The Impossible Pivot: George S. Patton, the 72-Hour Miracle, and the Salvation of Bastogne

I. The Storm of Despair in Verdun

The air in the command tent at Verdun, France, on December 19th, 1944, was thick with the despair of cigar smoke and impending catastrophe.

Outside, the worst winter in living memory gripped the Ardennes Forest. Inside, the Allied Supreme Command faced the chilling reality of Hitler’s final desperate gamble: The Battle of the Bulge. German Panzer divisions, unleashed in a surprise blitzkrieg, had shattered the thin American lines, creating a deep, fifty-mile-wide bulge in the Western Front.

The situation was dire. Communications were severed. American forces were in full retreat and chaos reigned. At the heart of the crisis, the elite 101st Airborne Division—the Screaming Eagles—was completely surrounded, trapped, and freezing to death in the critical Belgian crossroads town of Bastogne. If Bastogne fell, the Germans could split the Allied armies, seize vital supplies, and drive the Allies back to the sea, prolonging the war indefinitely.

Shutterstock

Khám phá

Supreme Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower fixed his generals with a grim stare. The 101st was about to be annihilated.

“I need a counterattack,” Eisenhower demanded. “How long will it take?”

The answers were unanimous and disheartening, rooted in the immutable laws of military logistics:

“A week, General.”

“Maybe five or six days if the weather clears. Reorganizing and moving entire armies through this weather is impossible.”

Moving massive formations—men, trucks, tanks, and artillery—in the middle of the worst snowstorm and ice storm the region had seen was simply a logistical fantasy.

II. The Audacious Promise of the Madman

Then, a voice cut through the despair—a voice familiar for its audacity, its aggression, and its utter contempt for the impossible. General George S. Patton, commander of the Third Army, spoke up from the back of the room.

“I can attack in 72 hours.”

The room fell silent. You could hear a pin drop, followed by a wave of quiet smirks and whispers. The other generals exchanged glances, convinced that Patton was either grandstanding, lying, or had finally lost his mind. His promise was not merely aggressive; it was militarily blasphemous.

Patton, a man who believed that war should be fought by the most violent means possible, was not making a promise of ego. It was the opening move in the most audacious, high-stakes gamble of the entire war—a move that would either save the entire Allied effort or destroy Patton’s career and legacy forever.

To the beleaguered soldiers of the 101st Airborne, fighting in frozen foxholes, desperately short of ammunition, food, and medical supplies, Patton’s promise was not a matter of pride. It was a matter of life and death.

III. The Madness of the Pivot

Why did every other general, grounded in logistical reality, believe Patton’s pledge was impossible?

Because Patton’s Third Army was not sitting in reserve. It was already engaged in heavy, active fighting facing south in the Saar region against the German frontier.

To execute the relief of Bastogne, Patton was proposing an act of strategic self-mutilation:

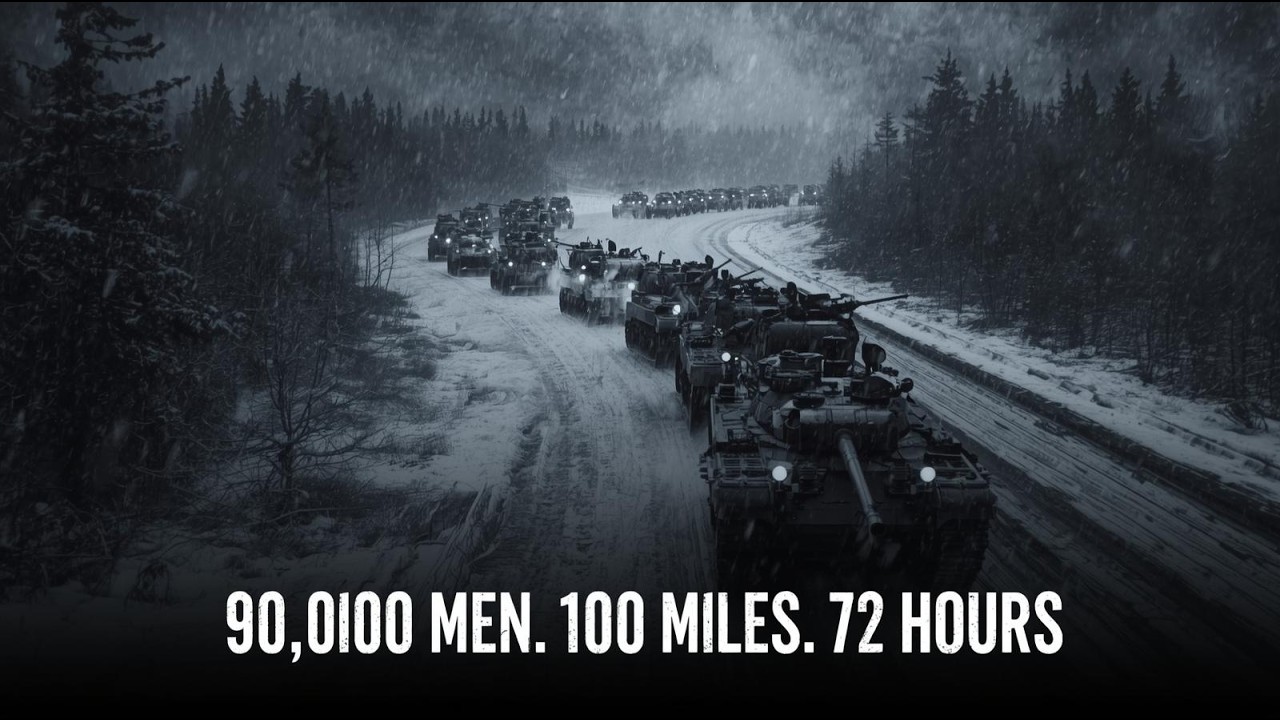

Disengagement: Pull three full divisions—over 90,000 men and thousands of tanks, trucks, and artillery pieces—out of a major, active battle.

The Pivot: Turn the entire formation 90 degrees to the left, from facing East/Southeast to facing North.

The March: March them 100 miles through a blinding blizzard, on icy, narrow, and often bombed-out roads of the Ardennes.

It was a logistical nightmare. It required rewriting traffic control plans, reassigning supply routes, and re-routing fuel lines—all in conditions that froze men in their foxholes and grounded air cover. No army in history had ever successfully performed a major strategic pivot of such magnitude in the middle of a continuous battle, let alone in the depths of winter. The German commanders on the southern flank of the Bulge were confident; their intelligence indicated that Patton was still fighting miles away. They believed they had days, possibly a week, before any relief force could possibly arrive.

IV. The Secret: Obsessive Preparation

Patton’s confidence was not recklessness; it was the result of obsessive, proactive preparation—the secret weapon that set him apart from his peers.

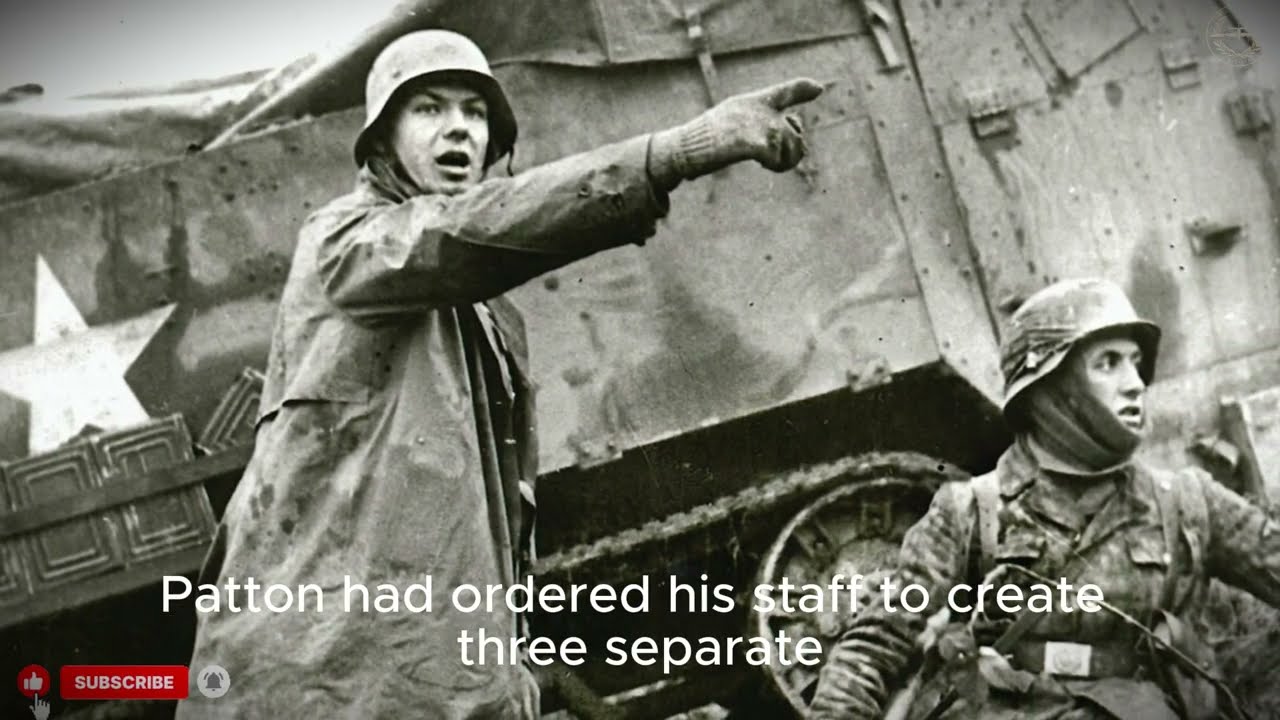

For weeks, while every other command staff focused exclusively on the battles directly in front of them, Patton had ordered his own staff to create three separate, secret contingency plans for various worst-case scenarios.

His philosophy was clear:

“Always have a plan for what you’re going to do if the guy on your flank runs.”

Patton believed that an army was like a flowing river: it is easier to redirect a flowing river than to start a still one. His Third Army was already moving, already supplied, already manned. They just needed a new direction and a new target.

When Eisenhower gave the call, Patton’s staff didn’t waste a single minute planning from scratch. They pulled a ready-made, detailed plan off the shelf, updated the time-tables, and gave the most stunning command in modern military history: “Go.”

V. The River of Steel Turns North

What happened in the next 72 hours became one of the greatest feats of military logistics in history, a staggering combination of disciplined chaos and sheer willpower.

The command was issued, and the entire logistical machine of the Third Army began to turn. The pivot required the synchronized movement of men and machines across three main axes:

The Road Network: Traffic control was the immediate challenge. Engineers worked frantically in the snow to clear roads and lay temporary bridges. Military police, often working without sleep, redirected thousands of vehicles, transforming southbound supply routes into northbound attack corridors.

The Fuel & Supply Line: The entire supply chain—fuel, ammunition, and rations—had to be rapidly flipped. Normally, this process took weeks. Patton’s quartermasters achieved it in days, often using the very trucks that had just delivered supplies to the southern front to immediately load new supplies and race north.

The Human Factor: The hardest part was turning the men. Three divisions, weary from heavy fighting, were ordered to halt, turn their attention to a new enemy, and begin a forced march in the bitter cold. The mental shock and physical exhaustion were immense, yet Patton’s army, known for its discipline and speed, complied.

Imagine the sound: thousands of tank treads grinding on frozen, icy roads, the coordinated roar of countless truck engines, the sheer, unrelenting coordination of 90,000 men and 18,000 vehicles moving as one massive, unstoppable spearhead through a blizzard.

Patton himself drove the pace, demanding relentless efficiency. He ordered his staff to clear the roads of anything that slowed them down, including vehicles disabled by ice or cold. His army was moving at a speed that simply did not exist in the operational manuals of the German High Command.

VI. December 26th: The Hammer Blow

The German commanders, secure in their belief that the Americans were bogged down, were planning the final assault on Bastogne. They calculated, based on the laws of military movement, that the earliest a relief force could arrive was December 28th or 29th.

They had no idea that a sledgehammer was about to hit them from a direction they never thought possible.

On December 26th, 1944, just four days (96 hours) after Patton’s impossible promise, the impossible happened.

The tanks of Patton’s Fourth Armored Division—the spearhead of the Third Army—crashed through the German lines. They shattered three elite Panzer divisions standing in their way, breaking the siege perimeter. The lead tanks rolled into Bastogne and linked up with the battered, frozen, but unbroken men of the 101st Airborne.

The moment was more than tactical; it was a profound psychological blow. The German offensive, which Hitler had believed would win the war, was broken by an army that moved faster than the very laws of war allowed.

The famous German demand for surrender at Bastogne, met by General Anthony McAuliffe’s single-word reply, “Nuts!”, had been rendered meaningful by Patton’s timely arrival. The 101st had held the line; Patton had saved the line.

VII. The Legacy of Audacity

Patton’s 72-hour pivot was a decisive moment in the war. It didn’t just save a single division; it triggered the immediate collapse of Germany’s offensive momentum on the Western Front. Hitler’s last gamble had failed. The German Wehrmacht was broken, not by a slow, grinding battle, but by the sheer, unbridled audacity of one man’s promise and the brilliant, invisible logistical framework that supported it.

Patton’s achievement redefined the limits of what a mechanized army could accomplish:

Mobility as a Weapon: He demonstrated that unparalleled mobility could be used not just for flanking but as a direct weapon to surprise and shatter enemy expectations.

The Power of Contingency: His reliance on pre-made, “off-the-shelf” plans proved the invaluable nature of anticipation and preparation in military leadership.

Leadership and Will: In an atmosphere thick with despair and impossibility, Patton alone possessed the will to demand the absurd and the leadership to make his men believe they could deliver it.

They called him reckless. They called him a madman. They laughed at his plan. But in the frozen forests of Bastogne, history called him a victor. And there, he proved that the line between genius and insanity is sometimes measured not just in hours, but in the sheer, revolutionary force of a single, unwavering will.

News

They Mocked His ‘Mail-Order’ Rifle — Until He Killed 11 Japanese Snipers in 4 Days

🎯 The Unconventional Weapon: How John George’s Civilian Rifle Broke the Guadalcanal Sniper Siege Second Lieutenant John George’s actions…

“They Tried to Erase Me from the Family Celebration—But My Military Power Left Them Speechless”..

“Didn’t you used to play waitress?” Aunt Kendra’s laugh cut through the air like broken glass. I froze in the…

During my grandmother’s 85th birthday celebration, my husband suddenly leaned in and whispered, “Get your bag. We’re leaving. Don’t ask, don’t act weird.” I thought he was being dramatic… until we got in the car, he locked the doors, and his voice trembled: “There’s something really, really wrong in that house.” Ten minutes later, I called the police—and what they found sent my whole family into chaos.

During my grandmother’s 85th birthday celebration, my husband suddenly leaned in and whispered, “Get your bag. We’re leaving. Don’t ask,…

At the Divorce Hearing, My Husband Tried to End Our 20-Year Marriage—Until My 8-Year-Old Niece Walked In With a Video That Changed Everything

I never imagined my marriage would end in a cold, clinical courtroom. Twenty years of shared mornings, quiet dinners, and…

THEY KICKED ME OUT OF THE INHERITANCE MEETING—NOT KNOWING I ALREADY OWNED THE ESTATE

Part 1 Some families measure their history in photo albums or keepsake boxes. The Morgan family measured theirs in acres….

Mom Gave My Inheritance To My Brother For His “Dream Life”… Then Learned The Money Had Conditions

PART 1 My mother handed my brother a check for $340,000 on a warm Sunday afternoon in March, at the…

End of content

No more pages to load