Part I

If you’d asked me to name the moment my marriage cracked, I’d say it wasn’t big. Not the kind of moment that makes a movie trailer. It was quiet and stupid—Kevin clicking his tongue at his older brother’s wife at Sunday dinner.

“Maria,” he said, swirling the last of his wine like it might reward him for trying, “now that is a woman. Brains. Drive. Not like some people.”

He didn’t look at me when he said it. He didn’t have to. Maria’s smile froze. Mike set his fork down like a gavel. Even my father-in-law, who preferred to preach by example and payroll, stopped mid-chew.

“Kevin,” Maria said, voice level, “Ashley is my sister, too. Don’t insult her to compliment me.”

Mike nodded. “Before you compare anyone, start with a mirror.”

Kevin rolled his eyes. “Spare me,” he muttered, the boy he still was peeking through a man’s shirt. He had that click in his mouth he used when life didn’t bend for him—like scolding a dog for barking at thunder.

My father-in-law cleared his throat. He wasn’t a dramatic man. Numbers had trained him that drama rarely balanced. “Have you no shame?” he asked, tone even as a ledger. “Relying on Ashley’s family wealth, shirking your responsibilities. Ashley is a devoted wife. Be a husband. Stand on your own feet. It is a simple concept.”

Kevin’s face flared. “Dad, Ashley is useless. A burden. I’m just returning the favor.”

Mike stiffened. “As your brother, I’m compelled to tell you: your mindset is toxic.”

The room held its breath. I waited for Kevin to blow. Instead, he cursed, shoved his chair back so hard it scraped guilt into the hardwood, and stormed out the side door. The night swallowed him. The porch light stayed dark.

I stood to follow, instinct braided with shame, but my father-in-law’s worn palm found my wrist. “I’m sorry, Ashley,” he said, eyes tired. “I hoped marriage would teach him responsibility. It seems it hasn’t.”

Maria pressed a warm hand between my shoulder blades. “Don’t worry,” she murmured. “We’ve already made some arrangements.”

Arrangements. My stomach sank with both dread and relief.

I left their house with a hug and a pie Maria insisted I take—because in our family you never leave empty-handed, even when everything else feels that way—and walked into my own front door to find a storm.

Kevin had a gift for mess. Bottles sweating rings on the table. A lamp tilted at an accusatory angle. Our wedding photo—the one where we look like a promise—face down on the credenza.

“I’m divorcing you, the barren one!” he shouted the second he saw me, the brandy in his hand giving him all the courage he never drank sober. “Emily will be my new wife.”

For a second, my brain refused to supply definitions. My sister, Emily, wears mascara like a costume and apologies like jewelry. My parents had spent my whole life smoothing her bedsheets and her troubles. They’d always said she deserved the “best.” Apparently, best now meant my husband.

“So it’s true,” I said, voice small in my own mouth.

“Your parents already agreed,” he crowed, triumphant in the way only a fool can be, as if agreements made in whispers turn into vows when shouted in living rooms. “They want a grandchild. Emily can give me one.”

A different woman might have thrown the pie. I put it in the fridge. There’s only so much waste a person can tolerate in one night.

“You knew I couldn’t conceive when you married me,” I said. I did not say: you let me carry that shame like a backpack full of rocks while you enjoyed a free hand.

His jaw squared. “You were convenient.”

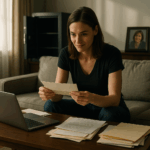

There are words that knock your breath out. You don’t even feel the punch until later, when you’re standing in the shower and notice your ribs bloom purple. I went into our bedroom, folded three blouses with hands that wanted to shake, and slid my grandmother’s locket into the pocket of my coat. At the kitchen counter, I signed the papers he had printed with smug efficiency and pushed toward me as if I were signing for a package.

“Get out,” he said, already pocketing a victory he thought he won. “I’ll pay you… something.”

We both knew whose bank accounts would do the paying. I left the severance check from my parents on the counter, untouched, like a dare. I wouldn’t cash their pity. Not anymore.

I drove to the apartment Mike and Maria had ready in a complex owned by her interior design firm—company housing with soft carpets and a kitchen with a window over the sink. Their shy son peered around the doorway as I wheeled my suitcase in. He looked like both of them and neither, eyes curious, body ready to bolt.

“Hi, buddy,” I said, crouching. He held my gaze for three brave seconds, then retreated behind Maria’s legs.

“We’ll get dinner,” Mike said, already reaching for his phone. “No arguments.”

“We made a plan,” Maria said. “Start with a bed and a lock and a job. You’ll be on your feet in weeks. Steven will train you.”

“Steven?” I asked.

She smiled. “You’ll see.”

The next morning I woke to a room that didn’t smell like sour brandy and apologies. I sat at the small table, hands wrapped around a mug, and cried so quietly the walls didn’t hear me. Then I got up, washed my face, and put on shoes that could stand for a whole day.

Maria’s firm felt like a door that someone had propped open just for me. It was all brushed steel and cheerful plants and scraps of fabric pinned to boards like birds you couldn’t bear to release. The man at the front desk looked up as if he’d been waiting.

“You must be Ashley,” he said. His grin was easy as denim. “I’m Steven. I’ll show you where the coffee is before I tell you anything else that matters.”

He did, then handed me a stack of folders and walked me through the software in a voice that didn’t assume I was an idiot. He was…the kind of man you forget to brace for because nothing in his posture suggests you should.

At noon, while the office buzzed around us, I rolled up my sleeves and started cleaning. Dust kills inspiration, Maria always says, and it was the one thing I knew how to fix without instructions. Steven came in from a site visit and stopped short.

“Wow,” he said, looking around like the room had cut its hair. “This looks amazing.”

“I’m sorry,” I said quickly. “I should have asked. I didn’t mean to—”

He tilted his head. “Why are you apologizing for making things better? We’re equals here. We work together.”

Equals. The word sat on my tongue like a piece of candy I wasn’t sure I was allowed to swallow. I had been nobody’s equal for a long time—my parents’ project, my husband’s convenience. Steven said it like a fact. I tucked it away.

A few days later, Maria swept in earlier than usual, sunglasses perched on her head, actual sunshine following her into reception. She took one look at Steven and me, side by side at the worktable, and her mouth twitched.

“Steven,” she said, teasing threaded into her tone, “have you finally gotten to know Ashley better?”

Steven flushed a color so sudden it warmed the room. “Director,” he hissed, leaning in as if they shared a script, “we agreed you would not say anything.”

He fled toward the break room. Maria slapped my shoulder like a coach proud of a rookie. “What?” I said, genuinely confused.

She leaned in. “He’s been wanting to speak with you alone since the day you started. He just needed a hallway without witnesses.”

My cheeks burned like a teenager’s. “Maria…”

“He’s a gentleman,” she said, answer to questions I hadn’t yet allowed myself to ask. “And since we’re on the subject of worth you’ve been taught to weigh wrong—do you know our son isn’t ours?”

I blinked. “I—what?”

“He’s a relative’s boy,” she said softly. “His parents died in an accident. We said we didn’t know how, but we’d try. The first time he called us Mom and Dad, I cried so hard I burned dinner.”

I felt the burn of tears behind my eyes that didn’t belong to grief. “I didn’t know.”

“That’s the point,” she said, tipping her head to the side and giving me that look she uses when she’s about to say a thing I will tuck into my bra like a charm. “Parenting isn’t defined by blood. It’s a choice you repeat every day. Sometimes strangers love you better than family. Sometimes you get to choose the people who raise you—not up or down in age, just…raise. You hear me?”

I nodded, the knot in my chest loosening like a rope given back an inch at a time. I sipped the latte Steven placed near my elbow a minute later and thought, for the first time in months, that like doesn’t have to be earned and love doesn’t have to be begged.

That night, in the quiet of the apartment, I looked at my phone and scrolled past missed calls and messages labeled TRAUMA in my own head. I deleted Kevin. I muted my mother. I turned off Emily’s read receipts. I texted my father-in-law: I am safe. I am grateful. Please don’t worry. He responded with a single heart and a photo of the old clock in his hallway—its hands exactly on the hour, as if to remind me time could be right again.

“Tomorrow,” I said to the ceiling, to myself, to the hungers that had learned my address. “Tomorrow I’ll start again.”

And I did.

Part II

The first night in the company apartment I fell asleep without counting my mistakes. That sounds small; it wasn’t. For months I’d been cataloging failures the way other people keep grocery lists—milk, eggs, quiet, apology. I woke before my alarm to the noise of the city coming to life—garbage truck brakes, a neighbor’s laugh, a kettle somewhere refusing to be ignored—and realized the thing that wasn’t there: the dread I’d been waking to like a fire alarm you can’t find.

Maria texted at 6:12: Come in when you like. Coffee’s on, Steven’s nicer after two cups, and don’t forget the key fob. Three heart emojis, the yellow kind that look like construction paper cutouts.

I walked to work. It took exactly twelve minutes if I waited at the big intersection and nine if I jaywalked with the confidence of a person who had decided she belonged wherever she placed her feet. I still waited.

Steven met me at the door again like he’d been stationed there. “Ready?” he said with the kind of grin teachers use when they have no idea what a student will be, but they’ve decided to like it.

“For what?”

“First rule of design,” he said, sweeping a hand toward the studio. “Everything is improv.”

He showed me the software—how to drag a wall two inches to save a thousand dollars, how to anchor a bookshelf to a wall so it doesn’t crush a toddler, how to label a tile sample in a way the contractor won’t pretend he misread later. He showed me the supply closet where dream goes to die—mismatched cabinet pulls, rugs clients had ordered and then hated once the light told the truth, paint cans with names like Mist and Salt and Nearly There. He showed me where the coffee filters lived and how not to stare at the fancy espresso machine like it would call me out for being from a different sort of kitchen.

At eleven he said, “Field trip.”

“To where?”

He held up a set of keys on a lanyard Maria had embroidered with INTERIORS OR ELSE. “Client walk-through. I promise nobody will bite. If they do, it’s billable.”

The client was a woman in her fifties who said tile like a person says trust—carefully, with an eye on the receipt. Her husband was quieter, one of those men you mistake for uninterested until you notice his hand rest on the doorframe like a prayer.

“I hate decisions,” the woman said, gesturing to a collection of samples on the kitchen island that had begun to look like a crime scene. “Why are there eight kinds of white?”

“Because manufacturers are petty,” Steven said. “Also, light is a liar. But we can make it tell the truth.”

He placed the samples on the counter one by one and had her stand at the window, then at the stove, then in the hallway, then right under the pendant. “See?” he said when she frowned. “Same tile, different shadow. We pick the one that lies the least.”

I watched her shoulders drop. I watched her husband smile at the floor. I took notes that were not notes, just sentences I wanted to keep: Pick the thing that lies the least.

Back at the office, an email waited from Kevin. Subject line: You’re welcome. Body: Your parents sent the check. I’ll allow it.

I stared at the screen and felt my hands go cold. The check my parents had written had appeared on our counter the night I left; I’d left it there. They’d slid it onto his side like appeasement with a memo line that read to make it easier. I hit forward and sent it to Maria and Mike with a single line: I’m not touching this. Maria replied with a GIF of a woman pushing a cake off a table with both hands. Mike replied with: Respect. I’ll take it to them. You don’t have to.

Ten minutes later my father-in-law called. He rarely used words he couldn’t cash. “I told him,” he said, throat rough with a thing he didn’t swallow this time, “that if he took one more yen on your behalf, he’d never see my face again.”

“You don’t have to—” I began.

“I’m not doing it for him,” he said. “I’m doing it for you. Come for dinner Thursday. No agendas. Just rice and fish and people who know how to say they’re sorry without making you reassure them.”

I covered the receiver and breathed out a yes. “Thank you.”

When I hung up, Steven was at my desk, holding a paper bag that smelled like something honest. “You forgot to eat,” he said. “Turkey sandwich, mostly mayonnaise, which I hate, but you look like you won’t.”

“Thank you,” I said, and then, because goals are dumb unless you say them out loud, “I’m going to be good at this.”

“You already are,” he said. “You just don’t know the names for the parts yet.”

By week two, my muscles remembered how to hold a full day. By week three, my inbox did not scare me. Maria stationed me under Steven and above no one except the girl who watered the plants and was twelve and made more sense than anyone I know. On Fridays, Maria let me sit in on client presentations if I promised to keep my eyebrows from telling the truth before my mouth did.

In the evenings, my phone buzzed with my parents’ numbers. I didn’t answer. When my mother texted Dinner Sunday?, I texted back: No. Not yet. I need time. She replied We’re your parents, how much time? and I stared at the sentence until the words blurred into shapes I did not recognize. I put the phone facedown and made a list in pen: change locks, cancel shared card, block Kevin, breathe.

Kevin found new ways to throw pebbles at my windows. Emails with subject lines like Be decent and Remember who fed you and once, just a single emoji of a hand with its palm up. I built a rule that sent them to a folder named TRASH and then another that skipped the naming ritual entirely and did what needed doing. Mike called the lawyer. A week later, a letter slid under Kevin’s door with words that bristle—harassment, cease, reportable. He sent me one more email that said snitch and then nothing at all, because some men can only talk when they think the room won’t answer back.

Maria and Mike came by on a Saturday with their son, who brought a Lego set and the kind of focus only a child and a surgeon can maintain. He sat on the rug and built a spaceship while the grownups pretended not to peek at the instructions. When he held it up between two hands with that face kids wear when they hope their effort looks like magic, Maria cried. Mike cried. I cried. The boy blinked, surprised by the weather.

“I got this wrong for a long time,” I said to Maria later, while we washed mugs. “I thought family was a fixed thing. Turns out it’s a verb.”

“Everything worth having is,” she said, bumping my hip with hers.

The divorce decree arrived with a courthouse smell. I signed where my name wanted to run back into the past. Ms. Kline slid a copy across the desk and said, “Congratulations in the least joyful tone possible.” I laughed. She smiled the way paper does when a page settles on the stack just right.

Kevin texted that night. Emily’s moving in. My parents support us. Everyone knew you couldn’t have children. I stared at that sentence and felt a blueprint unroll inside my chest. It was one thing to be called barren. It was another to realize he’d married me knowing, and that somewhere along the way that fact had become a knife he liked to wave.

I thought of Emily’s divorce, the child she’d relinquished to her ex without a fight because joint custody inconvenienced her social calendar. I thought of the way she’d say I just can’t bond and my mother nodding like the sentence made sense. I thought of my father, who knows tax code the way priests know scripture, and wondered how many times he’d told himself doing right by one daughter meant not doing wrong by the other. The math didn’t show up.

When I told Maria, she listened and then said the quiet part out loud. “There’s a not-small chance they told Kevin to use protection.”

“What?” My hand went to my stomach like a reflex, the way you shield a body part you’ve been told is broken.

“You were sick a lot as a kid,” she said. “Your mother is the kind of woman who thinks love means preventing danger. Preventing risk. Preventing mess. She might have thought she was saving you. She might have been saving herself.”

The floor tilted. In my marriage, I had apologized for a biology I’d assumed was written in block letters. Now it appeared someone had erased sentences in pencil when I wasn’t looking.

If there was rage, it hid behind the shock like a child hiding behind a parent at the door. More than anything, I felt…room. A space inside me where shame had been living rent-free. I stood in that old apartment of mine—the one inside—and felt light coming through a window I hadn’t known could open.

“Even if it’s true,” I said to Maria, “we don’t call them.”

“No,” she said. “We don’t call anyone. We go to a doctor, and then we go have a life.”

I went to a doctor. She looked me in the eye, ordered labs without making me feel like a specimen, and asked kind questions in plain English. “Things look good,” she said two weeks later, tapping a paper like she had purpose. “If you want to try, try.”

I walked out into heat that made the city smell like fresh bread and asphalt and possibility. On the corner, Steven stood under a tree holding a paper cup and two big iced coffees like a cliché I wanted for myself.

“How’d it go?” he asked.

“Turns out I’m not a cautionary tale,” I said. We grinned like thieves.

“Want to celebrate or forget?” he asked.

“Both,” I said.

We headed to the farmer’s market and bought peaches that left my hands sticky and flowers that didn’t know whether they wanted to be wild or behaved. Back at the office, Maria raised an eyebrow at the bouquet and then mouthed, Good, like a director watching actors hit their marks.

Weeks collapsed into months the way new lives do. Steven and I stopped pretending our lunches were accidents. He told me about his mother, who had died when he was nineteen, and his father, who had worked three jobs and still found time to plant tomatoes in coffee cans on their windowsill. I told him about my mother’s jar of candies reserved for Emily and how I’d learned, early, that love in our house sometimes came with someone else’s name on the tag.

“Do you want children?” I asked him, on a walk after dinner under a sky that had finally decided it didn’t want to be August anymore.

“I want to keep choosing you,” he said. “If children are part of that, I’ll learn how to choose more. If they aren’t, I’ll remember to buy more plants and volunteer to teach soccer and be the uncle who shows up with bandaids and snacks.”

“Everyone says that until the doctor says no,” I said, a smallness in my voice I hated.

He stopped, turned me toward him like the gentlest version of insistence. “If the doctor says no, we figure it out. I don’t love you because your body is a vending machine.”

I laughed because I had to. “That is the worst metaphor I’ve ever heard.”

He grinned. “Like I said, improv.”

Six months after the divorce, Kevin and Emily posted engagement photos in a park where the trees did their best to make people look better than they are. Her dress was white. His grin was wide. My mother’s brow had been furrowed smooth by the stylist. My father looked like a man who had decided to be agreeable for the length of a photographer’s session and then renegotiate later. I didn’t comment. I didn’t show up. I went to Maria and Mike’s and ate barbecue that Mike swore “had secrets” and learned the names of three new paint colors and built a spaceship with the boy who had chosen to call them Mom and Dad.

In the middle of that love, grief still visited. It sat on the couch some nights and watched us watch TV. It showed up in the grocery store when I reached for Kevin’s favorite brand of hot sauce and had to put it back like contraband. It knocked on the door when I got a promotion and the empty parentheses next to Spouse to invite to dinner? made my stomach flip.

Steven learned to sit beside grief without trying to knock it out with jokes. When he saw me teeter, he didn’t rescue me. He steadied the table.

“Do you want to go to the cemetery?” he asked one Sunday.

“Whose?” I asked, because humor is a life raft if you treat it that way.

“Yours,” he said. “The one where you buried the version of yourself who apologized to furniture for existing.”

We went to a park instead. We sat on a bench and wrote down all the things I was sorry for and then didn’t light them on fire because this is real life and parks have rules, but we did tear them up and let the pieces blow under the bench. Some kids ran past and crushed our confessions into the dirt and that felt exactly right.

By our anniversary—the anniversary Steven and I had decided was ours, the one that marked the day we started calling each other home—I could walk past a mirror without flinching at the person in it. My life was a series of rooms with doors I had permission to open. I had an apartment that smelled like lemon and paper and basil when I remembered to water it. I had a job where equal meant equal and not We call you that if you don’t ask for a raise. I had love that looked nothing like sacrifice.

A week later, my period didn’t come.

I didn’t tell Steven for two days. That is how long it took to decide that, no matter what the test said, the version of me who didn’t apologize got to stay.

When I did tell him, he laughed and cried at the same time, a sound like rain hitting a metal roof. He put his hands on my face. “If it’s no,” he said, “we’re still us. If it’s yes, buy two pastries, because I’m going to faint and I’d prefer to do it with chocolate in my mouth.”

It was yes.

The doctor was kind in a way that made me want to bake for her. She printed out the ultrasound photo and wrote Hi, kid in the corner. I took it home and stuck it to the fridge with a magnet shaped like a banana. The next morning, I moved it to the inside of a cabinet door because I’m superstitious in stupid little ways and wanted the joy to be both obvious and ours.

We told Maria and Mike first. Maria screamed so loud the neighbors opened their door. Mike cried into a dish towel and then lied about it. My father-in-law showed up with bags of groceries and a list of names he thought were good, all of them terrible and all of them offered with a kind of glee that made them beautiful.

I did not call my parents. I did not call Kevin.

The night before my twelve-week appointment, I sat on the couch with Steven’s head in my lap and told the ceiling, “I’m not sorry my body is not an apology.” The ceiling said nothing. It didn’t need to.

A month later, in a tourist town three hours from home, under a ceiling of paper lanterns and the smell of steeped tea, I heard Emily say my name like a curse and Kevin say it like a prayer.

“Ashley?” she said, a familiar sneer curling the word. “Still moping around, traveling alone after the divorce?”

I turned. Steven came out of the restroom at that exact second, blessed by plumbing and providence. He took in the scene in a glance—the ex, the sister, the old hunger—and crossed to me with a soft apology for the line and a hand at my back that told my bones we were fine.

“I’m Ashley’s husband,” he said, a sentence that sat in the air like fresh paint. “Her name is Ashley Stevens now. Also”—he patted my stomach with the care of a man greeting one person through another—“we’re expecting.”

Kevin went pale the way a person does when their movie pauses mid–scene. Emily scoffed the way a person does when their lines aren’t landing. “I hope the baby’s… not… you know,” she said, eyes flicking to my belly with a meanness I had once been trained to call honesty.

“Healthy?” Steven said. “Our daughter is, thank you. She’s two. She’s at my parents’ backyard cinema night right now, probably bossing Grandpa around. This is our second.”

Silence. Markets have their own hush—the moment before someone bargains, the moment after someone pays. This was not that. This was the sound of a story revising itself without the author’s consent.

I stood there, with the smell of jasmine and sugar and rain in the air, and felt everything align. Not triumph. Not gloating. Just…rightness. The kind that doesn’t need to be announced to be real.

Emily recovered first. She flicked her hair with a practiced motion that had worked on richer men. “Funny,” she said. “I had to terminate. The doctor said the baby might… not be perfect. I’m not doing that to myself.”

There it was. The rot at the center. Steven’s hand tightened on my arm. I stepped closer to him because sometimes the bravest thing is to be a person who doesn’t rise to bait.

Kevin, desperate, lunged at a new angle. “Give me one of your kids,” he said, voice low and frantic. “My father will disown me if I don’t—”

“Save your vile remarks for your own demise,” Steven said, crisp as glass. He didn’t raise his voice. He didn’t have to. He turned us away without waiting for a reply.

As we left, I glanced back. For a second—one second—I saw the future sitting there with them at the table. It looked like unpaid tabs and empty rooms and the kind of loneliness you can’t fix with strangers. It looked like a man who had run out of people to blame and a woman who had run out of mirrors to admire herself in.

We didn’t run. We walked to the train. Steven held my hand like a vow. I looked out the window at a world busy being itself and thought, not for the first time, that sometimes the thing you believe will kill you is just the part that had to die so you could live.

We went home. We fed our daughter strawberries in the kitchen and watched her paint her face with juice and pride. We said want more? and she said again and then, with sticky hands on my cheeks, Mama smile. And I did.

Part III

The train home swayed like a cradle and I let it. Steven’s shoulder was warm where it leaned against mine, our hands laced in that easy grip you forget is holy until you almost lose it. I stared out the window and watched the world move in a smear of green and brick and lightning–struck sky and thought about all the things that had just been said to me in a teahouse that smelled like jasmine and old paper: barren, terminate, give me one of your kids. Words like rocks tossed at glass. Only this time the window didn’t break.

At home, our daughter raced down the hall in footie pajamas and launched herself at Steven’s knees like a tiny linebacker. “Daddy,” she sang, sticky palms on his cheeks—the sugar we’d sworn we weren’t going to give her smeared across her grin like pride.

“Hey there, strawberry thief,” he said, and scooped her into the air like the world wasn’t heavy. She squealed and then demanded, “Mama smile,” solemn as a judge with her hands on my face. I did. Some orders you follow for your own sake.

We made a quiet pact not to talk about the teahouse in front of the baby. We ate grilled cheese on the floor and watched cartoons with colors that looked illegal. After she was asleep, we sat on the couch and looked at each other like the room contained an animal we weren’t going to feed.

“They wanted to take,” Steven said finally. “Not because they need. Because they can’t imagine a life that isn’t taking.”

I nodded. The baby monitor hissed softly like a sleeping thing. “Do we tell my parents?” I asked.

“About the meeting? No. About the pregnancy… when you’re ready.”

“I meant about—” I swallowed. “Maria thinks they told Kevin to…prevent.”

He leaned forward, forearms on his thighs. “Do you want to know for sure?”

I pictured my mother, hands folded in a lap that always looked composed, and my father, face smoothed into accountant’s patience, the kind of people who prayed order into chaos and occasionally succeeded. I pictured the jar of hard candies that lived on their hallway table—the ones that were always for Emily. I pictured what I would do with proof and decided the answer was nothing.

“No,” I said. “I want to live a life where it doesn’t matter.”

“Then that’s the life we’ll live,” he said simply, and kissed my knuckles like vows.

Pregnancy fit me like a dress that had once been someone else’s and somehow turned out to be mine. I was tired in new ways, tender in places I hadn’t known could bruise, ferocious over a heartbeat the size of a seed. Our daughter noticed first. She would lay her doll on my stomach and shush the house with her whole hand. “Baby sleep,” she’d whisper, brow furrowed with care she’d invented herself.

My father-in-law—who had asked, so gently, if he could use “Grandpa” when she was born and then never once used it as a lever—started bringing soup. He’d ring the bell and set the bag down as if we were feral cats who would bolt if he reached too fast. “Fish,” he’d say, waving away the thank you he clearly came to collect. “For calcium. And because life is better when it smells like the ocean.”

One Sunday he came early and stayed. After dinner he helped Steven bathe our girl, rolling his sleeves to his elbows like a job, and then settled on the couch with a book about trucks that didn’t contain a single emotion. “I wanted sons,” he said to the page, voice far away and very near. “I got them. And then I got you.”

“Me?” I asked.

“You,” he said, eyes meeting mine now. “The daughter I didn’t earn and didn’t deserve. The one who taught me what it feels like to be happy and worried at the same time. The one who says no to me when I deserve it.” He smiled. “You did good work today. That tea place? Saying nothing is sometimes the bravest sentence.”

I could feel the flush creep up my neck. “You heard?”

“Mike heard from Maria who heard from Steven who has the good sense to tell me nothing unless I can help,” he said. “I can’t help. I can sit in a chair and tell you I’m proud. I can throw Kevin out if he shows up at my door with his hand out.”

“What if he brings Emily?” I asked, and immediately regretted it—the sour coat her name left on the tongue.

“Then I’ll put on water and show them a door and say, There’s the street. Walk it.”

We laughed. It took the taste away.

Our son came on a Tuesday, stubbornly on his own timetable. Labor was less drama and more work—a long day with no coffee and a good prize. Steven cried in a way that made the nurse pat his shoulder and say, “Sir, it’s okay,” like that had ever been in question. I watched their faces—Steven’s awe, the nurse’s professional tenderness, my own mother’s—no, not my mother’s. I didn’t call. I called Maria. She yelled and then showed up and took one look at my son and declared, “He has your mouth,” as if genetics was an apron string you could tug to check the quality.

We brought him home in a onesie too big and a hat too smug. Our daughter regarded him like a new appliance. “Baby,” she said, reverent and suspicious. “Share?”

“Yes,” I said, and meant it all the ways it could be meant.

At three in the morning on day five, when the house was quiet in the way houses get when everyone’s exhausted and the refrigerator hum sounds like a lullaby, I sat on the couch with my son in my arms and tried to feel every cell of the moment. Steven shuffled out and sat at my feet, his head resting on my knee, a man folded into reverence.

“I’m sorry,” I said without thinking, and even as the word left my mouth, I heard its wrongness.

He lifted his head. “For what?”

“I don’t know,” I said, looking down at our boy. “For past me. For everything I thought I owed the world because my body didn’t do what it was supposed to do. For making you hold my shame sometimes, even when you told me to put it down.”

He laughed softly, not unkind. “Should I kneel and apologize for anything my body can’t do?” he asked, amusement and correction braided. “We are not vending machines. We are people who love each other. We are enough even when nothing else arrives. Also, our baby’s very cute.”

“He is,” I admitted. It was an admission of faith, not fact.

Kevin’s life unraveled the way a shirt does when you catch a loose thread and tug. Emily left. Of course she did. The first signs were small—fewer photos together, captions that sounded like me talking to myself after a fight. Then a post with a ring in a dish and a caption: starting fresh. It looked like a perfume ad for regret.

He called my father-in-law. He called Mike. He called me exactly once. “You did this,” he said when I picked up thinking it might be a wrong number, in that flat tone of men who believe the universe keeps a ledger and women are holding the pen. “You poisoned them against me.”

“You did that,” I said. “By being exactly who you are.”

“I need help,” he said, switching gears so fast you could smell the clutch. “Dad won’t— Mike— I’m drowning. Give me something.”

“Get a job,” I said. “Stop drinking. Stop lying.” I surprised myself with the calmness of my voice. “Then call the people you didn’t set on fire. Maybe they’ll hand you a bucket.”

He hung up with a noise. Sometimes people forget that other people can hear the noise they make when they end a call. It sounded petulant. It made me sad for a second. Then my daughter came in wearing a colander on her head and announced, “I am a robot,” and the second passed.

Emily’s downfall was less pity and more math. Lawsuits came. The married man she’d been seeing had a wife with a lawyer who didn’t nap. The jealous company she thought would be her ladder turned out to be a hole. Money evaporated because money does that when you believe it’s air. My mother called and left a message—the kind that makes you think of a person standing in a kitchen with a phone held in both hands. We need help, she said, no preface, no how are you. Your sister— We— The line crackled. Her breath sounded loud with practice. Please.

I stared at the ceiling. My father-in-law’s words came back like a hammock: You did good work today. There are two kinds of doors. The kind you close because someone you love needs the chance to knock. And the kind you close because there are people on the other side who think your house is theirs. I chose the second.

I sent a text: I hope you find the help you need. I can’t be it. I’m protecting my family. She didn’t reply. A month later I got a postcard with a picture of a mountain my mother had never climbed and a sentence that read like a note slid through bars: We are moving. I set it on the fridge with the ultrasound, the truck book scribble, a photo of Maria crying into a dish towel with joy on the day our daughter said Mama and meant her. Then I took the postcard down and put it in a drawer. Some things belong in the story. Some belong in the filing cabinet.

Mike called on a Thursday to ask if he could bring their son over to meet the baby properly. “He’s been practicing holding his arms like a basket,” he said, equal parts pride and terror.

They arrived with soup and a Lego set and the kind of shoes that slip off quietly. Their boy took his job so seriously I wanted to apologize to all the gods for ever having doubted children. “Hello,” he said to my son. “I am your cousin in a way. I will teach you how to make a spaceship.”

We ate and didn’t talk about the teahouse and didn’t talk about my parents and did talk about paint samples and preschool and the fact that Maria had been asked to do a lobby for a nonprofit that helps women leave bad men. “I said yes before they finished their sentence,” she said. “Sometimes the world presents you your calling like a server who needs you to decide.”

After dessert, Mike cleared his throat. He’s not his father, but he’s his father’s son. “Dad told us what he said to you,” he began. “The proud thing. He meant it. So do we. Also—” He looked at Steven, then at me. “We need to talk about family holidays.”

I braced and then heard myself laugh. “You mean who brings the pie?”

“Yes,” he said, relief clear. “And the rules. And the fact that you can say no and still get invited next time.”

“That,” Maria said, pointing with her fork, “is the whole point of love.”

Three years after the night I folded three blouses and put a locket in my pocket and closed my own door behind me, we took a small trip because sometimes the life you build needs to see the world to remember it exists. We rented a tiny house with a porch that pretended at the sea and spent afternoons teaching our daughter how to lose at cards without losing herself.

On the last day, we were early to the train and stopped at a tea shop with wobbly tables and little spoons that made me feel like a giant. That’s where Emily said my name like something she wanted to eat and Kevin said it like something he wanted to owe. That’s where Steven told the truth in two sentences and then walked us away.

The next morning our son woke us at five with the urgent argument that darkness is a conspiracy and joy is an emergency. Steven took our daughter to my father-in-law’s for pancake day. I stayed home with the baby and the quiet and the knowledge that the world had kept turning without me having to push.

I made a list because it’s what I do when I want to keep steadiness from becoming a spell that breaks if you look at it. The list was simple: read, nap, soup, call Maria, kiss Steven, say yes when Mike asks if he can bring over a broken lamp to fix so he can feel helpful. Say no if anyone knocks who thinks my door is a negotiation.

At noon, the baby fell asleep on my chest, profound as worship. I sat very still and stared at the dust motes in the beam of sun on the rug and thought, I am not sorry. Not for leaving, not for staying, not for being a person whose body made a lie out of other people’s certainty. Not for saying no to my parents and yes to my life.

Steven came home smelling like maple and exhaustion. Our daughter ran in with syrup in her hair and announced, “Grandpa put blueberries in the pancakes on purpose and I didn’t like it and I told him and he said okay and made me a plain one and that is compromise.”

“Exactly right,” Steven said. “Now tell Mama what compromise is again because she’s forgotten how to share me with naps.”

We fell into the couch and into laughter and into the kind of afternoon that makes time behave. At some point, my phone buzzed. A new message, an unknown number, a photo of a piece of paper—Account settled. Below it: I am trying. —E. I stared, let the feeling move through me and not set up a tent.

“Everything okay?” Steven asked.

“Yes,” I said, and meant it so hard my teeth hurt. “Everything is okay.”

I picked up the baby. He smelled like milk and possibility. Our daughter kicked her feet against the table and sang the alphabet because we all need rituals that put order back where the world plays tricks. I texted Maria: Tea tonight? I have a story that isn’t about them. She sent back five heart emojis and Always.

We are not the sum of what was done to us. We are what we choose next. That day we chose soup, and kisses, and the word ours said over and over until the house learned the shape of it.

Part IV

By the time spring remembered how to behave, our son could hold his head up long enough to stare me down and win. He had Steven’s calm and my father-in-law’s stubborn and the kind of laugh that makes strangers forgive you for blocking the grocery aisle.

The paperwork of a life had kept pace with the living of it. My last credit card with my old name expired and didn’t get replaced. The DMV photo captured me mid-blink and still looked more like me than any glamour shot from my first wedding. Maria framed it and hung it on the office corkboard with a caption in Sharpie: She blinks, the world keeps going. There’s a kind of honoring in letting the ordinary be enough.

The letter from the court finalizing the custody nothing and property nothing arrived with a stamp and a shrug. Ms. Kline sent a note that said, I hope we never work together again. I sent back a box of cookies and a Post-it that said, Same.

I hadn’t seen my parents in more than a year. Sometimes absence is mercy. Sometimes it’s a strategy. Sometimes it’s both.

The Saturday after the baby learned to roll without permission, a certified letter slid under our door the way certified letters do—like guilt in an envelope. My mother’s handwriting on the front made my stomach do what it used to do before tests in school, the drop and flip and drink-too-fast lurch. I stood with the envelope between two fingers and breathed until I could hear the house again.

“Open it?” Steven asked.

“Yes,” I said. “I’m the adult in this room.”

Inside: two pages, both short. The first from my father, typed, formal in a way that reminded me of an apology written by a man who believes in templates: We counseled Kevin to proceed cautiously about children because we feared for your health. I see now it was not our choice to make. I am sorry. The second in my mother’s hand, the loops of her letters shaky as if the pen didn’t believe her: I wanted to keep you safe. I was wrong. We miss you. We saw your daughter in a picture. She looks like you did when you were two: curious and bossy. If you ever want to meet for tea—public, daylight, your choice—we will come to you.

I set the letters on the counter next to an apple with one bite missing and a dinosaur sticker that had lost its stick. My first impulse was to light both pages on fire in the sink and call the smoke a ceremony. My second was to frame them under glass and make a shrine to the thing they should have done years ago. Instead, I left them there and folded laundry and fed the baby and laughed when our daughter insisted that socks belong on elbows because they are arm shoes, Mama.

That night, when the children were asleep and the dishwasher hummed like a content animal, I called Maria.

“They apologized,” I said, surprised by how flat the word felt.

“Does the apology ask you to do the work?” she asked.

“No.”

“Does it name the harm without asking to be comforted?”

“Yes.”

“Then it’s an apology,” she said. “Now you decide what you do with it. Not for them. For you.”

We met at a park three weeks later. Neutral ground, wide sky, a playground shaped like a ship where you can’t hear people talking about the past over the sound of kids being pirates. I told Steven he didn’t have to come. He came anyway and took our daughter to the swings, pushing her with that perfect dipping rhythm that fathers learn and never unlearn. Our son slept in the carrier against my chest, a small, sure weight.

My parents sat at a table near the rose garden like people auditioning for a kindness they weren’t sure they could keep. My mother’s lipstick was softer than it used to be. My father’s tie was crooked.

“Ashley,” my mother said, hands on her knees as if she’d promised herself not to reach for me.

“Mom,” I said. “Dad.”

There are apologies that unravel into excuses. These didn’t. My father said, “It wasn’t my decision to make. I made it anyway.” My mother said, “I thought I was preventing harm. I caused it.” They didn’t cry like people in movies. They looked like they do on Sundays when the sermon lands where it should—stunned, grateful, chastened.

“You taught me to set tables,” I said, the first truth that came. “I’m keeping one set for you. It’s outside. There are rules.”

My father nodded. “Say them,” he said. He’s always liked lists.

“No more advice dressed as love,” I said. “No more deals made about my life without my name on the paper. If you want to know my children, you learn to know me first. You don’t meet them until I know I won’t be cleaning up after your feelings. You go to therapy—individually, together—I don’t care which. You do the homework. You apologize without inviting rebuttal. You don’t test the fence. You don’t knock without asking if today is a day I answer.”

My mother put a hand over her mouth. The tears that came weren’t the kind designed for an audience. “Okay,” she said. “Okay.”

“They can still mess up,” Maria had said, hugging me in the office copy room the week before. “You can still close the door. The miracle isn’t that they’re trying. The miracle is that you have a door.”

When I stood to go, my father reached in his jacket and slid an envelope across the table—the severance check I’d left years ago, uncashed, crimped now at the corner like it had been carried around as penance. “We tried to give you this to make it easier,” he said. “Keep it. Burn it. Donate it. We won’t ask, and we won’t write another.”

I took it. Not as money. As acknowledgment.

“We’ll call when we have something to say,” my mother said. “No sooner.”

I walked back to the swings and watched Steven push our daughter until she could almost see over the fence. Our son shifted his head against my chest and sighed like someone who expected the world to be soft and was rarely disappointed.

“Okay?” Steven asked.

“Yes,” I said, the word landing like a coin on a counter. “Not fixed. Not the same. But okay.”

The lobby project Maria had taken on—the one for the nonprofit that helps women leave men who kept teaching them to doubt themselves—opened in June with lemonade in paper cups and a ribbon Maria refused to pay for. I helped hang the last pieces in the morning, a gallery wall of phrases we’d lettered by hand onto stained wood.

You are not late.

A door is still a door if you close it.

Pick the thing that lies the least.

The director asked if I would say something at the dedication. “It matters that people see the results,” she said. “Not just the before pictures.”

“I’m not a speech person,” I said.

“You’re a life person,” she countered. “Say what you wish someone had told you the day you needed this room and didn’t have it.”

I stood under Maria’s pendant lights and looked at the faces in metal folding chairs: a woman with a fading bruise and new haircut; a man with a baby strapped to his chest and a fear of court; my father-in-law in a clean shirt and the posture of someone who knows when to be quiet; Steven at the back with a kid on each knee, his eyes on me like a steadying hand.

“When I left my first marriage,” I said, “I thought the world would argue with me forever. Then I learned the world only talks that loud when you’ve been trained to listen to the wrong voices. If you’re here because you need a door, use it. If you’re here because you want to help build more doors, roll up your sleeves. The rest of us—” I looked at Maria, at Paula from the hospital’s compassion office, who had come on her lunch break, at the woman in the second row holding a pamphlet like a lifeline—“we’ll be here with socks and clipboards and the kind of love that doesn’t need applause.”

They didn’t clap as much as breathe. One woman laughed that laugh people make when relief sneaks up on them and they apologize to no one about it.

After, a teenager in a denim jacket hovered by the gallery wall. She ran a finger under You are not late like she was sounding out the words.

“I should’ve left sooner,” she said to the sign. “Everybody says that.”

“Maybe,” I said. “Maybe you left exactly when you could. We can put more chairs in the room, but we can’t make you sit down until your legs decide to.”

She looked at me, eyes wet and ferocious. “I’m enrolling in GED classes.”

“Then I guess your legs decided,” I said.

She grinned. “The chairs are ugly,” she added, because sometimes honesty is a gift that arrives wrapped as insult.

“They stack,” Maria said from behind me. “Truth is prettier.”

Kevin orbited as people like him do—calling from numbers he thought would trick me, switching subject lines from help me to you owe me like it was a wardrobe. The day he showed up at my father-in-law’s building and pounded on the glass with both hands, the super called upstairs and asked, “Do you want me to let him in?” My father-in-law said, “No,” and hung up. Sometimes the most loving thing you can say is a single syllable.

He sent one more email—I’m going to rehab. You win—and then went quiet. Months later, I heard from Mike that he had finished a program and was mopping floors in a church basement because it made him feel useful. I didn’t cheer. I didn’t spit. I took our daughter to the park and pushed her on the swing next to a woman whose kid insisted leaves are money and we must be very rich. There are stories you don’t finish because they aren’t yours.

Emily’s chaos slowed to a simmer. The lawsuits settled. The apartment became smaller and cleaner. She got a job that required a name tag and a schedule and came home smelling like hair dye and acetone and women who bring pictures of celebrities and point to themselves in the mirror with hope and cruelty in equal measure. She sent a message on my birthday—I don’t deserve it, but I hope it’s happy—and I sent back a thumbs up because sometimes that’s all the peace you can put in the mail.

On our son’s first birthday, we hosted a picnic in the park behind our building. The kind with cake that comes out of a foil pan and tastes like apology to no one. Maria and Mike came with folding chairs and a Bluetooth speaker that insisted we dance to ridiculous songs until passersby smiled in spite of themselves. My father-in-law arrived with watermelon and a story about a neighbor’s cat who thinks his lap is a timeshare. The boy they had raised—still shy, still sturdy—taught our daughter how to build a fort out of blankets that refused to cooperate because the wind had opinions.

Near the end of the afternoon, the teenagers from the nonprofit’s opening walked by. The one with the denim jacket waved. “I passed my math test,” she shouted. “The chairs still suck.”

“Better news first,” Maria called back, and the girl laughed like thunder clearing its throat.

Later, after we’d carried the paper plates to the trash and reassembled the stroller like NASA engineers, a couple I didn’t know stopped by our table. The woman touched the corner of the photo printed on our invitation—our family on the stoop, our daughter scowling with concentration at a bubble, our son considering the photographer like a reasonable person worth meeting—and said, “I know you. Not your name. Your…space. I recognized the lobby. I sat under the sign that says Pick the thing that lies the least and broke up with a lie.”

“I’m glad,” I said. It wasn’t mine. It was ours.

We walked home under a sky so blue it looked like a decision. Steven carried our son. Our daughter dragged a stick that had become a wand and turned passersby into frogs and pizza at will. On the stoop, my phone buzzed. A text from my mother: Tea next week? We can sit outside. I’ll bring nothing but my wallet and my quiet. I typed back: Yes. The garden on 8th. Thursday. Come early. We’ll leave when I say. She responded with, I’ll be early. I believed her. That was new.

Inside, we did the bath-pajamas-books rhythm you learn by heart the way you learn to steer a car—wrong, then right, then muscle memory. Our daughter fell asleep mid-sentence, a hand on Steven’s arm like a claim. Our son lay in his crib and practiced syllables like a song no one had taught him.

On the mantle, my grandmother’s locket sat open next to two ultrasound photos and a picture of Maria and Mike’s boy in a paper crown. The locket’s tiny oval frames held two things now: a photo of me at two, bossy and curious, and a slip of paper where I’d written a sentence the day I left my first marriage and had never quite been brave enough to keep in my pocket. That night, I folded it smaller and tucked it in: I don’t walk back through doors that hurt. I build new ones and leave the light on for the love that knows how to knock.

Steven came up behind me, chin on my shoulder, arms around my waist, the kind of hold that says both stay and go wherever you need, I’ll be here when you return. He followed my gaze to the mantle, to the locket, to the photos, to the line I’d written and rewritten in my head until it finally belonged on paper.

“Home?” he asked.

“Home,” I said, and felt all the rooms answer.

Outside, the streetlight blinked once and then remembered its job. In the nursery, our son turned over and sighed. In her room, our daughter snored like a cartoon. In a quiet kitchen, a letter from my parents waited under a magnet shaped like a banana, not demanding, not directing, just there.

I turned off the lamp. I left the porch light on.

The End

News

CEO SLAPPED Pregnant Wife at Restaurant—The Chef Was Her Navy SEAL Brother! CH2

Part One: The Silence Before the Storm The night had begun like any other at Coastal Kitchen, the upscale waterfront…

I CAME HOME UNANNOUNCED ON CHRISTMAS EVE. FOUND DAUGHTER SHIVERING OUTSIDE IN 31°F, NO… CH2

Part I I didn’t plan the surprise like a movie. There was no orchestral swell when I turned into our…

My Husband Poured Hot Coffee on My Head in Front of His Mother and Our Son for Refusing to Pay for CH2

Part I I still have the receipt from the night I should’ve known better—curled thermal paper, $8 Uber to a…

Rich Wife Hid A Camera To Catch Her Husband With The Maid… But What She Saw Shattered Her World. CH2

Part I The receipt was not much to look at—cheap thermal paper curled like a leaf left too close to…

I Thought Letting My Ex See the Baby First Was Sweet — Now My Husband Walked Out on Me at the Hospit CH2

Part I The day we argued in the nursery, the paint was still tacky on the baseboards and the crib…

My fiancé recoiled when I mentioned morning sickness at our baby shower and loudly announced… CH2

Part I I used to think gift wrap solved everything. It made chaos pretty. It turned a tangle of receipts…

End of content

No more pages to load