Part I

My mother always said hospitals breathe like sleeping whales—vast, humming, heavy with the weight of lives passing over their backs. Mercy General wasn’t mine—the scrubs were a different blue, the paper charts still clung to clipboards in certain units like relics—but medicine speaks a single language. It was Tuesday evening when the cardiologist told me she was stabilized. Troponins down. Rhythm steady. “You could go home, Dr. Hale,” he added, reading the exhaustion in my eyes like a scan. “We’ve got her.”

I nodded. Three nights in an armchair turned my spine into a stack of misfiled X-rays. I texted Nicole I’d stay till Wednesday, habit more than information, and then—on an impulse that would change everything—I drove.

The interstate unspooled like a sterile drape. Rain freckled my windshield, a surgeon’s hands washing over glass. I stopped at the flower shop on Oak and 7th because that’s what a husband does when he’s a day early and wants to turn a hallway into a surprise. Yellow Gerber daisies—that was our running joke. She called them cheerful. I called them loud. She always won those debates by smiling in that way that made me pick up the thing I’d just argued against.

By 7:30 p.m., Oak Creek’s cul-de-sac looked like a postcard: porch lights flicked on, sprinklers stuttering across squares of American lawn, a dad jogging behind a child on a wobbling bike. Our house—two stories, pale siding, a black front door I’d painted myself—waited at the turn like a patient who still believed in good news.

I eased the key into the lock the way I ease a needle: quiet, precise, invisible. The door swung on a breath. I set the flowers down on the entryway table and saw them immediately: black Converse high-tops, size huge, tongues lazy, laces flung like a teenager’s sigh.

Gavin wears Converse, my mind supplied, efficient and traitorous at once. There were other explanations—Nicole’s brother, a neighbor—but medicine teaches you to read a room before a chart. The house smelled like sautéed garlic and candle wax. From above me, from the direction of our bedroom, came a sound that pulled the floor out from under my ribs: a moan I knew like a signature—but bent, distorted by a voice that wasn’t mine answering it.

I don’t run, not in hallways or on stairs. I take measured steps. That’s what I did—one, two, three—breath steady because that’s what you do when someone is bleeding and everyone else is screaming. The bedroom door was ajar. I didn’t look. I didn’t need to. Their voices floated down like anesthesia wearing off.

“—can’t keep this up, Gav. I’m losing my mind,” Nicole whispered, half-laugh, half-plea.

“Almost over,” he murmured back—a voice I’d heard a thousand times in locker rooms and lecture halls and at my wedding when he toasted us with shameless sincerity. “Once his practice cash flows like he wants, we flip the script. He won’t see it coming.”

“Do you think he suspects?” she asked.

“Michael?” He laughed. “He’s married to his scalpel. And now his mom? Timing couldn’t be better.”

The hallway tilted, the world sliding toward a place where oxygen thins. Eight months—someone said it, I don’t remember which. Numbers are surgical for me; I file them under action. Eight months meant patterns. It meant systems. It meant fraud, not a fling.

I didn’t announce myself. I didn’t slam a door. I walked down the stairs the way I had walked up them and left the yellow daisies facing the black Converse like witnesses at a trial. In the car, the quiet seethed. Grief is loud; rage is colder. It hardens into instruments you can hold.

I took pictures. The shoes. Gavin’s sedan coiled two houses down like a snake that thought our hedges made it invisible. Timestamp. Location. Evidence.

I called Samuel. He answers like a man whose retainer buys availability. “Doc,” he said, voice a gravel road. “Tell me you’re calling for golf.”

“My marriage is septic,” I said. “We need source control.”

He didn’t ask for poetry. “Tomorrow. 9 a.m. Bring anything that connects dots. We’ll start with containment.”

I drove to the Marriott by Mercy because doctors live there on the nights between lives. The clerk didn’t look up when I slid a card across the counter. The suite smelled like neutral soap and the ghosts of other people’s dilemmas. I opened my laptop and did the kind of chart review you only do when the patient is you.

Her Instagram: smiles over spaghetti I’d never tasted in spots I recognized from Gavin’s Yelp rants. Hashtags about girls’ nights that corresponded with Gavin’s “extended call” texts. Photos that pushed the line of flirtation, never crossing it in public, coy as criminals. Then the private folder—cloud synced for convenience, careless enough that my passwords still worked because trust looks like laziness until it’s evidence.

Our couch, my T-shirt on her, Gavin’s hand on her hip. Our bed, the linens I’d picked for durability because doctors appreciate thread counts differently. Selfies with captions that flavored humiliation with logistics. My name popped up like a diagnosis: “He’s so focused on expansion—perfect timing,” Nicole wrote. “Once he signs, the valuation jumps. I’ll file right after.”

Then the text thread that moved from sex to spreadsheets so seamlessly I wanted to scrub my hands: “He’ll keep the debt; I’ll take the liquidity.” “My lawyer says community property will favor me if I claim emotional abandonment.” “Document long hours. Save ‘concern’ texts.”

A doctor should know better than to ignore prodromal symptoms. I scrolled back across eight months of late calls, early departures, the perfume I’d filed under “new,” the nights she said pediatrics ran code gray. I’d set my life to autopilot and now wondered why the plane was off course.

I found Gavin’s Instagram. He was good in public—always had been. Photos with Danielle at charity runs, at her sister’s barbecue, both of them glowing like good people do. Danielle—peds nurse, night shift, the kind who remembers stickers and parents’ names. At parties she asked me about my patients and listened to my answer, not waiting to talk. We’d been the couples you layer on dinner invitations: Reliable. Predictable. Safe.

At 6:40 a.m., I put my scrubs on like armor and drove to Children’s. Danielle’s shift ended at seven. She emerged with hair that had given up and sneakers that told the truth. When she saw me, she smiled automatically, then saw my face and stopped.

“Is your mom—” she began.

“Stable,” I said. “This is about Gavin.”

The cafeteria smelled like burnt hope and syrup. I had printed photos because screens feel like gossip; paper feels like consequence. I watched her study them the way I watch residents read a CT—eyes skipping first, then going back, slower, a dawning shape. She didn’t cry. The good ones don’t at first. They triage.

“How long?” she asked.

“Eight months.”

She stared at the stitched corner of the photo. “What are you going to do?”

“Operate,” I said. “But I’ll need an assisting surgeon.”

Her smile was a cut. “Scrubbed and ready.”

When she told me she was five weeks pregnant, the plan didn’t change so much as it evolved. Purpose is sharper when an unborn heart is in the room. “He knows,” she said flatly. “He told me he was—evaluating his options.”

I’ve heard men say those words in consult rooms when they want time to pretend. Danielle’s face did a thing that made me recalibrate my respect. “What do you need from me?” she asked.

“Schedules. Patterns. Proof.”

She had them all. Nurses understand the architecture of hospitals the way a heart understands rhythm. She knew Nicole’s fake on-calls before I did. She knew Gavin’s favorite lies and when he told them. “They’re doing dinner at your place tonight,” she said, tapping a calendar. “He told me he was on trauma. She told you, what? Staff meeting?”

“Monitoring,” I said. “I told her I’d be back Wednesday. Tonight will be… educational.”

I met Samuel at nine. Divorce lawyers who specialize in physicians understand how to triage assets. We built barriers: trust accounts shifted out of joint names, operating agreements revised to wall off the practice expansion, notifications set if funds moved. “Your state’s weird about recordings,” he said. “But you can record in your own home. No expectation of privacy if it’s your property and you’re not bugging a bathroom. Texts are admissible; don’t hack—use access you already had.”

By lunchtime I had a PI: Harris, ex-cop, hairline retired, eyes still on the job. He installed cams under crown molding, lipstick-sized lenses with time stamps. “You want audio?” he asked.

“Yes,” I said. “But only where it’s legal.”

He nodded like men nod at precise instructions. At five, Nicole called with a voice that had comfort and choreography woven together. “How’s your mom?”

“Stable. They want to watch her overnight.”

“I hate this,” she said. “I’ll make your favorite dinner tomorrow.”

“I can smell it already,” I said and wanted to vomit.

Danielle texted at six: “He left. Said trauma. I said try honesty for once. He kissed my forehead and lied.” The anger in her bubbles didn’t erupt. It calcified.

At eight, Mercy called. “Dr. Hale, your mother’s developed an acute obstruction. Surgery tonight. The general’s on his way. We wanted you informed.” The world narrowed to a point and brightened with pain. Timing is a god with a terrible sense of humor.

I called Danielle. “We execute now,” I said. “Then I go cut.”

“Michael—go to your mom,” she said. “We can do this any night.”

“They used my mom as cover,” I said, hearing how ugly my voice had become. “I’m done letting them write the script.”

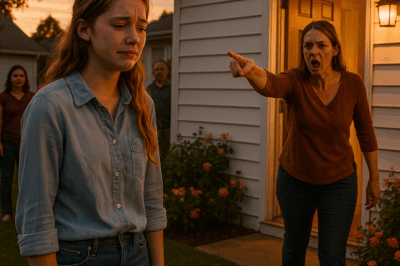

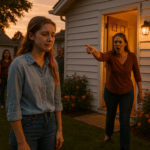

By eight-thirty we were in my driveway. Gavin’s car slept where it always did when he treated our neighborhood like camouflage. Our house glowed in a way that made me want to tear the wiring out of the walls. We stood at the door like the beginning of a parable. Danielle touched her stomach and nodded to no one. “Ready.”

We entered like ghosts. My house smelled like someone else’s romance—citrus candles, garlic, the clean lie of a decanted wine. Music, the kind you put on when you want to pretend taste, drifted from the dining room. I went up the stairs first. I needed to see the bed. Our bed—sheets wrinkled, her robe on the floor, his belt a slash of black. I took the picture anyway. Evidence is a balm when pain won’t shut up.

We met eyes at the bottom step. “On your line,” I whispered.

We moved. The dining room was a postcard from a life that didn’t belong to me: the “good” china we’d saved for anniversaries, strawberries gleaming like punctuation marks, Nicole’s laugh perched on a note it had never used with me. She sat on Gavin’s lap. He looked sixteen and stupid.

“Surprise,” I said.

If humiliation had a scent, it would be the sugar that hit the air when the strawberry dropped. Nicole sprang like she’d been burned. Gavin said a word that wasn’t language. Danielle walked in behind me with a composure that made me want to build a church.

“Michael, I—” Nicole began.

“What are you doing here?” Gavin demanded, but he was talking to Danielle.

She placed the pregnancy test on the table beside a bowl of strawberries with all the dignity of a judge entering a verdict. “That,” she said. “Is why.”

Silence found the room and dragged its chair in. I read from my phone because my hands needed something to hold. “Quote: ‘The more he invests, the more I’ll be entitled to when we divorce.’ Quote: ‘Once his mom’s better, I’ll file. I’ll call abandonment.’” Each line was a scalpel. Nicole’s face cycled through expressions like scans blinking on a light box—alarm, denial, strategy.

“Michael,” she tried. “Please. I can explain.”

“Explain what?” I asked, steady because rage, once chilled, is a form of discipline. “Eight months of lies? A planned exit set to my mother’s heart rhythm?”

“It’s not—” Gavin started.

Danielle turned her head. She didn’t raise her voice. “You told me you were ‘evaluating options’ when I said I was pregnant.”

Nicole’s head snapped to him. “Pregnant?”

He swallowed. “It’s complicated.”

She laughed—a sound I didn’t recognize. “Is it? Because I was under the impression your wife couldn’t have kids.”

Danielle looked at me. We hadn’t planned for their lies to collide. Sometimes truth doesn’t need choreography.

“You said your marriage was over,” Nicole hissed at him. “You said—”

“I said I loved you,” he pleaded. “Both things can be true.”

“Not in court,” I said, laying a file on the table. “Here are copies of everything. They’re also with my lawyer, a PI, and—”

“Michael,” Nicole whispered. “Please.”

“—the City General staff group chat,” I finished.

If shame had a physics, it would have been the way the air went out of that room. Gavin surged to his feet, then sat again, then pressed both palms into his eyes as if he could squeeze the consequences out.

“That will ruin us,” Nicole said, voice small.

“Like you ruined me?” I asked. “You made your choices. I’m informing the people who need to know whose hands they’re trusting in codes.”

My phone buzzed. Mercy. I answered because my mother’s life outranked my vengeance. “We’re wheeling now,” the nurse said. “The attending wants your consent to intubate if needed.”

“I’ll be there in fifteen,” I said and meant it like a prayer.

I pocketed the phone, looked at Danielle. “Coming?”

She nodded, eyes steady. “I don’t trust myself not to break a glass in here.”

As we turned, Nicole reached for my sleeve. “Don’t do this,” she said. “We can fix it.”

“You fixed it,” I said. “You just forgot to tell me what you repaired it to.” I pulled away. “Papers tomorrow. Keys tonight.”

By the time we hit the driveway, yelling began behind us—blame ricocheting off walls, the sound of two people realizing the other person couldn’t carry their version of the story. In the car, Danielle held the test with both hands the way people hold photos of the dead and the unborn.

“Did you really send it to the group chat?” she asked finally.

“All of it,” I said.

“What if they… do something?”

“With what?” I asked. “The truth?” Outside, the city flickered. Inside, purpose took the wheel from pain.

At Mercy, I scrubbed in. My mother’s abdomen lay prepped under the lights, her face a patient’s face now, not my mother’s. The attending nodded at me with the courtesy professionals give each other when something naked is about to happen. “You okay?” he asked.

“Not even a little,” I said.

“Good,” he said. “That’s when we do our best work.”

We opened. We relieved. We stitched. My hands did what they’ve always done—find the thing trying to kill someone I love and remove it without killing the body in which it grew. When we were done, when she was settled in the ICU with a tube breathing for her and numbers marching down the monitor like soldiers I believed in, I sat in the quiet. The whale of a hospital breathed around me.

I texted Samuel: “Proceed.”

I texted Harris: “Pull the files.”

I texted Danielle: “How are you?”

She replied with a photo of a vending machine brownie and a thumbs-up. We were, somehow, allies with sugar for supper.

At three a.m., I walked out into an empty parking garage that smelled like rain and cold metal. In the stillness my phone lit up with the notifications I had asked for and dreaded: a cascade of messages from nurses, attendings, residents, those who made our hospitals run. Some expressed sympathy. Some fury. Some just the thin, clipped syntax of people who have to be at work at five and don’t have time for anything but facts.

Truth, released into the world, is not a boomerang. It doesn’t return. It keeps going, finds rooms you didn’t intend, does the damage you meant and some you didn’t. It’s not clean. But it is a kind of antiseptic.

Somewhere, in my house, the candles would be guttering out on a table set for a romance that had mistaken my life for a set. I closed my eyes and let the image pass. You can’t fix the past. You can only cut around it.

At dawn, the cardiologist texted me a photo of my mother’s hand squeezing his finger—proof of something far more important than vengeance: survival. I exhaled a breath I’d been holding since Friday night.

The sun came up like a sterile light turned on over a field you have to cross. I started walking.

Part II

The sunrise came up the color of scrub caps, flat and practical. I signed the last ICU order set, squeezed my mother’s hand, and let the ventilator do its slow, patient work. When she blinked at me through the sedation, I lied the way doctors lie when it’s kinder. “You’re okay,” I said. “Sleep.”

Samuel met me at his office at eight sharp. Divorce lawyers who live off physicians’ crises run their practice like an efficient trauma bay: triage, stabilize, cut, close. He had coffee I didn’t need and a yellow legal pad already bleeding black ink.

“We file today,” he said. “Petition, request for exclusive use of the home, temporary orders. State ATROs kick in at service—no transfers, no cash-outs. Your practice we already insulated yesterday, but this makes it judicial.”

He slid forms across the table. I signed like a man closing fascia.

“And the evidence?”

I opened the folder Harris had compiled overnight. Time-stamped photos. The text transcripts. A diagram that looked like a case presentation: eight months of overlapping schedules and matching lies. Harris added a one-page memo, the kind of police prose that makes juries lean forward: “At approximately 2000 hours, Subject A’s vehicle observed two residences down. 2035 hours, Subjects A and B in residence. 2110 hours, confrontation initiated by Client and Subject D (Danielle). Admissions made.”

Samuel paged, frowned, nodded, paged again. “It’s… neat,” he said. “Judges like neat.” He tapped the line where Nicole had texted about waiting to file until I’d expanded. “This reads like intent to defraud. It’s not a business case—I can’t promise the DA will care—but in family court it lands.”

“Service?” I asked.

He smiled without smiling. “Already in motion. Process server will find her at 1300. At the house.”

The house felt like a patient I’d discharged too early. I didn’t go. I drove to City General because that’s where consequences go to be measured. My text the night before had set off exactly the chain reaction I’d intended and dreaded. There are lines we don’t cross in medicine, unwritten and iron: don’t abandon patients, don’t falsify time, don’t weaponize on-call. Affairs aren’t an HR category until they bleed into those.

Compliance emailed me first. “Dr. Hale, thank you for bringing forward information that may relate to scheduling integrity. Please refrain from further distribution while we review.” Translation: we saw it, screenshot it, and now Legal owns it.

Then Staffing: “Can you confirm the dates Nicole claimed extra shifts? Which of these match her official log?” The attached spreadsheet was a map of lies. Danielle had already entered notes. Where Nicole had written “ED overflow call,” the ED charge nurse wrote, “We were light that night; we sent staff home.”

At ten, the Chief Nursing Officer called. Her voice was that firm nurse voice that calms chaos and frightens surgeons. “Dr. Hale, we placed Nicole on administrative leave this morning pending an internal investigation. This is not a judgment on her personal life. We will look into scheduling and documentation.”

“And Gavin?” I asked, hating that my mouth had to move around his name.

“As he’s medical staff, that’s under the purview of Medical Executive Committee,” she said. “I’ve already notified them.” Her tone added a silent clause I didn’t need spelled: and I am personally furious.

By noon, the predictables began. A text from Gavin, the tone his patients loved, smooth and sincere. Brother. This is out of hand. Let’s meet. Don’t nuke careers. Think about Danielle. Think about optics. We can fix this without scorched earth.

I typed, deleted, typed again. Optics are what got us here, Gavin. Facts are what get us out. Do not contact me again.

A voicemail from Nicole, tears like water in a sink with a slow drain. “Michael, please. We can talk. I panicked. I—last night wasn’t what it looked like. It was goodbye. I love you.” She had always been good at finding the right line for the audience. I let the message sit unplayed a second time and forwarded it to Samuel.

Danielle’s text was different. No drama, just a photo from the OB’s office of an ultrasound no bigger than a thumbnail. Heartbeat, she wrote. Strong. Underneath she added, I’m okay. You?

Holding, I wrote back. We were two clinicians charting our day.

At 12:55 p.m., Harris texted a photo of our porch. The process server, a man with forearms like history, stood at the threshold facing Nicole. She opened the door wearing one of my T-shirts the way thieves wear uniforms they stole. He handed her the packet. Her face moved through denial to calculation to anger, the stages of grief in the time it takes to sign for certified mail. In the background of the frame, the daisies still stood on the entry table like witnesses who hadn’t gone home.

At 1:17 p.m., the locks changed. A locksmith in a blue polo shirt arrived in a van I’d called in that morning. He worked fast because trades that deal with panic learn to move. He handed a set of new keys to Harris, who handed them to me in the hospital lobby like chain of custody. “You want me to pop the garage too?” he asked.

“Yes,” I said. “And the alarm code.”

Nicole’s next message came at 1:25. You changed the locks? Are you kidding me? I have rights. You can’t—

Samuel replied from my phone with the dry voice of a statute. Exclusive use granted ex parte pending hearing. Your counsel will receive copies. Please arrange a time to collect personal items with third-party present.

By late afternoon, the ripple at the hospital became a wave. HR asked me to come in—not as a target, but as a witness. I sat in a glass conference room with a view of a parking lot where residents paced their calls. The HR director, a woman who had seen every version of human mess that hospitals breed, asked crisp questions. Did I have reason to believe Nicole claimed hours she didn’t work? Yes. Did I have documentation? I slid the spreadsheet forward. Did I know whether Gavin had billed for any consults during those times? I didn’t. It wasn’t my lane. She nodded, wrote, thanked, told me not to discuss the matter, and meant, We’re going to handle this now that you’ve forced us to.

I walked out past a knot of nurses outside the elevators. Conversation fell the way conversation falls in cafeterias when the trauma surgeons sit down—hard, guilty, relieved. A charge nurse I’d known since residency touched my forearm. “I’m sorry, Dr. Hale,” she said. “If you need anything—extra coffee, sticky notes, a room to yell in—we have you.”

“Sticky notes,” I said, surprised that my mouth could make a joke. “Always.”

On my way to the garage, I saw Gavin across the lobby. No white coat. Hands in pockets. The kind of tired that money can’t fix and excuses can’t dress. He approached like a man on a narrow bridge. “Michael,” he said.

“Don’t,” I said.

He stopped a respectful eight feet away, like there was an unwritten isolation precaution between us. “You’ve made your point.”

“I didn’t have a point,” I said. “I had a spine I finally used.”

“I never meant to—”

“You meant it,” I said. “You wrote it down.”

He swallowed. “The group chat—”

“Was the only language you understand,” I said. “Other people’s judgment. Now you get to learn mine.”

He nodded like someone accepting a diagnosis. “Danielle’s pregnant,” he said, as if I hadn’t been there, as if I had to hear it from him to make it real. His voice cracked, and for a second I saw the kid I met in gross anatomy, the one who helped me catalog a hundred cadavers and made jokes about names we never used. Then I saw the man he’d become, and the pity died. “I’m going to do right by the baby,” he added because that’s what men who have already done wrong say.

“Do right by her mother first,” I said. “Start by admitting to HR what you did here.”

He flinched. “Lawyers—”

“Use them,” I said. “You’re going to need them.”

That night I slept three hours on my office couch with a white coat as a blanket. It felt right—half penance, half practicality. At 5 a.m., I scrubbed in for a hemicolectomy, and the opening incision stilled the useless parts of my mind. There is a mercy in doing something you cannot pretend about. Bowel is bowel. Bleeding is bleeding. You fix what you can reach.

By noon, HR had moved from inquiry to action. Nicole’s badge access revoked. Paid leave pending outcome. Gavin’s privileges placed under review by MEC; his elective cases reassigned “for patient continuity.” The memo was sterile and devastating. I didn’t gloat. It felt like watching a car you once owned get totaled in a wreck you didn’t cause but could map in your head.

At three, Danielle and I met at a diner that knew our faces from night shifts and bad months. She ordered pancakes because grief makes people want breakfast at wrong hours. I ordered whatever was fastest.

“My OB says everything looks good,” she said. “They moved my prenatal to Tuesdays. You don’t have to come.”

“I want to,” I said, surprising myself with the truth of it. “If you want me there.”

She studied me the way nurses study doctors—looking for the cracks behind competence. “I don’t want to be a rebound,” she said plainly. “For either of us.”

“You’re not,” I said. “You’re… someone who didn’t flinch when the ceiling came down.”

She smiled without showing teeth. “High bar.”

We built practical things between us: a spreadsheet for when I’d check on her after night shifts, a list of OB questions that didn’t feel dumb if we asked them together, a way to keep each other from making late-night calls we’d regret. Respect is a quiet house; we moved furniture into it.

The hearing for temporary orders took place two weeks later in a courtroom that smelled like paper and patience. Nicole arrived with a lawyer who wore sharp shoes and an expression dulled by familiarity with this theater. She didn’t look at me until the bailiff called our names. When she did, her eyes were not soft anymore; they were an argument.

Samuel spoke like a man who had already rehearsed in front of a mirror and then cut half his lines. He presented the texts, the transfers, the timeline. Nicole’s counsel tried to reframe, to suggest my hours away constituted abandonment. “He chose work over marriage,” she said.

“I am a surgeon,” I said when the judge asked if I wanted to respond. “When people call me at two in the morning, they are bleeding. I answered. I thought my wife understood we were both in the business of keeping people alive.”

The judge—sixty, hair that said she had canceled more than one vacation for a docket—studied the file. “The automatic restraining orders remain,” she said. “Exclusive use of the residence to Petitioner pending trial. Respondent may retrieve personal items with law enforcement escort. Temporary spousal support reserved given the competing allegations—this is not the time. We are not trying your marriage here. We are preserving the estate.” She glanced at the printouts. “And, Ms. Hale, if the text messages are authenticated at trial, the court will consider dissipation. Be advised.”

Outside, Nicole caught my sleeve with the gentlest of fingers. “Michael,” she said, and for a second she looked like the woman who had danced with me in socked feet in a kitchen with no chairs. “You are not a perfect man.”

“I never said I was,” I said.

“You were absent,” she said, a flare of the old grievance. “For years. You married your work and expected me to applaud from the balcony.”

“I expected you not to set the house on fire,” I said, and let the bailiff open the door for her.

Gavin texted once more that week. I’m in therapy, he wrote, as if absolution could be notarized. I’ll sign whatever Danielle wants for support. Please ask her to answer my calls. I forwarded it. Danielle sent back a single line: My lawyer will respond. The softest people learn to speak steel when the room requires it.

Mom came home to my house the next Friday. I set up a hospital bed in the downstairs den because stairs were still a mountain and pride is a lousy nurse. She took one look at the daisies on the table and the new deadbolt and decided, in the way mothers decide things, not to ask questions until I was ready to answer them.

“I made soup,” she said, wisely lying. My mother’s soup comes from a takeout container with the label peeled off. We ate in a quiet that wasn’t strained. When she finished, she put her spoon down and said, “You look like a man who didn’t sleep.”

“I’m okay,” I said.

“I didn’t ask if you were okay,” she said. “I said you looked like you didn’t sleep.”

The story came out in blunt instruments: shoes, voices, texts, locks. She listened with a face that had seen all my faces—the toddler who broke his arm falling off the porch, the fifteen-year-old who lied about a B minus, the twenty-three-year-old who thought he’d failed out of anatomy when he hadn’t. When I finished, she sat back and let the air settle.

“You did not throw a chair,” she observed.

“No.”

“You did not break a plate.”

“No.”

“You called a lawyer.”

“Yes.”

“Good,” she said. “Revenge is fireworks. Justice is daylight.”

The hospital’s investigations moved with dull, predictable speed. Nicole resigned before they could terminate her; the letter was tasteful and vague. The rumor mill added the adjectives it needed. Gavin took “voluntary leave to attend to personal matters,” a phrase that means everyone knows and no one is saying it out loud. When he came back, it was to a clinic slot in a satellite location where the administration could keep eyes on his charts. The OR rarely saw his name; the MEC has a long memory and a short leash.

The Friday after Mom moved in, I returned to the house at dusk and found the porch light out. The motion sensor had tripped to darkness as if the house wanted to see how I walked when I couldn’t see where I was going. I fumbled in the pocket for the new keys and heard footsteps on the walk. Danielle. A paper bag in her hand and a look on her face I had learned meant, I made something and then decided I didn’t trust it, so I brought it anyway.

“It might be edible,” she said, handing me banana bread shaped like apology. “I shouldn’t be near ovens past six anymore.”

“You okay?” I asked.

“I threw up on a resident,” she said. “He thought I was crying, and I let him think that because it got me out of charting.”

We stood on the porch, two people who had learned how to be in each other’s orbit without mistaking kindness for obligation. Inside, Mom called my name with the particular volume mothers use to summon grown children who should know better. Danielle smiled. “Go,” she said. “I’ll see you Sunday. Ultrasound.”

“Sunday,” I said.

At midnight the phone rang with a number I didn’t recognize. I let it go to voicemail and then, against my better judgment, listened. Nicole’s voice, quiet, sober. “I signed the acknowledgment of service,” she said. “I’ll have my lawyer contact Samuel. I—” A pause, and the old practiced breath. “For what it’s worth, I did love you. I just… I think I loved being chosen more.” The click at the end sounded like the end of something that had needed to end for a long time.

In the morning, I made coffee strong enough to file metal. I sat at the table and opened my laptop to a new patient list, a new accounting software password, a new normal. It didn’t feel heroic. It felt like flossing after a crown—what you do to keep the thing that hurt from breaking again.

Justice, I was learning, doesn’t arrive all at once. It’s paperwork and passwords and people deciding in rooms you’re not in whether your truth meets their threshold. It’s telling your story enough times that your mouth gets bored of the pain and starts editing for clarity. It’s banana bread on a porch and your mother stealing your blankets because she’s cold.

It’s daylight. It’s enough.

Part III

Sunday morning clinics smell like lemon cleaner and second chances. I signed in at the OB front desk as “guest,” wrote “friend” in the relationship box because there isn’t a line for co-survivor, and sat beside Danielle under a print of a cartoon stork that had never met a night shift.

“Ready?” she asked.

“No,” I said. “Yes.” Both true.

The sonographer dimmed the room, measured without ceremony, and then tilted the probe with the practiced patience of someone who brings good news for a living. The screen flickered, a gray peanut in a black ocean. Then sound—a fast, insistent clatter—filled the room. I’ve listened to a thousand monitors. I know rhythms. This one was new. 162. Not mine. Not hers. A third tempo.

“It’s real,” Danielle whispered, even though we could hear it.

We didn’t hold hands, but we could have. We let the sound run through us and change the temperature of the air. I felt something I hadn’t felt in months, maybe years: moved. Not moving on—checklists and locks and filings have their own mechanical dignity. Moved is different. It rearranges furniture you thought was bolted to the floor.

After, we sat in the parking lot under a tree that was trying to be spring. “I don’t want you to be my solution,” she said. “Or me to be yours.”

“I know,” I said. “But I want to be at the anatomy scan. And I want to be the person you text when a resident mistakes morning sickness for heartbreak.”

She snorted. “Deal.”

By Monday, discovery was a machine. Samuel’s paralegal, a woman who could have run a NASA launch and a bake sale at the same time, emailed me a list that made my accountant faint: five years of bank statements, retirement contributions, practice P&Ls, mortgage amortization. “We give them everything,” Samuel said. “We want to be the adults in the room.”

Nicole’s side asked for the same—and for “documentation of any extramarital relationships,” a line that would have made me laugh if I weren’t tired. “Respond: none,” Samuel said, his pen ticking like a metronome. “The irony is not lost.”

Harris kept digging. He found Venmo transfers with emojis that looked innocent unless you knew that “leaf” meant hotel and “pizza” meant Uber from my driveway at 1 a.m. He found a second phone line on our home internet bill, activated eight months ago. He found a self-storage unit in Nicole’s name where the inventory, according to the rental agreement, read simply: “household goods.” We opened it with a warrant for curiosity: my old med school hoodie, a box of china we’d never used, a file box labeled “Plan” that contained… hangers. She had been staging an exit. Or maybe just practicing.

Depositions were scheduled for a Thursday in a conference room that smelled like coffee and paper cuts. A court reporter in a ponytail set up under a fluorescent light like an altar. Nicole sat on one side with her counsel. I sat across from her with Samuel and a pitcher of water we ignored. She had done her hair in the way she did when she wanted to look less like Nicole and more like an argument: soft waves, no sharp angles.

Samuel started easy. Name. Address. Occupation. Years married. No children. “Do you contend your husband abandoned the marriage for his work?” he asked, voice neutral.

Her lawyer objected to form like a metronome. “You can answer if you understand.”

“I contend he wasn’t present,” she said. “We were roommates.”

“During the eight months at issue,” Samuel said, sliding Exhibit 3 across, “can you identify occasions when you and Dr. Hale engaged in marriage counseling or made a plan to address your concerns?”

Objection. Answer: “We talked.”

“Exhibit 7,” Samuel said, dropping the transcript of her messages with Gavin on the table. “In this text you wrote, ‘Once he signs the expansion, I’ll file. He’ll be left with the practice debts; I’ll take half the liquid.’ Was that your plan?”

Nicole’s eyes flashed. “I was venting.”

“Was it your plan?” he repeated.

“I was… angry.”

“Was it your plan?” he said a third time, the way I ask residents where the bleeding is.

She looked at me then, not at the paper. “You never came home,” she said, as if that could move a decimal.

Samuel didn’t let the narrative escape. “We can stipulate Dr. Hale is a surgeon. That’s not a defense to premeditated dissipation.” He turned a page. “Did you transfer $28,500 from the joint savings account on March 3rd?”

Objection. “Answer.”

“Yes.”

“To a separate account in your name only?”

“Yes.”

“For what purpose?”

“Protection,” she said. “I thought he’d hide money.”

“So you hid it first,” Samuel said, not asking.

Her lawyer leaned in. “My client was safeguarding her share.”

Samuel nodded like he’d expected that play. “And the part where she intended to saddle him with business debt while taking liquid assets—were you safeguarding, Ms. Hale, or strategizing fraud?”

Nicole’s mouth tightened. “I wanted out,” she said. “And I didn’t want to be poor for it.”

We broke for ten minutes because the court reporter needed to stretch her hands, and maybe because the room needed to remember itself. In the hall, Nicole touched the wall and breathed like a runner. She looked at me, really looked, and said quietly, “You humiliated me.”

“You humiliated yourself,” I said. “I just turned on the light.”

Gavin’s deposition came after lunch. He arrived in a suit he hadn’t had tailored yet and a tie that looked like contrition. He tried to be affable. It’s a skill. He’d given versions of this face to a hundred families in trauma bays.

Samuel didn’t take the bait. “Dr. Sloane,” he began, “did you bill for any consultations on dates when you were at my client’s residence?”

Gavin deferred to “I’d need to check records,” then looked at his attorney, who was sweating in new ways.

“Were you aware Ms. Hale claimed extra shifts that did not appear on official staffing logs?”

“I did not review her schedule.”

“Did you encourage Ms. Hale to time the filing of divorce to coincide with Dr. Hale’s practice expansion?”

Objection, calls for speculation. “Answer if you know.”

He hesitated. “We talked about it.”

“You texted, ‘Once he signs, he can’t unwind the debt.’ Correct?”

He nodded.

“And when Danielle told you she was pregnant, you responded that you were ‘evaluating options.’ Did any of those options include ending your affair with Ms. Hale?”

Silence. Then: “No.”

“Did any include telling your wife the truth?”

He stared at the pitcher of water like maybe it held better answers. “Eventually,” he said.

“Eventually is not a time,” Samuel said. “It’s a hope.”

Gavin’s lawyer advised a break. The court reporter blinked, grateful. We stepped into the hallway where a copy machine hummed the world’s most indifferent song.

“That group chat,” Gavin said, not asking.

“I regret that it had to be public,” I said. “I don’t regret telling the people you and Nicole used as alibis that you used them.”

He winced. “I’m paying for it,” he said. “Career. Reputation. Everything.”

“So am I,” I said. “With the part of me that thought you were my friend.”

He nodded, a man subtracting the last column in a long ledger. “Danielle okay?” he asked, as if by earning the right to say her name he could make the air more breathable.

“She and the baby are fine,” I said. “You’ll hear from her lawyer.”

Two days later, three couples from our old Friday group invited me to a dinner that was very specifically not billed as a dinner party. “Just burgers,” Ethan texted. “Kids making a mess. Come if you want. No pressure.” I went because avoiding ghosts doesn’t make them less dead.

We stood around a grill while Ethan flipped meat and didn’t look at me too often. “We didn’t know,” he said finally. “I mean, we thought—nobody’s marriage is perfect—you work a lot—but… We didn’t know.”

“You wouldn’t have,” I said. “They were good at timing.”

His wife, Priya, handed me a beer and spoke like a woman tired of men rounding pain to the nearest number. “We saw things,” she said. “We just didn’t name them. That’s on us.”

Inside, their toddler dumped a basket of blocks on the dog and the dog forgave him immediately. Watching that uncomplicated absolution made me ache with the kind that isn’t self-pity, just human.

On my way out, Priya squeezed my elbow. “If you ever want to show up with takeout and eat it in loud rooms so your head stops narrating,” she said, “we’re here.”

At the practice, Abby—my office manager who’d kept me upright through two EHR transitions and a burst pipe—stuck her head in with a stack of coded claims and said, “We’ve got our month back, boss.” Then she gestured to the lobby. A bulletin board I hadn’t noticed before had been colonized by notes from patients and families: thank-yous, a photo of a kid I’d taken an appendix out of holding a soccer trophy, a construction-paper heart from a second grader who’d written Thank you for saving my aunt in aggressive marker. I read until the words turned to shapes. Moving on is bank reconciliations and staffing plans. Being moved is a crayon heart on corkboard, and it got me.

Nicole’s negotiation arrived disguised as peace. Her lawyer emailed Samuel a proposal with the tone of a white flag: she keeps the house; we agree to an NDA about “marital issues”; she waives spousal support; each keeps their own retirement; she returns half the cash she’d moved.

“She wants the house,” Samuel said. “She thinks you need confidentiality more than she does.”

“I don’t,” I said.

Samuel nodded, unsurprised. “Counter: you keep the house. You buy her out of half the equity, minus the cash already dissipated and the legal fees attributable to her conduct. No support. Mutual nondisparagement but no NDA that muzzles the truth we’d prove anyway.”

We sent it. The reply came back in hours, indignation dressed as professionalism. She wouldn’t agree to any clause that “cast blame.” She wanted the “narrative neutral.”

“The narrative is in exhibits,” Samuel said, writing Decline so neatly it looked typed. “We’ll see them at mediation.”

A week later, a text from an unsaved number pinged at 11:27 p.m. If you let me stay in the house through the school year, it read, I’ll make sure Danielle never hears from me again. The manipulation was clumsy, last-minute cram style. I didn’t respond. The next morning, Nicole’s counsel sent a chastising follow-up about “inappropriate direct contact.” I forwarded both to Samuel. He replied on the record: “Please counsel your client regarding ex parte communications.”

Mom got stronger. The walker gathered dust. She reclaimed the upstairs guest room with the imperious joy of a woman who has decided to recover on her own schedule. One afternoon, I caught her reading depositions at the kitchen table, which I hadn’t specifically left there but hadn’t specifically hidden either. She wore her glasses low and her judgment high. “Seventeen times,” she said without preamble.

“What?”

“That man said ‘eventually’ seventeen times. I counted.”

I laughed despite the bruise. “Eventually is not a time,” I said.

“It’s a fairy tale,” she said. “We live in clocks over here.”

Danielle’s second prenatal appointment fell on a weekday afternoon. I rearranged two post-ops and went. The waiting room had other versions of us: couples not looking at their phones so they could pretend patience; teenagers practicing bravery; a woman in scrubs charting with one hand and holding her belly with the other. When the midwife asked, “Support person?” and glanced at me, Danielle answered before the pause could turn into definition. “Yes,” she said. “Friend.”

On the way out, she stopped at a rack of free pamphlets: nutrition, sleep, coping with nausea. She took one on “building your village” and rolled it in her hands like a baton. “I keep thinking I should be stronger alone,” she said.

“You are strong,” I said. “You’re not alone.”

She looked at me then with an expression that made the building feel more anchored. “That’s the difference, isn’t it?” she said. “Not being alone because you can’t manage. Not being alone because you don’t want to.”

We didn’t kiss in parking lots. We didn’t make vows we couldn’t keep. We made a calendar invitation for the twenty-week scan and a note to bring crackers to keep her stomach settled. That was enough. More than enough.

Mediation landed on a humid Tuesday. A retired judge sat between us like a referee at a sport nobody enjoys. He started with a speech about dignity and compromise and how jurists are just plumbers for broken promises. Nicole spoke first through her lawyer: hurt, neglect, an empty house, dreams deferred. I didn’t interrupt because the story people tell themselves is the last thing they’ll surrender.

Samuel went second: facts, exhibits, numbers, the law’s indifference to poetry. At hour three, the mediator rubbed his forehead and said to Nicole’s side, “I can’t make him pay for your plan. You can either take a fair buyout or we can spend a year teaching a court words it already knows.”

In the caucus room, Samuel asked me what mattered most. “Not the bed,” I said. “Or the plates. The house—not because it’s a trophy. Because it’s where my mother can climb the stairs she nearly died under. And because the daisies looked good on the table, even if they were lying when they did.”

We settled that afternoon in a document stack that felt like closure’s scaffolding. I kept the house; I bought her out at a number scrubbed of her withdrawals. She kept her retirement and the car; no spousal support; mutual non-disparagement that didn’t gag the truth but spared us both from turning holidays into campaigns. The judge would sign it in due course. Eventually, as my mother would say, was now a date.

On my way home, I stopped at the florist on Oak and 7th and bought daisies because spite can grow into something else if you water it right. I set them on the same table where the black Converse had looked like an omen and stood there long enough to let the ghosts adjust to the furniture.

My phone buzzed. Danielle: a photo of a hand on a book titled The Sh!t No One Tells You About Pregnancy and, next to it, a note in her meticulous nurse handwriting: “20-week anatomy 9 a.m. You’re on banana bread.” I texted back a picture of the daisies and wrote, “House smells like lemon cleaner and second chances.”

That night, after the dishwasher did the small work of absolving plates of their day, I sat with my mother and watched some crime show where detectives find answers in unlikely places. Halfway through, she lowered the volume and said, “You know the thing you did right?”

“Locks?” I said.

“Soup,” she said, which is to say: not throwing chairs. Calling a lawyer. Not letting a man with an eventually ruin your right-now.

“Daylight,” I said.

“Daylight,” she agreed. “And the part where you let yourself be moved again.”

We finished the episode. The fictional killer confessed. The fictional justice felt neat. Ours wasn’t. But it was working. Slow. Real.

Outside, the porch light stayed on and no one came up the walk who didn’t belong there.

Part IV

Judges don’t bang gavels in family court, at least not in ours. They initial, they staple, they move the stack to the right. It’s quieter and more final somehow, like a surgeon tying the last knot and stepping away.

The decree came back on a Thursday that smelled like rain and copier toner. Samuel texted a single line—“Entered.”—and a photo of the top page with the stamped date. I sat in my office with the blinds half open, the kind of afternoon sun that makes dust look like a constellation. The words didn’t shout. They didn’t forgive. They just sat there, official and unromantic, the paper version of a door closing.

“Congratulations?” Abby said from the doorway, cautious like you approach a sedated tiger.

“Not the word,” I said. “But thank you.”

She nodded, set a stack of claims down like they were ballast. “We’ve got payroll covered for expansion, by the way. The numbers are good.”

It turned out the numbers were good everywhere that mattered. The decree tracked the settlement we’d built in mediation: I kept the house; I bought out Nicole’s half of the equity—less the withdrawals she’d made in the months of theater. There was no spousal support; each kept our own retirement; mutual non-disparagement with a carve-out for legal proceedings and truth, a phrase that still felt radical. In the findings, the judge wrote one dry paragraph that mattered more than it sounded: “Evidence supports inference of intent to dissipate community assets coincident with contemplated dissolution.” Lawyers call it dicta. It’s the court saying, We saw what you did, in a way courts can.

The trial that never happened lived inside the decree as a ghost. We didn’t parade exhibits for strangers. We didn’t cross-examine heartbreak. We made a deal with daylight. It was enough.

The sheriff’s escort day came and went with less drama than the movies promise and more quiet than I expected. Two deputies stood in my foyer with the kind of practiced boredom that can de-escalate a bomb. Nicole walked through rooms that still remembered her and pretended not to. She wore running shoes and a ponytail like she was checking out of a hotel.

“This is ridiculous,” she murmured to one deputy when I asked Harris to open the garage. The deputy didn’t answer. The law is a mirror if you let it be.

She took clothes, framed photos, a stand mixer we’d used twice. The china stayed because I had the receipt and the receipt told a better story than the speeches either of us could make. In the entryway, she paused in front of the daisies and I had the disorienting urge to apologize for how good they looked there.

“I loved you,” she said without turning her head.

“I know,” I said. “Some of the time.”

She blew out a breath that might have been a laugh in a different life. “You loved work.”

“And you loved being chosen,” I said. It landed not as an accusation but as an autopsy finding. Facts are quieter than grief but they’re harder to argue with.

She left with a cardboard wardrobe box and a look back that didn’t ask for anything. The deputies nodded. Harris locked the door. The new keys felt less like a victory than a responsibility.

Upstairs, my mother stood at the landing with a folded blanket, looking not down at Nicole but at me. “How hungry are you?” she asked. Her version of mercy is soup and a couch you can fall apart on. We ate in front of a cooking show where a man in an immaculate apron kept saying “a kiss of heat” and “a whisper of lemon” as if ingredients could talk you out of bad choices.

When the episode ended, Mom pushed her bowl away and said, “You did it right.”

“I feel like I lost,” I said.

“You did,” she said. “People do in divorces. But you didn’t lose yourself, and that’s rarer than you think.”

The hospital did what hospitals do when mess reaches the administration: issued sterile memos that read like weather reports. “Nicole Hale has resigned from her position effective immediately to pursue other opportunities.” “The Medical Executive Committee has concluded its review of Dr. Gavin Sloane’s privileges. Elective surgical scheduling will be temporarily suspended; clinic duties continue at Satellite North.” Those of us who speak fluent hospital understood the verbs. Resigned means asked to leave with paperwork. Temporarily suspended means we don’t trust you right now and we want it on record that we don’t.

A week later I ran into the Chief Nursing Officer in the elevator. She pressed the button for “L” like she owned gravity. “We’ve plugged the holes,” she said without preface. “Scheduling. Sign-offs. Documentation. If it makes you feel better.”

“It doesn’t,” I said. “But thank you.”

“Next time,” she said, and her eyes were tired in a way that had nothing to do with me, “tell us before the group chat.”

“Next time,” I said, and hoped there wouldn’t be one.

Gavin transferred two months later to the county hospital across the river. The public sector is full of good people doing impossible work on too little sleep; it’s also where reputations go when they can’t pass through the doors they used to open. I heard from Ethan he took the pay cut without complaint. I heard from Priya he showed up early for call and stayed late for a kid with a ruptured spleen. Both can be true. Consequences don’t make a person a villain. They also don’t make them my friend.

The Friday group found its new orbit. Burgers and toddlers and dogs who forgive everything continued. Nobody told the story if I didn’t. When somebody did ask because they were moving through their own private storm and needed a map, I told them three things: call a lawyer before you call your mother; don’t break anything you’ll regret buying again; put your phone down when you want to send the text that will feel good for twelve minutes and make the morning heavier.

The practice expanded without the drama Nicole and Gavin had bet against me with. We didn’t buy the bigger space with the glass atrium; we added two exam rooms and a PA who understands my temper and my soft spots and knows when to schedule the hard conversations at 10:30 a.m. instead of 4:45 p.m. because bad news lands softer when there’s daylight left to do something about it. Abby ran payroll like a general. Patients came, and I cut out the parts inside them that wanted to kill them, and that was enough.

Danielle’s pregnancy became chapters instead of headlines. Second-trimester nausea gave way to cravings for citrus and bagels toasted within a margin only she could detect. I learned which crackers settled her stomach and which made her murderous. She learned which jokes helped me not answer late-night emails with scalpels in them. When the twenty-week anatomy scan rolled audio again, the tech said, “Looks like a girl,” with the casual joy of somebody who gets to hand out names all day. We sat in the car afterward with the printouts in our laps like teenagers who had stolen ultrasound photos for a dare.

“I’ve been thinking about names,” she said. “Every time I make a list I feel like I’m auditioning strangers.”

“Pick one that sounds like a woman who shows up early and never breaks a promise,” I said.

“So, ‘Priya’?” she laughed.

“Already taken,” I said.

She ran a finger over the black-and-white image. “Sophie,” she said. “It’s not original. But it feels like it knows how to breathe.”

Sophie it was.

Gavin texted me twice after that, against advice and decency and common sense. Once to say he was in therapy, which is the sentence men in suits offer when they want credit for basic maintenance. Once to ask if he could be in the delivery room. I didn’t answer the first. I forwarded the second to Danielle. She sent back, “My lawyer will respond.” I didn’t ask what the response was. It wasn’t my gate to open.

The decree gave a date when the house was legally mine; months gave me permission to make it feel like it. Mom and I painted the upstairs guest room a color the swatch called “Sailcloth” and the can called “No returns.” The first night the walls dried, I fell asleep to the smell of latex paint and lemon cleaner and, for the first time since the daisies faced the Converse, thought, This is what freedom actually smells like—chemical and faintly ridiculous and new. It wasn’t a grand feeling. It was a practical one. Freedom is often the mundane version of the romance we thought we wanted.

Moving on is not a speech. It’s Target runs and the first time you reach for a glass in a cabinet and your hand lands on the one you meant. It’s a new alarm code that only people you trust know. It’s the calendar blocked for “20-week anatomy” and “Mom’s follow-up wound check” and “staples out” for a patient you don’t want to disappoint.

On a Tuesday in late September, I took my mother to the farmers’ market because her cardiologist said walking is medicine and because I like being recognized where nobody cares I can tie three knots one-handed. We bought tomatoes that actually tasted like tomatoes and a pie from a woman who asked about Mom’s scar without flinching. On the way back, my phone buzzed. Samuel: “Recording received. Entry of Judgment—final.” I showed Mom the message. She squeezed my hand. “Now you can be boring,” she said.

“God, I hope so,” I said.

Sophie arrived on a Wednesday at 4:11 a.m., in a room bright enough to make new people respect gravity. Danielle had texted me at midnight—They say it’s time—and I’d walked into L&D with a bag of crackers and Gatorade like a mascot. The nurse looked at me for one long second and then handed me the cuff to put on Danielle’s arm. We fell into our old rhythm: she breathed; I counted; she swore at me like I had done this to her and I accepted the blame because that’s what friends do when pain needs a face.

When Sophie made her wet, outraged debut, everything that wasn’t necessary left the room. I’m a man who has held intestines and kidneys like sacred packages; I have never held anything like that child. Danielle cried the clean kind of tears that only come when your body has orchestrated a miracle and your heart is catching up.

“Do you want to cut?” the nurse asked me, holding out the scissors with a grin that forgave every dumb thing men have done since scissors were invented.

“I’d rather not,” I said, stepping back, because some cords aren’t mine to declare about. Danielle cut with a hand that didn’t shake. Sophie accepted the light like it was her birthright.

Gavin wasn’t in the room. That was Danielle’s boundary and her lawyer’s letter and a choice that doesn’t require approval from the people who don’t have to heal from it. He came later, under supervision, and cried the way men cry when they didn’t earn it but the universe gives them a chance to try again for the child’s sake. Danielle and I didn’t talk about those minutes. Some acts of mercy don’t need narration.

In the weeks after, my phone filled with photos of a small person making the same three faces in rotation and somehow still being absolutely new each time. At night, after a twelve-hour day, I’d stop by with takeout and hold Sophie so Danielle could shower without negotiating with an infant. Sophie would stare at the ceiling fan like it had secrets and then fall asleep against my collarbone with a weight that told the nervous system to believe in something again.

“Don’t imprint on that smell,” Danielle would call from the bathroom. “You’ll buy a ceiling fan you don’t need.”

“Already put it in the cart,” I’d say.

My mother met Sophie the way queens meet heirs—solemnly, then with extravagant spoiling. She started knitting a lopsided blanket and refused to stop even when I pointed out that we own, in 2025, at least six functioning blankets. “This one will be an heirloom,” she said. It looked like a topographical map of a region nobody wants to hike in. Sophie spit up on it immediately. Mom called it christening.

I won’t pretend everyone applauded. There were people who thought the group chat was a nuclear option. There were people who thought I should have forgiven, or at least negotiated more romance into the spreadsheet. There were moments—in the grocery store when a song Nicole liked came through tinny over freezer cases; in the locker room when a resident mentioned Gavin’s name with the kind of reverence we used to both earn—when a soft ache bent me at the waist for no good reason. You don’t schedule those. You nod at them and keep pushing the cart.

What I know now is this: pain is not a plan. It’s a symptom. What you do with it is medicine or malpractice.

Blind revenge feels like anesthesia—fast, complete, and then you wake up with everything still bleeding and a back you can’t uncurl. Intelligent justice is less satisfying at first. It requires phone calls and forms and the patience to let other people do their jobs. But it heals cleaner. Fewer adhesions. Less scar tissue where your future needs to bend.

A year after I walked into my own house and heard a voice that wasn’t mine in a room that used to be, the practice was solvent, my mother had started dating a retired pharmacist who wore hats so dignified they counted as an apology for men my age, Sophie had two teeth and a laugh like glass chimes, and the daisies on the table were the fourth bouquet I’d bought without anyone to impress. The house smelled like lemon cleaner and coffee and a hint of baby formula. Freedom still smelled faintly like paint.

Nicole moved two cities over and took a job at an outpatient center that had never met her. We didn’t talk. There were no late-night apologies or early-morning re-litigations. Some stories end with credits and some with ellipses; ours ended with paperwork and silence. The friend group adjusted its seating chart. Priya still grilled burgers; Ethan still burned one patty every time and claimed it was on purpose for me. When someone new joined the table and asked how we all knew each other, we smiled and said “residency” and “hospital” and let the specifics be ours.

Sometimes, on Friday evenings when clinic finished on time and nobody bled and my hands were clean, I would take a walk through Oak Creek and listen to sprinklers and the municipal fountain and the distant sound of teenagers convincing each other they were immortal. Every so often, a pair of black Converse would flash past on a kid’s feet and I’d feel my chest tighten and then relax as my brain caught up. Not every shoe is a sign. Sometimes a shoe is just a shoe.

One night, I found my mother on the porch with Sophie asleep against her shoulder and Danielle next to her, hair in a messy bun, eyes half-closed, that look new mothers get when they’re running entirely on instinct and carbs. The porch light lit them like an old painting someone cleaned. I stood there for a beat too long, memorizing an ordinary miracle.

“You look like a man who forgot what to do with an evening,” Mom said without moving.

“I was thinking,” I said. “About how crises save us from lives that weren’t real.”

She smiled into Sophie’s hair. “I said that,” she said, smug.

“I know,” I said.

Danielle patted the spot next to her. “Sit,” she said. “Be boring with us.”

So I sat. We were quiet for a while, the kind of quiet you don’t get in hospitals or courtrooms or houses that hold other people’s secrets. Down the block, a porch light flicked on. Somewhere, a dog gave up on pretending it was a wolf. The night air smelled like cut grass and something sweet from someone else’s kitchen.

“Do you miss it?” Danielle asked after a long time. “The noise?”

“No,” I said. “The noise misses me.”

Sophie snuffled and resettled. The porch boards creaked their old song. I thought about the first three nights in Mercy General and the way the hospital breathed like a sleeping whale under fluorescent moons. I thought about the second floor of my house and a door I didn’t open. I thought about a judge initialing a piece of paper and Abby saying the numbers were good and Priya’s over-salted onion dip and the look on a child’s face the moment anesthesia lifts and they realize the pain that brought them here is gone.

There was an ending in all of it, and a beginning.

I don’t believe karma has a calendar. I do believe choices have math. The ones we made a year ago added up to this: a porch, a baby with milk drunk breath, a mother pretending not to be awake, a friend who became family without needing a romance to make it official, a house that smelled like lemon and second chances, and a man who didn’t break the plate even when it begged to be broken.

In the end, there wasn’t one verdict. There were a hundred daily ones, small and cumulative, that turned a disaster into a life. Not perfect. Not cinematic. Kinder.

I took a breath and let the night keep it.

The End.

News

They Called My Phone a ‘Brick’—Then I Used It to Buy Their Companies… CH2

Part I: They say the most dangerous person in the room is the one everyone underestimates. I learned that in…

Mom Yelled at Me to “Get Out and Never Come Back” — Weeks Later, Dad Asked Why I Stopped Coming… CH2

Part I: Mom’s voice ricocheted off the doorframe and into the hot July evening. “Get out and never come back.”…

I RETURNED FROM MY TOUR TO FIND MY 9-YEAR-OLD SON ON THE FLOOR. HIS CUSTOM WHEELCHAIR WAS… CH2

Part I: The first thing I saw when I stepped through the door wasn’t my wife. It was my boy—nine…

Husband Moved to Barcelona with Mistress While I Picked Up Our Son—Until He Returned… CH2

Part I: The rain in Portland didn’t fall so much as it insisted. It was the kind of rain that…

My Brother’s “Joke” Left Me Unable to Walk—Dad Said I Was Overreacting. The MRI Made Them Criminals… CH2

Part I: I hit the deck before I even hit the deck. The way my mind replays it, there’s a…

“My Mother-in-Law Handed Me a “Special Drink” with a Smile — But I Saw What She Did Just Before… I Swapped Glasses With Her Husband, And the Truth About My Drink Shook the Entire Family Dinner… CH2

At first, nothing seemed unusual. Gerald sipped slowly, chewing through the rosemary chicken Diane had plated with such ceremony. Conversation…

End of content

No more pages to load