Part I:

I found it by accident, which is probably how most catastrophes begin. The hotel receipt was jammed down in the passenger-side door pocket of my wife’s white Porsche Cayenne, folded twice and smelling faintly of her perfume—the expensive kind she said she bought in Paris but I later learned came from a boutique in St. Louis. The receipt was itemized in neat columns, a stack of charges from the Hyatt downtown. Room 207. “Valerie Thornton & Reed Walters.” Check-in: 2:03 p.m. Check-out: noon the next day. A king room with a view of the river, two cocktails charged to the room bar, a late-night sandwich—turkey club, no mayo—and a “romance package,” which the clerk who printed this little piece of dynamite had courteously abbreviated as “RP.”

I didn’t rage. I didn’t shout. The garage smelled like warm oil and pine sawdust, and the late afternoon light reached in through the roll-up door like a friendly hand, so I was already home in the way that matters. I reached for my phone, snapped a picture of the receipt as it lay exactly where I found it, and let the shutter sound mark the first tick of a new clock in my life. Then I slid the receipt back into the pocket, eased the door shut the way a surgeon closes skin, and looked at my hands. They didn’t shake.

People call me Old Dog. Not because I’m mean—because I don’t learn the wrong lessons twice. Fifteen years of sweating over classic engines in a shop I built with my own knuckles taught me that patience is not a style; it’s a tool. If you lean too hard on rusted bolts, the head snaps and you’re doomed to drill. If you breathe through the first impossible turn, the threads surrender. That day, the marriage bolt had slipped. I intended not to snap it but to walk it all the way out.

I drove the Cayenne home and parked it where it always slept, nose facing the neat little shelf where I keep tire chalk, valve caps, lug nuts, and prayers. Valerie’s treadmill shoes—clean, lemon-white things that never touched a sidewalk—sat by the interior door. Her side of the garage was immaculate, as if cleanliness could launder conscience. I stood there for a long minute, hearing the quiet tick of cooling metal, and then I poured a cup of black coffee from the pot I keep on a hot plate near the bench grinder. I wrote a note on a torn piece of invoice: “I’m gone. Good luck to you and your lover.” I dated it because I’ve learned in small claims that time is as useful as torque.

At five in the morning I walked back into that garage with a torque wrench I’d once used to persuade a seized axle nut off a ’58 Corvette. I liked the heft of it, the promise. I didn’t swing it. I knelt down beside the Cayenne and unscrewed the valve caps from all four tires. A man who makes a living taking things apart knows how to start a symphony with a piccolo. The hiss that filled the garage was so clean it could’ve been a whistle: sharp, even, satisfying. I sat on a low stool, sipped my coffee, and watched the tires settle, the premium rubber squatting slowly like a herd of expensive animals kneeling for the night. Small favors to ritual: the hiss, the coffee, the smirk I’m not proud of but won’t deny.

When the last tire sighed itself flat, I stood and tucked the note into a magnet clip on the freezer. Then I took my phone and shot a second photo: four flattening tires and the smirk of a man who has decided to stop being surprised by the world.

It’s funny what people say they admire about you right up until they don’t. Clients—judges who can’t change a wiper blade, surgeons who can recite the inner constellations of the human body but call a carburetor a “carb”—love that I’m precise, that I keep my receipts, that I paint the floor a fresh battleship gray every spring. Valerie had once loved those same things, or at least tolerated them as if they were a phase I might grow out of after forty. Then she found “fitness.” Then she found “wellness.” Then she found Reed.

I didn’t sleep that night. I looked over our last six months of bank statements instead and found a geography of lies: a new credit card I didn’t know about, charges that had no scent of groceries or gas, hotel bars whose names sounded like excuses. Somewhere in my chest a little metronome clicked into a new rhythm. I went to the Cayenne’s glove box, pulled the dash-cam backup card I’d installed for “insurance,” and put it in the shop computer. I watched my wife’s car drive to places it didn’t tell me it was going. On fast-forward the streets spooled by like ribbon. Tuesday: the Hyatt garage. Sound got crisp at a light near the river. Her voice, unbuttoned. “Reed, baby, Ellis is clueless. A few more weeks and the house is ours. The garage? We sell it off. He always signs whatever I put in front of him.” And Reed, with that flat baritone of a man who thinks he’s been chosen by luck: “He’ll sign. Then we launch the center. I’ve got a place in mind. We just need the funds.”

Stop. Back up. Play again. I wrote the time down, the date, the intersection. I made neat notes because that’s the way I know how to breathe. I turned the volume up and let contempt do what contempt does: sharpen my calm until it cut.

At nine, I met Steve—retired cop, now wearing the suit of a bank security manager—at the bank. “Are you sure?” he asked, all Kansas eyebrows and warm coffee breath. “Sure,” I said. The branch manager, Richard, had a tie knot the size of a lemon. He looked at the pictures and listened to the bit of dash-cam audio I brought. He looked at Steve, who nodded with that cop nod I’ve never gotten tired of seeing. I explained section 478 of the bank’s policy—that narrow hallway of authority designed for the moment when a family turns predatory.

Richard sighed and tapped keys. “We can put a temporary hold on your joint account pending review. Card authorizations suspended. It’ll take forty-eight hours fully to propagate.”

“That’s enough,” I said. “Also, the company cards.” My hand found the clause in the agreement like memory finds a familiar song: as owner I could revoke any employee or spouse authorization at will. I wasn’t emotional. I was inventorying the shelf.

When I left the bank I didn’t go home. I went two blocks south to Old Dog Garage. Russell—six-four with a USMC tattoo that peeks from his shirtsleeve like a warning—was already there, turning a rotisserie rig he’d welded for a ’68 GT500. “Boss?” he said, reading my face like a service light. “We doing this?”

“We are.” I handed him a page: proof the Porsche was titled to the LLC because our accountant had once said there were advantages to that sort of thing. “Asset recovery. Safety inspection. Tow it to Bay Three.”

Russ grinned. He loves two things: breakfast burritos and lawful paperwork. “Roger that.”

That afternoon, while the Cayenne was hauled to my shop and parked neatly within a yellow rectangle that says “NO TOUCH UNTIL SANE,” I had coffee with Frederick, my lawyer. He raised his eyebrows at the draft agreement I slid across the table. “Ellis,” he said carefully, like a doctor telling a patient that there’s a chance to save the leg if we amputate the foot. “You’re offering her the house and half the liquid savings.”

“For now,” I said. “There’s wiggle language in Section 17. Liabilities transfer with title, including any encumbrances recorded prior to transfer. I want a thirty-day deadline for executing the transfer. She’ll rush. She’s a rusher. Rushing’s a tell.”

Frederick looked at me for a long time. He has the hands of a pianist and the mind of a plumber. He nodded. “You’re setting a trap. Mind you: if she slows down, if she gets counsel—”

“She won’t,” I said. “She thinks I’m a pushover.” It’s a nice advantage, being underestimated. It’s like finding out the wrong plug was removed from the engine and everyone else is pouring oil in the crankcase breather.

By noon, Russell texted a photo of the Cayenne sitting in Bay Three with four elegant flats and a recovery notice tucked under the wiper. I could almost hear Valerie’s scream when she found the garage empty. I imagined the neighbors peeking through blinds—this street is a prairie dog town, all heads popping up at any unusual movement—and I took no joy in it, or so I told myself.

At two, I gathered the crew. Mechanics smell trouble the way hunters smell rain. There were jokes, a little nervous laughter, and then Russell got a new assignment: become the kind of idiot who wins the lottery and wants to make a splash in “wellness.” We gave him an ugly blazer from a Vegas car show, a borrowed gold watch from a client who likes to play, and a business card with an engraved bull on it. He would call Reed. He would dangle capital like jerky over a kennel. He would keep a straight face.

“Is that legal?” Tom asked.

“Lying about your luck?” I said. “That’s the American pastime.” Russell was to ask about investment returns and partnership and the “center.” He was to say the number “two million” like he’d practiced the phrase in the mirror. He was to ask if Reed’s “girlfriend” would be involved, then fumble a few bills for a protein shake and grin like a dog.

By the time the evening came, the plan had momentum. Valve cores, bank holds, a draft that looked like a surrender from a man who hated court more than he feared poverty. I slept on the shop’s old cot. There’s a comforting hum in the garage at night—the afterheat of metal, the ticking of cooling pipes, the clink of a wrench settling an inch deeper into its tray—and it kept my head clear. The cot creaked when I rolled over, and I thought, not for the first time, that no machine runs forever. The best you can do is know when to stop, rebuild, and torque to spec.

When the sun rolled up the edge of the day, I called the utilities. “Owner traveling for a month,” I said. “Suspend service in forty-eight hours.” I pulled the hard drive on the home security system and tucked it in a safe. Then I sat in my shop chair and waited for the morning to bring whatever it was going to bring next. I didn’t know everything, but I knew enough: the only way out is through, and I own good boots.

Part II:

By nine the next morning, Frederick had dotted his i’s. He doesn’t cross t’s so much as he snaps them down like studs. The draft agreement read like a gift basket. “The marital home to Valerie Thornton; fifty percent of liquid cash assets from joint accounts in equal measure; personal property enumerated as attached.” It sounded like surrender to anyone who didn’t know what mattered. The sentence that did matter was mid-paragraph in Section 17, in twelve-point font rather than the usual eight of fine print: “Transferee agrees to assume all liabilities, encumbrances, liens, and obligations of said property arising prior to transfer and persisting thereafter.” If you read it fast, you’d think: taxes, utilities, maybe a roof warranty. If you read it like a mechanic reads a parts list, you’d think: the chassis tells the truth.

When a heart knows it’s being hunted, it runs. Valerie ran straight into the paper. She signed in a coffee shop on the east side at a two-top where people take meetings they want to look important. She posted a photo to her private square of the internet where her friends comment in vowels. “New beginnings.” “Finally!” “So proud of you.” And my favorite, from a woman named Piper who uses quotation marks around anything that embarrasses her: “You deserve ‘happiness.’” Reed smiled in the picture, his teeth a little too white for our ZIP code. I imagined his mind turning over numbers like a slot machine trying to hit cherries.

That afternoon, I went to see Steve again—old friend, old cop, now the sobriety of a bank’s back office. We watched the joint account freeze propagate across systems like winter. We canceled the company cards with Valerie’s name on them. Richard the manager didn’t like me much by then, but he liked policies, and policies are the weather of institutions. You may not like the cold, but you respect the frost.

Back at the garage, Russ walked me through his performance plan like a sergeant reciting pre-op. He would stroll into Reed’s gym with his belly slightly out, talk too loudly about scratch-offs and “the Lord’s favor,” and ask if Reed had ever thought about franchising. “I’m thinking ‘The Walters Way,’” Russ said, keeping his face as serious as a judge. “Weighted blankets. Oxygen bars. Grown-man trampoline classes.”

“Don’t overdo it,” I said.

“Overdo what?” he said, grinning.

He went that evening. I waited with the patience that isn’t patience anymore but habit. At eight, the texts came fast.

RUSS: He bit. Full shark mode.

RUSS: Says he has a location. Wants 2 mil for 30% ROI.

RUSS: I told him I’d be in for 2 if I can “drink shakes for free.”

RUSS: He almost cried.

ME: Good. Tomorrow ask about his “partner.” Gauge coordination.

RUSS: Copy.

If there’s anything funnier than a liar celebrating, I don’t want to know. Because nothing about any of this was funny in the way I might have wished. It was the heavy humor of gravity: you show someone a cliff; they tell themselves it’s a shadow; they step out; they fall. You don’t laugh. You record the time of impact.

The next morning, while Reed imagined the brass letters of a wellness empire inevitably affixed to strip-mall stucco, I did the opposite of imagining. I gathered proof. I printed bank statements. I downloaded the dash-cam footage. I wrote transcripts. I pulled the titled ownership record from the company file and made three copies. I took pictures of the Cayenne’s flat tires, their elegant slump like the knees of a queen. I stored everything in a manila folder that had once been labeled “Bel Air—exhaust” and now said in Sharpie: “V.”

By noon, Russell texted that Reed had promised to show him the “perfect space” after lunch the following day. I walked three blocks, picked up a BLT from a diner that knows my name, and ate it at my desk with a precision I learned in my twenties: each bite the same size, the last bit of bacon saved for last. When the phone rang it was Frederick. “Underwriting approved,” he said, using the smooth voice he uses when he’s telling me there’s a new hole in the hull and he found a plug. “Second mortgage at sixty percent LTV. Funds deposited on execution. Lien will record immediately. You’re still owner of record until transfer occurs.”

“Good,” I said. “Let’s execute.”

“Ellis,” he said then. “I need to say this out loud. This is—within the letter—legal. But your marriage isn’t just a machine.”

“You’re right,” I said. “It’s not. If it were, I would’ve rebuilt it sooner.”

We signed the second mortgage that afternoon on the blank line where you sign your life away. The money hit my personal account before dinner. The lien recorded digitally with the efficiency that banks reserve for the parts of life that cost the most. I looked at the numbers, then I looked at my lift, the one I’d wanted to replace for five years, and thought: don’t you dare.

Valerie, in the meantime, tried to buy groceries and learned that the universe had not accepted her card. She tried to fill gas and the pump hiccuped a denial that must have sounded to her like betrayal has a beep. She called me, and I didn’t pick up. She texted two questions, then nine questions, then a paragraph. She accused. She invoked names. She reminded me of vows. Then she wrote, “You always do this, you child. You make everything difficult.” I set the phone face down on the desk and spun a 7/16ths wrench three times on its belly.

The following morning, Russell arrived at the gym in his hot blazer and borrowed watch. Reed took him to a “location”—a closed tanning salon two miles from the highway, where a sagging awning still advertised “Mystic Spray!” and the windows reflected the kind of sadness that only commercial real estate can hold. “This is it,” Reed said, pushing his hands out as if showing off a miracle lot in Malibu. “Plenty of natural light. We’ll do a juice bar there. Meditation rooms down that hall. Cold plunge in the back.”

Russ is good at many things; pretending he sees beauty in the ordinary when he actually sees opportunity for mischief is his best. “Brother,” he said, “I can taste the ROI in the air.”

They scheduled a follow-up with “Russell’s advisor,” an appointment that would never occur. Reed floated all day.

That afternoon Frederick met with Valerie and Reed to present the draft. He told me later how they practically hummed with relief. “We did it,” Valerie said to Reed, her eyes slick with the relief of a person who thinks the last five steps don’t have consequences. Reed scanned the pages with the half-attention of a man who likes to count money but not words. “Debt language?” he asked.

“It’s boilerplate,” Valerie said and signed out of habit. She left the coffee shop with a fresh swing in her stride, like a girl who’s just discovered she can be cruel and be praised for it. She went straight to the locksmith.

I know because by dusk, the locks on my house clicked shut against me. She texted a photo of a key on her palm with a caption that read, “This is how new chapters look.” I looked at the photo for a minute. On the far edge of the frame, the corner of our wedding photo—a candid from the reception where I’m laughing and she’s in love with the idea of a person like me—peeked out from a stack where she’d laid it like an accident. I zoomed in until the pixels turned to blocks, and I realized I was tracing a ghost with my thumb.

By the end of the week, things began to wobble. The mortgage payment notice arrived—first installment due on the second mortgage, $12,000 up front, $4,500 monthly thereafter. Frederick said Valerie called him like a hornet. He told her to re-read the document. He told her about Section 17. He told her, kindly because he’s a good human being, that perhaps in time she’d come to admire the craftsmanship of the trap, if not its architect. She hung up on him.

Reed, faced with numbers, trotted out Russ as a savior. “He’s coming,” Reed said. “We’re closing any day now.” He texted Russ. Russ let the texts sit like deer in the road at dusk. Reed called. Russ let the call disturb the silence of lunch without answering. Reed went back to the gym and told a woman to squat lower, and his voice cracked.

In the middle of all that wobbling, I did something—depending on your ethics—that was either legal or legal by accident. I “forgot” to remove the cameras I’d put up in the house the year Valerie convinced the HOA to approve cameras for “neighborhood safety.” They were not the kind of cameras you notice; they were the size of a grape, and efficient. I watched a marriage fail on my shop monitor between reruns of NASCAR, and I felt the kind of tired that sinks into your wrists.

Meanwhile, the Cayenne sat in Bay Three waiting for its manufacturer-recommended annual inspection. “Company asset,” we told anyone who asked, which was no one. It’s odd how quickly neighbors learn to keep their eyes from the very thing they want to stare at. Those same neighbors started using my garage again in a flood. “Ellis, that lawnmower,” “Ellis, the snowblower,” “Ellis, could you look at my door hinge?” They came for bolts and stayed for gossip, and when they mentioned Valerie’s HOA fines or her Instagram lectures about “community health,” they didn’t even pretend to be sorry.

The HOA president changed that month. The new one—a retired accountant who has a love affair with the word “audit”—wrote a letter that rode the week like hot wind. “Discrepancies in landscaping expenditures.” “Receipts requested.” “Bylaw 23 invoked.” “Seven days to respond.” Valerie could not produce the receipts, because no amount of diligence can print a receipt from nothing. That money had a smell and a name brand, and neither of those words was “mulch.”

Clients began to ask for refunds from Reed. Anonymous posts about the “supplements” he sold circulated in a forum where serious lifters do not forgive fools. A lab report surfaced that used phrases like “starch” and “non-therapeutic laxative.” He called the poster a troll and then, when four more posters showed up, he called them “haters.” I watched a man struggle to learn that the word “haters” is not a shield against evidence.

By now the shape of the thing had emerged. Step one had hissed. Step two had frozen. Step three had signed and locked and smiled for cameras. Step four raised its head like a serpent. You can call any plan a “machine” if you want to, and a lot of men who live in garages do exactly that, because we understand machines. But the parts in this one weren’t metal. They were vanity and contempt and the kind of greed that believes it is owed. Machines break down. People collapse.

I thought once that week about driving out to the river and throwing my phone in. Instead I polished the chrome on a ’69 Mustang Mach 1. I did it with a silk scarf that had cost more than the down payment on my first apartment—the Hermes Valerie used to drape over the back of a bar chair for strangers to admire. I let the silk make lazy circles on the hood until the paint looked like midnight. The scarf left a faint perfume behind. I hung it on a pegboard hook when I was done and labeled the hook: “Polishing cloth.”

Part III:

I used to think time goes by and takes things with it. What I learned during those weeks is that time doesn’t steal by itself. It’s the little hands in people—their appetites, their impatience—that reach forward and snatch what isn’t theirs yet. Forty-eight hours after the banks did what banks do, Valerie’s world turned from tap to drip. Cards failed. Auto-payments bounced. The approachable calm of a financial dashboard turned storm-warning red. She moved money inside our accounts like someone rearranging furniture in a room with a faulty foundation; the floor still groaned.

The Cayenne came back to her in the worst way: by rumor, by sighting, by shaken fists in a group chat. Russell left the company asset recovery notice under a windshield wiper like a love letter from bureaucracy. “Annual safety inspection.” It could have been a joke except it wasn’t. When she called the garage, I didn’t pick up. When she called the company line, Russell answered with professional warmth, told her he was so sorry for the inconvenience, and that the vehicle would be released after the scheduled inspection—standard policy for assets registered to Old Dog Garage LLC. And it was. Seven days later, after the inspection was complete and a very real checklist with very real items had very real checkmarks, the vehicle rolled out of Bay Three on newly balanced tires I had not paid for. Sometimes the right thing and the petty thing snuggle close enough together at midnight that a man can fall asleep thinking he did only one of them.

Reed’s first real panic came the morning his landlord called. His gym sat in a cheap strip near a liquor store and a payday loan office. The landlord was a nice man who liked the word “grace.” He had been full of grace for months while Reed floated an image of growth to anyone who glanced. “The rent,” he said that morning, less grace in his voice than was usual. “I need the rent.”

“It’s coming,” Reed said. “We’re closing an investment this week.” He said it while looking down at his phone where Russell’s unreturned texts glowed like dead fish on a dock.

“Good,” the landlord said. “Because there’s a guy who wants the space for a vape store.”

Reed hung up and did ten pull-ups. He called them “reset reps.” When you’re drowning, your flailing still looks like swimming for a minute.

The HOA letter to Valerie became an HOA inquiry at the precinct. Misappropriation is a word that looks professional until the police put it in a sentence that smells like bleach. A detective with calves like basketballs called her to schedule an interview. She called Reed. He told her it was a nuisance tactic and that she should “own her truth.” She asked him which truth. He told her she was “manifesting abundance.” She hung up and cried.

Somewhere around day ten, I cut the video I’d been assembling. Call it an impulse. Call it calculation. Call it the exhausted move of a man who has been careful too long and wants, finally, to pour himself a measure of spectacle. The community BBQ festival was coming up—the annual ritual that keeps neighbors remembering they are neighbors. Valerie had planned to give a small farewell speech as outgoing HOA chair. The new chair had politely kept her name on the program because Midwestern courtesy has a long half-life. I called the festival coordinator and asked for a booth near the main stage. “We could run vintage car restorations on a loop,” I said. “People love watching rust turn to glory.” She said, “That sounds wholesome.” I said, “Yes, ma’am.”

I edited for three nights in the shop office, the hum of the soda machine keeping rhythm. I put together a ten-minute piece that began with a montage of engines we’d resurrected—rods that stop knocking, paint that catches the light like honey. Then the tone shifted: dash-cam audio, bank records, Charity-ball photos where Reed’s hand rests just a little too familiarly on Valerie’s back. I wove in the HOA audit letter with its tidy demands. Then I broke tone entirely and dropped in something like a circus, because I couldn’t help myself: a fast, animated flow chart showing how a scheme moves from idea to “RP” to a second mortgage to a foreclosure notice, set to a bright, brassy march. If art can be a wrench, satire is the one that hurts your knuckles when you slip.

The day of the festival came clean and blue. Children ran with hot dogs; teenagers faked boredom; dads stood in groups arguing about smoker temperatures as if a brisket’s tenderness were a referendum on masculinity. I set up my booth, rolled down the white screen, tested the projector, and shook hands. I wore my shop shirt with the OLD DOG patch. I didn’t plan to do what I did. Or maybe I had planned it so completely that I can now afford to lie to myself.

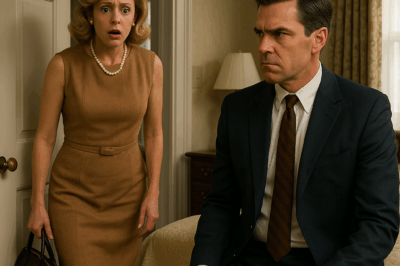

“Friends,” the emcee boomed after the pie-eating contest. “Please welcome our outgoing HOA chair, Valerie Thornton, and her partner, wellness consultant Mr. Reed Walters, to say a few words about the year behind us and exciting projects ahead.”

They walked up to the stage like a couple who met on the set of a commercial. Valerie’s hair was done in what her stylist calls “effortless waves.” Reed wore a sport coat so tight it thought it was a personality. She cleared her throat, lifted the cordless microphone, and I pressed PLAY.

The first second was a restored Nova in a blaze of orange. The next second was a windshield reflection of Room 207. Then the dash-cam audio spilled out into the park as if even the breeze had ears. “Ellis is so clueless,” Valerie’s voice said, not the clipped sweetness she uses at HOA meetings, but the loose, stringy voice she uses when she thinks the car is empty of witnesses. “We sell the garage. We take the house.” Reed, smiling, said, “He’ll sign.”

It took six seconds for the crowd to understand what it was hearing. Then the sound changed. It became that murmur you hear in church when the pastor says something the congregation will be gossiping about by supper. People turned toward the main stage and toward my screen at the same time, like flowers deciding between sun and storm. I let the evidence play without commentary. Photos. Transcripts. A line that said “Second Mortgage Recorded: County Register, 2:52 p.m., June 17.” The tacit timeline: cause, conduct, consequence.

I closed with a message I recorded in the shop at midnight. I wore my cleanest shirt and told the truth. “Neighbors,” I said, “I’m Ellis. You know me as the man who fixes things when they break. I love this place. I love this work. I love, very much, living among folks who take care of one another. Sometimes, though, people who are supposed to care for us take from us instead. Some of you paid fines you shouldn’t have paid. Some of you bought ‘supplements’ that shouldn’t have been sold. Some of you loaned kindness to people who put it in their pocket and didn’t send it back. I’m not here to punish. I’m here to say: we can do better. And if you ever need a carb rebuilt or a kindness returned, Old Dog’s got a 20% discount this month for anyone who brings a BBQ sauce stain.”

I faded out on a before-and-after shot of a rusted Camaro that now looks like a sin. Then I turned off the projector.

Reed stood at the microphone with an expression like someone had replaced his brain with a carburetor halfway through a sentence. Valerie’s face had gone gray around the lips the way a face goes when it meets gravity head-on. The emcee tried to pretend nothing had happened, which is a type of heroism I didn’t know how to recognize until that minute. But pretending is not a win condition. The crowd booed. They jeered. A woman yelled, “Where’d my $300 go, Reed?” Someone else shouted, “Mulch?!” The teenagers who had faked boredom were suddenly alive with it. Phones came out like open mouths.

Reed looked for an exit in every direction but the right one. Valerie tried for the microphone; it was dead because the emcee, in a move that must earn him a statue someday, had flicked the switch. They left the stage with the posture of actors whose play has been canceled at intermission due to the sudden unavailability of dignity.

That night every neighborhood feed lit like a siren. The local paper ran a short about “Alleged Impropriety in the HOA.” A TV station sent a reporter with eyes like high beams to stand in front of our park sign and say, “Neighbors here say they feel betrayed.” They called me “a well-known mechanic” and got the shop name wrong—Old Dog’s, possessive, which still makes me smile.

Three days later, the foreclosure letter arrived at the house. I know because I saw it through the camera. The envelope had a red stripe. Valerie opened it with a fingernail and read the word “Notice.” She sat down on the stairs. She called Reed. He didn’t answer. She left a message that began as a reprimand and ended as a plea. By then, the second mortgage payment was late. By then, the credit rating had already begun to wobble. By then, the “wellness center” existed only as an invoice from a sign company for a deposit Reed had paid with money that had a better job to do.

Reed’s customers compiled their own little class action of rage. The Consumer Protection Agency filed a notice of investigation. Five of his clients showed up to the precinct where Valerie had been called and asked to file. The officer at the counter did the professional version of a raised eyebrow. “We can take your statements,” she said. “You’ll need to keep your receipts.” They did. They had the kind of receipts that don’t fade in sunlight.

A week after the festival, a chair scraped across laminate in my shop office and Russell sat with popcorn he’d bought from a Boy Scout fundraiser. “You put on a show,” he said. “You okay?”

“Define ‘okay,’” I said.

“Sleeping?”

“Like a man who knows all four wheels are on the ground.”

He nodded. “Sometimes when something big happens, my brain keeps running the film all night. That ever happen to you?”

“Every night,” I said. We watched the camera feed—Valerie pacing in the kitchen, Reed pacing in the gym. It’s not kindness to stare. Sometimes it felt like diagnosis. The machine had reached its redline. The metals that had held up under ordinary heat were softening. If you’ve ever watched a bearing fail, you know that what looks like sudden death is actually cumulative insult.

The day the police showed up was a Tuesday. A domestic call. A neighbor said there was shouting, something about scissors. Reed had a chair cushion held like a shield. Valerie had the scissors. She wanted to “cut his lies off.” The officer wrote it up as a “disturbance,” not even misdemeanor assault, because sometimes the right thing is to give people a path out that doesn’t include a charge. The officer was my friend Jim, an honest man who hunts geese in October and never lies about his shot count. He came by the garage later and said, “Buddy, you’ve seen a lot of car fires. You ever hear a marriage burn?”

“Every day since I started,” I said. “Most people drive out of the smoke. Some keep chasing it until it eats their wheels.”

A month after my movie in the park, the house went to auction. A newly formed LLC with a forgettable name printed on a check bought it for twenty percent under market. The bidding wasn’t dramatic. Foreclosure auctions rarely are. The bidders are serious and quiet, like surgeons at a meat counter. I didn’t go. Frederick went. He sat in the back and texted me when the hammer fell. “You ‘lost’ your home. Some fellow bought it. Curious.”

“I hope he’s handy,” I texted back.

I rented the house later through an agent to a single mom with two boys and a husband laid up from a warehouse injury. When she came to see the place, she ran her hand along the banister like it was a rail on a ship she hoped would hold. I put the rent a third under market and fixed the hallway light I’d been promising to fix for a year. She cried a little. I looked at my shoes and pretended I needed to check the thermostat.

Whatever else I was, I kept being a mechanic. I still teach boys three nights a week how to listen for a misfire without a reader. I still tell women that any shop that laughs when they say “carburetor” is not a shop worth a minute. I still sleep on the cot once a month just to remember how the garage hums when no one’s breathing heavy in it.

Part IV:

“Trap” is a hard word. It conjures images of teeth and springs and suffering. The best ones aren’t cruel. The best ones are mirrors: they show people what they wanted to see, and then they show people what is true. The twelve-point font in Section 17 was a mirror. The bank’s sluggish freeze was a mirror. The HOA letter was a mirror. The movie was a mirror with sound. By then, the mirrors surrounded them like a funhouse with no exit.

Reed’s indictments came not with handcuffs first but with paper and the thump of a file on a desk. The county prosecutor, a woman I once helped move a refrigerator up a porch step, stood in front of a microphone and said phrases like “pattern of fraud.” The investigative TV program did a segment where an earnest host who had never in his life changed oil recited the lab findings of a “supplement” that was mostly the flour you buy in a brown bag. They filmed a B-roll of a scoop sliding through powder. It looked wholesome. It wasn’t.

Valerie made a deal with the HOA. Return what she’d “misallocated.” No prison. Two thousand hours of community service. The phrase “community service” is a blunt instrument in a sentence. Valerie wore a neon vest by the highway, picking up paper cups thrown by men who think windows are holes in the world. She wore sunglasses. She moved slower than the other volunteers. People honked. Some probably honked encouragement. She didn’t hear them that way. I watched once from the shoulder and then left because however petty I have felt in my life, I don’t want to measure my worth against someone else’s punishment.

The day Reed went in, I was changing out a radiator on a Chevelle and the phone blipped with the news alert. “Local man sentenced in fraud case.” Eighteen months with time served, mandated restitution he’d never fully pay. He walked into county wearing a shirt that had once made women double-take at the gym and now just made him cold. He had that look some men get when the only thing they’ve been told is true—“you deserve”—gets peeled off like a bumper sticker that tears in ragged strips.

I didn’t celebrate. And I’m not trying to make myself a saint. There’s no sainthood in strategically opening valve cores at dawn. But I didn’t celebrate, because by then the spectacle had cost me something I could only describe by its absence: some gentleness I liked in myself. I could feel its outline like a wrench missing from a drawer you reach into every day. I thought about calling Valerie. I didn’t. I wrote instead. I wrote every night after closing—spilled on paper what I didn’t know how to drain from myself any other way. I wrote about bolts and vows and how a good gasket isn’t so different from fidelity: cheap ones leak; expensive ones also leak if you install them on dirty surfaces.

The LLC that bought the house kept its secret a secret. The agent who handled the rental handled the tenants and handled the lawn service and handled the bills. The neighbors speculated because neighbors are detectives looking for casework. “A banker,” one said. “A YouTube guy,” said another. “The mechanic,” a third whispered, not because he had evidence but because gossip is a coyote that chews off its leg to run.

Some nights, when the shop was a cathedral and every tool hung in its pew, I’d roll the Mach 1 out and just look at it. The car had been a husk when it arrived—rot in the rear quarters, mice in the trunk, a motor that coughed like it smoked unfiltered. A year later, it was a sin in metallic red. I’d saved the Hermes scarf from a box of Valerie’s leavings and turned it into my polishing cloth. People say that’s petty. It might be. But rubbing that car with that scarf felt like the right ritual: the thing once valued for status now earning its keep by serving shine. Every symbol in this life should either earn its bolt or be melted down.

One afternoon, a neighbor named Jerry came by with a Briggs & Stratton mounted to a mower deck that had seen more summers than I plan to. “You hear about the barbecue festival?” he asked me, even though I had put on the show.

“I heard,” I said.

“You did the right thing,” he said. “Plenty of us felt crazy these last couple years. Like we were the only ones who noticed the HOA turned into a collection agency for petty tyrants.”

I shrugged. “Everyone sees what they need to see when it benefits them.”

Jerry squinted. “You sure you ain’t a preacher?”

“Just a mechanic,” I said. Which is the same thing on the right days.

He told me the rumor about the buyer of our old house. I told him I hoped the buyer was kind. He told me he’d heard Reed was writing a book inside. “From Wellness Coach to Cell Block,” Jerry said, chuckling. “You can’t make this stuff up.” I said nothing, because I know you can, and we did, and we do all the time. We make up things to live by: codes, slogans, prayer. The trick is choosing ones that don’t snap under load.

Frederick came by that week, and we drank beer on milk crates behind the shop and watched the sun find chrome. “You going to date?” he asked, like a brother would. “Ever?”

“Date who?” I said. “I’m married to a dynasty of steel.”

“You can love more than one thing,” he said.

“That’s what got me into this,” I said, and he laughed.

He asked me if I regretted the second mortgage. I said I regretted the moment my marriage became a chessboard and not a table where people ate together. He said that was a dodge. I said he was right. I said, “I regret learning I’m good at games I didn’t want to play.” He told me that’s what grown-ups sound like when they figure something out they didn’t want to know.

I took on three apprentices around then: young men with knuckles too smooth and hearts too loud. “You’ll learn patience,” I told them on Day One. “Or you’ll learn to leave.” I teach them the same way I talk to my cars: low voice, clean questions. What are you hearing? Where’s the leak? What are you assuming? A good mechanic interrogates his own certainty until certainty earns its keep.

Valerie finished her service hours in a year and a half. She moved to a condo thirty miles away near a retail cluster that sells hope in flat boxes. I know because a woman brought in a leased Corolla from that complex with a clunk that turned out to be a spare tire gone rogue in the trunk. People gradually stopped saying Valerie’s name. The neighborhood photos of the barbecue festival were replaced with photos of babies and dogs. Time wears people down and then rounds them off.

Then, out of nowhere, four years after the receipt that cracked the casing on my life, a letter came from the county clerk about a matter “in re: property taxes and release of lien.” Bureaucracy has an awkward poetry to it. I took the letter into the office and opened it with my pocketknife, because old habits don’t die; they ossify. The letter informed me that the second mortgage had been satisfied. The LLC had paid it in full. “We are notifying you as originator.” My bank account was fatter than it had any right to be. If this is where you want the story to say that I became rich off revenge, I can’t help you. What I became was solvent. What I became was able to replace the lift without feeling like a traitor.

I pinned the letter on the corkboard and stared at it like a parts diagram I didn’t understand. Then I took it down, slid it into a file with my divorce decree, and went back to the Mach 1.

Part V:

The first time I drove the Mach 1 out after everything, the sun did that thing where it’s ridiculous about being itself, making every surface look like it was paid to do it. I let the big V8 lope. I let it nose down the main street. People waved. A kid yelled, “Cool car, mister!” and I almost cried, which is not a thing I do often or well. I took the long road to the coast—not because the coast is close, but because the long road anywhere feels like vacation to a man who hasn’t been out of town in three years. The air off the water is a joke we tell ourselves about freedom. You roll down the window and pretend it’s blowing your troubles away, and maybe it is, because troubles consider themselves too important to cling to hair.

The car ran like it should: out of apology and into grace. On the way back I stopped at a diner I’ve loved since the clerk at the auto parts store told me about it. The waitress called me “hon” and I accepted the compliment without flinching. A man at the counter glanced at the OLD DOG patch on my shirt and said, “You that guy from the video?”

“I’m that guy,” I said.

“Helluva thing,” he said. “You made a lot of folks feel seen.”

I told him I’d probably made a lot of folks feel stared at, too. He said both things can be true and refilled my coffee. People who work in diners are priests who serve penance in cups.

It would be a better story if I told you I met someone who loved me exactly the way I am and we went off to buy farm eggs on Saturday mornings. I didn’t. I dated a woman who sold tickets at the minor league stadium. She liked my hands and my stories and then decided she liked late-night music more. I dated a teacher who smelled like chalk and patience and then moved to be near her sister. I dated no one for twelve months and discovered I am good at making dinners for one. Rebuilding is like that. You place each new plank. You check for rot. You sand and prime. If the paint doesn’t catch, you sand again.

Old Dog Garage grew in those years. The video didn’t hurt. People like a craftsman with a tale. I added a second lift and sent Russ to night classes because he has ownership written in his shoulders. I put Tom in charge of inventory because he has the brain of a ledger. I took Saturdays off for the first time since the third Bush was president. I started going to estate sales and buying coffee cans full of a dead man’s fasteners, which is both melancholy and efficient. I label each can in block letters now, because life is too short to hunt for a 10-32 in a salad of possibility.

Every few months, someone asked about the Hermes scarf on the pegboard. “That’s a story,” I’d say, and someday I’ll tell it, but today it’s a polishing cloth. It makes sense to me that something designed to display wealth now serves it by making metal bright. It’s a conversion at the altar of usefulness.

One steamy July afternoon, a boy with a skateboard tucked under his arm walked in and asked if we hired teenagers. “You wouldn’t like the pay,” I said. He said he didn’t care. I said that’s the first sign he won’t like the pay. He laughed. I said, “Come back tomorrow with your mom and I’ll explain workers comp and why it’s my least favorite phrase.” He did. His mother looked at my hands and nodded. “Hard work is the only therapy that took with his father,” she said. “Maybe it will take with him too.”

I taught the boy how to wind hoses without twisting the soul out of them. I taught him how to sweep from far to near. I taught him to stand back and look at a car for a full minute before you touch it, because the first impression is the map you never get again. He left for college two years later and came back at Thanksgiving with a grin that said he’d kissed someone on a roof and found it to his liking. He still texts me when his roommate’s Civic makes a sound like regret.

One evening, about five years out from the receipt, I was closing up when a woman came in with a flat that wasn’t her fault and a phone that had died at twenty-three percent because phones take a dive when you most need them. She wore no ring. She wore a navy dress that looked like work but not court. I put air in the spare and torqued the lugs because torque is love. “We still trust men with wrenches?” she asked with a half-smile.

“We should,” I said, “but verify.” She laughed at that like a woman who has verified. She paid with cash, which I admire the way some men admire architecture. On her way out she glanced at the scarf on the pegboard and said, “That color looks expensive.”

“It did,” I said. “Now it looks helpful.”

She introduced herself as Mae. She taught home ec—or whatever they call it now that we pretend people don’t eat at tables—at the middle school. She asked if I’d come talk to the kids about basic car care because the boys were outpacing the girls and she didn’t like how that looked. I said yes before she finished the sentence because the idea of a twelve-year-old girl cracking a lug nut like a pro makes me grin in a way that can’t be faked.

I stood in front of that class the next week and showed them how to check tire pressure. The girls lined up, their ponytails like question marks. The boys jostled and tried to act tall. Mae stood by the whiteboard and watched like she was calibrating a tool. Later she came by the shop and we had tea, because I can drink a thing that isn’t coffee if I do it with someone who knows how to talk without filling silence with explanations. I told her about the Hyatt receipt without saying Hyatt. I told her about a machine that stopped being a machine. She told me about a marriage that never learned to use both oars. We didn’t look at each other when we told those stories. We looked at the floor. The floor was clean.

I don’t know where that goes. I only know that telling the right person the right story at the right time feels like oil finding the right channel. People only seize when the lubrication fails.

And here’s the thing I kept from myself as long as I could: I had been cruel. I had not been wrong, but I had been cruel. If you think those things are mutually exclusive, you haven’t lived long enough to distinguish a clean cut from a jagged one. The film at the BBQ had been true. It had also been showy. I put on the show because I wanted witnesses. I wanted to be believed. But there is a way to be believed that doesn’t require the humiliation of a person in a microphone’s shadow. I chose the road that felt like victory because I had lived too long in the drive-through lane of concession. This is not an apology so much as it is a measurement. If I had to take it apart again, I might torque it one notch lower.

Meanwhile, the world keeps doing what it does: new neighbors moved in and then moved out; the city resealed the street and the tar stank like childhood; the boys on the corner got loud in the summer and quiet in the winter; someone spray-painted a word on the back of the liquor store and someone else painted it the color of surrender. I fixed cars. I learned to make a gumbo that would make my mother shut up and eat. I sent my apprentices home when they were mean to each other because kindness is part of the warranty. I stood in my own house sometimes and felt the light move across the floorboards like a promise that, one day, will be kept.

Part VI:

Valerie called me exactly once after everything. That “after” includes auctions and vests and indictments and a book rumor. It was a Tuesday, which is when tragedy likes to call if Monday is too obvious. I almost didn’t pick up because I’ve spent a lot of my life learning how to say no without saying it. “Ellis,” she said when I answered, and her voice had the surprise of youth in it, the way it was before we bought furniture as compromise. “I’m not calling to fight.”

“Okay,” I said.

“I wanted to say I’m sorry,” she said. “For what I did and for what I thought and for how I used you as a mirror when I should’ve used you as a wall.”

That’s one of those sentences you have to let into the room and make it take off its shoes before it tracks up your new rug. I said nothing. I heard her breathe. “You were always good,” she said. “I mistook quiet for small. That’s on me.”

I told her I hoped she loved someone the way she had wanted to be loved—without an audience. She laughed a little and said she was building a life that didn’t look like a brochure. “I work mornings at a bakery,” she said. “I come home smelling like cinnamon.” I said cinnamon suits her better than the kind of perfume that makes men think of credit limits. She told me she sees a therapist and I told her that’s a tune-up I recommend to anyone who likes to keep moving. We hung up with a gentleness I would’ve paid good money for back when money would have done any good.

The HOA runs like a tame animal now—no wild fines, no sudden mandates that all shutters must be robin’s egg. The new chair still audits like it’s his favorite song, but now there’s this thing called “community input” that isn’t just a flavor of ambush. People show up to meetings and argue about crosswalks and whether the pond counts as an “amenity.” The homeowner newsletter now includes recipes and a column I write once a quarter about maintenance. “An engine isn’t magic,” I tell them in the first one. “It’s work organized. If you do the work, the magic shows up to say thank you.”

Reed’s book came out online as a PDF no one would publish. It had a lot of long paragraphs about “mindset.” He wrote about “haters.” He wrote about me without writing my name, calling me “a small-minded adversary with a wrench for a brain.” The part that nearly made me laugh into my coffee was when he wrote about his “commitment to truth.” He spelled it “truths” and I decided not to mail him a dictionary because I’m trying to be the kind of man who lets typos do their own preaching. I read ten pages. I closed the file. I went back to work.

On Sundays I drive the Mach 1 with the windows down because air-conditioning is a convenience I reserve for Monday through Saturday. I take the coast road sometimes, and other times I just make a big loop through neighborhoods where lawns smell the same and kids look different and men wave from porches like they’ve got a secret—maybe they do. Sometimes I drive past the house I “lost.” I don’t stop. The renters keep plastic toys in the yard. The bikes are left leaning against the garage in a way that tells you their riders are loved. I feel something like ache, but without the complaint.

Once, the single mother who lives there flagged me down from the mailbox. “You’re the owner, right?” she asked.

“I used to live here,” I said, because “owner” is a word I’m tired of wearing.

“You’re the mechanic,” she said, and it wasn’t a question. I told her that was true. She said her dryer was making a chirping sound. I told her I’m not an appliance guy but I can listen to anything. I went inside and listened. The belt had a fray in it. I replaced it with a belt from a hardware store that still smells like wood. She tried to pay me. I told her to put that money into soccer cleats or a class trip or a winter coat. She cried a little and said she’d make me a casserole. I said okay if it’s not tuna.

In the shop, we keep doing the work. Russell now uses “sir” in a way that makes me tease him for the military he left behind but never really leaves. Tom got married to a woman who writes code for a living and fixes cabinets for fun. The apprentices turn into foremen. I’ve had to learn to stand back and let other people lay hands on the engine first. It’s hard to let go, the way it’s hard to let a son drive a car you rebuilt yourself. But the joy in seeing a problem solved by someone who once called a socket “that spinny thing”? There’s no way to message that to a bank. That’s your yield.

When customers ask about the scarf on the pegboard, I explain it simply so I don’t have to relive anything: “It’s a reminder that things can change jobs and still be beautiful. Some things only get useful after they stop trying to be impressive.” People nod. A few blink more than usual. One woman said, “You’re talking about marriage,” and I said, “I’m talking about machines,” and she smiled like she knew those were sometimes the same.

The ending you asked me for—the clear one—isn’t a swordfight or a checkmate or a walk into a sunset where the film forgets everyone else and focuses on two bodies silhouetted against an unearned sky. The ending is this: I turned a disaster into a shop that hums. I turned a scarf into a cloth. I turned a man who thought he was loved because he was needed into a man who is loved because he is useful and kind. Valerie turned herself from whatever it was she had become into something with flour on it. Reed turned himself into a lesson on a day when I didn’t have to be the teacher.

Revenge is a dish cold because by the time it’s served, heat is a luxury. But I don’t think that’s the right metaphor anymore. Revenge is a machine: it’s bolts and belts and the certainty that if you tension it too tight, it tears; too loose, it squeals. I built one. It ran. I don’t keep it in the shop anymore. I junked it. I prefer the machines that take people places and bring them back with a story.

On the pegboard, under the scarf, hangs a note that says, “Check your tires.” I wrote it the morning I let the air out of four of them and listened to the hiss that made me feel powerful. It’s there to remind me that the clever thing isn’t always the honest thing, and that sometimes the opening bell for a “grand performance” is just a man doing the smallest, meanest version of control. I am not ashamed of that morning. I am not proud either. I am a man grateful for the chance to rebuild, for gaskets that seat when you clean the surfaces properly, for camshafts that sing when you give them the right valley, for boys who learn to sweep without raising dust.

If you want the last line—it’s this. I drive the Mach 1 along a stretch of road that knows my name. The engine talks the way a friend does, low and sure. The ocean pretends it’s the only thing that moves. I think of a hotel receipt folded twice and the way a life can be folded and then unfolded and still smooth out enough to write on. A gull drops a shell on the road to crack it open, and I laugh out loud because even birds understand leverage. I signal, I turn, I head home to the garage that has my smell and my history and my future inside it. The bay door rolls up like a curtain, and there’s my kingdom: lights high and warm, floors clean as a promise, tools aligned like a choir. I park, I cut the engine, and I sit for a minute in the tick-tick after of a hot car cooling. Then I go inside, hang the keys on a hook that says MACH, and start the kettle. There’s always tea now, sometimes with cinnamon, and sometimes I drink it with someone who knows how to listen without trying to fix what isn’t broken.

That’s the ending. Not a bang; not a whisper. Just a man who learned that wrenches don’t lie, that engines tell the truth when you give them half a chance, and that if you keep your hands busy with honest work, the rest of you has a shot at being honest too.

THE END

News

She Came Back From Her Affair Acting Normal — Until One Step Into Our Bedroom Changed It… CH2

Part I It was 3:17 in the morning when she assumed I was asleep. I lay on my right side,…

I Was In Labour Begging My Parents To Take Me To Hospital They Left Me On Road Dad Said Die On Road… CH2

Part I: I was twenty-five when my body finally spoke louder than my fear. The first contraction took my breath…

“Why Can’t You Be More Like Her?” He Asked — So I Stopped Trying to Be Anyone Else. Now He’s… CH2

Part I My name is Irene Betts, and I learned the hard way that love doesn’t always go out like…

After my husband passed away, my son became the CEO of the family business, and I pretended I hadn’t… CH2

Part I I was arranging lilies in the blue vase Richard bought me in ’83 when I heard my daughter-in-law’s…

On My Wedding Day, Not a Single Family Member Showed Up. Not Even My Father Who… CH2

Part I: There are moments in life when silence becomes a living thing. On the morning of my wedding day,…

CHEATING WIFE gave birth to affair child, i refused to sign birth certificate… CH2

Part I I didn’t hold the baby. I didn’t kiss my wife on the forehead, or tremble, or weep the…

End of content

No more pages to load