Part I

The day we argued in the nursery, the paint was still tacky on the baseboards and the crib instructions lay crumpled like shed skin on the floor. Sunlight smudged across the walls in pale rectangles; everything new pretended to be permanent. I remember thinking that scent—fresh paint and sawdust—smelled like beginnings. It turns out it also smells like last chances.

Ethan stood by the brand-new crib, squinting at a screw like the translation might materialize if he glared hard enough. He had the sort of careful concentration that made people trust him with small planes and broken hearts. Mine, years ago, had fallen into his hands by accident; he’d kept it like a keepsake, paying its rent and dusting it with ordinary kindness. It thrived in the plain sunlight of his care. I took that for granted. Most people do.

“It’s not normal, Clara,” he said, tightening the last bolt, voice still smooth but stretched tight at the edges. “It’s not normal for your ex-boyfriend to be this involved in our pregnancy, in our life.”

I was folding onesies into tidy stacks, smoothing the ribs of cotton like that mattered. Something hot and adolescent rose up in me. The defenses that came with my first heartbreak—the one Noah had given me—were well practiced and quick on the draw. “I can’t believe you,” I said, and it was the truth: I couldn’t believe a man I respected was willing to doubt me in this tender place. “I’m pregnant and emotional, and you’re trying to control me. He’s a good friend who cares about me.” I said it precisely as if the words were an incantation that could make it so.

Ethan’s brow, always soft around the edges like he’d been born sympathetic, scrunched in a pained way that made me want to pretend I didn’t see it. He stepped closer, one hand on the crib rail as if it could steady him. “He’s not just a friend, Clara,” he said quietly. “He’s your ex-boyfriend who’s clearly still in love with you. And you’re either too blind to see it, or you enjoy the attention too much to stop it.”

If I had been capable of standing in that moment, letting the words touch down without my ego swatting at them, it might have gone differently. That’s the story I tell myself on the nights I count the ifs like stars. Instead I lifted my chin. “That’s a horrible thing to say. You’re supposed to be my husband, my support system, not the one trying to isolate me when I need people the most.”

The truth is, I had needed Noah once in a way that made me defer to him on instinct. In college he’d been my hurricane and my shelter; somehow, I mistook the thrill for oxygen. Years later, when he came back to town, the oldest parts of me perked up like they were being called on in class. I told myself I could have both: a marriage solid as a kitchen table, and a friendship stormy as a summer night. I told myself Ethan knew me well enough to trust me. That was the lie I loved most: that trust has nothing to do with behavior, that you can hold a line with your heart while your actions wander.

We sat there in the nursery pretending to arrange picture books by color and heft, and all the while our words carved out a canyon so quiet we couldn’t hear the rock fall. Neither of us crossed it. I stacked “Goodnight Moon” on top of “Where the Wild Things Are,” as if stories about going and coming back could protect us from the fact that some people who leave never return to the same place.

I wish I could tell you I took his hand. Wish I could tell you I asked what would help him feel secure, or that I drew a boundary and then actually honored it. But the truth is smaller and sharper. I told myself the real problem was his insecurity. I told myself that a good, modern woman didn’t need to cut old friends loose to be a wife. I told myself so many things that the simple truth—a man asking his wife to put him first—sounded like misogyny instead of a plea.

If you’d walked in that day, you would have seen a well-loved room, a crib with rounded corners, a mobile still in its box. You wouldn’t have seen the invisible ledger I kept of righteousness points or the way Ethan’s love had begun to fold in on itself like paper swans—the kind you make in middle school and then forget on a bookshelf. You would not have seen my certainty of being right, thick and blinding as fog.

Weeks passed with small shifts that didn’t register at the time. A text from Noah pinging at midnight: “You up? Random baby article for you.” My laughing reply. Ethan’s face turning unreadable at the glow on my screen. Coffee with Noah at the place with the cracked tile near the park—“Just catching up, Ethan”—and then an hour later telling Ethan about it breezily, daring him with my posture to object. He rarely did. That’s the thing about kind men: they’ll sweep your crumbs from under the chair and pretend there’s a good reason they’re on the floor.

When the first contraction bit down, three weeks early, I was alone at home. The apartment pulsed with the tiny order of a life about to expand: bottles sterilized and stacked, a diaper caddy fitted with creams that promised miracles. Outside, a Tuesday afternoon leaned toward evening. I called Ethan and heard the panic fill his quiet voice like water pouring into a glass.

“I’m leaving right now,” he promised. “Two hours. I’ll break the sound barrier if I have to.” I believed him because he was the kind of man who promised exactly what he could deliver, up to the edge of what physics and fate allowed. And then fate, being indifferent to promises, stuck a pileup across the interstate.

The contractions tracked closer, crisper, like the tightening of a drum. The rational part of me, still dressed in her nursery outfit, said wait. The panicked part, hair unbrushed, demanded help. My thumb moved before my sense did, pressing Noah’s name. Fifteen minutes later he was at my door with the breathless competence I’d always adored, the old rhythm sliding into place so easily I didn’t stop to ask if I should.

He carried my bag and supported my elbow and clicked the door shut with his foot. He was efficient in a way that felt like safety and sounded like flattery. In the car, between contractions, he told me we were fine, we were exactly on time, we were doing great. He said “we” because Noah never learned the grammar of boundaries. I accepted his pronoun because I didn’t insist.

The hospital swallowed us in fluorescent light and the brisk cheer of professionals who have seen every version of joy and grief. Noah talked to the nurse while I breathed. He fetched ice chips, and I let him, because it’s intoxicating to be the center of someone’s attention—even if you’re supposed to be the center of someone else’s. Between the contractions, I imagined Ethan walking through the door to find us neatly arranged: Noah at my side, me doing the brave work, the nurse nodding like a metronome. I told myself Ethan would be grateful Noah stepped in. I told myself I was sparing my husband worry and saving our baby time. What I was really saving was the story I needed to believe about myself: that I was blameless and modern and generous, the kind of woman who could thread the needle between loyalty and nostalgia without pricking anyone’s skin.

By the time Ethan arrived—tie loosened, hair like he’d run a hand through it a thousand times—the room had the settled feel of a story already underway. He stepped in and the air changed, like the moment a storm arrives and your inner ear adjusts. I saw his eyes flick to Noah’s hand on mine, to the chair Noah had claimed, the one nearest the bed. I saw something collapse in his face, quick as a building slated for demolition, beautifully impossible one moment and reduced to dust the next.

“Hey,” he said, coming to the other side of the bed. “How are you feeling, babe?” I said “hanging in there” and turned my face toward the hand that was already pressing into my lower back. “Noah, can you press…like the nurse showed you?” I asked, and I swear—and this may be the most shameful truth of all—I didn’t mean to choose. I didn’t think of it as a choice. My body simply reached for the person who currently had his hands on its pain like a dowsing rod, and I let it.

I would replay that moment later, the shape of my head turning away from my husband, the way a muscle flinches from heat. I would tell myself I was in labor and anyone would have done the same. That too was a story I needed. The reality felt worse: I had built a life where turning away was easier than turning toward.

Noah moved into the space before Ethan could, and the next hours followed that pattern with a mechanistic, merciless rhythm. Noah fetched and held and advocated; Ethan awkwardly tried to insert himself into the choreography, like a man arriving at a dance two songs late. Nobody called cut; nobody told him where to stand. He defaulted to the perimeter and burned there, a sun behind a ridge.

When people talk about the moment that ruins them, they often mean something dramatic: a betrayal discovered, a slap heard in a quiet room, a sentence dropped like a grenade. I did not see my moment for what it was when it arrived. I thought it was sweet. I thought it was a small thing. The nurse’s smile hovered, tentative. “Do you want to hold your daughter?” she asked. My mind, thick with too little sleep and too much pain, made a pathway like water chooses the old riverbed.

“Let him hold her first,” I murmured. “He’s been here from the beginning.” I meant the beginning of labor, the room, the instant. Ethan heard the whole timeline. I saw the nurse’s eyes flick to him, then back to me, then to Noah. It was such a tiny thing, a tilt of a hand. She put the baby into Noah’s arms.

There was a photo of it. I know because Noah took one and sent it to my phone while I was still on the bed, while Ethan stood in the doorway watchful and wrecked. Noah’s hand is gentle around Lily’s back, and his smile looks like awe and a little like victory. If I had to caption it now, years later, I’d call the photo “Miscalculation.”

If you’re inclined to hate me, I can’t argue you out of it. If you’re inclined to pity him, I can’t say you’re wrong. All I can tell you is that when the nurse put my daughter into the arms of the wrong man, I didn’t recognize any of it as wrong. I put the picture on the screen between me and my husband and said, “Look how cute they are together.” He went paler than the sheets.

When he stepped out for air, I called it dramatic. I called him selfish for leaving. People who use words like “boundary” as synonyms for “control” are very good at names. They can label anything. They can label the sky and the water and their husband’s grief, and hang each with the wrong tag so they never have to pay for returning it later.

In the blurry hours that followed, what should have been gratitude curdled into panic. Ethan moved like a man doing chores underwater. I kept trying to resume the old rhythm with Noah—one that sharpened every time Ethan flinched. The nurse called Noah “Dad,” and he laughed and corrected her, and Ethan took our daughter to the farthest corner and held her as if his arms could put back a glass already shattered.

When we were discharged, I said Noah might stop by because he’d picked up groceries. Ethan said no, and I heard “control.” He meant “I am begging you for one day that belongs to us.” I packed the diaper bag and told myself he’d gotten over it. People can tell themselves anything if it lets them keep the shape of their life.

By afternoon, he was gone.

What he left behind was a letter so short I can quote it from memory. What he took were the things that marked his existence in our daily life—suitcase, laptop, shirts, that sweater the color of the sea near shore. And then he took his belief that I would choose him when choice became the only thing left.

If I had been alone, the apartment would have sounded hollow and instructive. But I wasn’t alone. I was full of fury and a narrative and a sleeping baby who made any quiet seem like an accusation. So I called Noah, and he came, as he always did, to witness my feelings like someone holding a mirror and caring more about the reflection than the person looking into it.

For three days I told a story on Facebook. People believed me because I believed myself. “Nothing shows a man’s true character like how he acts when things don’t go his way,” I wrote, and my friends linked little blue thumbs to it like rosary beads. I said something about single motherhood like a badge I had chosen instead of a consequence I had earned. The warm rush of validation is a drug you can buy with partial truths; I paid in installments.

Ethan texted that he’d be by at 2 p.m. to see the baby and asked that Noah not be there. I told Noah, and he nodded and stayed anyway. The first lie you tell yourself makes all the others possible.

When Ethan arrived, he looked like a man who had driven through a desert and run out of water an hour back. I offered him the glass he asked for: Lily. He took her and the hardness on his face dropped away like a mask that had run its course in that particular play. He didn’t look at me. I went hunting for the switch that makes the hurtful version of a spouse reappear, because that one is easier to argue with, easier to defeat, easier to feel righteous against.

“Are you done with your little tantrum?” I asked. There are things you can say that you can never make unsaid. He lifted his eyes then and the kindness in them was nowhere to be found. He spoke quietly—he always spoke quietly, even now—and told me the story he’d been living. Years of standing politely at the edge of a room while I took calls, and changed plans, and made sure a man I didn’t love anymore never had to feel unloved by me. He called it disrespect. I called it support. We were both right, and only one of us had been hurt by it.

He said he was filing for divorce, and the word hit me so hard that for one second I didn’t breathe. Then I did what I had practiced since childhood: I made it all too dramatic to be taken seriously. “You can’t be serious,” I said. But he was.

He asked for a paternity test. I laughed then; I did. It was a short, ugly sound, the sound of a woman absolutely sure of one thing about her life. When I called Sophie—my friend, the sharp family law attorney who once talked me through a parking ticket like it was a Supreme Court case—she said something I didn’t like about emotional infidelity. She spoke the words slowly, kindly, as if she were offering me a cup of water with medicine crushed into it. “Courts don’t look favorably on boundary-crossing relationships with an ex,” she said, and I wanted very badly to argue with her about what a boundary is for.

I kept seeing the nurse’s face as she put my daughter in Noah’s arms. Professional and polite. Ulcerated with secondhand dread. When I finally asked Noah, later, about that night ten months ago—after the bar, after the joke that slid into a kiss, after the way I went missing in the darkness of my own bad choices—he told me, eyes not quite meeting mine, that nothing had happened. He told me the small lie that let him keep loving himself. I believed him because the alternative was to take a fuse I had already lit and notice, with sobriety and terror, the railroad of dynamite it ran toward.

The day the test results arrived, the park’s swings creaked without children on them. Ethan handed me the envelope like it was a hot coal he’d refused to drop until he could put it into the proper hands. I opened it. I might as well have opened the ground.

“The alleged father, Ethan Mitchell, is excluded as the biological father of the tested child.”

These are the words that make other words irrelevant. They don’t care about your vows or your intent or your social media posts. They require no context. They are, if you let them be, the most merciful kind of pain—clean. Except that nothing about us was clean.

Ethan cried then, in that quiet way he had. He didn’t wail or curse. He looked at our daughter in her carrier and said, “So was I,” when I told him I’d been sure. Then he left me on the bench with a paper I couldn’t stop reading and a life I couldn’t hold still. He told me to call Noah. I did. He didn’t answer. It’s a particular kind of humiliation to call a man to tell him he’s a father and get his voicemail.

That night I went home and held my baby, the anatomy of my guilt a thousand unknown bones. You can love the person you hurt, and the person who hurt you, and the person you haven’t hurt yet, all at once, and it still won’t absolve you. The next part of the story has courts and forms and a conference room the color of resignation. But before we get there, you should know the most important thing: the smallest crack, ignored long enough, becomes a canyon. The scent of fresh paint doesn’t mean the foundation is solid. Sometimes it just means the last coat went on before you noticed where the wall bows.

This is how it started. With a crib, a screw, a hand on my back, and a moment I thought was sweet.

Part II

They say labor is fourteen hours on average; they never account for the arithmetic that time does when your life is collapsing in increments so small you don’t feel the fall until you hit the basement. The night after the park, I packed Lily’s diaper bag with the precision of a person who cannot fix the biggest thing and therefore sharpens the knives around the smallest. Two extra onesies, the nice blanket with the clouds, the pacifier she tolerated one time as a fluke. I carried that bag to my bedroom as if we were going on a trip away from grief. We weren’t.

Sleep that night was a string of starts. Every time I drifted, I dreamed I was in the delivery room again, except in the dream Ethan couldn’t get the door open. He wasn’t late; he just couldn’t come in. The handle stuck under his palm. Noah stood behind me muttering advice. When I woke from the dream, the apartment hummed with the sound of my baby making small, important noises: the wheeze, the chirrup, the sigh. The kind that make you fall back in love with a creature you have not once fallen out of love with.

At dawn I texted Sophie and typed out the words I’d been refusing: “It’s not his.” She asked if I was alone. I typed, “Yeah,” and then added, “Noah’s thinking.” She didn’t reply to that line. She asked only, “Do you want me to come by?” I said no because I had learned everything the hard way and thought the next lesson, surely, would demand solitude. It’s a funny lie we tell ourselves: that we can’t ask for help because this is the important pain and important pain requires an audience of none.

Noah didn’t call for three days. I left voicemail number eight in a voice I didn’t recognize. “She exists,” I said into the static. “Whatever we were—whatever you want or don’t—I need you to meet your responsibility like a man.” Somewhere between the sentences I heard echoes of old fights we’d had in college, where I begged nineteen-year-old Noah to stop flirting with waitresses and he told me I was trying to control him. We were so young. And then we weren’t, and it turned out youth wasn’t the culprit after all.

On day four he texted, Can we meet? I typed back the name of a coffee place that didn’t make my chest ache and then deleted it, realized there wasn’t such a place, and settled on the one with the cracked tile by the park. That tile had been the background of so many afternoons that who we had been was already stained into it. I figured it should hear the truth too.

He arrived looking like someone who had been sleeping just fine. He hugged me, a hug I allowed because not allowing it would have been a difficult new thing, and I was, if nothing else, addicted to familiar difficulty. We sat. He didn’t ask to see a photo. That was the first thing that undid me.

“So,” he said, hands folded like a supplicant who wasn’t actually asking for anything. “This is…a lot.”

“She’s a person,” I said, too sharply. “Not a lot.” He nodded, chastened in the way of a man who has learned to perform the performance of chastening.

“What do you want?” he asked, and I nearly laughed. Want was a dress I could no longer zip into. “Responsibility,” I said. “Show up. Money and time. Visits. Your name on paper. Something that looks like a plan that considers her before your plans.” He exhaled, slow. Stared at the table. His pupils did this old, terrible dance they used to do—calculating how much he could get away with and still claim to be generous.

“I can do money,” he said.

“What about time?” I asked.

“That’s the thing,” he said, scratching at a nonexistent itch on his jaw. “I’m trying to figure out how to fit this into…everything.” He gestured to the air. To his life. To the general concept of existence. It felt to him, I knew, like a sudden, unfair imposition. To me it felt like oxygen extracted from water.

We didn’t raise our voices in that café; we never did. We rehearsed the old roles: I laying out the neat lawyerly arguments Chloe—sorry, Sophie; sometimes I think of her as Chloe when I remember the versions of myself she witnessed—would applaud, and he frowning at the inconvenience of structure. He said the word “space.” I said the word “daughter.” We spoke two dialects of the same language: Avoidance and Consequence.

Leaving the café, my phone lit with a new email. Subject: Motion to Establish Parentage and Custody. From Ethan’s attorney. It wasn’t hateful; it was worse—precise. This was what adult grief looked like in daylight: filings and schedules and captions that stung.

I took Lily to the park that afternoon because I needed proof that my world still contained ordinary joy. Kids in puffy jackets raced to the top of the slide like flags had been planted at the summit. Mothers and fathers negotiated snack treaties. I sat on a bench and let the cold metal climb through my coat into my bones. It was November and the sky was the color of unmade decisions. I scrolled through photos in my phone and paused on a picture of me and Ethan at the beach the summer before—the light perfect, his hand curved around my shoulder like punctuation. At the time I had looked at that photo and thought, “We are boring in the best way.” Now I looked and thought, “I had something and I mishandled it.” I wanted to go back and put the photo back into the moment it was taken and stand there until I learned it by heart.

If you want to know what the next weeks were like, imagine waking every hour to a baby who bleats like a lamb and needs everything done exactly now. Add to that the way grief tugged at my sleeve every time I thought I might nap. Add a lawyer who spoke to me in sentences I kept having to ask her to repeat slower. Add Facebook memories that were suddenly weaponized—“Two years ago today!”—and a hungry algorithm that did not care my stomach was a fist.

When the court date came, I wore a dress that fit my new body and felt like penance. Ethan arrived with his tie straight and his eyes wary but calm. He said hello to me politely. I wanted him to shout; politeness felt crueler. We sat at a narrow table and listened to our lives translated into stipulations. We agreed to a schedule: every other weekend and a night each week for me as the primary parent for now, with a plan to transition once Lily was older. We agreed to state-mandated mediation. We agreed to be, going forward, two reasonable people who had moved on. The judge nodded at our civility as if it were a moral victory.

After, in the hall, we stood close enough that I could smell his aftershave, which always made me think of new notebooks. “I’m sorry,” I said. There’s a quantity to that word. It needs a cup big enough to hold it. Mine sloshed. “I know,” he said.

“Are you—” I began. “Happy?” he finished, with a small, tired smile. “Not yet. Maybe someday.” He put a hand awkwardly in the air near my shoulder, as if remembering the choreography of touch and then deciding against it. “Take care of yourself, Clara.”

I took care of the baby. Myself I treated like a houseplant I watered when I remembered.

Noah, meanwhile, delivered on the money and wobbled on the rest. He came over when he felt like playing uncle, not when it was his turn to be father. He sent gear links at 2 a.m.—“This sleep sack is genius”—as if sharing an affiliate code for parenthood. When he held Lily, he looked like a man who had been congratulated for a thing he didn’t do and suspected the praise was for someone else. He kept calling me “buddy,” the way we talked in those weird years when we tried to be friends after spending a decade not knowing how to be anything but more. It felt infantilizing. I didn’t correct him. Correcting Noah had, historically, been like speaking to wind.

Sophie came over on Tuesdays with dumplings and sternness. She watched me feed Lily and said, “How’s your sleep?” I said, “Fun,” and she gave me a look. She said, “How’s your heart?” and I said, “Working,” and she nodded. Then she told me about a client whose husband had cheated in a grotesque, cinematic way and left her with two kids and a condo. “She keeps thinking there’s dignity in not asking for help,” Sophie said. “I told her, dignity is overrated. Ask.”

“I’m asking now,” I said, trying to make it into a joke. “For you to keep showing up.” And she did. Every Tuesday. The opposite of Noah.

At night, the city lights made bright beads on the ceiling above the crib. I’d rock Lily and whisper little apologies into the soft hair at her crown. “I am going to be better,” I’d say. “I will learn how to love people in the order I promised.” She’d blink at me, ancient and uninterested. She wanted warmth, food, sleep, and the person I could still be.

In the mornings, I’d think about Ethan in a new apartment with his brother’s old couch and a better lock on the door. I’d imagine him in the grocery store reading labels with his careful mouth. I’d picture a woman in the distance of his future—the good kind, the kind who knows the best coffee place in any given zip code—smiling at him because he never hogged conversations. I imagined hating her. But when I examined the feeling, what I found wasn’t hatred, only a made bed I had not learned to sleep in.

When Lily turned six weeks, she had a smile that felt less like gas and more like yes. On the morning of the test in that clinical office, she’d stared seriously at the cotton swabs and opened her mouth obediently. Ethan’s jaw had tightened; he held her afterward and kissed the soft place where her skull still seemed like a miracle happening in time-lapse. I watched his tenderness and thought: He will be a good father to the children he actually gets to have, with a woman who puts him first without making it into a political statement.

I could see the story ending there, a clean cut with a tasteful fade to black: We went our separate ways, each the protagonist of our own better choices. But the world, which is sometimes merciful, can also be thorough. It wasn’t done teaching me.

Two months later, I was in that beige room signing the last papers. Ethan sat beside his lawyer, head bent like a boy’s in church. When it was done, he stood. “I hope you find happiness,” he said. He meant it; I knew the taste of a lie and that was not it. “I’m sorry,” I said. The words were nothing and everything. He nodded, left. I went to the bathroom and pressed my forehead against the cool of the stall, the way you might if you were about to faint or pray.

When I emerged, my phone vibrated. A message from Noah: “Can’t make tonight. Something came up.” He had Lily that evening for an hour to give me one inhale without the baby attached to it. He didn’t come. He didn’t respond to the follow-up. He sent me two hundred dollars on Venmo with the pizza slice emoji. I stood at the crosswalk holding the stroller and understood, finally, the full shape of the man I had married and the man I had kept on the shelf. One had been solid and quiet. The other had been shiny and intermittently present. I had acted like the glint was worth more than the gold.

I wish I could say there was a single hinge point where I turned. There wasn’t. What there was instead: a humiliating scene in my living room where I told Noah not to come back unless he planned to calendar his commitment like a person who understood that pleasure and obligation can be married, too. There was a phone call with his mother, who had always loved me in the lukewarm, complicated way of someone who thinks their son is a charming screwup and, by extension, thinks you must like charm. There was a morning with a feverish baby and a pharmacy drive-thru and a woman behind me in line who said, “You’re doing great,” and I almost cried from the relief of being seen by a stranger.

The night before Lily’s six-month checkup, I took out the box under the bed where I’d stashed old photos I hadn’t been brave enough to throw out. Ethan’s hand on my waist at the wedding. Noah on a concert lawn, grinning at me like a man who had just outrun his better angel. I laid them side by side like exhibits in a trial. Then I did something ceremonial and entirely insufficient: I put every Ethan photo back in the box with a lavender sachet so they’d smell nice when I inevitably opened it again. I threw away one of Noah’s. The one with his arm draped around my shoulders and a look on his face that, in retrospect, was not devotion but delight in ownership. It felt paltry and performative. I did it anyway.

At midnight, I wrote an email to myself. Subject: What I will teach this child about love. The body of the email was a list I had to keep rewriting as if the sentences were ships I was trying to launch into a storm: Respect matters. Boundaries are not political; they are practical. Attention is cheap; reliability is rare. Choose the person who shows up on Tuesday, not the person who texts you at midnight. If someone tells you they’re uncomfortable, adjust, not because you’re controlled, but because you are committed. The baby woke before I hit send. The next morning I read the draft and felt something like resolve, which is the cheapest cousin of action but at least it’s family.

If this were a movie, this part would end with me looking out a rain-speckled window, my face lit by some complicated metaphor, then turning decisively and beginning the montage of getting better. In my actual life, it ended with me standing in line at the pediatrician’s, watching a dad in a suit kneel to tie his toddler’s shoe, thinking about Ethan and how he’d have done that with an economy of motion that made people trust him with small planes. I thought about calling him. I didn’t. Not because I wanted to punish myself or polish my dignity, but because sometimes the kindest thing you can do for a person you loved is to leave their timeline undisturbed.

What came next was the lesson finishing its work.

Part III

The courthouse air had learned long ago how to hold other people’s stories without collapsing under their weight. It smelled like old paper and hope managed by committee. When the clerk called our case for the final time—Case No. 17-5003, Mitchell v. Mitchell—it sounded like a summary of a life in code. The v. was not for versus, I decided; it was for version.

Ethan sat beside his lawyer, neat as always. He had shaved. I wanted to tell him I noticed, that noticing still felt like an act of intimacy I hadn’t earned in a long time. My side of the table had Sophie, who wore her competence like a well-cut suit and didn’t flinch when I made wishes out loud that conflicted with the likelihood of anything. We signed. We recited. The judge made notes. In the space of an hour, the state said yes to what we could not.

Afterward, in the hallway that turned sound to chalk, I handed Ethan a small envelope. Inside were two photos, printed and matte. One was the beach—the one where we looked ordinary and therefore blessed. The other was a picture of him holding Lily in the hospital. Not the first hold; that one lived only on Noah’s phone and in the scabbed-over places of my memory. This was later, when the nurse had finally, maybe resentfully, put Lily into Ethan’s arms and he had looked down like he’d been handed time. The room had been bright and mean and full of expectation. He had gone quiet the way very brave people do right before they keep going.

“I thought you might want these,” I said, voice careful.

He took the envelope, looked at the photos without sliding them fully out. He smiled the smallest bit, a private thing. “Thank you,” he said. He didn’t ask where the first photo was. He didn’t need to.

Sophie was waiting at the elevator, already halfway into another conversation on her phone about a different life she was helping untangle. She waved, mouthed text me, and then was gone, leaving me alone with the echo of past and present.

I walked to the bus stop because I wanted to be moved by something I didn’t have to pilot. I pressed my forehead to the glass and closed my eyes. When I opened them, I saw a mother and father on the sidewalk untangling a stroller strap together, using four hands to fix one tiny knot. An argument fluttered between them in the way of sports fans who love the same team slightly differently; then it was gone and the knot was undone. I wished, in a general way that had no target, that I had known how to invite my husband to help me with knots without making it a referendum on feminism or independence. Being a good wife and a good person turned out not to be mutually exclusive. But I had acted like they were.

At home, Lily and I napped heavy and desperate on the couch. When I woke, there was an email from Ethan’s lawyer with the subject line “Final Decree Filed.” I clicked it and scrolled past formal words that had learned to be unafraid of specificity. When I reached the bottom, there was a well of quiet. I did something I hadn’t done since the day he left: I cried without narrating the crying in my head. No “this is because,” no “if only,” no “maybe someday.” Only water leaving a place that had been storing it under pressure.

That night, Noah texted that his band—of course Noah was still in a band, though he also had a tech job and liked to mention both at parties for different kinds of effect—was playing at a bar near my place. I stared at the message. There are parts of me that are rusted in place and needed a crowbar to move. I found the crowbar. “Can’t,” I typed. “It’s your night.”

He wrote back immediately: “Right, right, of course. I’ll come at 7.”

At 8:15, he wasn’t there. At 8:30, he was. He smelled like a place where people were happy to forget what time it was. He took Lily in his arms and said, “Hey, munchkin,” and for a second I saw the father he might be if he were the man he sometimes believed he could be. Then his phone vibrated, and he shifted his shoulder to keep the baby steady while typing a message with the care of someone changing a lightbulb using a chair on a table on a wobbling floor.

“No phones while holding her,” I said.

He glanced up, affronted. “Everything okay over there, Officer?”

“You’re late,” I said, “and you’re not present. Be one or the other. Preferably neither.”

He rolled his eyes in an exaggerated way that made my hands itch to clap ironically. “You’ve changed,” he said, like it was a bad thing.

“I’m trying to,” I said. “For her.”

He sat, bounced Lily lightly, and she settled in the way babies do to warmth, not reputations. “I’m doing my best,” he said.

“Try better,” I said.

It should have started a fight that lasted all evening. Instead, it ended one that had been looping for years. He pocketed his phone and did the thing his hands learned quickly: he held our daughter; he spoke to her as if she were comprehending; he wiped milk off her chin with his sleeve and then remembered and used the burp cloth. Small competence looks a lot like love in a nursery at night.

On his way out, he stood awkwardly at the door. “About the test,” he said. “About, you know, that night. I should have told you when you asked.”

“You should have,” I said.

“It’s just—” He looked like a man searching for the adjective that would make a noun smaller. “I didn’t know, and then once I thought maybe, I didn’t want to…hurt Ethan. Or you.”

“You wanted to protect yourself from the consequences of a possibility,” I said. “That’s different.”

He nodded, chastened for real this time. “I’ll do better,” he said. It wasn’t a vow. It was an idea. Sometimes ideas turn into action. Sometimes they stay flattering sentences. I told him we’d see.

Weeks blurred, but in cleaner colors. I made fewer declarations and more lists. I said no to Noah a lot, and yes to help from people who weren’t charged with loving me but did anyway: the neighbor who took a 2 a.m. shift pacing the hallway with Lily to give me twenty minutes horizontal; the cashier who said “you’re almost there” when I fumbled coupons like confetti. I started eating a vegetable every day. This felt like a revolution and tasted like spinach.

On Thursday nights, when Lily went to sleep early, I read, hungrily, the kind of paperback novels whose spines break in the middle. I liked their clean arcs and endings that had the courage to shut the door. In between chapters, I wrote in a notebook with a red cover: little lists, and some bigger truths. I wrote, “Love is made of verbs.” Then I wrote, “Respect is a verb. Trust is a verb. Showing up is a verb.” I circled verb so many times the paper thinned.

One weekday afternoon, I saw Ethan at the grocery store. He was looking at apples like a man interviewing them for a job. Lily sat in the cart seat staring at him, the way she stared at anything that moved with competence. He looked up and our eyes colluded in remembering. We did small talk. How are you? Fine, fine. Work? Good. He nodded at Lily, who drooled earnestly. “She’s getting big,” he said.

“She is,” I said. There was a longer sentence behind it that I didn’t say: “She is your almost-daughter who is also a real person who will never know the version of me who would have protected the place she would have had in your arms without making you ask.” There is no way to say that sentence without bleeding. So I didn’t.

At the register, as I was loading yogurt onto the belt, Ethan stepped close enough that I could see the tiny scar near his temple I’d always pretended was secret. “I’m seeing someone,” he said, awkward and kind, because he thought it might be worse if I found out from a friend of a friend’s careful voice later. “I wanted you to hear it from me.”

For a second, something hot and childish launched itself in my chest: the wish to be the person someone was not over. But it fizzled; I’d been practicing. I smiled, and I meant it in the exact way I meant it. “I’m glad,” I said. “I hope she’s…right.” I almost said good; how reductive. “Right” felt more accurate, like a angle that finally made sense.

At home, I posted nothing about it. I learned silence where I’d once loved the echo chamber. It turned out the fewer narratives I sold to other people, the more available I was to buy the truth at full price.

The day of Lily’s six-month shots, I cried more than she did. The nurse, the same one who had handed my daughter to the wrong man in that bright room, gave me a look I understood too late. In it was the entire span of the story: the moment she’d seen me look to the wrong person, the way she had watched the room fold around that choice, the way she had placed the baby anyway. She squeezed my shoulder after the Band-Aids. “You’re doing good,” she said quietly. Maybe she meant the sleep schedule. Maybe she meant the whole slog of making myself reliable.

At night, when the city smeared itself across the windows, I’d imagine Lily at fifteen asking for stories about when she was born. I’d pretend to tell her a version of it that made me look brave and her father look unreasonably angry and her biological father look like a man who’d been handed a surprise and rose to it. Then I’d rewrite it. “You were born into a room where the grown-ups didn’t know yet that love isn’t a triangle but a line,” I’d say, in my head. “You taught us. Or we learned because you deserved it. Both can be true.”

If grace is a muscle, mine had finally started getting exercise. It’s a quiet thing, building. It doesn’t make for a fun montage. But one night, when Lily woke at 3:11 a.m., and I was so tired I thought maybe I had only ever been tired in my whole life and all other experiences had been layered illusions over tiredness, I picked her up and kissed the soft folds at her neck and felt, under the fatigue, something like joy you can trust. It was small. I would not have noticed it if it hadn’t been so bright.

Noah texted me a week later: “Can I take her Sunday morning? I got tickets to a thing Saturday night, so I’ll be out late.” I typed, “No. I’m not building her life around your hangovers.” He typed, “Harsh.” I typed, “Correct.” He sent back the thumbs up, which he uses to end arguments he can’t or won’t win. On Sunday morning, he came at 9 a.m. with iced coffee for me and a new pack of onesies he did not need to buy in order to be involved. He was trying—another idea on its way to becoming a habit.

When he brought Lily back at noon, he lingered. “I want to do better,” he said. “I get why you’re…mad. I didn’t want to see it but I do now.” I did not hug him. I did not absolve him. I handed him a small notebook. “Here,” I said. “Write your times here. Make a plan. Then keep it.” He flipped it open like it might reveal a trick. It didn’t. It was paper, lines, patience required, nothing glamorous. He put it in his back pocket like a promise or a prop. “Okay,” he said. “I will.”

The day after that, I met Sophie for lunch. She watched me eat a sandwich with the ferocity of the newly reformed. “You look…better,” she said. “I’m sleeping like a person,” I said. She smiled. “How’s the righteous indignation?” she asked, not unkindly.

“Leaning more righteous, less indignation,” I said. “Learning to channel it into things like laundry and calling my mother.” She laughed. She raised her glass to the baby in the stroller. “To Lily,” she said. “To the best teacher any of us didn’t ask for.”

There is a version of this story where I call Ethan in a moment of weakness and ask for what I can no longer have. There is a version where Noah and I accidentally, irresponsibly, try again for the thing we never learned how to do right the first time. There is a version where I move to a different city and call it a fresh start. The version I am living is smaller and harder and better. It goes like this: I keep Lily alive and loved. I practice boundaries until they become the air my daughter breathes. I tell the truth to myself in paragraphs and to others in short sentences. I let the people I hurt live where I can’t see them, and I stop walking past that window.

This part ends not with a cliffhanger but with the quiet tick of a kitchen clock. It ends with me rinsing a bottle and setting it to dry on a mat that says “home” in cursive. It ends with Lily laughing for the first time at something I did on purpose: pretending to sneeze. I do it again, and she laughs again, like it’s the funniest thing anyone has ever tried. Maybe it is.

Part IV — The Weight of Names

Spring came in impatiently, as if it had somewhere better to be. Trees in our neighborhood sprouted green in a single night, and the concrete outside our building took on that faint mineral smell I’ve always associated with childhood bike rides. Lily learned to sit and then stay sitting; she looked like a pleasantly surprised statue. Her name suited her more every day—delicate on the outside and sturdy underneath, a thing that will bend in a storm and pop back up unbreaking.

On a Tuesday, an envelope arrived in the mail addressed to both me and Noah. Inside were birth certificate correction forms—lines and boxes where the state invited us to tell the truth in ink and then ask some official in a downtown office to ratify it. I sat at the table and stared at the word “father.” It had always looked like an answer. Now it felt like a question that had once had two wrong responses and now had one right one and a whole lot of consequences.

Noah came by that night. He wore a sweatshirt from a band tour that never happened and the expression of a penitent teenager. I slid the forms across the table. He picked one up, smoothed it on the surface like it might wrinkle in its own shame. We filled the forms out together while Lily smacked a spoon into the high-chair tray with the steady seriousness of a judge.

“What do you think about her last name?” he asked, careful, actually curious, not angling for anything.

I breathed. It was a moment where I could have made it about me. “Mitchell” felt like a word I no longer had permission to say out loud. It belonged to Ethan and to the life I’d failed to safeguard. We had options: hyphenate, switch, keep, add. “I want her to have my name,” I said finally. “At least, for now. She’ll know who she is. The paperwork of her life won’t keep changing because the adults around her do. And if someday she wants something different, we’ll listen.”

Noah nodded. “Sounds right,” he said. “I want her to feel steady.”

“Then be steady,” I said before I could soften it. He didn’t flinch. “I’m trying,” he said. And he was. He showed up on Sundays and Wednesdays now, and he did the bedtime routine like it was choreography he could learn and earn. He kept the little notebook. He’d write things like “S: 9-12 boiled pasta / pears” and “W: 4-7 park / bath.” It was so banal it made me ache. This is what I had never quite learned to ask for: the right kind of boring.

When we handed in the forms, the clerk stamped them with a thud that felt like a curtain closing and a new one opening. We walked outside into the bright insult of a sunny day. “Want a coffee?” Noah asked, and it was just a question, not a test or a code for a longer conversation. “Sure,” I said, and we walked two blocks without parsing the moral valence of our choice. In the café, a woman with a baby strapped to her chest smiled at Lily and then at me, and I found myself saying, “This is her dad,” without stumbling over the shape of the sentence. It felt like telling the truth in a complete sentence.

That night, I wrote another list.

Names I will not hide behind anymore:

“Just friends” when the friendship dishonors the person I chose.

“Independent” when I mean “stubborn.”

“Modern” when I mean “inconsiderate.”

“Supportive” when I mean “flattering.”

“Chill” when I mean “conflict avoidant.”

“Sweet” when I mean “I didn’t think about how this would land on the person I promised to center.”

I had always been good at lists. This one did not give me the satisfaction of crossing things off. Instead, it made a strange kind of accountability: every time I wanted to say one of those words, I forced myself to translate.

A week after the forms, Ethan texted. It was the first message from him since the grocery-store disclosure. “Would you be open to me leaving a box of Lily’s things with you?” my phone lit with. “Books, toys I had bought.” I stared at the message until the screen dimmed. I typed yes and then, after a pause, typed, “Thank you.”

He came by two days later at a time we had chosen because Noah wouldn’t be there and because I had gotten brave enough to admit that the three of us in a room—however polite—was an unkindness to everyone. He had a small box. On top lay a stuffed rabbit I recognized from a boutique we’d wandered through during a weekend away when we thought we were buying for a person who belonged to both of us. He put the box down in the doorway. He didn’t step inside.

“I hope she likes them,” he said.

“She will,” I said. “She likes everything soft.” He smiled. I almost said, “She likes men who show up,” but I didn’t, because there are compliments that hurt more than they help.

He nodded toward the stroller in the hall. “Can I—” he started, then stopped himself, the old muscle memory catching on the new choreography. “It’s okay,” I said. “You can see her.” He stepped close and bent slightly like one does to a new planet. Lily looked up at him with the egalitarian curiosity she gave every person. He smiled and did what he had always done better than anyone: he showed up fully for the moment he was actually in. “Hi, Lily,” he said softly. For a second, I saw the ghost of our life where this was ordinary. Then I blinked and saw the life we had. He straightened. “Take care,” he said. “You too,” I said. We were, both of us, doing our best to carry the weight of names without dropping them on each other’s feet.

Summer came like a grant we hadn’t applied for. The park was a mess of sprinklers and popsicles. Noah took Lily on Wednesdays to the farmers market and texted me photos of her in a tiny sunhat I had not authorized but grudgingly approved after the third picture made my sternness melt. He was…better. Not transformed into a different species, just grown into a version of himself I’d stopped believing in. He asked for advice sometimes instead of pronouncing; he said “thank you” a lot. He made a Google Calendar shared with me and color-coded his Lily time. I cried a little the day I saw a whole month filled with little blue blocks.

When I imagined the future, it no longer branched into melodrama. It fanned into simple scenes: a parent-teacher conference where we sat on opposite sides of a tiny table and agreed on more than we disagreed; a birthday party where Ethan, perhaps with his right person, approached to say hello, and we did not look at our shoes; a day when Lily asked about her birth story and I told it without flinching or embellishing—this happened, and this, and then this—and she nodded as if the lesson were obvious: love people in the order you promised.

I had been afraid for months that the story would harden into the only thing about me. It didn’t. It became one more piece in the mosaic of a life that contains other clumsy plots: the time I cut my own bangs, the day I got the job I thought would make me happy and instead taught me how to be bored without being ungrateful, the first time Lily stood and wobbled and then grinned like she had invented verticality.

The last time I saw Ethan that year was in early fall. I was at a street fair with Lily on my hip, sticky with the sugar dust from a fried dough she had no business tasting and every intention of tasting again. He walked past with a woman whose posture read like a good poem: nothing extra, everything necessary. He saw me and paused. The woman turned, and he introduced us with simple nouns. “This is Clara,” he said. “This is Maya.” She smiled, said, “Nice to meet you,” then looked genuinely delighted at Lily’s frosting moustache. “You have a very persuasive child,” she said to me, conspiratorial. I laughed. “She’s lobbying for a second piece,” I said. “She’s got the votes,” Maya said. Ethan looked easy. That was the word. Not ecstatic or lit-up. Not devastated, hollow. Just…easy. It looked good on him like soft blue always had.

We chatted about nothing. Then they moved on, not because we were avoiding pain but because the fair had more to see. After, I found a bench and sat with my heavy, happy baby. I thought about the part of love I had misunderstood for years: that it isn’t a borderless benevolence or a fireworks show you can live in. It’s the way you interrupt yourself to listen. It’s the way you keep your hand steady while tightening a screw, even when you’re frustrated and want to throw the whole crib out the window. It’s the way you don’t invite chaos and then call yourself generous for tolerating it. It’s the way you tell the truth early, when the truth is an inconvenience instead of a detonation.

I licked sugar from my thumb and started to cry the smallest, gentlest cry. Not grief, exactly. Gratitude’s quieter cousin. Lily touched my cheek, fascinated by the liquid. “Water,” I said, smiling. “Mama water.” She laughed as if I’d told the best joke anyone had ever thought to make.

Part V

If you’ve come this far, you deserve an ending that doesn’t hedge. I won’t let the story trail off into mood. I will tell you where we landed, and then I will tell you what it taught me. It’s the least I owe you after asking you to sit with my mistakes.

Lily turned one on a day that pretended to be spring but kept threatening to snow. We threw her a small party in the building’s community room: cupcakes, a banner, the kind of balloons that make you realize you are one static shock away from madness. Noah came early and helped set up chairs without needing to be asked. He had a new habit of narrating his actions to himself under his breath—“Okay, forks, napkins, check”—like someone trying to overwrite an old soundtrack. It worked on me in a way his grand gestures never had.

Sophie arrived with a gift that made me cry: a framed list of “Verbs We Practice,” lettered beautifully in the kind of script that makes you believe in your own handwriting again. Respect. Show up. Listen. Repair. I hung it later over the changing table. Not because I wanted to indoctrinate my child while she pooped, but because I needed the reminder where I couldn’t avoid it.

People we loved came and not a single person I wanted to impress. That felt like an achievement. We sang, and Lily smooshed cake into places cake had never been. There was a moment, near the end, when the door opened and Ethan stood there. He had come by with a small wrapped package and the sort of practiced casualness that says, “I thought maybe this would be okay,” and the sort of eyes that say, “If not, I will leave right now.” We had agreed, vaguely and then explicitly, that this was not his day—and it wasn’t. He only wanted to place the gift somewhere and depart without drama. He glanced around the room and saw what all of us saw: this was not for him. He caught my eye. I nodded a thank you. He set the gift down and left. Later, after everyone cleared out, I opened it. A book, “A Sick Day for Amos McGee”—a story about a friend who shows up. The inscription read, “Happy birthday, Lily. May your people be people who keep their promises. —E.” I cried again, the kind of crying that leaves your face cleaner.

By year two, we were a family of three with auxiliary supports, and the structure held. Noah missed a Wednesday once and did not offer me Venmo as absolution. He showed up Thursday and apologized to both of us. He said to Lily, “I said Wednesday. I did Thursday. Next week, it’ll be Wednesday.” He kept that promise. He sometimes sat at my kitchen table after she went to sleep and asked me questions about her days like a researcher determined to understand a phenomenon. He began dating someone—Sara, with hair the color of late summer—and introduced her slowly, respectfully, without making me narrate my feelings for him as if he were sixteen. she was warm toward me in a way that made me want the best for both of them.

Ethan and Maya married quietly in the fall at a botanical garden I later saw on Instagram. They looked like a postcard people put on their vision boards without irony. When I heard, I took Lily to the nursery that day and we watered our one hardy fern. “We are happy for people who found the right person,” I told her. She splashed water onto the mat and clapped. Good enough.

As for me, I learned how to be alone without crafting performative struggles out of it. On Saturday mornings, I took Lily to the library and did not make a speech about loving books to strangers. I texted Sophie complaints about small things and thanked her for not telling me about her clients’ worse ones. I made a little ritual of calling my mother on Sunday evenings and listening, for once, more than I spoke. I began to understand that apologies are made of two parts: I’m sorry and I’ll change. That the second one has to be the bigger part of the sentence.

Once, about three years in, I saw the nurse from the delivery room at a bakery. She was wearing real clothes, which looked like a disguise. I hesitated, then approached. “You probably don’t remember me,” I said. She laughed. “We remember all of you,” she said. I gestured to Lily, taller and talkative. “You handed her to someone who wasn’t—” I stopped. She put a hand up. “You don’t have to—” “I do,” I said. “I was wrong to ask. I didn’t know, and I should have known, and it hurt someone who deserved better.” She looked at me for a long second that felt like a test and a benediction. “We see people do their best version of the worst thing they’ll ever do,” she said. “And sometimes we see them do better after.” She bagged my croissant and added an extra cookie, like grace.

So, the ending you asked for:

Lily is six now. She reads to her stuffed rabbit in a voice that sounds like she has always lived here. On Wednesdays she runs full-tilt into Noah’s knees and he scoops her like he was born with that motion ready. He is not perfect. He is present. On weeknights I show her on the calendar who is picking her up and where we will go on Saturday, and she trusts the squares and the people inside them. We argue about vegetables. We make up with ice cream. I say “sorry” to her when I am clipped and explain that adults sometimes need naps we don’t take.

Ethan and I run into each other not often and always pleasantly. He once emailed to ask if I had a photo of a particular day—he remembered the light, the laughter—and I sent it without ceremony. Maya once slipped me a note at a school fundraiser that said, “Thank you for being kind about the overlap,” which is the exact right word for so many things. We send them a holiday card that includes Lily in a reindeer sweater. They send one back: a picture of them at a lake, looks of easy contentment I no longer find painful to witness.

As for me, I started dating again without pretending each date was a political act. I turned down a handsome man who bragged about how cool he was with his ex-wife’s new boyfriend because he sounded like a guy who had never learned the difference between tolerance and respect. I went out three times with a teacher who taught middle school science and had opinions on the correct shape of a school lunch. He didn’t own a guitar. It felt promising.

When Lily asks about the day she was born, I tell her the clear story. “I was scared,” I say. “I asked the wrong person to help. Daddy Ethan was late because of traffic but he came. When you came out, I made a mistake because I wasn’t thinking about the promise I made to Ethan and to you. That mistake hurt him a lot. It also—much later—helped us understand who your other daddy is. We are sorry we made such a mess and grateful you are here.”

She nods and says, “And now we have two houses,” like it’s a benefit in a consumer comparison chart. “And many people who love you,” I add. She licks her spoon and says, “You and Daddy and Daddy and Sophie and Sara and Maya,” counting her constellation.

If I could go back to that room, I would put my hand on my own arm and say: He’s your husband. This is your moment with him. Honor it. I would tell the nurse, “Him,” and tilt my chin toward the man who did the slow work of loving me without requiring an audience. I would watch the way his face would soften—not collapse; soften—and I would register it as the gift it was. I would turn to the other man, the one who would become, in the strangest calculus, the father of my child, and say, “Thank you for your help. You can wait outside now.” I would choose the line instead of the triangle. I would draw it in black ink and guard the straightness of it with the ferocity I’ve since learned too late.

But I can’t. So here is what I do instead: I hold the boundaries of the life we have with the same steadiness I once refused. I take the picture of Lily with each of her fathers and place them on a shelf that is sturdy with non-negotiables. I teach her that sweetness is not an excuse for thoughtlessness, that modernity is not a synonym for mess, that respect is the floor, not the ceiling. I tell her that if there is one thing she remembers from the list above the changing table, it should be this: put the people you promised first. Everything else will make more sense after.

And the title you read at the top? I chose it because it is the bluntest version I can stand of what I did. I thought letting my ex see the baby first was sweet—now my husband walked out on me at the hospit—well, you know the rest. The ending isn’t that he left. The ending is that I learned why he had to. The ending is that I learned, finally, that love is a verb, and I say it in present tense or not at all.

Clear enough? I hope so. For your sake, and mine, and a little girl who deserves every adult around her to know the difference between attention and devotion, sweetness and respect, modernity and honor, I hope it’s crystal.

Because endings, the good kind, are not about punishing. They are about understanding, changing, and then living in the new shape without constantly looking back at the outline of what used to be.

That’s what we do now. We live, we show up, we repair. We let the past be what it was—and we don’t repeat it.

News

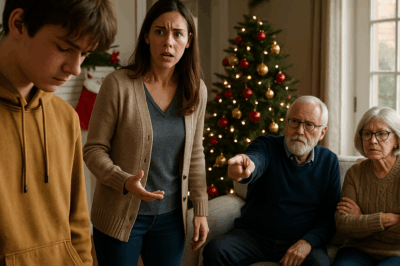

I CAME HOME UNANNOUNCED ON CHRISTMAS EVE. FOUND DAUGHTER SHIVERING OUTSIDE IN 31°F, NO… CH2

Part I I didn’t plan the surprise like a movie. There was no orchestral swell when I turned into our…

My Husband Poured Hot Coffee on My Head in Front of His Mother and Our Son for Refusing to Pay for CH2

Part I I still have the receipt from the night I should’ve known better—curled thermal paper, $8 Uber to a…

Rich Wife Hid A Camera To Catch Her Husband With The Maid… But What She Saw Shattered Her World. CH2

Part I The receipt was not much to look at—cheap thermal paper curled like a leaf left too close to…

My fiancé recoiled when I mentioned morning sickness at our baby shower and loudly announced… CH2

Part I I used to think gift wrap solved everything. It made chaos pretty. It turned a tangle of receipts…

My parents called my son a LOSER and banned him from Christmas… CH2

Part I I was making lists—the kind you make in December when you’re trying to pretend the holidays are logistics…

Locked in a hot storage by husband & MIL. Hospital called: “They’re dead.” But what I saw there… CH2

The Decision That Wasn’t Mine The day my life got small started with a sentence that sounded like a favor…

End of content

No more pages to load