Part I — The Sentence That Changed the Room

Kennedy didn’t mean to hear it. He wasn’t snooping, not then, not yet. He’d come home late the way he’d been coming home late for months—tie loosened, laptop heavy, shoulders sore in that tired, honest way that comes from hours and spreadsheets and managers who say great work with the urgency of people shoving you toward another task. He made it as far as the hallway, as far as the half-closed kitchen door.

Inside, Amanda’s voice bounced off the tile like a bright coin. Veronica’s voice, lower, softer, moved around it carefully.

“I regret marrying my husband,” Amanda said, as if she were trying on a coat for size. “I should have chosen his friend instead. Scott—he’s the kind of man you build a life with.”

Silence. A glass set down on the counter. Veronica cleared her throat. “Amanda…”

“I’m serious,” Amanda insisted. “Sometimes I look at Kennedy and I want to shake him. He’s… stuck. Safe. Ugh, safe. When Scott posts photos from Dubai or whatever skyline he’s winning at this week, I get angry at God. Like, what did I do wrong? I picked the wrong man.”

Kennedy felt the sentence more than he heard it. It hit his chest like a door slamming. He flattened his hand on the wall and felt the cool paint steady his palm. Amanda laughed then, the lighter, brittle one she saved for mornings with mimosas or evenings when she’d decided the wine had been worth opening. “Anyway,” she added, airy, “that’s terrible. Don’t look at me like that. I’m venting.”

Veronica hesitated long enough that Kennedy thought he could hear her choosing her next word. “He’s a good man,” she said finally. “You know that.”

“Good isn’t enough,” Amanda shot back. “Good doesn’t pay for rooftop parties. Good doesn’t look like power.”

“It builds things,” Veronica said quietly. “You can live inside things that are built.”

Kennedy backed up a step and made his shoes sound on the hardwood. He opened the front door and closed it again like a man arriving. He came down the hall jangling his keys. “Anyone home?” he called.

By the time he walked into the kitchen, Veronica had tucked her legs under her on the barstool and Amanda had her bright face back on. “There you are,” Amanda said, too quickly. “Veronica brought over that soup I like.”

Kennedy kissed his wife’s cheek. “Smells good,” he said, and looked at the friend whose eyes didn’t quite know where to land.

That night, Amanda fell asleep with her phone in her hand. On the screen, Scott stood on a balcony beside an impossible city, his caption about grindsets and gratitude littered with hashtags. In the blue phone-light, Kennedy watched the slope of Amanda’s mouth and wondered how long she’d been keeping score between a life and a feed.

He wished he could say he rose from that sentence a better man. He didn’t. He rose with a small, hard smile that felt like a secret.

The next mornings came as usual: cereal bowls clinked, traffic sighed on the road beyond the window, the boss sent emails that translated to less with more. But beneath the static of normal, something in Kennedy had clicked into place. He had always moved like a careful man does—double-check the locks, run the numbers twice, bring the extra charger. Now he moved like a man who had learned that careful can be a weapon if you sharpen it.

He started taking the late calls nobody else wanted. He stayed on after the call ended and asked the client questions about appetite and timing and whether appetite could be turned into timing. He said What if? and We could and Let me run a model, and when the model came back clean, he said When do you want to move? He left the office as the cleaning crew rolled their carts down the hall and walked to his car with his jacket over his shoulder and his sleeves still rolled.

His friend—not that friend—named Jay invited him to a “small thing” in a glass box downtown. Kennedy went in the suit he wore for weddings. He ordered a club soda with lime because clarity was going to be expensive. He stood by a window and asked an older man about spreads like he had grown up staring at tickers instead of under a Buick with his father’s hand on a stubborn bolt. The older man introduced him to a woman named Elena who introduced him to a man named Hayes who said the words family office and off-balance opportunities like prayers.

Kennedy listened the way quiet people do—without waiting for his turn to speak—and found himself asked to sit in on calls that would have made the version of him from six months ago swallow and say, let me loop my manager in. He did not loop anyone in. He bought three new suits and let the tailor put his hands on his shoulders and say there, now you stand like you mean it.

At home, Amanda noticed that he smelled faintly of something she didn’t own—citrus with a shard of pepper—and that his jaw had learned how to be set without defiance. She noticed that when she sighed at a mess, he moved toward the sink without the little scramble that used to come with appeasement. She noticed that when she mentioned Scott, that old nervous laugh hopping in her throat like a trapped sparrow, Kennedy’s face did not betray anything but polite weather.

She did not know what to do with that.

Veronica called the next week and the week after, at the hour when the day had put its shoes on the mat and was standing in the foyer wishing you’d thank it for arriving. She asked him how he was holding up. She didn’t say I heard and he didn’t say me too, not at first. He talked about numbers, then about the way numbers are just stories cowardly enough to hide behind digits. He admitted the night in the hallway. “I don’t know how to forgive that sentence,” he confessed, thumb pressed into his eyebrow like a man stopping a headache by thinking at it.

“Amanda vents,” Veronica offered.

“Venting is letting air out so the building doesn’t explode,” he said. “This felt like mapping out the architecture of a different house.”

There was a pause in which he could hear her move the phone from one ear to the other. “You’re not worthless,” she said then, careful and firm. “You’re a good man.”

He almost laughed. Good isn’t enough, the kitchen had already taught him. “Thank you,” he said, and meant it more than he was proud of.

They talked later that week, after Amanda went to bed with the blue light of other people’s lives ghosting her cheek. “I saw your name on a list today,” Veronica said. “Sponsorship for that community fund. Kennedy… that’s you?”

“It’s the firm,” he said. It wasn’t a lie. It wasn’t the truth either. “They’re letting me take point.”

“You’re different,” Veronica said softly.

“Sometimes change is the only way to survive betrayal.”

“I didn’t know I was capable of it,” she admitted. “Changing. Looking at someone and wanting them to do better and also to win.” The honesty made his chest ache and ease at once.

Amanda drifted into the kitchen as he hung up. She wore a silk robe the color of pomegranates and smiled with the right corners of her mouth. “You’ve been distant,” she murmured, surprized at how familiar the script felt even as she said it. “Don’t you miss us?”

“I’m working,” he said simply, not unkindly, and picked his laptop back up.

The rebuff did not enrage her. It unnerved her, a difference that felt like being on a boat at night: the water looked flat until it didn’t, and then you realized the dark under you had weight. She poured herself wine and decided to be gentle. She reminded herself that men liked softness more than edge. She almost called Scott for nothing but a chord of laughter, but remembered that life had spun an odd loop lately: Kennedy started appearing in the backgrounds of photos that featured Scott.

She discovered the partnership at her usual altar—a square of curated lives on her phone. There they were, shoulder to shoulder under chandeliers, the caption about shaping futures and the smile on Kennedy’s face not the humble, grateful one but the one she loved on strangers: a man’s mouth when he sees exactly where he is and does not have to pretend anymore.

“Are you working with him?” she asked the next morning, casual, only the slightest tremble.

“Yes,” he said, pouring coffee. “It’s just business.”

She tried a laugh. “That’s… huge.”

He lifted his mug to her as if toasting a fact. “I told you,” he said. “I’m not the same man.”

Amanda carried her cup to the sink where once he would have leapt to carry it for her and thought, for the first time, of what it would mean if he took his new self and sprinted toward a door without looking back to see if she was coming.

The edge between Veronica and Kennedy kept wearing down through repetition. They told each other small, safe truths and then graduated to the risky ones: childhood embarrassments, making peace with parents, the way loneliness sits on a chest and calls itself sleep. The people who can break you the worst, Kennedy thought, are not the ones who climb into bed with you first. They’re the ones who climb into your sentences and decide to live there.

He asked Veronica to lunch “to talk about Amanda,” but they talked instead about the way people fold and unfold in rooms. “I think you deserve someone who sees you,” Veronica said, words catching at the edge of her throat like a knit snagged on the corner of a table. “Someone who doesn’t dream out loud of a parallel life.”

“What do you think you deserve?” he asked.

She didn’t answer that one.

Rain pinned the day down one night a month later. He closed the garage and saw a shape move under an umbrella near the curb. He slid into the passenger seat because the driver’s side felt too much like acknowledgment. The car smelled like rain and Veronica’s shampoo. They sat for a while and listened to the closest version of silence a city can manage.

“We can’t keep doing this,” Veronica whispered. “She tells me everything. I’m stealing you from my best friend in pieces, one quiet night at a time.”

“She longs for Scott in the afternoons and I watch her do it,” he said. “What name do you give that theft?” He turned then, and the look that passed between them contained so much of what they had said and swallowed that it nearly made noises with its own weight.

Veronica leaned toward him and stopped. He closed the distance. He tasted rain and something like mercy. It was not gentle. It was not savage. It was something else—agreement, maybe, or a decision not to lie to their own bodies about what their brains had already signed off on.

In the sober shimmer after, they didn’t talk about betrayal. They didn’t talk about forgiveness. They talked about lunch for tomorrow. They talked about a book. They laughed at something dumb and then went home because you still have to sleep even when you upend a life.

Summers are for overtures—charity luncheons in rooms with bad acoustics and better art, handshakes that promise to remember the next handshake. Two weeks after the lawyer came to the kitchen table with the envelope, Kennedy stood in front of a mirror not his own and let a tailor fuss at his shoulders. He tied the tie himself. He buttoned the jacket. He slid the phone into his pocket where it would buzz with messages from men who finally were ready to hear him say no.

He picked up Veronica.

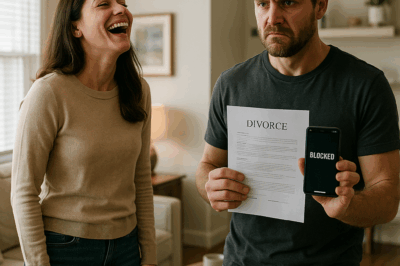

Amanda already had a dress for that night long before the mailman carried the envelope up the walkway. It fit the way dresses fit when women need hope to hold still for a couple of hours. When she saw them—Kennedy in something cut like command, Veronica in a black that meant restraint instead of mourning—she misjudged her hand and the champagne flute leapt out of it and shattered on marble. She did not blush, did not apologize, did not look down. She looked at him and something like recognition clattered inside her.

He waited until the room forgot to watch. Then he went to the balcony because sometimes closure deserves air. She followed because of course she did. She said, “You brought her,” like she hadn’t brought her words to the kitchen herself months ago.

“You brought Scott to our table every night,” he said. “I brought truth to a gala.”

It wasn’t the line that broke her. It was the tone—no plea in it, no anxiety. It was a man closing the book he had been reading against his own will because he had finally remembered he could stand up and leave the library.

“Please,” she said, and meant it in all the ways people mean it when the thing they have counted on stops waiting for permission.

“No,” he said, as gently as a no can be said.

Behind her, in the doorway, Veronica hesitated. The shape of her guilt hung on her like a shawl she could shrug off in a darker room. Amanda’s voice found Veronica’s name and threw it like a brick that never reached the wall.

“You betrayed me.”

“I didn’t mean to,” Veronica said—small truth, small defense, ridiculous in a room with that much money in it. “I… chose him.”

“No,” Kennedy corrected. “I chose not to be small anymore.”

The city did its glittering indifference. Somewhere in a kitchen a man with a towel over his shoulder cursed a sauce. Somewhere in a lobby a woman checked her phone and hoped the person who wasn’t texting her was busy doing something that could be forgiven. On the balcony, Amanda recognized a lesson late enough that it would hurt harder for being accurate.

He had laid the groundwork. He had built something out of paper and risk and rage that had cooled into resolve. He would file the papers and with them everything else he had filed in his chest: a lifetime of getting out of his own way. He would close the door and he would not slam it, not because he was kind or cruel, but because slamming would imply he still expected someone to chase it open.

“Everything we built,” she tried, last lever, worst lever, the one people pull when they have already yanked the others off the wall.

“Everything I built,” he said. “You didn’t want to live inside it.” He turned the handle, then stopped and looked at her. “You will survive this. You will convince people it was my fault because that is what hurts less than admitting the truth. Practice saying we wanted different things in a mirror. It will sound brave. That can be true later.”

He walked back into the room with Veronica by his side and let the light of other people’s approval fall across him like the least necessary blessing. He shook hands with men who finally met his eyes. He took photos with Scott, who might have been thinking about a balcony in Dubai or might have been thinking about the game score on his phone. It didn’t matter.

He had already decided how this would end. The rest of the world was just catching up.

Part III — Blueprints, Countermoves, and the Fallout (≈1,750 words)

Kennedy woke before the sun because mornings respect the disciplined. He made coffee in the quiet kitchen of the apartment he had leased on a month-to-month just far enough away to feel like distance without turning into escape. The steam curled, a vertical thought, while he spread his files across the table—tabs blue for business, red for litigation, green for personal. He didn’t love color coding. He loved what it did to chaos.

The attorney he had retained—Langston Pierce, a man who spoke in precise nouns and only used adjectives like scalpels—had asked for timelines. Kennedy gave him timelines that looked like scaffolding: the night of the sentence in the kitchen; the first meeting with Elena and Hayes; the LLCs formed for ventures Amanda would never have believed; the account statements that proved her favorite word, just, had never belonged to finances.

“Do you want to punish her or be free?” Langston asked on their first call.

“Why not both?” Kennedy had said, surprised at hearing the pettiness leave his mouth clean.

“Because the first erodes the second if you’re not careful,” Langston replied. “In court, revenge looks like erratic. Erratic looks like dangerous. Dangerous loses.”

So they filed. Fault-neutral on the surface, because judges prefer civilized, backed by a motion for exclusive occupancy that read like a calm storm—a marriage of furniture and facts. They petitioned to separate finances, to audit transfers that left their household account at irregular intervals, to secure temporary orders for spousal support that would last exactly as long as the law required and not a day more. They attached an affidavit that documented Amanda’s own words: I regret marrying my husband. It wasn’t cruelty. It was a mirror.

He texted Veronica at six for nothing but a good morning he had no right to say. She sent back a sun emoji and then, after three dots hovered and disappeared and returned—I have to tell her. Not everything. But I can’t sit in rooms with her and lie anymore.

He wrote, Okay. He deleted it. He wrote, I won’t ask you to, and sent that instead. The word ask did something to his throat. He’d spent a decade being the person who asked, gently, properly. He was learning that asking had to be reserved for sacred things.

Amanda negotiated with disbelief for three days. She called three different friends who liked her more at brunch than in the middle of a weekday crisis. She called her mother, whose comfort was a vintage sweater: soft in theory, itchy where it mattered. She called Scott and did not leave a voicemail.

On the fourth morning she woke with a headache that felt like ambition’s hangover. When she turned her phone over, there was a message from Scott.

S: Saw you at the gala. You okay?

She typed and erased three versions of He did this to hurt me. She wrote instead, A: We’re separating.

He answered with a clocked delay as if he were measuring decency against curiosity. S: I’m sorry. If you need a lawyer, I can recommend some.

She read it twice, searching for a prose poem that wasn’t there. No invitation. No confession about the balcony in Dubai. Just a business card in text form. She put the phone down with that cold calm that follows nausea and looked around at the home she had curated with an eye for shots that would do well online: the lamp that made nights look warm, the art in the hallway that never once had to beg to be noticed.

A key turned in the lock. Kennedy stepped in—not in apology, not in attack. He was there for one reason: to collect the last things that belonged to the man he had been. He moved through the living room with a respect absent of anxiety. Amanda stepped into his path because that’s what you do when you suddenly realize walls are not doors.

“You can’t end us like this,” she said. If she’d cried, maybe, it would have been something else. But Amanda came armed with adjectives.

“I already did,” he said. It wasn’t cruelty. It was math.

“You’re doing this for her,” she said, as if Veronica were the whole equation. “You want to humiliate me.”

“I’m doing this for me,” he said. “I want to live with myself.”

She stared at him as if she had to translate. “What kind of man leaves his wife for her best friend?”

“The same kind of woman,” he said evenly, “who sits in her kitchen and tells her best friend she married the wrong man.” He held her gaze. “I am leaving the version of us that kept you comfortable at the cost of making me small.”

She made a choking sound she would describe later to friends as a laugh. “You were always small.”

He smiled in a way she could not read. “And yet,” he said, gesturing in the general direction of his new life.

He left with a garment bag and two boxes. He left the house smelling like something Amanda didn’t own.

Veronica had imagined confession with a soundtrack—somber strings, rain against a window—and instead it happened on a Tuesday in sun that lingered on dust motes like kindness. She poured iced tea because she needed something to do with her hands. Amanda sat at the table and stirred a glass that didn’t require stirring.

“I need to tell you something,” Veronica began, and the words tasted like metal the way truth does when you’ve kept it behind your teeth too long.

“If it’s about him,” Amanda said quickly, “save it. I can’t—” She stopped. “Actually. No. Tell me. Is it true? Have you been…?”

Veronica set the spoon down with ridiculous care. “Yes,” she said. “I’m sorry.” A breath. “I’m not sorry for loving him. I am sorry for lying to you.”

Amanda’s mouth worked around three words that never became sentences. “How—when—why?”

Veronica said the only thing that wasn’t destructible. “Because he sees me.”

Amanda’s face rearranged itself into a mask Veronica had seen before—a look that made Amanda untouchable at patio tables—but this time there was water behind it. “I don’t forgive you,” she said. “Not today. Maybe not ever.”

“I know,” Veronica said, and when Amanda stood abruptly and knocked the glass over, the tea ran under the calendar Amanda used to forget she wasn’t as busy as she claimed, and the two women stared at it, transfixed by the way sugar water maps tile.

After she left, Veronica sat with the wreckage of a friendship like a demolition site with tulips blooming nearby. Kennedy texted, How did it go?

She wrote, It hurt.

He typed, I’m sorry, and meant it, but the apology felt like a ribbon on a grenade.

Scott invited Kennedy to lunch “to catch up,” a phrase men use when they want to see which direction the wind favors. The restaurant was the kind where the servers remember your drink and never let you put your napkin on your lap because they do it for you. Scott talked first—deals like weather reports, names like currency. “Everyone’s bullish on you,” he said finally, dropping compliment like bait.

“I’m bullish on me too,” Kennedy said, deadpan. He took a bite. “What are you actually asking?”

Scott smiled. “There’s a series I’m putting together. We need an operator. Someone with… let’s just say appetite.” His eyes flashed. “And discipline.”

Kennedy leaned back. The word operator used to belong to other men. He tried it on in his head and found it fit. “Send the deck. I’ll read it,” he said. “Then we’ll talk.”

Scott cleared his throat. “And Amanda,” he added. “I heard.” He didn’t finish the thought because he didn’t need to. Men congratulate other men in the negative space between sentences.

“We’re separating,” Kennedy said. “I wish her well.”

Scott nodded—as if “well” were a country you could buy a ticket to—and lifted his glass. “To appetite,” he said. “And discipline.”

Kennedy clinked. He couldn’t tell whether he wanted to be this man’s friend or just outrun him professionally. Maybe both. He read the deck that night and sent back four questions that made Scott add him to the list of men with whom he could skip foreplay.

Two weeks later, the first hearing in family court looked exactly like every story you tell yourself it doesn’t: the fluorescent, the solemnity, the clerk who will not meet your eye for fear you will ask her to be a person and not a function. Langston whispered the choreography. Amanda sat on the other side with an attorney in a navy suit who had learned to cock her head so empathy could sit on it without sliding off. Veronica sat in the back, because she had no place near the front. Scott didn’t come. He sent a text that said, Go get ‘em. Kennedy didn’t answer.

The judge was one of those men who learned to tuck his softness inside the chambers like a coat—long years of keeping faces flat. He listened to Langston lay out the temporary orders—financial separation, use of the marital home, exchange schedules that turned love into calendars. He listened to Amanda’s counsel argue that this was abandonment in designer clothing. He turned to Amanda and asked the question judges ask that sounds like harm: “Do you want to respond?”

Amanda looked at the ceiling, which in court is no help. She said, “I said terrible things. We said terrible things. That doesn’t mean you get to end a marriage. It means we’re married.”

The judge said, “It means you’re people,” which is not the same thing as “It means you remain married,” and granted the orders. He said the word “equitable” three times, which is legally profound and emotionally hollow. He set a mediation date and reminded them both that the court prefers civilized in public even if civilized at home died two years ago in a kitchen under a speech.

Outside, Amanda stood on the steps and pretended not to look for cameras. Veronica kept her distance at the base of a statue of someone who no longer deserved one. Kennedy stood in the wind that surfaces around courthouse corridors and felt himself become the thing he had designed: a man who moves forward even when the stories people tell about him lag behind.

He didn’t go home with Veronica because he understood impulse better now. He went to the office. He read a term sheet like it was a map. He drew a line through a clause and wrote a sentence that made three men in two cities revise their models. He got on a plane and slept because sometimes the bravest thing you can do at 32,000 feet is let your body do the boring miracle of being alive.

Amanda’s counselor asked her, halfway through the second session she attended because her lawyer told her to, whether she wanted to be right or to be well. Amanda said, “I want both,” and the counselor did not laugh because good counselors never do when you lose to the obvious. They went back to one Tuesday in a kitchen.

“Why did you say it out loud?” the counselor asked, tone so gentle it made the question shareable. “To Veronica of all people.”

“Because it felt true,” Amanda said. “And because Scott’s life looked like the one I thought I’d live.”

“Instagram is a liar and so are fantasies,” the counselor said. “Were you in love with Scott or with a version of yourself that never had to endure a man growing next to you?” She wrote something down and later, in the car, Amanda would hate her for it and realize she was right.

Amanda reached for her phone during a green light and caught herself. She pulled over and typed, K: I don’t forgive you. But I’m going to stop making you the villain in my head because it’s making me uninteresting. She stared at it. She didn’t send it.

Instead, she texted Veronica, You broke me, and put the phone face down on the passenger seat like a small animal she did not trust.

Veronica wrote back after an hour. I know.

Amanda did not answer. That evening she unfollowed Scott and then followed him again and then muted him, which is worse than blocking for the blocked. She poured a glass of wine and did not drink it. She watched a show and turned it off when the characters did a version of her life badly. She fell asleep on the couch without washing her face and woke with a line on her cheek that looked too much like a scar to be nothing.

Kennedy did not propose to Veronica. Not that week. Not that month. He moved her toothbrush into his apartment because intimacy is the actual test, and he learned that she hummed when she loaded the dishwasher and that she scolded the plant for being dramatic and that she said my heart is full like a child and then made fun of herself for it like an adult. He told her he was not ready to turn the world into a wedding for the sake of ceremony. “When the papers are signed,” he said. “We’ll see if we still want this.”

She loved him more for the conditional.

He called Scott and told him he was in for the series but only if certain terms were non-negotiable. Scott laughed in a way Kennedy would one day come to love or leave; for now, he respected it. The deal closed. The article with both their names in it went live on a Friday, which is when people post good news to get better questions.

Kennedy’s name trended in their small corner of the city. Old acquaintances from high school sent messages full of the kind of generosity that comes easily to people who do not need to prove they had believed in you all along. He wrote back to the ones who mattered with bullet points and to the others with thumbs-ups because he had learned some communication belongs to economy.

He slept through the night for the first time in months and woke because the sun was laying its hand on the floor just so, and Veronica was twined in the sheet like a sculpture of safety, and he was a man who could look at all of it and not feel like he had stolen it.

It wasn’t happiness. It was steadiness. It was better.

—to be continued—

Part IV — The Last Door, The Last Word (≈1,750 words)

The mediation fell in late autumn, the city trying on that particular gold it wears just before it remembers winter. They met in a room designed to be neutral: curved chairs that suggested holding without hugging, watercolor art that suggested landscape without insisting, a pitcher of water always full. The mediator, a woman with a hairstyle that didn’t move even when the room did, began with the rules.

“You can’t interrupt,” she said. “You can write things down to say later. You can ask for a break. You can leave. But know that leaving triggers court, and court turns the choices you make into the choices someone else makes for you.”

Amanda nodded like a student. Kennedy folded his hands. Veronica waited downstairs because everyone insisted she not be the subject and make the subject worse simply by her presence. Scott sent a flame emoji to a group chat with two other men and then felt embarrassed by himself for thirty seconds before going back to a model that didn’t care who was there when numbers agreed.

“House?” the mediator asked.

Kennedy didn’t make it an argument. “She keeps it,” he said. “I’ll take the equity discount we agreed on on Langston’s sheet. The kids don’t have to pack and unpack their lives because two adults were careless with each other.”

Amanda blinked. She hadn’t expected generosity. She hadn’t expected indifference either. “And the lake times?” she asked, a phrase they had inherited from families who split summers like fruit.

“We’ll do even years for August,” Kennedy said. “Odd for July. Holidays alternating; birthdays split with time for both. Wednesday dinners forever. If you move, we revisit everything.”

The mediator scribbled like someone physically carrying the deal into existence. “Vehicles?”

“Keep your car,” Kennedy said. “I’ll keep mine. I’ll pay it off this quarter anyway.”

“Retirement accounts?” the mediator asked.

“We’ll split the contributions since the day of the wedding,” Langston cut in smoothly. “Growth calculations here,” he passed a sheet, “and here.”

Amanda listened to numbers doing what numbers do and felt an unexpected relief—a world with rules. She wanted to throw a fork at them anyway.

“Alimony,” the mediator said.

“Statutory,” Langston said. “Twenty-four months. It ends earlier if she remarries.” He didn’t look at Veronica. He didn’t have to. The fact of her existed just fine without looking.

“And the narrative?” the mediator asked softly, which was not a legal term but a real one. “How will you speak of this…to them?” She meant the children that had not come into this story because this story had been busy performing in rooms where children didn’t belong.

Kennedy exhaled. “We’ll say we wanted different things,” he said. “We’ll say it wasn’t anyone’s fault. Then we will say nothing else because their lives are not the place to absolve ourselves. We will add that we both love them, which will not be entirely true on some Mondays but will be true enough on Saturdays. We will not rehearse our pain in front of their appetites.”

Amanda looked at him as if he had reached into her chest and found a muscle she had forgotten the name of. She nodded once. “We will also say we are sorry,” she added, surprising herself. “We will actually say it to them and not in our heads while we wait for applause.”

The mediator’s pen paused. “That’s rare,” she said dryly. “Write it down while you mean it.”

They signed things that made muscle official. They walked out into a hallway that preferred echoes over applause. Veronica looked up from the chair where she had been calculating a timeline of a different sort—When does it become ethical to be happy?—and put her hand in Kennedy’s because holding does not always have to be performed.

Amanda watched just long enough to understand that the scene was not a mirror. She went home to the house that now was the house and sat on the floor in the middle of the living room and cried like a person who had finally given herself permission to be a person. Then she stood up, washed her face, and called her mother. “Don’t come over,” she said. “I’m fine.” It was the first time she had used the word and meant it as in process and not as leave me alone with my damage.

The final hearing in family court was, in the way endings often are, undramatic: a judge who had lost none of his ability to be bored in the presence of other people’s most important day. He ratified the mediated agreement. He complimented both counsel on being “professional.” He wished everyone luck with the kind of tone you use when what you mean is I expect to see you again for modifications in two years but will enjoy the interim where you are someone else’s responsibility. He banged a gavel softly, as if the wood could feel.

They left separate. Outside, the sky did its big trick—existing without caring. Kennedy walked two blocks to where Veronica had parked and slid into the passenger seat, an old habit that felt like politeness more than secrecy now. They didn’t speak for two lights. At the third, he turned to her and said, “Not tonight,” and she loved him more for drawing the boundary around their joy.

“Okay,” she whispered. “We’ll go slow.”

He took her hand anyway. A traffic cop waved people through an intersection like a conductor. The city made noises. His thumb made a small arc on the back of her hand as if underlining a sentence they hadn’t written yet.

Three months later, Kennedy launched a fund of his own, not with fireworks, but with the simple sight of a new brass plate next to a door that used to have someone else’s name. The first investments went to the unshowy businesses that build cities while getting almost no credit: a paving company that figured out how to make asphalt with less shame; a logistics firm run by sisters whose parents had broken their backs pushing carts; a software shop that sold tools to plumbers. “Less sizzle, more steak,” he told a room of men who had worn their best sizzle to impress him, and they had nodded like they’d invented prudence.

He hired two analysts from neighborhoods Scott’s firm considered charity work. He put a photo of his father under the glass on his desk and another of his mother across from the coffee machine because she had taught him how to keep a room honest without raising her voice. He put nothing of Amanda on any shelf because the version of her who would have wanted to be there had left a long time ago.

He went to Veronica’s as often as he stayed at his place until one cloudy Sunday she looked at him over takeout and said, “If you move a second suit into my closet, it becomes a story, and I want to write that story slowly.”

He laughed. “That sentence,” he said, “is why I love you.”

She put her foot on his shin and rolled her eyes and told him to pass the dumplings.

Amanda joined a nonprofit after six weeks of pretending being fine alone paid as well as being useful. She didn’t do PR because the story being told was not yet ready for her voice. She did intake—forms and faces, the hard art of letting people tell you what hurts without interrupting to insert your own script. She became good at difficult adjectives: housing insecure, food insecure, recently displaced. She learned people’s names by writing their stories on file tabs and, for once, not curating, just recording. She threw her phone into the couch and forgot it there at least twice a week.

She went to therapy. She did not apologize for money spent on sessions because it turned out paying someone to teach you how not to destroy your own rooms was the most adult thing she had done. She watched the envy she’d curated for years turn into something smaller, something that could be forgotten for hours at a time. She unfollowed, muted, blocked, and—finally, one windy afternoon—deleted Instagram and did not perform the deletion online. She joined a ceramics class because her counselor said making ugly bowls would be good for her. She made three ugly bowls and then one that surprised her enough that she cried in a car in the parking lot holding a shape that had not existed until she insisted, gently, that it should.

She texted Kennedy on a Thursday evening in March: Thank you for not making me the villain to our friends. He wrote back an hour later: Thank you for not making me one to the kids. It was the first time they had been kind to each other via math—one for one. She slept without wine that night and woke with a headache anyway, but the kind that goes away with water and honesty.

Scott stayed in the story as a satellite. He and Kennedy did three deals, then one they both hated, and then one that made them say “huh” at the exact same time. They became the kind of men who could text each other at 11 p.m., What do you make of macro this quarter? without attaching a preamble. Scott saw Amanda once at a fundraiser and kissed her cheek with a gentleness that made her want to throw a glass and then made her want to say thank you. She said neither. He said, “You look good,” and she said, “I’m learning things I had to learn,” which was the truest thing she had said to any man at a bar in her adult life.

He went home with a woman who would never be tagged on his feed and thought, not unhappily, about being human.

On the anniversary of the gala, Amanda took a cab to a rooftop she used to use to calibrate her desire for a life she didn’t have. She sat at the high-top with a friend who had survived college with her, years neither of them liked to talk about. “I hurt him,” Amanda said, before the friend could ruin it by asking about everything else. “He hurt me back. Then he stopped. Now he’s someone I want to be proud of and hate that I want that.”

The friend snorted. “That’s adulthood,” she said. “We contain complicated.”

Amanda laughed, for real this time, and ordered fries even though she had once insisted fries were a mood and not a food. They tasted exactly like the thing she needed.

Kennedy proposed on a Tuesday morning because Tuesdays don’t get enough credit for bearing good news. He laid a ring box on the table next to a stack of research notes and a pen that had just run out. “We can say no,” he told Veronica, unexpected, godly. “To hurry. To people who want a story to soothe themselves. We can say yes next week or in five years. I just want a relic of an intention.”

She opened the box. The ring was a small diamond set low—nothing like Amanda’s friends had posted when they catalogued their engagements on social. It looked like a promise to be careful; like a rock a person could hold when the ground moved. She said, “Yes,” and put it on, and they both felt something ease—perhaps not a burden, but the need to explain themselves to rooms that weren’t invited.

They got married six months later in a courtroom with a judge who had the good humor to say, “This is my favorite part of the job,” and mean it. They didn’t invite anyone except two witnesses who were coworkers and laughed when the pen ran out. They went to lunch at a place that didn’t mind if your crown was crooked. They texted no one. They posted nothing. They went home and made spaghetti with the volume turned down because he had learned to love that sound.

When the first baby arrived, Amanda brought a blanket to the hospital that she had bought at a thrift store with a tag that made her wince—NEW LIFE—and gave it anyway. She stayed fifteen minutes because that was the amount of time that belonged to a scene like this. “She’s perfect,” Amanda said. Kennedy held his daughter the way men hold both their hearts and their histories. Veronica slept. The nurse adjusted the IV. The world, rude, continued.

On the way out, Amanda passed Scott in the hallway. He had flowers that someone else would take home because men like him don’t know what to do with them. He smiled. She shook her head. They kept walking.

Outside, the air had that particular light you can’t catch even with excellent cameras. Amanda took her phone out and didn’t take a picture. She stood there very still, as if the city were a dog she didn’t want to startle, and felt something like gratitude rest next to her spine.

Years later, people would tell this story at tables with better lighting and worse motives: She said she regretted him, and he became more than she could have imagined, and then he left. They would cast Veronica as the villain or the victory, depending on which day you caught them. They would make Scott an omen, a pivot point, a myth.

They would get details wrong. Stories are like that.

This is the ending that stays true: a man learned to live inside the shape he built when nobody was clapping; a woman learned to want something more interesting than attention; another woman learned to love after breaking a thing that mattered and then kept loving responsibly; a different man kept making money and sometimes called the first for advice he actually took. Children grew up with two kitchens that smelled like pasta and boundaries. Pain cooled into memory. Memory, politely, left rooms when asked. Regret became less of a god.

Kennedy kept his first suit in the back of a closet—not to mock it but to honor the man who wore it before he knew how to stand up straight without waiting for the room to tell him he was allowed. On quiet mornings, before the train of the day began, he put his hand on the lapel and said out loud the sentence that changed everything twice.

“People change,” he’d told Amanda that day. And then, when she demanded to know in which direction, he’d told her the rest: “Sometimes they grow. Sometimes they outgrow.”

He had done both. He had not become Scott. He had become someone Scott wanted to learn from. He had not become the echo of Amanda’s ambition. He had become a person whose voice could fill his own rooms without becoming a performance.

In the end—because endings exist even when they refuse to be cinematic—he sat at a kitchen table in the apartment that had become a home and helped his daughter with fractions while his wife hummed at the sink and the city did its noise and his phone lay facedown like a perfectly trained dog.

He didn’t need to check it. The life he’d wanted was already here.

And somewhere else, in a different kitchen, Amanda turned off her phone herself, wiped clay from her hands, and put a bowl that was not ugly anymore on a shelf sturdy enough to hold it. She didn’t post it. She poured soup into it. She ate.

Outside, the light changed without asking anyone’s permission. Inside, nobody rehearsed. The last door had closed softly. The last word was not revenge. It was relief.

News

MY DAUGHTER CAME BACK FROM HER HOUSE, HER FACE SWOLLEN AND BLOODY. I HELD HER CLOSE AND CRIED… CH2

Part I — The Night of the Lie Her body gave out the moment she crossed my threshold, the way…

I Laughed That Some Of His Friends Tried Me—Now He’s Filing Papers And Blocking Me CH2

Part I Rowan spends the entire Sunday dinner being a cathedral. By the time Margaret sets the roast down and…

My daughter shaving her sister’s head before prom was the best thing she ever did. CH2

Part I You never think the sound of clippers will be the sound that saves your child. It started as…

Husband Has Baby with Sister, Dumps Me ➡ 3 Years Later, Surprise Meeting, Ex’s Shocked Face. CH2

Part I If you’d asked me to name the moment my marriage cracked, I’d say it wasn’t big. Not the…

Sister-in-law happy at funeral because my surgeon brother left her lots of money. CH2

Part I The day we buried my brother, the sun came out like it had been paid to. It turned…

“We Left My Stupid Husband Miles AWAY From Home as a JOKE, But When He Returned It Was NOT Funny…” CH2

Part I I can tell you the exact moment I should have trusted my gut. It wasn’t the tight smile…

End of content

No more pages to load