If you’ve ever felt a building breathe, you know it happens in hospitals at 2 a.m.—the vents sigh, the automatic doors exhale and inhale, a hundred machines harmonize in quiet beeps and huffs. Seattle Children’s smells like lemon disinfectant and a fear that’s tried very hard to be cleaned up and can’t quite be. My boots squeaked on polished floors Joe had warned me were “a little slick” as she led me down a corridor lined with rooms full of small bodies plugged into machines that are supposed to impersonate miracles.

“He’s been here three days,” she said. “Severe asthma attack. We almost lost him.”

She stopped outside room 314. Through the glass, my son looked smaller than the memory I’d been nursing in Thailand for the last five years—a boy with tubes in his nose and taped to his mouth, a bouquet of lines running to monitors that blue-lit his face and made his skin look gray. In one of his forearms, beneath the tape, I could see a bruise that wasn’t from this room. There were older ones; your eye knows the difference when you’ve gone too long pretending you don’t.

“Can I go in?” I asked.

“Of course,” Joe said, voice steady from the kind of steadiness you only learn by having spent too much of your life in rooms like this. “You’re his father.”

I pushed through the door, moved the chair close enough that I could have whispered if whispering would have done anything, and took his hand. Warm, too thin—the bones taking attendance under the skin. He didn’t move. The ventilator kept the rhythm.

“There were signs of malnourishment,” Joe said, not looking away from the monitors. “Bruises that predate admission. He hasn’t seen his pediatrician since March. His inhaler prescription ran out in April and was never refilled.”

I stared at the boy who used to talk my ear off about orcas and salinity, who had sat cross-legged on a living room floor and built a perfectly scaled SeaTac runway out of Legos and insisted the planes taxi correctly. “What triggered it?”

“A neighbor found him collapsed on your front porch. He’d been outside for hours—apparently trying to get back inside. She said she’s seen him wandering around the neighborhood alone several times recently.”

“Alone,” I repeated, the word calcifying into something else inside my mouth.

“Mrs. Patterson—two houses down. She’s the one who called the ambulance,” Joe went on. “We’ve been trying to reach Delaney since he was admitted. Her emergency contact information is outdated. The address she gave is a P.O. box that’s been closed for months.”

“Where’s Delaney?” I asked, though I knew. Not where. Who.

Joe pulled her phone from her scrub pocket and swiped. “This is from yesterday.” She handed it to me. The photo showed my front door flanked by takeout containers haloed with grease, empty bottles tipped like soldiers after a battle, newspapers yellowed in the driveway. The lawn had gone from “we should mow” to “we might need a scythe.”

“How long?” I asked. “How long was he alone?”

“We don’t know,” Joe said. “But the doctors are required to report suspected neglect. Child Protective Services is investigating. Sawyer hasn’t had a refill in months; he’s underweight. These are not…it’s not new.”

I touched his hair. It was longer than I remembered, oily at the roots. Dusty. “When will he wake up?”

“Soon,” she said, and in that word, the entire floor held its breath then let it out. “His vitals are stable. The medication’s helping. But when he does, he’s going to need more than breathing treatments. This kind of thing—” she gestured at the lines, the room, everything “—leaves marks X-rays don’t catch.”

She set a business card on the tray table, beside a stack of sanitary wipes and an unopened juice. “This is Avery Redden—CPS. Call her. Tonight, Russ. Don’t wait.”

Joe’s footsteps receded down the hall, her squeaks absorbed into the soft machine symphony. I pulled the chair closer and wrapped both of my hands around Sawyer’s. “You don’t have to worry anymore,” I whispered. “Dad’s here. And I’m never leaving again.”

At 2 a.m., the hospital cafeteria is a brightly lit proof that nothing makes sense. Vending machines hum. A television with the volume off scrolls headlines only night people read. I opened my laptop on the plastic table and did the thing I’d learned to do for five years laying PVC and coaxing pumps to life in villages with no maps: gather inputs.

Delaney’s Instagram was public. Of course it was. The grid started out innocuous—coffee, a sunrise, a dog she walked twice during the pandemic and never posted again. Then Bali. Designer luggage clicked into a black car at SeaTac, her mother beside her in large sunglasses, both smiling as if the universe owed them better lighting.

June 15: Mother–daughter adventure! Bali bound. #livinglife #blessed

June 16: Poolside cocktails, Delaney in a bikini laughing up at the drone. #selfcare #balivibes

June 17: Spa day—two women with cucumber slices on their eyes, feet in some kind of gold bowl. #treatment

June 18: Sunrise yoga. Grateful for this moment of peace. Sometimes you have to choose yourself. The timestamp made my stomach go silent. 6:47 a.m. Bali time. 2:47 p.m. Seattle. An hour before Mrs. Patterson found my son folded on the porch.

I screenshotted everything. Every caption, every timestamp, every casual namaste. Loretta’s profile—Delaney’s mother—was the same paradise through cheaper filters. #girlsweek. #pouritup. In the comments, friends asked the questions they thought made them look kind. Where’s Sawyer? Don’t you miss him? Delaney’s responses were master classes in deflection—He’s with his dad (I’d been in Thailand with no cell service for three straight weeks), He’s at camp (it was June 15 and he had never been to any kind of camp), He’s having his own adventure (it involved expired asthma medication and an empty pantry).

A man I didn’t recognize appeared in multiple frames: younger than Delaney, an ambitious jaw, shirts the color of cocktail names. His hand on her waist in one photo, his mouth almost on hers in a boomerang labeled #lovehim. His name was in the tags: Brilan Curt. I clicked and found a LinkedIn full of jargon and a public Facebook where he posted quotes about hustle and a bio that included the word “disruptor.” In between were photos with Delaney no one had thought to make private.

I dumped it all into a cloud folder labeled EVIDENCE like a charm and made three backups. If living in countries with multiple alphabets taught me anything, it’s that truth can get lost in translation unless you nail it to a server.

As I was closing the laptop, my phone buzzed.

Unknown: This is Avery Redden, CPS. Got your message. Family conference room on the pediatric floor at 8 a.m.?

Me: I’ll be there. I have information you need to see.

I went back to 314. The night nurse—Patricia—glanced at me, then at my son, then back at me with the exact amount of warmth Seattle allows after midnight. “Breathing’s better,” she said. “Doctor thinks we might get lucky tomorrow.”

I slid into the reclining chair and watched a boy who’d been coloring maps of the Puget Sound bays during our calls sleep in a city that had forgotten his address. I have loved a lot of things in my life, some poorly, some too late. The only feeling I’ve ever recognized as sacred is the one I had in that chair: an entire body condensing around a vow.

I had an appointment with a lawyer at 7 a.m. because the worst days of your life don’t care about office hours. The building was glass and steel and had the subtle intimidation of a place that sells you the consequence you want. The name on the frosted door read MARKEEL FINN, and it turned out to belong to a man who looked like he slept in his office and enjoyed it.

“Show me what you’ve got,” he said, sitting, coffee already steaming.

I spread the screenshots and printouts and the hospital paperwork and the Seattle Municipal Code I’d downloaded onto his mahogany.

He flipped through the private Bali and the public neglect like he’d been expecting both his whole career. “This is bad.”

“It gets worse,” I said, handing him bank statements. “Fifteen thousand in thirty days on flights and restaurants and shirts with adjectives. From our joint accounts.” I tapped on circled charges. “While my son rationed granola bars.”

Markeel leaned back and steepled his fingers the way people do when they are about to change your life. “What do you want to do?”

“Everything,” I said. “Cut her off. Full custody. Criminal charges.”

“The financial piece we can do today,” he said, already opening his laptop. “Emergency motion to freeze the joint accounts and assets. Given these circumstances? Any judge with a pulse will grant it. The freeze will be effective immediately.” He glanced up. “Custody runs through CPS, through a judge in family court—work with them. As for criminal—our D.A. is not shy.”

“I’m meeting CPS at eight,” I said. “I’ll bring copies.”

He stood and offered a hand. His grip was the right combination of force and sympathy. “Welcome home,” he said. “I’m sorry it’s under these circumstances.”

“I’m sorry I left,” I said, and watched that land nowhere and everywhere at once.

The family conference room was painted the color of deliberate neutrality. A woman in her thirties whose hair told me she had decided years ago not to perform for anyone shook my hand. “Mr. Kesler, I’m Avery,” she said. “I’m sorry we’re meeting like this.”

“Me too,” I said, and set the folder down, and watched her mouth tighten as she recognized the picture it was about to draw.

“Why did you leave?” she asked finally, the question I deserved to be asked.

“I thought I was being a good father,” I said. “Delaney asked for the divorce. She said primary custody would mean stability and routine. I—the work needed me over there. I told myself I would make up for it.”

“Did you maintain contact?”

“Video calls,” I said. “Twice a week, unless she said he was busy. Which was a lot lately.”

“When was your last call with Sawyer?”

“March. Maybe April.”

Avery nodded and made a note that looked like a nail going into a board. “Mr. Kesler, this is one of the most clear-cut neglect cases I’ve seen in ten years. We’re recommending immediate removal from the mother’s custody. Given you’re biological and present, placement with you is preferable to foster care. We’ll need proof you can provide stable housing, income, medical insurance.”

I slid another folder across the table. “Employment offer,” I said. “Boeing, Senior Engineer. I start Monday. Salary, benefits, insurance here. Background check. I’m in the family home for now—new locks today, full cleaning tomorrow, security system this week. Then we find somewhere with space for Legos and an air filter that hums.”

Avery studied me for a long second. “Channel the anger,” she said. “Don’t spend it.”

“I know,” I said. “But I have five years’ worth of receipts that say otherwise.”

Delaney called at 3:47 p.m., Bali air audible, the exact tone I’d heard the day she found a scratch on the car and called it a gouge.

“Where are you?” she screamed before I could say hello. “What did you do to my accounts? I can’t access anything.”

“Hello to you too,” I said.

“Don’t you take that tone with me. I’m stuck in Bali with no money because of whatever sick game you’re playing. Where’s Sawyer?”

“He’s in the ICU,” I said. “At Seattle Children’s.”

Silence. Then: “What?”

“He nearly died three days ago from an asthma attack. The same three days you’ve been posting bikini photos.”

“That’s impossible,” she said. “He was fine when I—”

“When you what? When you left? When you boarded with your mother and your boyfriend and posted #selfcare?”

I could hear something collapsing in her mind—either the lie or the plan. “I didn’t leave him alone,” she said finally, falling back on the nearest ledge. “He was staying with—”

“With who?”

“You don’t get to interrogate me!” she shouted. “You left us.”

“Room 314,” I said. “Seattle Children’s. Go see for yourself—oh wait.”

“The accounts,” she said, crying now—the kind of dramatic sob that used to make me throw money at problems. “You can’t just—”

“I can and I did.”

“I made a mistake,” she said, switching to a new costume without changing outfits. “But I’m his mother.”

“You’re a stranger who happened to give birth to him,” I said. “A mother doesn’t leave her child to die.”

She hung up. I stared at my phone until it turned back into a brick, then called Markeel.

“She called,” I said. “Panicked about the money. Tried to lie about Sawyer. Caught herself.”

“Fine,” he said. “We have enough without a confession. He wake up yet?”

“Any minute now.”

“Document everything,” he said. “Psychologists call it trauma narrative. Judges call it testimony.”

He woke up at 6:23 a.m. on June 21st, eyes trying to focus on unfamiliar light, body remembering and forgetting in waves. “Dad?” he whispered, and nowhere in my life did any sound ever do more work than that syllable.

“Hey, buddy,” I said. “I’m here.”

He tried to sit up. The tubes and tape and wires and pain said no. “Where am I?”

“The hospital,” I said. “You had an asthma attack.”

“I couldn’t breathe,” he said, his little hand trying to mimic something his lungs had almost forgotten. “I tried to get inside. The door was locked.”

“You’re safe now.”

He ate scrambled eggs in careful bites while I asked questions soft enough not to bruise him any more than everything else already had. He’d been alone. He’d stretched peanut butter and crackers. He’d saved granola bars in a basket under the sink for when his stomach growled too loud. He’d gone to Mrs. Patterson’s porch for juice. He’d been told to stay in his room when “Brilan” came over.

“Does he talk to you?” I asked.

“He doesn’t like kids,” he said, which is something in a city of three million people I will never forgive.

After he fell asleep, I met Avery again. This time she brought Detective Linda Vasquez, who looked like the kind of woman you want in your corner during a fight. She asked me questions I answered with folders. Then she showed me her own.

“Your wife and her boyfriend return tomorrow,” she said. “We’ll meet them at baggage claim.”

“What happens then?”

“Arrest. Booking. Arraignment. Given what we have?” She raised an eyebrow. “We’ll ask for no bail. Then we’ll do our jobs.”

I thought of Delaney’s yoga photo. #chooseyourself. “Good,” I said, and meant it.

The arraignment was a morning where justice borrowed the tone of bureaucracy and somehow made it work. They brought Delaney in wearing orange; orange is not her color; it did not matter. When the judge asked the state’s position on bail, the prosecutor—a woman named Nina who had an entire building of men shrunk into a polite hush—stood and talked about flights and luxury and a ten-year-old in an ICU bed. The public defender tried to say “miscommunication,” because men always make that the last refuge of certain kinds of women. The judge banged the gavel like a period.

No bail.

Delaney turned in the aisle to look for me like there’d be a cliff I could fall off of if she pushed with her eyes. I sat still and watched her be led away. People can say “I hate you” without speaking, and sometimes that’s the only sentence they’ve ever been honest about.

Family court looks like a church basement most days—papers, a coffee maker that will never be washed properly, a judge whose voice is the only voice that matters. Rebecca Morrison, the family lawyer Markeel recommended for “when the other side is rich but inconsistent,” laid out our file like a woman setting a table, and Judge Barbara Chin—who looked like she had no patience for a woman who would let a child unlearn how to trust—ate the meal we’d prepared.

Full legal and physical custody to me. Effective immediately. Termination of Delaney’s parental rights. A restraining order. I did not cry. I did not feel triumph. I felt my body stop shaking.

The trial—State v. Von Kesler—happened because Nina decided it should and because the jury refused to pretend. Mrs. Patterson brought her notebook. Dr. Chin brought the timeline and her voice. Joe brought the kind of testimony people believe because they’ve watched nurses be better people their whole lives. Avery brought CPS’s adjectives. Detective Vasquez brought the numbers. $43,000 in six weeks. The photos did the rest—bikini and ventilator, side by side, in a courtroom where everyone had the decency to accept that sometimes a picture is exactly as bad as it looks.

The defense searched for a babysitter who had never existed. They tried my absence as a cudgel; the jury looked at my son and looked away.

Guilty. Guilty. Guilty.

Nine years. Parole in five if the system decides to believe in her again. I did not clap. We bought a book about coral reefs on the way home.

Loretta found us once at a park, the water bright, my son on monkey bars he had decided fear would not own. She looked old, not just the kind of old you get in jail booking photos but the kind you get when you realize people saw you. She asked for the right that had died on a boarding pass: to be a grandmother again.

“No,” I said. “You were in every picture that proved my son learned to ration food.”

“I didn’t know,” she said.

“You knew,” I said. “You just didn’t want to have to do anything brave.”

Sawyer waved from the third rung. “Dad! Watch me!” I watched him and did not look back at Loretta, and that was the justice that mattered.

A year later, we stood in a house on a bluff where the air smelled like salt and hope. We installed an air filtration system in a room with a view, and my son tightened screws with a competence that had nothing to do with me and everything to do with the part of him that had built Lego runways. He eats eggs every morning now. He laughs in the middle of sentences. He asks me questions like the world owes him answers and I love him for the audacity.

Sometimes he asks about his mother. I say I don’t know and that we are safe. Someday I will say more. He doesn’t need the why today. He needs the who. He has that.

On Tuesday nights, we have dinner with Joe because nurses like to be fed by families that learned the lesson. The foundation I started in my mother-in-law’s name teaches women how to file binders with tabs that say BANK and HOUSE and WORK because sometimes the difference between “neglect” and “saved” is a binder and the right name to write on the tab. The first time one of our clinic women texted me a picture of her banister light like she’d learned to notice the way a house blesses you back, I cried in the bathroom at the community center and didn’t apologize to anyone.

Sometimes the phone buzzes with a message from Markeel: Parole hearing scheduled. I delete it. She is a stranger now. If a judge wants to listen to her tell a new story, that judge can. It’s not my job to edit it, finally.

We installed a lighthouse puzzle on the dining room wall in a frame. The beam cuts through a storm like the artist had learned a thing about how light works in Seattle that no one else had figured out yet. Sawyer found the last piece in a sock. He told me he put it there so he wouldn’t lose it.

“Like insurance,” he said, grinning.

I want to tell him that insurance is what you buy when you don’t trust the world. Instead, I say, “Exactly,” because I want him to know he makes sense.

At night, we stand on the deck and watch the city throw light at the water and the water refuse it with grace. “Do you think Mom will ever come back?” he asked once, eyes on the ferry.

“I don’t know,” I said. “But I know I’m here.”

He leaned into me.

The house hummed—the air filter, the fridge, the sluggish clock. Safe, stable, the world’s most radical adjectives. The banister at the top of the stairs shone, worn smooth by hands that had stopped shaking.

This is the part where people expect you to be profound. I don’t have it in me tonight. I have a kid who wants ice cream, an air filter that makes a sound like a cat purring, a nurse who brings brownies, a prosecutor’s email I don’t have to answer. I have a city that forgave me for leaving by letting me come back and be useful.

I have tonight. I have Tuesday. I have the rest of my life learning that fatherhood isn’t penance; it’s presence.

The ferry sounded its horn. Sawyer reached for my hand as if he’d always known where it would be.

We went inside. The house breathed. We breathed with it. And for the first time in a long time, that was the end of the story I needed.

A year after the trial, the ferry’s horn had become the metronome of our evenings. It blew low and certain as it cut across the Sound, the lights of the city braided across the water like a promise someone remembered to keep. Tuesday still meant brownies and binders; Thursday still meant Lego and albuterol; the hum in the corner of Sawyer’s room still meant the air was cleaner than it used to be.

On an ordinary Tuesday in April, Sawyer slid off the bench at the kitchen table with a scientist’s seriousness and an eleven-year-old’s clatter. “Dad,” he said, notebook under one arm, “I need your eyes.”

He led me up the stairs to his room where the volcano he’d built for the science fair loomed on a foam-board island. The air filter purred; the model mountain was wired to belch baking soda and vinegar on command. He’d named it after a real one because he believed in accuracy and awe in equal measure.

“Evacuation route needs a second option,” he said, pointing to a chalked path that led from a paper town along a ridge. “Mrs. Patel says good plans have backups.”

He looked so much like the six-year-old who used to explain Lego runways to me that my chest hiccuped. “Then we put in a second route,” I said. “We can’t count on one road any more than we can count on one inhaler. Or one grown-up.”

He held my gaze for a beat, and then nodded, the way boys do when they add a new truth to the list they’re compiling in silence. He traced a second path with a pencil, then pressed a mark into the foam. “Lighthouse goes here,” he said. “Just for the look of it.”

“Function and beauty,” I said. “Your grandmother would approve.”

Downstairs, Joe banged a cabinet with the easy familiarity of someone who no longer asks where things live. She’d started coming by on Tuesdays the week after Sawyer came home from the hospital—first as a nurse checking vitals and watching for fear in his shoulders, then as a person who made a point of being in rooms where children learned to trust warm voices. We’d become a tribe, the three of us, though we never tried to name it. Naming things the wrong way before they’re ready is how you ruin them.

“Dinner in ten,” she called up the stairs. “Don’t let the vinegar explode on its own or you’re both doing dishes.”

“Copy,” Sawyer answered, and then whispered to me, “She always says that.”

“Because she’s always right,” I whispered back. Then, without meaning to, “Call your grandmother.”

I meant my mother—the other one, the one who’d shipped me survival skills baked into casseroles long before there was a courthouse in my future. We FaceTimed her on Sundays but I found myself reaching for her voice on Tuesdays when the house was clean and the air was kind and my body remembered where the panic used to sit and was surprised not to find it.

We ate spaghetti, because ritual isn’t superstition if it feeds you. Sawyer talked with sauce on his mouth about the petri dish in biology, how the bacteria made tiny constellations he wanted to name. He asked Joe if she thought Mount St. Helens had felt relief when it finally blew. Joe said relief felt like a word you earn, not a word you expect from mountains. She looked at me when she said it and smiled.

After dinner, Sawyer spread his homework across the table. Joe and I fell into our now-familiar division of labor—she did fractions; I signed permission slips and made a note to pick up more inhaler refills on Friday even though we had a calendar reminder because preparedness ruins no one’s day. He was halfway through a geography worksheet about the Pacific Rim when my phone buzzed with a number I didn’t recognize but a cadence I did.

“This is the Washington State Board of Parole and Pardons,” the voice said. “Notifying you of an upcoming hearing regarding Inmate Von Kesler. Attendance is not required; statements may be submitted in writing.”

I didn’t ask for the date. I didn’t need it to be in my phone. “Thank you,” I said, and ended the call. Joe’s eyes were on me. I shook my head. “Nothing we need to carry tonight.”

“Nothing we need to carry tonight,” she repeated, and the way she said we made something loosen in my ribs.

Later, after homework and after the air filter hum became part of the lullaby and after the lights of the city settled into their steady blink, I sat at the dining table with a pen and the legal pad the foundation uses for clinic notes. I wrote a paragraph to the Board that did not mention revenge. I wrote about an eleven-year-old boy who checks doors by habit and laughs again because doors have stayed open for a year. I wrote that the work of trust is slow, that the scars X-rays can’t catch take longest to fade, that a mother’s return cannot be what heals him. I asked them to leave our ordinary undisturbed. I signed my name and folded the paper and put it in an envelope.

Then I slid the envelope under the binder marked HOUSE & FAMILY in the drawer where our warranties live, because some things don’t need to go to the mailbox right away.

The foundation’s clinic was full the night we built three binders in fifteen minutes. The fluorescent light buzzed because the ballast was going, but the women didn’t seem to hear it; the hum of bodies preparing to leave felt louder. Fatima handed out cookies because someone had remembered that sugar makes truth easier to digest.

A woman named Kendra stood in the doorway and looked like every wrong kind of movie cliché—stringy hair, sweatshirt with a stain on the cuff, eyes that said she had been told too often no one would believe her. She clutched the strap of her purse like the banister on a stairway with missing treads.

“Come in,” I said. “Take a breath.”

She sat. Fatima slid a pen across the table. “Write what you want on the first page,” she said. “Not what you don’t want. Not what you’re scared of. What you want.”

Kendra stared at the blue lines and then began to write. I want to sleep through the night without listening for a car. Then: I want to take a shower without checking the lock twice. Then: I want my kid to stop thinking whispering is safer.

“Good,” I said. “Now bank statements.”

She handed me a stack she’d printed in secret at work. We circled the same old proofs—small withdrawals just below the monitoring threshold, a rent payment missed “by accident,” the Costco receipts for junk and none for rice. Evidence can be a beating if you’re not careful. We treated it like a set of stairs.

“My mother says this is between us,” she said. “She says it’s disrespectful to involve strangers.”

“She’s wrong,” I said. “Tell her from me.”

Fatima wrote CPS and a phone number on a sticky note. I wrote the name of a shelter on a second. We put them both in the front pocket of a binder labeled like a life.

“You’re very calm,” Kendra said.

“I am not,” I said. “I just learned where to put the yelling.”

The clinic broke up at nine. Women tucked binders under coats and into totes like talismans and left, not dramatic, the way decisions look when made by someone who’s done with only surviving. I locked the door and turned off the fluorescent hum and stood in the quiet.

“What?” Fatima asked, watching my face.

“I was thinking about a lighthouse,” I said. “And who built it. They never get to see all the storms they keep people from.”

“Come off it,” she said, smiling. “You like storms.”

“Not anymore,” I said, and surprised us both by meaning it.

Two weeks later, Mrs. Patterson sat on our deck with her hands folded and her back as straight as a ruler, and watched Sawyer ride a bike he’d earned with a summer’s worth of odd jobs and breathing treatments. The woman who had left juice boxes on her porch for a boy she didn’t know had become part of a calendar that made us legitimate.

“Why do you make me tea like I’m somebody, Russ?” she asked, accepting a mug.

“Because you saved my son,” I said.

She looked at Sawyer wobbling at the end of the driveway and blinked hard. “I called too late,” she said. “And I’ll always know that.”

“You called,” I said. “The rest of us built better systems because of it.”

She nodded like the sentence had been waiting for someone to write it down.

“Dad!” Sawyer yelled. “Watch!”

“Always,” I said.

If the parole hearing was a test, we passed what we needed to. The Board sent a letter—deliberate, bureaucratic, mercifully brief—denying release. The panel finds continued incarceration warranted given the seriousness of the offenses and lack of demonstrated sustained rehabilitation. I put the letter in the binder under the tab labeled LEGAL and folded my life back into Tuesday.

In October, Brilan shaved his hair and grew a beard and tried to buy groceries at the market we use because the owner keeps the good bread behind the counter. I saw him before he saw me. He saw me and flinched anyway.

“Mr. Kesler,” he said. “I’m—”

I held up a hand. “No.”

“I didn’t know,” he started, rehearsed, a script he’d been trying on in mirrors.

“You knew,” I said, soft enough that the man behind him in line wouldn’t hear. “You knew enough. And you chose silence. Do your penance without my attention.”

He nodded, too quickly. “I’m—”

“Don’t finish that sentence,” I said. “It’s worthless to me.”

He paid for his bread. He left. I bought the good loaf and walked home with my son’s hand in mine. “Who was that?” Sawyer asked.

“No one we need to carry,” I said.

We put the bread on the table and ate grilled cheese while the air filter hummed and the Sound threw back the city’s light and the house learned, again, how to hold us with both hands.

On a gray Saturday that smelled like rain and laundry, I took Sawyer to the museum for a talk on orcas. He’d been circling marine biology since he could pronounce “echolocation.” He sat in the front row and asked three excellent questions. He took notes. He didn’t look back at me once. I loved him for that.

On the way out, we took the long way through the halls and stumbled on an exhibit about lighthouses. He leaned into the glass, tracing the drawings with his finger as if he could feel the original pencil ridges through two panes and time. “Dad,” he said, “who decided where to put them?”

“People who looked at maps and storms and decided where light would be most useful,” I said.

He nodded like the answer satisfied him. “Can we build one?” he asked later in the car, eyes already on the Lego pallet he’d left on the floor of his room.

“We already did,” I said. “You just didn’t know what to call it yet.”

He fell asleep on the couch that night with the museum brochure on his chest, the lighthouse page dog-eared, the house breathing around him like forgiveness. I sat in the chair by the window with a cup of tea and watched the lights across the Sound flicker. The ferry called in, three long, one short. Out on the water, a real light turned in slow, stubborn circles.

When my phone buzzed with a message from an unknown number—I forgive you for taking him from me—I didn’t reply. I deleted it. I put the phone face down so the screen could not confuse me. Then I stood and turned off the light and climbed the stairs and ran my hand along the banister that had been there before me and would be there after, smooth by touch, steady as the kind of love you choose daily.

At the landing window, the sound changed—wind coming in, tide turning, my son’s soft child snores from the room at the end of the hall. The lighthouse on the dining room wall cut its painted beam through a painted storm, doing exactly what it had been hung to do. I smiled. Not triumph. Relief.

The next morning, Sunday light found the second evacuation route we’d drawn on his volcano island and the lighthouse sticker he’d placed at the highest point, function and beauty, because he’d decided to believe in both. We ate pancakes because Saturday had been long and forgiveness works better with syrup. At church, Mrs. Patterson pressed a bulletin with too many typos into my hand and told me she’d signed up for Thursday night at the clinic to bring cookies and listen quietly in the corner. Joe met us for lunch and asked Sawyer to explain orca pods. He did, with hand gestures and sound effects.

That afternoon, as the Sound threw up its small chop and the ferry horn announced and the house did its breathing and the air filter hummed like a content cat, my son looked up from his Lego lighthouse and said, “Dad, thanks for coming home.”

“You’re welcome,” I said, and meant it like a man who understood the difference between guilt and presence. Then I reached for a handful of bricks, because some things you make, you have to make together.

News

“We Left My Stupid Husband Miles AWAY From Home as a JOKE, But When He Returned It Was NOT Funny…” CH2

Part I I can tell you the exact moment I should have trusted my gut. It wasn’t the tight smile…

Sister Announced She Was Pregnant With My Husband’s Baby at My Birthday—She Didn’t Know About the Prenup CH2

Part I The florist had crammed the hotel ballroom with white roses because “thirty deserves a thousand blooms,” according to…

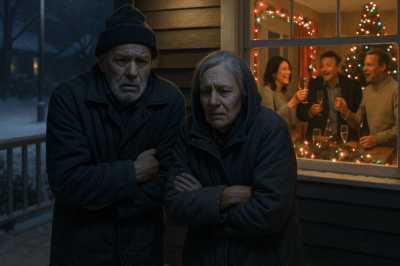

I Found My Parents Locked Out With Blue Lips While My In-Laws Partied Inside…So I Made Them Pay CH2

Part I — When Help Knocks and the Locks Change Robert said it like he was reporting the weather. “My…

Parents Chose a Vegas Poker Party Over My Surgery — My 3 Kids Left Alone, and I Finally Cut Them Off CH2

Part I: The Line in the Doorframe I told the bank we were done. That was the sentence that cut…

WRONGFULLY JAILED FOR 2 YEARS – NOW I’M FREE, BUT EVERYTHING I BUILT IS GONE CH2

Part One: The Strip-Mall Law Two years of my life were stolen because I was walking home from school. That’s…

Black Nurse Insulted by Doctor, Turns Out She’s the Chief of Surgery CH2

Part One: Night Shift The night shift in the emergency department had a sound all its own—a layered hum of…

End of content

No more pages to load