Part One:

If you grew up anywhere near where I grew up—south side of San Antonio, three bus lines from the good grocery store—you learn what hot food means to a house. It’s not just dinner. It’s proof that somebody put you first. You also learn what the trash can sounds like when it swallows what someone else would’ve called a meal. That thud? It sticks.

My name is Evan Ward. I’m thirty-four, work IT for a school district, and make lists for fun because lists keep me from feeling like life is a stack of loose cables. My wife, Lila, is thirty-five, a nurse who can hold two thoughts and three crises at the same time. We’ve got two kids: Bram—twelve going on contractual lawyer—and Dalia, eight, who weaponizes dimples. Our house is a little cape on a quiet Ohio street with a maple tree that drops leaves like confetti and a kitchen that isn’t big enough for all the conversations it hears.

Before I tell you the thing I did, the thing that tilted the floor and sent me sliding, I need to explain the rule. It’s simple enough that it fits on a sticky note, and I’ve thought of it with a kind of pride, the way you admire a well-knotted shoelace.

If you don’t finish your dinner, that plate becomes your breakfast.

We didn’t invent it. We inherited it like a family recipe without exact measurements. Both of us grew up in houses where wasting food was a kind of blasphemy. Lila still remembers the lady on her block who handed out bags of government cheese and how her mom would slice it thin to make it last. I remember standing in line at the church pantry and watching a boy my age carry a box like it was a trophy.

When Bram was five and decided mac and cheese was only edible on Thursdays, we made the rule. It wasn’t about power; at least, that’s what I told myself. It was about not treating food like a mood. When he got older, we made it fairer: you serve yourself. You take too much, you see the rest in the morning, and you learn your own appetite the way you learn the limits on a trampoline. He grumbled, because he’s a child and grumbling is a language, but he adjusted. The leftovers showed up less and less like bad mail. It worked.

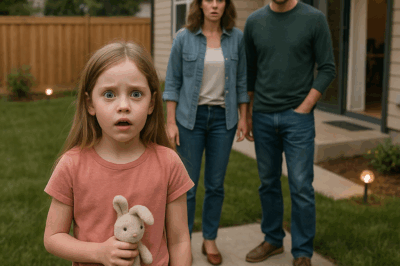

Then Dalia turned eight and found her opinions like spare change in the couch cushions. She started pushing away anything “green or mushy.” “Mushy” covered about eighty percent of the food pyramid. One night she cried because saffron made her rice look “sick.” We reinstated the rule, out loud, for both kids. She needed boundaries; Bram needed to know the rules didn’t evaporate just because he was tall.

Friday night, Lila roasted a chicken the way she does when the week was long and needed a finale. Potatoes with rosemary, green beans that snap. Bram loves that dinner. He loaded his plate like he was carbo-loading for a marathon he forgot to register for. I raised an eyebrow, and he shrugged, sheepish. Halfway through, he put his fork down.

“I overshot,” he said.

“The rule?” I asked.

He nodded. “I know.”

It wasn’t dramatic. No tears. No speeches. He wrapped the plate in foil himself and slid it into the fridge, next to juice boxes and the jar of pickles Lila pretends are only for Bloody Marys.

Timing, it turns out, is a prankster.

Saturday morning was a thing we hadn’t had in too long: a proper family breakfast with company. Lila’s folks live two hours away and we don’t see them much because work eats weekends and pandemic muscle memory still whispers be careful. When we do get together, it feels like a holiday nobody had to buy tickets for.

Lila was up before sunrise proofing dough like a baker on TV. She made her French toast—the one soaked overnight so it turns custard in the skillet—and a tray of croissants so flaky they shed like cats, scrambled eggs with chives from the pot by the back steps, fruit salad that made the kitchen smell like the inside of summer. Bram came down the stairs sniffing like a cartoon character following a scent thread.

He grinned when he saw the table. Then his eyes found the other plate—the foil-covered one I’d set to the side, reheated, ready.

I saw the grin fall out of his face like somebody turned off a light.

He sat. He pulled the plate to him. He didn’t argue. That, to me, used to mean we were winning.

“Morning, kiddo,” Lila’s mom sang, kissing the top of his head. “You okay?”

“I’m fine,” Bram said, the words so polite they sounded manufactured.

He forked chicken and potato and green beans, mechanically, the way you scrape ice from a windshield. Everyone else reached for platters, buttered croissants, passed syrup, laughed at Dalia’s story about her teacher’s shoes (leopard print, drama). Bram kept his eyes on his plate. The French toast might as well have been in a magazine.

If you’ve never sat at a table and watched your kid be somewhere else, I don’t recommend it. He wasn’t sulking. He wasn’t angry. He was absent in a way that made my ribs feel hollow.

Lila’s dad asked for the pepper. Lila’s mom noticed Bram’s plate and tilted her head. “Honey, you don’t want any of this?” She gestured to the parade of warm things.

“He’s finishing last night first,” Dalia announced, loud and clear, like a new anchor breaking a story. “Because he didn’t finish his dinner.”

Silence doesn’t always crash. Sometimes it creeps. Chairs kept creaking. Forks still tapped. But the noise went far away. Lila’s mom put down her fork.

“You made him eat leftovers,” she said, not a question.

“They’re reheated,” I said, and the pedantry tasted like pennies the second it left my mouth. “We have a rule. To avoid waste.”

Her dad’s jaw did that thing where it slides. He’s a gentle man until he isn’t. “So you’re… punishing him at the table? In front of everyone?”

“It’s not a punishment,” I said, the way people say it’s not about the money. “It’s a consequence. He served himself more than he could eat. He knows the rule. He agreed.”

“A consequence and a punishment are synonyms, Evan,” Lila’s sister, Mira, said, too quick—she teaches ninth-grade English and keeps lightning in her back pocket. “And the timing—my God.” She looked at the platter, then at Bram’s bent head. “This is how kids learn to be ashamed of hunger.”

“He’s not hungry. He’s full.” I wanted to sound reasonable. I sounded defensive. “If we make exceptions because we have company, Dalia will clock it, and then every time we ask her to finish anything she’ll say, ‘What about when Grandpa was here?’ We’ve done that dance.”

Across the table, Dalia blinked at hearing her name like it had been pulled into evidence.

Lila’s mom’s voice softened, which is always more dangerous than when it sharpens. “Honey, I know you’re trying to teach values. I get that. But you’re teaching them, too, that food is something they have to get through to earn something better. That’s… not the lesson you think.”

My chest tightened. “With respect, this has worked,” I said. “Bram eats a wide range, Dalia does too. We don’t throw food away. We’re not—” I tried to find a word that wasn’t judgey and found none—“we’re not cooking chicken nuggets for ten years.”

Mira’s chair scraped. “Okay, now you’re being smug.”

Lila gave me that look—the one that says you are not on a podcast arguing with your imaginary audience; you are in our kitchen with my parents and our children.

“Let’s just… eat,” she said. Her smile was brittle. “We can talk later.”

But something had already broken under the table. The kind of crack you don’t hear until you step and feel the floor give a little.

Bram finished his plate. He pushed it a measured inch away and reached for his juice. He didn’t touch a croissant. He didn’t touch the French toast. His body said I’m full. His face said something else. I told myself I was imagining it because I wanted to stay righteous. That’s a hell of a sentence to admit out loud.

After breakfast, Lila’s mom took her outside. The screen door did the thing it does that you only hear when you’re about to be scolded. I stacked plates and listened to voices float through the window—low, urgent, the music of family disagreement. Bram went upstairs without being asked. Dalia followed him halfway up, then doubled back when she realized there were still strawberries.

Lila came back in with eyes that weren’t wet but could be. She doesn’t cry when she’s angry. She parks it until later.

“Mom thinks we humiliated him,” she said. She didn’t add and she’s not entirely wrong because she didn’t have to. “Dad said if we want to teach responsibility, we can do it without making him finish last night in front of them.” She rubbed her forehead like it had words written on it and she was trying to smudge them away. “Mira said eating disorders like company.”

“She also says comic books are literature,” I said, which was an attempt at levity and a bad choice.

“Evan.”

I put down the dish in my hand. “We have a rule,” I said, quieter now, not because I was conceding but because I remembered the kids were upstairs. “If we bend it because the camera’s on, what are we teaching? That consequences only matter until company arrives?”

“I’m saying we could have asked him to finish it at lunch,” she said. “Same consequence. Not the same… spectacle.”

I opened my mouth to answer and realized I had none I liked.

Later, when the house was quiet in that post-company way that feels like a hangover, I knocked on Bram’s door. His room smelled like boy—socks and books and something lemon because Lila sneaks a reed diffuser in there and he pretends not to notice. He was assembling a Lego spaceship he’s been building in an on-again, off-again relationship since Christmas.

“Can we talk?” I asked.

He shrugged. He didn’t look up.

“Are you… mad?” I said, and wanted to take the word back and replace it with something that didn’t sound like I was daring him.

He shook his head. “No.”

“Embarrassed?”

Another shrug. The universal pre-teen Parliamentarian’s gesture for I move that we adjourn.

“It’s okay to say if you are.”

He put a piece in place with more precision than feelings. “It’s fine, Dad.”

I hate that fine is the worst word in my house and the only one I had taught him to reach for.

“Okay,” I said, and I left, because sometimes you leave and that’s the right thing. Sometimes you leave and it’s the coward’s move and you don’t know which it is until later.

I did not know it was the wrong one until my phone started to buzz that night like it had been connected to a live wire.

The family chat—Lila’s side—is usually recipes and pictures of nieces and aunts who call themselves aunties even if they’re not related. That night, it was a tribunal. Lila’s mom sent a paragraph about cruelty and memory. Lila’s dad wrote a thing about respect and shame. Mira sent links. Not one gentle comment. Not a single oh come on it’s not that bad to soften the blow. I read every word the way you watch a wave you think might be taller than the house.

I typed out: We weren’t punishing him. We were being consistent.

I deleted it. It looked worse on the screen than in my head.

Then because I am a man who believes in order, I made a chart. I opened Notes and titled it Zero Waste Week. Gold stars if both kids finish everything they serve themselves. Five days in a row equals a weekend treat. Structure. Positive reinforcement. The opposite of shame. It felt like a fix.

When I showed Lila, she stared at the screen and then at me.

“This is still about making food a moral report card,” she said. “We can teach without turning plates into a personality test.”

“It’s a game,” I said. “Kids like games.”

“Bram’s twelve, not three.”

“He likes Mario Kart.”

“Mario Kart doesn’t ask him to swallow his feelings.”

We stood there in the kitchen where everything had started and felt the map redraw itself under our feet. I didn’t know yet how much I’d lose if I insisted on being right.

The next afternoon, Dalia left a third of her pasta untouched and slid off her chair with the slippery speed of escape.

“Hey, kiddo,” I said, voice light. “You saw what happened with Bram. You don’t want to see this again at breakfast, do you?”

She turned back. My words did what I wanted: they bent her. She ate. She glared at the bowl like it had wronged her. I felt that small hot flare of victory that tells the truth about a rule: it feels good when it works like a lever.

An hour later I felt sick about it. Because I had used my son’s quiet compliance as a stick to poke his sister into line.

By Sunday night, the texts from Lila’s family had slowed, replaced by the quiet that follows a fight you don’t want to keep having. Lila’s mom sent one more message—shorter, kinder, no less sharp: Read the room next time. Let him have the French toast. Deal with the lesson later. Memories matter.

I showed Bram the chart anyway. He nodded because nodding is easier than negotiating with a parent who thinks he’s protecting a value. He went to bed early. Dalia asked if the stars would be shiny or just drawn. I said shiny. Lila went upstairs without a word.

I loaded the dishwasher and stood with my hands on the counter until the numbness in my palms matched the numbness in my ribs. I could have gone up to Bram and said, Hey, I think I messed up. I could have told Lila’s mom, You’re right about the timing. I could have apologized, not because I was abandoning the idea that food shouldn’t be wasted, but because I had made my son swallow a lesson at a table where he should have been allowed to taste joy.

Instead, I set my jaw around the word consistent like it was a life raft.

That word tastes different now.

Part Two:

By Monday morning the quiet in our house had the texture of old wool—scratchy, heavy, carrying a smell you can’t quite name. I dropped Bram at middle school and Dalia at elementary, then drove the long way to work because I couldn’t look the maple in our yard in the eye. Every traffic light felt like a sermon. On my second detour around the block, I called Lila.

“How mad are we at each other?” I said.

She sighed softly. “I’m not mad. I’m… disappointed, and that’s a worse word.”

“In me,” I said.

“In the choice,” she said, careful as a nurse changing a dressing. “And in myself for not stopping it when I could have.”

I wanted to argue with her half of that, but I was already busy arguing with my own.

At lunch I did something I haven’t done since Bram was born and sleep became a myth: I walked. No podcast, no inbox triage on my phone, just the kind of walking where the city fills your head with other people’s noise until your own shuts up. It didn’t work. My mind kept replaying Bram’s face when the foil came off his plate—how the light just went out.

By three I had broken my personal rule about not posting personal things online. I wrote up what happened and dropped it into a parenting forum under a burner username because I wanted a stranger to tell me I wasn’t a monster. I told myself I was crowdsourcing perspective. Lila would call it fishing. Within minutes the replies came in like a storm.

YTA. Hard YTA. Rigidness is not a virtue when it hurts your kid. Food doesn’t need morality attached to it. You wasted a memory.

One comment stuck like a burr: Congrats, you didn’t waste food, but you wasted a memory. I closed my laptop and felt the sentence sit in my chest like a shoe I’d swallowed wrong.

The in-law group chat went from tribunal to cold war. Mira, who has never met a resource she didn’t want to send, texted a link about teaching kids to listen to hunger cues and a second about shame around food—bullet points and infographics and a quote from someone with three initials after her name. Lila’s mom sent a single photo: Bram at seven holding a mixing bowl for her while she stirred batter, his face lit like the world was a kitchen with enough for everyone. No caption. Didn’t need one.

Victor, my father-in-law, called that evening. He is not a man of long calls. “I know you were trying to do right,” he said, voice low gravel. “But you did wrong. Fix it.”

“How?” I asked, and hated how small it sounded.

He let the silence do work. “Start with ‘I’m sorry,’ on purpose and not as a speed bump.”

After dinner Dalia pushed away her broccoli with theatrical disgust, then glanced at me out of the corner of her eye like a gambler checking if the dealer saw the card. I opened my mouth to say easy words—You saw what happened to Bram—and stopped myself like my tongue had hit a tripwire.

“Sweetheart,” I tried instead, “how about two trees for tonight?” We count broccoli in trees when we remember to be kind. She made a show of suffering and ate four, because eight-year-olds are born litigators and will always make you go one better to prove you meant it.

Bram excused himself without dessert. I heard Lego clink upstairs and realized the sound actually calms me because it means his hands still know how to build, even if I’d made the rest of him want to fold. I knocked.

“Come in.”

He was sprawled on the floor, spaceship guts everywhere, instructions propped against a shoe. He didn’t look up.

“Can we talk?” I asked.

“Sure.”

I sat cross-legged like I was at a school assembly. “I owe you an apology.” The words felt strange in my mouth, like reading lines in a play you didn’t think you’d be cast in. “Saturday morning, I made the wrong call.”

He didn’t move. But his hands stopped.

“I put the rule ahead of you,” I said. “You didn’t do anything wrong except misjudge your hunger. The timing was special. I should’ve said finish it at lunch. I didn’t. I’m sorry.”

His shoulders rose and fell. “Okay,” he said.

“Okay like you accept the apology,” I said gently, “or okay like you want this conversation to be over?”

He finally looked up. He has Lila’s eyes when they’re quiet, which is to say they hold more than they spill. “Both,” he admitted.

“Tell me anyway.”

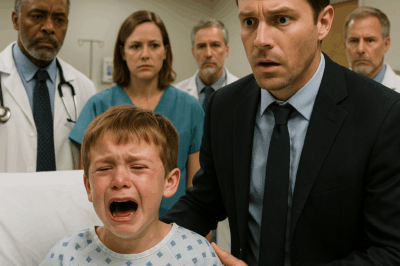

He propped his chin on his fist in perfect imitation of a thinking emoji, which made me want to laugh and then cry. “When I saw the French toast,” he said, “I was really happy. Then I saw the plate and I felt like I’d been stupid. Like I ruined it. Like I didn’t deserve the good stuff. And when everyone looked at me, I felt like my chair got taller. Like everyone could see me the most.” He looked back down at the Lego wing. “I didn’t want to cry. I didn’t. But I wanted to.”

Somewhere in the house, a pipe ticked. My throat did the same.

“I didn’t think you were stupid,” I said. “I think I made you feel that way anyway.”

He shrugged, a smaller one this time. “I know we don’t waste food. I get it. But sometimes I’m hungrier than I think. Or less. And I don’t know until later. And it’s weird to eat cold chicken at breakfast.” He grimaced. “Even reheated.”

I swallowed. “Fair.”

“And… when I was done, I was full. But I still wanted French toast. That was the worst part. Wanting something and being too full for it. It made me feel… dumb.” He searched for a better word and then, being twelve, shook his head and let dumb stand.

“You weren’t dumb,” I said. “I was.”

He made a face. “You’re not dumb, Dad.”

“Then I was unkind,” I said. “Which is worse.”

We sat without filling the air. The spaceship wing clicked into place with a satisfying sound that felt like grace.

“I’m making French toast on Saturday,” I said. “Like a do-over. And no leftovers anywhere in the county.”

He smiled without looking at me, the way he does when he wants to accept without giving me the full victory. “Okay.”

“And,” I added, offering him the steering wheel because I should have before, “we’re pausing the leftovers rule. The chart, too.”

He glanced at me, surprised. “The gold star thing?” He’d clocked it without me even showing him. Of course he had.

“Gone,” I said. “We’ll figure something better out together. Ways to not waste food that don’t make anyone feel like food is… a test.”

He looked relieved in a way that made me realize how heavy invisible things can be. “Can we just do smaller scoops?” he asked. “Like, you can always get more.”

“Basic portion theory,” I said. “Revolutionary.”

He cracked a smile. “Can I still have seconds when it’s lasagna?”

“Legally required,” I said. Then, quieter: “Thanks for telling me, buddy.”

He nodded and went back to the galaxy under his hands. I sat a minute longer and let the Lego clicks read as forgiveness.

Downstairs, Lila was reading on the couch with her feet up and her face doing that thing where she’s in two worlds—one on the page and one solving a problem nobody has articulated out loud yet. I told her about my talk with Bram. I told her about the do-over, the pause, the chart going into the trash.

She put her book down and rubbed her eyes. “Thank you,” she said simply. “I know it’s not easy to take apart a rule that made you feel like a good dad.”

“I still want to be a good dad,” I said. “I just don’t want to be a rigid one.”

She patted the cushion. I sat. “We could use help,” she said, cautious. “Not because we’re failing. Because… we’re in the middle of our own stuff. You grew up hearing the trash can thud. I grew up with a mother who rationed guilt with groceries. We both brought those ghosts to the table. Maybe it’s time to invite someone living.”

“A therapist?” I asked, too fast, defensive by reflex.

“Maybe a feeding specialist,” she said. “Pediatrician has names. Somebody who can help us build new habits. The internet is loud. I’d like a person with a door.”

“I posted online,” I admitted. “I got my teeth kicked in.”

She snorted softly. “Sometimes they deserve to. Sometimes they don’t have your kitchen in their heads. We do. Let’s give ourselves a chance to learn without a jury.”

I nodded. Relief wired into embarrassment, a combination I’ve come to recognize as growth’s first cousin.

My phone buzzed. A text from Mira: I was harsh. Sorry. I love you both. Here’s a thing called the Division of Responsibility. Don’t roll your eyes; it’s not a cult. It just says parents decide the what/when/where and kids decide whether and how much. It’s helped my ninth-graders’ parents when they ask why their kids only eat Takis.

I copied the link and didn’t read it yet. I wasn’t ready for a new doctrine. I was ready to stop worshiping the old one.

Bram came downstairs in pajamas, hair sticking up like an idea. “Mom?” he asked. “Can I have toast?”

“You just brushed,” I said, on pure autopilot.

He shrugged. “It’s just toast.”

I looked at Lila. She looked at me. She made a face: your call.

“Sure,” I said. “One piece.”

He popped a slice in and watched the coils glow as if they were sunrise. When it popped, he took a bite and said, offhand, “Grandma texted me.”

My stomach did a flip. “What’d she say?”

He shrugged with a little smile. “She sent that picture of me with the mixing bowl. And she said, ‘You always deserve French toast.’”

I felt my eyes sting and looked at the ceiling like it had suddenly become fascinating.

On Wednesday, Lila’s parents came over with a pie and the kind of careful conversation people use when they want to fight but love you too much to do it in the open. We stood around the kitchen island, that strange American altar, and did our own division of responsibility: they said their piece, we said ours, nobody raised voices, everybody raised their palms in surrender at least once.

“Thank you for hearing us,” Lila’s mom said at the door, hand on my forearm in that mother-in-law way that tells you she is not your mother and somehow your mother more than most. “Thank you for not digging in.”

“Thank you for caring enough to dig at me,” I said, and she smiled like I’d made a joke that wasn’t quite one.

Saturday came like a calendar apology. I woke before anyone, mixed custard with vanilla and cinnamon, and soaked thick slices of bread until they went heavy with promise. I cooked them slow, the way you have to when you want the middle to be patient enough to become soft. The house filled with a smell I wish I could rent out by the hour to people who believe life is only deadlines.

Bram shuffled in wearing the T-shirt with the pixelated dragon, hair a chaos map. He blinked at the pan like it was a magic trick. “For me?” he asked, trying to sound uninvested and failing gloriously.

“For us,” I said. “But also for you.”

He sat. I put two slices on his plate, a handful of berries, a little river of syrup. Dalia wandered in and declared this was unfair and then, when presented with her own plate, declared it was justice. Lila kissed my cheek and whispered, “Good job,” like she was signing a permission slip for my heart.

We ate. Bram took a bite and closed his eyes. He didn’t say anything. He didn’t have to. Some moments come with their own captions.

After, I took the Zero Waste Week chart off the fridge. I peeled it slow so the tape wouldn’t leave a mark, folded it twice, and put it in the trash. Not because the idea of wasting less had died, but because the way I’d tried to save it had. I felt oddly light standing there with empty hands.

That night, after the kids brushed for real and not the kind of brush where they just lick the toothbrush to win, Lila sat beside me on the couch with her laptop and said, “I made us an appointment.” Pediatric dietitian. Two weeks. It felt like getting directions to a place you didn’t know you were allowed to ask about.

Before bed, I texted Victor: I apologized. We’re changing it. Thanks for kicking me in the shins.

He replied with a thumbs-up and a photo of a fishing lure. I don’t speak that dialect, but I understood.

In the dark, I thought about my own childhood again, but not the trash can this time. I remembered my mother standing at the stove, scraping the crisp bits from the bottom of a pan and calling them the good part, putting them on my plate like a crown. Love is a weird economy. I had tried to balance one ledger by writing red ink into another.

I rolled over and said to the dark, “I want to do this better.”

Lila’s hand found mine. “We will,” she said, like a promise to both of us.

Down the hall, Bram snored very softly, the way he used to when he was little and sleep was a full-time job. I listened until I fell asleep to the sound of my son breathing like a house that knows it is held.

Part Three:

Kids test fences. That’s their job. You set a line, and they lean against it with all their little weight until it wobbles or holds. After I pulled the Zero Waste chart off the fridge and declared a moratorium on the leftovers rule, Dalia immediately decided it was her turn to be a crash test dummy.

It started small. A half-eaten hotdog at lunch. A yogurt cup abandoned after two bites because “it tastes like sadness.” I told her fine, but next time she should take less. She squinted at me like a cat trying to decide whether to claw the couch. The next day, she dumped untouched broccoli into the trash while humming loudly to cover the sound.

“Dolly,” I said, using her baby nickname because I was trying to stay soft, “we don’t throw away food just because it looked at us funny.”

She crossed her arms. “But you said no more leftover rule.”

I knelt to her level. “Right. No more forcing. But no more wasting on purpose either. If you don’t want a lot, take a little. You can always get seconds.”

She pouted, then brightened. “So if I take tiny scoops, I can have five dinners?”

Lila, watching from the sink, covered her mouth to hide a laugh. I sighed. “Within reason. You’re clever, but you’re not getting out of broccoli forever.”

Saturday, we drove down to Lila’s parents’ house for her niece’s birthday—seven years old, a bouncy castle in the yard, frosting thick enough to plaster a wall. Family gatherings are minefields even when everyone loves each other. This one had an extra layer: our new food détente versus the cousins’ free-for-all.

The birthday girl’s brother ate nothing but nuggets and plain pasta. His plate looked like beige real estate. When Bram sat down with fruit salad and pulled pork, Mira leaned over. “See? He eats like a grown man. Credit where it’s due.”

I braced for the second half. Mira doesn’t deal in compliments without clauses.

“But,” she added, “it’s because he was afraid not to. You trained him like a dog.”

Bram, twelve and sharper than I give him credit for, looked up. “Actually,” he said, “I eat it because I like it. And because Mom says taste buds are like muscles. If you don’t use them, they get weak.”

Lila hid a smile behind her drink. Mira blinked. “Well… okay then.”

Victor, bless him, cut in. “Leave the boy alone. He’s doing fine.” Then he winked at Bram, who ducked his head, pleased.

The real test came during cake. Bram took a slice, ate half, then set down his fork. Dalia licked off the frosting and abandoned the cake altogether. The old me would’ve jumped in: Finish it or breakfast. The new me took a breath.

“Done?” I asked.

“Yeah,” Bram said. “I’m full.”

“Okay.” I let it go. He smiled faintly, surprised.

Dalia slid her plate toward me, frosting-smeared sponge untouched. “Want it, Daddy?”

I hesitated. Victor was watching. Mira was watching. Lila squeezed my hand under the table.

“No thanks,” I said. “But next time, maybe just frosting for you, huh?”

Her eyes lit up. “Really?”

“Really. Saves the cake for people who like cake.”

Mira opened her mouth—probably to accuse me of giving Dalia cavities for sport—but Mom cut her off. “That’s called compromise,” she said. “And it looks pretty healthy to me.”

Later, while kids screamed in the bounce house, Bram sat with his grandparents on the porch. I lingered nearby, pretending to scroll my phone, but really listening.

Grandma asked gently, “You doing okay, kiddo? After last week?”

Bram fiddled with his soda can tab. “Yeah. Dad said sorry. He’s making changes.”

Grandpa nodded. “That’s good. Not all dads can say sorry.”

Bram looked out at the lawn. “It was embarrassing, though. Like… I wanted the French toast so bad. But I didn’t want to make a scene. So I just ate.” He shrugged. “But Dad listened later. So I guess it’s okay.”

My throat tightened. I almost walked away, but then Bram added, “I like rules. They make sense. But I like when Dad bends them sometimes. It feels… fair.”

Fair. That was the word I should’ve been chasing all along. Not consistency. Not waste. Fairness.

On the drive home, Lila glanced at me while the kids dozed in the back. “You heard, didn’t you?”

“Yeah,” I admitted. “He wants fairness, not rigidity.”

She squeezed my hand on the gearshift. “So do I.”

Sunday dinner, we tried something new. We put serving bowls in the center of the table and let the kids plate their own in stages. Bram served a modest portion, ate it, then took seconds. Dalia scooped one green bean, declared it disgusting, then negotiated for three strawberries instead.

It was chaos. It was messy. But it felt alive.

When Bram finished, he leaned back, satisfied. “This is better,” he said simply. “Not scary. Just food.”

And just like that, I realized my son had given me the blueprint I’d been searching for.

Part Four:

The new system was fragile, like a paper airplane you don’t quite trust to fly. Inside our house, it worked. Bram ate until he was full, then stopped, no guilt. Dalia experimented with spoonfuls and didn’t have to choke down what she hated. Lila and I felt lighter at the table. But outside the house, the ghosts of that French toast morning still hovered.

It didn’t take long before they showed up again.

Two weeks later we drove to a cousin’s birthday party at Chuck E. Cheese. Chaos incarnate: shrieking toddlers, blaring arcade machines, pizza that tasted like cardboard but disappeared anyway. Bram grabbed two slices, ate one and a half, then pushed his plate back. Dalia ate crusts only, then demanded ice cream.

I said yes to Bram—no big deal. I said, “Okay, but one scoop” to Dalia. And that’s when Mira pounced.

“So the leftover rule is dead now?” she asked, slicing her words as sharp as her pizza cutter.

“Dead and buried,” I said evenly. “We’re trying something different.”

Her eyebrows arched. “Convenient. When it embarrassed you, suddenly the sacred rule doesn’t matter.”

Victor, sitting nearby, cleared his throat like thunder. “Leave it, Mira.”

But she didn’t. “You’re teaching them to waste food. What happened to accountability?”

I felt the old defensiveness flare—the urge to recite why the rule worked, why kids need consistency, why culture shaped me. But then I saw Bram’s face. He’d gone still, shoulders up like a turtle in its shell. He thought I’d let Mira decide the narrative again.

Not this time.

“You’re right about accountability,” I said. “But accountability isn’t shame. I crossed that line with Bram. I made him feel small in front of family for an honest mistake. That’s not accountability. That’s humiliation. I won’t do it again.”

The table went quiet. Even the animatronic mouse seemed to pause mid-song.

Lila slid her hand onto mine. “We’re trying to teach moderation without punishment,” she added. “The kids are learning to serve themselves smaller amounts. To try things. To stop when they’re full. It’s healthier than forcing leftovers as a consequence.”

Mira snorted. “Sounds soft.”

“Maybe it is,” I said, surprising myself with how calm I felt. “But it’s also fair. And Bram deserves fair more than he deserves rigid rules. If that makes me soft, I’ll take it.”

After that, no one spoke for a moment. Then Victor chuckled, low and approving. “That’s called growth,” he said. “Some people learn it slower than others.”

Mira flushed, but she didn’t argue again. She stabbed her pizza crust instead.

Later, in the car, Bram whispered from the back seat, “Thanks, Dad.”

“For what?” I asked.

“For saying it out loud. About the French toast. I thought you’d never admit it.”

The words hit me harder than I expected. “I should’ve sooner,” I said. “I was wrong. And I don’t want you carrying that around like it was your fault.”

He smiled faintly. “Okay. Then I won’t.”

At home, Lila poured us each a glass of wine after the kids went upstairs. We sat in the quiet kitchen, the hum of the fridge the only sound.

“You know,” she said, “you finally said what I’d been hoping you would. Not just to me. To everyone.”

“I was scared,” I admitted. “Scared if I bent once, everything would break. Turns out, bending’s the only thing that kept us from breaking.”

She clinked her glass against mine. “Here’s to bending.”

That Saturday, I woke up early again, the way I had for the do-over. I pulled out the skillet and the eggs, the vanilla and cinnamon. Bram wandered in, rubbing his eyes, hair sticking up.

“French toast again?” he asked, surprised.

“Yeah,” I said. “But this time, no rule attached. Just breakfast. Just us.”

He sat, grinning. Dalia bounded in and demanded “extra syrup.” Lila laughed and obliged. We ate together, all of us, no guilt, no lesson hiding in the shadows.

Just food. Just family. Just fair.

And I realized that’s what I should have been chasing all along.

THE END

News

When my 5-year-old saw our new backyard, she froze in terror… CH2

Part One: The autumn sun filtered warmly through the kitchen windows, gilding the countertops and filling the Carter home with…

At a Restaurant, the Waiter Whispered: “Go Through the Kitchen”—Then the Exit Was Blocked… CH2

Part One: I didn’t notice the note at first. I noticed the weight of the evening—all the small, perfect details…

I Overheard My Father-in-Law Plot Against Me — That Night I Moved Millions From Our Penthouse Empire… CH2

Part One: I never expected my life to become a chess game played in marble hallways and penthouse bathrooms. For…

I Threw A Party For My 10-Year-Old Son And Invited My Family — Nobody Came. A Week Later, Mom Sent… CH2

Part One: My name’s Evan Brooks. I’m thirty-three, a single dad, and the kind of person who can list the…

She Asked Me for Help Choosing a Dress for Her Boyfriend… But the Man in Her Photo Was My Husband… CH2

Part One: It started like any other Tuesday. I unlocked the boutique just before 10:00 a.m., turned on the lights,…

No One Understood The Millionaire’s Son, Not Until The New Nurse Used Sign Language To Save His Life… CH2

Part One: The hospital corridors smelled of antiseptic—sharp, clean, but laced with an undercurrent of sorrow. Fluorescent lights hummed…

End of content

No more pages to load