Part One

The lump appeared three weeks after my twenty-eighth birthday.

It was small, hard, and unmoving under my left breast — a pebble lodged beneath skin that had never caused me trouble before. I was healthy, ran three times a week, ate clean. Cancer wasn’t on my radar. I was a software developer at Techcore Solutions, the kind of person who believed logic and data could explain anything.

So when I felt that lump in the shower, logic told me: it’s probably nothing.

By the time the biopsy came back, logic had left the room.

“Stage 2B invasive ductal carcinoma,”

Dr. Helena Martínez said, her voice calm but heavy.

“Aggressive subtype. HER2-positive, hormone receptor negative. We need immediate treatment.”

She laid out the plan like a roadmap I never wanted to see.

Chemotherapy. Double mastectomy. Then radiation.

Without treatment, the survival rate dropped significantly within months.

I remember staring at the diagrams, nodding mechanically as if I were debugging someone else’s life.

Ninety thousand dollars. Nine months of intensive treatment. My stomach turned.

That night, I called my parents. Both worked in medicine — Dad was a hospital administrator at Riverside Medical Center; Mom ran the medical records department. My brother Tyler was a physician assistant in Riverside’s emergency room.

A family steeped in healthcare. They’d understand. They’d help me make sense of it.

“Cancer?” my father repeated, his voice skeptical. “Chloe, you’re twenty-eight. Breast cancer at your age is extremely rare. Are they sure it’s not a cyst?”

“I had a biopsy, Dad. It’s definitely cancer. Stage 2B.”

A pause — long enough for me to count every second.

“That’s borderline,” he said finally. “Could be managed conservatively.”

Mom’s voice joined the line. “Who’s your oncologist?”

“Dr. Helena Martínez. Metropolitan Cancer Center.”

Dad scoffed. “Never heard of her. Metro isn’t top-tier. Come to Riverside. Get a second opinion from someone we know.”

“I’ve already started scheduling.”

“These community oncologists overtreat to cover themselves legally,” he said. “They love aggressive protocols. You should wait. Get more opinions before letting anyone start cutting or poisoning you.”

“Dad—”

“Your father’s right,” Mom interjected. “Cancer treatment is brutal, honey. Chemo will destroy your body. You’re young; maybe monitor it first. See if it grows.”

“It’s already growing,” I said quietly. “Dr. Martínez says it’s aggressive.”

“At your age, your body’s resilient,” Mom insisted. “You might not need all that. Maybe a lumpectomy, then reassess. And Chloe, we’re planning that Europe trip in August. Three weeks. Tyler finally got time off. Can’t you schedule around that?”

“I’ll be in surgery in August.”

“Can’t you push it to September?” Dad said flatly. “We’ve been planning this for a year.”

“I have cancer.”

“Stage 2 borderline,” he corrected. “Not a death sentence. A few weeks won’t make a difference.”

That was my family’s medical consensus — not concern, not compassion, but a logistical inconvenience. They wanted to fit my diagnosis around a vacation.

Family Meeting

The following Sunday, they called a “family meeting.” Their phrase, not mine.

Riverside Medical Center had trained them to treat everything — even emotion — like a committee issue.

I sat at their kitchen table surrounded by the smell of disinfectant and coffee. Tyler arrived in scrubs, fresh off a shift.

“So,” he said without greeting me, “you think you have cancer?”

“I know I have cancer. I have the pathology report.”

He skimmed it like an email. “Okay, yeah, it’s cancer. But Stage 2B is very treatable. You’re probably overreacting to what your oncologist told you.”

“She said I need aggressive treatment.”

“She’s covering her ass,” he said dismissively. “I work in emergency medicine. I see real cancer emergencies — Stage 4, metastatic disease, people dying. What you have is early. You could probably get away with a lumpectomy. Maybe skip chemo.”

“My oncologist said—”

“She wants to bill insurance for maximum treatment,” he interrupted. “That’s how oncology works.”

Dad nodded like it was settled. “See? Tyler understands the business. Get a second opinion at Riverside before committing.”

“And really,” Mom added, “we need you flexible about timing. This Europe trip means a lot. Family bonding, you know?”

I sat there, the youngest person in a family of healthcare professionals, realizing none of them believed me. Not because they didn’t have access to the truth — they simply didn’t want it to be true.

Documentation

After that meeting, I started documenting everything.

Every dismissive comment, every text minimizing my illness, every email suggesting I delay surgery for “family priorities.”

I saved everything in a folder labeled “Medical Support Documentation,” as if labeling it clinically would dull the pain.

What they didn’t know was that Metropolitan Cancer Center was about to merge with Riverside Medical. The announcement wasn’t public yet, but I’d overheard staff whispering: Riverside had acquired Metro’s oncology department. Dr. Helena Martínez — my oncologist — would soon be the new chief of oncology across the entire Riverside system.

In three months, she’d be my family’s new boss.

Treatment Begins

Chemo started mid-June.

The first round left me violently ill for three days. I couldn’t eat, couldn’t stand, couldn’t think. My hair came out in clumps by week two. I lost twelve pounds in two weeks.

Dad called once.

“How are you feeling?”

“Terrible. The chemo’s brutal.”

“Well, you chose to do it,” he said. “I still think you’re being overtreated. Anyway, we finalized Europe — August eighth through twenty-ninth. Schedule surgery after we get back.”

“My surgery’s August fifteenth,” I said. “Dr. Martínez says we can’t delay.”

“This is ridiculous. We’ve paid fifteen thousand for this vacation.”

“I have cancer.”

“Early-stage cancer that’s not immediately life-threatening,” he snapped. “Be reasonable.”

Mom texted the next day:

“Your father is stressed about the vacation conflict. Can you work with Dr. Martínez on timing? Tyler says August vs. September won’t make a real difference.”

I showed the message to Dr. Martínez.

She looked up from my chart, frowning. “Your family works in healthcare?”

“Yes. Dad’s an administrator, Mom runs records, and my brother’s a PA.”

“And they’re telling you to delay treatment?” Her eyes darkened. “For a vacation?”

“They think it’s not serious enough.”

She pulled up my scans. “Chloe, your tumor’s grown eight millimeters since diagnosis. HER2-positive, hormone receptor negative. Aggressive subtype. Waiting could allow metastasis.”

She paused. “Would you like that in writing?”

“Yes. I’m documenting everything.”

Her gaze softened, understanding dawning. “Good,” she said. “Keep everything.”

I did.

Alone

By the time my family was posting photos from Paris — “Family time is the best time!” — I was halfway through chemo, bald, nauseated, and terrified.

They didn’t call once during those three weeks.

When they returned, Mom phoned casually.

“How are you? Sorry we couldn’t be there. The trip was amazing. You’ll see pictures.”

“I had two chemo sessions alone,” I said.

“Well, the nurses were there,” she replied. “That’s what they’re paid for.”

The Surgery

August fifteenth.

Six hours under anesthesia.

Double mastectomy.

When I woke up, I was bandaged, numb, and alone. No flowers, no family, no familiar faces — just the antiseptic hum of the recovery ward and a nurse adjusting my IV.

Dad visited two days later. Fifteen minutes.

“You look good,” he said. “You’re handling this fine. I still think you could’ve done the lumpectomy, but what’s done is done.”

“Dr. Martínez said it was necessary. The margins weren’t clean.”

“She’s covering herself legally,” he muttered. “Anyway, you’re through the worst. Radiation should be easy.”

Easy. As if lying under a machine five days a week for six weeks was a nap.

Thanksgiving Plans

By November, I’d returned to work part-time — exhausted, sore, but trying to reclaim something normal.

Mom called one evening.

“We’re hosting Thanksgiving. Big dinner at our house. Tyler’s bringing his girlfriend. We want you there, looking healthy and happy. No cancer talk. Everyone’s tired of hearing about it.”

“Everyone?”

“It’s been months, Chloe. Let’s focus on being grateful. Wear something that hides the scars — we don’t want to make people uncomfortable.”

I hung up without replying.

Two weeks later, the Riverside–Metropolitan merger went public.

The email announcement hit every staff inbox:

“We are pleased to announce that Dr. Helena Martínez, formerly Director of Oncology at Metropolitan Cancer Center, will assume the role of Chief of Oncology for the Riverside Health System, overseeing all oncology services and staff.”

I read it twice, then closed my laptop.

Thanksgiving was going to be interesting.

Thanksgiving

Twenty people crowded into my parents’ house that afternoon.

Dad at the head of the table, carving turkey, talking loudly about hospital politics. Tyler describing ER cases like campfire stories. Mom fussing over the gravy, ignoring the tension in the air.

“Chloe’s looking so much better,” Mom announced to the table. “She had some health issues earlier this year, but everything’s resolved now.”

Health issues.

“What kind?” my aunt asked.

“Just routine checkups,” Dad said quickly.

My uncle frowned. “Routine? You lost your hair.”

Tyler jumped in. “She had a minor cancer scare. Stage two, very early, very treatable. Did some treatment, now she’s fine.”

My cousin — a nurse — froze mid-bite. “Stage two what?”

“HER2-positive,” I said quietly.

Her fork clattered onto her plate. “That’s one of the most aggressive breast cancer subtypes. At your age, that’s serious.”

“It’s stage two,” Tyler said, dismissive as ever. “Not stage four. Big difference.”

“Stage two HER2-positive is high risk,” my cousin said sharply. “Who’s your oncologist?”

“Some doctor at Metropolitan,” Dad said. “We offered to get her into Riverside, but she wanted this community doctor.”

My cousin blinked. “Metropolitan? Isn’t that the facility that just merged with Riverside? The one whose chief of oncology is—wait—Dr. Helena Martínez?”

The room went silent.

My cousin looked around, eyes widening. “Oh my God. She’s your oncologist, isn’t she?”

I nodded. “Yes. Dr. Helena Martínez.”

Dad’s face drained of color. “The Dr. Martínez?”

“The one who’s now Chief of Oncology for all of Riverside,” my cousin confirmed. “She’s one of the top specialists in the region.”

Tyler’s girlfriend frowned. “If your family works at Riverside, and your oncologist is now their boss, why did they say she was just a community doctor?”

I looked at them, one by one.

“Because they never asked,” I said quietly. “They assumed she wasn’t qualified. They spent eight months telling me she was overtreating me for profit.”

Dad stood abruptly. “Chloe, can we talk privately?”

“No,” I said, voice steady. “We’ll talk here.”

Part Two

The room froze.

Every fork stopped midair. Every face turned toward my father — the man who’d built his career on judgment and authority — now speechless in front of his colleagues and extended family.

Mom’s knuckles tightened on her napkin. Tyler looked like he wanted to disappear. His girlfriend stared at her plate, unsure whether to speak or breathe.

“You knew about the merger?” Mom said finally, her voice trembling. “You knew and didn’t tell us?”

“I saw the announcement two weeks ago,” I said. “You didn’t ask.”

“You could have mentioned it,” Dad said sharply.

“Just like I could have mentioned chemo when you were touring the Louvre? Or radiation while you were wine-tasting in Florence?”

Tyler slammed his glass down. “Enough! Don’t make this public, Chloe. You’re embarrassing the family.”

“The family embarrassed itself,” I said. “For months, you told people my cancer was minor. You told me I was overreacting, that my oncologist was overbilling. You told me to wait for surgery because of your vacation.”

“You were emotional,” Dad said. “You didn’t understand how these things work.”

“I understand better than you think,” I said quietly. “Dr. Martínez does too. She’s seen all the documentation.”

The silence that followed was almost physical — a solid, heavy thing pressing down on every inch of that dining room.

Mom’s eyes widened. “What documentation?”

“The messages. The emails. The texts you sent me — telling me to delay treatment, calling chemo an overreaction, telling me to hide my scars so people wouldn’t feel uncomfortable. All of it.”

“You showed her?” Tyler’s voice cracked. “You showed Dr. Martínez?”

“Yes. She asked why I didn’t have family support during treatment. I showed her the truth.”

My cousin — the nurse — broke the silence. “Dr. Martínez is serious about that. She published a paper last year about young women’s cancer being dismissed by family and medical staff. She calls it familial minimization syndrome.”

Dad blinked. “She—what?”

“She’s known for it,” my cousin said. “And for holding healthcare workers accountable when they do it.”

You could feel the energy shift — the smug confidence evaporating from my father’s face as the weight of that statement landed.

“She’s now your boss’s boss,” I added. “Chief of Oncology for all of Riverside. She reviews administrative policies, oncology protocols… and departmental ethics.”

Tyler’s face went pale. “You didn’t.”

“I did nothing but survive,” I said.

Monday Morning

Two days after Thanksgiving, the reviews began.

The Riverside administration building buzzed with rumors — words like “ethics review,” “disciplinary oversight,” “conflict of interest.”

Dad’s title — Senior Operations Administrator — suddenly didn’t shield him from whispers in the hallway.

That morning, Dr. Helena Martínez sat at the head of a long mahogany conference table, a folder labeled “Preston, Charles — Administrative Review” resting in front of her.

She was poised, professional, the kind of quiet presence that radiated authority.

“Mr. Preston,” she began, “thank you for meeting with me.”

Dad sat stiffly, suit perfect, smile strained. “Of course, Dr. Martínez. I didn’t realize you and my daughter—”

“Yes,” she said evenly. “Your daughter is my patient. Her case was… memorable.”

He swallowed. “We didn’t realize—”

“You didn’t realize I was qualified,” she said, flipping open the folder. “Despite fifteen years of oncology experience, Johns Hopkins fellowship, and over forty peer-reviewed publications.”

Dad’s mouth opened, then closed.

“Let’s discuss the issue at hand,” she continued. “Not my résumé — your conduct.”

“My conduct?”

She slid a printed text message across the table.

‘Can you delay surgery until after our family trip? It’s not life-threatening.’

“That’s your message to your daughter, yes?”

He looked down. “Yes, but—”

“She was undergoing chemotherapy for HER2-positive invasive ductal carcinoma,” Martínez said sharply. “An aggressive cancer subtype. You, an experienced healthcare administrator, told her it was ‘borderline.’”

He hesitated. “I didn’t mean—”

“You dismissed evidence-based treatment as ‘overbilling.’ You told her to schedule life-saving surgery around vacation plans.”

“That was… a misunderstanding.”

She leaned forward. “You work in patient services. You are responsible for maintaining Riverside’s standard of care. Tell me, Mr. Preston, what does it say about this hospital when one of its senior administrators tells a cancer patient to ignore medical advice?”

Dad’s jaw tightened. “It says I made a personal mistake.”

“No,” she said coolly. “It says Riverside’s leadership may not understand the ethics of patient care.”

He went silent.

The Brother

Tyler’s review came next.

He walked into the conference room with false confidence — a swagger that cracked the moment he saw the HR director sitting beside Dr. Martínez.

“Mr. Preston,” Martínez began, “you’ve been quoted in staff discussions calling early-stage breast cancer ‘not serious’ and ‘over-treated.’ Do you deny that?”

He shifted. “That’s not how I meant it. I meant it’s manageable.”

“Do you understand the difference between manageable and dismissible?”

He blinked, caught off guard. “It’s just perspective.”

“No,” she said sharply. “It’s ignorance. Dangerous ignorance. According to multiple witnesses, you told ER staff that your sister’s treatment was unnecessary. You called HER2-positive cancer ‘overreaction.’ That pattern has consequences.”

“I didn’t think it mattered—”

“It matters to every patient who trusts you,” she said. “We reviewed your case notes. You’ve downplayed patient complaints about potential malignancies — recommending ‘watchful waiting’ in cases that required escalation. Your language mirrors exactly what you told your sister.”

Tyler’s composure cracked. “You can’t connect that—”

“I just did,” she said calmly. “You’re suspended pending a full review of your patient interactions. Your practice pattern shows a consistent minimization of early warning signs. That’s not medical judgment. That’s negligence.”

His face drained of color. “You’re ruining my career.”

“No, Mr. Preston,” she said, her voice like ice. “You did that yourself.”

The Mother

Mom’s review was shorter but no less brutal.

Her role in medical records meant she had access to my file — and had still referred to my diagnosis in public as “a minor health issue.”

“Mrs. Preston,” Martínez said, “you signed confidentiality policies when you joined Riverside, correct?”

“Yes.”

“And yet you minimized your daughter’s documented malignancy in front of extended family and coworkers.”

Mom’s eyes filled with tears. “I didn’t mean harm. I was trying to protect her privacy.”

“By denying her reality?” Martínez asked. “By referring to an aggressive cancer as a ‘routine checkup’? What message does that send to other families watching how a hospital professional treats her own child’s illness?”

Mom broke down crying. “I didn’t think—”

“That’s the problem,” Martínez said softly. “You didn’t think.”

Within two months, all three Pretons were removed from their positions.

Dad was placed on indefinite administrative leave.

Tyler’s suspension became termination after the internal audit confirmed multiple documented dismissals of early-stage cancers in ER cases.

Mom was demoted to clerical work with no access to patient files.

Riverside issued a quiet internal memo about “realigning values with ethical patient care.”

Everyone knew what it meant.

The Call

Three months later, my phone rang.

“Chloe,” Dad said. His voice was quiet, almost broken. “You ruined our lives.”

“I documented my treatment,” I said calmly. “Dr. Martínez made decisions based on your behavior, not mine.”

“We’re your family.”

“You went to Europe during my chemo,” I said. “You called my cancer ‘minor.’ You told people my doctor was overtreating me for profit. You made your choices. Now you’re living with them.”

He said nothing for a long time. Then: “We didn’t think it was that serious.”

“That’s exactly the problem,” I said, and hung up.

Six Months Later

At my six-month post-treatment checkup, Dr. Martínez smiled. “You’re cancer-free, Chloe. All clear.”

I exhaled for what felt like the first time in a year.

She closed my chart gently. “What happened to your family’s employment wasn’t revenge. It was accountability.”

“I know,” I said quietly.

“People in healthcare forget — patient safety isn’t just protocols. It’s culture. If your family dismissed you, how many patients have they dismissed? That’s what concerned me.”

She looked up, eyes steady. “You did the right thing. You didn’t destroy their careers — you exposed their judgment.”

Epilogue

I’m twenty-nine now.

Cancer-free.

Working full-time again, rebuilding my life without the illusion of family support.

Sometimes people ask if I regret what happened — if I wish I hadn’t told Dr. Martínez the truth.

But the truth doesn’t ruin people. It reveals them.

My family spent eight months telling me science was negotiable, that my survival could wait until after their vacation. They underestimated me — and the woman they dismissed as “a community doctor.”

Now, they understand what real credentials look like.

Dr. Helena Martínez didn’t just save my life. She taught me that evidence doesn’t need permission — and justice doesn’t need to raise its voice.

Because in the end, the pathology reports don’t lie.

The records don’t exaggerate.

And peer-reviewed oncology research doesn’t care about vacation plans.

THE END

News

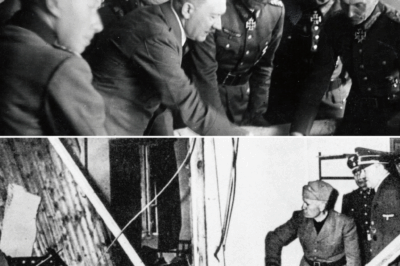

July 20, 1944 – German Officers Realized The War Was Lost, So They Tried To Kill Hitler

PART I The thing about history—real, bloody, bone-shaking history—is that Americans often like to pretend it happens somewhere else. Across…

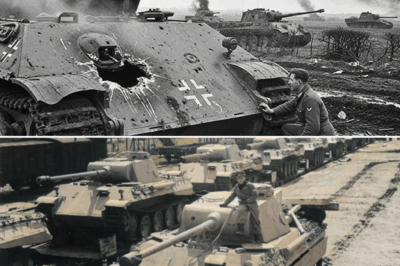

The Secret Shell That Taught German Panthers To Fear The American Sherman 76mm Gun

Part I The fog lay thick over the French farmland like a wool blanket soaked in cold dew. September 19th,…

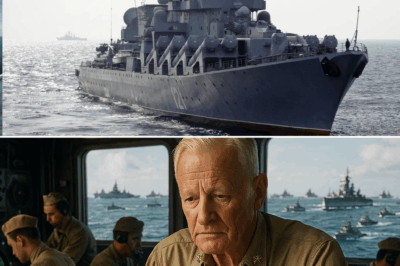

Admiral Nimitz Had 72 Hours to Move 200 Ships 3,000 Miles – Without the Japanese Knowing

Part I June 3rd, 1944 Pearl Harbor 0600 hours The sun had barely risen, its light sliding across the battered…

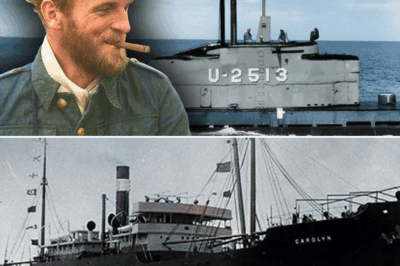

German U-Boat Ace Tests Type XXI for 8 Hours – Then Realizes Why America Had Already Won

PART 1 May 12th, 1945. 0615 hours. Wilhelmshaven Naval Base, Northern Germany. Coordinates: 53° 31’ N, 8° 8’ E. Captain…

IT WAS -10°C ON CHRISTMAS EVE. MY DAD LOCKED ME OUT IN THE SNOW FOR “TALKING BACK TO HIM AT DINNER”…

Part I People think trauma arrives like a lightning strike—loud, bright, unforgettable. But mine arrived quietly. In the soft clatter…

My Date’s Rich Parents Humiliated Us For Being ‘Poor Commoners’ — They Begged For Mercy When…

Part I I should’ve known from the moment Brian’s mother opened her mouth that the evening was going to crash…

End of content

No more pages to load