Part I

I blew out the last candle when it guttered into a wick of smoke and regret. Hours earlier the dining room had glowed like a scene I’d practiced in my head—red dress, crystal glasses, braised short ribs the way Adam liked, the lasagna he swore tasted better the second day, saffron risotto stirred until my arm burned. I uncorked the wine, let it breathe, and held my breath for a door that never opened.

By ten, the butter had filmed over on the potatoes. By eleven, the flowers bowed. At midnight my phone lit with a text that looked like a message meant for someone else.

Ella isn’t feeling well. I won’t be coming home tonight.

Eleven words. No punctuation that could pass for remorse. In the reflection of the black screen I looked like a woman someone had forgotten to claim at baggage.

I ate the feast cold, fork scraping porcelain. One bite at a time—plate to plate to plate—the way you swallow humiliation: steadily, so it doesn’t choke you all at once. Grease turned to wax on my lips. The wine was astringent as truth.

It was not the first memory that hurt. Memory is a patient collector; it waits for the last piece and then snaps the box shut.

The banquet came back next. The whole Brooks clan arrayed like a painting—citizens of a small country with a currency called reputation. In that picture, Ella Davis stood beside my husband’s father in a white dress that screamed purity so loudly it drowned out every other sound. She was the woman my in-laws introduced as a tragedy: the pregnant fiancée of Adam’s late brother, a widow by technicality and timing. Eyes the color of meltwater. Voice like spun sugar.

Midway through the evening she approached me with a glass of mango juice. “Sister,” she said, “I noticed you haven’t had a drink. I squeezed this for you. It’s fresh.”

Everyone in that family knew mango could put me in the ground. My allergy had its own folklore: the time I swelled after a stray chutney, the EpiPen I carried like a saint’s bone. On cue, the aunts pursed their lips. The uncles smiled. I held her gaze and didn’t take the glass.

“What’s wrong?” she asked, lower lashes trembling like the wings of a small, weak thing. “Don’t you like it? Or are you still angry I’ve taken so much of Adam’s time?”

The table murmured, that special charity reserved for women who play helpless well. Hannah’s petty. Hannah’s cruel. In a family that believed image could baptize truth, I was always the heretic.

Adam arrived like a verdict. He didn’t ask. He took the glass and pressed it to my mouth.

“Drink it, Hannah,” he said. “Don’t make a scene. Stop humiliating Ella over nothing.”

I looked past his shoulder and caught the little curl at the corner of Ella’s shy, lowered smile—the smile of a woman who understood the mathematics of pity. Then I opened my mouth and drank.

Fire hit my throat first, then the bruising weight that comes when breath decides it is done with you. I clawed at air that had turned to wet cloth. The chandelier’s crystals fractured into stars. Voices swam far away and then close, a tide of stupidity.

“Call an ambulance!”

“Damn it, she’s actually allergic.”

Actually.

Shocking, that truth could trump narrative for a single breath.

The third memory’s edges were furred with rage. Snowball—my mother’s cat, the last soft thing she left me—had scratched Ella. A faint crescent. No blood. Ella cried the way actresses cry when they’re auditioning for the role of the wronged.

Adam came home to find her weeping and me holding the cat like contraband. “It wasn’t Hannah’s fault,” Ella sobbed. “I shouldn’t have gotten close. I forgot it doesn’t like me.”

“It’s a danger,” Adam said, and tore the animal out of my arms. “Hannah Moore, enough. The cat has to go.”

“It’s my mother’s,” I said, lunging for the warm, frantic body.

“It’s just an animal,” he said. “Does it matter more than Ella’s safety?”

He had a way of making cruelty sound like policy.

The memory shattered because something on my skin burned in the present. I shot upright in the dark, throat swelling, hives rising in angry constellations. My tongue felt like it belonged to someone else’s mouth. Breath turned into a coin flipped by a stranger.

On the tray by my bed lay the film of porridge I’d forced down in the asylum ward because the orderly stood over me until I did. A sweet, faint note lingered. Mango. Of course. Slow knives hadn’t worked. They’d decided to go faster.

The room reeled. The ceiling dropped. A part of me wanted to surrender to the old script: panic, plead, hope for rescue from the people who’d put me here. The rest—the part that had finally learned the lesson—knew the only help I was ever going to get would be the kind I gave myself.

I slid a shaking hand into the seam of my pants where I’d hidden a shard of porcelain weeks ago, chipped from a sacrificial bowl the day the staff left me alone with a tray and bad intentions. I dragged the edge across my wrist. Hot red opened like a door.

Pain sharpened the world. Blood sheeted onto the tile. I kept my eyes open and counted, not seconds but choices I would never make again if I survived the next ten minutes. The wristbone ticked like a metronome under the pulse. Then the hall erupted—keys, shouts, the bright cone of a flashlight—an orderly on rounds seeing a tableau he would never get out of his head.

“Help! Patient’s bleeding out!”

“Transfer! Now!”

“Miller! She’s in anaphylaxis and hypovolemic shock!”

Jason Miller, the asylum’s director—a man with a handshake he thought passed for ethics—appeared in the doorway and blanched. He was afraid. Not for me. For himself. The Brooks family paid well to keep me inside these walls and quiet. A dead madwoman collects debts a live one cannot.

They ran me down the corridor. Between the asbestos ceiling and the flicker of lights there was a blind spot in the cameras, a ten-meter mouth where the building swallowed images. I’d measured it with my eyes months before; fear makes you an engineer. As we hit that shadow, the younger nurse—Lily Brown, the med student my father once quietly sponsored—stumbled. The gurney tilted. The sheet slid.

“Sorry!” she hissed, leaning down, and pressed something thin and cold into my palm. “Miss Hannah—Tyler Bennett is waiting in the morgue. Godspeed.”

A surgical blade sat in my fist like a curt promise. Lily’s face was a slice of composure above her mask. Then we were in motion again, lights strobing, voices barking, my body a task.

The ER was fluorescent and frantic. “Adrenaline! Now!” “Epi!” “Defib—clear!” My world narrowed to the beep-and-dip of machines and the unimportant thought that a heart remembers how to be dramatic even when a person tries to leave quietly.

Half an hour later, the attending dropped his mask and announced the words men like Adam use to end messes.

“Time of death.”

They tagged my toe, pulled a sheet over my face, and rolled me to the basement.

The morgue breathed disinfectant and cold. After footsteps receded, I slid the sheet down and sat up. The metal under me hummed. Opposite, a man in a black trench coat stood with his back to me, hands in his pockets, posture like a blade in a museum case.

“Mr. Bennett,” I said. My voice was paper rubbed thin. “You made it.”

He turned. The tabloids showed Tyler Bennett smiling; the man in front of me did not. He was beautiful the way storms are when you understand the math—angles, pressure, inevitability.

“You brought the deposit?” he asked, like we were trading crates at a dock.

He tipped his chin toward a brushed aluminum case. I slid off the table, bare feet on ice, crossed the tile, and began.

“Brooks Group Q3—offshore project costs inflated by thirty-seven million to scrub taxes. CFO Parker. Ledgers are in his mistress’s apartment, Eastern District, Unit 9B—name on the lease is her sister’s. The antiques used to cover a five-million bribe on the Southern City land bid were authenticated by a private appraiser on June 12—audio at the club, locker four, code 0-6-1-2—chairman present, Adam overseeing.”

I went on. A litany. The secret spine of the empire I’d married into and then picked apart in the sleepless nights when waiting turned into arithmetic. I had read Adam’s encrypted files after he joked I wouldn’t understand the spreadsheets. A wife no one looks at is a wife with excellent access.

Tyler’s face moved through disbelief to attention to something like respect. When I stopped, he flicked the latches and opened the case. Inside: a passport, state ID, a birth certificate for a woman who did not exist and yet somehow was already me, a black debit card tied to a Swiss account.

“Deal’s done,” I said. “You make my death look real. You give me everything I need to be nobody. And when the Brooks fall, you strip the carcass. I take my pound of flesh somewhere else.”

He studied me the way a man might study an animal he’d never seen before and wasn’t sure he wanted to meet again. “Is it worth it?” he asked. “Turning yourself into a ghost to get revenge.”

“Dead woman?” I laughed. It came out like an echo in an empty theater. “Hannah Moore died the day they locked her in a ward and called it treatment. What’s walking out of here is a revenant. She has work to do.”

In the morning, the asylum called Adam. Tyler had seeded a bug in Jason Miller’s office phone. I sat in a safe house with a cup of tea and listened to my husband receive my death like a memo.

Jason wept through a script about failed supervision. “We did everything we could, General Manager Brooks.”

Silence. I thought the line had died. Then Adam spoke, voice flat. “Understood. Cremate the body. Keep it simple.”

There it was—irritation, impatience, his two native tongues—turning the end of a marriage into an instruction to take out the trash.

An hour later, Tyler delivered my first gift. Tax police and the economic crimes unit hit Brooks Group headquarters like a storm surge. The chairman—Adam’s father—was walked out in cuffs as junior analysts pretended to answer phones. The feed room—where they had hid the skeletons—blew open into air and light.

Not enough.

“Pull the other thread,” I told Tyler, and the contract team sent a notice severing Brooks from Moore Group—my birth family’s business, their largest client. Payments, frozen. Projects, canceled. In a single afternoon the stock dipped so hard it needed a rescue before lunch.

Tyler watched me from his chair in the safe house, long legs crossed, mouth considering. “You just lit your own house on fire to smoke them out,” he said. “Colder than I imagined.”

“What’s a house that shelters the wolves who ate your child worth?” I asked quietly. “If Moore Group only lives because Brooks feeds it, it’s already dead. I’ll build something that doesn’t kneel.”

He didn’t argue. He handed me a small package and said, “You asked for this.”

Inside, a music box. My mother’s. The ballerina’s head had been snapped off and nestled beside her like an answer I didn’t want and had given myself anyway. My handwriting on a note I’d prepared weeks ago:

First offering.

Adam, you taught me: when cutting the grass, pull the roots.

I’m starting with mine.

That evening the courier delivered the box to the house Adam and I shared. Through a camera in the smoke detector—my own quiet blessing on a home that had refused to protect me—I watched him open it. He touched the broken dancer with a reverence he had never given me. He read the note and went still the way men go still when the past starts speaking in their handwriting.

He called the asylum. “Where is Hannah Moore’s body? I want to see her.”

“C-cremated, sir,” Jason stammered. “Per your instruction.”

The sound Adam made then wasn’t grief. It was the noise a man makes when he realizes the puppet has taken the strings.

Day two, Tyler lit the match we’d been saving for the pyre. An anonymous exposé appeared under the byline of a former Brooks family physician—a long, clinical essay about a patient he called “Ms. S,” a woman of education and standing locked in a “rest home” after she refused to accept a family’s plan to marry a pregnant mistress into their line. Ugly words—discipline, concubinage—that belonged to literature and the past sat next to photos that belonged to police: a spiked wooden saddle; a branding iron; a wall with the word DISCIPLINE stenciled above restraints.

Attached medical notes—redacted except for severe depression with psychotic features and the inventory of injuries no doctor wants to write: unexplained burns. Genital lacerations. Bruises that mapped the body like a country. And the coda: questions about a car crash that killed Adam’s brother, about a pregnancy timeline that refused to behave like math, about the speed with which the “widow” had arranged to inherit after the funeral.

The internet metastasized. Holy hell—this is the 21st century. Branding iron? If this is true, lock them all up. Ms. S is a real-life Gone Girl except she didn’t run, they caged her. Timeline doesn’t match? Whose baby is it?

Adam did what men like Adam always do in a storm—he ran the pregnant woman up the mast as a flag. He posted a photo of Ella in a hospital bed, damp and white and trembling. Leave her alone. Don’t harm an innocent.

Tyler’s PR team didn’t even break stride. Within ten minutes, my husband’s plea was being stitched with commentary: Classic abuser tactic: hold a “weaker” person in front of you and call it love. Translation: please don’t interrupt the inheritance transfer.

If Adam had hoped for mercy, he found a mirror instead. He smashed his phone. He staggered down a corridor while Ella clutched her belly and moaned for an audience. He went home.

The house was empty. I had moved everything out three days earlier with the deed in my name. A year ago—back when the company was hemorrhaging—I had injected half my dowry to keep it breathing. In exchange, I took the deed to the one place that had promised to be mine. Adam signed the papers with a smirk and a comment about sentimentality. He remembered that now, standing in a hollow room that remembered him back with nothing.

He found my note in the bedroom.

Adam, the house is gone.

Are you satisfied now?

He sat on the floor and sobbed into his hands. For a moment I saw the boy he’d once been and wanted pity to be a virtue again. Then I remembered pity had cost me years I could never recover.

The endgame was a file sitting in a digital attic no one knew existed except me. The dash-cam footage from Samuel’s car—the one I’d given him as a wedding present, the one whose camera backed up to a ghost account. The video captured the last ten minutes of his life: Ella’s voice insisting on a baby that math refused; Samuel’s fury breaking into a call to his father to end the engagement; Ella’s hands grabbing a wheel.

Metal screams the same in all languages. The car rolled, and the world went dark. Audio survived. Samuel’s breath rattled out the truth in Adam’s ear. The child wasn’t his. Ella had grabbed. Don’t let them in. A vow, a request, a command. And after—quiet, then Adam’s voice on the phone, telling his father he would “take care of” his brother’s widow. The words of a man sentencing himself, and me.

We gave the file to the police.

By sunset, Ella sat in an orange jumpsuit, booked for intentional injury causing death. Adam went in for obstruction and perjury. The chairman remained in custody on bribery and tax evasion. Brooks Group fell like a building whose beams had been quietly sawed for years and then invited to host a party.

I stood before the safe house window and watched the city’s lights blink, one floor at a time, like a heartbeat. Tyler leaned in the doorway, sleeves rolled, expression unreadable.

“It’s over,” he said.

“For today,” I said. “Tomorrow we start something else.”

He smiled, and it wasn’t unkind.

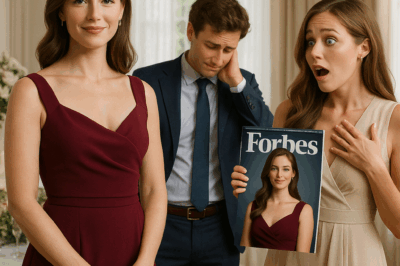

Two years will pass in the next parts. I will wear a white suit on the cover of a magazine under a headline that includes my name and the word Capital. Adam will sweep the stone of an empty grave with a devotion he never gave a living woman. We will meet once, under a chandelier that pretends money can purify anything. He will stare as if I am a ghost. I will pass him like a draft.

But that belongs to the ending.

For now there is the morgue and the cold and the freedom that comes from choosing the last death you will ever suffer.

Outside, a siren wound down. Somewhere above me, a nurse poured coffee into a paper cup and called it dinner. Somewhere across town, a woman in a white dress rehearsed her tears.

I lay back on the steel and closed my eyes. The revenant slept.

Part II

The first thing the madhouse taught me was the sound of a lock that believes in itself. Home locks click; asylum locks commit. The door swallowed the hallway light and left me in a room the size of a storage unit with a single narrow window too high to reach and a bed bolted like a warning.

“Welcome to wellness,” the intake nurse said, and tied a bracelet around my wrist stamped S-17 / MOORE, HANNAH like a raffle ticket at a county fair.

On my second day, I learned the phrase that would become a drumbeat: “It’s been 90 days, go see if Madam has learned her lesson in the madhouse.” Orderlies said it the way you say trash goes out on Tuesdays. Signal word Madam because a certain kind of cruelty loves mock courtesy.

Jason Miller, director, shook my hand with the careful angle of a man who practices seeming humane. “Rest, Mrs. Brooks,” he said. “Your husband wants the very best care. He loves you very much.”

“Does he,” I said, and watched his eyes flick—a tell he never managed to hide.

Day four, I met the room with DISCIPLINE stenciled above a row of restraints like a creed. Metal and leather sat on shelves under bright hospital light: cuffs, straps, devices with an old-world logic that tried to dress itself in clinical vocabulary. The staff called them “behavioral compliance supports.” In another century they would have called them what they were.

The first time they strapped me to the spiked wooden saddle because I “refused nutrition,” I understood the math of pain—how to breathe around it, ride it like a wave, make it a number I could survive. When your world narrows to counting, you discover there are worse prisons than walls. There are the ones you build inside your own head to survive what men like Adam call tough love.

Ella visited on day six. She wore crisp hospital white and eyes that begged while her mouth smiled. Jason hovered at the door with a clipboard like a chaperone at a dance. “I brought you flowers,” she said, as if plants could breathe for me.

“Take them home,” I whispered. “Hold them when you tell him what a good husband he is.”

She flinched, then leaned close enough that I could smell her perfume—a cloying sweetness that made me think of ripe fruit left too long on a counter. “You could come home,” she breathed, soft as a lie. “Apologize. Stop embarrassing Adam. We’re a family.”

A family. She had memorized the script. I bit down on the inside of my cheek until I tasted iron and did not give her the performance she was hunting for.

When she left, Jason stood in the doorway and waited for my apology. I gave him my silence. It was the only currency I had that couldn’t be confiscated.

Day twelve, I became a problem list on a whiteboard: noncompliant, delusional, hostile. My response to the mango-colored “nutrition supplement” was written in a tight hand: excoriations consistent with scratching; erythema noted; possible psychogenic origin. There is a special genius to people who can write your body says no and still call it your imagination.

Lily Brown didn’t belong in that place. She was a med student on rotation, cheeks apple-flush from not yet knowing exactly how much her life would cost her. The first time she lifted my chart and set it back down, she said nothing. The second time, she slid a paperback between the pages: The Art of War in a thrift-store edition with a cracked spine.

“There are no wasted weapons,” she said under her breath, looking at my arm, at the knots the restraints had left behind. She meant the phrase as a comfort. I took it as a directive.

By day twenty, my world had shrunk to a schedule I could recite from memory: 06:00 wake, vitals; 06:30 pills; 07:00 breakfast; 09:00 group; 10:30 individual; 12:00 lunch; 13:00 quiet hour; 15:00 exercise; 17:00 dinner; 20:00 lights. “Therapies” calibrated to prove you’d learned the lesson the madhouse promised to teach: that your will meant less than their paperwork.

In group, a woman named Tamsin counted wallpaper seams and whispered, “They put you here because they don’t want to talk to you in places with windows.” A man named Paul folded tissues into boats and let them sink in his water cup. People become metaphors when everything else is taken from them; it’s the last rebellion art permits.

Day twenty-eight, an orderly I hadn’t seen before delivered my tray, eyes down. The porridge smelled wrong. At first I couldn’t place it. Then I did. Mango is a perfume pretending to be food. I lifted the spoon and smiled at the camera in the corner: a bland little eye mounted near the ceiling. I made a show of eating while I slipped the spoon into my sleeve and scraped porridge into the trash. After lights-out, I spent an hour gagging it back up in the toilet to prove my body to myself and then lay awake cataloging the ways men make women believe they are crazy.

Lily began to visit on nights she wasn’t supposed to be on my floor. She walked in under the glow of the exit sign like an apology for all the doors we pretend are there to save us.

“Why are you helping me?” I asked.

She looked at the camera, then looked back at me. “Because girls like me end up married to men like him if we don’t pay attention,” she said. “Because your father paid for my MCAT class when my mother couldn’t and told me to pay it forward. And because when I was rounding with Jason last week and you asked for your EpiPen and he said you were seeking attention, I wanted to set the building on fire.”

We started building a map that night: the blind spot between the main corridor and the ambulance bay, the gurney with the sticky wheel that always spun to the left if pushed too fast, the orderly who smoked behind the dumpster and took eight minutes instead of five to return from his breaks, the clatter pattern of the elevator when the second-floor stop button stuck. Fear makes you a surveyor. Hope makes you an engineer.

I found the porcelain shard the way a prisoner finds a friend—accidentally, then urgently. They served a stew in a sacrificial bowl that cracked down the side when it met the tray. When the orderly looked away, I palmed the crescent and palmed the splinters too and smuggled them to my room tucked into the elastic hem of my pants. Every night after that, I ran my thumb along its edge until the pain turned into a promise.

Day thirty-five, Jason walked into my room with a man in a suit whose cufflinks cost more than any nurse made in a week. The man looked at me the way you look at art you don’t understand but want to sell.

“General Manager Brooks is very concerned,” Jason said. “He asked Mr. Weber to make sure our…progress…aligns with his expectations.”

Mr. Weber smiled the way sanctions smile before they blow up countries. “A woman of your status should be grateful. Not many husbands invest so generously in their wives’ wellness.”

“Grateful,” I repeated, feeling the word in my mouth like a pit. “To be locked up because I refused to drink a poison in a white dress at a family dinner.”

He blinked. “I see we are still experiencing distortions.”

“I see you brought a thesaurus,” I said, and marked his jaw tick for later.

After he left, Lily slipped in and pressed her hands into her coat pockets to stop them shaking. “He told Jason they’ll sue if there’s an incident,” she said. “So we make one,” I said. It wasn’t a joke. You cannot leave a cage politely. You write your own paperwork.

By day fifty, the nurses had learned to say my name with the tight patience of people who think time will wear you down. “Hannah,” they said. “Let’s try to engage,” and “Hannah, you’re not helping yourself,” and “Hannah, we can make this easier.”

“‘Easier’ isn’t the same as ‘right,’” I said, and counted my breaths while they counted my pills.

Lily delivered information like contraband: which attending could be distracted by a coffee spill (Dr. Chen), which camera feed lagged by six seconds (the corridor outside radiology), which resident had a crush on which nurse and could be baited into a conversation as the gurney rolled by (Mason/Evelyn, radiology/cardiac). We stopped calling it escape. We called it transfer. Language is not decoration. It is architecture.

Day sixty-one, they moved me to a different room “for my comfort.” It was closer to the nurses’ station, farther from the blind spot. I waited three days and then asked for a shower and pulled the fire alarm with a bobby pin while the water pounded. Sprinklers wept in the hallway. We timed the response: eight minutes to reset; nine minutes to restart local cameras; twelve for the off-site security vendor to confirm the all-clear. Every drill was a rehearsal for the play the hospital didn’t know it had agreed to stage.

On day seventy, I woke to the sound of someone crying in the next bed over. Tamsin. She’d been strapped to the wooden saddle again because she tried to keep her eyes open on Night Rest. “It hurts,” she whispered through her teeth. “I know,” I said. I don’t remember when I started using we instead of I. Somewhere between the first strap and the last.

I learned the smell of mango before I tasted it. They laced the porridge again. I pretended to eat. Lily hissed “No” under her breath as she slid the tray away. The orderly smiled at the camera like it was a person.

“It’s been 90 days,” Jason said that afternoon at rounds. “Let’s go see if Madam has learned her lesson.” He said it to the interns like a line from a play he loved.

“Madam,” I said, as they filed in. “What a lovely word for a woman you refuse to call by her name.”

He folded his hands. “If you comply with treatment, we can revisit discharge.”

“Discharge to where?” I asked. “Back to the man who sent me here because I made him choose between his mother’s cat and his mistress’s feelings?”

Whispers in the hall later—hiss, shush, the way a building talks about a person it would prefer not to house. Lily’s mouth a flat line when she came to check my pulse. “It’s time,” she said. “Tonight. Between the asylum and the ambulance bay.”

“You sure?” I asked.

“Sure is a luxury,” she said. “We have necessity.”

I didn’t sleep. I lay on the bed and watched the clock tick toward the moment everything would either end or begin. When the door opened at 03:14, four people stood in the hall who would lose their jobs if anyone ever learned their names. Lily. A young nurse who had a brother the system had chewed. An orderly who had seen his mother packed away like a seasonal decoration. A resident who wanted to be the kind of doctor he’d promised his grandmother he’d become.

We moved. The hallway stretched and contracted like a lung. I could feel the cameras blink as we passed—the tiny click of menace.

Between the asylum and the ambulance bay there was a ten-meter long, three-meter wide rectangle of blessed incompetence where renovations had taken a camera down and never put it back up because budgets are prayers men say when they don’t intend to do the work. We hit it. Lily “stumbled.” The gurney tilted. The sheet slid. And the blade kissed my palm.

“Godspeed,” she whispered. I nodded, a motion so slight a camera would have called it a tremor.

The rest is the part you already know: the ER, the bright theater, the settled theater of death. But here is the piece that belongs to the ninety days and not to the morgue: when the attending called time, his hands were steady. When the nurse drew the sheet over my face, hers shook. When the orderlies rolled me toward the elevator, one of them murmured, “I hope you get out.”

“Me too,” I said under the sheet. No one heard.

You cannot leave hell without carrying some of it with you. In the safe house, awake and alive and labeled dead, I still woke at 04:00 to the sound of locks in my head. I showered with the door open. I kept a glass of water by the bed because in the ward they rationed cups. The blade sat on the nightstand for a week until I could set it in the drawer and leave it there and nobody took it away.

Tyler watched me the way a scientist watches a formula: clinical respect, occasional curiosity. “You catalog everything,” he said once. “Even your ghosts.”

“Cataloging is how you keep the ghosts from owning the library,” I said, and he didn’t laugh, which is why I kept trusting him.

He asked for dates and names and places, and I gave him more than he’d asked for. In return, he moved faster than I’d hoped. He had a talent for turning rot into leverage and leverage into law. He was a man who understood how stories move markets and how markets move men. If Adam had been a weather vane, Tyler was a barometer. He didn’t predict the storm. He measured the pressure drop and bought the company that built the roofs.

On my first night out, I slept for two hours and then lay awake and listened to a city that didn’t know it was about to wake with me. Somewhere a bottle rolled in an alley. Somewhere a cab honked like it had an opinion. Somewhere a man turned to a woman and said something he would never have to pay for. I put my hand flat on the wall and felt the building hum.

“Tomorrow,” Tyler said from the doorway, a glass of water in his hand like an offering. “We start.”

“We started ninety days ago,” I said. “Tonight is just the first time anyone else gets to see it.”

He nodded. “You have a message ready?”

I looked at the music box—my mother’s ballerina’s head tucked in a velvet coffin—and the note folded beside it.

“Yes,” I said. “I wrote it in my head the night they strapped me to a saddle and called it care.”

He took the box like it weighed what it was: grief sharpened into a weapon.

“Sleep,” he said.

“I’ll sleep when the house is quiet,” I said.

He didn’t argue. He never argued when I said house. He knew I meant an empire. He knew I meant a family. He knew I meant all the places women are told to be quiet in.

If you want a neat lesson from ninety days in hell, you haven’t been listening. I did not come out gentle. I did not come out “healed.” I came out precise.

The difference between twenty-four hours and ninety days is that after a day you still think you might be rescued; after three months you know no one is coming and you build the exit yourself.

I built mine out of a broken bowl, a blind camera, a med student who refused to let her gratitude go stale, an enemy who hated my husband more than he needed me alive, and a city that likes to watch a man fall when he’s convinced everyone he can’t.

You already know what happened when I opened my mouth in the morgue and sold him the coordinates to his ruin. You know the raids and the headlines and the way public opinion ate the Brooks brand like fire eats dry wood. You know the post Adam wrote about a pregnant woman, the one Tyler turned into a shield that crushed him.

But the thing you do not know—the thing no one ever knows about women like me until we show them—is that we do not come back to be thanked. We come back to level the ground.

When Jason Miller goes to sleep, he hears the beep of a heart monitor phantoming in his ear. When Ella Davis stares at the ceiling of her cell, she sees a dashboard and a guardrail and a moment when she could have pulled her hand back. When Adam Brooks closes his eyes, the word DISCIPLINE flashes, and under it my face, not bruised or broken, but boring holes through him with the patience of a woman who finally has time.

“It’s been 90 days,” they said. “Go see if Madam has learned her lesson.”

I did.

It was not the lesson they meant.

Part III

The raid should have been the end of the Brooks family’s illusions, but pride makes people rebuild façades even while the foundation smolders.

By noon the day after the authorities swarmed their headquarters, the city was a bonfire of rumor. Screens in every café scrolled the same feed: footage of the chairman led away in cuffs, face paper-white, tie askew. Analysts shouted into cameras about “systemic irregularities” and “unconfirmed allegations of bribery.”

But in the silence between headlines, one thing was clear: the Brooks family was no longer untouchable.

And in that silence, I began to speak.

Tyler had arranged a press leak through a friendly outlet. “Anonymous Source within Brooks Family Speaks of ‘Caged Daughter-in-Law.’”

The article ran with a single photo: me, thinner than I’d been in years, eyes hollow but sharp, sitting at the asylum dining table with a tray in front of me. A guard’s shadow stretched across my lap like a leash.

The photo did not say my name. It didn’t have to.

Social media caught fire. Who is she? Is this the woman in the viral exposé? She looks like a ghost.

Within hours, the words Brooks Family Asylum trended across every platform. Hashtags multiplied like sparks on dry brush: #JusticeForMsS. #DisciplineIsAbuse. #BrooksCollapse.

Tyler’s PR team fanned it just enough to keep the blaze alive but not enough to look artificial. He believed in letting outrage breathe on its own; he was right.

By sunset, the city was a tinderbox.

Adam Brooks was not a man who surrendered headlines.

That evening he appeared in front of the cameras outside the Brooks Group’s glass tower. He wore his grief like a suit—creased in the right places, dark enough to draw sympathy. Ella Davis stood beside him, fragile in cream, her hands folded over her swollen belly.

“My father has been taken into custody,” Adam announced, voice low, heavy with the weight of “duty.” “We respect the process. But I must ask the public to be cautious. Rumors are cruel things. Innocent people—my family—are being dragged through the mud.”

Then he reached for Ella’s hand. She blinked, lashes trembling, her lips parted in a pale bow.

“Leave her alone,” Adam said. “She is an expectant mother. She has suffered enough. If you must condemn someone, condemn me. I will bear it.”

It was a performance tailored for sympathy. A man shielding a delicate, grieving woman. The optics were precise: Ella’s soft whiteness contrasted against the city’s fury, Adam’s broad shoulders angled as if he could absorb the blows.

And for a moment, it almost worked. Comment threads filled with pity. Whatever happened, don’t drag the pregnant woman. He looks devastated. Maybe it’s all lies.

But sympathy is volatile. One wrong touch and it flips.

Ten minutes after Adam’s speech, Tyler pressed “send.”

Hundreds of influencer accounts, journalists, and anonymous voices posted the same thought in different words:

Classic manipulation: abuser uses a weaker victim as a human shield.

Translation: Don’t stop me from securing my mistress’s inheritance.

Am I the only one who sees that the more he protects her, the guiltier he looks?

The phrase Using a Pregnant Woman as a Shield rocketed to the top of the trending searches.

By midnight, Adam’s plea for pity had become the clearest proof of his guilt. Memes spread faster than truth: Adam holding Ella like a shield against a storm of police files; Ella painted as the “eternal damsel” while women in the comments spat fury.

In the hospital, Ella watched the storm unfold on her phone. Tyler had arranged a feed of her private messages—every sobbing DM from her friends, every whispered warning from relatives telling her to lie low.

She cracked.

Adam stormed in past midnight, reeking of whiskey and fury. “Who leaked the story?” he snarled, grabbing the edge of her hospital bed.

Ella widened her eyes, tears already waiting. “Adam, please—why are you accusing me? Didn’t we agree never to mention it again?”

He shoved the phone in her face. “They know about the asylum. About Hannah. About you.”

“I don’t know!” she sobbed, twisting in the sheets. “You’re frightening me—”

Doctors rushed in, hands raised. “Mr. Brooks, step out! The patient is in distress!”

As they escorted him into the hall, Ella curled around her belly and wailed, a sound designed for the microphone of pity. Adam, drunk and desperate, still believed her.

But the cameras outside the hospital had already recorded his stagger, his slurred threats, his loss of control.

By morning, the city had seen the cracks.

That night Adam returned to our home.

He must have thought the house would comfort him—the curated photographs, the rug I’d chosen, the curtains I’d fought for, the faint scent of lavender I sprayed when I needed to remind myself there was softness in the world.

But the house was hollow. I had emptied it days earlier with the deed already in my name.

When he called his lawyer, frantic, the man reminded him of the document he’d signed a year ago. Half my dowry poured into Brooks Group during a liquidity crisis, in exchange for the property rights to the marital home. He’d mocked me then. “A house? You could buy ten of these with the interest.”

Now he stood in an echo chamber with nothing but his reflection.

And in the master bedroom, he found the note I’d left.

Adam, the house is gone. Are you satisfied now?

The surveillance camera hidden in the smoke detector captured him crumpling onto the floor, sobbing into his hands. For the first time in his life, Adam Brooks cried where someone could see.

The city needed a final spark to turn outrage into fire.

I gave them the dash-cam file.

Samuel Reed, Adam’s brother, driving the car I had gifted him. Ella in the passenger seat. Their argument recorded in tinny clarity:

“You expect me to raise another man’s child?” Samuel’s voice cracked with fury.

“Don’t say that!” Ella shrieked.

“I had the test. I know. Severe infertility. The math doesn’t lie. Whose child is it, Ella?”

“Samuel, please—”

“I’m calling Father. The wedding is off. You’ll never enter the Brooks family.”

The sound of the wheel being wrenched. Tires screaming. Metal folding. The roll.

Then Samuel’s gasps, fading. “Adam… it was Ella… she grabbed the wheel… the baby isn’t mine… don’t let them in…”

Silence. And then Adam’s calm voice, speaking to his father: “Our brother is gone. We must take care of his wife. The child cannot be fatherless. I will marry her in his place.”

The file went public at dawn.

The arrests came by noon.

Ella Davis, charged with intentional injury leading to death.

Adam Brooks, obstruction of justice and perjury.

The chairman, bribery and tax evasion.

Brooks Group stock collapsed. Partners severed contracts. Employees fled. The skyscraper that had once gleamed like glass certainty now looked like a mausoleum in daylight.

And the city—my city—watched, hungry.

From the safe house, I sipped tea and stared at the skyline.

“It’s over,” Tyler said beside me.

“For them,” I corrected. “For me, it’s just beginning.”

He studied me, a faint glimmer of respect breaking through his usual mask. “You burned them to ash. What more do you want?”

“A foundation,” I said. “Something new. Something mine.”

He nodded slowly. “Then let’s build it.”

Two years later, the magazine cover hit the stands:

Hannah Moore, Founder of Hannah Capital — The Woman Who Rose From Ashes.

The photo showed me in a white suit, standing before a skyline that had once caged me. Confident. Composed. Alive.

Moore Group was gone. In its place stood my empire, built with Tyler’s counsel but mine alone in vision.

I had learned what ninety days in the madhouse could teach: silence is a weapon, pain is data, survival is strategy.

The city burned, and from its fire, I stepped forward.

Adam Brooks, by contrast, was released early for “good behavior.” He wandered the cemetery where my name sat on an empty slab, brushing away leaves from stone that covered nothing. Sometimes he sat for hours, mumbling to a ghost who would never answer.

He became a ghost himself—threadbare clothes, sunken eyes, muttering about the wife who never died.

We crossed once, in Switzerland, at a business summit. I was on stage, speaking about resilience and growth. He hovered at the edges of the crowd, gaunt, broken, staring at me like a man staring at a vision.

I let my gaze pass over him without pause. To him, I was a haunting. To me, he was an erased page.

No hatred. No love. No recognition.

That was the cruelest judgment I could give.

Part IV

The firestorm that consumed the Brooks family didn’t end with their arrest.

It spilled into boardrooms, investor calls, and late-night strategy sessions across the city.

Every competitor circled like wolves around a fallen stag. And in the middle of that chaos, I planted my flag.

Hannah Capital was born inside a rented office with gray walls and two secondhand desks. The sign on the door was printed on paper because I hadn’t yet bothered with brass. But behind that cheap door, I sat with Tyler Bennett, sketching on whiteboards and napkins.

“Start lean,” Tyler advised. “Don’t inherit the Brooks’ disease of empire-for-show. Buy distressed assets. Take what they dropped when they fell.”

I listened, not as a subordinate but as a partner. The Brooks family had always told me to smile, to sit quietly in silk, to nod as though my silence meant consent. Tyler spoke to me as though I could shape a world.

So I did.

We bought factories no one wanted, warehouses left empty by the Brooks Group’s collapse, patents gathering dust. We hired engineers the Brooks had underpaid and lawyers who hated them enough to work overtime. Every acquisition was a stone laid in the foundation of Hannah Capital.

The irony was sharp: the money fueling it was the same dowry Adam had sneered at, the “foolish” investment in a house he thought was sentimental. He’d mocked me for buying permanence. Now that permanence bankrolled his destruction.

The city loves a comeback story more than it loves a scandal.

The exposés about Brooks Group faded from front pages, replaced by glossy spreads about me. The Widow Who Rose. From Asylum to Empire. Hannah Moore, the Face of a New Era.

I never corrected the journalists when they called me “widow.” It wasn’t true, but it was useful. Truth is a tool; you shape it until it fits the lock you’re trying to open.

The same outlets that once ran photos of Ella Davis in her pitiful white dresses now plastered my face across their covers. For the first time in my life, the narrative belonged to me.

People whispered about my partnership with Tyler Bennett. Is it business, or is it more? They speculated in comment sections, in hushed gossip at galas.

The truth was simpler and sharper: Tyler was the blade I’d chosen to wield, and I was his.

Late nights in the office, we would sit across from each other, contracts spread like maps of war. He’d push a glass of whiskey toward me, and I’d slide a file back toward him. We never spoke of trust, because trust was fragile. What we had was certainty.

One night, as the city blinked below us, he asked, “Do you ever miss what you lost?”

I thought of Snowball, my mother’s cat. Of my music box, shattered. Of the lasagna that went cold on my anniversary table.

“No,” I said. “Because missing is a kind of chain. And I’ve cut them all.”

For the first time, I saw something almost like admiration in his eyes.

News trickled in about Adam Brooks.

After his release from prison, he wandered the city like a man searching for a script. The Brooks estate was sold, the company dissolved, every account drained. Reporters hounded him until they realized there was no story left—only a ruin in human form.

He spent his days at the cemetery, kneeling before the empty slab with my name carved on it. He scrubbed the stone until his hands blistered, muttering like a priest tending a dead god.

At night he slept in shelters, or not at all. Once, a former colleague saw him standing outside the skyscraper that used to bear the Brooks name, staring at the empty lobby as though he could walk back into a past that had been erased.

To the world, he became a ghost. To me, he became nothing.

Ella did not fade as quietly.

Her trial was a spectacle, every headline dripping with disgust. The Mistress Who Killed a Brother. The Woman Who Wore White While Holding Blood on Her Hands.

She wept in court, begged for sympathy, clutched her swollen belly. But the dash-cam footage was undeniable. The jury deliberated for less than a day.

When the verdict was read—guilty of intentional injury resulting in death—she collapsed in the courtroom, wailing for Adam. He wasn’t there.

Her child was born behind bars. No one knows where the infant went. Some say Adam tried to claim custody but was denied. Others say the baby disappeared into the system, name changed, future untraceable.

I never bothered to find out. Some ghosts aren’t worth chasing.

Two years after the Brooks’ fall, Hannah Capital co-acquired their last remaining asset with Bennett Group. The photo of me shaking Tyler’s hand in the boardroom ran everywhere.

The caption read: From Victim to Visionary.

I stood at the window of our new headquarters—a tower of steel and glass—and looked down at the city that had once caged me.

“This is only the beginning,” I said.

Tyler raised his glass beside me. “Then let’s build higher.”

The final chapter of Adam Brooks’s life intersected mine one last time.

An international business forum in Switzerland invited me as a keynote speaker. The stage was lit, the crowd glittering in suits and diamonds. I wore white again—not the dress of pity Ella had weaponized, but the suit of victory.

As I spoke about resilience, about rebuilding from ash, my eyes swept the crowd. They passed over a figure at the back—thin, hollow, clothes hanging from bones.

Adam.

He stared at me like a man watching an apparition. His lips trembled as though he might call my name.

I did not pause. My gaze slid over him as if he were any other nameless guest.

When I finished, the audience rose in applause. Tyler handed me water with a faint smile, and we descended the stage together.

I didn’t look back.

That night in the hotel, I stood on the balcony, wind sharp against my face. The Alps loomed in the distance, ancient and indifferent.

I thought of the asylum, of the spiked saddle, of the mango porridge. Of Adam’s hand forcing a glass to my lips. Of Ella’s trembling lashes.

And then I thought of the safe house, of Lily’s whispered Godspeed, of Tyler’s case with my new identity, of the first stone I laid for Hannah Capital.

Revenge had not resurrected me. I was not the same woman who had once waited in a red dress for a husband who never came home.

That woman died.

What remained was stronger. Colder. Sharper.

And as I stood above a city that now bowed to my name, I whispered into the night:

“It’s been more than ninety days. And this time, Madam writes the lessons.”

The End.

News

My Brother Claimed I Owed Him Half My Salary “Because Family” — My Response Shut Down… CH2

Part I: Thanksgiving always arrives like a pop quiz in my family—a table-length multiple choice exam graded on performance rather…

Brother mocked me as ‘family failure’—then his fiancée saw my Forbes cover at their engagement…. CH2

Part I: The chandeliers in the Fairmont’s grand ballroom didn’t so much hang as reign. They threw jeweled constellations onto…

I came home for college break and found my stuff in TRASH BAGS on the porch. So, I did THIS… CH2

Part I The plane bucked once over Lake Michigan and then settled into a droning peace that sounded like sleep…

Just Had a Baby, Husband Leaves – ‘Not My Kid! Divorce! Your Affair Revealed!’ In-Laws Are Shocked… CH2

Part I: They say the first cry rearranges your life. A small sound cuts the old world from the new,…

Entitled Woman Tries Suing Man For LEAVING Her Mid Date, Instantly Regrets It… CH2

Part I They call it “happy hour,” but the truth is it’s more a clock than a mood. When the…

My Uncle Left Me a Voicemail ‘They Know Where You Are ’ Minutes Later, a Black Van Followed Me Home”… CH2

Part I My name is Clara Hayes. The girl I was then—twenty-one, overcaffeinated, a commuter student clinging to the scaffolding…

End of content

No more pages to load