think I’d be too much like him. Now I think… maybe I’d be the opposite.”

She smiled. “The opposite sounds pretty good.”

We didn’t make promises. We just let the idea sit there, like a guest at the table who might or might not stay for dinner.

There’s a hill near the rehab center. Not huge, but steep enough to be a challenge. One Saturday morning, Eric dared me to roll it. “Controlled descent,” he said. “Arms ready. Trust your brakes.”

I lined up at the top. My stomach twisted the way it had that day on the deck, right before gravity took over. But this time, I was in charge. My hands on the rims. My body braced. My eyes wide open.

I pushed.

The chair picked up speed. The wind roared in my ears. For a split second, panic flashed—falling again, hitting concrete, oil underfoot—but then my hands clamped the rims, brakes engaged, and the wheels hummed under control. I was flying and steering at once. Not falling. Choosing.

At the bottom, I laughed so hard I nearly tipped the chair. Eric clapped. “Told you,” he said. “That’s your marathon.”

The mentoring program grew. I started with six guys. By winter, we had twenty. Some rolled in bitter, some terrified, some cracked open. We didn’t fix each other. We sat in the circle and said true things until they stopped tasting like poison. That was enough.

One night, a man named Jordan—new, early thirties, car crash—looked at me across the circle and said, “How do you not hate them? Your family. Your brother.”

I didn’t answer right away. Everyone waited.

“I do hate them,” I said. “Sometimes. Some nights. But hate is like borrowing money from a loan shark. You pay interest forever. I put it in a drawer. I let the law handle the punishment. I let myself handle the living.”

The room went quiet. Then Jordan nodded. That was all. That was enough.

Two years after the fall, I bought a place. Small ranch, one story, wide hallways, yard that needed work. Karen helped me pick paint colors. The sisters next door brought champagne. Eric and Jess showed up with tool belts. Melissa came by with a housewarming gift: a sign that read This House Is Not Glass in black paint on rough wood.

I hung it above the doorway. Every time I rolled in or walked with braces, I saw it. A reminder. A vow. A truth.

The new house wasn’t perfect. The plumbing moaned. The roof leaked in heavy rain. The ramp needed reinforcement. But it was mine. Built on concrete that didn’t crack under oil. Filled with people who saw me, who stayed, who laughed without cruelty.

Sometimes I thought about Caleb. Sometimes I thought about Mom and Dad in their desert house. Sometimes I thought about the deck. But those thoughts didn’t own me anymore. They were artifacts, not anchors.

I had a new house now. And this one wasn’t glass.

Part VIII

Time doesn’t heal, not really. It remodels. It takes the wound, leaves the scar, and builds new rooms around it until you stop stubbing your toe on the same damn corner.

Three years after the fall, my life looked less like a recovery and more like a rhythm. The mornings had order: coffee, stretches, chair check. Work calls started at nine. Rehab on Mondays and Thursdays. Mentor circle Tuesday nights. Fridays with Karen, usually dinner out if she wasn’t on shift. Saturdays sometimes meant a bus to the water, where the marsh grass bent like it knew something I didn’t.

The anger wasn’t gone. It still flared like a bad nerve, sharp and quick when I thought of Dad’s voice or Mom’s whisper. But now it passed faster, like a storm that doesn’t linger. I’d learned not to chase it. Let it rain, let it move on.

The drawer grew heavier, not with paper but with meaning. Caleb sent two more letters. Shorter this time. One about a guy he was mentoring inside, teaching him how to read. Another about his release date.

I read them. I didn’t reply. Melissa said, “That’s still a choice. Choice is power.” She was right. My whole life I’d been told choice was selfish. Now choice felt like oxygen.

Then, a letter from Mom. Not flowery this time. Just a single page.

Ryan, we’re proud of you. We should have said it years ago. I see that now. Love, Mom.

I read it three times, waiting for the catch. It never came. Still, I folded it into the archive. Proud doesn’t erase. Love doesn’t fix. But it was something. And something, in our family, was rarer than rain in the desert.

One spring night, Karen looked at me across the patio where my new wind chimes played a song less annoying than the neighbor’s. She said, “You know I love you, right?”

“Yeah,” I said, not flinching this time.

“Then let’s build something together. Not someday. Now.”

She wasn’t talking about a wedding, though we did that later in our own quiet way. She meant a life. A shared one. She moved in. Brought her plants, her mugs, her ability to make the place feel less like a rehab showroom and more like a home.

The first time I rolled into the bathroom and saw her toothbrush beside mine, I laughed. Not because it was funny, but because it was proof. Someone wanted to stay.

The mentoring program exploded. We went from twenty regulars to nearly fifty. I got calls from other centers asking me to teach them the model. “It’s not complicated,” I said. “Make a circle. Tell the truth. Let people stay.”