Part I

I didn’t hold the baby.

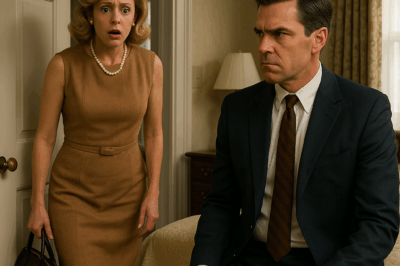

I didn’t kiss my wife on the forehead, or tremble, or weep the way every video tells you you’re supposed to do when a brand-new life is crowning in bright hospital light. I stood there with my hands in my pockets, eyes cold as an empty winter parking lot, and dropped a line heavy enough to crack the tile.

“We’ll fill it out after the DNA test results come back.”

Every face in the room turned toward me like I’d just pulled a pin with my teeth and rolled a grenade across the polished floor.

Amanda—my wife—was propped up against pillows, cheeks pale and shining, a pink-capped newborn tucked to her chest like something holy. My mother, Evelyn, stood to her left, a tall woman who could fillet a lie with a glance. Amanda’s mother, Carol, stood to her right, one palm hovering over Amanda’s hair like a blessing that didn’t know where to land.

The nurse froze, clipboard halfway between her and me. She had the battle-hardened calm of a woman who has seen fainting fathers, panicked grandmothers, teenage cousins Facebook-Live a birth. Still, she blinked. “Mr. Walker,” she said carefully, “we usually complete the certificate—”

“We’ll complete it,” I repeated, “after the results.”

Amanda’s head snapped up too fast. The baby startled, pin-mouth opening, a high kitten squeak. “What the hell are you talking about, Jason?” she whispered. Her voice shook so hard the words clinked together.

Carol gasped. “Not now,” she said, a plea, a scold, a lightning rod all at once. “Jason, not now. She just gave birth. You could push her into postpartum depression with… with this.”

Evelyn’s jaw flexed, but her voice was level. “Jason Walker,” she said, mother using full name, “I did not raise you to humiliate a woman in labor.”

I let it wash over me. I had rehearsed every possible version of this moment—the screaming match, the tears, the apology I would not accept—except the one I was living: me, quiet; them, talking around the obvious.

“Amanda,” I said, and held her eyes in mine. “Should I call Marshall Jones?”

The name hit the room like a slap.

Amanda’s mouth opened and closed once, twice. “I’m not— I’m not involved with—” She swallowed. No oxygen reached the lie. “No.”

I took the folded paper out of my pocket. It had lived there for four months, getting softer at the corners, heavier at the center. I unfolded it carefully and read the message that had burned a hole through my brain from the second I saw it.

My husband can never find out about us. I don’t want anything from you.

Silence. Even the heart monitor seemed to hold its breath.

“How—” Amanda croaked. “How did you get that?”

“Marshall sent it to me,” I said. “Screenshot. Time stamp. Your number. His number. Your name.” I tilted my head. “So did you sleep with him?”

She began to sob, the dry, scraping kind that sounds like a saw binding in a knot. “I… Jason, please. It’s not like that.”

My mother’s voice sharpened. “It’s exactly like that.”

Carol reached for my sleeve. “Jason, we don’t know anything yet. The baby could be yours. She could have made a mistake and regretted it. You travel. You leave her alone—”

“Four months ago,” I said to both women, to the nurse, to the fluorescent lights, “I found out she was cheating. I didn’t blow up her pregnancy for the sake of a fight she could not afford to lose. I waited. I waited for the child to be born so there’d be a body to test and a truth that didn’t depend on anyone’s performance.”

Amanda hugged the baby so tightly I thought she might try to fold herself into the child and disappear. “Please,” she whispered. “Don’t do this.”

“If he’s mine,” I said evenly, “I will sign the certificate. I will be the father the baby deserves. If he’s not, I will not pretend. I will not be a prop in a play I did not audition for.”

The nurse looked at me like she wanted to set me on fire and also bring me a sandwich. “Sir,” she said, “we can list the birth certificate as pending. You’ll have thirty days.”

“Fine,” I said.

The nurse retreated. Evelyn stood very still, hands at her sides, like a statue in a small, expensive museum. Carol started crying the way a mother cries when the world has decided to teach her child a lesson with no regard for mercy or timing.

“As for you,” I said to Amanda, because I had to say it while the honesty was still moving through me, “we’re done. I’ll have a lawyer call. I let you give birth in peace. Now I need peace for myself.”

I left before I could become the villain in a different story.

The night had the tang of wet asphalt. I drove aimlessly, windows down, wind scrubbing my skin like punishment or absolution—whichever came first. The image replayed: Amanda clutching the baby; the hurt on her face so absolute it looked like truth. That’s what I couldn’t get over: how liars always have the best tears. Practice, I guess. Or habit. Or the universe’s bad joke.

Back at my apartment, I stared at the ceiling until dawn scratched at the blinds. My phone buzzed until it went hoarse. I didn’t pick up.

Three days later, I sat across from Joanna Hines, a family lawyer whose office had no plants, no family photos, and a view across downtown to a courthouse where she clearly liked to win. She flipped through the printouts I’d laid on her glass desk: the messages, the email, the screenshot, the line I read in the delivery room.

“Do you want to file under adultery?” she asked, looking up. “No reconciliation?”

“I let her carry to term without war,” I said. “That was my reconciliation.”

Joanna’s eyebrow arched—approval, maybe. “We’ll file today. You also want a court-ordered DNA test if she doesn’t agree.”

“She will,” I said. “She knows there’s no point pretending anymore.”

My phone pinged all night. Seventeen texts. Two calls. A voicemail from Carol that sounded like prayer. Then my mother: “Jason, are you sure you want to do this now?” Quiet. Heavy. “She just had a baby. The shock—”

“You want me to wait until she’s rested enough to lie better?” I said, sharper than I meant. “If the baby is mine I’ll be there. But I won’t be drafted into someone else’s story as a ‘good man’ because we all like the way that phrase feels in our mouths.”

Silence stretched between us, a rope over a canyon. When she spoke again, Evelyn’s voice had an edge I recognized from childhood when she’d stare down whatever monster I thought was under the bed. “Then do it clean.”

“I intend to,” I said.

Four days later, the envelope slid across Joanna’s desk toward me.

I already knew what the paper would say. Knowledge had been living in my bones for months, rattling them like a dog with a chew. Still, I read.

Probability of paternity: 0%.

No rage. No relief. Just a dull correctness, like adding two and two and getting four, over and over, even when you wish the numbers would misbehave.

That afternoon, I drove to Carol’s quiet street with the live oaks that spend all summer pretending to shade you from things they cannot. Amanda opened the door. She looked like a house after a fire: standing, but nothing inside where it used to be.

“Where’s your mom?” I asked.

“In the kitchen,” she whispered.

Evelyn was there, too, sitting at Carol’s table with a chipped mug between her hands, the way women sit when they’ve agreed not to fall apart in front of each other.

I handed the envelope to Carol. “Please read it.”

She didn’t look at Amanda. She didn’t look at me. She read the lines as if each one added a year to her face. “Jason Walker… probability of paternity…” Her voice cracked. “Zero percent.”

Amanda made a sound I’d never heard from a human throat. She reached for me, but her hand didn’t land. I took a step back.

“I’m sorry,” she sobbed. “I’m sorry. You know I love you. You know I never meant to—”

“Maybe you didn’t mean to get caught,” I said, tired to the marrow. “But you meant to keep lying.”

She looked up at me with the kind of desperation that can convince a saint. “Forgive me. For the baby. Please.”

I held her eyes. “He’s not my baby.”

Evelyn looked down at the table. For the first time in a long time I saw something in my mother’s eyes that wasn’t command or correction. It might have been admiration. It might have been grief. It might have been both.

I walked out of that house with nothing in my hands and the truth in my pocket, heavy as a stone you keep choosing to carry because you won’t survive the places you’re going without it.

The courtroom was beige and air-conditioned and unromantic, the way courtrooms ought to be. The judge had a mouth like a seam. Amanda’s lawyer was young and glossy and already sweating. Joanna sat so still she looked carved.

Amanda went first. She said the words people say when they’ve blown a life up and want credit for acknowledging the shrapnel: loneliness, confusion, pressure. She said she had cut off the other man once she found out she was pregnant. She said she still loved me. She said she wanted to fix it.

Joanna stood and took the air out of the room with a file folder. “Your Honor,” she said, her voice a surgeon’s steady, “we have messages throughout the pregnancy. We have call logs. We have a line that says, ‘You don’t have to do anything. I’ll let Jason raise the baby if it’s his.’ We have a DNA test.”

She took one step toward Amanda, not menacing, just present. “You say Jason is a bad husband who abandoned you but you want to hold onto him? Why?” Joanna didn’t raise her voice. She didn’t have to. Reason has a timbre all its own.

Amanda stared at her hands until the truth bored through them. “Because he’s a good man,” she whispered. “Because he’s the best man I’ll ever have.”

The judge lowered her glasses. “Divorce granted,” she said. Her gavel sounded like a timer finally going off on a meal no one wanted to eat anyway.

I left without looking back. No movie music followed me down the steps. No relief marched in a parade. Just quiet. A long, complicated quiet that didn’t need my permission to exist.

That night, in a small apartment that smelled like new paint and old regrets, I made coffee by hand. I put on running shoes. I listened to a playlist from ten years ago, back when love had felt like a project you could finish if you just stayed up late enough.

Somewhere between tracks seven and eight, I realized I didn’t hate Amanda. Hate would have been easier than the empty I had instead. Hate has rituals. Emptiness just sits there, ugly and honest, waiting for you to decide whether you’ll fill it with something worse or something better.

I decided to wait.

Part II

I didn’t go to the funeral.

That’s the kind of sentence people like to judge because it gives them something to do with their mouths. I didn’t go because it wasn’t my place. Because we were divorced. Because the grief the room was built to hold wasn’t mine to touch. Because stepping into the river of other people’s sorrow uninvited is just another way of making it about yourself.

Two weeks after the decree, my mom called. She never hedges; that day she hedged. “I’m at Carol’s,” she said. “Amanda’s gone.”

“Gone where?” I asked, stupidly, because disbelief is a blunt instrument.

“Gone,” she said softly. “There was an accident at the lake. A slide in. Crocodile pulled her under before someone could get to her. It was fast.”

I didn’t say anything. A lot of words are wrong in the face of that, and I’ve learned that the safest word, when you have none that will help, is silence.

“What about the baby?” I asked finally. My mouth felt like it belonged to someone less careful.

“He’s with Carol.” She exhaled something that wasn’t quite a sigh. “Jason, don’t… don’t let shame make your decisions. Whatever you feel, feel it. But the boy didn’t do this.”

“I know,” I said.

I waited a week. Then I parked in front of Carol’s house and stared at the porch where I had once carried a stroller that felt like a life raft. The door opened before I knocked. Carol wasn’t the same woman. Grief had sanded her edges and left her raw.

In the living room, a small boy sat on the carpet, hugging a teddy bear by the neck, watching me like a dog looks at thunder: braced, curious, ready to bolt.

“You’re Miss Linda’s son,” he said—my mother’s name, his nickname for her.

“I am,” I said, kneeling so we were eye-level.

He studied me like a judge. “So what are you to me now?”

The room waited.

In the past year I had been called a lot of things by people meaning well and not—husband, betrayer, victim, hero, fool. None of them fit. The correct answer was a geometry problem. If Amanda was no longer my wife and the baby wasn’t my son and love is either a straight line or it isn’t—what are you?

“I’m the guy who’ll walk you to school,” I said slowly, because truth deserves slow. “I’m the guy who’ll patch your knee when you crash your bike. I’m the guy who’ll listen when some kid in class won’t quit bothering you. I’ll be here. That’s what I’ll be.”

He nodded once, solemn as a notary. “Okay.”

That night, I told my mother what I’d told him.

“Good,” she said simply. “Action over adjectives.”

We arranged guardianship first—papers and signatures and a judge who asked me whether I understood that love ain’t tax deductible. I did. Then, because grief doesn’t leave vacancies unfilled forever, we began to build a life with more routines than habits and more choices than rules.

Tim—his name—had Amanda’s eyes, Carol’s stubborn chin, no patience for blocks that didn’t click, and a laugh that made neighbors mind their own business. He did not ask about his father. Later, maybe. Children time their questions like surgeons choose their cuts: when they can do the least damage.

I learned that the difference between being alone and being quiet is a six-year-old who yells from the bathroom that the toothpaste “tastes like regret.” I learned to fold tiny socks into pairs that never stayed paired. I learned that a grown man can survive on dinosaur chicken nuggets and broccoli if he is motivated by a face that will not forgive failure in the hot-dog-bun-to-hot-dog ratio.

We drew lines and colored outside them. Bedtime was a suggestion. Books were mandatory. Apologies required specificity. I taught him to tie his shoes; he taught me that my shoe-tying technique was outdated and dangerously close to “baby style.”

On a Sunday afternoon, helping my mother reorganize a bookshelf that had stood against the same wall my entire life like a witness, I found a leather notebook with its strap gone slack. An old photo slipped out—my mom and Carol in matching uniforms, hair pulled back, faces hard with a kind of duty I had never had to cultivate. On the back in neat block letters: Langley, 1999 — George Bush Center for Intelligence.

I turned the photo. I turned to my mother. She shrugged like I’d asked whether she wanted tea. “Logistics,” she said. “It’s always logistics.”

“You worked for the CIA,” I said, which is like telling someone their hobby is “space.”

“Just logistics,” she said again, but there was something in her eyes—the flat-blue calm of a woman who has carried secrets across rooms and oceans and learned to put them down without making a sound.

It made sense, suddenly, the way she could read a room like a map, the way she could hunt for truth without blinking, the way she could stand in a doorway and make grown men decide to confess. Strength isn’t about controlling other people. It’s about refusing to let other people’s chaos turn you into something you’re not.

That night, we sat in the small light of her kitchen. She didn’t add footnotes or cautionary tales. She didn’t say she was proud of me. She buttered toast and slid me a slice and looked at me the way you look at a man who has decided to keep walking when stopping would be more convenient.

Nothing has ever tasted better.

I met Kelly on a Wednesday that was trying to be Monday.

At the hardware store, because nothing honest starts on an app. She was buying a new switch plate; I was buying the wrong size drywall anchors. She corrected me with the gentle tyranny of someone who knows what a pilot hole is and isn’t threatened by a man with a cart. We got to talking the way two strangers talk when they both know what it is to sit on a couch at dusk and ask themselves whether quiet is a symptom or a cure.

She told me she was a veteran; I told her I was a man learning how to make a kid laugh even on the days I didn’t feel funny. She didn’t ask about Amanda. She didn’t look at Tim like a test. She asked, “Do you like being quiet with someone?” and when I said yes, she said, “So do I.”

We went slow because rushing is a lesser god. We met for coffee that didn’t attempt to impress us. We walked the long way home even when the short way was smarter. When I introduced her to Tim, she brought a toy that wasn’t noisy, a book he could pretend to read, and a patience I couldn’t have purchased at full price.

A year later we got married in a ceremony so small it could fit in an index card. My mother smiled through it all, her hand on Carol’s, two women who had learned to survive their own lives applauding the fact that I had finally started to survive mine. Tim wore a suit that made him look like a bouncer at a lollipop nightclub.

Two months after that, my mother died the way she had lived: efficiently. No long fade. No dramatic hospice speeches. She laid down for a nap and did not get back up. The paramedics were kind. The coroner was softer than I expected. Carol held my face in both her hands and said, “She raised you for this,” and I knew what she meant: not the grief. The carrying on.

Carol followed her a season later. I think grief untied something in her that duty had been holding together with fraying twine. She had given so much of herself to other people’s emergencies that when they stopped she didn’t know where to put her hands.

We buried them on a cool day. Tim asked if heaven had a cafeteria. I said probably, but the macaroni would be suspiciously good.

At home, Kelly moved around the kitchen like a prayer. Tim drew spaceships at the table, narrating the fuel levels. I sat down to write because writing had become the room in the house where I kept the ghosts. I wrote what I’m writing now. I wrote to the man who stood in that delivery room and thought cruelty and clarity were the same tool. I wrote to the boy with the teddy bear and the solemn nod. I wrote to the woman who sent tea over silence and the other who died in water and the other who learned to love a man who doesn’t apologize for surviving.

When I was done, I put down the pen and looked up. Tim held up his sketch. “Rocket,” he said. “It gets out.”

“That’s all we ask,” I said.

Part III

You’d think the loudest rooms in my life would be the ones with gavels. It turns out the loudest rooms are kitchens, ten minutes after homework, when a nine-year-old discovers that fractions aren’t suggestions.

“Three quarters,” Tim said, stabbing his pencil at the page. “Why isn’t that a whole?”

“Because a piece is still a piece,” I said, “no matter how loud it wants to be a whole.”

He glared. “That’s not math.”

“It’s the kind you’ll need,” I said, and he rolled his eyes in a circle big enough to qualify as cardio.

We were becoming a family in a hundred tiny ways that didn’t make it into movies: groceries that finally matched appetites; calendars that agreed to disagree; Lego landmines reduced by 40% thanks to a truce hammered out under threat of vacuum. Kelly’s shoes at the door next to mine. My mother’s old mug—World’s Okayest Mom Tim had given her as a joke—on the shelf where I could see it and plan to use it on days I remembered to act like the man she had made.

At night, after bedtime negotiations ceded territory, Kelly and I sat on the couch with our knees touching and the TV blessedly off. We talked like burglars: quietly, about plans.

“Do you ever hear it?” she asked once, looking toward the window where the city did its expensive breathing. “The before?”

“I smell it,” I said. “Antiseptic. Paper burned around the edges. A grief that thinks it’s smarter than you are.”

She took my hand. “You’re allowed to miss what should have been,” she said. “Just don’t let it trick you into mourning what never was.”

Sometimes the past is a drunk friend demanding a couch. I give it a blanket and I let it sleep, but I don’t make it breakfast.

We didn’t talk publicly about Amanda. People tried to make my life a parable anyway. Some called me heartless; some called me a hero; some sent messages written in the spiky script of anonymous certainty, telling me what they would have done, how forgiveness is the nuclear option and real men never use it.

The only opinion that mattered belonged to a kid who had mastered long division and most of his monsters. One afternoon, we were stopped at a light and he said, without looking up from the comic he was devouring, “I’m glad you didn’t lie.”

“About what?” I asked, even though I knew.

“About the paper,” he said—the DNA test. “You could have pretended.”

I swallowed. “Why are you glad?”

“Because if you’d lied then,” he said, still reading, “you’d think lying is how we love people.”

I put my hand on the steering wheel like it was the only bridge between me and drowning. “We don’t,” I said. “We don’t.”

He nodded. “Okay.” The light turned green. We moved forward.

Grief interrupts itself to make room for logistics. The custody paperwork, the guardianship updates, the visits from social workers who do their jobs with the kind of patient ferocity that deserves parades. One of them, a woman with a sleeve of tattoos complex enough to require a guided tour, sat at our kitchen table drinking my awful coffee and said, “You’d be surprised how often biology is a poor predictor of parenting.”

“I would not,” I said.

She grinned. “Fair.”

Another afternoon, a legal envelope arrived with a letter that wanted tailwinds. Amanda’s estate—mostly debts—needed an executor. Carol had named me. I went to the courthouse and filed the forms and sat in a hallway listening to the echo of other people’s disasters. When the clerk called my name, I stood. She glanced at my paperwork. “You’re the ex-husband,” she said, not unkindly. “That’s rare.”

“Not really,” I said. “Just unpopular.”

She stamped the papers with a thunk that felt like closure if you squinted.

People assume forgiveness is an event. It’s a practice. I didn’t forgive Amanda in the courtroom or the kitchen or the car. I forgave her in a series of boring ways: by not rehearsing arguments she never heard; by refusing to narrate myself as a victim in the presence of a boy who needed a map, not a martyr; by deciding, again and again, not to call pain by the wrong name.

I didn’t romantically “forgive and forget.” I forgave and remembered. I forgave and parented. I forgave and changed the oil, and made lunches, and told Tim that if he left a banana in his backpack again I would petition the city to condemn the school.

Kelly forgave me my anger, which is a different kind of miracle. She didn’t flinch when I woke from a bad dream sweating like I’d run from wolves. She didn’t analyze me when I went quiet. She put her hand on my back and waited. You can build a cathedral out of waiting, if both of you are willing to sit on the floor while it goes up.

On our first anniversary, we took Tim to the beach and taught him how to let the waves knock him down without making it feel like an insult. He screamed and laughed and demanded we watch every single time the ocean proved its point. Walking back to the car, sun drunk, he slipped his hand into mine and said, “Dad?”

The word didn’t wreck me. It steadied me. It felt like the correct label on a box that had been carrying the right thing all along.

“Yes?” I said.

“Do we have to do fractions tomorrow?”

“Yes,” I said, and he groaned like a creature from a B-movie, and the world felt, for a full minute, exactly as heavy as it should be.

Part IV

You can build an entire life around never being surprised again. It’s a respectable project. I tried for a while. Lists help. So do routines. So does the decision to be the first one to the bad news. But life loves a good ambush. The trick, I’m learning, is to accept the surprises you’re grateful for and survive the ones you’re not.

The letter about Amanda’s accident had been surprise of the second category. The letter from Marshall was the first.

It arrived without a return address. Inside, a note written in a hand that wanted to be forgiven for its own neatness.

Jason—

I don’t have the right to write you. I’m doing it anyway. I’m in a program. They tell us to make amends. I don’t have amends to offer you that would matter. I just wanted to say I was a coward, and a liar, and I hurt her, and I hurt you, and I’m sorry. I never asked her to lie. I never asked her to keep the child from you. But I didn’t stop it either. I told myself a lot of stories about feelings. None of them were true. I don’t want anything. I won’t contact you again. —M.

I sat with the letter for a long time. My first impulse was to set it on fire. My second was to send it to a lawyer. My third was to put it in a drawer and let it become a bookmark for a book I’d never finish.

Instead, I took it to Carol. She sat at her kitchen table, thinner than grief should legally be allowed to make a person. She read it silently. She didn’t cry. “He was a boy,” she said, finally.

“He’s older than I am,” I said.

“Some boys stay boys a long time,” she said. “Some die that way.”

We drank tea and didn’t talk about forgiveness because we both understood it has nothing to do with letters arriving on time.

On the drive home, Tim asked if I believed in second chances. “Depends,” I said. “On what you do with the first one.”

Work didn’t stop because my personal life had been an action movie. I run a small team that solves other people’s messes before they spill. Supply chain triage. Vendor fraud detection. “We keep your promises possible,” our website says, which is just pretentious enough to sign checks.

One afternoon, my phone buzzed with a number I recognized: a hospital in the city where I was the guy with cold eyes in the delivery room. The caller was a nurse who had been there that day, the one with the clipboard.

“I shouldn’t be calling,” she said. “But I think about that room a lot. The way you stood there. Everyone said you were cruel.”

“They still do,” I said.

“You were clear,” she said. “There’s a difference. I just wanted to tell you I’ve used your sentence twice since then—with fathers who looked like they wanted to launch themselves off the building rather than face the possibility. We put ‘pending’ on the certificates. They got the tests. One was the father. One wasn’t. Both babies got the truth. It mattered.”

I didn’t know what to do with that. I still don’t. I thanked her. I hung up. I sat in the car long enough for the meter to tut at me.

At dinner, I told Kelly the abbreviated version. She squeezed my hand. “Clarity isn’t cruelty,” she said. “It just has bad PR.”

Grief came back for a victory lap when my mother’s things arrived from her house in boxes labeled in her precise hand: kitchen, books, Jason’s embarrassing school art. In one box I found an old fountain pen, black lacquer, gold clip, weighty enough to double as a paperweight in a gale. I cleaned it. I filled it. I signed a contract with it the next day, and thought, absurdly, of holding the pen to my ear to see whether it remembered anything it wanted to tell me.

A week later, another box—no return address. Inside, tissue, then a similar pen, and a note in a hand that tried to pass as anonymous and failed. We ship what we can carry. —M.

I didn’t write back. I didn’t smash it. I put it in a drawer. One day, I told myself, I would sign something that mattered with it, and in the act of signing convert part of what he meant to me into ink that would dry and stay.

The next morning, a package from Texas. Elena—not her name, but it might as well have been. A photograph: a woman holding a baby whose hair had decided to imitate the sun. On the back, in the kind of handwriting you acquire only after you have lied to yourself and stopped, finally: This is David Jr. He has his father’s patience and my eyebrows. Thank you for saying change is a direction, not a destination. I’m walking.

Kelly tucked the photograph into the edge of a frame on our shelf, next to a map Tim had drawn of the route from our house to the park to the taco truck to the galaxy. It looked right there, a pin on a route that had been hard to follow and worth it.

At some point, a story stops being about the thing that broke you and starts being about the life you built in the shape of the break. I didn’t realize I’d crossed that line until a social worker asked me, in the friendly tone of someone finishing a checklist, whether I had “moved on.”

I wanted to tell her that “moving on” is a terrible metaphor—that nobody leaves grief like a city and sends for their furniture later. You move with it until it moves with you. You stop looking for a place to drop it. You make room in the car.

Instead I said, “Yes,” because paperwork deserves closure even when life doesn’t.

On the anniversary of the day I said “after the DNA test,” Kelly took us to breakfast at a place where the pancakes come the size of pizza stones. We ate until the syrup declared us defeated. Tim went to the restroom and came back with his hands damp and that look children get when they are proud of doing something they used to be afraid of.

“Soap,” he said, brandishing foamy fingers. “I used extra.”

“Good,” I said. “Things are cleaner when you insist.”

Kelly smiled over her coffee. “Put that on a pillow.”

“I will,” I said. “But the pillow will judge you if you don’t make your bed.”

We walked out into a day so bright it felt like someone had given the sun too much responsibility. I felt the old ache walk beside me like an acquaintance who had learned some manners. I felt my mother’s hand on my shoulder and Carol’s hand on my cheek and Amanda’s voice in the water and Marshall’s letter in a drawer and a nurse with a clipboard saying I was cruel when what I was, in fact, was finished lying.

It didn’t feel like victory. People say that when you do the right thing you get a parade. You don’t. You get groceries, and a math worksheet, and a dog you said yes to against your better judgment because Tim made a face you couldn’t live with saying no to.

His name is Rocket. He chews shoes. He forgives everything.

Part V

I promised myself that when I found the ending, I wouldn’t rush it. Endings deserve to be landed, not slammed.

We had dinner with Carol’s sister the night Tim’s basketball team lost a game by so much the scoreboard ran out of digits. She fed us meatloaf and humor and the kind of quiet that gives you back pieces of yourself you didn’t know you mislaid. On the way home, Tim fell asleep in the backseat with his mouth open, a comic book face-down on his lap like a fainted bird.

At a red light, Kelly said, “Do you ever think about the man in that room? The one with his hands in his pockets?”

“I try not to,” I said. “He thought clarity and cruelty were the same knife. He was wrong. But he was brave enough to use the knife anyway.”

“He saved you,” she said.

“He saved us,” I corrected.

At home, we carried Tim upstairs. He mumbled “rocket boosters at 70%” and surrendered to gravity. I closed his door and stood in the hallway long enough to count ten slow breaths, the way my mother taught me to do when I had to choose between anger and accuracy.

Kelly came up behind me, slid her arms around my waist, and rested her cheek between my shoulders. “Endings,” she said, “are just beginnings with better manners.”

“I know,” I said. “I want one anyway.”

The next morning, I sat at the kitchen table with the good pen and wrote three letters.

The first was to the nurse with the clipboard, care of the hospital, in case the address forwarded. Thank you for telling two men the truth with me when I wasn’t there to say it myself. I didn’t sign my full name. She wouldn’t remember it. She would remember the sentence.

The second was to the social worker with the sleeve of tattoos. You were right. Biology is a poor predictor of parenting. But it’s a great predictor of who needs a nap. She sent back a smiley face, which I took as the official seal of the State of California.

The third was to myself—the man in the room, hands in pockets, eyes like ice. You were wrong about a lot. You were right about the one thing that mattered: that the truth doesn’t become less true because it arrives at an inconvenient hour. I forgive you for the mess you made and the mess you refused to sweep under the rug. I forgive you for the sentences you said badly. I forgive you for not pretending to be a saint just because people wanted you to play one. Now go make breakfast.

I made pancakes. They came out misshapen and glorious. Rocket sat at my feet staring up with the faith only a dog and a child know how to hold. I burned the last one because Tim told a joke so dumb and perfect I laughed until my eyes watered.

Later, we drove to the park and threw a ball until the dog remembered he is, in fact, a dog. We walked past the lake where the city had installed new warning signs and extra fencing and a plaque for the woman who had fallen in. I didn’t read it. I didn’t need to. I said her name out loud—just once, quiet—and kept walking.

At home, I took out the second pen—the one from Marshall. I had been saving it for something that mattered. I pulled the adoption papers out of the folder. The truth is we already had guardianship, already had the day-to-day, already had the jokes and the laundry and the study guides. But I wanted it legal. I wanted the name to match the life.

Tim came into the kitchen with marker on his fingers and justice in his eyes. “Whatcha doing?” he asked.

“Signing something,” I said.

“Cool,” he said. “Can I sign?”

“You will,” I said. “There’s a line for you. It says you agree to be part of this ridiculous circus.”

He grinned. “I agree.”

Kelly stood behind us and took a photo with her phone. It’s the one on our mantle now—not the wedding, not the first day of school, not the dog covered in toilet paper. The three of us at the counter, a pen in my hand, Tim leaning in, Kelly’s smile visible even from behind the lens. It looks like a family that didn’t find each other so much as recognize.

We took the papers downtown the next day. The clerk, the same woman with the thunk stamp, looked up and this time didn’t say anything about rarity. She stamped. She smiled. She said, “Congratulations,” in a tone that meant she wasn’t bored with it yet.

Outside, the air smelled like a decision that had finally forgiven you for taking so long to make it.

A week after that, I got an email from a stranger with a subject line I almost deleted: Your story. I opened it because I am still, in spite of myself, a man who believes letters matter.

Jason, it read. I was the guy with the hands in his pockets. Different hospital. Different woman. I said your sentence. They called me heartless. The test said what my bones already knew. I didn’t know what to do with that. Then I read something you wrote about being clear and not cruel, about refusing a role you didn’t audition for. It didn’t make me feel better. It made me feel less alone. That was enough. Thank you.

I wrote back. I don’t always. This time I did. You’re not heartless. You’re honest. Don’t confuse the chorus with the truth. Feed the baby if they’ll let you. Or don’t. You’re allowed to protect what’s left of you. Either way, sign what is real.

He sent back a single word: Okay.

On a warm Saturday, we held a small memorial for Evelyn and Carol in the backyard. We invited the people who had earned the right to speak. We told the truth about two women who had learned to breathe underwater and then taught us how to swim. We read nothing from the internet. Tim, in a shirt he hated, stood up on a chair and said, “Grandma could see through walls. Nana could say words so fast you thought you were in trouble, but you weren’t. I miss them. The end.” It was perfect.

After, Kelly hugged me and said, “You built a life that doesn’t apologize for being made out of broken parts.”

“So did you,” I said.

The sun went down. The porch light came on. Rocket found a frog and learned what frogs do when confronted by a dog with bad decisions. We laughed. We cleaned up. We went to bed bone-tired the way you get when you spend a day with people you trust.

In the middle of the night, I woke and listened to the quiet. The old ache stirred. I said out loud, to the dark, “You can stay if you’re quiet.” It settled. I slept.

And this is the part where an ending is a beginning and isn’t coy about it. It’s not a parade. It’s breakfast. It’s a school drop-off. It’s a dog who forgives you for being gone all day as if forgiveness is the only trick he knows. It’s a kid who asks if there’s such a thing as seven-quarters and a woman who looks at you like a promise you didn’t break.

It’s the delivery room in your rearview mirror, the paper that didn’t cry, the judge’s gavel that didn’t give you a personality, the letter you didn’t answer, the pen you saved for a name that deserved to be written with it, and the lake you walked past without lecturing the water about fairness.

It’s the sentence you said when a room wanted a story. We’ll fill it out after the DNA test results come back. It was a door you opened, not a grenade you threw. The blast was just the air rushing in.

This is the ending: clean, not kind; quiet, not soft; true, not tidy.

You wanted a dramatic story. Life obliged. But the drama isn’t the point. The point is the life on the far side of it—the one where you get to choose, again and again, to be the person you were half-afraid you didn’t have the stamina to become.

I became him. I’m still becoming.

Tim will ask tomorrow about improper fractions. Rocket will eat another sneaker. Kelly will kiss my temple while coffee waits for us to decide we’ve deserved it. We’ll sign more things. We’ll refuse to sign others. We’ll go to the park, and the taco truck, and the galaxy.

And when somebody asks what I did when the room overflowed with joy and I refused to perform a part of the play that wasn’t mine, I’ll say: I told the truth. It cost what it cost. It bought what it bought.

THE END

News

She Came Back From Her Affair Acting Normal — Until One Step Into Our Bedroom Changed It… CH2

Part I It was 3:17 in the morning when she assumed I was asleep. I lay on my right side,…

I Was In Labour Begging My Parents To Take Me To Hospital They Left Me On Road Dad Said Die On Road… CH2

Part I: I was twenty-five when my body finally spoke louder than my fear. The first contraction took my breath…

“Why Can’t You Be More Like Her?” He Asked — So I Stopped Trying to Be Anyone Else. Now He’s… CH2

Part I My name is Irene Betts, and I learned the hard way that love doesn’t always go out like…

After my husband passed away, my son became the CEO of the family business, and I pretended I hadn’t… CH2

Part I I was arranging lilies in the blue vase Richard bought me in ’83 when I heard my daughter-in-law’s…

On My Wedding Day, Not a Single Family Member Showed Up. Not Even My Father Who… CH2

Part I: There are moments in life when silence becomes a living thing. On the morning of my wedding day,…

I Found My Wife’s Hotel Receipt With Another Man’s Name. Then I Went To The Garage… CH2

Part I: I found it by accident, which is probably how most catastrophes begin. The hotel receipt was jammed down…

End of content

No more pages to load