Part I

Rowan spends the entire Sunday dinner being a cathedral. By the time Margaret sets the roast down and Peter clears his throat like a chapel bell, my husband has become pillars and arches and stained glass—all structure, no sound. It makes me itch. It makes me brave. It makes me stupid.

I decide, as Margaret shells out potatoes with the same rigor she reserves for opinions, that my best defense is offense. I have told myself this story so many times I mistake it for truth: fragility is a trap; boldness is a weapon. Men spin lies quietly and win; women tell truths loudly and pay. So I clear my throat and raise my glass and let my voice become the sharpest thing in the room.

“You know,” I say to the table where his parents sit and his siblings try not to, “it’s amusing how many of Rowan’s friends used to chase me before we married. Boldly. Persistently. All these years later they still—” I flutter my hand, a little flourish, a little harmless—“remember.”

Lydia’s fork pauses in midair. Alistair leans back the way neutral men do when they’re about to be drafted. Rowan’s jaw shifts by half a millimeter. He keeps eating.

I tell it bigger. I stretch the details like taffy until they shine. I describe a party, the balcony light against my dress, the hushed confessions that made Rowan look too slow, too safe, too late, while the daring ones circled. I turn myself into irresistible and him into the man who never fought for me. “If a woman’s honest,” I say lightly, “why must it embarrass men?”

Laughter comes thin and nervous, as if someone has told a joke and failed to pay for its landing. Eyes skitter. Margaret’s mouth becomes a scar.

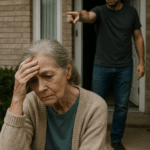

“Shameless,” she snaps, setting her fork down so firmly the crystal shivers. “You have turned marriage into a cruel public game.”

“Mother,” Lydia says softly, because she’s practiced this role too—temperate, buffer, bandage. Tonight even she looks tired.

I could stop here. I could pick a fight later in a kitchen with only one exit. But Naomi’s voice from our call this afternoon wraps around me like armor: You don’t owe them meekness. Silence is submission. Make them see you. So I think: Fine. Watch me prove I exist.

“I will not be bullied into pretending perfection,” I say, letting my voice crack just enough. “Honesty hurts worse than suffocation? At least it lets in air.”

Peter, who trains numbers as if they can be taught to heel, slides his napkin off his lap and folds it with both hands. “Respect,” he says to the linen, “has left this marriage already.”

Margaret lifts her chin like a verdict. “Your children will be ashamed of you for this,” she adds, aiming at me, then through me. “Isa already looks confused and weary.”

My daughter blinks, caught mid-chew by adults dropping stones in her river. Theo’s small jaw keeps working as if his mouth had never been taught the politics around food. I am suddenly aware of napkins and forks and the weight of my own hands.

But there’s a stage and I have always known what to do when the light finds me. “You’re all bitter,” I say. “You can’t tell a woman from a language you never learned.” I slam my fork down so it sings against the plate and rise with my bag. “You want me silenced because I am brave.”

Rowan never raises his voice, never lifts his eyes. He keeps eating. He is a metronome in a room of erratic drums. When I storm out, the only sound he makes is the scrape of a chair against wood.

Naomi answers on the second ring when I call from the car. “Never back down,” she says, after I pour the evening into her ear. “Judges of your character are always jealous. Men despise women who refuse to obediently adore.”

Her words are warm cloth. I wrap them around the moment’s shiver and drive home rehearsing new speeches. In them, I am a victim punished for honesty. In them, Rowan is basking in the silent approval of a family that prefers its women hushed and grateful. In them, I am art and he is a frame.

Rowan doesn’t come home that night. The other side of the bed stays a perfect museum, his pillow cool and uncompromised. At one in the morning, a fear I refuse to name taps politely on the back door of my heart. I push a chair under the handle and tell myself it’s because I like the look of it.

The week begins like any other: lunches, emails, the small logistics that make up competence. On Thursday there’s a knock. I expect a neighbor, a delivery, someone who will allow me to lean against the banality of packages. A man with a clipboard and eyes that have seen this a thousand times says my name. “Service,” he adds, as if that softens it. His hands are careful on the envelope as he gives me the kind of weight that changes your posture.

“Nothing to worry about,” I tell Isa and Theo, because the script requires reassurance, and hand them a remote as if cartoons can dilute law. Then I go to the kitchen and read the words that will become the floor under my next months.

Rowan has filed for divorce, and the letters tie themselves into a harness: primary custody, financial control for the children, visitation dependent on circumstances judged necessary. There’s an attached statement—his handwriting steady, his lists precise. He is building a case out of nouns: dates, times, receipts, screenshots.

It’s ego, I tell Naomi when I call her from the pantry, my voice as composed as a pianist’s fingers bleeding. It’s pride. He wants to ruin family life to punish me for being louder than his silence. “Cold,” she says, close as breath. “Classic.” Her assurance goes down like strong medicine. It doesn’t fix anything, but for a few minutes I feel less feverish.

Lydia appears with grocery-store flowers and the kind of cautious face you bring to a porch when you have to say something that will only hurt. “Rowan has a point,” she says to the bouquet. “What you… did… leaves marks. On him. On the kids.” She looks up then and her eyes aren’t judgment, just sad. “I defended you because I thought I knew what story we were in.”

Margaret calls and I let her voice fill the kitchen because sometimes the danger is the thing you know. “He has finally taken the right step,” she says, clipped like scissors. “Protecting his dignity and his children.”

Peter takes the phone for precisely two sentences. “Our son deserves peace,” he says. “The court will call it fairness. The word we use is overdue.”

I tell myself they’re all conspiring to erase me, that my truth has frightened them into a choreography they find easier than learning new steps. I call coworkers hoping they’ll perform the modern dance of solidarity. One says cautiously she warned me jokes can wound. Another says screenshots are difficult to explain away. They sound like people adjusting chairs to avoid glare. I hang up and call them cowards in my head.

That evening, Rowan comes to pick up the kids for dinner at his parents’. He knocks like a stranger. When I open the door, Isa launches into his arms like a creature that knows where weather lives. Theo climbs him as if his body is a playground he had been denied access to. I wedge myself in the doorway with a smile that feels like a plaster mask.

“You’re overreacting,” I say lightly, because my voice knows how to hold a room. “No court is going to reward cruelty disguised as paperwork. Our kids need their mother more than your… dignity.”

He hands me a folder without fanfare. “Look,” he says, and that one syllable is colder than any speech.

Inside, captured and printed and preserved with dates and times, are the messages between Callum and me. Harmless in my mind—teasing and late-night jokes and small admissions of thrill that once felt like small freedoms in the cage I said our house had become—now lined up like evidence does when the person with the envelope is not you. A smiley face at one a.m. A confession that the idea of being wanted by someone reckless had made me bright. A text about adrenaline that reads like infidelity if you peel away intention and look at impact. Callum never mattered, I want to say. It was nothing. It was air. It was unspent currency. The transcript doesn’t care. Judges seldom do either.

“It meant nothing,” I tell Rowan, fighting for eye contact. “Truly. He never… We never…” I gesture at the space in front of me, at the invisible, at the part of me I want to say is still virtuous. The gesture falls to the floor.

He doesn’t argue. He gathers their bags and buckles our son into his car seat with a competence I used to call boring. He guides Isa’s head under the strap and hands her a book with a quiet, “We’ll be back later,” like a promise he intends to keep on time. Isa glances at me the way children do when they’re choosing which parent is shelter tonight. She tilts toward his silence.

“Rowan,” I try, the name a key that no longer fits. “You’re breaking our family. This—these—are jokes. This is theater.”

He looks at me, finally, and for a second I think I see compassion, but it’s only steadiness. “Not everything that leaves a mark had to touch the skin,” he says. “I’m done being the audience.”

When he returns them, he moves through the house like a man collecting weather maps before a storm. Clothes into bags. Chargers into a tote. Shirts that have hung in our closet since the day after our wedding, when we promised to be the best versions of ourselves the other could love. The engine outside runs steadily, a metronome marking the death of improvisation.

“Are you coming back tomorrow?” Isa asks from the couch, coloring the calm eyes of a cartoon princess a frantic green.

“We’ll talk another time,” he says gently.

“Rowan,” I call into the hallway, his name losing letters as it moves. “You cannot… lock me out of my own house.”

He doesn’t answer. He closes the door. It makes no drama. I want to kick it for that.

Court moves faster than I imagined. One minute I am scoffing at paperwork; the next I am under fluorescent lights watching my husband in a dark suit sit exactly the way he sat at our wedding—hands steady on his lap, eyes forward, as if the ceremony belongs entirely to the notion of vow.

The judge looks like someone who has met every version of us and is no longer interested in pretending one is better than the other without evidence. The stack on his desk is taller than my pride. Receipts. Screenshots. Records. The messages with Callum that sounded like small rebellions when I sent them now sound like something I would tell my daughter to run from.

My lawyer leans in and whispers, “His case is organized with brutal precision,” and I want to stand up and announce that this is theater too, that Rowan’s calm is another kind of noise. Instead, I listen while his lawyer describes my behavior as humiliating, destabilizing, and harmful to children. The sound of the words in a wood-paneled room makes my bones shrink.

“Do you deny these words?” the judge asks, sliding the transcripts into the light.

I am an expert at talking, at filling space with the story I want to be true. But my mouth becomes an attic full of old boxes. I cannot find labels. “They were jokes,” I say finally, and the hollow in the word jokes echoes back at me across the room. I do not add: I thought honesty would be a shield. That I mistook performance for truth-telling. That I liked the way I felt when I was the most interesting person in a room, even if it was a room inside a phone at one a.m.

Naomi sits beside me and mutters that judges side with men, that optics coerce, that the law is a jealous god. Her words feel like a thin cloth stretched over a crack in a dam. Lydia sits in the back with her hands in her lap and her eyes on the floor. I look for her like a lighthouse. She refuses to be the shore this time.

The judge grants Rowan temporary primary custody, financial authority for the children, and restricted access for me. He uses the word stability, and it lands in my chest like a weight. Children need stability, he says, and stability lives where dignity lives. I want to shout that dignity is a cage built by people who have never needed to be loud to be heard. I want to announce that love is messy and I am brave enough to live in the mess. The judge isn’t asking for my dissertation. He is issuing orders.

Rowan leaves the courtroom with Isa and Theo holding his hands, their heads tilted toward him the way people lean toward warmth. I watch them go and suddenly I am the coldest thing in the building. Naomi squeezes my knee and whispers, “Unfair.” It lands like a cliche. For the first time since the dinner, her words do not heat me.

I go home to my townhouse—a thumbprint on a map that has always unlocked—and slide the key into the lock and twist and hear nothing click. I try again. I try the other key. I try laughter—“Very funny, Rowan.” I knock once, then twice, and imagine he is waiting inside to watch me learn a lesson. I tell myself he will regret this when he misses my spark, my sound, my light.

Behind the door, there is the muffled thump of children moving, the soft murmur of an adult voice, a laugh that used to belong to our kitchen. The house presses outward, steady and final. I rest my forehead against the wood and feel the cool of it like a mirror.

I could call Naomi and tell her the lock has conspired with the patriarchy. I could call a locksmith and demand access because my name is on the paperwork where romance used to live. I could sit down on the stoop and perform a sadness large enough for the neighborhood to learn and whisper about.

Instead, I walk back to the car, place my palms on the steering wheel, and wait for a feeling that is not indignation to arrive.

It arrives slowly, a leak under a door. It sounds almost like a word I used as a weapon at that table on Sunday. “Honesty,” I say into the quiet car. “Honesty, then.”

I take out my phone. I scroll through threads where my voice is a knife and other people’s silence has finally found its sharpened edge. I think of Rowan’s face at the table—unmoved, unworked—and realize I mistook quiet for cowardice when perhaps it was a dam holding.

My key doesn’t fit the lock. That is both fact and metaphor. The door doesn’t open because it has been rekeyed and because I broke something I didn’t want to name before I bent it.

Behind the door, my children laugh.

Somewhere between my hands and the steering wheel, I begin to feel like a person who has run out of applause.

Part II

The day after the lock refused me, my phone lit up with a number I didn’t recognize and a voice practiced at speaking to people like me.

“This is Claire Harper,” she said, crisp, clipped. “Family law. You emailed?”

I had, sometime between midnight and the hour the birds argue outside the window. I’d sent an inquiry with the word emergency in the subject line because I thought panic might bend calendars. Claire proved me wrong by offering me the slot between a motion hearing and lunch. “Bring everything,” she added. “Not the speeches. The paper.”

Her office lived in a building that smelled like history and toner. Claire greeted me with a handshake like a contract and pointed to the chair across from a desk that had never known clutter. She had gray at her temples and no patience for metaphor.

“Tell me why you’re here,” she said, and when I opened my mouth, she held up a finger. “In nouns first. Then when you’ve run out of nouns, we can talk about adjectives.”

I put the envelope on the desk. I said divorce, custody, screenshots, service. I said Callum like the word tasted worse than I remembered. I said jokes and then shut my mouth because of the way her eyes flickered.

She flipped through the stack with the fluency of someone who’d seen too much and stopped being impressed by originality. “He’s organized,” she said. “Steady. Efficient.”

“You say that like it’s a crime,” I snapped, and hated the sound of it even as I said it.

“I say that like it wins,” she returned. “I assume you want outcomes. Outcomes require discipline. First: stop giving the court a live feed of your worst self. No public posts. No commentary. No subtweeting the father of your children. Second: stop calling his family to audition for sympathy. They are adverse parties now. Third: do not call your affair partner. He is evidence you cannot contain.”

“He wasn’t—” I started, and Claire didn’t bother to raise an eyebrow, which stung worse than if she had.

“It doesn’t matter what you wanted him to be,” she said. “It matters what a judge hears and what your daughter heard when you laughed at dinner about men wanting you. You’ve turned pain into theater. Judges are not critics.”

I reached for indignation because it’s the only thing I can locate without looking. “So what—you want me to sit here and let him narrate me into a villain? Are we… performing decorum until men decide they’re satisfied?”

“I want you to sit here,” she said without heat, “and learn the difference between silence and strategy. The court is a language. Right now you’re shouting in English to a room that only hears evidence.”

She slid a sheet across the desk. Temporary orders protocol. Two columns. His obligations, mine. Checkboxes that looked harmless.

“Sign up for the co-parenting class,” she said, pen tapping a line. “Enroll in therapy with a court-approved provider. Document attendance. No overnight visitors unless you want those screenshots to become arguments about instability. And call this evaluator. Bring them your humility. I know you have some.”

I do. I did. It had just been living in a basement behind the other furniture.

“What about my kids?” I hissed, because love sounds like threat when it’s backed into a corner. “Isa needs me. Theo needs—”

“Stability,” she said flatly. “The judge already said it. You don’t get to override that with your feelings. You want more time? Build trust. With the court. With the father. With your children, who are now watching to see whether you will love them more than you love your own voice.”

I left clutching a list of classes and therapists and words I’d always laughed at: accountability, repair, boundaries. Outside, the day was bright in a way I resented. I sat in my car and drafted a post Naomi would applaud—something about women being punished for honesty, for heat, for refusing to be good—but Claire’s finger hovered in my memory: no public posts. I put the speech in Notes instead of the internet. It stayed there like a feral cat, pacing.

Naomi came over with coffee and a look that said rebellion like a picture frame. “We go nuclear,” she declared, collapsing on my couch. “You post your truth. You name names. You call the lockout what it is. Manipulation.”

“That would violate the temporary order,” I said, surprising both of us. “Claire says—”

“I do not care what Claire says,” she snapped. “Claire works for the system.”

“Claire works for me,” I said, and watched the words upset Naomi’s arrangement of me in her head.

She asked to see the screenshots. I handed over the folder because part of me still needed someone to say this is nothing. She scrolled, and when she looked up, the pity in her face wasn’t for me. “You gave him a sharpened knife,” she said. “I can rationalize a kiss. I cannot rationalize turning your husband into an audience and asking strangers to clap.”

“I didn’t kiss him,” I said, small.

“You wanted the idea more than the act,” she said. “The court won’t care.”

She stayed an hour, building me a tent out of her outrage. When she left, the house breathed like it hadn’t been allowed to in months. I sat at the kitchen table and wrote out Claire’s list in my own hand: Class. Therapy. Evaluator. Then, because I felt the thing I avoid most—quiet—I did something that startled me. I called Lydia.

We met in a café that smelled like cinnamon even when no one ordered it. She arrived early, a habit we share from before our lives wanted different things. She had a book in her hand and circles under her eyes.

“I used to defend you,” she said, before I said hello. “Because I believed the story where you were the fire we needed. At dinner, at birthdays, at funerals, you made oxygen. I didn’t realize you were turning fire on my brother.”

I wanted to argue that he basked, that he benefitted, that he had asked for my heat and then built a coat rack for it. Instead, I kept my mouth still.

“He has a notebook,” she said. “He wrote in it after nights no one saw. Don’t use this in court,” she added quickly, palm up. “I’m not handing you anything but perspective. He wrote down dates when you made jokes about men in front of the kids. Times you told stories about him being…slower than the others. The morning Isa asked me if love means making someone smaller in front of people. Sometimes when he looked steady he was dealing with dizziness.”

“You think I don’t love him,” I said, and hated how childish it sounded.

“I think you love being watched,” she said gently. “And you forgot that your children were watching you while you watched yourself.”

There wasn’t a place to put that sentence that didn’t involve bleeding. I put it into my purse and paid for our coffees.

As we stood to leave, Lydia reached for my hand. “You can fix this,” she said, and she meant with them and with yourself, not with him. “But you have to choose boring. For a while. On purpose.”

Choose boring. The words made my throat close on a laugh.

The court evaluator’s office was beige in a way that performed neutrality. Her name was Dr. Foster and she did not do small talk.

“You understand why you’re here?” she asked.

“I humiliated my husband in front of people,” I said. “Repeatedly.” I had practiced the sentence driving over. Dignity tastes like a coin when it’s new in your mouth.

“And?” she prompted.

“And I texted another man about my…thrill,” I added, the word making me roll my eyes at myself.

“And?” She was going to make me say all of it.

“And I told myself honesty was noble,” I said. “That performance was activism. That if he was quiet he was oppressive. I thought rules were for women who weren’t brave enough to break things and then build them back prettier.”

“Does your daughter look prettier?” she asked, changing nothing about her tone.

I closed my eyes. “No,” I said. “She looks tired.”

Dr. Foster wrote a note. “You will take a co-parenting course,” she said. “You will attend therapy and have your provider send proof of attendance. You will keep a log of your visitation and you will not be late or early by more than five minutes. You will not introduce any romantic partners to your children for a minimum of six months. You will not mock the father of your children to anyone but your therapist.”

I wanted to ask what I would talk about, then shut up because old reflexes die loud.

“Bring your humility,” she finished, as if it were something you could tuck into the pocket of your coat and check for before leaving the house.

Hand-off days arrived like weather. Rowan parked curbside and walked them to the door with backpacks that looked suddenly enormous on small bodies. The first time, I tried to kneel and have a moment and Isa stepped past me to the couch and held up her homework. “Can we do this?” she asked. I sat with her because you accept the invitations you are offered.

The second time, I told him about Isa’s school project aloud, so he would hear I was learning the language Claire had taught me: information, not invasion. He nodded, wrote something in his phone. “Thank you,” he said, almost like he meant it.

The third time, I threw away three paragraphs right before I said them. Instead, I showed him the calendar the court had ordered us to keep in the cloud. “I put her class performance on here,” I said. “I won’t… show up. I’ll watch the video if you send it.”

He glanced at the line that said First Grade Play — 6:00 p.m., and looked surprised. “Thank you,” he repeated, and this time his voice sounded less like an echo.

The children learned my new quiet slowly. Isa stopped flinching when my phone lit up. Theo clung less to his father’s forearm at the door and reached for my hand on his way to the bathroom because even mercies are mundane. The first night I had them for dinner, I set the table without speeches. We ate spaghetti—no bouquet of adjectives. “How was your day?” I asked. “Yummy,” Theo said. “Math was hard,” Isa said. “We’re allowed to say that now,” she added, as if she had discovered a new law and wanted credit.

I went to the co-parenting class the court ordered. It met in a room too bright with diagrams of human brains and words like regulation. There were eight of us: a man who spoke about his ex as if saying her name might summon her; a woman who apologized to the coffee machine when it dispensed too much creamer; me, trying not to perform being the best student. The instructor, a woman with biceps like competence, wrote Children Are Not Mail on the board.

“You don’t use them to deliver your hurt,” she said. “You don’t schedule your pain around their calendars. You do your crying offstage. You tell the other parent information that matters—eating, sleeping, school—without editorial. You do not keep score in front of them. You let them love both of you without penalty.”

“I’m not keeping score,” I blurted, then looked down at the notes where I had tallied every missed call Rowan had not answered.

“Keep score in your journal,” the instructor said. “Not in your children’s gaze.”

Callum sent one text after months of silence: Saw the news. You okay? I stared at it until the letters stopped meaning anything. I typed You made me feel alive and deleted it. I typed we were idiots and deleted it. I typed Please don’t contact me again and sent it. Then I blocked the number and felt a small phantom limb pain I refused to admit out loud.

Naomi kept texting links to think pieces about men weaponizing dignity. I sent heart reactions to three, then silenced our thread for eight hours that turned into a day that turned into by default. When she called and asked why I had stopped letting her rev me like a string, I said, “I have to build trust with my children. I can’t do it on adrenaline.” She exhaled in that way she does when she thinks I am abandoning the sisterhood for a picket fence. She hung up without saying goodbye. The silence she left behind felt like weight removed, not added.

Lydia sent a photo of Isa and Theo at their grandparents’, faces sticky with jam, workbooks open, Margaret teaching them fractions as if math could heal. I stared at the picture a long time, then typed, Thank you. For loving them in rooms I’m not in. She responded, Love makes room. Keep doing the boring things.

I held my thumb over Rowan’s contact. Calling him to confess felt like asking the judge to reverse a ruling; writing felt like the only way to speak without turning it into a stage. I wrote a letter and did not give it to Claire or to the court or to Instagram. I wrote I am sorry I taught our daughter that humiliation is a form of love. I wrote I am sorry I turned our home into a theater and our dinner table into a club where I could test my material. I wrote I will not ask you to undo the lock. I will ask you to watch for the long boring proof that I can be a grown-up.

I slid the letter under his door the day my key couldn’t change it.

A week later, at handoff, he said, “I read your letter.” He didn’t add adjectives. He added a line on the calendar: Family Therapist — joint session (as needed). For the first time in months, I believed as needed might include me not because I demanded it but because I had earned it.

Court again, a month later. Temporary orders becoming permanent in the expressionless machinery of the system. Claire sat with me and the judge used words that sounded like finality and mercy in an uncomfortable blend: shared custody schedule, primary residence, decision-making, review in a year. The beginning of a life with boxes to check instead of rooms to break.

After, Claire clasped my shoulder. “You did well,” she said. “You didn’t turn your answers into essays.”

“I wanted to,” I said.

“I could tell,” she said. “Wanting is not failing when you choose otherwise.”

On the way out, we passed Margaret and Peter. She touched my wrist. It was the first time she’d touched me since my wedding day, when she had placed her lips near my ear and said be kind to my son. “We will make room,” she said now, as if she had heard Lydia’s text without us saying it. “You have to fill it with your better self.”

I drove home and hung a calendar in the kitchen and filled in school concerts and therapy and Isa’s shoebox diorama due and Theo dentist. I added co-parenting class in block letters so I couldn’t pretend I’d misread it later. I wrote call therapist on Fridays because I have learned that I lie to myself most convincingly at 4 p.m. before the weekend. I wrote dinner—boring on Tuesdays and then laughed.

At six, I showed up at the school auditorium and sat in the back corner with my hands folded correctly. Rowan sat two rows down with his parents, the kids between them like punctuation. The music teacher counted down with too much enthusiasm and Isa sang loudly and off-key the way only children who feel safe do. After, Rowan turned and nodded, and I nodded back, and no one threw speeches at anyone else.

I went home to the townhouse where the new key made the right sound. I set out two bowls, poured cereal, ate one, washed both, and let the quiet be something other than punishment.

The next morning, I woke without rehearsing a defense. I made coffee without drafting my closing argument. I texted Claire a question about a clause in the order. I texted Lydia a picture of Isa’s concert program. I texted Rowan a screenshot of a science fair sign-up and asked, Do you want volcano or solar system? He wrote back, Solar system. I’ll get the foam balls. Three words that sounded like co-parenting in the language Claire had promised I could learn if I stopped demanding it be taught to me in mine.

I am still not gentle by nature. The words gather at the back of my tongue like birds, wanting sky. But I have learned the shape of a different kind of strength: the will to sit on my hands while paper does its work. The discipline to let my children tell me about their day without suing my husband through their stories. The patience to let the calendar prove me.

On a Thursday night after a long day of doing nothing impressive, Isa asked me why I wasn’t funny anymore. “I’m trying a new joke,” I said. “It’s about growing up.” She frowned. “It’s not very funny,” she said.

“Give me time,” I said. “I’m working on the delivery.”

When I put them to bed, Theo asked me if Daddy would still come tomorrow. “Daddy always comes when the calendar says,” Isa answered for me, with the authority of a girl who had learned to depend on boxes and not brags. “Mom does too.” She turned to me, eyes searching, needing me to say yes and not decorate it.

“Yes,” I said. She smiled, the tired kind that lives in kids who are re-learning a truth you can’t unteach: love is boring, and that is its mercy.

I left their room and sat on the top stair and pressed my palms together over the phone I didn’t raise. Naomi’s unread messages glowed like flares in the dark. I opened our thread, scrolled up through the liturgy of outrage, and then, without drama, muted it for a year.

Then I did something even less impressive. I set my alarm for the time the co-parenting class starts on Saturdays and went to bed sober on humility.

Outside, the lock clicked when it was supposed to. Inside, no one applauded. It felt like peace.

Part III

The co-parenting class meets in the basement of a church that smells like multipurpose. By the second Saturday, I know which chair wobbles and which outlet works and which of us will cry when the instructor writes YOUR CHILD IS NOT YOUR WITNESS on the whiteboard and circles it like a verb.

We practice sentences that feel small and therefore impossible.

“Thank you for the update.”

“I can pick up at 5:15 instead of 5.”

“I’ll send the medication list in writing.”

We practice saying nothing else. We practice letting the period be the bravest thing in the room.

After class, a man named Victor stands in the parking lot holding his keys like opinion. “I used to send her essays,” he says to me, rueful. “Now I send her bullet points. The first month made me itch. The second month made me sleep.”

That afternoon, I put a sticky note on the inside of the front door: Bullet points. Not ballads. Isa reads it when she comes back the next day and snorts. “You love ballads,” she says. “You only like bullet points when you’re mad.”

I want to argue with a nine-year-old. Instead, I hand her a pencil. “Write me three,” I say. “About your day.”

She thinks, tongue between teeth, then prints in blocky letters:

Math hard.

Liam says dinosaur is bird. He wrong.

I miss socks with cats.

I tape her list next to my note. “We can be a list family,” I tell her. She considers. “Only if the lists have stickers,” she says, already rummaging in the drawer.

On Wednesday, Claire emails a reminder about the evaluator’s mid-point check. Dr. Foster schedules it for a Tuesday at 11:10 a.m., the kind of time that punishes people with jobs. My boss at the library nods, says, “Go—family is a book you keep renewing,” and waves away my apology.

At Dr. Foster’s, I sit in the beige chair and do not perform. She asks about class attendance, therapy, the calendar. I show her screenshots, receipts, the open app with blocks of time colored like a patchwork. Proof of boredom. Evidence of ordinary.

“Have you refrained from disparaging the other parent in front of the children?” she asks, eyes steady.

“Yes.” The word feels earned. “Once I started paying attention, I realized even rolling my eyes at a text makes Isa hold her breath.” I swallow. “I didn’t know until I watched her watch me.”

“And Naomi?” she asks, because evaluators hear the names that live in your sentences.

“I muted her,” I say, then add quickly, “for now.”

Dr. Foster nods as if I’ve put a tool back where it belongs. “Boundaries are not betrayals,” she says. “They are fences you build around the parts of yourself you are trying to protect.”

I don’t mention the other fence—that my key doesn’t work in the old lock anymore. That sometimes I sit in my car outside that door and rehearse speeches I will not give.

At the first joint therapy session, Rowan sits on the couch like a man at the dentist—resigned, wary, prepared to bleed neatly. Dr. Loomis has moved us into her larger room, the one with the window you can stare out when you run out of words. She has tissues in a place that requires crossing your own knees to reach them. She knows the choreography of accountability.

“I asked you both here,” she says, “because co-parenting is a relationship whether you like it or not. You will have contact with each other for the length of your children’s childhoods and many days after. Let’s decide what kind of contact.”

Rowan’s hands are flat on his knees. I don’t think I’ve ever noticed his hands before as anything other than instruments of competence—fixing a toilet, cutting apples, driving kids places. Today they look like work made visible.

“I’m not here to resuscitate our marriage,” he says, voice even. “I’m here to stop making our kids choose a weather.”

“Yes,” I say, because the right thing, even from his mouth, is still right.

Dr. Loomis looks at me. “Ashley,” she says, “tell him what you are doing differently that he can reasonably be expected to notice.”

I take a breath. “I haven’t posted about you,” I say, heat rising anyway. “I haven’t called your parents since court. I send you medical updates. I am never late for handoffs. I do not talk about what happened with Isa and Theo. When Isa says she misses your house, I say, ‘Of course you do. You have two homes.’ When Theo says he wishes all four of us could eat spaghetti together and make fart noises, I say, ‘Me too,’ and then I stop.”

Rowan rubs the side of his jaw, a habit I recognize now as thinking and not disdain. “I noticed,” he says. “I also noticed you bought Isa socks with cats on them and didn’t tell her dad he was frivolous when he bought her sneakers.”

“I used to think thrift made me morally superior,” I admit, and we all pretend we do not hear the word used. “Turns out it just made me mean in a way that looked exactly like virtue.”

“What do you need from Rowan?” Dr. Loomis asks.

I almost say, to put the lock back the way it was, and then realize that door is not the door that matters. “I need you to answer texts even when they annoy you,” I say instead. “I need you to hand me their backpacks without comments about chaos. I need you to let me earn back time without the fear that you will highlight my slip and use it as proof of a thesis you wrote months ago.”

Rowan’s mouth moves like he might smile and then decides against it. “I need you to stop watching me for a performance,” he says. “My silence was not a script for you to act against. Some days it was the only decent thing I could give our children.”

“I thought the quiet was cowardice,” I say.

“I thought your loud was courage,” he counters. “It was sometimes. It was also cruelty.”

We sit with that. It is a scale that refuses to settle so we learn to live with the needle.

Dr. Loomis gives us homework because healing requires chores. “One email a week that is nothing but logistics,” she says. “No adjectives. Try this: bullet points. Attach a photo of a calendar if you must. Reinforce the new language until it becomes your children’s dialect.”

On the way out, we pass a bulletin board in the waiting room. Isa’s group art—collages titled My Safe Place—hangs alongside other child-bright testimonies. Isa’s shows our living room in crayon, two couches, two doors. In the middle she has drawn a table with spaghetti and a pair of hands clapping. There are no faces. I cry in the parking lot like a person who has run out of costumes.

Margaret calls and asks to meet me at the garden behind the museum. “Not to fight,” she says. “To speak.” The last time she asked to speak with me was the morning of our wedding, when she handed me a pin with Rowan’s great-grandmother’s initials and said, “Hold my son’s spine like it’s yours too.” I didn’t understand then. I’m not sure I do now.

We sit on a bench with backs too straight for comfort. She wears cream as if grass cannot stain her.

“I have rehearsed a dozen versions of this,” she begins without preface. “The one with the most mercy starts here: I was cruel to you at dinner. It was not undeserved cruelty, which is not a category I believe in, but it was a performance too. I like to pretend I do not perform.” She bites her lip, a gesture that looks odd on a face trained for verdict. “You made me feel powerless and I punished you for it. It was not good.” She exhales. “I am sorry.”

I do not know what to do with this softness. I hold it like something you find on a path—warm from the sun and surprising.

“I have sons,” she continues. “I have never trusted the world to be kind to them, so I taught them to be stone. Rowan learned that too well. Your loudness was weather he had not trained for. The truth is both of you thought you were protecting my grandchildren. You were protecting yourselves. The door needs to be open for their love, not closed for your righteousness.”

“I told myself I was honest,” I say. “That righteousness was a gift and silence was a lie.”

“Honesty without gentleness is a weapon,” she says, looking at the fountain. “Silence can be courage. So can speech. You have only ever loved one of those ideas.”

“Do you think I can fix it?” I ask, hating the begging in my voice.

“I think you can build what you broke,” she says simply. “With bricks. Slowly. Children like floors they can run on without watching their feet.”

When we stand, her hand finds my shoulder. It feels like being given a key that does not open a door but perhaps a window.

Naomi shows up without texting, righteous in a denim jacket with a patch that says LOUD WOMEN SAVE THE WORLD like a label. “I’m worried about you,” she announces, making space on my couch for her indignation. “You’ve gone quiet.”

“I’m learning strategy,” I say. “Quiet is not surrender.”

She huffs. “He’s turned your personality into a weapon and the court handed him ammo,” she says. “You want to know what I would do?”

“No,” I say, and it lands between us like a sudden winter.

She blinks. “Excuse me?”

“I’m in a system that doesn’t care for my essays,” I say, hearing Claire like a ghost with a gavel. “My children need my boredom more than they need my manifesto.”

“This is you choosing him,” she says, already texting someone her disappointment.

“It’s me choosing Isa and Theo,” I say. “And me, frankly. Because I like sleeping.” I draw a breath. “I love you, Naomi. I can’t use you right now.”

She stares, and for a second I see the part of us that only knew how to inhabit rooms where our volume was our armor. She stands, knocks over a coaster with her knee, and leaves without the punctuation of a door slam. The quiet after is not peace, not yet, but it is breathable.

I text Claire: I ended a friendship. It hurts. It also feels like not pouring gasoline on something.

She writes back: Proud of you. The boring victory is still a victory.

In late spring, we go back to court. Permanent orders. Review of progress. Summary of logs and classes and what the evaluator has decided about my spine.

Claire and Rowan’s attorney confer in the aisle like two kinds of weather learning to agree on a forecast. Dr. Foster testifies in the understated way professionals do when they know how easily adjectives can be used against any of us.

“Ms. Harper’s client has complied with all interim requirements,” she says, which makes me feel like I passed a test I didn’t want to take. “Co-parenting class, individual therapy, joint sessions. She has refrained from public commentary for the duration of the order. Exchanges have been on time. No incident reports.”

The judge asks me if I have anything to add. A month ago, I might have tried to craft a scene. Today I let my hands rest on the table and say, “I would like more time with my children. I’m asking for a weeknight dinner to become an overnight. I’m asking for alternating weekends and mid-week calls that are on the calendar. I’m willing to build into it. I do not want them to have to keep learning new weather.”

He looks at Rowan. My husband—man I love, man I harmed—clears his throat. “I’m in favor of expanding,” he says, and I feel the floor under us shift a bit toward level. “She has done what the court asked. So have I. Our kids are doing better when we do our boxes. I’d like to keep that going.”

The judge signs orders that have the same force as the temporary ones but somehow bruise less. Shared custody increases in measured inches—alternate weekends, Wednesday overnights, holiday rotations mapped out in a grid like a consolation prize that grows to feel like a plan. Decision-making remains joint with tie-breakers, the ink boring as mercy. Review in a year. A year of practice. A year of not auditioning. A year of bullets instead of ballads.

In the hallway after, Claire squeezes my shoulder. “I know you wanted the judge to notice your hair is different,” she says dryly. “He noticed your calendar. Well done.”

Rowan lingers and we do not do the thing where divorced people pretend they are old friends in a movie. He holds out a single sheet—a print-out of the summer schedule. “Isa wants to build a volcano,” he says, as if he is handing me a gift. “Solar system can wait.” His mouth tips at one corner. “She made a list.”

“Bullet points?” I ask.

“Stickers,” he says, and for a flicker we grin at the same joke like the same people.

The first Wednesday overnight feels like inaugurating a small nation. Isa shows up with a backpack that looks like it contains a year. Theo is carrying three stuffed animals and a banana he refuses to let go of until I peel it and then he refuses to eat it. We work out the choreography of shoes and bath and homework and decide on tacos because they feel like a win even when you mess up the spice.

At bedtime, Isa sighs at the ceiling. “This is weird,” she says, a blanket over her knees like a formal gown.

“Yes,” I say. “We can let things be weird until they learn to be normal.” I tuck her hair behind her ear. “Thank you for your list.”

She squints at me. “You say sorry different now,” she says.

“Better?” I ask, because mothers are always asking for grades they pretend to hate.

She considers. “Less like you’re trying to win,” she says. “More like you’re trying to be.”

After lights out, I sit on the floor in the hallway and lean my head back against the wall. I count to one hundred and back down the way the therapist taught me to do when panic tries to become chore. In the dim, I hear them breathing. It is the sound I didn’t know how to earn. It is the music of a house that once performed and now practices.

My phone buzzes with a text from Lydia: Mom wants to say something to you. She says she’ll write it. Dad says he’s making peace with boring. He made a lasagna for practice.

A minute later another text arrives—from a number I don’t have saved but recognize by the shape of it. Thank you for building with bricks, it reads. No signature. No adjectives. I stare at it, then type back, just as plainly: Thank you for leaving the door cracked when you could’ve shut it. I won’t slam it.

I put the phone facedown. I go to the kitchen and set out bowls for the morning without narrating to nobody about the virtue of cereal. I hang the kids’ list of Saturday library events on the fridge. I put the calendar back on the counter where it belongs instead of in my pocket where I can turn it into a weapon.

Then I do the bravest boring thing I know how to do. I turn off the house. I walk to my own room. I sleep.

Part IV

Summer arrived humid and unapologetic, and with it the science fair. Isa picked volcano first, then changed her mind after reading a book about nebulae with a librarian who wore earrings shaped like comets. We spent a Saturday afternoon on the floor, foam balls and skewers and paint everywhere like a galaxy that had misbehaved. Isa assigned roles. “Dad: sun and Jupiter,” she said, because he’s steady and big. “Me: Earth, because I’m the main character.” She looked at me. “You can do Saturn. It’s pretty and complicated and sometimes people don’t know how to look at it without a telescope.”

“Bullet points,” I murmured, reaching for the ringed world, and she rolled her eyes like a girl who still liked me.

We met Rowan at the presentation night and stood in a triangle at the edge of the gym as Isa explained to her teacher why Pluto hadn’t been invited. “It can come to the party anyway,” she added graciously. When the ribbons were handed out and a kid with a papier-mâché tornado cried because weather is unfair, Rowan turned toward me. “Joint camping trip at the end of August,” he said carefully. “Two nights at the state park. Separate tents. Same fire. Intermittent truce.”

“I can do intermittent,” I said. “I’m in training.”

We booked adjacent sites. Our children learned that parents can argue about how to arrange firewood without burning down a forest. On the second night, after s’mores and skinned knees and Theo losing his mind over a moth the size of his self-worth, the four of us lay on our backs on a tarp and counted satellites. Isa pointed to a steady light and asked if I was still mad at the sky. “No,” I said. “I’m trying to make friends with it.”

Rowan chuckled in the dark. “Look,” he whispered. “Perseid.” We all gasped like we had rehearsed.

I completed the co-parenting class and got a certificate that looked like a diploma from a high school that refused to teach prom. The instructor stapled a gold star to the corner and said, “You do ordinary with style.”

In therapy, Dr. Foster signed a form and said the court appreciated my punctuality. I wanted to tell her my punctuality was fear wearing a watch. I didn’t. Every yes from an evaluator is a fragile thing.

Naomi texted occasionally, usually links to essays about the radical act of joy for women who had been told to be small. I hearted some. I forwarded others to a folder labeled Later. Once she wrote, He will never love anyone like he loved you, and I surprised myself by typing, He will love our children best. That’s what matters. The typing dots pulsed, then stopped. We are learning new kinds of quiet, separately.

Margaret wrote a letter that arrived in monogrammed envelope like an apology in high heels. It was short and formal and, irritatingly, beautiful:

Ashley—

You married my son. I have hated you too quickly and loved you too slowly. I am trying to do both in better order.

I want to teach Isa how to make a pie crust that does not crack. I need you to allow me to stand beside you while she learns. I will not turn the lesson into a referendum.

—M.

I stared at the paper for a long time, then penciled on the bottom: Sunday, two o’clock. Bring butter. I sent a picture of it to Lydia, who wrote back a string of exclamation points and then, in a second message, Proud of both of you. Mom practiced signing her name with less flourish. It makes her look softer.

On Sunday, Margaret arrived with cold butter and the kind of patience I used to mistake for control. Isa stood on a stool and learned to cut fat into flour. “You’re allowed to re-roll once,” Margaret said. “Twice if the gods are kind. Thrice and you are making paste.” Isa looked at me. We all laughed, a studio audience for the smallest good show.

In September, I took the kids to the library and watched Isa shelve herself in nonfiction, spine-straight and curious. Theo ran to the train table and immediately invented a game where the order of engines mattered less than it used to. Rowan texted a photo from his parents’ house of Theo asleep on Peter’s chest with a book face-down on the armrest. Bullet point: He’s pretending the trains are planets again. I replied, Tell him the solar system misses him.

When school started, Isa had to fill out the “All About Me” poster. In the square that asked for “favorite sound,” she wrote, in her small, halting script: quiet spaghetti. When she showed me, my eyes stung. “You put it on the table softly,” she said, as if she were describing a poem. “And we eat it and no one says I’m a show.”

I put the poster on the fridge. “I’m keeping this forever,” I told her. “When you’re thirty and mad at me for something else, I’ll remind you that your favorite sound was my boring.”

Callum sent one last message in late October, a paragraph of mea culpas that had the familiar cadence of a man who thinks regret can convert into romance if he conjugates it correctly. I read it once. Then I forwarded it to Claire with a single line—Just in case this becomes noise in a room where I cannot control the volume—and then, without a speech to the past, I blocked the number. I did not tell Naomi. I did not write a poem. I wrote buy milk on a sticky note instead. Growth is stupid and unsexy most of the time.

By winter, the review hearing was on the calendar. Claire dragged a neon highlighter across the date and said, “Eat protein that morning. Courts are a marathon disguised as a waiting room.”

Dr. Foster sent a letter that could have been a haiku: Compliant. Cooperative. Consistent. My chest loosened. I didn’t realize my ribs had been guarding the old shape of panic.

On the way to court, Rowan saw me in the hallway adjusting my scarf and handed me a Wint-O-Green Life Saver from his pocket without commentary. We are not friends. We are weather that has learned to respect yield signs.

The judge reviewed the checklist like Santa stubbornly committed to the bit. He nodded at logs, at attendance, at an absence of complaints. He made the Wednesday overnight permanent, gave me alternating weekends with Sunday night returns, added a mid-week dinner that could become a second overnight at the six-month mark without another court appearance if the calendar kept proving me. “You’ve both been boring,” he said, which I decided to accept as the highest possible praise.

After, in the hallway with the vending machines, the four of us stood together and Isa asked, “Does this mean we don’t have to ask every time?” and Rowan said, “It means the boxes got bigger,” and I said, “It means we’re doing a good job,” and Theo said, “I dropped my cracker,” because he’s three and the universe remains correctly ordered around that fact.

We walked out into winter light and the breath we made looked like smoke signals. Rowan swung Theo into the air and Isa rolled her eyes in fourth grade and tugged my coat sleeve. “Hot chocolate at your house?” she asked, negotiated eyebrow lifted toward Rowan. He looked at his watch, then at me, then at the sky. “Two hours,” he said. “Text when you drop them off.” Bullet point, not ballad. I nodded. We both smile-sighed at the same time and then pretended we hadn’t.

December became a truce disguised as routine. We decorated two trees with the same boxes of ornaments, fingerpainted the same old wreaths, baked the same cookies in two ovens from the same recipe. Rowan brought the kids to my building’s ugly holiday party and stood in the back while Isa showed Theo how to smear frosting on a paper plate and then eat it with a spoon. Whenever someone asked us “How’s it going?” we both said, “We’re learning boring,” and people laughed like we were making a joke. Maybe we were.

One night, Isa’s school held a winter concert. In a packed auditorium that smelled like felt and sugar, the class sang an off-tempo version of “Dona Nobis Pacem,” which is Latin for give us peace and felt like a dare. Rowan sat three chairs away with his parents, and we clapped at the right times and did not nudge children toward anyone’s camera when it wasn’t their turn. While we waited for the fourth-graders to stop playing bells like toddlers with pots, Margaret leaned toward me and whispered, “He looked at your letter for a long time before he slept next to it that night.” I nodded like a person who knew how to accept a new kind of fact.

After the concert, Isa located us both with the radar children own. “You both here,” she said, as if tallying team members. “So we all get ice cream.” There are some negotiations you do not take to court.

At the ice cream shop, Theo dipped his cone in my hot chocolate and everyone pretended not to notice because it was the kind of joy we had missed. Isa told us about a girl who had pulled her braid on the playground and how she had practiced saying “I don’t like that” the way Mrs. Patel taught them in health. “I did not shout,” she said. “I used my inside voice with edges.” I caught Rowan’s eye and we both glowed across the table, a silent high five.

“Inside voice with edges,” I repeated on the drive home. “That’s our whole life now.”

Isa nodded. “It’s better,” she said. “My ears don’t get tired.”

In January, Naomi and I ran into each other at the farmer’s market, because cities are small communities wearing big coats. She looked at me like I had chosen a different planet. “I miss you,” she said, the words tight. “I miss… us.”

“I miss the parts of us that were right,” I said. “I don’t miss the parts that made me bounce my children off my speeches.”

She looked at my basket—four apples, two onions, a loaf of bread. “You used to be… more,” she said, a little mean because mean is easier than grief.

“I’m being different,” I said. “I do not owe the world my volume at all hours.” I wanted to say I learned to hear other people, but the market was loud and I am superstitious about speaking too much into the open air. She nodded once, then twice, then walked away. We are still not built for the same weather. That, too, is a boring truth I can live inside now.

By March, the novelty of ordinariness had worn off and what was left was better: muscle. I showed up because the calendar told me to and not because I had a speech. I sat on the edge of the bathtub while Theo narrated a story about a dinosaur who learned to say sorry without prompting. I taught Isa how to fold fitted sheets because if something on earth requires humility, it’s cotton and elastic and physics.

On a Tuesday in April, Isa got scared during a storm and called it “too much sky.” Rowan texted me: Thunder at 2 a.m. I told her it can be loud and not be mad. I sent back: I used to think loud meant mad everywhere. I’m trying to be weather, not warning. He wrote, Me too, and I believed him because the proof was not adjectives; it was kids who were sleeping through.

Spring break meant a week of juggling. Claire would have been proud of the spreadsheet I didn’t show her. We split time fairly and Isa only cried once when she realized she’d left her stuffed fox at my house because custody agreements do not extend to plush toys. At handoff, Rowan stood in my doorway, Fox cupped in his palm like a bird. “Emergency order,” he said dryly. We both laughed, too quickly, then said goodnight like people learning to say basic words properly.

At the end of that week, Rowan asked if he could come inside to see the kids’ art. I stepped back and let him enter even though my house was doing that thing where it performed living. He stood in the hallway and looked at Isa’s galaxy poster and Theo’s train drawings and the sticky note that still read BULLET POINTS. NOT BALLADS. He stared at it as if considering gratitude, then nodded at the list of summer camps I’d taped below it with pickup and drop-off times in neat columns. “Thanks,” he said. “I’ll log these.”

He paused at the door. “When you laughed about my friends wanting you,” he said, and I braced because old me would have been ready to rehearse. “I felt… less than. Not because of their wanting. Because of your delight in my smallness.”

“Mine too,” I said. “I was making everything small so my jokes could be big.” I shrugged, because old me would have tried to make it poetry. “I’m done with that part.”

He nodded once. “Me too,” he said, and left.

The one-year review came in June under a sky that wasn’t trying to be anything but blue. The judge scanned the file and used words like continue, modify, increased, sustained. It was less dramatic than the first time and more important. He left intact the overnight and added another midweek one when summer ended, “subject to continuation of compliance.” Claire squeezed my hand under the table, a small punctuation.

After, in the hallway, Isa ran to us from a bench where Margaret had bribed her with graham crackers and patient stares. “We did it,” she said, and then, in a whisper that felt too big for her mouth, “We kept the boxes.”

When we walked out, the sunlight hit our faces and I thought, suddenly and unashamedly, of that first sentence I said at a table I mistook for a stage: I laughed that some of his friends tried me. I watched myself grin at my reflection in everyone else’s discomfort and call it honesty. I remembered how righteous I felt when I stormed out and called the lock a conspiracy instead of a boundary.

Rowan’s silence had not been approval. It had been architecture—shelter he tried to build while I was busy setting fireworks off in the living room. He should have told me. I should have asked. We didn’t. Now we were learning a language that does not mistake volume for truth.

We loaded the kids into our cars, a choreography we had gotten good at without applause. Rowan buckled Theo and kissed his head and handed Isa a water bottle and looked over the roof of his car at me. “See you Wednesday,” he said.

“Five fifteen,” I said. “Bullet points.”

He smiled, then got into the car and drove away without a speech.

I stood for a minute with my hand on my own car, palm pressed to the warm metal, feeling the hum of the engine and the hum of my life inside my chest. The lock at the old door had not clicked for me. He had filed papers. He had blocked me where he could. And still, there was a key in my hand now—not to a house that no longer wanted my volume, but to a door my children run through without checking the weather.

We drove home. I made spaghetti. The sound of it landing on the table was soft and excellent. The kids laughed at something that wasn’t me. When they asked for seconds, I handed them bowls quietly, and across the room, the calendar glowed like proof.

The End

News

MY DAUGHTER CAME BACK FROM HER HOUSE, HER FACE SWOLLEN AND BLOODY. I HELD HER CLOSE AND CRIED… CH2

Part I — The Night of the Lie Her body gave out the moment she crossed my threshold, the way…

My daughter shaving her sister’s head before prom was the best thing she ever did. CH2

Part I You never think the sound of clippers will be the sound that saves your child. It started as…

Husband Has Baby with Sister, Dumps Me ➡ 3 Years Later, Surprise Meeting, Ex’s Shocked Face. CH2

Part I If you’d asked me to name the moment my marriage cracked, I’d say it wasn’t big. Not the…

Sister-in-law happy at funeral because my surgeon brother left her lots of money. CH2

Part I The day we buried my brother, the sun came out like it had been paid to. It turned…

“We Left My Stupid Husband Miles AWAY From Home as a JOKE, But When He Returned It Was NOT Funny…” CH2

Part I I can tell you the exact moment I should have trusted my gut. It wasn’t the tight smile…

Sister Announced She Was Pregnant With My Husband’s Baby at My Birthday—She Didn’t Know About the Prenup CH2

Part I The florist had crammed the hotel ballroom with white roses because “thirty deserves a thousand blooms,” according to…

End of content

No more pages to load