May 8, 1945

Outside Darmstadt, Germany

The war in Europe was over.

Officially, it was V-E Day. In London, crowds were already spilling into the streets, singing and dancing and kissing strangers under strings of flags. In New York, newspaper boys were probably out on corners, yelling headlines at the tops of their lungs, arms stained with ink. Somewhere in Washington, someone was uncorking good bourbon in crystal glasses.

But in a dusty field outside the ruined German city of Darmstadt, nobody was celebrating.

Not yet.

The field was just a flat patch of trampled grass and dirt, the kind of nowhere place armies create without meaning to. The smell of smoke from the city hung in the damp air, mixed with the sour odor of diesel, sweat, and old fear. To the east, the jagged teeth of bombed-out buildings broke the horizon. To the west, a line of American trucks idled, exhaust ghosting out in white puffs.

In the middle of the field, 38 women sat on the ground in two neat rows, knees drawn up, arms wrapped around shins as if their own bodies were the only shelter left.

They still wore the gray uniforms of the Wehrmacht auxiliaries—skirts wrinkled and stained, tunics hanging loose over frames that had dropped weight month by month. Their hair was cropped short under caps stripped of insignia. Their faces were thin, cheeks hollowed, eyes too large.

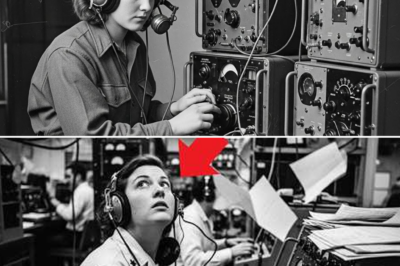

Some had been volunteers. Some had been conscripted. All of them had been “Luftnachrichten-Helferinnen”—signal corps girls. For years, they’d operated radios, telephones, and radar stations while men fought and died further north, further east, further west. They’d been told they were part of something glorious.

Now they were prisoners.

American GIs in olive drab stood around them in a loose circle, rifles slung or held at ease, shoulders slumped with the particular exhaustion of men who’d been told the war was over but whose bodies hadn’t gotten the message yet.

The women waited.

They’d heard stories—every rumor that seeped through dugouts and barracks and nights around stoves when someone had a scrap of paper with news on it. Stories of Soviet troops and what they did to women from Berlin to Königsberg. Stories of French partisans with knives. Stories of Americans too, though those were more scattered: reprisals, beatings, justice from the barrel of a gun.

They didn’t let themselves hope for anything else.

German girls had been taught a lot of things about the Fatherland, about Hitler, about unshakable victory. None of that had survived the last six months. The only lesson that still felt solid was the one whispered from mother to daughter for generations.

When the world ends, be quiet.

When men are angry, be small.

So they sat in rows, backs straight, eyes down. They waited for the shouting to start, for the blows, for whatever came next.

Instead they heard English.

“Sergeant, bring the kitchen truck up.”

The voice belonged to a young American officer standing a few yards away, one hand resting lightly on the butt of his sidearm, the other holding a clipboard. His helmet sat a little crooked on his head. His face, under a smear of road dust and dark stubble, was surprisingly young. Twenty-four at most. His uniform jacket bore the insignia of a first lieutenant.

His name was Daniel O’Connell.

He was from Texas, he had a drawl as slow as summer heat, and he had seen too much in the last month to ever be properly young again.

He’d been at a camp outside Buchenwald ten days earlier. He’d watched men in striped uniforms stare at him with eyes that didn’t look real. He’d watched his own soldiers, tough kids from Kansas and Brooklyn and Alabama, take off their jackets in the cold and put them on skeleton-thin survivors. He’d watched those same soldiers hand over their rations—chocolate bars, cans of meat, mustard packets—without being asked.

He’d also seen bodies piled like wood, and he’d smelled the burned-sweet stench that clung to everything and would never really leave his head.

He looked at the women in gray.

They were the enemy on paper. Their uniforms said as much. They’d helped run the machine he’d spent three years of his life trying to destroy.

But they were also 18, 19, 27, 22. They had cheekbones and chapped lips and hands that shook in the cold. They reminded him of his kid sister back in San Antonio, the one who wrote him letters about driving the tractor and sneaking lipstick past their mama.

He took all of that in, weighing it with a tired, human kind of calculus.

These women didn’t look like people who needed another beating.

They looked like people who needed dinner.

“Sergeant?” he repeated without turning his head.

“Yeah, LT?”

“Get the kitchen trucks up here. Both of ’em. Set up right there,” he said, pointing to a patch of level dirt behind the lines of women. “I want hot food for every one of these gals. And our boys too, if there’s enough left.”

The sergeant—a tall, narrow man from Ohio named Parsons—blinked.

“The kraut ladies?” he asked, more out of surprise than protest.

“Yeah,” O’Connell said. “They’re in our custody now. We feed our prisoners. That’s how it works.”

Parsons hesitated for half a second, then shrugged.

“Yes, sir.”

He walked off toward the trucks, cupping his hands to shout over the engine noise.

The women in gray watched, confused.

They’d seen American field kitchens from a distance the previous day, big green metal boxes on wheels with chimneys. They’d watched steam rise from them, smelled something savory on the wind as American units moved through the area, feeding their own.

They’d never imagined those kitchens would roll toward them.

Ten minutes later, they did.

Two GMC trucks backed into place, men in stained aprons jumping down as the vehicles rocked to a stop.

The smell hit the German women like a physical blow.

Coffee.

Real coffee. Not the bitter grain-based Ersatz they’d been drinking, if they were lucky, for the last three years. Not burned barley or chicory. Real roasted coffee, dark and rich, cut with canned milk and sugar.

Something frying—Spam, though they didn’t have a word for it yet. Meat, unmistakably. Salty and sizzling.

Powdered eggs scrambled in vats, steam billowing out in rolling waves.

Biscuits baking in field ovens, their yeasty, buttery smell carried on the cool evening air.

For a moment, nothing happened.

Smell was memory.

Smell was hunger.

Smell was everything.

Some of the women’s eyes flooded with tears without their permission. They pressed lips together, trying not to let anything show. Others swayed where they sat, lightheaded.

The last official ration they’d received from their own side had been three days earlier: a tin cup of watery soup and a slice of something that might once have been bread before sawdust got involved. Before that, it had been sporadic. There had been days of nothing.

The idea that these same Americans they’d been told were monsters would devote this much food to feeding them seemed grotesque.

Cruel, even.

A trick.

Lieutenant O’Connell didn’t waste time.

He pulled a pen from his breast pocket, clicked it, and walked along the rows of women, the interpreter trotting beside him. The interpreter, a German-speaking private from Chicago, was the son of Bavarian immigrants and looked like he could’ve gone to school with half these prisoners.

O’Connell stopped in front of the first woman in the row, a slight figure who looked more like a girl than a soldier. Her hair, under her cap, was the color of straw. Her coat hung off her.

He glanced at the roster on his clipboard.

“Name?” he asked.

The interpreter translated.

“Name?” he repeated in halting German. “Wie heißen Sie?”

“Erika,” she whispered. “Erika Müller.”

“Where you from, Miss Erika?” he asked.

“Hamburg,” she said, eyes flicking up for just a second. They were blue, framed with lashes clumped by dirt and tears. “I was… I am… Funkerin. Radio operator.”

O’Connell nodded, pen scribbling.

He moved down the line.

“Any of you wounded? Sick?” he asked, voice raised just enough to carry.

The interpreter echoed him.

Several women lifted hands hesitantly—one limping, one with a bandage visible under the sleeve, one with a wet, rattling cough.

He marked them, made a note: medic.

Then he walked toward the kitchen trucks.

“Load me a tin,” he told the sergeant.

“A big one.”

The cook looked between him and the line of German women, then shrugged and grinned. He scooped scrambled eggs with a ladle, piled two biscuits on top, cut a thick slice of Spam and laid it over the eggs like a slab of pink armor. He added a spoonful of syrupy peach jam from a ten-in-one ration tin.

“Looks better’n what I got at home,” the cook said.

“Don’t let my mama hear you say that,” O’Connell said. “She’ll come over here and whup you herself.”

He took the mess tin and carried it back toward the rows.

The first woman, Erika, watched him approach.

She watched the steam rise, watched the yellow of the eggs and the tan of the biscuits and the unbelievable shine of butter glistening on top. Her throat worked as she swallowed, but she told herself not to reach, not to beg.

That wasn’t how this went.

The conquerors ate.

The conquered watched.

When O’Connell stopped in front of her and held the tin out, she froze.

He smiled. A small thing, no teeth, but it softened his face, shaved a few years off.

“Essen, bitte,” he said, his German clumsy but understandable. “Eat, please.”

She stared at the tin as if it were a mirage.

“This… for me?” she asked in German.

The interpreter translated.

“For you,” O’Connell said. “And for the others. Eat.”

Her hands shook when she reached up. The metal was hot against her palms. For a second, she just held it, feeling the warmth seep into her fingers, up her arms, into parts of her that had been cold for months.

She took a bite of the eggs.

The texture alone—soft, moist, rich—was a shock.

The taste…

Her eyes closed.

The field fell away.

For a heartbeat, it was 1939 again and she was in her mother’s kitchen on a Sunday morning, the smell of eggs and butter and coffee filling the air as her father came in from checking the hens. There had been laughter. A radio playing. No uniforms.

“This is the best food I’ve ever had,” she whispered.

She wasn’t sure if she said it out loud or just thought it. The interpreter heard enough to catch the gist and glanced at O’Connell.

“She likes it,” he said.

O’Connell didn’t catch the words, but he didn’t need them. He saw the look on her face.

He nodded, stepping to the next woman and the next.

Soon every prisoner had a full tin.

Some stared at the food, unable to believe the Americans wouldn’t snatch it away the moment they reached for it. Some ate slowly, reverently, as if they were in church and this was sacrament. Some ate so fast they choked, coughing and crying at the same time, hands clamped around their tins like they’d fight anyone who tried to take them.

The GIs stood by, watching.

War had a way of hardening you.

So did twenty-mile marches, two-day firefights, seeing a buddy you’d been playing cards with the night before lying facedown in a ditch.

It also had a way, every once in a while, of cracking you open.

One private, a kid from Ohio with freckles and a Lucky Strike tucked behind his ear, reached into his jacket pocket and pulled out a Hershey bar he’d been saving. He hesitated, then walked over to the nearest woman and held it out without a word.

She blinked, eyes switching from his face to the chocolate and back as if she didn’t understand the transaction.

“Schokolade,” he said, the word awkward in his American mouth.

She took it, fingers brushing his.

“Danke,” she whispered.

Another GI lit a cigarette, took one drag, then passed it down the line. Each woman took a pull, savoring the acrid smoke, the familiar ritual of nicotine and nerves. The second GI pulled another from his pack and lit that one for himself.

The air filled with cigarette smoke and the sound of metal spoons scraping tin.

Private Ruth Becker, twenty-one, from Munich, sat in the second row, two places down from Erika. Her hair, once long and braided, was hacked short just below her ears. She’d been part of a telephone unit in Munich that had been bombed out twice in the last year. The second time, she’d spent six hours trapped in a cellar with another operator and a dead man they couldn’t move.

She held her tin in both hands, savoring the simple fact that it had weight.

Butter.

That was the thing that undid her.

Real butter.

She hadn’t seen any since 1942, when her mother had scraped the last of their ration from a paper wrapper and spread it thinly on four pieces of bread, one each for her and her three siblings, pretending not to notice there was none left for herself.

Now Ruth spread butter thick on the biscuit with the dull edge of her knife. It melted into the bread in little golden streams. She took a bite.

Fat.

Salt.

Warmth.

She licked the knife clean, unwilling to leave even a smear behind.

Then the tears came, hard and fast.

Not polite, not pretty.

Her shoulders shook. She tried to swallow and couldn’t. Egg and biscuit sat like stones in her throat.

“Ruth?” Erika murmured beside her. “Was ist—?”

“I thought I’d never taste this again,” Ruth sobbed, clutching the tin to her chest. “I thought—”

Her words dissolved into hiccups. She let the tears fall, hot tracks cutting through the dirt on her cheeks, mixing with the grease on her lip.

Corporal Ilsa Klene, twenty-seven, sat at the end of the front row, the oldest of the lot by a few years. You could see the difference in the fine lines at the corners of her mouth, the way she held herself with the practical distance of someone who’d changed nappies and buried a husband.

She had two boys somewhere in Germany that she hadn’t seen in two years.

She didn’t even know if they were alive.

She raised the tin cup of coffee to her lips and took a careful sip.

Coffee, real coffee, with canned milk and sugar. Not the thin black liquid she’d gotten twice a week in the last months, each cup an embarrassment to the word.

She inhaled.

Her eyes closed.

“Donner,” she whispered. Thunder. She used it the way some people said “my God”—a breath of disbelief and gratitude.

She took another sip, let it sit on her tongue.

For the first time in three years, she didn’t feel quite so much like she was carrying the world on shoulders that weren’t broad enough for it.

On the second sip, she started whispering something else under her breath.

“Danke. Danke. Danke.”

Thank you.

She wasn’t sure who she was thanking—God, the Americans, the cook, the lieutenant, fate—but the word felt right in her mouth.

The GIs watched all this with a strange mix of curiosity, pity, and something like shame that they’d ever thought about just tossing these women onto trucks and forgetting about them.

“LT?” Sergeant Parsons murmured, walking up beside O’Connell. “You wanna see this?”

He held out his own mess tin.

He’d taken one of the biscuits and slathered it with peach jam, then stuck a Hershey bar into the mush for good measure. It looked like something a ten-year-old would invent.

Ruth, cheeks still wet, stared at it.

Parsons winked.

“In America, we call this a heart attack,” he said to no one in particular.

The interpreter tried to translate, stumbled over “Herzinfarkt” in the context of whipped sugar. Ruth’s mouth quirked despite herself.

Her shoulders relaxed just a little.

In that moment, for half a breath, she was a girl at a fair again, not a prisoner of war.

Lieutenant O’Connell sat down on the ground near the front row, crossing his legs, resting his forearms on his knees. It put him at eye level with them.

His boys glanced at him, then followed suit, dropping down here and there in the circle. It was a small shift, but it changed the shape of the space. It was no longer just guard and guarded, standing and seated. It was people near people.

“Ask them where they’re from,” O’Connell said.

The interpreter relayed the question.

“Hamburg,” said Erika.

“Munich,” said Ruth.

“Bremen,” “Leipzig,” “Cologne,” “a village outside Dresden,” came the answers down the line.

“What’d y’all do in the war?” O’Connell asked, more gently this time.

Radar.

Telephones.

Morse code.

Call signs and cables and listening to what came over the wires, day after long day.

“And families?” O’Connell asked. “Kinder?”

At that, something in the women tightened again.

“Yes.”

“No.”

“He’s at the front. Or was.”

“My husband is missing at Stalingrad.”

“I left my children with my mother when they evacuated the city.”

One of them, a girl with freckles and a chipped tooth, blurted out, “My brother was in the U-boat service. I haven’t heard from him since last autumn.”

Her voice shook on the last word.

No one asked the obvious follow-up.

Silence hung in the air for a moment.

Then O’Connell spoke, his own voice softer than it had been since Omaha Beach.

“I got a little sister back home,” he said to the interpreter. “Twelve years old. She’s ornery as all get out. Thinks she can drive daddy’s tractor better than he can. Maybe she can.”

He waited for the translation.

The women listened.

Some of them smiled, small and unwilling.

“She wrote me a letter last month,” he continued. “Said she nearly ran over my mama’s chicken ’cause she was trying to show off. Mama scolded her something fierce. Daddy thought it was the funniest damn thing he’d ever seen.”

“Verdammtes Ding,” the interpreter said, approximating “funniest damn thing” as best he could.

The women actually laughed at that—short, broken sounds, but real.

They sat there, sipping coffee, eating biscuits with too much butter, smoking American cigarettes, and listened to a man who, yesterday, would’ve been their sworn enemy talk about a Texas farm as if it were the most important thing in the world.

It was dark by the time the last tin was collected.

The temperature dropped.

A few of the GIs pulled blankets from the trucks; they handed one to each woman. Real wool, Army-issue, tan and scratchy, smelling faintly of mothballs and the inside of a duffel bag.

“Das ist für Sie,” one private said, proud of his phrasebook German. “Für die Nacht.”

For you. For the night.

The women clutched them like lifelines.

“Where we go now?” one of them asked, voice barely more than a whisper.

The interpreter glanced at O’Connell.

“You’ll sleep in a barn tonight,” he answered. “Under guard. But with a roof. Straw. Tomorrow, you’ll be processed. Sent to a camp. But for now?”

He looked at the field, at the dark shape of the barn beyond, at the moon rising over the ruins of Darmstadt.

“For now, you sleep,” he said.

Before they were led away, each woman was given a small paper bag, folded at the top.

Inside each bag:

Two Hershey bars.

A pack of Lucky Strikes.

A tin of Spam.

And a handwritten note, in German, translated by the interpreter and penned slowly by O’Connell, his printing blocky and careful.

Sie haben Ihre Pflicht getan. Wir haben unsere getan. Der Krieg ist vorbei. Willkommen zurück in der menschlichen Rasse.

87. Infanteriedivision, U.S.A.

You were doing your duty. We were doing ours. The war is over. Welcome to the human race again.

The women turned the notes over in their hands as if they were made of something fragile.

Some tucked them into pockets.

Some slipped them into boots.

A few pressed them against their chests for a second as if they were something worth praying over.

They walked toward the barn, wrapped in blankets and the first real fullness they’d felt in their stomachs in months.

Behind them, the field kitchen clanged as men cleaned up.

Lieutenant Daniel O’Connell scrubbed at a pan with a sponge, shoulders aching, thinking about how his mama would react if she could see him now—feeding nineteen-year-old German girls like they were neighborhood kids.

He decided she’d probably approve.

Three Women, Three Lives

The war ended, but the story didn’t.

History books would write about V-E Day in terms of grand strategies and moving arrows on maps, about Yalta and surrender documents and flags raised over capitals.

The lives launched from that dusty field outside Darmstadt didn’t make those pages.

They unfolded quietly, like every other ordinary miracle.

Erika Müller – Wisconsin

Erika kept the note.

She folded it carefully that first night in the barn and tucked it into the hem of her underskirt, sewing a small stitch to keep it safe. Through processing, through transport to a POW camp in France, through bouts of illness and long days of boredom and the endless, gnawing uncertainty about what her future looked like, the note stayed with her.

She took it out when things were particularly bad and traced the letters with her fingertip.

Willkommen zurück in der menschlichen Rasse.

Welcome back to the human race.

It felt, sometimes, like a permission she hadn’t known she needed.

She’d joined the Luftnachrichten service at eighteen, swept up in slogans and smart-gray uniforms and the idea of being part of something bigger than herself. By the time the war first turned truly ugly, it was too late to just walk away.

She’d followed orders—patched through calls, sent coded messages, scribbled frequencies.

That was duty.

What the Americans had shown her in that field was something else entirely.

Grace.

Four years later, in 1949, Erika boarded a ship for a different country. She had a visa, a suitcase, a new last name she was still getting used to pronouncing in English without blushing.

She married an American sergeant she’d met at a post-war dance, a man from Wisconsin who’d fallen in love with her quiet humor and the way she tilted her head when she listened.

His name was Tom Parker.

Green Bay was cold in a different way than Germany had been. The snow there came down in fat, heavy flakes that stuck. The town smelled of paper mills and cheese.

She learned to make biscuits from her mother-in-law, who didn’t measure anything and added more butter than any recipe ever called for.

Every Christmas, Erika made them for her children and, later, her grandchildren.

Too much butter, too much jam.

They’d laugh and tell her she was spoiling them.

She’d smile and say, “Wait until you’re my age. Then you can decide how much butter is enough.”

When her youngest granddaughter once asked, “Oma, why do you always cry a little when you make biscuits?” Erika wiped her eyes with the corner of her apron, laughed, and said, “Because the first time I tasted this again, I wasn’t sure I was still alive. And sometimes, when you have a lot to be grateful for, your eyes leak. That’s all.”

Then she’d tell them the story of the field and the Texan lieutenant who’d looked at a bunch of hungry German women and decided they deserved scrambled eggs and Spam as much as any American soldier.

The note, by then faded and fragile, hung in a frame in her kitchen, next to a small, embroidered sampler that read, “Bless this house.”

The handwriting was still blocky, still careful.

Ruth Becker – Bremen

Ruth did not leave Germany.

She went back to Munich first, moved through a city that looked like it had been dropped from a great height and cracked. Her parents’ apartment building was gone, replaced by a smudge of rubble and rebar.

She cried once, standing in what had been their street.

Then she stopped, because there were too many people crying already.

She found work three towns over, in a bakery that still had glass in the windows.

The first time she saw a slab of butter on a counter again—real butter, pale gold, cool and firm under the knife—she had to excuse herself and sit in the back room for five minutes until the shaking passed.

She made herself touch it every day after that.

She kneaded dough and rolled it out and cut circles and baked them, experimenting with ratios of fat to flour until she got the texture right, until she got the taste so close to that first American biscuit that it made her chest hurt.

In 1952, she opened her own shop in Bremen.

She named it “Danke 1945.”

People asked her, sometimes, “Why 1945? The war ended then. That was a terrible year.”

She’d smile, dusted in flour, hair pulled back under a scarf.

“For me, 1945 is when someone I’d been told was my enemy fed me as if I was his daughter,” she’d say. “Sometimes a year is not all one thing.”

Her biscuits became famous, at least locally.

She served them with jam, with butter, with chocolate, with nothing at all.

She kept a small framed photo behind the counter—a black and white shot of GIs in a field kitchen, taken by someone with a Kodak who’d had a bit of film left.

On the back of the frame, she’d taped the note.

When her own daughter asked one day, “Mama, why do you never let anyone throw away old bread? You always turn it into something else,” Ruth kissed her forehead and said, “Because I know what it’s like to be hungry. And because food thrown away is a sin to someone, somewhere, even if you don’t know who.”

Ilsa Klene – Reunited

Ilsa spent her first months as a prisoner thinking almost exclusively of two faces.

Hans and Karl.

Seven and four the last time she’d seen them, both sweet and stubborn in different ways: Hans with his serious questions, Karl with his outrageous giggles. They’d been evacuated from their village outside Dresden when the air raids intensified.

Her own mother had taken them on a packed train, clutching their small hands and a suitcase full of things she’d thought important then—photographs, a Bible, an extra pair of socks.

When Ilsa had been conscripted into the signal corps, she’d told herself she was doing it for them. If she helped keep the enemy bombers away, they’d be safer.

It hadn’t worked out that way.

For two years, she’d gotten sporadic letters, cramped writing on cheap paper. Then, nothing.

After the war, when she was released to civilian life with a ration card, a few coins, and a pat on the shoulder, she started to search.

She followed rumor and ink.

She queued at Red Cross desks, wrote to displaced persons offices, stood in lines that moved too slowly in cities that seemed to exist only as lists of missing and found.

In 1947, in a DP camp outside Leipzig, she saw a name on a sheet tacked to a bulletin board.

Hans Klene, age nine.

Her heart stopped and tried to climb out of her throat.

The room spun.

She made a sound halfway between a laugh and a sob that made people turn to look at her.

Two hours later, she stood in front of a thin boy with familiar eyes, his hair longer now, his face sharper.

“Kinder?” she whispered. Children.

“Mama?” he said, and then he was in her arms, clinging hard enough to leave bruises.

Karl appeared five minutes later, dragged from a game of marbles, stopping dead when he saw her.

“Mutti is crying,” Hans said, voice awed.

“Mutti cries because God is stupid,” Karl announced, then got smacked lightly on the back of the head by his brother and threw himself into his mother’s embrace.

The first real meal Ilsa cooked for them in the small, drafty room they were assigned in a rebuilt apartment block was scrambled eggs with Spam.

The eggs came from powdered surplus donated by Americans.

The Spam did too.

She’d stood in the tiny shared kitchen stirring, the smell rising, boys hovering near, asking when, when, when.

They each ate three helpings, eyes wide, stomachs stretching around food that wasn’t turnip-based.

“Mama, why are you crying into the pan?” Hans asked on his second biscuit, watching her swipe at her face with the back of her hand.

“Because it took too long for this day,” she said. “And because not all tears are sad, hanschen.”

She kept her note from the Americans folded in her Bible, between Psalm 23 and a pressed clover.

Welcome to the human race again, it said.

Every time she opened that page, she thought of the Texan lieutenant’s face, of coffee with canned milk, of her boys’ faces smeared with egg and Spam.

1978 – Darmstadt

Thirty-three years after that night in the field, the city of Darmstadt had grown back over its scars.

New buildings filled gaps where old ones had once stood. Trees planted in the early fifties were tall and leafy, their roots digging into a soil that had once held shrapnel.

In the same field where the 38 women had once sat in rows on the ground, someone had put up a small memorial plaque in the seventies—a generic thing about displaced persons and the end of the war, the kind of marker you walked by without really seeing.

On a cool spring day in 1978, twenty-one women gathered around it.

They were in their fifties now, most of them. Some wore their hair short, some let it curl around their shoulders. A few had American husbands beside them; others had German spouses, children, grandchildren tugging at their sleeves.

You could see the field in their eyes even if you hadn’t been there.

Erika stood next to a tall man with a Wisconsin accent and a Packers cap. Her grandchildren darted around her legs like birds.

Ruth leaned on her cane, her hands still capable in that way bakers’ hands always are. Her middle-aged son held her elbow when the ground turned uneven.

Ilsa had Hans on her right and Karl on her left. Both taller than she was now. Both with families of their own. She insisted on walking under her own power.

They’d found each other through letters and rotary phones.

One had tracked down another, who had remembered a third, who had somehow found the name of the Texas lieutenant and written to the American Legion post that might have known where he’d gone. Turned out, he’d died ten years earlier, a heart attack in a San Antonio grocery store.

His widow hadn’t come.

His daughter had.

They stood in a loose circle around the spot where, once, two field kitchens had rolled up and changed the trajectory of their lives.

One of the women—now a retired schoolteacher in Stuttgart—held a small wreath. They laid it gently at the base of the plaque.

Then, one by one, they took out the notes.

Some were creased and browned, the edges threatening to crumble.

Some were laminated, preserved by husbands who’d understood how important they were.

Erika’s was in a fresh frame. She’d brought it down from Wisconsin in her carry-on luggage, wrapped in a sweater.

They read the words aloud, each in turn.

Their voices overlapped, echoed.

“You were doing your duty. We were doing ours. The war is over…”

“…Welcome to the human race again.”

When it was done, there was a long silence.

A car drove by in the distance.

A dog barked.

Someone’s grandchild giggled and was immediately hushed, then shushed back into acceptable levels of decorum.

Finally, Ruth cleared her throat.

“This was the best food I ever had,” she said quietly in German, and then repeated in halting English, looking at the lieutenant’s daughter. “The… first American meal. I never forget.”

The younger woman—Laura O’Connell, forty now, with her father’s eyes and her mother’s hair—smiled through tears.

“My daddy used to talk about that day,” she said. “Not often. But when he did, he’d say, ‘You can’t hate someone you’ve fed. Not the same way.’”

Ilsa nodded.

“Peace begins many places,” she said. “On paper, yes. At Yalta, in… how you say… treaties. But also here. With eggs. With biscuits. With coffee.”

Her grandchild tugged at her hand.

“Oma, what is Spam?” he asked, nose wrinkled.

She laughed, a full, rich sound.

“It is… American mystery meat,” she said. “Very salty. Very good when you have been hungry a long time.”

They lingered there until the shadows grew long.

Then they walked back toward buses and cars and lives.

The field stayed.

The note stayed, at least in memory if not in paper forever.

Somewhere on a base back in the States, maybe, there was a faded photograph of a young lieutenant with a Texas drawl looking sheepish in front of a field kitchen.

Somewhere in Wisconsin, the smell of biscuits with too much butter filled a kitchen every Christmas.

Somewhere in Bremen, a bakery called “Danke 1945” was closing up for the night, its owner flipping the chairs onto tables, counting receipts, humming under her breath.

Somewhere near Dresden, two grown men sat at their mother’s table, eating scrambled eggs and Spam out of nostalgia, watching her watch them like she still couldn’t quite believe they were there.

And for twenty-one women who had once sat on a cold spring field in gray uniforms, that day in May 1945 would never just be V-E Day.

It would be the day the enemy fed them like daughters.

The day someone handed them a plate of scrambled eggs, a biscuit dripping with butter, a tin cup of coffee, and a piece of paper that said:

The war is over. Welcome back.

Long after the uniforms were gone, after the flags had been folded and the parades had ended, that taste stayed with them.

Eggs.

Butter.

Spam.

Coffee.

And the sound of English spoken with a Texas twang saying, awkward but sincere:

“Essen, bitte. Eat, please. You’re home now.”

THE END

News

Sister Mocked My “Small Investment” Until Her Company’s Stock Crashed

If there’s one thing I learned growing up Morrison, it’s this: Thanksgiving at my parents’ estate was never about…

CH2 – They Mocked His Canopy-Cracked Cockpit Idea — Until It Stopped Enemy Fogging Tactics Cold

February 1943. The Spitfire clawed its way up through the gray over the English Channel, engine howling, prop biting…

My Grandson Called Me From The Police Station Saying “Coach Webb Beat Me… But They Think I Att…”

In thirty-eight years as an educator, I learned that phone calls after midnight never bring good news. Parents don’t…

IN COURT, MY SON POINTED AT ME AND YELLED, “THIS OLD WOMAN JUST WASTES WHAT SHE NEVER EARNED”

If you had told me that one day my own child would stand up in a courtroom, point at…

How an 11-Second Signal From a Farm Girl Prevented 38,412 Deaths in a Valley Built to Kill

At 05:46 in the morning, under a low ceiling of fog rolling across the French bocage, an entire Allied…

My Fiancée’s Dad Called Me “Trash” at Dinner—Then Begged Me Not to Cancel the Merger…

The champagne flute hit the marble floor like a gunshot. Crystal shattered, Dom Pérignon arced in a slow-motion spray…

End of content

No more pages to load