Part 1: The Morning It All Fell Apart

The sun rose softly over Boise that April morning, spilling a golden light across the neat, suburban rows of Aspen Ridge Drive. Birds darted through the clear sky, lawns glistened with dew, and for the Ringstaff family, the day began much like any other. Inside their two-story colonial home with its blue shutters and carefully trimmed garden, the smell of coffee mingled with the sugary scent of cereal. Charles and Heather Ringstaff, both professionals in Boise’s growing tech sector, were running late for work—again.

Charles was searching for his keys while juggling a laptop bag and travel mug, calling over his shoulder, “Brittany, let’s go! You’re going to miss the bus again!”

From upstairs came the unmistakable sound of a slammed door. “I said I’m coming!”

Heather sighed, brushing her hair back and muttering, “Fourteen going on forty.”

At the kitchen counter, eight-year-old Jeremy sat cross-legged on a stool, spooning cereal into his mouth, his backpack half-zipped beside him. His brown hair stuck up in odd directions, his socks didn’t match, and there was a smear of milk on his chin. He looked every bit the little brother—sweet, chaotic, and unaware of the storm building across the breakfast table.

When Brittany finally appeared, she moved like a thundercloud. She tossed her backpack down and scrolled through her phone with a frown so sharp it could cut glass. Her blonde hair, streaked with fading purple dye, fell across one eye.

Jeremy, eager for attention, reached over for the cereal box—and his elbow bumped her phone.

The sound of shattering glass hit the kitchen like a gunshot.

Brittany froze. Then, slowly, she turned her gaze toward the floor where her phone lay facedown, its screen splintered into a web of cracks.

“You idiot,” she hissed.

“I—I didn’t mean to—” Jeremy started, his face pale.

“You broke it! You broke my phone!” Brittany’s voice rose to a shriek that made Heather spin from the sink.

“That’s enough!” Heather barked. “Brittany, calm down. It was an accident.”

“An accident?” Brittany’s eyes filled with angry tears. “You always take his side! Every time!”

Heather’s tone sharpened. “That’s it. You’re grounded this weekend, and I’m taking the phone.”

“You can’t—”

“I can and I am.” Heather snatched the phone off the floor, ignoring the cracks that shimmered across its black screen.

For a second, Brittany just stood there, her breath coming fast. Then she leaned toward her little brother, her face inches from his. Her voice dropped to a dangerous whisper.

“You’ll pay for this.”

Charles, already juggling too much, dismissed it with a tired laugh. “Enough drama, Britt. He didn’t mean to. Let’s move, people.”

But Brittany wasn’t laughing. Her eyes never left Jeremy’s as their parents ushered him out the door for the morning drive to school. He turned back once, waving awkwardly, but Brittany didn’t wave back. She just stood there in the doorway, her jaw clenched, her fingers trembling.

When the cars pulled away, silence filled the house—a silence thick enough to suffocate.

And in that silence, a plan began to form.

By 8:30 a.m., the Ringstaff home looked peaceful again from the outside. Neighbors passed by on their morning jogs, waving toward the quiet blue-shuttered house. Inside, Brittany sat at the kitchen table, her mother’s laptop open before her. The cursor blinked on a school attendance form.

“Hello, this is Heather Ringstaff,” she said softly, mimicking her mother’s steady tone. “Brittany’s sick today—fever, headache. She’ll be staying home.”

Her heart raced as she clicked “submit.” The lie slid easily through her lips. Too easily.

Next, she called Jeremy’s elementary school. “This is Heather Ringstaff,” she said again, her voice just a shade more confident now. “There’s been a family emergency. I need Jeremy released early today. I’ll be picking him up.”

Her hand shook as she hung up.

The first domino had fallen.

She took the public bus instead of her own school bus, hood pulled low, earbuds in but no music playing. The world moved around her in snapshots—the hum of engines, the laughter of strangers, the smell of diesel and morning rain. She barely noticed.

Her mind replayed the image of her shattered phone screen again and again, the spiderweb of cracks glinting like a wound.

When she arrived at Jeremy’s school, she forced a smile for the office clerk. “Family emergency,” she said, handing over the signed form.

Jeremy appeared a minute later, small and confused, clutching his backpack straps. “What happened?” he asked.

“Grandma’s in the hospital,” she lied. “Mom said we need to go home.”

He nodded, trusting. Always trusting.

At 11:15, a convenience store security camera caught the siblings buying a soda and two candy bars. Jeremy picked a root beer, Brittany grabbed a Coke. She even smiled at the clerk, like any normal teenage sister out with her brother.

They looked ordinary—so heartbreakingly ordinary.

The bus driver who took them back home would later testify that they sat quietly together, side by side. Brittany looking out the window, Jeremy kicking his feet and sipping his soda.

Nothing seemed amiss.

When they stepped off at Aspen Ridge Drive, the neighborhood was still, the only sounds the distant whine of a lawnmower and the chirping of birds. Brittany’s key turned smoothly in the lock. The door opened.

The house greeted them with silence.

“Can I watch TV?” Jeremy asked.

“Sure,” Brittany said. “I’ll be upstairs.”

As he disappeared into the living room, she walked up the staircase slowly, every step echoing louder in her chest. In her mind, she told herself it was just about scaring him. Just to make him sorry. Just so he’d know what it felt like when someone broke something you loved.

She ran the bath.

The water splashed against porcelain, clear and calm.

The next time anyone saw Jeremy alive, he was walking up the stairs, a soda can in one hand.

“Britt?” he called softly.

“Yeah,” her voice answered from the bathroom. “Come here a sec. I have a surprise for you.”

The last words he ever heard were spoken in a calm, even tone.

At 2:15 p.m., Heather Ringstaff pulled into the driveway, exhausted. She’d received calls from both schools and assumed there’d been some mix-up. Her heels clicked up the steps as she called out, “Brittany? Jeremy? You two home?”

The moment she stepped inside, something felt wrong. The house was too quiet.

Then she saw the water.

A slick trail led from the bathroom down the hallway, the carpet soaked.

“Jeremy?”

Her voice cracked as she rounded the corner—and the scream that tore from her throat brought neighbors running.

Her son lay motionless in the hallway, eyes open, skin tinged blue.

Heather dropped to her knees, pressing her hands to his chest. “No, no, no—come on, baby, breathe—please!” Her voice broke into sobs. She started CPR, counting between gasps, her tears falling onto his still face.

When the paramedics arrived minutes later, they found her still trying, her hands trembling violently. Brittany stood nearby, her face pale and unreadable.

“She just stood there,” neighbor Margaret Lawson would later tell police. “Her mom was screaming, and that girl looked… empty. Like nothing was real.”

It was already too late. Jeremy had been dead for hours.

Detective Adrien Mitchell arrived at the scene at 2:43 p.m. A 15-year veteran of the Boise Police Department, he’d seen every kind of horror imaginable—but something about the quiet, suburban normalcy of the Ringstaff house unsettled him deeply.

The boy’s body lay fully clothed outside the bathroom. The tub was half full, the water cloudy with soap and traces of blood.

Mitchell scanned the scene, frowning. “This doesn’t look like a fall,” he murmured to the forensic tech.

In the corner, Brittany sat on the staircase, her knees pulled to her chest. Her face was expressionless, her voice flat when she finally spoke. “He slipped,” she said. “I tried to help.”

Her hands trembled slightly as she brushed hair from her eyes. That’s when Mitchell noticed it—dried, reddish-brown flecks beneath her fingernails.

He motioned for the tech. “Bag her hands,” he said quietly.

Hours later, the house was sealed with yellow tape. Reporters began to gather outside as word spread: a child had drowned. But within hours, whispers started. It wasn’t an accident.

It was something else.

At the station, Brittany repeated her story in a flat, detached tone. “He fell. I tried to pull him out.”

But she couldn’t explain the bruises on Jeremy’s arms or the scratches on her own. She couldn’t explain why the washing machine was still warm, full of wet, blood-specked clothes.

When detectives asked why Jeremy had been fully dressed in the tub, she hesitated. “He… didn’t want to take his clothes off. I told him to get in anyway.”

The lies unraveled fast.

By the time the autopsy confirmed drowning—water in the lungs, bruising consistent with being held down—Detective Mitchell knew what had happened.

He’d seen adults kill for money, revenge, jealousy. But never this. Never a sister killing her brother over a broken phone.

When they came to arrest her that night, Brittany didn’t fight. She just stared blankly at the officer’s badge and said softly, “It wasn’t supposed to go this far.”

The words followed Mitchell home that night, echoing long after he’d turned out the lights.

The next morning, headlines blared across Boise:

“14-Year-Old Girl Arrested in Brother’s Drowning Death.”

A quiet, tech-friendly city suddenly found itself the center of national horror. Reporters crowded outside the courthouse, their cameras capturing a pale, handcuffed girl led into juvenile detention.

Brittany Ringstaff became a name everyone knew—and no one could understand.

Inside the sterile walls of the Ada County Juvenile Detention Center, Brittany was processed like any other inmate. Fingerprints. Mugshot. Paperwork. Her gray uniform hung loose on her small frame.

Most kids cried during intake, begged for their parents, trembled through every question.

Brittany didn’t cry. She just asked, “When can I get my books?”

The officer processing her paused. “You understand what’s happening, right?”

She nodded once. “They think I killed him.”

“And did you?”

She didn’t answer.

That night, in her narrow bunk, Brittany stared at the ceiling while muffled sounds echoed through the halls—footsteps, keys, a distant voice shouting. She thought about the water, about Jeremy’s small hands clawing at hers, about the way the tub had gone still when he stopped moving.

She pressed her palms to her face, trying to block the images, but they came anyway. The silence after the struggle. The way his eyes had looked—wide, terrified, then empty.

In the darkness, she whispered the words that would soon haunt an entire courtroom.

“I didn’t mean to.”

But even she didn’t believe it anymore.

Part 2: The Interrogation

The Boise Police Department’s juvenile interview room didn’t look like an interrogation chamber. The walls were painted a calming shade of blue, the lights were soft, and a shelf of children’s books sat untouched in the corner. But the camera mounted high in the corner of the ceiling told the truth: everything said inside this room would become evidence.

Detective Adrien Mitchell sat across from Brittany Ringstaff at a small round table, a file open before him. A female officer stood by the wall, silent. Between them sat a Styrofoam cup of untouched water.

Brittany wore her gray detention sweatshirt and jeans. Her hands were clean now—swabbed, photographed, bagged—but Mitchell could still see the faint scratches along her wrists.

He studied her face: fourteen, but with the stillness of someone much older.

“You know why you’re here, right?” he asked softly.

She nodded, eyes fixed on the table. “Because Jeremy died.”

“That’s right.” Mitchell leaned forward slightly. “I want to help you tell me what really happened.”

“I already did.”

“You told the responding officers that Jeremy slipped and hit his head.”

“He did.”

“Then you said he was taking a bath.”

“Yeah.”

“Except he was fully clothed.”

Brittany’s eyes flicked upward for the first time. “He didn’t want to take his clothes off.”

Mitchell let the silence stretch. “He drowned, Brittany. He had water in his lungs. You know what that means?”

Her voice was a whisper. “That he was breathing when he went under.”

“That’s right. And we found his blood under your fingernails.”

She frowned. “Because I tried to pull him out.”

Mitchell flipped a photo onto the table: close-up images of Jeremy’s arms, crisscrossed with scratches. “These are defensive wounds. Do you know what that means?”

Her breathing quickened.

“They mean your brother was fighting back.”

“I didn’t—”

Mitchell’s tone stayed calm, but his voice tightened. “You did, Brittany. You held him under. I need to understand why.”

“I told you—”

He slid another photo across the table—her wet, blood-specked clothes, recovered from the washing machine. “You tried to wash these after, didn’t you?”

Her eyes widened for just a second, then narrowed again. “They were dirty.”

Mitchell folded his hands. “Dirty from what?”

Silence.

“From Jeremy’s blood?”

She stared at the table, her jaw clenched.

He exhaled. “I’ve been doing this a long time. I’ve seen good people make terrible mistakes. If this was an accident—if you just lost your temper—you need to tell me now.”

For the first time, her composure cracked. “It wasn’t supposed to go that far,” she whispered.

Mitchell kept his voice low. “Tell me what you mean.”

“He broke my phone.”

“Okay.”

“He broke my phone, and Mom took his side. She said it was my fault.” Her voice grew sharper. “It’s always my fault. Everything.”

“So you decided to punish him?”

“I wanted him to know what it felt like,” she said, her voice trembling. “To lose something you love.”

Mitchell’s pen hovered above his notepad. “What did you do, Brittany?”

She hesitated, her lips trembling. “I told him I had a surprise for him in the tub.”

“And then?”

“I pushed him.”

Her eyes filled with tears she didn’t bother to wipe away. “He started screaming. Splashing. He wouldn’t stop. I told him to calm down, but he kept kicking, and I just—” Her hands clenched into fists. “I just held him down until he stopped moving.”

The words hung in the air, quiet and heavy.

Mitchell’s hand trembled slightly as he clicked off the recorder. “That’s enough for now.”

When Detective Mitchell stepped into the hallway, he found Assistant District Attorney Elizabeth Howard waiting, a stack of files tucked under one arm. She was mid-forties, composed, and known for never losing a homicide case.

“She confessed,” Mitchell said flatly.

Howard raised an eyebrow. “Full confession?”

“Partial. Enough to make it stick. She admitted to holding him under.”

Howard’s lips pressed into a grim line. “Jesus.”

“She’s fourteen,” Mitchell added quietly.

Howard sighed. “Fourteen doesn’t change what she did. We’ll need to decide if she’s charged as an adult.”

Mitchell rubbed the bridge of his nose. “You think that’s the right call?”

“After hearing what you just told me?” Her voice hardened. “She planned it. She faked phone calls. She lured him home. That’s premeditation, Detective. She knew what she was doing.”

Mitchell looked down the hall through the observation window where Brittany sat alone, staring at the wall. “She’s just a kid,” he murmured.

Howard followed his gaze, her expression unreadable. “So was he.”

The next morning, the news exploded.

BOISE TEEN CHARGED WITH MURDER IN BROTHER’S DROWNING.

Reporters descended on the courthouse steps, microphones bristling as they shouted questions no one wanted to answer. “Was it premeditated?” “Will she be tried as an adult?” “What was the motive?”

The public’s outrage came fast and merciless. Talk radio callers fumed. Online commenters called her a monster. Editorials demanded “justice for Jeremy.”

Behind the scenes, Elizabeth Howard prepared her case with meticulous precision.

“She impersonated her mother,” Howard told her team, pacing the conference room. “She called two schools, checked him out, brought him home, ran a bath, and drowned him. That’s not a tantrum—that’s calculated.”

Her assistant, Marcus Webb, nodded grimly. “And afterward, she staged it to look like an accident.”

Howard stopped pacing. “We’ll petition to try her as an adult. If the judge agrees, this will be the youngest defendant in Ada County history to face first-degree murder charges.”

At the Ada County Juvenile Detention Center, Brittany’s life shrank to a schedule of bells, locked doors, and hollow silences.

Morning check-ins. Schoolwork. Group counseling. Dinner trays that all tasted the same.

She kept mostly to herself, speaking only when necessary. The other girls watched her warily. Some whispered that she’d killed her brother; others avoided her entirely.

Her counselor, Ms. Lawson, was one of the few who tried to reach her. A kind-eyed woman in her fifties, she would sit across from Brittany during sessions, hands folded gently in her lap.

“Do you think about what happened?” Lawson asked one afternoon.

“Every day.”

“What do you think about?”

Brittany stared at the gray floor tiles. “The water.”

“Do you think about Jeremy?”

A long pause. “I try not to.”

Lawson sighed. “You can’t heal from something you won’t face.”

Brittany’s eyes flicked up, cold and defiant. “Maybe I don’t deserve to heal.”

By midsummer, the court hearings began.

On July 21st, the packed courtroom fell silent as Judge Leonard Harrington entered, his black robe sweeping the floor. He was a man known for his no-nonsense approach—fair, but unflinching.

At the prosecution table, Elizabeth Howard stood tall, her crimson blazer a deliberate symbol of strength. At the defense table, attorney Patricia Reynolds placed a protective hand on Brittany’s shoulder.

The motion hearing lasted less than an hour. Howard argued that the crime’s premeditation justified adult charges. Reynolds countered that Brittany’s age and undeveloped brain demanded juvenile jurisdiction.

When Judge Harrington finally spoke, his voice carried the weight of stone. “Given the evidence presented—the calculated actions taken by the defendant prior to the crime—the court grants the prosecution’s motion. The defendant will be tried as an adult.”

A stunned murmur swept through the gallery.

Reynolds leaned toward her young client, whispering urgently, “Brittany, don’t react.”

But Brittany wasn’t listening. Her hands gripped the table as if it might hold her up.

Across the aisle, Charles and Heather Ringstaff sat together for the first time in months. Heather’s eyes brimmed with tears; Charles stared at the table, hollow.

Their daughter turned and looked at them.

Neither could meet her gaze.

The trial date was set for September.

During the months leading up to it, Howard’s team built a devastating case: forensic evidence, school records, the recovered text messages from Brittany’s shattered phone.

“I hate him. He’s going to be sorry he was ever born.”

Those words, timestamped at 8:15 a.m. on the day of Jeremy’s death, became the heart of the prosecution’s case.

Meanwhile, Reynolds worked tirelessly to humanize her client. She gathered expert witnesses in adolescent psychology, neuroscientists who could explain that a fourteen-year-old’s brain lacked the fully developed prefrontal cortex necessary for adult-level reasoning.

“She is not a monster,” Reynolds told reporters outside the courthouse. “She is a child who made a terrible, tragic mistake.”

But public sympathy was gone.

“Tell that to Jeremy’s parents,” one reporter snapped back.

In early September, Detective Mitchell sat at his kitchen table reviewing the case files one last time. The photographs, the transcripts, the text messages—they all painted the same horrifying picture.

Yet he couldn’t shake the image of the girl sitting in that interrogation room, emotionless until the moment she whispered, He broke my phone.

He’d seen killers cry before, but not like that. Not out of self-pity, not because they missed their victims, but because they’d finally realized their own life was over.

Mitchell rubbed his eyes and closed the file.

Whatever happened in court, there were no winners here.

September 27th, 2010.

The trial began.

The courthouse steps overflowed with reporters and onlookers. Inside, the atmosphere was electric and grim.

Brittany entered wearing a navy blazer and khaki pants chosen to make her appear older yet innocent. Her hair, now back to its natural blonde, was pulled into a ponytail.

She looked like any honors student.

But the indictment papers said otherwise: State of Idaho vs. Brittany Marie Ringstaff — Murder in the First Degree.

When the judge asked for her plea, her voice barely rose above a whisper.

“Not guilty.”

A ripple of whispers moved through the courtroom.

Elizabeth Howard stood, her expression hard. “The State intends to prove that on April 5th, 2010, the defendant, with premeditation and malice aforethought, lured her eight-year-old brother from school under false pretenses, drowned him, and attempted to conceal the crime.”

Her voice cut through the silence like a scalpel. “The victim’s blood, found beneath the defendant’s fingernails, tells a story that cannot be denied.”

When Howard returned to her seat, even the clicking of cameras had stopped.

Brittany sat motionless.

Her attorney leaned close. “You okay?”

Brittany nodded mechanically. But inside, something had begun to unravel.

Because for the first time since that terrible day, as she stared at the photo of her brother smiling from the screen beside the jury box, she understood—really understood—that he wasn’t coming back.

And she had made sure of it.

Part 3: The Trial

The oak-paneled walls of courtroom 3A seemed to swallow sound. Even the shuffling of jurors’ feet and the scrape of chairs felt hushed, reverent, as if the room itself understood the gravity of what was unfolding inside it.

The trial of State of Idaho vs. Brittany Marie Ringstaff had drawn national attention. News vans lined the streets outside. Camera flashes exploded like lightning each time the courthouse doors opened. Inside, the air was tense—too many people breathing too quietly for comfort.

At the front table sat Prosecutor Elizabeth Howard, her crimson blazer like a flare against the dark wood. Every movement she made was deliberate, her notes arranged in neat, color-coded stacks.

Across from her, Defense Attorney Patricia Reynolds sat beside her young client, whispering reassurance that sounded more like prayer.

And between them—literally and symbolically—sat the girl who had turned Boise’s quiet suburban calm into a national horror story.

Brittany Ringstaff, fourteen years old, small for her age, her blonde hair pulled tight into a ponytail. Her hands trembled slightly as she folded them in her lap.

The jury’s eyes were fixed on her. Some curious. Some horrified. None indifferent.

Opening Statements

Elizabeth Howard rose first. She didn’t use notes.

“On April 5th, 2010,” she began, her voice level but resonant, “eight-year-old Jeremy Ringstaff came home from school early, believing there was a family emergency. His sister told him their grandmother was in the hospital. He trusted her—because why wouldn’t he? She was his big sister.”

A photo of Jeremy flashed on the courtroom screen: a smiling boy with messy brown hair and a missing front tooth.

“Instead,” Howard continued, “Brittany led him home, ran a bath, and drowned him.”

The jurors shifted uncomfortably as she listed the evidence:

The fake phone calls impersonating her mother.

The internet searches: Can someone drown in a bathtub? How long does it take?

The text message to a friend that morning: I’m going to make him sorry he was ever born.

Jeremy’s blood found under her fingernails.

“She held him underwater for at least three minutes,” Howard said, her tone tightening. “And when it was over, she cleaned up, moved his body, and started the washing machine to destroy evidence.”

Her gaze swept across the jury box. “Ladies and gentlemen, this was not an accident. This was not a moment of childish impulsivity. This was murder—planned, deliberate, and executed by someone who knew exactly what she was doing.”

Howard sat.

The courtroom was silent except for the hum of the air conditioning.

Then Patricia Reynolds rose slowly, her tone soft, deliberate, almost maternal.

“No one here denies that Jeremy Ringstaff’s death was a tragedy,” she began. “But what happened that day cannot be understood through adult eyes. Because the person sitting beside me”—she gestured to Brittany—“is a child.”

She turned to face the jury directly. “Fourteen. That’s the age when your brain is still under construction. When impulse control and emotional reasoning are not yet fully developed. You’ll hear experts explain that. You’ll see scientific evidence that shows how a teenager’s brain works differently from yours or mine.”

Reynolds’ voice grew quieter, but steadier. “The prosecution will try to convince you that Brittany planned every detail, that she was a calculating killer. But what they won’t tell you is that teenagers can’t plan consequences—they only plan emotions. Brittany didn’t understand forever. She didn’t understand death. She acted out of anger, and by the time she realized what she’d done, it was too late.”

Her final words hung in the still air. “Don’t let a child’s worst mistake be the only thing that defines her life.”

The Evidence

Detective Adrien Mitchell was the first witness called.

The courtroom lights dimmed as he described the scene he had found that April afternoon—the quiet suburban home, the soaked hallway carpet, the little boy lying motionless outside the bathroom door.

He spoke clinically, but his voice wavered as he reached the details. “There was water splashed across the walls, droplets on the ceiling—consistent with a violent struggle. The victim was fully clothed. His body temperature and lividity suggested he’d been dead for roughly three hours.”

Howard asked, “Did anything strike you as inconsistent with an accidental drowning?”

“Everything,” Mitchell replied simply.

The prosecution displayed photos: the bruises on Jeremy’s shoulders, the scratches on his arms, the blood under Brittany’s nails.

When Howard asked what those marks indicated, Mitchell looked directly at the jury. “He fought back.”

At the defense table, Brittany stared down at her folded hands, unmoving.

Next came the forensic testimony.

Dr. Priya Chararma, Ada County’s chief medical examiner, walked the jury through the autopsy findings with professional precision.

“These bruises,” she explained, pointing to projected photographs, “are consistent with downward pressure applied by knees or hands while the victim was prone in water.”

“Could those bruises have come from resuscitation attempts?” Howard asked.

“No. CPR produces bruising centered on the chest. These are on the upper back and shoulders.”

“And the water in the lungs?”

“Approximately half a liter. That tells us he was conscious and breathing when submerged. He fought for at least two to three minutes before losing consciousness.”

The jurors shifted uncomfortably, one covering her mouth with her hand.

Howard nodded solemnly. “Thank you, Doctor.”

Patricia Reynolds declined to cross-examine. She simply said, “No questions,” her voice subdued. She knew the photos spoke louder than any argument.

The prosecution’s star expert, forensic specialist Derek Winters, followed. He showed microscopic photographs of blood spatter on Brittany’s sweatshirt cuffs.

“These droplets are aerosolized blood suspended in water,” he explained. “They result from thrashing during a struggle in liquid—not from touching a body after death.”

Howard asked, “So could these stains have come from her pulling him out of the tub after finding him?”

Winters shook his head. “No. The pattern is consistent with active participation in the drowning.”

Reynolds’ cross-examination was tense. “Is it possible, Mr. Winters, that these droplets were transferred by accident? For example, if Brittany tried to revive her brother?”

Winters didn’t hesitate. “No, ma’am. The distribution pattern proves she was in the water while the struggle occurred.”

A ripple of whispers passed through the gallery.

Reynolds sat down slowly, her pen unmoving.

The Psychology of a Child Killer

The courtroom grew even quieter when Dr. Elaine Winters, a forensic psychologist, took the stand.

Her role was to explain what might drive a teenager to kill a sibling—and whether Brittany’s mind could have understood the permanence of her actions.

Howard guided her gently through the findings. “Dr. Winters, based on your review of the case, did Brittany Ringstaff demonstrate signs of planning?”

“Yes,” the psychologist replied. “She made multiple phone calls impersonating her mother, created a cover story about a family emergency, and researched methods of drowning. These behaviors show sustained intent, not impulse.”

“And what about her understanding of death?”

“At fourteen, children understand that death is permanent. Unless there’s cognitive impairment, they know that causing someone to stop breathing will end their life. Forever.”

Howard let that last word linger before nodding. “No further questions.”

Reynolds rose for cross-examination, her tone gentle but firm.

“Dr. Winters, you would agree that adolescence is marked by poor impulse control?”

“Yes.”

“And by heightened emotional response?”

“Yes.”

“So is it fair to say that while Brittany might have understood that death is permanent, she might not have fully processed what that meant in the heat of emotion?”

Dr. Winters paused, then nodded. “That’s possible. But the deliberate steps she took indicate she had time to cool down and reconsider. And she chose not to.”

Reynolds nodded slowly. “Thank you, Doctor.”

The most heart-wrenching moment came when Madison Taylor, Brittany’s best friend, was called to the stand.

Madison was sixteen, thin, trembling, clutching a tissue in both hands.

Howard approached gently. “Madison, did Brittany ever talk to you about her brother?”

“Yes,” Madison whispered. “She said he was annoying. That her parents always took his side.”

“Did she ever say anything that worried you?”

Madison hesitated. “She said… she wished he would disappear.” Her eyes filled with tears. “But I thought she was just being dramatic. She always said stuff like that when she was mad.”

“Did she text you the morning of April fifth?”

Madison nodded, her voice cracking. “Yeah. She said, ‘He’s going to be sorry he was ever born.’ I didn’t think she meant it.”

Howard’s voice softened. “If you had thought she meant it, what would you have done?”

“I would’ve told someone,” Madison sobbed. “I would’ve stopped her.”

When Reynolds cross-examined, she did so gently. “Madison, you said Brittany often exaggerated, right?”

“Yes.”

“So you never took her threats seriously?”

“No. Never.”

“Because you saw her as… a normal teenager?”

Madison sniffled. “Yeah. She just got mad sometimes. Like everyone else.”

Reynolds nodded. “Thank you.”

But the damage was done. The jurors had heard the text message. They had seen the pattern. The image of a girl who “just got mad sometimes” was being replaced by something colder.

Something deliberate.

By the time the prosecution rested, even the reporters had stopped scribbling. Everyone in the room seemed to feel the same unspoken thought: they had witnessed something unbearably sad.

Not a monster, not a sociopath—just a child who’d crossed a line she could never uncross.

The Defense’s Turn

When the defense began its case, Reynolds’ strategy was clear: not to deny the act, but to explain it.

Dr. Robert Chen, a child psychiatrist, testified that Brittany’s brain development limited her ability to control anger and foresee long-term consequences.

“The adolescent brain is ruled by the amygdala—the emotional center,” he explained. “The rational part, the prefrontal cortex, is still under construction. This means teenagers can plan in the short term—like sneaking out—but they don’t fully grasp the permanence of actions like death.”

Howard’s cross-examination was razor sharp. “Dr. Chen, does ‘under construction’ mean incapable?”

“No, but—”

“Did Brittany impersonate her mother on two phone calls?”

“Yes.”

“Did she check her brother out of school?”

“Yes.”

“Run a bath?”

“Yes.”

“Wash her clothes afterward?”

“Yes.”

Howard turned to the jury. “Those are not the actions of someone acting on impulse. Those are the actions of someone covering up a crime.”

Reynolds tried to counter with testimony about adolescent rehabilitation potential, but Howard’s case had already anchored itself in the jurors’ minds.

As the trial neared its end, Reynolds asked the judge to allow Brittany to make a statement in her own defense.

The courtroom held its breath as the girl stood.

Her voice was thin, shaking. “I didn’t mean for him to die,” she said. “I was just so mad. He broke my phone, and Mom grounded me. I wanted him to know what it felt like. But I didn’t mean it. I didn’t think he would die.”

Her eyes searched the gallery until they found her parents. Heather was crying silently. Charles sat rigid, staring straight ahead.

“I’m sorry,” Brittany whispered. “I miss him every day.”

Then she sat down, trembling, as reporters scribbled frantically.

When the defense rested, Judge Harrington adjourned for the evening. Outside, the courthouse steps erupted into chaos—reporters shouting questions, protesters holding signs reading “Justice for Jeremy” and “Kids Are Not Adults.”

Inside, the courtroom emptied slowly. Only Detective Mitchell lingered, standing in the aisle staring at the empty defense table.

He thought of Brittany’s last words, her small voice trembling as she said I didn’t think he would die.

And for the first time since the case began, he found himself wondering if that might actually be true.

Part 4: The Verdict

Morning sunlight filtered through the high windows of courtroom 3A, catching dust motes that floated like tiny ghosts above the jurors’ heads. It was October 12th, 2010 — the thirteenth day of State of Idaho vs. Brittany Marie Ringstaff.

Everyone knew what was coming.

The prosecution and defense had spent nearly two weeks fighting over whether Brittany was a calculating killer or a broken child. Now, after mountains of evidence and hours of testimony, all that remained were two closing arguments — and a verdict that would determine not only the fate of one teenage girl, but the moral boundaries of an entire community.

The air inside the courtroom was heavy, the kind of stillness that makes even breathing feel intrusive. Reporters filled the back rows. Brittany’s grandparents sat behind her, faces drawn and pale. Across the aisle, her parents — separated by both grief and guilt — sat stiff and unmoving behind the prosecution table.

Judge Leonard Harrington took his seat precisely at nine o’clock. His expression was carved from stone.

“This court will now hear closing arguments,” he said, his deep voice echoing through the room. “The prosecution may proceed.”

Elizabeth Howard’s Closing Argument

Prosecutor Elizabeth Howard rose from her chair, smoothed the front of her crimson blazer, and stepped before the jury box. The air seemed to tighten around her as she began.

“When this trial began,” she said evenly, “I promised you that the evidence would show a deliberate act — not a mistake, not an impulse, but a plan. And now, after everything you’ve heard, that promise has been kept.”

She gestured to the screen, where the timeline of April 5th appeared in stark white letters:

8:15 a.m. — Brittany texts her friend: He’s going to be sorry he was ever born.

8:45 — Calls her school pretending to be her mother.

9:30 — Calls Jeremy’s school with the same lie.

10:15 — Signs him out under false pretenses.

11:00 — Buys candy and soda.

11:30 — Runs a bath.

“And by two o’clock,” Howard said, her voice tightening, “Jeremy Ringstaff was dead.”

She walked closer to the jury, lowering her voice. “Eight years old. Fully clothed. Water in his lungs. Bruises on his back from where his sister’s knees pinned him down.”

Several jurors looked away.

Howard didn’t stop. “She researched how to drown someone. She planned how to make it look like an accident. And after killing him, she tried to erase what she’d done — washing her clothes, moving his body, fabricating stories.”

She pointed toward the defense table where Brittany sat motionless, staring at her folded hands. “That is not the behavior of a child who lost control. That is the behavior of someone who knew right from wrong — and chose wrong.”

Her tone softened. “I know what you’re thinking. She’s only fourteen. You’ve seen her sitting there, small and quiet, and you’ve thought, She doesn’t look like a killer. But that’s exactly why this case matters. Because evil doesn’t always look like what we expect. Sometimes, it looks like a child in a school uniform holding a soda and a candy bar.”

She turned back to the photo of Jeremy on the screen — the same school portrait they’d all seen dozens of times now: bright grin, chipped tooth, the innocence of a life that would never see adulthood.

“This boy deserved to grow up. To play soccer, to go to high school, to become the paleontologist he dreamed of being. Instead, his life ended in a bathtub because his sister was angry about a broken phone.”

Howard paused, letting the silence stretch until it hurt.

“The law doesn’t care about how old you are when you plan and execute a murder,” she said quietly. “The law cares about what you did. And Brittany Ringstaff planned. She deceived. She killed.”

Her voice rose just slightly for the final line. “For Jeremy’s sake — for justice — you must find her guilty of first-degree murder.”

When she sat down, you could have heard a pin drop.

The Defense’s Closing Argument

Patricia Reynolds rose slowly, taking her time as she approached the jury. Her face was drawn but calm, her hands steady on the podium.

“What happened to Jeremy Ringstaff is unspeakable,” she began softly. “A little boy is gone. His family is broken. His sister will carry this burden for the rest of her life.”

She looked directly at the jurors, her tone quiet but firm. “But before you deliver judgment, I ask you to remember this: Brittany is not a monster. She is a child.”

Reynolds gestured gently toward her client. “Fourteen years old. A brain still under construction. You heard the experts — her ability to think rationally, to understand long-term consequences, was not yet fully developed. The very science of neuroscience tells us she was wired for emotion, not logic.”

She moved closer, her voice trembling just enough to sound human. “You’ve seen the text messages, the internet searches, the lies. They look like planning to adult eyes. But to a fourteen-year-old, they’re fantasy — angry words typed in a rush of emotion, curiosity without comprehension.”

Reynolds took a deep breath, then continued. “The prosecution asks you to treat Brittany like a grown woman who made a cold calculation. But you’ve seen her. You’ve watched her sit here for two weeks. Does she look like a calculating murderer? Or does she look like a scared child who made an unthinkable mistake?”

Her voice cracked on the last words. “Justice does not mean vengeance. Justice must have mercy. And mercy begins with understanding the difference between a child and an adult.”

She turned toward the judge’s bench, then back to the jury. “Hold her accountable, yes. But not as a monster. As a child who needs help, not life in prison.”

Her closing words were barely above a whisper. “Please. Don’t let this child’s life end the way her brother’s did — too soon.”

The Jury Deliberates

At 2:15 p.m., Judge Harrington gave the jury their instructions. They filed out silently, a dozen faces heavy with exhaustion and dread.

Outside, the courthouse lawn was crowded with protestors. Some carried signs reading JUSTICE FOR JEREMY. Others held ones that said CHILDREN AREN’T ADULTS.

Inside, the minutes dragged like hours.

Brittany sat beside her attorneys, motionless, staring straight ahead. Every so often she glanced at the door, as if half-expecting Jeremy to walk through it, still alive, still laughing.

Four hours and twenty-seven minutes later, the bailiff knocked on the door.

“The jury has reached a verdict.”

A murmur rippled through the courtroom.

Heather Ringstaff gripped Charles’s hand so tightly his knuckles turned white. Reporters scribbled frantically as cameras clicked.

Brittany didn’t move.

The Verdict

The foreman, a middle-aged man in a gray suit, handed the verdict form to the bailiff, who passed it to Judge Harrington. The judge’s face remained unreadable as he scanned the paper, then handed it back.

The bailiff stood and read aloud.

“In the matter of the State of Idaho versus Brittany Marie Ringstaff, on the charge of murder in the first degree — we, the jury, find the defendant guilty.”

A collective gasp filled the room.

Heather let out a low, broken sob. Charles stared at the table, his shoulders shaking.

Brittany’s face went white. Her lips parted, but no sound came.

The judge’s gavel came down once. “Order.”

Reporters rushed for the doors. The world outside would know within minutes.

Inside, Brittany turned slowly toward her parents, eyes wide, desperate. “Mom,” she whispered. “Dad.”

Neither one could look at her.

Sentencing

Two weeks later, the same courtroom filled again. This time, there was no question, no deliberation — only the final act.

Brittany entered in shackles, escorted by two deputies. She looked smaller now, thinner. The defiance was gone.

Judge Harrington began by acknowledging the tragedy that had torn the Ringstaff family apart. “This is one of the most difficult cases this court has ever faced,” he said. “It pits the science of adolescence against the realities of deliberate violence.”

He allowed the victim’s family to speak.

Charles stood first. His voice was rough but steady. “Jeremy was the light of our house,” he said. “He was my boy. And Brittany… she was my girl. I can’t understand how both my children could be gone in the same day. I don’t know how to forgive her, but I also don’t know how to hate her. I just want my son back, and I can’t have him.”

Heather couldn’t speak. A victim advocate read her written statement: “Two children left my home that morning. None came back. I can’t comprehend what my daughter did, or why. I only know that I live every day in silence that used to be filled with laughter.”

When it was Brittany’s turn, she stood slowly, trembling.

Her voice was barely audible. “I’m sorry,” she said. “I didn’t mean to hurt him. I was angry. I thought if I scared him, he’d leave me alone. I didn’t think he’d really die.” Her voice broke. “I miss him every day. I wish it was me instead.”

The judge listened in silence, then leaned forward. “Ms. Ringstaff, I have reviewed every report, every evaluation, every word said in this courtroom. I acknowledge the science of adolescence. I acknowledge that you were fourteen when you took your brother’s life. But I also acknowledge your actions — deliberate, deceitful, and devastating.”

He paused, his voice lowering. “You lured your brother home. You held him underwater while he fought for his life. And afterward, you tried to hide what you’d done.”

The room held its breath.

“It is the judgment of this court that you be sentenced to life imprisonment, with the possibility of parole after thirty-five years.”

Brittany’s mouth opened slightly. “What?”

Judge Harrington’s voice grew harder. “Given the calculated nature of this crime, you have shown a callousness that society cannot safely accommodate. You’ll die in prison unless you use the next three decades to understand what you did.”

The words struck like thunder.

Brittany’s composure shattered. “I’m only fourteen!” she cried, her voice echoing through the courtroom. “It’s not fair! I’m only fourteen!”

Her sobs turned to screams as deputies led her away. “It was just a phone! I didn’t mean it! I want my mom! I want to go home!”

Heather covered her face as the sound of her daughter’s cries filled the courtroom — a child’s voice echoing from behind iron doors.

And then she was gone.

Outside, the headlines screamed the next morning:

“YOU’LL DIE IN PRISON”: JUDGE GIVES 14-YEAR-OLD LIFE SENTENCE FOR KILLING BROTHER

Some hailed the verdict as justice. Others called it barbaric.

But inside the walls of the Ada County jail, where the teenage girl sat alone in her gray uniform staring at the floor, there were no headlines.

Only silence — and the echo of her own words.

“It’s not fair. I’m only fourteen.”

Part 5: The Aftermath

Five years passed.

The courtroom that once overflowed with reporters and outrage had long returned to routine traffic violations and domestic disputes. But for the people whose lives had been shattered by that trial, time had done little to dull the ache.

In the Idaho Correctional Institution for Women, behind fences strung with razor wire, inmate #F41822—Brittany Marie Ringstaff—began her life sentence at just fourteen years old. She was the youngest prisoner ever processed at the facility.

Her first weeks were a blur of noise, fear, and disbelief. Prison wasn’t made for children. The walls were gray, the uniforms stiff, the faces around her hard and watchful. Guards didn’t speak to her unless they had to. Older inmates stared with curiosity—some with pity, others with quiet disgust.

At night, lying in a cell built for two but assigned to one, Brittany listened to the echoes of keys and footsteps in the hall. She pressed her hands over her ears to block out the memory of water splashing, of her brother’s voice crying out one last time.

Sometimes, she whispered into the dark, “I’m sorry,” over and over, until her throat hurt.

But the walls never answered back.

Inside the System

Because of her age, prison officials placed Brittany in a separate wing reserved for juvenile offenders tried as adults. The facility housed six other teenagers, all convicted of violent crimes.

They attended classes taught by correctional educators, did chores, and took part in counseling sessions. The counselors tried to treat them like students instead of inmates—but the guards never forgot what they were.

Brittany was quiet. Withdrawn. She followed rules, kept to herself, and rarely spoke unless spoken to. Her file filled quickly with notes: Compliant. Intelligent. Exhibits low empathy but strong academic aptitude.

By sixteen, she had completed her high school coursework. Her counselor suggested college correspondence classes. Brittany chose psychology.

When asked why, she replied simply, “I want to understand what’s wrong with me.”

In the evenings, she worked in the prison library, sorting paperbacks and logging checkouts in neat handwriting. She read obsessively—books about brain development, juvenile crime, trauma. Anything that might explain how a fourteen-year-old could destroy her family in one morning.

The staff noticed. “She’s… different,” one officer told the warden. “Quiet, but focused. She’s not like the others.”

The warden just sighed. “They all start that way.”

The Parents Who Remained

Outside those walls, Charles and Heather Ringstaff no longer lived on Aspen Ridge Drive. The house had been sold the year after the sentencing, the cheerful blue shutters replaced by gray ones.

Charles had moved north to Oregon, where he remarried quietly. He never spoke of Brittany or Jeremy to his new family. When reporters contacted him for follow-up stories, he declined every interview.

Heather stayed in Boise. She couldn’t bring herself to leave the city where both her children had lived—and died.

In 2012, she founded the Jeremy Ringstaff Foundation for Conflict Resolution, an organization dedicated to helping families identify and defuse sibling conflict before it escalated into violence.

She spoke at schools, community centers, even churches. Her message was simple but haunting: “We never think it could happen in our house. But it can.”

Heather visited Brittany once a month. The first time she came, she could barely look at her daughter. The second time, she could barely speak.

By the fifth visit, she finally asked the question she’d avoided for years.

“Why, Britt? Why him?”

Brittany stared at her hands for a long time before whispering, “Because I thought you loved him more.”

Heather broke down sobbing across the table. It was the first time either of them had cried in front of the other since the trial.

From that day on, Heather came more regularly. Sometimes they talked. Sometimes they just sat in silence. But the visits became a ritual neither could give up.

“I have to believe there’s still something left to save,” Heather told a reporter once. “If I don’t, then I’ve lost both my children forever.”

A Nation Watching

The Ringstaff case had shaken Boise, but its ripples reached far beyond Idaho.

Law schools debated it. True-crime podcasts analyzed it. Television dramas fictionalized it. For a decade, the case was cited whenever prosecutors sought to try juveniles as adults.

In 2013, State Senator Rebecca Daniels introduced the Ringstaff Act, a bill that would allow “blended sentencing” for juvenile offenders—serving time in youth facilities until twenty-one, then reassessing whether adult prison was necessary.

The law passed by a narrow margin.

At the signing, Daniels said, “The Ringstaff case taught us something painful: children can commit terrible crimes. But we must still remember—they are children.”

For some, the reform came too late. But for others, it was the first step toward mercy.

The Girl Who Grew Up Behind Bars

By nineteen, Brittany had become a model inmate. Her record was spotless. She tutored other prisoners in reading and math, wrote essays for a prison newsletter, and volunteered in restorative justice workshops.

Her counselor noted, She demonstrates insight into her actions and expresses genuine remorse.

Still, the nightmares persisted.

Sometimes she woke screaming, water choking her throat. Other nights, she dreamed of Jeremy—alive, laughing, asking if she wanted to play soccer. She’d wake crying, whispering his name into the dark.

On her twentieth birthday, Heather brought a small photo to visitation: Jeremy at eight years old, smiling wide, missing tooth and all.

Brittany stared at it for a long time before whispering, “He would’ve been eighteen now.”

Heather nodded silently, tears in her eyes.

Brittany touched the photo with trembling fingers. “He’d be in college, right? Maybe paleontology. He always loved dinosaurs.”

Heather smiled faintly. “He’d be proud of you for studying, Britt.”

Brittany’s voice broke. “He shouldn’t have to be proud of me. He should just be here.”

In 2014, Brittany’s defense team filed an appeal, citing the Supreme Court’s Miller v. Alabama decision, which ruled mandatory life sentences for juveniles unconstitutional.

The Idaho Supreme Court agreed to hear the case but ultimately upheld her sentence, noting that it included the possibility of parole.

The decision was split 3–2.

The dissenting justices argued that “a parole possibility after thirty-five years is functionally a life sentence for a fourteen-year-old,” calling it “a violation of evolving standards of decency.”

The majority opinion, however, held firm: “The calculated nature of the crime and subsequent attempts at concealment justify the sentence imposed.”

When the ruling reached Brittany in prison, she didn’t cry or scream. She just folded the paper neatly and said, “Okay.”

To her cellmate, she murmured later, “I guess I’ll be fifty when they even think about letting me out.”

By 2020, Brittany was twenty-four. The world had moved on, but Boise still remembered. On the tenth anniversary of Jeremy’s death, the Idaho Statesman published a reflective piece:

“Ten Years Later: The Case That Changed Idaho.”

For the first time, Brittany agreed to a written interview with the paper.

Her answers were short, thoughtful, and hauntingly mature:

“I think about him every day.”

“I didn’t understand what forever meant when I was fourteen.”

“Now I do.”

The article described her as “a pale, soft-spoken young woman with clear blue eyes and a quiet intelligence that hints at who she might have become under different circumstances.”

She was halfway through a psychology degree by correspondence, specializing in adolescent development and trauma.

“I’m not studying this to excuse what I did,” she wrote. “I’m studying it because I want to understand why people like me do what we do—so maybe someone else doesn’t.”

Today, the Ringstaff Foundation funds school programs across Idaho teaching conflict resolution to children as young as six. At Hillside Elementary, a garden blooms in Jeremy’s memory, centered around a small bronze dinosaur sculpture.

Children leave drawings there—dinosaurs, soccer balls, and messages scrawled in crayon: We miss you, Jeremy.

Each spring, the school holds “Peacemakers Week,” where students learn how to talk through anger before it becomes violence.

Heather attends every year. She tells Jeremy’s story. Sometimes, she mentions Brittany’s too. “Both my kids taught me something,” she says. “One taught me joy. The other taught me how dangerous silence can be.”

In a glass display case near the school entrance sits a framed quote from Brittany’s 2020 interview:

“I didn’t understand forever when I was fourteen. Now I do.”

In the stillness of her cell one evening, Brittany sat by the narrow window, watching the sun sink over the gray prison yard. The light turned the concrete gold for a few fleeting minutes, then faded.

She thought of Aspen Ridge Drive. Of the house with blue shutters. Of her mother’s voice calling her name for dinner.

Of Jeremy’s laugh echoing from the yard as he kicked a soccer ball.

She could almost hear it sometimes—soft, distant, like the echo of a life that had stopped mid-sentence.

“I’m sorry,” she whispered into the empty air. “I’ll say it every day, Jeremy. I’ll say it until I can’t anymore.”

Then she picked up her worn psychology textbook and began to read, the pages turning softly in the quiet.

Somewhere outside, the world kept moving—new children laughing, new siblings fighting, new families living unaware of how fragile love could be.

But in that cell, time stood still.

And though she would one day be eligible for parole, Brittany knew there were some prisons she’d never leave.

THE END

News

CH2 – “The Billionaire Got a Wrong Call at 2AM — He Arrived Anyway, and Single Mom Whispered, ‘Stay.’”…

Part 1: The harsh ring of Jack Morgan’s phone split the stillness of his penthouse like a blade. 2:17 a.m….

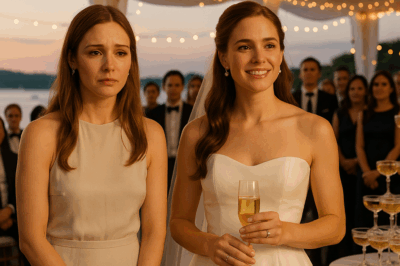

CH2 – During Sister’s Wedding, They Called It “Just Gaming” — My Industry Award Changed Everything…

Part One – The Toast The string quartet played something elegant and old-fashioned — maybe Vivaldi — as waiters in…

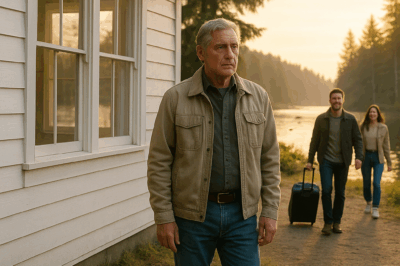

CH2 – My Nephew Wanted To Turn My Lakefront Cottage Into His Airbnb, So I Prepared A “Surprise.”…

Part One The pen made a faint scratching sound as Jennifer Pierce signed the last page of the deed. “Congratulations,…

The Day the Light Went Out — A Mother’s Letter to Her Little Boy.

Posted October 29, 2025 It has been 115 days since her world went silent. One hundred and fifteen sunrises without…

Tom Cruise Breaks His Silence: Inside the Secret Meeting That Ignited Hollywood’s Moral Uprising — Cruise and Mel Gibson Expose the Industry’s “Cruel Game” After Charlie Kirk’s Trag!c Event — Their Words Have Shaken Tinseltown, and a Moral Line Has Been Crossed!

Hollywood is no stranger to chaos. From studio scandals to leaked recordings, few places on Earth thrive more on controversy….

He walked out of the wings like a memory stepping into the light — Jason Gould, the son she had once sung to in whispered lullabies and tucked inside every lyric of love she ever wrote. At first, the audience didn’t understand; they only saw a tall, graceful man with her same eyes, her same calm smile — reflections of Barbra Streisand herself.

Barbra & Jason Gould’s Surprise “Evergreen” Duet: A Mother-Son Moment That Silenced the Hollywood Bowl In the velvet hush of…

End of content

No more pages to load