The Knock at 12:03

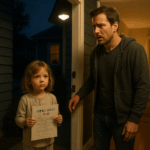

When the knock came, I thought it was a branch on the siding. The mountain does that in March—throws sticks and nighttime at your windows until the dark hums. But then the knock came again. Three taps. Small. Precise. The kind a child would make if she were trying not to wake a monster.

I slid the deadbolt, opened the door, and my world tore down the center.

“Hollis?”

She stood on the mat in her ladybug pajamas, hair tangled, cheeks chapped. In one fist, she clutched a stuffed fox by the ear. In the other, a crumpled sheet of paper, damp around the edges where little hands had sweatingly held on for dear life. Her eyes—Brennan’s eyes—went wide with relief when she saw me. Then the relief vanished under training that didn’t belong on a four-year-old’s face.

“Uncle Cass,” she whispered. “I came like Daddy said.”

I scooped her up. She weighed almost nothing. The fox plopped to the floor. The paper stayed crushed in her fist like a passport. I smelled wood smoke in her hair from some neighbor’s fire and something sour underneath that no child should ever wear. Behind her on the gravel drive sat a plastic pink scooter, its back wheel worn flat and shining from the long skid down the shoulder of Route 197. The night around us felt like a held breath.

Inside, I set her on the kitchen counter. The under-cabinet lights washed her in a soft yellow that showed every bruise the house had tried to hide. Half-moons on both arms. Faint fingerprints where a hand had taught a lesson. A gray smear on her cheek I prayed was dirt.

She opened her fist and offered me the paper like a mission delivered. “Mommy said give you this.”

I took it carefully. PARENTAL RIGHTS DESIGNATION—downloaded from a state website and butchered. Boxes checked in a different ink than the signature. A date handwritten wrong and overwritten again. Brennan’s name printed in the wrong slant. My name—CASSIUS MERCER—spelled correctly, which meant whoever forged it knew me too well.

My stomach dropped through the floorboards.

“Did Mommy bring you?” My voice wanted to be gentle and ended up hoarse.

Hollis shook her head. “Mommy and Kirk were yelling. Mommy said I was ‘complicating logistics.’” She sounded the last word out carefully, like she’d had to practice it. “She said I needed to go to you now and give you the paper. Then she went to the sink and counted white dots in her hand. I went out the back door before she could look for me.”

Benzos. Brennan had told me about the dots the week before he died. About the bitter taste in his beer. About how Laurel called them “calm-down vitamins” and smiled when she said it.

“Did you ride all the way here?” I asked softly.

“Halfway. Then Mr. Mendez saw me and put me in his truck, but he had to go back to the gas station. He said my Uncle Cass was the one with the red mailbox and the mean blue dog.” She peered over the counter toward the mudroom. “Where’s the dog?”

“There’s no dog.” I swallowed. “Mr. Mendez was trying to be funny.”

“Mommy says funny things aren’t true,” she said with the small authority of someone repeating a law that always worked against her.

I took a breath, let it out slow, and put water for cocoa on the stove because sometimes the first thing you can do is put something warm in a small, cold body. “Are you hungry?”

She nodded, quick and guilty, like hunger was a betrayal. I cut an apple, kept my knife hands steady while I wanted to shake. Midnight apples and cocoa and the tremble in my legs that wouldn’t stop. I texted Naira—my attorney, my human procedural manual—Come now. Emergency. Then I texted Rex Winters, the P.I. who’d almost caught this storm before it broke. It’s happening.

“Daddy said he wouldn’t leave me,” Hollis said as I slid the mug toward her. She wrapped both hands around it and didn’t drink. “He promised. He said even if he got sad he wouldn’t go away.”

My jaw tightened. The sheet of paper on the counter burned a hole through the laminate. Brennan had gone away, a month earlier, found in his bathtub with pill levels the coroner labeled inconclusive and the police labeled suicide because messy truths make for long forms. The town had nodded, murmured about how sometimes sadness wins, and dropped casseroles on Laurel’s porch. I had wanted to burn the world down, but I’d been too busy building a room for a little girl with a ladybug nightlight who now sat in my kitchen like a question I finally knew how to answer.

“When did Daddy tell you that?” I asked.

“The day before he took a nap in the tub.” She looked at the cocoa like it might tell her what to do. “He said if Mommy told me he went away on purpose, I should come find you. So I did.”

My hands moved before my brain did. I gathered her close and felt the small bones in her back, the bird-boned fragility of a child who had learned to make herself smaller than her fear. “You did perfect,” I said into her hair. “You did exactly right.”

Her body loosened. Some of the air I’d been holding since the 911 call about Brennan finally left me.

The porch light cut another slice out of the night. Naira walked in like a verdict. She took one look at Hollis on the counter, the paper at my elbow, and her face turned into case law.

“Read,” I said.

She did—a quick skim the way attorneys do when they’re deciding which limb to saw to save the body. “Notarization’s a joke,” she said flatly, tapping the smeared stamp. “Signature’s a trace. Wrong county seal. Whoever filled this out wanted it to look real to a receptionist and no one else.” She lifted her eyes to mine. “Cass, she left this with the child to clear her conscience, not to transfer rights.”

“It’s enough to get me temporary custody?”

“It’s enough to get you a judge at 8 a.m.,” she said. “And enough to get CPS out of the way if anybody tries to drag Hollis back tonight.”

The door opened again. Rex Winters took off a rain-spattered ball cap and nodded at Hollis, whose eyes went round at the sight of a man built like a refrigerator who knew how to be gentle.

“Hey, Peanut,” he said, voice soft. “You like puzzles?”

She nodded. He pulled a fifty-piece ocean puzzle from his backpack like a magician. “Then I’m the right guy. You and me’ll start with the corners.”

While they set whales against waves at the end of the table, he turned his other hand and slid a thumb drive into my palm. “Financials,” he murmured. “Dumped Laurel’s iCloud. Thought she was cute renaming it L’s Pretty Things. Found transfers that would make a pastor swear.”

“From who?” I asked.

“Kirk Blaine and half the contractors he subbed under. Cash deposits into Laurel’s personal account on the 15th of every month. Looks like a stipend for services rendered.” He kept his face toward Hollis as he spoke. “And deleted texts from a backup she forgot she had. Romantic poetry like a demolition permit. The last three weeks are angry. He’s getting sloppy, she’s getting scared.”

“Scared of what?”

“Your brother,” he said. “And your lawyer. And you.”

Naira folded the forged form and slid it into a clear sleeve with the kind of reverence you reserve for evidence that tells a story better than tears. “I’ll file an emergency ex parte petition when the clerk’s window opens,” she said. “Until then, she stays. If Laurel shows up here tonight, call 911 and me. In that order.”

“What about Brennan?” I asked before the sentence formed all the way. “What about—”

“We reopen,” she said. “We push. We pry. And tomorrow, while I’m in front of a judge, you call Detective Sarah Walsh and you beg her to do the thing good detectives lose sleep over.”

Hollis finished the border of her puzzle and looked up, proud and small. “Uncle Cass? Can I… can I eat the apple now?”

“Eat two,” I said, my voice coming out steady through some miracle. “Eat the whole damn orchard.”

She giggled at the bad word and covered her mouth like laughter might be against the rules. Then she ate, fast, like her body didn’t trust me yet but wanted to. When the slices were gone, she yawned the giant unselfconscious yawn of bedtime missed by miles.

“You have jammies?” I asked.

She held up the ladybug pajama legs as if I were blind. “I wore them.”

“Right,” I said. “Right.”

I carried her down the hall to the guest room that had been Brennan’s when we were boys and mine the night he died. The ladybug nightlight I’d bought on a hunch last week cast little red circles on the walls. She reached out sleepy fingers and tried to catch them. When I laid her on the bed, she clutched the fox by the ear, rolled to her side, and looked at me.

“You going to find out what happened to Daddy?” she asked, eyes fierce the way a four-year-old’s can be when they still believe truth is a switch you flip.

“Yes,” I said, and felt something like steel cable settle through my spine. “I’m going to stop anyone who hurt him. And I’m never going to let anyone hurt you.”

“Okay,” she whispered, and closed her eyes like she believed me.

I stood in the doorway longer than a man needs to stand to watch a sleeping child, then went back to the kitchen where Naira had made my table look like a command center—forms, tabs, sticky notes like flags planted on new land. Rex sat with one big hand flat on the puzzle as if he could hold it together by will.

“Tell me everything,” I said. “No softening.”

Rex nodded. “Cash deposits started last June—three weeks after Laurel met Blaine at a job site in Black Mountain. Pattern’s steady. He messages her from a burner. She replies from her main because she never learned what deletes and what doesn’t. The night Brennan died: three calls between her and Blaine between 8:40 and 9:10. Then a twenty-two minute gap. Then the 911 call.”

“Twenty-two minutes,” I said. The number felt like an animal in the room.

“Yep.”

“God.” My hands curled into fists. When I opened them, the crescent moons my nails had dug into my palms had already gone white. “What about motive?”

Rex looked at the puzzle, not me. “She didn’t want to lose the kid in a custody fight, Cass. And she didn’t want to lose the house and the Blaine money. Brennan had hired me that week to document the affair. He’d met with a divorce attorney. Laurel knew. She needed a different story.”

Naira slid a legal pad toward me. “Which is why we don’t go vigilante,” she said, reading the storm in my face like a forecast. “We do this slow and clean. We make it stick.”

“I said I’d stop her,” I said, my voice lower than I intended. “I didn’t say how.”

“You’ll stop her by making sure Hollis never goes back there,” Naira said. “And by making the state do its job.” She tapped the forged form in the sleeve. “This got Hollis to your door. We’ll use it for the only thing it’s good for: proof of Laurel’s intent to abandon. The rest we’ll build.”

Rex slid a small recorder across the table. “Sarah Walsh is good,” he said. “Pride and all. But she’s a cop who knows a bad call keeps her up at night. You put this on her desk with what I’ve got and she reopens.”

I nodded, and the motion felt like a promise I was binding myself to.

The kitchen clock thudded into 1:00 a.m. The mountains outside pressed their dark foreheads against the glass. I wanted to sit until dawn tracing every line the night had handed me, but men who don’t sleep break later in the day and I couldn’t afford to break anymore.

“Go,” I told Naira and Rex. “I’ll sit first watch.”

“Text if her car touches your road,” Naira said, gathering her case like a weapon. “I’ll file at eight sharp.”

Rex paused at the door. “Kid’s tough,” he said, nodding down the hall. “So are you. Brennan picked the right person.”

After they left, I walked the house. Checked the back door twice. Looked at the scooter on the porch and wanted to smash it and save it at the same time. In my workshop, I flipped on the light and the space glowed alive—Brennan’s tools still hung in the place he’d left them: hand planes the color of honey, chisels that fit my grip like they’d been waiting. On the bench was the small dollhouse he’d started for Hollis’s fifth birthday. The tiny windows were still taped for paint he’d never get to.

I set my palms flat on the bench. The wood remembered. So did I.

In the bottom drawer of the tool chest, under sandpaper and a jar of mismatched screws, I kept an envelope I hadn’t been able to open since the funeral. Brennan’s last will and a note with two sentences written in his blocky carpenter’s hand.

If something happens to me, find Hollis first. Then find the truth.

“Okay,” I said to the empty room. “I hear you.”

By 2:30, the house had settled into the kind of quiet that shows you where you’re weak. I made coffee I didn’t need and sat at the table with the forged form in its sleeve and a pen I wasn’t going to use. I wrote out what tomorrow would be, step by step, like a mission plan:

0800 — Naira files emergency petition for temporary custody.

0830 — Call Detective Walsh, deliver Rex’s packet, ask to reopen.

0900 — Pediatrician appointment for Hollis; document bruising, weight, labs.

1000 — CPS home visit on my terms, not theirs.

Afternoon — Replace locks at Brennan’s house.

Evening — Buy purple paint for a little girl’s room and a ladybug duvet that matches the nightlight.

At 3:17, Hollis cried out, a short animal sound that turned my bones inside out. I reached her room in five steps. She was sitting up, fox crushed in her fists, eyes wide and unseeing.

“It’s me,” I said, kneeling. “You’re safe.”

“Is Mommy here?” she asked, voice tiny.

“No,” I said. “Mommy’s not here.”

“Is Daddy?” The way she said Daddy cut me longer than any blade.

“He can’t be,” I said, and the truth felt like gravel in my mouth. “But I am.”

She looked at me for a long second, then leaned forward and put her forehead against mine the way Brennan used to do when we were boys and I’d split my lip on a fence. “Okay,” she whispered, and lay back down.

I sat in the doorway until her breathing evened out, then stayed in the chair until the outline of the mountain turned from black to charcoal to the first gray hints of morning. Birdsong began low and then grew, small voices that didn’t know the world is complicated.

At 7:45, I packed a bag for Hollis—one pair of jeans, two T-shirts, the fox, the ladybug socks I found at the back of a drawer. I put the forged form in a hard folder and the will in another. I kissed the top of my niece’s head and felt the small, hot thud of her life against my lips.

At 7:59, I stood on the courthouse steps with Naira and watched the door unlock. We walked inside together. The fluorescent lights were too bright. The linoleum shone like a threat.

“This is going to be ugly,” Naira said quietly as we waited at the clerk’s window. “Laurel will fight. People will take sides. Your brother’s memory will be pulled apart in a room where truth competes with theater.”

“I know,” I said.

“You sure?” she asked.

I looked down at the ladybug sock peeking out of Hollis’s shoe and the fox ear sticking out of her backpack. I felt the forged form like a splinter under my skin and the two sentences Brennan had left like a brand.

“I’m sure,” I said. “We start now.”

The clerk took the petition. The stamp came down with a sound like a door closing on a bad room.

Outside, the mountain shook off the last of the night. I called Detective Sarah Walsh and listened to her phone ring toward whatever came next.

The Wire at Riverside

Detective Sarah Walsh called back before the clerk’s stamp had cooled.

“Mercer,” she said, voice textured by three decades of shift coffee and bad news. “I’m told you have something I need to see.”

“I do,” I said. “And a little girl who needs to never go back.”

“Bring both. Station, evidence intake. I’ll meet you there.”

Naira angled us toward the pediatric clinic first. “We document while the bruises are still fresh,” she said, the sentence a scalpel. Hollis didn’t complain; she laid her small arm out for the cuff like a soldier. Dr. Rivera, a pediatrician with a voice that could anchor a ship, examined her gently, noting everything—faint fingerprints on the upper arms, healing welt lines across the thighs, weight in the fourth percentile.

“We’ll do bloodwork,” she said softly. “Malnutrition markers, tox screen, everything. Not because I think she’s been drugged—but because if she has, we don’t miss it. I’ll file a 51A today.” She looked at me. “You’ve done right by her.”

Hollis chose a purple lollipop she didn’t lick. In the hallway, she squeezed my hand and whispered, “If I’m brave, will Daddy know?”

“He already does,” I said.

At the station, Detective Walsh waved us past the front desk with a nod that accepted the chaos trailing us. She was taller than I expected, silver hair braided tight and tucked under; eyes set to skeptical until evidence moved them. Her office looked like a filing cabinet had exploded and landed in a museum—photos pinned precisely over stacks of meticulously labeled boxes.

“Sit,” she said. “Start with the paper.”

I handed over the forged parental rights form in its sleeve. She read the top half once, then the signature three times. “Notary stamp’s wrong year,” she said. “Good for a DMV clerk. Not good for me.”

“Rex pulled her cloud backup,” I said, sliding the thumb drive across. “Deposits, texts, call logs. We think she and a contractor named Kirk Blaine have been moving cash to her since last summer. Brennan hired Rex the week he died. We think she moved first.”

Walsh glanced at Naira. “And you?”

“Emergency custody petition is filed. Dr. Rivera will send you her report. CPS will still have to do the dance, but we’ve set the music.” Naira folded her hands. “We’re not here to point fingers, Detective. We’re here because my client’s brother is dead and the box you put him in isn’t the right one.”

Walsh didn’t flinch. “I put him in the only box the evidence allowed,” she said, not defensive, just honest. “If your evidence builds a bigger box, I’ll move him.”

We watched her plug in the drive. The screen filled with numbers that became a pattern under her eyes—$3,000 here, $4,999 there, on the fifteenth like a salary paid by guilt. Then the texts. We’ll be free soon. He’s weaker than he thinks. Make sure he drinks it all. Her jaw tightened at that one. She scrolled, read, scrolled again.

“You’re right about one thing,” she said finally. “This is enough to reopen. I can’t charge a ghost with a thumb drive and a bad stamp. But I can pull tox, re-interview, and ask a DA for a wire if you can bait a hook.”

“I can,” I said.

Walsh leaned back, folding the thumb drive into her palm like a coin. “She’ll smell a cop.” She looked at me. “She’ll smell you as family less. That’s leverage. That’s danger.”

“I can take danger,” I said.

Naira slid a look at me that said we will discuss the definition of take later. Out loud she said, “Controlled conditions. Your people close. We do this by the book.”

Walsh nodded. “I don’t do it any other way.” She turned to me. “You know what a wire does and doesn’t do?”

“It makes evidence out of words,” I said. “It doesn’t stop a knife.”

“Good,” she said. “We get our wire from the DA’s tech. We’ll need a pretext that gets her talking about motive, method, intent.” She tilted her head. “What will make her talk?”

“Narcissists tell the truth when it flatters them,” I said. “She thinks she’s smarter than the room. I’ll make the room small.”

“Where?”

“Riverside Park,” I said. “Open sightlines. Multiple exits.”

Walsh scribbled. “We’ll be there, invisible. You follow my instructions or we pull the plug.” She met my eyes. “Mercer, if she runs—”

“I don’t chase,” I said. “I don’t bleed twice for the same person.”

She held my gaze a beat longer, then stood. “This goes nowhere without your kid safe,” she said. “Get CPS to your house today. Let them see purple paint swatches and a toothbrush already on the sink. They’ll write ‘appropriate kinship placement’ and we all sleep better.”

Back home, CPS arrived with clipboards and the careful voices of people who had seen too much and were still trying to be kind. They walked through the house and noted the smoke detectors and the pantry and the room with lavender paint chips lined like a parade along the wall. They asked Hollis if she felt safe. She said, “Yes,” without looking at me. They wrote that down. One of them crouched to Hollis’s level and said, “Do you like it here?” and Hollis said, “It smells like wood,” and the woman smiled in a way that said me too.

By lunch, a judge had signed the ex parte order giving me temporary physical custody. Naira handed me a copy like a talisman. “This is paper armor,” she said. “Not bulletproof. But it stops a lot of knives.”

At 1:17, I called Laurel.

She answered on the fourth ring with a voice pitched to pity. “What do you want, Cass?”

“To make a deal,” I said.

“You don’t make deals with kidnappers,” she snapped.

“You left a four-year-old on a dark road with a forged document and a scooter,” I said. “You’re lucky I’m the one who found her. We can fight in court for the next six months while you pretend to mourn and your contractor teaches my niece the difference between his boots and a belt, or we can talk.”

Silence, then the tiny click of teeth against lip. “What do you want?”

“The truth about Brennan,” I said evenly. “And you want me to normalize ‘shared custody’ in front of a judge who already knows you left a child to navigate county roads at midnight. Meet me at Riverside tomorrow at two. Come alone.”

“You think I’m stupid,” she said.

“I think you’re tired,” I said. “And you’re carrying a story too heavy for you. Put it down for an hour and walk away with something besides handcuffs.”

Another silence, longer this time. I pictured her calculating angles like she’d always done—who to charm, who to frighten, who to lie to. “Two o’clock,” she said. “If I see a cop—”

“You’ll see geese and a man who’s angry,” I said. “Keep it simple.”

When I hung up, my hands shook—not with fear, but with a current I remembered from my service: the hum before a drop, when the plan fit the terrain and you had to meet it halfway. I went into the workshop and stood over Brennan’s bench; the wire would go under a shirt that still smelled faintly of sawdust and lemon oil. The dollhouse waited, windows masked. I wanted to paint now, to put the world to rights with a small brush and careful lines. Instead, I laid out a different kit: recorder, spare mic, a back-up phone that shared location with Naira and Walsh.

That night, I made mac and cheese for dinner because simple food makes conversation easier, and tomorrow needed to be about ordinary for Hollis. She ate like she was practicing being a child. We picked the purple paint together—Moonflower, the card said, the kind of name that made a promise. She held the brush with her whole hand and dragged a careful stripe down the wall. “Daddy would like this one,” she said.

“Daddy would fuss about the edges,” I said, and she giggled. “We’ll fix them later.”

When she fell asleep, I sat in the living room with the recorder in my pocket and the way the house sounded when I was the one responsible for its breathing. I called Naira. “If she says it,” I said, “if she actually says it—”

“We give it to Santos,” she said. “We make it a charge, not a ghost story.”

“And if she doesn’t?”

“We make it anyway,” she said. “We already have enough to reopen. The wire is the difference between closure and conviction.”

“Closure is a bad word,” I said.

“I know,” she replied. “Sleep.”

I didn’t, much. At 6:00 a.m., I ran till the mountain woke. At 7:00, I packed Hollis’s lunch and wrote a note to her teacher: Please call if she seems overwhelmed. New paint tonight—she’s excited. At 8:30, I hugged her outside the school and watched her climb the steps with her fox in one hand and her backpack slipping off the other shoulder. She turned at the door and waved like she believed in tomorrow. Then she disappeared into noise and glue sticks.

At 10:00, I met Walsh and her tech, a woman named Priya with quick hands and the calm of someone who does high wire work without looking down. She taped the mic in a spot they’d tested for range and sweat and the way I moved my shoulders when I got ready to hit something. The transmitter settled under my shirt like a small heartbeat I could carry.

“Don’t touch it,” Priya said. “People always touch it.”

“I won’t.”

“You will,” she said, smiling. “We’ll yell at you if you do.”

Walsh laid out the choreography. “We’re on Channel B,” she said, tapping her earpiece. “Two units in the parking lot, one at the far bridge, me on the bench past the second oak. You’ll sit at the east picnic table. When she arrives, you stand to greet; you sit only when she sits. You keep her talking. You don’t accuse, you invite. ‘Help me understand’ is your line.”

“What’s our bail-out?” I asked.

“You stand and say, ‘I can’t do this here,’” Walsh said. “We come in. Do not say ‘police’ and do not put a hand on her. If she goes for your throat, which I’ve seen before, put your chair between you and back up.”

“I don’t hit women,” I said.

“I’m not asking you to,” she replied. “I’m telling you you’re not a shield. You’re a mic stand. We’ll take the contact.”

Naira arrived with a hard smile and a soft threat for anyone who made me a widow without a wife. She squeezed my forearm like she could tighten the wire with her fingers. “No improvising,” she said. “No catharsis. Catharsis is how men end up crying on curbs while women file motions.”

“I’ll keep my tears for paint,” I said.

At 1:53, I walked into Riverside Park. The October sun swung low, gilding the edges of leaves that had decided to go out loud. The river’s skin wrinkled around rocks. A kid threw a frisbee poorly while his dad pretended it was brilliant. I sat at the east table with my back to the parking lot and my eyes on the path.

At 2:00, Laurel turned into the lot in a black pickup that belonged to someone who thought his truck said more than his mouth. She’d dressed for pathos—jeans, oversized sweater, hair in a ponytail that had taken twenty minutes to look like it took two. She smoothed her hand over her stomach as she approached, a gesture as practiced as a signature.

“You wanted to talk,” she said, sitting without offering her hand. “Talk.”

I mirrored her posture, not her tone. “I’m not interested in court theater,” I said. “Hollis deserves a truth she can live with. I’m offering you a way to give it to her.”

“There is no truth but the one you’ve decided on,” she said, eyes cool. “You were always jealous of our life.”

“You mean the one you bought with my brother’s double shifts,” I said mildly.

She smiled—small and fake and polished. “He hated those shifts. He told me. He wasn’t cut out for family life.”

“Then why’d he build one?” I asked. “He asked you to marry him. He cried when Hollis was born. He taught her to blow on soup so she wouldn’t burn her mouth.”

“Don’t,” she said, flinching fractionally. “Don’t weaponize sentimentality.”

“I’m weaponizing memory,” I said. “Yours is different than mine. That happens to families when someone starts curating the story.”

She rested her elbows on the table and leaned in like we were sharing a secret. “You think this is going to be your big reveal?” she asked, amusement finally showing. “You think I don’t know you want me to say something you can repeat to your pet cop?”

It’s a particular kind of hell, hearing the inside of your shirt crackle when your pulse kicks a signal. I stayed very still.

“I didn’t come here with a cop,” I said. “I came here with the version of you that used to be a person.”

She rolled her eyes. “Save the sermon. You took my child. You turned people against me. You’ve been stalking my accounts like a pervert.”

“You left your child,” I said, first hard edge sliding into my voice. “At midnight. On a scooter.”

“I gave you the paperwork,” she snapped.

“You gave me a forgery,” I said. “With a notary stamp from last year and a signature that wouldn’t fool a teacher.”

“I did what I had to,” she said, cheeks flushing. “Brennan was going to take her. He threatened me. He said he’d tell the courts I was—” She stopped, recalibrated. “He was unstable. Depressed. You know how their father was. It runs in families.”

“There’s a file,” I said. “He started keeping notes. He wrote that if anything happened to him, he wanted people to know it wasn’t by his hand.”

She paled, just around the mouth. “Then he lied in his little book. He was a liar.”

“Or he knew you were making his beer bitter,” I said softly. “And he wanted a paper trail when you called it a fall.”

She recovered fast, but not fast enough for the recorder or the part of me that had learned to watch where a half-second lands. “He didn’t drink beer,” she said, then bit the inside of her cheek. “He—he did that week. He was stressed. Aunt Lila brought some over.”

The river moved, unstoppable. “I don’t want to crucify you,” I said. “I want to put my niece to bed without nightmares. If you tell the truth now, I’ll tell Hollis her mother made bad choices and then tried to make them right. If you don’t, she’ll learn from other people and she’ll never forgive you.”

Laurel’s eyes shone with wet that wasn’t regret. She looked past my shoulder, at the river, at a goose that had decided to be a metaphor. When she looked back, she had a face on I recognized from her wedding day: the one that said this is the version of the world that will now exist because I say so.

“Fine,” she said. “The truth is your brother was weak. He couldn’t handle a wife who wanted more than a man who smelled like sawdust. He couldn’t handle a woman men noticed. He cried. He begged. He made promises. He broke them. He took pills because he was dramatic, and then he took too many because he was sloppy. I found him. I panicked. I did what any wife would do when a man makes a scene—clean up and call for help.”

“After twenty-two minutes,” I said.

She bared her teeth. “I counted dosages,” she hissed. “I counted everything in that house and he still made a mess.”

“Dosages,” I repeated. “That’s a clinical word for someone who doesn’t have a prescription.”

“I was saving our child from a man who would have taken her,” she said, sitting back, victory flashing. “What would you have done? Let him take Hollis and raise her in your grandmother’s porch like some hillbilly widow’s project?”

The wire near my breastbone hummed like a trapped fly, the sound of a team leaning forward in the trees. Don’t push, I told myself. Don’t say the thing you want to say.

“What did you give him?” I asked, voice almost gentle.

“Relief,” she said. “I gave him what he was always asking for.”

The words were enough. Walsh’s voice in my ear was a breeze. “We have it,” she murmured, and it took everything I had not to turn toward the sound. “Walk her a little further.”

I leaned back, put my hands on the table so she could see they were empty. “Laurel,” I said, letting her hear her own name the way it sounded without worship, “I don’t hate you. I wish I did. It would be easier. You could have given up the man and kept your life. You chose the man and killed the life.”

Her mouth twisted. “You think you’re so noble,” she spat. “You and your uniforms and your stupid ‘principles.’ You left. You always leave. He stayed and suffocated me and then you came back and took my child like I was a—” She cut herself off, breath hitching. “I’m done talking to you.”

She stood. So did I. The geese muttered. The frisbee sailed past the dad and plopped into the river. The kid laughed and the dad swore softly, and it was the most human thing I’d heard in a year.

Laurel took a step back. For a moment, I saw it—the swing, the slap, the way she’d finish what she’d started in kitchen after kitchen. Then she smoothed her sweater. “Tell your pet cop to stop calling me,” she said. “Next time I’ll have a lawyer.”

“I didn’t call her,” I said. “You did.”

She went very still. Then she looked down, saw the small glint of metal at my collar, and made a sound I’d only ever heard once before—in a tent in Kandahar when a man realized his map had never been the terrain.

“You bastard,” she whispered.

“No,” I said, voice steady as the mountain. “Just a brother.”

Walsh appeared from behind the oak like she’d grown there—badge out, hand near her hip, calm enough to hold a bridge. “Laurel Mercer,” she said evenly, “I’d like you to come down to the station to answer some questions.”

Laurel’s eyes went wild. For a heartbeat I thought she’d run. Then she smoothed her ponytail like she could comb reality back into place. “I’m pregnant,” she said.

Walsh didn’t blink. “Then we’ll walk slow.”

They left her truck in the lot. I watched it sit there, empty and loud. Naira stepped out from the walking path and put a hand on my shoulder. It felt like a datum, a latitude that said you are here.

“You did good,” she said.

“I feel like I need a shower,” I said.

“You do,” she said. “But first we go to the DA.”

We spent the evening naming our evidence for people who turn grief into paragraphs. Assistant District Attorney Rebecca Santos listened to the recording twice, then once more with her eyes closed; when she opened them, something like anger had made them brighter. “This goes to a grand jury,” she said. “Tomorrow.”

“Will you arrest her?” I asked.

“When the case can wear handcuffs,” she said. “Not a minute earlier.”

When I finally drove home in the dark, the ladybug nightlight painted red moons on the hall. Hollis slept with an arm flung over her head, fingers curled around the fox’s ear. I stood in the doorway and felt the kind of tired that settles into your marrow and writes its name.

I went to the workshop. The dollhouse waited, patient. I uncapped the Moonflower and painted one small window frame, careful as a prayer. The brush whispered against wood. Somewhere in town, Laurel was learning the sound of a holding cell. Somewhere in my chest, something that had been clenched so tight it had become part of me loosened a millimeter.

I rinsed the brush, set it on the edge of the jar, and turned off the light.

Tomorrow would be for indictments and headlines and phone calls I didn’t want to take. Tonight, in a lavender room down the hall, a child breathed like a metronome. I matched it. I looked at the plan I’d written and added one more line in my own hand:

Tell Hollis her Daddy kept his promise. He didn’t leave. We found him.

The Baby Shower Arrest

Grand juries don’t speak; they gesture. When the phone rang at 9:07 a.m. and ADA Rebecca Santos said, “True bill on murder two, plus child abandonment, forgery, endangerment, obstruction,” that was the gesture. It said: We hear you. Now prove it in daylight.

“What’s your plan for the arrest?” Naira asked, already sliding files into a trial bag that had become an extension of her spine.

Santos’s voice was dry. “We’ll take her where she’s curated her audience. Community center, two o’clock. She’s throwing herself a baby shower.”

The world has a bleak sense of choreography. Two o’clock again. Same hour as the wire at the park. I pictured the pastel streamers and cupcakes piped with buttercream smiles. I pictured Laurel opening tiny onesies while women who believed her wept at the story she’d sold them: grieving widow, brave mother, new life, second chance.

“Do you want me there?” I asked.

“No,” Santos said. “You want to be a witness or a father?”

“A father,” I said.

“Then pick up Hollis at three. Take her for ice cream. Tell her the adults finally did their jobs.”

The community center sits in a valley of optimism—a place where Zumba and voting both happen on Tuesdays. At 1:53, Detective Sarah Walsh parked a block away and walked in like any other woman in a blazer. Two uniformed officers came in through the back hall that smelled like mop water and promise. Santos waited in the lobby, papers in a slim black folder like a blade.

Inside the rented room, Laurel stood at a head table, haloed by balloons that said BABY in gold letters thick as deceit. Pink and blue tissue paper spilled from gift bags. A banner read WELCOME LITTLE MERCER, weaponizing a name she’d already tried to erase. She wore pale blush—innocence as wardrobe—and rested one hand on her belly the way she’d practiced in the mirror. Kirk Blaine wasn’t there; he’d learned to stay out of rooms with rules.

The women of Asheville had come dressed for sentiment. Pastel dresses. Dangling earrings. The smell of punch and cake and floral hand lotion. When Laurel opened a silver rattle, they clapped. When she held up a tiny pair of socks, they murmured. When she laughed, they leaned toward her laughter.

Walsh let the room complete the scene before she stepped inside, badge in one hand, a plainspoken I’m sorry in the other. The sound of the door closing carried. Conversations thinned into curious silence.

“Laurel Mercer,” Walsh said, voice steady enough to hold a bridge. “You’re under arrest for the murder of Brennan Mercer.”

Time bent. A plate fell, broke, and kept breaking across the quiet. Laurel’s face drained, then filled, then rearranged itself into something she thought would save her—shock, innocence, affronted dignity. A tear placed with tweezers.

“I’m pregnant,” she said, as if pregnancy were a shield that could repel facts.

“We will walk slowly,” Walsh replied. “Please stand and put your hands behind your back.”

“What is this?” one of the women asked, half-rising. “There must be some mistake.”

Santos answered from the doorway without raising her voice. “It’s not,” she said. “We have a recorded confession and the evidence to match it.”

Phones came out because modern mercy is often documented. A dozen lenses watched as Walsh turned Laurel gently, efficiently, into a defendant. The click of cuffs sounded impossibly loud in a room that had moments earlier applauded a diaper cake.

“You can’t do this,” Laurel hissed, still performing to the room. “I’m a mother.”

Walsh’s eyes didn’t soften. “So was the woman who raised Brennan,” she said. “And she didn’t drown her husband.”

The officers guided Laurel through a forest of gift bags and sympathy that receded like a tide. Outside, the fall light was so clean it made edges look like declarations. Reporters who’d smelled a story before the cake had cooled lifted mics. Laurel lifted her chin.

“You’ll never prove anything,” she said to nobody and everybody. “Brennan was sick. He—”

Walsh shut the cruiser door with the kind of gentleness that is also final. The word SUSPECT slid across Laurel’s face as the window caught the letters on the opposite door.

Inside, the women exhaled in ways that held entire years. Some had believed her completely and now felt their belief turned against them. Some had suspected and were ashamed of the ease with which they’d chosen comfort over intervention. And some—two I noticed later—had the hollow look of women who had escaped men like Kirk and recognized in Laurel not a sister but a weather pattern.

I picked up Hollis from kindergarten at three, as instructed. She came out of the double doors with paint on her fingers and a paper crown that said AUTHOR because she’d dictated a story about a fox and a mountain. She held my hand tightly, and I wondered which adult had told her that holding on is a thing you can practice.

“Ice cream?” I asked.

She nodded, solemn and immediate. At the shop on the corner, she picked strawberry again because strawberry was a promise that had kept its word yesterday. We sat at a wobbly metal table on the sidewalk and let the day pass us like a parade we hadn’t paid to attend.

“Dad,” she said between careful licks, “did the people in the big building talk about Mommy again?”

“They did,” I said.

“Is she in time-out?”

“For a long time,” I said. “Because she hurt people.”

She considered this. “Good,” she said, and went back to protecting the cone from gravity. Children accept justice faster than adults. They haven’t learned how to negotiate with it yet.

We finished the cones and fed the last sweet bites to pigeons that strutted like minor nobles. Then I drove home and put on the kettle like normal was a thing we could cook.

“Can we paint my room now?” she asked, eyes bright.

“We can,” I said. “We’ll change clothes first. You can’t go to first grade with Moonflower on your hair.”

She laughed and thumped her fox against my hip like a toast. We spent an hour painting the second coat—her with a foam roller, me with an angled brush along the trim, both of us making the mistakes that would become stories. When the walls dried, we pushed the bed back and set the dollhouse on the dresser. The tiny shutters looked like they were about to blink.

“There,” I said, stepping back.

“Daddy would say the corners are good now,” she said gravely.

“He would,” I agreed. “We fixed them.”

The arraignment happened fast because Santos moved fast. Sunday morning, Laurel stood in orange behind glass in a courtroom that made people small. She’d lost the soft-blush costume. The pregnancy she’d weaponized had stopped granting her points. Her lawyer—Davidson, imported from Portland with a retainer built of fading favors—asked for reasonable bail. “My client is pregnant,” he said. “No record. Strong ties to the community.”

Santos stood without smoothing her skirt. “The state opposes bail,” she said, and laid the case on the table in short, hard lines: the recording from Riverside; the toxicology reanalysis showing benzodiazepine concentrations sufficient to fell a larger man; the timeline of calls and the measurable silence that followed; Hollis’s medical exam; the photo of a crumpled scooter abandoned at a ditch along Route 197.

Judge Reeves—gray hair, dryer wit, the same judge who had signed my emergency custody order—looked at the paper and then at the woman in orange and then at the gallery that had come to see whether what they thought they knew about the Mercers would be confirmed or edited.

“Mrs. Mercer,” Reeves said, voice even and unkind. “The evidence as presented suggests premeditation and a profound disregard for the welfare of your child. Bail is denied.”

Laurel made a sound that wanted to be a sob and came out a snarl. They led her away past the benches where strangers sat holding their coats tighter around their judgments.

Outside the courthouse, a reporter tried to shove a microphone at me. “Mr. Mercer, how do you feel?”

“Tired,” I said. “Relieved. Angry.” I stopped. “Focused.”

“Do you blame the police for calling it a suicide?”

“I blame the people who killed my brother,” I said. “And I thank the ones willing to change their minds.”

It wasn’t a sound bite; it was the only truth I could carry without dropping anything else.

Trial prep is a new life. It replaces your old one without asking if you were done with the parts you liked. There were depositions where men in suits tried to sandpaper the edges off my brother until he fit their narrative. There were motion hearings where Davidson tried to exclude the wire because “emotionally coercive,” and Santos sat there like granite and said, “Good law doesn’t scare this evidence.”

Dr. Rivera testified in pre-trial about Hollis’s condition when I brought her to the clinic. Her words—“systematic malnourishment,” “patterned contusions,” “healing fractures”—piled into a wall that no defense could grace away. The forensic tox rerun came back with numbers that turned the scale into a weapon. Rex found a hidden notebook Brennan had kept—dates, observations, small arrows that trembled where a man’s hand had tried not to. Found pills in cabinet. From Kirk’s script. Why does she have his meds? The last entry was a letter disguised as a log: If something happens to me, I would never leave Hollis. Please tell her.

We took that to Santos. She read it once and put her hand over it like she was blessing it. “You’ll read that at sentencing,” she said, not as strategy but as sacrament.

When trial began on a February morning that tasted metallic from the cold, the courthouse filled with breath and wool. Reporters came back because they sense arcs. People who’d never met my brother came because they recognize a story they could hold in their mouths later and say I was there.

Davidson opened for the defense with a painting of Laurel as a woman destroyed by a system that never saved her. “Battered woman syndrome,” he said, while offering exactly zero medical records that supported the claim. “Postpartum depression,” he said, while the timeline put the pregnancy with Kirk at the center of months of calculated steps. He tried to make Brennan both violent and absent, angry and neglectful, a man who had forced his wife to an edge and then dared her to jump. The jury listened politely because American juries are polite even to absurdity.

Santos opened with numbers and sentences that didn’t require adjectives to make them deadly. She put the recording on immediately, because sometimes you place your ace face-up so the other side knows how much walking they have to do. Laurel’s voice filled the courtroom, brittle and vain: I counted dosages. I counted everything in that house. A juror in the front row closed his eyes and shook his head, once, like he’d swallowed something that hurt.

Witnesses came like circles building toward a center. Tully Reigns, Brennan’s friend, testified to the bitter drinks and the frightened calls. Rex walked the jury through the money like a trail of oil. Dr. Rivera kept her voice clinical while describing harm that wasn’t. Santos held Brennan’s notebook with two hands and read the last line; you could hear the jurors breathing.

Laurel took the stand because narcissists often do. Davidson led her through the story they’d rehearsed; she cried in the right places and looked devastated at the right adjectives and kept touching her stomach like the jury might forget. Santos waited until the performance had warmed itself and then asked the only questions that mattered:

“Mrs. Mercer, can you explain the twenty-two-minute delay between your husband’s breathing stopping and your call to 911?”

“I was trying to help,” she said, but even she heard it.

“Can you explain the benzodiazepine levels?”

“I miscounted,” she whispered, and two jurors wrote that down like a confession.

Santos pushed the picture—tiny, heavy—across the lip of the witness stand. “And this?” she asked. “The scooter your daughter rode at midnight when you abandoned her.”

Laurel looked at it, and something hateful moved behind her face like a fish in shallow water. “She always wanted to ride it,” she said.

The courtroom exhaled a sound people make when they decide.

The verdict came in four hours because sometimes truth doesn’t need more time than that. Guilty on all counts. The word guilty has weight; when Reeves read it, it settled into my bones like sleep I hadn’t had since the knock at 12:03. Laurel made a small, human sound that might once have moved me. It didn’t now.

Outside, cameras asked for quotes like grief were a press release. I said nothing useful. Naira put her hand on my back the way she does when she’s reminding me a vertebra connects to a rib connects to a man who has to keep walking.

We drove home the long way so we could see the ridge line. Hollis had made a paper kite at school with a purple tail that matched the paint in her room. She ran it up and down the lawn while the light dragged itself toward evening. The kite lifted, bobbed, crashed, lifted again. She laughed each time it failed because someone had finally taught her failure wasn’t a beating.

I sat on the steps of my brother’s house—the one we were making ours letter by letter—and watched the kind of small miracle that goes unreported. In the workshop, the dollhouse waited for shingles. On the kitchen counter, the custody order waited for the hearing that would make it permanent. On my phone, a text from Santos: Sentencing in June. Bring the notebook.

Night came honest. I tucked Hollis in beneath her ladybug comforter and kissed her forehead and told her for the thousandth time that her father hadn’t left, that he’d been taken, and that we had made sure the taking was named.

“Dad?” she said as I reached the door.

“Yeah?”

“I think the mountain is quieter now.”

“Me too,” I said.

She closed her eyes. I turned off the light and left the door cracked the way Brennan used to for me when nightmares couldn’t find the gap.

In the workshop, I put the last of the shingles on the dollhouse roof. The glue set. The little house looked like it could hold. I set it on the dresser in the lavender room and stood there a moment, hands on the frame, feeling the weight and the lift.

Justice doesn’t feel like triumph. It feels like space. It feels like air returning to a room.

Tomorrow we would start something else: a program for kids who needed to use their hands to remember they were here. I would teach them to plane edges and join corners and measure twice, cut once. We would build benches sturdy enough to hold other people’s weight.

And I would answer the knock, whenever it came, because 12:03 had taught me that doors matter more than locks.

News

My Husband Kicked Me in Front of His Friends—And My Revenge Was Not What They Expected CH2

By the time the elevator eased open on the executive floor, the building had learned to be quiet around me….

The comedy star who impersonated a White House official has the Internet abuzz with the rumors she spreads along with it CH2

In the high-stakes world of politics, where every statement is analyzed and every public appearance is scrutinized, moments of levity…

My Brother Broke My Ribs—Parents Said ‘Stay Quiet’ But My Doctor Refused… CH2

The Match and the Crack I didn’t mean the joke to land like that. “I’ll get them next time,” I’d…

Fox & Friends: Brian Kilmeade’s ’69’ Flub Has Cohosts Cracking Up CH2

In a recent episode of the popular morning show “Fox & Friends,” host Brian Kilmeade found himself in a light-hearted…

My Son Sent Me A Box Of Cookies For My Birthday, But I Gave Them To His MIL Then… CH2

The Box on the Counter The first time the phone rang, I thought the call had dropped.It hadn’t. “You gave…

I Discovered My Husband Was Planning a Divorce—So I Moved My $500 Million Fortune a Week Later CH2

The Whisper Behind the Door My name is Caroline Whitman, and for most of my thirties I treated happiness like…

End of content

No more pages to load