Part I:

The first time I saw Kelsey Quinn she was wearing a powder-blue cardigan stitched with cartoon daisies and a smile too bright for the gray carpet and drop ceilings of the 28th floor. Our office was the kind of place that believed in “open concept” but still managed to feel like a maze—the partitions were low enough to hear the sales team’s daily whooping yet high enough to block every patch of real sunlight. We were in the Chicago Loop where the sidewalks were wind tunnels and the coffee was always three dollars too much. People adapted by cultivating expressions of caffeinated resignation. Kelsey arrived with an expression that belonged in a boutique cupcake shop.

“I’m Kelsey,” she chirped, setting down a tote bag sprinkled with holographic hearts. “I brought cookies! But they’re gluten-free, because I care!”

I said my name—Lena. I’ve been at Meld & Mesa Media, a mid-size marketing firm, for a year and change. In the org chart I lived in the rectangle beside Kelsey’s. Same title: Marketing Analyst. Same junior rung on the ladder. I’d learned that if you didn’t watch your step, rungs became trapdoors.

Our manager, Doug Barnes, emerged from his glass office by the printer bank. He had the paunch of a desk lifer and the swagger of a man who’d once captained the JV football team. His scalp was a low-tide shoreline of hair. Folks called him “Barnes” in emails and “the Collector” after hours because he collected busywork the way other men collected stamps. Barnes’s love language was delegating.

“Kelsey!” Barnes boomed. “Welcome aboard. You look young as a spring day!”

Kelsey tucked hair behind her ear in a way that would’ve looked rehearsed on anyone else. On her, it looked—well, rehearsed too, but with conviction. “Oh my gosh, thank you. I’m older than I look. I’m twenty-six,” she said, as if we should gasp.

We did not gasp. Ty from design threw me a look across the partition that said: buckle up.

During Kelsey’s first week, she was exactly how you want a new hire to be. She arrived ten minutes early. She asked where the forms lived in SharePoint. She said “please” to the copy machine. She wrote notes with several hearts dotting the i’s. People were charmed or at least decided it cost nothing to be. Even Hannah from analytics, a stoic who wore the same black turtlenecks year-round, pronounced Kelsey “harmless.”

I should’ve listened to the weather change more carefully.

On the second Friday, Barnes called the team to the “Bullpen,” which was basically two four-tops pushed together beneath a poster that read TEAMWORK MAKES THE DREAM WORK in a faith-based font. He announced a tiny team-building dinner at Osteria Classico, a partner restaurant that gave us corporate discounts and free desserts if we remembered to tag them on Yelp.

“Company says I get to take you all out,” he said, grabbing his belt like a country sheriff. “Nothing fancy.”

We all knew “nothing fancy” meant the opposite of company card fireworks. At this firm, fancy was something performed for clients and discarded behind closed doors. But Carmen from HR was there with her cherry lipstick smile, and everyone knows free dinner is its own religion.

At Osteria Classico the server brought tap water in green glass bottles and a basket of bread too hard to insult. We passed around plates of rigatoni, chicken piccata, yawned a little, dared each other to order a second drink then remembered Barnes was counting around the edges of his eyes. The atmosphere loosened just enough that Ty told a story about his seven-month-old who hated peas with opera-level commitment. Even I forgot to feel defensive.

The desserts arrived in a parade of white plates, each with a small glass dish of mango panna cotta crowned with a mint leaf the size of a thumbnail. The server winked like he was handing us contraband sugar. “Compliments of the house,” he said. Everyone lifted the same spoon at the same time. We ate the same sweet velvet.

Kelsey lifted her phone at an angle that made her eyelashes look like separate entities. Flash. Tap. Tap tap. A soft giggle, a tiny gasp. “This is, like, my favorite dessert of all time,” she announced. “I cannot believe Mr. Barnes remembered!”

I thought: He didn’t. I watched the server ladle those little puddings onto a tray at the bar, one for each seat we occupied because that’s the kind of math Osteria Classico excelled at: one-for-one, no heroics.

But then my phone pinged like it owed somebody money. Ty’s pinged, Hannah’s pinged, even Carmen’s pinged, which was impressive because I’m not sure HR receives notifications like civilians. Kelsey had posted to Instagram, then to Facebook, then to a cross-posting service I’d never heard of but that stamped her photos with a gentle pastel frame. The caption was written in a calamity of cursive fonts:

out with the team for a little business mingle and someone special ordered my favorite mango pudding because he says I’m “such a kid” 💛🍮 felt sooo seen 🥹

There was a boomerang video of Barnes doing that awkward half-nod men do when they don’t know they’re being filmed. The mango glowed like an apology the restaurant didn’t owe.

I felt the team compress, everyone performing the same polite breath. Maybe people like Kelsey needed a narrative state more than a real one. Maybe Instagram was Kelsey’s primary employer. We said nothing. Ty forked the last of his lemon tart into his mouth, the fork a small shield.

On the subway later, I looked again at the caption. “Someone special” had “special” italicized and “someone” not. A grammar of implication. I tried to be an adult about it. I told myself it didn’t matter what other people recorded; truth was a busy street, not a museum. Still, a small annoyance kept trying to grow up into anger.

Monday arrived in its business casual. I had thirty minutes to pull numbers for a client before the 10 A.M. call. Hannah was deep in an SQL swirl and told me to ping her if I hit a wall. Barnes slid from his office like a bar of soap.

“Lena, do me a huge favor,” he said, tossing a folder onto my desk. “Tell Kelsey to knock out this consolidation sheet. By EOD.”

I checked the clock. 5:32 P.M. already belonged to the office lighting’s cruel honesty. “End of day today?” I asked, verifying the cruelty.

“Yup,” Barnes said. “You know how it is.”

“Don’t we have a policy against assigning new tasks after five?” I didn’t say this out loud. I just willed it into the air like a paper airplane doomed by physics.

I walked the folder to Kelsey. She swiveled toward me, tucked her chin, and curled her lower lip like a question mark.

“So—Barnes wants this done today,” I said, keeping it gentle. “It’s a simple consolidation, mostly copy-paste into the master. Should be a couple hours.”

Her eyes grew dewy on command. Then the hands: she folded both of mine into hers and shook them like we were preparing a prayer. “Leeeena,” she cooed, dragging my name across the carpet. “Please don’t make me do this tonight. Don’t be mean to me.”

I’m not proud of how my skin crawled at that. In another life maybe I would’ve found it cute, the theatricality of it. Or maybe I’m wrong; maybe no woman reaches twenty-six without identifying the exact pitch of “please” that makes a colleague’s spine clench. I extracted my hand as politely as if I’d accidentally touched the stove. “It’s from Barnes,” I said. “Not from me.”

“OMG,” Kelsey said, twisting a strand of hair around her finger. “Can’t he ask you? You’re sooooo good at this stuff.”

“Barnes asked you,” I said, and escaped like a person leaves a haunted room: briskly, without admitting fear.

I went home and allowed the shower to do its hollow thing. Halfway through towel-drying my hair, my phone lit up like a slot machine. A direct message from Ty: Did you assign Kelsey a task? She’s telling Hannah you dumped your work on her.

I squinted at the steam. No. Barnes did. I said it came from him.

Five minutes later, Hannah: Barnes knows? Kelsey says you used his name.

I sat on the edge of the tub and texted, He literally gave me the folder. I can walk it back to him. Want proof?

We all have our own definitions of proof. Some days proof is a folder on a desk. Some days it’s a screenshot floating like a jury’s decision.

The next morning, Barnes handed out milk tea to the team, an innocent kindness paid for with a departmental card. He’s not a monster, I remind myself sometimes; he is a man whose habits are more powerful than his flaws. He asked, “Everybody good?” and we all chorused something that sounded like “Yes” but could also have been “Yikes.” Kelsey lifted her cup and sighed in theater. “This one’s too sweet,” she pouted. “I don’t like sweet.”

“Why didn’t you ask for less sugar?” Carmen asked.

“I didn’t want to trouble Mr. Barnes,” Kelsey said, tilting her head so that her hair fell like a curtain of excuses. “I never want to be a bother.”

By lunch we’d all seen her post: a nine-panel story of the same milk tea from angles I didn’t know a cube could support. The caption: He knows the little things that make me smile, even the silly cartoon bear on the cup. Sometimes being seen is better than being understood.

“Barnes ordered the cheap place because he’s saving budget,” Ty whispered over Slack. “We got cartoon bear because cheap place prints cartoon bear.”

“You can buy a ring with the money he saved,” Hannah typed, then deleted, because Hannah does not leave fingerprints where she eats.

I wasn’t angry yet. Not exactly. Watching Kelsey was like watching a child narrate a game to make losing sound like winning. It would have been endearing if there hadn’t been a scoreboard with our names on it.

A week later Barnes brought Kelsey into his office, and I watched their reflection in the glass: his hands shaping tasks in the air, her head bobbing in high-frequency agreement. She emerged cradling a manila folder like something small and precious. She held it up for me to see, demure as a Disney side character. “He called me his right hand,” she said. Then she took a selfie with the folder and posted a caption that ended with: some people get me in ways that make me want to be better 💛

Barnes had, in fact, found the perfect mule for his junk miles: a soul who believed the weight was a crown.

At 9:41 P.M., a new post: a desk bathed in lamplight, spreadsheets open like prairie. The caption: You ever seen 4:00 A.M.? Morning star girls know. 🌟 The comments chimed in with diamonds and “queen”s and exhortations to “grind.”

I went to bed angrier at myself than at Kelsey. Because what did it matter that her posts were fiction embroidered onto boredom? Because I wanted the world to be the kind of place where a mango panna cotta remained exactly what it was: a free dessert for everyone. Because I was too old, at twenty-eight, to be undone by the choreography of a colleague’s eyelashes.

The next morning, Barnes cornered Kelsey by her desk. “Did you stay up until four working?” he asked, sounding half like a boss and half like a dad trying to be a boss.

Kelsey’s smile trembled. “Oh God no,” she said. “It was just a silly meme.”

Barnes blinked, insulted by the boundary. Managers prefer lies that flatter their systems.

Work is made of little exchanges. You ask, they ignore; you tell, they pretend not to have heard. You refrain, rumors grow teeth. By the time Friday arrived, I’d rehearsed half a dozen speeches in the mirror and thrown every one away. The city looked like a magazine ad for itself. Somewhere in it, Kelsey was probably composing a sentence about how the bridge lights reflected in the river were little promises coming home. Good for her.

Only it wasn’t good for us.

That evening, when we were locking our computers and retying our scarves, Kelsey bounced over to me, all ponytail and possibility. “Lena,” she said, “if I finish this big report for Mr. Barnes this weekend, do you think I’ll get a raise? Like, what’s normal here for, like, heroes?” She widened her eyes.

“Don’t set yourself up,” I said, which apparently means “tell me more” in Kelsey-speak.

She squeezed my forearm—two pumps, like they teach in certain sorority houses, I’m told. “Not even a bonus?” she asked, hope like champagne threatening the lip of a flute.

I shrugged in a way that was supposed to read “gently realist” and probably read “murderous aunt.” “The company rewards KPIs tied to your actual job,” I said. “Extras are nice. They don’t move the needle.”

Her mouth formed a perfect O of disbelief. “But Mr. Barnes says he sees potential in me.”

I thought of potential like a landlord. It can evict you when rent is due.

“You asked,” I said, squeezing back, “so that’s my two cents.”

By Monday, the weather had changed again. I couldn’t name it yet. But something in the office’s barometric pressure had dropped. And Kelsey, who interpreted pressure as proof of her specialness, rode the change like a glitter-saddled horse.

It would take a 2:00 A.M. plane, a $12 bagel, a cracked door, and a fistful of hair before the weather finally broke.

Part II:

I tell you this because the second act of any office tale is always about hunger. We’re constantly averaging our appetites—attention, money, credit—against the pantry of the company. Sometimes there’s a sale. Sometimes a food fight.

It started with a spreadsheet, the kind of file that announces itself like a sigh. Barnes wanted a legacy report: five years of client engagement data compiled across a scatter of “temporary” folders that had died and reincarnated monthly under new names. Half the team had dodged that bullet by tucking their feet under their chairs when Barnes came by with his request face. Kelsey, smelling the chance to attach a ribbon to her name, had offered both hands.

By Day Two, she looked like a sugar sculpture left under a heat lamp. She drifted cube to cube with a wilted expression and the refusal to ask questions in plain English.

“Lena,” she said, materializing beside my chair, her shadow landing on my keyboard, “could you just, like, help me a teensy bit? I made the pivot table but it keeps farting out the wrong numbers.” She giggled at “farting,” then performed an instant wince to apologize for having said it, as if she had been surprised, poor dear, by the carnality of her vocabulary.

I pinched the bridge of my nose. “What does ‘teensy bit’ mean?”

“Just, like, show me how to do it…with my data.” She pointed at her laptop—glossy stickers spelling K-E-L-S-E-Y in a swoop of glitter cursive.

“Okay,” I said. “Scoot.”

She scooted. I taught. I stood there while she typed as if each keystroke were part of a choreography, a tiny lift, a delicate drop. Every three minutes she made a soft noise of effort, just barely in the octave of a whimper. It was weaponized helplessness, and I hated that the word weaponized occurred to me at all, as if we were at war. I didn’t want to be at war in a building that smelled like lemon wipes and expense reports. I wanted to go home.

“Thanks, angel,” she said when I’d wrestled the data into a shape—the basic rectangle of truth. She took out her phone. “Smile.” Click. And now the post: When your work bestie saves your life with formulas, you give her your heart!!! She added a filter that sprayed gold dots across the photo, like we were in a commercial for a brand-new credit card.

The next morning, Barnes swung by, tapped Kelsey’s desk in the rhythm of impatience. “Saw your post,” he said, trying for casual but landing on cringey uncle. “You up till four again?”

Kelsey squeezed her mouth shut as if she’d just been told a secret shaped like a lemon. “Noooo,” she said. “That was a joke joke.”

Barnes squinted, then turned to the team. “Y’all could learn something from Kelsey’s attitude, though. She’s finding joy in the grind. That’s called maturity.” He said maturity with the authority of a man who had recently decided to go dairy-free.

Ty sent me a Slack ghost: 👻. “We are being haunted by someone else’s brand,” he typed.

I typed back: “It’s mango-pudding nation out here.”

And then the team dinner became the Team Dinner. The dessert that had wanted so little from us—a spoon, a swallow—metamorphosed into a symbol of specialness. In Kelsey’s posts it became pudding with a u, as in British Netflix romcom voiceover: pud-ding. In our private jokes it became currency. “Will Barnes order you another mango pud-ding, princess?” Ty whispered when Kelsey breezed to her desk in yet another cardigan with cartoon animals cavorting over the hemline.

I should’ve felt bad for the mean edges of our jokes. I did and didn’t. Cruelty in an office is like black mold—nobody put it there on purpose, and everybody swears they don’t smell it until a wall comes down. To complicate my guilt, Kelsey seemed to be living a parallel life in which we were all extras. On her Instagram we were always out-of-focus chairs and tidy napkins around the illuminations of her face. Comments snarled and purred beneath her posts: You’re a literal doll. How are you real? Find a man who treats you like your boss does.

The last one stuck like a chicken bone in my throat.

The day Barnes publicly praised Kelsey for her four a.m. “perspective,” three things happened:

- Hannah closed her laptop with surgical calm and went to the break room for a ten-minute stare at the wall.

- Ty typed,

Okay I’m going to slap a bow on my depression and call it a productivity enhancer

- then deleted it, then typed,

Seriously though, I hate that this is working,

- then deleted that too.

- Kelsey did a little victory shimmy in her chair, a shoulder roll that might have been adorable if you removed the context, the office, gravity.

We told ourselves it would burn out. Even performance art has a run time. But fiction has an appetite. It wanted more.

Two days later, Barnes announced a daytrip assignment: a same-day flight to Detroit to walk a client through revisions they’d already ignored three times. “In and out,” he said, the way men say it when they’ve never been crowds in TSA.

The seniors had their calendars “full.” The middle rung, among whom I counted myself, developed sudden meetings, sudden headaches, sudden childcare. The only volunteer was Kelsey, who heard “plane” and “hotel” and wrote an entire screenplay on her face.

“I can do it,” she breathed. “I don’t mind flying.”

“Great,” Barnes said, inflated by the appearance of selfless compliance. “We booked you on the red-eye out of Midway—well, red-eye-ish. Two A.M. You’ll land at four. Grab a shower at the hotel. The meeting’s at nine. You’ll fly back at six.” He nodded like an airline apologizing for turbulence. “We keep costs down; it’s good optics with Procurement.”

Kelsey saw none of the sentence past “flight.” She posted before she left the building: He said, ‘Kels, I trust you.’ First business trip, here we gooooo. A boomerang of her suitcase spinning in a circle like a toy.

Ty and I stared at the same screen, texting in disgusted harmony.

Just wait, Ty wrote.

She’s going to write poetry about gate C7, I said.

At 4:02 A.M., under fluorescent airport light that made everyone look like a medical illustration, Kelsey stood before the floor-to-ceiling windows and repeated her four-a.m. brand. The caption: Somebody once told me I’m a baby, so he booked me a flight to see the night from above. There were heart emojis and one photo of a full moon that could’ve been anywhere, any year.

At nine, while she was somewhere in a conference room drinking coffee that tasted like everyone’s second thoughts, Barnes gathered us for a huddle. He had his hands on his hips, the universal sign for “I’m about to convert pity into leadership.”

“Pay attention to what Kelsey’s doing,” he said. “No whining. She’s up at insane hours, but she’s making it an experience. That’s the kind of attitude that goes places.”

Hannah’s eyes met mine over the rim of her mug—empty, thank God. Ty made a sound like a laugh and a cough had a baby.

That afternoon, Kelsey returned sallow and shining, like a candle that had been lit all day in a hot church. She looked like she might fall asleep upright. She looked like the idea of triumph had vacuum-sealed her exhaustion.

“Did you get a per diem?” I asked, because sometimes kindness wears a practical face.

She blinked. “What’s that?”

“It’s…money. For food.”

“Oh!” she chirped. “No, but it’s okay. I wasn’t hungry. The sky was enough.”

“Okay,” I said, because what else can you say to a person who believed the sky was edible.

And that might’ve been the end of it. Kelsey would have posted her sky copy. Barnes would have patted his budget’s head. We would have rolled our eyes and gotten on with the slow hemorrhage of labor.

Except the next morning, a new post appeared. Another four A.M. caption—Harbor’s still awake, Chicago’s eyes open, and so am I. Barnes saw it. In the weekly team meeting he lifted his chin toward the ceiling, the way men do when trying to be extra-sincere.

“You all see Kelsey’s perspective? That’s a young person who finds joy. That’s what I want from this team: positivity, gratitude.”

I wondered whether “gratitude” now meant “Please rebrand hardship into content so that I feel better about asking you to endure it.”

After the meeting I went to refill my water bottle and found Carmen from HR leaning against the counter, stirring tea she didn’t seem ready to drink. “You okay?” she asked, which in Carmen-speak meant, I see you moving your jaw like you’re chewing glass.

“I will be,” I said. “Eventually.”

Carmen smiled in that HR way—soft focus. “I love positivity. I just don’t love it when it’s required.” She dropped her tea bag into the trash like a verdict.

Back at my desk, my Slack pings multiplied. Hannah sent a single skull emoji. Ty sent, Is there a word in Icelandic for when somebody else is praised using a fictional version of your life?

“Probably,” I typed. “It’s probably twenty syllables long and tastes like gravel.”

“Let’s just survive,” Ty wrote, because if you can’t be poetic, you can at least be honest.

And that’s how we met the beginning of the end: tired, caffeinated, faintly nauseated by mango pudding mythology and the conversion of suffering to hashtags.

I didn’t know that in a few weeks I’d stand in the fluorescent scream of our corridor watching Kelsey get hauled by a handful of hair. I didn’t know there would be a number—thirty-two—that would cling to her like bubblegum on a heel. I didn’t know I’d weaponize a rumor to set a trapdoor, and that it would work, and that the sensation of landing a blow would taste like tinfoil.

But we were on our way there. Hunger is a map. Everyone is always following it.

Part III:

The money talk arrived wrapped in a taffy-colored “hey bestie” voice. It was the last Wednesday of the month, payday. HR had sent its usual boilerplate about “confidential compensation practices,” which always read like a promise and a threat braided together. By ten, you could feel the quiet rustles of curiosity: phones unlocked under desks, Excel tabs calculating after taxes—the arithmetic of dignity.

Kelsey did her rounds like a Girl Scout selling cookies nobody ordered. “Hannah,” she sing-songed, “how much do you make? I’m just trying to, like, set goals.”

Hannah’s eyebrows performed a ballet. “We’re not supposed to share salary information,” she said, the Manual living comfortably in her mouth.

Kelsey pushed her lower lip forward in a way that was physically impressive. You could have balanced a spoon there. “Come onnnn,” she whined softly. “Tell me.”

“No,” Hannah said, and returned to her code like it was a door she could shut.

Kelsey turned to Ty. “Ty, how much?”

“Enough to Google it when you’re not looking,” he said lightly, which was a graceful way to back out of a trap.

She zipped herself from cube to cube, harvesting no numbers. When she finally reached me, her eyes were bright like she’d been crying and had decided to rename it “dewy.”

“Lena,” she breathed, “what’s your salary?”

“What’s yours?” I asked, because sometimes a mirror is all the weapon you need.

“Not a ton,” she said. “I mean, obviously I’m not as established as you. You’ve got, like, sass. And assets.” She let the word “assets” sit there, hoping I’d giggle and forgive.

“Not a ton,” I echoed. “Me either.”

She tried again, smile sharpened. “Is it, like, over fifty? Over sixty? Over a hundred? Kidding!” She wasn’t kidding.

“Why do you want to know?” I asked.

“I want to, like, benchmark,” she said, a corporate word she wore like a borrowed blazer.

I thought of the Manual, yes, but also of how fast our office metabolized gossip. Information was either food or sickness. Kelsey didn’t understand the contagion she was inviting. Or maybe she did, and this was the point.

“Okay,” I said, and watched her whole body brighten with the achievement of having broken me. “I’ll tell you mine if you tell me yours.”

“Deal!” she said instantly. She took my hand and squeezed it like she was punctuating an oath. “I promise.”

I leaned in because I am, despite my better self, occasionally theatrical. I lowered my voice until it was a ribbon only she could hold. “Thirty-seven,” I whispered. “And some change.”

Her eyes became saucers. “Thirty-seven what?”

“Thousand,” I said, and kept my face as smooth as a legal pad. “Started at thirty-five. Two-hundred increase each year. Plus quarterly stipend of eight hundred for travel and training. And end-of-year bonus—small.”

She inhaled and exhaled in little hiccups of processing. The math dial spun behind her eyes. “Wow,” she said. “I thought— I mean. Wow.” She nodded as if I had confessed a felony. “You deserve more.”

“Thanks,” I said, and the lie tasted like mango.

“And yours?” I asked, because it was the rule we had made together with our hands.

Kelsey smiled like a road flare and stood up. “Gotta pee!” she sang, and walked away.

I stared at the spot where she’d been. Then I opened our team chat and typed, If I say a number and the number is not the number, am I a monster?

Ty replied with the speed of a life vest. You’re a scholar.

Hannah: You’re a citizen.

I felt an unkind satisfaction curl up at my feet like a cat.

By afternoon, a rumor had found me before I found it. “Heard you’re making thirty-seven,” said Shannon from Sales Support, her voice pitched to signal innocence. “That seems low for Chicago.”

I took a sip of water. “Does it?” I asked, too neutral.

“Kelsey said,” Shannon offered. I pictured Kelsey strolling through the office feeling victorious, the number like a trophy above her head. Three hours later, Ben from next door stuck his head into our aisle. “Kelsey said she’s on par with you,” he said. “She was…proud? Is that the word?”

I looked at Ty. He looked at me. “It’s not not the word,” he said.

On the train home, I tried to audit my conscience. I had lied, yes. But I had lied to protect a policy Kelsey had been aggressively endangering. For that matter, I had lied because I was tired of our office being a stage for one person’s myth-making. I wanted to pull one string in her embroidery to see whether anything unraveled. This was pettiness braided with principle. My chest felt tight. I told myself it was the HVAC.

Two days later, a new weather front: Kelsey approached my desk like a storm wearing glitter. “Why did you lie?” she demanded. Tears stood in her eyes, fat as punctuation. “Why did you tell me you make thirty-seven when you make eighty?”

It was a gamble to deny. The heat in her face told me there was no point. “Who told you what I make?” I asked, calm as a school nurse. You learn to perform calm when you’re confronted by a person whose tears feel weapon-adjacent.

“My mentor,” she said, then flinched, realizing she’d said too much. “Why does it matter?”

“You were asking wages in a way that breaks policy,” I said, because sometimes HR is the only language people hear. “I was protecting myself.”

“You made me look stupid,” she said, stamping one foot like a cartoon child. People were looking, which I hated; anger is best practiced in private.

“You made you look stupid,” I said, and saw the flinch travel through her like a whipwind. “You went around bragging about a number that wasn’t yours. Also, you don’t get to demand information from everyone and refuse it yourself. That’s not curiosity; that’s extraction.”

She made a tiny noise—an injured balloon. “You’re cruel,” she whispered. “You’re a bully.”

I thought of the word bully printed on a poster in a middle school hallway and felt a strange detachment, like someone had pressed pause on the scene and I was floating above my own head.

“Go to HR,” I said. “Report me. Tell them I refused to disclose pay to a coworker who begged me for it.” I kept my voice as unemotional as unopened mail. “Tell them your mentor violated confidentiality too. Let’s all have an honest day.”

She stared at me then, really stared, and I watched the world inside her rearrange into a shape that had no place for me at its center. “I hate you,” she said softly, but loudly enough for the office to hear. “You think you’re so special. You’re just—” She groped briefly for the texturally satisfying insult and came up empty. “Mean.”

She turned on her heel and walked directly into the ficus by the windows. The leaves shook like applause. Ty pretended to cough. Hannah stared down at her keyboard as if it contained a safer world.

Two days later, the memo went up on the internal site: a reminder about compensation confidentiality. Two names were not written, but they were seen. Kelsey started coming in later. She kept her chin higher. She posted about heroines overcoming “haters.” She took photos with captions that implied devotions and devotions that implied transactions.

Somewhere in this, a new category of man entered the stage: Ben, who sat a row over and had a clean haircut and unthreatening sneakers, confessed to Ty that he had once bought Kelsey a bagel on his way in. She had smiled, said thank you with a curtsy, and never opened her Venmo app.

“It’s fine,” Ben said quickly, flushing. “It was twelve bucks.”

“That’s not ‘fine,’” Ty said. “That’s a unit of currency called Never Again.”

Over the next week, we witnessed an escalation. Kelsey—someone who had practiced helplessness like it was a martial art—began asking men for small favors as if this were a perfectly transparent transaction. Could you pick up my breakfast? Could you carry my packages? Could you put this on the high shelf? Could you, could you, could you. The asks were small enough to be tolerable and constant enough to be unsettling.

One morning, during the lull between the first coffee and the second, Anya from Sales snapped. Kelsey had just asked Ty to “pretty please print and collate” a client packet that had been hers to build. Anya stood up with her jaw set. “Hey,” she said to Kelsey across the aisle, voice steady. “When are you paying back T.J. for the breakfasts?”

Kelsey blinked, wounded. “I did,” she said.

“No,” Anya said. “You smiled.”

“I said, ‘Thank you,’” Kelsey said. “That’s what you do when someone does something kind.”

“You also pay them,” Anya said. “Or you Venmo. Or you don’t ask.”

Kelsey’s face went hard as candy. “Men like to do things for me,” she said, too loud. “It makes them feel useful. I don’t owe anyone anything for being kind to me.”

There it was: the thesis statement. Currency had changed hands in her mind. The smile was the payment. The man was the grateful recipient.

The office performed its version of a collective breath-hold. I felt like I was standing in a gym with a rope stretched between us and the ground: the moment before a fall.

That afternoon someone (not me, though my hands stayed far from clean) sent Barnes a screenshot of Kelsey’s post about her “four a.m. grind mindset.” He began to use her as a specimen of Attitude during his little sermons. “We need more Kelseys,” he said in one meeting, at which Kelsey beamed, and I learned that I can in fact grind my teeth without moving my mouth.

By the time the rumor of hand-holding came, we were ripe for scandal. Rumors, too, have an appetite. They prefer to eat where the kitchen is already warm.

I wish I could tell you I didn’t help stir the pot. I wish I could tell you, when Anya whispered that she saw Barnes and Kelsey walking hand-in-hand by the fountain in the plaza on Saturday, that I asked for proof and then ignored it.

Instead, I said, “You sure?” and she said, “I took a picture.”

“Jesus,” Ty breathed. “We’re living in a cable drama.”

“More like a YouTube web series,” Hannah said, dry as winter skin. But she leaned in too. We all did.

In the photograph—it was grainy, but nothing needs to be 4K to satisfy—their hands were a clasp, not an accident. Barnes’s head was inclined. Kelsey’s smile was a woman who could not wait to write her caption.

If this were a decent world, the next part wouldn’t happen.

But this is an office, not a decent world.

And the next part happened.

Part IV:

The bagel cost twelve dollars. It was from MorningLore, the artisanal place where every ingredient has a backstory and every bagel comes with an identity crisis. Lox, capers, heirloom tomato slices as thin as a promise, a smear of dill spread whipped to heaven. L.J.—quiet, gentle, a designer who wore soft sneakers and brought his lunch in Tupperware like a man who still believed in leftovers—brought it back for Kelsey because she had asked and because he was, in his words, “passing by anyway.”

I didn’t know any of this until later, when the calendar flipped to a day when patience was more expensive than bagels. What happened next unfolded like a group text that had become three-dimensional.

At 11:52 A.M., Kelsey posted a grid of photos on Instagram: the bagel on her desk, the bagel in her hands, the bagel half-eaten with a lipstick mark on a paper cup. The caption: He heard me say “bagel” once and showed up with the perfect one. Chicago men take care of me too well.

The comments threw confetti. You deserve it. Princess treatment only. He totally likes you. Kelsey replied to that last one: lol doubt it 😳 I’m unlovable, but it’s fun to pretend someone’s thinking of me.

At 12:04 P.M., Anya walked over to L.J.’s desk. I could hear her voice carry, crisp as celery. “Did she pay you back?”

L.J. blushed so fiercely it felt like a violation to see it. “I, uh, no,” he said. “It felt weird to ask.”

“Huh,” Anya said, and returned to her seat like a tide reversing.

At 12:21 P.M., Anya called down the aisle, “Hey, Kelsey? When are you paying L.J. back for the bagels?” She did not use a teasing tone. She used a teacher’s voice: a paragraph of context held in reserve.

Kelsey froze, halfway through arranging a strand of hair for a selfie. Her hand stilled like a bird that suddenly remembered it was a statue. “Excuse me?” she said, brighter, louder than necessary.

“You heard me,” Anya said. “You owe him for the breakfasts.”

“I don’t,” Kelsey said. “He offered.”

“He didn’t,” L.J. murmured, mortified by the attention, and yet, dear man, telling the truth.

Kelsey’s face had a new hardness. “Men like to do things for me,” she said again, doubling down on the earlier thesis, this time with adrenaline and witnesses. “They feel appreciated.”

“Appreciation doesn’t pay rent,” Anya said, too fast and too true.

“It’s literally a bagel,” Kelsey snapped. “What, twelve bucks?”

“Per day,” Anya said. “For the past week.”

Kelsey’s lips quivered. “Are you policing my generosity?” she asked, as if generosity were the thing under review.

“I’m asking you to pay your debts,” Anya said.

And I don’t know what mix of humiliation and conviction detonated there, but Kelsey pivoted like a dancer and marched down the alley of cubicles to L.J., who had sat up straighter as if an exam had materialized. Kelsey stood over him, her hands on her hips in a stance I recognized from grade-school desks and beauty-influencer tutorials alike.

“You’ve been telling people I owe you money?” she demanded.

“I mentioned it,” he said, voice small. “When asked.”

Kelsey produced a laugh that was more like a bark. “For twelve dollars,” she said. “That’s what my smile is worth?”

Oh, we all leaned in then, not physically but at a soul level, our curiosity unbeautiful and specific. There are moments in an office when the shared air tastes like electricity, and it’s not creative energy—it’s the knowledge that something is breaking and we want to know whether it will heal or scar.

“Venmo me,” L.J. said softly, surprising us all. “Or don’t. Just don’t ask me to buy you breakfast again.”

“You like me,” Kelsey said triumphantly, which was such a mistake that I felt a shadow of empathy even as my jaw fell open.

“I have a girlfriend,” he said, and a horrible stillness fell over the aisle. “And I don’t like people treating me like a delivery app.”

Something inside Kelsey reared then, a frightened, angry horse. She spotted Ben three cubes down—the poor man who had once bought the original bagel. “Fine,” she hissed. “Ben, you can do it. You can bring me breakfast tomorrow.” It came out as a command.

Ben recoiled as if she’d slapped him. “No,” he said.

The room became a pinata; everybody expected candy and got dread. Kelsey’s eyes went glossy, then feral. “You’re all jealous,” she said. “You’re all old and tired and you hate that I’m young and that men are sweet to me. You hate me because I’m a reminder.” Her voice shook.

“Of what?” Hannah asked, so quietly the question almost felt kind.

Kelsey looked like she’d been asked to explain gravity. “That life can be cute,” she said. “That life can be easy if you let it.”

“Life can’t,” Hannah said. “People can.”

The silence that followed was stunned not by the poetry of it, but by the plainness. Then the room exhaled in whispers. Kelsey slammed her drawer shut and left for lunch at a clip that said she needed air or applause or both.

At 3:17 P.M., a new Instagram appeared: a soft-focus selfie of Kelsey in the bathroom, eyes glossy, captioned: Even angels get tired. Even good girls get misunderstood. I’m not everyone’s cup of tea. That’s okay—some people can’t handle sweetness. Three dozen heart emojis.

We joked later that she was a religion of one called Mango Pudding. But right then the office felt like a church that had lost its hymn.

The fight would have become a story we told later, except I am, regrettably, the person I am. And I was angry, and I had a tool I’d never used, and I used it.

Barnes had a wife named Noreen. She came by the office twice a month with their toddler grandson when she had lunch downtown—there was a daycare near our building with glass walls and big wooden blocks that looked carved from optimism. Noreen was a tough woman with a willingness to apply that toughness to Barnes, which is a kindness some men require and resent.

Noreen was friends with Carmen, HR’s celestial body, and small-town truths like that hold big-city power. I did not text Carmen. I am not suicidal. I chatted with Dana—accounts payable, gossip distribution center—and let slip, “We saw a pic of Barnes and Kelsey holding hands by the plaza fountain.” I said it like a jacket I’d draped over a chair by accident, not like a match tossed in a dry room.

Dana did not blink. “Oh honey,” she said, “don’t bleed where sharks can smell,” which I think was her way of saying, good luck. Except by the next afternoon, Noreen arrived with her grandson and an expression carved from basalt.

We all felt it—the old, feral thrill that something we should not witness was walking toward us. The doors whispered open in that lax corporate shuffle. Noreen paused to say hello to Carmen and then marched down the aisle toward Barnes’s office, her grandson on her hip like a tiny moral witness.

She passed my cube and I pretended to look at my screen. The grandson—two, maybe—looked at me with the blank mercy of children who don’t yet know the names of our disasters.

Noreen reached Barnes’s office and pushed the door. It was locked. The lock was unusual—Barnes used it for private client calls and perhaps other private things. Noreen knocked. No one answered. She kicked the door. Then she kicked it again. The grandson laughed, delighted by this new game.

A beat later, the door opened. Barnes stood there, shirt half untucked, his face a bowl of skim milk. Behind him, Kelsey hovered, cheeks mottled with either shame or adrenaline or dramatic instinct, which on her face looked the same.

“You,” Noreen said to Kelsey with the coldness of a clear sky right after a blizzard, “outside.”

“I’m at work,” Kelsey said, as if this were a courtroom.

“Not anymore,” Noreen said.

And then it happened. There was hair and hand and force, and there was Kelsey—meek, wailing, fighting to maintain her costume. There were the rest of us, stuck between the instinct to intervene and the wisdom not to. We chose wisdom, by which I mean we did nothing.

Kelsey shouted, “She’s crazy!” Barnes said, “Noreen, please,” and Noreen said, “Walk.” Carmen, to her everlasting credit, arrived with command in her posture and extracted the grandson, who had begun to cry.

“This is HR,” Carmen announced, palms up. “Let’s take this to a private room.”

“Perfect,” Noreen said, and marched in that direction, Kelsey in tow, Barnes trotting behind with his hands up like a man surrendering to a movie scene he’d never auditioned for.

We stood, and sat, and stood again, and finally sat. Ty whispered, “I think my grandmother is stronger,” and I wanted to laugh and cry and apologize to the universe for our species.

An hour later, the meeting room emptied. Kelsey did not reappear. Barnes came out, gray with the aftermath, and went into his office. Carmen sent an email: “Please join me in the conference room for a brief meeting at 4:30.” We gathered like a class called to assembly.

Carmen stood at the head of the table. Her mouth was tight, her eyes were not unkind. “We are a workplace,” she said. “We are not a soap opera. There will be disciplinary action. The details are private.” She looked at me then, not at me specifically but in my region, as if my guilt had a scent. “Our social media policies are also real. That’s all for today.”

Afterward, Ty said, “We are the bad kind of interesting.”

Hannah said, “I need to stop enjoying this.”

I said nothing because my stomach had folded into sharp shapes. I had wanted something to happen; something had happened; what did I think justice would feel like?

The next morning, an all-hands ping: Barnes was demoted to individual contributor “effective immediately.” Carmen’s message included words like “realignment” and “opportunities for growth.” The subtext wasn’t sub: he’d been chewed up by a machine he’d thought he could outrun.

An hour later, Kelsey’s access card didn’t work. She stood at the door, tugging, looking over her shoulder for a camera. Carmen met her there with a manila envelope and a neutrality that belonged in a museum. Kelsey cried, accepted the envelope like a diploma, and walked out into a city that looked exactly the same as it had yesterday.

Nobody clapped. It wasn’t a victory. It was a weather change.

Part V:

When the new manager arrived, he brought plants. Real ones, not the plastic ferns that collect dust like a second job. His name was Marcus Hale and he’d done two tours at other agencies where he’d been described in LinkedIn recommendations as “unflappable” and “a coach who listens.” He swung by my desk the first morning and said, “Hey, I’m Marcus,” like a normal person, which is a thing I suppose I’d stopped believing in.

He called a meeting and stood at the head of the table without needing to touch his belt. “I read the numbers,” he said. “I read the police report—kidding.” A ripple of too-true laughter. “I’m here to manage work, not drama. Two things matter to me: your workload is fair, and your credit matches your labor. If something is breaking one of those, come see me.”

He didn’t praise positivity or ask us to be grateful. He asked us to be precise.

The first week under Marcus, the office felt like a house after a storm: a little soggy, a little stunned, still standing. Barnes, demoted, started packing his photos into a banker’s box with the melancholy of a sitcom end-credit sequence. He shook hands with people who offered them. He didn’t look at me. I didn’t look at him either. There are ruins we’re not brave enough to tour.

I found myself thinking about Kelsey in quiet loops. I told myself I missed nothing: not the pitched “please”s, not the filtered captions, not the way she turned free desserts into vows. But I missed something I could not name. It wasn’t her, exactly. It was the opportunity to see myself as a person who had not done what I’d done.

On day three of Marcus’s reign, Carmen called me into HR. She closed the door and sat in her usual posture: shoulders squared like a general preparing to be kind.

“You didn’t do anything wrong,” she said, a preamble that made me prepared to feel guilty. “But I know the rumor about the photo got to Noreen.”

“I told Dana,” I said before she asked. “Not to be weaponized. To… I don’t know. To…stupid.”

Carmen’s smile did a small, precise thing. “Dana doesn’t weaponize. She circulates. The difference is subtle and destroys civilizations.”

“I am sorry,” I said, and meant it.

“I know,” Carmen said, and poured me a small glass of water from the carafe she keeps for this kind of scene. “Listen. You can want someone to face consequences without wanting someone to be hurt. That’s a distinction I find useful. And—” she looked at me like she was passing a season of weather— “we all get to choose whether we become the last thing we did.”

“Do we?” I asked, genuinely unsure.

“I do,” Carmen said. “And I work in HR. You’ll be fine.”

I laughed then, not because HR is engrailed with hope but because Carmen has that trick of sending you back to your desk feeling like a person, not an employee who accidentally knocked over a domino line.

Outside the conference room, Ty was leaning against the wall like a character in a music video. “Was that about your soul?” he asked.

“Yes,” I said.

“Good,” he said. “It’s still there.” He grinned. “Lunch?”

We went to a place with banh mi that spread cilantro like rumors. We talked about dumb television, about Ty’s baby, about Hannah’s insistence on auditing her pores. Nobody said Kelsey’s name. Names are talismans; we were giving ours a rest.

In the weeks that followed, the office’s muscles loosened. Our Slack jokes returned to the wholesome meanness of mocking fonts and punning on campaign names. Marcus sliced up the garbage projects and redistributed them according to skill and interest. He did not hand unpaid overtime to the eager. He sent emails that included lines like, “We’ll finish this tomorrow,” and when he said it, he meant it.

It felt like stepping out of a theater at noon and remembering there is a sun.

One morning, waiting for the elevator, I saw Kelsey in the plaza reflected in the brass. It wasn’t her, obviously—just a young woman in a pastel sweater, moving in a hurry. My heart did that small prey-animal hop anyway, the human body’s way of saying, “We remember.”

In the coffee line, the barista who’d watched us all learn our vices over months said, “Hey, sorry about your manager.”

“Which one?” I asked.

He nodded, impressed. “Must be corporate,” he said. “You all always have two.”

I laughed into my sleeve. The barista handed me my latte and scribbled a heart on the lid without meaning anything by it. I took the elevator up with men who smelled like two kinds of cologne and a woman whose tote bag said WOMEN’S WORK IS WORK, which felt like a blessing.

At my desk, a Slack ping: Hannah—lunch?

I typed: Always.

She added: We should talk about Kelsey.

I stared at the message until the letters became shapes. Then I typed, Okay.

At noon, we sat with bowls of pho on paper placemats in the small conference room that smells permanently like printer ink and achievement anxiety. Hannah twirled basil around her chopsticks. “I feel…crappy,” she said. “About enjoying the spectacle. About wanting the blow to land.”

“I know,” I said. “I’ve been carrying around my performance as a small, stupid trophy.”

Hannah’s mouth did its version of a smile: a little tuck at the corner. “I keep thinking about what she believed. The…emotional currency thing.”

“Her smile as Venmo,” I said.

“Yeah,” Hannah said. “It was wrong—but not unknown. Like, we all trade something.”

“Everyone’s tipping jars are different,” I said. “Hers was always out, and empty.”

“Maybe she will be okay,” Hannah said, and it surprised me how much I wanted her to be right.

Two weeks later, Ty sent a link in our private channel: a TikTok of Kelsey in a pink hoodie, explaining “how to reframe workplace adversity.” The ring light sat reflected in her eyes like a new kind of faith. She spoke in the vowels of people who have never fully been told no in a language they understand. She didn’t mention our company. She didn’t mention Barnes. She didn’t mention that the bagel cost twelve dollars. She said, “There are always haters,” and smiled a smile that meant she would never include herself in that category.

I wrote, Well.

Ty wrote, The content economy always finds its saints.

Hannah wrote, And its martyrs.

I minimized the window and returned to my quarterly report. Outside, the city made its sounds—sirens, lunch laughter, a jackhammer auditioning for anger management. Inside, my spreadsheet made its quiet logic. Numbers don’t care who brings you breakfast. They care about where the zeros land.

The new calm didn’t erase everything, of course. Office ghosts stick to carpet fibers. When an intern practiced her “tee-hee” voice to ask Marcus for help with PowerPoint, a bone-deep weariness flooded me. Marcus didn’t indulge her; he taught her the thing and told her to schedule time next week to learn the rest. “I won’t do your work for you,” he said. “I won’t make you do more work than you should, either.” The intern blinked, recalibrated, and sat up straighter. Maybe this is how culture changes: tiny recalibrations, repeated.

Barnes sent a goodbye email full of phrases like “grateful for the journey” and “embracing new challenges.” He did not thank Noreen. He did not apologize to anyone. He stopped by our pod to shake hands. He reached for mine. I gave it. He said, “All the best, Lena,” and I said, “You too,” and the handshake lasted exactly as long as it needed to.

That weekend I took a long walk by the river and bought a mango pudding at a dessert shop because I’m not above symbols. It tasted sweet and faintly ridiculous, like dessert does when you’re thinking too hard. I laughed out loud at myself and the people at the next table gave me a side-eye all Chicagoans are issued at birth.

Back at my apartment, I scrolled through my camera roll, past screenshots and recipes and a photo of Ty’s baby with peas on his face. I did not have a single photo of Kelsey. It felt correct, and it felt lonely.

I opened a blank document and typed, Work is not a family or a battlefield; it is a small town with mandatory attendance. I deleted it and boiled pasta. I stared at the cheap print above my couch that said THIS MUST BE THE PLACE and decided to believe it for the hour.

On Monday, the office felt lighter. Time had done its small work. The plants on Marcus’s windowsill tilted toward whatever patch of light the building allowed. Someone had brought in donuts and written, “Take one, take two, who am I to judge?” on a Post-it like a kindness spelled in sugar.

At ten, Marcus called us into the Bullpen—same sad poster, new weather. “We’ve got a client who loves drama in their brand voice,” he said, “but not in their brand team.” He smiled at his own joke. “We’re going to pitch them simple and clean and human.”

Hannah presented, careful and startling, like a magician who prefers math. Ty cracked two jokes that made the client laugh in real time. I walked them through the targeting model with sentences that felt like I’d sanded them sharp.

After the call, Marcus said, “Great. Also, Lena, nice frame on the KPI slide.”

I said, “Thanks,” and felt the compliment land in a place not braced for pain.

At lunch, I sat with Hannah and Ty by the window—the slice of city we were permitted. A girl in a pastel sweater crossed the plaza. She looked up at the office tower and smiled, and for a second I saw Kelsey’s outline in her swing. I hoped the girl had money for her own bagel. I hoped no one told her that smiling was a sufficient currency. I hoped we were kinder than we had been, even if we’d be kinder mostly to ourselves.

Hannah raised her plastic fork like a toast. “To mango pudding,” she said.

“To the gospel of mango pudding,” Ty amended.

“To the human habit of making everything a story,” I said, and we clinked forks like celebrants at a very low-budget wedding.

Sometimes, in the afternoons, I still open Instagram and scroll through Kelsey’s feed, the new one with the coaching. She posts reels about “boundaries” and “believing in your inner child’s boss.” She sings her mantras to a ring-light halo. People comment: You saved me today. Needed this. How do you stay so sweet? She replies with hearts and “angel”s and you got this in a font with a tail.

I don’t comment. I let the algorithm do its creep. I close the app. I open my work. I let the very unspiritual satisfaction of finishing something settle over me like the good kind of quiet.

When I go downstairs for coffee, the barista asks, “Everything good upstairs?” and I say, “Good enough.” He draws a heart on my lid. I tip him cash.

On the way back up, I pass Carmen in the lobby. She’s carrying a stack of folders and an iced tea and the patience of ten lifetimes. I fall into step with her for half a minute. “How’s your soul?” she asks, teasing.

“Still here,” I say.

“Good,” she says. “Bring it to work. Leave it intact.”

In the elevator, Ty texts a photo of his son covered in peas with the caption: world’s worst pesto. I laugh before I can help it. Hannah replies with a skull and a basil leaf. Marcus reacts with a thumbs-up, which should be lame but isn’t. The doors open onto the 28th floor, our finite city, our small town. We step out.

There is work to be done.

There will be more desserts, more flights, more rumors, more managers with belt habits. There will be mango pudding and there will be a gospel written about it by someone for whom the world demands narrative the way the body demands salt. There will be girls in pastel sweaters and women with ring lights and men who think red-eyes are the same as heroism.

There will be me, trying, failing, trying again to sit where I sit, to do what I do, to measure my hunger against a pantry and still come home to make dinner without needing to turn myself into a sermon.

That night, in my apartment, I write KELSEY at the top of a page and then cross it out, because names are not the point. I write, A woman believed her smile was legal tender. I write, A manager mistook hunger for gratitude. I write, An office remembered how to be a place.

I close the notebook and put it on the windowsill next to the basil that refuses to die. Out on the river, a party boat passes—its own small sermon on leisure. Someone takes a photo. Someone else becomes a caption.

The plants in Marcus’s office will lean toward light even when the blinds are half-closed. That’s what plants do. I like to think people can do it too.

In the morning, there will be coffee, and the Slack, and the small, unlikely mercy of work done well. And if someday a dessert arrives at the end of a team meal—the little glass dish, the spoon—we will learn to say: Thank you. For everyone.

We will eat the pudding without turning it into a vow. We will let the dessert be dessert. We will go home.

And maybe that is the ending the story wanted all along: not a bang or a blame, but the soft, stubborn continuity of adults doing their jobs, learning to want less from one another’s fantasies and more from one another’s fairness. Maybe the American ending isn’t heroism—it’s policy and mercy finally agreeing to share a table.

“See you tomorrow,” Ty says on our way out, bag with baby snacks slung like hope.

“See you,” Hannah adds, already pulling up a tutorial for a new SQL trick because that is her kind of prayer.

“See you,” I say, and mean it.

Outside, Chicago tips its face toward evening, unbothered by our small dramas, swollen with the big ones. Somewhere, a woman in a pink hoodie goes live on TikTok. Somewhere, a wife looks at her husband and chooses, again, to practice her toughness as love. Somewhere, someone holds a door for someone who isn’t thinking about doors at all.

I walk into the wind. It does not ask me for a caption. It lets me be carried the old-fashioned way: by feet, by habit, by a body that knows its own weight and asks nobody else to fund it. I think of mango pudding. I think of plants. I think of elevators and copies and stock photos of team-building. I think of money that pays bills and kindness that doesn’t stand in for it.

I go home. I make pasta. I call my sister. I wash my hands twice because the day is still on them.

This is the story. This is its end.

And tomorrow, the work begins again.

Part VI:

Spring came to Chicago in its usual reluctant way, like a favor the weather was doing for somebody’s aunt. The river turned a color that wanted to be green and the parks grew a fuzz of optimism. By then we’d had six months with Marcus. The plants on his sill had graduated from “rescue mission” to “thriving.” We were, too.

Ty’s son could say “bagel” (which felt like a cosmic prank). Hannah had given a lunchtime brown-bag talk on window functions in SQL that half the sales team attended just to sit in a room where competence felt like air conditioning. I’d been asked to lead a client workshop in Minneapolis and Marcus, bless him, booked daytime flights and an actual per diem. He also handed me a printed one-sheet titled “Boundaries Are Productivity” that he’d made himself, and we both laughed at how corny it was before admitting it helped.

We don’t get happily-ever-afters at work. What you get is “for now” and sometimes the “for now” is generous.

On a Thursday, Carmen forwarded an invite from a professional association: WOMEN IN DIGITAL: SPRING SYMPOSIUM. I pictured a ballroom of lanyards and sparkling water and panels with names like “Rising Strong” and “Leaning Forward Without Falling on Your Face.” Carmen wrote, Go make us look like we know what we’re doing. I said yes because saying yes to public growth felt like a way to sand down the memory of the mess we’d fossilized.

The symposium was at a hotel that had perfected the art of being everywhere and nowhere. The carpet had an anxious pattern, the air a good suit’s quiet. The keynote speaker had a TEDx cadence, and the sponsors’ booths competed to be the most futuristic shade of teal. I collected a tote, two pens, one notebook I’d actually use, and a free coffee in a cup that said SHE-EO in a font designed to irritate me.

By the second breakout, I was ready to slip away and text Ty a photo of the world’s most motivational cookie. I turned a corner and nearly collided with a pink hoodie.

Kelsey.

It took me a second, the way recognition sometimes arrives in pieces—a chin, a particular brightness in the eyes, a way shoulders announce themselves. She had traded the cardigan daisies for a soft athleisure aesthetic. The hoodie’s drawstrings had gold caps. Around her neck was a lanyard that identified her as a “Content Strategist & Creator.” Her name was printed clean across a square: KELSEY QUINN. The “Quinn” felt like armor.

She saw me in the same frame. A visible flinch—then a composure pasted so expertly I almost admired it. “Lena,” she said, voice pitched careful. “Hi.”

I could’ve turned heel. I could’ve pretended to be on a call. But avoidance is a shape that hardens inside you. I was tired of calcifying.

“Hey, Kelsey,” I said. “How’s it going?”

A lifetime passed in the space between politeness and truth. She chose a hybrid. “Busy,” she said. “Building stuff. You know.”

I nodded. “We’ve been good. New manager. Less…soap opera.”

Her eyes flicked, a brief spark of hurt or annoyance—I couldn’t tell which. “I saw,” she said. “On LinkedIn. Marcus posted about plant therapy,” she added, and almost smiled.

We stood in the kind of silence you have to shovel through to get to anything worth saying. Around us flowed an entire economy of ambition—the swish of blazers, the clatter of platform sandals, laughter pitched like networking. A session was starting called “Your Story As Strategy.” The irony wasn’t lost on either of us.

“Do you have time for five minutes?” she asked. “I—I actually reached out to Carmen to get your number, then chickened out.”

“Five minutes,” I said. “Public place.” I gestured to a lobby alcove populated by armchairs and a plant that looked like it was pretending not to listen.

We sat. She tucked her hair behind her ear in a move I’d watched a hundred times, and for the first time, it didn’t trigger anything old in me except a small filmstrip of memory. She held a metal water bottle with a sticker that said “Boundaries Babe.” The younger version of me would’ve rolled her eyes. The current one took a breath and waited.

“I’m not here to, like, relitigate,” she said quickly. “I know what happened, happened. I just… wanted to say a thing I should’ve said sooner. Maybe it’s more for me than for you. But here it is: I was living like everything was content. And people aren’t content.”

I blinked. People aren’t content. The sentence was both bumper-sticker and repentance. “That’s…not nothing,” I said, careful not to come across like a parole board.

She nodded. “After I left, I went to work for a startup that wanted me to run social. They paid garbage but I could set my hours and film at my desk and nobody told me not to call myself a brand.” She smiled without sweetness. “It failed in three months. The founder moved to Austin to become a crypto monk.”

I coughed a laugh. “Classic.”

“Then I freelanced,” she said. “Then I did the TikTok coach thing you probably saw. It was…easy money and dirty somehow? Like I could feel the transaction under my skin. I was selling takes on pain I hadn’t paid for.”

We both sat with that sentence.

“I wanted everything to be cute,” she said, softer. “If it was cute, it was survivable. If it was content, it was currency. The mango pudding, the milk tea, the flights. I thought I was paying with sweetness and getting, like, stability back.”

“You were paying with denial,” I said before I could legal-pad my mouth. “And invoicing other people.”

She winced, nodded. “There’s a therapist involved now,” she said with an attempt at lightness. “She’s thirty, has bangs, and charges in blocks that make me feel like a timeshare. But she keeps asking me what I think the world owes me and I keep wanting to say ‘a good angle.’ And then I cry for forty-seven minutes.”

We looked at the plant. It looked back with plant neutrality.

“I’m sorry,” she said suddenly, all at once. “About a pile of things. The salary mess. The way I turned you into a villain in my little movies. The fact that I treated L.J. and Ben like couriers. The fact that I let Barnes—” She stopped, recalibrated. “I liked being chosen. That’s all I’ll say. It made me feel like the story I told about myself wasn’t ridiculous.”

I swallowed. Anger is heavy when you’ve carried it past its usefulness. I watched it sit there between us like luggage I could choose to keep dragging or not. “I did a thing I’m not proud of,” I said. “The rumor. Noreen.”

She nodded. “I figured. I was so busy narrating I didn’t notice how many people were watching with the sound off.”

We sat again inside the lobby hum. After a while she said, “I work at Anchor & Antler now. Content strategy. Real job. Health insurance. A boss who hates Instagram.” She smiled, and for once the smile felt like something used to talk, not to buy.

“I’m glad,” I said, and realized I meant it. “Marcus says he’s allergic to ‘personal brand.’ He breaks out in policy.”

“I could use that allergy,” she said. “My therapist would say that’s a boundary in hives.”

We both laughed, not because it was that funny, but because laughter is sometimes a way to leave a room without standing up.

In the pause that followed, an event volunteer in a blazer identical to mine asked whether we wanted headshots at the pop-up photo booth. We declined in the same breath, which felt briefly like being on a team again.

“I brought you something,” Kelsey said abruptly, and pulled from her tote a small, neat box from a bakery I recognized—one of those places that shipped joy in biodegradable packaging. She held it out. “No strings, no captions. Mango panna cotta. They had it as a special. I thought it was funny and then I thought it might be a peace offering. Or a joke if you needed it to be.”

It was a risk. I appreciated the attempt to control the symbol less than the attempt to let the symbol simply be a dessert again. I took the box. “Thank you,” I said. “I’m going to eat it without assigning it a moral.”

“High bar,” she said.

We stood. The session ushers were shepherding everyone to the ballroom with a kindness that had time limits. Kelsey looked like she wanted to hug me and then wisely didn’t.

“One more thing,” she said instead. “If a girl fresh out of school shows up in your office wearing cartoon daisies and a smile that makes you itch, will you… I don’t know… tell her to open Venmo? Or send her to HR before the world does?”

“I’ll try,” I said. “We’ve got a better manager now. It helps.”

She nodded. “It always starts there.” She glanced at the ceiling like it might declare a day of rest. “Bye, Lena.”

“Bye, Kelsey,” I said. “Be well.”

She turned and drifted back into the river of women with lanyards. For a second, her hoodie’s pink burned like a flare and then the current took the color and it became just another shade in a soft crowd.

I stepped outside. The air had warmed to a temperature that didn’t make me think of contracts. I sat on a bench and opened the box. The panna cotta trembled like a tiny planet that knew gravity was a suggestion. I ate it. It was exactly what it was: sweet, silly, brief.

When I got home, I told Ty and Hannah about the symposium, about panels with names like “Own Your Arc,” about the free pens, about running into Kelsey. I didn’t make a meal out of it. I said: she apologized. I said: I did, too. Hannah typed, Growth: the boring kind, the real kind. Ty sent a GIF of a plant unfurling and then a photo of his son asleep with a slice of bread on his chest like a napkin of fate.

Monday returned in its steady shoes. Marcus asked me to mentor the incoming intern cohort. “Not their mom, not their therapist, not their hype squad,” he said. “Teach them how to send a decent email and how to say no without setting the building on fire.”

I said yes. The first cohort arrived with their backpacks and their curated casual. One girl wore a sweater with tiny rabbits around the cuffs. She had a voice pitched for pleading. She tried it out on me the second afternoon. “Could you just—like—do the pivot part for me pretty please? I’m, like, bad at numbers.”

I smiled. “Nope. I’ll show you how. Then you’ll do it.”

She blinked, recalibrated. “Okay,” she said. Her okay contained a hundred unlearned songs and one new bar of sheet music.

We sat and wrestled the data. When she got it, she made a tiny sound of victory that wasn’t a whimper at all. It was competence clearing its throat.

At lunch, Hannah swung by, tossed me a granola bar, and said, “Your intern wrote a thank-you email with bullet points. You’re a wizard.”

“I’m a citizen,” I said, and we both laughed.

Sometimes, on the train home, I see a ring light glowing in an apartment window and think of Kelsey coaching someone through a sentence that will make them feel like their life is a film festival. Sometimes I hope she’s telling them this: make your life a place you live, not a place you film. Sometimes I just hope she’s charging fairly and paying whoever brings the bagels.

At night I open my notebook and write small true things without captions. Good managers are boring in the way good bridges are boring. Sugar is not salary. Boundaries do not make you unkind; they let you use your kindness where it counts. I close the notebook and do the most unfashionable thing I know: I go to sleep on time.

Spring leans toward summer. The office windows pretend to open. The elevators continue their endless mime of ascent. We have another team dinner—Marcus insists on family-style dumplings and says yes to dessert not because there’s a metaphor in it but because sugar with colleagues is a harmless sacrament when everyone goes home afterward and pays their own utilities.

The server brings a tray of sesame balls and a plate of mango pudding, not in glass dishes but in little ceramic cups shaped like flowers. We pass them around. Ty reaches for one and grins at me—no wink, no subtext, just a man happy to eat something yellow. Hannah takes two and declares this is the only part of office culture she’s interested in scaling. Marcus pretends to fight us for the check and then actually lets the company pay because the company said it would.

We eat the pudding. We talk about nothing urgent. We go home.

If there is a gospel here after all this time, it’s not mango pudding. It’s this: some stories end, and then you get to make other ones where people are not props and desserts are not declarations and work is not a moral but a task shared between adults. It is smaller, and it is enough.

On my walk back along the river, the wind presses the city against my skin and makes no promises. I don’t need any. The lights shiver on the water. Someone behind me laughs without a mic. My phone stays in my pocket. I keep walking.

News

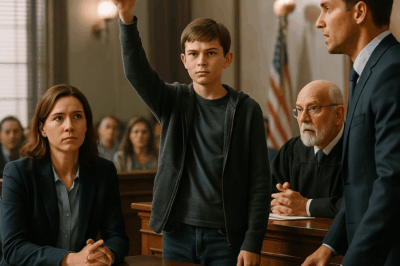

My Ex Told the Judge Our Son Wanted to Live With Him. Then My Son Pulled Out His Phone… CH2

Part I The courtroom was quiet, but not the kind of quiet that helps. It was the kind that made…

My Son Broke a Bully’s Arm. His Father Came For Me, Then I Said The One Word That Made Him Flee… CH2

Part I On Maple Street, the morning always started with sunlight and simple math. Two eggs, over easy. One travel…

Cheating Wife Walked Into The Kitchen & Froze When She Saw Me,”You Didn’t Leave?”… CH2

Part I The saw kicked back and bit deep into my palm, splitting skin like wet paper. A scarlet V…

My Parents Hid My Tumor, Calling It “Drama”—Then the Surgeon’s Discovery Stunned Everyone… CH2

Part I The lump started like a bad idea: small, ignorable, something you tell yourself you’ll “deal with later.” I…

My Dad Left Me On The Emergency Table Because My Sister Had A Meltdown – I’ll Never Forget This… CH2

Part I Antiseptic burns in a way that feels righteous. It bites the skin as if scolding flesh for failing…

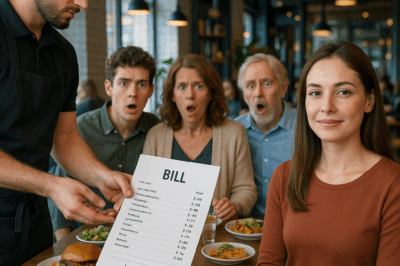

‘RACHEL, THIS TABLE IS FOR FAMILY. GO FIND A SPOT OUTSIDE.’ MY COUSIN LAUGHED. THEN THE WAITER DROPP… CH2

Part I The leather folder landed in front of me like a trap snapping shut. I didn’t flinch. I didn’t…

End of content

No more pages to load