The Decision That Wasn’t Mine

The day my life got small started with a sentence that sounded like a favor but landed like a verdict.

“From now on,” Kevin said, laying his fork on the table as neatly as a judge sets down a gavel, “focus on the house.”

There was a smear of egg on his plate, sunlight on the countertop, and Deborah—my mother-in-law—sitting at the other end like she always did on Saturdays, supervising my marriage. She wore that Hoover Dam smile, wide and fixed, built to hold back floods. “It’s for the best, Meline,” she said. “A good wife’s place is at home.”

Until then, Kevin had nodded supportively while I fumbled my way through the first months of cashier shifts at the supermarket. “Try it,” he’d said. “See how you like it.” We both knew he meant until Mom says otherwise. Now “otherwise” had arrived, coiffed and perfumed, twirling a teacup like she could stir my life into a shape she preferred.

“I’ve finally gotten used to it,” I told him. “I like working. Let me try a little longer.”

Kevin didn’t look up. “Please. Enough. Just do as you’re told.”

I want to say I stood up and said no. I didn’t. My father used to say families are machines; everyone has a part. I’d spent years greasing gears that ground me down. The next morning, I turned in my resignation.

If I couldn’t be who I wanted, maybe I could be what they wanted and get a little peace for my trouble. I told myself I’d become better at housework, that someone would finally say I was doing a good job. That someone never arrived.

Instead, I got pregnant.

When I first held our daughter, the world reorganized around a tiny pair of lungs and the warm weight of her on my chest. We named her Nancy, after my grandmother who could fix a radio with a butter knife and curse a thunderstorm into a drizzle. I thought I’d discovered a part of myself no one could touch.

Deborah touched everything.

“You’ll spoil her if you hold her that much,” she said, hovering like a hawk over a pond. “That outfit isn’t good for a baby’s skin. Don’t nurse her so long or she’ll never sleep.”

Kevin’s contribution to parenting was a shrug. “You’re the mother. Of course it’s your job.” He said it like a compliment and used it like a key to lock himself out of anything messy.

I muddled through. Every smile from Nancy was a life raft. Every soft exhale against my neck was instruction I could finally trust. And when she turned six and school swallowed part of her days, I tried something radical: I took a part-time job bagging groceries at the nearby market.

By then, I could run our household on muscle memory. There wasn’t anything left on my list that could be used to justify saying no. Kevin didn’t object. “As long as the house doesn’t suffer,” he said. I took that as permission, not a warning.

Those hours at the register stitched me back together. “Thanks,” customers said, and the word landed where it needed to land. Co-workers asked about my day and waited for the answer. The paycheck was small, but I folded it into a savings account with Nancy’s name on it and watched it grow like a hidden garden.

Then Kevin’s father died, and grief rearranged the furniture in Deborah’s life and thereby in mine.

“She can’t be alone,” Kevin said one evening while I was trimming green beans at the sink. His voice had that soft edge that meant Mom said, but he wanted credit for thinking it too. “We’ll support her.”

“Of course,” I said. I thought he meant the same thing I meant: help with forms, drive her to appointments, drop off casseroles like everyone else. “We’ll send her some money from our budget,” I added. “We can figure that out.”

Kevin held out his hand. “Give me your wages. I’ll use that for Mom.”

I dried my hands and turned. “That’s the money I’ve been saving for Nancy.”

“How can you say something so cold?” His face arranged itself into shock. “Are you even human?”

“You don’t have to say it like that.”

“I’m only saying we have our own living expenses and circumstances.”

I could list every way the math didn’t work. He could list every way it did—in a universe where my labor was paid in gratitude and his mother’s needs were astronomical constants. When I refused, he got up from the table, disappeared, and returned with papers he’d kept in a drawer like a talisman.

He slapped them down. “I should have done this years ago. Sign. Leave the kid and get out. I don’t ever want to see your face again.”

Divorce had been his favorite threat, waved like a flyswatter whenever I buzzed near boundaries. It had worked because of one word: Nancy. I pictured her face and felt my spine soften into apology. “I’m sorry,” I said, because sorry had become the oil that kept our machine from smoking. “It was my fault.”

“That’s better,” Kevin said, relief unearned and obvious. “You should have done that from the start.”

I wanted to hate him without footnotes. I couldn’t quite manage it then. He loved Deborah the way a drowning man loves a life ring—fiercely and without curiosity about how everyone else in the boat feels. I tried to convince myself there was virtue in understanding. What there was, mostly, was exhaustion.

He brought up divorce constantly after that. When I burned a sauce. When I said no to an extra expense. When I wanted to take Nancy to my parents’ house instead of Deborah’s for a weekend. I became an expert in silence, in dissolving into whatever version of myself would offend him least. My private deadline—my talisman—was Nancy’s adulthood. When she graduated college and had her own apartment, I promised the woman inside me we’d talk again.

When Nancy went to university, Kevin started coming home late. “Busy at work,” he said, and I nodded at the train schedule I wasn’t allowed to scrutinize. He came home a few times a week. At first I imagined car crashes and affairs and disaster. After a while, I realized something difficult: it was easier when he wasn’t there. No criticism. No running commentary. The house made a different kind of sound—a sound I wanted to learn.

There was one tradition that never broke, no matter how badly the rest of us cracked: we spent Independence Day and Christmas at Deborah’s house. Nonnegotiable. “A daughter-in-law belongs with her husband’s family on holidays,” she’d said the first year like it was a verse in a hymnal. It became muscle memory. It became a rule pressed on my forehead with two fingers every summer and winter: You belong to us.

This summer, Nancy couldn’t make it. “Work,” she said regretfully. “Rain check. Promise.” I packed anyway. Kevin loaded the trunk like a man moving under orders. I looked at my reflection in the side mirror and tried not to think about the version of me I’d promised to resurrect.

We pulled into Deborah’s driveway in an afternoon swollen with heat. The air over the pavement shivered. Kevin did the thing he always did: carried in one bag, sank into the sofa, and turned on the TV with the concentration of a surgeon. Deborah skipped greeting and went straight to command.

“The shed needs cleaning,” she said. “It’s filthy. Go now.”

Like I was a teenager caught sneaking in after curfew. Like I hadn’t just driven three hours to be there. Like it wasn’t 95 degrees and the shed wasn’t an oven.

“All right,” I said, the way I always did when I was too tired to fight.

Inside, the shed smelled like hot dust and old wood. A thermometer tacked to a nail declared Over 95°F like a dare. I laughed to myself—one short bitter exhale—and got to work. There’s a tilt you do when you say, I’ll just get this done. It puts your head down and turns your eyes into blinders.

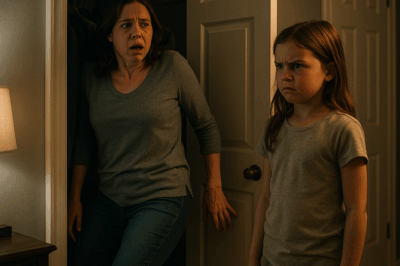

Fifteen minutes later, the light dimmed. The door scraped. Then a sound I will hear in dreams for the rest of my life: click. The lock.

“Hey!” I called, the word tasting like metal. “Please open this.”

Deborah’s voice floated in, cheerful, as if through a wall of cotton. “We’re going out to eat as a family. You stay and clean properly.”

I heard Kevin’s laugh. I heard a car door thunk, an engine catch, tires on gravel. Silence fell like a blanket over a birdcage.

At first, you tell yourself it’s a joke. Then you count the seconds and realize jokes don’t last this long. Sweat ran into my eyes. Air refused to be air. My phone was in my bag inside the house. I had no way to call for help.

Think. I scoured the back corners until my fingers brushed cold metal—a toolbox. I tipped it over and a hammer thudded onto the floor. The wall answered like a drum when I hit it the first time. The second time, it sounded thinner. The third time, a board loosened with a groan that sounded like permission.

I pried and pried until a slice of light blindsided me. I wedged my shoulder into the gap and forced my body through, splinters grabbing skin as if to say Are you sure?. The outside air, brutal as it was, felt like blessing. I staggered toward the house.

Inside, the cool of the A/C wrapped itself around me like a towel. My knees buckled. For a minute or an hour—I couldn’t tell—I sat on the tile and jolted in and out of something that wasn’t quite sleep.

When I finally stood, it was getting dark. The clock on the stove blinked 5:53. The house was empty of the people who’d put me in a box like a seasonal decoration. The world was full of people who would tell me it wasn’t that bad.

My phone rang from my purse. Unknown number. I reached it just in time to miss it. The voicemail icon pulsed.

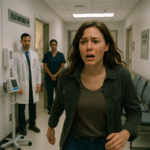

“This is St. Matthew’s General Hospital,” a woman’s voice said, crisp and tired, like she’d been reading bad news for hours. “Mr. Kevin Brown and Mrs. Deborah Brown have been in a traffic accident and were transported here.”

My body moved on its own. I grabbed my keys. The voice continued.

“We regret to inform you that both of them have passed away.”

I stood in my kitchen, hand over my mouth, and discovered a complicated truth that rode in on the news like a second ambulance: part of me felt relief. The other part felt nothing. Then the nothing broke and everything poured in like water through a window.

I called a taxi. I rode through dusk, passing the stretch of highway lit up with blue and red and the metal confetti of accidents. Even the driver muttered, “That’s terrible,” and crossed himself, and I found myself doing the same though I hadn’t prayed in years.

The hospital lobby was packed, the air tense with families in emergency. A nurse at the desk called my name before I could say it. She had the face of someone who had been told to fix a mistake.

“I’m incredibly sorry,” she said. “There was… confusion on the line. They aren’t dead. We immediately left a correction on your voicemail—did you receive it?”

I stared. “No. I—no.”

“They’re both alive,” she said, voice settling into the tone medical staff get when they ferry people from cliff edges back to plains. “Serious injuries. Conscious. The doctors can explain.”

The doctor’s words washed over me and arranged themselves into headlines: long hospitalization, possible long-term care, bedridden cannot be ruled out, we’ll need to discuss caregiving and future living arrangements. Each phrase put two more stones in my pockets.

“Please proceed with the admission paperwork,” the nurse said. “We’ll—”

“I will no longer have any involvement with those people,” I heard myself say. The sentence surprised even me with how cold it sounded. It wasn’t thrown. It was set down.

They blinked at me, taken aback. I added one request, one last act of… what? Mercy? Irony? I asked that they be placed in a private room together, side-by-side. I signed the form. Then I turned and walked out into the night a woman who had just buried one life and hadn’t yet learned how to hold the new one.

When the taxi door shut, I let my head thump against the window and told the dark what I hadn’t dared whisper in my kitchen: “If they had died, I would have been free.”

Alive, they were a test.

I decided to choose me.

And for the first time since I’d put my name on a resignation letter years earlier, I made a decision that belonged only to me.

The Call, the Papers, the Room

Kevin called a week later, his voice pitched just above demanding, just below desperate.

“Why the hell haven’t you come?” he barked. “We’re in serious condition here. Get over here now.”

In the background I heard the hospital—monitors beeping like impatient birds, a cart squeaking, someone’s TV murmuring a game show. He still said we like that—Deborah and Kevin as an organism with two heads, a plural that ate everything.

“I’m tied up,” I said. “I’ll come when I can. I have something to tell you.”

“What? You listen here—”

I hung up. The click felt like dropping a stone into a well and not waiting to hear it hit water.

For two weeks, I stacked my life into boxes. The living room became an atlas of cardboard countries labeled with black marker—BOOKS, KITCHEN—FRAGILE, NANCY (and beneath it in smaller letters, KEEP). I rented a storage unit. I signed a lease on a one-bedroom across town with a window that looked at trees instead of Deborah’s opinions. I went to the courthouse with my driver’s license, my marriage certificate, and a spine.

“I’d like to file for divorce,” I told the clerk, and expected thunder. There was only typing.

The woman behind the glass had a kind face and a tattoo of a bird flying out of a cage. “Uncontested?” she asked.

“Soon to be,” I said. “He’s waved papers in my face for years. He just never expected me to pick them up.”

She slid forms to me, explained timelines, pointed where I should sign. Her voice was a small light in the tunnel. When she passed me the stamped copy, it felt less like paper and more like a key.

Two weeks after Kevin’s call, I walked into St. Matthew’s with a tote bag and a plan. The nurse at the desk recognized me. “Room 713,” she said, with a neutrality that felt like respect and not indifference. “You requested a private room. We honored that.”

I thanked her and stepped into an elevator that smelled faintly of antiseptic and hope. The doors opened to a hallway of doors. Inside Room 713 were two beds, side-by-side like a photo of a marriage from a different century. Deborah lay in one, pale and still, an IV stand making a small forest of tubes. Kevin sat in a wheelchair, a brace cinching his chest, his leg elevated. They turned toward me with the practiced coordination of a team that had trained for the event of my arrival.

“You disgrace,” Deborah said immediately, voice stronger than her body. “Three weeks. You left us to rot.”

I smiled a smile that would have shocked the woman I was a month ago. “I was busy,” I said. “I had a shed to clean.”

Her cheeks blazed. “Even now, you dare—”

“I’m joking.” I shrugged. “Honestly, I had so many things to deal with. You weren’t high on the list.”

“You really are useless,” she said, volume rising. “Hopeless. Inefficient. You can’t even—”

“She’s right,” Kevin cut in, as if this were a chorus and his part was harmony. “What kind of wife abandons her husband? Can’t you at least start by apologizing?”

I looked from one to the other and thought about the interesting geometry of people who have never once asked themselves if they might be wrong.

“I’m not your wife,” I said. “And I’m not your daughter-in-law.”

Silence hit the room like a warm front. They blinked, frowned, recalibrated what they thought this conversation was supposed to be.

“What are you talking about?” Kevin demanded.

I reached into my tote and slid a stack of documents onto the tray table between us. The top sheet was a copy of the divorce acceptance, the court seal shining like a small moon.

“I filed,” I said. “It’s processed.”

He grabbed for it like a man who suspects a trick. His eyes skittered across the words. His mouth opened and closed.

“You can’t—”

“You’ve shoved divorce papers at me for years,” I said. “You’re the one who taught me where the forms are. You just never thought I’d fill them out.”

I turned to Deborah, who had gone still in that particular way pride goes still when it knows it has met something it can’t bully.

“The day you locked me in that shed,” I said quietly, “I decided I didn’t want to die in a box someone else put me in.”

“You’re the lowest,” she snapped, as if saying it could return all the furniture to its original places.

“Am I?” I met her eyes and didn’t look away. “You locked me in a tin can on a ninety-five-degree day so you could go to dinner without me. You call that ‘family’? You call that ‘tradition’? I call it attempted cruelty. And I’m done serving it.”

“Don’t be ridiculous,” they said together, because of course they did.

“As part of the divorce,” I continued, “I’ll be demanding compensation.”

“For what?” Kevin sputtered. “You’re not in a position—”

“Deborah,” I said, and took out my tablet. I tapped the screen. A video filled it—grainy, yes, but clear enough. Deborah’s voice filled Room 713, crisp and cold even through a phone mic: You’re useless. Do it again. Not like that. God made you clumsy. The camera shook occasionally, like the person holding it was angry and trying not to be.

Deborah’s face in the bed drained of color. “What is that? Who filmed—did you put hidden cameras in my home?”

“Nancy filmed it,” I said. “Your granddaughter. She pretended to be scrolling whenever you tore pieces off me and recorded the truth because she couldn’t stand it anymore. When she moved out, she handed me a flash drive and said, ‘Mom, you don’t have to stay. Use this and leave better.’”

“I treated that child like a princess,” Deborah whispered, like the sentence could absolve a hundred others. “She loved me.”

“She watched you insult her mother,” I said. “That’s how you kept her love: by making me smaller to make yourself bigger. The lawyer said this is solid. The word he used was pattern.”

Kevin’s mouth thinned. Then he shifted into what he thinks is reasonableness. “Mom went too far,” he said, as if this were a revelation. “It can’t be helped. You’ll just have to pay, Mom. I sent you money before; you’ll be fine.”

Deborah turned on him. “How can you say that? I’m on a pension.”

“Mom, you’re at fault,” he replied, performing what he thought was balance while keeping himself off the scale.

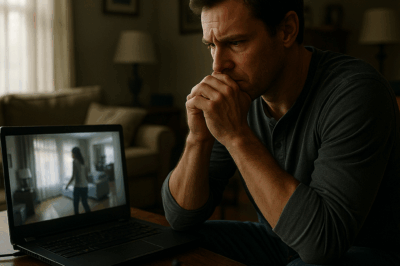

I slid another photo across the tray. It was glossy, printed from the drugstore like a souvenir: Kevin with a woman outside a bar, his grin too wide, his hand too familiar on her lower back. A second photo, the motel’s neon sign reflecting in a puddle at their feet, his head bent toward hers like ritual.

“No,” he said immediately, reflexively. “No, that’s not—”

“It’s you,” I said. “Two years ago. Within the statute of limitations.”

“How—”

“I followed you once, when you were ‘busy at work’ on a night Nancy had a late study group and the house felt like a question. You think you hide things. You don’t.”

His jaw worked. Words failed him. He looked exactly like a child caught and forced to ask his tongue for new vocabulary. It didn’t come.

I placed an envelope on the tray with a small respect I didn’t feel. “And this,” I said, “is the invoice for your August hospital expenses.”

He slid out the paper, scanned, and choked.

“Twenty thousand dollars?”

“Private room at my request,” I said. “My final gesture as your wife.”

“You expect us to pay this?” Deborah asked, tears springing as easily as they always had when she needed them. “You did it. You pay.”

“I suggested a private room so you could be comfortable,” I said. “I separated our lives so I could be free. Both choices were mine.”

“We can’t handle procedures in this condition,” Kevin said, gesturing at his body as if it were proof of innocence and not simply consequence. “Insurance is impossible.”

“It’s also the paperwork you’ve always said good wives do without complaint,” I said. “Now you’ll learn how to do things you thought you’d outsourced.”

Their faces changed the way weather does when a front moves in—rage tumbling into panic, panic crashing into bargaining. “We’re sorry,” Deborah sobbed suddenly, hands over her face like Ophelia auditioning for the part she was born to play. “We never meant—”

Kevin wheeled himself closer. “I was wrong,” he said. “About a lot. You’ll forgive me, won’t you?”

I looked at the two people who had built a system and called it love because they liked what it demanded of everyone else.

“I want to know one thing,” I said. “Did you ever like me? Even at the beginning?”

Kevin tried honesty because manipulation had failed. “You didn’t have the education other women had,” he said slowly. “You seemed… obedient. I thought once we were married, you’d do what I said.”

“What is that supposed to mean?” Even Deborah looked rattled.

“It means,” I said, “you picked me because you thought I’d be easy to use.”

Deborah stared at the ceiling, and when she spoke, it was softer than I’d ever heard her. “He’s my only son. I poured everything into him. When you married him, it felt like you took him from me.”

“And when you saw me manage the house and work part-time, you realized I didn’t need you to tell me who to be,” I said. “So you tried to make me need you. With insults. With rules. With money that wasn’t yours to claim.”

Silence spread. The monitor beeped. A cart squeaked by in the hall. In an old life, I would have filled the silence with apologies and offers. In this life, I let it say everything.

I slung my tote bag over my shoulder.

“From here on,” I said, “you’ll figure it out without me. The paperwork is filed. The claim will be served. I wish you good care.”

“Please don’t go,” Kevin blurted.

I paused at the door and turned back long enough to teach my mouth a new sentence and my heart a new rhythm.

“I already did.”

I stepped into the hallway and shut the door gently, the way you close a room where someone is trying to sleep. The elevator came. I went down.

Outside, the evening was the kind that makes you think the world could be remade if someone made one small better choice and then another. I drove to my new apartment and carried in a box labeled KITCHEN—KEEP. Inside was the ugly mug Nancy painted in second grade, lopsided and glazed the color of an ocean that never existed. I poured tap water into it and drank it like a communion.

The next morning, I met with Evan. We sat at his conference table and put numbers on the table like cards. “Twenty thousand for infidelity,” he said, pen tapping. “Twenty for harassment and intentional infliction of emotional distress. We’ll document everything.”

I slid the tablet across. He watched three minutes of Deborah’s greatest hits and didn’t hide his wince. “I’ve seen a lot,” he said. “This is… abundant.”

“Abundant,” I repeated, because sometimes synonyms are a kind of comfort.

“We’ll file this week,” he said. “And we’ll ask for distribution of the house proceeds to be clean half, half. He’ll try to keep the equity. He won’t succeed.” He softened. “You did the hardest part.”

“No,” I said. “I did the first hard part. Now comes the next.”

He nodded. “Then let’s do the next thing.”

When I left, the sky had chosen blue, decisively, like it was tired of ambiguity. I picked up flowers from a street vendor—sunflowers, because sometimes it’s okay to choose the obvious joy. I put them in a glass on the windowsill and texted Nancy a photo.

Mom: New place. New view. Your mug survived.

She texted back immediately.

Nancy: You’re shining. You made the right choice. Come over tonight? Bring that mug.

I breathed in, breathed out, and practiced not apologizing for anything.

What We Keep, What We Return

The paperwork went out like arrows I’d spent years fletching. Service of process doesn’t feel like justice when you watch it happen. It feels like a doorbell. A knock. A man in a polo who will forget your names as soon as you shut the door. I didn’t see any of it. Evan called to confirm delivery, and I said “Thank you” and wrote the date on the inside cover of a notebook I’d bought for a life I hadn’t believed I’d earn.

The house we’d lived in—the one with the chipped blue shutters and the faint line on the doorframe where Nancy’s height is still marked in pencil—went on the market. The day the sign went up, a neighbor texted me a photo of it standing in the yard like a white flag.

“Mixed feelings?” Jo asked that night when we walked past it on our way to tacos.

“I thought I’d sob,” I said. “I didn’t. I stood in the street and thought: Objects are not home.”

At closing, the numbers arrived in a PDF that would have made younger me dizzy. Half. Mine. Clean. I stared at the screen and tried to teach my heart that having what you’re owed isn’t the same as stealing.

Kevin called once more. His name lit my phone like a flare. I let it go to voicemail. In it, he did the thing he always did—started with anger, veered into shame, crashed in bargaining. “We can work this out,” he said. “Think about what you’re doing to our family.”

I didn’t save it.

Deborah didn’t call at all. A mutual acquaintance sent word through the grapevine that she’d been discharged and moved back to her house, where Kevin had installed grab bars along the hallway and a new recliner that lifted and lowered with a remote. He had become the caregiver he’d once assumed is a woman’s default assignment.

The report came with a garnish: “They fight all the time. It’s exhausting for everyone within earshot.”

I put the phone down and went to my closet. At the back, in a shoe box, were the last few items I’d kept for the part of me that wrongly believed memory equals obligation: a photo of my wedding day where I looked like a version of me who thought promises alone guarantee kindness, a program from a Christmas service where Deborah squeezed my arm as if affection could be checked out of the church charity box and brought home, a napkin with Kevin’s name scrawled on it from a bar on the night he proposed, cocktails and declarations loud enough to drown out the warning bells in my chest.

I sat on the floor and let myself miss a version of a life that never quite existed. Then I put the box in the trash.

At the new apartment, I hung art that wasn’t chosen for how well it matched a couch. I bought sheets that felt like summer on purpose in December. I invited noise into the rooms—Nancy’s laughter, Jo’s voice on speaker while we cooked, a playlist that was all horns and women telling the truth. The silence that followed after they left wasn’t empty anymore. It was space.

There were practicalities. Insurance forms. Notice of name change on accounts. The way grief insists on showing up when you’re printing, not when you’re ready. I filled boxes with receipts and put them on the closet shelf. I labeled them KEEP and RETURN.

KEEP: The mug, sunflowers, the smell of bread in the oven on a Sunday because no one told me to bake it.

RETURN: The habit of explaining myself to people who have no intention of understanding. The reflex to say sorry for existing.

Nancy came over and saw the piles. She carried the RETURN stack to the curb with ceremony, as if she were escorting an honored guest to a car. “I filmed those videos because I wanted proof for you,” she said. “But also for me. I needed to know I wasn’t crazy.”

“You saved me,” I said.

“No,” she said, her jaw set in a way I recognized. “You saved you. I just held the camera.”

She’d gotten a job offer across town and signed the lease on a cozy apartment with too few outlets and just enough light. We took a measuring tape and a bottle of seltzer and spent a Saturday determining where a couch could fit if it didn’t know it was supposed to go along the longest wall. We were building lives, brick by careful brick, and telling each other where to put the mortar.

On a Monday in October, Evan called. “Settlement offer,” he said. The number for infidelity was as asked. The number for harassment was lower, attached to a statement that made me laugh out loud—There was only normal mother-in-law behavior. Evan had already drafted a reply.

“Your call,” he said.

“I don’t want a trial,” I said. “I don’t want a courtroom to be the last room we share. I want to go to the farmer’s market on Saturdays and not wonder if I’ll run into a cross-exam.”

“We can push them higher,” he said. “They know they’ll lose more in front of a judge.”

We pushed. They budged. We settled. Papers came. I signed.

When the wire hit my account, I sat on my bed and stared at the numbers like they were a language I didn’t speak. Then I closed the banking app and opened Zillow. Not for a house—I wasn’t ready to pour myself into an address again—but to look at little cottages with porches that could hold a chair and a cup of coffee. It’s good to have pictures for the future, even if you don’t plan to buy them yet.

I took a walk to the lake that afternoon. The path was a ribbon unraveled by kids on bikes, dog walkers, teenagers practicing how to kiss in public and not care who knew. I passed a shed behind a townhouse—ordinary, beige, door hanging open, a rake leaning against the wall. I stopped and touched the frame with two fingers, as if it were a gravestone or a saint’s sleeve. Then I kept walking.

In December, my phone lit with a call from the hospital’s billing department. I braced for some administrative disaster. The woman’s voice was cheerful to the point of suspicious. “Just calling to confirm the private-room invoice was paid in full,” she said. “Mrs. Brown took care of it yesterday.”

“Which Mrs. Brown?” I asked out of habit and then smiled at the ceiling because, for the first time, the question didn’t include me.

“Deborah,” she said. “Is there anything else we can help you with?”

“No,” I said. “Thank you.”

I baked a cake for no reason and ate a piece in the middle of the afternoon under a blanket while the world outside tried to become winter. It was too sweet. I ate it anyway.

Christmas arrived like it always does—too early, too bright. There was a time when that meant packing for Deborah’s, going through motions labeled tradition on a box that actually contained control. This time, I put a small balsam on a crate and let the lights be crooked. Nancy and I watched ridiculous movies and texted Jo running commentary. When “carols with the Thompsons!” popped up on the old group thread Deborah used to manage like a captain with a clipboard, I muted it.

On Christmas morning, I woke to a ding. It was a photo from a number I didn’t have saved. Deborah on a recliner, a bandage still visible at her collarbone, Kevin beside her with a tray across his lap. The tree behind them was perfect—every ornament in place, tinsel not daring to misbehave. The caption read: We’re fine. Merry Christmas.

I stared at it, surprised less by the pettiness than by the small prickle of relief I felt. They were someone else’s problem now—their own. I typed Merry Christmas and sent it because I believe in endings that aren’t made of gasoline.

After New Year’s, Nancy and I took the tree out to the curb. We swept needles. We ate leftover cake. She hugged me at the door and said the thing she says now without thinking: “Mom, you’re shining.”

“I am,” I said, and realized it was true, no brave face required.

In February, I put on lipstick and went to three job interviews. The third one had a hiring manager who asked about my favorite book. I told her about a dog-eared copy of a novel I’d carried around for years, underlining sentences about women who left rooms and discovered whole cities outside them. She smiled. Two days later, she called. “Can you start Monday?”

At the supermarket where I’d once bagged groceries, the manager who used to assume my schedule could stretch to fit anything stopped me in the aisle. “Heard you landed something full-time,” he said. “Good for you.”

He meant it. I loved him for that simple decency I didn’t have to coax.

The new job was an office with windows and coworkers who didn’t blink when I said I can’t stay late today. The paycheck had commas in different places. I sat at a real desk and wrote emails that didn’t apologize for existing. At lunch, I walked outside and let my face learn the midday light.

Once, on a Thursday, I passed a woman in the lobby who looked familiar in the way people look familiar when they share a story with you. She was smoothing her blouse, eyes on the floor, voice low as she spoke into her phone. “Mom says it’s my fault,” she was saying. “But I know what I heard.”

I held the door for her. She looked up. Our eyes met. That was all. Sometimes that’s enough.

Spring came and put green on everything. The world looked like a thing that had been forgiven. I did not believe in miracles, but I believed in trying something that looked like one from a distance.

I invited Jo and Nancy to dinner. We ate outside because it felt like a rebellion against every winter. After, Nancy pulled out her phone and showed me a photo she’d taken years ago without telling me: me, washing dishes at Deborah’s, the window framing a slice of yard, my face tired and bent but not broken.

“I used to look at this when I needed courage,” she said.

“What do you look at now?” I asked.

“You,” she said simply. “In your own kitchen.”

The night ended with the three of us on the couch, feet tangled, a bad singing competition show on TV. The host asked a contestant what she’d do if she won. The contestant said, “Buy my mom a house.” We laughed and I said, “Don’t you dare,” and Nancy said, “Shut up, I’m buying you a porch swing,” and Jo said, “I’ll supervise,” and there it was—the life Deborah never made room for and I’d had to build myself.

There’s a version of this story that ends with a public triumph—a judge’s gavel, a viral post, a victory speech. Mine ends in a smaller place. A kitchen. A notebook with the word KEEP written on the inside cover and no room left for apology.

The last thing I put in that notebook was a sentence I’d been practicing: I am not disposable. I wrote it twice in the morning and once before bed until it stopped feeling like audition and started feeling like truth.

On the anniversary of the shed, I drove past Deborah’s street and kept going. I stopped at the park, sat on a bench, and faced the sun like a sunflower. I took a photo. I sent it to myself. I set it as the lock screen on my phone.

When my phone rings now, it’s Nancy or Jo or someone who knows how to speak to me like I’m a person and not a possession. I answer.

When the unknown numbers come, I let them go to voicemail. I’m done collecting proof that I’m right. I’m busy living like I don’t need to be.

A Door That Opens the Right Way

April put green on the trees like it was signing its name. At lunch I walked the block the long way, past dogwood blooms drunk on themselves and kids shrieking on a playground like sirens for joy, and thought: this is what my life sounds like without someone else’s schedule in it.

The new job fit like a pair of shoes I didn’t have to break in. I learned my coworkers’ coffee orders and they learned that when I said I needed to leave at five, it didn’t come with a paragraph. My manager—blessed be her boundary-respecting heart—once stuck her head into my cubicle at 4:58 and said, “Get out of here; your life is bigger than this spreadsheet,” and I almost cried at the simple mercy of it.

In May, Nancy invited me to her place for tacos and IKEA assembly. Her apartment was a hymn to mismatched chairs and sunlight. We put together a bookshelf while a playlist warred between her pop and my old soul. She held up a tiny Allen wrench. “This is the tool that keeps the world together,” she said. We laughed until one of the shelves clicked in—perfect, inevitable, held by the simplest thing.

“Mom,” she said, sliding books into a row, “you’re different.”

“Older,” I said.

“Brighter,” she said.

I opened my mouth to argue, and didn’t. “Maybe,” I said. “Maybe I’m finally lit from the right side.”

A week later, the door I had assumed was sealed knocked itself. An unfamiliar number buzzed my phone twice then texted: This is the hospital social worker assigned to Mrs. Deborah Brown. She gave permission to contact you regarding discharge planning.

I stared at the words like they were in a language I’d almost forgotten. Discharge planning. Which is the medical way to say someone is about to become someone else’s problem.

I typed I’m not her caregiver and deleted it. I typed You have the wrong number and deleted that too. I set the phone face down and looked out the window until the tightness in my throat became something I could swallow.

They called again, this time leaving a voicemail. The social worker’s voice was soft, professional, practiced at guiding people through messes they didn’t make. “We’re arranging home health,” she said. “Given family dynamics… Mrs. Brown asked that we… contact you. We understand if you cannot participate. If you have resources you would recommend, that would be appreciated.”

Asked that we contact you. I could hear Deborah saying it, chin lifted, a woman who had never considered the possibility of a no from me. I could also hear a tremor. Because tremors appear when the ground has moved.

I called back. “I won’t be involved,” I said. “But I can email a list.” I sent a concise index I’d quietly collected when the divorce started—caregiving agencies with decent ratings, a pro-bono legal services clinic, the number for a county caseworker who told me on the phone once that people survive all kinds of families and she had seen worse than mine.

I put my phone down and made tea. A small mercy wouldn’t cost me my life. Not anymore.

Two days later, the grocery store pulled me into a reunion I hadn’t scheduled. I was comparing prices on strawberries when a voice behind me said my name like a question.

“Meline?”

I turned the way you turn toward a storm you’ve lived through and can now predict by smell.

Kevin stood by the endcap display of chips, thinner than before, a stoop in his shoulders that wasn’t just the brace. He had a reusable bag hanging empty at his side like a prop he didn’t know how to use. Without Deborah’s orbit, he looked like a man learning gravity alone.

We stared for the span of a heartbeat and then the rest of the world flowed around us—the steady beep of the scanner on register three, a toddler melting down over marshmallows, a teenager stocking yogurt with the solemnity of a ceremony.

“Hi,” I said at last.

He swallowed. “Mom—Deborah—has a nurse coming twice a week. The rest is… on me.”

I nodded, and because honesty is a habit I’d rather not break, said, “That sounds hard.”

He blinked. “It is.” The admission seemed to surprise him. “I never understood. I thought… it just got done.” He glanced at my basket. “How are you?”

“Good,” I said. Not to needle him. To tell the truth. “Working. Seeing Nancy. Sleeping.”

We stood in a small island of awkward while a woman reached past us for a jar of salsa and gave Kevin the exactly-right kind of bored look that says I do not know your drama and I will not be enrolling.

“I’m sorry,” he said suddenly, the words arriving like a cough he’d tried not to have. “Not for… just the accident. For… the way things were.” He looked like a man trying to reconstruct a building with blueprints he’d never bothered to learn. “I didn’t think I needed to say it. I thought… things would keep themselves.”

“They don’t,” I said. “They never did.”

He nodded. “You won,” he said, but it wasn’t bitter. It was almost awe.

“It wasn’t that kind of game,” I said gently. “But yes. I stopped losing.”

We both smiled, small and tired and not unfriendly. He shifted from foot to foot. “Do you—could you—” He stopped, started over. “Never mind.”

“No,” I said. “Say it.”

“Could you come by once,” he blurted, “to show me how to set up her meds? They gave me a chart but I… I messed up Tuesday and she—” He stopped again, not because he was lying, but because he was ashamed by how true the confession felt.

I took a slow breath. I pictured the old me leaping, the middle me running, the new me with a door that opens the right way. “No,” I said. “I can’t come.” His face fell. I offered the only thing I owned that doesn’t cost me. “But I can text you a video.”

He nodded, eyes shining, and surprised me by not arguing. “Thank you.” He glanced at my basket again, the strawberries, the little indulgence of cake mix I no longer needed permission to buy. “You look—” He caught himself. “Take care, Meline.”

“You too,” I said.

I sent the video that night—simple things I’d learned in the heavy years, shot on my phone at my kitchen table with a wand of pens pretending to be medicine bottles. AM, PM, keep the mistakes low-stakes. I signed off with Good luck and put the phone down. Nancy texted an hour later: He called me. Said thanks. Didn’t even yell. Who is this man.

Someone learning, I typed.

In June, on a dry, blue Saturday, the past asked me for a different kind of appointment. The county clerk’s office where you file divorces is the same place you go to finalize them. I stood in line behind a woman contesting a parking ticket and a guy trying to register a dog and thought how strange it is that endings and beginnings share a counter.

When my number flashed, the clerk stamped the final paper with an efficiency that would be funny if it weren’t so humane. “You’re all set,” she said. “Copy’s for you.”

“No certificate?” I asked, then realized the stupid of the question. Weddings sell certificates and frames. Divorces sell space.

“For you?” she said, smiling like she knew the joke and wasn’t in the habit of laughing at anyone. “You can make your own.”

I walked outside with the document in an envelope. The last time I had carried paper this precious out of a building, it was a marriage license and I was a person who would have signed away anything to be asked to dance. Now I was a woman who would sign only for herself.

On the courthouse steps, I passed a young couple, hands clasped like a contract. She had a bouquet; he had a look that made me wish them the best map. On impulse, I handed her the sunflowers I’d bought from a cart down the block.

“For luck,” I said. She took them, smiling the way people smile when strangers bless them just right. “Thank you,” she said.

I watched them go, and I didn’t think: hope springs eternal, because sometimes it doesn’t. I thought: may you choose different faster and kinder than I did if you must choose it at all.

July made good on its promise to be brutal. Heat hung on the afternoon like a curtain. On the fourth, instead of driving to Deborah’s and swallowing myself whole in the name of tradition, I stayed home. Nancy came over with sparklers. Jo brought a pie and a bottle of something cold. We ate on the floor because cushions are better than chairs when your people are the kind who lean. Fireworks popped over the lake like punctuation for the story we were writing in our own words.

Around nine, my phone buzzed with a text from an unknown number and a photo—Deborah sitting up in that lift chair, mug shot stern but a little less sharp, Kevin in a kitchen that looked adapted for the life they now lived, his grin anxious but real. The caption read: We managed the potato salad. Felt right. A dot. Happy Fourth.

I surprised myself by smiling. Happy Fourth, I replied, and put the phone face down, not as avoidance, but as a choice. I lit a sparkler and traced my name in the air like a child who believes in magic. The letters hung for a heartbeat and disappeared, the way light does on purpose. Jo whooped. Nancy filmed and yelled “Mom’s a witch!” and we all laughed until the neighbor’s dog joined in.

In August, a letter arrived, official seal and all. Final settlement disbursement completed. I sat with it on the couch and felt the small tremor that comes when relief finally lands and realizes it has room to spread out. I filed the paper, then called the porch swing store. The one Nancy had threatened to buy me.

“White,” I said to the bored teen on the phone. “No. Blue.” He told me to expect it in two weeks. It arrived in one. Nancy and I hung it on the little balcony off my living room with cursing and a level. When we were done, we sat on it like claim jumpers on a hill and let it carry us an inch and then another. “Swing tax,” she said, and handed me an ice cream bar.

September invited me to forgive myself. It came in the form of a voicemail from a number I knew by ache rather than digits. Deborah’s voice, thinned by time: “Meline. The nurse says I should say thank you. For the list. For the video. I don’t know…” She cleared her throat. “I don’t know how to say this without sounding like someone else, but I’m trying. We’ve… we’ve managed. That’s all.” A pause. “I wanted to hurt you that day in the shed. I wanted to win. I don’t win much now.” Another pause, and then a different kind of breath. “Live well.”

No demand. No “come.” No “fix.” Just two words that had never before come out of her toward me without a string attached.

I walked out to the swing and let it take my weight. It didn’t creak. It carried.

Forgiveness isn’t a balloon you pop or a trophy you win. It’s a valve. You can open it a notch and let enough through to keep the machine from burning up, then close it again for repairs. I didn’t forgive them to welcome them back into rooms I had locked for good reasons. I forgave so I could stop standing guard inside those rooms all day.

I texted two words back: You too.

The fall brought football in living rooms I wasn’t invited to and casseroles to neighbors who looked at me sometimes like I’d grown a secret and they wanted to borrow it. The secret was boring: sleep. food. people who speak to you like a person. That’s it. No one wants to hear that because it doesn’t trend. It just works.

On a Saturday that smelled like cinnamon and sidewalk chalk, Nancy and I wandered a yard sale. On a card table between a chipped vase and a stack of board games was a ceramic cat cookie jar, the exact shade of ridiculous our old kitchen used to refuse. “Buy it,” Nancy said. “You need a guardian.”

I bought it for two dollars and named it Custody.

One evening, I found the notebook where I’d written KEEP on the inside cover and added a page:

The way the lake looks when it pretends to be glass.

A child’s belief in sparklers.

Sunflowers, again, always.

A porch swing that promises nothing and delivers exactly that.

The sentence I am not disposable, now written in a hand that doesn’t shake.

Winter will come again, I know. It always does, and with it some version of the past trying to wear the present like a borrowed coat. But I also know what I didn’t before: I have a door that opens the right way. I can step out. I can step in. I can lock it. I can leave it open for the ones who knock properly.

The last time I saw Kevin and Deborah together was by accident. January. A clinic waiting room. I was there for a flu shot. They were there for physical therapy. He wheeled her in, gentle with the footrests, careful around the thresholds. He looked up and met my eyes. Deborah didn’t—whether by choice or because the angle was wrong, I don’t know.

He nodded. Not a plea; not a performance. Respect, or the beginnings of it. I nodded back. The nurse called my name. I went. I didn’t look back. I didn’t need to.

That night, I sat on the swing wrapped in a blanket, a mug of tea steaming my face, and the cold felt like information instead of punishment. I whispered into the kind dark the words that carried me out of a shed and into a life:

“This house is mine. My life is mine. And I am no longer theirs to control.”

Inside, the small apartment hummed as if pleased. My phone buzzed once—Nancy: Did you hang the twinkle lights yet? I sent a photo of the swing under a halo of soft bulbs. She sent back fourteen hearts. Jo sent a gif of a Disney witch cackling with champagne.

I laughed into the quiet and let it love me back.

Clear Ending

They locked me in a hot storage shed and called it family. A hospital called and told me they were dead, and for one complicated second, I thought freedom was something that arrives by accident. It isn’t. It’s everyday work. It’s picking up the hammer. It’s walking into the hospital and saying No for the first time like a prayer. It’s signing papers without a trembling hand. It’s choosing small mercies you can afford and refusing the big ones you cannot.

I didn’t win. I simply stopped losing.

The hospital’s first voice mail was wrong. What I saw there wasn’t death. It was a mirror. I put down the parts of me that were built for their convenience and picked up the ones that were mine. I left a list with the nurses and a video for the man who never thought he’d need one. I stepped into a life with a swing and a notebook and a daughter who says I’m shining.

This is the last page. Not because stories end—stories keep walking—but because I don’t need to prove anything else.

They wanted me to regret drawing a line.

The only regret in this story will forever be theirs.

I turned out the porch light and went inside.

THE END

News

I Got A CALL From My Neighbor About A Moving Truck At My HOUSE While I Was At Work—When I Arrived…CH2

The Call My name is Meline, but everyone who’s known me since I was five calls me Maddie. The dual…

My daughter pushed me into the closet. CH2

The Knock of Heels The call came at 1:17 p.m., just as the office coffee machine shuddered and died with…

I Forgot To Tell My Wife About The Hidden Cameras I Installed, So I Decided To Just Watch…’ CH2

The Ceiling, the Stain, and the Lenses I Never Meant to Use At two in the morning the ceiling was…

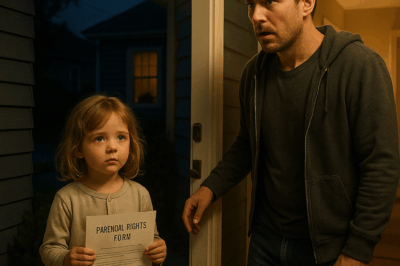

My 4 year old Niece showed up at midnight with a parental rights form CH2

The Knock at 12:03 When the knock came, I thought it was a branch on the siding. The mountain does…

My Husband Kicked Me in Front of His Friends—And My Revenge Was Not What They Expected CH2

By the time the elevator eased open on the executive floor, the building had learned to be quiet around me….

The comedy star who impersonated a White House official has the Internet abuzz with the rumors she spreads along with it CH2

In the high-stakes world of politics, where every statement is analyzed and every public appearance is scrutinized, moments of levity…

End of content

No more pages to load