Part I

The coffee mug that changed my life wasn’t expensive. It wasn’t even particularly pretty—not if you asked me. It was pale blue ceramic speckled with tiny rosebuds, the kind of delicate, nostalgic pattern you might find at an estate sale. It looked fragile and romantic in a way I am not. I am a morning-shift nurse who keeps her hair in a bun, who drinks black coffee from a stainless-steel tumbler because stainless steel doesn’t shatter if you look at it wrong.

But that Tuesday morning in December, I stood at my kitchen counter staring at a mug that didn’t belong to me, watching its last ribbons of steam fade into the cool kitchen air. A lipstick kiss—a pink I would never wear—glowed faintly on its rim.

I didn’t touch it. I didn’t call anyone. I did what nurses do when strangeness walks into a room and sits down like it owns the place: I observed. I catalogued. I waited for the evidence to arrange itself into a shape I could name.

Pale blue ceramic. Tiny roses. Lipstick stain, cool pink. Still warm.

The clock on the stove read 12:07 p.m. My shift at Charlotte Presbyterian had ended early because a system glitch knocked our charting offline, and sending people home saves money. I usually walk through this kitchen at three, not noon. Corbin’s black sedan—the one we pretended I liked but I always felt was overcompensation—sat in the driveway like a faithful dog. He worked from home; today that should have been a comfort.

Except there was the mug.

“Corbin?” I called, my voice too bright to be calm. “I’m home!”

Silence for a beat. Then his voice drifted up from the basement office he’d outfitted last year with two extra monitors and a planted fern he never watered. “Down here, babe! You’re early!”

Everything about the house felt charged. Not messy—my house wasn’t that kind of place—but slightly rearranged, like someone had thumbed through my life and put it back in almost the right order. I could smell something floral that wasn’t my vanilla. A hand towel in the spare bath bore the faint damp of recent use. The guest room door—no one’s room; our house is just us—sat two inches open, a position I never leave it in because, as my grandmother used to say, a door ought to decide what it is.

I took the stairs to Corbin’s office slowly, my hand sliding along the banister like I might fall. He looked up from a scatter of spreadsheets, eyes crinkling in that practiced way I once found disarming. “System crash?” he asked, standing to kiss my cheek.

“Yeah.” I scanned his face the way I scan a patient’s chart: looking for the line that doesn’t match the others. “Weird morning. Power’s out for some servers. They sent us home.”

“Lucky me,” he said, as if the universe were a waiter he had tipped handsomely. “You hungry? I was about to grab lunch.”

Whoever she was, she used pale blue mugs with roses and wore pink lipstick. She had a key, or she had company. She drank coffee in my kitchen a little before noon and touched her mouth to ceramic like a claim.

“Whose mug is that?” I heard myself ask, floating under the question like a person underwater listening for boats.

He blinked. A small pause—less than a heartbeat—punched through the practiced ease. “What mug?”

“The blue one with the flowers.”

He laughed too soon. “Babe, we’ve had that forever. Wedding registry, remember? You pick more things than you think.”

Reader, I did not. I picked white mugs—clean, simple, stackable. I picked things that fit in a dishwasher like soldiers in a row. I picked workhorse bowls and knives that cut without fuss. I did not pick pale blue roses.

“Right,” I said, the word like a pebble tossed into a deep well to hear how long it takes to hit bottom.

We made sandwiches. I asked about audits, he asked about tricky IVs. We moved around one another, performing the choreography of a marriage we’d rehearsed for eight years. But every step felt half a beat off, like someone had changed the music and forgotten to tell me.

By midafternoon, the lipstick shine had faded from the mug. I washed it with gloved hands the way I wash things that are not mine—the way I wash away blood. I put it at the back of the cabinet behind the French press we never use and the casserole dish reserved for church potlucks I don’t attend.

That evening I phoned Oakley Griffin, our neighbor, on the pretense of borrowing sugar. If you live in Charlotte’s Meyers Park long enough, the words neighbor and alibi start to feel like synonyms.

She answered on the second ring, voice bright, breathy. “Bellamy! Hi!”

I hadn’t been in the Griffins’ house since their welcome barbecue in June. Their place is the same floor plan as mine but dressed like a Pinterest board. Pastel pillows fluffed into obedient marshmallows, a glass coffee table perpetually waiting for a magazine shoot, the smell of some expensive candle in a scent named after an abstract noun: Grace, Serenity, Forgiveness.

Oakley wore a sweater the color of cotton candy and a lipstick that matched. Her hair fell in waves that made me think of the word effortless, which is a lie women tell each other as the highest form of flattery.

“Sugar,” she said, laughing. “Of course. You should have texted—I’d have brought it over.”

I watched her hands move through cabinets, slim and moisturized and ringed with the kind of delicate jewelry that scratches, not scrubs. She chatted about her husband Marcus—pilot, always gone, Frankfurt until Friday—and how quiet the house felt without him. “Sometimes I wish he worked from home,” she said, sighing. “Like Corbin. That must be… nice.”

“Nice,” I echoed, as if the word had not been replaced in my mind with strange and suspicious and who drinks from my cups when I am not here.

When I mentioned Corbin by name, something flickered across her face, a quicksilver recognition so fast I could have imagined it. But I am a nurse. I spend my days catching small things that mean big things. I do not imagine.

Back home, I set the bag of sugar on the counter and counted my heartbeats until they slowed. Corbin padded in sock-feet to the fridge and kissed my neck the way he did when he wanted me to believe the world was simple. Later, I lay in bed beside a man whose breathing I knew better than my own, and I stared at the ceiling fan until the shadows turned into a plan.

The next morning, I did something I had never done in eight years of marriage: I lied about my shift.

“Double today,” I said, pouring coffee and willing my hands not to shake. “Should be home late.”

He grimaced in sympathy so practiced it should have qualified him for continuing education credits. “That’s rough. I’ve got a big client audit anyway. We’ll both be buried.”

I left. I waited exactly ten minutes around the block and let myself back in through the gate that squeaks only if you push it with your left hip. The house felt like a stage set after the audience leaves, full of fake calm. I climbed the stairs and slipped into the master bedroom, where the front window gives me a clean view of our brick steps and the walkway that leads to the front door.

I did not have to wait long.

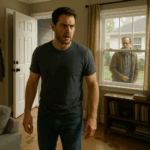

At 10:47 a.m., Oakley Griffin—pink lipstick, pastel sweater, hair kissed into waves by some device—walked casually up my steps. She did not knock. She produced a key from her purse, the kind of key cut at a hardware store and taped to the underside of a planter for emergencies.

She let herself in.

It is a small thing to write that sentence, to read it. It is another thing entirely to hear your front door open and close to a stranger’s hand. To feel your house inhale and adjust around a new presence. To realize that while you were at work putting your hands into the lives of people who might die, someone else put her hands into your home.

Cabinet doors opened. A chair moved. The guest room door—my guest room door—squeaked on the hinge I keep meaning to oil. I heard Corbin’s office door below and then his voice, friendly, intimate, the tone he uses for people he likes and wants to keep. Their voices did not rise; they slid along the quiet like old shoe leather—supple, familiar, worn in.

I wanted to blow the door off its hinges with my anger. I wanted to wrench the guest room open and throw all the pretty, breakable things I have never owned across the hall. But I am a nurse. When danger arrives, I do not panic. I anchor. I gather. I wait for the truth to show me its face.

They stayed forty-five minutes. Long enough for coffee to cool. Long enough for secrets to relax. Long enough to hear the name of a place—Colorado—and the shape of a plan—divorce—and the half-swallowed mirth of a man who has already decided he is smarter than the woman he married and any god who might be watching.

“What about the money?” Oakley asked in a tone I recognized from TV courtroom dramas—practiced innocence stretched over appetite.

“North Carolina’s equitable distribution,” Corbin said, the words smoothing out like a speech rehearsed to a bathroom mirror. “I’ll get half. She inherited a lot from her grandmother. We’ll be fine.”

We’ll be fine. As if my grandmother left me a college fund so my neighbor could buy plane tickets to Denver.

They talked logistics and lies. They arranged alibis. They plotted a story in which I was emotionally absent, a phrase men learn somewhere when they are trying to turn infidelity into a diagnosis they can bill to someone else’s heart.

When she left, I watched her cross our lawn with the easy gait of a person who believes she is entitled to what she touches. She did not look up to the window where I stood like a specter of a wife whose house no longer knows her name.

In the hour between betrayal and the moment I could move my body again, I thought of my grandmother, Rose. She was the kind of woman who read closing contracts like psalms and walked through the world like God handed her a pen. She built a real estate business in the 1960s when “Mrs.” was shorthand for “no” and men said “little lady” with their mouths and “get out” with their hands. She left me money, yes. But more than that, she left me rules.

1) Don’t assume. Confirm.

2) Keep your records cleaner than your kitchen.

3) If you are underestimated, use it. It’s the closest thing to invisibility you’ll ever get.

So I confirmed. I kept records. And I let them underestimate me.

On my way to the hospital for the shift I was not scheduled for, I stopped at Best Buy in my scrubs, my badge clipped to my pocket like a talisman. I bought a security system the sales kid said was “sick,” which is not the adjective you want to hear in a hospital or a marriage. Tiny cameras. Motion sensors. Mics as discreet as freckles. I paid in cash.

That night, I smiled and asked about audits. I served meatloaf. He told me he loved me with the same mouth that had called me a saint for spending my hours with strangers instead of him and a fool for believing him anyway. When he kissed me, I made a note of the angle, the pressure, the time it took him to lean away. I went to bed beside him and thought about which screws in the guest room vent were easiest to remove without stripping the head.

By Thursday morning, my house was wired like a heart monitor. On Tuesday and Thursday at 10:45 a.m., my house had a visitor. On Thursday at 11:02 a.m., Oakley said, “Marcus is suspicious when he’s home. He wonders where I go.”

On Thursday at 11:04 a.m., Corbin said, “Don’t worry. It won’t be much longer. Papers after the holidays. Colorado before spring.”

On Thursday at 11:09 a.m., Oakley said, “Do you really think we can get half of… everything?”

On Thursday at 11:10 a.m., Corbin laughed.

On Friday, I did what I should have done months ago: I looked into my husband’s business.

Morrison & Associates, CPA, had dissolved in September. Not because of taxes, not because of “pivoting,” not because of COVID or bad luck or the free market’s frostbite. Because Corbin’s partner, David Wei, had filed a lawsuit alleging that my “methodical, reliable” husband had siphoned more than two hundred thousand dollars from client escrow accounts and walked around our house like money printing was his side hustle.

While I was holding hands with people leaving this world, Corbin was taking from people trying to live in it. While I charted vitals, he charted theft. While I drove to work at 5:30 a.m. through winter darkness, he drove our accounts into places that don’t have extradition treaties, which is a sentence you never want to learn how to finish.

His arrogance saved me. He kept immaculate records: spreadsheets, transfers, shell companies with names so bland they could have been soy products. He bought property in Colorado under a false name, which is the kind of sentence that has no business sharing space with the word husband.

By Monday I knew what David Wei knew and more. By Tuesday I had copied everything—everything—to a cloud server Corbin couldn’t find if I gave him a compass, a treasure map, and God whispering hints. By Wednesday afternoon I had a burner email, a reservation at a diner fifteen miles from my house, and a plan that involved both the FBI and a casserole.

By Thursday morning, my plan walked into that diner with a face paler than a balance sheet after an audit. He stuck out his hand. “Mrs. Morrison?”

“Bellamy,” I said. “Order coffee. This is going to take a minute.”

He read the first sheet in the folder and swore quietly. He reached the fifth and made a sound like a man trying not to be sick. At the bank transfers, he looked up, eyes glassy with rage and relief.

“This—this is everything.”

“It’s enough,” I said. “But the rest is at a link I’ll send once I have your guarantee the innocent don’t get swept in with the guilty.”

“You’re turning in your husband.”

“I’m stopping a criminal,” I said. “The fact that he sleeps next to me means I took too long. That’s on me.”

He swallowed. “Oakley—”

“Will be at my house at 10:45,” I said. “With a key. With lipstick that leaves marks. With my husband’s alibis tumbling out of her mouth like rosary beads.”

He winced. “She was supposed to—”

“I know what she was supposed to do,” I said. “Here’s what she did.”

I pressed play on a thirty-second clip of her whispering, Once we get to Denver, and Corbin answering, We’ll be fine.

David Wei closed his eyes like prayer might have a line open. “You want me there.”

“I want you to see what I saw,” I said. “I want all the liars in one room so the truth can hear itself clearly for once.”

We parked separately on my street. He tucked himself in the shadow of my hydrangeas, which have seen worse. I went in through the back door. At 10:45, the lock turned. Oakley stepped into my foyer the way a person steps into their own skin. At 11:14, the guest room door clicked. At 11:15, I opened it.

They were fully clothed, which felt almost worse. Something about their posture—the closeness, the small conspiratorial tilt—made my stomach lurch like a roller coaster I hadn’t consented to ride.

“Coffee?” I asked brightly. “I’ve got this pale blue mug with roses I think you’d love.”

Corbin sprang up like a man jolted awake from the right dream. “What are you doing here?”

“Saving lives took less time than I thought,” I said. “Lucky me.”

David stepped into the doorway like a ghost with excellent timing. Oakley made a soft sound that wasn’t a word. Corbin looked between us, calculating routes like a man in a maze who just realized the walls move.

“This is David Wei,” I said. “You remember him, Corbin. He’s the one you stole from. And this is Oakley, David. She works for you. Or she did. It’s been… difficult to keep up.”

Oakley started crying in the way of people who have never had to cry in public. Corbin started explaining in the way of men who believe words can remodel a room faster than a sledgehammer.

I let them talk until their voices ran out of air. Then I told them, calmly, exactly how this would go. I showed them the text from Agent Sarah Martinez confirming the time. I told Corbin his parents would be at dinner at six to hear the news with the rest of us. I watched the color exit his face like it had somewhere better to be.

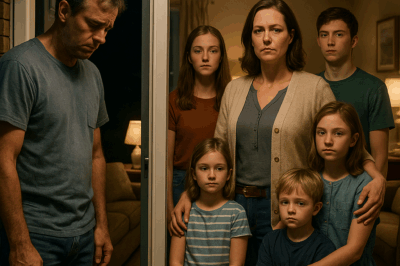

At six, Margaret and Harold walked in with an apple pie and the faces of people who have spent Sundays in pews believing they did it right for a reason. At six-fifteen, I opened the door to the FBI. Fifteen minutes later, my living room was a lesson in consequences: my husband in handcuffs apologizing to his mother for not being the man she thought she raised, his father staring at the floor like it had failed him, Agent Martinez reading charges in a voice that would not bend.

Afterward, when the pie congealed on the counter and the porch light hummed over a winter lawn, I made tea because that is what you do after a storm when the roof is still on.

I stood alone in the living room where Christmas had seemed possible three days ago. I listened to the house inhale, resettle, forgive itself a little.

The blue mug with roses sat on the counter where I had left it, mouth empty, lipstick faded. I washed it a second time. I dried it. I walked it to the trash and set it lightly on top of junk mail and a magazine I never read. I did not slam the lid.

I went to bed alone in a house that finally knew what it knew.

In the morning, I woke up and looked at myself in the mirror. My face was the same—thirty-four, a nurse, a woman who has learned how to hold other people’s pain without letting it drown her. But my eyes had changed. They were my grandmother’s eyes, the ones that read contracts and men with the same unblinking steadiness.

I made coffee in my stainless-steel tumbler. I stood in my kitchen and looked out at the pale winter sky, its color somewhere between gray and mercy. I wrote three lists:

1) Call David (recovery update).

2) Call Agent Martinez (statement).

3) Call a locksmith (every lock).

Then I wrote one more:

4) Call myself.

Because there is always a code to clear after a crisis, a number you dial to make sure the system is still yours. Because sometimes the person who rescues you is wearing your face. Because sometimes the most dramatic thing you can do is survive and tell the truth in your own voice.

And because a house is a body, too. It remembers. It heals. It chooses who holds the keys.

Part II

The night after Corbin’s arrest, I sat at my kitchen table with the hum of the refrigerator filling the silence. My house felt different—not haunted, not violated, but hollow, like a body just after surgery. Something rotten had been cut out. The wound throbbed, but healing had already begun.

The FBI agents had left me with instructions and forms, promises of follow-up interviews. Corbin’s parents had left me with tears and the sort of stunned politeness people cling to when their entire reality fractures. Margaret pressed my hands before she left, whispering, “We’ll pray for you, Bellamy.” Her eyes told me she finally saw me as more than the girl who married her son. Maybe she saw me as the woman who had destroyed him—but also the woman who had saved myself.

The next morning, I woke to a house that was mine again. No key in Oakley’s purse. No stranger’s lipstick staining my dishes. No man downstairs plotting to gut me financially. Just me and the sound of rain against the windows.

I brewed coffee in my stainless-steel tumbler, the way I always had before the pale blue mug appeared like a curse. As I sipped, I wrote a list:

Call Agent Martinez to confirm next steps.

Call David Wei to hear if restitution looked possible.

Call a locksmith.

Change passwords. All of them.

Decide what to do with Oakley.

Number five gnawed at me. Oakley wasn’t sitting in a federal holding cell. She was right next door, blinds closed tight, her husband Marcus’s car still gone on a flight rotation. She’d betrayed her employer, her marriage, her neighbor. But unlike Corbin, she still had choices left.

I wasn’t sure yet what I wanted to do about that.

Agent Sarah Martinez met me at the Charlotte field office two days later. She was small, sharp-eyed, with a presence that made me sit straighter in my chair.

“You did exactly what we needed, Mrs. Morrison,” she said, flipping through the manila folder I’d given them. “You gave us a case no defense attorney can wiggle out of. Your husband’s obsession with documentation is his downfall.”

“Ex-husband,” I corrected automatically. “The divorce papers are filed.”

A smile ghosted across her lips. “Good. That’ll keep you clear when the indictments roll. He’s looking at five to seven years, maybe more if the wire fraud sticks.”

I exhaled slowly. “What about me? My accounts were tied to his. He used my credit.”

“We know. We’ll make sure your cooperation protects you.” Her tone softened. “Bellamy, I need to be blunt: criminals like your husband count on their wives to look the other way. You didn’t. You saw him clearly, and you acted. That matters.”

Her words landed deeper than I expected. Nurses are praised for their compassion, for their endurance, for their sacrifice. Rarely for their clarity. That morning, clarity felt like my new identity.

Three days after the arrest, I rang Oakley’s doorbell. I didn’t borrow sugar this time.

She answered in sweats, her hair unbrushed, her face blotchy. She looked nothing like the polished woman who had floated into my house at 10:45 a.m. every Tuesday and Thursday. For a moment, we just stared at each other, two women separated by a single strip of grass and an ocean of betrayal.

“Bellamy…” Her voice cracked. “I—”

“Don’t.” My voice surprised me with its steel. “You don’t get to start with excuses.”

She stepped back, wordlessly inviting me in. Her house smelled of stale perfume and takeout containers. The pastel perfection was smudged, like a watercolor left in the rain.

“I know everything,” I said, standing in her kitchen where the counters gleamed too bright. “David told me. The FBI told me. You were hired to spy on Corbin. You ended up sleeping with him instead.”

Her shoulders slumped. “I thought I could handle it. At first it was just a job. Get close, get information. Marcus is gone all the time, and I was… lonely. Corbin made me feel—”

“Spare me,” I snapped. “He made you feel special. He made me feel pathetic. He made clients feel robbed. We all know the script.”

Tears spilled down her cheeks. “I never meant for you to get hurt.”

“You used a key to my house,” I said quietly. “You sat at my table, drank from my mugs, laughed in my guest room. You didn’t just hurt me. You disrespected me. That’s worse.”

Her chin trembled. “What are you going to do?”

I took a deep breath. “Nothing. The FBI will handle Corbin. David will handle restitution. Your marriage, your choices, your conscience—that’s your punishment. I’m done wasting my energy on people who underestimated me.”

Her relief was visible, but so was the shame. I walked out without another word. Some doors you close without locking. They stay closed anyway.

Two weeks later, Margaret and Harold asked me to meet them for lunch at a quiet diner on the edge of town. I almost said no. But part of me needed to see them—needed to prove to myself I wasn’t afraid of anyone carrying the Morrison name.

Margaret’s eyes were swollen from crying, but her grip on my hand was firm. “We don’t blame you,” she whispered. “We blame ourselves. We raised him to believe he could do no wrong.”

Harold cleared his throat, his banker’s voice brittle. “The FBI told us you gave them everything. That you… saved those clients. We’re grateful, Bellamy. And ashamed.”

I stirred my coffee slowly. “He fooled me, too. For eight years. But he left me one gift.”

“What’s that?” Margaret asked.

I met her eyes. “He taught me never to underestimate myself again.”

By January, David Wei called with an update. “We’ve recovered $240,000. Most clients will get back nearly everything. Your cooperation sealed it.”

“And Corbin?” I asked.

“Still in federal custody. His bail request was denied. His lawyer’s hinting at a plea deal. He’ll be gone a long time.”

I felt a strange mix of relief and sorrow. Relief that justice had worked. Sorrow that the man I once loved had chosen this path. But I didn’t dwell. Some wounds don’t need nursing. They need amputation.

The divorce finalized in February. I kept the house. I kept my inheritance. I kept my dignity. Corbin kept his spreadsheets and his prison sentence.

Life settled back into a rhythm. Early shifts, long days, the satisfaction of easing pain with practiced hands. My home became a sanctuary again. I bought new mugs—sturdy white ceramic, nothing delicate enough to shatter. I changed every lock. I painted the guest room a new color, a shade called Iron Blue. Strong, unyielding. No one’s playground but mine.

Neighbors whispered, as neighbors do. Some pitied me. Some admired me. But I didn’t care what they thought. For the first time in months, I cared only about what I thought of myself.

And I thought I was strong.

One evening, watering my grandmother’s roses in the backyard, I caught my reflection in the window. I looked tired, yes. But not broken. My eyes were clearer. Sharper. My grandmother’s eyes.

I realized then that Corbin hadn’t destroyed me. He had revealed me. The betrayal, the lies, the blue mug with roses—it had all been an X-ray, exposing the steel beneath my skin.

I whispered into the twilight, as if Grandma Rose might be listening: “I learned, just like you said I would. I learned I’m smarter than they thought. Stronger than I knew. And worth more than anyone who would dare underestimate me.”

The air felt lighter. My house hummed with peace.

And when I walked inside to brew another cup of coffee, I smiled at the row of mugs in my cabinet—every single one of them mine.

Part III — The Reckoning (≈1,600 words)

The summons to testify arrived in a plain envelope, the kind you’d mistake for junk mail if your life hadn’t already taught you that the most harmless-looking things can detonate when you open them. I sat at the kitchen table with the letter spread before me, the paper’s creases like fault lines.

“Subpoenaed to appear,” it read, with a time and a courtroom and a case number that now belonged to my marriage.

Agent Martinez called that afternoon. “You won’t be alone,” she said. “We’ll walk you through it.”

“I hold dying people’s hands for a living,” I said, surprising myself with the bite in my voice. “I can handle a courtroom.”

“I don’t doubt it,” she replied. “But it’s not your patient, Bellamy. It’s your story. Sometimes that’s harder.”

I looked at the backyard where my grandmother’s rose canes, cut back to hard stubs for winter, dreamed of June. “Maybe that’s why it matters.”

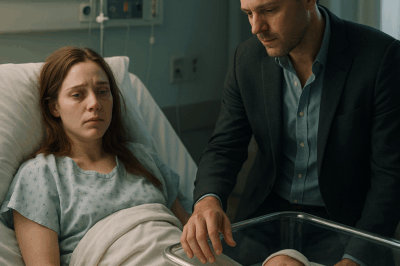

On a gray Thursday in March, I took the stand. The courtroom was beige and unsentimental: walls that had seen too much, benches that creaked in the language of old wood. Corbin sat at the defense table in a suit that didn’t fit him anymore—jail weight or conscience or the collapse of a persona will do that to a man. His hair was trimmed to obedience, his hands cuffed in a way the jacket tried to hide. He didn’t look at me.

The prosecutor, a woman with a voice like polished granite, led me through the facts. The spreadsheets. The offshore transfers. The shell companies that bought a house in Colorado the way children buy a fantasy with Monopoly money and swear it’s theirs forever.

“And the recordings?” she asked gently, setting a small speaker on the rail between us like a confession booth.

I nodded. We all listened to his voice spill through tinny plastic. Defective… this wasn’t the plan… I don’t invest in flawed assets. In the row behind the bar, I heard a woman gasp softly and a man mutter something that sounded like a prayer that had lost its words.

“And the key,” the prosecutor said finally. “How did the neighbor obtain a key to your home?”

A ripple moved through the gallery like wind through field grass. I kept my eyes on the prosecutor’s face, not on Oakley, who sat three benches back with her hair scraped into a penitent ponytail and a tissue shredded in her lap. “I don’t know,” I said. “I never gave her one.” I did not add: The thing about trust is that you give it somewhere else, and it turns out to be a skeleton key.

When the defense attorney stood, he wore sympathy like a scarf. “Mrs. Morrison,” he began, as if the name still belonged to me. “Isn’t it true that your husband often worked on client accounts late into the night?”

“It’s true he told me that.”

“And you benefitted from his hard work. The house. The lifestyle.”

“My grandmother paid for the house,” I said evenly. “I paid for the lifestyle with twelve-hour shifts and a credit score he used like a crowbar.”

He tried to make me angry. He needed me to snap, to show the jury a woman unbalanced by emotion. But I have stood in ERs at two a.m. with blood on my shoes and a mother screaming in a language grief invented on the spot. I have learned my breath can carry a person across a chasm if I keep it slow. I did not swing at his bait.

“Mrs. Morrison,” he said, a little less smooth, “do you hate your husband?”

I let the question pass through me like a sharp thing that had lost its point. “No,” I said. “I mourn the man I thought he was.”

Something in the room shifted—maybe the jury, maybe the air. The defense attorney glanced down at his notes, and when he looked up, he saw what I saw: the argument had bled out on the carpet when no one was watching.

When court recessed, I walked past Oakley without stopping. She reached for my sleeve and let it fall back in a small, graceless arc when I did not pause. In the hallway, Margaret and Harold stood like bookends without a shelf, holding a paper sack from the cafeteria and not touching the food. Margaret’s eyes, raw from weeks of tears, found mine.

“May we—?” she asked.

“Of course,” I murmured, because grief is grief no matter whose child caused it.

Harold cleared his throat, the banker and the father still fighting it out behind his eyes. “We want to thank you for… doing the right thing,” he said stiffly. “Even when it cost you.”

I nodded. “I wish there had been a different right thing.”

“So do we,” he said, and in that moment I remembered Sunday dinners and pies and the way Margaret always wrapped leftovers like you were heading into winter and might not eat again. I squeezed her hand. We all moved forward a half inch.

The plea came a week later. Corbin’s attorney, exhausted by math and recordings and the chill of the jury, led him to a podium. He kept his eyes on the wood grain when he said the words guilty and wire fraud and money laundering and I’m sorry. He did not look up. He did not look for me.

The judge, a woman whose mouth had learned to be careful with its mercy, read the sentence: seventy-eight months. Restitution. Supervised release. A set of words that added up to a long time to think about pale blue mugs and people you called defective.

When the bailiff took him by the elbow to lead him out, he turned his head a fraction, like a man checking the weather. Our eyes met for the briefest moment. Not a movie moment. No orchestral swell. Just a flick of recognition, the way you nod at someone you once sat next to on a train when you both stop at the same light.

In the parking lot, a soft spring rain began in that Carolina way—polite, then decisive. I stood with my face tipped up, letting it baptize something I didn’t have a name for. When I opened my eyes, I saw her: Oakley. She hovered at the edge of the awning, coat held above her head like a late apology.

“Bellamy,” she said, voice small.

“I don’t have anything for you,” I said, and I meant it: no forgiveness handed over like a paper cup of water at mile nineteen, no anger heavy enough to throw. She had become a woman in my peripheral vision, no longer powerful enough to occupy center frame.

“I’m leaving,” she said. “Oregon. My sister. Marcus filed. I can’t… I can’t stay here and see your house every day.”

“I hope you learn something that helps you be the person you want to be,” I said, surprising us both.

She flinched. “Do you think that’s possible? After—”

“I think it’s necessary,” I said. “Which is worse than impossible. It means you have to wake up every day and do it again.”

She nodded, rain flattening her hair until she looked younger, more truthful. “You were always kinder than me.”

“No,” I said, stepping into the rain. “Just clearer. There’s a difference.”

I walked to my car without looking back. Sometimes the kindest thing you can do for a person is to stop offering them your shadow to stand in.

The hospital felt different after the trial, though nothing had changed except me. Alert tones still pulsed, call lights still winked, the coffee in the staff lounge still tasted like it had been filtered through a mop. But the way I moved through it—the way I inhabited my body in those hallways—had shifted. I said no more often. I asked for the float nurse when a patient load tipped from hard to unsafe. I did not explain my worth to anyone who couldn’t see it.

One Friday, my charge nurse caught me in the medication room. “You ever thought about precepting?” she asked. “Or charge? You’ve got steel in you, Bell.”

“I’ve got roses,” I said, smiling. “But the thorns are useful.”

She laughed. “Let me know when you’re ready.”

On my way home that afternoon, I drove past the street where Oakley used to park her white SUV. For sale signs had sprouted like mushrooms after rain. A moving truck idled in the Griffins’ driveway. I did not slow down.

At home, I stood at my kitchen sink and washed one of my plain white mugs. I thought about the way the pale blue one had looked so gentle and turned out to be a warning. I thought about my grandmother’s rule about doors. I thought about building a life that had fewer pretty lies and more honest weight.

That night I slept with the window cracked. The air was cool, the sash squeaked, and the house breathed around me like a contented animal. I dreamed I was swimming in dark water toward a shore I could not see, and when I came up for air, the moon laid a path right to my own back steps.

In the morning, I made a decision.

I called the community college and asked about classes in forensic nursing. I called a victim services nonprofit and asked how to volunteer. I called a locksmith and asked about a keyless entry system with a code only I knew. I called Agent Martinez and told her if she ever needed a nurse to explain to a jury what trauma looks like when it has to get up and go to work the next day, she could call me.

One by one, the rings echoed and settled. One by one, people said yes.

A month later, I sat outside courtroom 2B again, not to testify, but to listen. It was the restitution hearing. Client after client took the stand: a contractor who almost lost his business, a widow who had trusted the firm with the last of her husband’s life insurance, a teacher who cried without making a sound. David Wei squeezed my shoulder when he passed. “Almost there,” he whispered, and I knew he didn’t mean the docket.

The judge ordered another tranche of funds released. She thanked me from the bench in a way that sounded less like gratitude and more like acknowledgment: You helped. We see it.

When we spilled out into the corridor, I found Margaret and Harold waiting like sentries at the end of the hall. Margaret handed me a small bag, the kind boutiques wrap something in when they want you to feel like the world is a little softer than it usually is.

“I know it’s odd,” she said, cheeks pink. “But I saw this and thought of you.”

Inside was a coffee mug. Plain. White. Heavy. No roses.

I held it in both hands. “Thank you.”

She nodded quickly. “I should have seen what you saw,” she said. “In him. I didn’t.”

I shook my head. “He wanted us not to. That’s on him.”

As I walked to my car, the new mug thumped against my thigh in the bag with a satisfying, honest weight. It would chip eventually; all good, honest things do. I looked forward to it.

I drove home down streets that had stopped startling me with memories. When I pulled into the driveway, the maple tree in the front yard—the one that had stood bored witness to arrests and casseroles—shimmered in the late sun, leaves like hands waving me in.

Inside, I set the mug in the cabinet and, without thinking, reached for the pale blue one with roses I’d thrown away months ago. My fingers touched air. I laughed out loud, the kind of messy, delighted laugh that feels like a breath arriving after you didn’t realize you were holding it.

I poured coffee. I stood at the window. I watched my yard hold itself gently. I let the quiet do what it does when you stop asking it to be anything else.

And for the first time since I had stared down at a stranger’s lipstick stain, the thought came without doubt: I am not surviving anymore. I am living.

Part IV

Spring thickened into the kind of Carolina summer that makes everything fat—tomatoes, peonies, the air. Nurses know seasons by the ailments they bring: heat exhaustion, fireworks mishaps, families who realize the school-year scaffolding kept some people upright. I moved through it with a steadiness I had earned the hard way, my mind less prone to looping on old footage and more skilled at adjusting the lens.

Small things changed first. I took my grandmother’s quilts out of storage and draped them across couches and chair backs. I bought a rug patterned with dark vines and gold fruit because it reminded me of a painting I once saw in a museum and because a nurse salary can purchase beauty if you invite it in small doses. I planted tomatoes and watched them turn suns into sauce. I learned how to replace air filters and hang a door straight and fix a running toilet with a wrench and a glare.

On a sticky July morning, I met a new neighbor—Maya—when her puppy escaped into my yard and stole one of my garden gloves like triumph. She was my age, with a laugh that landed like a stone skipped across water—light, then low.

“You’re Bellamy,” she said, breathless from the chase. “I heard you’re the one who had the… situation.”

“Hard to be mysterious when the FBI parks in your driveway,” I said dryly.

She grinned. “I was going to say ‘the one who handled it,’ but yes, that too.”

We became friends the way grown women do: in increments. Coffee on the porch after night shifts. Shared rides to the farmer’s market when our schedules kissed. Texts like lifelines on days when the world tried to drown us—hers about depositions and a custody case she’d won for a woman with three jobs, mine about a patient whose heart decided to stop politely in Bay Four then chose, equally politely, to start again because one of us asked nicely enough.

One August evening, we sat on the back steps, ankles bare, bugs singing the kind of chorus that makes you feel like you owe the night something. Maya turned her glass in her hands. “You ever think about leaving?” she asked. “Starting over somewhere with no stories attached?”

I looked at the house through the open kitchen door, the light pooling the way it does when a place stops defending itself and starts welcoming you. “I did,” I said. “But then I realized this house chose me. Or I chose it. Either way, I’m not going to let someone else’s lies decide where my life happens.”

She nodded. “That’s a better answer than I’ve ever given myself.”

“I practice,” I said, and we clinked glasses.

In September, the hospital offered me the preceptor slot. “You teach without making people feel stupid,” my charge nurse said. “It’s a trick. Use it.”

I took it. My first new nurse shadowed me like a puppy with a stethoscope, eyes wide above her mask. “How do you stay calm?” she whispered after a code blue that felt like a roller coaster designed by a sadist.

“I remember who it’s about and who it’s not,” I said. “It’s not about my fear. It’s about their breath. Then I boss my fear around like it’s a resident.”

She laughed, shaky and grateful, and scribbled it down as if it were pharmacology.

I learned I liked teaching. It’s a particular power to slide someone else’s hands into competence. The world holds steadier when more of us know what to do.

Outside work, the forensic nursing class lit up a different part of me. We talked wound patterns and documentation and how to sit with a person whose body is still an active crime scene and make sure her humanity outshouts the evidence. I bought books. I wrote notes in margins. I reminded myself you can construct a future like a building—brick by chosen brick.

In October, a letter arrived addressed in Corbin’s handwriting. I held it over the trash, then set it on the table like a live wire. I made tea that went cold. I folded laundry with more precision than it required. Then I sat down and opened it.

The paper smelled like government. The words smelled like a man who has had to speak without an audience long enough to choose them carefully.

Bellamy,

You have no reason to read this. I’m writing it anyway. Maybe it’s for me. Maybe it’s for something that used to be real between us.

Prison is not a movie. There’s less violence and more boredom. Time flips you inside out and shakes you until what falls out is either truth or a lie you can live with. I thought I built the lie well enough to be a truth. I did not.

It’s a strange thing to realize the worst thing I did was not the theft. It was teaching you to doubt yourself. I weaponized your goodness and called it naiveté. You were my alibi while I robbed other people’s futures. I see that now.

I am not asking for forgiveness. I think I’m writing to tell you I have a thing to carry that won’t ever get lighter, and I’m going to carry it. The only honest thing I can do with the life I have left is try to do less harm. If the clients end up whole because of you, that helps.

You were always strong. Everyone said kind. I knew strong and used it against you. I am sorry. For real. For what that’s worth from here.

—Corbin

I read it twice. I didn’t cry. I didn’t laugh. I didn’t mail anything back. Some letters are prayers the writer has to say alone.

I slid it into a folder with court documents and emails and then, on a whim, moved that folder to the very back of the file cabinet behind tax returns and instruction manuals. The past didn’t need a seat at the front anymore. It could stand at the back like everyone else.

November arrived on cat feet, then settled its weight. The maple browned and let go, first a few leaves, then a confetti that made the yard look like the house was throwing itself a party. I raked with the grudging joy of chores that have an end. When my shoulders ached, I sat on the porch steps with a mug and watched the neighborhood tilt toward holiday.

Maya came by with a box of tree lights. “We need to do something reckless,” she said, grinning. “Like decorate early.”

“I own a staple gun,” I said. “I can accommodate chaos.”

We wrapped the porch in light. We hung a wreath so big it leaned like a discus. We draped the maple with strings until it looked like it had climbed into a necklace. My house shone—not like a challenge, not like a spotlight, but like a warm hand offered in a dark room. People walking dogs slowed. Someone clapped. We bowed.

After she left, I went inside and opened the closet where my grandmother’s ornaments live. I took down a box labeled ROSE—GLASS and lifted the tissue paper. Inside were fragile things from another century: birds with spun-glass tails, spheres with silver worn thin, bells with tongues that went silent when Grandpa died but still looked like noise.

I hung one bird in the kitchen window. It caught the late sun and threw it around the room like mercy. I hung a bell in the entry and bumped it with my shoulder so it clinked sooty and soft every time I walked past.

For dinner, I made soup the way my grandmother taught me—onions slow, garlic quick, starch last. I ate at the table and didn’t imagine another place setting.

When I washed dishes, I reached for the white mug Margaret had given me months back. It had a tiny chip on the rim now—so small only my lip knew it. I decided not to replace it. It fit me.

December rolled in with its sleigh bells and sharp edges. At the hospital, we set up the staff tree and hung ornaments that sounded like triage: “Code Brown Survivor,” “This Is My Resting Nurse Face,” “I Like My Coffee Black and My Charts Legible.” Someone stuck an angel on top wearing gloves.

On the nineteenth—exactly one year to the day since I’d set the trap for their routine—David Wei called to ask if I’d attend a small gathering at a client’s office. “Nothing formal,” he said. “Just a thank you. They want to say it to the person who made it possible.”

I hesitated. Gratitude can be a weight if you let it. But it can also be a kind of exhale you lend other people who forgot how to breathe. I told him yes.

The office was downtown, high enough to make the city look like something handled gently. Fifteen people, give or take. A pastor with a bright tie. A woman with a laugh like a tambourine. A carpenter whose hands were cracked as if the world had tried to climb in through the skin and he had fought it. We ate cookies on napkins and drank bad coffee that tasted better than anything I had swallowed in months.

One by one, they came over and said versions of the same thing: “You didn’t have to.” “I thought all was lost.” “My mother keeps her house because of you.” “They told me not to hope.” Some hugged me. Some shook my hand like a contract. One old man just touched my sleeve like he was checking if I was really there.

Coming down in the elevator, David stood beside me in the way of men who have learned to take up exactly as much space as they are entitled to and no more. “I keep thinking how weird it is,” he said. “I hired someone to get close to Corbin. She broke everything. You didn’t hire anyone. You just paid attention. And you fixed it.”

“I broke it by not paying attention for a while,” I said. “This is me learning to keep my eyes open.”

He nodded. “We all learned something we didn’t want to.”

Outside, the air bit in that clean way winter has when it’s beginning and still believes in itself. I walked to my car past store windows draped in holly and the kind of hope that sells. I passed the housewares shop and stopped because, in the window, a row of pale blue mugs with rosebuds sat like a dare.

I went inside.

Up close, they were smaller than I remembered. Lighter. Not fine bone china—just cheap ceramic trying too hard to look sweet. I picked one up, turned it in my hands, felt its imbalance.

The clerk hurried over. “A set? They’re on sale.”

“No,” I said, setting it down. “I just needed to check the weight.”

I stepped back into the cold and felt something in my chest loosen that I had not known was still tight. The past is a room; you can visit if you want. You don’t have to eat there.

On Christmas Eve, I worked the morning shift and came home buzzing with that tired you get from being useful in a world that needs too much. I changed into pajamas and a sweater, lit the candles in the windows, and curled on the couch with a book I had promised myself I would finish this time.

A knock at the door startled me. Maya stood on the porch with a foil-covered dish and a grin. “Mac and cheese,” she announced. “My aunt’s recipe. If you say thank you, I will deny I heard it and tell everyone you’re rude and ungrateful. That way the balance of the universe holds.”

“Get in here,” I laughed, and she did.

We ate on the couch with our feet tucked under us like teenagers at a sleepover. We talked about everything and nothing: the new attending who treated nurses like interns until he realized we kept him alive, the stray cat making the rounds like a landlord, a rumor about a bakery opening in the vacant space two blocks over. Somewhere in there, the conversation turned to things with edges: the cases that stick, the people who get away, the random diagram of luck.

“You ever think you’ll let someone in again?” she asked carefully, not looking at me to give me a path to say no.

“I let you in,” I said lightly.

She bumped her shoulder against mine. “You know what I mean.”

I looked around at my house, at the quilts, at the lights winking like mischief. “Maybe,” I said. “But if I do, he’ll learn my locks are not metaphorical.”

She laughed. “Put that on a mug.”

We watched a terrible movie that took itself too seriously and cried at the silliest part and then held our own hands across the couch like the world had not managed to burn down everything.

After she left, I stood on the porch and breathed the cold like medicine. Somewhere down the block, a set of wind chimes lifted and fell, striking notes that sounded like advice said in a language you half understand.

I went inside and tipped the bird ornament so the kitchen filled with small fire. I washed the dish she’d brought, not because it needed it but because it felt like a blessing to make things clean. I set it on the counter with a note: Come get me. I’m ready.

Upstairs, in bed, the house lay itself down around me like a dog circling twice, satisfied. I thought, briefly, of the girl I had been—a nurse who thought she could build safety by making her home a place where nothing strange happened. I blessed her for trying. I thanked her for stepping aside when the woman I am now needed to take the wheel.

Before I fell asleep, I reached for my phone and typed a text to myself, which is a habit I have adopted in lieu of prayers:

You did not let them turn you into what they needed you to be in order to break you. You turned into what you needed to be in order to live.

I hit send. It dinged in the dark and made me smile.

In the morning, I woke without dread. I padded downstairs in wool socks. I chose a mug from the cabinet—not because it was sturdy or because Margaret had given it to me, but because it felt right in my hand—and I filled it. I stood at the window and sipped and watched a backyard that had learned, along with me, how to winter without dying.

The doorbell rang. I didn’t startle. I walked to it at my own pace, looked through the peephole the way I always do now, and opened it because the person on the other side had earned it.

The world was still itself: messy, generous, insufficient, surprising. My house was still mine. My life was still a thing that required tending, like a patient, like a garden, like a heart.

And as I stepped aside to let in whatever came next, I understood the ending I had made:

It wasn’t that I had caught my neighbor and my husband. It wasn’t that I had outmaneuvered a thief. It wasn’t even that I had kept my inheritance and my house.

It was that I had learned the difference between being kept and keeping myself.

That is the kind of ending that keeps opening.

The End.

News

“You Won’t Last a Month with Me” — Said the Mafia Man Coldly… but the Honeymoon Broke His Rules… CH2

Part I The silence was sacred, almost cruel in its weight, as if every breath I took dared disturb something…

Millionaire Kicks Wife Out House To Be With Pregnant Mistress. Months Later, He’s Left Speechless… CH2

Part I The chandelier over the dining table looked like it had been engineered by a committee of angels and…

She Was Left To Di/e In Childbirth, But His Business Partner Secretly Became The Father… CH2

Part I The view from the fortieth floor was Sterling Thorne’s favorite trick. He’d throw open the terrace doors with…

PART II: He Threw His Wife and 5 Children Out of the House… BUT WHEN HE CAME BACK HUMILIATED, EVERYTHING HAD CHANGED! CH2

The discovery of Octavio’s remains hit Guadalajara like a storm. It was not just news; it was a revelation that…

“I Cheated for 4 Years Long Ago—Now He Refuses to Believe I Ever Loved Him”…CH2

Part I Look, I know how it sounds. I can hear the chorus already—homewrecker, liar, fraud—like a crowd warming up…

My Parents Texted “We Need Space From You, Please Don’t Reach Out Anymore At All” My Aunt Packed… CH2

Part I My name is Eliza Hart. I’m twenty-seven years old, and if you think abandonment kills the soul, wait…

End of content

No more pages to load