The smoke was the wrong color.

Captain James Hullbrook knew it the instant the plume blossomed up through the shattered pines—thick, curling, vivid orange against the gray November sky.

Field Manual FM 21-50 was clear. Every officer who’d made it through stateside training could have recited the code in their sleep.

White smoke: conceal movement.

Yellow smoke: mark friendly positions.

Red smoke: casualties, evacuation needed.

Orange smoke: enemy position identified. Do not fire.

Do not fire.

He lowered the binoculars a fraction and watched the orange cloud drift over the valley floor, snagging in the broken branches, spreading like a stain across the Hurtgen Forest.

He was not marking an enemy position.

He was marking empty ground.

“Sir,” said Lieutenant Martin Cross beside him, breath steaming from beneath his helmet, “that’s a hell of a lot of orange.”

“Good,” Hullbrook said. “I want Steiner to see it from his morning coffee.”

He raised the glasses again, elbows dug into the lip of the frost-rimmed foxhole, and scanned the forest three hundred meters west.

“Where are you…” he murmured.

The Hurtgen did not offer easy answers.

The forest looked the same in every direction: slopes of black earth and snow, tree trunks shredded by artillery, branches blown off and hanging like broken limbs. Smoke from earlier barrages clung to the canopy, turning daylight into a vague, smoky twilight.

Beneath the trees, German infantry were moving.

He could hear them more than see them. Bootsteps muffled in pine needles. An occasional scrape of metal on bark. A low, guttural word that might’ve been an order or a curse.

Elements of the 275th Infantry Regiment. Once full strength—over two thousand men. Battle-hardened veterans who’d fought at Normandy, pulled back through France under fire, and now clung to the line at Germany’s western border like cornered animals.

James Hullbrook had exactly 143 men left in Easy Company, 2nd Battalion, 28th Infantry Division.

His ammo was running low. His radios had been dead to battalion for six hours. He had no artillery he could call, no air support that could see through the trees even if they showed up.

And he was about to try to capture an entire German regiment using nothing but colored smoke and the enemy’s own training.

He was pretty sure there wasn’t a field manual section for this.

“Captain?” Cross said quietly. “This… this is really happening?”

“You were there in the bunker,” James said. “You voted for crazy. This is crazy.”

He adjusted the focus on the binoculars. Orange smoke at 472, north of their true line. Another plume was starting to puff at 476—Sergeant Torres doing his part in phase one. Gentle November breeze would carry both signals just enough.

Hullbrook’s knuckles were white on the binoculars’ cold metal.

If this worked, West Point would have to invent new lectures.

If it didn’t, Easy Company would simply stop existing.

He thought about his old life for half a heartbeat—a chalkboard in Scranton, Pennsylvania; kids groaning over algebra homework; Friday night basketball games in a warm gym—and then pushed it away. That life belonged to a man who hadn’t walked into the Hurtgen.

The man here was different. Or had to be.

The Hurtgen changed everyone.

The Forest That Ate Armies

Officially, the maps called it the Hürtgenwald.

The men who went into it called it other things. The meat grinder. The green hell. The death forest.

Das Wald, the Germans said. The forest, as if that word alone carried enough of a curse.

The numbers were obscene even by the standards of 1944: between September and December, American forces would suffer around thirty-three thousand casualties in that stretch of woods trying to push the front line a few miserable kilometers closer to the Rhine.

In some companies, casualty rates topped 120 percent—more dead and wounded than had ever been on the roster, replacements feeding in and dying so fast the clerks couldn’t keep up.

The forest itself fought.

Ancient fir trees grew so thick that daylight barely touched the ground. German observers had dug platforms high up, invisible among the branches, with clear views down into the valleys where Americans had to move. The Germans could see without being seen.

Artillery shells, instead of plunging into earth where their blasts could be swallowed, struck the canopy. Tree bursts detonated above head height, shredding men with wood splinters and steel fragments both.

Every logging trail turned into a bog when churned by tanks and trucks. Vehicles sank, stuck, then burned when hit.

The forest floor hid mines: S-mines that leapt waist high before exploding, Teller mines that turned halftracks into scrap. Booby traps hung from trees, wired to grenades or rigged to trip flares that brought down mortar rain.

Standard infantry tactics—flank, fix, maneuver, mass firepower—failed here. The trees blocked lines of sight. The ground channeled movement down narrow draws that the Germans had already zeroed with machine guns and mortars.

Artillery support was a mixed blessing. The shells killed Germans in their bunkers and Americans in their foxholes with equal enthusiasm. Tree bursts cared nothing for uniform color.

Air support? Might as well have been on the moon. Pilots couldn’t see targets through the canopy. Bombing the forest was like punching fog.

Radio signals fought the trees too. Static and interference turned battalion commands into garble. Company commanders stepped under the branches and vanished not just from the sky’s view, but from the chain of command.

The hurtgen offensive turned into a slog where objectives had meaningless names—Hill 400, Ridge 5, Grid 472—and cost more lives than any map square could justify.

In a headquarters tent somewhere far back, Lieutenant General Courtney Hodges looked at his own maps and refused to call it off. German forces tied down in the Hurtgen, he argued, couldn’t counterattack elsewhere. The forest was a terrible place to die, but it was buying time for something bigger.

That logic did not help the men actually in the forest.

At the company level, the strategy translated into one bitter phrase:

“In the Hurtgen, you don’t take ground. You trade lives for square meters of frozen hell.”

The Teacher Who Didn’t Look Like a Captain

If you’d seen Captain James M. Hullbrook on a sidewalk in Scranton in 1941, you’d have guessed insurance salesman or math teacher. You would have been correct on the second.

He was twenty-seven years old in 1944, but the war had scraped the softness from his face. Under the stubble and grime, under the lines beginning to etch around his eyes, you could still see the teacher: thoughtful, patient, more comfortable with chalk than with a Colt .45.

He had not gone to West Point. He had not run around on some Ivy League campus in an ROTC uniform.

He’d gone to a state teachers’ college, taken an interest in algebra and geometry, and wound up in front of a blackboard at Scranton Technical High School. He’d coached junior varsity basketball in the evenings, taught kids to run pick-and-rolls and not be afraid of trigonometry.

When Pearl Harbor hit, he’d watched his seniors enlist. Some of his colleagues went into the service as well. He’d stayed, at first. There were other ways to serve, the draft board said. But as the war grew bigger in the newspapers and on the radio, the idea of staying home and sending other people’s sons off gnawed at him.

So he put his name in.

Sixteen weeks at Officer Candidate School at Fort Benning taught him to march and fire and memorize field manuals. His evaluations read “solid,” “competent,” “not especially distinguished.”

Under “special skills,” he listed “mathematics” and, on a whim, “chess.”

Under “combat experience prior to commission,” the form stayed blank.

He arrived in France in September ’44 as a replacement lieutenant, just another fresh-faced officer stepping off a boat into the debris of Operation Overlord’s fading glory. The lightning race across France had slowed into trench lines and hedgerows by then.

Within three weeks, attrition did what no exam had done. His platoon leader got hit; James moved up. Within five weeks, a tree burst took out Captain Richard Morrison while he stood outside a makeshift command post talking to battalion on the radio. Shards of wood and steel had no respect for rank.

The men of Easy Company looked around, looked at the battlefield promotion chart, and realized that the new CO was going to be the quiet guy from Scranton who’d been in combat for just over a month.

Corporal Anthony Duca, the company clerk, would later say, “Some guys were placing bets on how long he’d last. Smart money said seventy-two hours. He didn’t look like a fighter. He looked like somebody’s teacher.”

They weren’t wrong.

He was somebody’s teacher.

He was also learning faster than any college course had ever forced him to.

Noise on the Ridge

His first real test came on November 15, on a nameless ridge that might as well have been the edge of the earth.

Easy Company was clinging to their foxholes, rifles pointed into a fog that smelled like cold and cordite. German mortars had bracketed their position all morning, feeling out the angles, walking shells in closer. Machine-gun fire probed the tree line. Somewhere deeper in the forest, a whistle blew, and the firing stopped.

Cross, then still the executive officer, had crawled over to Hullbrook’s hole. “Sir, if they come again in strength, we’re going to have to pull back. We’ve got no depth. One push and they’ll roll right over us.”

He wasn’t wrong. Pulling back—fighting withdrawal—was what the book prescribed when you were outnumbered and getting hit hard.

James had looked down the ridge, through the broken trunks to the ground they’d taken two days earlier.

Forty-three casualties to take this bit of forest. Forty-three lives to move the line maybe a hundred yards.

“Withdraw where?” James asked. “We give this up, they’ll just lay in for the next attack. And we’ll have to pay for the same trees twice.”

“And get killed staying, sir,” Cross said bluntly.

James thought of chess.

“You don’t always trade pieces,” he said. “Sometimes you convince the other guy you’ve got a queen lurking where you don’t.”

He’d been watching the Germans, memorizing the pattern of their assaults. They advanced methodically, in squads and platoons, hitting one spot to draw fire, then sidestepping for the main push. Conserving strength. Fighting a patient war.

They were expecting Americans to respond by the book: hold, fire, fall back when pressured.

What if the “book” made them hesitate?

He grabbed the field phone and barked an order down the line that made the NCO on the other end swear.

“Everyone on this net, listen up. When I give the signal, I want you to make noise. All of you. Fire, shout, bang your entrenching tools on trees—make this ridge sound like we’ve got a battalion up here. But you hold fire until I say otherwise. You got me?”

“Sir, are you out of your—”

“You got me, Sergeant?”

A pause. “Yes, sir.”

The next German probe began with the usual cautious advance. James peered through his scope and saw dark shapes moving between trees.

“Now,” he said.

The ridge erupted.

Rifles cracked—not aimed at anything specific, just firing at the sky, at the ground, into the fog. Men shouted. Someone pounded a mess tin against a tree rhythmically. A BAR cranked off a full twenty-round burst in one roar.

To the Germans, down below, it sounded like a full company—or more—letting loose. The echoes multiplied the chaos. What was a slim line of foxholes became, in sound, a wall.

The German squad froze, then pulled back. He could imagine their platoon leader thinking, We misjudged. That’s more men up there than we thought. We’ll need more support.

In that pause, James shifted his real firepower.

“Machine-gun sections, shift to left and center sectors,” he ordered. “They’ll try to go around. Let’s already be there when they do.”

When the attack resumed, with heavier pressure on the flanks, it walked straight into freshly sited .30-caliber guns. Germans broke cover and crumpled. The ridge held.

Later, in the muddy calm, Private Robert Chen looked at his CO with new respect.

“That’s when we realized the captain wasn’t following the book,” Chen would say. “He was rewriting it. He’d studied how the Germans were fighting, not how we were supposed to fight them. He said something I never forgot: ‘Chess isn’t about knowing the rules. It’s about making your opponent play your game.’”

By the next morning, November 16, James sat in a captured German bunker with light from the doorway slanting across the concrete walls, reading a different kind of book.

It was about to give him his craziest idea yet.

Orange Means Don’t

The bunker still smelled like burned powder and fear.

German posters—with neat gothic script and charts of formations—hung askew where grenades had blown out chunks of the walls. A smear of something dried and dark stained one corner. Someone’s kit lay abandoned under a cot.

James sat on an overturned ammunition crate with three documents spread out in front of him.

On the left, his own FM 21-50: Tactical Employment of Smoke.

In the center, a captured German infantry manual, edges singed but the print intact.

On the right, his notebook, pages damp, filled with his cramped math-teacher handwriting: sketches of terrain, notes on German patrol patterns, casualty tallies.

Torres, Kowalski, and O’Brien stood near the doorway, watching the tree line. Cross and Lieutenant James Walsh leaned over the crate, faces shadowed by their helmets. The men looked tired in a way that had nothing to do with sleep deprivation and everything to do with the forest.

“Right here,” James said, tapping a paragraph in the German manual. “Translation courtesy of Corporal Burkowitz.”

He cleared his throat and read, “ ‘Enemy smoke signals are to be interpreted according to Allied doctrine. Orange smoke indicates friendly or enemy positions designated for artillery engagement. Maneuver units are to avoid advancing through these marked areas to prevent compromise of artillery targeting and friendly-fire incidents.’”

Walsh frowned. “That’s… that’s our system.”

“Right,” James said. “Our code. Their compliance.”

He picked up an orange smoke grenade from the line he’d arranged on the crate: white, yellow, red, orange, green, violet. They looked like harmless little tin cans. They weren’t.

“Orange smoke means do not fire,” he said. “Means somebody up there”—he jerked his head vaguely toward where the sky would be if the trees weren’t in the way—“is looking and calling shots. At least as far as they’re concerned.”

“And as far as we’re concerned,” Cross said. “Sir, what’s the issue? Using it normally doesn’t seem like tactical heresy.”

James smiled thinly.

“The issue is that we’re going to use these wrong.”

Silence fell in the bunker, thick as the mud outside.

Sergeant Daniel Kowalski, fifty percent mustache and fifty percent skepticism, stared.

“Wrong,” he repeated.

“Deliberately,” James said.

“That going to be a multiple-choice question on the court-martial, sir?” Sergeant O’Brien muttered.

James held up the orange grenade.

“Gentlemen, we’re going to mark positions we are not in with orange smoke. The Germans, who are good little students of doctrine, will see it and interpret it exactly as they’ve been taught: ‘Avoid that area. That’s an artillery cone.’ They will route around it.”

He picked up a stub of pencil and drew a crude semicircle on the German map pinned to the wall, scratching in little bursts of orange.

“We place these here, here, here—signposts that all say ‘don’t be here.’ We leave this”—he circled a ravine, a dark cut in the contour lines—“completely unmarked. That’s where we actually are. Machine guns here, here, and here.”

He looked up. “We don’t have the strength to stop them head-on. We can’t call in shells. We can’t fall back without losing more men to mines. The only way we stay alive is if we make them choose our ground.”

Walsh ran a hand over his face. “Sir, that’s… that’s not in any manual.”

“Exactly,” James said. “Which is why it might work.”

Kowalski shook his head slowly. “Captain, with respect, that’s going to get our own guys killed. If Division sees orange smoke on their maps around these coordinates, they’ll think they’re looking at enemy strongpoints. They’ll drop everything they’ve got.”

James tapped the dead radio in the corner with the side of his boot.

“Radio’s been useless for six hours,” he said. “Battalion doesn’t know where the hell we are. Division even less. Artillery support in this forest is a bad joke. Air can’t see us. The only eyes that are going to see this smoke are the ones attached to men trying to kill us.”

Lieutenant Walsh’s jaw tightened.

“And Geneva?” he asked. “Protocols? Misusing signals, deceptive markings—this feels like the kind of thing some lawyer back home would call a war crime.”

James nodded once.

“I’ve thought about that,” he said. “I taught kids the difference between right and wrong for a living, Lieutenant. I’m not real keen on jumping categories.”

He looked from man to man, seeing the doubt, the exhaustion, the stubborn thread of hope that refused to die.

“But doctrine is supposed to save lives,” he said. “Right now it’s getting us killed. We’re dying by the book. I’m asking you: do you want to follow the rules into the grave, or bend them hard enough to keep these boys breathing?”

Cross sighed through his nose.

“And if the Germans figure out that orange means ‘here be Americans’ instead of ‘here be artillery’? They push straight through the smoke and we’re standing in that ravine with our pants down.”

“Then we’re dead,” James said simply. “Same as we will be if we do nothing. I’d prefer to die trying something interesting.”

A short, harsh laugh broke from Torres.

“You’re a crazy man, Captain,” he said. “But you’re the only crazy we’ve got.”

James nodded.

“I need everyone on the same page,” he said quietly. “I don’t want anyone following an order they think is wrong. You all know the stakes.”

One by one, the platoon leaders and sergeants nodded.

“We’re in,” Cross said.

“Hell, sir, if this works, I’ll buy you a beer for every German you bag,” Kowalski grumbled.

James put a hand on the orange grenade.

“Then let’s go explain to battalion why their quiet little math teacher wants to invert twenty years of tactical doctrine.”

“I’m Going to Lose Radio Contact with You”

The radio crackled like a campfire in a windstorm. Static blasted intermittently; every third word cut out.

“—Easy Six, this is Red Two. Say again your last. Over.”

“Red Two, Easy Six,” James said into the handset, hunched in the bunker’s corner where the signal was strongest. “Did you copy my plan? Over.”

“Copy…some,” came Major Robert Gresley’s voice, thin under the noise. “Say again. Over.”

James took a breath.

“Sir, I intend to employ orange smoke grenades to mark positions my company does not occupy,” he said slowly. “Objective is to manipulate enemy movement based on their doctrinal interpretation of our signals, thereby funneling them into a prepared ambush zone. Over.”

Silence, then a disbelieving chuckle.

“Let me make sure I heard that right, Captain,” Gresley said. “You’re going to use the wrong smoke signals on purpose to trick the Krauts into walking where you want them. Over.”

“Yes, sir,” James said. “Enemy manual in my possession confirms they avoid orange smoke positions to prevent moving into pre-registered artillery targets. We mark false positions, they avoid them. They go where we’ve left gaps. Over.”

Another voice came on the line, firmer, with the clipped authority of a man whose boots had not seen the inside of this particular forest.

“Captain Hullbrook, this is Colonel Kemp,” it said.

James shut his eyes briefly. Regimental commander. This was about to get interesting.

“Yes, sir,” James said. “Easy Six. Over.”

“What you’re proposing,” Kemp said, “is not ‘interesting.’ It is a deliberate violation of established tactical signaling doctrine. It undermines the integrity of our smoke code. If the enemy realizes what you’re doing, they won’t trust any orange smoke ever again. That affects not just you—it affects the entire theater. Over.”

“Understood, sir,” James said. “Respectfully, we already live in a world where our smoke code isn’t saving us. We’ve popped every color in the rainbow and the only thing that happens is the Germans adjust their aim. We have no artillery, no air. The only folks reading our signals are them. Over.”

“You are aware,” Kemp said, voice cooling further, “that misuse of tactical signals violates FM 21-50, Army regs, and the Geneva conventions. You are putting yourself in line for a court-martial if you survive. Over.”

James stared at the bunker wall, at the pinned German map with its neat little symbols, at the emptiness where thirty more men could have been.

“Sir,” he said, choosing each word, “with respect… my first responsibility is to the lives of the men under my command. Right now, those lives are being traded for inches by the book. If I follow doctrine, Easy Company dies within the day. If I don’t, we might live. Over.”

Static hissed. He imagined Gresley and Kemp conferring over the radio operators’ shoulders, heads bent, eyes on their own maps. The line popped and sizzled with atmospheric noise.

“Captain,” Kemp said finally, “you will conduct a fighting withdrawal to—”

“Negative, sir,” James cut in, before he could stop himself. “We cannot withdraw. We are surrounded on three sides. The fourth side is a minefield. We tried to pull back yesterday. Lost eight men to S-mines in ten minutes. We hold here, or we die here. There is no way out. Over.”

The silence that followed was thick enough to chew.

“Are you refusing a direct order, Captain?” Kemp asked, voice flat.

“No, sir,” James said. “I’m telling you it’s tactically impossible. The only maneuver left is offensive deception. I can hold this ground. I can take Major Steiner’s regiment off your board. But I cannot do it by the book. Over.”

Gresley’s voice broke in, a half-whispered aside James wasn’t supposed to hear. “Ed, he’s right about the minefields. Third battalion tried to pull back last night; they’re down to eighty men. If he wants to try something, this is the place.”

Another officer, sounding young and outraged, hissed, “We can’t authorize corruption of signals protocol. That blows up half our coordination. You let one captain freeload his own doctrine—”

“Easy Six,” Kemp said suddenly, the command back in his tone. “I am going to say something, and then this radio is going to have technical difficulties for the next six hours. During that time, you are an isolated unit under independent command. Do you understand me? Over.”

James felt the tiniest thread of relief untwist in his gut.

“Yes, sir,” he said. “I understand. Over.”

“You will take whatever action you deem necessary for the survival of your command,” Kemp said. “If you succeed, we will call it tactical initiative. If you fail…” His voice thinned. “Well, then we will not have to discuss the legal ramifications, will we? Over.”

“No, sir,” James said. “We will not. Over.”

“One last question, Captain,” Kemp said. “Projected casualties if you do nothing vs. if your plan fails vs. if it succeeds. Over.”

“If I do nothing, sir, we’re gone. All 143 within the day,” James said. “If the plan fails, same result. If it works… I’m guessing ten to fifteen wounded in the initial contact. Then, if they surrender, zero. Over.”

More muffled conversation, like the phone pressed against someone’s shoulder.

“Very well,” Kemp said. “Red Two will now experience severe radio interference. Good luck, Captain. Kemp out.”

The line went dead.

James lowered the handset and let out a breath he hadn’t realized he’d been holding.

“Sir?” Cross said from the doorway.

James looked up.

“Well,” he said. “We just got unofficial permission to either be brilliant or very, very dead.”

Phase One: A Plume and a Pause

At 10:45, Easy Company went quiet.

No idle talk. No scraping of mess kits. Even coughing seemed to happen softer.

Men sat in foxholes dug into frozen earth, rifles laid across the parapets, watching the trees. The forest made enough noise on its own—creaking trunks, branches snapping under the weight of snow and shrapnel. The distant boom of artillery from sectors they would never see.

Sergeant Henry Torres belly-crawled through underbrush to a shallow depression one hundred fifty meters north of the real line. He felt naked away from the company positions, the forest pressing in on him.

He reached the pre-marked spot, a little dip between two blasted-off stumps, and pulled an orange smoke grenade from his pouch.

He’d used smoke a dozen times before—white and yellow, mostly. Pop it, toss it, move under cover. Never thought much about what the color meant beyond where he wanted shells to land or not land.

This one felt heavier.

He pulled the pin, counted, and lobbed it into the clearing.

The grenade hissed. Thick orange smoke poured out, curling, climbing, vivid against the dark trees. In seconds, it billowed high enough to be seen above the low ridge lines.

Torres slithered back, heart pounding, hugging dirt.

In his observation foxhole, James watched through the binoculars.

“Come on,” he whispered. “See it.”

He didn’t have to wait long.

A German patrol emerged through the trees downslope, maybe thirty men in feldgrau coats, weapons at the ready. At their head, a Feldwebel with a cap instead of a helmet paused, squinting up at the foreign color.

James could see the man’s posture change when he spotted the plume. The sergeant pulled a booklet from his pocket—standard-issue manual—flipped to a page, glanced from it to the smoke, and shouted something.

The patrol shifted direction, moving away from the orange.

They didn’t hurry. They didn’t panic. It was a matter of course, like a driver seeing a red traffic light and stopping without thinking.

They had drilled this.

“Sergeant Torres, this is Easy Six,” James murmured into the field phone that ran along the trench. “Report.”

Torres’ voice came back, breathless but exultant. “They routed around it, sir. Just like you said. Didn’t come within fifty yards. Over.”

James scribbled in his notebook. 1120. Initial orange test. Enemy avoids. Doctrine confirmed.

Behind him, O’Brien let out a soft, unbelieving whistle.

“I’ll be damned,” he said.

James smiled tightly.

“Phase one works,” he said. “Time to set the maze.”

Phase Two: Building a Trap in the Trees

The ravine didn’t have a name.

On the map it was just a squiggle, a contour line dip between two insignificant bumps. In person, it was a shadowed gash in the earth, cluttered with fallen trunks and rotting leaves and the debris of a hundred shell blasts.

It was also the closest thing the terrain offered to a natural amphitheater.

Easy Company set to work.

Machine-gun crew under PFC James Mitchell hauled their battered Browning .30-caliber into position on the ravine’s west side, sighting along arcs that intersected near the center. Two more crews set up on the flanks, angles overlapping. Ammunition boxes—what was left of them—stacked at their knees.

Rifle squads dug shallow pits around those points, scraping at the frozen ground until their fingers bled through the gloves, forming a ring of interlocking fields of fire.

Above and around that empty center, smoke teams moved out.

At each designated grid coordinate—472, 475, 480, 483, 487, 490—an orange grenade would go off at the appointed time. Each would mark a patch of forest that held nothing but stumps and snow.

“Think of them as little fences,” James told the men. “Except instead of barbed wire, you’ve got German common sense.”

“You’re sure they won’t, you know, not be stupid?” Kowalski asked. “You’re betting their officers are as obsessed with doctrine as ours.”

“I’m betting they’re professionals,” James said. “And professionals obey the manual until something breaks them of the habit.”

“You’re the one doing the breaking,” Torres said.

James looked at his watch.

“Eleven thirty. Orange at 472 in five minutes,” he said. “Then every seven minutes after that, next position. No one fires a shot unless fired upon. Let the smoke talk first.”

The first two plumes went up as planned—the hiss, the bloom, the columns staining the raw November air.

From his vantage, James watched German squads encounter each in turn, pause, then adjust course to skirt the edges. Always away. Always treating the smoke like an invisible wall.

Their routes became channels.

Those channels all led to the ravine.

By 12:20, the forest beyond Easy Company’s line was alive with movement. This wasn’t a probe anymore. This was a coordinated push, elements from several German units converging, with shouted commands cutting through the trees.

Later, intelligence would confirm what James only suspected then: three battalions’ worth of Steiner’s regiment were involved in this sector’s advance. Six hundred men at least. Probably more.

“Feels like half the Wehrmacht’s stomping around out there,” Chen muttered, lying prone behind his rifle.

“Good,” James said softly. “Would be a shame to waste all that smoke.”

The last orange grenade went off, arcing through the air in a lazy tumble before clattering to a stop and vomiting its warning skyward.

James watched the German line flow around the plumes like water around rocks.

Right into the cut in the land.

Right into his guns.

He felt a strange calm settle over him. The plan now moved into the physics stage: bullets and bodies, angles and timing.

He lifted the whistle that hung around his neck, the cheap metal cold against his lips.

Phase Three: “Fish in a Barrel”

The ravine filled with Germans.

They came in companies, then fragmenting squads, the cohesion of their lines broken by the need to avoid orange-marked patches. They dropped into the cut because it looked less dangerous than walking under the colored plumes.

They were right about one thing.

The danger wasn’t in the smoke.

When James judged that the density in the ravine had reached the tipping point—two hundred men clustered in a space meant for far fewer—he blew the whistle and shouted into the field phone.

“Guns—now!”

Mitchell squeezed the trigger on the Browning.

The .30-caliber roared, a throat-punch of sound that echoed off the ravine walls. Bullet after bullet chewed through trees and flesh. Men dropped where they stood, tripping others, turning the ravine floor into a tangle of bodies.

On the flanks, the other machine guns opened up in turn, their fire converging on the center. Tracers stitched the air in wicked arcs. Rifle fire joined in, cracks and pops underscoring the deeper chattering.

For the first few seconds, the Germans froze.

Then training kicked in. Some dove for cover. Some tried to identify the firing points. A few fired back blindly.

But there was nowhere to go that wasn’t exposed to at least one gun. The orange plumes hung at the edges of the ravine like accusatory columns, psychological barriers as much as visual ones.

Don’t go there, doctrine whispered in every German soldier’s head. That’s where the shells fall.

In that hesitation, more men fell.

Mitchell, working the primary gun, would tell people later, “They were packed in there like fish in a barrel. I’ve never seen anything like it. They bunched up trying to avoid the smoke positions and they walked right into our guns. It was a turkey shoot. Horrible and perfect at the same time.”

James didn’t share the sense of perfection.

Looking down through his binoculars at the slaughter, he felt something twist in his gut. This was math, applied brutally: density, angle of fire, rate of fire, kill zones. It was also men dying, cut down by a trick he had engineered.

He let himself feel it for half a heartbeat. Then he shoved it into a box in his head labeled Later and focused on the fight.

“Short bursts!” he called down the line. “Don’t cook the barrels! Conserving ammo!”

The firefight lasted less than a minute in its first furious phase.

Then German officers somewhere in the mix started blowing whistles and shouting.

Small groups tried to break out, scrambling up the sides of the ravine, only to flinch away from the orange smoke markers.

James saw a squad make a dash straight through one of the plumes, bodies disappearing briefly in the tinted fog, reappearing on the other side—right into the waiting rifles of an Easy Company squad positioned to cover the unlikely move.

Kowalski’s men cut them down in a stuttering volley.

“Almost feel bad for them,” someone muttered. “Almost.”

At 13:15, James spotted a movement that stood out from the chaos: an officer’s cap, map case, the body language of command.

Major Wilhelm Steiner himself, though James didn’t know his name yet, was trying to rally his men for a concerted breakout.

Steiner pointed toward the least dense smoke plume and gestured with the classic circular motion of forward attack.

James anticipated it.

“Second platoon, shift to grid 480,” he ordered. “They’re going to come through that smoke. Meet them there.”

When the German wedge pushed through, they ran into fresh rifles and two BARs, not empty ground.

The breakout died under American fire.

By 14:00, the shooting had slowed to sporadic bursts. The Germans had hunkered down in whatever cover the ravine provided. The orange smoke, dissipating now into a rusty haze, still hung at the edges.

Easy Company had lost twelve men wounded. No one dead, yet.

Down below, hundreds of Germans lay dead or bleeding, and hundreds more realized that every path was blocked—if not by American bullets, then by their own training.

It was a prison made of doctrine and smoke.

James checked his watch. He felt the adrenaline ebb a little. There would be a counterpunch. There always was.

Instead, at 14:45, a white cloth appeared.

“How Many Men Do You Command?”

The German soldier who stumbled up out of the ravine looked like every other one of Steiner’s men—gray coat smeared with dirt and blood, helmet askew.

He carried a stick with a torn scrap of undershirt tied to it.

Our side had done the same thing more than once over the last five years. Different language, same symbol.

James held fire with a raised hand.

“Hold on,” he told his men. “Let him come in.”

The soldier reached the base of Easy Company’s line and stopped, panting, eyes flicking from foxhole to foxhole. He called something in German.

“Burkowitz!” James shouted.

Corporal Samuel Burkowitz, who had been born in Brooklyn to parents who still swore in Yiddish, slid into the command post like he’d been waiting for the cue.

“Ja, sir?”

“Tell him to bring his officer,” James said. “And tell him if anybody comes up here shooting, we go right back to mowing them down.”

Burkowitz nodded and shouted down in rapid-fire German. The messenger bobbed his head and retreated.

Five minutes later, Major Wilhelm Steiner climbed the ravine slope, boots slipping in mud, one hand raised slightly to show he was unarmed.

He was in his late thirties, maybe early forties, with the gaunt look of a man who’d watched his army shrink since ’39. His uniform was dirty but neat, collar tabs marking him as something above the rank-and-file. His face was set in a stiff, formal mask.

He stopped at the tree line, measuring the distance to the American foxholes.

“Permission to approach, Herr Hauptmann?” he asked.

“Tell him he can come to that log and no further,” James said. “And that his men are to stay put, weapons down.”

Burkowitz translated. Steiner nodded, stepped up to the indicated log, and stopped. His eyes flicked over the American positions. He seemed to be counting.

“You wish to surrender?” James asked.

Burkowitz relayed the question.

Steiner swallowed.

“I wish to know your terms,” he said.

“Unconditional,” James said. “Your men come up in groups of ten, weapons left behind, hands on their heads. We’ll process you as prisoners of war. You’ll be treated according to the Geneva conventions. Any group that tries to use the approach to launch an attack gets cut down. Your wounded will be treated as best we can. Those are the terms.”

Steiner listened, jaw tight.

“And how many forces do you have in the area?” he asked. “How many men under your command?”

James considered lying.

Then he decided the truth would be worse.

“Tell him,” he said to Burkowitz, “when we started this morning, we had one hundred forty-three men. We have fewer now.”

Burkowitz translated.

Steiner’s eyebrows rose. For the first time, the mask cracked.

“Einhundert drei und vierzig?” he repeated. “That is all?”

James nodded.

Steiner looked back toward the ravine, where nearly two thousand men waited, trapped.

He let out a sound that was half laugh, half sigh.

“You trapped an entire regiment with colored smoke and one company,” he said, almost to himself.

James shrugged.

“I trapped you with your own tactical manual,” he said. “You followed your doctrine perfectly. That’s why it worked.”

Steiner’s lips tightened, then quirked in what might have been the ghost of a smile.

“I suppose there is some admiration to be given,” he said. “You were a teacher before the war, yes?”

James blinked.

“How did you—”

Steiner gestured vaguely at James’ manner, his speech. “You sound like a man who explained things for a living.”

“I did,” James admitted.

Steiner nodded slowly.

“Very well, Herr Hauptmann,” he said. “I accept your terms. My regiment will surrender.”

He extended his hand.

James hesitated for a fraction of a second, then stepped forward and took it.

The handshake was brief and firm. Years later, James would say that in that moment, it felt less like enemies meeting and more like two professionals acknowledging a problem solved in an unexpected way.

Then the real work began.

Counting the Cost

It took hours to process them all.

Lines of German soldiers shuffled up from the ravine in groups of ten, weapons piled in heaps at the bottom of the slope. Easy Company disarmed them, searched them for concealed pistols or grenades, and marched them to a makeshift holding area near a logging road where, in theory, regimental MPs would eventually find them.

1847 prisoners by the end of the day.

James had never seen so many men in one place, outside of a training exercise. All of them in gray. All of them alive because he’d given them a chance when he could have ordered another forty-second burst and turned the ravine into a charnel house.

German casualties in the engagement—killed and wounded—would later be tallied at 287 killed, 422 wounded.

Easy Company’s casualty sheet for Operation Backfire: twelve wounded. No dead during the action.

From a cold, clinical perspective, the numbers were obscene in a different direction now. A kill-and-capture ratio of more than one hundred fifty to one.

James stood on the edge of the prisoner pen as dusk smeared the sky purple, watching the mass of men huddled in the cold. Some stared back at him with blank expressions. Some looked away. Some slept sitting up, too exhausted to care which flag flew over their temporary cage.

Chen limped up beside him, bandage visible at his collar where a leaf splinter had nicked his neck.

“Sir,” he said.

“Yes, Private?”

“I just… wanted to say…” Chen gestured helplessly at the scene. “You did it. You actually did it.”

James let his shoulders sag a little.

“We did it,” he said. “Mitchell’s gun jammed once; if Torres hadn’t cleared that jam, we’d be talking about a different ending.”

“You’re a modest son of a gun, Captain,” Chen said. “Don’t worry. We’ll exaggerate it in the retelling.”

James laughed once, softly.

“You planning on telling this story?” he asked. “I’m not even sure how I’d phrase it in my report without someone back home thinking I lost my sanity.”

Chen shrugged.

“We’ll start simple,” he said. “ ‘There we were, in the worst hell the war could throw at us, and our CO popped the wrong smoke and saved our asses.’ That’s a start.”

James watched a German medic bandaging one of his own wounded under the eye of an American corpsman. War made strange pairings.

He felt the moral weight of what he’d done pressing in—the bending of rules, the use of enemy training against them, the deliberate creation of a trap.

He thought of the bodies in the ravine. He thought of the men hanging in village squares elsewhere in Europe because someone had blown a bridge or derailed a train.

The Hurtgen had stomped out any remaining illusions he’d had about clean war.

“Sometimes,” he said quietly, more to himself than to Chen, “the only right move is the one that keeps the most people alive. Even if the rulebook doesn’t have a page for it.”

Chen looked at him for a long moment.

“That’s why you’re the one with the bars, sir,” he said. “You’re willing to be smarter than the rules.”

The Part the History Books Care About

They called it Operation Backfire in the classified reports.

Someone in battalion with a sense of irony had typed the codename at the top of the after-action summary. The name stuck, half joke, half acknowledgment that James had turned the Germans’ own fire doctrine back on them.

At a regimental staff meeting in early December, Colonel Kemp read the report, then read it again.

“Three machine guns, one full company, eighteen hundred prisoners,” he said slowly. “Minimal casualties.”

The S-3, the operations officer, whistled.

“Sir, that’s—”

“Unprecedented,” Kemp said. “Especially in that damn forest.”

Major Gresley, still looking like he hadn’t slept since September, tapped a finger on the margins.

“We’ll need to be careful how we write this up,” he said. “Can’t exactly put ‘deliberately violated smoke signaling doctrine’ in the official record without some colonel in G-3 having a stroke.”

“Call it ‘tactical deception using smoke as maneuver aid,’” the S-3 suggested. “Or ‘innovative employment of standardized signals.’”

“Innovative,” Kemp repeated, lips twitching. “I like that word. Covers a multitude of sins.”

He signed the bottom of the recommendation anyway.

On December 3, in a muddy assembly area far enough from the line that the trees didn’t loom so close, James stood in a line of men in dress coats that still smelled faintly of the forest.

Major Gresley pinned a Distinguished Service Cross to his chest while the division commander read the citation.

“ …extraordinary heroism in connection with military operations against an armed enemy…”

“ …demonstrated extraordinary tactical innovation in using enemy doctrinal compliance as a force multiplier…”

“ …achieving unprecedented results with minimal casualties through the application of asymmetric tactical deception…”

The words washed over him. He thought about the bunker, about orange smoke against gray sky, about Steiner’s face when he heard “one hundred forty-three men.”

He thought about all the other captains in all the other companies who had followed the book and died with their men in the same forest.

After the ceremony, Gresley clapped him on the shoulder.

“You bought this whole division some breathing room,” the major said. “Pulled a regimental thorn out of our side with a handful of grenades.”

James shrugged uncomfortably.

“I just got tired of trading good men for bad trees,” he said.

Sometime in ’45, back in the States, someone in the War Department rewrote FM 21-50.

New sections appeared, written in the dense, dry language of doctrine but carrying an undercurrent of change.

“ …Under certain conditions, smoke signals may be employed in deceptive operations intended to induce enemy forces to respond in a predictable manner…”

“ …Commanders should consider enemy training and doctrinal habits as potential vulnerabilities…”

The lesson filtered outwards.

Through the fifties and sixties, as the Army adapted to new theaters—desert, jungle, city—case studies of Operation Backfire appeared in lecture halls at Fort Benning, at the Army War College, at a campus on the Hudson called West Point.

Cadets sat in neat rows, notebooks open, and listened as instructors drew diagrams on chalkboards:

“Enemy sees orange, assumes artillery target, avoids area. Friendly uses this to funnel movement. Deception by manipulation of expectations. Note that success depends entirely on enemy’s reliability in following their own procedures.”

Major Wilhelm Steiner, repatriated after the war and living in a Germany split by a new kind of line, wrote a letter in 1967 to a historian collecting material on Hurtgen.

“We were defeated by a teacher with smoke grenades because we were too well-trained,” he wrote. “Our doctrine was excellent, our execution was flawless, and both became weapons used against us. This is the paradox of military training. The better you follow established procedures, the more predictable you become to an enemy who understands those procedures. Captain Hullbrook understood this. We did not.”

By then, James was back in Scranton.

He had gone home after the war, taken off the uniform, hung the DSC in a drawer he rarely opened, and gone back to a classroom.

His students knew he’d been “over there.” They saw the limp when the weather turned damp, the way loud noises made his eyes flick to the door. They joked about “Old Man Hullbrook” and his obsession with showing his work on math problems.

They did not know about orange smoke in a German forest.

He coached basketball again. He raised kids. He attended faculty meetings that seemed surreal after staff briefings about casualty ratios.

He did not put “changed Army doctrine” on his resume.

When he died in 1989, nearly two hundred men from Easy Company and other units made the trek to Scranton Municipal Cemetery.

PFC Robert Chen—older now, hair thin, voice still carrying that blend of respect and teasing—spoke at the graveside.

“Because of you,” Chen said, voice catching, “we learned that thinking beats doctrine every time. We learned that just because the book says one thing doesn’t mean we have to die for it. You saved us by refusing to fight the way they expected. You saved us by being smarter than the rules.”

The headstone said only:

JAMES M. HULLBROOK

1917–1989

TEACHER

At his request, there was no mention of rank, or medals, or the forest.

He had helped people understand, in life and in war.

The men who’d followed him through the Hurtgen knew that was only half the story.

The other half was this:

In a place where the rules weren’t working, one man had the courage to say so.

He looked at a system designed for a different battlefield and chose to break its logic rather than break his men against it.

He trusted his understanding of people—of how an enemy officer, trained to respect orange smoke, would respond more faithfully to doctrine than any friendly commander back in a tent.

He turned training into trap, competence into vulnerability, and colored smoke into a weapon of mass surrender.

The Moral in the Smoke

Ask ten veterans what the lesson of Operation Backfire is, and you’ll get a dozen answers.

Some will talk about understanding the enemy. Some will talk about initiative. Some will talk about the Hurtgen itself and the price of stubborn strategy.

But if you strip the story down to its core, it comes to this:

Sometimes, survival means throwing out the playbook.

Sometimes, the institution is wrong and the man in the mud is right.

Sometimes, the difference between disaster and victory is one person willing to say, “The book isn’t working. Let’s try something else.”

In a war defined by massive movements of armies and grand offensives, it’s easy to forget the moments where the outcome turned on a smaller scale—on a ridge, a ravine, a handful of smoke grenades in the hands of a captain who used to explain algebra.

The Hurtgen Forest swallowed thousands of lives in those months.

On one gray November day, it spat out a different kind of story.

Smoke billowed orange against the sky—wrong color, wrong place, wrong doctrine.

And because of that, hundreds of men walked out alive who would otherwise have bled into the forest floor.

THE END

News

CH2 – On a fourteen-below Belgian morning, a Minnesota farm kid turned combat mechanic crawls through no man’s land with bottles of homemade grease mix, slips under the guns of five Tiger tanks, and bets his life that one crazy frozen trick can jam their turrets and save his battered squad from being wiped out.

At 0400 hours on February 7th, 1945, Corporal James Theodore McKenzie looked like any other exhausted American infantryman trying not…

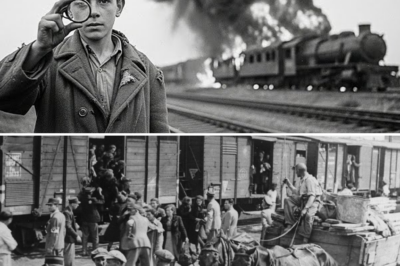

CH2 – The 12-Year-Old Boy Who Destroyed Nazi Trains Using Only an Eyeglass Lens and the Sun…

The boy’s hands were shaking so hard he almost dropped the glass. He tightened his fingers around it until…

CH2 – How One Iowa Farm Kid Turned a Dented Soup Can Into a “Ghost Sniper,” Spooked an Entire Japanese Battalion off a Jungle Ridge in Just 5 Days, and Proved That in War—and in Life—The Smartest Use of Trash, Sunlight, and Nerve Can Beat Superior Numbers Every Time

November 1943 Bougainville Island The jungle didn’t breathe; it sweated. Heat pressed down like a wet hand, and the air…

CH2 The Farm Kid Who Learned to Lead His Shots: How a Quiet Wisconsin Boy, a Twin-Tailed “Devil” of a Plane, and One Crazy Trick in the Sky Turned a Nobody into America’s Ace of Aces and Brought Down Forty Japanese Fighters in the Last, Bloody Years of World War II

The first time the farm kid pulled the trigger on his crazy trick, there were three Japanese fighters stacked in…

CH2 – On a blasted slope of Iwo Jima, a quiet Alabama farm boy named Wilson Watson shoulders a “too heavy” Browning Automatic Rifle and, in fifteen brutal minutes of smoke, blood, and stubborn grit, turns one doomed hilltop into his own battlefield, tearing apart a Japanese company and rewriting Marine combat doctrine forever

February 26, 1945 Pre-dawn, somewhere off Eojima The landing craft bucked under them like an angry mule, climbing one…

CH2 – How One Cook’s “Crazy” Plan Saved Thanksgiving For 5,000 Frozen Soldiers In Hürtgen Forest

At 0547 hours, November 23, 1944, Staff Sergeant Antonio “Tony” Marino was ankle-deep in ice and mud at the bottom…

End of content

No more pages to load