PART I — The Sky Over Tulagi

The heat rising off Henderson Field at mid-morning shimmered like glass. It made the world wobble over the coral-hard runway—hangars trembling in vision, aircraft shimmering like mirages. First Lieutenant James Elwood Sweat, age twenty-two, had been pacing the flight line for the last ten minutes, helmet tucked under his arm, flight gloves twisted nervously in his fist.

This was his first combat mission.

197 flight hours in the cockpit.

Zero shots fired in anger.

Zero engagements.

Zero kills.

He had come to Guadalcanal with VMF-221 over two months earlier—February patrols, March patrols, endless April patrols. Nothing but blue sky and boredom. War began to feel like a rumor someone else was fighting.

But at 10:20 a.m., April 7th, 1943, everything changed.

The scramble klaxon cracked across the field like a whip. A harsh, metallic howl that made the air vibrate. Sweat bolted for his Wildcat before the second wail finished. He expected another false alarm. Another empty patrol. Another hour watching clouds drift over the islands of the Solomons.

But then he heard the radio call that froze him in place:

“Bandits inbound. Large formation. Bearing northwest. Altitude unknown.”

It wasn’t the words.

It was the tone.

Calm.

Flat.

Professional.

And unmistakably serious.

Captain Joseph Foss, division leader, sprinted past him and shouted, “Move! Move it! This isn’t practice!”

Foss—already a living legend at twenty-eight—had racked up twenty-six kills. He carried himself with the ease of a man who had seen everything the sky could throw at him. Sweat followed him to the aircraft like a shadow following a lion.

The engine of Sweat’s Wildcat coughed once, twice, then roared to life. The prop kicked up dust and chunks of coral. He lowered his goggles as Foss rolled forward and signaled the division to form up.

Four Wildcats.

Four American fighters.

Against… what? A dozen bombers? Maybe twenty?

The radio squawked again.

“Estimate one-five-zero—repeat, one-five-zero Japanese aircraft inbound.”

Sweat blinked hard.

One hundred and fifty?

His stomach turned to ice. But there was no time to process it. His fighter lifted off the runway and clawed into the sky behind Foss.

The First Sight

They were climbing through 8,000 feet when Sweat saw them.

The sky to the northwest didn’t look like sky at all. It looked like a storm—except storms didn’t fly in formation. Storms didn’t glitter in sunlight. Storms didn’t carry bombs.

Sixty-seven Aichi D3A Vals.

One hundred-plus Zeros flying high cover.

Fifteen bombers in the nearest wedge alone, descending into their attack run on the Allied fleet at Tulagi.

Sweat swallowed hard. His breath fogged the inside of his mask.

Foss came over the radio.

“We’re going in head-on. Pick your target. Don’t miss.”

Sweat wiped sweat from his forehead—ironic, given his name—and tightened his grip on the control stick. The Wildcat was heavier, slower, clunkier than the Japanese Zero, but it was tough. It could take punishment. It could survive hits the Zero couldn’t dream of.

He armed the guns.

The pipper glowed bright, steady.

Six .50-cal barrels waited in the wings.

Twenty-four seconds of total fire time. That was all he had.

Now he was about to spend some of it.

The First Kill

Foss dove first, dragging the rest of the division with him.

The Vals were already committed to their dive toward Tulagi. Their pilots were focused on the ships, not the tiny dark specks screaming toward them at closing speeds approaching 600 mph.

At 400 yards, Foss opened fire.

His tracers stitched the sky, found the lead bomber, and tore its engine apart. Fire blasted from the cowling. The Val rolled over and plunged nose-first into the sea.

Sweat picked the next bomber in line.

350 yards.

300.

250.

He squeezed the trigger.

The Wildcat shook so violently it felt like it was ripping itself apart. Brass casings ejected in a glittering stream past his cockpit. The Val’s canopy exploded. Glass and fabric tore free. The bomber rolled inverted, trailing smoke.

His first kill.

His first three seconds of combat.

Sweat barely had time to breathe.

Another Val slid into his gunsight.

He fired again.

A short, controlled burst.

The left wing sheared off at the root. The bomber spiraled down like a leaf in a storm.

Two kills in forty seconds.

Sweat felt something rising in him—fear, adrenaline, instinct, all blending into a clarity he had never known before. Colors sharpened. Movements slowed. Every aircraft seemed outlined in fire.

The Wildcat wasn’t just responding to him anymore.

It was part of him.

The First Zero

A glint of silver above.

Sweat had enough time to think: That’s too fast to be a bomber.

A Zero dropped past him like a hawk diving through a flock of pigeons.

He yanked right—hard. The G-force compressed his chest. The Zero shot past barely ten feet away, gunports flashing.

Sweat cursed, rolled, and climbed into a tight spiral.

His division was scattered now—Foss somewhere above, the others lost in the chaos. Sweat was alone, hundreds of enemy aircraft all around him, and the sky erupting with black bursts of anti-aircraft fire from the ships below.

He forced himself to breathe.

Slow.

Steady.

Complete.

Then he picked his next target.

Kill Three

A Val diving toward the destroyer USS Aaron Ward.

If Sweat didn’t stop it, that ship was dead.

He pushed the stick forward, diving straight after the bomber. The airframe vibrated as wind resistance stiffened the controls. The needle crept past 380 mph. Sweat’s teeth rattled. His eyes watered.

When the bomber’s silhouette filled his gunsight, Sweat fired.

The Val detonated.

Just… exploded. A fireball where a plane had been.

Sweat shot through the debris cloud, fragments pinging off his fuselage.

Three kills.

Six minutes.

He didn’t have time to celebrate.

Kill Four — The Vertical Attack

Another group of fifteen Vals formed up to begin their bombing run. They flew in perfect V formations—disciplined, focused, oblivious to the danger above.

Sweat climbed to 6,000 feet.

He positioned himself directly behind and above the trailing bomber of the first wedge.

Sun behind him.

Altitude advantage.

The attacker’s dream.

He dove silently.

At 200 yards, he fired a brutal four-second burst—296 rounds—every bullet chewing through aluminum and flesh.

The Val’s tail simply disintegrated.

The bomber entered a flat spin, spiraling into the ocean.

Four kills.

Half his ammo gone.

Kill Five — The Unlucky Bomb Load

He banked left, still carrying speed from the dive, and cut across the second wedge of bombers.

He centered a Val in his sight and punched the trigger.

Sweat saw the hit instantly.

Tracers entered the belly.

Straight into the bomb load.

The explosion was enormous—so violent it rattled Sweat’s cockpit.

Pieces of the Val rained down like burning confetti.

Five kills.

Nine minutes.

He was making history, and he didn’t even know it.

Kill Six — Low Level

A Val fled low over the water toward the Florida Islands.

Sweat followed it down, hugging the waves, spray from the sea misting his canopy.

At 150 yards, he fired.

A perfect burst.

The Val’s fuel tank ruptured in a flash of orange fire. The bomber cartwheeled into the sea.

Six kills.

His ammo gauge told the truth:

400 rounds left.

6–7 seconds of firing time.

Kill Seven — The Split-S From Hell

Sweat pulled up hard, searching for one more target. The sky was chaos—smoke, tracers, burning aircraft, and the thunder of naval guns firing from below.

Then he saw it.

A lone Val beginning a dive toward the cargo ships near Gavutu.

Sweat rolled inverted and yanked into a split-S.

The G-force crushed his chest. His vision tunneled, edges going gray. Sweat felt blood rushing into his skull. The top of his helmet slammed into the canopy.

He pushed through the pain.

Through the narrowing vision.

Through the panic.

At 1,000 feet, the Val’s rear gunner opened fire. Tracers whipped past Sweat’s canopy like burning wasps.

Sweat fired back—two seconds, maybe three.

The Val’s engine caught fire instantly.

It crashed into Tulagi Harbor in a plume of spray.

Seven kills.

Twelve minutes.

He’d become an ace twice over before most pilots clocked a single victory.

But Sweat didn’t even know what he’d done.

He was too busy dying.

Friendly Fire

A shocking, violent impact hit his left wing.

The Wildcat lurched wildly. The stick jerked in his hands.

Sweat’s breath caught as he looked out his cockpit.

A massive hole—two feet wide—gaped in his wing. Fuel streamed out in a white vapor trail.

He’d been hit.

By who?

A Zero?

A rear gunner?

The flak?

No.

A 40mm Bofors shell from one of the Allied ships.

Friendly fire.

The men he was protecting had nearly killed him.

The Wildcat sagged left, bleeding speed, bleeding altitude.

He fired his last burst at the fleeing bomber—emptying what was left of his ammo.

Tracers fell fifty yards short.

His guns clicked dry.

Engine Failure and The Dead Glide

Warning lights flooded his cockpit. Oil pressure falling. Engine heat rising. Black smoke pouring from the cowling. The Zero gunner had hit his oil cooler.

At 240 degrees Celsius, the engine seized.

The propeller froze.

The sudden silence was terrifying.

He could hear himself breathe.

He could hear the wind roar past the broken wing.

He could hear the ocean below.

Henderson Field was three miles away.

He wouldn’t make half that.

Sweat searched desperately for open water.

Found some.

Not much, but enough.

He dropped toward the surface, one last decision separating life from death:

Ditch or die.

He chose to live.

Underwater Hell

The impact was brutal.

The Wildcat smashed into the water tail-first, bounced violently, then plunged nose-down.

Sweat’s face slammed into the instrument panel—breaking his nose with a sickening crunch.

He tasted blood instantly. It filled his oxygen mask. Warm, copper, choking.

Then the cockpit flooded.

The cold hit him like a hammer.

His breath vanished.

His chest seized.

His body fought instinctively to inhale.

He unbuckled.

Tried to stand.

He couldn’t.

Something held him down.

Wrapped around him.

His parachute.

The shroud lines had deployed inside the cockpit.

Sweat was trapped.

Water reached his mouth.

Then his eyes.

Then the canopy filled completely.

Dark.

Cold.

Silent.

He clawed for his knife.

Found it.

Cut blindly.

One line.

Two.

Three.

Four.

Five.

Six—

Seven.

He kicked free.

He rose.

His lungs screamed.

The surface felt like salvation.

He broke through and gasped—raw, painful, desperate breaths.

Gavutu Island floated in the distance.

But sharks floated nearer.

Sharks and Blood

Three shadows circled below him.

Reef sharks—eight feet long, maybe more.

Drawn by blood.

His blood.

Sweat forced himself to swim.

Slow.

Deliberate.

No splashing.

His boots filled with water.

His jacket sank him.

His arms trembled.

He stripped off what he could.

But after ten minutes, he barely covered a hundred yards.

His strength failed.

His vision dimmed.

The sharks rose again.

Closer.

He was going to die within sight of land.

Then he heard it.

An engine.

A boat engine.

A voice shouting:

“Pilot in the water! Hang on!”

Hands grabbed him.

Lifted him.

Dragged him aboard.

He collapsed onto the deck like a dying animal.

He was alive.

He had survived the impossible.

PART II — The Rookie Who Terrified a Fleet

The deck of the Coast Guard rescue boat felt unreal beneath James Sweat’s trembling body—solid, warm, sun-beaten wood under a man who had, moments earlier, been drowning beneath the Pacific.

He was coughing violently, retching up salt water and blood. Every breath stabbed his broken nose. His chest felt like it had been crushed by a hammer. The world tilted around him in a dizzy swirl of ocean and sky.

The Coast Guardsman kneeling beside him shouted toward the helm:

“He’s breathing. Barely. Get us back—now!”

Sweat tried to answer, but the words came out as a wet, gurgling rasp. His lungs still burned. His face was a mask of blood. His goggles were gone; his helmet cracked.

But he was alive.

Alive after fighting 150 enemy aircraft.

Alive after ditching in water thick with sharks.

Alive after a friendly 40mm shell had torn a hole in his wing.

The boat raced toward Tulagi.

Bleeding, but Breathing

They brought him to the dock in just over eight minutes. A Navy corpsman was already waiting with a stretcher.

Sweat swung his legs over the gunwale—and nearly collapsed.

“Easy there, lieutenant,” the corpsman said, grabbing him under one arm. “You don’t have to be a hero now.”

Sweat shook his head.

“No stretcher,” he managed, his voice thick with blood. “I can walk.”

“You’re leaking more blood than a stuck pig.”

“I can walk.”

He did. Barely.

Every step was agony. His nose was shattered, pumping a slow, steady drip down his chin. His flight suit hung open and waterlogged around his waist. Saltwater crusted his eyebrows. His boots squelched with every step.

But he walked.

Marines nearby stopped what they were doing and stared. They’d seen wounded men before—but Sweat didn’t look wounded. He looked resurrected.

The Medical Tent

Inside the canvas tent, the corpsman sat Sweat down on a folding chair, cleaned the blood from his face, and examined the swollen, purple mess that had once been his nose.

“Definitely broken,” the corpsman muttered. “Probably the first thing that hit the instrument panel. You were unconscious for any of that?”

Sweat shook his head.

“No time for unconscious.”

“Lucky. Another inch, you might’ve ended up with the panel in your brain.”

The corpsman packed his nostrils with gauze and wrapped his head in bandages until Sweat looked like a battlefield mummy.

“You want morphine?”

“No.”

The corpsman raised an eyebrow. “You’re bleeding, concussed, nose broken, nearly drowned, and you don’t want morphine?”

“I need to stay sharp.”

“Lieutenant, the battle’s not over yet.”

“I know.”

The corpsman sighed.

“You sure you’re twenty-two? You talk like someone who’s already lived three lives.”

Sweat didn’t answer. He simply wiped the drying blood from his lips and stood.

The Jeep Ride Back to Henderson Field

A Marine supply sergeant offered him a lift in a dusty jeep heading back toward Henderson Field. Sweat climbed into the passenger seat, his limbs trembling.

“You see that pilot who shot down all those Vals?” the sergeant asked.

Sweat stared straight ahead.

“Yeah,” he said quietly. “I saw him.”

The sergeant didn’t know what he meant.

Twenty minutes later, they bumped across coral rubble and rolled onto the sprawling, sunburnt field.

Sweat’s Wildcat hadn’t made it back.

But the man who flew it had.

The Ace Meets the Rookie

Captain Joe Foss spotted Sweat the moment he stepped off the jeep.

Foss strode over—tall, lean, sunburnt, his flight gear still dusted with powder burns and oil stains. His Wildcat sat behind him, engine ticking as it cooled from his own battle.

He took one look at Sweat’s bandaged face.

“You look like hell,” Foss said.

Sweat nodded.

“Happens.”

Foss placed a hand on his shoulder.

“You okay?”

“I’m alive.”

“That’s more than the Vals can say,” Foss replied.

Sweat blinked, unsure how to respond.

Then Foss asked the question.

“How many did you get?”

Sweat took a slow breath. His nose throbbed. His chest tightened.

“Seven,” he said. “Maybe eight. One… I’m not sure.”

Foss held his stare for several seconds.

Sweat looked away first.

“Let’s get intel,” Foss said.

The Debriefing — Making History Without Knowing It

The squadron intelligence officer, First Lieutenant Morrison, arrived with a clipboard and a map of Tulagi Harbor.

He didn’t expect much. Most young pilots on their first mission could barely recall what direction they were flying, let alone detailed kill accounts.

But Sweat wasn’t like most.

The interview lasted thirty minutes.

“What altitude did you engage the first group?”

“Eight thousand feet.”

“Distance?”

“Four hundred yards.”

“How long was your first burst?”

“Half-second. Maybe less.”

“What about target two?”

“Three-fifty yards, cockpit shot.”

Morrison’s pencil scratched furiously.

Sweat’s answers were precise. Concise. Calm. It was like reliving the fight frame-by-frame.

After marking seven confirmed locations on the map—all matched by eyewitness accounts, all matched by ship gunners, all matching the destruction patterns—Morrison looked up.

“Lieutenant—how old did you say you were?”

“Twenty-two.”

“And you said this was your first combat mission?”

“Yes.”

Morrison stared at him.

“You know what this means, right?”

Sweat shook his head.

“It means,” Morrison said, “you just became an ace… twice over… in twelve minutes.”

The tent went silent.

Even Foss’s mouth tensed into a slow, incredulous whistle.

The Airfield Reacts

Word spread through Henderson Field like wildfire.

Seven kills.

First mission.

Shot down by friendly fire.

Ditches.

Escapes a parachute tangling.

Cuts himself free underwater.

Survives sharks.

Swims toward land alone.

Gets rescued.

Walks back into camp.

By sunset, every Marine pilot on Guadalcanal knew the name James Sweat.

Some came to shake his hand.

Some came just to stare at him.

Some came because they didn’t believe any man could shoot down seven bombers and live.

Sweat didn’t feel like a hero.

He felt like a man with cotton stuffed in his nose, saltwater still burning his lungs, and a skull pounding like a drum.

The Recommendation

Three days later, Admiral William Halsey read the report from Guadalcanal while sitting in his command tent aboard his flagship.

He’d seen hundreds of after-action reports.

Thousands.

Most exaggerated.

Many hopeful.

A few flat-out impossible.

But this one—this one read different.

Seven confirmed bombers shot down.

One man.

One fighter.

One mission.

Halsey lowered the paper and stared into space.

“That kid…” he murmured. “On his first mission…”

He turned to his adjutant.

“Write me a recommendation for the Medal of Honor. Today.”

The adjutant hesitated.

“Sir, Medal of Honor recommendations—”

“Today,” Halsey repeated. “If this doesn’t earn it, nothing does.”

The Growing Legend

Within a week, naval aviators across the Pacific began using a new phrase:

“To pull a Jimmy Sweat.”

Meaning:

To accomplish the impossible.

To defy odds.

To destroy the enemy so decisively it rewrites the rules of the sky.

Sweat hated the attention.

He avoided interviews.

He avoided exaggerated retellings.

He avoided letting it become about ego.

“I did my job,” he told anyone who asked.

But the Marines didn’t buy it.

What Sweat did on April 7th had nothing to do with a “job.”

It was something else altogether.

Training the Next Wave

Sweat continued flying combat missions after the battle. He accumulated more kills. More shootdowns. More scrapes with death.

He was shot down twice after his seven-kill mission.

Once over the Solomons—rescued quickly.

Once over Rabaul—three days in the jungle before friendly islanders found him.

It only added to his legend.

Later, when he rotated back to the United States as an instructor, young pilots treated him like a walking gospel.

He taught them:

Attack from above and behind.

Conserve ammunition.

Don’t let adrenaline waste bullets.

Know your fuel.

Never chase a damaged enemy all the way down.

Fear kills faster than enemy fire.

And most importantly:

“Stay calm. You’re thinking with your hands. Don’t panic.”

Men survived because of those words.

Dozens.

Hundreds.

Maybe more.

Sweat didn’t boast.

He didn’t dramatize.

He just told them what he had learned in twelve minutes over Tulagi:

A calm pilot lives. A panicked one dies.”

A Medal Unlike Any Other

On September 24th, 1943, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed his Medal of Honor authorization.

On October 10th, Admiral Halsey placed the blue ribbon around Sweat’s neck during a bright, humid ceremony at Espiritu Santo.

Cameras flashed.

Newspapers printed his story.

Life magazine published a spread.

He stood there, stiff and uncomfortable, face healed, nose still crooked from the ditching.

When reporters asked how he destroyed seven bombers in twelve minutes, he shrugged.

“Right place, right time,” he said.

“Good training.”

“And I didn’t give up.”

It became one of the most quoted lines of the Pacific War.

But Sweat Refused to Be a Myth

Back home after the war, he lived quietly.

Married.

Raised a family.

Joined the Marine Corps Reserve.

Flew jets in the Korean War (but saw no combat).

Retired as a Colonel in 1970.

He never claimed he was special.

Never wrote a book.

Never called himself a hero.

He said the same line every time:

“I was lucky.”

People who knew the real story smiled when they heard it.

Because luck doesn’t hold off a Zero.

Luck doesn’t hit seven bombers.

Luck doesn’t cut parachute lines underwater.

Luck doesn’t survive sharks.

Luck doesn’t swim half a mile with a broken nose and empty lungs.

What Sweat had wasn’t luck.

It was training, courage, instinct, and something else—something the Japanese would never understand:

American refusal to quit.

PART III

Morning turned to afternoon across Guadalcanal with the heavy, heat-soaked stillness that always followed a major battle. The smell of burning fuel drifted over the airfield, mingling with the scent of coral dust, gunpowder, and spilled hydraulic fluid.

Sweat hadn’t slept.

He’d changed into a clean uniform, but the dried blood under his bandages still itched. His nose throbbed with every heartbeat. He sat on an overturned ammo crate outside his tent, staring at the sky—quiet now, deceptively peaceful.

It was hard to believe that just hours earlier, that same sky had been filled with more Japanese aircraft than he’d ever seen in training films, textbooks, or intelligence briefings.

He replayed it in his mind like a film stuck on repeat:

The first Val exploding.

The second spiraling down.

The third erupting into a fireball.

The fourth screaming toward the sea without a tail.

The scattered formation.

The Zeros diving.

The Wildcat shaking from the recoil.

The G-forces crushing his chest.

The sudden, violent silence when the engine seized.

He remembered the water most clearly.

Cold.

Dark.

Endless.

He’d been inches from blacking out when the knife finally sliced the last shroud line.

If he had been one second slower…

One breath shorter…

One cut weaker…

He shook the memory away.

He was alive.

But the battle wasn’t finished with him yet.

The Squadron Gathers

VMF-221—the whole squadron—gathered around him as the afternoon sun arced westward. They didn’t crowd him. Marines didn’t crowd. They formed a circle at a respectful distance, pilots standing with hands in pockets or arms folded, quiet, contemplative, almost reverent.

Captain Joe Foss stepped forward first.

“You did good today, Jim.”

Sweat looked up at him, eyes tired but steady.

“Wish I could’ve brought the airplane home.”

Foss gave a half-smile.

“Son, you shot down seven enemy bombers and survived getting hit by our own ships. You ditch your plane all you want.”

Laughter rippled through the circle.

Even Sweat cracked a faint smile.

Then Foss clapped him on the shoulder—gentle, careful, respectful.

“What you did today,” Foss said, lowering his voice, “is something most men won’t do in a lifetime of flying.”

Sweat didn’t know how to respond. He’d never thought of himself as extraordinary—just prepared. That’s what training was for. Preparing.

“I just did what we trained for,” Sweat finally said.

Foss shook his head.

“No, Jim. Today you did something training can’t teach.”

The Intelligence Officer Returns

First Lieutenant Morrison, the squadron intelligence officer, returned with two more clipboards full of corroborating witness reports. Ship logs. Anti-aircraft gun crews. Pilot testimonies. Everything pointed to the same conclusion:

Seven kills.

Seven definitive, witnessed, indisputable kills.

No shared kills.

No “probables.”

No disputed claims.

Seven.

Morrison looked at Sweat with a kind of baffled respect.

“I’ve never seen anything like this,” he said. “In all my time in combat intelligence—not once.”

He flipped a page.

“You know what the enemy lost today?”

Sweat shook his head.

“Forty-two aircraft total. You accounted for exactly one-sixth of the entire Japanese loss.”

The pilots around Sweat murmured.

“You, on your first mission,” Morrison added. “First. Mission.”

Sweat swallowed hard.

He didn’t feel proud.

He didn’t feel triumphant.

He felt humbled.

Surprised.

Overwhelmed.

And—strangely—grateful that he had lived long enough to feel anything at all.

Nightfall on the Island

As night fell, Guadalcanal grew quiet again.

The wind rustled the thin canvas tents.

The waves slapped gently at the shore beyond the tree line.

Somewhere in the distance, a generator coughed intermittently.

Sweat walked along the perimeter road, head aching under the bandages, nose still leaking now and then.

There were no streetlights—just starlight, moonlight, and the dim glow of smoldering wrecks far out near Tulagi.

The events of the day pressed down on him in the darkness.

Seven kills.

One bleeding aircraft.

One dead engine.

One ditching.

One fight for breath underwater.

Three sharks.

One miracle rescue.

He had done the impossible.

But he didn’t feel invincible.

He felt small.

Small beneath the endless Pacific.

Small beneath the weight of war.

Small beneath the reality that tomorrow—tomorrow—he might fly again.

And the next time, he might not walk away from it.

He leaned against a palm tree and exhaled shakily.

“Get used to it,” he murmured. “This is the job.”

The Radio Call That Changed Everything

Two days later, a runner sprinted across the flight line toward the squadron ready tent.

“Lieutenant Sweat! Radio room needs you!”

Sweat looked up from a maintenance logbook he was helping review—one of the ways he distracted himself when grounded. He followed the runner into a cramped wooden hut with a single fan humming tiredly overhead.

A young Navy radioman handed him a freshly typed message.

Sweat unfolded it silently.

It was from Admiral Halsey’s headquarters.

The words were crisp, formal, unyielding:

RECOMMENDATION FOR MEDAL OF HONOR APPROVED BY ADMIRAL HALSEY.

FULL CITATION TO FOLLOW.

FOR EXTRAORDINARY HEROISM IN ACTION AGAINST ENEMY FORCES.

Sweat blinked.

His breath caught.

The radioman scratched the back of his neck.

“Sir, I think… you’re the youngest guy in the whole campaign to get this kind of recommendation.”

Sweat folded the paper slowly.

“I’m no hero.”

The radioman shrugged.

“Heroes never say they are, sir. That’s why we give ’em medals. To remind everybody else.”

Return to the Skies

Despite the broken nose, despite the lingering pain in his ribs and the sore muscles from the ditching, Sweat returned to flying within a few weeks.

Doctor’s orders said he should rest longer.

War said otherwise.

By late spring, he was airborne again—climbing through tropical air that shimmered with heat and the smell of aviation fuel.

He flew missions across the Solomons.

He shot down more enemy aircraft.

He saw more friends die.

He saw more ships sink.

But every time he strapped into a cockpit, he carried with him a strange peace—because nothing the enemy could throw at him, nothing the sky could hurl in his direction, would ever match the terror of that first mission.

Everything compared to April 7th felt almost… familiar.

He knew the rhythm of the fight.

He trusted his training.

He trusted his instincts.

And more importantly—

He trusted himself.

Second Shootdown — Lavella

The next time he was shot down, he handled it with the same cool precision he’d shown on April 7th.

This time, he didn’t ditch in shark-infested waters.

This time, he landed near friendly troops.

This time, he walked away.

When the squadron recovered him, someone joked:

“Jimmy, you gotta stop scaring the sharks. They’re starting to file complaints.”

Sweat grinned for the first time in months.

Third Shootdown — Rabaul

The third time was worse.

A Zero tore through his tail during a dogfight over Rabaul. Sweat bailed out at low altitude, parachuted into thick jungle, and nearly broke his ankle on landing.

He spent three days alone—hungry, thirsty, sunburned, foot bleeding—before friendly islanders found him and paddled him back to Allied lines in a dugout canoe.

He returned smiling.

“Didn’t see any sharks this time,” he said.

The squadron welcomed him home like a ghost who’d wandered back into the world.

Training the Future

In late 1943, Sweat rotated back to the States for instructor duty.

NAS Jacksonville.

Then Pensacola.

Then advanced gunnery schools.

He taught hundreds of young pilots—fresh-faced, eager, terrified—to fight with their minds, not their fear.

“Short bursts,” he reminded them.

“Never chase a bomber all the way to the water.”

“Zeros climb better than you. Wildcats dive better.”

“Check your six every five seconds.”

“And above all… stay calm.”

One student asked him after class:

“Sir, were you afraid? On your first mission?”

Sweat looked at him a long moment.

“Yes,” he said softly. “If you aren’t afraid, you’re dead.”

When World War II ended, Sweat returned home.

He married.

Had children.

Rejoined the Marine Corps Reserve.

Flew Corsairs during Korea, though he never saw combat again.

He retired in 1970 as a Colonel—humble, quiet, gentle, and forever modest.

If visitors asked about his Medal of Honor, he shrugged.

“Wrong place, right time.”

But his eyes always drifted away when he said it.

Because he knew the truth:

He had faced death head-on

—three times—

and won.

He had killed seven bombers in twelve minutes

—and saved a fleet—

but carried the weight of each moment quietly.

He had survived the impossible

—but never felt invincible.

He had simply done what Marines do:

Everything that needed doing.

Even when no one believed he could.

Long after Sweat left the Pacific, his story remained—whispered in ready rooms, used as instruction in training schools, printed in manuals, and told by old veterans to young Marines.

The principles he lived by became doctrine:

Strike hard.

Strike fast.

Think clearly.

Conserve your ammunition.

Don’t panic.

Fight with your brain, not just your guns.

And most of all:

Never underestimate what a well-trained rookie can do.

Because on April 7th, 1943, a 22-year-old lieutenant with 197 flight hours and zero combat experience rewrote the rules of aerial warfare in twelve minutes.

And the Japanese couldn’t believe it…

Until seven of their bombers were falling out of the sky.

PART IV — The Last Mission of a Lifetime

The decades after World War II rolled forward quietly—one year folding into the next, one generation giving way to another. The Pacific faded into memory for most Americans, tucked into textbooks and documentaries. But for men like James Elwood Sweat—men forged in the furnace of Guadalcanal—memory never faded.

It sharpened.

Sometimes softly, like a distant echo.

Sometimes violently, like a wave crashing against the mind with no warning.

But Sweat had a life to live.

And he lived it the same way he flew:

Steady.

Disciplined.

Humble.

Focused on what mattered.

Life After the War

After leaving active duty, Sweat married a quiet, kind-hearted woman who understood—instinctively—that heroes don’t talk about heroism. They carry it. They bear it. They keep it tucked inside like a sealed envelope.

He worked, built a home, raised children, and settled into the Marine Corps Reserve. When the Korean War came, he flew again—this time in the F4U Corsair. He crossed oceans once more, strapped into another iron machine, ready for combat if fate demanded it.

But Korea had no April 7th moment for him.

No massive formation.

No desperate dogfight.

No showdown with sharks.

Instead, he returned home quietly, never having fired a shot in anger during that conflict.

And he was fine with that.

He never sought glory.

He never chased it.

He never repeated the story unless someone pried it loose.

The Instructor Who Saved Men He Never Met

At the Naval Air Stations where he taught—Jacksonville, Pensacola, Miramar—pilots hung onto his every word. Youthful Marines and Naval Aviators, some barely shaving, stared in awe at the calm, soft-spoken man with a crooked nose and a medal he rarely wore.

But Sweat didn’t lecture.

He demonstrated.

In the classroom, he spoke quietly, but every sentence landed with the weight of experience.

“Your aircraft is a tool. You’re the weapon. Use your head.”

“Short bursts. Long bursts waste bullets. Tracers don’t mean firepower—they mean you’re almost empty.”

“Altitude is life. Speed is life. But calmness is survival.”

“Don’t chase an enemy to the deck. That’s where you die.”

“Check your six. Then check again.”

Young pilots said he never raised his voice.

Never barked an order.

Never tried to intimidate.

He didn’t have to.

Because every man in the room knew:

They were being taught by someone who’d done the impossible.

Someone who had stared down one hundred and fifty Japanese aircraft…

…and walked away.

The Story that Refused to Fade Away

By the time the Korean War ended, Sweat’s April 7th mission had achieved almost mythic status in military aviation circles.

New pilots used his name as a benchmark:

“You’ll never pull a Jimmy Sweat,” instructors teased their classes.

“Nobody will.”

Marine aviators passed the story down like a sacred text.

Navy pilots debated whether it could ever be repeated.

Air Force gunnery manuals included his engagement as a case study.

And year after year, the legend grew.

Yet Sweat never embraced it.

He preferred talking about his students, not himself.

He preferred talking about his squadron, not his medal.

He preferred talking about the men who didn’t come home.

A Quiet Retirement

Sweat retired from the Marine Corps Reserve as a Colonel in 1970.

He stayed in Northern California.

He fished.

He raised his family.

He attended squadron reunions.

But he rarely mentioned April 7th.

He never bragged.

Never asked for recognition.

Never embellished.

He told the truth plainly:

“I did what needed doing. Nothing more.”

His children would overhear stories from visitors—old pilots who still called him “Sir,” even decades after he left active duty. They’d retell fragments of the mission:

“…seven Vals…”

“…friendly fire took him out…”

“…sharks in the water…”

“…cut himself free…”

“…never panicked, not once…”

But Sweat himself never added to them.

He simply nodded politely and changed the subject.

January 15th, 2009

James Elwood Sweat died peacefully at age eighty-eight, surrounded by family.

The Marine Corps sent representatives.

Naval aviators wore their dress whites.

Veterans from three wars attended.

Present, past, and future converged in a single solemn moment.

His Medal of Honor rested at the front of the chapel beside a folded American flag.

A Marine colonel, gray-haired and weathered, delivered the eulogy:

“James Sweat did on April 7th, 1943 what no one believed possible. At twenty-two years old, on his first combat mission, he demonstrated courage, skill, and calmness under fire that changed the course of the Solomon Islands campaign.

His actions saved lives.

His discipline became doctrine.

His instincts became training.”

The colonel paused.

“And he never once claimed to be a hero. That humility… is what made him one.”

Outside, the honor guard fired three volleys into the winter air.

A lone bugler played Taps—slow, mournful, unwavering.

The notes floated across the cemetery, echoing among the stones.

Sweat’s pallbearers—Marine aviators—carried him with reverence to his resting place in Quantico National Cemetery.

As they lowered the casket, the attending Marines saluted in perfect unison.

He had lived long.

He had fought fiercely.

He had taught generations.

He had survived when so many did not.

And in the end, he was laid to rest among those who understood him best.

The Lesson That Outlived Him

Today, his Wildcat rests somewhere at the bottom of Tulagi Harbor—its fuselage rusting, its guns silent, its wings spread as if still diving toward a bomber formation.

But Sweat’s legacy isn’t trapped in the wreckage.

It lives in:

The Marine Corps University curriculum, which still teaches his April 7th engagement.

The National Museum of the Marine Corps, where his Medal of Honor and gear are displayed.

Every flight instructor who teaches students to remain calm under fire.

Every naval aviator who knows the story of the rookie who shot down seven bombers in twelve minutes.

Every Marine who believes that training, courage, and determination can bend fate.

Because Sweat proved one thing beyond any doubt:

Experience is valuable.

Training is essential.

But courage—real courage—can appear in the youngest, least expected among us.

He answered the question historians still ask:

Can a rookie outperform veterans in the crucible of combat?

On April 7th, 1943, James Sweat proved the answer.

Seven times over.

The Final Reflection

If Sweat were alive today and someone asked him:

“How did you do it?”

He would probably smile shyly and offer the same answer he’d given for sixty years:

“I was just doing my job.”

But the truth is larger:

He did what no one believed possible.

He did what training prepared him for.

He did what courage demanded.

He fought when the sky was black with enemy aircraft.

He refused to quit even when the ocean tried to swallow him.

He stayed calm when death pressed in from every direction.

And because of that—

Because one 22-year-old Marine believed he could make a difference—

seven Japanese bombers fell in fifteen minutes.

And the war in the Solomons shifted forever.

THE END

News

The German Soldier Who Was Freezing… Until an American Enemy Saved His Life

PART I — The Reunion in Pittsburgh (1984) & The Beginning of the Foxhole Night (1944) Pittsburgh International Airport…

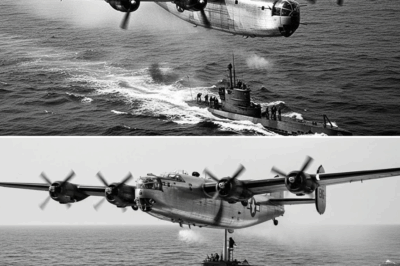

They Rejected His “Illegal” B-25 Modification — Until It Wiped Out 3,000 Japanese in 15 Minutes

PART I The tropical sun over Port Moresby had a way of bleaching every color except misery. It hung harsh…

The Forgotten Plane That Hunted German Subs Into Extinction — The Wolves Became Sheep

PART I The gray Atlantic dawn of May 1943 wasn’t supposed to be beautiful. It wasn’t supposed to be…

How a Female Mossad Agent Hunted the Munich Massacre Mastermind

PART 1 Beirut, 2:47 a.m. The apartment door swung open with a soft click, a near-silent exhale of metal and…

His Friends Set Him Up, Arranging A Date With The Overweight Girl. In The Middle Of Dinner He…

PART 1 Shelton Drake had always believed in two things: discipline and control. He molded his life like clay, shaping…

Bullied at Family Company for “Just Being the IT Guy,” CEO’s Private Email Changed Everything

PART 1 My name is David Chin, and for most of my adult life, I’ve been the quiet one in…

End of content

No more pages to load