Part I

I never thought I’d be the guy writing one of those “you won’t believe what happened to me” posts. Those were for strangers with usernames that sounded like license plates and plot twists too clean to be real. My life was ordinary on purpose—same coffee every morning, same drive to work, same text from my wife around 11:42 a.m.: How’s your day, babe? I thought predictability was love’s best friend. Turns out it’s also a great hiding place for lies.

It started with a drizzle the weatherman promised would burn off by noon. It didn’t. By five, the drizzle had upgraded to a steady rain, and by six, every brake light in the city glowed red in the mist like a warning I didn’t understand. At 6:15 my phone buzzed: Last-minute dinner with a client. Don’t wait up—E. Emily’s messages always looked like magazine captions—short, neat, no typos. I pictured her at a downtown bistro with cloth napkins, typing under the table while someone in a blazer droned about market share.

At 6:40, my boss called. “Hey, man, forget the deck. Client punted. Go home.” Relief hit my shoulders like a hot shower. I was halfway to the freeway when I remembered the bakery on 3rd and Wads. Emily loved their strawberry cheesecake. She claimed it tasted like summer even in February. I swung right, cut through a puddle that scolded me up the side of the truck, and walked into a bell and the smell of butter and sugar and happiness.

“One slice or a whole?” the kid behind the counter asked.

“Whole,” I said, letting myself be a movie husband for once. “She’ll love it.”

I pictured Emily’s face when I walked in early with a ridiculous dessert. She’d put a hand to her chest and pretend to be scandalized by the calories. I’d say, “We’ll give half to the neighbors.” We’d eat seconds anyway. We’d kiss. We’d laugh. We’d cue the part of marriage that makes people in restaurants glance over and smile like they were rooting for the home team.

The house was dark when I pulled into the driveway—not unusual if she’d left for that client dinner. The rain stitched lines down the windshield. I sat for a second, listening to the engine tick as it cooled, and felt content in the dumb, simple way men feel content when they think they’ve done something good. I grabbed the bakery box and my laptop bag and jogged to the porch. The lock turned easily.

“Em?” I called, toeing off my shoes. The air smelled like her perfume—the citrus one—and something else underneath I couldn’t place. The box felt heavier in my hands all of a sudden, like my arm had remembered gravity the hard way.

No answer. I set the cheesecake on the kitchen island and noticed two wineglasses by the sink, turned upside down on a dish towel like a polite lie. Maybe she’d had a friend over before her dinner? I told myself it made sense because I needed it to.

“Em?” I called again, softer this time, as if I might scare off whatever answer was in the house.

A floorboard upstairs gave a tiny, complaining squeak. I looked up, then back at the cheesecake, then at my own reflection in the oven door—a man trying to pretend he didn’t already know. My legs moved before my brain did. The stairs were a tunnel. The hallway was longer than it had ever been. The bedroom door was mostly closed, the way we leave it when we’re half-dressed and one of us runs for water.

I heard it before I pushed the door: a breath that wasn’t alone, a laugh that had edges, the slick, unmistakable rhythm of bodies that were not mine and mine.

Time does the stupidest things when it wants to be cruel. The room was exactly as we’d left it that morning—the navy throw tossed on the chair, her robe hanging off the bathroom doorknob, the framed picture of us in Cape Cod smiling into salt air like we meant it forever. Only now the bed hummed with a truth that canceled everything behind it.

There she was. Emily—my wife, my person, the woman whose grocery lists I could picture—naked and tangled with a man I didn’t recognize. He had a tattoo I’d never seen and a fading farmer’s tan line that didn’t belong to our house. She looked like a stranger wearing my wife’s face.

I didn’t shout. I didn’t lunge. My whole body went quiet the way sometimes the ocean goes still before it remembers itself. The cheesecake box slid from my hand and hit the carpet with a dull thud. The lid flipped open. Pink and white collapsed into beige. It looked ridiculous and obscene at the same time.

The guy scrambled like a lizard under a porch light. “Jesus—” he said, half a curse, half a prayer, grabbing for his pants, hopping on one leg, nearly faceplanting into the dresser. He was gone before I found a word for him, shoes abandoned near the window like a cartoon.

Emily’s eyes met mine. She didn’t flinch. She didn’t blush. She didn’t even bother with the theater of pulling the sheet up to her chin. She curled her lip—a smirk I’d seen her use on waiters and on me when I couldn’t find the car keys. “You weren’t supposed to be home,” she said.

Something in my chest did a small, quiet snap. Not the loud crack movies give you, the neat catastrophic break. A tiny tendon of mercy or denial just let go.

“Get. Out.” I said. My voice came from a far room and arrived calm. I didn’t recognize it.

She laughed. Laughed. “You won’t do anything,” she said, like she was reading an old script from a role she’d outgrown. “You never do. You’re too soft. That’s why I needed a real man.”

The world narrowed to a tunnel I didn’t pick and I walked through it. I opened the nightstand drawer and felt my fingers find the smooth handle of the bat I kept there for reasons that felt ridiculous right up until they didn’t. It was an aluminum youth-league bat, scuffed at the end, more memory than weapon. I set it against the bedpost and kept my hand on it the way a conductor might rest his hand on a music stand before the downbeat.

“You think kindness is weakness,” I said, still in that far-room voice. “But kindness is restraint. And tonight, I have none to spare.”

Her face changed then, and if I had been a gentler man in a gentler room I might have felt something for the fear that finally found her eyes. The fear wasn’t for what I’d do to her. It was for what I was willing to take away.

I didn’t touch her. I didn’t touch the bat again. I smashed the lamp. The bulb popped and the room swallowed the sound like it had been waiting. I swung at the dresser mirror and watched our staged life shatter into a hundred stupid, pretty fragments. I hammered the frames on the shelf—engagement, honeymoon, first Christmas—until glass glittered in the carpet like confetti from a party we were late to realize we hated. I tore the sheets, the pillowcases, the duvet—ripped them down to fabric, the way a contractor strips a room to studs so he can tell the truth about the foundation.

“Stop!” she screamed, grabbing the sheet I’d already torn, trying to cover herself and the wreckage. “Stop! You’re insane!”

“No,” I said. “I’m finally symmetrical.” A stupid line—and yet it felt right. For the first time in years, what was inside me matched what the room looked like.

She ran. She scrambled down the hallway, nearly sliding into the wall, nearly falling on the stairs. I followed to the landing and watched her fumble with the lock with shaking fingers.

“Run,” I said, the bat at my side, my voice steady as a power outage. “Run far. The life you had here is over. You don’t live in this house anymore. Do not come back.”

She bolted into the rain barefoot, a tangle of limbs and hair and wrong choices, clutching her dress, slipping once on the wet stone of the porch, catching herself, sprinting toward her car like a teenager after curfew. The night took her in and gave me back my breathing.

I stood on the landing for a long time, the bat suddenly ridiculous in my palm, the silence loud. The house smelled like metal and perfume and wet carpet. I walked back to the bedroom, stepped over glass, and sat on the edge of the ruined bed. My hands shook. My chest did that post-spike rattle you get after a sprint. I stared at the cheesecake bleeding into the carpet and felt something ease.

People talk about grief like a rogue wave. That night it was a tide going out. Every lie left with it. The ring of my phone over and over—EMILY—EM—UNKNOWN—EM again—sounded far away like somebody else’s ringtone in a waiting room.

When it finally stopped, I picked up the shards of our faces from the floor and laid them in a pile on the nightstand. I got a broom and swept what I could. I opened windows and let the rain make the house honest. I gathered her clothes—dresses, blouses, the sweatshirt she stole from me in 2013 and never gave back—and stuffed them into contractor bags. I found a shoebox of letters from the early years and put it gently into the bottom drawer. Leaving everything isn’t the same thing as burning it. Some things you let die naturally.

At dawn, I drove to a twenty-four-hour hardware store and bought new locks. The guy behind the register had a jaw like a cinderblock and a kindness I needed. He didn’t ask why I was buying three deadbolts and a security bar while still wearing a wedding ring. He said, “Want me to show you how to install these?” like he was offering me a chair.

At nine, I was at the courthouse filing for divorce with a clerk who stapled like her life depended on it. “I’m sorry,” she said, and I believed her because I suddenly believed anyone who didn’t try to dress bad news in flowers. At eleven, I changed passwords, canceled shared cards, called a locksmith to do what I had done and say, “That’ll hold.” At noon, I dropped off the contractor bags on Emily’s parents’ porch, rang the bell, and drove away before anyone had time to practice their faces. I didn’t leave a note. Words had already failed us.

She called. She texted. The first messages were apologies written like marketing copy—sleek, hollow, tested on focus groups. Then they were angrier, louder. You overreacted. We were on a break. (We weren’t.) You made me lonely. We both made mistakes. I’ll die without you. You wouldn’t dare leave me. Pick up the phone. When I didn’t, they shrank to single bubbles. Please. When those didn’t work, she left voicemails I didn’t listen to. I watched the timestamps, not the content, and let them be ghosts in my call log.

I slept on the couch that first night with the TV on low like a nightlight for grown-ups. I woke at three to the sound of rain stubbornly refusing to move on, and in the dim blue of the living room I realized something that made me sit all the way up: I wasn’t broken. Not in the way I assumed I’d be. Grief isn’t always collapse. Sometimes it’s clarity.

The next day, I called an old friend I’d neglected because marriage is greedy with time and told him everything except the parts that felt like cheap theater. “Come lift heavy things with me,” he said. “That’ll fix exactly 0% of your problems, and also it will fix 10%.” I met him at a gym that smelled like rubber and ambition. I put my hands on a barbell and reminded my body it was built to do something other than clench.

At work, I told my boss in one sentence that didn’t require sympathy, just scheduling: “I’m going through a divorce and will keep my deadlines.” He said, “Take Thursday,” which felt like grace disguised as HR. When people asked why I looked tired, I said, “House stuff,” and they nodded because everyone is always carrying something; mine just had a title now.

On Friday, a locksmith named Gigi finished what I had started and showed me how the new lock threw the bolt with a satisfying clunk. “You’re good,” she said. “My ex taught me everything I needed to know about doors.” We laughed in the doorway like soldiers showing each other scars.

Saturday, I walked through the house with a contractor-sized trash bag and collected the things that hurt when I looked at them. The mug from the bistro where she said I love you like a dare. The throw pillow she bought that always scratched the side of my face. The scented candles I pretended not to hate. I put them in the garage. Not burned. Not smashed. Just not in here. Absence is an underrated tool.

Sunday, I sat at the kitchen table with a legal pad and made two lists in block letters: Things I Control and Things I Don’t. Under the first I wrote: Locks. Lawyer. Gym. Sleep. Friends. Work. Don’t answer. Under the second: Her. Her stories. Her parents. Rain.

On Monday, I stopped wearing my ring. The indent on my finger felt like a phantom limb. It faded. I didn’t.

People expect a grand finale to stories like this—the explosive confrontation in a parking lot, the alcohol-fueled confession, the neighbor who says “I knew something was off” like it’s a gift. But most endings are slower. The paperwork took weeks. The calls dwindled. The rain stopped. The carpet guy gave me a quote that made me fall in love with hardwood. The cheesecake stain dried into a pink bruise in the fibers that looked like a map of a country we’d never visit again.

Three weeks after the Night of the Strawberry Cheesecake, I stood on my porch with a coffee I’d made exactly the way I liked it and watched a woman in a yellow raincoat walk her dog. The dog stopped to sniff a patch of our lawn like it had a secret. The woman tugged gently on the leash and said, “Let’s go, buddy.” The dog went. Ordinary life kept happening, which felt offensive at first and then felt like mercy.

I don’t tell this story because I want applause for not swinging the bat at a person. The bar for men is low enough to trip over; I’m not trying to limbo under it. I tell it because there’s a version of me that would have let Emily’s smirk write the next chapter. He would have begged. He would have bargained with dignity the way people bargain with gods. He would have stayed and learned to live with a splinter in the center of his life. I don’t hate him. I’m just glad he wasn’t home that night.

I also don’t tell it to make a hero out of rage. Rage doesn’t build. It clears. What you do with the room after matters more than the swing that made it. The bat went back into the nightstand. The bed got a new frame and the softest sheets I could afford. The house started to sound like mine when I walked through it.

By the end of the first month, I could say my ex-wife out loud without tasting metal. The divorce moved through the system like a package you track—departed facility, in transit, out for delivery. Friends stopped saying “if you need anything” and started saying “I’m outside with tacos.” I learned to stop correcting the world when it assumed I was okay. Sometimes the assumption holds you up long enough that you actually are.

On the fiftieth night, I slept in the bedroom again. The window was open. The air smelled like someone else’s laundry and rain coming back to threaten us out of habit. I fell asleep to a podcast about national parks and woke up with the quiet kind of happiness that doesn’t call attention to itself. It just sits in the room like a good dog.

If that were the whole story, maybe this would be an essay about resilience and paint colors. It’s not. There was still a court date. There was still a text three months later from a mutual friend saying Emily was telling people I’d “abandoned” her, which I suppose is one word for making a boundary visible enough to trip over. There was still the friend-of-a-friend who’d seen her at a bar laughing too brightly with a man who wore his watch like a billboard. There was still the Sunday I drove past the bakery without stopping and felt my chest tighten but didn’t turn the wheel. There was still the day I opened a drawer and found a twenty-dollar bill she’d hidden in an old birthday card with a note in her slanted print—rainy day fund—and laughed because, well, rain.

But the worst day was already behind me, and I survived it without becoming someone I wouldn’t want to sit next to on a plane. If you’ve been there—if you’ve stared at the ruins of a room that used to be safe—maybe that’s enough for now. You don’t need to swing a bat. You don’t need to be a hero. You need to stand in your own house and say No more. If you whisper it, it still counts.

The night I caught her in the act didn’t break me. It broke the story I was telling myself about what I was obligated to endure. It made room for a better one.

Part II

Divorce papers aren’t thick the way you imagine a life’s ending should be. They’re a disappointing handful of pages with lines for signatures, boxes for dates, and a gravity the weight of a brick. My attorney—Victoria, mid-40s, hair like a clean decision—slid the stack across her desk on a gray Tuesday and said, “We’ll file today. Temporary orders hearing next week. You’ll be okay.”

“Okay feels ambitious,” I said.

She smiled without trying to sell me anything. “Okay just means you’ll keep breathing in order. In. Out. Sign here.”

I signed. She walked me through what happens to lives when they stop being shared: the house (mine, bought pre-marriage), the retirement accounts (mine, but we’d divide the sliver accrued during the overlap), the couch (hers, heavy as sin, which was why I was secretly glad to hear it might be leaving). She told me not to talk to Emily without counsel present. She told me to screenshot everything. She told me to stop apologizing to the air when I took up space.

In the hallway, as I waited for the elevator, I read the court’s stamp at the top of the petition—DISTRICT COURT, COUNTY OF JEFFERSON—and felt something unclench. Paper had taken the baton. I could stop sprinting.

That night, for the first time since the Night of the Strawberry Cheesecake, I slept with the window open. The rain had finally packed up and moved on like a noisy neighbor who’d run out of weekends. The breeze carried in somebody’s laughter, tires on wet pavement, the faint metallic clink of a flagpole clip. The house breathed with me. In. Out. Okay wasn’t heroic. It was a willingness.

The days between filing and the first hearing felt like being stuck in a waiting room where the receptionist keeps saying “soon” and the clock refuses to prove it. Emily oscillated between silence and theatrics. My phone lit with unknown numbers—her, probably—then with known ones. Friends who meant well, friends who meant to gossip, friends who surprised me with tacos. Her parents called exactly once from my old entry in their phone—Son-in-law—and left a message that just said, “Call us,” like they’d forgotten how to form new sentences.

I didn’t call. I did call my brother, Chris, who’s a stoic in a flannel and has one of those faces that only knows three expressions but means all of them. He listened, which is the best trick quiet people pull. He said, “Come help me build a workbench.” We did. Sawdust is grief’s cousin in that it gets everywhere and makes everything look new when you sweep it up.

At the temporary orders hearing, Emily arrived in a dress that used to be my favorite and now just looked like cloth. The man with the farmer’s tan didn’t come; he had been a plot point, not a person. She sat at the other table with a lawyer who had the exact haircut you’d order if you wanted to look honest. When our case was called, the judge—firm, kind eyes, voice like a seasoned middle school teacher—read the file, asked for brief statements, and issued a protection order that said: No contact without counsel. No entry to the residence. No theatrics in driveways, grocery stores, or anybody else’s common areas. The court can be thrillingly specific when it wants peace.

Emily didn’t look at me when it was over; she stared at the table like a good actor playing remorse. Outside, in the hallway, she broke character long enough to say, “You’re ruining my life,” which is one of those sentences that sounds big until you realize it’s just a smaller way of saying I lost control.

“I’m enforcing mine,” I said, and Victoria stepped between us like a professional bouncer.

“You need to funnel communication through me,” she told Emily’s lawyer, who nodded tightly and steered Emily toward the elevator like a dad dragging a toddler away from a jewelry store.

I took the stairs. Office stairwells smell like secrets. Mine, this time, smelled like dust and the faintest whiff of a cologne I used to wear when I thought marriages could be saved by being the kind of man other men admired. I laughed once on a landing. It echoed. Nobody shushed me.

Back at the house, I made a ceremony out of ordinary things. I replaced burnt-out bulbs. I reset the wobbly leg on the dining table. I re-shelved books in an order that made sense to the part of my brain that likes to file socks by color. I bought the good coffee at the store without convincing myself I didn’t deserve it because the bag costs a dollar more. The cheesecake stain faded from a pink bruise to a pale memory across the fibers. I didn’t rush the carpet guy this time. Sometimes letting a mark fade on its own is the lesson.

On Sundays, I started going to the gym with my old friend Eric—he of the taco rescue—and the kind of men who grunt when they pick up heavy things and then turn around and ask if your shoulder’s okay. I liked the way deadlifts made my brain go quiet. I liked the way my hands toughened at the exact speed my patience returned. You cannot cheat a barbell. It tells the truth every time.

On Wednesdays, I sat on a couch across from a therapist named Maya and told her things I hadn’t admitted to anyone, including myself. Like the way I sometimes knew the marriage was a quiet museum where nothing new got curated. Like the way I had ignored a laugh that felt wrong six months ago because I didn’t want to write a new story. Like the way anger sat in my chest like a coin I kept flipping in my fingers to feel its weight.

“Anger isn’t an identity,” Maya said. “It’s a signal. Listen. Thank it. Then take your hand off its back.”

On Fridays, I cooked food that required instructions. I’m a decent grill guy, but recipes with verbs like simmer and reduce and fold had never felt like mine. I learned to make a pasta sauce my grandmother would have blessed. I roasted a chicken that made the house smell like a promise. I ate at the table without my phone and remembered what it was to be a person in a room without needing a channel to explain me to myself.

One night at the end of a long week, I was washing dishes when I heard a car door slam and the rushed footsteps of a woman who has decided to get in one last word. The doorbell rang the way a dare feels. I checked the peephole. Emily. Alone, hair damp from a shower or the rain that had done its on-again-off-again routine all afternoon. I considered not answering. I considered a speech in my best courtroom voice. I did the sensible thing. I called Victoria, put the phone on speaker, and cracked the door with the chain in place.

“You’re not supposed to be here,” I said, before she could start. “There’s an order.”

“I just want to talk,” she said, which is the worst sentence in this genre of life, because it usually means I just want to reset our dynamic so you’re carrying the heavier end of the piano again.

“Talk to your lawyer,” I said. “She knows my lawyer’s number.”

Her eyes flicked to the chain. “You’re really doing this?”

“I really am.”

She looked past me at the foyer table where I’d stacked mail and a tiny dish for keys and a plant that an algorithm convinced me would be unkillable. We had never kept plants. She used to joke I was jealous of anything else getting sunlight. She looked back at me and did the thing I didn’t expect: she cried the way people cry when they finally get lost in the map they drew themselves.

“I messed up,” she said, which is the first honest sentence I’d heard from her mouth since the night I brought home a strawberry cheesecake. “I messed up a long time ago. I don’t even know when.”

“I hope your life is good,” I said. “I hope you make it good.” I meant it. I also meant never come here again. Both can be true.

She nodded like a person learning how to own a small piece of humility without putting it on a shelf for display. She turned. She left. The footsteps up the walk sounded like an ending everyone could live with.

Two weeks later, I ran into the other man at a gas station—a detail I would cut from the movie for being too obvious if I hadn’t watched it happen. He was at pump 6, filling a truck that had more chrome than sense. He saw me before I saw him. His eyes did that little calculation—fight, flight, apology—that men do when they realize they’ve had a role in somebody else’s emergency.

He walked over. He kept a social distance of a yard and a half, and for once in my life I was grateful for a measurement we all understood. “Hey,” he said, voice flat.

“Hey,” I said.

“I didn’t know she was married,” he lied, which is the sort of sentence you decide you can live under until it collapses.

“I didn’t know you existed,” I said, which was true and a better line. He winced. He looked at the ground. He tried again.

“I’m sorry,” he said. “Not sure what else there is.”

“There isn’t,” I said, and returned the nozzle to the pump like a man who has decided to pour his fuel into a vehicle that gets him somewhere worth going.

When I pulled out, I didn’t do the thing movies do where the hero floors it and peels out into an act of catharsis. I turned on my blinker, waited for a space that belonged to me, and merged.

The divorce moved, as promised, like a package I refused to obsessively refresh. I let Victoria obsess for me. On the morning of the final hearing, I ironed a shirt that had grown lonely at the back of the closet and drove to the courthouse under a sky that couldn’t decide if it wanted to be kind. The judge read the agreement, asked if we both understood it, and banged the gavel not like thunder, but like a woman who believes in finishing what she starts.

Outside, in the bright, cold air, Victoria handed me a manila folder and said, “Decree. Certified copies. Your life, on paper.” I shook her hand like she’d given me a parachute I’d forgotten how to ask for.

I half-expected to feel grief grab me at the ankles and drag me back down the courthouse steps. Instead, I felt light, which would be the corniest possible word if it weren’t accurate. My phone buzzed. Eric: Patio beers? Or a hike? Or both like legends? I chose the hike because legends are for people with capes; I had boots.

We drove an hour into the foothills and found a trail that switchbacked through pine and aspen, the air that same thin gold we only get a handful of days a year. Somewhere near the top, the chatter in my head finally shut off like a light you forgot you could flip. We sat on a rock and watched two hawks ride thermals like rich people on lazy rivers.

“You’re different,” Eric said, not like a compliment, just an observation.

“I sleep,” I said, which was also not a joke. “I cook. I don’t check my phone in the middle of the night to make sure somebody else’s choices aren’t coming for me.” I paused. “I miss the good parts. Or the parts I thought were good. I don’t miss the smallness.”

He nodded. We ate Clif Bars like they were steak, because that’s what hunger does when it recognizes victory.

When we came down, the parking lot was crowded. Couples scrapped over whose idea this had been. Dogs peed on tires. A kid in Spider-Man pajamas carried a stick like a hero’s staff. Ordinary life piled up around us like blessing.

I don’t pretend there’s a moral you can cross-stitch here. If there is one, it’s boring on purpose: Paper is your friend. Tacos help. Don’t swing a bat at people. Be more curious than ashamed about how you got here. And when someone tells you you’re “too soft,” remember softness is how your lungs inflate; it’s how a heart stays changeable. It’s not weakness. It’s capacity.

Months later, I saw the cheesecake place on my way home from a job site and didn’t turn in. I didn’t speed up either. It was just a store that sells sugar. My house was just a house. My life was just my life, and the best thing about it was that the worst thing that had happened in it wasn’t calling the shots anymore.

I told this story on Reddit one night because insomnia feels less predatory when you name it, and because I wanted to put a hand on the shoulder of some stranger in some town with a box of bakery and a hunch in his gut. If that guy is you: breathe. Paper up. Don’t let anyone turn your kindness into a leash. You’re not a cautionary tale. You’re a person who gets to keep your own keys.

A week after the decree, I took the bat out of the nightstand. I didn’t throw it away. I moved it to the garage and hung it on the wall above the workbench Chris and I built. It belonged there—tool, not threat. Some days I pick it up and remember that clearing and building are both part of the work. Then I put it back and pick up the hammer instead.

I didn’t become a man who hates. I became a man who knows. The difference is a lifetime.

Part III

The week after the decree, the house sounded different. It wasn’t louder. It was honest. The old bedroom set—the one I’d disassembled the morning after the Night of the Strawberry Cheesecake—leaned against the garage wall like a stage set from a play I didn’t want to run again. I put it on a buy-nothing group and watched a single mom back her minivan into my driveway with surgical precision.

“You sure?” she asked, shy and fierce in one breath. “This is nice.”

“I’m sure,” I said. “It’s a clean slate kind of thing.”

She nodded in a way I recognized—like she was accepting something more than wood. Two neighbors came to help load; we strapped the frame down with the kind of knot you only learn after enough things fall off trucks. She offered me a twenty I didn’t take. When she drove away, I stood in the empty garage bay and exhaled the kind of sigh you hear in churches after the big song ends.

The carpet guy finally came on a Tuesday and rolled the old living room rug up into a giant burrito that made the whole place smell like the inside of a vacuum cleaner bag. “You’ll like this,” he said, laying down planks of oak that clicked into place like a long-delayed plan. When he was done, the cheesecake bruise was gone, replaced by boards that caught the afternoon sun and lifted it.

“What do you think?” he asked.

“Like I finally live here,” I said.

That night, I slid across the new floor in socks because sometimes you need to be eight to remember why being alive is any good. I stopped at the window and watched the streetlamp paint a perfect yellow square on the boards, a geometry problem life had actually solved. I set my coffee on it the next morning like it was a sun the house had earned.

People think the big things are what save you. Sometimes it’s buying a bed you actually like. I went to a store with soft lights and a politely pushy salesman who called himself “Dan but with two n’s” and lay on mattresses with names like Tranquility and Auden. I chose one that didn’t try to impress me with cooling gel or cloud imagery—just firm enough to hold a body, soft enough to forgive one. I bought sheets you could swim in and a duvet that looked like an unambitious cloud. Gigi the locksmith texted me a link to a headboard she swore wasn’t tacky; I bought that too. The room came together in creams and navy, like it had finally admitted it had taste.

I kept the nightstand. I put the bat in the garage.

Some nights, the house still did the haunted-house creak at 3 a.m., and the part of me that remembered a smirk and a slammed door woke up with fists. The therapist’s voice helped: You are not in the old scene. You are in a safe room. Feel the floor. Count the things that are actually here: dresser, lamp, your own breathing. I’d count. I’d breathe. I’d fall back asleep to a podcast about rivers that are older than dinosaurs. You have to pick your bedtime stories.

Work got better in small ways. I stopped volunteering to make other people’s panic my schedule. I said “I can do Friday” instead of “I can do tonight” and discovered the sun still rose. I asked for the projects I wanted and didn’t do disclaimers with my mouth. The series Lila asked me to run on “How We Work” turned into a weekly email people actually read. I wrote about calendar debt and meeting bloat and the way “reply all” is the devil’s laughter. Folks sent me screenshots of their decluttered inboxes like I’d told them where the gold was buried. It wasn’t heroics. It was oxygen.

On weekends, I learned the geography of being alone without being lonely. Saturday morning: gym with Eric; hardware store with the weirdly soothing aisle of cabinet pulls; laundromat logic puzzle (how to fold fitted sheets without becoming a liar). Saturday afternoon: game on TV with the sound low, door open, a breeze doing what air does; a nap I didn’t apologize for; a text to my brother about tools we don’t need. Sunday: hike if the sky behaved, breakfast if it didn’t, phone in a drawer for three hours just to prove I wasn’t owned by a slab of glass.

One quiet Sunday I did something I hadn’t thought about since the decree: I opened the shoebox with the old letters—the ones from before everything turned into a museum of pretending. I read three and put the rest away. There’s a grace in not trying to autopsy every memory to prove a point. I slid the shoebox to the back of the closet, not as a shrine, not as a poison cabinet—just as a label on a shelf: archives.

A week later, a letter arrived that didn’t belong with the archives. It didn’t come from Emily. It came from a person with a stamp: the mediator from the divorce, mailing the final, stamped decree and two certified copies like a notary version of a priest. The envelope had heft. I opened it with a cheap letter opener my grandfather gave me when I got my first apartment—brass, shaped like a sword, corny enough to forgive. I ran my finger over the raised seal and felt the weird relief of bureaucracy: this is over not because feelings are balanced, but because paper is.

I posted the story on Reddit that night—under a throwaway handle, because anonymity is a kindness to your future self. I wrote it like I was writing it to the version of me that had stood on the stairs with a bat and a heartbeat and a decision. I didn’t clean it up to make myself look better. Writing made the rooms straighten. The post went weirdly big. Strangers with names like SeatbeltEnthusiast and WaffleJustice told me they were proud of a man they didn’t know. A few people said I should have “punished” her more. One said I was a beta for not breaking the other guy’s jaw. I blocked those. A woman DM’d to say her husband had been kind like me and she’d mistaken it for weakness. She was trying to relearn him. I told her good luck, and I meant it like prayer.

My mother called after she found the post by accident, because of course she did. “Is that about Emily?” she asked, scandal and sympathy fighting in her throat.

“It’s about me,” I said. “For once.”

She harrumphed. Mothers are not trained for sons who become their own narrators. Later she texted a heart, which is how she says I’ll learn you again.

Emily kept her distance because the paper said so, and because I think even she realized two versions of herself were finally out of plausible deniability. Once, a mutual friend told me she’d started therapy. Another time, someone said they saw her walking a dog neither of us owned. Both times I said, “I hope she’s okay,” and changed the subject because sometimes wishing someone well is not a trap door back into the house.

One afternoon in spring, I ran into the man with the tattoo doing exactly what men with complicated choices do when they want to feel simple: buying lumber he probably didn’t need. He saw me first, stared at a stack of 2x4s like they held advice, then nodded. “How’s your bench?” I asked, because small talk is mercy sometimes.

“Level,” he said, shy around the edges. “I’m trying to be better. Not… that guy.” He didn’t say sorry this time. I didn’t make him perform.

“I’m trying to be better, too,” I said. We both looked at drills like they had answers. We paid. We left. Not every ending needs a scene.

The housewarming I never did when the house was new—because we were “busy,” because couples can be precious, because we thought our love didn’t need witnesses—happened in June. Eric came early and hung string lights with a diligence that would impress OSHA. Gigi arrived with a six-pack and a keychain she’d made out of an old deadbolt (“For luck,” she said, and I actually took it). Lila brought a salad that could have hosted a TED Talk. My brother manned the grill like a general. The neighbors wandered in with paper plates and the gossip about the new people down the block who park like they failed geometry. We ate tacos and potato salad that could start a fight in four states. We told stories that didn’t require me to be brave or tragic. At one point, someone’s kid wandered into the bedroom and fell asleep face-down on the new duvet like a starfish that had surrendered.

“Look at you,” Eric said at 11 p.m., when the last cooler had been emptied and the porch looked like the end of a soft war. “A man in his own house.”

“Feels like it,” I said.

“Any… prospects?” he asked, because friends who care about your heart are never quite off duty.

I laughed. “Prospects is a hilarious word.”

“Okay. Human who smiles at you and it lands?”

“Maybe,” I said, because I wasn’t blind. The woman from the bakery—the one who’d sold me the cheesecake that night—had recognized me last week when I finally went back. “Good to see you,” she’d said, and it was neutral and kind and didn’t pin anything on either of us. I bought two chocolate chip cookies and left a silly tip and didn’t narrate it into a movie.

A month later, she—Maya (not to be confused with therapist Maya, different Maya, this one wore a bandana and had forearms that suggested she knew how to lift a sheet tray)—showed up at a charity 5K our company sponsored, handing out bananas at the finish line. We said the kind of nothing that’s actually something. “How’ve you been?” “Good.” “You?” “Good.” A beat. “You still like strawberry?” “In moderation.” She laughed. I laughed. We both looked at the people in foil blankets like a Greek chorus of exhaustion. Nothing needed to happen. Sometimes you just register that the world contains new nouns.

The one-year mark came around quiet. No thunderclap. No confetti cannon. I took the day off and drove west—up 285 to where the air thins and the pines learn to stand shorter out of respect. I parked at a trailhead some ranger probably named after a man who did a thing with a mule in 1897 and started walking. The trail wasn’t a monster; it asked for breath and gave me views in exchange. At the top, I sat on a rock that had been there before my story and would be there after, and I took a picture the internet would not see. Then I took a slice of strawberry cheesecake I’d bought from Maya’s place that morning—just one slice, just because—and ate it with a plastic fork in the thin cold. It tasted exactly like what it was: sweet and ridiculous, a sugar sacrament taken by a man who had taken back his life.

On the way down, I saw a couple arguing in low tones about whether the map was upside down. I smiled. If you’re lucky, you argue with someone about maps sometimes. Or you don’t, and you learn your own.

The day after that, the mediator mailed a ledger of the costs. It was absurd—filing fees, process servers, endless stamps. I scanned it, paid my share, and wrote COST OF FINAL CHAPTER in the memo, not to be cute but to stop myself from muttering “what a waste.” Money spent on leaving the wrong room is not wasted. It’s tuition.

Summer slid into football, and the rhythms of my life settled: work, workouts, hikes, dinners that included vegetables I would have made fun of at 25, a Reddit message here and there from a stranger telling me the part they used, a voicemail from my mother asking if I “had time to fall in love yet” like romance is a closet you can reorganize on a Sunday. I had time to walk outside and watch a neighbor teach his son to throw a spiral. I had time to sit on my steps and feel the temperature drop the way it does on the exact night you know winter will send a Save the Date. I had time, full stop.

In October, I got a letter. Not a certified thing. A real one. Slanted handwriting I recognized. Emily. I didn’t open it right away. It sat on my mantel for two days like a dare. On the third night, I made a cup of tea (who am I?) and slit it open with the brass sword.

It wasn’t long. It wasn’t manipulative. It wasn’t a trap. It read like a person trying to write in straight lines:

I don’t want anything from you. I wanted you to know I’m sorry, without excuses. I thought I was starving and I set fire to a house that wasn’t the problem. I am in therapy. I am not asking you to forgive me or to answer. I know this letter is selfish. I hope your life is good. —E.

I sat with it. I didn’t cry. I didn’t throw it away. I put it in the shoebox with the old letters because it belonged with things that are done. You can honor an apology and still keep a boundary. That’s a sentence I couldn’t have written a year ago.

A week later, I ran into Maya with a bandana at the farmer’s market, because movies make that up and sometimes life does too. We stood in front of a stand overflowing with apples and talked about nothing boring: late frosts, the scandalous price of eggs, the dog she had just adopted who was allegedly part husky but mostly chaos. We exchanged numbers like two people who might text sometimes and might not. I walked away grinning at produce, which is an insane sentence I stand by.

I don’t want to pretend there’s a happily-ever-after here in the way magazines mean. There’s a happily-right-now. My house has clean floors and a dent in the couch where my body belongs. My phone doesn’t own me after 9 p.m. My therapist has a new couch; I still sit on it when my brain tries old tricks; we laugh at them. The bat hangs above the workbench, and the hammer below it gets more use.

People on Reddit ask in DMs sometimes: What would you tell someone who’s where you were? I say: “Trust your gut when it says you deserve a room you don’t have to audit. Love is not a crossword clue you solve by ignoring the squares that don’t fit. Don’t make a home inside someone else’s unfinished business. Paper is your friend. Sleep. Eat. Change your locks. Don’t perform. Don’t let anyone make you believe that softness is a lack of spine. It’s how lungs inflate.”

On the anniversary of my decree, I threw myself a party I didn’t call a party. I invited the same people from June and three more. I grilled chicken that did not burn. Eric made his ridiculous guac. Gigi brought a wind chime she’d made from old keys. We lit the string lights and told small stories. At some point, someone put on a song from 2010 that used to mean something else, and we all sang the chorus anyway because the body keeps the good things even when meaning changes.

At 11:58 p.m., I stood on the porch with a glass of water like an old man and looked up. The sky was dull with city glow. No fireworks. No sign. Just air. I remembered the man on the stairs with a bat. I nodded to him. He nodded back. I put the glass in the sink, turned off the porch light, and went to bed in a room that had learned my name.

To anyone who needed this story to end clean:

It does, in the only way that matters. Not with sirens. Not with revenge. Not with grand speeches that fix the past. It ends with a man in his own house, knowing where the light switches are and how to breathe.

And, okay, one more thing: the next morning, when the bakery opened, I walked in and ordered a slice of strawberry cheesecake. Maya slid it across the counter with a grin that was more about friendship than fate. I took it home. I put it on a plate I liked. I ate it at my kitchen table in a patch of sun. It tasted like sugar and new maps.

Part IV

I didn’t plan to write a “Final Update.” The internet trains you to believe every story needs six installments, a sequel hook, and a twist that makes the comments section scream. Real life is less generous with episodes. It gives you quiet mornings, errands, small mercies, and a handful of moments where you can actually feel the hinge of your life moving.

This is my hinge report.

Two winters after the Night of the Strawberry Cheesecake, snow came early and stayed like a friend who didn’t understand subtweeting. The house learned its cold-weather noises: a polite groan from the water heater, the soft thud of furnace kicks, the claws of a neighbor’s cat performing midnight calisthenics on my fence. I learned mine: stew on Sundays, flannel sheets, a ridiculous electric kettle that sounded like a small jet.

One night a knock came—the firm, rhythmic knock of someone who thinks they’re owed an answer. I checked the peephole. No one I knew. A figure in a parka, hood up, face angled away from the camera like a movie extra keeping their SAG card safe. I didn’t open. The old me—the apologetic, make-things-easy me—would have cracked the door and offered a sentence to fill the silence. The new me poured tea and let the door be a door. After a minute, the figure left. The porch light blinked against the snow. The house breathed.

The next morning, I found a plain envelope tucked under the mat. Inside: a contractor’s business card and a handwritten note that read, If you need work done cheap, call me. No signature. Maybe a hustle. Maybe not. In my old life, I would have spent an hour writing a polite decline. In this one, I recycled the card and went to work. Boundaries don’t always look like speeches. Sometimes they look like paper in a blue bin.

The window part happened two days later—literally. The old dining room window stuck every winter, paint welded to wood by cold and habit. I’d broken two putty knives trying to talk sense into it the year before. This time, I called a pro. She showed up with a crowbar, a heat gun, and the calm of a person who knows structures for a living. “You treat wood like it’s the enemy,” she said, eyes twinkling. “It was a tree before it was your problem.”

She ran the heat gun along the seam until the paint softened, then took the crowbar and lifted as if she were urging the window to remember how to move. It did. Warm air rolled in. I paid her too much on purpose. Two hours later I could open the window with one thumb. I slept that night under the hum of a house that had forgiven me for forcing it.

It took me longer than I want to admit to realize how many parts of my life I’d been trying to pry open with cold hands instead of warming the seam first.

The bat hung in the garage, above the workbench, a relic and a reminder. It wasn’t heavy, but it threw a shadow bigger than it deserved. One afternoon in March, my brother’s kid—Tommy, nine years old and allergic to stillness—came over with a glove and a face like a question.

“You ever gonna teach me to hit?” he asked.

“I can try,” I said. We walked to the park that had been a park long enough to host bad decisions and first kisses for four generations. It was empty except for a dad pushing a stroller and a woman doing lunges that made my thighs hurt just watching. I brought the bat because it was what I had.

I hadn’t coached anyone since I was a teenager bribed with pizza to help with T-ball. I kept it simple. “Feet here,” I said, tapping the dirt. “Hands stacked. Head still. It’s not about murdering the ball. It’s about finding it with the middle of the bat.”

He missed the first four by a foot. He connected with the fifth and looked shocked, like he’d hacked an ATM. The ball arced over second base and landed in the outfield like it had been waiting for him.

He let out a sound I recognized from every set of stadium seats in the world—pure kid glee, no caveats. “Again!”

We stayed until the light got thin and the ball got cold. He hit more than he missed. He learned the song of contact. He learned to drag the bat, not throw it, when he got excited. When we walked home, he put his hand on the barrel the way a kid puts a hand on a dog’s head and said, “Thanks, Uncle D.”

That night, I walked into the garage and stared at the bat on the wall. Tool, not threat. I’d said it before to make myself feel righteous. Now I had a picture to go with the sentence: a skinny kid finding a rhythm, a man standing behind him correcting his feet, not his person.

I emailed the youth league and asked if they needed an assistant coach. They did. The first practice, I watched a half-dozen kids learn to track a ball with their eyes while their parents learned to track their own fears with patience. The bat felt different in my hands there, under lights, beside chalk lines. It was still a piece of aluminum. But in my life, it had changed teams.

People kept asking if I was “dating.” I hate the word—the way it tries to cram human beings into a menu. What I’ve been doing is showing up and seeing if the room feels bigger with someone else in it.

Maya—bandana Maya of the bakery, not therapist Maya—texted on a Thursday: Got a surplus of croissants. If you’re out, bring a paper bag. If you’re in, bring a story. I walked over with a tote bag and a story about a raccoon that had figured out my trash can. She handed me croissants like we were negotiating a prisoner swap. “You look less tired than the last time I saw you,” she said.

“I slept through the night,” I said. “Twice. In a row.”

She whistled. “Lifestyles of the rich and emotionally stable.”

We sat on the bench outside her shop, tucked into flakey butter, and compared notes on small business realities. Hers were flour invoices and ovens that forget the difference between 375 and 425. Mine were vendor contracts and a client who believed deadlines were a vibe. We laughed at all the same places. When a woman walked by with a toddler who dropped a mitten, Maya hopped up, chased her, and returned the mitten with a crouch and a smile that made the kid grin around a pacifier. Heart pinned where everyone could see it. Not performative. Just available.

Two weeks later, we bumped into each other at a bookstore with a cafe that takes itself too seriously. I was in the aisle with essay collections, pretending to re-read Joan Didion so I wouldn’t buy another copy. She was in cookbooks, frowning at a recipe that used “two pinches of love” as a measurement. We did the hello that isn’t nothing. She pointed at my armful of magazine back issues. “Leave those. You always regret them.”

“Every time,” I said, and put half back.

We took our drinks to a table by the window. It wasn’t a date. It was the good part of two people’s afternoons agreeing to sit down together. We talked about the ways people apologize—bad and good. I told her about the letter in slanted script I’d put in the shoebox, the one that asked nothing but acknowledged everything. She told me about a friend she’d forgiven in pieces and the part of forgiveness that isn’t a get-out-of-jail card so much as a decision not to visit the jail again.

When we stood to leave, she said, “You want to split a cheesecake slice on Sunday? Research, of course.”

“Of course,” I said. We did. It was good. Not holy. Good. That felt like a miracle disguised as “decent.”

We didn’t sprint, and we didn’t stall. We texted like adults who have jobs. We went for walks that weren’t auditions. I told her I coached kids because it made me feel useful. She told me she baked because in a world that argues about everything, no one argues with a warm croissant. We kissed, finally, after a farmers’ market where a band massacred Brown Eyed Girl and nobody cared. It felt like something you can rest your weight on, not a trick floor. That’s all I’ll say. The part of this story that belongs to someone else gets told at their speed or not at all.

My father called in late spring from a number I hadn’t saved. The family runs on stubborn genes and inherited silence. We’d done our version of a cold war—holidays with my brother, separate from theirs; texts that said “got it” without asking “how are you.” It wasn’t cruel. It was the shape that fit on everyone’s plates.

When I saw “UNKNOWN” light up and my gut said “Dad,” I let it go to voicemail. He left a message that started with a throat clear and ended with a sentence he probably practiced for a week. “I saw your post,” he said. “Or what I think was your post. I don’t know. The point is: you’re… stronger than me. I’m proud and mad about it. That’s all, son.”

I stood in the kitchen and listened twice, then once more. I didn’t call back. We’re not a phone family. I sent a text. I heard it. Thanks. He replied with a thumbs-up and a picture of a trout he’d caught and released. If you know men like my father, you know that’s basically a hug.

Emily didn’t call. She didn’t show up. She didn’t “accidentally” drop a box of old stuff at my door. Whatever life she built after the house didn’t include me as a rehearsal audience. Good. At the one-year-plus-something mark, I mailed her lawyer a check for a final utility reconciliation and a note that read: Paid in full. We’re good. It felt like closing a tab at the end of a long night where everyone drank different things.

The last word, in the end, wasn’t mine or hers. It was the judge’s, in plain language stamped by a court, and it was the quiet words I say to myself when the old reel tries to roll: You’re home. It’s quiet. Breathe.

The internet prefers the after picture: fifteen pounds down, new couch, new girl, a salsa recipe that slaps. My after is mostly the during, and the during is good.

I coach on Tuesdays and Thursdays and text the parents lineups on Sundays with emojis that make nine-year-olds feel like pro athletes. Tommy can turn a double play now if you give him a friendly ump and mercy on the hop. One of my kids hates helmets because they mess with her ponytail; I taught her how to fit one without flattening her identity. After practice, I drag the infield and listen to my shoulders talk about middle age. It sounds like the right kind of creak.

I still see therapist Maya once a month, insurance be damned, because maintenance is cheaper than rebuilds. We don’t autopsy the past anymore; we inventory the present. “What are you proud of?” she asks. “What are you avoiding?” I’m proud I no longer check the locks twice. I’m avoiding buying a new couch because the old dent fits like the only custom thing I own. “Buy the couch,” she says. I do. It arrives in a box the size of a Prius and takes me two hours and one YouTube video narrated by a man who calls every piece “buddy.” When I’m done, it looks like a place you could fall asleep on purpose.

Maya-with-the-bandana and I keep choosing each other in small ways—Tuesday croissants left on my porch when she bakes too many, Saturday hikes where we turn around before our pride hurts our knees, Wednesday texts that say “thinking of you” because thinking of a person and telling them are separate acts. Her dog, Moose, loves me with the intense diplomacy of a husky mix who believes all humans are meetings he could have been an email. Sometimes he sits at my feet while I read, his head heavy on my shoe, and I feel a peace I used to be suspicious of.

The bakery is doing well. She added a sandwich menu that makes no sense (fig jam on roast beef?) and has a line out the door anyway. I bring the team after practice sometimes. The kids shout orders like short orders at a diner in a TV show. She pretends to be flustered and remembers every single allergy.

On a Thursday night in July, our league played under the lights for the first time. The stands were full of folding chairs and parents who forgot to bring bug spray and didn’t pretend they weren’t getting teary when their kids’ names echoed out of a tinny PA system. I watched Tommy step into the batter’s box and do the little foot wiggle I taught him to loosen his hips. First pitch, he swung smooth and drove a line drive into right. He ran like the outfield was lava. He pulled up at second and looked into the dugout for me like a kid reaching for a high-five from the universe.

I raised the bat—my bat—over my head and tapped the air twice. He grinned and tapped his helmet back. When the inning ended, he ran over and said, “That felt like the middle.” I knew exactly what he meant.

When I posted the first part of this story, I was writing for the version of me who needed a stranger to put a sentence on his shoulder and leave it there. If you’re that guy—if your gut already knows what your mouth is afraid to say—I don’t have new wisdom. I have the old stuff, dressed in clothes that fit me.

Paper is your friend. Police reports, court orders, receipts, sign-in sheets. They make rooms quiet without you having to shout.

Kindness isn’t weakness. It’s the discipline of not letting rage do your thinking. Keep it, but don’t let people rent it from you at a discount.

Don’t become the worst thing that happened to you. Let it clear the room. Then pick up a hammer.

Sleep, food, water. Boring wins long games.

Ask for help the way you’d want someone you love to ask you. People want to carry the light end of your couch.

Don’t narrate your life into a genre that hurts you. You’re not a revenge story. You’re a rebuild.

And if you’re wondering whether to smash a lamp or a mirror or a picture frame: don’t. You’ll step on it later. Go outside. Walk in the dark until the neighborhood looks like a place you could live. Come home. Change the locks. Eat something warm. Call the lawyer. Call the friend. Breathe.

Here’s how my last episode ends, because people like closure and I’m learning to offer it.

It’s late August. The house is open to a night that finally cracked and let cool in. There are shoes by the door that aren’t all mine. Moose is asleep on the rug like a bear rug someone forgot to taxidermy. The bat hangs in the garage, scuffed from whiffle balls and foul tips. The shoebox sits on the closet shelf like a closed book. The couch is new and has seen naps it can brag about.

I take a slice of strawberry cheesecake out of the fridge and carry it to the porch. I eat it in three slow bites, the fork scraping the plate the way it does in diners at 2 a.m. when people admit things. I’m not confessing anymore. I’m grateful. For the friends who showed up with tacos. For the lawyer who stapled my life back together. For the clerk who stamped the paper that freed us from each other. For the kid who found the middle of a bat. For the woman who returns mittens and bakes too much. For the man who learned the difference between clearing and building.

I put the plate in the sink. I turn off the porch light. I walk upstairs and count the things that are actually here: dresser, lamp, a book with a dog-eared page, a second toothbrush that doesn’t scare me, my own breathing.

Then I sleep. The house sleeps with me. The night does what nights do—both forgive and forget.

That’s all. That’s the ending. Not thunder. Not sirens. A latch you can lift from the inside and a window that opens with one thumb because you learned to warm the seam.

— The End —

News

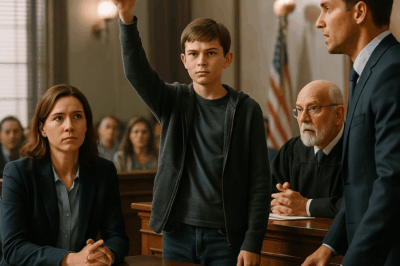

My Ex Told the Judge Our Son Wanted to Live With Him. Then My Son Pulled Out His Phone… CH2

Part I The courtroom was quiet, but not the kind of quiet that helps. It was the kind that made…

My Son Broke a Bully’s Arm. His Father Came For Me, Then I Said The One Word That Made Him Flee… CH2

Part I On Maple Street, the morning always started with sunlight and simple math. Two eggs, over easy. One travel…

Cheating Wife Walked Into The Kitchen & Froze When She Saw Me,”You Didn’t Leave?”… CH2

Part I The saw kicked back and bit deep into my palm, splitting skin like wet paper. A scarlet V…

My Parents Hid My Tumor, Calling It “Drama”—Then the Surgeon’s Discovery Stunned Everyone… CH2

Part I The lump started like a bad idea: small, ignorable, something you tell yourself you’ll “deal with later.” I…

My Dad Left Me On The Emergency Table Because My Sister Had A Meltdown – I’ll Never Forget This… CH2

Part I Antiseptic burns in a way that feels righteous. It bites the skin as if scolding flesh for failing…

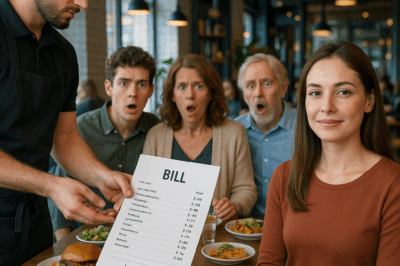

‘RACHEL, THIS TABLE IS FOR FAMILY. GO FIND A SPOT OUTSIDE.’ MY COUSIN LAUGHED. THEN THE WAITER DROPP… CH2

Part I The leather folder landed in front of me like a trap snapping shut. I didn’t flinch. I didn’t…

End of content

No more pages to load