Part I

The rain in our town never learned moderation. It either spit like a petulant child or poured like it was trying to drown a memory. That morning, it poured. It came sideways under my umbrella, needling my cheeks, sliding down my collar in cold threads. By the time I pushed through the office’s glass doors, my blazer clung to me like something that wanted to own me. The lobby smelled like coffee and wet carpet the way it always did on bad-weather days, which is to say like resignation.

Sarah looked up from the reception desk with that expression I’d come to dread: a mix of sympathy and judgment dressed like concern. “Aubrey… you’re soaked again,” she whispered, as if the rain might hear and be offended. “Why don’t you just drive?”

“If I had a car, maybe I would,” I said, trying a joke that didn’t land because my teeth were chattering.

In the elevator, I wiped the fog off my phone screen and swiped past a text from my mother—Dinner at Grandpa’s this Friday. Don’t be late—and another from my sister, Brooke: a selfie, filter-heavy, captioned first-row parking for seniors with a winky face. I stared until my jaw hurt, then stowed the phone and watched the numbers climb: 3, 4, 5.

By the time I reached my cubicle, my sneakers were squeaking on the tile, that tiny betrayal announcing me wherever I walked. I kept my head down, the way I’d trained myself to do. Pretend nothing’s wrong. Wave it off. Be the kind of person who makes other people’s lives easier by making your own smaller.

No one knew about the lie yet. Not at work, not outside the narrow circle of people who had chosen it. It was a quiet theft, the kind that isn’t exciting enough to tell at parties. It was just rain on top of rain, day after day, while a set of keys I’d been promised jingled in someone else’s pocket.

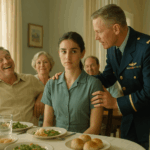

Three days later, we gathered at my grandfather Walter’s house the way we always had for “family dinner,” which in our family might as well have been called “performance night.” Walter had an old oak table that ran the length of his dining room like a runway. We lined up on either side of it as if for a takeoff we never actually took.

Gregory and Elaine—my father and mother—sat stiff-backed with polished smiles they’d practiced on church wives and condo boards. Brooke, two years younger and very secure in that fact, scrolled her phone between sips of sparkling water, her thumb moving like a metronome that only kept time for her.

“Smells good, Gramps,” I said, kissing Walter’s cheek. He smelled like spearmint and aftershave, a scent that always made me feel like I was twelve and the world still thought I might be impressive.

He set a plate of roast chicken on the table and, as he did, let his eyes rest on me a fraction too long. He’s always been a straight shooter with a side of showmanship, the retired shop teacher who could fix both a lawn mower and a meltdown. He waited until the plates circled once and the salad had been politely admired. Then he set down his fork, folded his hands, and asked the question that split the night open.

“So, Aubrey,” he said, casual as a librarian asking for a library card, “how’s the car running? Still treating you well?”

My fork clattered to the plate in a sound that felt obscene. Heat bloomed under my skin. Brooke’s thumb stopped mid-scroll. Elaine’s smile thinned like she’d bitten a lemon. My father’s jaw flexed; I watched his throat work like he was swallowing a rock the wrong way.

“What car?” I asked, though I already knew that I knew. I heard my voice come out small and felt something inside me stand up anyway.

Walter leaned forward, eyes sharp. “The Toyota I bought you for graduation,” he said. “The silver one. Don’t tell me it gave you trouble already.”

Silence pooled over the table so hard the air lost texture. I looked from Brooke to my parents. No one handed me a line. No one tossed me a float.

Finally, my father cleared his throat. “Aubrey,” he said, choosing his polite voice, “you don’t really need a car. Brooke—she deserved it more. She’s younger. She has places to go.”

You could feel the wall of it: the practiced ease of a sentence he’d used a hundred different ways to justify a thousand tiny thefts.

Walter’s face changed in a way I’d never seen. The easy kindness drained and left something older, angrier, more honest. “You what?” he said, his voice booming off the crown molding. His fist hit the oak; the glasses shivered. “I bought that car for Aubrey, and you gave it to Brooke?”

Elaine laughed lightly, a false little trill that failed to make the room stand up straighter. “Dad, don’t exaggerate,” she said. “Aubrey’s always been strong, independent. Walking hasn’t hurt her. Brooke needed it more.”

Something broke in me then, something tiny and important that had held through late fees and hand-me-downs and being told I was “such a trooper.” The chair legs scraped wood as I stood. When I spoke, my voice shook but carried.

“Walking in freezing rain every morning,” I said. “Walking past cars splashing mud on me. Walking while Brooke—” I turned to her, felt my heart pounding in my neck “—while you drove right by me, music blasting, not even slowing down. Do you know how many times I saw you? And you just looked away.”

Brooke’s lips parted; the color drained from her face. “I… I didn’t—”

“Yes,” I said, the word outclean and sharp, “you did.”

Walter planted both hands on the table as if he could hold the whole thing steady by force of will. “You stole from my granddaughter,” he said to my parents, voice low now, the kind of quiet that makes dogs low-growl. “My gift. My trust. And you counted on me not noticing.”

Gregory lifted his hands, palms up, working the old arguments like worry stones. “Dad, you’re not being fair. Aubrey doesn’t need—”

“Don’t you dare finish that sentence,” Walter said, and his face—my face, if I lived long enough to get his lines—hardened into something I admired so much it hurt. “I put her name on the papers.”

The room throbbed with silence. Even the grandfather clock seemed to hold its breath between ticks. For the first time in years I watched fear flicker across my parents’ carefully composed faces, and for the first time in my life I felt the ground tilt toward me instead of away.

Gregory tried again, less sure now. “Dad, listen. Aubrey has always managed. She’s the strong one. Brooke—she’s fragile. She has college events, practices—she’s the one with a future that—”

“Matters?” I finished for him, my voice rusted and new at the same time. “A future that matters? What about me, Dad? Does mine not?”

Elaine rolled her eyes, a move so practiced I could hear the creak. “Don’t be dramatic,” she said. “You’re fine. You always make things bigger than they are.”

Walter’s chair scraped back with a scream. “I won’t listen to another second of this,” he said, pushing up from the table. He disappeared down the hallway, his footfalls a metronome of decision.

Gregory stared at me like he didn’t recognize my face. Maybe he didn’t. Maybe I hadn’t let him see it in years.

My mother whispered fiercely, “Sit down,” as if the posture of my body could fix the architecture of our family.

Brooke stared at the tablecloth like it might offer exit instructions.

Walter returned carrying a thick, battered manila envelope. He tossed it on the table so it skidded to a stop in front of my father. “There,” he said. “Title and proof. The car was purchased under Aubrey’s name. I have every receipt. You forged her signature to give it away.”

My father blanched. Elaine reached for the envelope like reflex. Walter’s glare froze her hand midair.

“You thought I wouldn’t keep records?” he asked, voice cracking on the edge of love and rage. “You thought you could manipulate me, deceive me, and I’d just ask how the roast tasted?” He turned to me, his eyes softening. “Aubrey. Tomorrow morning you’ll have the car. I’ll personally make sure of it.”

Elaine’s voice rose, shrill now. “Dad, you can’t just take it from Brooke. She’s used to it. It will ruin her life.”

Walter’s head pivoted toward her without moving the rest of his body, the way owls do before they decide whether you’re prey. “And what about Aubrey’s life?” he asked, quieter than the room deserved. “Did it not matter while she dragged herself through rain, cold, and humiliation? Did her suffering mean nothing to you?”

Gregory snapped, the false patience gone. “Stop treating her like a saint,” he said. “Aubrey’s strong. She doesn’t need coddling. Brooke—”

“Enough,” Walter roared. “I won’t let you pit them against each other anymore. You’ve shown me exactly who you are.”

I reached for the envelope. My hands shook. Inside, the papers were both familiar and foreign: my full name neatly printed, clean lines, signatures in ink that wasn’t mine. Tears bled into the edges of the page; I blinked them clear. They weren’t from weakness. They were from the sheer relief of finally seeing the bones of a lie that had been living under my skin.

Walter looked at me and, with the smallest of nods, gave me permission I’d been waiting for since I was ten: Say it.

I turned to my parents. “You always said I was strong,” I said, voice steadying. “But that was code for something else. It meant I could be ignored. It meant I could be punished without complaint. You handed her my keys and called it love. You made my endurance your excuse.”

Brooke made a sound that might have been a sob or a hiccup. “I didn’t ask for it,” she said, small. “They gave it to me.”

“And you didn’t refuse it either,” I said, the words falling like a hammer I actually knew how to lift. “You watched me walk by your car, soaked, shaking, and you rolled your window up.”

There was a time that would have been the end of it: a few tears, some furniture polish of apology, then life returning to normal. We were good at returning to normal. Normal was the disease.

Walter’s hand trembled as he slipped a second envelope from inside his jacket and slid it toward me. Gregory went stone-still. Elaine’s mouth fell open. Brooke’s eyes jumped between us like she was watching a tennis match with the outcome already written.

“What is that?” Gregory asked, though he already knew not to like it.

“Something I’ve been holding on to,” Walter said. His voice was calmer now, like a man who’d set down a heavy thing and found another he could carry easily. “A trust fund in Aubrey’s name. I intended to wait. Tonight proves I can’t. You cannot be trusted with her future.”

Elaine gasped, hand to chest. “A trust fund for her? What about Brooke?”

Walter didn’t even turn his head. “Brooke has already taken what isn’t hers,” he said. “My concern is Aubrey. She will not walk in the rain another day. She will not beg for respect in her own home.”

Something electric moved through me—fear, fury, hope—some mad blend that lifted and steadied me at once. My name on an envelope. My name on a title. My name on my own life for the first time in years.

Gregory tried to salvage dignity. “You can’t turn your back on family,” he said, and if there was a more ironic sentence in the English language I didn’t know it.

“You turned your back on me on a sidewalk in the rain,” I said. “You gave away something with my name on it and told yourself I’d ‘understand.’ That’s not family. That’s convenience.”

Walter placed one large, warm hand on my shoulder. “You’re not alone anymore,” he said, speaking to me but looking at them. “And the next time you think ‘Aubrey will manage,’ remember this: managing isn’t an inheritance. It’s a wound.”

For a long moment, no one moved. The grandfather clock found its voice again, tick… tock… like we were all auditioning to see who could keep time. Somewhere outside, the rain had turned to a slow, apologetic drizzle.

“Tomorrow,” Walter said, standing again, “we go to Brooke’s apartment. We take the car. We swap the plates. We call the insurance. If you try to stop me, I will bring the police into my own living room and explain to them exactly what you did.”

Gregory opened his mouth and closed it again. Elaine sat down, the energy drained from her like air from a balloon. Brooke stared at her phone as if it might offer her a brand-new world if she tapped the right app.

I slid the trust envelope into my bag, slid the title back into Walter’s paws for safekeeping, and sat. I could feel the shape of myself reassembling in the chair—taller, without the flinch I’d been wearing as an accessory for years.

This wasn’t just about a car. It had never been about a car. It was about the thousand quiet ways people tell you your life is a set of stairs you were born to sweep.

Not anymore.

Walter cleared his throat. “Now,” he said, oddly gentle, “eat while it’s hot. Cold chicken is an indignity even I won’t tolerate.”

It was so absurdly ordinary that we all obeyed. Forks lifted. Glasses were sipped. The air slowly remembered how to move. No one looked at me the same way, which was a relief and a grief. It would never be the same. Thank God.

After dinner, I walked out into the damp night with papers in my purse and a spine that belonged to me. The streetlamps burned halos into the puddles; the air tasted like metal and newness. Rain had always felt like a weight to carry. Tonight it felt like proof I’d made it through something else.

At the curb, Walter put his hand on the car door and then on my back. “I should have seen it sooner,” he said, some apology more honest than words living in the breath between us.

“You did,” I said. “Tonight, you did.”

He nodded. “Tomorrow morning,” he said, practical again, “we get your car.”

“Tomorrow,” I said.

But I knew even then the car was just the first thing. The list inside me had woken, and it was long. Respect. Trust. My own voice. A thousand invisible keychains tossed back into my hands.

The rain thinned to mist. Somewhere down the block, a dog barked once and then thought better of it. I turned my face up to the sky and let the last drops hit my cheeks like baptism and salt.

For years, I’d been told I could endure. I had. Now they could endure me.

Part II

Walter showed up ten minutes early, the way men who’ve spent their lives waiting on other people’s mistakes tend to do. I heard his truck before I saw it—the low, comforting rumble of an engine that had outlived three sets of tires and one marriage. He knocked once, then let himself in like a person who remembered when my housekey was on a bright blue shoelace.

“Coffee?” I asked, already pouring.

“Black,” he said, then scanned the living room like it might try to lie to him. He held out a zippered pouch I recognized from a lifetime of school supply runs and tax time. “Papers.” He patted his breast pocket. “Pen.” He tapped his temple. “Plan.”

“You sleep?”

“Wouldn’t have helped. We take the car first,” he said. “Then we go to the DMV before your father gets creative.”

The DMV in our county is a room designed by someone who hates joy and chairs. But the plan made sense. I nodded and grabbed my bag. He stood there a moment, jaw working. “You ready, kid?” he asked—kid, like I was still small enough to lift with one arm and carry away from danger.

“I am,” I said. And for once it was true.

Brooke’s apartment sat on the good side of town—not rich, not fancy, but tidy in a way that told you the HOA wrote emails with subject lines like Reminder: Trash bins must be behind the fence. A new-ish Toyota sat in the guest lot, clean, silver, smug. My stomach did a weird flip when I saw it. It wasn’t the car’s fault. It was the way the afternoon light made the metal look like possibility and the last year made it look like a verdict.

Brooke answered the door in an oversized sweatshirt that said Colorado like she’d already decided a state could be a personality. She looked like she hadn’t slept. Her mascara made quiet parentheses under her eyes. Behind her, the apartment smelled like vanilla candles and guilt.

“Aubrey,” she said, voice small with the kind of tenderness people put on when they see a cliff coming and want to look like they meant to jump. “Grandpa.”

Walter nodded once. “Keys,” he said.

She reached toward the entryway bowl and then stopped, fingers hovering over lanyards and loose change. “Mom called,” she said. “She said you were being… dramatic.”

Walter smiled like a wolf who had quit pretending to be a grandfather for a second. “We’re past opinions,” he said. “Keys.”

She picked them up and pressed them into my hand like they might burn her. “I didn’t mean to hurt you,” she said, eyes wet.

“I know you didn’t mean to prevent it,” I said back. “But I saw you. Most days.” I let the keys drop into my bag. Metal against leather: the sound of a door swinging shut.

“I was wrong,” she said. It came out like she wasn’t sure if the sentence was allowed to land in a room this small.

“You were,” I said. I didn’t add I needed you to be right earlier. It drifted between us anyway, cool air nobody could control.

Walter cleared his throat. “Registration and insurance,” he said, palm out.

Brooke fished in a drawer and came up with an envelope stuffed with the life a car has when humans aren’t trying to renovate its purpose. Walter checked the VINs, the dates, the way the signatures lined up or didn’t. Satisfied, he zipped everything into the pouch and tucked it under his arm like a quarterback guarding a fourth-quarter lead.

“We’re going to the DMV,” he told Brooke. “You can come and watch justice be painfully administrative, or you can save your mascara.”

Her mouth trembled. “I’ll stay.”

“Good choice,” he said. Then, softer, because he’s not a monster: “You can fix what you can fix, kid. Start with telling the truth when it costs you.”

She nodded and looked at me like she might ask for permission to be my sister. Not yet. Maybe later. Maybe not. I walked out with Walter and didn’t look back. The silver car glinted. I put my palm on the hood like you do with horses—let them smell you, let them know you aren’t here to spook. Then I slid into the driver’s seat and stared at the dash like it might ask me a question.

“Start her,” Walter said, standing outside with his hands in his pockets like perhaps they’d volunteered to punch something if the engine didn’t catch.

She turned over easy, the way machines do when no one’s asked too much of them. I rolled down the window. The cold morning air folded into the warm cabin like a treaty.

“You remember how to drive?” Walter asked, grinning.

“Unfortunately for the state of Colorado,” I said, and put it in drive.

At the DMV, we took a number and sat. A toddler practiced new consonants; a man in hunting camo told a woman in scrubs about a buck that ran like a rumor; a teenager failed the written test and cried like only 16 can, then laughed at himself and asked if he could take it again. America in one room, fluorescent-lit and carpeted in a pattern designed to hide spilled coffee and despair.

When our number buzzed, we approached the counter like pilgrims.

“How can I help you?” the clerk asked, not looking up yet, fingers already finding the right tabs in a system I suspect only she fully controlled.

“Title corrected,” Walter said. “Original owner purchased for this one”—he jerked a thumb at me—“but the parents rerouted it to the other one. Here’s the purchase receipt with VIN. Here’s the title with the wrong signature. Here’s proof of forgery.” He laid out the papers like a magician revealing that yes, the dove was in his sleeve all along.

The clerk finally looked up, eyes moving from Walter to me to the papers. Her face did the thing people’s faces do when they hear a story they’ve heard a hundred times wearing a new suit. “I’m sorry,” she said, and I believed she meant it. “Let’s fix it.”

She typed like she was angry at the keys. “We’ll need a notarized affidavit from you,” she said to me, “stating you did not authorize the transfer.” A notary appeared from somewhere in the back like they’d been summoned by a bell only clerks can hear. I signed. The notary stamped with a satisfying thump. Paper. Weight. Oxygen.

“We’ll reissue in your name, Aubrey,” the clerk said. “Plates?”

“New,” Walter barked, almost cheerful now that the monster under the bed had a file number.

In the parking lot, I held the new plates like trophies from a race I hadn’t realized I’d been running for years. Walter handed me a screwdriver, and I put them on myself because that mattered—hands on metal, metal on car, car on road, road to work where the receptionist would have to find something else to judge me for.

We made two more stops: my insurance agent’s office, where a woman with nails like silver bullets typed so fast the printout warmed my hands, and the bank, where Walter added his name as a backup contact to the trust account like a man quietly building me a moat.

“You don’t have to—” I started.

“I know I don’t,” he said. “You don’t, either. You can walk away from all of us, you know.”

“I might,” I said, and left it there.

At a light on Colfax, I took my first deep breath of the day and felt something unfamiliar happen—relief that didn’t have shame attached to it. “Where to?” I asked. “Work?”

“Nope,” Walter said. “Mechanic. Then work. No offense to your father, but if he knew you were going to get the car, he may have ‘forgotten’ to rotate the tires or ‘neglected’ the oil.”

The mechanic—a woman in her fifties with a braid and forearms like a sculptor—lifted the hood, peered, nodded. “She’s fine,” she said, patting the car. “She’s a baby. You put good miles on her, not stupid ones. Change your oil at five thousand, not three. This isn’t 1974.”

“Thank you,” I said, and meant more than a receipt for once.

At work, I pulled into the lot and parked in a space so close to the door I could have opened my trunk and loaded it with other people’s opinions. I walked in dry. Sarah looked up and blinked twice like I’d broken the lobby’s agreed-upon weather.

“Aubrey,” she said, glancing out the glass doors. “You’re… not… wet.”

“Miracle,” I said. “Or a Toyota. Hard to say.” She laughed, real and startled, then reached across the counter and squeezed my hand the way women do when they want to say we saw you even if we weren’t helpful about it.

At my desk, emails waited like always. A memo about the new dress code made sure to say that denim was “acceptable if it doesn’t read as casual.” HR wanted to know if anyone planned to work from home during the storm predicted for Saturday, which was rich. My queue of client files gleamed with their odd comfort: tasks that could be done, boxes that could be checked, a set of things that did not ask me to renegotiate my worth.

Around noon, my phone vibrated with my mother’s name. Elaine. I let it ring until voicemail, then listened to her message with the detached curiosity of a person attending a talk about a religion they no longer practice.

“Sweetheart,” she began, the word already doing gymnastics, “I wish you had talked to us before involving your grandfather. You’ve embarrassed your father. You’ve embarrassed Brooke. The way you spoke to us—so aggressive. We did what we thought was best for the family. Brooke had a schedule; you manage so well on your own. Anyway, call me back so we can discuss how to handle this without making it bigger than it is. Love you.”

I stared at my phone and then at the ceiling and then at the part of me that used to combust when she said the word aggressive about me wanting to be treated like a person. Nothing caught fire. I texted two sentences and put the phone face down.

I will communicate through Grandpa for anything involving the car or money. For anything else, we can talk when there is an apology without the word “but.”

It buzzed again almost immediately. My father this time. Aubrey, you need to stop making your sister feel guilty. She didn’t do anything wrong. Don’t pit us against each other.

I didn’t respond. I dragged an email into a folder labeled Later and named a new one Never and put my phone inside my desk drawer like a baby sparrow that needed quiet.

At five, I walked out under a sky that couldn’t decide if it wanted to snow. The Toyota, my Toyota, sat there like a small, loyal animal. I drove to Walter’s, parked, and walked in without knocking. He sat at the table, the trust papers spread like a map.

“We need a plan that doesn’t make you dumb,” he said without preamble.

“Reasonable goal,” I said, sliding into a chair.

“You can move out,” he said. “Today. I’ll cover first and last. The trust can pay for the next year. Don’t tell your parents where. Change your locks twice.”

“I’m not living with them now,” I said. “I’m fine.”

“You’re one text away from them frying your circuits,” he said.

“Already told them to go through you.”

“Good.” He leaned back, eyes half-closed like he was calculating a cut. “Go to HR. Ask for the raise you should have gotten last cycle. Take two days off. Use one to sleep. Use one to sit in a quiet room where no one asks you for a spreadsheet. Then call a therapist who does appointments after five.”

“You’ve been busy plotting my whole life,” I said, smiling for the first time that day without feeling like I was stealing the smile from another version of me who deserved it more.

“I’ve been alive a long time,” he said. “And this route isn’t original. It’s just yours now.”

We made a list. It was absurd and domestic and the opposite of dramatic: oil change schedule; renters’ insurance; second set of keys; a mechanic to call if the car made a noise that sounded like “pay attention.” At the bottom, he wrote in block letters: AUBREY DOESN’T HAVE TO PROVE SHE’S STRONG TO BE LOVED.

“Put that on your fridge,” he said.

“I’ll put it in my wallet,” I said. “And on my bathroom mirror. And on Sarah’s desk.”

“Put it on Brooke’s door if you’re feeling generous,” he said, and then shook his head. “Not today.”

I drove home under a sky that finally surrendered a few tired flakes. The wipers whisked them away—clean, simple, no metaphor, just work being done by a tool designed to do it. In my parking lot, I sat for a minute with the engine ticking as it cooled, my hands still on the wheel like a prayer. I hadn’t realized until then how much of my life had been spent getting small to fit in someone else’s pocket.

Inside, I taped Walter’s sentence to the fridge and the trust account’s routing number to the inside of a folder and my DMV paperwork to the back of my closet door, because the older I get the more holy I think paper is. Then I poured a bowl of cereal the size of a filing cabinet and ate it standing up, because sometimes adulthood is just that—wheat squares at nine p.m. in a quiet apartment you pay for with the parts of your brain no one else sees.

When I turned out the lights, the room didn’t feel like a stage or a courtroom. It felt like a place I could rest without rehearsing apologies. Outside, the weather tried on snow and rain and something in between. Weather is going to weather. I’m going to drive.

In bed, I thought about Brooke’s face when she handed me the keys. I thought about my father’s text and my mother’s voice and the way Walter’s hand felt on my shoulder—heavy, sure, like a doorstop. I thought about Sarah’s laugh and the mechanic’s braid and the clerk’s stamp and the notary’s thump and the way the new plates felt in my hands when I bolted them on.

It hadn’t been about the car. It had been about the keys. About who gets to hold them and who gets told they should be grateful to walk.

Tomorrow I’d go to work dry. The receptionist would look up. People would ask me about rush-hour and gas prices and the weather. I’d tell them the truth: it rained; I drove; I arrived. Inside, something else entirely had moved. I could feel it. A gear catching. A small engine deciding it wants to run.

Out the window, the snow lost interest. I slept like a person who had finally stopped negotiating with the rain.

Part III

The morning after the DMV and the new plates, the sky did that Denver thing where it woke up gray and then remembered it lived near mountains. By eight, sun was elbowing through clouds; by nine, a clean blue sat over the parking lot like a promise it intended to keep. I slid my wallet into my bag and tucked Walter’s sentence—AUBREY DOESN’T HAVE TO PROVE SHE’S STRONG TO BE LOVED—behind my ID where it could eavesdrop on every decision I made.

HR sat on the third floor in a glass-walled suite that made everyone walking past feel suddenly aware of their posture. I had booked time with Lila, our HR director, a woman whose earrings always matched her mood and whose calendar was a game of Tetris I never wanted to play. She looked up when I knocked, then waved me in with two fingers and a smile that said she remembered my name and my work and the memo I rewrote last quarter so that senior leadership didn’t mail out a grammar mistake to three states.

“Close the door,” she said. “Tell me what you need.”

“I need to be paid like the work I do exists,” I said, surprising myself with how easy the sentence came.

She laughed—a quick exhale of respect—and clicked her pen. “Numbers?”

I had them. The projects I took from soup to signage. The last-minute client who called me at six and signed at seven because I answered. The onboarding guide I wrote no one asked for and everyone now used. I laid them out like paper stepping-stones. She listened, eyebrows high, and when I finished, she turned her monitor to show me a spreadsheet that looked like money learning to behave.

“You’re right,” she said. “You should have had an adjustment last cycle. I can get you six percent now, title bump next quarter, and back pay on the discrepancy since January.” She paused. “And two extra PTO days to make up for me not noticing sooner.”

Paper. Oxygen. I nodded so I wouldn’t cry. “Thank you.”

She tilted her head. “You doing okay otherwise?” she asked, eyes flicking toward the band of light where my hairline hid a healing pink line and toward the window where my car sat—small, tidy, mine.

“I’m fixing what I can fix,” I said.

“That’s the best sentence,” she said. “Close the loop with an email. I’ll push it through.”

I sent the email from the stairwell because moving my legs helped keep hope from buzzing too loudly in my ears. When I reached my floor, Sarah stood to clap softly as I walked past, and two people I’d never had a real conversation with gave me the nod men give other men in gyms when a good lift gets done. It felt ridiculous and precise at the same time, like a small parade you didn’t know your street would throw you until the float rounded the corner.

By lunchtime, the raise was in the system with a start date attached, and I pressed my forehead to the cool glass of the breakroom window and laughed at nothing until I had to walk away so my coworkers wouldn’t think I was crying over sad Tupperware.

At four, while I wrestled a spreadsheet into the shape of a story the finance team would respect, a text rolled across my screen from an unknown number. I’m outside. Then, quickly: It’s Brooke. Please don’t ignore me.

I could have. It would have been easy, even righteous. I grabbed my coat and told Sarah I’d be back, then took the elevator down and pushed through the glass doors into a wind that had changed its mind, again, about being winter.

Brooke stood near the bike rack, arms wrapped around herself, sweatshirt sleeves pulled over her hands. She’d skipped mascara today. Her face looked younger without it, tender in a way that made the little sister in her easier to see.

“What do you want?” I asked, because we were past preambles.

“To say I’m sorry,” she said. “And to tell you something before Mom and Dad do.”

She told me quickly, like ripping gauze. Two nights after dinner at Walter’s, our parents had called her to strategize—Dad spinning scenarios like plates, Mom suggesting words like misunderstanding and overreaction the way florists suggest greens to hide holes in bouquets. If Walter went to the police about the forged signature, Dad said, he’d tell them it was an error; Elaine would say the family had agreed and the paperwork got mixed. If I pushed the trust fund conversation into a bank, they’d call the bank manager they played pickleball with and ask to delay any changes with a vague reference to a “family dispute.”

“I told them to stop,” Brooke said, eyes bright with a panic that wasn’t mine. “I told them you had the papers and Grandpa, and that I’d tell the truth. Dad said I was being dramatic. Mom said you’ve always liked being the victim.” She swallowed. “They’re going to call the police and say you stole the car.”

Something in me went very still, like the air before a storm when you can hear a distant train and you’re not sure if it’s thunder. I took a breath and found the fix.

“Thank you for telling me,” I said. “I’m going to call Walter. We’re going to the station now. We’ll get ahead of it. You don’t have to come.”

“I will,” she said, softly. “I want to say it out loud somewhere it counts.”

We met Walter at the precinct—a brick building that had done too many nights and still held itself together with fluorescent light and coffee. The desk sergeant listened with the kind patience of a man who’d been annoyed by better storytellers than my father. I laid the title and affidavit on the counter. Walter added the receipt and a copy of the forgery. Brooke stood to my left and wrung her sleeves.

“Name?” the sergeant asked her.

“Brooke Pierce,” she said, voice shaking. “I’m the sister. I had the car. I knew it was Aubrey’s and I took it anyway. I’m here to say I did that. I’m returning everything right now.”

He blinked, surprised at the speed with which truth sometimes volunteers. “Okay,” he said, tone professional and newly attentive. He turned to me. “You’re filing a report?”

“I’m documenting,” I said. “And I’m asking that if my parents try to file a stolen-vehicle report, it be attached to this. There’s a restraining boundary I want to keep in place. They can argue with a detective instead of my phone.”

He nodded. “Detective Morales can see you,” he said, then buzzed us through a metal door that clacked like a point being made.

Morales was lean and quiet, with a pen he tapped lightly against his notepad in a rhythm that made confession feel possible. He asked for the story without drama. I gave it. Walter gave his dates. Brooke gave hers with a kind of nakedness I didn’t know she owned.

“Here’s where we are,” Morales said at the end, steepling his fingers like a teacher about to give extra credit. “A forged signature on a title is a crime. We could refer to the DA. Sometimes, we divert if restitution is agreed and the victim requests it. That’s your decision. As for the ‘stolen vehicle’ threat—this documentation is going to prevent them from being successful. If they call, we’ll be glad to meet them with the paperwork.”

“Thank you,” I said, and meant both the law and the line in the sand.

Walter shifted in his chair, a mountain deciding where to fall. “I want charges,” he said, blunt as a hammer. “Not because I’m angry—okay, I am—but because I am done explaining why consequences exist. He forged his daughter’s name.”

Morales looked at me. “You?”

I thought about my phone buzzing at my desk, my mother’s sweetheart, my father’s don’t pit us, the sound of rain in my shoes. I thought about Brooke’s face at the bike rack. I thought about what it costs to pull people into a system and what it costs not to when they’ve built their house on the assumption you won’t.

“I want them on paper,” I said finally. “If the DA wants to offer diversion, that’s the DA’s call. My call is this: apology in writing without but, restitution for what I’ve lost and what Walter spent, family therapy with someone who can spell the word boundary, and no contact with me except through Walter or a lawyer for one year. If they won’t sign that, we go to court.”

Morales wrote, nodding a little. “Measurable,” he said. “The DA likes that.”

“Also,” I added, feeling a protectiveness rise that had nothing to do with any of them, “Brooke doesn’t get dragged for this. She’s part of this statement because she chose to be. But if they want to weaponize her, they’re going to hit my name first.”

Brooke’s sleeve fists loosened. “Thank you,” she whispered.

Morales stood. “I’ll draft a summary and flag it,” he said. “You’ll get a case number. If your parents call you, don’t answer. If they show up, don’t open. If anyone drives by your place more than twice, call us. If your tires mysteriously get screws in them, call us. If your mother suddenly wants to bring you soup, don’t eat it.”

Walter grunted. “We’ll add that to the list.”

By the time we stepped back onto the sidewalk, the sky had clouded over again with that unsettled light that makes windows seem to hum. Brooke hugged herself and looked at me, then at Walter, like she wanted someone to give her a script to keep. Walter sighed and pulled something out of his pocket I hadn’t known he had: a keychain with a tiny brass bird on it.

“Your grandmother carried this,” he said, placing it in Brooke’s palm. “She used to say it reminded her to fly out of rooms that didn’t deserve her. You make this do what it was made for.”

Brooke closed her fingers over it like a bruise she was ready to press. “I will,” she said. “I’m… I’m starting therapy. I called three places this morning till one had a slot.”

Pride and grief fought in my chest. I wanted to tell her I would hold her hand. I also wanted to tell her to build new hands that didn’t reach for mine only after they had taken my things. I settled for the truth we could both carry.

“Text me when you leave the appointment,” I said. “Not to tell me what you said. Just to prove you said it somewhere real.”

She nodded. “I will.”

Walter clapped Morales’s card into his pocket like a symbol on a shield and turned toward his truck. “We eat,” he announced. “Decent beef, criminally priced pie, coffee.”

At the diner, a waitress named Dot who’d been slinging plates since ‘98 poured coffee like she’d been deputized to keep spirits inside cups. Walter ordered the blue plate special. I ordered pancakes because the day called for breakfast at four. Brooke ordered soup and managed four spoonfuls before she looked like she might sleep at the table.

Dot topped off our cups and winked at me. “Saw you come in dry yesterday,” she said. “About time.”

I smiled around the lump in my throat. “It is.”

My phone lit on the laminate with a number I recognized under the fake name I’d given it years ago: Condo Committee. I let it go to voicemail. A minute later, a text came through from Walter’s lawyer—he’d looped her in while I was at HR. Call in the morning. We’ll get a protective order drafted that matches your conditions and attach it to the case number. We’ll also notify the bank and the title bureau about any hinky calls from your parents.

“Hinky,” Walter said, peering at the word and approving of it. “That’s a lawyer who watched ‘Columbo.’ Keep her.”

I slept that night with the brass bird on my dresser, not because I wanted to keep it, but because I liked the idea of two sisters sleeping within sight of something that symbolized leaving. In the morning, I woke before my alarm, made coffee without checking my phone, and wrote three lists: Today, Week, When the Weather’s Warm. Today had phone calls and signatures and the number for a therapist Lila had emailed me before she left the office—Tuesdays at five, sliding scale, direct billing. Week had packing tape and a new bolt for my apartment door and a savings transfer to a high-yield account Walter swore wasn’t a myth. When the Weather’s Warm had a line that made me dizzy and happy at once: Weekend in the mountains. Just me. And maybe a book that isn’t about fixing things.

Work was work—emails pinged, printers jammed, someone microwaved fish and was punished by community glare. At noon, Morales emailed me a PDF of the report; at one, Walter’s lawyer sent me a draft of the agreement she’d ask my parents to sign. At two, Brooke texted me a photo of the therapist’s waiting room—beige, tissues, a print of a field pretending to be wild. I’m here, she wrote. I sent back a thumbs-up and a heart, then put my phone down and let the feeling move through me without reorganizing my day around it.

At three, my father called the office’s main line and asked for me by my full name. Sarah said, “She’s unavailable,” then forwarded me the recording because she is the kind of friend the universe makes when it’s feeling guilty about other things. I saved it to a folder labeled Paper & Weather. At four, my mother emailed Lila to complain about the company “taking sides”; Lila replied with a single sentence: We don’t mediate personal matters, Elaine. Please don’t contact us again about this. It was such a tidy refusal that I printed it and stuck it behind the bird on my dresser like a talisman.

By the end of the week, the protective order lived in my glove box and my brain. The bank had flagged my accounts for VIP alerts. My parents had received the DA’s letter and the proposed agreement and had responded exactly the way Walter predicted: with outrage dressed up as concern. The DA responded exactly the way I asked: with a measured explanation of choices and consequences and a list of things that would happen next depending on which door they walked through. Paper turned their volume down without my throat having to.

On Saturday, while a storm thought about becoming a storm and then decided it preferred gossip, I drove to the big-box store and bought sheets that felt like clean promises and a doormat that didn’t say Welcome so much as it said Be Nice. I bought wiper blades because the mechanic’s voice lived in my head and because I could. At a red light, I texted Walter a photo of the blades and he sent back a cartoonish bicep.

On Sunday, I took the car through a wash that turned the gray of a thousand small surrenders into a silver I didn’t recognize yet as mine. The brushes slapped, the water sheeted, the dryer whooshed warm air across the hood, and when the light turned green and the door lifted, I felt something else mechanically simple happen under my sternum: a panel slid, a latch lifted, a part clicked into a place it had been waiting for since the night in the dining room when Walter asked about a car and the room tried to lie.

Driving home, I passed a corner where I used to wait for the bus in January, the wind slicing my ankles, the sky like a lid you couldn’t pry off. I rolled down my window and let the air in on purpose. At the next light, a girl in a raincoat stood on the curb with a backpack too big for the body wearing it. I wanted to pull over and give her something and knew that the something wasn’t a ride. It was the image of a woman driving her own life, stopping at lights, obeying laws, listening to songs that didn’t require anyone’s permission.

Back at my apartment, I taped a new sheet of paper to the fridge under Walter’s sentence. RULES OF THE HOUSE: 1) We don’t apologize for the weather. 2) We don’t argue with paper. 3) We don’t answer the door unless we invited the knock.

I stood there long enough to feel ridiculous and then exactly right. In the afternoon, I sat at my borrowed desk and opened a blank document and wrote a single line at the top. What I Want Next. It scared me and thrilled me in equal measure. I waited to fill it. Some pages deserve patience.

At dusk, the phone buzzed with a number that had become a person, not a role. Brooke: I told her about the car. All of it. She didn’t flinch. She asked me who I wanted to be if Mom and Dad weren’t the judges. I said: I want to be your sister. Not your roommate in a house where love costs you rent. She added a question mark like a child offers a drawing—fragile, smudged, hopeful.

Work on it, I typed. On your side of the street. I’ll be here. But I won’t carry your suitcase.

Three dots pulsed. I know. Thank you. A minute later, a photo arrived: the brass bird on her keyring, swinging from a hook by the door. I put it where I have to touch it when I leave, she wrote.

I set my phone down. Outside, rain started again—gentle, almost polite. I stood at the window and watched it touch the car and run off and felt ready for the next part, which had nothing to do with storms and everything to do with how I intended to drive in weather I didn’t choose.

Endings are drafty things. This wasn’t one. But a door had shut with a sound I now knew I could trust. And the handle, at last, was on my side.

Part IV

The DA’s letter hit my parents’ mailbox on a Tuesday and the apology hit mine on a Thursday—not because their remorse bloomed in two business days, but because lawyers work faster than guilty consciences. Walter’s attorney forwarded me a PDF with the subject line Proposed Terms—Attached, Reviewed. The agreement read like a hardware manual for a family that had been assembled wrong from the start: restitution to Walter for the purchase and associated costs, reimbursement to me for insurance premiums and bus passes and the taxi receipts I’d kept out of pettiness that suddenly felt like wisdom. A one-year no-contact clause except through Walter or counsel. A commitment to six months of family therapy—just them, not me—and a written statement acknowledging harm done without qualifiers.

“If they refuse,” the DA wrote, “we proceed. The forged signature alone is sufficient.”

Walter called before 8 a.m., the way people do when they’re itching to get a thing handled before lunch. “You good with this?” he asked.

“I am,” I said, and was startled to hear how true it sounded in my mouth. “If they sign and shut up, I’m not interested in a courtroom.”

“They’ll sign,” he said. “Your father does the math when handcuffs are the other variable.”

“They’ll still be mad,” I said. “I can live with that.”

“That’s the point,” he said. “You get to live with things that aren’t your fault.”

They signed. Of course they signed. The apology arrived on Walter’s dining table in a cream envelope with my name typed neatly in the center as if typography could stand in for sincerity. He slid it to me and sat back like a dealer who knows the cards aren’t tricks this time.

I opened it. The words were measured, sterile and earnest, the way apologies drafted by counsel tend to be. We acknowledge that we took possession of property purchased for you and transferred title without your consent. We understand that our actions caused you material hardship and emotional distress. We are sorry for the harm we caused. We will abide by the terms set forth. No but, no however, no you know how we are wedged into the middle like a secret. It read like an instruction manual for remorse. I set it down.

“Do you want to keep it?” Walter asked.

“No,” I said. “I want to keep the part where they leave me alone.”

“Good,” he said, and fed the letter into his shredder with a hum that sounded better than any sermon.

Brooke texted me later that day, not with a paragraph but with a picture: a lined index card taped to her bathroom mirror. In block letters it read, TELL THE TRUTH EVEN WHEN IT COSTS YOU. Underneath, smaller: THERAPY—TUES 4:30. PAY PHONE BILL YOURSELF. The brass bird dangled from a hook next to her towel.

Step one, she wrote.

Step one, I agreed.

In January, I moved. Not across town—across the street, to a building with a little more light and a little less carpet, where the hallway didn’t echo with a neighbor’s nightly talk shows. Walter insisted on paying the movers and then insisted on carrying the heaviest box himself anyway, grumbling about kids these days not knowing how to stack books so the box doesn’t rip.

“We have dollies,” the mover said, trying to be polite about masculinity.

“I have a spine,” Walter said, and then put the box down because he also has a pacemaker and a granddaughter who doesn’t let him pretend otherwise.

I signed the lease with a pen that wasn’t borrowed. I changed the locks with a locksmith named Theo who told me he only works mornings now because afternoons are for his daughter’s cross-country meets and “nobody’s emergencies are worse than my kid’s personal best.” He re-keyed the deadbolt and wished me a year of quiet knocks. I tipped too much and taped Walter’s sentence above the new fridge.

Studio Wildflower—the business of making rooms steady enough for joy—didn’t exist yet, not by that name, but it existed in my bones. It grew out of lists and favors and an email from Lila’s cousin who needed someone to coordinate a retirement party at the library on a budget that would make a high school bake sale laugh. I said yes and then built it like an engineer who lived inside Google Sheets. The party wasn’t glamorous—lukewarm coffee and Costco cake and a timeline written in Sharpie—but the librarian cried at the right time for the right reasons and the custodian hugged me on the loading dock for cleaning up my own messes. The next morning three emails waited: Can you help my sister? Can you help our department? Can you help our church? Yes, yes, and yes—if we do it on a schedule that lets me sleep.

Snow came in earnest in February—a daylong blanket that turned sidewalks into suggestions and made the sky tired. I watched it from my window, coffee in hand, watching people make paths. Years ago, that kind of snow would have translated into logistics: bus times, spare socks in my bag, calculating wind angles to keep rain out of my sleeves. Now it meant a less crowded freeway and the smug little pleasure of a car that started the first time. I put on a knit hat Walter’s late wife had made, a knit hat I’d pretended to hate when I was sixteen, and texted Brooke a photo of the street turned white.

Remember sledding on Miller Hill? I wrote.

I remember you dragging both sleds back up, she replied. I’m sorry for that too.

I was tall, I wrote. Gravity was afraid of me.

She sent a laughing emoji and then a photo of her homework: a page in a workbook labeled Boundaries for Adult Children—Week 3. She’d highlighted a line: You can love people and not follow them into rooms that shrink you. Under it, she’d written: Mom’s kitchen and Dad’s car and then crossed both out and written Mine. The brass bird caught a streak of winter sun and flashed like a coin she’d finally decided to spend.

The first time I saw my parents after the shredding wasn’t in a courtroom or a living room but under the fluorescents of a big-box store where everyone goes when they need storage bins and accidental humility. I turned the corner in aisle 37 and there they were: Elaine comparing dish towels as if the fabric might save a marriage, Gregory holding two rolls of duct tape like he’d never met a problem he couldn’t bind.

We stared at each other across a canyon of Rubbermaid, four people who had once eaten from one pot and now lived on separate stoves. Elaine opened her mouth, then closed it as if the clause she needed wasn’t present in the agreement. Gregory’s eyes flicked to my ringless hand, to my keys, to the winter boots that didn’t have salt rings anymore. He nodded, a gesture that contained equal parts hello and admission.

I nodded back. We rolled our carts past each other like strangers choosing not to collide.

Outside, in the parking lot, a wind cut across the asphalt and reminded me that weather doesn’t care about your history. I sat in my car and let my breath slow. The Toyota’s heater clicked on and warmed my kneecaps, a small kindness. I texted Walter: Saw them at the store. No words. Just space.

Proud of you for not filling the silence with explanations, he wrote back. There’s a medal for that somewhere.

By March, HR had not only pushed my raise through but had asked me to run our internal “How We Work” series because, as Lila said, “you’re the only one who can write a checklist that reads like a pep talk.” I accepted because yes and because the idea of paying things forward with bullet points felt like justice wearing sensible shoes. The series went well. People thanked me for showing them where the printer jammed and how to make a meeting an email and when to say no. One afternoon, a new hire caught up to me at the elevator and said, “I heard about your car.” I stiffened by habit and then forced myself to unspool.

“What did you hear?” I asked.

“That you got it back,” she said. “That you didn’t let it make you mean.” She pushed the lobby button. “My mom let it make her mean. I’m trying not to.”

“I recommend paper and breakfast,” I said. “And friends who know when to move, not just when to listen.”

“Noted,” she said. “Also the printer tip saved my life.”

The DA called in April to close the loop. “They signed, they paid, they’re going to therapy,” she said. “Your father made a face at the word accountability so big the court reporter almost laughed, but he kept it inside his teeth.”

“Thank you,” I said. “For turning volume down and consequences up.”

“That’s our whole job,” she said. “That and knowing where the good coffee is.”

“Walter knows that,” I said. “He’s got a mental map of breakfasts in a fifty-mile radius.”

We celebrated closure the way our family celebrated everything that mattered—at Walter’s table, with plates that had seen wars and weddings and the Tuesday blues. This time, it was just the two of us and Brooke. No speeches. No toasts. No declarations meant to echo. Walter made pork chops and apples in a cast iron so seasoned it might have had a Social Security number. Brooke brought a salad that looked like she’d chopped a garden. I brought a pie Dot had smuggled out the back door of the diner with instructions to lie if anyone asked where it came from.

We ate. We talked about the Rockies’ chances this season (“limited,” Walter said, because he loves them enough to be honest). We talked about Brooke’s classes and her internship at a nonprofit that taught financial literacy to high school seniors who had never once seen a budget that wasn’t three digits short. We did not talk about my parents. Not because we were pretending the past was gone, but because the present finally deserved the table.

After dishes, Walter handed me a small wrapped box and tried to look casual about it. He fails at casual the way skyscrapers fail at hiding in a field.

“What’s this?” I asked.

“An old man’s idea of a gift,” he said. “Open it.”

Inside was a key fob with a leather tag stamped with my initials and the year. Simple, stupidly nice, sturdy.

“So you stop carrying your life on a ring that looks like a janitor’s,” he said. “Nothing wrong with janitors. They just deserve their own set of keys.”

I turned it over in my hand, the leather warm from his palm. “Thank you,” I said. “For everything on paper and everything you can’t file.”

He waved it off like a man batting away a fly he secretly appreciates. “You did the hard part,” he said. “I just stood still when standing still counted.”

Driving home, the sky did its east-of-the-mountains glow, the kind that turns parking lots cinematic. I slid the new fob onto my key ring, removed an old tag that said Lost? Call Elaine, and put it in the glove box, not as a relic, but as a reminder that I once believed a different system of return.

Spring made good on its promises in fits and starts; the trees pretended indifference and then exploded green overnight. On a Saturday, I drove out to the park that held Miller Hill and watched families sled in jackets that were all the wrong weight for the weather. A little girl dragged her own sled up the slope, determined and slow. Halfway, she looked back for permission to quit. Her dad waved and yelled, “You got it.” She did. She turned her face forward and kept climbing.

I don’t know why the sight of it cracked me open, but it did—the ordinary heroism of a kid deciding not to go backward. I sat on a damp bench and let it come, tears making a nonsense map on my cheeks. Nobody noticed; Denver knows how to pretend not to see your private weather. When it passed, I laughed at myself, the good kind of laugh, the kind that makes room.

On the way home, the sky went from moody to petulant and rain started in sheets that pinned visibility to my wipers. I slowed, turned the blades up, turned the radio down. At a light, the old bus stop where I’d spent a hundred mornings appeared on my left, the shelter’s plexiglass smeared with graffiti and gratitude. A kid in a hoodie stood under it, head down, shoulders hunched against a world that loves to soak you when you can’t do anything about it. I didn’t pull over. I didn’t offer a ride to a stranger, because safety is a boundary you don’t apologize for. I did roll down the window and shout, “It gets better!” because kindness is the only superstition I still practice.

He looked up, surprised, and grinned. “If you say so!” he yelled back.

“I do,” I said to the wet air, and believed myself.

At home, I opened the windows to let the storm smell inside and brewed coffee strong enough to insult my ancestors. I sat with a yellow legal pad and wrote three columns: Money, Time, Love—Walter’s taxonomy, inherited and improved. Under Money I wrote: Emergency fund—three months; Trust—untouched; Raise—allocated; Retirement—start now, not when scared. Under Time: Work (yes by default, no by exception); Studio Wildflower (sprout it); Therapy (keep going even when busy); Brooke (Sundays, not every crisis). Under Love: Walter; myself; people who walk toward truth when it hurts; no to anyone who loves me most when I’m quiet.

The car sat in the lot outside, rain beading on its hood, water finding the path of least resistance down its windshield, wipers at rest, ready to move when asked. Machines are honest that way. Ask properly; maintain them; they do the job they were built to do. People are complicated. We can be both car and weather and driver.

When the storm eased, the sun made a theatrical late entrance the way it does after afternoons that deserved an intermission. Steams rose from the asphalt; the world smelled like pennies and pine. I took the car to the wash on Colfax, out of habit and as a ritual—rinse, soap, rinse, dry—then parked under a tree that had decided to believe in its own leaves. I wiped down the dash with the back of my sleeve and caught my face in the rearview: an ordinary woman with rain-rouged cheeks and a mouth finally trained not to apologize.

The phone buzzed in the cup holder. A text from an unsaved number: Is this Aubrey? This is Janet at St. Matthew’s. We heard you can make a spaghetti dinner for 200 happen with $400 and a prayer. We need you if you’re free. I laughed and then typed yes, because logistics are love in pants, and because there’s nothing like feeding people until a room sighs and sings. Studio Wildflower, it seemed, had found its first real client.

I drove to Walter’s to tell him, because victories belong at the table with pork chops and stories and the crackle of a radio that never tunes quite right. He met me at the door with a dish towel over one shoulder and that look—proud, relieved, curious—that men of his generation don’t know how to weaponize and thank God for it.

“Guess what?” I said.

“You won the lottery,” he said.

“Better,” I said. “I get to work twice for half the pay and be happy about it.”

He grinned, and we moved into the kitchen, into the small orbit of a stove that had held more seasons than any of us. We ate, we talked, we planned, we laughed. When I left, the rain was back, light this time, a reminder, not a punishment.

I slid into my Toyota, turned the key, and watched the wipers sweep the last beads away. The streetlights pulled long glows across the hood. I lifted the new fob and felt the heft of it, the way leather warms. I thought about the day Walter asked How’s the car I bought you? and about the silence that came after it, the way it split our family and stitched me to myself.

“I’m okay,” I said to the empty car, to the rainy night, to the girl at the bus stop and the woman I had been. “I’m driving.”

I pulled out, signal on, into a lane I chose, into a city that felt a little more mine than it had the day before. The water hit the windshield and the wipers answered, a simple call-and-response that, if you squinted, sounded like a hymn.

The Ending

They say endings are a door closing. Mine was a door closing behind me while another opened at the same time: the sound of a car door thunking shut with my hand on the handle; the sound of an apartment door locking twice because caution isn’t fear; the sound of Walter’s front door swinging wide because love doesn’t knock when it’s already home.

My parents stayed out of my way, as paper required. Brooke stayed in the work, as promises asked. Walter stayed alive and loud, as his presence demanded. And I stayed in the lane that didn’t require a raincoat every morning. On days the sky couldn’t decide, I drove and let it change its mind without making mine smaller.

The title of this whole mess had once been a sentence I couldn’t finish without my throat closing: I walked to work in rain every day until grandpa said, how’s the car I bought you? I froze… Now I could finish it clean: …then I drove.

And kept driving.

— The End —

News

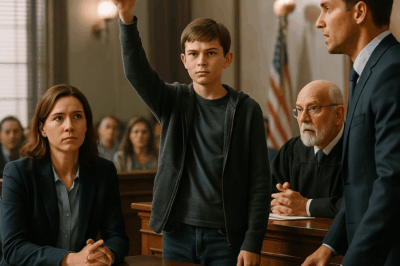

My Ex Told the Judge Our Son Wanted to Live With Him. Then My Son Pulled Out His Phone… CH2

Part I The courtroom was quiet, but not the kind of quiet that helps. It was the kind that made…

My Son Broke a Bully’s Arm. His Father Came For Me, Then I Said The One Word That Made Him Flee… CH2

Part I On Maple Street, the morning always started with sunlight and simple math. Two eggs, over easy. One travel…

Cheating Wife Walked Into The Kitchen & Froze When She Saw Me,”You Didn’t Leave?”… CH2

Part I The saw kicked back and bit deep into my palm, splitting skin like wet paper. A scarlet V…

My Parents Hid My Tumor, Calling It “Drama”—Then the Surgeon’s Discovery Stunned Everyone… CH2

Part I The lump started like a bad idea: small, ignorable, something you tell yourself you’ll “deal with later.” I…

My Dad Left Me On The Emergency Table Because My Sister Had A Meltdown – I’ll Never Forget This… CH2

Part I Antiseptic burns in a way that feels righteous. It bites the skin as if scolding flesh for failing…

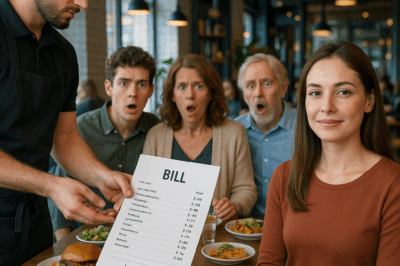

‘RACHEL, THIS TABLE IS FOR FAMILY. GO FIND A SPOT OUTSIDE.’ MY COUSIN LAUGHED. THEN THE WAITER DROPP… CH2

Part I The leather folder landed in front of me like a trap snapping shut. I didn’t flinch. I didn’t…

End of content

No more pages to load