Part 1

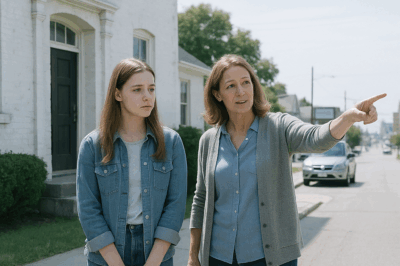

The doctor’s words made my blood run cold.

“Mrs. Brennan, we found traces of rat poison in your daughter’s bloodstream—and it’s been building up for weeks.”

It’s strange how one sentence can split your life cleanly in two: before and after.

Before, I was just Jolene Brennan — thirty-five years old, a single mom, a dental hygienist who worked four days a week, drove a reliable Honda Civic, and tried to make ends meet with a little grace and a lot of caffeine.

After… I became the mother of a poisoned child.

That morning had been like any other.

I’d packed Meadow’s lunch — turkey sandwich, apple slices, juice box — kissed her forehead, and sent her off to Riverside Elementary with a wave. She turned around at the crosswalk like she always did, flashing me a grin full of missing baby teeth.

That smile could’ve lit up the grayest day.

It was also the last normal moment I would remember.

At 2:47 p.m., I was at work, scraping plaque from a patient’s lower molar, when Denise, our receptionist, burst into the room. Her face was ghost white, her voice shaking.

“Jolene, you need to go now. Riverside Elementary called. Meadow collapsed during art class. The ambulance is taking her to Peninsula Medical.”

My hands went numb. The metal scaler clattered onto the tray.

I didn’t even remove my gloves before sprinting out the door. Denise shoved my purse and car keys into my hands.

“Go. We’ll handle everything here,” she said, her eyes wide with the kind of fear that only parents recognize in each other.

The drive to the hospital was a blur of red lights and honking horns. My vision tunneled; my pulse beat in my ears louder than the radio.

Every thought dissolved into one mantra: Please, please, please let her be okay.

When I pulled into Peninsula Medical Center’s parking lot, I barely remembered stopping the car. I ran through the sliding glass doors, breathless, shouting her name.

“Meadow Brennan — my daughter! Where is she?”

The nurse at the desk pointed me toward the pediatric emergency ward. My shoes squeaked against the linoleum as I rushed down the hallway. The smell of disinfectant burned my throat.

When I reached Bay 3, I froze.

My little girl was lying on a gurney surrounded by machines, IV lines, and a monitor that beeped a steady, cruel rhythm.

Her rainbow t-shirt had been cut open.

Her skin was so pale it looked translucent.

She looked… wrong. Like someone had drained the sunlight from her.

“Mrs. Brennan?”

The doctor’s voice startled me. A tall man in green scrubs approached, calm but serious.

His badge read Dr. Akil Rasheed.

“I’m the attending physician,” he said gently. “Your daughter is stable for now, but we need to talk.”

He led me into a small consultation room — too bright, too clean, with cheerful whale paintings on the walls that suddenly felt obscene. He sat across from me, holding a tablet filled with charts and numbers I couldn’t process.

“Your daughter’s liver enzymes are severely elevated,” he explained. “Her blood isn’t clotting properly. These symptoms are consistent with systematic poisoning.”

I blinked at him, the words not computing.

“Poisoning? You mean food poisoning?”

He shook his head. “No, Mrs. Brennan. Chemical poisoning.”

My heart stuttered. “That can’t be right. She’s seven. She doesn’t touch cleaning supplies. We don’t even have a yard for pesticides.”

“Could she have access to any other environment? Relatives? Babysitters?”

And that’s when my stomach dropped.

Francine.

Her grandmother.

My ex-mother-in-law.

“She spends weekends with her grandmother,” I said slowly. “Francine Holloway. But she’s… careful. She irons her bed sheets for God’s sake.”

Dr. Rasheed nodded, making notes. “Let’s not jump to conclusions. Please call her. Ask what Meadow ate this weekend.”

My hands trembled as I dialed.

Francine answered on the second ring, her voice as smooth and polite as always.

“Jolene, dear. What a surprise.”

I forced my voice steady. “Francine, Meadow’s in the hospital. She collapsed at school. The doctors think it might be something she ate. What did she have at your house this weekend?”

A pause.

“Why would you ask me that?” Her tone sharpened. “She ate wholesome meals, as always. Fresh fruit, vegetables from my garden. Certainly nothing harmful.”

“Francine, please. This is serious.”

“Perhaps you should look at your own home, Jolene,” she said icily. “You know I’ve always worried about how busy you are.”

And then she hung up.

When I returned to Meadow’s room, her eyes were open — glassy, unfocused, but awake.

“Mommy,” she whispered, “my tummy hurts. Like when I drink Grandma’s smoothies. But worse.”

The doctor’s head snapped up.

“Smoothies?”

She nodded weakly. “Grandma says they’re full of love and vitamins. Green ones. She says they make me grow tall like a sunflower.”

Dr. Rasheed’s expression hardened.

He stepped out and came back minutes later.

“We’re running a toxicology screen for rodenticides,” he said. “Specifically brodifacoum — a compound found in rat poison.”

My knees buckled.

“You think someone’s been giving my child rat poison?”

“That’s what we need to determine.”

The test results came back two hours later.

Positive.

Brodifacoum in her blood, at levels indicating repeated exposure for at least six weeks.

“This isn’t accidental,” Dr. Rasheed said softly. “Someone has been giving your daughter measured doses — enough to make her ill, not kill her outright.”

And just like that, every sweet weekend at Grandma’s — the cookies, the smoothies, the garden walks — turned into evidence.

Every Friday at 4 p.m., I had watched that white Buick pull up outside our apartment. Francine, elegant as always, stepping out in pressed slacks and a cardigan. Meadow would squeal, run into her arms, and they’d drive off, the car gliding away like a scene from a commercial.

Now I knew that each goodbye was a handover to hell.

Detective Ramon Vega arrived before midnight. Early forties, clean-cut, sharp eyes softened by empathy.

He introduced himself quietly, sat across from me, and opened a worn leather notebook.

“Mrs. Brennan, I’m going to ask you some difficult questions,” he said. “I need to know who’s had regular access to your daughter.”

“Just me and Francine,” I said. “My ex-husband Wyatt moved to Alaska months ago. He’s not part of her life anymore.”

The detective nodded. “Tell me about Francine.”

I hesitated. How could I summarize a woman like her?

Polite. Controlling. The kind of person who could weaponize a smile.

“She blamed me for the divorce,” I said finally. “She said I drove Wyatt to drinking. But she loves Meadow. Or—” my voice broke— “she pretended to.”

“Has she ever expressed resentment about the custody arrangement?”

I remembered her words: ‘If you can’t provide proper care, maybe other arrangements should be made.’

“She said something like that once,” I whispered. “I thought she was offering help.”

Detective Vega closed his notebook. “Mrs. Brennan, we’ll need to search her home. Can you give us a way in that won’t raise suspicion?”

I didn’t know what to say until a small voice broke through the tension.

“Mommy,” Meadow murmured weakly. “Can you get Mr. Buttons? I want him here.”

I blinked. “Your stuffed rabbit? Where is he?”

“At Grandma’s,” she said. “On my bed.”

Detective Vega nodded. “Perfect. Call her. Tell her Meadow’s asking for her toy. Sound upset but don’t mention poison.”

I took a shaky breath and dialed again.

Francine answered right away.

“Jolene, dear, how is she?”

“She’s stable,” I said, forcing my voice to crack. “But she’s scared. She wants Mr. Buttons. Can I come get him?”

A pause.

“Of course, dear. Poor baby. I’ll leave the door unlocked for you. I’m heading to evening service soon.”

When I hung up, Vega was already dialing for a search warrant.

“You did perfectly,” he said. “We’ll be there before she gets back.”

I sat by Meadow’s bed, watching her small chest rise and fall, trying not to drown in guilt.

“Mommy,” she whispered, half-asleep. “Did Grandma make me sick?”

I pressed my lips to her forehead. “We’re going to find out, baby.”

At 6:43 p.m., Detective Vega called.

His voice was tight. “Mrs. Brennan, prepare yourself.”

He told me what they’d found.

Inside Francine’s spotless Victorian kitchen, in a locked cabinet beside the fridge, they discovered three boxes of rat poison — two empty, one half full.

Next to them: a small digital scale and a leather-bound journal filled with perfect cursive notes.

Each entry was dated, describing doses, symptoms, reactions — like a twisted lab experiment.

January 15th — 2.5 grams. M complained of taste but drank all. Slight fatigue by evening.

January 22nd — Increased to 3 grams. Told M it’s vitamin powder from the health store. She believes grandmother knows best.

I dropped the phone, ran to the hospital bathroom, and vomited until nothing was left.

When I came back to Meadow’s bedside, Vega was still on the line.

“She documented everything,” he said. “She even took photos — dated, labeled. Your daughter growing sicker each week.”

My heart shattered.

“How could she? Why?”

Vega hesitated before answering.

“She emailed your ex-husband. Sent him photos, told him you were neglecting Meadow. She said you were too busy for her. She wanted him to file for custody.”

I closed my eyes.

“So she poisoned my child… to make me look unfit.”

“Yes,” he said quietly. “To make herself look like the savior.”

When Francine came home from church that night, the police were waiting.

Officer Chen later told me she didn’t resist.

She just stood there, clutching her Bible, calm as stone.

When Vega read her rights and said “attempted murder of a child,” the mask cracked.

“That woman destroyed my family!” she screamed. “She took my son away! She’s an unfit mother — always working, never home. Meadow needed stability!”

“You poisoned a seven-year-old,” Vega said. “That’s not stability, Mrs. Holloway. That’s evil.”

Francine’s reply chilled him.

“I wasn’t killing her,” she hissed. “I was saving her from her mother.”

When the call ended, I sat there beside Meadow, holding her tiny hand.

Machines beeped softly. The smell of antiseptic and fear filled the air.

“She’s not coming back, is she?” Meadow asked quietly.

“No, baby,” I said, tears burning my eyes. “She’s not.”

“Because she put bad stuff in my drinks?”

I nodded. “Because she hurt you. And people who hurt children have to face consequences.”

She blinked, sleepy but lucid. “She said she loved me.”

My voice broke. “People who love you don’t make you sick.”

That night, as Meadow finally drifted into peaceful sleep, I sat by her bed and made a silent vow.

No one would ever hurt her again.

Not while I was still breathing.

Part 2

When I woke up in the hospital the next morning, I wasn’t sure what day it was. The plastic chair I’d been sleeping in had left deep red marks along my arms, and my neck ached from sleeping hunched over the bed.

Meadow was still asleep, her small hand resting in mine, the IV line taped carefully to her skin.

The faint color in her cheeks was a sign she was improving — Dr. Rasheed had said the vitamin K therapy was working — but I couldn’t shake the feeling that I was sitting beside a miracle that almost didn’t happen.

Every time the monitor beeped, my stomach clenched.

At 9 a.m., Detective Vega walked in, holding a cup of coffee that smelled like burnt rubber and salvation.

He looked like he hadn’t slept either.

“Morning, Mrs. Brennan,” he said gently.

“Morning,” I murmured. “Please tell me this is over.”

He shook his head. “We’ve got her in custody, but it’s not over yet. We’re cataloguing everything from the house. It’s… a lot.”

He hesitated before adding, “You need to hear it from me before the DA calls.”

They’d found the journal in Francine’s kitchen cabinet, wrapped neatly in a lace handkerchief.

Of course it was.

Even her crimes were tidy.

Detective Vega placed a photocopy of the first few pages on the rolling tray beside Meadow’s bed.

Her looping cursive sprawled across cream-colored paper like something out of an etiquette manual — the kind of handwriting that belonged to thank-you notes and church announcements, not this horror.

January 15 – 2.5 g in morning smoothie. M complained of taste but drank all. Slight fatigue by evening. Told J she should give vitamins more often.

January 22 – Increased to 3 g. Added cocoa powder to disguise taste. M accepted readily. Said she felt “sleepy.”

February 5 – Noticed pallor. Perfect. Will reduce next dose to maintain subtle decline. J remains oblivious. Court will see pattern soon.

Every line was clinical.

No emotion, no hesitation — just data.

A project.

My throat burned. “She planned this. Wrote it down like she was… testing a recipe.”

Detective Vega nodded. “There are six weeks of entries, plus notes about Meadow’s behavior — tiredness, bruising, appetite loss. She also kept track of your work schedule and your paydays.”

“Why?”

“She wanted to show you were overwhelmed. Her emails to Wyatt support that. She sent him copies of your schedule from social media, saying, ‘She’s too busy to notice her child fading.’”

The words made my hands shake.

I wanted to throw that photocopy across the room. Instead, I tore it neatly in half, like I could somehow destroy what she’d done.

“She was never helping,” I whispered. “She was collecting evidence.”

Vega’s expression softened. “People like Francine thrive on perception. They build a world where they’re the hero. Everyone else is just a prop.”

When the toxicology team finished analyzing the evidence, the results confirmed what we already knew: brodifacoum residue in the blender, on the measuring scale, even on her spotless marble countertop.

They also recovered dozens of photographs from Francine’s phone — dated, labeled, documenting Meadow’s decline like it was a science project.

Each one was more nauseating than the last.

Week 1: Meadow smiling, holding a cookie.

Week 3: Slight bruising on her legs.

Week 5: Hollow eyes, pale skin, that same cookie in her hand, uneaten.

Vega told me his team had to step outside for air after scrolling through them.

“Why would she take pictures?” I asked.

He looked tired. “Control. Proof. It’s the same reason she wrote the journal. People like her don’t think they’re doing wrong — they think they’re documenting righteousness.”

Later that afternoon, Dr. Rasheed stopped by to check on Meadow. She was awake now, coloring with the set a nurse had brought her. Her drawing was a butterfly — blue wings, black outline, heart in the center.

Dr. Rasheed smiled softly. “She’s improving beautifully. Her clotting levels are normalizing. She’s a lucky girl.”

Lucky.

The word didn’t fit.

Lucky was winning a raffle, not surviving a slow-motion murder.

When he left, I sat beside her bed, running my fingers through her hair.

“Mommy,” she said suddenly, “did Grandma get in trouble?”

“Yes, honey.”

“Will she have to say sorry?”

“She’ll have to tell the truth,” I said carefully.

She thought about that for a moment, then nodded and went back to coloring.

“The truth is better than sorry,” she said.

Three days later, Vega called again.

“Francine’s requesting to speak with you,” he said. “You’re not obligated.”

My first instinct was no. Absolutely not.

But curiosity — or maybe closure — made me ask, “Where?”

“In holding. She’s calm now. The DA and I will be present.”

So I went.

The police station smelled of coffee and old carpet. They led me to a small room divided by a glass partition.

Francine sat on the other side in a navy cardigan, her hair perfectly styled, hands folded like she was waiting for a church luncheon.

Even in handcuffs, she looked immaculate.

When she saw me, her mouth tightened into what might’ve been a smile.

“Jolene,” she said, her tone almost gentle. “You look tired.”

I stared through the glass. “You tried to kill my daughter.”

She tilted her head. “Don’t be dramatic. She would have recovered under my care. You’ve always misunderstood me.”

“Misunderstood?” I said, voice rising. “You poisoned a seven-year-old.”

“I protected her,” she snapped, the mask slipping for the first time. “From your neglect. From a mother who thinks love is working overtime and heating up microwaved dinners.”

Vega intervened quietly. “Mrs. Holloway—”

“No, let her talk,” I said, shaking. “I want to hear every delusion.”

Her eyes burned with cold conviction.

“You made Wyatt weak,” she said. “You took my son, filled his head with nonsense about independence, and then left him to drown. Meadow was my second chance. I wouldn’t let you ruin her too.”

Her words struck like physical blows, each one crueler for the calmness behind it.

“You were going to ruin her life,” I said. “You almost did.”

“She’ll thank me one day,” Francine said softly. “Children always do when they realize who truly loves them.”

Vega ended the interview. “That’s enough.”

As they escorted her out, she turned once more.

“You’ll see,” she said. “Mothers like you always crumble.”

But she was wrong.

I wasn’t crumbling — I was burning.

And I would make sure she never hurt another soul again.

The following weeks were a blur of police updates, court hearings, and endless questions from Child Protective Services. Even though everyone knew I wasn’t responsible, the process was automatic — procedure, they said.

A social worker named Carla James came by our apartment one evening. She was kind, firm, efficient. She asked to see Meadow’s room, checked the locks under the sink, and asked about our support network.

“I know this feels invasive,” she said, “but you’re doing everything right. You’re keeping her safe.”

After she left, I sat on the floor beside Meadow’s bed and cried silently. It wasn’t just grief — it was relief. Relief that the system was finally protecting my daughter, not questioning her pain.

Two weeks later, Wyatt flew back from Alaska.

I hadn’t seen him in nearly a year.

He walked into the hospital looking smaller somehow — sober, clean-shaven, but haunted.

The moment he saw Meadow, he fell to his knees beside her bed.

“Hey, sunflower,” he whispered.

She opened her eyes and smiled faintly. “Hi, Daddy.”

He took her hand carefully, as if afraid she might break.

“I’m sorry I wasn’t here,” he said. “I should’ve been.”

She nodded sleepily. “You can be here now.”

I had to turn away before the tears came.

When Wyatt and I finally spoke alone, we sat in the hospital cafeteria, nursing stale coffee. The silence between us was heavy but familiar.

“She did it to me, too,” he said quietly.

I looked up. “What?”

“My mom. When I was little. She used to make me these ‘vitamin shakes.’ I was sick all the time — mystery stomach bugs, fainting spells. Doctors never found anything. I thought I was just weak.”

I stared at him, realization dawning. “She’s been doing this her whole life.”

He nodded slowly. “Munchausen by proxy. That’s what my therapist called it. She needs people to depend on her — sick people. It’s how she feels loved.”

“So she poisoned her son,” I whispered, “and when she couldn’t control him anymore, she went after his daughter.”

“Exactly.”

Wyatt rubbed his face with both hands. “I can’t fix what she did. But I want to help now — with Meadow, with everything.”

I studied him for a long time, searching for lies, excuses, weakness.

But all I saw was a man trying to rebuild from ashes — his mother’s, his own.

“Then start by showing up,” I said. “Every day, not just when it’s convenient.”

He nodded. “Deal.”

The day of Francine’s arraignment, the courtroom was packed. She appeared in a navy suit, her pearl earrings glinting under the fluorescent lights — the picture of composure.

When the charges were read — attempted murder, aggravated assault, child endangerment — she didn’t flinch.

She sat perfectly straight, eyes forward, expression blank.

But when Meadow’s name was mentioned, her jaw tightened.

The prosecutor read excerpts from the journal aloud. The words echoed through the courtroom, clinical and damning. Each dose, each reaction. Each calculated attempt to make a child sick enough to justify taking her away.

The gallery gasped.

Wyatt gripped my hand so tightly my knuckles ached.

I didn’t pull away.

Francine’s lawyer tried to paint her as mentally unwell, suffering from delusions of care. But the evidence — the journal, the poison residue, the photos — stripped away any illusion of innocence.

By the time we left court that afternoon, the media had already caught wind of the story.

Headlines screamed across local news sites:

“Grandmother Accused in Rat Poison Case.”

“Domestic Angel or Hidden Monster?”

Neighbors whispered. Coworkers sent sympathetic texts. Parents from Meadow’s school avoided eye contact in the pickup line.

None of it mattered.

All that mattered was that Meadow was alive.

That night, as she slept in her hospital bed surrounded by cards and stuffed animals, I watched her chest rise and fall and whispered to myself,

“She’s never going back to that house.”

Not to the woman who pretended love meant ownership.

Not to the monster who wore pearls while mixing poison.

Whatever came next — therapy, court, rebuilding — we’d face it together.

And for the first time since the doctor’s words shattered my world, I believed it.

Part 3

The courthouse in downtown Peninsula looked like every courthouse in America—tall marble columns, flags snapping in the wind, a line of reporters clutching cameras and cheap coffee cups.

If you didn’t know better, you’d think it was an ordinary Tuesday morning.

But nothing about that day was ordinary.

That day, I walked my seven-year-old daughter past the people who wanted a glimpse of “the poisoned girl,” into a room where we would face the woman who had nearly killed her.

The prosecutor, Angela Dawes, was young, sharp, and carried herself like someone who had seen evil before and wasn’t impressed by it. She’d been on the case from the start. She met me in the hallway that morning, binder under one arm, her expression both fierce and kind.

“You don’t have to look at her if you don’t want to,” she said.

“I will,” I answered. “I need to.”

Inside, the courtroom was cold, too bright. The walls seemed to echo every cough and shuffle. Wyatt sat beside me at the prosecution’s table, fingers laced together so tightly his knuckles were white.

When the bailiff brought Francine in, a low murmur swept through the gallery.

She looked exactly the same—silver hair, pearl earrings, navy suit pressed to perfection. You would never have guessed she’d spent months in county jail.

Her expression was blank, except for the faint curl of disdain that always lived in the corners of her mouth.

Meadow wasn’t allowed in the courtroom, of course. She was in a separate room with a therapist and a court advocate. But she had drawn a picture that morning and insisted I bring it—a butterfly with bright pink wings and the words “I’m strong now” written across the top. I kept it folded in my purse.

When the judge took his seat, the clerk read the charges: Attempted murder, aggravated assault of a minor, and administering a toxic substance.

Each word hit like a hammer.

Angela rose and began.

“Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, this case is not about an accident. It is about obsession, control, and the betrayal of trust. The defendant, Francine Holloway, poisoned her seven-year-old granddaughter over the course of six weeks. She did so with calculation and purpose, to create the illusion that the child’s mother was unfit.”

Then she turned to Francine.

“She did so because she could not bear to lose control.”

The first witnesses were the medical professionals.

Dr. Rasheed explained the toxicology reports, the elevated liver enzymes, the anti-coagulant buildup. He spoke clearly, his calm voice filling the room with scientific certainty.

“She was lucky,” he concluded. “Without intervention, the child would have died within days.”

Next came Detective Vega. He described the search—the locked cabinet, the journal, the boxes of rat poison, the scale. He held up one of the photos, projected large on the courtroom screen: Meadow, pale and bruised, sitting at Francine’s kitchen table with a half-finished glass of green smoothie in front of her.

The jurors flinched.

“This photo was taken three days before she collapsed,” Vega said. “It was found in the defendant’s phone gallery, labeled ‘Week Six.’”

Then came the hardest part—Francine’s journal.

Angela read it aloud, page by page, her voice steady, unflinching.

February 19 – M becoming more compliant. J suspects nothing. Appears tired at work—will strengthen case for custody.

March 1 – Slight bruising. Reduced dose to maintain plausible deniability. Called Wyatt again—no response. Must convince him she’s unwell under J’s care.

Each entry was a nail in the coffin of the illusion that Francine Holloway was a loving grandmother.

Wyatt sat motionless, tears cutting silent tracks down his face. When Angela finished reading, she placed the journal on the evidence table like a relic of something unspeakable.

During a recess, I stepped outside for air. The sky was gray, threatening rain, the courthouse steps slick with mist.

Reporters hovered like vultures, their microphones ready.

“Ms. Brennan, is it true your ex-mother-in-law tried to frame you?” one shouted.

I kept walking.

Another voice called, “How’s your daughter doing?”

That one I answered.

“She’s alive,” I said. “That’s all that matters.”

The afternoon session was for the defense. Francine’s attorney, a well-dressed man named Gregory Banks, tried to present her as mentally unwell, a woman “suffering from an undiagnosed delusional disorder.”

But Francine wouldn’t play the part.

When she took the stand, she sat up straight and spoke clearly, confidently, like she was lecturing a class on etiquette.

“I didn’t poison my granddaughter,” she said. “I gave her supplements—vitamins to strengthen her. My daughter-in-law is neglectful, overworked. The child was pale because she eats junk. I was correcting that.”

Angela’s voice was cool. “Mrs. Holloway, do you recognize this handwriting?”

Francine didn’t look at the screen. “It’s mine.”

“And these are your words? ‘Will reduce next dose to maintain subtle decline?’”

Francine’s chin lifted. “I was referring to natural remedies. Herbal medicine.”

Angela didn’t blink. “You wrote down gram measurements, Mrs. Holloway. Herbs aren’t measured in grams on a digital scale. Rat poison is.”

The courtroom fell silent.

Francine’s face stayed smooth, but her fingers tightened around the edge of the witness box.

“You’ve twisted everything,” she said. “All I ever wanted was to care for my family. My son is an alcoholic because of her—” she pointed at me—“and my granddaughter was becoming another casualty of her selfishness.”

Angela let her finish, then said softly, “So you decided to make the child sick to save her?”

Francine hesitated for the first time. “I… I was trying to help.”

“By feeding her poison?”

Francine didn’t answer.

When the defense rested, the prosecution called one final witness: Wyatt Holloway.

He walked to the stand slowly, his hands trembling slightly, but his voice was clear.

“I used to think my mother was perfect,” he said. “She made sure everyone else thought so too. But I was always sick as a kid. Stomach pains, fainting, random bruises. The doctors never figured it out.”

He paused, eyes on the floor. “Now I know why.”

Angela asked, “You believe your mother was poisoning you?”

“Yes. She made me dependent. Told me I’d never survive without her. When I met Jolene, it was the first time anyone encouraged me to stand on my own.”

He looked directly at his mother then.

“You couldn’t control me anymore, so you went after my daughter.”

Francine’s lips pressed into a thin line.

“I forgive you for what you did to me,” Wyatt said softly. “But not for what you did to her.”

The jury deliberated for one hour and forty-two minutes.

When they returned, the foreman’s voice was steady.

“Guilty on all counts.”

Francine didn’t move. Not a tear, not a word. Only the faintest flicker of disbelief crossed her face when the judge sentenced her to eighteen years in state prison.

“You are a danger to children,” the judge said. “Especially those who trust you.”

As the bailiff led her away, she turned her head once—just once—and looked straight at me.

There was no apology there, only the same cold fury that had been hiding behind her smile for years.

Afterward, reporters swarmed the steps again.

Cameras flashed, microphones thrust forward.

Someone shouted, “Do you feel justice was served?”

I stopped long enough to answer.

“Yes,” I said. “But justice doesn’t bring back peace. That’s something you have to rebuild yourself.”

The next months blurred together.

Therapy for Meadow. Court follow-ups. Nightmares that came without warning.

But slowly—miraculously—life began to steady again.

Wyatt stayed nearby, attending meetings, volunteering at a community center, proving every day that he wanted to be part of Meadow’s world.

Meadow herself began to smile again. She painted, laughed, played soccer. She still carried small shadows—the way she’d sniff her drinks before taking a sip, the hesitation around older women who reminded her of Francine—but each week those shadows faded a little.

Six months after the sentencing, Dr. Rasheed called with the best news of all.

“Her labs are perfect, Mrs. Brennan. No permanent damage. Physically, she’s in the clear.”

I thanked him, then sat at the kitchen table, staring at the sunlight spilling across the floor.

I realized I was breathing freely for the first time in a year.

That evening, Meadow sat on the couch with a fresh set of paints.

“What are you working on?” I asked.

She smiled. “A butterfly coming out of a cage.”

“It’s beautiful,” I said.

“It’s us,” she answered simply.

Later, after she went to bed, I stepped out onto the balcony. The city hummed below, alive and ordinary. For the first time, I didn’t see ghosts in every shadow.

Francine was gone, but her lesson remained:

that love twisted into control becomes poison long before it touches a glass.

I touched the folded butterfly drawing still tucked in my purse.

We had survived.

And survival, I realized, wasn’t about vengeance or fear.

It was about teaching my daughter that the world could still be kind.

Part 4

The months after the trial felt like standing on a bridge after a storm—everything was technically still there, but you didn’t quite trust the footing yet.

Every sound in the night made me jump.

Every text from an unknown number tightened my chest.

When you’ve lived through betrayal dressed up as kindness, ordinary peace feels suspicious.

But life, stubborn as it is, keeps going.

By spring, Meadow and I had moved to a different part of town—closer to the bay, smaller apartment, brighter light.

The windows overlooked a playground where kids’ laughter floated up every afternoon. At first, that sound hurt. It reminded me of all the Saturdays I’d spent thinking she was safe at her grandmother’s.

Now it felt like permission to start again.

I took a new job at a pediatric dental office—Dr. Watkins & Associates. The staff already knew our story from the local news, but they didn’t treat me like a headline. The first week, Dr. Watkins had quietly said, “We’re glad you’re here, Jolene. Take all the time you need to settle in.”

That simple grace nearly made me cry in the break room.

Meadow started at a new school, too. No whispers, no pitying looks. She made a friend her first day—a freckled girl named Bailey who loved painting as much as she did. The two of them became inseparable.

Every morning, Meadow would pack her butterfly lunchbox, sling her backpack on her shoulders, and say, “Bye, Mom! Don’t forget to smile at work!”

She’d run out the door with that lightness only children can summon after surviving something heavy.

Watching her go felt like watching a miracle learn to walk.

We kept seeing Dr. Patricia Morse, the child therapist who’d helped Meadow talk through the nightmares. Her office smelled of crayons and chamomile tea, a mix that somehow worked.

For the first few months, Meadow wouldn’t mention Francine. She talked instead about butterflies, about clouds shaped like dragons, about how she wanted to be an artist. Dr. Morse never forced the subject. She waited.

One afternoon, I was sitting in the corner during session when Meadow finally brought it up.

“Sometimes I dream about Grandma’s kitchen,” she said softly. “It’s pretty, but everything tastes bad.”

Dr. Morse asked, “What do you do in the dream?”

Meadow thought for a long moment. “I open the window. Then the bad air goes out.”

That image lodged in my chest—the window, the choice to let the poison leave.

When we got home that night, I opened every window in our apartment and let the sea breeze roll in. Meadow laughed, hair flying everywhere. “We’re letting the bad air go out,” she said.

Exactly.

Wyatt kept his promise.

He’d rented a small house two towns over, started working construction again, attended his recovery meetings faithfully.

Sometimes he’d stop by after work, still in his dusty boots, to take Meadow for ice cream. She’d come back sticky, smiling, always with a new story.

One night, he lingered at the doorway after dropping her off.

“She’s doing good, Jo,” he said quietly. “Better than any of us deserve.”

“She’s stronger than both of us combined,” I said.

He nodded. “I’m sorry—for everything I missed.”

I looked at him, really looked at him. His face was weathered, but his eyes were clear for the first time in years.

“You’re here now,” I said. “That’s what matters.”

We weren’t rewriting our marriage; some things are better left closed. But we were building something new—mutual respect, shared responsibility, maybe even friendship. It was enough.

Summer came early that year, the kind that smells like sunscreen and barbecues.

Meadow joined an art camp at the community center. Every evening she’d burst through the door with paint on her fingers and stories spilling out faster than I could keep up.

“Mom! Guess what? I painted the ocean, but with pink waves because they looked happier that way!”

She was reclaiming color, one brushstroke at a time.

As for me, I started running again—just short jogs along the waterfront before work. The rhythm of my sneakers on pavement became a meditation.

Each step whispered: you’re still here, you’re still here.

Sometimes I’d catch my reflection in shop windows—stronger posture, softer eyes—and hardly recognize myself. I wasn’t the woman hunched over a hospital bed anymore. I wasn’t even the woman who’d built her life around survival.

I was learning to live.

In late July, a letter came from the State Correctional Facility for Women.

The return address stopped my heart.

Inside, in perfect cursive, were five words:

“I want to see her.”

— Francine Holloway.

I showed it to my therapist before deciding anything.

“You don’t owe her that,” Dr. Morse said.

“I know,” I answered. “But part of me wants closure.”

We arranged a meeting—not for Meadow, only for me.

The prison visiting room was colder than any courtroom had been. Francine was older now, somehow smaller, her hair a dull gray instead of silver. The pearls were gone; her wrists bore the imprint of cuffs that had just been removed.

She looked up when the guard led me in.

“Jolene,” she said softly, as if greeting an old friend.

I sat across from her. “You wanted to see me. Say what you need to say.”

She folded her hands. “How is she?”

“She’s alive,” I said. “Thriving.”

Francine nodded slowly. “Good.”

A pause. “I loved her, you know.”

I leaned forward. “You loved control. You loved being needed. That’s not love.”

Her eyes glistened, but I wasn’t sure it was guilt. “I didn’t mean to hurt her.”

“You meant to own her,” I said. “And you failed.”

The silence that followed felt like the closing of a book.

When the guard signaled time was up, I stood.

“She doesn’t ask about you anymore,” I said. “And one day, she won’t remember your face. That’s mercy.”

Francine’s shoulders sagged. I walked out without looking back.

The next day, Meadow and I baked cookies—real ones, the kind that made the kitchen smell like vanilla instead of fear.

She wore my old apron, sleeves rolled up, face dusted with flour.

“Mom,” she said, tasting the dough, “this is how cookies are supposed to taste.”

“Exactly,” I said.

When we pulled them from the oven, she arranged them on a plate and carried them to the balcony. We watched the sunset together, eating warm cookies, our fingers sticky with sugar.

For the first time, the sweetness didn’t make me flinch.

That night, I sat at my desk and wrote a letter I would never mail.

Francine,

You almost destroyed three generations of your own family. You taught me what love isn’t, but you also taught me what it must be: honest, steady, free of poison and secrets.

Because of you, Meadow knows to trust her instincts. Because of you, I learned that strength isn’t control—it’s letting go.

You don’t get to define us anymore.

— Jolene

I folded it, slid it into a drawer, and felt lighter instantly.

By autumn, life felt ordinary again—beautifully, blessedly ordinary.

School lunches, dentist appointments, lost homework, bedtime giggles.

On Meadow’s eighth birthday, we threw a small party at the park. Balloons tangled in the trees, frosting stained everyone’s hands. When she blew out the candles, she made a wish, then whispered to me, “I wished for peace.”

“You already have it,” I said.

She smiled. “I know.”

That night, after the guests were gone, I tucked her into bed. She clutched her favorite stuffed rabbit—Mr. Buttons, newly cleaned, the poison long gone, the memories softened by time.

“Goodnight, Mom,” she murmured.

“Goodnight, baby. You’re safe.”

As I turned off the light, I realized that was finally true. Not a promise, not a prayer—just truth.

We were safe.

Part 5

Ten years later, the world had changed, and so had we.

I was forty-five now, older in the mirror but steadier behind the eyes. Meadow was seventeen—taller than me, with her father’s green eyes and my stubborn jaw. She kept her hair dyed a shade of copper that caught sunlight like fire and insisted it helped her “feel like a superhero.”

We lived in a small coastal town north of Portland, where mornings smelled like salt and cedar. I ran my own dental-hygiene practice three days a week and spent the rest teaching community-college classes in patient care. I never planned that career shift—it just happened, the same way healing does, slow and sideways until you realize you’ve been walking forward all along.

Meadow’s art had taken on a life of its own. She painted constantly—murals on school walls, canvases stacked against our living-room furniture, a series of butterfly portraits she called Metamorphosis.

Her teacher once told me, “Your daughter paints like she’s remembering something she lived through in another lifetime.”

She was right, in a way. Meadow’s butterflies weren’t delicate. They were bold, wings spread wide, pushing out of dark corners into light. When people asked about the theme, she always said, “Because they survive the ugly part before they get beautiful.”

I didn’t correct her. She understood more than most adults ever would.

It was early March when a letter arrived from the Oregon Department of Corrections.

Francine had been denied early release due to health reasons but was eligible for hospice transfer.

The envelope trembled in my hands. Ten years, and still, her handwriting found me—clean loops, perfect spacing.

I’d like to see Meadow before I go.

I read it three times before placing it on the counter.

When Meadow got home from school, she found me staring at it.

“What’s that?” she asked.

“Your grandmother wrote,” I said carefully. “She’s very sick. She wants to see you.”

Meadow frowned, studying my face. “Do you want me to?”

“I want you to choose.”

She thought about it for a long minute, then said, “If I go, it’s not for her. It’s for me. I want to see what she looks like when she can’t lie anymore.”

The hospice wing smelled like antiseptic and lavender air freshener. The nurse led us to a small room with a window overlooking the courtyard. Francine lay there, frail, her once-silver hair thinning, her face pale against the pillow.

When she opened her eyes, recognition flickered. “Meadow,” she rasped.

Meadow stood tall, shoulders squared. “Hello, Grandma.”

I waited by the door, letting her lead.

Francine’s gaze drifted to me, then back to Meadow. “You look… healthy.”

“I am,” Meadow said. “You almost took that from me.”

Francine’s hand trembled. “I wanted to protect you. I didn’t know how else—”

“You knew exactly how,” Meadow interrupted, voice calm but strong. “You hurt people and called it love. But love doesn’t mean making someone sick so they’ll need you. It means helping them fly even when it scares you.”

Francine’s eyes filled, but her words came out flat. “I don’t expect forgiveness.”

“Good,” Meadow said quietly. “Because it’s not yours to expect. But I don’t hate you either. I’m done carrying you.”

She turned to me. “Can we go now?”

I nodded.

Francine whispered something as we left, a sound halfway between a sigh and a prayer.

I didn’t turn back. Some doors, once closed, stay that way.

That fall, Meadow was invited to give a short talk at an art-therapy conference in Seattle. The theme was Transforming Trauma Through Creation. She stood on stage in jeans and a paint-stained jacket, her voice steady over the microphone.

“When I was little,” she said, “someone tried to control me by making me sick. My mom taught me that the best revenge is living free. So I paint butterflies, because they start trapped but end up flying anyway.”

She showed slides of her work—brilliant colors, sweeping motion, wings made of broken glass and light. The room was silent. Then applause rolled through it like a wave.

Afterward, people came up to hug her, thank her, tell her their own stories.

Watching her, I realized that what Francine meant for destruction had turned into purpose. My daughter wasn’t just surviving anymore. She was teaching other people how to survive, too.

The next spring, we planted a small garden behind our house—tomatoes, lavender, a patch of milkweed for butterflies.

The first time we saw one land on the blossoms, Meadow grinned. “See? They always find us.”

That summer, she left for college with a scholarship to study art therapy. I helped her pack, taping boxes labeled Paints, Sketchbooks, Coffee Mugs.

When she hugged me goodbye, she said, “Mom, you don’t have to worry anymore.”

“I’ll always worry,” I laughed, brushing hair from her face. “That’s in the job description.”

She smiled. “Yeah, but now it’s the normal kind.”

Watching her drive away was both heartbreaking and holy.

She was free.

We both were.

I kept the garden.

I still ran by the water most mornings, still drank coffee from the same chipped mug I’d had since the old apartment. Some habits survive everything.

One evening, I found an old photo in a drawer—Meadow at six years old, missing tooth, hair in braids, holding a jar with a captured butterfly inside.

On the back, in my handwriting: “Let it go tomorrow.”

I smiled, set it back down. We had.

A month later, another envelope arrived.

Inside was a brief note from the prison chaplain.

Francine Holloway passed away peacefully last week. She left no requests for services. Personal effects have been destroyed per protocol.

I folded it once, placed it in the trash, and felt—nothing. No triumph, no sadness, just finality.

Some stories don’t end with fireworks; they fade like smoke once you stop feeding them air.

On a warm July evening, I sat on the porch with a glass of lemonade, the air thick with honeysuckle. Across the street, a little girl rode her bike, her father jogging beside her, laughing when she wobbled.

That sound—the ordinary sound of safety—brought a lump to my throat.

I thought of Meadow at that age, of every goodbye wave from the window, every moment I had trusted the wrong person. Then I thought of who she’d become because of it: strong, compassionate, unafraid to name darkness for what it was.

Maybe that’s what real love does.

It breaks, it rebuilds, and it teaches you to open the window and let the bad air go out.

I looked up just as a butterfly landed on the porch rail, wings glowing orange in the fading light.

“Hey there,” I whispered. “You made it.”

It lifted off, vanished into the dusk, and for the first time in years, I realized I wasn’t watching for danger anymore.

I was watching for beauty.

THE END

News

CH2 – Came Home From a 40-Minute Jog to Find HOA Staff Inside My House — I’m Not Even in the HOA!…

Part I I hit stop on my running app at 7:42 a.m., lungs burning, the sound of my sneakers crunching…

CH2 – My mom introduced me as her “disappointing daughter.” Then FBI agents arrested her colleague…

Part I I was forty-two years old the night my mother introduced me to a room full of Washington power…

CH2 – The American Pilot Searched 40 Years for the Enemy Who Saved Him — Then They Became Brothers…

Part I The engines of the B-17 bomber Ye Olde Pub trembled against the December wind as it climbed through…

CH2 – Nobody From My FAMILY Came To HOSPITAL “Not Even My HUSBAND” Nor My Closest — Then Nurse…

Part 1 The fluorescent lights above hummed in an even rhythm, a sound so constant that after a while, I…

CH2 – I Heard My Fiancé Tell Friends: “It’s Just Business. Her Money, My Looks.” I Texted: “Your Mic’s On.”

Part One: My name is Bonnie Tony, and until a few months ago, I thought my life was exactly where…

CH2 – HOA Banged on My Door at 6AM—My Day Off I Fired Warning Shots. They Sued I Won Big…

Part One At 6:04 in the morning, my doorbell camera caught a cardigan silhouette whacking my door with a clipboard…

End of content

No more pages to load