Part I

I didn’t plan the surprise like a movie. There was no orchestral swell when I turned into our street; the sky didn’t throw confetti. It was just cold—knife-edge, blue-steel cold that makes your breath turn to glass the instant it leaves you. The dash read 31°F and falling. The parking lot at St. Gabriel’s still had the chalk outlines of salt from the choir pageant the night before. I hugged a grocery bag to my ribs—wrapping paper, ribbon, two small boxes in the color my daughter loves, that pink that looks like it learned how to blush.

We’d said I wouldn’t be home until Christmas morning. The job in Cincinnati was supposed to keep me until the twenty-fifth dawned on the interstate. But the meeting wrapped early. A clerk at a rest stop sold me tape and said, “Safe travels, sir,” like a benediction. I thought I would be the one giving blessings: surprise! I pictured the way my wife’s mouth would shape into a perfect O, the way our daughter would sprint—all knees and elbows—down the hall yelling “Daddy!” with that open-throated joy that makes you feel, for a second, like you are the best decision you ever made.

Our driveway, when I pulled up, held no tire marks except mine. The house had that winter quiet—curtains drawn, a smear of yellow light at the edges like a reluctant halo. It was not sleepy, not festive—just closed. The gift bag cut into my fingers. I remember thinking, absurdly, that I should have carried them differently.

I saw her then, small and dark and shivering on the porch. No coat. No hat. No shoes. A blanket of air on her bare legs. For a second my brain did the petty, bureaucratic things brains do: calculate distance, catalog details, try to make the world abide by the paperwork. Then everything was just movement. I dropped the bag. The boxes spilled and slid like fish. My keys hit the step and jumped. I reached my daughter in three strides and gathered her up. Her body was the temperature of worry; she made a small sound, a sound I have never heard from any human and will never forget, a string’s last note when it breaks.

“Hey. Hey, hey.” I folded her into my coat and felt fingers like frozen grapes press into my chest. “What are you doing out here, baby?”

Her mouth moved. The air was so cold I could see the syllables but not hear them. Her lips were pale and a little blue the way lips get when you’ve been swimming too long in lake water. I pressed her face into my neck and turned toward the door.

From inside, music floated—the kind of soft jazz she likes to put on when she wants to pretend we are older and wealthier than we are. Laughter—hers. A cork popped. Someone said “to us” in a voice I didn’t recognize. The house inhaled champagne and exhaled warmth.

I pressed my ear to the door like a man in a farce. I’m not proud of that second. I’m not ashamed either. I’d been dialing past static for months, trying to settle on a station I could live in. I heard her again: “My wife, laughing, warm, alive,” a sentence I couldn’t make bear sense. While our child froze, she was laughing. While our child’s fingers tightened into my collar, someone else was toasting.

Something inside me, some thin rod that had held up more weight than it was rated for, bent and then snapped. It didn’t make a dramatic sound. No cinematic crack. Just a quiet shift—like a rib slipping under a hand—that told me the old rules had run out.

I kicked the door. It splintered at the latch like cheap wood will when it realizes a story has reached its turning point. Warmth fell on my face with the sticky sigh of a room that has forgotten the weather. I carried my daughter across the threshold like I was bringing her back from a place the house had refused to admit existed.

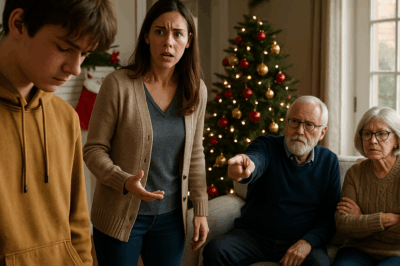

The living room looked like a catalog—the fire staged, the mantel garlanded, the lights set to a dim that said effortless in a way that takes effort. My wife stood by the hearth in a dress I hadn’t seen and a smile she dropped like a glass as soon as she saw us. Her wine flute stopped midair. Her eyes got wide the way eyes get wide when they’ve just been reminded that time is not a straight line.

“You left her out to die,” I said. Six words. I wasn’t trying to be a writer. It’s just what came.

The silence after those words was so complete that even the fire seemed embarrassed by its own crackle. Somewhere a speaker kept crooning through the fractal heartbreak. She blinked. “I—I didn’t. She wanted to play.” The lie was instinctive, smooth, ready. You could tell it had practiced.

My daughter made a sound, that broken-string note again, and clung harder. I wrapped my coat tighter around her, sat on the couch we bought when we thought the marriage deserved nicer furniture, and felt her small breaths stutter into my sternum.

“Overreacting,” my wife said, and I almost admired the nerve. “You’re overreacting.”

Words have weights. “Overreacting” is a feather until someone tries to hand it to you like a dumbbell. I didn’t say anything. I let silence take up the room like cold air rushing into the space the jazz had already forfeited. She felt it. You could see it in the twitch at the angle of her jaw, the way her eyes kept skittering toward the fireplace, toward the hallway, toward anywhere but me. Her laughter, I realized, hadn’t been for herself alone. It had been curated. Stage-managed. The room smelled of something warm and baked and a cologne I have never worn.

Two glasses. Two plates with the polite smear of dinner left by people who intend to move on to dessert. A foil neck from a bottle in the trash that was not the brand I buy, but the brand an old acquaintance had once rhapsodized about when we were all too young to afford preference.

My chest did that stupid thing—tighten, release, tighten again—as if it had not read the memo my brain just drafted. There are moments that bloom like bruises: slow, then sudden. It wasn’t just negligence anymore. It was careful neglect. It was choreography. It was betrayal threaded through with logistics and timed corks.

“Upstairs,” I said, and she flinched like the word had hands. “She needs a bath. Warm. Now.”

“I’ll—” she started, moving toward me with a softness that used to be for me and is, in fact, one of the reasons I married her.

“I’ve got her.” I stood, my daughter a curl of winter under my coat, and walked past my wife, past the mantle with the stocking she’d stitched my first Christmas here, past the table where two plates had been laughing, and down the hall to the bathroom.

The water ran a hush. Steam rose like an apology. My hands shook as I tested the heat, not because I was scared of burning her—God forbid—but because some part of me was doing inventory and had found entire shelves empty. When I undressed my daughter, her knees were the color of old marble. She whimpered when the water touched her and then, slowly, sighed. I washed her hair with the gentleness of a person handling something that has been dropped but not broken. She leaned back into my palm like she always did when she was a baby and the world had not yet learned how to complicate itself.

“Daddy?” she said, her voice drowsy and small and complete.

“Yeah, baby.”

“Is Santa… mad?”

“No,” I said. “Santa’s got bigger problems.” She smiled—the sleep-smile kids get when their bodies remember they are allowed to rest—and I wanted, right then, to believe in every story that had ever saved anybody from anything. I wrapped her in a towel that smelled like cedar, carried her to our bed because my bed felt like a place the house could not argue with, and lay beside her until the shiver left.

When I went back downstairs, the jazz had learned embarrassment and turned itself down. The other glass was gone. The plates were stacked, the way plates are stacked when someone wants you to think plates stack themselves. She stood by the sink, hands braced like she expected the porcelain to throw her a rope.

“She was out there five minutes,” she said before I asked. “Maybe seven. She wanted to see the lights. You know how she—”

“Your coat rack is empty,” I said. “Her coat hook is full. She is six. It is thirty-one degrees. You were drinking.” Each sentence felt like a nail. I did not like how good it felt to hammer.

“She’s fine,” she said. “You’re making this—”

“Stop.” I didn’t raise my voice. I didn’t need to. The house did it for me. She opened her mouth, closed it, poured herself another glass, and found that her hands shook too.

“I’m tired,” she said. “I’ve been—”

“Who is he?” I asked. She blinked, the way people do when daylight walks in on them in the middle of a story they didn’t rehearse far enough.

“I don’t—”

“The cologne.” I lifted my chin toward the door, toward the glass, toward the room the music had vacated. “The champagne. The champagne brand you’ve never liked except when you’re with him. Two plates. Two glasses. The smile you wore into the air while our daughter shook on the porch.”

She did not answer. There is a kind of silence that looks like wisdom and another kind that looks like a traffic accident. This was the second, terrible and instructive. She waited me out. She must have thought the man she married was still the man who apologized to the room when he bumped into furniture. The man she married had left his shape on the couch upstairs next to a sleeping child.

I did not confront her. Not that night. I tucked the word later into my pocket with my keys and the wrapper from the ribbon and I went upstairs and lay next to my daughter while the house made the small sounds of a structure settling into its own weight. I heard my wife move around in the kitchen, then not move; heard the front door open, then close; heard nothing; slept; woke before dawn to a room washed thin with winter gray.

She slept beside us, tangled in silk sheets, hair perfect in the way hair can only be when it has been tended to for an hour by someone who isn’t tired. My daughter slept warm against my side, breath regular, forehead less hot. I slid out from under the miracle that is a child staying asleep, pulled on jeans and a sweater, and sat at the dining table with a new cup of coffee and the cold light of the screen.

I didn’t go looking for stories. I went looking for receipts. Phone records. The little red badges on apps that tell you something wants to be noticed. I found numbers I didn’t recognize with a frequency that said intricate. I found a text thread archived but not deleted, a carelessness I took as an insult. I found sentences that had no business in our house. tonight. yours always. same champagne?

I did not rage. I printed. The printer coughed and fed and coughed again, as if pained to be a witness. I made a pile. I made two piles. I triangulated a life. Hotel receipts. A restaurant we’d never been to with the exact bill a man brags about when he wants to talk about how much he spends and not how much he earns. A charge for a rideshare on a night I had been on an airplane. The champagne brand I had never bought and would never buy now, not because it wasn’t good, but because it had been enlisted in a cause I would not fund.

I built a file like I was building a wall. Not because I wanted to trap her in it, but because I was done letting the wind take our sentences. If there was to be an ending, it would use the dictionary.

All morning I watched her move through the house like a woman auditioning for the part of wife. She smiled too wide. She put on coffee like it was a costume. She asked about Cincinnati like she had been thinking of me there. When she hugged me, she tucked her head into my chest the way she does when she wants to hide and be forgiven in the same minute. I let her. I cataloged. I set my face to patient.

When the sunlight found the ornament that looks like a glass apple and set a circle of red on the table, I slid the file into the light. She looked at it, then at me, then back at it. She didn’t touch it, the way you don’t touch a dog that isn’t sure if you’re friend or stranger.

“What’s this?” she said, and her mouth tried for a smile that would have worked on anyone who didn’t have the receipts.

“Your life,” I said.

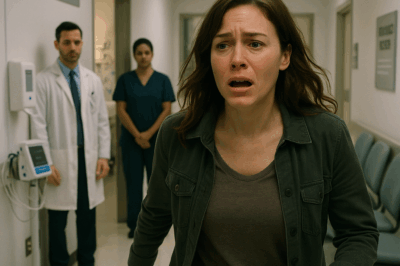

She opened it. The first page was just phone records. I watched the calculation flicker—how to explain, how to confuse, how to pick a fight so we would be arguing about tone and not about facts. The second page was a hotel confirmation. Her skin lost a shade. By the third page, her hands shook. By the fifth, her mouth gave up its work and turned into the shape a mouth makes when it is trying not to be sick.

“You went through my—”

“I know everything,” I said, and it wasn’t bravado; it was a quiet sentence sitting on a chair it deserves. She cried then. It was loud and ugly and immediate, and if I had been the man I was a year ago, it might have worked on me. She reached across the table and I did not move. She offered words—mistake, overwhelmed, lost, forgive—and each one fell off the edge of the table like a piece of cold toast.

I reached for my phone and pressed play. Her lover’s voice filled the room—low, intimate, the music of a man who has never done a hard thing at three in the morning for someone who couldn’t do it for themselves. He said her name the way my name should be said. He promised a future in sentences she had once used on me when our furniture was cheap and our belief was expensive. She froze as if the air had gelled. The sound moved around her like smoke.

In the doorway to our room, a small shape appeared—blanket around shoulders, hair in knots a brush could persuade when the day got proper. My daughter’s eyes were those deep, clear eyes children get when they are already writing rules the adults around them will have to live by.

“She knows what you really are,” I said.

My wife turned, saw the child she had left on a porch in thirty-one degrees without a coat and a mother and a decent reason, and broke into the pieces she should have broken into last night. She slid off the chair and crawled toward the doorway. “Baby,” she said. “Baby, I’m so sorry.”

My daughter stepped back instinctively, the way you step back from something that is both familiar and hot. She did not cry. I did not speak. The room filled with a silence that had different work to do than the silences before. It was not for suffocation anymore. It was for clarity.

That was the beginning of my revenge. Not anger—I have anger, yes, but anger burns the person who carries it. Not violence—violence is for people who lose arguments and then pretend they won. The revenge was small and honest and terrible: truth, cold and sharp as the air last night, laid out in the one place it could not be argued with—in front of the only witness that mattered.

I packed later, slowly, with the deliberation of someone who has realized that leaving is a craft. My daughter sat on the bed like a tiny judge and watched me fold my shirts. My wife moved around the edges of the room saying the kinds of things people say when they have run out of better things: we can fix this, I’ll change, think of Christmas, think of us. They rose like smoke and dissolved before they reached me.

By nightfall, we were gone. The bags were in the trunk like tamed animals. My daughter fell asleep ten minutes into the highway, mouth open, breath sweet, trust reassembling itself like a bridge.

As the taillights stitched the road into a path and the radio found a station that refused drama, I looked in the rearview at the blanket, at her small shoe that had lost its partner in the house I would not return to, and I found nothing dramatic left in me. No pity. No sorrow. Just clarity, as clean as the cold had been.

Love does not survive neglect. It does not survive betrayal. It dies in silence. Last night, I had learned that silence can also be a knife that cuts your bindings.

The last thing I saw of the house was the doorway where she had left our daughter to freeze. The porch light, still on, made a small halo that meant nothing. I drove into a night that had room for us and felt, for the first time in months, the thin rod inside me begin to reforge under heat that was mine.

Part II

The first morning after we left, I woke before my daughter. We were in a motel off Route 22, the kind of place that advertises “FREE HBO” on a sign missing two bulbs. The heat rattled through vents like dice in a cup. I sat on the edge of the bed with my laptop open, a Styrofoam cup of coffee in my hand, and the sick calm of someone who has stepped off the battlefield but hasn’t put down the sword.

My daughter stirred, sighed, and burrowed deeper into the blankets. Her fever had broken overnight. I ran a hand over her hair, whispering promises I wasn’t sure I could keep but knew I had to make: You’re safe. Daddy’s got you. No one’s leaving you in the cold again.

That day, I began the real work.

I started with our shared cell plan. Online access, two numbers, one password she thought I didn’t know. I combed through the last six months. Strange numbers, late-night calls, bursts of texts in patterns too regular to be innocent. I wrote them down. Time stamps. Duration. I opened a new folder on my laptop, titled it with the same deliberate cruelty I’d shown when I said those six words last night: Her Life.

I dug through the console of my car, the junk drawer in the kitchen where I’d shoved months of household clutter. Credit card statements synced to my email. Patterns emerged—restaurants I had never been invited to, hotel check-ins that lined up perfectly with my trips out of town, purchases of champagne she had once said gave her headaches.

She hadn’t even tried to cover her tracks. Careless. Bold. Or maybe just certain I’d never look.

It didn’t take long to put a name to the number. An old friend from college. I’d shaken his hand at our wedding reception, clinked glasses with him when my daughter was born. He’d grinned at me with the teeth of a wolf and I hadn’t seen it. Now his name lit up in her call logs like a neon sign.

I didn’t confront her immediately. Confrontation is theater. I wanted documentary. I wanted exhibits A through Z. So I became quiet, patient. I lived in the house like a ghost who took notes.

She didn’t notice. Or maybe she did, and mistook my silence for forgiveness. She smiled at me too wide. She folded my laundry with hands that shook. She touched me at night as if guilt could be disguised as affection. I let her. And while she thought she was controlling the scene, I was building the file that would be her prison.

By New Year’s, it was thick enough to slap when dropped on the table. Dozens of pages. Photocopies. Screen captures. Receipts printed on curling paper. Each page a brick in the wall between us. I stacked it neatly in a black binder, the kind we’d once used together to budget vacations. It sat on my desk, quiet and heavy, waiting

It was a Sunday. Christmas ornaments still dangled hollow in the living room, mocking us with glitter. She made coffee. I set the binder on the table between us.

Her eyes narrowed. “What’s this?”

“Your life,” I said.

She opened it. Page by page, I watched her unravel. At first she tried to bluff—rolled her eyes, smirked, called me paranoid. Then the receipts came. Hotel check-ins. Dinner bills. Phone logs. The champagne. Her face drained. By the time she reached the screenshots of texts—tonight. yours always—her lips were trembling. The glass in her hand rattled against the table.

“You went through my—”

“I know everything.”

She cried. Loud, desperate tears. She reached for me. I stayed still. She begged. I stayed silent. She tried mistake, overwhelmed, forgive. The words were smoke that never reached me.

Then I pressed play.

Her lover’s voice filled the room. I’d recorded one of their late-night calls when she thought I was asleep. His voice was low, adoring, promising her futures she’d once promised me. My wife froze. Her eyes went wide. The sound of her betrayal filled the room like smoke, choking her own breath.

Then I spoke again. Six more words, just as sharp as the first:

“She knows what you really are.”

My daughter stood in the doorway. Blanket around her shoulders. Eyes too old for her years. She looked at her mother the way only children can—clear, unforgiving, with the kind of truth adults spend lifetimes trying to smother.

My wife collapsed, sobbing, crawling toward her. “Baby, please. I’m so sorry.” But my daughter stepped back.

I didn’t say a word. The silence was enough. It pressed. It suffocated. And this time, it wasn’t mine to bear—it was hers.

I didn’t leave that day. I wanted her to sit in it, to live with the silence. The next morning, while she begged, bargained, and promised change, I packed. Slowly, deliberately. My daughter sat on the bed, quiet, watching me fold shirts into a suitcase. Every zipper, every snap of a clasp, was a verdict.

By nightfall, we were gone.

We drove away under a sky emptied of stars. My daughter fell asleep in the back seat, clutching the stuffed rabbit I’d tucked into her arms. I stared at the dark road ahead. No pity. No sorrow. Only clarity.

Love doesn’t survive neglect. It doesn’t survive betrayal. It dies in silence. And the silence between us was already complete.

The last thing I saw of her was the doorway where she had left our child to freeze. The porch light glowed like a false halo. And I knew I would never come back.

Part III

The first week on our own felt like stepping into air that hadn’t been breathed yet.

I rented a small two-bedroom apartment above a hardware store on Main Street. The ceilings were low, the carpets smelled faintly of dust and paint, but the windows opened without protest, and the locks worked. Most importantly: no porch, no freezing air, no one left outside.

My daughter—Lily—adjusted with the resilience only children seem to have. She missed her room, her toys, the big backyard. But she loved the hum of the shop below us, the jingling bell on the hardware store’s door, the old man at the counter who gave her a peppermint every afternoon. I bought her a secondhand desk and painted it blue. “For homework,” I said, though we both knew it was also for coloring books and drawing pictures of rabbits.

Two days after I left, my wife called. The screen lit up with her name, and for a moment, my thumb hovered. Then I let it go dark. She texted instead: Please come home. Please, we can fix this. She needs her mother. I didn’t reply. By New Year’s, the texts shifted: You can’t do this. I’ll take you to court. You’ll lose her.

I welcomed it. Courts live on paper, and I had paper.

The file I’d built became my shield. I hired a lawyer with the same methodical patience I’d used gathering receipts. When he saw the binder, his brows rose. “You’ve done half my job for me,” he said. Phone logs, credit card records, hotel check-ins. Neglect. Infidelity. Endangerment. Every page a stone in the wall I’d built around my daughter.

The custody battle never made it past the first hearing. The judge read the evidence, looked at my wife with eyes that had seen too many lies, and granted me full custody pending a review. She was allowed supervised visitation twice a month. Even then, Lily didn’t want to go. After the first visit, she came home quiet, then whispered, “She smells like him.” I didn’t ask more. Some truths are too raw for small mouths to speak.

It didn’t take long for the man to appear—her old college friend, the one whose cologne I’d smelled in my house. He showed up in the background of her life, at the supervised visits, waiting outside the courthouse in his slick car. I ignored him. He wasn’t my problem. My problem was making sure Lily never again stood on a porch in the cold while her mother laughed over champagne.

But I couldn’t help noticing: he looked worn already. Guilty men often do. Desire burns bright, but it’s a cheap candle. It melts fast. I imagined him, someday, realizing she was the kind of woman who left her child outside for appearances. I wondered if he’d still toast her then.

I threw myself into work and Lily. Days were long but clean. I dropped her at school, went to the office, picked her up, cooked simple dinners—macaroni, chicken, vegetables she sometimes ate, sometimes pushed around her plate. At night, I read to her. She liked the same book over and over: Charlotte’s Web. She loved the pig’s innocence, the spider’s loyalty. One night, after I closed the book, she asked, “Daddy, am I like Wilbur?” I kissed her forehead and said, “You’re braver than Wilbur. You walked through fire.”

I meant it. She had walked through freezing dark, through silence, through betrayal she hadn’t deserved. And she had survived.

My wife wrote letters. Long, rambling, apologetic. Promises to change, pleas for forgiveness, excuses wrapped in self-pity. It was only once. It didn’t mean anything. I was lonely. You were gone too much. You didn’t see me.

I burned the first three in the sink. By the fourth, I didn’t bother opening them. Lily didn’t need to see me reading words that tried to excuse leaving her outside on Christmas Eve. Some sins don’t get washed away with ink.

Children notice more than we want. Lily’s eyes had changed. They were still wide, still curious, but deeper, older. When I tucked her in, she sometimes asked questions no six-year-old should: “Why did Mommy want him and not us? Was I bad?”

Each time, I swallowed the lump in my throat and answered carefully. “You are the best thing in my life. Mommy made mistakes, but they’re not your fault.”

She nodded, like she wanted to believe but couldn’t yet. Healing is slow. I knew we’d spend years untangling the knots her mother had tied into her heart.

It was March when she showed up. My wife. She knocked on the apartment door while I was making spaghetti. Lily was at the table drawing. I opened the door, and there she stood—hair perfect, coat expensive, eyes swollen from crying.

“Please,” she said. “I just want to talk.”

I stepped outside, closing the door behind me. “Talk,” I said flatly.

She tried everything. Apologies, explanations, tears. She clutched at my arm. “It wasn’t supposed to go this far. I didn’t mean to hurt her.”

“You left her outside to freeze,” I said. “There’s no farther than that.”

She sobbed. “I miss her.”

“Then you should have thought of her that night.”

Behind me, I felt Lily’s eyes watching through the curtain. My wife noticed too. She moved toward the window, reaching a hand out as if touch could erase months of betrayal. But Lily pulled back.

That was the moment I knew: no matter what court papers said, no matter what visits were arranged, my daughter would never again look at her mother the same way. That bond was severed—not by me, but by her choices.

By summer, the noise of court and lawyers had faded. Life became routine. Work. School. Dinner. Bedtime stories. Lily laughed more. She joined soccer. She made friends. Her cheeks pinked in the sun, her legs got strong. The haunted look eased from her eyes. Slowly, she was reclaiming her childhood.

As for me, I learned silence could heal as well as hurt. The silence of our new home at night—safe, warm, free from shouting or slammed doors—was medicine. It taught me to breathe again.

Sometimes, after Lily fell asleep, I sat by the window with a glass of water and stared at the streetlights. I thought about that Christmas Eve. The sound of laughter from inside. The sight of my daughter’s lips, blue with cold. The six words I’d spoken. You left her out to die.

They still echoed. They always would. But they didn’t hurt anymore. They reminded me why I left, why I fought, why I built a new life from ashes.

That was the fallout: a broken marriage, yes, but also a saved child, a rebuilt home, a truth laid bare. I lost a wife, but I kept my daughter. And in the end, that was all that mattered.

Part IV

The summer passed into fall, and with it, the first full year since Christmas Eve loomed on the horizon. By then, life with Lily had settled into a rhythm—messy, imperfect, but steady. I woke early, packed lunches, worked hours that balanced bills with bedtime, and ended every night with the same promise whispered against her hair: You’re safe. Daddy’s here.

But the shadow of my wife—ex-wife, as the papers would eventually declare—still lingered. Not in our home, not in our daily lives, but in courtrooms, in letters I didn’t read, in Lily’s occasional whispered questions: “Why didn’t Mommy want to stay with us?

The divorce hearings began in September. She came in dressed like contrition—black dress, simple jewelry, hair tied back. She looked at me with wet eyes, then at the judge with practiced sorrow. But I had the file. The file didn’t cry. The file didn’t make excuses. The file spoke in receipts, texts, and photographs.

When the judge asked if she contested full custody, she opened her mouth. Her lawyer touched her arm. She closed it. The gavel came down. Custody was mine. Supervised visitation remained, but Lily never wanted to go. After the second visit—awkward hours in a neutral playroom with plastic chairs—she clung to me, whispering, “Daddy, please don’t make me go back.” I didn’t. The court listened. The visits ended.

By October, I heard through mutual acquaintances that the man she’d risked everything for had left. Moved to Chicago, new job, new girlfriend. He hadn’t lasted a year. Desire makes bright promises but pays in ashes. She was left behind, alone, her “fresh start” nothing more than a smoldering pile of regret.

A part of me thought I should have felt vindicated. I didn’t. I felt… nothing. She had chosen him. She had chosen champagne over her daughter’s safety. Now she lived with the consequences. That was enough.

Lily thrived in school. Her drawings grew brighter, her laughter less hesitant. At night, she still asked questions I couldn’t always answer. “Does Mommy love me?” she whispered once.

“Yes,” I said carefully. “But sometimes love isn’t enough when people make bad choices.”

She nodded slowly, as if she’d already learned this in her bones. Kids understand more than we think. She crawled into my lap, her head on my chest. “Then I’ll just love you more, Daddy.”

I cried after she fell asleep. Quietly, so she wouldn’t hear.

By winter, word spread that my ex-wife had lost her job. She’d burned through savings, through friends, through the patience of her own family. The champagne nights were over. Now she rented a one-bedroom apartment near the edge of town. Neighbors said she drank too much, cried too loud, and sometimes stared out her window like she was waiting for someone who’d never arrive.

She sent another letter. This one I opened. The handwriting was jagged, desperate. I’m sorry. I was lonely. I made mistakes. Please let me see her. Please give me another chance. Please don’t teach her to hate me.

I folded it neatly, slid it back into the envelope, and locked it in the same drawer as the file. Not for me. For Lily. Someday, if she wanted, she could read it and decide what to do with it. The choice would be hers, not mine.

Christmas Eve returned, one year later. Snow fell thick over the city, turning streets into a hush of white. Our apartment smelled of pine and cinnamon. Lily wore her red pajamas, the ones with snowflakes, and begged to stay up late for Santa. I let her. We decorated cookies, watched a movie, and laughed until her eyes drooped and her head lolled against my shoulder.

At midnight, I carried her to bed. I kissed her forehead and tucked the blanket tight. Then I sat by the window, staring out at the snow, remembering the year before. Remembering the porch. The cold. The laughter inside. The six words I’d spoken. You left her out to die.

The silence of that night had killed my marriage. This silence—the peaceful, safe silence of a warm home—was proof that leaving had saved my daughter.

People sometimes ask if I regret not giving her mother another chance. My answer is always the same: “She had her chance. She had every chance. And she chose betrayal.”

Forgiveness may be noble. But protecting my child is sacred. There’s no negotiation in that.

As the clock struck midnight, I made myself a quiet vow. The past was over. The betrayal, the file, the court battles—done. Ahead was only Lily. Her laughter. Her life. Her future. My job was simple: keep her safe, keep her warm, keep her loved.

And when she grew old enough to understand everything, I’d tell her the truth. Not to make her hate her mother, but to make her see what choices mean, how silence can kill, and how love must be proven in actions, not just words.

That was the ashes of my marriage. That was the fire I walked out of. And what I carried with me—the small, shivering girl on the porch—was all that mattered.

The rest, I left behind in the cold.

Part V

Years passed. They didn’t gallop; they trudged, one season at a time. But with each season, Lily grew taller, steadier, less shadowed. And I—I learned how to live again without carrying silence like a coffin on my back.

By the time Lily was ten, she was a girl full of questions and quick laughter. She loved soccer, hated math homework, and painted her room in shades of yellow that made the apartment glow even on gray days. Sometimes she would curl beside me on the couch, her head on my shoulder, and ask things like, “Daddy, do you ever get lonely?”

“Sometimes,” I admitted.

“Me too,” she’d whisper. Then she’d grin, quick as sunlight breaking clouds. “But at least we’re lonely together.”

And just like that, I’d know we weren’t lonely at all.

Her mother tried, off and on, to claw her way back into Lily’s life. Letters, messages, the occasional attempt to show up at school or a soccer game. But Lily never wanted to see her. Each time I offered the choice—Do you want to visit?—she shook her head, her jaw firm. “She left me outside, Dad. That’s what I remember.”

As she grew older, she asked more questions. “Why did she choose him? Why wasn’t I enough?” Those were the nights I sat long at her bedside, stroking her hair, telling her the only truth I could: “It wasn’t you. It was her choices. You were always enough.”

Sometimes she nodded. Sometimes she cried. Always, I stayed until she slept.

For years, I lived only for her. Work, home, bedtime, repeat. People told me I should “move on,” find someone else. I nodded politely, but inside I thought: I already have someone. She’s upstairs, drawing superheroes with blonde braids and capes.

But time has a way of softening edges. When Lily was twelve, she sat me down one night, arms crossed in mock sternness. “Dad,” she said. “You should go on a date.”

“A date?” I blinked.

“Yes. Like normal people. You can’t just sit here forever. What if something happens to me? You need someone too.”

Her words struck harder than I expected. She wasn’t pushing me away—she was pushing me forward. And for the first time in years, I let myself imagine the possibility of being more than just a survivor.

When Lily turned fifteen, her mother reached out again. This time through the courts. She claimed sobriety, counseling, repentance. She asked for visitation.

The court called Lily in. She sat across from the judge, her back straight, her eyes steady. “I don’t want it,” she said firmly. “She had her chance. I was six. I remember. I’ll never forget.”

The judge nodded. Case dismissed.

That night, Lily crawled into bed beside me like she hadn’t done in years. “I thought I’d feel sad,” she admitted. “But I don’t. I just feel… free.”

I kissed the top of her head. “That’s because you are.”

She earned a scholarship—art and academics combined. When we toured campuses, she carried herself with the kind of confidence I’d only dreamed she’d one day find. On the night before she left for her dorm, we sat on the porch of our apartment building. The same porch I’d carried her onto years ago, frozen and small.

“Do you ever think about that night?” she asked.

“Every day,” I said.

“Me too.” She paused. “But not like a nightmare anymore. More like… a story. A story about how you saved me.”

Her eyes glistened in the streetlight. “And how I saved you too.”

She was right. She had. Her tiny hands clutching my collar, her blanket around her shoulders, her voice steady in court years later—she’d saved me as much as I’d saved her.

I saw my ex-wife one last time. It was years later, after Lily had graduated college. I ran into her at the grocery store. She looked older, smaller, diminished by regret. She spotted me, froze, then whispered, “How is she?”

I considered lying. But the truth was better. “She’s thriving. Strong. Happy.”

Tears filled her eyes. “Does she ever… ask about me?”

“Not anymore,” I said gently. “She’s moved on. We both have.”

She nodded, lips trembling. “I’m glad,” she whispered. And then she turned and walked away, out of the aisle, out of my life forever.

Years later still, Lily stood at the front of a small church, her veil trembling with the same nervous excitement I’d once seen when she kicked her first soccer ball. She looked radiant, unbroken, a woman who had clawed joy from the jaws of betrayal.

When the pastor asked who gave this woman away, I said, “I do,” my voice cracking. As I placed her hand into her husband’s, I whispered, “Never leave her out in the cold.”

He nodded, eyes wet. “Never.”

And in that moment, I finally let the weight of the past drop from my shoulders. Completely. Finally. Forever.

Now, years after that Christmas Eve, I sit in a quiet house, watching the snow fall. Lily visits often, sometimes with her children. She brings laughter, warmth, chaos, life. My home is full. My heart is whole.

And yet, sometimes, when the air turns knife-sharp and the thermometer dips near freezing, I step onto the porch. I see again the small figure shivering, the pale lips, the desperate clutch. I hear the laughter from inside, the cork popping, the music, the betrayal.

And I remember the six words that ended it all:

You left her out to die.

That night destroyed a marriage, but it saved a child. It gave me clarity. It gave Lily the truth: love is not champagne and lies. Love is warmth. Love is presence. Love is never leaving someone in the cold.

The doorway where she froze is gone now—the house sold long ago. But in my memory, it stands forever, a monument to the choice I made. To kick the door. To carry her inside. To never go back.

Love doesn’t survive neglect. It doesn’t survive betrayal.

But it survives in the arms of a father who refuses to let go.

That’s the ending.

Not sorrow.

Not revenge.

Just love. Safe, warm, alive.

✅ THE END

News

My Husband Poured Hot Coffee on My Head in Front of His Mother and Our Son for Refusing to Pay for CH2

Part I I still have the receipt from the night I should’ve known better—curled thermal paper, $8 Uber to a…

Rich Wife Hid A Camera To Catch Her Husband With The Maid… But What She Saw Shattered Her World. CH2

Part I The receipt was not much to look at—cheap thermal paper curled like a leaf left too close to…

I Thought Letting My Ex See the Baby First Was Sweet — Now My Husband Walked Out on Me at the Hospit CH2

Part I The day we argued in the nursery, the paint was still tacky on the baseboards and the crib…

My fiancé recoiled when I mentioned morning sickness at our baby shower and loudly announced… CH2

Part I I used to think gift wrap solved everything. It made chaos pretty. It turned a tangle of receipts…

My parents called my son a LOSER and banned him from Christmas… CH2

Part I I was making lists—the kind you make in December when you’re trying to pretend the holidays are logistics…

Locked in a hot storage by husband & MIL. Hospital called: “They’re dead.” But what I saw there… CH2

The Decision That Wasn’t Mine The day my life got small started with a sentence that sounded like a favor…

End of content

No more pages to load