Part I:

Savannah always smelled like memory to me—magnolia and salt, fried batter and something warm I could never name. It was the scent of childhood summers on our wide porch, of my grandmother’s hands dusted with flour, of the sleepy hum that rolled off the Spanish moss when the heat settled into evening. That night, the air held all of it—plus a crackle that wasn’t quite thunder. A storm of a different sort was gathering right over our family’s roof.

I stepped out of the rideshare with a leatherbound journal tucked in a gift box under my arm, my suitcase wheel dragging across the uneven bricks. The house rose up like a page from a storybook—white columns, dark shutters, a porch deep enough for three generations to fit a Sunday meal. String lights zigzagged across the verandah, casting warm halos on laughing faces. Jazz floated out through the open front doors, and even the crickets seemed to keep time with the bass.

The party wasn’t canceled.

Lauren’s call from three days ago rang in my ears. Dad’s not feeling well. No need to come home. The way she’d spit the words out—too fast, too casual—hung in my mind like a badly tied bow. My sister had always been the golden child, excusing herself from the table of accountability with the breezy charm of a girl who never had to clean up her own mess. But this—lying about Dad’s birthday—this was a different level of wrong.

Inside, our house turned into a postcard. Neighbors and old family friends swirled around the dining room where platters of pecan tarts and fried green tomatoes reflected the chandelier’s glow. Dad was posted near the table, looking trim and restless in his navy blazer, cheeks a little ruddier than usual. His laugh cut through the room with that contractor’s gravel, a man who spent half his life shouting over circular saws, now winding down into the gentler years.

“Baby girl!” he boomed when he caught sight of me. He folded me into a hug that smelled like aftershave and bourbon. “You didn’t have to come all the way from Atlanta.”

“Try keeping me away,” I said, and swallowed against a hard knot. “Happy birthday.”

The journal slid into his hands. I’d had his initials, J.H., stamped in gold along the cover. He touched it like it might bruise, then grinned at me with the familiar, puckered mischief. “Always knew you were the thoughtful one.”

I smiled back. The words warmed me, but not enough to melt the dread creeping along my spine.

Lauren drifted in from the living room, a glass of something pale and expensive flashing in her hand. She looked like a magazine layout—soft blonde waves, silk dress in a champagne shade that cost a mortgage payment, diamond at her throat bright enough to blind. She paused when she saw me, just for half a heartbeat—half a heartbeat where her eyes widened and a seed of panic crossed her face. Then she pasted on a smile.

“Emma,” she chirped, like a flight attendant asked to announce turbulence. “You made it.”

“Imagine that,” I said.

She kissed my cheek without touching me, perfume and distant glitter. There’d been a time I would’ve told her everything—about my design clients, about my recipes I was sketching in the margins of client briefs, about the vintage bakery I dreamed up in my Savannah daydreams. Somewhere between our mother teaching us how to set a table and Instagram learning to devour people whole, we’d fallen out of orbit. Now, even our polite words felt like furniture, rearranged to fake comfort.

Aunt Clara materialized beside the dessert table. It wasn’t that she was small; she was simply one of those women Georgia breeds who can be anywhere, a switchblade in slippers. Her gray bob caught highlights from the chandelier, and her reading glasses dangled from a chain like a charm bracelet. She handed me a glass of sweet tea and angled her body so her voice would fall just for me.

“Funny thing,” she said, dry as a heatwave. “I heard tell this party was canceled.”

“Funny,” I said, my mouth suddenly cotton. “I heard the same.”

Clara’s eyes scanned the room. “Lauren was at the mall last week throwing money like rice at a wedding. New dress every day. Bahamas last month. You seen those pictures? She posted like she was born at the Atlantis.”

I had seen them. Tropical oceans the color of toothpaste. Laughter, swimsuits, a neon sign that said Good vibes only hovering over a stranger’s rented cabana. I’d scrolled past them, an ache blooming under my ribs. Not envy—okay, a little envy—but something more like the dislocation of watching someone else wear your life like a costume.

“I figured her brand partners were covering it,” I said. Lauren’s deals—teeth whiteners, gummy vitamins, a few local boutiques—didn’t amount to that much, but denial was easier than suspicion.

Clara made a little noise like she’d found a chicken bone in her soup. “I figured my left foot.”

The jazz shifted to something brighter. Guests flowed toward the dining room as Mom emerged from the kitchen in a fitted navy dress, hair done, smile pinned a little too tight. Her hands, always soft, always manicured, fussed with a tray of biscuits. She glanced at me, then away, some private calculation flickering across her face.

I told myself I was imagining it. I told myself I was being dramatic. I also told myself not to check my bank account on my phone in the bathroom again. When I’d seen that transfer notice earlier in the week—a vague reference number I couldn’t connect to anything—I’d blamed a glitch. It was easier that way.

Dad gathered us around the table, the printed place cards one of my little touches. I recognized my own handwriting and smiled, then felt foolish for claiming credit for paper when bigger things were unraveling. We clanged our glasses, called out old stories—Dad’s first tool belt, Mom’s recipe for perfection, the time Lauren broke her wrist falling off the dock during a sunset photo shoot because she’d insisted on wedges.

Dad opened gifts—books from his golf buddies, a handcrafted birdhouse from the neighbor kid, my journal. He lingered on mine, thumb skimming the leather, eyes going soft with a look I knew better than my own face: pride. The evening softened with it, the way a good bourbon does. The tightness in my chest loosened, just a little.

Someone rolled in the pecan pie. The room narrowed its attention like a camera lens. Dad lifted the knife, then paused. His eyes cut to me. He lowered the knife.

“Emma,” he said. Not loud, but the tone carried, a thread of steel woven tight. “The two hundred thousand I sent you—what did you do with it?”

The room stilled on a dime. The bassline in the next room faltered; somebody missed a note. My hand went numb around my glass. Two hundred thousand. I stared at him. “What?”

“The two hundred,” he said, slower, every word laid down like a plank. “To you and Lauren both. Not the bakery money. The other.”

I could hear my heartbeat inside my ears. All the tidy compartments in my brain opened at once. Eight hundred thousand wired months ago—that I knew, accounted for down to the penny in a savings account labeled oven. It was the scaffolding of my dream, the future he’d pressed into my palm like an heirloom. Two hundred thousand… I tried to pull up the vague transfer notification. I tried to breathe.

“Dad,” I said, and my voice broke around the second letter. “I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

A laugh—too bright, too tight—sprang from Lauren’s throat. “She probably forgot, Dad. You know how busy she is with clients.” She touched the diamond at her throat. Her fingers trembled. Her knuckles had gone white.

Dad didn’t take his eyes off me. “Emma.”

I shook my head. “I never got it.”

My mother’s glass clicked against the table. She stared at the pie, as if cutting it would neatly divide us back into the before. The room shifted—guests trading looks, a low murmur rolling like surf. Aunt Clara’s gaze sharpened enough to cut fabric.

Dad inhaled. We’d joke that you could hear the contractor in that breath, the way he’d fill his lungs before calling a job wrong and tearing out drywall with his bare hands. “I set aside two hundred thousand each for my girls,” he said, measured, solemn, trained on fairness. “Emma, I moved yours into a joint account, you and me. Lauren’s the same with her. For your futures. You telling me you never saw a penny?”

My jaw went slack. Joint account. I felt stupid for not knowing, then furious for being made to feel that way. “No,” I said. “I didn’t. I swear to God, Daddy.”

The room heard the Daddy and breathed, a few pitying glances flicking toward me. I wasn’t reaching for pity. I was reaching for the past—when things were clear and straight.

Dad turned, slow, to my sister. “Lauren. What did you do with yours?”

Lauren’s mouth moved without words, like a fish caught where the river narrows. She glanced at Mom. Mom’s chin lifted a fraction of an inch. That was the tell. Not a nod, not a plea for honesty. A calculation. A number crunched in a secret column.

“I invested,” Lauren said finally, voice breathy. “You know, smart stuff.”

“Smart stuff,” Dad repeated, a chunk of granite.

Aunt Clara folded her arms. “Smart like a Bahamas suite, five pairs of Louboutins, and a new diamond?”

Lauren flushed. “Those were gifts.”

“From who?” Clara asked. “Santa with a sugar daddy?”

Laughter stuttered in a few throats, the uncomfortable kind that slips when people are terrified. Mom set a hand on Lauren’s arm. “Let’s not do this here,” she said, and in her voice I heard the exact tone she used to patch a pinhole leak with tape.

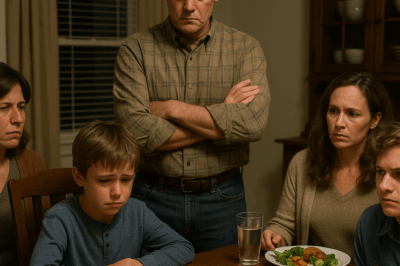

Dad’s palm came down flat on the table, not a slam but near enough. Silverware rattled. The jazz stopped altogether. “We will do this here,” he said, low, deadly calm. “Because apparently my home is the one place truth can’t get in without a key.”

He looked at me again. “You’re certain.”

“Yes.” I swallowed. I couldn’t feel my hands. “If you moved it, I didn’t see it. I didn’t touch it.”

He nodded once. Something in his face fell into place—the way a builder’s face does when he realizes a wall has been framed out of plumb and the entire structure leans. He looked older, by years. Then he turned back to Lauren. “Where’s your sister’s money?”

The room lurched. “Dad—” Lauren began.

“Where,” he repeated.

“John,” my mother snapped, using his first name the way she only did when she felt judged. “Enough.”

“Enough is right,” he said, still looking at Lauren. “Enough lying. Enough borrowed time. Where. Is. Emma’s.”

The diamond at Lauren’s throat winked. Her lower lip trembled. “I thought—” She shut her eyes, drew a breath, tried again, eyes bright with gloss. “I thought it was mine. I thought—Dad, I swear I thought you… meant for me to have it, for my content, my brand. I was going to put some back once I—”

The air dropped out of the room like a trapdoor. My voice came up from somewhere outside my body. “You took my money?”

Her gaze darted to mine, then away. A child caught with sugar on her face—only the sugar was a number with five zeros.

Dad’s voice shifted into that tone that made grown men tear up blueprints. “You stole from your sister and called it a thought.”

“I didn’t steal,” she said, too fast. “Mom said—”

Silence snapped like a whip. Mom’s fingers tightened on Lauren’s arm. A fresh wave of nausea broke across me. “Mom?”

She didn’t look at me. “We can fix it,” Mom said to Dad, eyes hard with that brittle optimism that eats families alive. “It was a mistake. We can move numbers back. No need to make a scene.”

“Make a scene?” Dad asked. “The scene made itself and invited two hundred thousand dollars to the party.”

“I’ll pay it back,” Lauren said, pleading now, voice pitching high. “I’m getting a brand deal with—”

“With who?” Clara cut in. “A boutique candle store in Macon?”

“Clara,” Mom hissed, a last stand.

Dad straightened. I watched that motion, the lengthening spine, the square set of shoulders. He’d pulled me up like that when I was ten and fell off the porch step and busted my lip: calm, decisive. He took out his phone and scrolled. My stomach realized what he meant to do before my mind caught up.

“Dad,” I said, panic pushing the word out like a last card on a busted hand. “Wait.”

He didn’t. “Yes, ma’am,” he said when the dispatcher picked up. “I need officers at my address. We’ve had a theft. Two hundred thousand dollars.”

The party broke then, in slow motion. A neighbor pressed fingers to her chest. Someone guided the older guests to the porch. A few people slipped away, breathless with the delicious shame of leaving early. The chandelier hummed like a hornet nest.

Lauren stared at Dad, eyes huge, mascara beginning to smudge like bruises. “You’re calling the police on your own daughter?”

“I’m protecting my other one,” he said.

Mom sucked in a breath, a small wounded sound. “John.”

He pocketed the phone. “Emma,” he said, gentler. “I’m sorry you’re hearing it like this. I’ve been fool enough. I’ll fix what I can.”

I nodded, and the nod cost me more than I knew I had. I looked at Lauren. All at once, I saw the two of us at seven and nine, sharing a sweating popsicle on the porch steps. I saw us at fourteen and sixteen, whispering into the dark about what we’d do with the lives our parents built us. I saw the places where we’d diverged: she’d learned to be loved by an audience; I’d learned to be useful.

“You could have asked me,” I said, voice raw. “You could have asked.”

Her face crumpled. “I thought I could put it back before anyone noticed,” she whispered. “I swear to God I—”

“God heard you the first time,” Clara said, grim.

The patrol car lights washed the living room in blue. Officers stepped in with the careful kindness small towns teach: quiet voices, patient questions. Dad answered. Lauren stumbled through versions of a story until the words congealed into one truth: she’d taken what wasn’t hers, with Mom’s tacit nod and a fantasy of no consequences. The officers kept their faces steady. They’d seen worse. Family crime is its own weather.

I sat on the bottom step of the staircase and wrapped my hands around the post like the house might steady me back. The jazz was off. The party had become a mural of awkward–men in sport coats avoiding eye contact, women in pearls whispering behind napkins, glass sweat rings on mahogany. Dad signed something. Mom’s face shuttered. Lauren cried, then stopped, then breathed, a girl rehearsing an apology that would not work.

Aunt Clara sat beside me without asking. She didn’t touch me. She didn’t need to. “I’ve got receipts,” she murmured, dropping her voice to the pocket of space just between us. “Literally. Boutique bills, plane tickets, jewelry. If we need to prove the trail, we can.”

I laughed. It came out wrong, a bark and a break. “It’s not about proving it,” I said. “It’s about hearing it and having it not rewire your whole spine.”

Clara tilted her head. “You been carrying a dream a long time,” she said. “Good dreams don’t break easy. That’s how you know they’re worth anything.”

“I had eight hundred for the bakery,” I said, knowing I was saying the number to remind myself it still existed, that I hadn’t landed in a world where numbers evaporated. “I still have it. This wasn’t about survival. It was about…respect.”

“It’s always about respect,” Clara said. “Even when folks pretend it’s about love.”

The officers walked my sister out without cuffs. Savannah isn’t that kind of town, not when the accused is the homeowner’s daughter and the accusers are the same. Mom followed, dignity wrapped around her like a thin coat on a cold night. Dad stood in the doorway, shoulders square, jaw working. He wasn’t crying, exactly. He looked like a man trying not to let his face collapse.

When the door clicked shut, the house exhaled. The guests turned to air. The dessert table stood like a casualty of a happier war—pecan pie untouched, cooling under lights. I reached over and cut a small slice for Dad, small and strange. I put it on a plate and handed it to him. He gave me a look I’d seen the day I left for college—the one that said I’m proud and I’m scared and We have things we can’t say.

“Make a wish,” I said, because it was the one sentence that seemed to fit.

He blew out the candles. When he raised his head, the man in front of me was older than he’d been an hour earlier. But he was still my father—the one who’d given me eight hundred thousand for an oven and a dozen Saturday mornings to practice cinnamon rolls on the neighbors.

“I’m going to fix what I can,” he said again, steady.

“I know,” I said.

Later, after the officers were done and the neighbors had scrubbed the last of their pity from our floors, after Mom called Uncle Dennis to pick her up rather than ride in a squad car, after Lauren’s diamond necklace sat crooked on an evidence photo, I wandered into Dad’s study. The room smelled like leather and old paper, a scent that had wrapped around my childhood like a second blanket. I ran my fingers along the spines of books that had taught him to build: old carpentry manuals, home plans scribbled with notes in his tidy contractor’s hand, a framed blueprint of the house he’d restored for us.

My phone buzzed. A text from a client nudging me about a logo revision. A normal thing, a rope tossed into what felt like a new sea. I swallowed and typed back, You got it by morning. I didn’t know if that was a lie, or if the muscle of my life would still work even with this new weight.

Dad tapped on the door frame. His face was softer in the study’s lamplight. “You all right?”

“No,” I said honestly. “But I will be.”

He nodded. “Me, too.”

We sat in the hush. He took my hand and squeezed it like a builder tests a joist. “Your grandmother used to say truth is a mean but faithful friend,” he said. “Hurts like hell. Keeps you honest. Keeps your house from falling in.”

I thought of my bakery, this dream that looked like pressed tin ceilings and antique cake stands, like Sunday mornings that smelled like sugar and butter and something holy that didn’t need a church. I thought of the $800,000 sitting neatly in my account, untouched, a promise. I thought of another number—$200,000—that had turned into dresses and sunburns, into a sister with a pale face and a mother who couldn’t look me in the eye.

Clara’s voice carried from the hallway. “I’ll be back in the morning. I’m bringing biscuits and a plan.”

It was ridiculous and perfect. “Okay,” I called.

Dad looked at me. “We’ll get through this, Em.”

I pulled in a breath—deep, steady, briny like the air off the river. “We will,” I said. “But we won’t pretend it didn’t happen.”

He squeezed again. “No, ma’am.”

That night, I lay awake in my old bedroom beneath a ceiling fan that sounded like the slow tick of a metronome. The house settled around me. The squares of moonlight on the floor shrugged and shifted as the trees moved outside, careful as old men crossing the street. Somewhere downstairs, the refrigerator motor clicked on. I thought of Lauren in a gray room under a fluorescent bulb. I thought of Mom on a bench, face in her hands.

I waited for anger to arrive like a storm. It didn’t—not yet. Instead, a sad, steady kind of clarity slid into the room and sat with me until morning.

When dawn came, it did what it always does in Savannah: it peeled back the night like paper, spilling gold over the marsh and tipping the live oaks in light. I got up. I made coffee in the kitchen that had raised me on cornbread and sugar cookies. I stood at the sink with my hands wrapped around a mug and let the heat climb up my arms. Dad padded in wearing his old Bulldogs T-shirt, hair sticking up like a man who had fought sleep to a draw.

“You’ll open that bakery,” he said into the quiet. Not a question. A faith.

“I will,” I said.

He nodded. “Then we start today.”

We did. Not the way either of us would have chosen, but the way life insists—one small, true thing at a time.

Part II:

Morning in Savannah slipped into the house like an apology. The light softened the scuffs in the hardwood and made even the stack of abandoned party plates look quaint instead of tragic. Aunt Clara’s knock arrived ten minutes after eight—two raps the family learned to recognize as both courtesy and warning. When I opened the door, she stood with a tote bag looped around one wrist and a Tupperware carrier balanced on the other, like a general with rations.

“Biscuits,” she announced, striding past me. “And butter I whipped with honey and a little salt because I don’t believe in healing on an empty stomach.”

Dad was already at the dining table, reading glasses propped low on his nose, a legal pad in front of him with a column on the left labeled “Facts” and one on the right labeled “Feelings.” Lines were running down the page like fence posts—one thing he could still control: straight edges.

“Clara,” he said, half-greeting, half-sigh.

She set the biscuits down, kissed the top of his head, and plucked his pencil. “Feelings later. We start with the ledger.” She turned to me. “You eat, you talk. You can cry, but if you do, we’ll put those tears to work cleaning the guilt out of these dishes.”

I smiled despite everything. “Yes, ma’am.”

We ate in a clatter of plates and the warm, forgiving hush that follows good bread. Between bites, Clara opened her tote and spread out receipts, printouts, notes with dates circled in red. “I came over late last night, grabbed what I could from their trash,” she said, practical as a weather report. “Influencers post. Banks print. Paper trails don’t lie.”

She pushed a handful of store receipts toward Dad. “Twenty-three hundred dollars at River Street Clothiers. Six thousand at Solange Jewelers. First class tickets to Nassau for two—she took that man who calls himself a media manager but couldn’t manage a chia pet.”

Dad’s mouth tightened. He didn’t ask how Clara knew the man’s name. In Savannah, if you don’t know a name, you can always find someone who knows someone’s cousin who does.

I pulled my laptop close, fingers steadying over the keys like a pianist warming to a difficult piece. I opened my account and scrolled through the months, past the big, neat eight-hundred-thousand-dollar wire that had made me cry from gratitude on a Tuesday in spring. There it was again—the transfer with no clear sender, the one that had clanged in my head in the days before the party. Reference numbers. A date. An amount: $200,000. Outbound.

“Dad,” I said softly, tilting the screen. “Did you…?”

He leaned in. The skin under his eyes looked thin as paper. “No,” he said. “I didn’t touch your account.”

“But if it left…” I swallowed. “Either I sent it and blacked out six months of my life, or someone else moved it. How would anyone even—”

“Joint account,” he said, the words flat and unsentimental. “I gave the banker your information when we set up the trust transfers. Your mother had mine. We always shared. I didn’t think—”

Clara cut in. “She knew the rails. She walked the path she knew you’d left. Lotta theft in this world isn’t picking locks. It’s walking through doors folks already opened.”

The coffee in my stomach turned to pennies. “So she used your authority to move my money out of my account,” I said. Saying it made the air thinner, but it also put iron in my spine. “And Lauren burned through it like it was a fire sale.”

Dad’s pencil hovered. He drew a line under “Facts.” He wrote in his careful, builder’s block print: MONEY MOVED FROM EMMA TO JOINT TO LAUREN. Under “Feelings,” he simply put: BETRAYED.

Clara peered over the receipts again. “What we do now: document, report, and insist on restitution. The law doesn’t care about delicate family sensibilities half as much as your mother always thought it did. Georgia statutes are plain on felony theft by conversion. And—forgive me, John—if you don’t hold the line, you’ll be financing Lauren’s next apology tour by spring.”

Dad nodded. “Already called last night,” he said. “They’re processing booking this morning. We’ll go give our statements.”

“Then we go today,” Clara said, clapping once as if to set a metronome. She pointed her chin at me. “You put on something that says respectable and unstoppable. Not pretty, not sweet. Bank manager on a mission.”

I snorted. “I don’t own unstoppable. I have ‘Artist Who Pays Quarterly Taxes’ and ‘Woman Who Can Fix Your Kerning.’”

Clara smiled in that sideways way that meant she’d already picked the outfit in her head. “We’ll borrow unstoppable from my closet.”

We were out the door by nine-thirty: Dad in a pressed oxford and work boots, a combination that told any man with a badge he meant his promises; Clara in slacks and a blouse that said retired teacher but will cut you; me in a black dress that made me look older than thirty-two and hungersome in a way I didn’t dislike. The ride to the precinct slid by under live oaks, the world green and dappled and ordinary, which felt obscene.

The police station air hit us with disinfectant and old paper. A receptionist with a neat bun and a hard candy tucked in her cheek led us to a small room with a table scarred by a thousand cheap ballpoints. The officer from the night before—Ramirez, his name tag said—entered with a folder and a tone I recognized from men who had learned to be gentle without promising what they couldn’t deliver.

“Mr. Hayes,” he said. “Ms. Hayes. Ms. Moore.” He nodded to Clara, having apparently learned in twelve hours what took me a lifetime: do not underestimate Aunt Clara.

He laid out the process, and we gave our statements. He asked questions with the kind of consistency that makes a person feel both seen and pinned. Yes, the amount was two hundred thousand. Yes, the funds had been designated by Dad for us individually. Yes, I had not spent that money, nor authorized anyone to move it. No, we did not wish to retract last night’s complaint.

When it was Dad’s turn to summarize, he cleared his throat and spoke like he was reading a contract out loud on a job site. “I’m a fool,” he said finally. “But I’m not willing to be one anymore.”

Ramirez didn’t write that line down, but he looked like he heard it.

They let us see Lauren through glass, a rectangle of observation that made my lungs feel like they’d forgotten their job. She sat at a metal table, chin in her hands, mascara smudged into moon tips under her eyes. She looked small. The diamond was gone. Without the sheen of her curated light—filters, angles, the moody edits that turned even a coffee cup into art—she looked like my little sister again. The one who snuck into my bed when thunderstorms wagged their teeth over the marsh.

I thought of opening the door and sitting across from her, the way I have in the past when lesser storms hit—bad breakups, the loss of a brand deal to a girl with fuller lips and less patience. Then I remembered the bank ledger and the lie on the phone and the way she barely met my eyes at the party. I stayed where I was.

“Can we press charges against our own people without losing our souls?” I asked no one in particular.

Clara’s hand found my elbow. “A soul isn’t a china figurine,” she said. “It doesn’t break if you set it down in the truth.”

An officer popped his head into the hall to speak to Ramirez. He returned with new information: Mom had been questioned in a separate room. She’d admitted to giving Lauren access to the joint account, her rationale thin and unadorned: she believed—somehow—that Lauren’s needs were urgent and temporary and that Emma “had plenty already.” She’d thought she could “fix it before anyone noticed.”

I stared at the floor tile, the mottled speckle that looked like cut stone. I counted twelve specks in one square, then lost count. Plenty already. The words slotted into my ribs like a splinter. I felt Dad go very, very still beside me.

“We’ll proceed with charges,” Ramirez said gently. “Given the amount, the DA will likely pursue felony theft by conversion and conspiracy to commit the same. Probation and restitution are common in first offenses, but I can’t promise outcomes. I can promise it will be documented. And that you’ll be kept informed.”

“Thank you,” Dad said, voice even. “That’s enough for now.”

On the way out, Mom and I crossed paths in the hallway without meaning to. She stood by the water fountain staring into the metal grille like it might return her to a different day. When she saw me, she flinched and caught herself, smoothing her face into a mother’s benign line.

“Emma,” she said. “You look pale. Are you eating?”

From somewhere, heat rose into my throat. Maybe it was the question. Maybe it was the absurdity of decorum in a building where strangers interrogated our grief. “Mom,” I said, steadier than I felt. “You signed my name on a robbery.”

Her chin lifted. “Don’t be dramatic.”

“Dramatic is confetti,” I said. “This is arithmetic.”

She went rigid. “I made a mistake.”

“You made a choice,” I said. “And then you made a lie to hide it.”

Her mouth opened, closed. “I thought we were family.”

“So did I,” I said.

Clara slid in like a second spine. “We’ll be in touch about the restitution plan,” she told my mother like she was settling a PTA disagreement, not a felony. “We’ll prefer cashier’s checks.”

Mom’s eyes filled, but the tears didn’t fall. She’d learned long ago to keep them as a resource. She reached for my hand. I stepped back. Not cruelly. Simply accurately.

We left. Outside, the sun made the asphalt shimmer. The cicadas were throbbing in the trees like a machine idling. Dad’s truck smelled like sawdust and work and the dog that died three summers ago. None of those things solved anything, but they were solid.

We drove not home but to the bank. If statements were the first brick, accounts were the mortar. Inside Chatham Federal, the air-conditioning was set to “permafrost,” and the bouquets were silk. The manager—Mr. Goodwin, a man who’d worn the same parted hair since the Clinton years—met us with corporate concern.

“We’re terribly sorry for the distress, Mr. Hayes,” he said after Dad explained everything again. “Let’s review the transfer history together.”

He clicked, frowned, clicked again. “Well,” he said, adjusting his tie. “I do see a transfer initiated under account authority from the joint account Johnathan Hayes/Emma Hayes to the account Johnathan Hayes/Lauren Hayes, dated six weeks ago. Then a series of withdrawals that… well, that’s a lot of shopping, Ms. Hayes.”

“It’s Emma,” I said, my voice choosing calm because rage was too easy. “And yes.”

He cleared his throat. “We will flag that joint account for no transfers without both signatures moving forward. And we can add an alert any time a transaction over, say, five hundred dollars is initiated.”

“Make it two hundred,” Clara said. “We’re not letting a Netflix renewal slip by.”

Goodwin typed and smiled like he appreciated a woman who planned for other people’s carelessness. He handed us printouts and a pen to sign the new restrictions. He offered coffee, which we declined. He offered condolences, which he delivered like a bank brochure. He asked, with a banker’s careful cadence, if we needed anything else.

“Yes,” Dad said. “We need a little mercy and a lot of memory. But I don’t suppose you’ve got forms for those.”

Goodwin’s smile faltered. “Not in my drawer, sir.”

Back at the house, the post-party wreckage still sat like a stalled parade. We cleaned in silence for a while—Dad breaking down boxes, me washing the china I’d insisted we use instead of paper, Clara throwing away napkins with the vigor of a woman who believed virtue could be built from small tasks. The repetition steadied me: rinse, stack, dry; breathe, count, fold. It was work you could complete. Grief is not.

After lunch—leftover shrimp and grits that tasted like a braver night—we sat in Dad’s study and opened a new set of ledgers. Not the hurt ledger. The future one. It felt defiant, and necessary, to talk about the bakery with a police file cooling on the table.

“Where are we?” Dad asked. “Oven, rent, buildout.”

I pulled up the spreadsheet I’d nurtured for a year, a patchwork of dreams and vendor quotes and notes from coffee with other bakers who’d let me peek behind their counters. “The oven is the heart,” I said, finding my old rhythm. “Italian deck oven I’ve been eyeing runs around eighty grand with installation. Rent—if we can get the corner spot on Whitaker, we’re looking at $4,500 a month. Buildout maybe one-fifty if we keep the exposed brick and do most of the shelving ourselves.” I looked at Dad. “If you’re up to it.”

He straightened like I’d offered him life. “I got hands,” he said. “And I got friends who owe me favors. We can shave that.”

Clara leaned back, eyes glinting. “I can wrangle city permits like they’re unruly students. And my bridge club knows every inspector’s ex-wife.”

I laughed. For the first time since the night before, it felt like it belonged to me.

“Staff?” Dad pressed.

“Two part-timers to start, one early-morning baker, one barista who knows how to smile without giving away their soul. Me on the mixer at four a.m., me on the register at noon,” I said. “We keep the menu tight for the first three months—pecan pie, red velvet cupcakes, savory biscuits, one rotating seasonal cake. Coffee with beans from that roaster in Charleston. Vintage plates from estate sales. My grandma’s recipes where they work, my tweaks where they don’t.”

“Name?” Clara asked, though she knew.

“Emma’s Vintage Oven,” I said softly, the syllables fitting like a ring. “Black-and-white tile floor. Brass fixtures. A counter with the kind of glass cases that make even a cookie look like an artifact.”

Dad’s eyes went soft. “It’s a good name.”

“It’s a good dream,” Clara corrected. “We’ll turn it into a good business.”

We mapped a timeline like we were building a bridge: contractor bids next week, landlord meeting Wednesday, permit paperwork by Friday, equipment quotes by the end of the month. I penciled in mock opening day in six months, then crossed it out and wrote nine. Ambition is a fine engine until it runs too hot.

Around three, my phone buzzed. A number I didn’t recognize. I let it ring into voicemail, then listened. “Ms. Hayes,” a woman’s voice said—brisk, kind. “This is Assistant District Attorney Margaret Sloan. I’m assigned to your case. I’d like to schedule a meeting to discuss charges and potential plea arrangements. Please call me back.”

I hit call before fear could talk me out of it. We set a meeting for the next morning. She told me what to bring—bank statements, the printouts from Chatham Federal, any written communication. “I know this is difficult,” she said. “We’ll walk you through.”

I hung up and stared at the ceiling fan again, daytime now, its blades patient and sure. “We’re really doing this,” I said.

“Yes,” Dad said. “We are.”

That night, I slept in a way that felt like surrender rather than escape. Dreams came shallow and kind—a kitchen that smelled like sugar and coffee, a bell over the door, a father sitting at a corner table reading the paper. In the dream, my mother came in and bought a slice of pie. She said she was proud of me and meant it. In the morning, I woke up with the taste of butter and grief on my tongue.

The ADA’s office the next day was all glass and muted tones, the color palette of seriousness. Margaret Sloan was a woman in her forties with an undercut that made me like her instantly and a pen she twirled as if it were a conductor’s baton. She laid out the likely path—arraignment, plea negotiation, restitution schedules, probation terms. She spoke in verbs, not platitudes. When she asked if I wanted to be present for arraignment, I said yes. I wanted facts, not gossip. I wanted to look this truth in the face in case it thought it could hide.

“Restitution will not restore trust,” she said, not unkindly. “But it will restore funds. That matters.”

“I know,” I said. “The trust is our work. The funds are the state’s.”

She paused, then nodded. “That’s a healthy division of labor.”

On the courthouse steps, the humidity gathered under my dress like a living thing. Reporters weren’t there—thank God. Savannah is petty sometimes, but it’s also private. Inside, the courtroom smelled like polish and history. Lauren stood at the defense table next to a public defender who looked like he belonged at a coffee shop with a dog. My mother sat behind them, lips pressed white, a scarf wrapped like armor around her shoulders despite the heat.

Lauren looked back once, halfway. Our eyes met. A thousand memories rushed the barrier—she braiding my hair before the eighth-grade dance, me hiding her in my room when she’d failed her driver’s test. The tide receded just as quick. She looked away.

The judge called the case. The charges were read. The words “felony” and “by conversion” clanged in the high room and echoed in my bones. Lauren’s voice, when she answered, was small. “Guilty, Your Honor,” she whispered, eyes down. Mom’s hands twisted in her lap.

The plea deal—negotiated by Sloan with a precision that made me grateful—set five years probation, two hundred thousand in restitution with a repayment schedule that would stretch like a long, ugly road, fines totaling five thousand, mandatory financial counseling. The judge asked if we were satisfied. I stood and said, “Yes, Your Honor,” because yes is a small word that sometimes means this is the least terrible option.

Outside, reporters had appeared after all—two local outlets and a freelance blog that thrives on scandal dressed as concern. A microphone angled toward me. “Ms. Hayes, do you have anything to say to your sister?”

I could feel Sloan’s caution like a hand on my shoulder. “Nothing you would understand in a sound bite,” I said. “We’re a family. We’re also citizens. Both those things are true.”

It wasn’t poetry, but it shut the questions down.

Days became planks we laid under our feet. I filed permits. Dad drew mockups on graph paper, hands moving with the joyful concentration of a man who’d been given back a language. Clara wrote lists—estate sales to hit, signage men to call, bakers to interview. I developed recipes with ruthless love: three pecan pie iterations until the syrup clung right, a red velvet that tasted like the word Sunday, a biscuit that folded in cheddar and jalapeño like a rumor. Some nights, I cried into dishwater. Some mornings, I woke humming.

The house learned the new rhythm—no more party, no more whispers. Instead: phone calls to vendors, contractor boots in the hall, recipes sketched in the margins of legal documents. Mom didn’t call. Lauren couldn’t. It was the kind of silence that is both wound and salve. We let it sit, because some words have to be paid for over time like debt.

On a Saturday in late July, the landlord for the Whitaker corner called. “Two other bidders dropped,” she said. “Yours is the only one with actual blueprints and a father willing to build shelving for free.”

“Not free,” Dad corrected from across the room. “For pie.”

She laughed. “Pie is currency in this town. Lease is yours if you want it.”

I hung up and leaned my head on the cool plaster wall. Dad whooped and did a little bend of the knee that made him look twenty years younger. Clara clapped, then immediately reached for a pen to write, Call Mrs. Leland about awning. I wrote our names on the line the next morning with a pen I’d bought just for this. I’d never understood the romance of a signature until the ink hit the page like a promise.

That afternoon, I drove by the apartment complex where Mom and Lauren had moved. I didn’t go in. I parked under a sweetgum tree and watched the second-floor balcony with the dying geraniums. For a moment, the door cracked and I saw a flash of Lauren’s hair. She stepped out with a bag of trash, dropped it into the chute, and disappeared back inside. No diamonds. No glossy hair light. Just a woman carrying the weight of a choice. I put the car in drive and went back to Dad’s house, to my spreadsheets, to the future that would ask for everything and offer back meaning.

On the day the deck oven arrived—a hulking beast wrapped in foam and promise—Dad stood with a crew of three men in the bare-bones shell of the shop. The walls were blush brick and optimism. We watched the delivery guys maneuver the oven into place with the reverence of men installing an altar. When it settled on its feet, every person in the room exhaled like we’d been holding breath for nine months.

Dad looked at me with tears he didn’t hide. “There,” he said, voice thick. “First heart in.”

“First heart,” I echoed, and touched the cold steel like it was a forehead.

That night, after the last contractor left and the street outside hummed with foot traffic and laughter, I stayed in the shop alone. I turned on one work light and sat on an overturned crate in the middle of the floor. The oven loomed, silent, holy. My phone buzzed. A text from a number saved as Unknown because I couldn’t bring myself to put a name to it.

I’m sorry, Em. I don’t know how to fix any of this. I’m trying. — L

I stared at the letters until they blurred. I typed and erased and typed again. Finally, I sent: Pay your restitution. Do your work. Be honest with yourself. That’s the part I can’t do for you.

Three dots appeared, then vanished. The screen went black. I tucked the phone away and looked up at the oven. I imagined the heat it would hold, the loaves it would birth, the mornings it would sanctify. I closed my eyes and, for the first time since the night of the party, I let gratitude take up more space than grief.

Because both were true: my family had broken and my future was walking toward me, one practical step at a time. The ledger in my heart had a column for each, and for once the numbers didn’t have to match to be right.

Part III:

The first time I fired the oven, the shop smelled like new paint and ghosts. Heat rolled out in a clean white wave, pushing the scent of drywall dust to the corners and inviting in a different air—one that knew sugar, one that felt like morning. I stood in front of the control panel with my hair pulled back and a damp towel over my shoulder, feeling the old thrill I used to get when my grandmother said, Now watch, baby. The magic part happens fast.

Dad hovered like a man introduced to his grandchild. “Temperature?”

“Four twenty for the biscuits,” I said. “Three fifty for the pies once we switch.”

He nodded gravely, as though the numbers were scripture and I was the priestess. On the prep table behind me, dough mounded under tea towels—flour mapped on the steel like the coastline of a new country. A tray of pecan filling gleamed like lacquered wood. Red velvet batter sat in a bowl so bright it looked obscene.

We’d spent the past eight weeks in a choreography no one could teach: finding the groove of the space, learning the weight of the door, the way the afternoon sunlight slanted in and made the counter glow like a stage. Dad had built the shelving from reclaimed oak, planing each board until his hands were as smooth as the wood. Clara had bullied the city permitting office with the kind of patience that breaks stone. Our sign—EMMA’S VINTAGE OVEN, black script on a cream enamel—had gone up the week before, and every time I drove past after dark, I parked and stared, letting the letters remind me that this was real.

“Timer,” Dad said, and I realized I’d been watching the glass, the biscuits rising into themselves, the butter flashing into steam. I set it, laughing. “You nervous?” he asked.

“About burning the first tray and cursing the rest of my life?” I said. “A little.”

He leaned his hip against the table, arms crossed—a stance he taught me when I was nine and wanted to look serious in a world that didn’t always take little girls seriously. “I’ve burned first boards,” he said. “You sand the scorch and keep building.”

The bell over the door tinked, and Clara swept in with a tote of linens and the air of an executive about to sign a treaty. “The awning came early,” she announced, dropping the tote and shucking her blazer. “They’re installing it now, and the letters are straight, praise be. I brought fresh dishcloths and a prayer I stole from Episcopalians.”

“We’ll take it all,” I said.

She peeked through the pass to the oven. “Well, would you look at that,” she breathed. “Bread in a box that’s going to pay for our sins.”

“Clara,” Dad said, half-scandalized.

“What? I tithe,” she said. She turned, her eyes landing on a rack of vintage plates we’d picked up at estate sales—the ones with gold rims and little sprays of roses. “You sure you want to serve on these? People will break them.”

“They’re meant to be used,” I said, smoothing my palm over porcelain. “Sitting pretty in a cabinet never saved anything.”

She tsked, which meant: okay.

We’d decided on a soft-open—three days, limited hours, tell no one but everyone you love. It felt safer than a grand opening that invited the city to judge our baby’s first breath. I’d posted a single photo on Instagram the night before: the sign glowing at dusk, my caption simple: Tomorrow, we bake for you. 8–2. Be gentle. It felt like leaving the door to my future cracked and standing behind it with a cookie.

The timer chirped. I opened the oven and the shop filled with the smell of a thousand mornings. Steam kissed my face. The biscuits had risen high and proud, tops glossy, edges craggy like the best parts of a coastline. I brushed them with melted butter and a whisper of honey, then slid them into the case. The glass fogged slightly. I wiped it with a towel and realized my hands were trembling.

“First dozen,” Dad said, low and reverent.

“First hundred dozen,” Clara corrected. “We’re claiming abundance.”

At 7:58, I unlocked the front door and flipped the sign to OPEN. The street outside was already humming with dog walkers and yoga pants and the city’s sleepy joy. A pair of tourists slowed, peered in, then kept going, as if unwilling to be first through a door they’d tell a story about later. I smoothed my apron and adjusted the ribbon in my hair. My hands remembered my grandmother tying hers, how the bow always sat a little crooked on purpose.

At 8:02, the first customer came in. Her name was Val, and I knew this because she’d been my client seven years earlier, when I’d designed the logo for her home staging business—a little house with a chair inside, simple as the truth. She wore a linen dress and the grin of a woman who knows a good secret.

“Emma Hayes, I could cry,” she said, and I nearly did. “Gimme two biscuits and whatever else you tell me I need.”

“What you need,” I said, voice steadying as I lifted the tongs, “is pecan pie for breakfast and no apologies.”

She laughed, the sound bouncing off brick. Dad hovered at the coffee machine like the intern on his first day, then pulled a shot that came out syrupy and perfect. He handed it to Val as if it were an offering.

By 8:30, the shop was full. People sat at the mismatched bistro tables we’d found on Facebook Marketplace. The bell sang every three minutes; the card reader chirped like a bird. A man in a bow tie told a woman in scrubs that the biscuits tasted like Sundays. A group of college girls took pictures with their cupcakes and made heart hands at the case. A retired couple split a slice of pecan pie down the middle and fed each other with the easy tenderness I want more than I want perfect teeth.

Clara patrolled like a benevolent warden, refilling water carafes and side-eyeing anyone who stacked plates too high. When a teenage boy dropped a vintage saucer and it shattered into three clean pieces, he went scarlet. Clara crouched, gathered the shards with a napkin, and said quietly, “Happens in the best families, sugar.” He smiled like she’d granted him absolution and tipped five dollars from his pocket into the jar labeled pie for folks having a hard day.

At 9:15, a woman I didn’t expect walked in. Susan Pierce, Dad’s lawyer, in a black sheath dress with a denim jacket over it because she’s that kind of Southern. She ordered coffee, then reached across the counter, squeezed my hand, and said, “Your father’s will is executed. I’m sorry for why that’s good news.”

I nodded, the air around my ribcage thick. Dad had insisted on finalizing everything quickly, the ink on our family’s legal story not even dry. The house, the investment accounts, a little vacation lot at Tybee he’d bought on a whim when I was a kid—they were mine now. Mine in a way that made me feel wealthy and also like a person who’d been handed a cathedral and told to keep the roof from caving in.

“You okay?” Susan asked.

“Yes,” I said, because saying no would require a different room and more Kleenex. “And no. And both can be true.”

She nodded like I’d passed a bar exam and left a twenty on the counter for a four-dollar coffee.

By noon, I moved like a person who had always moved like this—turn, lift, smile, listen, laugh, repeat. People brought flowers, and I put them in mismatched vases. People brought stories—about their mothers’ pies and their ex-wives’ biscuits—and I put those, too, on a shelf inside me that looked like a church.

Sometime after one, when the line finally thinned and the last batch of biscuits was cooling, the bell chimed again with a softness that made the hair on my arms lift. I looked up and saw my mother.

She looked smaller. Not thinner—just less. As if someone had released air from a place I’d never noticed was ballooned. Her hair was pulled into a low knot, and the scarf she’d worn to court was gone. She held her purse in both hands like she was attending a service. She didn’t move forward. She stood in the doorway as if she needed permission from the light to enter.

The entire shop shifted into a lower gear, not because anyone else recognized her, but because my face told them something holy or terrible had arrived. Dad froze mid-wipe, the dishcloth dripping into the sink. Clara took one step to the left, as if to place herself on a line between me and what could hurt me.

Mom’s eyes found mine, and for a beat too long, neither of us said anything. Then she took three steps and stopped at the counter. She looked at the case as if it were a museum she’d never planned to visit. “It’s beautiful,” she said, and her voice wasn’t quite steady.

“Thank you,” I said. I wiped the same spot on the counter twice for something to do with my hands. “What can I get you?”

She lifted her chin. “A coffee,” she said. “Black.” She paused. “And a piece of pecan pie.”

My grandmother used to say you can forgive a person across a table better than you can across a room. I cut the pie and set the plate down and tried to remember my training in kindness toward strangers. My mother wasn’t a stranger. She was the woman who’d taught me to fold napkins like lilies. She was also the woman who’d co-signed a theft of my future and called me dramatic when I named it.

She put a five-dollar bill in the jar without looking at me. Then, softer: “May I sit?”

“It’s a bakery,” I said. “Chairs come with the pie.”

She took a corner table and smoothed the napkin on her lap. Dad watched from the sink, immobile, jaw tight with a thousand unsaid things. Clara leaned in. “You want me to shoo her like a stray cat?” she murmured.

“No,” I said. “We aren’t that kind of house.”

I poured the coffee into a mug with a hairline crack that had never split and carried it over. Mom’s hand shook when she reached for it. She tasted the pie and closed her eyes, and for a terrible moment I wanted the approval I’d wanted since I was little. That’s the thing about parents—the wanting isn’t logical, and it isn’t optional.

“It’s… perfect,” she said, opening her eyes. “Just the right set to the filling. Your grandmother would say you nailed the blind bake.”

“She did say that,” I said, then bit my tongue. “Used to.”

She nodded, a twitch of pain at the corner of her mouth. We sat in silence for a moment. Then she leaned forward, voice lower. “I came to tell you that I’m making extra payments. On the restitution.” She brought her purse up like a shield and set a cashier’s check on the table between us. “Three thousand this month. I can do more as I sell some jewelry. And… some bags.”

I didn’t pick up the check. I wasn’t being dramatic. I was marking the boundary with an object in between us. “Thank you,” I said. “It’s what you owe.”

She flinched. The old me—the one built to ease discomfort—would have softened the words with frosting. The new me let them sit like unsugared tea.

She gathered herself. “I don’t expect you to forgive me,” she said, looking at the coffee. “I don’t even know what forgiveness looks like in this county. But I wanted you to know I’m not hiding from this.”

“You did, for a while,” I said.

“Yes,” she said. “I did. I told myself I was protecting Lauren. I told myself you had plenty. I told myself anything that wasn’t the truth.”

“And what’s the truth?” I asked.

She swallowed. “That I helped my daughter steal from my other daughter because I loved her fear more than I respected your future.” Her eyes glittered, and this time she didn’t catch the tear before it fell. “I’m sorry.”

I looked at her—the lines I knew, the hands that had braided my hair, the mouth that had said careless things that stuck like thorns. I took in the woman she was now: smaller, less sure of her magic, more aware of the price of everything. I didn’t reach for her hand. I didn’t push the check back. I kept my voice level. “Thank you for saying it. Keep paying. Keep telling the truth. That’s the only way the ground stops shifting.”

She nodded, defeated and dignified at once. She finished the pie in small bites. When she stood, she looked around the shop again, as if memorizing the place where she wasn’t the host anymore. “Tell your father… no,” she said, stopping herself. “I’ll write your father a letter.” She left the plate, the fork, the check. The bell sang as she went, and for a long minute the room held its breath.

Dad came over slowly, as if approaching a wild animal. He glanced down at the check, then up at me. “You okay?”

“I’m… standing,” I said. “Which feels like a lot.”

He nodded. “Do I need to—”

“No,” I said. “We’re not going to fight with a woman who brought a check and the right words. Not today.”

He relaxed. “You want me to frame that first dollar when it comes?” he asked, lifting the check with two fingers like it might bite.

“Frame the receipt,” I said. “We’re building a wall out of paper and grace.”

He chuckled, then sobered. “I’m proud of you.”

“I know,” I said, and I did. It felt like a railing I could hold on a crowded staircase.

By two, we’d sold out of everything but two slices of red velvet that looked lonely under glass. I flipped the sign to CLOSED, slid the deadbolt with a clunk that made my heart feel like a house. We cleaned in the muscle memory I’d learned from Dad—left to right, top to bottom, corners first so nothing gets trapped. The oven ticked as it cooled. The awning outside threw a doorway of shade onto the sidewalk like a welcome mat.

I pulled the deposit from the till and sat at the back table counting, lined notebook open, pen poised. Numbers lined up into columns that made sense. Dad poured three lemonades and brought them to the table. Clara kicked her shoes off under the chair and fanned herself with a menu she’d insisted we print on heavy stock. We sat for a minute, the kind of sitting that comes at the end of the first time you get something right.

“To the first day we lived through,” Clara said, raising her glass.

“To the second day we will,” Dad added.

“To the day I learn how to let what hurts make me honest without making me hard,” I said, surprising myself. We clinked and drank. The lemonade was too tart. I liked it that way.

After the deposit run and a shower that turned the day into history, I walked down to the river with a notebook. The sky layered itself into creamsicle and bruise. Tourists took pictures with plastic cups. A street musician played “Stand By Me” in a key that made it sound like a hymn. I sat on a bench and wrote a letter I’d never send—to my grandmother, to the person who’d taught me that heat reveals truth and that watching a butter cube disappear into a dough means you’re feeding someone you love.

We did it, I wrote. The oven held. The people came. The coffee didn’t break the machine. Dad smiled like he’d been holding his breath for a year and finally took a full one. Mom came and said the words that were due. Lauren texted sorry and I told her to pay what she owes. I didn’t shatter. I’m tired like I’ve never been tired. I’m new like I’ve never been new.

When I looked up, the water had gone almost black, with trims of fire where the last light hit. I thought about how the river keeps moving whether we bless it or curse it. I thought about how greed had cracked my family and how truth—mean, faithful—had kept the house from falling in. I tucked the notebook under my arm and walked home, feeling like a person who was beginning again and again and again until the beginning looked like a life.

Two weeks into our soft-open, Savannah Magazine called. The editor had seen photos on Instagram—Clara’s bridge club apparently had more reach than a PR agency—and wanted to do a feature: A Southern Gem on Whitaker: Emma’s Vintage Oven Brings Back the Morning. I said yes and hung up and laughed until I cried.

That Saturday, a line formed out the door and down the block. A girl in a lavender dress read a book while she waited. A man in a suit bought six biscuits and handed four to the men behind him. An elderly woman touched the glass case like a reliquary and whispered, “My mama used to blind bake with dried peas.” I wanted to fold the entire city in butter and call it kin.

After the rush, I stood at the pass and looked out. The shop was noisy and kind, messy and honest. There were crumbs on the floor and fingerprints on the glass and laughter lodged in the rafters. Dad leaned against the counter, telling a teenager why you don’t overmix dough if you want high rise. Clara fielded a phone call about a woman who wanted to donate a set of Depression glass if I promised to use it. The bell chimed. The oven hummed. The ledger in my heart, for a minute, balanced.

And that’s when Lauren stepped in.

She wore jeans and a plain white T-shirt and the face of a person who’d been through a long hallway without windows. She carried no purse. Her hair was pulled back in a no-nonsense tail. She stood just inside the door, waiting as if there were a line and she could not cut even if she was drowning. The room dimmed around her, or maybe that was me. I set down the towel and walked to the counter.

“Hi,” she said, voice soft. “I didn’t come to make a scene.”

“Good,” I said. “We don’t do those.”

She nodded. “I’m—” She stopped, then tried again. “I got a job at Harper’s on Broughton. Retail. It’s… humbling.” She swallowed. “This week, I made my first restitution payment. I know you don’t need me to tell you. The DA’s office emailed. I thought you should hear it from me anyway.”

“Thank you,” I said, because the words mattered even when the money did most of the talking.

She looked around the shop, an awe that hurt crossing her face. “It’s beautiful,” she said. “It’s so you it’s like you grew it.”

I followed her gaze. “It’s me and Dad and Clara and a dozen people who taught me and a city that likes butter,” I said. “And it’s work. Every day.”

She nodded slow. “I picked the wrong kind of work for a long time. I worked on my mirror instead of my spine.”

I blinked. The metaphor sounded like something she’d read in a self-help book. Then I decided not to care where she’d found it. If it fit, it fit. “How are you?” I asked, against my better judgment.

“Mostly ashamed,” she said. “Sometimes hungry. Sometimes hopeful. Can I… buy a biscuit?”

“You can pay full price,” I said, and we both knew it was the only right answer. She smiled like a person being allowed to be a person again and slid a crumpled five across the counter. I handed her a paper bag and a little cup of jam. She took one step back and then, in a voice barely audible, said, “I’m proud of you.”

“Good,” I said, surprising myself with how little I needed it and how much I wanted her to say it anyway. “Be proud of yourself when you make the next payment. And the next.”

“I will,” she said, and left, the bell chiming her exit like a benediction.

When the day ended, I locked the door and leaned my forehead against the cool glass. The world outside moved—bikes, dogs, people with plans. Inside, the shop glowed. Dad put a hand on my shoulder. “You sure you want to keep doing this?” he asked, not because he doubted, but because he knew the price.

I turned and looked at him, at the lines the past months had carved deeper, at the light the oven had put back. “Yes,” I said. “I want to keep getting up at four to make biscuits and choosing honesty over easy and loving people with food and boundaries. I want this so much it makes my teeth hurt.”

He laughed, then kissed my forehead the way he had when I was eight and scared of thunder. “Then we’re home.”

We walked through the dark shop toward the back, flipping off lights one by one. The oven ticked itself cooler. The sign outside went dim. I pocketed the keys and felt their weight. The city’s night pressed soft against the windows, and for the first time in a long time, I trusted it.

Part IV:

August in Savannah doesn’t arrive; it settles. Heat lays its full weight across your shoulders and asks you if what you’re carrying is worth also carrying it. By the first week, I could answer: yes. The rhythm at Emma’s Vintage Oven calcified into muscle. My alarm sounded at 3:35 a.m.; I rolled out of bed already tasting flour. By 4:10, the oven’s first sigh warmed the shop like a living chest. By 6:00, dough rose and fell, a gospel choir. By 8:00, we were in it—orders stacked, coffee spitting like a pleased cat, the bell jangling an arrangement that never repeated the same way twice.

We added a chalkboard that Clara lettered with missionary zeal: Today’s Gospel: pecan pie, red velvet cupcakes, cheddar–jalapeño biscuits, and the truth will set you free. She underlined truth twice and dared me to erase it. I didn’t.

Dad had taken to teaching impromptu lessons to anyone under twenty who wandered near the pass. “See this lamination?” he’d say, splitting a biscuit and tugging layers apart like lace. “That’s because you don’t overwork the dough. Same with folks.” The kids laughed. Some of them came back with friends. He started keeping a little toolkit in the back for fixing skateboards and backpacks. I called him the shop’s unofficial foreman of broken things. He pretended he didn’t like it and wore the title like an old flannel.

Lauren came on Saturdays, always at the end of rush when the shop’s hum lowered to a contented purr. She never skipped restitution; I knew because the ADA’s office sent notifications with bureaucratic precision. The first week, she bought a single biscuit. The second, she added a coffee and left a dollar in the hard-day jar. The third, she asked if we could donate day-olds to the shelter where she’d started volunteering to meet her community service hours. I said yes, and, later that night, I cried into my speaker because the song on the radio knew too much about sisters.

Mom wrote letters. I kept them in a shoebox with my grandmother’s apron ribbons and the lease copy, all the important threads of this new life. The letters were never long—two pages, max—and always in her neat, Catholic-school script that had signed permission slips and prom corsage checks. They were full of statements and without demands: I sold a bracelet today. Extra payment enclosed. I’m working at a clinic answering phones in the afternoons. The work is not glamorous. It is steady. I’m learning to be grateful for steady. And, on one page that smelled like her rose hand cream, six words that punched a hole clean through me: I’m proud of your stubborn, honest heart.

I didn’t reply. I wasn’t ready to write to the woman who’d taught me how to fold napkins like lilies and also how to fold truth when it got inconvenient. But I read every word. Sometimes I held the paper against my chest like you hold a baby that isn’t yours yet.

One afternoon a storm rolled in like a rumor that turned out to be true. Customers gathered near the windows, watching the sky bruise, then break. Rain hammered the awning and made the world a series of small rooms. A man in a soaked suit hustled in, blinking, cell phone pressed to his ear. He ordered coffee with a voice that had never learned please, tossed a corporate AmEx onto the counter, and continued his call: “I don’t care what the DA says about optics…”

DA. Optics. My spine pricked. I slid his coffee across, caught Clara’s eye. She tilted her head toward the pie case, then toward the man—the Clara code for don’t give a jerk free sugar. I hid a smile and turned back to the oven.

He ended the call and checked his watch. The shop had fallen into the storm’s hush; voices rose and fell like oars. He stared at the chalkboard. “Truth will set you free,” he read aloud, doing that thing men sometimes do where they try the words on to see if they fit them better. “You believe that?”

I wiped a ring of condensation from the counter. “I do,” I said. “But it usually takes longer than you want and costs more than you planned.”

He snorted, then really looked at me. “You Hayes?”

“Emma,” I said, wary.

“Small town,” he said. “You’re the one whose father called the cops on his other daughter.”

“On his other daughter?” Clara said mildly, appearing at my elbow like a storm cell. “Feels like he called the cops for the daughter who got robbed.”

The man held up his hands, concession or mockery, hard to tell. “Point taken,” he said. “Any case with family and money gets around the courthouse quick.”

“Do you work at the courthouse?” I asked.

“Public defender,” he said. “Sometimes prosecutor when the budget’s light and the politics are heavy. Savannah—town of many hats.” He sipped. “Good coffee.”

“Thank you,” I said, because the alternative was spitting in it.

He nodded at the jar. “Pie for folks having a hard day?”

“Sometimes the only thing that makes a difference is a small thing that doesn’t,” I said.

He tilted his head in a way that looked like respect. “You’ll do fine.”

“Doing fine and being fine aren’t synonyms,” I said.

He grinned. “You sure you don’t want law school?” He left before I could answer, which was good, because my answer was a mess of grief and gratitude and a stubborn streak that had been fed, finally, with the right kind of fuel.

The Savannah Magazine feature hit the stands on a Wednesday. The photo made us look as if a movie set had hired us to play ourselves: me behind the counter with flour on my cheek, Dad in his shop apron holding a cooling rack like a baby, Clara in the background pointing at something no one else could see. The headline read, Heat, Truth, and Butter: How a New Bakery is Restoring a Family’s Faith (and Yours). I winced at faith—always a slippery word—and then decided it could sit there if it liked.

That afternoon, a white-haired woman came in with a copy of the magazine under her arm. She unfolded a two-dollar bill from her wallet and smoothed it on the counter. “My mother kept a two-dollar bill in the sugar canister for emergencies,” she said. “She said sweetness was where we’d remember it. You’ve put something sweet back here. Please spin it into pie for someone who needs to remember themselves.”

I took the bill and slipped it under the jar’s bottom like a foundation stone. “Yes, ma’am,” I said, thick-throated.

That night, the shop empty and the floor mopped to a squeak, I found Dad sitting at a table with an envelope. His face had been rearranged into an expression I knew from the mirror—joy and sorrow braided into something useful. He slid the envelope toward me. Inside: a check from the city for a small grant supporting new businesses on Whitaker. We’d applied months ago; I’d forgotten just to keep my heart from breaking on schedule.

“Look at the date,” he said.

I did. It was my grandmother’s birthday.

“You know she’s laughing,” he said. “Wherever she is, she’s laughing and telling some angel to put more butter in the batter.”

We both laughed in a way that ended as a prayer.

The fault lines in our family didn’t heal. They shifted. On a Sunday after church—my church being the oven, Dad’s being the porch—Mom knocked on the shop door during our closed hours. She held an envelope and a grocery sack, the most ordinary accoutrements of apology. I hesitated, then unlocked it.

“I brought collards,” she said, almost sheepish. “And cornbread. Your grandmother’s recipe. The one I never shared with anyone outside this family.”

“That seems… symbolic,” I said, because the alternative was flinging the door open and crying into her blouse, and we weren’t there.

We stood in the quiet that used to be comfortable. Her eyes flicked to the oven, then back to me. “I wrote to your father,” she said. “He wrote back. He said he hoped I was well. He said he appreciated the extra payments. He said he was proud of you.”

“He is,” I said. Saying it made the room warmer.

She set the bag on a table. “I don’t know what part I get to have here anymore,” she said. “I’ll take the part you give me. Even if that’s just eating collards at a table in the corner and paying like any customer.”

“Mom,” I said, the word sounding less like a cry and more like a fact. “Right now, the part is honesty and payments and time. Later… maybe something else.”

She nodded. “Time is heavy.”

“We lift heavy things with our legs,” I said, and the joke unhooked something in both of us. She smiled and touched my elbow briefly, a contact not long enough to make promises. Then she left, the bell giving a small amen.

We hired our first part-time baker in September—a woman named Tasha with forearms like an athlete and a laugh that made the oven preheat faster. She’d baked at a hotel for years, mastering the art of turning out perfection for people who never saw the kitchen. She wanted to be seen. I offered twelve dollars an hour and a promise that I’d pay more as soon as I could. She took it and, on her first day, taught me a trick with cold butter and a box grater that shortened my prep time by fifteen minutes without touching quality. I gave her a raise that afternoon. We wrote the new rate on the calendar with a star and a note: Raise because Tasha is a magician.

We added a small Friday-night event called Stories and Slices. We slid the tables together and put out pie. People stepped up to the mic and read two minutes of whatever they had—poems, breakup letters, a kid’s essay about his dog. I read, too, a piece about blind baking that was actually about choosing pain on purpose because it makes the crust hold. The city showed up with their hearts in their hands and their dollars in their pockets. More than once, someone looked like they’d come to tell a secret and left with something lightened on their backs. That’s all I’d ever wanted from a place with my name on it.

But not all nights ended sweet.

On a Thursday, thirty minutes to close, a thin man with a face like a sharpened question approached the register. He stood too close in that way desperate people do when they want to be seen, then hate being seen. “You Emma?” he asked, peering at the name pinned to my apron as if it could betray me.

“I am,” I said, careful.

“I’m here for Lauren,” he said. “She owes me.”

“Lauren is not here,” I said. “And if you think walking into a bakery to collect a debt from a woman’s sister is your best move, I would suggest you recalibrate.”

He sneered. “She took my investment. Said she’d pay me back when her brand popped again. Then she got herself arrested.”

Blood rose in my ears. “Sir,” I said, and Clara materialized at my side, and Dad—somewhere behind the counter—set down something metal with enough emphasis to communicate: I am a man who builds houses from the ground and I know where the studs are. “If you have a claim, the district attorney’s office can advise you. If you’re here to intimidate, you can see yourself out before my father calls the cops in this county again.”

He blinked, something like calculation sloshing behind his eyes. Then he lifted his chin, spat on the floor by the twist of the doormat, and left. The bell rattled angrily. I exhaled and realized my hands were trembling. Dad handed me a towel. I wiped the spit with slow, exaggerated care, then sprayed the spot until the floor smelled more like lemon and less like regret.

“You okay?” he asked.

“No,” I said. “And yes.”

“That’s the usual,” he said, squeezing my shoulder.

I told Lauren the next day—no drama, just the facts. She pressed her lips into a line and nodded. “He thought my pretty would pay his hunger,” she said. “He’s learning what I’m learning: the only pretty that pays is the kind you can do eight hours a day with a lunch break.”

“How are you?” I asked.

“Mostly ashamed,” she said, and we smiled because it had become our shorthand for the work of repair. “Sometimes proud. I folded sweaters all day and nobody followed me into a changing room. It felt like dignity.”

“Keep it,” I said. “You’ll need it when the shame gets thirsty.”

By October, the air thinned into kindness. The marsh flipped from bright to burnished. We added apple pie to the case and the scent woke something in customers that sounded like childhood. The magazine feature kept sending people. The hard-day jar filled then emptied then filled again, proof that generosity and need run on a single circuit.

I found a rhythm with Mom that felt like a safe bridge. She came by on quiet afternoons, bought coffee, left cashier’s checks, and sat at the corner table reading a paperback like a regular. Sometimes Clara joined her and they talked in code about old PTA battles. Dad stayed in the back those days, not out of spite but out of the respect for scar tissue that pulls when it’s poked.

On the first Friday of November, we hosted a Thanks & Pies night where we let people write one-line thank-yous on butcher paper hung across the back wall. The room swelled with ink: Thank you to the nurse who didn’t sigh when I cried. Thank you to my grandson for calling me back. Thank you to whoever found my dog and put their number on his collar. Thank you to my sister for learning to say sorry and then proving it. I pretended I didn’t know who wrote that last one.

There is a moment in any build where foundations become floors. You stop tripping over rebar and start rolling out rugs. In late November, we had that moment. I was mopping at close when my phone buzzed. A number I didn’t recognize. I ignored it, then listened to the voicemail while counting tips. “Ms. Hayes,” a calm voice said. “This is Dr. Patel from St. Joseph’s. Your father’s okay, but he had chest pains and came in. He asked us to call you. He’s stable.”

The mop handle slid from my hand and clattered in a slap I felt in my teeth. The world narrowed to a tunnel with too much light at one end. Clara grabbed her keys. “I’ll drive,” she said, already at the door. Tasha called after us, “I’ll lock up!”

The ER smelled like bleach and fear. I found Dad propped up, face pale against hospital white, a tube in his hand, monitors doing their polite beeps. He smiled, because that’s who he is, even when the world tries to remove that part.

“False alarm,” he said, voice light. “Or maybe a true alarm caught early.”

Dr. Patel explained words I tried to hold: angina, stress, precaution, overnight observation. The kind of news that shakes you and leaves you grateful with your hands shaking. Dad squeezed my fingers. “You’re not allowed to lift the oven by yourself,” he said.

“You’re not allowed to carry the world by yourself,” I said back, and he grimaced like a man who’d been seen.

Mom arrived ten minutes later, breathless, hair uncoiling, a cardigan on inside out. She stopped in the doorway like a border guard, waiting to be admitted to a country she’d left without a passport. I nodded. She came to the bed and took Dad’s other hand, and for an hour we formed a bridge around the man who had built the floor under both our lives. Lauren came and stood at the foot of the bed with eyes that understood the topography of fear. Clara signed the forms like a woman who keeps pens for moments of soft emergency.

When they discharged him the next day with prescriptions and instructions written large, we took him home and did what we’d learned to do: made lists. Low sodium, more walking, less I will fix it with my back and my will. He grumbled. We complied. At the shop, he taught instead of hauled. At home, he let me carry boxes up the stairs he’d built with his hands. I caught him once looking at me like a man who’d placed a beam and watched it hold.

“I need you to outlive the oven,” I said.

“I need you to live so good the oven tries to keep up,” he said back. We made a pact to both try.

Thanksgiving week at the shop felt like a revival—pies stacked like promises, customers hugging near the register like people joining a church. On Wednesday at close, the last pecan cooled on the counter. I wrote a sign for the door: See you Friday. Eat with people who feed you. I taped it up and stood in the doorway, light behind me, street before me, the whole map of what we’d built spread like a new country I could finally call home.

I turned the sign to CLOSED and locked it. Behind me, the oven ticked like a faithful clock. In my pocket, my phone buzzed—Lauren: Payment made. Also, saved you a seat at Dad’s tomorrow. If you want it. I typed: I do. Save me the one by the window.