Part I:

They stood on my doorstep as if nothing had happened. Ten years gone, faces older but recognizable—the same slate-gray eyes we inherited from our father, the same brittle arrogance set like concrete around their mouths. My brother and his wife. The air was sharp that morning, frost pulling crystals out of the breath we exhaled, brittle enough to slice skin. I opened the door wider—not out of welcome, but curiosity.

They didn’t lead with apology. They led with a claim.

“She’s our daughter,” his wife said, soft, almost rehearsed. “We’re here to take her.”

For a second the world shifted, as if the house itself exhaled through its studs and wiring. Upstairs, the cheap baby monitor I’d never gotten around to replacing hummed with a faint, even static—the sound of a machine guarding fragile sleep. My niece, Lily, had been eight the first time I saw her picking through a grocery store dumpster for bruised pears; now she was eighteen, knobby knees smoothed into adulthood, but the shadows of those years had never quite left her eyes. Ten years I had carried her through fevers and night terrors, through school meetings where teachers called her “resilient” like it was a trophy instead of a scar. I’d counted the seconds during seizures that never came again but nonetheless haunted every small silence. I’d fielded calls from social workers, court clerks, doctors who said “trauma” the way a mechanic says “bent axle,” like it could be replaced.

Ten years since my brother and his wife had left Lily in the mountains like unwanted cargo. Ten years since they’d named what they did “mercy,” said the words “no future” while staring past the child who was not an infant, not a burden but a person. Ten years since I’d been the one to answer the phone from a waitress who’d taken pity and dialed the only number she found scribbled on a receipt, my number, and I’d driven up through fog like a lace veil, headlights carving two thin tunnels through breath-white air, and found Lily half-conscious on a picnic table, abandoned among toddlers’ shoeprints and beer-bottle caps. Ten years since I’d wrapped her in my coat and breathed on her chattering teeth and sworn things I didn’t know how to keep yet.

And now they wanted her back.

The audacity was almost surgical in its precision. No hesitation, no scent of shame. A claim and a demand, the words like a notice nailed to my door.

I felt my jaw tighten, the kind of tension that makes molars into fault lines. I said nothing. Silence is more dangerous than words; it gathers weight.

My brother’s smile was thin, brittle as cellophane. His wife’s hands trembled, though she tried to mask it with flats and black slacks and a blouse the color of expensive cream. People who fool themselves always dress up their lies. They thought time had eroded memory, thought I had forgotten the storm-slick road, the clack of my hazards while I ran to her, the cooing sound she’d made like a bird too tired to lift its head. They thought wrong.

Behind them the neighborhood performed normalcy: a golden retriever barking at a school bus, a kid belly-sliding down frozen grass, the mail carrier with the gait of a metronome. The world was indifferent to the reunion in my doorway, the universe too large to bend for our small disaster.

“Come in,” I said finally. Not because I wanted them near Lily, but because I needed to see their eyes against my walls, needed to watch them read the life they had erased.

They stepped over the threshold and did that small shuffle humans do when they move from public air to private space. Their eyes scanned the quiet order I had built around survival: the metal shelves with labeled bins—NEBULIZER MASKS, SPARE BATTERIES, SCHOOL FORMS, LEGAL; the thick folder of medical records I kept out of stubborn pride, even though we hadn’t needed the emergency room in years; the framed photographs lined along the hallway like a spine. Lily growing year by year: the picture from fourth-grade field day with grass stains on her knees; eighth grade with a science fair ribbon held like a sword; the photo in front of the high school with her hair in braids and her eyes brave and terrified all at once. They avoided those frames the way a thief avoids mirrors.

“Coffee?” I asked, the false politeness of ambush.

“Yes,” said my brother, as if we were starting over, as if coffee could undo anything. “She still likes cinnamon?” he added, clumsily, and shut his mouth when he saw my face.

While the kettle yowled, my mind unspooled the days that had led to this one. The social worker the year after I got Lily had warned me: People don’t stay gone forever. They shop for redemption when life finally hands them a bill. It took them a decade to find a coupon.

The visits started like weather. First a text from a new number I ignored. Then a letter on heavyweight paper—his wife’s signature in loops, my name square. “We’ve changed,” it said. “The past was complicated,” “We’re in a better place,” “We want to reconnect.” No mention of the dumpster or the picnic table. The second letter included a photograph of them on a boat, all windbreakers and capped teeth and sun. I fed that into the shredder and cleaned the little white confetti for weeks.

I let them visit. This is where I need you to understand me: I am not cruel. I am a man who knew a court would want to see that I had tried. I am a man who understood paper holds power no voice can find. So I let them come to the porch for twenty minutes on Sundays when Lily was downstairs and my neighbor across the street, a retired cop with a spectacular mustache and a love of binoculars, just happened to be trimming his hedge. They asked my niece how school was going with voices the color of skim milk. They said “proud” a lot, as if the word could crawl backward in time and button up what they had left undone. Lily watched them the way kids watch magicians: with disbelief and a dash of pity. When she excused herself to “check on the muffins”—what muffins?—they sat there brimming with hope as flimsy as soap bubbles.

I worked in the background. I am an EMT by paycheck and a mule by temperament. I dig, I carry, I endure. I dug into their lives the way my old man used to dig fence posts—measure twice, set the line straight, sink your weight and do not stop. County records, property transfers, corporate filings. I traced the years they had vanished. Found the LLC my brother’s wife had used to tuck her money after the settlement from the company that fired her for “cause.” Found the 4-bedroom colonial in a town where every school brochure is printed on premium matte. Saw their trip to the Vineyard written into a real estate blog, their faces standing in front of a door with a brass knocker shaped like a whale. Not a whisper of Lily anywhere. Not a whisper of a lost daughter in the past or present. Just a clean brand new story, shined to blind.

On paper I built a wall. I’d already won custody years back when they failed to appear; default was a word that left a heavy taste, but it was mine. Now I inventoried every doctor’s note and school form, every signed permission slip, every photo with a date stamp, every letter postmarked from them that mentioned nothing of her existence. The lawyer I met with had pale hands and liked to begin sentences with “Ordinarily.” Ordinarily, parents retain standing. Ordinarily, blood buys entry. But there is always the un-ordinary. Abandonment. Ten clean years of absence. My file was meticulous enough to win a prize in an OCD convention. The lawyer said I had done his job for him. I heard the awe in his voice and didn’t like it.

“Where is she?” my brother’s wife asked now, turning her empty mug in her palms as if to conjure tea leaves. Her eyes skittered around the living room. She stared anywhere but at Lily’s framed certificates, the photos of her camp counselor group, the goofy shot in which she is wearing a crown made of aluminum foil because her best friend insisted every Tuesday in July was Coronation Day.

“Upstairs,” I said. “She’s sleeping. She works late at the diner on Saturdays.”

“You let her work? At a diner?” His wife’s voice latched onto the word as if it were a swear.

“Yeah,” I said. “She likes it. She likes people, tips, and the way her feet ache because it means she earned something.”

My brother tried on a smile. “You taught her that.”

“She learned it,” I said. “I just provided a roof and a reliable car.”

Outside, a plow scraped the street, a snowplow against asphalt, the sound of a can opener on the sky.

The truth is this: I’d been ready for this moment since the first Sunday they came. I knew what they were here for. Not Lily, not really. Something else. Money. Reputation. There was a whisper—not even a whisper, a rumor’s shadow—that his wife was prepping a run for the school board on a platform of “traditional family values,” photogenic in a cardigan, the living-room set behind her. Their doorbell would ring and Lily’s absence would prick at someone’s question, a nosy neighbor with a dinner-party memory. “Didn’t you have a daughter?” someone would say, a fork tapping a wineglass. “What happened to her?” And my brother’s wife would blink and stammer and then find a way to say: “We got her back. We made it right.” The redemption you serve to yourself on a plate you abandoned years ago tastes like caviar. They had come to my house with a hunger they mistook for love.

I had waited for a particular envelope. Not because I needed it; I had everything already, the hard facts of abandoned months. But paper is a sword that cuts through lies. The envelope arrived in a stack of coupons and a flyer for a karate studio claiming to build “confidence and core strength.” When I slid the door knife under the flap, the edges rasped like winter weeds. The report was clean, clinical: genetic proof, legal standing, unbreakable. It was insurance against their story.

I waited until dinner a week later. Lily sat between us, eating quietly, unaware of the war hovering over her plate like steam. I’d made roast chicken and green beans. She liked to press each green bean with her fork until it snapped, neat like a pencil.

I slid the envelope across the table. My brother opened it, scanned the pages, and froze. His wife leaned in, face blanching, lips parting with a soundless gasp. The words had weight that landed on their shoulders like sacks of concrete.

“You abandoned her,” I said, finally breaking the silence. My voice was low, controlled, the tone of a man giving instructions in a crisis. “And by law, by paper, by every piece of evidence that matters, you lost her.”

Their throats constricted around denials that tasted bitter on their tongues. Their voices rose, pleading, desperate. Tears finally came, but not for Lily. They cried for themselves. For the erasure of the shiny narrative they’d polished. My brother’s shoulders hitched as if someone were yanking him on strings. His wife gripped the edge of the table hard enough to blanch her knuckles.

I didn’t flinch.

“You call her your daughter,” I said, “but she calls me father.”

The words struck harder than any scream. In them were sleepless nights, scraped-knee marches to school, the math of every late rent I juggled, the quiet victories of science fair ribbons and driving test passes, the small laughter of Tuesday Coronations. I watched it break them. The realization that absence had erased their claim and replaced it with mine.

Ten years of absence cannot be undone by sudden desperation. You left her to fend for herself on a mountain in the dark and then decided the summit of your moral climb would be returning to a warm dining room to collect her like a trophy. The audacity would have been hilarious if it weren’t vile.

Lily looked between us. She’s always been skilled at reading rooms. She knows when to step into the light and when to hover in the doorway like a question mark. She touched the edge of the envelope with one finger, then removed her hand. “I’m going upstairs,” she said softly, not asking permission so much as giving me room. “I have a quiz tomorrow.”

“Go on,” I said. It is a particular miracle to tell a person to go upstairs to safety when they have spent a childhood within arm’s reach of a cliff.

When the door closed behind her, I looked at them one last time. “You don’t get to rewrite history,” I said. “You don’t get to rewrite blood.” I stood, walked to the front door, and opened it. Winter poured in. Cold cleans everything. “Leave.”

They walked into the dark, broken silhouettes fading against the streetlights. For a long time I stood at the threshold, listening to the silence they left behind. My heart was steady. My hands were still. The storm had passed—or at least this one had.

That was last Sunday.

This morning, as the kettle sang again, I thought of the first time Lily said “Uncle, it hurts.” She had been eight, a feral little flame in a sweatshirt two sizes too big. I had found her behind the grocery store where the dumpsters were chained to concrete. She was scattering coffee grounds with her sneaker, hunting the pears the clerks tossed for being too soft. Her left cheek wore a constellation of yellowing bruises. She didn’t cry; crying is a luxury. She held a pear like a newborn and stared at me as if deciding whether I was a person or a problem.

“Uncle?” she said—testing the word like a stair. “It hurts.”

I had crouched so we were eye level, the asphalt pressing its chill into my knees. “Where?” I asked.

She touched her ribs, then her throat, then—without meaning to—her heart.

I nodded as if she’d answered a math problem correctly. “Okay,” I said. “We’re gonna fix what we can and carry what we can’t.”

A decade later, the math was the same: fix what we could, carry what we couldn’t. The bruises had faded. The dumpster was a memory. But hurt is not a thing you bury and forget. It is a land you learn to walk without spraining your ankle.

That morning, after my brother and his wife left my doorway, I turned off the kettle, poured the coffee I no longer wanted, and climbed the stairs. Lily had fallen asleep again, one hand tucked under her cheek. On her bureau was the photograph she’d taken the day she got her learner’s permit, her grin too big for her face. Next to it, she’d propped a postcard of the Tetons I’d bought at a thrift store—the mountains like a row of patient, dangerous teeth. We’d never been; vacations tend to be for people with more money and less paperwork. But some mornings we’d turn the card over and draw a map of how we could get there: Route 80, the big sky unspooling, the diner coffee in truck stops, the two of us singing badly to old songs.

Downstairs, my phone buzzed. A text from my neighbor with the mustache: Saw them leave. You okay?

I typed back: Yeah. Weather’s clearing.

He replied: Snow tomorrow, they say.

I looked out the window. The plow had left a tidy ridge like a stitched seam down the street. Kids had pressed mittened hands into it and left hieroglyphs. Somewhere a dog was negotiating terms with a squirrel. The world, insistent in its dailiness, asked me to join it.

I sat at the kitchen table and opened my notebook. Not the legal one—the ordinary one where Lily and I kept a list of small things we wanted to do this year. She had written: Learn to change a tire. Make cinnamon rolls without burning the bottoms. Save $500. Read a book I’ve never heard of. Tell Uncle the rest of the story about the mountain when I’m ready.

My pen hovered, then found the line I’d left blank at the bottom. I wrote: Buy snow chains. Head west in June. Mountains—not as memory, but as place.

Before I closed the cover, I added a line I had never thought I’d allow myself to write: Tell the truth to someone who deserves it.

I closed the notebook and stood. The house made the small well-fed sounds of winter: the moan of heat moving through metal, the click of pipes, the whisper of settled snow sliding from gutters. Somewhere upstairs Lily shifted, then settled. The card of the Tetons on her dresser glinted like ice in thin sun.

Tomorrow, there would be more paperwork. The lawyer would file things I didn’t know the names of. There would be a day in court maybe, or maybe they would slink away under cover of their own pride. My brother and his wife would write me one more letter, I suspected, the words “forgiveness” and “family” trotted out like circus ponies. I would shred it cleanly, feed the white strips into the blue bin, and carry the recycling out to the curb, where the universe collects what we can no longer use.

But that was tomorrow’s weather. Today’s forecast was simple: make breakfast, text my boss I’d be late, and be there when Lily woke up and squinted against the light and said, “Do we have any cinnamon?”

“We will,” I practiced saying, and smiled at how ordinary it sounded in my mouth.

Part II:

The night after I told my brother and his wife to leave, silence became something alive in the house. It wasn’t the peaceful kind that settles in after a long day—it was heavy, coiled, almost waiting. Lily had gone upstairs without asking questions, but I knew her well enough to see the wheels turning. She might not have said it yet, but she’d want answers. Children—no matter their age—want to know the truth, even if they fear what it looks like.

I sat in the living room with the TV on mute, flipping through channels just to watch the colors change. My mind was running through everything I’d said, everything I hadn’t. The truth is, words don’t always seal wounds. Sometimes they just reopen the ones we’ve worked so hard to bandage.

When the floorboards creaked overhead, I knew she wasn’t asleep. Lily has always walked light, almost like she feared pressing too hard on the earth, but I’ve lived long enough under the same roof to hear the difference between restlessness and sleepwalking.

She came down a little after midnight, wearing an oversized hoodie, her hair tied back, eyes wide awake. She stood at the bottom of the stairs like she wasn’t sure if she had permission to enter the room.

“Uncle,” she said, voice careful, “why were they here?”

I muted the TV. I wanted to tell her she didn’t need to know, but lies rot faster than truth. “They wanted to see you.”

Her lips tightened. “No. That’s not it. They wanted something.”

She’s sharper than I was at eighteen. I was still trying to figure out how to make rent and not burn pasta. She’d seen enough of life’s underside to know when people are dressing up greed as love.

“They think they can walk back into your life,” I said slowly. “But they left you. That doesn’t just disappear.”

Her eyes darted to the framed photos on the shelf. One of them was from the year she turned twelve, a cake we baked together with frosting so thick it dripped down the sides like melting snow. She stared at it as if reminding herself that those years were real, that they weren’t just filler between abandonment and now.

“They looked at me like…” she hesitated, chewing her lip. “Like I was a stranger.”

I leaned forward, elbows on my knees. “That’s because, to them, you are. They didn’t raise you. They don’t know your laugh when you get it wrong in karaoke, or the way you cry at animal commercials, or how you eat the crusts last because you say it’s like saving the best part of a sandwich.”

Her eyes flicked to mine, shining. “But you do.”

“Yeah,” I said. My throat tightened. “I do.”

We sat in that silence together for a while, not heavy now, but steady, the kind that builds bridges instead of burning them.

The next morning, I woke up earlier than usual. Snow had fallen overnight, blanketing the world in white. I made pancakes, the kind Lily liked—crispy on the edges, soft in the middle. She came down yawning, her hair a mess, but she smiled when she smelled them.

“Cinnamon?” she asked.

“Always,” I said.

For a while, we let ourselves pretend the world outside didn’t exist. But pretending only lasts so long. After breakfast, she pushed her plate away and asked, “What happens now?”

I’d been asking myself the same question. My brother and his wife weren’t just going to slink off into the dark. People like them don’t know how to accept defeat. They’d push, they’d threaten, maybe even sue. They had money and lawyers and the kind of entitlement that makes people believe they can bend the law the same way they bend promises.

“Now,” I said, choosing each word carefully, “we live our life. Like we always have. And if they come back, we’ll deal with it.”

She studied me, the way she does when she’s measuring truth against comfort. Then she nodded, as if satisfied.

But I knew this wasn’t the end. This was the silence between storms.

That night, when she was in bed, I pulled out the files again. The records, the photos, the notarized statements from the social worker who’d once called their disappearance “willful neglect.” I stacked them neatly, double-checked the locks on the doors, and set my phone beside me on the couch.

Outside, the snow kept falling, quiet but relentless, like time itself.

And in my chest, the storm I’d held back for ten years stirred again, whispering: This isn’t over.

Part III: Paper Weather

The week after the doorstep standoff, the sky decided to stay the color of pencil shavings. Snow came in stingy flurries, then quit just long enough to let the roads turn to slush and lie. I kept working my routes on the ambulance—people still choke on steak in February; hearts still forget their jobs—and when I wasn’t on shift, I stacked paper. Paper is the weather of American life. Draw the blinds, tape the panes, and it still finds the cracks.

Lily went to school, then the diner, and came home with her ponytail smelling like coffee and fryer oil, which I’ve decided is one of the scents of survival. I made a habit of standing at the sink when she came in, letting her clatter a story across the kitchen island—who stiffed what table, what song played three times in a row on the radio, how Ms. Ortiz caught Benji cheating with his phone and made him read a poem about gravity in front of the class as penance. We talked about small things so the big thing wouldn’t swallow the room.

On Wednesday, I met with the lawyer again. His office was in a handsome brick building that used to sell suits to men who worked at factories that don’t exist anymore. Now it sells words. The receptionist had eyelashes that could swat flies. The wall art was black-and-white photos of streets that had been renamed three times. The conference table looked like a boat, dark and polished, something you could cross a river on.

“Ordinarily,” he began, like always, warming his hands over the hearth of the predictable, “parents retain significant presumptive rights. But we are not dealing with the ordinary. Abandonment isn’t a bruise; it’s an amputation.”

He slid a stapled packet across to me. “We’ll file to affirm your sole legal custody and to enjoin any contact without your express consent. They will counter that the child—”

“She’s eighteen,” I said. “In June.”

“Then they will counter that the young adult wishes reunification.” His eyebrows climbed like tired caterpillars. “Do we know if she does?”

“She doesn’t,” I said, and felt the truth settle, heavy but easy. “She’s not a prop in their redemption arc.”

He nodded. “Good. Still, it helps to have third-party testimony. Teachers, doctors, neighbors.”

“I’ve got statements,” I said. “Ms. Liang from ninth-grade English—the one who let Lily write about dumpsters and mountains without making her soften the edges. Dr. Patel from the clinic—she’ll attest to regular care, no neglect. And my neighbor Dave, who trimmed his hedge on Sundays for a year like it was his religion.”

“Get me affidavits,” he said, tapping the packet. “The more paper, the easier the weather.”

He glanced at a file to his left and frowned carefully, like a man who hates to wrinkle a suit. “One more thing,” he said. “I got wind—unofficially—that your brother’s wife is… ambitious. There’s talk of a school board run.”

“Figures,” I said. “Nothing like education to dust sugar over a bitter past.”

“She’ll want a photograph,” he said. “A smiling one.”

“She won’t get it from my house.”

He folded his hands, a man who liked puzzles solved with patience more than force. “Then we prepare for their next move. When redemption fails at the door, it knocks through other channels.”

He was right by lunchtime.

I found the envelope tucked under our doormat when I came back from the grocery store with a gallon of milk and a bag of rice big enough to qualify as a pet. The return address wore the tight print of an agency logo. The acronym on the corner made my stomach go cold in that familiar, professional way: CPS.

“Here,” Lily said over my shoulder, mid-step into the living room with her backpack sliding down her arm. “What is it?”

“A welfare check,” I said, already reading. A complaint had been filed—anonymous, of course. Concerns cited: inadequate medical care; unstable environment; interference with familial reunification.

“I take my meds,” Lily said. “I haven’t had a seizure in forever.”

“They’re not talking about your body,” I said. “They’re talking about mine.”

She understood. She always does.

The next afternoon, a social worker named Halley—mid-30s, warm eyes, a sensible bun that looked like it had been redone in the car—sat at our kitchen table and drank the tea I offered. Her pen moved, but not in the frantic way of people trying to catch a lie running. There are two breeds of social worker, in my experience: the box-checkers and the listeners. She was a listener.

“I’m sorry to put you through this,” she said at one point, glancing at the file I had produced, which looked like an encyclopedia volume titled The Last Ten Years We Actually Lived. “We’re obligated to investigate any report, but not obligated to believe it.”

“I appreciate that,” I said. “And I respect the work. I’ve seen the other side. I’ve knelt on floors sticky with beer and tears, trying to convince a kid to come with us because the man in the apartment promised he’d be gentle if she didn’t make him angry. I know you’re not the enemy.”

Her pen paused. “EMT?”

I nodded. “Long time.”

We walked through the house. She looked inside the fridge, inside the cabinets. She checked the smoke detectors, the water heater. She glanced at the photos, and I watched the tiny recalibrations happen—the math of a story told in paper and wood and glass. In Lily’s room, the bed was made, the desk cluttered with schoolwork. On the bulletin board, at the center, a note I’d written and she’d pinned up like a flag: Proud of you, every day, every way.

“Can I talk to Lily alone for a bit?” she asked gently.

I nodded, stepped onto the porch, and texted Dave across the street: CPS visit, all good. Just part of the dance.

He sent back a mustache emoji and a thumbs-up, which is the language of old men with binoculars.

When Halley left, she shook my hand. “We’ll close this out,” she said. “There’s no cause. The report reads vindictive.”

“Thank you,” I said, and meant it.

“They’ll likely try other angles,” she added. “If there’s anything escalatory—media, harassment—document, document, document.”

I almost laughed. “Lady,” I said, tapping the stack on the table, “I document in my sleep.”

That evening, we celebrated the bureaucratic victory not with champagne but with the closest thing Lily and I have to ritual: changing a tire. I’d promised her we’d check it off our list before the thaw. We took the jack and the lug wrench out to the driveway as the sky smeared itself into violet. I showed her how to break the lug nuts before the lift, how to set the jack on frame, not sill. She grunted, weight behind the wrench, then laughed when the nut gave and her shoulder nearly kissed the fender.

“Feels good,” she said.

“Work always does.”

When the doughnut was on and the bad tire was in the trunk, Lily wiped her hands on a rag and looked at me with a seriousness that made her look five and thirty at the same time. “If they get mean,” she said, “we can get mean, too.”

“Maybe,” I said. “But I’d rather get thorough.”

She nodded like a soldier taking orders she agreed with. “Thorough is mean with better manners.”

We ate grilled cheese by the sink and flicked crumbs to the dog we don’t have. Lily told me about a book Ms. Liang had assigned. “The author keeps pretending he doesn’t care,” she said, “but the sentences give him away.”

I thought about my brother on my doorstep, his smile like Saran Wrap stretched too tight. “Yeah,” I said. “Words can be snitches.”

Friday, the first new moon of February, the lawyer called to say the hearing had a date. Two weeks. “Preliminary,” he said. “But it’s where we spike the tent.”

“Perfect,” I said, and felt a calm roll in, measured and heavy like tide. Two weeks is enough time to sharpen.

I asked Lily if she wanted to come to the preliminary. She watched the steam from her mug of cocoa twine itself into a question mark. “Do I have to talk?”

“No,” I said. “Not unless you want to. It’s mostly paper arguing with paper.”

She nodded. “Then yeah. I want to look at them when they try to sell a story.”

That Sunday, she didn’t go to the porch when they texted. She let the phone buzz upside-down on the counter while we made cinnamon rolls that burned on the bottoms anyway and filled the house with sugar smoke. There is a kind of small rebellion that tastes like frosting from a spoon.

They tried the media next. I came home from shift on Tuesday to find a reporter standing at the end of our driveway, her coat too thin for the air, a cameraman wearing a hat with earflaps like a cartoon trapper. She had the look of someone who isn’t sure if she’s being a nuisance or a hero.

“Mr. Dalton?” she called, respectful in the way of people who want something. “I’m with Channel 12. We heard about a family reunification story. We wanted to get your comment.”

I kept my keys in my hand because keys are small courage. “There’s no story here,” I said. “There was a child left behind and an adult who didn’t leave. That’s not news. That’s Tuesday.”

“We’d like to give both sides a platform.”

“Tell your producer that ‘both sides’ is a phrase that gets children hurt,” I said. “And that if you want the truth, it’s in the court filings, not my driveway.”

The cameraman shifted, disappointed. The reporter nodded, to her credit, like a student who has been corrected in public and decides to thank the teacher anyway. “If you change your mind,” she said.

“I won’t.”

Lily watched from the window, her breath fogging the glass. When they left, she opened the door. “That was—” she started.

“Thorough,” I said. She grinned.

Two days before the hearing, I took Lily to see Dr. Patel for a routine physical we could have done next month but didn’t. Dr. Patel is in her early forties, humor like lemon zest, sharp and bright. She’s one of those doctors who leans in when kids talk, makes room for their sentences to finish. After the blood pressure cuff sighed and the scale told us the same story it always tells, Dr. Patel turned to Lily and said, “How’s your head?”

“Quiet,” Lily said. “Like a dog that got tired of barking.”

“And school?”

“Loud,” she said, “but the good kind.”

Dr. Patel looked at me. “You’re doing fine,” she said, then corrected herself: “You two are doing fine.”

On the way out, Lily stopped at the corkboard in the lobby—the one with flyers for babysitters and guitar lessons and a lost orange cat named Pumpkin. She pinned a small index card she’d written in block letters: If you need help, ask. There is almost always someone who will say yes. She stared at it a second, considering whether hope looked corny in public, then squared her shoulders and walked out into air that bit and promised spring at the same time.

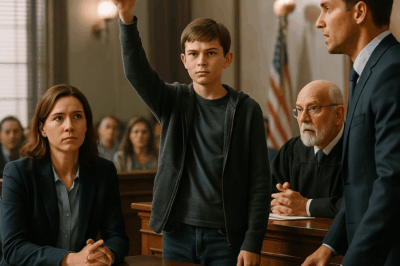

The hearing happened on a Thursday morning that could not decide if it was thawing. The courthouse smelled like old wood and grudges. We walked past a man arguing with a vending machine and a woman rocking a crying baby whose wail hit a frequency I remember from calls that ended with forms and phones and coffee you don’t taste. In the courtroom, a clock ticked loudly enough to be rude.

My brother and his wife sat at their table in clothes you wear when you want a judge to think you iron virtue. Their lawyer was new to me: expensive hair, shoes that made no sound. Across the aisle, my lawyer set his file down like a chess player setting a knight and said “Good morning” the way you say it to a storm you’ve decided to drive into.

It was preliminary, so there were no fireworks yet—just motions and exhibits, timelines and tones. Their lawyer used words like “reunification” and “healing,” words that should not be told to do such heavy lifting. He held up a photograph of the three of them from a decade ago: a picture in a pumpkin patch, everyone in hats, everyone pretending cold is fun.

My lawyer did not talk about pumpkins. He talked about dates. He talked about ten years of absence clean enough to do surgery with. He talked about the motion to enjoin contact without consent. He talked about the CPS visit that had been closed in a day and stamped with words that were polite synonyms for “spite.” He talked about Lily’s grades, about medical adherence, about employment, about a hundred little facts that are more beautiful than adjectives.

At one point, the judge—a man with a nose like a doorknob and eyes that lived in the realm of practical—asked if the “child” wished to speak. Lily stood. She did not look at them. She looked at the judge. Her voice was steady like a part of a song that knows it’s the chorus.

“I’m not the past,” she said. “I’m me. I live here. I work. I have a quiz next week I don’t want to fail. I don’t need saving. I needed saving a long time ago and didn’t get it. I have a father. He’s not the man who gave me his last name. He’s the man who gave me a car with a spare tire and taught me how to use it.”

The courtroom exhaled. Even the clock on the wall seemed to pause before it ticked again.

The judge nodded once. “Thank you, Ms. Dalton.”

Their lawyer hurried to reassert the ritual. “Your Honor, we respect the young woman’s feelings, but feelings cannot displace parental rights.”

My lawyer smiled politely, the way a surgeon might smile at a conspiracy theorist explaining blood. “Rights are not magic,” he said. “They’re contracts with time.”

The judge scheduled the next hearing—evidentiary this time—and granted, for the interim, exactly what we asked: no contact without my consent; no direct approaches at school or work; no media appearances using Lily’s name or image without legal repercussions that sounded like numbers and could hurt in the places where they sleep.

Outside on the steps, the air felt new. Lily breathed, a big breath that changed her height. “I thought my heart would crawl out of my throat,” she said. “Then it didn’t.”

“You did good,” I said.

“They looked smaller,” she added. She didn’t say “than the memory.” She didn’t have to.

On the walk to the car, Dave’s truck pulled up to the curb. He leaned across and rolled down the window like a man in a movie whose first joke is his mustache. “Heard a rumor about a court thing,” he said. “Brought donuts the size of hubcaps. Doctor’s orders.”

“You’re not a doctor,” I said.

“And yet,” he said, and handed a greasy bag like a sacrament. “Proud of you, kid,” he told Lily, and then, because he is Dave, he added, “Don’t let the bastards edit your story.”

We ate the donuts in the front seat, powdered sugar mapping a small blizzard across our laps. Lily flicked some off my jacket. “June,” she said, staring out at the courthouse where other families poured in like weather. “Mountains.”

“Mountains,” I said.

That night, I slept the kind of sleep where your body stops bargaining. No dreams, no staggered wakings. When I woke up, the sun was doing its weak best through the blinds. I walked down the hall and paused at Lily’s door. It was open. On her desk sat our notebook—the one with the list. She’d added a line under my last entry: Tell the truth to someone who deserves it. In her neat, blocky hand, she’d written: Done. Next?

On the bottom of the page, there was a sticky note, pink as gum, with an address scribbled on it—the address of a community college an hour away, the one with the EMT course that runs in the summer. Next to it, two words: What if?

I poured coffee. I let myself stand at the window and watch nothing for a while. Then I took a pen and drew a small box next to Mountains. I didn’t check it yet. The good boxes should take time.

Around noon, the phone rang. It was the lawyer. “Ordinarily,” he began, and then laughed at himself. “We did well. Expect them to regroup. I’m hearing back-channel bluster. A friend of a friend of a friend says they may try to move jurisdiction, claim you’re hostile, claim media harassment.”

“Let them,” I said. “I’ve got a stack of paper that says Tuesday.”

“Keep doing what you do,” he said. “Show up. Be boring. Courts fall in love with boring.”

“I can do boring like it’s my profession,” I said, and he laughed.

After dinner, Lily and I went out to the driveway again. The real tire was patched by then. We swapped it back, moving without speaking like people who have rehearsed the same song until the muscle learns it. When we finished, she leaned against the hood and looked up. The moon was a nicked coin. Somewhere, down the block, a couple fought gently in a kitchen—with those round, cushiony words you use when you want to argue without breaking anything.

“Uncle,” she said after a while, “can I tell you something? About the mountain?”

“Always,” I said.

“I remember the cold and the stars and how the dark felt like something solid you could lean on. I remember thinking: if I make myself small enough, I’ll fit in someone’s pocket and they’ll take me home. And then I remember headlights, and your voice. You sounded mad and soft at the same time. Like you were scolding the night for trying to keep me.”

I swallowed. “I was,” I said.

“I know,” she said. “I think I knew even then.”

We went inside. On the television, a weather map threw colors at the country as if it were trying to teach it something. A storm was forming far west, the arrows pointing east like accusations. The weatherman smiled as he warned us. He always smiled. Maybe it was in his contract.

When the next call came—because in stories like ours there is always a next call—it was not from the lawyer or the reporter or the neighbor with the binoculars. It was from my brother, late, the hour when people confess or mistake the dark for forgiveness.

“Please,” he said when I finally answered, even though every muscle wanted me to let it ring into the lake of missed calls. “Can we talk?”

“You can talk to your lawyer,” I said.

“I’m not calling for me,” he said. “I’m calling for her.”

I waited.

“She—” His voice cracked. He didn’t clear it, pride chewing on his throat. “She says she wants to apologize. She says she remembers the mountain wrong.”

“That’s the thing about memory,” I said. “It’s a lousy stenographer. But paper’s a decent one, and Lily’s is good. If she wants to apologize, she can write an affidavit that says exactly what happened. Every detail. No varnish. And she can include the date she tried to abandon our history again by pretending I was keeping her from a daughter she’d already given away.”

“She won’t do that,” he said, and there it was: the thin smile in his voice again, the cellophane stretched over a lie.

“Then there’s nothing to talk about.”

“Uncle,” he tried, using my name for me like a key he could borrow. “Please. We were kids. We—”

“You were thirty,” I said. “You left a child on a picnic table in air that could split skin. And you want me to pretend ten years is a rounding error.”

The silence that followed wasn’t the heavy kind or the waiting kind. It was the kind that happens when a man looks down and finds the rope he thought he was throwing to someone else wrapped around his own waist.

I ended the call. I stood in the quiet, listening to the house do its winter sounds. Then I climbed the stairs and paused at Lily’s door again. She was sitting on the floor, back against the bed, textbook open, highlighter cap between her teeth. She looked up.

“Mountain?” she asked.

“Mountains,” I said. “Plural.”

She smiled, and for a second she looked eight again, thin and bruised and bright, the streetlight outside pretending it was a moon. Then she looked eighteen, which is its own kind of mountain.

“Good,” she said. “I want a whole range.”

Part IV:

The morning of the evidentiary hearing broke cold and colorless, the courthouse steps shining with ice in patches no salt could catch. I parked two blocks away, not out of fear, but because I wanted the walk. Lily walked beside me, her boots crunching the frozen grit, her breath steady. She didn’t speak, but her silence wasn’t heavy—it was sharpened, honed like the edge of something forged.

Inside, the fluorescent lights turned everyone pale. The benches were full of strangers rehearsing their own tragedies: custody fights, divorces, evictions. Each person clutched paper like it was both shield and weapon. The air tasted like old coffee and dry air vents.

Our lawyer sat waiting, files stacked high, glasses perched at the end of his nose. “Ordinarily,” he began out of habit, then stopped himself with a faint grin. “But not today. Today we set the record.”

Across the aisle, my brother and his wife sat stiff, their lawyer whispering in low tones. She wore pearls, too bright against the courtroom’s drab walls, as if she thought jewelry could sway a judge. He wore the same brittle smile that used to charm teachers into forgiving late assignments. But charm doesn’t work on paper.

When the hearing started, their lawyer painted them as reborn saints. “They regret their past,” he said, his voice smooth as polished wood. “They’ve grown, they’ve stabilized, they seek only to reclaim the bond of blood. Reunification is healing. Redemption is the American promise.”

My lawyer didn’t bother with poetry. “Abandonment,” he said. “Documented, willful, prolonged. Ten years of absence. Ten years of another adult carrying the weight. The law does not reward desertion. It does not allow people to vanish when things are hard and return when things are convenient.”

He presented photos: Lily’s school certificates, doctor’s records, even the notes from teachers who praised her resilience. He laid down affidavits from neighbors, teachers, the social worker who’d once stood on our porch and written the words stable, nurturing, protective. Each piece of paper was a stone, and together they built a wall no pearl necklace could climb.

When it was their turn, my brother’s wife took the stand. Her voice shook, but not with shame—with performance. “We were scared,” she said. “Young. We thought we were doing what was best. But we’ve changed. We’re ready to make things right.”

“Best?” my lawyer asked in cross-examination, his tone flat. “Leaving a child half-conscious in the mountains in winter—that was best?”

Her lips trembled. “We didn’t know what else to do.”

“You knew how to walk away,” he said. “And for ten years you knew how not to come back.”

When my brother took the stand, he avoided my eyes. He spoke about blood, about second chances, about how families fracture but can heal. His words were hollow, a song sung in the wrong key.

Then, the judge did something I didn’t expect. He turned to Lily. “Do you wish to speak again?”

She hesitated for a moment, then stood. Her voice was calm, but the words cut sharp. “I am not something to be given away and taken back. I was left. I was hurt. I was raised by the man who stayed, not the ones who left. You don’t get to abandon someone and then call it mercy. You don’t get to come back when it suits you and pretend you’re heroes. I know who my father is. And it isn’t either of them.”

Her words echoed in the courtroom, hanging in the air long after she sat down. Even the clerk stopped typing for a beat.

The judge cleared his throat. “Thank you, Ms. Dalton.”

The ruling didn’t come that day—it rarely does. Judges like to retreat, to weigh, to write. But I saw it in his eyes: the recognition that truth doesn’t need embroidery. It sits plain and undeniable.

That evening, back home, Lily dropped her backpack by the couch and slumped into a chair. She looked exhausted but lighter, like someone who had finally exhaled after holding her breath for a decade.

“You okay?” I asked.

She nodded. “It felt good to say it. Out loud. To them.” She looked at me, her eyes sharper than ever. “They can’t touch me anymore, can they?”

“Not without going through me first,” I said. “And the law. And a stack of paper thicker than a Bible.”

She smiled faintly. “Good.”

Later, when she’d gone upstairs, I sat at the kitchen table with our notebook. I flipped to the page with the list. Next to Mountains, I drew half a checkmark, then stopped. Not yet. But close.

I stared at the pink sticky note she’d left—the one with the community college address. What if? it said.

And for the first time in years, I let myself believe the what if could be more than survival. It could be a future.

The storm outside had quieted by nightfall. I opened the door and stepped onto the porch. The air was cold, sharp enough to sting, but clean. The street was empty, the snow reflecting the faint glow of the streetlights. My brother and his wife were gone, their silhouettes no longer haunting the edge of the block.

For the first time in a long time, the silence didn’t feel like a threat. It felt like peace.

And for the first time since the mountain, I let myself believe the storm had truly passed.

Part V: Verdicts and Roads

Two nights before the ruling, the town did that thaw-freeze trick that turns streets into skating rinks. I salted the steps at dawn, listening to the scrape of my metal scoop on concrete while the radio murmured forecasts that were really apologies: patchy black ice, a chance of flurries, take it slow out there. I’d been taking it slow for ten years.

Lily shuffled into the kitchen in thick socks and a hoodie, hair in a knot she’d forget about until it gave her a headache. She poured cereal, then slid onto the stool at the island and looked at me over the rim of the bowl.

“You think he’s going to rule our way?” she asked.

“I think the truth is heavy,” I said. “And judges are trained not to let wind push them around.”

She considered that, fished a cheerio from the milk, and flicked it at the sink. “You always say things like that.”

“Like what?”

“Like you’re building a shelf while you talk.”

“That’s because I am,” I said. “Words are shelves. You put the facts on them so they don’t fall on your head.”

She laughed. “Okay, carpenter.”

On my way to shift, I passed my brother’s neighborhood—well, the neighborhood where they’d bought their clean-slatery. I hadn’t driven through it on purpose; a detour took me there when a delivery truck blocked Main Street, and I let red lights herd me the rest of the way. It was one of those developments where all the mailboxes match like cousins at an Easter photo. The houses were tasteful and tall, gables like raised eyebrows. In front of one, a sign had sprouted: WARD 3 SCHOOL BOARD—RECLAIM OUR FUTURE. A glossy photograph rode the sign like a saddle. Her face, chin lifted, a smile that said trust me, I excel at meetings. If I had been a pettier man, I would have pulled the sign out of the dirt and let it nap face-down on the manicured lawn. Instead, I drove on.

That night, as if it had scented the approaching end, the past scratched at our door again. I found an envelope wedged into the handle—no stamp, just my name, the letters drawn harder than the paper deserved. Inside was one sheet, lined, torn from a legal pad. The handwriting was my brother’s: careful, then careless, then careful again.

She remembers wrong, it read. We remember wrong. We wanted to leave her with you. We panicked. It was a mistake, not abandonment.

I felt something hot climb my neck. I am not a man built for rage—it looks wrong on me, like a strangled tie—but the line between “mistake” and “choice” is where I’ve lived these last ten years, and I knew damn well which side they’d stood on. I folded the paper and slid it into the folder with everything else, in the section I’d labeled FOOLISH ATTEMPTS. Not because it mattered to the court; only because it mattered to me to archive their tricks.

“Trash,” Lily said when I told her. She had mastered the art of not letting the old stories lodge in her throat. “If they wanted to leave me with you, they could’ve done it with a doorbell and a handshake. Not a mountain.”

“Exactly,” I said. “Out loud. With witnesses. Instead they tried to outsource responsibility to the night.”

She tipped her head and smiled that small, sideways smile that says she’s filed it in the correct drawer.

The morning of the ruling, the courthouse was busier than I’d seen it. A snow day had nudged people’s calendars onto the same square. In the hallway outside our courtroom, a young man held a baby with both hands, fear and love arguing on his mouth. An older woman in a quilted vest whispered into a phone, “I told him, I told him, I told him.” A public defender in a suit that had seen more coffee than dry-cleaning did two things at once: juggled files and asked a client if she’d taken her medication today. American life: paper and pleading, stubbornness and chance.

Our lawyer greeted us with a nod and a “Morning,” stripped down for once, no ordinary, just present. He’d shaved too close, left a nick under his jaw that he’d forgotten to staunch. It made me like him more.

They were already inside: my brother and his wife, whispering, faces white with the effort of pretending calm. Her pearl necklace was gone today. Maybe someone had told her that humility photographs better.

The judge came in with his robe unwrinkled and his expression that particular neutral I’ve only ever seen on surgeons and funeral directors. The clerk called the case. We stood. We sat. He cleared his throat like a man about to read weather and new laws at once.

“After review of the submitted evidence and testimony, and pursuant to relevant statutes,” he began, “this court finds as follows.” He looked down, but not too long. He’d already read this; this was for us.

“Ten years is not a rounding error,” he said. “It is a life. The petitioners abandoned the minor child to the care of the respondent. The respondent assumed full parental responsibilities and has discharged them with vigilance and affection, as evidenced by medical records, educational records, and third-party statements. The petitioners’ recent desire for ‘reunification’ appears, by the totality of the record, to be motivated less by the interests of the young woman than by their own reputational and, perhaps, political concerns.”

There was a faint intake of breath from the gallery. That word—political—landed like a book thudding onto a table.

“Accordingly,” he continued, “the court affirms the respondent’s sole legal and physical custody nunc pro tunc and enjoins the petitioners from direct or indirect contact with the young woman without the respondent’s express consent until such time as she attains the age of majority, at which point such decisions are hers and hers alone. The court further orders that the petitioners cease any media engagements that use the young woman’s name, likeness, or personal history without written consent from the respondent and, after her eighteenth birthday, from the young woman herself.”

He looked up. He looked right at Lily. “Ms. Dalton,” he said, and his voice softened a hair. “If, as an adult, you wish to maintain distance, the law will protect you in that choice. If you wish to never see them again, you may never see them again. That is your right. And if, someday, you change your mind, that choice, too, will be yours. But rights do not heal. Time and truth do.”

He signed papers while the clerk moved like a swift, small moon around him. The gavel came down with a sound that was more polite than final, but I felt something unclench in my chest that had been a fist for a decade.

On the steps, reporters clustered like pigeons. Dave had apparently come in on his own errands and appointed himself moving obstacle; he stood with his hands on his hips and his mustache arranged in a bristle, blocking the path with a body honed on decades of stubborn. “No comment,” he told a microphone cheerfully, “especially not to people who don’t even own hats.”

We slid past with a nod and a bag he’d somehow produced anyway—donuts again, this time dusted in cinnamon like a private joke. The cold air bit our cheeks. Lily’s eyes were wet but not with sadness.

“What do we do now?” she asked.

“Breakfast,” I said. “Then we go to the DMV and order the new registration in both our names. Then we go to work and school. Then we come home and eat dinner. Then we look at maps.”

“Maps,” she repeated, and the word had a gravity to it I recognized: the weight of a promise you actually intend to keep.

That afternoon, in a corner booth at the diner where Lily worked, the manager—a woman with a voice like a trumpet and eyebrows that could scold a room—brought us pie on the house. “For your girl,” she said, and tapped the edge of the plate as if it were a medal. “Sugar heals nothing, but it helps the day pass softer.”

We ate. A man at the counter hunched over a crossword swore gently at Fluorine’s neighbor. A toddler in a puffy jacket danced to a song only he could hear. A snowplow went by, its blade up now, the driver’s face loose with relief. The world continued with its ordinary heroism.

The injunction didn’t make them disappear right away. Their lawyer filed something that sounded like a question disguised as a trap, then retracted it when our lawyer answered with paper that said don’t try that again. Her school board signs vanished from the neighborhood where I’d seen them, replaced by another candidate who used the word nuts-and-bolts in his tagline. A blog printed a paragraph-sized story that used the words “family dispute” and “private matter.” I made a donation to the public library and wrote in honor of people who leave and people who stay in the line that asked why.

A week later, on a Tuesday that thought it was a Friday, the manager at the diner had to kick my brother out. He came in alone, sat in Lily’s section, asked for coffee, then asked for Lily.

“You can stand up and walk out,” the manager told him, hands on hips, eyebrows arranged to maximum scold. “Or you can watch me call the police and then watch me not hang up.”

He stood up and walked out. Lily didn’t find out until after her shift, because the manager, who understood triage in a different language, had quietly slid a different waitress into that station while Lily delivered omelets three tables over.

When Lily told me, there was a spear of fear inside the anger that surprised me with its sharpness. You think you’re done with fear, but it caches itself like winter salt: handy, coarse, ready. We emailed the lawyer; he reached out to their lawyer; the message came back that it wouldn’t happen again. I believed it and didn’t. Belief is a muscle that tires quickly if you’ve actually used it.

Spring came like a cautious animal. Snow eddied off the curb into drains. The dogwood two blocks over tried a tentative blush. We bought a new-used tent from a guy who swore it “only got coughed on once.” We found a map of the country at the thrift store—the kind you pin to a wall with colorful pushpins in a configuration that makes sense only to you. Lily stuck a blue pin in our town, a green pin in Jackson, Wyoming, and a red pin in that stretch of I-80 where they warn you with extra signs that the wind does not care about your plans.

Dr. Patel cleared Lily for the kind of travel that worries mothers. “Sleep,” she said. “Water. Snack often. Do not try to see everything in one day; curiosity is not an emergency.”

Halley, the social worker, showed up on our porch Saturday with a bag of granola bars and a smile I hadn’t seen on her before—the smile social workers wear when a case becomes a person they don’t have to worry about between midnight and dawn. “I can’t accept gifts,” she joked, handing us the bag. “But I can re-home them to people who are going places.”

We packed in lists. Dave came over with a tool kit and a headlamp and an unsolicited lecture on tire pressure altitudes. “You’ll call if the car starts making a whistling noise,” he said. “You’ll call if it starts making a clunking noise. You’ll call if it starts making a winning noise, as in, it really sounds like you’re going to win whatever race you’re in.”

“We’re not racing,” Lily said, rolling her eyes.

“Life is a race,” he said gravely, “against foolishness.” Then he hugged her with the kind of one-armed hug old men give when both their shoulders hurt. “I’m proud of you, kid.”

The night before we left, Lily came into the kitchen with our notebook. She set it on the table, slid into a chair, and stared at the page that had grown crowded with checkmarks.

“Can I add something?” she asked.

“It’s our list,” I said. “Add away.”

She wrote carefully, printing like she had in third grade when she wanted the penmanship award: Consider adult adoption. She didn’t look at me while she did it. When she finished, she put the pen down and folded her hands like a person praying to a god they’re not convinced exists.

I put one finger on the page, next to the words. “I’d like that,” I said. My voice didn’t wobble. It did something else, something quiet and permanent. “On your timeline.”

She nodded. “June,” she said, and smiled. “Birthday paperwork.”

“In a courthouse with a judge who doesn’t smile much,” I said.

“And donuts afterward,” she added.

“It’s mandatory,” I said. “It’s in the statute.”

We left before dawn, the car rattling a little with the weight of our ambition and two extra cases of bottled water. Dave stood in his bathrobe at his mailbox, pretending to get a letter so he could wave. We waved back. The sky above the interstate turned from graphite to pearl. We listened to a playlist Lily had made that swung from Motown to outlaw country to some soft indie stuff where all the guitars sounded like sleep.

We learned the country by its gas station coffee. We learned that Nebraska is not a punchline but a palette, that Wyoming sky is a kind of arrogance that forgives you for staring. We learned how to take turns being the quiet one. At a motel in Laramie, we read the brochure about glacial valleys and circled someone’s hand-drawn asterisk that said Best view at dusk.

On the third day, the Tetons rose like the backs of sleeping animals, blue and unsympathetic and gorgeous. We parked at a trailhead and sat for a while without getting out of the car, because there is dignity in letting your eyes do the first hike.

“Looks like teeth,” Lily said.

“Looks like a patient row of saws,” I said.

“Looks like a place where gifts and threats are the same thing,” she said, and I loved her for it.

We walked. She set the pace because it was her trip as much as mine, and because my left knee had opinions it wanted me to respect. The path was early-season mud, the kind that keeps you honest. Snow clung to the shaded edges like stubborn men to bad ideas. The air was the kind that lifts you inside. We didn’t talk much. We didn’t need to.

At a clearing, where a bench had learned to face the right direction, we sat. She took the postcard of these very mountains—the one that had lived on her dresser for years—and propped it on the bench between us. She laughed, shaking her head. “The real thing is always uglier and better.”

“Like people,” I said.

“Like stories,” she added.

We didn’t do anything ceremonial. We didn’t scatter ash or burn letters. We ate granola bars from Halley and drank water that tasted like plastic and cold. We breathed. After a while, Lily reached into her backpack and pulled out a Ziploc bag. Inside was the legal-pad letter from the door handle—the one that called what they did a mistake. She held it up, looked at it the way you look at a bug you’re thinking of escorting outside, then slid it back into the bag and tucked it under the bench.

“For the marmots,” she said. “They can write their own affidavits.”

We laughed. The laughter didn’t catch on any thorn in our throats.

On her birthday in June, back home with the mountains now a place instead of a prophecy, we went to a courthouse with a room no bigger than a classroom. The judge was a woman with silver hair and patience in her shoulders. She read the petition without fanfare. Adult adoptions are quick when no one is contesting them. She asked Lily once, “Is this what you want?” and Lily said, “Yes,” the way you say yes to the correct question after a test with too many wrong ones. She asked me once, “Are you ready to be responsible for her, even though you already have been?” and I said, “Yes,” the way you say yes to the thing you’ve already been doing and want to keep doing until your hands stop working.

She signed. We signed. There was no gavel. There was only a stamp that clicked and inked a date next to our names. The judge smiled the kind of smile that happens when a tiny corner of bureaucracy gets to be kind.

In the hallway, Lily hugged me. “Dad,” she said in my ear, a small, ordinary word that felt like it fit my ribs better than the lungs that had come with the original design. “Thank you.”

“You did this,” I said. “I just kept the coffee hot.”

We ate donuts on the courthouse lawn because of course we did, powdered sugar on new paper. Dave joined us in a suit he’d owned since Reagan and a tie that had forgotten it once lived in a closet. Dr. Patel sent flowers with a card that said: Vitals: strong. Halley texted a picture of her desk with a post-it that read Closed and sixteen exclamation points. Ms. Liang emailed a poem. The manager at the diner yelled at the lunch rush kindly and then came on her break to squeeze Lily until the ketchup bottles trembled.

A week later, a postcard arrived from a P.O. box in a neighboring town. It was a photograph of water lilies. The handwriting was my brother’s wife’s: small, neat, as if precision were a virtue you could wear like a dress.

We heard about the adoption, it said. We won’t contact you again. We wish you well.

Lily read it, then set it on the counter with the gravity of someone placing a tiny stone. “There,” she said. “An ending.”

“Some endings you don’t have to mistrust,” I said.

Summer found us the way summer does: all at once and too slow. Lily enrolled in the EMT course at the community college. She learned the alphabet of sirens and the art of looking at a scene and seeing what matters. On weekends, we drove. Not always far. Sometimes just far enough to find a picnic table that didn’t remind us of anything but sandwiches. We collected maps not as an escape plan but as receipts for a promise fulfilled.

One evening in July, during a thunderstorm that made the windows count their own heartbeats, Lily came downstairs with the notebook. She’d turned to the page where Mountains wore its checkmark like a medal and Consider adult adoption had become Done with a scrawl that leaned left, cocky. Underneath, she wrote: Tell the truth to someone who deserves it. And then she looked at me.

I didn’t need to ask. I knew that look. It’s the one you aim at the past when you’ve decided to tell it it no longer lives here rent-free.

She called Ms. Liang and told her the part she hadn’t told yet: the moment, at eight, behind the grocery store, when she had climbed into the dumpster because the grapes were sweeter there. How the bruises on her arms didn’t come from the mountain, but from the weeks before, from the person who thought heartbreak gave them permission to train a child like a dog. How the man with the cigarette had seen her and said nothing and how the woman with the name tag said something and how a phone call becomes a rope in a dark well.

She told it slow. She didn’t cry. When she finished, Ms. Liang said, “Thank you,” in the voice teachers reserve for essays that change their own grading rubric. “Do you want me to write this down?”

“Yes,” Lily said. “Not because I need it, but because the next kid might.”

Later that night, when the storm had moved off and left the world washed like dishes, we took the dog we still didn’t have for the walk we kept taking without him. The air smelled like electric things. A neighbor we barely knew waved. A different neighbor—new family, tiny bike in the driveway—wrestled a car seat with one hand and a grocery bag with the other. I grabbed the bag without asking. She said thanks with her eyes.

At home, the porch light did its sagely little blink. I stood at the threshold where ten years ago I’d said Leave and meant Never again. I looked at the house, at the frames along the hallway, at the metal shelves with their tidy labels that meant, secretly, we are not afraid of emergencies. I listened for the hum of the breathing machine I no longer needed to fear. I listened to the sound of Lily—my daughter—moving in the kitchen, opening a cabinet, closing a drawer, humming off-key.

People talk about endings like they’re fireworks: noisy, bright, disappearing in a high sky. But the best ending I’ve ever known sounds like a house getting ready for bed. It sounds like someone calling from the other room, “Do we have any cinnamon?” It sounds like the answer, “Always,” and the drawer opening, and the tin sliding forward, and the powder dusting the rim of ordinary life with sweetness.

We cleaned up. We turned off lights. The storm had passed, not with drama, but with a long, patient exhale. On the fridge, the map of the country held our pins without wobbling. On the table, the notebook waited with its next blank line.

“Write something,” Lily said.

I picked up the pen. My hand didn’t shake. On the next line I wrote: Teach me the names of the constellations you see that I don’t know yet. It looked like a small thing. It was not a small thing.

She read it, grinned. “Deal,” she said.

We went upstairs. The house, the street, the town held. The night did what night does. We slept.

In the morning, the air was sharp enough to slice skin, the way it had been ten years ago. But this time the door we opened was just a door, and the threshold was just a line, and on the other side of it was not an ambush but a day. We stepped into it together, cinnamon on our tongues, paper on our side, mountains in our rearview and, somehow, ahead of us too.

THE END

News

My Ex Told the Judge Our Son Wanted to Live With Him. Then My Son Pulled Out His Phone… CH2

Part I The courtroom was quiet, but not the kind of quiet that helps. It was the kind that made…

My Son Broke a Bully’s Arm. His Father Came For Me, Then I Said The One Word That Made Him Flee… CH2

Part I On Maple Street, the morning always started with sunlight and simple math. Two eggs, over easy. One travel…

Cheating Wife Walked Into The Kitchen & Froze When She Saw Me,”You Didn’t Leave?”… CH2

Part I The saw kicked back and bit deep into my palm, splitting skin like wet paper. A scarlet V…

My Parents Hid My Tumor, Calling It “Drama”—Then the Surgeon’s Discovery Stunned Everyone… CH2

Part I The lump started like a bad idea: small, ignorable, something you tell yourself you’ll “deal with later.” I…

My Dad Left Me On The Emergency Table Because My Sister Had A Meltdown – I’ll Never Forget This… CH2

Part I Antiseptic burns in a way that feels righteous. It bites the skin as if scolding flesh for failing…

‘RACHEL, THIS TABLE IS FOR FAMILY. GO FIND A SPOT OUTSIDE.’ MY COUSIN LAUGHED. THEN THE WAITER DROPP… CH2

Part I The leather folder landed in front of me like a trap snapping shut. I didn’t flinch. I didn’t…

End of content

No more pages to load