Part One:

At exactly seven in the morning, the bedroom door burst open like a courtroom verdict. The thin light at the edges of the blackout curtains glowed dull and winter-white, and the smell of yesterday’s coffee lingered on the nightstand. Rachel had been asleep for barely three hours—the sticky, shallow kind of sleep that clings to your bones. She’d gone down at four, her retinas still burning with the ghost shapes of spreadsheets and dashboards after another marathon for a client who insisted every number be wrung dry of doubt. She was the kind of exhausted that made your heartbeat feel like the slosh of an oar in glue.

“Honey, I swear to God,” Helen Adams said, leaning over the bed so close that Rachel felt the heat of her breath. “It’s seven. Seven! And you’re still asleep. Get up and make me breakfast right now.”

The words were a fire alarm in a quiet church. Rachel’s body jerked upright before her mind registered anything but noise. Her heart surged, crashed, and settled somewhere sharp in her throat. For a fleeting, primitive second she didn’t know where she was—hotel? hospital? Then the familiar hairline crack in the ceiling snagged into focus, the half-unpacked box of books under the window, Mark’s side of the dresser with its lopsided stack of receipts, a crown of loose quarters. Home. Their Denver condo. Her room. The one place that had learned the shape of her sleep. Except it didn’t feel like that anymore; it felt like a borrowed room in a building with paper-thin walls.

“I’m up,” Rachel managed, pushing back the tangle of sheet and comforter. The soft ache of dazzled screen-time throbbed behind her eyes. “Helen, please, I—”

“And the apartment is a mess,” Helen snapped, straightening and striking her palm against the bedroom doorframe like a judge’s gavel. “Your husband will be home for lunch and nothing’s ready. His shirts aren’t even ironed. What have you been doing all this time?”

Playing on the computer. Rachel could hear the phrase before Helen said it, hear it the way you hear rain inside the walls. Playing. As if the invoices Rachel sent and the ACH deposits that landed like clockwork, three times what Mark earned pushing paper across a desk, were a magic trick instead of a career. As if sixteen hours at a keyboard were the same as killing time on a phone.

Rachel swallowed, the motion sandpaper. “I worked until four,” she said. “I’ve got three clients on West Coast time, and one in Tokyo. I can start coffee in a second.”

“Coffee? Frank needs a hot breakfast,” Helen said, scoffing. “Eggs, bacon, biscuits. Not that rabbit food you keep pushing on us. He’s not a rabbit.” She leaned in again, eyes bright with an indignation that had no shape except hunger and habit. “And a woman—an actual woman—gets up before her family. She doesn’t sleep till noon.”

Seven o’clock wasn’t noon. That lived like a small, useless fact in Rachel’s mouth while everything else inside her tried to stay very still. This was week three. The visit that had been “a few days” after Mark’s dad’s blood pressure scare; the visit that had become “until we find them something” and then just… them. Their shoes by the door. Their voices ricocheting down the hallway. Their breath in her kitchen. The two-bedroom that had once felt grown-up now felt claustrophobic, its corners colonized by the clatter of other people’s expectations.

Rachel stepped out of bed. The cushions of her brain sloshed. She wanted to say Get out of my room. She wanted to say Stop talking to me like I’m a broken appliance. She wanted to say If I measure my worth in dollars, I win, and if I measure it in hours worked, I still win, and if I measure it in kindness… well, I’m losing, but not for lack of trying. She said none of it. She braided her hair back with the automatic, careful movements that kept her hands from shaking.

“Fine,” she said. “I’ll—”

Helen had already turned, the judgment rendered, the conversation ended. She stormed out, calling over her shoulder: “And open those curtains. It smells like sleep in here.”

The door banged. The apartment came alive under Helen’s hands. A drawer yanked open, slammed shut. Curtains ripped to the sides as if light were something you forced. A chair dragged screeching across hardwood. The apartment was not messy—Rachel kept it neat because chaos braided itself easily into her mind and made knots—but Helen made a point of finding what wasn’t there. Dust on shelves that didn’t have any. Fingerprints on glass only she could see. It wasn’t cleaning; it was theater. It had an audience of one—Rachel—and it performed a thesis: You fail, and I fix.

“What’s going on out there?” Frank’s voice rose from the kitchen, thick with sleep, the consonants heavy. “And where’s breakfast? A man can’t live on coffee and salads.”

Rachel’s stomach made a small, treacherous lurch at the word salads. She liked grilled fish. Vegetables. Food that didn’t cling to your fingers with grease. Frank liked biscuits drowning in butter, bacon so crisp it shattered, eggs whose yolks ran reckless across plates. The morning after they’d arrived, she’d made oatmeal with toasted pecans and blueberries and a drizzle of maple syrup she’d bought from a farmer’s market stall with a girl in mittens. Frank had pushed it away, offended. “Baby food,” he’d said, as if she’d brought him a bowl of paste.

Rachel dressed quickly: soft jeans, a long-sleeve tee, the sweatshirt with the frayed cuffs. The apartment was a battlefield; the uniform was armor you could move in. She opened the door and stepped into the corridor, the living room stretched before her like a stage. Helen was in the middle of it, hands on hips, the triumph of a conquering general bright on her face. Frank sprawled at the kitchen table, hair rumpled, jaw shadowed, a man who expected the world to appear plated and salted before him because it always had.

“Enough,” Rachel said.

The word surprised her with how easily it came out, clean as a pebble skipping across water. It cut through Helen’s running monologue about dust, about under-raised women, about the tragedy of a son married to a person who didn’t know the difference between a simmer and a boil. Everything stilled. Even the clock on the wall seemed to hold its breath between ticks.

“You have thirty minutes,” Rachel said. “Pack your things and leave my home.”

Helen blinked, slow, like a cat deciding whether to pretend it hadn’t been startled. A pulse flickered at her throat. Then her mouth curled. “Your home?” she said, tone dripping. “Don’t flatter yourself, Rachel. This is Mark’s apartment. You don’t get to throw me out of my son’s place. You are nothing here.”

Frank made a noise that was approval and phlegm at the same time. “Exactly,” he said. “Don’t forget whose name is on the family.”

Heat crawled up Rachel’s neck. She stepped forward, voice low but steady. “This apartment was bought with our savings. We’re still paying the mortgage—together. Your son couldn’t have done it alone. You didn’t give us a dollar. So don’t act like this is some gift you handed down from a throne. You are guests.” She swallowed, her hands steady at her sides because she told them to be. “Nothing more.”

Helen’s face flushed a furious red, indignation that felt as practiced as prayer. “All you think about is money,” she snapped. “Ungrateful. Selfish.”

“I think about fairness,” Rachel said, softer, dangerous because the softness didn’t hide the steel. “And I think about being able to sleep in my own home after working all night without being screamed at for not ironing shirts.”

Silence came down like a lid. Frank shifted, looked away, his fight instinct suddenly less certain without a script. Helen’s chest rose and fell, rose and fell, loading another volley that would be louder, meaner, landing exactly where it would bruise longest. Rachel could feel the shape of the next hour if she stayed—how Helen would escalate, how Frank would mutter, how the morning would tangle into an afternoon of explanations she would offer and they would refuse to hear. Mark wasn’t here. He’d be at the office, head down between his monitors, unreachable, or worse, unreachable by choice. Facing them alone was a rigged trial; they had already picked a jury.

Rachel turned away. Not retreat. Strategy.

She went to the bedroom, collected her laptop bag, slid her phone into the front pocket. She tied her hair tighter, wiped the remains of last night’s mascara from under her eyes with the heel of her thumb. At the door, she hesitated—out of habit more than anything—then stepped into the hall without looking back. The door closed behind her with a solid, satisfying click. It wasn’t a slam. It was a period.

The Denver morning slapped her cheeks bright. The city in winter is a particular thing: air that tastes like metal, sun that looks warm and is not, mountains studding the horizon like teeth. Rachel walked fast because her legs asked her to. If she could outpace the echo of their voices, she could think. If she could think, she could work. And work was the one thing that had never abandoned her.

She found a corner booth at a cafe she liked on 17th, the kind of place with little succulents in concrete pots and a chalkboard menu with handwriting so careful it made you trust the pastry case. The espresso machine hissed and sighed like an animal at rest. Rachel ordered a black coffee and a hard-boiled egg and watched her hands as she paid, willing them not to tremble. They did not, not until she slid into the booth and opened her laptop and the glowing rectangle reminded her of all the ways she knew how to be competent.

For thirty minutes, she was. She answered emails like a surgeon suturing clean lines. She reviewed a report and marked three trends the client had missed. She drafted a proposal, bolded the right words, cut the wrong ones. The tightness in her chest eased the way a fist unclenches after holding onto a rail too long.

Her phone buzzed. She ignored it. It buzzed again. And again. The persistent hum of insistence. Rachel sipped her coffee and counted to five and set her jaw against the way her mind wanted to look. The phone buzzed again. She turned it face-up.

Facebook Messenger filled the screen with blue and gray and bile. Helen’s name at the top, her profile picture a frozen smile from a cruise ship deck, sun burning off water behind her. The messages stacked like an avalanche.

Lazy. Worthless. Disgrace. Not a real woman. Not a real job. If you had any decency. If you had any shame. She scrolled. The words sharpened, then sickened, crossed a line she hadn’t quite believed Helen would cross, even after everything. You’ll regret the day you crossed me. Maybe sooner than you think.

A cold disgust wiped across Rachel’s skin. Not fear—that was important to note, even to herself—but a kind of revulsion that made her want to scrub. It was one thing to spit cruelty in the heat of a room, to let sound carry it away. It was another to type it and hit send and leave it sitting, deliberate as a nail. Rachel felt the fine tremor in her fingers return and forced it still by giving her hands a job.

She took screenshots. All of them. Every insult. Every threat. She created a folder, named it with the date and the time because the world respects file names even when it won’t respect a person. She saved them carefully and checked that they were there and then blocked Helen. The silence that followed was instant, a window slammed against a storm.

Rachel set the phone face down and leaned back in the booth. The room around her held—cups clinking, low conversations, milk foaming—like normal life had decided not to notice that someone had told her she wasn’t worth peace. Her coffee had cooled. She drank it anyway, bitter and good and grounding.

This is not a bad morning, she thought, feeling the sentence anchor itself. This is my life, as long as I let it be. She unlocked her phone. Attachments. Helen’s words lined up neat and damning. She typed slowly, the way you do when you are tired of ever being accused of hysteria.

I’m at the cafe downtown. We need to talk. Come here tonight.

She sent it to Mark and set the phone down again and let the weight of that simple act land. She had kept the peace like an unpaid job for three weeks. She had bitten her tongue until it bled. She had told herself that endurance could be a form of love. But something had shifted this morning, at seven a.m., with the word breakfast knifing the air above her head. A crack had widened into a fault line. The earthquake wasn’t sudden; it had been building pressure all along. All she had done was step back far enough to see the shape of it.

Outside, Denver kept being Denver. Inside, Rachel watched the screen saver bounce lazy across her laptop and let her breathing settle. She would hold, for now. She would be civil and precise and clear. She would make coffee and make a case. She would ask for the bare minimum: a home that did not feel like a punishment. She would ask Mark to choose respect over convenience. She would see what he did when asked.

Later—she could already tell—the night would bring something hard and final. But for a few hours she let the cafe’s warmth wrap her and opened another document and typed because she knew how. The rhythm of it steadied her the way a metronome steadies a musician on a stage where the lights are too bright.

At six o’clock exactly, the bell over the door would chime, and Mark would walk in, jaw set, eyes scanning, already annoyed by the fact of being summoned. But that was later. For now, Rachel built the scaffolding of her life in a quiet booth, watched the steam lift off other people’s cups, and pressed her palms against the cool of the mug, holding onto a small, ordinary heat that felt, for the first time all day, like hers.

Part Two:

The bell over the cafe door chimed at six like a cue in a play she hadn’t wanted to audition for. Rachel looked up from the cold rim of her coffee and saw Mark in the entryway, wind pushing against him as if the city itself were reluctant to let him inside. He scanned the room, found her in the corner booth, and his face arranged itself into a shape that wasn’t neutral. He wasn’t a man arriving to understand. He was a man arriving to manage.

He slid into the booth across from her without a hello, the vinyl seat sighing under him. Up close, he looked like a different species of tired—creased shirt collar, five-o’clock shadow shading into six-thirty, eyes that had learned to keep their own counsel. He put his phone face-down between them like a mediator. “So,” he said, exhale already sculpted into a complaint, “what did you and Mom fight about this time?”

It wasn’t a question so much as a sentencing. Rachel sat straighter and folded her hands on the table, the way she did before a difficult client call. “This isn’t just another fight,” she said. “I want your parents to leave. Tonight.”

He leaned back, arms crossing. The gesture had become a language inside their marriage—defensive when he felt cornered, dismissive when he wanted to make her feel small. “You’re exaggerating,” he said, tone practiced. “Mom’s blood pressure has been all over the place. She’s not herself. They don’t mean everything they say. Dad’s stressed. You know that. And now you’re pushing me to throw them out? Do you want me to just abandon them?”

Abandon. The word sat in the middle of the table like a loaded fork. People like Helen weaponized it because it worked on sons like Mark. Rachel let it sit. “I’m not asking you to abandon them,” she said carefully. “I’m asking you to set a boundary. They’ve insulted me in my own home. They burst into our bedroom at seven a.m. screaming for breakfast. I can’t live like that. If you want to support them, rent them a place. Visit. Bring groceries. But they can’t stay with us anymore.”

Mark’s mouth flattened into a line so thin it could cut. He leaned forward. “This is my home too,” he said. “I have just as much right as you do to invite my parents to stay. You don’t get to dictate who I let through that door.”

Something inside her—something that had been white-knuckled and earnest and forever negotiating—let go. She felt it as a small, astonishing mercy. When she spoke, her voice didn’t rise. It steadied.

“Then listen to me,” she said. “If they don’t leave, I will. And if I leave, I won’t be coming back. I will file for divorce.”

The word turned heads at neighboring tables even though she hadn’t raised her voice. Mark blinked. For a second, a flicker of something—hurt? panic?—crossed his face like a cloud’s shadow. He swallowed it. “Are you serious right now?” he said, pitching his voice low and paternal. “You’re making me choose between my family and my wife. Do you even hear yourself?”

“You’re wrong,” she said. “I’m asking you to respect me enough to not force me into a hostile environment every day. I’m asking for the bare minimum to feel safe in my home. If you can’t give me that, what exactly do I have left in this marriage?”

He stared. The silence mushroomed between them, filling odd corners: the sugar caddy, the napkin holder with the chipped corner, the single flower in a bottle on the table behind him. He wasn’t weighing her words; she could see it now with a bleak clarity that felt almost freeing. He was calculating how to bend her back into shape.

He tried a different angle. “Look,” he said, softening the edges of his voice the way he did with clients he wanted to keep without raising their rates. “Let’s not blow this up. They’ll only stay another week. Maybe less. Mom needs to get back on her feet. Dad will calm down. Can’t you just hold on a little longer?”

Rachel had learned many things in the last three weeks. Chief among them: with people like Helen and Frank, there was always another week. “No,” she said. “I’m leaving tomorrow. I’ll come back for my things later.”

“You’re really going to walk out over this.” Disbelief sat poorly on him, as if he’d borrowed it from someone whose face could carry it better.

“Yes,” she said. “Because this isn’t about them anymore. It’s about you. You refuse to set boundaries. You refuse to protect me in my own home. That means I have to protect myself.”

He leaned in, his voice dropping, the way someone lowers their tone to sound reasonable when they’re about to be anything but. “So what? You’re going to throw away our marriage over a couple of arguments with my parents? That’s crazy.”

“It’s not a couple of arguments,” she said. “It’s a pattern. Three weeks of humiliation. Three weeks of silence from you. I won’t keep living like this.” She paused. “And don’t forget: the apartment is marital property. If you want to keep living there, you’re responsible for half the mortgage. You can’t pretend it’s yours alone.”

That landed. His jaw ticked. “So you’re already talking about dividing assets,” he said, bitterness salted across the words.

“I have to,” she said, gentler than he deserved, because kindness was muscle memory and not a moral verdict. “I can see where this is headed.”

He rubbed his forehead with the heel of his hand. “We can figure this out,” he said, as if saying it could make the world cooperate.

“I did figure it out,” Rachel said. “Tomorrow, I’m moving out. I’m not staying in that apartment with them one more night.”

For a moment, she thought he might reach for her hand, might say he was sorry, might call his parents and tell them to pack. He didn’t. He looked down at his phone, tapped the screen as if consulting a schedule that could save him, then looked up, face closing. “You’re being dramatic,” he said.

The word made her want to laugh. Drama was what happened when emotion had nowhere practical to go. She was being specific. “Think about what I said,” she told him, sliding out of the booth. “Either they leave or I do. If I walk out, it’s not just for tonight. It’s for good.”

The bell chimed again as she left. The air outside was knife-bright. She walked to the corner and stood there for a minute, watching cars string their taillights down 17th like a red ribbon. Inside her, a quiet rose something like relief and something like grief, two birds trying to share the same air.

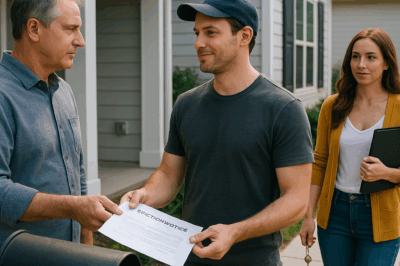

She booked an extended-stay studio ten blocks from the condo and texted the address to herself, then to Mark, then to no one. She returned to the apartment like a firefighter—calm, efficient, unwilling to die in someone else’s fire. Helen was in the living room, folding and refolding a dish towel with punitive precision. Frank flipped channels with the angry restlessness of a man convinced television owed him something it kept refusing to deliver.

“I’m packing a bag,” Rachel said, as neutrally as if she were picking up dry cleaning. “Mark has the address.”

Helen smirked without looking up. “Running away,” she said.

“No,” Rachel said, and surprised herself by smiling. “Leaving.”

In the bedroom she moved through the familiar steps: open the closet, choose the things that make you feel most like yourself, fill the bag you’ve carried to airports and new clients and your own beginnings. Laptop. Chargers. A sweater that smelled faintly of the laundry soap her mother used when she was a kid. She didn’t linger. Lingering is for people who aren’t sure. She was sure.

At the door, she paused. “Goodnight,” she said. It was not generous. It was a boundary in lowercase letters.

“Ungrateful,” Helen muttered, as if the word were a diagnosis she’d been waiting to deliver to justify her treatment plan.

Rachel closed the door gently behind her. The hallway was quiet enough to hear her own breathing. The elevator yawned open like a mouth. In the small mirror above the buttons she caught a glimpse of her face. She looked like someone who had just taken her hand off a hot stove and was waiting for the pain to register. The elevator doors closed. It didn’t come.

The studio was not much. It had the smell of new paint and an old building—the layered scent of other lives. The kitchenette’s mini-fridge hummed like a polite insect. The bed was too firm. The lamp cast a circle of light that looked like a stage cue. Rachel set her bag on the dresser and stood in the center of the room, listening. There were no voices. No demands. No slamming doors. The silence was so unfamiliar it felt like a risk.

She texted Mark: I moved out. I’ll come for the rest of my things this weekend.

Three dots bubbled, hesitated, vanished. Five minutes later, the phone buzzed.

Mark: This is insane. They’re staying a week. You’re making this bigger than it is.

A second message followed immediately: We’ll talk tomorrow. Don’t do anything stupid.

Stupid had done so much heavy lifting in his vocabulary over the last year—stupid meaning something he hadn’t sanctioned. Rachel typed and deleted and typed again, then left it at: I’ll see you Saturday to collect my things. Please be civil.

She put the phone face-down and opened her laptop. The empty email composed itself on the screen, cursor blinking like a small heartbeat. Subject: Consultation—Family Law. She didn’t over-explain. She attached nothing. She asked for a call. She closed the laptop and lay back on the bed that was too firm and stared at the ceiling. The room’s quiet settled around her like a decision.

Sleep found her the way good luck finds people who have stopped waiting to be chosen by it—late, but gentle. In the morning, she made coffee in a tiny drip machine and felt the smell of it scout the corners and declare them habitable. She answered emails. She scheduled three client calls. She opened her bank app and did the arithmetic of independence. The numbers lined up cleanly, comforting as a row of soldiers who know their orders.

By noon she’d heard from two attorneys. She chose the one who didn’t sound curious about gossip and did sound particular about paperwork. “We’ll move deliberately,” the attorney said on the phone, her voice calm in a way that made Rachel unclench her jaw. “You’re safe. You have options. We’ll document everything. We’ll file when you’re ready.”

“I’m ready,” Rachel said, and the words didn’t wobble.

“You’ll still be on the mortgage for now,” the attorney said, practical, kind. “We’ll address the property as part of settlement, but remember: banks don’t care about divorces. They care about payments.”

“I know,” Rachel said. It was a sentence of dread and of agency.

She texted Mark around four to ask what time he’d be home Saturday so she could come by without turning it into a show. The reply was terse: Afternoon. Don’t touch my stuff.

“Always a gentleman,” she told the room. It didn’t answer back. That was the point.

Saturday, she let herself into the condo with a key that would need to be relinquished eventually but not yet. The apartment looked the same and not, as if it had shrugged into a new posture. Helen’s voice came from the kitchen, pitched slightly higher now that the audience she preferred had stopped clapping. Frank was nowhere, probably grocery shopping for bacon. Mark stood by the sink with a dish towel he wasn’t using. His mouth worked as if the words he wanted were gritty.

Rachel walked past Helen without stopping. “I’m going to pack,” she said.

“Take your rabbit food and leave the spices,” Helen said.

“They’re mine,” Rachel said without heat. “I paid for them.”

Helen made a sound like a snort run through a garbage disposal. Mark lifted a hand. “Let’s not—”

“Let’s not,” Rachel echoed, and the small mirror of his phrase made something in his eyes harden. She spent the next two hours moving through rooms like a quiet storm. Books. Clothes. The framed photo of her and her sister at the trailhead in Boulder, sunburnt and grinning. The mug with the chipped rim she loved because it kept conversations honest—no one expects perfection from a vessel that shows its cracks.

In the bedroom, she paused by the window and looked out over the city. Denver shimmered winter-blue. She thought of all the mornings she’d stood here in a robe, coffee in one hand and laptop in the other, feeling capable and grateful and tired in a way that felt like a small price to pay for a life she had chosen. She thought of three weeks that had rewritten that feeling into dread. Then she closed the box and taped it shut.

At the door, Mark hovered. “We can still fix this,” he said, as if the very act of declaring it could make it true.

“You can,” she said. “You can ask them to leave. You can apologize. You can respect me.” She lifted a box. “But you won’t.”

“You’re so sure?” he said, angry at her certainty because it reflected his own.

“Yes,” she said. “I am.”

She carried the last box to the elevator. The hallway seemed to breathe easier with each step she took. In the lobby, she passed a couple arguing quietly about paint swatches. Domestic doomsdays came in all sizes. She loaded the car, closed the trunk, and stood for a second with her hands on the cool metal, letting the reality of the weight shift into her muscles. She got in, started the engine, and drove back to the studio that still smelled faintly of new beginnings and lemon cleanser.

The days that followed were not cinematic. They were paperwork. They were conversations with her attorney. They were emails to clients that said nothing about divorce and everything about deliverables. They were sleeping through the night and waking without an alarm and realizing the absence of yelling had its own sound.

Helen, thwarted in person, pivoted to the internet’s hallway. Rachel didn’t read the messages directly anymore; she set filters and rules and made folders with names like DOCUMENTATION and EVIDENCE and NOT URGENT. She took screenshots and sent them to her attorney, who filed them under words that had more force in a courtroom than they had in a kitchen. She blocked numbers and didn’t feel like a coward. She felt like someone who had finally learned how to lock a door.

Mark, at first, paid his half of the mortgage on time, the way you take vitamins you don’t believe in because you’ve been told they matter. He sent short texts about logistics that read like receipts. Then, slowly, the pattern frayed. A late payment. An email from the bank that said phrases like “notice” and “assess.” Rachel paid her half like clockwork and watched the other half slide into the kind of story she had never wanted to tell about the person she’d once promised to trust.

Her attorney’s voice, steady as always, on the phone: “We’ll request an order clarifying responsibility. But remember, the bank just wants its money. We will adjust in the settlement.”

Rachel ran the numbers again. She could cover the arrears if she had to. She could buy peace the way you buy a coat in February—late, but still useful. She started collecting documents like a magpie: pay stubs, bank statements, screenshots of messages where she had reminded and he had deflected. She put them in a folder labeled WINTER. Not because it was, although it was, but because she knew seasons turn.

At night, sometimes, she missed the condo, but not the way she had expected. She didn’t miss the square footage or the view. She missed the way it had felt to think something was truly shared. She missed the silly dance they’d done in the kitchen at two a.m. the night they got the keys. She missed a version of Mark that had been possible for only as long as no one tested his loyalties. Missing was not a reason to go back. It was a way to acknowledge that you are not made of stone and still choose not to drown.

On a Sunday, she walked the park with a coffee and watched a dog chase a ball with such single-minded joy she laughed aloud. The sound startled her; it had been a while since laughter had arrived without needing to ask if it was allowed. She went home—hers—and cooked fish with lemon and roasted broccoli, and ate it at a small table by a window that looked at a brick wall and a sliver of sky. It tasted like food you make for someone you love, and for the first time in months, that someone was herself.

In the third week after she’d left, an envelope arrived at her studio, stamped with the kind of seriousness that makes you hold your breath before you open it. She slit it with a butter knife. The bank’s letter was crisp, impersonal, wearing its concern like a well-pressed suit: past due, remedies, options, timelines. Rachel put it on the counter, next to the lemon she’d zested the night before, and stared at both as if they were in conversation.

“Okay,” she said to the room, to the lemon, to the letter, to herself. “Okay.”

She picked up her phone and called the bank. The hold music was a tinny version of a song she loved in college, now turned into an elevator joke. When the loan officer came on the line, she spoke in the clear, even sentences she saved for meetings where results mattered.

“I’m calling about the mortgage on the unit on Speer,” she said. “I’m one of the borrowers. I’d like to talk about bringing the loan current and restructuring so it’s only in my name.”

There was a pause, the sound of someone turning to the right tab. “We usually require both parties,” the officer began.

“I understand,” Rachel said. “But the other party has been delinquent. I can demonstrate my income and my payment history. Foreclosure would be in no one’s best interest. I’d like to keep this simple for both of us.”

The officer hesitated, then asked for documents. Rachel smiled into the receiver. She had them ready, labeled, scanned, dated—the footprint of a woman who knew how to outrun a fire. “I’ll email them this afternoon,” she said.

After she hung up, she poured herself a glass of water and stood at the window and looked at the sliver of sky. It was exactly the color of a decision made at last.

The line had been drawn in a cafe at six o’clock, but it extended here, into a life that would be mostly paperwork and sometimes startling joy and always hers. She didn’t know yet that in a few months she would stand in the condo alone with a new set of keys warm in her palm, the rooms echoing not with judgment but with possibility. She didn’t know that a man with steady eyes would hand her a cup of coffee at a networking event and ask about her favorite hikes, and that an ordinary question could be the beginning of a future. What she knew was this: she had said enough, and she had meant it, and the world had not ended. It had opened.

Outside, a siren rose and fell. Somewhere, someone yelled for breakfast. Inside, Rachel turned back to her laptop, opened a folder called WINTER, and started to build a bridge out of facts.

Part Three:

The first time Rachel sat across from the bank’s loan officer, she felt like she was visiting a principal’s office for a crime she hadn’t committed. The conference room was all glass and gray, the table polished into a mirror that kept reflecting back a woman who looked composed enough to pass inspection. The loan officer—Kara—wore a blazer the color of wet sidewalk and an expression that said she’d seen everything twice already.

“So,” Kara said, folding her hands. “You want to bring the loan current and restructure to remove the co-borrower.”

Rachel opened her laptop and clicked on a folder called WINTER, then on another called SPEER. She slid a neat stack of paper across the table like a dealer in a quiet casino. “Payment history for the last twelve months,” she said. “My pay stubs, tax returns, bank balances. Correspondence with the co-borrower requesting he cure his delinquency. Proof I’ve paid my half on time every month.”

Kara scanned the first page, then the next. Her eyes ticked left to right with the mechanical mercy of due diligence. “We typically require both signatories to approve a modification,” she said, the words landing with the dull weight of policy.

Rachel nodded. “I understand. But foreclosure is costly. I’m offering to cure the arrears and assume the full responsibility going forward. If we can’t restructure, I will still bring the account current today.” She let the last sentence sit. A bank is a creature that feeds on certainty. She had come to put food in its mouth.

Kara rested her pen. “Your income is… strong,” she said, and the tiny pause before the adjective was the verbal equivalent of raising an eyebrow politely. “We’ll need underwriting’s blessing.”

“Of course,” Rachel said. “I’ll wait.”

While Kara stepped out, Rachel watched a pair of seagulls swoop and argue on the window ledge, their bodies reflecting in the glass like punctuation marks. She felt oddly calm. It wasn’t the false calm of shock; it was the steadiness that arrives when you stop trying to convince the tide to change direction and start building a pier.

Kara returned with a different energy—still professional, but less theoretical. “Underwriting wants one more month of bank statements and a letter of explanation regarding the divorce,” she said, as if asking for napkins at a picnic.

Rachel produced the statements. As for the letter, she had it drafted, bullet-pointed, and saved as a PDF. “The divorce is uncontested as to the apartment’s current use,” she summarized. “We’re both on title and the note. He’s living there. I’m proposing to remove him from both by curing arrears and refinancing into my sole name. I will indemnify.”

Kara blinked and, for the first time, smiled. “You don’t work in lending, do you?”

“Digital strategy,” Rachel said. “But I read.”

They scheduled a follow-up for a week out. Rachel left the bank with a to-do list that felt blessedly finite. Out on the street, the wind lifted her hair and tried to rebraid it. She let it try. She bought herself a sandwich and ate it sitting on a low wall in the thin winter sun, and for once, the food tasted like food and not like a delay tactic.

The warning letter turned into a Notice of Default with all its italicized grandeur. The tone grew stern, as if the bank had put on a better suit. Mark texted her a photo of the envelope with the caption: This is your fault.

She typed and deleted and typed again. In the end, she sent a screenshot of her cleared half-payments and the email from the bank acknowledging receipt, along with: I’ve already met with them to cure. Please stop deflecting.

He didn’t respond. It felt less like triumph and more like moving through a fog that refused to admit the existence of streetlights.

Her attorney filed motions that sounded like arguments and felt like hard-won air. “We’ll keep the property split fifty/fifty on paper while you negotiate with the bank,” she said. “If you’re able to assume and refinance to your sole name, we’ll incorporate a buyout. His delinquency will compress that number.”

“Compress,” Rachel repeated, tasting the word. It felt like a polite way to say shrink without adding cruelty. She didn’t want cruelty. She wanted clean lines.

At the end of the month, she met Kara again. Underwriting had come around. “You can cure the arrears,” Kara said, pushing across a form with boxes that had never anticipated a human life would have to fit inside them. “We’ll initiate a substitution and release once the refinance is approved. You’ll carry the note alone. He’ll be removed from title at closing.”

Rachel signed where the stickers told her to, each signature a stroke that felt less like surrender and more like an answer. She wired the arrears—an amount that stung but didn’t hobble—and left with a timeline and a checklist. Banks aren’t sentimental, but they do love a good plan. So did she.

Mark found out the way men like Mark always do: not because he was tending the garden, but because the sprinkler turned on. He called, then texted when she didn’t pick up. YOU DID THIS BEHIND MY BACK. She texted back: I did it above board. I cured arrears to protect my credit and the property. We’ll settle the equity as part of the divorce.

He replied with a long paragraph that used the word betrayal twice and my parents three times. She sent it to her attorney, who replied with a thumbs-up emoji that made Rachel laugh for the first time that week.

Helen, in the meantime, pivoted from insults to mythmaking. In her version of the story—no doubt told in the lobbies of medical offices and the floral aisles of grocery stores—Rachel had stolen the family home. The fact that Helen’s name was on neither deed nor note was immaterial to the theatre of grievance. Rachel tried not to care. On bad days, she failed and cared anyway. On good days, she remembered that paperwork is a stronger religion than gossip.

The refinance process stretched the way an old elastic stretches—functional, a little creaky, reliable enough if you didn’t tug too hard. Appraisal, inspection, payoffs, two more letters from underwriting that asked the same questions in slightly different fonts. Through it all, Rachel moved forward with the purposeful grace of a person who had learned the difference between a barrier and a speed bump.

On a Friday afternoon that smelled like snow, she sat in a title office and signed the stack that would hand her the keys in a cleaner way than the day she’d first walked across that threshold with Mark. The closer—a woman with immaculate nails and a calm affect—slid the deed across the table for the final signatures.

“This next one removes the co-owner from title,” the closer said. “He’s executed a quitclaim deed as part of your settlement; we’re recording simultaneously.”

Rachel let herself breathe not as a metaphor but as an act: in, out, like she was lifting a weight she’d trained for. Pen down, pen up. Her signature sat there like a flourish she hadn’t earned but had fought for anyway.

When it was done, the closer gathered the papers with the efficient tenderness of a nurse making up a bed. “Congratulations,” she said. “You’re the owner.”

Rachel nodded and surprised herself by blinking hard. “Thank you.”

She drove to the condo alone. In the elevator, she held the new keys the way people hold seashells collected from beaches that demanded effort to reach. The door to the unit opened with a sound that, finally, was just a door opening. No raised voices. No pointed sighs. No invisible ledger of resentments being updated against her will.

The rooms were quiet. Mark had moved out two weeks before as part of the agreed settlement, a staggered choreography of boxes and social media posts that made very careful use of the words new chapter. Helen and Frank had left before that, pulled along by the gravity of a son who had mistaken stubbornness for loyalty and, when faced with paperwork, learned to tell time by court dates.

She walked from room to room, touching nothing and everything. The indentation on the carpet where the couch had been. The faint outline on the wall where a sun-faded picture frame had hung. The kitchen counter, wiped so clean she could see the overhead light reflected, a little milky at the edges from years of wiping and spilling and laughing and fighting. She ran her hand along it. It made a sound like turning a page.

In the bedroom, she stood by the window and looked out at the city that had held all of it: the good, the bad, the time she had whispered I do at a courthouse with a bouquet from the corner store, the time she had said enough in a cafe with a cold coffee and a folder of screenshots, the time she had called a bank and asked it to believe she could keep a promise that someone else had broken. The mountains glowed bone-white against a cold blue sky. Buildings caught the low sun and threw it back.

Her phone buzzed. A notification—the title company confirming recording. Another—her attorney: You’re done. Own it, literally and otherwise. Proud of you.

Rachel typed: Thank you. Then put the phone down. She took a slow lap around the living room and found herself laughing, soft and a little wild, at nothing particular, at everything.

She opened the windows and let the winter air muscle its way in. She lit a candle that smelled like cedar and new pencils. She took off her shoes and set them neatly by the door. She leaned against the counter and ate an apple with the ravenous contentment of a person who has been fed poorly for too long and suddenly remembers how to want.

Later, she met with her attorney one last time to initial and sign and notarize and nod. Mark had filed a complaint—something about unjust enrichment that read like a tantrum written in legalese. It was dismissed swiftly. The judge acknowledged what Rachel already knew: she had paid what the bank was owed and, in return, taken what she could hold without hurting anyone else.

After the hearing, Rachel sat in her car in the courthouse parking lot and called her sister. They didn’t talk about the past as if it still owned them. They talked about what mattered, which was that Rachel had navigated out of a maze that punished anyone who wanted to do something as radical as sleeping till seven without being called lazy.

“Come up to Boulder this weekend,” her sister said. “We’ll hike the Mesa Trail. You can yell at the mountains if you need to.”

“I don’t,” Rachel said, surprised to find it true. “But I’ll come anyway.”

That night, she walked through the condo with a notebook and made a list that looked like a new language. Paint: warm white. Couch: something you can nap on without apologizing. Plants: three, tall, let them reach. Dishes: not the ones you bought because they were on sale when you thought adulthood was a puzzle solved by stacking coupons just right. Art: things you like for reasons you can’t articulate, which is allowed.

It wasn’t about erasing what had been. It was about insisting that the next version would be made by a person who had stopped apologizing for being whole.

Work thrummed like a machine she’d tuned to her pitch. Clients, sensing a woman who did not wobble, gave her bigger projects with more zeroes and less drama. She put money aside with a neatness that felt like an act of love for the future. She slept. She woke naturally, without someone else’s voice wrenching her into usefulness. She cooked food that pleased her and no one said the word rabbit like an insult.

On a wet spring evening in May, she went to a networking event because discipline isn’t always about saying no; sometimes it’s about showing up. She wore a dress that made her feel like someone who could accept a compliment without qualifying it. The room’s chatter had the nervous energy of opportunists and the tethered calm of people who are good at their jobs.

That’s when she met Daniel Cooper. It didn’t feel like a meet-cute; it felt like two professionals exchanging names near a cheese platter. He worked at a local tech firm, project manager, precise in his language without being precious, the kind of person who could explain a complex timeline without watching your eyes to see if you were impressed.

“Favorite hikes?” he asked, gesturing with his drink toward a poster of Boulder trails someone had put up as if to remind Denver that other cities had mountains too.

“Mesa on a weekday,” she said, “Royal Arch if I’m in the mood to earn my lunch.”

“South Boulder Peak,” he replied. “But only if the air’s clear enough to see forever.”

She smiled. “I like the way you put that.”

They talked about work in the kind of shorthand people in the same ecosystem use when they recognize another member of their species. He didn’t interrupt. He didn’t explain her job back to her with fewer syllables. When she mentioned that she consulted from home, he didn’t say must be nice. He said, “No commute—that’s a superpower. But it must be hard to turn off.”

“It was,” she said, thinking of a bedroom door at seven a.m. and a voice like a siren. “It’s better now.”

When he asked for her number, he didn’t pretend it was for a professional reason. “I’d like to see you again,” he said, direct, careful with the weight of the ask.

She gave him her number because she wanted to and not because she felt she should. An uncomplicated sentence that had taken years to learn.

They started with coffee, then a walk that became dinner, then a movie night that became a running joke about who fell asleep first (her) and who always pretended not to (him). He listened. He asked questions that didn’t pry. When she told him about the bank, he didn’t say wow as if she’d survived a tornado. He said, “You built something. That’s hard and good.”

She didn’t rush. She had learned there’s no prize for arriving first to a place you’re not sure you want to live. She learned the cadence of him—how he sent a good-morning text like a person remembering to water a plant, how he offered to help without making her feel incapable, how he was quiet when quiet was the right answer.

By September, the condo felt less like a crime scene and more like a blueprint. Plants stretched toward the windows. The couch had a throw blanket perpetually half-askew. The kitchen smelled like lemon and garlic and the occasional celebratory takeout. The winter folder on her laptop had been archived. A new folder—FALL—held plans for nothing more perilous than a weekend in Crested Butte.

One night, as they stood in the living room surrounded by half-unpacked moving boxes—his books, his favorite skillet, a painting he’d picked up from a gallery that didn’t look like it sold yoga mats in the back—Daniel set a box down and looked at her the way people look at viewlines they’ve hiked an hour to find.

“You sure?” he asked, simple as a weather report, serious as a loan document.

Rachel looked around. The walls didn’t remember shouting anymore. They remembered the smack of tape on cardboard, the clatter of plates, the meaningful silence of two people who didn’t need to narrate their competence. “I’m sure,” she said.

He exhaled, smiling the way men smile when what they want lines up with what they’re ready to carry. He crossed the room and kissed her, a kiss that tasted like the pasta they’d made and something else—quiet, maybe. Or peace. Or the knowledge that second beginnings can be less about correcting a past and more about choosing a present.

Later, sitting on the couch amid the chaos of becoming, she reached for his hand and found it easily. The room hummed with possibility and the mundane joy of deciding where to put the bookshelves (left wall, obviously). Rachel felt the city’s night press gently at the windows like a cat saying hello.

She thought, without the drama of trumpet blasts, of seven a.m. and breakfast and the voice that had tried to draft her into a life where her worth was measured in servitude and silence. Then she thought of a cafe at six and a line drawn with a cold cup in front of her and a folder of screenshots and a spine she’d finally decided to listen to.

This wasn’t the end. Endings carry a finality that life rarely honors. But it was the close of a chapter written in steady handwriting. The next one—she could already feel it—would be less about paper walls and more about walls she painted herself. The kind that hold. The kind that shelter. The kind that hum when you laugh in the kitchen at midnight over a pan of too-salty sauce and decide that perfection is a poor substitute for joy.

Part Four:

The first morning Daniel woke in the condo, he woke before her.

It took Rachel a few seconds to realize why the light felt different. It wasn’t just dawn—Denver’s winter-blue peeling into spring rose—it was the absence of the old alarm bell in her chest, the reflex that used to yank her upright with the thought that she had to be already doing. The clock on the dresser glowed 7:02. Her heart stayed slow, loose in her ribs, as if it had finally been granted the right to be a heart and not a siren.

From the kitchen came the soft bric-a-brac of breakfast: the click of the gas, the quiet metallic kiss of a pan set on the burner, the scrape of a wooden spoon. She lay there for a breath longer and felt the memory of that sentence—It’s seven a.m. and you’re still sleeping—try to lift its old, rusted head. Then it dissolved under the weight of the present: a man humming tunelessly to himself as he diced something, the faint lemon of dish soap, the smell of coffee blooming.

She padded out in a robe, hair in a loose knot. Daniel looked up, smile immediate and unguarded. “Caught,” he said, holding up the wooden spoon in surrender. “I was going to surprise you in bed, but these pancakes and gravity had other plans.”

“Pancakes?” she said, mock-suspicious. “You, sir, promised me eggs.”

“Bribery,” he said. “I thought, why not go big? Also, we had buttermilk because someone bought it—”

“For salad dressing,” she said.

“—but pancakes are a better destiny.”

He plated them with strawberries and a pat of butter that shone like a small sun. The coffee mug he handed her was the chipped one she’d kept, on purpose. “Cheers,” he said, and tapped his mug to hers. “To a sleepy seven a.m. with no summons.”

She laughed, the kind of laugh that plants roots. “To a breakfast that isn’t an audit.”

They ate at the small table that had watched her survive and now had the luxury of watching her enjoy. Outside, traffic began its daily choreography; inside, the apartment held the softness of two people who understood that care could be quiet. When she took the last bite, she leaned back and watched Daniel rinse the plates. He was not a man doing a performance of helpfulness; he was a person in a home he shared and tended.

“What’s on your docket?” he asked over the water’s whisper. She told him about a client presentation in the afternoon and the call with her attorney to sign the last pieces of the divorce settlement—final-final this time, the ink dry, the courthouse clerks done with their eternal stamping. He nodded. “Want me there for the signing?”

“Would you?” she said before she could second-guess the ask. It still surprised her sometimes, this new muscle of accepting help without adding disclaimers. He dried his hands and kissed her forehead. “I’ll be there.”

The courthouse smelled like paper and old air. Rachel had learned to respect these buildings the way hikers respect weather—you don’t argue with it, you prepare. Her attorney, Jenna, met them in the hallway with a folder thick enough to be a doorstop and an expression that warmed when she saw Daniel offer Rachel his arm for the first few steps, not because she needed support but because the world is easier when someone says I’m with you in ways that don’t require fanfare.

“Quick,” Jenna said, flipping a tab and pointing to a signature flag. “Routine. Judge’s chambers already reviewed. He”—meaning Mark—“won’t be here. His counsel submitted signed copies.”

They went in. They signed. The judge—a woman with a gaze like a level measuring a shelf—asked Rachel if the agreement was voluntary, if she understood the property division, the refinancing, the obligations ceded, the obligations assumed. Rachel answered yes, yes, yes. The gavel was almost an afterthought, a formality to sanctify what had already been true in her bones for months.

Outside, the light was startlingly bright. “You’re done,” Jenna said, echoing the text from the closing. “Not just legally. Psychically, too, if there’s any justice in the universe.” She squeezed Rachel’s forearm. “Go buy yourself something ridiculous that makes no sense on a spreadsheet.”

They did not go shopping. They walked to the park and sat on a bench and split a pretzel from a cart whose mustard was alarmingly good. “That was… quieter than I thought it would be,” Rachel said, watching a toddler attempt to negotiate with a pigeon.

“Quiet can be the loudest thing,” Daniel said. “Especially after the other kind.”

Her phone buzzed. A number she recognized but hadn’t saved. She glanced at it, and her stomach did that old, learned twist. “Helen,” she said. “Calling from a different line.”

“Want me to—” Daniel gestured to take the phone.

“No,” Rachel said. “I’ll block it after.” She watched the call ring out into silence. The voicemail icon appeared, then the text bubble. She didn’t listen. On a bench, with the heat of the pretzel still in her hand, she made a deliberate choice not to hand the moment to a woman who had tried to construct her worth with insults and could do so now only in messages that hit a locked door.

“Let’s go home,” she said. She was surprised to hear it—home—and know exactly what it meant.

For a while, life hewed to the precious ordinariness she had craved for so long that its arrival felt like decadence. She worked, she walked, she learned the names of the building’s night desk staff and brought them cookies on Thursdays. She had dinner with her sister and told stories that had nothing to do with bank forms. On Saturdays, she and Daniel developed rituals—coffee at the same shop where she had first learned to say enough, a loop through the farmer’s market, a ridiculous argument about peaches versus nectarines that could have filled an afternoon if they hadn’t had better uses for their mouths.

She saw Mark once. It was in passing, a jolt of color and shape on the other side of a crosswalk—him in a navy jacket, hair shorter, eyes flitting over her and then away as if she were an inconvenient mirror. He looked thinner. He looked the same. He looked like a man who had made a series of choices and now had to live in rooms those choices furnished. She felt a complicated hush inside herself; grief and gratitude both took a chair. She kept walking. He did too.

When the call came from the building’s front desk three weeks later, Rachel was kneeling on the living room rug, putting together a bookshelf with more confidence than skill. Daniel was reading the instructions aloud like a bedtime story for an Allen wrench. The desk clerk’s voice was careful. “Ms. Adams, Helen and Frank Adams are in the lobby. They’re asking to come up.”

For a second, the room telescoped—a long hallway to a long-ago morning. Then the hallway collapsed back into her living room and Daniel’s hand on her shoulder. “Do you want me to talk to them?” he asked.

“No,” she said, standing. “But I’m going down.”

The elevator ride, once a gauntlet, was now just transport. In the lobby, under the strained cheer of an abstract painting and the kind of lighting that makes everyone look a little unreal, Helen stood like a monument to herself, Frank at her shoulder. Time had not softened her; it had lacquered her. She wore a coat the color of raw meat and a mouth pulled tight around words that wanted to fly.

“Rachel,” she said without preamble, loud enough that the lobby’s potted plant might take offense. “We’re here to talk about the home you stole.”

“Good afternoon,” Rachel said, because politeness is a shield with a thousand uses. “This is not a good place for a conversation.”

“We’ll talk wherever I say,” Helen shot back. “This is a free country.”

The desk clerk glanced at Rachel with the question in her eyebrows. Do you want me to call security? Rachel shook her head. “We agreed on a settlement in court,” she said to Helen. “It’s done.”

“That judge took your side,” Helen said. “Women stick together.”

“She took the law’s side,” Rachel said. “Your names were never on anything.”

Frank shifted weight, eyes sliding away the way men’s eyes slide when the facts on paper don’t match the story they prefer. “We lived there,” he muttered. “It was our home too.”

Rachel felt the anger rise and—unlike before—felt it meet something like a net. Her voice stayed even. “You were guests. I asked you to behave like guests. You didn’t. You don’t get to rewrite that.” She paused and softened, not out of obligation but because the truth is easiest to carry when it isn’t sharpened for sport. “I hope you’re well. I hope you find a place you like. But you cannot come here and harass me.”

“Harass?” Helen laughed, brittle as hard candy. “You don’t know the meaning of the word.”

Rachel tilted her head. “I know how to spell it,” she said, and the desk clerk’s mouth twitched behind her hand. “And I know how to report it. This is your one warning.” She nodded at the door. “Goodbye.”

Helen stepped forward, shoulders squared for a scene. Rachel took a single step closer too—close enough that Helen had to look into her face and not her memory of a woman she’d once been able to bully. They stood there, two versions of the future that had tried to inhabit the same house. For a heartbeat, Rachel felt the tug of the old, oxygenless argument—prove yourself, explain, apologize. It passed. She turned to the clerk. “Please note that I’ve asked them to leave. If they come back, call the police.”

She didn’t raise her voice. She didn’t look at Helen again. She turned, walked to the elevator, and pressed the button. The doors closed on the sight of Helen’s mouth opening, and Rachel felt—not triumph, not relief exactly, but a rearrangement inside herself as decisive as moving furniture. A space cleared. Air, suddenly easy.

Upstairs, Daniel had angled the half-built bookshelf into something that looked plausibly vertical. “How’d it go?” he asked.

“She tried to drag me back into the old script,” Rachel said, hanging her coat. “I read from a new one.”

“Proud of you,” he said simply, and held out a screw like an offering.

They finished the shelf. It leaned a little left. They wedged a coaster under one corner and declared it modern.

Summer arrived like it always does in Denver: thunderheads pitching theatrics at the mountains, sun insisting, the city smell turning faintly metallic before a storm. Rachel’s business hit a stride that would have terrified her a year ago and now just meant she kept a better calendar. She hired an assistant—a single mom named Maya with a laugh that convinced spreadsheets to behave—and discovered that leadership, when divorced from trying to control the uncontrollable, could be a pleasure.

On a Tuesday in July, a nonprofit invited Rachel to speak on a panel titled “Women, Work, and the House We Build.” The title made her snort; it was a little earnest, the way panels often are. But the organizer was earnest too in a way that felt like action, not performance. Rachel said yes.

She sat on stage between a social worker who could recite statistics like a litany and a contractor who built housing with her own hands. When it was Rachel’s turn, she told a story she hadn’t planned to tell. Not the blow-by-blow; not the courtroom; not the bank. She told them about seven a.m. and the voice that tried to define her by how quickly she could serve, and about learning the slow, dangerous habit of absorbing an insult and calling it peace.

“I thought endurance was the same as love,” she said into the microphone, the room holding a quiet that wasn’t absence but attention. “It’s not. Endurance without respect is just erosion. I don’t recommend building a life on it.”

Afterward, women and a few men came up to her with thanks that sounded like confessions. One woman—a barista from the cafe where Rachel had once sat shaking over a cup of cold coffee—pressed a hand to Rachel’s forearm and said, “I remember you that night. I’m glad you’re okay.”

“I am,” Rachel said, and was almost dizzy with the accuracy of it.

She went home to a note on the counter from Daniel: “Dinner at eight. Do not eat pretzels. Or do, but leave room.” He’d drawn a lopsided heart next to the instructions and a remarkably good sketch of a peach with the caption “nectarines wish.” She stuck the note to the fridge with a magnet shaped like a mountain and stood for a minute, letting the ridiculousness of her own grin exist without criticism.

The last knock arrived in the fall. Leaves had just begun their quiet self-immolation on the street below. It was early evening, the kind of darkness that feels like velvet and relief. There was no peephole on the condo door; she’d meant to have one installed and never had. She opened the door with the caution of a person who has learned to expect either a package or a problem.

Mark stood there, hands in his jacket pockets, the posture of a boy sent to apologize and the expression of a man who didn’t like the assignment. For a moment, they just looked at each other, two ghosts from a life they no longer lived.

“Hi,” he said, and the word was almost comically insufficient.

“Hi,” she said back. She didn’t invite him in. He noticed, glanced past her shoulder, saw the couch, the plant, the bookshelf that leaned and had not fallen. He looked smaller here, as if the apartment were insisting on scale.

“I got the notice from the court,” he said. “Final.” He lifted his eyes to hers. “I wanted to say… I don’t know what I wanted to say.”

“Okay,” she said. It wasn’t unkind. It was precise.

He rubbed the back of his neck, a gesture she remembered from arguments that had gone nowhere. “I thought about fighting more,” he said, a humorless huff of air masquerading as a laugh. “Mom wanted me to. But I’m… tired.”

Rachel exhaled, not relief, not satisfaction. Something like acceptance. “Me too,” she said. “But I’m also fine.”

He nodded, and there was, at last, something like comprehension in his face. Not agreement. Not apology in the robust form she would have wanted a year ago. Just an acknowledgement that he had been a participant in the breaking and that she had not been the one to cause the fractures. It would do.

“Take care,” he said.

“You too,” she said. “Goodnight.”

She closed the door. She locked it. She leaned her forehead against the wood for a single heartbeat, the way people do in movies when they are performing the act of letting go. Then she laughed at herself and went to the kitchen, where Daniel was burning a careful line into a steak and the room smelled like rosemary and butter and a man who knew the difference between attention and control.

“How was it?” he asked, not prying, but present.

“An epilogue,” she said. “A short one.”

“Good,” he said, and kissed her cheek. “I don’t like long epilogues. They make me feel like the book can’t bear to end.”

She picked up a peach from the fruit bowl and handed it to him. He raised an eyebrow. “Nectarine blasphemy,” he said, but he took it, grinning.

They married a year later in a small ceremony at Chautauqua under a sky so clean it looked like someone had washed it. Rachel wore a dress that could survive a picnic. Her sister cried; Jenna sent a card with a joke about signing things in triplicate; Maya brought her toddler, who chucked flower petals like confetti and attempted to eat one. Daniel vowed respect before anything else, and his voice didn’t shake. Rachel vowed honesty and laughter and the right to nap at seven a.m. if the world allowed it. Everyone laughed, but Rachel felt the words climb into her and stay.

They didn’t honeymoon far. They drove west until the road curved into mountains that looked like sleeping animals. They stopped when they wanted to, walked until their calves winged fire, ate in diners where the coffee tasted like the memory of coffee and the kind of pie that forgives everything else. On the second morning, Rachel woke to a slant of light on the motel curtain and checked the clock out of habit. Seven-oh-three. She lay there and smiled at the ceiling, at the old scar of a water stain that looked like a heart if you tilted your head. Daniel snored softly beside her. The world did not demand anything. She closed her eyes again. The day waited.

Back in Denver, the condo held. It had weathered storms—the literal ones that knocked rain into the windows with fists, and the meteorological events of human life. It knew how to stand. It knew, now, what it was for. Friends came for dinner and left their laughter in the corners. Work continued to both frustrate and delight. There were arguments about things that mattered and quick surrenders about the rest. Plants died and were replaced. The leaning bookshelf stayed up through every season like a private joke.

Sometimes, on the way to the cafe on Saturdays, they passed someone yelling at someone else on a sidewalk, accusations bright and useless in the air. Rachel’s shoulders would lift, the reflex of an old bracing. Then she would feel Daniel’s hand find the back of her neck in that fully platonic, fully intimate gesture he had, and her body would remember the new script: You are not required to pick that up.

On the anniversary of the closing—the day the papers had been recorded and the keys had been entirely hers—Rachel bought a lemon tree small enough to live by the window and stubborn enough to survive Colorado’s dry air. It was both impractical and right. She wrote a little card and stuck it in the soil: For what we survived. For what we built. For mornings that belong to us.

On a late autumn morning, a text pinged from the barista at the cafe: “Guess who came in asking if you still come by? I told her we protect our own.” A winking emoji. Rachel stared at the screen and felt the old fear glimmer, thin and predictable as a shadow at noon. She typed back: “Thanks. I’m good.” She put the phone down and rested a hand on the lemon tree’s glossy leaves. The apartment was quiet. She could hear her own breathing. On the counter, a coffee mug rested in a ring of sunlight.

Seven o’clock came, and she did not flinch. She stretched. She turned the burner under the kettle and watched the flame, blue and competent. From the bedroom, Daniel’s voice drifted, sleepy: “Is it seven already?” She smiled into the steam. “It is,” she called. “And you can stay in bed.”

She poured the hot water over grounds and breathed in the smell that had become the scent of safety. When she brought Daniel his mug, he reached for her with that now-familiar half-awake hand. She slid under the covers, the coffee warm between them like a treaty, and looked up at the crack in the ceiling she still hadn’t patched. It didn’t look like an omen anymore. It looked like a story the house was keeping for her in case she ever needed to remember it.

She thought of all the rooms she had moved through—the old bedroom with its slammed door, the cafe booth with its cold coffee, the glass bank office where she’d fed the creature certainty, the title office with its neat flags, the courthouse with its stamps, the lobby where she’d ended a script, the living room where a leaning shelf decided not to fall. She thought of one sentence screamed at the edge of her bed and how a life had been built in response not by rebuke but by refusal to disappear.

When the kettle clicked off on the stove, the sound was just metal settling, not a gunshot. When the clock turned to 7:10, nothing exploded. When the future knocked, it did so with flowers, with emails that began Dear Ms. Adams, with a hand on her back that said Right here.

Rachel Adams—digital strategist, homeowner, ex-wife, newlywed, person who prefers peaches—closed her eyes. She did not need to rehearse her worth for anyone. She had already lived it.

Outside, Denver woke: buses sighed, sneakers slapped, a dog barked once and stopped, as if reminded. Inside, under a quiet roof that had learned to keep its weather, Rachel took another sip, breathed, and let the morning be ordinary. That was the miracle. That was the ending she’d once thought was for other people. It turned out to be dramatic only in that it lasted.

It’s seven a.m., she thought, and smiled. I’m still sleeping if I want. Breakfast can wait. The world, finally, can wait for me.

Part Five:

Autumn leaned into winter the way a dancer leans into a partner—sure of footing, sure of the turn. Denver’s air crisped. The lemon tree in the window tucked its perfume into the leaves the way people tuck their hands into pockets against cold. Rachel started waking before the alarm by habit not dread, the kind of early that comes from wanting a longer day, not from trying to survive a longer morning.

Work throbbed with good tension. Her assistant, Maya, had learned the contours of Rachel’s brain so well that their hand-offs felt like jazz—no notes dropped, no ego in the way of the melody. They’d taken on a tricky contract with a legacy company petrified of becoming a fossil. Rachel liked coaxing them toward the living—retooling, refocusing, teaching nervous executives to stop mistaking motion for progress. It was, in its way, gentler than what she’d done with her life. Paperwork had been sharper; this was persuasion, patience, the kind of slow heat that turns water into steam.

On a Tuesday in November, the mountains wore the first real snow like priests wear vestments—solemn, celebratory, inevitable. Rachel stood in the kitchen, pouring coffee, and saw an unfamiliar number ring on her phone. She let it go to voicemail. It rang again. She sighed, thumbed it open.

“Ms. Adams?” The voice was tired, professional in the way nurses are professional when they wish the world required less of them. “This is Saint Luke’s. I’m calling because Helen Adams listed you as her emergency contact years ago. She’s here. She asked for you.”

Rachel’s fingers tightened on the mug. “How—why—” She stopped. Sorted the questions by usefulness. “Is she okay?”

“She had a minor stroke,” the nurse said. “Stable. Not life-threatening, but life-informing. She’s… insistent.”

Rachel looked at the stove, at the gas flame under the kettle, at the lemon tree’s glossy leaves. She thought of a lobby encounter and a mouth like a sharpened thing. She thought of a lifetime of words that had aimed to reduce her. She thought, startlingly, of the little girl inside her who had once believed that being good was how you avoided harm.

“I’ll come,” she said, and surprised herself by how immediate the yes was. Not because she owed it. Because she could afford it. Grace is a currency too when you’re not spending it to buy permission to exist.

Daniel looked up from his laptop at the table. “Hospital?”

“Helen,” Rachel said. “Stroke. Small. She asked for me.”

He set his laptop aside and stood as if ready to go without being told what his role would be. “Want me there?”

Rachel weighed the offer and felt something like a compass steady inside her. “Yes,” she said. “But wait in the car for a bit? Let me take the first ten minutes by myself.”

He kissed her temple. “You got it.”

Saint Luke’s smelled like sanitizer and exhaustion chased by coffee. Rachel followed the nurse down a corridor where hope and hard news had worn grooves invisible to the eye. Helen lay in a bed that made her look smaller, a thing Rachel wouldn’t have believed possible. The raw-meat coat was gone, replaced by hospital blue. She still managed to look like she was giving orders to the ceiling.

“Rachel,” Helen said, and managed Rachel’s name the way some people manage the word please—as if unused to it sitting in her mouth. “You came.”

“I did,” Rachel said, and pulled up a chair with the dignity of a person who knew when to leave and when to sit. “How are you feeling?”

“Like I’ve been mugged by my own blood,” Helen said. Then, quickly, before kindness could find a foothold, “Are you happy now?”

Rachel thought about lines in sand, about bank offices and folders called WINTER, about keys warm in her palm. She thought about how many times she had been asked to swallow an accusation to keep a peace that was never going to be offered in good faith. She set her hands on her knees. She did not take the bait.

“I’m here,” she said. “Not to be useful. Not to be forgiven. Just to be decent. What do you need?”

Helen’s eyes flashed. The wisest women Rachel knew had told her to expect this—that a person who has not learned to accept help without humiliation will try to turn help into humiliation. Helen opened her mouth. Closed it. When she spoke, the words came out sideways. “Frank is in the waiting room. He’s useless. We need to call Mark. He doesn’t pick up for his father.”

“I’ll call him,” Rachel said. “He’ll come.” She wasn’t sure that was true, but she set her voice to the pitch of confidence because sometimes that’s a rope you throw to the person on the other end. She texted Mark: Hospital. Your mother. Minor stroke. Saint Luke’s. Then added: She asked for you.

The reply came quicker than most of his replies had when she’d been his wife. On my way.

Rachel put the phone away. She didn’t fill the silence with the way she used to—talking as a sacrament to ward off judgment. She took in the lines of Helen’s face, the smallness in the leaf-rattle of her breath. She remembered, uninvited, a moment years back: Helen telling a story at a Thanksgiving table about canning peaches with her own mother, hands sticky with sugar, the sun on the kitchen floor like a blessing. People are not only the worst thing they’ve done to us. That doesn’t mean we owe them anything. It means we can know more and still choose less.

“Do you want water?” Rachel asked.

Helen nodded once, unwilling to make need look like a request. Rachel brought a cup with a straw and held it steady in a way that neither infantilized nor abandoned. Helen sipped, swallowed, grimaced. “Hospitals,” she said. “Everything tastes like napkins.”

“True,” Rachel said.

“You look… older,” Helen said, and then, reluctantly, “Better.”

It wasn’t a compliment so much as a meteorological report delivered by a forecaster who didn’t like the weather. Rachel nodded. “I am,” she said. “Better.”

Helen turned her head to look straight at Rachel, as if trying to find purchase on a version of events where she stayed the heroine. “You took my son,” she said, voice low.

“I left your son,” Rachel said, evenly. “That’s different. Then I left your story about me.”

Something in Helen’s face moved—anger crossing with uncertainty like two strangers in a narrow hallway. “You think you’re the good one.”

“I think I’m done arguing,” Rachel said, and the words loosened something in her chest she hadn’t known was still tied.

Mark arrived twenty minutes later, hair flattened on one side like he’d put his hands in it while driving. He looked at Rachel—with surprise, with a fleeting flare of defensive shame—and then at his mother. “Mom,” he said, “How bad?”

“Not bad enough for you to pretend you still call every day,” Helen snapped. And there it was—the script that made conflict a lullaby. Mark flinched. Rachel watched a familiar muscle memory twitch in him: justify, placate, argue. He looked at Rachel, then back at Helen, and—for the first time in their shared story—chose third option: boundary.

“I’m here,” he said. “I love you. Don’t do that.”

Helen blinked. The nurse adjusted a monitor. Somewhere, a code was called over the intercom then resolved. The moment held.

“I’ll give you two space,” Rachel said, rising. “Frank is in the waiting room.” She squeezed Mark’s shoulder as she passed. It wasn’t absolution; it was recognition.

In the hall, she let out a breath she hadn’t realized she’d been storing in her spine. Daniel looked up from a plastic chair, his face open in that way she’d once thought was theater and now knew was simply a rare breed of male adulthood. “How’d it go?”

“She tried to pull me into the old dance,” Rachel said. “I sat it out.”

“Proud of you,” he said, the phrase that had become less a cheer and more a statement of fact.

They walked to the lobby and bought coffee that somehow managed to taste like both comfort and cardboard. Rachel called her sister, told her what had happened in the flattened tone of someone giving a summary, not an invitation to opinion. Her sister said, “You’re a better person than me,” and Rachel said, “No, just a person who can afford to be kind now that kindness isn’t a trap.”

They went home. The lemon tree breathed its private lemonness. The apartment held.

Helen recovered the way people like Helen recover: efficiently, angrily, determined to treat mortality like a rude telemarketer. She went to rehab, harangued a physical therapist half her age into prescribing more exercises than the regimen required, refused to use the walker in public because it told the truth too obviously. Frank, unexpectedly, softened. A man who’d thought love was measured in biscuits started to measure it in rides to appointments and remembering which side of the bed required fewer steps to the bathroom. The world, infuriatingly and beautifully, kept being complicated.