Part One

I wish I could tell you the first crack in us sounded like thunder. It didn’t. It sounded like my ankle hitting the edge of the third stair and the slippery thunk of my body skidding the rest of the way down. The world did that bright white thing pain does, and then it narrowed to the hospital ceiling tiles counting off seconds I couldn’t swallow.

Jason drove; his jaw was set, hands at ten and two like a model from a driver’s ed video. He kept glancing at his phone where the screen lit up and dimmed with the patience of a dog. “It’s a client,” he said without looking at me. “Needs something signed. I may have to step out.”

“Work’s work,” I said, because that’s what you say when you are the kind of woman who has spent six years smoothing instead of asking. “It’s fine.”

He exhaled through his nose. “You’re a trooper, Abby.”

We were wheeled into triage. The nurse snapped a bracelet around my wrist; the X-ray tech showed up like a grim magician and slid my leg under a machine that hummed “fracture” the way a storm hums “take cover.” A doctor with sleepy kindness told me I’d need pins and an evening time slot in an operating room. He asked who would be staying.

“Her boyfriend will be back,” Jason said, like someone ordering a sandwich he had every intention of eating later. His phone lit up again. He kissed my forehead, brief, camera-ready. “Client’s downstairs. Back in ten.”

Ten minutes turned into the color of afternoon that loses its edges. A kind nurse named Aurora tucked a warm blanket over me the way my mother did when I was nine and convinced fevers were tsunamis. I texted Jason an update—Surgery at 8. They’re admitting me. The typing dots appeared, then disappeared, then the message Got it pinged in, neutral as a receipt.

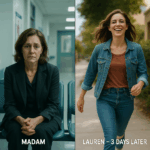

It was an hour later, after pre-op, after a paper cup of something chalky and a bolded consent form, when I saw it: Lauren Mitchell’s story on social media—Jason kneeling on a patch of sidewalk, tending to her knee like an advertisement for gentle masculinity. The caption: “Who’s the little clumsy thing that managed to scrape her knee just from walking?” A laugh emoji. Another. A selfie angle that knew Jason’s flattering side better than I did.

The anesthesiologist asked me to count backward from one hundred. At ninety-eight I was looking at the way Jason’s hand cupped the gauze on Lauren’s skin. By ninety-six the laugh was echoing. By ninety-five the room went quiet.

I woke in slices. Pain is a metronome when your body’s had enough of being brave. There was a buzzer somewhere; there were footsteps; there were voices that belonged to people trained to make voices sound like balm. There was not, for quite a while, Jason. The nurse with the comet name helped me sit; she helped me stand when standing had become an act of historic audacity. “We’ll get you signed out in a day or two,” she said. “We’ll get you set.”

I messaged Jason. Done. Hurts. Where are you? The phone stayed dark long enough to grow a second skin.

When you love a man who has a childhood sweetheart in the same city, you learn to live on a diet of explanations. First, they’re complete meals. Later, they’re candy. Eventually, they’re air. Mutual friends had perfected their faces by now—soft sympathy, delicate noncommittal. I’d perfected mine too—cool, unbothered, the face that leaves likes under the photos that gut you because rage takes energy you need to stand on one leg.

The second day, Aurora limped down to billing with me because their elevator was broken and irony has a sense of humor about bones. “We’ll go slow,” she said. “Strong woman is fine. Smart woman asks for an arm.”

In the fluorescent cavern of a waiting hall, I looked down and saw another post ping my phone like a flare. Lauren again. Jason again. The caption this time: “He scolded me while bandaging—so funny. How clumsy can I be?” My throat closed like a door and then, startlingly, didn’t. I double-tapped the little heart. I typed the comment with fingers that didn’t shake: Silly girls are meant for great heroes. You two should be together.

Aurora glanced over my shoulder, then at me. She didn’t ask. She handed me a pen instead, the thick child-safe kind you give people who’ve lost too much to grip. “Sign here, honey,” she said. “And here.”

The day I was discharged, Jason finally texted. I’ll come get you. It read like a wet paper towel trying to mop a flood.

I could see the script he wanted—the contrition light, the apology shaped like an “us against the world” meme. I had starred in that play before. The third act was always his timing. No need, I typed. I’ve completed the discharge.

Then I’ll come pick you up.

No need. I’ll take a cab.

I’m already on the way. Pause. Wait for me. Half an hour.

Half an hour became a dark window reflecting my own face back, then the stairwell at home with a driver kind enough to help a stranger up five flights, then the kind of emptiness a phone makes when it could ring and does not. I stayed on a video call with my best friend the whole way up because the lights were out in the stairwell and the only camera I could count on was the one between us.

Inside, I tipped the driver more than he’d expect and sat on the floor because the sofa felt like ceremony. A ping: Lauren again. “Jason had barely left when I fell again. How clumsy can I be? He was scolding me while bandaging—so funny.” Another like. Another comment. You two should be together.

My phone lit with a call from Rachel Foster, my boss, the kind of woman who doesn’t ask if you can do hard things because she hired you with the assumption you could. “Abigail,” she said, her voice a piano note in the middle register, “Hong Kong expansion. They want you. Title: Director. Package: one-point-three.”

I had turned it down before. For love. For habit. For a man who used “client” like a synonym for “Lauren.” Rachel continued, “I also negotiated a rotation. Two weeks back every five months. You can still—”

“Rachel,” I said, and my voice didn’t tremble. “No need for the rotation. Just tell me when to go.”

There was a pause. Then I could hear her smile widen through the line. “End of the month, darling. Don’t you dare back out. We start handover tomorrow.”

Later, laptop open, inbox humming like a hive, I didn’t hear the door until it clicked and Jason was standing there with the faintly irritated look of a man kept waiting by his own narrative.

“Why didn’t you answer my calls?” he asked.

I glanced at my phone. A spray of missed calls around midnight. I tapped the screen as if to see if it still worked. “I must’ve been asleep,” I said. “Sorry.”

“I went to the hospital to get you,” he said, already halfway to the drop into exasperation. “You weren’t there.”

“Oh,” I said, mild as milk. “Thought you weren’t coming. I took a cab.”

Something like confusion darted behind his eyes. We have roles, after all. Mine had been to demand timelines, accuse, then capitulate on the third day of silence like a runner who hates her own endurance. He sat beside me. “Actually… Lauren fell. You know her bones. Even a minor fall—”

“Fracture,” I said, and he blinked.

“What?”

“Mine,” I said lightly, and nodded at the thick bandage and the crutches by the door. “Pins. Surgery was fine.”

He stared, as if facts are ruder than accusations. “You… should have told me.”

“You were busy,” I said. “It’s in the past now.”

He swallowed and reached for my hand like it was still the lever that opens a trapdoor where we keep my forgiveness. “I know I was wrong,” he said. “I’ll be the one to give in this time. Can we just let this go?”

“No need,” I said, and smiled in a way that made something behind his eyes flinch. “You don’t have to make it a whole thing.”

“This is the first time I—” He stopped. “You’re not angry?”

“Angry about what?” I asked. “You and Lauren grew up together. You always take care of each other.”

He stood and then sat again, a man testing gravity. “If you’re angry,” he said, voice running its hands along the furniture, “just say you’re angry. I’m not incapable of listening. Why—why play these games?”

He’d always hated fights. At work he could locate the flaw in a logic chain in half a sentence, but at home he refused to practice that talent. He’d said, more than once, I’m tired. I don’t have the energy for your baseless accusations. I listen to Lauren because she has a weak constitution. We grew up together. What does that have to do with you? I don’t even like her that way; she never scolds me. Stop comparing yourself. I had kept those words on a shelf labeled Hurt and visited them like museum pieces, walking away no better.

Now, I thought, he still wanted the exhibition. “I’m not angry,” I said again, and meant it in the only way that matters: there was no one left to be angry at. Anger needs attendance. Indifference pays its own bills.

I closed the laptop and stood. Pain shot up my shin like a flare and I folded, graceless, toward the rug. “Abigail,” he said, more panicked than the moment deserved, his hand shooting out to catch my arm.

I pulled away gently. “I forgot the crutches.”

“Why would you need—” He stopped, the memory landing. Her bones aren’t strong; I couldn’t leave her. His face rearranged itself in a way I had not seen before: guilt threaded with the first stitch of shame.

“I’ll carry you to bed,” he said, as if a heroic lift could retrofit the night.

“Just pass me the crutches,” I said. “I can walk myself.”

He didn’t move. “Wouldn’t it be easier—”

“It’s late,” I said. “I’m going to sleep.”

He stood there, fingers tightening and loosening at his sides, trying to understand a woman he had taught not to say no suddenly saying nothing but. “Abby,” he said, softer, “if you’re not angry… why won’t you let me take care of you?”

I thought about waking up in recovery with my phone lighting and dimming like a distant lighthouse. I thought about the nurse’s arm around my waist as we took the stairs one slow step at a time. I thought about where you place your weight when you don’t want to fall again.

“When I came out of surgery,” I said, “I was alone, too.”

His eyes changed shape. “You had surgery,” he repeated, like the concept needed his approval to be true.

“It’s past,” I said. “Bring me the crutches. Please.”

He didn’t. He stepped closer instead, the plea in him leaking into the room. “Abby.”

I hopped once, twice, and reached the doorframe without his help. I didn’t look back.

From the bedroom, I heard his voice go flat, then sharp. “Fine,” he said. “Do whatever you want. I’ll go take care of Lauren.”

The door hit the latch a little too hard. I turned off the light. I slept.

I met Jason Miller twelve years ago in a student council office that smelled like dry-erase markers and the kind of ambition you can stand because it hasn’t learned to be cruel yet. He was the quiet one with the better ideas, the one who made silence an asset. I loved him like a project I could ace and then, later, like a home I was afraid to redecorate in case he stopped recognizing the route back.

After graduation we split our calendar into his and his. I pushed promotions. He pushed clients. I adjusted. Classmates changed titles on LinkedIn and then changed cities. My salary plateaued at a number I used to think was altitude. It’s funny, the way love teaches you to become the person you’d argue against in daylight.

By the time Rachel Foster pressed Hong Kong into my palm like a passport, I had forgotten what “yes” felt like when it belonged to me.

The week after the discharge, I lived at the office. It was easier on the leg and my pride. I studied case files and certification prep until acronyms blurred into lullabies. Jason didn’t message. That was normal. He prefers words where my body is. He esteems presence, he says, like a monk. I used to arrange my weeks around that preference like a woman rearranging furniture around a man’s favorite chair.

This time, he messaged first.

Let’s have dinner. A private dining room photo. The restaurant—of course—the one he loves.

I had the same restaurant open in the delivery app, a muscle memory disguised as hunger. Okay, I typed. Then in the quiet moment after the blue bubble sent, I felt myself set a small rule: there is no such thing as “our place” if I’m the only one who saves the table.

I didn’t need the crutches by seven, but I still favored the left. I pushed open the door to the private room and heard laughter. That should have been the headline. The subhead: Lauren Mitchell was sitting beside him, a glossed grin like a sitcom girlfriend. She had left my side of the table empty and called it respect.

“You’re here,” Jason said. He watched my face like it was a cross-examination. “We were just talking about the past.”

“Oh, carry on,” I said, and took my seat.

He waited for the storm that didn’t come. He blinked, then gestured at the server, the menu. Lauren leaned into his shoulder, pointed at dishes like we were at a theme park. “Jason, this, and this—”

“Little foodie,” he teased, ladling familiar affection into the room, “you just want it, don’t you?”

He marked her choices and handed the menu to the server. The server, trained to keep rooms from catching fire, looked at me. Jason hesitated and held out the menu like a peace treaty. “And you?”

I scanned the list I could recite. “Lauren has good taste,” I said, and handed the menu back.

For a second he didn’t move, as if he’d misheard the language. The food came. I reached for the braised pork; he beat me to it and placed it in Lauren’s bowl, then glanced at me as if to catalog flinches. He used to put that same dish in my bowl without asking. I put a piece in my own and kept typing a client message with my free hand. The trick to starving old rituals is to feed new ones.

“Sit across from me,” he said abruptly. Lauren blinked, caught off guard. He nudged her shoulder. “Go on.” Then to me, “Abby. Here.”

“No need,” I said. “It’s fine.”

“We haven’t talked in a week,” he said, the fray in his voice showing. “Don’t you have anything to say?”

I had to laugh at that—to realize, in an instant, that the person who once begged for explanations was not me tonight. The phone rang in my hand; it was the client who paid more than my sorrow. I answered, promised five minutes, and stood.

“There’s a big deal,” I said. “We’ll put our thing on hold. You two continue.”

He stood too. “I’ll take you.”

“No need,” I repeated, and then, because old habits are magnets, I let him.

Lauren trailed behind us like a ribbon. At the car, she reached for the passenger door like a reflex. Once upon a time, that had been my seat and the pendant with my photo hung there like a gentle brag. Once upon a time, I had reminded her the back was more spacious, and Jason had snapped, She’s not in good health. Are you really arguing over a seat? How long have I known her? How long have I known you? You’ve changed. The next day the pendant was gone.

Now, Jason’s hand closed over the passenger door. “Back,” he said to Lauren, not unkindly, not kindly. “Today.”

I opened the rear door without theater. “It’s fine,” I said. “Let’s go.” But the line had been drawn and he’d drawn it, and I watched that sink into the space behind his eyes like a nail.

He kept glancing into the rearview, searching for the quiver that would let him shout down guilt. He didn’t find it.

He drove me to the office and reached for my elbow automatically. A colleague got there first. “No need,” I said. “Go back. Otherwise, your passenger won’t stop sulking.”

He gripped the steering wheel like a man who finally noticed it doesn’t move the car when the engine’s off.

I didn’t think about him for three days. That sentence is both a confession and a door. My leg throbbed; the certification books made their own secret city on my desk; Rachel started every morning with Hong Kong like a blessing.

When Jason texted, it was a sentence I’d been waiting to hear for six years. My parents want to meet you tonight. The last time they were in town, he’d hidden them like a surprise he couldn’t gift. He’d brought me bags and kept me home.

Sure, I wrote.

He drove me to his apartment. Laughter met us at the door—his uncle and aunt and the third voice that isn’t family but always sits like it is.

“Good child,” his aunt said to Lauren, “if Jason ever teases you again, tell us. We’ll fight him for you.”

I set the gifts I’d brought on the table and handed one to the woman who had never asked me to call her Aunt. “Hello,” I said. “Uncle. Aunt. And Jason’s friend.”

Jason moved quickly, as if something had been knocked slightly off the shelf. “She’s my girlfriend,” he said.

I smiled. “Actually, Uncle and Aunt—Jason and I aren’t really dating.”

They blinked, the way people blink when they realize they’ve been given two scripts. Jason recovered like a man who can sell a timeline. “What she means is we’re planning to get married soon.”

It was his father’s birthday, and hope had already been set on the table besides the plates. I nodded because I am the kind of woman who refuses to ruin cake with truth when there’s a better time to bake it in. His aunt snuck me a red envelope when she thought Jason wasn’t looking. His uncle said, “Finally.”

I tucked the envelope under the shoe cabinet when we left, next to the velvet engagement box I hadn’t seen yet but could already feel like a meteor.

On the drive back to the office, Jason gripped and released the gearshift. “I know I’ve let you down,” he said. “I’m sorry.”

“It’s okay,” I said.

“What’s between Lauren and me—”

“You don’t need to explain childhoods,” I said. “You need to learn adulthood. It’s not mediation if you always pick the same person.”

He went very quiet at that red light and lit a cigarette he didn’t smoke. I took it from him and lit it for him. “Occasionally is fine,” I said. “Don’t make it a habit.”

He looked at me like I’d put a mirror on the dashboard.

I left him at the curb outside my building. He texted that night: When are you coming home? I said I’d be late. He said he’d wait. I said my colleagues would drive me. A long pause. Then: Was that a male colleague? I said no and ended the call.

When I got home, the apartment smelled like smoke and something else—panic, maybe, or a hunger he’d finally felt. He stubbed the cigarette out like a teenager caught by his mother and stepped into the light. His eyes were red.

He held me so tightly I remembered the feel of the old pendant hitting my collarbone when he’d open the passenger door. “I’m sorry,” he said into my hair. “Were you this anxious waiting for me back then, too?”

Once, I would’ve cried. That night, I remembered the cold food on the dining table the year he’d skipped my birthday because a colleague had scored concert tickets and Lauren “loved that singer.” I remembered slapping him once, the only time, and the cake he put out three days later without an apology because time heals all excellent intentions.

“You called me,” I said. “Was there something you needed?”

He pulled back, unsteady. “It’s your birthday, right?”

I had actually forgotten. “Thank you,” I said. “It’s late. Let’s skip it.”

“No.” His hand trembled and his voice with it. “It’s your day.”

I lit the candles, because elegance has nothing to do with audience. “This cake,” I said, “is also something else. It’s the conversation we’ve needed to have.”

He looked at the door like a man remembering a fire drill. He grabbed his coat. “Work,” he said. “I—there’s work.”

Under the shoe cabinet where I’d tucked his parents’ red envelope, I found the ring later. Classic setting. Unassuming price. Trembling timing. I put it back and texted him two words: Let’s break. And then I blocked him, because endings, like surgeries, require consent.

Three days later—that phrase people use when they want time to have done more than it can—Lauren texted: What did you say to him? He can’t live without you. I wrote back nothing. Then I found out what “can’t live without” looks like in the light: a lab accident, a white burn across the retinas, a man insisting a stranger’s voice was mine while refusing treatment until he heard the one sound he wanted.

But that—his bandaged eyes, the way he reached for air when he said my name, the final goodbye I had rehearsed under the hum of a refrigerator and got exactly right when it mattered—that belongs to another part.

Tonight, I folded the last blouse into a suitcase waiting to fly twelve time zones ahead of the life I’d left, and I slept without waking. In the morning, the nurse named after a star sent me a message. How’s the leg? Strong, I wrote back. Stronger.

And for the first time in a long while, the word meant me.

Part Two

Three days later, the call came from a number I didn’t recognize and a voice I did.

“Abigail,” Lauren said without preamble, the syllables of my name clipped like she could make me smaller if she spoke faster, “what did you say to him? He won’t— he can’t— this is your fault.”

“My fault,” I repeated, tasting the words, finding them bland. “What happened?”

“He’s… he hasn’t slept. He hasn’t eaten. He’s been… trying to forget you. He went back down to the workshop. There was an… incident.” She swallowed. “You need to come. Please.”

I could have asked which workshop, what incident, how bad. But I already knew more than I wanted to. Jason had always chased control like oxygen. When something escaped his grasp, he’d tighten every other fist until his knuckles went white. I ended the call, pulled on a jacket, and texted Rachel: I’ll be in late.

Ten a.m. is fine, she answered. Twelve is fine. The whole day is fine. Just come back, okay?

At the hospital—the same one with the honeycomb ceiling tiles and Aurora’s comet smile—the smell of antiseptic met me like a memory. The hallways were the same tired gray; the vending machines held the same stubbornly cheerful trail mix. Outside a room with his name printed on a paper placard, a nurse lifted a finger: Quiet.

Inside, Jason lay under a sheet. Gauze wrapped his head in precise bands, the kind a careful hand makes when it wants pain to feel like order. His eyes were closed, the lashes too still. On the bedside table, his phone was playing my voice—old voice messages from the months when I used to fill the silence between us like a good student padding an essay to meet a page count.

The doctor stood at the foot of the bed with a chart and the practiced gentleness of a man who’d learned to deliver percentages as if they were lullabies. “Flash explosion,” he told me. “Lab light. Damage to the retina. We’re hopeful the blindness is temporary, but not if he refuses treatment.”

“Refuses?” I said. I looked at the phone, at myself being useful to a device.

“He keeps insisting,” the doctor continued, “on hearing from ‘Abigail’ before he consents to the steroid course. Your friend”—his glance drifted toward Lauren—“attempted to help. He isn’t fooled.”

Lauren’s face was blotched red, a rare betrayal of her polish. “I tried to… to feed him. To—he thought I was you.”

“He thinks in outlines,” I said. “He fills in faces with habit.”

The doctor nodded, grateful for a sentence that meant he didn’t have to explain a man who made sense only to the women who loved him. “If you could…,” he said. “It would help.”

I crossed the room. Up close, he looked younger, like the first week we met and I decided I could project manage my desire into a job. He had always had the kind of beauty you mistake for stability; now, wrapped in sterile white, he looked like a promise that still meant well.

“Jason,” I said, and my name in his mouth was immediate.

“Abigail?” He sat up too fast, hands reaching, this new dark a cliff he hadn’t mapped. “You’re here.”

“I’m here,” I said. “Just for a minute.”

His fingers found mine. He clutched them like a man pulled, finally, from underwater. “I—there’s… I was stupid. I’ve been… I can’t—”

“You need to eat,” I said. I lifted the bowl of congee, still warm from a cafeteria that does one thing right. I fed him a spoonful. He swallowed like obedience.

From the door, a nurse said, “No crying,” half-chiding, half-pleading. Tears change pressure in eyes that need rest. But tears don’t take instruction. One slipped from under his bandages anyway, slow, pure. He gritted his teeth like a man performing a trick for an audience he couldn’t see.

“You don’t have to do this,” Lauren said behind me, a tremor in her voice that, weeks ago, would have cracked my own. “He’ll be leaving soon.”

Jason’s hand tightened. “It’s okay,” he said. “You have your trip. You’ll come back after, right? You always come back.”

“I won’t be coming back,” I said.

His face moved as if toward light. He didn’t find any. Panic knife-edged his voice. “Jason Miller is moving to Hong Kong to advance my career,” I continued gently, because truth is a gift you wrap in evenness when you can. He heard the thousand unspoken words anyhow.

“I—” His mouth opened and closed around all the things he had saved for a birthday he’d missed. “It’s okay,” he said finally, the line he uses when he wants to skip to the part where I fix what deserves breaking. “I’ll wait. However long. Or I’ll— I’ll quit. I can… I can come find you.”

“No use,” I said, and for once I wasn’t making a point; I was naming a fact like weather. “I don’t love you anymore.”

If there had been light, I think he would have looked for a mirror to confirm he was still in his skin. In the dark, he searched the air instead. His hands trembled around mine, then steadied through sheer force of self-control and fear. “Don’t cry,” I told him.

He swallowed the storm. Breathing ragged, he tried again. “But when my parents came—you promised.”

“I was going to tell you then,” I said. “I tucked the red envelopes under the shoe cabinet. The ring too. The key is on top of the cabinet. Make sure you take it when you leave.”

The muscle in his jaw flexed hard enough to bruise. There are men who will never cry for themselves but will leak for the future they were absolutely sure would forgive them. He forced the tears back because the nurse had asked and because I had. Then he failed because the body keeps its own calendar.

“Jason,” I said, and I said it the way you say it when you are both the road and the sign. “This is the last time I’m coming. The mistakes we made when we were young—we leave them here. We part clean.”

His grip slipped; mine did, too. I took my hands back, not brutally, just certainly. I walked to the door.

Somewhere behind me, something broke open. He tore at the tape. The IV jerked. Blood spotted the sheet in a pattern I will probably dream in crimson for a while. He stood, stumbled, lurched toward the sound of me. “Abigail, don’t go. I was wrong. Please. Come back.”

Nurses appeared like well-trained angels, gentle and immovable. “Sir,” one said, “you’ll injure yourself.”

“I don’t want her,” he shouted, and I turned without wanting to. He meant Lauren, who had stepped forward, then backward, then forward again, caught between roles like a woman at the edge of a stage with the wrong script. “I want you,” Jason said. “I want you, Abigail.”

Bandages half-torn, eyes raw, he was terrible and beautiful and, finally, honest.

“Jason,” Lauren cried, and reached. He pushed her away without seeing her. She fell, her hand catching the bed frame, her body folding around a leg that may or may not have been weaker than she said. For a long minute once, I would have fallen too. Now, I watched the nurses help her up, watched the way she held on to the pain like an identity card, watched the way she looked at me like I could bless her into better.

“Don’t provoke the patient,” a nurse said gently, steering me into the hall. “Please.”

In the corridor, the air was bright like a fresh page. Rachel called. “Tomorrow’s the day,” she said. “Did you pack like I told you?”

“All set,” I said, and for the first time in months the word wasn’t bravado. It fit.

Home looked like a checklist. I cut labels for each moving box. I set out the trash. I wrote Aurora a thank-you note and slid it under the nurses’ station door with a gift card that buys three coffees and tells someone they matter. I placed Jason’s unopened ring box on the shoe cabinet above the envelopes his aunt had pressed into my palm with all the hope of a woman who had loved some version of me since before she met me. I put the key next to them and thought, briefly, about rings and cabinets and keys and all the ways we store what we can’t carry into the rooms we don’t need anymore.

At midnight, the apartment hummed like a ship that had not noticed its passengers were changing. I stood by the balcony door, looked out at the city that had made me and unmade me and offered me a ladder in the same week. On the floor, my suitcase gaped. I placed the last blouse in it, smoothed the fabric, and zipped the mouth closed.

The phone buzzed. Not Jason. Rachel again: Airport at eight. Don’t bring too much. Bring yourself.

I sent back a heart.

Morning came like light over water. I hailed a car because I could. The driver took one look at the cast peeking from my pants leg and insisted on taking my bag like a gallant from a novel I’d stopped reading years ago. At the airport, the tone of the announcements made everything feel like a reasonable choice.

On the jetway, my phone vibrated. A message got through around the block I’d put up: Abigail— nothing else, a line waiting to be completed. I put the phone in airplane mode, stepped into a different sky, and slept from climb to descent without dreaming.

Hong Kong smelled like rain and ambition. Rachel met me at the gate with sunglasses on top of her hair and a grin that said she had been waiting for this version of me since the day she hired the other one. The office was glass and views and a conference room named after a city we were replacing in a twelve-month plan. My team was a handful of sharp people who didn’t blink when I said no to bad strategy and yes to scary timelines.

At night, the harbor lit up like a constellation that had forgotten it was supposed to be far away. I learned my new neighborhood in circles: corner grocer, noodle shop with soup that tasted like relief, tram line that rocked me into the present.

Rachel kept her one promise I didn’t ask for: Two weeks back every five months. I used the first one to take my parents to dinner and tell them their daughter had grown a spine and a passport. My mother cried and then pretended she hadn’t. My father ordered cake and told a toast that made my cheeks hurt for an hour.

On the second trip back, I ran into Aurora at the grocery store, and we spoke like people who owe each other very little and owe each other almost everything. “How’s the leg?” she asked.

“Strong,” I said.

“Stronger,” she corrected, and we both smiled.

On the third trip, I passed by my old building and saw a new pendant hanging from the rearview mirror of a car I once claimed. A woman climbed out of the passenger seat—tall, tired, nothing like me and exactly like me. Jason opened her door. His eyes had healed to a clean brown. He looked at her the way a man looks when he knows a passenger seat is a privilege. I kept walking because not every story needs a second act.

Lauren’s name reached me sometimes, muffled by distance and time. She started a podcast, someone said. She moved to a different city with more light. She posted less often about scraped knees. She posted once about therapy. I pressed the heart out of a habit I didn’t hate anymore.

And there were nights in Hong Kong when the ferry cut the harbor and the air tasted like metal and future, and a man I didn’t know yet held a door and didn’t expect anything for it, and I realized I had finally stopped auditioning for a part in a play I hadn’t written.

The last time I saw Jason was an accident in the truest sense: a crosswalk, a green light, a pause. He was on the other side in a navy coat, looking like all the versions of himself that had been good to me and bad for me. He didn’t see me. I did not call his name. The light changed. We walked.

At the airport that afternoon, I texted Rachel: Boarding.

Proud of you, she wrote back.

The plane lifted. Clouds made a temporary country I could claim for fourteen hours. I closed my eyes and the ceiling tiles above the old OR dissolved into the belly of a 777 where I was just a person in a seat getting somewhere under her own power.

Jason might marry the next woman in his passenger seat. He might not. Lauren might learn there are better captions than who’s the clumsy girl. She might not. None of it is my project anymore. My project is this: a life arranged around the kind of love that doesn’t require me to twist myself into credentials, a job that gives me back the part of my brain I leased out to male preference, a body that knows the exact weight of its own yes.

When the plane landed, my phone lit up with a message from Aurora: We miss you.

I miss me too, I typed back, then laughed, then changed it to I miss you too and added a photo of the harbor at night because some truths keep better in pictures.

On my first free Sunday in Hong Kong, I walked to the peak just to see how high I could get before the city made me dizzy. At the top, the wind leaned against me like an old friend who has stopped asking if I’m sure and started asking what I want.

I told it.

And it didn’t laugh.

Part Three

Three days after I saw Jason in the crosswalk and didn’t say his name, a message came through from an old number saved as Auntie.

Auntie: Child, are you in town? Your Uncle has been asking whether we can finally treat you to a proper meal.

Once, a text from his family would have felt like a summons to a courtroom where I was both witness and defendant. Now it felt like a calendar invite I could accept or decline without apologizing. I checked my rotation. I had Hong Kong for eight more weeks, then two back in Charlotte.

Me: I’ll be back next month. One lunch. Your pick.

There was a flurry of heart emojis that made me smile in spite of history. I put the phone down and walked out to the tram. The city moved under me like a machine I hadn’t built but finally knew how to ride.

At the office, Jules slid into my doorway with two coffees and a case summary. “You look like a person who chose sleep last night,” she said, half-pleased, half-mocking.

“I did,” I said, and meant the kind that isn’t a collapse.

“We’ve got a client who needs the quiet version,” she added. “Pediatrician husband, PTA friend. I already color-coded the timeline.”

“I hired you for your ethics,” I told her. “But your tabs make me emotional.”

We worked the way people do when the engine finally fits the chassis—smooth, efficient, no parts rattling. At lunch, Rachel stuck her head in to remind me to eat and not to become a myth. “Busy women disappear behind their competence,” she said. “Be visible to yourself.”

I took my noodles outside and watched the harbor throw coins of light at the sky. Three days later had started to feel less like a plot point and more like a practice—waiting long enough to confirm that urges weren’t needs and wounds weren’t instructions.

When I landed in Charlotte for that two-week rotation, summer had slipped into the air like a quiet language. The city looked almost like the one I loved before I learned it could love me back. I met Auntie and Uncle at a dim sum place they favored because the carts pretended time was a circle and you could have another chance at the dish you missed.

Auntie kissed my cheek as if we hadn’t all lived through the theater of birthday cakes and postponed apologies. Uncle stood a little straighter because men of his generation believe posture can fix history.

“You look thin,” Auntie said, which is Southern-Parent for You look good but are you eating?

“I’m eating,” I said. “And sleeping. And working. And not arguing with anyone who wants to win on a technicality.”

They laughed more than they corrected. It was a relief to discover I didn’t have to perform contrition for a breakup that did not owe them a villain.

Halfway through the turnip cakes and Auntie’s insistence that I take home extra sesame balls “for the plane,” Uncle cleared his throat. “We owe you an apology,” he said, eyes on the tablecloth. “We should not have let… misunderstandings cook in our kitchen.”

“A lot of things got overcooked,” I said. “It happens.”

Auntie reached into her bag and pulled out the red envelopes I had tucked under the shoe cabinet months earlier. “We found these,” she said. “By the door. You were always tidy.”

I put my palm up. “They were gifts,” I said. “Gifts are received. Keep them.”

“Let us do one thing right,” Uncle insisted. “Keep Hong Kong beautiful on our dime.”

I let them press the envelopes toward me because refusing would have been performative and I am too old to audition for my own kindness. “Thank you,” I said. “For seeing me as a person separate from a story you wanted.”

Auntie dabbed at her eyes. “You deserved more than a seat assignment in someone else’s car,” she said, and the line landed like an absolution I hadn’t asked for and didn’t need but accepted anyway.

We talked about small things after that—how airplane food is designed by people who think salt is a myth, how Uncle’s blood pressure monitor beeps like a smoke alarm, how Auntie believes Lauren’s podcast is “too loud to be good for the liver.” We did not talk about Jason. Not because he didn’t exist. Because he didn’t need to be the subject again.

When I stood to leave, Auntie grabbed my hand. “If you ever need family,” she said, “we’re here. We are not the same as we were.”

“Neither am I,” I said.

Outside, the heat hit my face like a familiar argument. I walked two blocks before my phone buzzed again.

Unknown: Ms. Scott? This is Lauren. Please don’t block me. I… need a favor.

I stared at the name for a second. The years had taught me to read the difference between a trap and a request. This felt like the second.

Me: What do you need, Lauren?

Lauren: My leg really is weak. Not an excuse. I need a good ortho. Also… if I could get a line from you about work—nothing personal. I’m applying to a community center. They need references about my programs being effective.

There are crossroads you can see only when you’ve walked past your last one. I could have said No and felt righteous for an afternoon. I could have said Yes and felt resentful for a week. Or I could right-size the ask.

Me: I can send you the name of a surgeon and a PT Aurora recommends. For the job, I won’t speak to character. I will confirm that programs you ran met their metrics when I knew you. Nothing more.

There was a long pause that read like a woman deciding whether to take dignity or hold out for absolution.

Lauren: Thank you.

I sent the names. I drafted the sentence for the community center like a scientist writing a method: precise, dry, useful. I did not add adjectives. I did not subtract facts.

Three days later, a short note popped through from her.

Lauren: Got it. Starting part-time. It’s quiet work. Feels good.

I did not reply because not every mercy needs an echo. It was enough to know that a woman who once posted about scraped knees for applause now spent her mornings counting reps next to a silver-haired grandmother on a yellow mat.

Back in Hong Kong, life assembled itself like furniture you didn’t have to turn upside down to fit through the door. My apartment had a view that made thunderstorms look deliberate. My leg no longer telegraphed weather. I ran the peak stairs once a week because it amused me to reclaim the word that had broken me at the beginning: stairs as ascent, not accident.

Jules and I built a pro bono arm for the firm: two afternoons a month where we helped people gather what the world had convinced them was missing—their own evidence, their own language. We taught them to screenshot, to save, to step into rooms with binders that made the table respect them. I kept a box of tissues under the credenza and used it less than I thought and more than I admit.

Rachel still walked past my door at 6:30 with her bag on her shoulder, reminding me that leadership means leaving sometimes. I took the hint. I met friends at a dai pai dong that served clams in black bean sauce so good we forgave the plastic stools. I learned to say thank you and delicious and no plastic bag in Cantonese. I stopped waking up at 3 a.m. trying to remember whether I had left a part of my soul in a stairwell with a broken light.

On my third rotation back to Charlotte, I ran into Aurora at a farmer’s market. She was off-shift, denim jacket, hair down, the comet of her smile now a constellation. “How’s the stair champion?” she asked.

“I can take them two at a time,” I said. “On good days.”

She squeezed my forearm. “Strong,” she said, approving.

I told her I’d used her PT referral for a woman who needed it. She nodded, the way good nurses do when you prove you learned the most important thing from them: kindness is a system, not a mood.

I did not see Jason on that trip. Or the next. Stories don’t always arrange themselves for your convenience. On the fifth rotation, fate tried to hand me a cliché—rain, a café, a face in a window—but I walked to the next block because clichés only work if you choose them.

What I did see, unexpectedly, was a message from Auntie with a photo attached. Jason stood between Uncle and Auntie, a woman on his arm whose posture was its own integrity. The caption: He’s learning to be on time. There was no ask, no demand, no psalm about “meant to be.” Just three people in a picture doing their best.

I sent back a heart and a line: I’m happy for your family. It was true. It was complete.

In Hong Kong, a man on the ferry started nodding to me in the mornings the way people do when they realize they share a route. He never tried to talk over the water. The third week, when rain turned the deck into something between a mirror and a dance floor, he offered a hand as I stepped. “No need,” I started to say, then caught myself. “Thank you,” I said instead, and took it. Some help doesn’t steal your autonomy. Some help makes sure you keep it.

Three days later, he asked if I’d like to try the wonton shop his grandmother swore by. I said yes. Not because I was writing a new story. Because I was hungry.

On a Sunday evening, I stood at the top of the peak trail with air pushing against my face and looked out over a city that had learned to forgive my ambition. My phone buzzed.

Rachel: You free to keynote a women-in-leadership event? Title is yours.

I looked at the city, at the slice of harbor bright as a vein, at the trail that now felt like a habit instead of a dare. I thought about the hospitals and the stairwells and the woman who asked to sit in the front seat as if seats are destinies.

Me: Title: Three Days Later.

Rachel: Hook?

Me: That time is a tool. That truth doesn’t negotiate. That boundaries are love in grown-up clothes. That you can fall down the stairs and still decide who carries you next time.

Rachel: Sold.

I put the phone away and started down. The descent was its own work; it always is. I moved carefully, not fearfully. I passed a family coaxing a toddler over a rock too big for her legs and felt an unexpected tenderness for every version of me that thought rocks were personal.

At the halfway mark, I stopped to catch my breath at a landing with a view of nothing but concrete—a humble little platform, unremarkable and exactly what I needed. The first time I fell, it was on stairs that weren’t built for me and a story that wasn’t either. Three days later, I’d learned to stand. Three days after that, I’d learned to walk. Three days after that, I’d learned to leave. Now, three days is how long I give any crisis before I answer to check if it still owns me.

The nurse with the comet name texted once more that night. How’s the leg?

Running, I wrote back. Up, this time.

Then I turned off the light, lay in a bed in a city that would never lie to me because cities don’t pretend, and slept like a woman who had finally stopped making herself small enough to fit into someone else’s emergency.

When morning came, I walked down my stairs, all of them, unassisted. At the bottom, the door opened because I pushed it. Outside, the air was new.

And three days later had come and gone again, right on time.

News

I FOUND OUT MY BEST FRIEND WAS HELPING MY HUSBAND CHEAT, SO I GAVE THEM BOTH A LESSON THAT MADE THEM CH2

Part One The first time I saw the hotel charge, I told myself a story. It was a Tuesday, ugly…

My Wife Texted “Let’s Break Up” As A Joke — Then I Showed Her Boss’s Wife The Photos… CH2

Part One — The Text The merger contract blurred before my eyes at the exact second my phone buzzed.Brooklyn: i…

Found My Wife’s Group Chat Called “Operation Divorce Dan” With Her Sisters Planning My “Surprise… CH2

Part One — The Cold Open Three weeks before our tenth anniversary, my wife started humming again. Not a real…

There’s no one to watch my daughter—could she sit quietly in your office?” asked the secretary… CH2

Part One — The Discovery The morning sun broke through the tall windows of the Gran Agency building, spilling pale…

“My brother texted me: “Don’t go home tonight!” I thought it was a joke… until I saw the video at his place — and my whole world collapsed that night! CH2

Ashley’s laugh echoed through the speakers, bright and familiar, yet twisted now into something foreign. The man leaned in, his…

“The Truth at the Wedding” – Rewritten Story in English CH2

On the day of Rareș’s wedding, a woman stood at a distance, watching quietly. Sylwia Pietrowna, his mother, lingered near…

End of content

No more pages to load