The Ceiling, the Stain, and the Lenses I Never Meant to Use

At two in the morning the ceiling was a map of oceans, and I drifted along their blank white continents because sleep wanted nothing to do with me. Laura’s breathing beside me was steady, calm, the soft tide of a woman who had learned how to keep the world from touching her. Every creak in the rafters above us sounded like a footstep I couldn’t place. Every buzz from the phone on her nightstand—face down, always face down—felt like a gunshot in an empty street.

The stain in the hamper wouldn’t leave my head. A shade too dark, a place it had no right to be. I told myself it might be wine or grease from a restaurant kitchen, or those rust-colored freckles a washing machine coughs up from old pipes. I told myself a hundred things and believed none of them. Twenty-three years with Laura had taught me her rhythms—how her thumb hovered over the text bubble when she was crafting a lie, how her lips pressed tight when she was about to argue a point to the death, how her heels clicked different when she was late for court than when she was late for home. Something in her rhythm had fallen off-beat. Lately, it all sounded like a metronome the devil had been tapping.

I slid out of bed, padded down to the kitchen, and cracked a beer because men in my family solved fear with terrible solutions. The house hummed in its usual suburban lullaby: the refrigerator’s slow throat-clearing, the air conditioner exhaling like an old dog. Our daughter Emily’s high school photographs were lined on the wall—graduation robes, softball trophies, braces she complained about daily and thanked us for later. I put my hand on her sophomore frame and felt the glass cool as a lake in January.

On the counter sat the small black hub I’d installed two months earlier after the break-ins on our street. Six houses down a widower had woken to a stranger at the foot of his bed. The neighborhood watch exploded with emails and fear. I work as a plant engineer; I think in contingencies and redundancies and, when my hands shake, in floor plans. So I bought a security system and installed it on a Saturday while Laura was at a “strategy brunch.” Door sensors. A couple motion detectors. And—because the package deal made it cheaper and because fear is a generous salesman—two battery-powered cameras small as matchbooks: one above the garage and one tucked into a hollow of the kitchen crown molding. I told myself it was about the house, about our things, about making sure Emily felt safe when she visited on weekends from her apartment across town.

I forgot to tell Laura about the inside camera.

When I say “forgot,” I mean I left it off my list. The first week it blinked red, indicting nothing more than our cat vaulting onto the countertop. The second week it blinked when I walked to the fridge at three a.m. The third week it blinked when Laura came home late and leaned hard against the kitchen island like it was the only thing holding her up. I watched the thumbnail the next morning and told myself the camera would catch the man who didn’t belong in our house. It never occurred to me the man who didn’t belong was in every mirror in the place.

That night, the stain kept flashing across my thoughts like a warning light on an instrument panel. I opened my laptop and the security dashboard bloomed—grainy monochrome boxes of our empty rooms. The kitchen stood still, chairs tucked, the island clean. I scrubbed back in the timeline bar to nine-thirty. The front door opened; Laura stepped inside, blazer folded over her arm like a surrender flag. She set her purse down, tossed her keys into the ceramic bowl Emily made in ninth grade, and for a long beat just stood there, eyes closed, shoulders slack. No one was behind her. No intruder. No monster except the one in my gut.

She took out her phone and typed fast, careful, smiling a smile that wasn’t for me. She looked up once, and for an instant I swore she was looking straight into the little black hole near the ceiling—through it and into me, a husband perched on a kitchen stool months later and miles away. Then she turned, walked to the sink, and rinsed a wine glass without having used it. She pulled her blouse’s hem, held it up to the light. She frowned, folded it inward, and disappeared down the hall. The camera blinked twice more and slept.

A sane man would have closed the laptop and gone back to bed. A better man—whatever that is—would have confronted his wife with the simplest arithmetic: if A, then B; if stain, then truth. But I am an engineer, and we are trained to collect more data than we need, to draw lines between screws and bolts until the machine reveals its shape. I clicked to the hallway camera, which I had held back from mounting because the motion sensors felt like enough. And then, for the first time, I thought about installing it for a different reason.

“Don’t,” I said aloud to a kitchen full of no one. The cat blinked at me like a witness. I finished the beer and stared at the black hub where the timeline still glowed. The word loomed like a cliff: Proof. Proof can save a life. Proof can end one. Lawyers like Laura understand the alchemy. Put the right pages in the right order, and the shape of the world itself bends toward what you need.

I waited until morning.

Laura floated in at seven-thirty in that way she has, a cross between a judge making an entrance and a girl stepping onstage at her first recital. She kissed my cheek, said, “You’re up early,” like it meant anything, and poured coffee. “How was Boston?” I asked, not letting my eyes flinch. She said the words like she’d practiced them: “Boring conference. Terrible hotel food.” She smiled the lawyer’s smile—polished, pleasant, unfelt. I slid her a mug and asked which client. “The Patterson group,” she said, and the sound of it in my kitchen was like someone else’s ringtone going off in a church.

We don’t talk much anymore, I almost said, but the sentence was a strip of barbed wire between my teeth. She reached across, pressed her palm to the back of my hand. “Dinner this weekend, just us. Somewhere with real food. I’ve missed you.” The heat of her hand should have soothed something. It lit a fuse.

I went to work and pretended to read blueprints. Every line on the page was a road to a place I didn’t want to go. At noon I drove home under a sky the color of old paper. In the hallway closet, behind a stack of winter scarves, I found the little unmounted camera still in its taped box. I stood there for a long minute listening for the part of me that knew how to be decent. He must have stepped out.

Here is the part I won’t dress up with philosophy: I installed it. Not a schematic, not a how-to, not the model number—just the admission. I tucked it where the baseboard meets the bookcase in the living room, a small eye into the space where we laugh and do not laugh. The kitchen had its sentinel, the living room had its witness, and I had a way to stop guessing. I told myself—this is the terrible truth—that I was protecting the house. We engineers like to drape our ugliest impulses in words like safety and redundancy. Call a trespass a policy and it starts to feel less like a sin.

That evening I played the husband. I grilled chicken and oiled the asparagus like I’d seen on the Food Network and asked Laura about depositions. She gave me the bones of her day the way a magician shows you his left hand—something to keep your gaze while the other hand makes the dove appear. She laughed twice at jokes I hadn’t told. When her phone buzzed, she ignored it, but there was an angle to her jaw she forgot to smooth. At nine she set the laptop on the desk, logged out, and stood to stretch. She was beautiful in that way a sculpture is—no longer soft with the years, but somehow more precise.

She said she had emails and kissed me goodnight, scent of citrus and iron like victory medals. I went to the kitchen and sat at the island like a sentry. The hub pulsed; the thumbnails stitched a silent movie. Laura opened her inbox. One, two, three messages flicked in and out, filed like silverware. Then the browser history opened, then a tab with a title that told me nothing: SL38. She typed, backspaced, typed. I could see the words on her face if not on the screen. A certain smile lubricates a certain kind of conversation.

When the living room thumbnail bloomed, I watched myself—another version—staring back from the blank TV, my eyes wide and dark like the house had swallowed my face. The tiny camera looked at me looking at her. I clicked to enlarge, my heart going the rhythm a storm set. I wanted to be wrong, to be embarrassed, to laugh in a week about the night I played detective in his own living room.

Instead, I watched my wife log out of the account she uses for court exhibits, log into another, and disappear into a door I never knew we had.

Our marriage had always been a house. That night I found a hidden room. I would tell you I knocked. I didn’t. I jimmied the lock with a husband’s fear, and when it cracked open, the air inside smelled like strange perfume and something burned sweet. I went to bed and lay beside her while she slept, and I listened to the quiet engine of her breathing and thought about the eyes I had tucked into the woodwork all day. I had installed a courtroom. Tomorrow, I would argue against the woman I loved.

At dawn I brewed coffee I didn’t drink. I opened the laptop. I dragged the living room footage onto the big screen because secrets need space. I scrubbed to midnight. Laura typed. I watched the reflection in the black TV glass—a trick I taught myself as a kid to read the grade my father wrote on my report card before he turned it around. A username came into view in backward ghost letters on the TV: sophisticated_lady38. Then a site name I’d never seen. Then a list of messages that made the floor tilt.

I didn’t read them all. I didn’t need to. I saw Boston in three threads, Hilton room 312 in one, presidential suite in another, and a string of texts with the heat of a fever. I breathed in. I breathed out. People tell you anger is hot, but in me it went cold. Cold is how metal breaks.

From the hallway, Laura started the shower. The house filled with water noise like rain. I closed the laptop, slid off the stool, and leaned my forehead against the glass of Emily’s sophomore photograph. “Tell me,” I whispered, “how you would build a person who could survive this.”

Emily smiled at me from thirteen years ago, braces shining like a city skyline. The world was simpler then. The cameras were friendly little things we took to the beach.

By nine that morning I had discovered a new capacity in myself: I could be two men at once. I could be Jack the husband, who kissed his wife’s temple and told her the coffee was good. I could be Jack the engineer, who opened the house like a blueprint and traced the load-bearing lies with a fingertip.

I forgot to tell my wife about the hidden cameras I installed.

So I decided to just watch.

And watching makes you think you know the thing you are watching. That is the first, smallest lie.

Proof Isn’t Mercy, It’s Weight

If suspicion is a splinter, proof is a spike driven through the wood—clean, straight, immovable. I had both now, and there was nowhere to set them down.

I told myself I would gather only what was necessary, as if a person could ration obsession the way a dieter rations bread. I limited myself to “reasonable” steps. The hallway camera captured a reflection of Laura’s laptop in the glass of a framed diploma; the living room lens caught the flex of her hands on the keys; the kitchen eye watched her set her phone face down beside a mug and smile at its steady, secret thrum. I stitched those angles together and made meaning the way a child makes a constellation out of dots. The shape of it wasn’t vague. It was a face I recognized. My wife’s—lit with a joy that had very little to do with me.

I told myself I wouldn’t invade her email. That line lasted two days. She had used our wedding date as a password once—the year we bought the Subaru and she forgot the dealership login. It was muscle memory, not cunning; my hands typed what my ghost remembered. The screen stalled, blinked, acquiesced. I stepped into a room scrubbed spotless: inbox empty, trash empty, even the junk email clear as a showroom floor. But broom marks leave trails if you know how to look. I found the dust in archived labels named for clients and cases and, tucked where I would never have searched if not for the reflexes of a man who organizes tool chests by torque ratings, a folder called SL38.

When I opened it, a door swung wide and the temperature in the room dropped ten degrees. The email wasn’t the house; it was the street outside, neon-lit with places you could go if you knew the password. Avatars. Handles. Rendezvous threaded neatly into subject lines. The names in the chain read like a joke you tell in a bar: a doctor, a cop, a professor, a rival, and a boss walk into a marriage—

No nude photos waited there. Laura is too careful for that. But she didn’t need to strip. She offered words and times, hotel confirmation numbers, receipts with dates that marched in lockstep with every “late deposition” on our shared calendar. I didn’t print anything—paper made it feel like work. I exported it instead. Screenshots. Encrypted files inside files. Redundancy is the engineer’s lullaby.

I watched the kitchen camera at 6:42 p.m. on a Wednesday when she told me she had dinner with a client named Branford. The tracker app I had told myself I would never use pulsed, and the dot with my wife’s initials slid toward downtown. I followed at a distance, headlights off in twilight, two cars between us because I’d seen that in movies and because distance is the lie men like me tell ourselves so we can pretend we aren’t exactly the thing we are. She parked near New England Medical Center and emerged good as new—fresh lipstick, smooth hair, purposeful stride. Beside her was a man with the kind of face that made nurses feel safe. Tall, coat slung over a shoulder like a privilege, hand low on my wife’s back as if entitlement were a muscle he’d trained.

They kissed under a pool of hospital floodlight. Not a peck, not a maybe—we all know the shape of a kiss for hello and the shape of a kiss for history. This was the second kind. I took photographs from the shadow of my wheel well. The old camera felt heavy as a wrench.

I didn’t confront her after that. I made dinner. I let her talk. The lie had a rhythm, and I wanted to hear if it wavered. It didn’t. She’d been doing this a while. Professionals call it “composure.” I called it practiced treachery and poured the wine so my hands had a task that wasn’t shaking.

The next afternoon I stood outside a police bar so dark the neon sign above the door looked like a dare. Detective Ray Johnson—the name I recognized from a thread that read like a parody—sat at a stool texting the posture of unassailable men. Wedding ring. Tan line just beneath it. Laugh that tried to bite. I waited until he went to the restroom and followed him into the hum of fluorescent lights.

“Detective Johnson,” I said, my voice polite like a man asking a stranger for directions.

He turned, eyes narrowing. “Do I know you?”

“You know my wife,” I said. “Laura Miller.” I paused, because I wanted to see the way guilt travels across a face when it’s not ready to be seen. It’s fast. “Or maybe you know her as sophisticated_lady38.”

A color left his skin I didn’t know a healthy person could lose. “Look,” he started, a cop again for a moment, “if you’re making some kind of—”

I held up my phone. There are pictures you don’t have to explain. The one I showed him—the Hilton’s back door, a hand at a familiar waist—needed no caption. “Your captain’s email is easy to guess,” I said, keeping my tone level because I had learned already that cold hits harder than heat. “Your wife teaches at Brookdale Elementary. I admire teachers. I bet the school board admires fidelity.”

He held up his hands—not surrender, exactly, but the universal sign for let’s both pretend this is a conversation and not a blackmail. “I don’t want trouble. I’ll end it tonight. You won’t see me again.”

“You already ended it,” I said. “Now you’ll decide whether your wife finds out how.”

He swallowed. The tile seemed to move under the soles of his shoes. “Please.”

“I’ll know,” I said, and the way I said it made me a man I’d never intended to become. The camera at home would confirm what his texts would later prove: the thread with Ray dried up to a single line—I can’t—then went silent. The kitchen camera caught Laura reading it twice, jaw hard as granite. She didn’t cry. She filed the hurt where she files all the verdicts she can’t appeal.

Men like Ray aren’t special. Another name carried the fancy of sonnets: Richard Hall, professor of English literature at Northeastern, a man who weaponized couplets and favorite lines to pry at the boredom married people don’t admit they feel. I waited for him in his office when the campus had gone mostly quiet and the janitor’s cart squeaked down the hall like a metronome. When I said my name he took off his glasses as if not seeing me would make me less real. I set a folder on his desk thick with the kind of proof that sinks tenure. I suggested a resignation letter now would hurt less than a public hearing later. He wrote it with a pen that bled. He didn’t argue: the guilt in him was a ready room.

Power changes your metabolism. You think you’ll feel sick, but if you’re not careful, you’ll feel strong. After Ray fell silent and Richard folded, I sat in the car and looked at the city lights making a crown of the skyline and felt something steady in me that had nothing to do with goodness. I whispered, “I see the whole board,” and believed it.

Patricia Vance was not a board piece. She was a mover, a senior partner at a firm that devoured people like Ray for breakfast. Laura’s rival. Her text thread with Laura wasn’t romance so much as a power exchange written in litigator shorthand: Tonight I want control; yes ma’am; hotel; eight-thirty. Power recognizes power. I didn’t take Patricia on directly. I approached her husband, Councilman Thomas Vance, at a gala where he stood behind a podium and praised the sanctity of marriage with the confidence of a man whose tie always sits right and whose donors love photographs of his family in sweaters.

When he stepped down, I met him in the wing with a politeness I no longer deserved. I showed him the picture. I didn’t need to say anything. Men who build careers on moral scaffolding understand collapse when they see it. The next week, Patricia’s life burst in media bloom the way wildflowers bloom in a ditch: fast, bright, damning. Her firm asked her to take a leave. The councilman’s campaign shaved his name from its banners like a haircut gone bad. On our couch that night, Laura watched the news with a blank face and a single twitch—the left eye, very small, very quick. She didn’t mention Patricia. She didn’t have to. I saw the algebra. She had no idea how, only that my silence had grown a spine and was moving through her world without asking for permission.

Frank’s name was the last I wanted to see. My old boss. Mentor. A man who’d toasted at our wedding and whose advice steadied me through the death of my father. His texts with Laura ached less with desire than with a certain middle-aged vanity: you deserve better; passion; I can be what he isn’t. I met him at the deli we used to haunt and asked how long he’d been sleeping with my wife. He wept in a way that was honest. I didn’t forgive him in a way that wasn’t.

All of this unfolded while the house cameras quietly watched me become a stranger. The kitchen eye saw me pour coffee I wouldn’t drink. The living room lens saw me stand before the wall I built in my office: a timeline with colored tabs, threads of twine mapping Tuesdays to hotel addresses to credit card tolls. Blue for Marcus, red for Ray, green for Richard, gold for Patricia, black for Frank. From a distance it might have looked like art. Up close it was a mausoleum before the bodies arrive.

The last part of the plan required an institution—New England Medical Center, where Dr. Marcus Brown wore a white coat and a handsome face and a smile that had convinced my wife to forget her vows. I didn’t call pretending to be anyone grand; I simply brought what I had to someone who could be moved by it. Unethical, I said—the word doing the heavy lifting I couldn’t. They took me into a small conference room that smelled like lemon cleanser and put on glasses that meant they were about to become a process.

When I left the parking garage, the sun was low and mean. My phone vibrated hours later with a message from a nurse I didn’t know: Is it true about Dr. Brown?; suspended?; no one will tell us. The kitchen camera recorded Laura walking in circles, bare feet whispering against the floor, phone glued to her ear. “I don’t understand,” she kept saying, which in Laura’s mouth always meant I don’t like this outcome.

I wish I could say I felt triumph. I felt precision.

At midnight she sat on the edge of the bed and tried to cry in an elegant way that wouldn’t smear the mascara she’d forgotten to remove. I stood in the doorway and let the silence be the river we both had to cross. “Rough day?” I asked, voice a temperature I didn’t recognize. “Office politics,” she replied to the carpet.

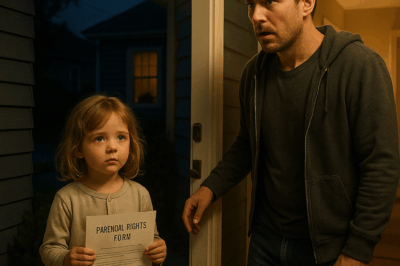

I set the folder on the bed like a verdict and watched her read the life she’d been living. The living room camera caught the shape of her shoulders caving under the weight of paperwork. The kitchen camera recorded her hands shaking when she reached for water. The hallway lens saw me stand as still as a hung portrait.

“Tomorrow,” I told her, every word placed carefully like a tile in a mosaic, “you call your attorney. You file quietly. You leave with what you brought into this house. Not what we built in it.”

“If I don’t?” she asked, and there was one thin sliver of fight in it, like a single hair caught in her tongue.

“Then everyone gets a copy,” I said. I held up the phone. The room glowed with everything I had become.

She packed in the night, the cameras recording a woman erasing herself in a hurry. She left without a note, and the house felt like a lung that had just exhaled everything. I walked the hall and paused beneath each little lens as if they were priests in a line, and I waited for absolution that did not arrive.

Something Like Justice, Something Like Ruin

I had imagined the morning after as a clean ledger. The columns didn’t balance. The house had never been more mine, and I had never felt more like a tenant in it.

Emily called. The line carried her voice from the distance of a daughter who has learned to defend her heart. “What did you do to Mom?” she asked, not what did Mom do to you, which is the question I had rehearsed answers for in the shower. “She says you’re stalking her, that you threatened people, that you’re—” and here her voice buckled, surprisingly, into the word—“unhinged.”

“Em,” I said, steady because my anger had learned to put on a suit, “your mother—”

“I don’t want to hear it,” she said, and hung up with the efficiency of the young. I stood in the kitchen and touched the ceramic bowl where Laura’s keys used to land, and for the first time since I started building my wall of evidence, I felt the first flake of ash on my tongue.

You can win a battle and lose your face in the mirror.

I pushed through the next days by muscle memory. I worked; I nodded; I made eggs I didn’t taste. I refreshed the hospital rumor mill until the page felt like a bruise I couldn’t stop pressing. Marcus suspended pending inquiry. Colleagues shocked. Patients “devastated.” The words all belong to the same paragraph you get when a shining person rusts. It should not have satisfied me; it did.

It also invited a response.

Murphy’s Pub turned on a low light that made the dust in the air look like snow. I was on my second beer when the shadow fell across the table. The man who slid into the booth looked nothing like the doctor who had held my wife’s waist under hospital floodlight. Marcus’s edges had frayed: jacket wrinkled, eyes hot with the kind of anger that has nowhere useful to go.

“You think you won, Miller?” he asked. When men sharpen your name into a knife, it tells you exactly how they’ve been tasting it in their mouths.

“I think you built this,” I said, and kept my hands on the table where God could see them.

“You cost me my job, my license, my—” his voice broke into a laugh too short to be honest—“my family.”

“You destroyed yourself,” I said, because the sentence fit like a coat I had tailored. “I held up a mirror.”

“Then here’s yours,” he said, and delivered it without flourish. “Laura’s pregnant.”

My body forgot how to be a body for a beat. “No,” I said, because we say no to gravity all the time as if we can stop the floor.

“Three months,” he said. “And no, it isn’t yours.”

The pub noise moved around us, a river ignoring the men drowning. He stood, straightened his jacket like a doctor remembering how to be one, and left me in a booth with my hands suddenly empty.

I called Laura in the car. The dashboard cast the interior in submarine blue. “Tell me it isn’t true,” I said. Silence is a skill; Laura has honed it for courtrooms.

“How did you find out?” she asked. That was the admission. That was a hammer to the spike.

“So it’s his.”

A breath. A yes that wasn’t a word, just the shape of one in a throat that used to whisper promises to mine.

I don’t have the vocabulary for what that knowledge did to me. I can say it rearranged the furniture in my chest. The old ache over what she had done became a new thing, heavier, colder, permanent like a metal plate under the skin. I thought I had reached the bottom of this; there is always a lower place to stand.

In the evenings I returned to the evidence wall because grief makes you superstitious—touch the artifacts, orient the pictures, place the threads just so, and perhaps the universe will rewind one inch. The wall did not whisper back. It loomed. Photoshop of my life captured and pinned, it began to look less like a trial brief and more like a memorial.

I told myself it was over. I told myself Marcus was ruined. But I am not a man who rests easily when a machine hums wrong. I heard him still moving. His LinkedIn flashed a new job at a medical supply company hungry for respectable hires. His insurance paperwork listed Laura as a dependent though their relationship was not the kind that produces official dependencies. I made calls I won’t detail. I sent packets I won’t describe. A formal letter here; an anonymous complaint there. There is nothing quite so efficient as a process once it has been fed.

By the end of the month, Marcus did not have a new job. He had an appointment with a judge. The arrest didn’t make the news; it rarely does for men like him unless the story smells good to editors. The hospital didn’t blast it on a billboard. The moral arithmetic existed in the quiet: a man led out a side door; a badge clipped on a belt; a door closing on a career the way a book is shut when the last sentence isn’t good enough to continue.

Laura called me then. Not to curse me. To beg. She was in an apartment I didn’t know she’d found, boxes half-open around her like questions. “I need help,” she said. “The rent. The groceries. The baby—” She swallowed the word like a pill that would stick. “Please.”

“Have you called your other lovers?” I asked, and the ugliness of the sentence didn’t embarrass me like it would have had I said it a year earlier.

“You did this,” she said. Her voice didn’t even try the usual tricks. It was raw, a skinned knee against gravel. “Please.”

“You made the bed,” I said, and in my mouth it sounded like scripture when it was, in fact, a petty god’s little pronouncement. “Lie in it.”

I hung up. The kitchen camera caught me place the phone on the counter as if it might blow.

It didn’t bring peace—this chain of victories. It brought a varnish of calm over a rot I could now smell. Which is when I understood the deceit built into revenge: you think the next win will be the one that dispenses rest. It never is. The next win breeds the next need. And around the next curve there is always someone you didn’t plan on seeing in the mirror.

When Emily texted a photo of the newborn—not asking, just sending—I stared long enough for my eyes to blur the tiny face into watercolor. Swaddled in blue. Eyes closed. Mouth open in the sleep of a creature who knows nothing yet of names. Not mine. Not a grandson. Not anything I possessed. A stranger’s child that still somehow knotted itself around my history with a strength that surprised me. I zoomed in like proof would announce itself on the infant’s forehead. I found nothing but the heat of a living thing.

My heart did a strange, unwelcome thing: it softened. Not to Laura. Not to Marcus. To the tiny breathing proof that life, stubbornly, moves through wreckage and sets up home.

I put the phone down.

I went to the living room.

I stood beneath the little black eye in the baseboard and thought about turning it off.

I did not.

Part IV: The Courtroom in the Mirror (≈1,150 words)

I used to think courtrooms were rooms. You go in, testify, argue, lose or win, and go home. But once you’ve spent months cross-examining your own life with a camera for a judge, you carry the gavel with you. Every mirror is a bench. Every silence a gallery holding its breath.

Laura tried once more, and not out of manipulation. She arrived late on a Tuesday after the porch light had come on and the neighborhood settled into its television lull. She looked smaller than I remembered, like someone had ironed her edges. Her belly had begun to show under a sweater the color of moss. I didn’t invite her in; I didn’t leave her on the porch. We sat at the island like characters in a story that had run out of fresh dialogue.

“Emily hates me,” I said, to start somewhere surprising.

“She hates me too,” Laura said, surprising me back. “For different reasons.”

We sipped water because anything stronger would have typed up statements we couldn’t afford. She kept touching the hem of the sweater, steadying herself the way a person reaches for rails when the train shakes.

“I’ll never ask you to forgive me,” she said. “I wouldn’t know how to make that request honestly. I’m here because…” She looked up toward the crown molding, toward the small lens I had the decency to mount where it wouldn’t be obvious. For a second I thought she saw it. For a second I wanted her to. “I’m here,” she said, “because I loved the life we had. And because I set it on fire. And because I’m carrying a life anyway.”

“His,” I said, and the word stuck in my mouth like a splinter.

“Yes.”

“You could have told me,” I said.

“I could have told you a hundred things a hundred times I did not,” she said. It had the cadence of a confession rehearsed until it can be performed. “I don’t say this to wound, Jack, only to set down a piece of the truth: you stopped seeing me. You saw your job, your blueprints, your schedule. You took the things off my plate and stacked them neatly and called it love. I wanted to be wanted. Not just kept.”

There is nothing more infuriating than the reasons people give you for the wounds they caused. And there is nothing more honest, sometimes, than the sting of your own reflection inside those reasons. “I didn’t lie,” I said, and heard in my voice the smallness of a boy defending his homework.

“I know,” she said. “I did. And the lies grew legs.”

We sat in the hum of the refrigerator like parishioners under a boring homily. “I won’t destroy you further,” I said at last. “I thought pulling the right strings would stop the machine. It keeps running. I’m too tired to sit at the controls forever.”

“Thank you,” she said, and I almost laughed. Men like me want thanks when we stop throwing rocks we never should have picked up. “I don’t deserve it.”

“Probably not,” I said. “But the baby does.” The sentence felt like a plank I laid between us. Not a bridge; a temporary thing you could walk across without drowning.

She left with that plank in place. I watched the car drift down the street like a ghost that remembered the way home. I turned off the porch light because I didn’t want to be the house that made other houses sad.

That night the living room camera caught me doing something I hadn’t done in months: I stood in front of the evidence wall and took the threads down. Not all at once. That would have felt like theater. Thread by thread, color by color, sound of pins clattering into the ceramic bowl where keys used to fall. Blue for Marcus, red for Ray, green for Richard, gold for Patricia, black for Frank. I rolled them into small loops and put them in a drawer I reserve for things too important to throw away and too ugly to keep out.

I didn’t burn the pages. I wanted to. Flames purify in movies, and I have always been a sucker for a clean ending. But fire is irreversible, and for the first time in months, I knew I needed a way back from the ending I had spent so long rehearsing. I slid the files into a box, sealed it, labeled it with a date and the word caution, and shoved it under the workbench in the garage where we keep the holiday decorations that no longer match our taste.

The cameras saw all of this. They had their own kind of memory now: a silent record of a man disassembling his best argument. I hovered over the hub and thought about clicking disable. I didn’t. I did something stranger. I renamed the kitchen camera Kitchen—Repentance and the living room camera Living—Mercy. It was juvenile. It helped. Names always help.

The weeks that followed were not full of the peace the self-help books promise once you choose “a healthier path.” They were full of the grunt work of being a person again. I ate breakfast at the table instead of over the sink. I brought Emily’s boxes from the basement and sorted them into to keep and to give away piles, and I texted her before I threw out anything I wasn’t sure about. Sometimes she responded with a single word. Sometimes not at all. I didn’t punish her with follow-ups. I learned a new muscle: waiting without turning it into a martyrdom.

Marcus called once from a number that later bounced. He didn’t threaten this time. He didn’t taunt. He sounded exhausted, a man who had held up his life like a painting only to discover it was a mirror and the gallery was empty. “I won’t ask you for anything,” he said. “I want you to know I plan to do right by the child.”

“Do that,” I said. Three months before I would have laced the sentence with poison. It came out of me like water. “And do right by yourself. It isn’t too late to stop being the man who did this.”

“Is it too late for you?” he asked, no malice in it, just the curiosity that sometimes survives the courtroom.

“I don’t know,” I said. “Ask me in a year.”

I slept better after that call. I told no one about it.

One Friday I found myself outside the door of a therapist whose Yelp reviews used the word safe so many times I almost turned around. I am not a man who tells strangers the most humiliating stories of his life. I became one. She had the good sense to let me talk until the words ran out. When I finished she said something so simple it felt like an insult: “You built a courtroom because a relationship died, and the only way you know to honor the dead is to perform autopsies. What would it take to build a chapel instead?”

“I’m not religious,” I said.

“Good,” she said. “Then you’ll be less tempted to perform piety. Chapels are rooms where people set things down and sit in the quiet because the world outside is loud. That’s it. What would it look like for you to set the cameras down on a pew?”

I sat in the quiet of my head a moment. “It would look like turning them off,” I said. “But I’m afraid.”

“Of what?”

“That I’ll miss the moment everything collapses,” I said. “That I won’t be ready.”

She nodded. “Control is love’s decoy. You chased it like it was the thing you lost. It never was. Turn off the cameras when you’re ready, Jack. Not to make Laura good or yourself holy. Turn them off because you’d like to live in a house again instead of a case.”

I drove home under a sky that had finally decided on blue. I stood on the stool beneath the kitchen crown molding. I reached up and touched the little black lens with the tip of my finger. It felt warm. Alive. I remembered the night I told myself I forgot to tell her.

I told the camera, “Thank you,” which is not a sane thing, and then I clicked the hub and let the feed go black.

The house didn’t cheer. The angels didn’t sing. The stillness that followed felt like a throat unclenching.

The next morning I woke to the sound of quiet and realized it was, in fact, what quiet is supposed to sound like.

Clear Ending

I decided to clean the garage. If you want to know who a person has become, look at his garage. The old me had arranged sockets and wrenches as if any of them would ever be called to the front. The new me—or maybe just the exhausted me—pushed holiday tubs aside and made room for ordinary breathing.

The sealed box labeled caution sat where I had shoved it. I lifted it onto the workbench and cut the tape. The paper inside breathed up at me like a thing relieved to be seen. I did not read it. I did not burn it. I wrote a letter and set it on top.

To Whom I Become Next,

This is what you did when you thought precision could heal. This is what you did when you believed justice was something you could swing like a hammer without shattering your hands. If you are tempted to open this because rage is licking your feet again, call Emily instead. If she doesn’t pick up, leave a voicemail that says “I love you and I’m learning.” If she still doesn’t pick up, take a walk. If you still want to open this when you get back, come sit on the garage floor and ask yourself if the man who opens this box becomes someone your father would recognize.

Then decide.

I sealed it and wrote the date again and returned it under the bench. The cameras were off. No witness but the dust.

Emily texted me three days later. Coffee? The word alone felt like a door in a wall I had resigned myself to repainting every year for the rest of my life. We met at a place with chalkboard menus and baristas who look like they’ve forgiven people you keep on your list.

She sat in front of me and pushed her hair behind her ear like she did when she was seven and wanted to look older. “I’m mad at you,” she said, as if that were a kindness to begin with truth.

“I know,” I said.

“I’m mad at Mom,” she added, a smaller voice underneath the big one.

“I know,” I repeated.

She held her cup like a talisman. “He’s beautiful,” she said, and the he didn’t need a name. “He smells like milk and laundry, and he makes this little sound when he sleeps, like a tired bird.” Her eyes watered, and we both laughed at how miraculous it is that the body insists on water exactly when the heart is already drowning.

“I don’t know what to do with the part of me that wants to hold him and the part of me that wants to run,” she said.

“Hold him,” I said, and surprised myself with the steadiness of it. “Run later if you need. Or don’t. Babies don’t know what we did. That’s the point.”

She looked at me like I’d slipped a clue under the jail door. “Mom said you turned off the cameras,” she said.

I blinked. “She knows?”

“She came by to drop off some boxes I left,” Emily said. “She looked up at the ceiling like she was expecting to see something staring back. She said it was quiet.”

“It is,” I said.

“She also said she’s… she’s sorry, Dad.” The word felt unnatural coming from her mouth, a borrowed sweater. “I don’t know if you care.”

“I care,” I said. “I don’t know what to do with it. But I care.”

We let the silence stand between us like a neutral territory. We didn’t hug in the way movies think fathers and daughters will hug when they meet after a war. We held our coffee cups. We talked about the Red Sox bullpen and the fact that the city still can’t decide what to do with that derelict block on Boylston. Small things. Holy things, if you’ve been starving for them.

Weeks later, I saw Laura on the sidewalk outside the courthouse where I once waited for her beneath a stone eagle and brought her coffee so hot it burned her palm and she laughed and said, “I guess I deserve that.” She wasn’t in a suit that day. She wore a dress that announced pregnancy as a fact and not a drama. She didn’t see me. Or if she did, she performed not seeing me with a grace I had only ever half-admired.

I sat on a bench and watched people stream into justice and out again, verdicts tucked into folders like receipts for a life. I realized I had been walking into and out of court for a year without ever stepping on marble.

That night I wrote a letter I never thought I would write—honest and unadorned, no hooks or traps.

Laura,

I am not the man you married. I am not the man you left. I am someone standing on the road between, trying to figure out if moving forward means leaving pieces of both of them behind. I do not forgive you yet. I don’t know if I will. But I am learning to forgive the man who thought he could make peace by breaking things.

If you ever need help for the baby and you cannot find it anywhere else, call me. This is not a bargain. It is a sentence I want to be true about who I was when this is the story we tell ourselves about the hard year.

—Jack

I did not send it. I put it in the box under the workbench beside caution. Not every letter is for the person you write it to. Some are for the part of you that needs to hear yourself say the right thing before you can even imagine doing it.

On a Sunday, I drove to the coast because driving to the coast is the thing men in Massachusetts do when they don’t know the next sentence. The ocean had the good manners to be gray. I stood with my hands in my jacket pockets and tried, maybe for the first time since I opened the laptop that one late night, to pray. Not to the God my mother believed in or the God Laura dismissed as a crutch for people who needed rules. To anything listening. Or to the wind, which, to its credit, has carried harder sentences for dumber men than me.

“Make me useful,” I said. “Make me kind before I am right.”

On the way home, I stopped at a hardware store, which is the unsexy church for men like me. I bought sandpaper, cabinet pulls, and a little tin of wood polish that smelled like oranges. I polished the kitchen island until my arms hurt. I rearranged the living room books and found, pressed between two pages of Leaves of Grass, the note Laura had written me the first year we were married: Stop bringing me coffee so early. Start always coming home. I sat with that for a while and felt the tenderness and the stupidity, and then I put the note in a drawer and decided not to make a shrine.

There is an ending to every story about betrayal that wants to be true: the betrayer suffers; the betrayed rises; justice descends like a hawk. It’s tidy. It looks good on television. I had tried to live inside that ending. It had eaten me alive.

Here is the ending I got instead:

Emily invited me to a park where new parents cluster like migration geese. She put the baby in my arms. He wriggled, squinted, and opened his mouth like he might sing. He smelled like a future I didn’t have a claim on but could still breathe. I didn’t cry. I didn’t narrate a lesson I hoped she would hear. I held him, and the world narrowed not to justice or revenge or mercy, but to the weight of a person who had done nothing wrong.

Laura sat on a bench ten feet away, hands on her knees, watching with an expression that had not visited her face in a long time: unbeautified gratitude. She nodded once. I nodded back. It was not a reconciliation. It was a ceasefire we both wanted to extend as long as we could.

When the baby fussed, I handed him back, and my hands felt empty in a way that did not hurt. We walked to the parking lot and did not make promises. We said we’d text. We meant it. That is the small, clear miracle of a life you decide not to destroy further: you mean small things and you keep them.

That night, in a house that had finally returned to being a house, I took the stool again and reached up to the crown molding. I removed the little black lens from the kitchen, and I put it into the box with the others. I labeled the new box Tools I Don’t Need to Be the Man I Want to Be. I laughed at myself—self-help for engineers. I put the box on the highest shelf.

I slept. The ceiling above me ceased to be a map of oceans I was doomed to drift forever, and returned to being drywall needing a coat of paint come spring.

In the morning, sunlight came across the kitchen tile, and there was no red blink, no silent witness humming in the corner. I fried eggs. I sent Emily a picture of the ugly mug she’d made in ninth grade with the caption Still here. She sent a heart. Not forgiveness. A breadcrumb. Enough.

Months later, I found the caution box again. I read my letter on top and smiled at my melodrama. I left the seal unbroken. I put the box into the trunk of my car and drove to a storage unit on the edge of town, the kind you rent when you’re honest enough to admit you can’t be trusted with your past at arm’s length. I left it there. Not thrown away. Not at hand. Sometimes wisdom is as simple as distance plus a lock.

I never learned to like Marcus. I learned to live without him in my mouth every morning. Laura’s boy grew. Emily sent photos that arrived like postcards from a country I thought I might never visit. I went for long walks without narrating them to anyone.

If you ask me, now, which I would choose—forgiveness or destruction—I would tell you neither, not as ends. Forgiveness is not a binary you toggle. Destruction always looks simpler than it is. What I picked, when it mattered, was the small hard choice to be a person who puts down the hammer even when the nail still looks inviting.

Clear endings are a kind of mercy. They aren’t always fireworks. Sometimes they’re a Tuesday where the coffee is hot, the phone is quiet, the house hums like an old friend, and you realize you haven’t thought about the cameras in weeks. Sometimes they’re a park bench where you nod at a woman you once loved and, in a way that does not need anyone’s permission, still do—just not the way you used to.

I forgot to tell my wife about the hidden cameras I installed.

So I decided to just watch.

Watching taught me nothing I could live on.

Turning them off taught me how to begin again.

What We Keep, What We Return

The first snow came early that year, a quiet, dry fall that sifted through the morning like flour. I woke before the sun and stood at the window with a coffee I actually wanted to drink. The street hummed once with a plow a few blocks over, then fell still. Somewhere in the house, the heater clicked and began a low, patient conversation with the vents. The air felt gentled, as if the neighborhood had collectively decided to move softer for a while.

I put salt on the steps. I did not check a feed. There was none to check. Habit still pried at me sometimes—the phantom itch where a ring once sat, the pocket pat for a phone that stayed on the counter overnight. I let the itch be. It faded faster when I didn’t scratch.

Emily texted as the sky turned the pale blue of old milk. Can you watch him for two hours? Mom has a hearing. Marcus has to meet his PO. I’ve got a midterm to grade. She didn’t call him my son anymore in that possessive way new parents do at first. He had become him, a person in his own right, with needs that did not care which adult drew the short straw. I said yes before the second bubble pulsed.

They arrived bundled. Emily’s hair wore the slapdash knot of parenthood. The baby’s cheeks flamed from the cold, a tiny constellation of chapped dots around his nose. Laura hovered on the threshold longer than the cold warranted. She handed me a diaper bag as if it were fragile evidence and not a canvas satchel stuffed with overpreparedness: wipes, changes of clothes, a container of sliced bananas, an arsenal of pacifiers.

“Two hours,” Emily said. “Maybe two and a half. He’ll nap around nine. He likes white noise.” She stopped, caught herself, and laughed at the absurdity of notes for a grandfather who once kept a plant alive only by accident.

“I’ll figure it out,” I said.

Laura stood very still. She had always been still when she was afraid—her tell, if you knew where to look. “Thank you,” she said, again, the word less foreign on her mouth than it had been the first time. Not forgiveness, not request. Just thanks, set down on the welcome mat with the snow.

Two hours with a baby moves in half minutes and small catastrophes. A dropped pacifier is not a crisis until it is the one that slips mysteriously under a cabinet you didn’t know had a under. I put him down on a blanket and he kicked with a joy so complete it made me realize how much of my body had been clenched for how long. He made the tired-bird noise Emily had promised. He slept against my chest for twenty-three minutes that felt like a benediction. I watched the snow fall through the front window and felt a complicated gratitude that had nothing to do with desert or justice. This, I thought, is what a house is for: to hold a quiet life without asking it to perform.

He woke, and the diaper drama arrived. I had done this before, decades ago, with hands younger and a mind less haunted. The motions returned—the fold, the wipe, the curse when the wipe stuck to the cuff of my sleeve, the proud relief when the tabs stuck on the first try. He stared at me with velvet animal seriousness. “I know,” I told him. “We’re all doing our best with what we don’t deserve.”

When Emily returned, her eyes did the quick scan of a woman taking attendance: baby warm, bag accounted for, father’s face readable. She pronounced us both acceptable with a smile that started small and grew. Laura came in a step behind her, the cold biting roses into her cheeks. For a second it was twenty years earlier and nothing bad had ever been invented. The second passed. It left a residue I could live with.

“How was court?” I asked her, not to pry but because small talk is the scaffolding you build while the real architecture cures.

“Fine,” she said. “Routine. A motion to compel I knew I’d lose. Sometimes losing is the way through.” She looked surprised at her own sentence, as if truth had chosen her mouth by mistake and found it suitable.

We had fallen into a rhythm of brief, domestic exchanges: schedules, drop-offs, the dull necessary calendars of people who used to be married and are now something with fewer vowels. Once, before they left, Laura paused in the doorway where the crown molding meets the wall. Her hand rose, stopped in midair, as if the memory in her wrist wanted to touch the small plastic eye that no longer lived there. She lowered her hand. “It is quieter without it,” she said, not a question.

“It is,” I said.

“Do you miss it?” she asked, and we both knew she was asking something else too.

“Sometimes,” I said. “Then not at all. Mostly I miss what I thought it could do.”

“Which was?” she pressed, lawyer, always.

“Prove something that would save me,” I said. “Turns out proof isn’t mercy. It’s weight.”

She nodded. “I know a little about that.”

She left with a baby strapped to her chest, round head tucked under her chin like a spare heart. The snow had thickened. I brushed the steps again even though they did not need it, savoring the pointless generosity of it.

Therapy continued. I learned the dull heroism of naming the thing instead of performing around it. I said sentences no man in my family had ever said aloud: “I felt ashamed when she left,” “I was intoxicated by power,” “I want to be gentle more than I want to be right.” The therapist did not give me gold stars. She gave me silence at the correct depth and a question when I needed to see my foot before I could lift it.

In February, Marcus asked to meet. The text arrived through Emily—He wants to say something. I said I’d ask you. No pressure. The old me would have tasted the trap and gotten drunk on his own refusal. The current me considered the baby who would one day parse stories and look for villains he could hold in his palm like action figures. I said yes, and we chose a diner with cracked red booths and coffee that tasted like history.

He looked better. Not restored, not redeemed, but arranged. The patches on his jacket elbows were not decorative; they were the mending of a man who had rubbed through. We sat like men who did not trust their mouths. Finally he said, “I’m sorry.” The words were small and clean. He did not elaborate them to death. He did not set them on a platter of excuses. He let them be a seed.

“Thank you,” I said. It felt insufficient. It felt necessary.

“I can’t ask anything of you,” he added. “I have no standing. I want you to know I’m trying to be worth the child. I want you to know I understand the harm. Not just mine. Yours.”

“I don’t know what to do with that,” I said, because honesty had become the only currency I could spend without debt.

“Me neither,” he said. He looked out the window at the parking lot where snow had become gray lace. “Sometimes I think being a decent father is the only penance that isn’t about me.”

“Do that,” I said. “Decency multiplies. So does the other thing.”

He nodded. We paid separately. We did not shake hands. We walked into cold air that erased breath as it appeared. I watched him cross to his car with the gait of a man who chooses the next step on purpose. I did not bless him; I did not curse him. That was, in its small way, a miracle.

Spring came like a woman who refuses to announce herself—crocusses spearing brown lawns, the neighborhood teenagers practicing three-pointers in hoodies, the air softening in increments you notice only when you leave your jacket in the car and don’t have to run back for it. I worked on the house in unglamorous bursts. I patched a crack in the ceiling that had looked like a map of oceans on nights when I could not sleep. I repainted the living room a shade lighter than its old self and resisted the urge to narrate the metaphor. I bought a real white-noise machine for the guest room and left a pack-and-play set up, not as a shrine but as a gesture of what the house could hold.

One Saturday, I pulled the storage unit’s rolling door and stood in the dust strip of sunlight that always sneaks under no matter how tight you make the seal. The caution box sat where I had left it, flanked by a high school dresser and a crate of mismatched tiles from a bathroom renovation we never did. I touched the edge of the lid the way you touch a photograph of a younger self that you are grateful for and ashamed of. I did not open it. I slid it farther back. Not denial. Decluttering the altar.

On my way out, I carried a different box to the car: the one I had labeled Tools I Don’t Need to Be the Man I Want to Be. At home I unloaded the little cameras onto the workbench. They looked harmless, like toys that had lost their batteries. I cleaned them, coiled the cords, and drove them to a donation center. A young man in a vest took the box, scanned it with a gun that beeped, and said, “Thanks,” in the cheerful monotone of someone who has never yet needed mercy so badly he could smell it. I nodded. A ridiculous peace washed over me as I watched the box slide along a belt into the anonymous machine of second chances.

I did not tell Laura. I did not tell Emily. It was mine to do and mine to know.

By summer, the baby—he had acquired a name, and I had acquired the habit of saying it—could sit upright on a blanket and destroy a plastic tower with the joy of a god who has discovered entropy. Emily laughed more again, though she still wore the wariness of a person who has learned that everything you love is breakable and sometimes you break it yourself. We grilled in the backyard and did not talk about the thing unless it knocked on the fence. Laura came sometimes with potato salad you could set your watch by. She brought a lawn chair and set it at a polite angle. We learned a choreography of passing the child that did not require choreography. We were getting good at quiet competence.

Toward the end of August, Emily asked if I would like to take a day trip with them all to the coast. I said yes and did not feel the old reflex to examine her text for traps. The beach was the same indifferent gray it had been when I prayed into the wind. The baby ate sand with the conviction of a scholar. Marcus carried him to the edge of the water and let the foam lick his feet. Laura stood beside me with a towel on her shoulder like an exhausted flag. She said, “You look different,” and I said, “I am,” and we left it at that.

The drive home was sleepy and sun-warmed. In the passenger seat, Laura nodded off. In the rearview mirror, Emily tilted her head against the window and smiled at something I could not see. The baby’s head fell to one side, heavy with all the unearned grace a person gets to haul into this life. For a moment, the car felt like a chapel—everybody set down for a minute, no verdict expected.

“Make me useful,” I had asked the wind months ago. The usefulness I got was not grand. It was an extra set of hands when a diaper exploded in a Target bathroom. It was money slipped into a card with a cartoon elephant and no return address. It was being the house you can come to when the ones you were given are full of thorny furniture. It was turning on the porch light before people arrived so the first thing they saw was welcome.

On the first anniversary of the night I opened the laptop and discovered the door into hell, I didn’t mark the date with ceremony. I put coffee in the ugly mug. I read the paper. I walked to the corner and back and waved to the neighbor who had never once pulled his trash can to the curb on time. In the afternoon, I went to the storage unit one last time. I took the caution box out. I drove to the coastline and sat with it on the passenger seat like a companion I no longer feared.

I did not throw it in the ocean. I am done with theatrics. I opened it. I pulled out the files and the photos and the printed emails and the resignation I had orchestrated in a fit of righteousness. I turned them into a stack small enough to slide into a sealed envelope. I wrote on the outside Archive. I put it back. I added the letter I had written to the man I might become and the letter I had written to Laura and never sent. I closed the lid. I locked the unit. I drove home.

That evening, snow did not fall. The sky burned orange over the rooftops like a cheap painting. I set two plates on the table and then laughed at myself and put one back. I ate, washed the dishes, and sat in a chair that had known the weight of three different versions of me. The house hummed. Somewhere down the block, a child yelled something triumphant and untranslatable. I turned off the lights and went to bed.

Clear endings are not happy; they are clear. Here is mine, plain:

I forgot to tell my wife about the hidden cameras I installed, and then I decided to just watch. Watching made me a judge. Turning them off made me a man. I did not win in the way I imagined. I stopped losing in the way I had perfected. I am learning to keep what holds and return what harms. Most days, that is enough.

In the morning, there will be coffee and maybe a photo of a boy whose name makes my mouth curve when I say it. In the morning, there will be no lenses blinking behind the crown molding. In the morning, there will be a knock sometimes, and I will open the door. That is the end I can live in. That is the ending I choose

The Weight of Ordinary Days

Autumn has always been my season. Not because of pumpkin spice or football, though God knows New England clings to those like scripture, but because autumn admits the truth: things fall, and it can still be beautiful. The first crisp mornings felt like the year pressing reset on my lungs. The maple outside the bedroom window turned the exact shade of fire I had once carried in my chest. Only now, instead of burning me hollow, it lit the yard without asking for payment.

The house stayed quiet in a way that no longer unnerved me. For months after Laura left, silence had been an accusation. Every absent sound—the clack of her heels, the scrape of her chair, the sigh before she drifted to sleep—had haunted like a ghost. But silence, if you let it, teaches you new registers. I began to hear the hum of the refrigerator as steady company. The pipes knocking after a shower became a kind of applause for surviving the day. The absence of the cameras’ blinking lights turned into the presence of peace. It was ordinary, and ordinary was something I had thought I’d never want again. I was wrong. Ordinary was salvation.

I saw Emily more often. She still carried her caution like a purse she refused to set down, but there were days she laughed without realizing she’d let it slip from her grip. She’d drop the baby—toddler now, wobbling, proud of every unsteady step—into my arms and rattle off a list of instructions. I pretended to write them down. She knew I didn’t. We’d both smile, a silent treaty. Trust was being rebuilt not in speeches, but in errands, babysitting shifts, small text messages that ended with Thanks, Dad instead of Goodbye.

Marcus stayed at a distance. I didn’t ask for more. I heard through Emily that he was sober, employed, present. I didn’t need him in my circle, but I needed him not to collapse in hers. That, I realized, was enough. Some victories are small, but they don’t taste bitter.

Laura’s presence was more complicated. She came to birthdays, to cookouts, to Emily’s promotion ceremony at the high school where she now taught. We did not sit together. We did not pretend. But we existed in the same space without the air going rancid, and that was its own strange grace. Once, during a lull at a cookout, she drifted near and asked, “Are you… better?” Her eyes searched me for bitterness the way a lawyer searches a witness for cracks.

“Not better,” I said. “Different.”

She nodded. “That’s something.”

It was. I learned to stop chasing better like it was a finish line I’d sprint across one day to applause. Different was slower, harder, and more permanent. Different didn’t undo the past, but it stopped handing me the same knife every morning.

I worked on projects I had abandoned years ago. The shed got a new roof. The leaky faucet that had mocked me for a decade was silenced with a washer I bought for seventy-nine cents. I built a bookshelf in the guest room and filled it with novels I’d always meant to read. I surprised myself by actually reading them. Turns out, Whitman has more to say when you’re not reading him through the lens of your wife’s lover.

Nights changed too. I didn’t pace anymore. I didn’t drink myself into a stupor, either. Sometimes I sat on the porch and let the dusk fold over me. Sometimes I wrote in a notebook, not elaborate schemes or timelines, but fragments: coffee with Emily, he said my name today, maple fire in the yard. Proof, yes—but proof of life, not betrayal.

I went back to therapy even when I thought I didn’t need it. Especially then. My therapist had a way of pausing until my silence grew so loud I had to fill it with something true. One day she asked, “What would you do if the cameras had never been there? If you had never watched?” The question rattled me. Because the truth was ugly: I would have lived blind, and blind might have been easier. But then I thought of Emily’s face, the baby’s laugh, the wreckage we’d all had to walk through. “I’d still be a fool,” I said. “But maybe a happier one.”

“And which do you prefer?” she asked.

I didn’t answer right away. Finally I said, “The fool doesn’t learn. The wrecked man can.” She smiled like I’d finally turned in an assignment on time.

The cameras haunted me less, though I never stopped thinking about them entirely. I’d see them in store aisles, neat boxes promising security and peace of mind. I’d want to laugh and weep all at once. Security doesn’t come in a package. Peace of mind isn’t sold with batteries included. Those cameras had been both my curse and my salvation. They gave me proof, but proof burned me down to ash. They gave me knowledge, but knowledge stripped me of innocence. Would I do it again? I still don’t know. That’s the kind of answer therapy teaches you to live with: I don’t know can be survival.

The toddler grew. His first word wasn’t Mama or Dada. It was ball. Emily laughed until she cried, and even Laura managed a real smile. Marcus threw the ball across the yard, the boy toddled after it, and for a moment I let myself believe in something resembling family. Not the family I’d had. Not the family I thought I wanted. But a messy, fractured, stitched-together kind of family that limped forward anyway.

One evening, Emily called just to chat. No crisis, no request, just her voice filling my kitchen while I chopped onions. “You sound… lighter,” she said. “I think I like this version of you.”

“What version is that?” I asked.

“The one that isn’t watching all the time,” she said. “The one that’s here.”

Her words sat in me like warm bread. Simple. Sustaining. Enough.

That night, I walked into the garage and pulled down the last box—the one labeled Archive. I opened it slowly, like it might explode. The papers still lay inside, yellowing at the edges, evidence that had once felt like a sword. Now they felt like relics from a country I had no passport for anymore. I didn’t burn them. I didn’t keep them out. I resealed the box and slid it to the back. Some memories you don’t erase. You store them far enough away that they can’t bite unless you go looking.

I went to bed early, no beer, no pacing, just the steady weight of a quilt and the hum of a quiet house. For the first time in years, I dreamed not of betrayal or revenge, but of ordinary things: a walk in the park, a laugh over dinner, a child learning the word ball. When I woke, the dream didn’t sting. It stayed, like a gentle hand on my shoulder, reminding me that not all watching is suspicion. Sometimes it’s love.

And so, in the cool breath of autumn, in a house that no longer blinked with hidden eyes, I began to believe something radical: that destruction wasn’t the only ending. That maybe, just maybe, different could be enough.

Forgiveness Written in Small Letters

The first snow of the second winter came later than usual, a sloppy November storm that left more slush than wonder. I stood at the window again—same house, same street, same mug of coffee—but I wasn’t the same man. I’d learned to tell the difference. Once, this view had been the stage for suspicion. Now, it was just a street where kids dragged sleds and a neighbor cursed while scraping ice off his windshield. Ordinary. A word I used to sneer at. A word I now protected like treasure.

Emily stopped by more often, sometimes with the toddler, sometimes alone. She no longer carried anger in her jawline every time she looked at me. Instead, there was something like curiosity—like she was meeting a father she didn’t know she had. “You’re calmer,” she said once, after I cooked pasta and managed not to burn the sauce. “Even when you talk about Mom.”

I shrugged, stirring the pot. “Anger’s a furnace. You can’t live in one forever.”

She tilted her head. “You did, though.”

“Yeah,” I admitted. “And it nearly burned the whole house down.”

She nodded slowly, as if filing that answer away for a later day, maybe one when her own son disappointed her. That thought softened me. If my wreckage could be her cautionary tale, maybe it wasn’t wasted entirely.

Laura and I circled each other like planets locked in orbit, close enough to share gravity, far enough not to collide. She came to drop off the boy, sometimes stayed for coffee if Emily insisted. We never pretended to be friends, but we were no longer enemies. Once, she leaned against the kitchen counter—her old perch—and said, “I don’t expect forgiveness.”

“I don’t know if I have it to give,” I answered. The truth tasted clean.

She looked at the toddler stacking blocks on the floor. “Then maybe it’s not for me. Maybe it’s for him.”

That stuck in me for weeks. Forgiveness not as charity, not as surrender, but as inheritance. What would my grandson grow up hearing? That his grandfather had lived in fury like a man locked in a cage? Or that I had at least tried to choose a different story?

One evening, when the house hummed with its usual chorus—the fridge, the pipes, the faint whisper of the wind through window frames—I sat at the kitchen table with a pen and paper. Not a keyboard. Not a phone. Something slower, something that forced each word to walk across the page. I wrote a letter to Emily. Not for now, but for later.

Emily,

I spent years believing proof was power. That if I could show the world every receipt, every message, every betrayal, then I would win. But all I won was silence. What matters isn’t what I proved, but what I became. I don’t want you to carry my anger like a family heirloom. I want you to know that people can change, even broken people, even me.

Forgiveness isn’t a clean slate. It’s a choice to stop sharpening the blade. I’m learning it slowly. Sometimes I fail. But I want you, and him, to inherit something other than bitterness. You deserve that.

I folded it, sealed it, and tucked it in the same drawer where I’d once hidden evidence. Proof, still—but a different kind.

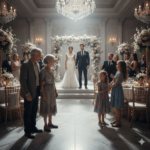

By spring, the boy was running. Not walking. Running, headlong into everything, laughter spilling out like it cost him nothing. One Sunday, Emily asked if I wanted to take him to the park. Laura came too, sitting on a bench while Marcus pushed the stroller. We must have looked like the strangest family tableau—fractured, rewoven, patched. People glanced at us, maybe wondering what story tied us together. I almost laughed. They’d never guess the truth.

The boy toddled toward the swings, fell, got up, fell again. He looked back at me each time as if to say, Still here? And each time, I nodded. Still here. It hit me then: that was forgiveness, in its smallest, truest form. Not erasing the fall. Not pretending it hadn’t hurt. Just saying, Still here.

Laura sat down beside me. “You’ve changed,” she said softly, not a compliment, not a question.

“So have you,” I said.

She looked at the child, then at me. “Maybe we both had to.”

I didn’t argue. For once, we didn’t need a verdict.

The storage unit rent came due in May. I unlocked the roll-up door, dust dancing in the light. The Archive box sat waiting like a dog that hadn’t been fed. I opened it one last time. The papers smelled faintly of mildew. The photographs, once so sharp they could slice, had faded. Proof doesn’t age well. It decays, loses its bite. I smiled at that.

I carried the box to the trunk. Not to burn it, not to store it again. To bury it. I drove to the coast, to the rocky stretch where the tide takes everything eventually. I didn’t fling it into the ocean like some dramatic ritual. I dug a shallow grave under a drift of dune grass, set the box inside, and covered it with sand. Proof belongs to the earth now, I thought. Let it rot.

On the drive home, I felt lighter than I had in years.

That summer, Emily hosted a barbecue. Friends, neighbors, family—all orbiting her new house with its peeling shutters and a yard big enough for the boy’s tricycle. Marcus manned the grill, Laura arranged salads, and I carried chairs from the garage. At some point, Emily raised a glass and said, “To family. However messy, however stitched together—we’re still here.”

We clinked plastic cups. Laura caught my eye across the yard. For the first time in years, there was no battle in her gaze. Just a truce. Maybe even respect.

After dusk, when the guests had thinned and the boy was asleep, Emily sat beside me on the porch steps. She handed me a beer. “You did destroy us, you know,” she said quietly.

“I know.”

“But you also… rebuilt something. Not what we had. Something else. I didn’t think you could.”

I swallowed, the beer suddenly heavy. “Neither did I.”

She leaned her head on my shoulder, just for a moment. “I forgive you, Dad.”

The words weren’t fireworks. They were softer, steadier. A candle lit in a dark room. Enough to see by.

Now, when people ask me if I’d forgive or destroy, I give an answer they don’t expect. “Both,” I say. “I destroyed what couldn’t stand. And then I forgave what was left.”

The cameras are gone. The wall of evidence is gone. What remains are mornings with coffee, afternoons with laughter, evenings with silence that feels like peace instead of punishment.

I forgot to tell my wife about the hidden cameras I installed. So I decided to just watch. Watching nearly ruined me. But turning them off—choosing different—saved what could still be saved.

Not everything. Not everyone. But enough.

And enough, I’ve learned, is a kind of miracle.

The Story I Leave Behind

The boy was four the first time he asked a question that knocked the air out of me.

We were sitting on the porch, his legs swinging against the steps, an ice cream cone dripping faster than he could lick. He turned those wide eyes toward me and said, “Grandpa, why don’t you live with Grandma?”

I froze. Children don’t ask gently—they ask straight, with the kind of blunt innocence that slices sharper than any lawyer’s cross-examination. I bought myself a second with a sip of coffee, then said, “Because sometimes grown-ups make mistakes. And sometimes those mistakes mean they can’t live in the same house anymore.”

He nodded, satisfied for now, already distracted by the mess melting down his hand. But the question stayed lodged in me like a stone. One day, he would want the real story. One day, he would hear versions from his mother, from Marcus, maybe even from Laura. What story would I leave him?

That night, I pulled out a leather-bound notebook I’d bought years ago and never used. The pages smelled faintly of dust and possibility. I began to write—not a confession, not a manifesto, but a record.

Your grandmother and I loved each other once. We built a home. We raised your mother. Then we broke it. Some of that was her choices. Some of it was mine. I can’t give you a perfect picture. I can only give you the truth as I saw it, and what I learned when the wreckage settled.

I didn’t detail every betrayal, every name, every receipt. He didn’t need that weight. What he needed, someday, was a lesson: that love can fail, that rage can consume, and that choosing different—choosing gentleness after destruction—isn’t weakness. It’s survival.

I wrote a little each week, slow as weathering stone. Stories of his mother’s childhood, the camping trips, the Christmas mornings, the small joys I wanted him to inherit. Interlaced were the cautions: how suspicion had turned me into a warden, how revenge had left me hollow, how forgiveness had been the only thing that made room for peace.

By spring, the notebook was half full. I sealed it in a drawer beside the letter to Emily. Legacy wasn’t a monument, I realized. It was breadcrumbs left for the people who come after, so they don’t get lost in the same woods.

A year later, the phone rang. Marcus. His voice was tight. “It’s Laura. She’s in the hospital. Nothing life-threatening. But… would you come?”

I surprised myself by saying yes.

When I walked into the room, Laura looked smaller than I’d ever seen her. No sharp suits, no courtroom armor—just a woman in a hospital gown, hair limp against the pillow. She looked at me with eyes that carried twenty-five years of history and whispered, “I didn’t think you’d come.”

“I almost didn’t,” I said honestly.

She gave a weak laugh. “Still honest. That hasn’t changed.”

We didn’t rehash the past. We didn’t need to. She asked about Emily, about the boy, about the house. I told her the maple tree out front had split in a storm, that I’d planted a new one beside it. “It’ll take years to grow,” I said.

“Maybe that’s the point,” she murmured.

When I left, she reached for my hand. Not in romance. Not in regret. Just human contact, two people who had once shared everything and now shared only memory. I squeezed once, gently, and let go.

Driving home, I realized something had shifted. Forgiveness hadn’t come like a lightning strike. It had come like a tide, slow, wearing down the jagged rocks until all that remained was something you could stand on.

That summer, Emily and I sat in her backyard while the boy chased fireflies with a jar. She looked at me over the rim of her glass and said, “Do you ever regret destroying them? Mom’s lovers, I mean. Marcus, Richard, Patricia—all of it?”

I thought hard. Once, I would have answered quickly, angrily. Now I measured the words.

“Yes,” I said. “And no. I regret what it made me. I regret what it cost you. But I don’t regret stopping them. Some needed stopping. The mistake was thinking it would heal me.”

She nodded slowly. “You’re different now.”

“Different is the best I can offer,” I said.

“That’s enough,” she whispered.

And in her voice, I heard something I hadn’t dared hope for: trust.

Years folded into each other. The boy grew into a child who asked sharper questions, who loved soccer, who once told me my pancakes were better than anyone’s. (They weren’t. But I didn’t correct him.) He came to my house for sleepovers, the guest room still carrying faint echoes of the cameras long gone. He slept soundly, unaware of the ghosts that had once haunted those walls.

One night, after he’d fallen asleep, I sat by the window and thought about the story I’d leave him. Not the details—he didn’t need those. But the essence: that his grandfather had been a man consumed by vengeance, and that he had chosen, finally, to put it down. That legacy mattered more than any courtroom victory.