I’ve been an ER nurse for six years.

In that time I’ve seen just about every way a human body can break.

Gunshot wounds at three in the morning. Multi-car pileups on black ice. Overdoses, strokes, heart attacks, chainsaw accidents, bar fights gone wrong. I’ve held pressure on arteries, cracked chests for CPR, watched people bargain with God, watched people let go.

The ER at Mercy General isn’t TV-pretty. It’s fluorescent lights, coffee that tastes like burnt rubber, and a constant background chorus of beeping monitors. It’s where people come on the worst day of their lives and where we try to make sure it’s not their last.

But in all those years, with all those horrors, I’d never seen anything like what happened that Tuesday night.

November 14th.

9:47 p.m.

The moment a dying eight-year-old girl rolled through our doors… and the janitor said he could save her.

The Call

I’m a night-shift nurse. My name’s Casey Williams. Night shift is where the real stuff happens—when the world gets weird and the freak accidents come out to play.

That Tuesday had started like any other: busy but manageable.

We had three patients in beds: one chest pain, one broken ankle, one guy who’d tried to deep-fry a turkey inside his garage and lost a fight with a fryer lid. Two more sat in the waiting room scrolling their phones, complaining about the wait.

No gunshot victims. No trauma codes. For 9 p.m. on a Tuesday, that’s practically a spa day.

I was restocking a cart—saline flushes, IV tubing, tape—when the ambulance radio crackled to life.

“Mercy General, this is Unit 47. We have a pediatric trauma. Eight-year-old female. MVA, high-speed collision, unconscious. Vitals unstable. ETA three minutes.”

MVA.

Motor vehicle accident.

Pediatric.

Pediatric is the word that drops a cold rock in your stomach.

Dr. Graham, our attending that night, looked up from his charting. His eyes met mine over the nurses’ station.

“Casey. Trauma 1. Prep,” he said. “Page Fabre now.”

“Yes, doctor.”

My body moved before my brain caught up. I hit the code button for Trauma 1, dashed down the hall. Lights flicked on in the trauma bay. Monitors beeped alive. I yanked disposable linens over the bed, checked suction, checked oxygen, grabbed IV start packs and laid them out in a neat line.

“Trauma team to Trauma 1. Trauma team to Trauma 1,” came the overhead page.

We had three ER residents on that night. No other attendings. Our trauma surgeon, Dr. Victor Fabre, was on call but not in the building.

I paged him.

No answer.

I paged again.

Nothing.

The ambulance doors slammed open down the hall.

Then everything sped up and went quiet at the same time, the way it always does when EMS brings you someone who’s actively dying.

Alice

They wheeled her in on a gurney.

She looked too small on that big adult-sized stretcher. Dark hair matted with blood. Skin white as the sheets. An oxygen mask fogged with shallow breaths.

Her name, written in black marker on the paramedic’s glove, was Alice Brown.

Behind the stretcher a woman in her thirties ran, blood on her shirt, eyes wild.

“Alice! My baby! Please, please, please—”

Security and one of the techs moved to intercept, gently but firmly.

“Ma’am, you have to let them work,” someone said.

“She’s my daughter!” The woman’s voice cracked. “Please save her!”

My heart pinched, but my hands kept moving. I didn’t have the luxury of being human in that moment. I had a job.

The paramedics did the shift-from-hell shuffle, sliding Alice from their gurney to our bed.

“Eight-year-old female, restrained back-seat passenger,” one of them rattled off as we hooked her up. “T-boned at an intersection. High speed. Lost consciousness on scene. Two large-bore IVs established. We’ve given two boluses of normal saline. BP en route was eighty over fifty, heart rate one-forty. Respiratory at twenty-two, shallow. GCS six. Suspected internal bleed. Abdomen distended, tender on palpation. Possible splenic rupture.”

Dr. Graham swooped in on the right side of the bed, stethoscope in his ears, hands already moving.

“Casey, full set of vitals,” he said. “Let’s see what we’re dealing with.”

I slapped on the blood pressure cuff, the pulse ox, the EKG leads. The monitor blinked awake.

Heart rate: 142.

Blood pressure: 78/46.

Oxygen saturation: 92% on high-flow oxygen.

Her abdomen was swollen, taut. Every instinct I had screamed blood.

“Trauma ultrasound,” Dr. Graham said. “Now.”

I wheeled over the portable ultrasound machine and gelled the probe, handing it to him.

He pressed it gently into the right upper quadrant of her abdomen, eyes on the screen.

I watched over his shoulder.

There it was. A dark, anechoic pool where there should have been clean organ outlines and ribs and liver.

Free fluid.

Blood.

“FAST is positive,” he said grimly, moving the probe. “A lot of fluid. Likely splenic laceration. Grade four, if I had to guess.”

He glanced up at the clock on the wall, then at me.

“She needs the OR,” he said quietly. “Now. Where’s Fabre?”

I checked my pager again.

“Stuck on the expressway,” came the text he finally sent back. “Multi-car pileup. At least twenty minutes.”

Twenty minutes.

We both looked at the monitor.

BP 74/40.

Heart rate 150.

Respirations shallow.

Alice didn’t have twenty minutes.

No Surgeon, No Time

Blood and saline flowed into her little veins, wide open, trying to fill the tank faster than it was leaking out.

“Hang another liter,” Dr. Graham said. “And get two units O-negative ready.”

“Yes, doctor.”

I moved on muscle memory. Spiked another bag. Programmed the pump. My eyes kept bouncing between the monitor and her face.

Her lips were pale. Her lashes glistened with dried tears.

“Come on, kiddo,” I murmured. “Hang in there, okay? You don’t get to check out tonight.”

Dr. Graham looked at me.

“Can we stabilize her until Fabre gets here?”

“I can try,” he said. “But Casey… she’s bleeding into her belly. I’m an ER physician, not a surgeon. I can’t do a splenectomy. Not safely.”

“What about Dr. Jones?” I asked. “Or Okafor?”

“Jones is upstairs in surgery with a bowel perforation,” he said. “Okafor’s at Northwestern tonight for that conference. Nobody else on call. The residents aren’t qualified for this.”

Out in the hallway, Alice’s mother sobbed and begged Security to let her in. Every so often the sound knifed through the closed trauma-room door.

“Is she going to be okay?” she called. “Please tell me she’s going to be okay!”

I didn’t answer. Couldn’t.

Dr. Graham’s jaw clenched.

“I’ll call Northwestern,” I said. “See if they can send someone.”

“They’re thirty minutes away minimum,” he said. “Even with lights and sirens.”

Thirty minutes.

Alice’s pressure dropped again.

“Seventy over thirty-eight,” I reported. “She’s decompensating.”

“I know,” he said.

I watched his hands press against her abdomen, gentle but firm.

She didn’t even flinch.

That was bad. Pain is a sign of life. No response is… something else.

I wanted to scream. To throw something. To walk into the hallway and tell that mother to start saying goodbye.

Instead, I squeezed Alice’s hand, checked her IV lines, and kept doing my job while the clock ticked louder in my head than the monitor.

Then I heard it.

A voice from the corner of the room. Quiet, almost hesitant. But steady.

“I can do it.”

The Janitor

I turned.

Isaiah stood by the wall, mop in his hand, gray hair tucked under a faded ball cap. He wore the hospital’s green janitorial scrubs, the kind no one ever really looks at.

He’d been at Mercy General for two years. Always polite. Always invisible. The kind of person you walk past a hundred times without ever really seeing.

Dr. Graham’s head snapped over.

“Isaiah,” he said gently, the way you talk to someone who’s confused. “Not now, okay? We need the room clear—”

“I can stabilize her,” Isaiah said. His voice had changed. Still quiet, but with an edge of authority I’d never heard before. “Stop the bleeding until your surgeon gets here.”

Dr. Graham stared.

“What?” he said.

“I know what’s wrong with her,” Isaiah said calmly. He nodded toward the ultrasound. “Splenic laceration. Grade four. She’s bleeding into her peritoneal cavity. If you don’t clamp the splenic artery, she’ll be dead in five minutes.”

The room went even quieter.

In that moment, the only sounds were the monitor beeping and Alice’s mother crying in the hallway.

Dr. Graham glanced at me.

The look said it all.

Why the hell does our janitor know that?

“Isaiah,” I said cautiously, “how do you—”

“I can save her,” he said. He looked at Alice, then met my eyes. “I’ve done this before.”

“You’re not a doctor,” Dr. Graham said, the word coming out sharper than he meant.

Isaiah shook his head.

“No,” he agreed. “I’m not.”

“Then you can’t—”

“I can,” Isaiah said. “And she’s out of time.”

Dr. Graham’s face went hard.

“Where did you learn this?” I asked.

Isaiah’s jaw tightened.

“In prison,” he said.

The words fell like a tray of instruments.

“In… what?” Dr. Graham said.

“Stateville,” Isaiah said. “Fifteen years. Medical wing. I assisted in hundreds of surgeries. Stabbings. Gunshot wounds. Blunt-force trauma worse than this. I know what I’m doing.”

“That’s not—” Dr. Graham shook his head. “You can’t just walk into my trauma bay and claim—”

Alice’s pressure alarm shrieked.

“Sixty over thirty,” I called out. “She’s crashing.”

From the hallway: “Please! Somebody help my baby!”

Isaiah took one small step closer to the table.

“I can stabilize her,” he said. “Keep her alive until your surgeon arrives. But you need to decide now.”

Dr. Graham looked at Alice, at the monitor, at me.

I’ve never seen him hesitate before that night. Not once. Not in a code, not in a trauma, not when we had three arrests happening at once.

He hesitated then.

Because every choice in that room was the wrong one.

Let a janitor who learned surgery in prison cut into a child’s abdomen?

Or stand back and watch her bleed to death because we were afraid to break the rules?

“If I let you do this,” he said slowly, “and anything—anything—goes wrong—”

“It won’t,” Isaiah said.

“You can’t promise that.”

“Neither can you,” Isaiah said quietly. “But I’m her only chance.”

I looked at Alice. At her small fingers taped to the IV lines. At the bruises blooming on her torso. At the heart monitor struggling to keep up with her racing pulse.

I thought of her mother in the hallway. Of the empty car seat that would be sitting in some wrecked SUV.

“She’s going to die if we wait,” I said. I looked at Dr. Graham. “You know that. I know that. He knows that.”

Dr. Graham met my eyes. For once, I saw fear there.

I turned to Isaiah.

“Can you save her?” I asked.

He didn’t hesitate.

“Yes,” he said. One word. Absolute certainty. “I can.”

I nodded.

“Then save her,” I said.

Breaking Every Rule

Dr. Graham closed his eyes for a second, like he was saying a prayer. When he opened them again, they were steady.

“Okay,” he said. “Okay. But I’m staying right here, and Casey’s assisting. The second I say stop, you stop. Understood?”

“Understood,” Isaiah said.

He walked to the sink.

And the second he turned on the water, something… shifted.

The quiet, slightly hunched janitor disappeared.

He scrubbed his hands with the force and focus of someone who’d done it ten thousand times. Fingers spread, nails scraped, wrists, forearms. Rinse. Repeat. His shoulders squared. His spine straightened.

He moved like a surgeon.

He didn’t ask where things were. He knew. He tied on a gown, snapped on gloves, stepped up to the table like he’d been doing this every day for years.

“Scalpel,” he said.

My hand obeyed before my brain caught up, placing the blade in his palm handle-first like I’d done so many times for so many doctors.

He made a midline incision. Clean. Straight. No hesitation. No shaky hands. No wasted motion.

“Retractor,” he said.

I handed him the retractor. He opened the abdomen, and the smell of blood and torn tissue hit fresh and metallic.

He didn’t flinch.

“Suction.”

I grabbed the Yankauer, suctioned the pooling blood so he could see.

He spoke low, more to himself than to us.

“Massive hemoperitoneum,” he murmured. “Splenic hilum disrupted. Capsule’s shredded. Grade four, maybe five. We don’t have time to be fancy.”

His hands moved fast but precise. He palpated the spleen, traced the splenic artery with his fingers like he was reading Braille.

“Clamp,” he said.

I passed it to him. My gloves were slick with blood now. My heart was pounding so loud I could barely hear the monitor.

He found the artery and placed the clamp.

The bleeding slowed.

Then stopped.

The suction slurped just air.

The monitor beeped.

“Pressure’s coming up,” I said, my voice shaking. “Seventy-two over forty-two… seventy-eight over forty-eight… holding.”

“Heart rate?” Dr. Graham asked.

“Down to one-thirty and dropping,” I said. “O2 sat ninety-five. She’s stabilizing.”

Isaiah didn’t look up. He secured the clamp, checked for other active bleeds, packed the abdomen with gauze to control oozing.

He worked quickly but not frantically. There’s a difference. I’ve seen inexperienced surgeons sweat through their caps in cases like this.

Isaiah’s forehead stayed dry.

He placed temporary sutures, left everything accessible for the real surgery. He did the minimum necessary to keep her alive and nothing more.

It was… beautiful.

I’ve seen a lot of competent surgeons. Some great ones, even. But there was a kind of economy to what Isaiah did. No extra cuts. No wasted moves.

After what felt both like five minutes and five hours, he stepped back.

“She’s stable,” he said. “The clamp will hold until your trauma surgeon can get here and take over. She’s not out of the woods. But she’s not dying from this bleed anymore.”

Dr. Graham leaned over to check. His hands hovered just above Isaiah’s work, as if he were afraid to disturb it.

“BP eighty over fifty and holding,” I said, barely containing the tears of relief. “Heart rate one-twenty. Sats ninety-six.”

“Textbook,” Dr. Graham murmured. He looked at Isaiah. “Who the hell are you?”

Before Isaiah could answer, the doors burst open.

“Where is she?” someone called, out of breath.

Dr. Victor Fabre. Trauma surgeon. Finally.

He swept in, eyes going straight to the surgical field.

“What—” he stopped. “What’s been done? Who clamped that?”

“The janitor,” Dr. Graham said, sounding a little dazed.

Fabre stared at Isaiah, at the incision, at the clamp placement.

Then he stepped closer, studied it like a jeweler examining a diamond.

“This is…” he said slowly. “This is excellent work. Professional. Who did this?”

“I did,” Isaiah said quietly.

Fabre’s eyes flicked to his janitor scrubs. Confusion warred with disbelief.

“You’re not on my surgery roster,” he said.

“I’m not on any roster,” Isaiah said. “She was dying. I stopped the bleed. She’s all yours now, doctor.”

He pulled off his gloves with deliberate care. The snap echoed.

Then he turned to leave.

“Wait,” I said, reaching out to catch his wrist. “You can’t just walk out. We need to—”

He met my eyes.

“Thank you for trusting me,” he said. His voice held that same sad weight it always did when he said goodnight after mopping our floors. “That’s enough.”

Then he slipped out of the trauma room and disappeared back into the anonymous background he lived in.

The Story Behind the Mop

Fabre finished the splenectomy. He removed Alice’s shattered spleen, cleaned up the cavity, checked Isaiah’s clamp, closed her properly.

Two hours later, Alice was in ICU. Sedated. Breathing on her own. Alive.

Her mother clung to my hands when I told her.

“She’s going to be okay?” she sobbed.

“She’s stable,” I said. “There’s still a recovery ahead. Infection risk. No spleen means we have to be careful with her immune system. But yes. She’s alive. And we expect her to stay that way.”

“Can I see the doctor who saved her?” she asked. “I need to thank him.”

“Dr. Fabre did excellent work,” I said.

She shook her head.

“They told me someone else clamped that artery,” she said. “That without that, she would’ve died before the surgeon even got there. I want to thank him.”

I hesitated.

How do you explain that the man who’d saved her daughter’s life also emptied the trash in the ER supply closet?

“I’ll find him,” I said.

I hunted Isaiah down like a bloodhound.

Not in the staff lounge.

Not in the loading bay.

Not in the stairwell where he sometimes took his breaks.

I finally found him in a supply closet, mopping up a spill.

As if nothing had happened.

As if he hadn’t just done something that would’ve gotten any doctor a commendation.

“Is she okay?” he asked without looking up.

“She’s stable,” I said. “ICU. Fabre says you gave him a perfect setup. He was… impressed.”

Isaiah nodded once.

“Good,” he said. “That’s what matters.”

“Her mother wants to thank you,” I said.

“No need,” he said. “I did my job.”

“Your job is mopping,” I said. “Not clamping arteries.”

He stopped. Leaned on the mop handle. Sighed.

“Tonight my job was stopping her from dying,” he said. “Titles don’t matter much when you’re hemorrhaging on a table.”

I hopped up onto a lower shelf, sat, and studied him.

“You said you learned in prison,” I said softly. “You said you’d done this before. What did you mean?”

He stared at the floor.

“It doesn’t matter,” he said.

“It matters to me,” I said. “You saved a little girl. You broke every rule to do it. I need to understand who I just handed a scalpel to.”

He hesitated.

Then he said, “I was a surgeon. Once.”

My heart stuttered.

“A doctor?” I said.

He nodded.

“Trauma surgeon. ER. Northwestern,” he said. “Twenty years ago.”

“What happened?” I asked.

His jaw clenched.

“I killed someone,” he said. “That’s what the court said, anyway.”

Isaiah’s Story

We sat in that supply closet, harsh fluorescent light buzzing overhead, the smell of bleach and old cardboard filling the tiny space.

And Isaiah told me his story.

He’d been young once. Brilliant. A star surgeon in the making. The kind of doctor other residents shadowed like ducklings, hungry to learn his tricks.

He thrived in the chaos of the trauma bay. Gunshots, stabbings, car wrecks. He saw people at their worst and gave them his best.

One night, a stabbing victim came in. Multiple wounds. Massive blood loss. It was one of those nights when the ER felt like a war zone—patients on stretchers in hallways, alarms blaring, every bed full.

Isaiah did what he always did. He triaged. He prioritized. He took the worst one to the OR.

The patient’s name was Damian Cortez.

He was twenty-three. College kid. Wrong place, wrong time. Wrong friends, maybe.

He had six stab wounds. One had nicked his liver. One had torn his inferior vena cava—the big vein that returns blood to the heart. Another had punctured his small intestine.

Isaiah opened him up. Clamped what he could. Packed what he couldn’t. Called for more blood, more suction, more hands.

They worked for hours.

Damian died anyway.

“You don’t win them all,” Isaiah said. “We say that in trauma like a prayer and a curse. Sometimes the damage is just too much. The body can’t come back from it.”

Damian’s father was Alderman Victor Cortez.

A big name. A bigger ego. The kind of man news anchors praised and whispered about in the same breath.

He wanted someone to blame.

He chose Isaiah.

The press ran with it.

“South Side Talent Cut Down by Negligent Surgeon.”

“Doctor’s Mistake Costs Promising Young Man His Life.”

“Grieving Father Demands Justice.”

The hospital, terrified of bad press, distanced itself. The DA, up for re-election, saw a chance to look tough on “medical malpractice.”

They indicted Isaiah for manslaughter.

His lawyer was a public defender drowning in thirty other cases. Couldn’t afford top-notch experts. Couldn’t take on the political machine pushing for a conviction.

The state hired Dr. Harold Kramer as their expert witness. At the time, Kramer was a respected surgeon who’d found a lucrative second career testifying in malpractice cases.

On the stand, Kramer claimed Isaiah had rushed. Had chosen the wrong order of repairs. Had sutured when he should have stapled. Had missed a clamp.

None of it was true.

But juries don’t understand surgical judgment calls. They understand grieving fathers and confident experts and photos of smiling dead kids in baseball caps.

They convicted Isaiah.

Fifteen years in Stateville.

He lost his license. His career. His marriage. His house. His life.

In prison, he ended up in the medical wing. The prison doctor was old and tired and understaffed. He saw Isaiah’s hands. Saw the way he picked up instruments. Let him assist.

“For fifteen years,” Isaiah said, “I worked on the worst humans you can imagine. Guys who’d kill you for a ramen packet. And in that medical wing, none of it mattered. They were just bodies. Bleeding. Breaking. I fixed what I could.”

He looked up at me.

“Then I got out,” he said. “And no one wanted me anywhere near a patient. Not with a felony on my record. Not with a revoked license. I applied everywhere. Custodial work was the only job I could get in a hospital.”

He shrugged.

“So I mop floors,” he said. “Take out the trash. Clean blood from the walls. Stay close to what I used to be, even if I can’t be it anymore.”

Until tonight, I thought.

“Isaiah,” I said softly. “You were innocent.”

He sighed.

“The jury didn’t think so,” he said.

“The jury was wrong.”

He gave me a small, half-sad smile.

“Maybe,” he said. “Maybe not. Either way, it doesn’t change the past.”

“It could change your future,” I said.

His eyes went wary.

“Casey,” he said warningly. “Don’t do whatever you’re thinking of doing. It won’t end well. Not for me. Not for you.”

“You used your skills to save a life,” I said. “You shouldn’t be mopping floors. You should be in scrubs. Real scrubs.”

He picked up the mop again.

“I am where the system says I belong,” he said.

“Maybe the system’s wrong,” I shot back.

He paused.

“Go check on Alice,” he said. “Make sure she’s okay. That’s what matters.”

But when I went home that morning, I couldn’t sleep.

I fired up my laptop and started digging.

The Rabbit Hole

“Nurse Gets Deep Into Legal Research” is not a headline you see often.

But that’s what I did.

I found old articles. The trial. The op-eds. The outrage.

“Doctor Convicted in Patient’s Death,” one headline from twenty years ago blared.

“Family of Alderman’s Son Finds Justice,” another said.

I pulled up court documents. Testimony transcripts. Medical records.

The prosecution’s theory was neat and simple: Isaiah made mistakes. Those mistakes killed Damian. Therefore, he was guilty.

The defense was… not.

No well-paid expert. No neat charts explaining the catastrophic nature of Damian’s injuries. Just a harried public defender trying to make a complicated medical case to twelve non-medical people.

The more I read, the more my anger simmered.

Isaiah had done what any trauma surgeon would’ve done. Could they argue about technique? Sure. Surgeons argue with each other the way cooks argue about knife brands.

But negligence?

The autopsy noted massive blood loss. Multiple organ injuries. That the wounds were “non-survivable in the pre-hospital setting.”

That line had never been entered into evidence.

I looked up Dr. Kramer.

Five years ago, he’d been sanctioned for false testimony in another malpractice case. Several of his previous opinions had been questioned. His reputation had melted like ice under a blowtorch.

Twenty years too late for Isaiah.

I wrote down names. Case numbers. Dates.

I went to work that night with circles under my eyes and a folder full of printed-out articles.

And walked straight into a storm.

Administration

“Isaiah,” Dr. Graham said when I got to the nurses’ station, “administration wants to see you.”

I felt my stomach drop.

“What?” I said. “Why?”

Dr. Graham looked tired.

“They heard about last night,” he said. “Word’s spreading. They’re… concerned.”

“Concerned,” I repeated. “Concerned that a janitor saved a child’s life?”

“Concerned that an unlicensed former surgeon performed an invasive procedure in our trauma bay and that we let him,” Dr. Graham said. His jaw was tight with frustration. “Liability. Lawsuits. All that.”

Of course.

Of course that’s what they were worried about.

We all filed into Gregory Sullivan’s office. He was the hospital administrator. Mid-fifties. Perfectly groomed hair. Expensive watch. The kind of guy who wore suits that said “I work in health care” but whose eyes said “I work in risk management.”

He sat behind a wide desk that probably cost more than my car.

“Mr. Turner,” he said, looking at Isaiah. “Dr. Graham. Dr. Fabre. Ms. Williams.”

Isaiah stood with his hands folded. Calm. Like he’d been here before.

“Mr. Turner,” Sullivan said, “is it true that you performed a medical procedure on a patient last night?”

“I stabilized a dying child until a surgeon could arrive,” Isaiah said. “That’s what I did.”

“You are not a doctor,” Sullivan said.

“No, sir,” Isaiah replied. “I don’t have a license.”

“You’re not a nurse, not a physician’s assistant, not licensed in any medical capacity.” Sullivan’s tone sharpened. “Yet you performed an invasive surgical procedure in our emergency department.”

“Yes,” Isaiah said. “I did.”

“Do you understand how serious that is?” Sullivan asked.

“I understand that if I hadn’t done it, she’d be dead,” Isaiah said evenly.

Sullivan’s jaw clenched.

“That’s not the point,” he snapped.

Dr. Fabre leaned forward.

“That is exactly the point,” he said. “She was dying. I reviewed his work. It was excellent. If he hadn’t clamped that artery when he did, I would’ve been operating on a corpse.”

“It doesn’t matter if he got lucky,” Sullivan said. “We cannot allow unlicensed staff to perform surgery.”

“That wasn’t luck,” Dr. Graham said quietly.

“It doesn’t matter,” Sullivan repeated. “He broke the law. He broke hospital policy. We cannot ignore that.”

“You’re really going to punish the man who saved her?” I blurted.

“Ms. Williams, this doesn’t concern you—”

“The hell it doesn’t,” I said. “I was there. I handed him the scalpel. If you’re going to crucify him for this, take me too.”

“Casey,” Isaiah said softly. “Don’t.”

“No, I’m not letting them hang this around your neck alone,” I said. I looked at Sullivan. “You know what the headlines will be if this gets out? ‘Hospital Fires Janitor for Saving Child’s Life.’ That’s going to look great on your next donor newsletter.”

Sullivan’s expression flickered.

“There are legal implications,” he said. “If the family finds out an unlicensed person operated on their daughter, they could sue us into the ground.”

“Or they could be grateful,” I said. “Because they are. Her mother wants to thank him. Are you planning to tell her she can’t because he violated policy?”

“That’s none of her concern,” he said.

“It’s absolutely her concern,” I said. “It’s her kid.”

Sullivan stared at me.

“Mr. Turner,” he said finally, turning back to Isaiah, “you’re terminated. Effective immediately. Security will escort you out.”

“No,” I said.

Every head swiveled toward me again.

“You are not firing him for this,” I said. “Not without at least talking to that mother and telling her why. Tell her to her face that you’re punishing the man who saved her child because your paperwork says so.”

“Ms. Williams—”

“And while you’re at it,” I pressed, “maybe call the local news. They’re going to want footage.”

Silence stretched.

Isaiah stood, face unreadable.

“It’s okay,” he said. “I expected this.”

“It’s not okay,” I said. “They’re wrong, and you know it.”

“Out,” Sullivan said. “All of you. I need to speak to Mr. Turner alone.”

We filed out.

I paced the hallway like a nervous relative in an old movie. Dr. Graham leaned against the wall. Fabre sat on a bench, elbows on his knees.

Twenty minutes later, the door opened.

Isaiah stepped out.

“Well?” I demanded. “What happened?”

He gave me that small half-smile again.

“I still have a job,” he said. “For now.”

My shoulders sagged with relief.

“As a janitor,” he added. “On the condition that I never practice medicine in this hospital again. Not even to save a life.”

My relief curdled into anger.

“Then they’re idiots,” I said.

He shrugged.

“They’re protecting themselves,” he said. “I understand.”

“Alice’s mom still wants to see you,” I said. “Will you come?”

He hesitated.

Then he nodded.

“For her,” he said. “I will.”

Butterfly Girl

ICU always feels different from the ER.

The ER is noise and movement and urgency.

ICU is… waiting. Machines humming. Quiet. The long haul of healing.

Alice lay in a bed too big for her, dwarfed by tubing and wires and an oxygen cannula. Her hair had been washed, the blood scrubbed away. Her face was still pale but peaceful.

Lisa, her mom, sat vigil by her side, fingers wrapped around Alice’s small hand.

“This is him,” I said gently. “This is Isaiah.”

Lisa stood.

She didn’t hesitate. She hugged him.

I mean hugged him. Full-body, desperate-parent gratitude.

“Thank you,” she whispered. “Thank you, thank you, thank you. They told me what you did. How you… how you stepped in. I don’t know how to repay you. There’s nothing I can say that’s enough.”

“You don’t have to repay me,” Isaiah said. “I did what anyone would’ve done.”

“That’s not true,” she said fiercely, pulling back to look at him. “Nobody else did. Only you.”

Isaiah’s eyes softened.

“How is she?” he asked, nodding to Alice.

Lisa wiped her eyes.

“They say she’s going to be okay,” she said. “She’ll have to be careful, because… no spleen. But they think she’s going to live a full life. Because of you.”

She glanced at me.

“Can you stay?” she asked Isaiah. “Until she wakes up? I want her to know who saved her.”

He shifted, uncomfortable.

“I’m not sure that’s—”

“Please,” she said. “Just for a few minutes?”

He looked at me. I nodded.

“Okay,” he said.

We sat in a quiet triangle: Lisa holding her daughter’s hand, Isaiah standing by the foot of the bed, me in a plastic chair.

“Her room at home looks like a rainforest exploded,” Lisa said after a while, smiling through her tears. “Butterfly posters everywhere. Books. Stickers. She tells anybody who will listen that she’s going to be a… le—lepo—”

“Lepidopterist,” Isaiah said.

Lisa laughed a little.

“Yeah, that,” she said. “She made me look it up.”

“She likes butterflies?” Isaiah asked.

“Obsessed,” Lisa said. “She loves how they start as one thing and become another. She says it proves that nothing’s ever really stuck the way it is.”

We watched the steady rise and fall of Alice’s chest.

A nurse came in, checked her vitals, gave a thumbs-up, left.

After a while, Alice’s fingers twitched.

“Mom?” her small voice croaked. Her eyelids fluttered.

Lisa was on her feet instantly.

“I’m here, baby,” she said. “I’m right here.”

Alice’s eyes opened. Fuzzy. Disoriented. Then focused.

“Did… did I get hit by a truck?” she asked.

Lisa choked out a laugh and a sob at the same time.

“Something like that,” she said. “We were in an accident. But you’re okay. The doctors fixed you.”

Alice’s gaze drifted over, landed on Isaiah.

“Who’s that?” she asked.

“That,” Lisa said, her voice tight, “is the man who saved your life.”

Alice studied Isaiah for a long moment, the way kids do. Like they’re seeing more than you’re saying.

“Thank you,” she said.

Isaiah’s throat worked.

“You’re welcome, Alice,” he said. “Now you can grow up and study all the butterflies you want.”

Alice smiled, her eyelids already drooping heavy again.

“I will,” she murmured. “Promise.”

She fell back asleep.

Lisa wiped her cheeks, turned to Isaiah.

“I don’t know what happened here, or why you had to break rules to save her,” she said. “But if the hospital gives you any trouble… I’ll go to war for you. Do you understand?”

Isaiah nodded.

“Hopefully it won’t come to that,” he said.

Spoiler alert: it absolutely came to that.

Headlines and Lawyers

News doesn’t stay quiet in a hospital.

By the next day, half the staff knew what had happened in Trauma 1. By the day after that, one of the med students had told her roommate, who worked at a local paper.

Three days later, an article appeared online:

“Janitor Saves Eight-Year-Old’s Life in Emergency Surgery at Mercy General.”

It had quotes from anonymous staff. From “sources close to the hospital.” From people who’d watched from the hallway.

The story blew up.

National outlets picked it up. Morning shows. Talk radio. Social media.

The angle varied, depending on who was telling it.

“Hero Janitor Steps In When Doctor’s Stuck in Traffic.”

“Hospital Policy Nearly Costs Girl Her Life.”

“Convicted Felon Performs Surgery on Child.”

Everyone had an opinion.

Then Lisa Brown did something no one at the hospital expected.

She went on camera.

The local station interviewed her in her living room, butterfly posters visible in the background.

She held up a photo of Alice in her hospital bed, tubes and all.

“I’m grateful to every doctor and nurse who helped my daughter,” she said. “But I want everyone to know something: the first person to save her wasn’t a doctor. It was a janitor named Isaiah Turner. The hospital tried to fire him for it. That’s not right. He didn’t put my daughter at risk. He gave her back her life.”

By the next morning, there were news vans parked outside Mercy General.

Reporters shoved microphones at anyone in scrubs.

“Do you know the janitor who saved the girl?”

“Is it true he was a convicted felon?”

“Do you feel safe working with someone like that?”

We were instructed not to comment.

Of course, not everyone obeyed.

A resident muttered on camera that he’d “rather have Isaiah in the room than half the third-years.”

A nurse told a reporter, “He’s got better hands than most of the surgeons I’ve seen.”

A viral tweet showed a side-by-side of Isaiah in a janitor uniform and in a surgical gown mid-procedure, captioned: “America: Where we throw doctors in prison and make them mop floors.”

A GoFundMe popped up: “Help Get Isaiah His License Back.”

In two days, it raised more than $200,000.

Lawyers called. Some smelled opportunity. Some smelled justice.

One of them was from the Innocence Project.

They had seen Rebecca Hill’s investigative piece—“Was Dr. Isaiah Turner Wrongfully Convicted?”—and wanted to take his case.

Isaiah wanted nothing to do with any of it.

“All this attention,” he said one night in the break room, rubbing a hand over his face. “It doesn’t feel real.”

“It is real,” I said. “You’re trending on Twitter.”

He looked vaguely horrified.

“That’s not a good thing,” he said.

“Depends on the hashtag,” I replied.

He gave me a look.

“Isaiah,” I said, sobering. “These lawyers… they can do something. Get your conviction vacated. Get your license back. You could be a surgeon again.”

“I’m fifty-eight,” he said. “I’m not some hotshot thirty-five-year-old coming out of residency. Even if they cleared my name, there’s no guarantee—”

“It’s a chance,” I said. “A real one. Don’t you want that?”

He stared at his hands.

“I don’t know how to want that anymore,” he said quietly. “I’ve spent twenty years trying not to want it so it wouldn’t hurt so much to wake up every morning.”

“Try anyway,” I said.

He looked at me.

“You’re stubborn,” he said.

“So I’ve been told,” I replied.

He smiled, just barely.

“Okay,” he said. “I’ll talk to them.”

Courtroom Number Five

The wheels of justice move slowly.

Unless there’s a camera involved.

Between public pressure, media attention, and the fact that Isaiah’s conviction had always been flimsy, the courts agreed to hear his case faster than usual.

Six months after the night in Trauma 1, I sat on a hard wooden bench in Courtroom 5, hands clenched in my lap.

The gallery was packed.

Reporters lined the back wall. Nurses and doctors from Mercy sat in clumps, scrub pants peeking out from under civilian coats. Former inmates from Stateville’s medical wing came too, some in suits, some in jeans and work boots.

Lisa and Alice sat near the front. Alice wore a dress covered in cartoon butterflies.

Isaiah sat at the defense table between two attorneys from the Innocence Project. He wore a simple gray suit. No tie. His hands were folded, knuckles white.

At the prosecutor’s table sat a younger man who hadn’t even been out of high school when Isaiah was convicted. The original DA had retired. The Cortez family wasn’t there.

Judge Patricia Delgado took the bench.

She was mid-fifties, hair pulled back, eyes sharp. She’d read the briefs. You could tell. She didn’t waste time.

“Today we are here to consider the motion to vacate the conviction of the State versus Dr. Isaiah Turner,” she said. Her voice filled the room. “I have reviewed the new evidence, including documentation of misconduct by the original expert witness, testimony regarding political pressure on the prosecution, and the previously omitted medical examiner report.”

She went through it piece by piece.

The ME report that had called the injuries “non-survivable.”

The expert witness, Kramer, sanctioned years later for false testimony.

The public defender’s documented caseload at the time of Isaiah’s trial—far above recommended limits.

The fact that critical exculpatory evidence had never been presented.

“The court finds,” she said finally, “that the original conviction was obtained under circumstances that did not allow for a fair trial. Accordingly, the conviction is hereby vacated. The state may choose to retry this case, but given the evidence presented, this court would strongly advise against it.”

She looked directly at Isaiah.

“Dr. Turner,” she said, “as of this moment, you are exonerated of this crime.”

A noise went through the room like a held breath releasing.

I looked at Isaiah.

He didn’t move.

He just sat there, eyes closed, shoulders shaking.

Then Lisa launched herself at him from the front row and hugged him.

“You’re free,” she said, crying. “You’re finally free.”

He hugged her back, tentatively at first, then with all the strength of a man who’d dug through twenty years of concrete grief to reach daylight.

Alice climbed onto the bench beside them, held out a folded piece of paper.

“I drew this,” she said shyly. “For you.”

He took it.

It showed a cocoon hanging from a branch on one side of the page.

On the other side, a butterfly, bright wings outstretched.

“Thank you,” he said.

Scrubs Again

Getting exonerated is not the same as getting your life handed back.

There were still boards to petition. Licenses to reinstate. Assessments to pass.

The state medical board didn’t exactly leap to welcome a sixty-year-old ex-con back into their ranks, even one with a vacated conviction and a national hashtag.

But the same publicity that had made Mercy nervous now worked in his favor.

The board ordered a comprehensive evaluation.

Under supervision, Isaiah assisted in surgeries at a teaching hospital. He passed written exams that stumped some residents. He demonstrated that his skills weren’t just intact—they’d sharpened in adversity.

Eighteen months after the night he’d clamped Alice’s artery, Isaiah walked into Mercy General’s ER wearing navy-blue scrubs.

Real scrubs.

Not janitorial green.

A badge hung from his collar:

TURNER, ISAIAH M.D.

Medical Consultant

He found me at the nurses’ station.

“You clean up nice, Doc,” I said.

He rolled his eyes, but he smiled.

“Consultant,” he corrected. “Not full attending. Not yet. The board wants me supervised for a while.”

“You’re in the room,” I said. “That’s what matters.”

He looked around the ER.

Same ugly beige walls. Same carts. Same scuffed floors he used to mop.

Everything was the same.

And everything was different.

“Feels weird,” he admitted. “I still see that mop.”

“You earned the right to put it down,” I said.

Fabre stuck his head out of Trauma 2.

“Turner!” he called. “You going to stand around admiring the ceiling or you want to help with this chest tube?”

Isaiah’s eyes lit in a way I’d never seen before.

“I’m coming,” he said.

He glanced at me.

“You good?” he asked.

“Always,” I said.

He strode down the hall, into the trauma bay, shoulders squared.

Not as a janitor.

Not as a convict.

As a doctor.

The Impossible Thing

A lot of people think the impossible things in life happen with fanfare. Explosions. Applause. Fireworks.

Sometimes they do.

Sometimes they happen under buzzing fluorescent lights at 9:47 p.m. on a Tuesday while a janitor washes his hands like a surgeon and a nurse decides to hand him a scalpel.

Sometimes they happen in quiet courtroom Number Five when a judge says four simple words:

“You are exonerated now.”

Sometimes they happen when a girl in a butterfly shirt opens her eyes and says “Thank you” to the man who changed both their lives with a single, rule-breaking choice.

People ask me, sometimes, why I trusted Isaiah that night.

Why I didn’t stop him. Why I didn’t refuse.

The answer is complicated and simple all at once.

Because Alice was going to die.

Because every proper channel had failed her.

Because when Isaiah said, “I can do this,” something in his voice told me he wasn’t guessing.

Because sometimes doing the right thing means breaking the wrong rules.

I still work nights at Mercy General.

I still see awful things. Beautiful things. Ordinary miracles that never make the news.

And every now and then, I’ll catch Isaiah at the sink, scrubbing in. In those moments, I see all the versions of him at once.

The hotshot young surgeon.

The inmate in the prison medical wing.

The tired janitor pushing a mop.

The man who risked everything to save a child.

The doctor the world tried to throw away and had to take back.

If you’d told me, before that night, that I’d watch a janitor perform emergency surgery on a kid and then later testify on his behalf in court, I’d have told you to lay off the late-night dramas.

But life is stranger than TV.

Messier.

And sometimes better.

Have I ever witnessed someone do something impossible?

Yes.

I watched a man with no license, no title, and nothing left to lose put his hands inside a dying girl’s body and give her back her future.

I watched the system that broke him bend, just a little, to make room for the truth.

And I watched a mop leaning forgotten in a corner while its owner stepped back into who he was always meant to be.

THE END

News

CH2 – Why One Captain Used “Wrong” Smoke Signals to Trap an Entire German Regiment

The smoke was the wrong color. Captain James Hullbrook knew it the instant the plume blossomed up through the shattered…

CH2 – On a fourteen-below Belgian morning, a Minnesota farm kid turned combat mechanic crawls through no man’s land with bottles of homemade grease mix, slips under the guns of five Tiger tanks, and bets his life that one crazy frozen trick can jam their turrets and save his battered squad from being wiped out.

At 0400 hours on February 7th, 1945, Corporal James Theodore McKenzie looked like any other exhausted American infantryman trying not…

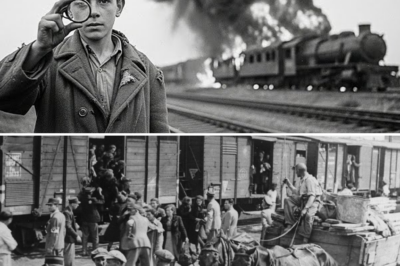

CH2 – The 12-Year-Old Boy Who Destroyed Nazi Trains Using Only an Eyeglass Lens and the Sun…

The boy’s hands were shaking so hard he almost dropped the glass. He tightened his fingers around it until…

CH2 – How One Iowa Farm Kid Turned a Dented Soup Can Into a “Ghost Sniper,” Spooked an Entire Japanese Battalion off a Jungle Ridge in Just 5 Days, and Proved That in War—and in Life—The Smartest Use of Trash, Sunlight, and Nerve Can Beat Superior Numbers Every Time

November 1943 Bougainville Island The jungle didn’t breathe; it sweated. Heat pressed down like a wet hand, and the air…

CH2 The Farm Kid Who Learned to Lead His Shots: How a Quiet Wisconsin Boy, a Twin-Tailed “Devil” of a Plane, and One Crazy Trick in the Sky Turned a Nobody into America’s Ace of Aces and Brought Down Forty Japanese Fighters in the Last, Bloody Years of World War II

The first time the farm kid pulled the trigger on his crazy trick, there were three Japanese fighters stacked in…

CH2 – On a blasted slope of Iwo Jima, a quiet Alabama farm boy named Wilson Watson shoulders a “too heavy” Browning Automatic Rifle and, in fifteen brutal minutes of smoke, blood, and stubborn grit, turns one doomed hilltop into his own battlefield, tearing apart a Japanese company and rewriting Marine combat doctrine forever

February 26, 1945 Pre-dawn, somewhere off Eojima The landing craft bucked under them like an angry mule, climbing one…

End of content

No more pages to load