Part I

Look, I know how it sounds. I can hear the chorus already—homewrecker, liar, fraud—like a crowd warming up before the game. But stories don’t begin at the headline. They begin with the quiet things that don’t look like breaking at all: the way a house hums when everyone’s breathing in different rooms; the way a man you married becomes dependable as a lamp; the way you can love a person and still go hungry.

My name is Lillian. I’m fifty-one. For thirty-three years I have been Mrs. Arthur Whitcomb: three children, one tidy yard, a collection of casseroles I can assemble in my sleep. The kind of suburban life that looks lovely from across the street. It was lovely. It was, some days, perfect.

And then a cheerful little box with a stylized tree on it walked into our living room and pulled the carpet out from under everything.

Graham—our youngest, good-hearted and chronically undecided—bought the kits with his barista paycheck because “it’ll be fun, Mom, we’ll find out if we’re Viking or something.” We laughed. We spit into tubes like we were back in high school biology. Arthur looked almost boyish doing it, which is strange to say about a man who treats his recliner like a throne and his remote like a scepter. He was excited in a way I rarely saw: he never knew his biological father, just the stepdad who coached his Little League teams and taught him to change a tire. “Maybe I’ll get a name,” he said, and the softness in his voice made my heart ache with something that felt like tenderness and warning at once.

If I had been a braver woman, I would have fetched a hammer from the garage and turned that plastic tree into confetti. Instead, I sealed my vial, kissed the edge for luck, and mailed our future to a P.O. box.

Six weeks later, a Sunday afternoon folded itself around the house. I was in the kitchen with a knife and a pile of vegetables, the kind of domestic rhythm that makes me feel competent and necessary. Paige and Graham hunched over her laptop on the couch, the blue light turning their faces into pale moons. Audrey—always the lawyer, even on weekends—stood behind them, reading over their shoulders and issuing commentary like an analyst. The sound of their teasing was the music of my life.

“Ha! I’m more Irish than you,” Graham crowed.

“No way. It says I’ve got Basque roots,” Paige answered, delighted with the foreignness of it.

I smiled, wiped the last of an onion on the back of my wrist, and reached for the peppers. Then the music stopped. Not faded. Stopped. As if someone had lifted the needle off a record and cracked it in half.

You learn the weight of silence in a family: the sleepy kind; the angry kind; the “aunt said something racist again” kind. This was none of those. This was a hush with teeth. I laid the knife down, dried my hands that weren’t wet, and walked into the living room.

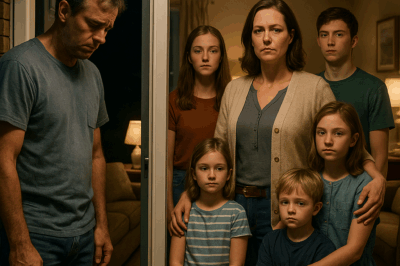

All three of them were staring at the screen. It wasn’t shock on their faces; it was the kind of horrified clarity that comes when a puzzle solves itself into a picture you don’t want. Audrey looked up first—my oldest, my golden girl, the one whose arguments may someday change a law and whose gaze has cross-examined me since she learned to talk. She looked at me like a stranger she didn’t trust.

“Mom,” she said, voice too calm. “What is this?”

When she said it, I knew which secret had found its way up through the floorboards and into the light. I’d always known it could. The knowledge lived in me like an old splinter you learn to live around.

“The system says Dad shares zero DNA with us,” Audrey continued, and the number—zero—hung in the air between us like a new planet. “With me and Paige. Not Graham. Graham matches.”

The room narrowed. I could hear the refrigerator hum and the clock tick, the world going on stupidly. My mouth opened and nothing came out. Somewhere in me, a younger version of myself ran for the stairs.

I didn’t scream. Not really. It was more like I let out the breath I’d been holding since I was twenty-nine. Then I did what cowards and mothers and people who’ve run out of words do: I left the room. I walked down the hall, my hand touching the doorframes like the house could anchor me. I shut our bedroom door and turned the lock.

I sat on the edge of the bed—the floral comforter suddenly a country where I did not speak the language—and I tried to find a lie that would be kind. There wasn’t one. There never had been.

The past arrived like weather. Dean’s face. Dean’s laugh. Dean’s easy way of leaning on a fence post in his front yard, three houses down, and asking how my day had gone like the answer mattered. Dean and Arthur had watched football together in our garage with the door open to the cul-de-sac, their shouts braided into the late afternoon. I would pass through with lemonade and find Dean’s eyes on me, warm as a porch light.

People despise women for saying this, but it’s true: I was lonely. Arthur was gentleness in theory and absence in practice. He was an accountant trying to become a partner, and he worshiped at the temple of the office. If he came home at six, his mind clocked out at eight and took the rest of him with it. I was twenty-something and home all day with a toddler and a marriage that hummed like a machine you’re not allowed to touch. When someone saw me, I mistook it for salvation. Judge if you want; I’ve already stood before the harshest juries: my own conscience and my daughters’ eyes.

The affair happened the way affairs do: one longer conversation, one laugh that lasts a beat too long, one day you don’t correct a misunderstanding about where you’ll be, and then a thousand small days after that. It was four years of stolen Saturdays and stupid lies and the kind of hunger that eats every good thing in your life and calls it dessert.

The girls were born in the middle of that weather. Babies don’t care who loves them; they care who shows up. Arthur showed up. He held them like miracles and warmed their bottles at two in the morning and learned how to braid hair from a YouTube video Audrey found for him when she was seven. Dean—well. Dean left when his company sent him east with a signing bonus big enough to buy a new story. There was no dramatic goodbye. Just a truck and a wave and my heart doing something between relief and grief that I’m still ashamed to name.

I told myself the leaving was a sign from God or from fate or from whatever deity oversees liars and mothers. I told myself the life I had chosen—the one with Arthur and three children and bills and bedtime stories—was the one that mattered, the one that made me worth the name I wrote on school permission slips. I told myself that burying the truth was benevolent: why hurt anyone with something that could no longer be changed?

And then: a plastic tree on a box.

Two hours passed, long enough for my phone to buzz twice with Arthur’s name and once with Audrey’s. I pressed my palms into my thighs until crescents bloomed there, little half-moons of pain that said you are here, you are alive, you have to get up. When I finally unlocked the door and walked back down the hall, my home looked like the aftermath of a party no one enjoyed.

They were all at the kitchen table—my motherhood’s stage—sitting as if they needed wooden chairs to keep their bodies from floating off the earth. The laptop was closed. Paige’s hands were flat on the table like she was bracing for impact. Graham looked like a boy again, not the man he wants to become, confusion softening his face in a way that almost undid me.

Arthur’s face was what stopped me from crying. Not anger, not yet. Blankness. As if someone had wiped him clean. He had the look of a man who has been told the map is wrong and the road is water.

I sat at the head of the table because that’s where I have always sat. It felt obscene to be in my chair; it felt cowardly to be anywhere else. I folded my hands and tried to make them look like my hands have always looked: capable, reassuring, the hands that iced birthday cakes and unwrapped Band-Aids with my teeth.

“His name was Dean,” I began. The words were sand in my mouth and somehow they still made a castle. “He lived three houses down. It was a long time ago.”

I told them. Not the version where I am a heroine; not the one where I’m a villain; the one where I am a human who made a choice and then another and then lost track of which choice was which. I told them about the way Dean filled a room with ease and how easy can look like love when you are starved for it. I told them about Arthur’s long hours and my loneliness, and how I hate how small that excuse sounds even when it is true. I told them I did not chart cycles against calendars with a scientist’s precision because I was not a scientist; I was a young woman who learned too late what consequences will grow out of the soil you disturb.

I told them it ended quietly when Dean moved. I told them I chose this family after that, every day, in ways Arthur never even noticed because they were invisible when I did them right. I told them I have been faithful since, faithful like a religion, that I never once, not for a second, loved them less than the air I breathe, that biology is a skeleton and we built bodies on top of it.

No one interrupted me. Audrey’s tears left neat tracks like rain lines on glass. Paige’s mouth trembled. Graham stared hard at a knot in the table, as if he could bore through it and crawl inside.

Arthur spoke only when I ran out of words. “Are you sure?” he asked. His voice came out flat and careful, like a board he was testing with his weight. “Are you sure they aren’t mine?”

“The tests,” I said, hating how pleading I sounded. “They’re—”

“How long have you known it was possible?” he asked, and the word—possible—picked up my splinter and pressed it into their palms.

“Since then,” I said. No more lies. “Since… then.”

He nodded once, as if acknowledging a weather report. The quiet hurt more than a shout would have.

He asked dates. He asked places. He built a timeline as if it might become a raft. I tried to answer without bleeding too much onto the floor. He asked if Dean ever held the babies. He asked if Dean ever spoke one word to them besides hello. I said no. I said never. I said please, please, please.

Here is a thing I still believe: I was not wrong to think telling them then would have been cruelty. A truth can be a weapon or a mercy. Twenty-five years ago, it would have been a weapon. Now, because of a game with a cotton swab, truth had decided to be a guillotine.

When I finished, no one moved. The clock above the stove ticked with the kind of authority that made me want to climb up and rip it off the wall. The dog in the yard next door barked twice and fell silent, as if even he knew this was not a world where barking was permitted.

Arthur stood. The chair legs scraped the tile with a sound that went through me like a blade. He looked at me the way he looked at the remote when it stopped obeying him: incredulous, betrayed by an object he trusted.

“I need you to leave,” he said.

“For how long?” I asked, because I am the kind of woman who believes in timers and recipes and fixable things.

“I don’t know,” he said. “I need… I need time.”

“Counseling,” I said quickly, like throwing a rope. “We can talk—we should talk—in counseling. We owe it to—”

“Maybe,” he said. “Not right now.”

He was not unkind. He was a man whose house had burned; you cannot ask a man holding a bucket to offer you a drink.

I packed a suitcase in the bedroom where I have folded his socks for three decades. He stood in the doorway. His eyes were not dead; they were blazing toward a horizon I could not see. I wanted him to shout, to break something, to cry, to hold me, to do anything that would let me answer with a hug or with anger. Instead, I placed two sweaters and a pair of jeans in a bag and remembered to take my toothbrush because being polite to your future is a habit that saves you later.

I went to my sister Maryanne’s because there was nowhere else to go. Her house smelled like lavender potpourri and the kind of pity that smiles. She made tea in a mug that said Live, Laugh, Love and looked at me like she was the mother and I was the child who brought a bad report card home. She tried for gentle. “Lillian, you need to take accountability,” she said, which is a sentence that sounds like virtue and tastes like chalk.

“I am,” I said. “I am here.”

At night, in her guest room, I stared at the ceiling and counted the lines in the plaster and timed my breathing against the train that runs two miles away. I texted Arthur paragraphs with the voice of someone throwing bottled messages into the sea: I love you; I’m sorry; I’m still here; can we talk; tell me what you need. He replied three times: I need more time. Please respect my space. Not ready. When I called, he let it go to voicemail. It felt like being erased one polite message at a time.

Friends, the ones who toasted our anniversaries and borrowed my bundt pan, brought casseroles to Arthur like grief ran in one direction. Brenda from next door texted Maryanne to say how brave he looked, how devastated but strong, and yes, she used asterisks like that. No one brought me anything but the moral of the story they wanted me to learn.

I told myself over and over that the affair had ended approximately a hundred lifetimes ago, that I had been faithful for almost three decades, that if faithfulness accumulates interest then surely I had earned a deposit of grace. But the math wouldn’t balance: two babies, four years, twenty-five hushed ones after that, and a little tree that made numbers into knives.

When the certified letter arrived with the law firm’s letterhead like a church seal, my hands shook as if the paper itself might bite. Arthur had filed. The attorney—a woman with a winter smile—asked for everything a life can be sorted into: bank records, phone logs, emails, social accounts. They found what you find when you go digging: not affairs, because there were none; just the tender, ordinary lies that women tell to keep a sliver of themselves—an undisclosed credit card I used to buy Arthur a surprise watch on our twentieth, a lunch that was really an afternoon wandering a bookstore because quiet is a luxury. In a deposition, the attorney tilted her head and turned those small freedoms into evidence of a pattern. I wanted to say: the pattern is I have kept us living and loved and fed and woven together for thirty-three years, but patterns that don’t come in spreadsheets don’t win cases.

The kids—my kids—tried for neutral. Then truth compounds even in the hearts of children. Audrey called and used her professional voice like a shield. “Mom, I’m disappointed in how you handled this,” she said. “Why couldn’t you be honest?”

“Honest when?” I snapped, and the bite in my voice startled us both. “When you were three? Would that have helped?” She didn’t answer. She hung up. Paige texted a heart and then nothing for a week. Graham sent a meme about everything being chaos and then: love you. It helped. It didn’t.

Three months into exile, the rumor arrived that Arthur was “doing better,” which is one of those sentences that feels like a betrayal and a relief at once. He’d joined a hiking group. He’d lost weight. He smiled at Brenda over the fence like a new man. The stories floated to me through Maryanne’s sighs. I hated the part of me that wanted him miserable. I hated the part that was glad he might stop hurting. Hate is complicated like that when you love someone.

Six months in, I found out about Chloe. She is younger, of course, that clean-sanded architecture of a woman who has never stayed up all night with a feverish child counting breaths. She likes him on mountains. She finds “starting over after a deep betrayal” romantic. She doesn’t know what it is to carry a life with someone through every kind of weather. Maybe she will. Maybe she won’t have to. Maybe I am cruel even in my thoughts.

Last Tuesday, I saw them in the grocery store under the harsh mercy of fluorescent lights. They stood in produce like a photograph for a prescription drug: two people touching avocados and laughing, as if there has never been a hospital bill in their lives. He looked happy. Not manic happy. Quiet happy. The kind of happy that comes when a man sets down a bag he didn’t realize was heavy.

Our eyes met. For a second I expected the montage: our wedding, the babies, the Thanksgiving we burned the rolls, the dog we buried under the maple. Instead, he looked through me. Not past me. Through me. As if I were the air between his old life and his new one. Then he said something to Chloe and she laughed that new-love laugh that forgives everything, and they turned their cart and were gone.

I stood there with a bunch of cilantro in my hand like a woman who had come to the store for one thing and forgot it. And in that aisle, I felt something clear and terrifying: maybe I had been wrong about the size of the thing I called a mistake. Maybe truth is not a weapon or a mercy; maybe it is a fact, and the damage comes from thinking you are in charge of it.

But here is another truth, unwelcome and bright: I loved him. I still do. I loved him with casseroles and calendars and the invisibility that keeps houses breathing. I loved him through the long miles of a marriage that looks like nothing from the highway and everything when you measure it by steps. If love counts—and I thought it did—why does it feel like I’m the only one keeping score?

The story, as it stands, makes me the villain. It always will. I can live with that. What I don’t know how to live with is the look a man gives a stranger in a grocery store when that stranger is the wife who washed his socks for three decades and learned the sound of his footsteps in the hall.

I went back to Maryanne’s and set the cilantro in a glass like flowers and said nothing when she asked how my day was. I lay in the guest bed and stared at the ceiling and tried to imagine a life that did not contain the sound of Arthur’s key in the front door at six. I tried to imagine the version of me who would have told the truth at the beginning and watched everything shatter then. I tried to imagine any future in which the words I loved you were not cross-examined out of existence.

Some nights the past comes to my sister’s house and sits on the end of the bed like a friend who does not knock. On those nights I remind myself of the things that are still true: Graham texts me silly videos. Paige sends me color palettes. Audrey, even in her frost, is mine. The hydrangeas in my garden—our garden—will need cutting back in March, whether I am there to do it or not. The moon keeps its schedule. So does the train two miles away. So does grief.

I don’t know how this ends. I only know how it began: with a tree on a box and a number on a screen and a family sitting at a table that had served us so many good meals and one terrible truth. If there is a judgement day for marriages, I suppose I will bring my receipts: the late-night fevers, the steady faithfulness after, the years of work that do not show up in a blood test. Maybe the judge will stamp them and say, “Still guilty.” Maybe that is what I deserve. Maybe I don’t believe in deserving anymore.

What I know is this: once, long ago, hunger walked into my house wearing my neighbor’s smile. I fed it. Then I spent twenty-five years cooking other meals to make up for it. And a little tree said none of it counts.

I don’t accept that. I can’t. If love is only biology, then all the knitting mothers have done in the dark, all the lunches packed, all the socks darned, all the jokes laughed at even when they weren’t funny—none of it matters. I refuse that universe. I choose the messier one where love sits with you at the table even when the test results say it has no legal claim.

But Arthur refuses to believe I ever loved him at all. And when the person you built your life around decides your love was counterfeit, there is no appeal. Only a door, and a key that no longer fits.

Outside Maryanne’s window the night goes on. A dog barks. A car turns the corner. Someone, somewhere, is running a dishwasher. I close my eyes and try to sleep. Tomorrow I’ll wake up and be the villain again. I will make coffee. I will answer my lawyer’s email. I will text my children because they are mine in every way that matters to me, even if that doesn’t matter to the rest of the world.

And I will begin again the hardest thing I have ever done: teaching myself how to live a life where the person I loved refuses to believe that I ever did.

Part II

Divorce papers don’t look like death. They come in crisp envelopes with embossed letterheads, carried by postal workers who have no idea they’re delivering a guillotine. But that’s what it was: the official autopsy report of a marriage. Every line item was a scalpel, every request for “documentation” a dissection.

Arthur had hired a shark. A woman whose gaze in depositions slid over me like I was roadkill she was cataloging for the county. Her questions were precise, methodical. Have you ever concealed purchases from your husband? Have you ever opened lines of credit without disclosure? Have you ever represented yourself as being in one place while you were in another?

Normal things—human things—suddenly stood under fluorescent lights as evidence of pathology. Yes, I’d opened a credit card once to buy Arthur a surprise watch for our twentieth anniversary. Yes, I sometimes said I was at lunch with girlfriends when I was really wandering a bookstore for a few hours, hungry for silence. Every married person I know does small things like this to protect slivers of themselves. But in the courtroom narrative, they became proof of a lifelong pattern of deceit.

Meanwhile, Arthur sat beside his lawyer with the composure of a saint. He’d lost weight, trimmed his beard, even ironed his shirts. I looked across the table at the man I had lived beside for three decades and saw someone who had repurposed his grief into a performance of dignity. And the world was clapping for him.

People talk about betrayal like it’s an event. But really, betrayal is a contagion. Once it’s exposed, it spreads. Friends who had sat at our table for countless dinners now stopped calling me. They carried meals to Arthur’s door instead—pot roasts, lasagnas, sympathy baked into foil pans. Brenda from next door whispered to Maryanne that Arthur looked “devastated but strong.” As if he had been widowed, not divorced. As if I were already dead.

I would see them on the sidewalk sometimes, pausing to chat with him as he watered the lawn, giving him pats on the shoulder that said, We’re on your side. And when their eyes slid over me, it was as though I were a shadow cast by some mistake in the architecture of the street.

No one brought me casseroles. No one asked what it felt like to be erased from your own story.

At first, Audrey, Paige, and Graham tried for neutrality. Family group texts still pinged, though Arthur never responded. But as Arthur’s lawyer presented more “evidence,” my daughters’ texts cooled. Audrey called one night, her voice clipped and professional.

“Mom, I’m really disappointed in how you’ve handled all this.”

“Honest about what, Audrey? That there was a possibility—twenty-five years ago—that your father wasn’t your biological dad? Do you think knowing that as a child would have helped you?”

“I wanted a mother I could trust,” she said, and hung up.

Paige’s texts became emojis instead of words. Graham, my baby, was the only one who still tried to reach me. He sent memes, silly videos, once even a link to a cooking recipe with the note, This made me think of you, Mom. But even in his messages I could sense the fracture—the way he didn’t know whether he was allowed to laugh with me anymore.

Children may grow, but when the ground beneath them splits, they instinctively pick the side that feels steadier. And Arthur had made himself the bedrock.

Maryanne’s guest room had become my purgatory. Her lavender potpourri clogged my nose, her sighs clogged my chest. She meant well, I suppose. But every time she said, “Lillian, you need to take accountability,” I wanted to scream. What did accountability look like? Hadn’t I already lost my home, my husband, my children’s faith? Wasn’t exile enough?

She liked to remind me that she’d been divorced twice, as though that gave her authority on the subject. But the difference between us was brutal: she left her marriages; mine had been stripped from me. She walked away; I was shoved out.

Sometimes I caught her staring at me over her teacup like she was studying a case study in shame. And maybe she was. Maybe everyone was.

Arthur went to therapy alone. Word got back to me through the grapevine: he was “processing.” He told mutual friends he “wasn’t ready for couples counseling.” Which to me translated to: I’d rather be the noble sufferer than do the messy work of repair.

I begged him. “Please, Arthur, we owe it to the kids to try counseling.”

“Not yet,” he’d say, his voice clipped, polite.

But how long is “not yet”? Three months? Six? Forever? The longer it stretched, the more it felt like “never.”

The certified letter arrived on a Tuesday. My hands trembled as I tore it open, recognizing the downtown law firm logo. Arthur had filed. While I’d been clinging to hope that he was just taking time, he’d been meeting with lawyers and financial advisors, building the scaffolding of my erasure.

The letter might as well have read: You are no longer Mrs. Whitcomb. You are Exhibit A.

The social narrative had crowned him Saint Arthur. Wronged husband. Noble father. Devoted man betrayed by his wife’s selfishness. It made me want to scream, Do you know how absent he was in those early years? Do you know the hours I spent alone with toddlers while he courted the firm? Do you know what it feels like to be invisible in your own marriage?

But the world doesn’t care for context. Context is messy. Victimhood is tidy.

Brenda told Maryanne he looked happier than he had in years. Relaxed. Almost glowing. I pictured him smiling at his hiking group, telling stories about betrayal, earning nods of sympathy and admiration from women who didn’t know him before he was sanctified.

Then came Chloe. A younger woman from the hiking group. When I confronted Arthur over the phone—my voice sharp with disbelief—he said, “My personal life is none of your business anymore.”

None of my business. Thirty-three years together, three children, countless meals, endless nights, and now his heart was someone else’s property, none of my business.

She’s younger, of course. Never married, no kids. From what I heard, she finds his story romantic: the noble man starting over after betrayal. She doesn’t know the Arthur who left dishes in the sink for days or forgot anniversaries until I reminded him. She doesn’t know the Arthur who shut down after hard days, who left me carrying the weight of every holiday, every social calendar, every emotional storm.

She sees a man rebuilt by grief. I see the man I built my life around, rebuilt for someone else.

Two weeks ago, I saw them. I was in the produce aisle debating spinach when I heard his laugh. It startled me—I hadn’t heard it in months. I turned, and there he was: Arthur, with Chloe, her hand tucked in his, her head thrown back in laughter.

They looked like teenagers. He looked… free.

Our eyes met. And for one second, I expected recognition. Some flicker of three decades. Some grief. Some regret. But his gaze was empty. He looked through me the way you look at a stranger standing between you and the dairy aisle. Then he turned back to Chloe, said something that made her laugh again, and walked away.

I stood there frozen, clutching cilantro, realizing with horrifying clarity: it was over. Not just the marriage. The story. My role in it. He had written me out.

Back at Maryanne’s, I sat on the guest bed staring at the ceiling and thought: maybe I was wrong all along. Maybe the affair mattered more than I let myself believe. Maybe secrets don’t stay buried—they fossilize, waiting for someone to dig them up.

But another part of me still whispers: I loved him. I loved him faithfully for three decades after Dean left. I loved him through sickness, through bills, through birthdays and graduations. Doesn’t that count for something? Or does one sin cancel out a lifetime of devotion?

Arthur refuses to believe I ever loved him. He says my choices prove otherwise. But I can’t undo those choices. I can only point to the years that followed and say: look. Look at the life we built. Look at the dinners, the laughter, the children. Look at the love that lived here.

But he won’t. He’s looking somewhere else now. At her. At the horizon. Anywhere but at me.

And so the autopsy continues: lawyers carving up assets, children choosing sides, friends delivering sympathy casseroles to the saint.

And me? I am left trying to figure out how to live in a world where thirty-three years of love can be dismissed as if they were counterfeit all along.

Part III

The divorce went through faster than I thought it would. Six months of hearings, depositions, and cold exchanges in courtrooms that smelled of dust and disinfectant—and then it was done. Thirty-three years signed away in a judge’s chamber with a stroke of a pen.

Arthur didn’t look at me when the decree was finalized. He kept his eyes fixed straight ahead, as if I were just another litigant passing through his calendar. Chloe was waiting for him outside the courthouse, her hand slipping into his like it belonged there, like it hadn’t taken me three decades of love and labor to earn that right.

The law calls it dissolution. What it felt like was erasure.

Packing was worse than any courtroom. The house on Hawthorn Lane—our house—was split in the settlement, sold to strangers who wanted to “modernize the kitchen” and “redo the garden.” My garden. I’d spent twenty years nursing hydrangeas that bloomed like blue fireworks every June.

I walked through those rooms with cardboard boxes and tried to decide what belonged to me. Did the photo albums belong to me or to the family we once were? Did the worn recliner Arthur had loved belong to me because I was the one who vacuumed around it every Saturday? Did the kitchen table where our children did homework belong to me, or to the memories that now only hurt?

I ended up taking less than I could have. Not because I was noble. Because every object felt radioactive. My hands shook when I touched them, as if they might explode with memory.

The strangers moved in two weeks later. When I drove past the house for the last time, the hydrangeas were already gone—ripped out, replaced by ornamental grasses. It felt like a second burial.

The children didn’t pick sides out loud, but silence has weight.

Audrey called less and less. When she did, her voice carried the clipped formality she uses in court. Paige sent occasional texts, breezy but thin, like postcards from a vacation she didn’t want to invite me to. Graham stayed in touch, but even his messages were cautious, as though loving me openly might be a betrayal to his father.

The last time we were all together was at Graham’s birthday dinner. He insisted on inviting both parents, thought maybe we could manage civility for one night. We did. Barely. Arthur and I sat at opposite ends of the table, Chloe next to him like a shiny new ornament. The kids tried valiantly to keep conversation going, but it felt like eating in a war zone between ceasefires.

When dessert came, Graham made a toast: “To family.” His voice cracked on the word. Nobody corrected him, but we all knew the truth: whatever we were, we weren’t that anymore.

Loneliness has a sound. It’s the click of a light switch in an empty room. It’s the echo of your own footsteps on hardwood floors when there’s no one to call you back.

At Maryanne’s house, I was a guest in a life that wasn’t mine. I folded myself into her routines—her yoga classes, her dinner parties, her endless lectures about “moving on.” But I felt like a ghost haunting a home that didn’t know me.

Nights were the worst. I would lie in bed, listening to the train two miles away, and think about Arthur asleep in another woman’s bed. I wondered if he snored for her the way he did for me, if she found it endearing or irritating. I wondered if she knew how he liked his eggs or the way his back locked up when he sat too long.

I hated myself for wondering. But I couldn’t stop.

Grief eventually hardens into anger. Mine came suddenly, like a storm. One morning I found myself screaming in Maryanne’s guest bathroom, my hands gripping the sink, my reflection red-eyed and wild.

“I gave him everything,” I shouted at the mirror. “Thirty years of loyalty after Dean, and he throws it away like garbage. Thirty years! Doesn’t that count for anything?”

Maryanne knocked on the door, alarmed. I told her I was fine. I wasn’t.

The anger didn’t stay in the bathroom. It followed me into the grocery store, the post office, the park. Every happy couple I saw was a provocation. Every Facebook anniversary post felt like a personal attack. I wanted to grab strangers by the shoulders and scream, You have no idea how fragile it is. One secret can ruin everything.

But I kept my fury folded inside, where it burned holes I couldn’t show anyone.

Still, there were quiet moments that cut deeper than the rage.

One afternoon, I dug through an old shoebox of letters—birthday cards from Arthur, notes he’d slipped into my purse, little scraps of handwriting that once meant intimacy. Reading them, I realized something painful: he had loved me. Truly. Even in the years I felt invisible, he had loved me in his quiet way. And I had betrayed that love.

It wasn’t just the affair. It was the lie afterward, the decades of silence. I had convinced myself I was protecting him, protecting the kids. But maybe I was really protecting myself—from his anger, from the consequences.

That realization sat in me like a stone. Because if Arthur’s love had been real, then my betrayal was bigger than I’d let myself believe.

The last time I saw Arthur was in the park, months after the divorce was finalized. He was walking with Chloe, hand in hand. They looked relaxed, comfortable. He saw me across the path. For a second, I thought he might nod, acknowledge me, recognize thirty-three years of history.

He didn’t. He just kept walking, his gaze fixed ahead.

And that was when I finally understood: in his mind, I wasn’t his past. I was nothing.

So here I am. Fifty-one years old, divorced, living in my sister’s guest room. My children keep their distance. My husband has erased me. My garden is gone.

And yet, I’m still here. Breathing.

Sometimes I think about Dean—the man whose smile once felt like salvation. I wonder if he knows the damage he left behind when he moved across the country. But mostly, I wonder about myself. The woman I was back then, the choices she made, the lies she told.

Did I ever really love Arthur? Yes. God, yes. With casseroles and calendars and quiet faithfulness for three decades after Dean. But Arthur doesn’t believe that anymore. And maybe love that requires explanation isn’t love at all.

That’s the reckoning: love doesn’t survive in court documents or DNA results. It survives in trust. And once that trust is gone, no amount of pleading can bring it back.

I cheated for four years, long ago. I ended it. I chose my family. I stayed. I loved. But none of that matters now.

Because to Arthur, the lie was louder than the love.

And now I am left with silence.

Part IV

There’s a strange thing about endings: they don’t announce themselves. You don’t get a trumpet fanfare or a flashing sign that says, This is the last time you’ll ever matter to this person. Endings creep in quietly, like fog slipping through a cracked window.

For me, the final chapter wasn’t the divorce decree. It wasn’t the sight of Arthur in the grocery store with Chloe. It wasn’t even the empty guest room at Maryanne’s house where I spent sleepless nights trying to rearrange the past.

It was the moment I realized my children were no longer my children in the same way they once were.

It happened with Audrey first. She called one afternoon, her voice clipped and efficient, the way she must sound in court.

“Mom, we need to set boundaries,” she said.

My stomach clenched. “Boundaries?”

“You can’t keep calling Dad, begging him to forgive you. It makes things harder for everyone. Especially for Graham and Paige.”

“I’m not begging,” I protested, even though I knew I was. “I just want him to know I still love him. I want him to believe—”

“Stop,” she cut me off. “He doesn’t believe you. He won’t. And the more you push, the less we can even be around you.”

It felt like she’d slapped me. “So what are you saying? That I have to choose between being silent and losing my children?”

“I’m saying,” she said carefully, “that if you want us in your life, you need to accept the reality. The marriage is over. Dad is moving on. And you need to stop trying to rewrite history.”

Her words hung heavy. Rewriting history. Was that what I was doing? Or was I just trying to remind everyone that the love I gave, the life I built, had been real?

“Okay,” I whispered finally. “I’ll stop.”

But when we hung up, I sat on the edge of Maryanne’s couch and sobbed until my chest ached.

Paige was kinder, but her kindness hurt more. She came to see me once, bringing takeout and a hesitant smile.

“You don’t look like yourself, Mom,” she said, handing me a box of lo mein.

“I don’t feel like myself,” I admitted.

She nodded. “I know you messed up. But I also know you’re still my mom. That doesn’t go away.”

Her words should have comforted me, but they didn’t. Because when she left that night, hugging me quickly at the door, I knew she was lying to herself. Children want to believe their parents are still whole, even when they aren’t.

Her visits grew less frequent. Her texts shorter. Eventually, she became just another name on my phone, glowing occasionally, reminding me of everything I’d lost.

Graham clung to me the longest. Maybe because he’s the youngest, maybe because he still remembers me as the mom who packed his lunches and drove him to soccer. He sent me silly memes, called on Sunday mornings just to check in.

But even he was pulled by gravity toward Arthur. After one of his visits, he confessed, “Dad doesn’t like it when I come here.”

“Why not?” I asked, though I already knew.

“He says it feels like I’m choosing sides.”

“You’re not,” I said quickly. “You love us both. That’s not a betrayal.”

He didn’t answer. And in the silence, I heard the truth: even love has to pick its battles.

The final confrontation with Arthur came on a gray November morning. I drove to the old house—not mine anymore, but still etched into my muscle memory. Chloe’s car was in the driveway. The sight of it made something sharp twist inside me.

Arthur opened the door when I knocked. He looked different—lighter, somehow. Not happy exactly, but at peace.

“What are you doing here, Lillian?” he asked.

I took a deep breath. “I need you to hear me. One last time.”

He sighed, but stepped aside. I walked into the living room where we’d celebrated Christmases, where our children had taken their first steps. The furniture was different now, Chloe’s touches scattered around. It felt like stepping into someone else’s life.

“I know I betrayed you,” I said. “I know the affair was unforgivable. But everything after that—it was real. The dinners, the birthdays, the decades of faithfulness. I loved you, Arthur. I still do. You can’t just erase that.”

His eyes hardened. “Erase it? Lillian, you erased it. Every time you looked me in the eye for thirty years and didn’t tell me the truth. You chose silence over honesty. That silence killed us more than the affair ever did.”

“I was protecting you!” I shouted. “Protecting the kids!”

“No,” he said firmly. “You were protecting yourself. And now you want me to believe your love was real? Love without trust isn’t love. It’s performance. And I’m done applauding.”

The words gutted me. But I saw in his face that nothing I could say would change them.

I left that day knowing it was the last time I would ever stand in that house, the last time I would ever plead for his forgiveness. I drove back to Maryanne’s, parked the car, and sat in the driveway until the sun went down.

For the first time, I stopped asking what I could do to make him believe me. I stopped imagining some miracle of reconciliation. I let the truth wash over me: Arthur would never believe I loved him. To him, I was a liar, a villain, a footnote in his story of starting over.

And maybe he was right. Maybe love without truth really is counterfeit.

The months that followed were quiet. Painfully so. But in the silence, I began to hear myself again.

I got a job at a local nursery, tending plants the way I used to tend my garden. Hydrangeas, roses, lavender. The work was dirty, grounding. Customers didn’t know me as “the woman who cheated.” They knew me as the lady who could tell them which soil would make their tulips bloom.

I started walking in the mornings, headphones in, the world waking up around me. I even joined a book club Maryanne recommended. At first, I felt like an impostor. But eventually, I laughed—really laughed—at a silly joke someone made about a mystery novel. It startled me. It felt like life.

The kids still kept their distance, but slowly, small cracks of light returned. Graham came to visit, Paige sent me a photo of her new apartment, Audrey forwarded me an article with the note, Thought you’d like this. It wasn’t forgiveness, but it was something.

One year after the DNA test results detonated our lives, I stood on the cliffs near the ocean, the wind whipping my hair, the waves pounding below. I thought of Arthur, of our thirty-three years, of Chloe, of our children.

And I said it out loud, my voice nearly lost in the roar: “I did love you. Even if you’ll never believe it. I did.”

The ocean didn’t argue. The wind didn’t judge. For the first time, I realized I didn’t need Arthur’s belief to make my love real. I knew what I had felt. I knew the choices I made after Dean left. That knowledge would have to be enough.

I cheated for four years long ago. That is true. I lied by omission for decades. That is also true. But so is this: I loved Arthur Whitcomb with every casserole, every bedtime story, every quiet act of devotion for thirty years afterward.

He refuses to believe it. Maybe he always will.

But I know it. And finally, that’s enough.

The End.

News

PART II: He Threw His Wife and 5 Children Out of the House… BUT WHEN HE CAME BACK HUMILIATED, EVERYTHING HAD CHANGED! CH2

The discovery of Octavio’s remains hit Guadalajara like a storm. It was not just news; it was a revelation that…

My Parents Texted “We Need Space From You, Please Don’t Reach Out Anymore At All” My Aunt Packed… CH2

Part I My name is Eliza Hart. I’m twenty-seven years old, and if you think abandonment kills the soul, wait…

My father dressed as Santa gave my 7-year-old daughter a bag of GARBAGE and a lump of coal… CH2

Part I: I used to think Christmas at my parents’ house was like a snow globe: sealed, shiny, and fake….

“Husband Brings Pregnant Best Friend Home to Ask for Divorce — I’m Overjoyed and Sign the Papers Immediately.” CH2

Part I The night began with the kind of soft, golden light that makes even a quiet Seattle living room…

Mistress Mocked Pregnant Wife In Court—But Judge Asked Her One Question That Ended It All… CH2

Part I: The cold, sterile air of the Mecklenburg County Courthouse in Charlotte carried the weight of broken promises. The…

📕I Cared for Her Through Cancer—stood by every chemo and fear—yet she married her first love instead… CH2

Part I: The first time the chemo pump beeped, I thought it sounded like a bedside alarm—one of those cheap…

End of content

No more pages to load