The night wrapped itself around Bastogne like a fist.

It was January 17th, 1945, 0320 hours, and the world, as far as Private James Mitchell could see, ended in a black line of trees about three hundred yards away. Beyond that line, the Ardennes forest was just a darker shade of darkness. Above him, the sky was a solid, star-pricked slab of cold.

He couldn’t stop shaking.

Some of it was the temperature. It was fifteen below and still falling, the sort of cold that didn’t just bite—it burrowed, climbed up your sleeves and down your collar and took possession of your bones.

Some of it was fear.

Mitchell’s gloved hands gripped the cold steel handles of the M51 quad mount like they were the only solid things left in the universe. His fingers ached where they curled around the grips. His boots were frozen. His breath came out in small, frantic clouds that glittered briefly before vanishing.

Somewhere in the black sky above, death was approaching at two hundred miles per hour.

At least, that was what his training told him to expect. If death came, it would come from above in the shape of a German fighter or a JU-88 bomber, its engines whining, its wings flashing as it rolled into an attack. The M51 multiple gun motor carriage—the quad 50—was built for that. Four .50 caliber Browning M2 machine guns, ganged together on a rotating platform, capable of vomiting out two thousand rounds a minute. A wall of lead so thick it could shred an aircraft from the sky.

It was not, under any circumstances, designed to point at the ground.

He knew that. They’d drilled it into him at Fort Bliss, Texas. Anti-aircraft doctrine was clear: you watched the sky, you listened for engines, you got permission from your gun commander before firing, and you did not waste precious ammunition on ground targets. Doing so was misuse of equipment. Doing so would get you chewed out, written up, maybe even court-martialed.

But James Mitchell was nineteen, had been trained on this gun for exactly six days, and this was his first night on actual guard duty.

And in about ninety seconds, he was going to make a mistake so catastrophic, so completely wrong, that it would accidentally save over two thousand American lives and change the outcome of one of the most critical battles of the Second World War.

He didn’t know any of that yet.

All he knew was that he was cold, tired, and very afraid of screwing up.

He hadn’t joined the Army because of heroism. If he was honest with himself, he’d joined to get away.

Lincoln, Nebraska, had a way of closing in on a person when the farm started to fail.

The Mitchell place had never been prosperous, not really. It had been barely enough in the good years and not enough in the bad ones. His father had fought the Dust Bowl, the Depression, bank notices, and rust. The war had brought higher crop prices, but not enough rain.

By 1944, the soil was thin and so was his father’s patience.

James was the youngest of four boys. The other three were already overseas, scattered across the world in different shades of khaki and olive drab. Their pictures hung on the wall in the front room, all in uniform, all trying to look older than they were.

James grew up in the marshlands near Lincoln, where the Platte River spread out in broad, muddy fingers and ducks and geese set down by the thousands. His father had taught him to hunt there, standing knee-deep in cold water behind reeds, shotgun cradled low, listening to the wind.

“You don’t shoot where they are,” his father would say, eyes tracking the distant flicker of wings. “You shoot where they’re going to be. You lead ’em. You pay attention to the wind. You pay attention to how fast they’re flying. You don’t rush it. You don’t flinch.”

Those mornings taught him more about moving targets than any manual ever would. He learned how to judge distance by sound, how to feel the way a bird cut across the sky, how to anticipate movement in three dimensions. It lived in his muscles, not his brain.

When he enlisted on his nineteenth birthday—September 3rd, 1944—it wasn’t because he’d suddenly been seized by patriotism. He loved his country, sure, but what pushed him down to the recruiting office was the way his father had stood in the doorway a week earlier, shoulders slumped, saying quietly, “There’s only enough left to keep this place going for one of us.”

His brothers had gone. It was his turn.

He signed the papers, wrote his name in shaky block letters, and the Army took one look at his scores and his hunting background and decided he’d be perfect for anti-aircraft artillery.

He arrived at Fort Bliss, outside El Paso, in late September. The air there was hot and dry, a blast furnace compared to the damp chill of Nebraska. Sandstorms instead of thunderstorms. Cactus instead of cottonwoods.

The training program was supposed to be seventeen weeks. War had shortened it to eight.

Technical Sergeant Robert Hansen—their primary instructor—stood in front of the new class on day one. He was in his thirties, deeply tanned, with the permanent squint of someone who’d spent too much time looking into bright desert skies.

“The life expectancy of an anti-aircraft crew under sustained air attack,” Hansen barked, “is approximately forty-five minutes.”

The recruits shifted uneasily.

“That’s not forty-five minutes of war. That’s forty-five minutes after the enemy starts targeting your position specifically. Soon as they decide they don’t like you, you got three-quarters of an hour on average before you’re dead.”

He let that sink in.

“Your job is to shoot down anything with a swastika on it before it shoots you. You fire until your barrels melt, ’til you run out of ammunition, or ’til you’re dead. Simple as that.”

James swallowed.

Weeks blurred together. Week one: they tore down and reassembled guns until their hands were raw, learned every pin and spring and feed tray of the M51 quad mount, the 40mm Bofors, the 90mm AA gun. Week two was aircraft recognition—grainy slides of silhouettes on a screen in a dark classroom. “ME-109, short nose, rounded wingtips. Focke-Wulf 190, squared wingtips, radial engine. You got three seconds to tell the difference before you shoot the wrong thing.”

Week three: tracking drills. They sat behind mock sights and swung guns at plywood planes on rails, trying to keep the front sight just ahead of the moving targets. Then came live fire.

The first time James squeezed an AA trigger and felt the recoil slam into his shoulders, his brain tried to file it under “shotgun,” then immediately backed out of that folder. A shotgun was a shove. A quad 50 was a continuous punch.

He loved it and feared it in equal measure.

What he didn’t have to learn was how to lead.

Other recruits struggled, firing where the target had been instead of where it was going. James’s hands seemed to know what to do before he did. He could look at a moving target, feel its speed, and swing the gun just so, the way he had with ducks over the marsh. It just made sense.

By week six, Hansen had him on the range as an example. “Mitchell here,” he’d say, clapping a hand on James’s shoulder. “From Nebraska. Shoots birds. Watch how he leads. Watch his hands. You can’t teach that part easy, but you can learn from watching.”

Instructors wrote notes in his file. “Exceptional target acquisition speed.” “Natural feel for lead.” “Recommend assignment to veteran crew.”

On November 12th, he graduated and got orders: Camp Kilmer, New Jersey. Overseas shipment. No time to waste. The war was chewing up anti-aircraft crews faster than Fort Bliss could spit them out, and now that the Allied armies were deep in Europe, the sky was target-rich and dangerous.

They gave him forty-eight hours’ leave before he shipped out.

He spent most of it in his childhood bed, staring at the ceiling in the half-dark, hearing his mother moving in the kitchen, his father’s slower steps outside. His brothers’ photos watched him from the wall. He felt like a kid and a stranger at the same time.

His mother knitted him a pair of wool gloves. “They won’t fit under those fancy Army ones,” she said, trying to joke. “But maybe you can wear them on top.”

His father shook his hand at the bus stop. The grip was firm, knuckles rough from years of work.

“Come home,” his father said. That was all. But his eyes were wet.

The USS Monticello rode hard through the North Atlantic, its gray hull punching through winter waves. Nine days of steel, sickness, and the constant, whispered threat of submarines.

James spent most of it learning just how thoroughly the sea could humiliate a man. The deck rolled under him in great, slow arcs. The ocean was always moving, even when the sky was deceptively calm, and his stomach never got the memo.

When he stumbled up onto the cold deck at night, leaning on the rail and sucking in freezing air, he tried to picture the European coastline waiting for him. England with its blacked-out cities. France with its wrecked ports. Somewhere inland, a front line that zig-zagged across forests and villages.

He’d trained to shoot down planes. That part seemed almost manageable. You had a target, you had a weapon, you did the math with your hands. What he didn’t know how to handle was the vast, confusing overlay of everything else.

He wanted, desperately, not to embarrass himself. Not to be the kid who panicked. Not to be the reason other men died.

Southampton in late November was wet and gray. The sky and the sea were the same color: dull, tired slate. Dockworkers shouted. Trucks backfired. Rows of men in uniform shuffled along muddy roads toward holding camps.

The replacement depot at Tidworth Barracks was a slow-motion purgatory. For two weeks, James drilled, cleaned equipment, shuffled paper, and waited. In the mess tent, rumors flew thicker than cigarette smoke.

“Big German offensive coming,” one man said, every day.

“Hell they are,” another replied. “Krauts are done. They’re on their last legs.”

Then December came, and with it, the news.

The Germans had punched a hole in the Ardennes. Tanks, infantry, paratroopers—everything they had left—slamming into thin American lines in the snow. A bulge on the map pushing west.

By the time orders came on December 14th assigning him to the 796th Anti-aircraft Artillery Battalion, Battery B, the Battle of the Bulge was already in full swing.

He crossed the Channel on December 16th under low clouds, the water slate-colored and ugly. The landing at Le Havre was chaos—trucks stuck in mud, shell-damaged buildings leaning like drunks, officers shouting over engines.

The road to Bastogne was worse.

They loaded him and a dozen other replacements onto the back of a deuce-and-a-half and drove east through a landscape that looked like a kicked anthill. Vehicles jammed every road. Jeeps, half-tracks, ambulances, tanks. Some were moving. Some were abandoned where they’d broken down or run out of gas. Old French farmhouses had new holes in their walls.

Sometimes they had to pull over as columns of exhausted infantrymen trudged past in the opposite direction, bandaged, dirty, eyes hollow. Retreating.

“Where you headed?” one of them called up to the truck.

“Bastogne,” someone yelled back.

The infantryman laughed, short and bitter. “Hell of a time to take a vacation.”

On December 19th, as the German encirclement closed around the town, James rolled into the 796th Battalion’s assembly area—mud, snow, trucks, and guns laid out in a rough ring around Bastogne’s battered buildings.

Battery B’s four M51 quad mounts were positioned along the perimeter, angled toward the sky. Their guns looked like something out of a Buck Rogers comic: four long barrels wedded together, all menace.

Gun Three—his gun, he’d soon call it—was commanded by Sergeant First Class William Barnes, a thirty-two-year-old Detroiter with a lined face and a voice that sounded like it had been sanded with gravel.

Barnes had been with the battalion since North Africa. He’d watched German fighters and bombers over Tunisian desert, Sicilian hills, French hedgerows. He’d lost crews. He’d lost friends. He’d lost any inclination to sugarcoat.

“You’re the second assistant gunner I’ve had this week,” he told James when they were introduced. “First one got hit by artillery two days ago.”

He took in James’s fresh uniform, his too-thin jacket, the way he kept glancing at the guns with a mix of awe and fear.

“I’m not gonna lie to you, kid,” Barnes said. “This is bad. We’re surrounded. They’re throwing everything at us. You do your job, you stay alert, you might make it out of here.”

The primary gunner was Corporal David Walsh, twenty-three, a Boston kid with a perpetual gum chew and a crooked grin. The loader was Private First Class Raymond Torres, twenty-one, from San Antonio, quiet, dark-eyed, efficient.

“You ever shoot one of these for real?” Walsh asked him.

“Just training,” James said.

Walsh chuckled. “You’ll love it. ’Til you don’t.”

Bastogne in December was as close to hell as any of them wanted to get.

The siege settled in like the cold. Artillery fell every day. Some days it was a constant distant thumping, like a giant with a hangover stumbling around just out of sight. Other days it was close: sudden shrieks, impacts that threw earth and snow into the air, the crack and roar and then the screaming afterward.

They were short on everything—food, ammo, medical supplies, sleep. They were never short on fear.

Battery B’s quad 50s spent the first few days of the siege doing exactly what they’d been built to do: they watched the sky and they fired.

German fighters harassed American positions whenever the weather broke. They dove at supply drops, tried to pick off trucks, made nuisance passes just to remind everyone they were still there.

James sat in the assistant gunner’s position, feeding belt after belt of linked .50 caliber rounds into the hungry guns as they tracked enemy aircraft. The first time he saw an ME-109 arrow in toward the town, silver belly flashing, he felt his chest cinch.

Walsh grinned around his chewing gum. “Get ready, Nebraska!”

Barnes peered through binoculars. “Range three thousand, angle twenty, lead two lengths,” he shouted.

Walsh swung the guns, the quad 50s elevating smoothly. “On him!”

“Fire!”

James stomped the foot pedal.

The guns roared.

Red tracers, one in every five rounds, climbed the sky in a staggering, weaving pattern. They reached up toward the German fighter like furious fireflies. The ME-109 jinked, rolled, tried to claw away.

Then a thin trail of smoke appeared from its tail.

“Did we hit him?” James yelled over the gun noise.

Barnes squinted through the binoculars as the fighter dipped, rolled again, then went into an ugly spiral.

“That’s a kill,” he said flatly. “Keep feeding those belts.”

The ME-109 hit the ground two miles outside Bastogne, a faint, distant puff of fire in the gray sky.

A strange cocktail of feelings flooded James’s veins: elation, nausea, relief, horror. The practical part of his brain said, Good. One less plane trying to kill us. Another part whispered, You just killed someone. There was a man in that plane.

The contradiction sat in his gut like a stone for days.

On December 23rd, when the weather finally cleared enough for a massive resupply operation, the quad 50s howled almost nonstop. C-47s droned overhead, their bellies opening to dump parachutes of ammunition, food, and medical supplies. German fighters streaked in to try to knock them down.

Battery B turned the sky into a lattice of red lines. Men cheered when parachutes opened. They cursed when supplies drifted into German lines. They shouted themselves hoarse when they saw a German fighter explode into flame.

It was war reduced to its most elemental: protect the lifeline, kill the ones trying to cut it.

By early January, Patton’s Third Army had punched a corridor through to Bastogne. The siege was technically broken. The town was still, however, very much in the line of fire.

The Germans weren’t ready to give up the Bulge. Counterattacks clawed at American positions. Infantry probed. Armor thrust forward. The lines bent and flexed. They held.

Battery B stayed put, covering the perimeter as Bastogne shifted from surrounded to contested.

On January 15th, Corporal Walsh went down.

Frostbite, both feet. Bad enough that the medics shook their heads and wrote evacuation tags. He tried to joke as they loaded him up.

“You boys’ll miss me,” he said. “Nobody else can make that gun sing like I do.”

Barnes watched the jeep disappear into the snowy trees and muttered, “Don’t die, you Boston bastard.”

Then he turned to the remaining crew—Torres, Mitchell—and made a decision.

“Mitchell,” he said. “You’re primary gunner now.”

For a second, James thought he’d misheard. “Sergeant?”

“You heard me,” Barnes said. “You’ve got the best eyes in the battery. Torres, you’re assistant. We’ll get a replacement loader from the depot, assuming some idiot at headquarters remembers we exist.”

James’s heart kicked against his ribs. He felt like somebody had opened a door under his feet.

He’d been comfortable in the assistant’s chair, feeding ammo, watching Walsh work the grips. Now the gun was his.

He spent January 16th climbing all over Gun Three, learning it from the new angle. The hand grips felt different from this spot—heavier, somehow. The traverse and elevation controls were just as simple as they’d been in training, but now they seemed imbued with weight.

The sight was a simple ring-and-post, nothing fancy. It demanded everything from the gunner: judgment, reflex, an instinct for speed and distance. No computers. No radar. Just eyes and hands and nerve.

The replacement loader showed up that afternoon.

Private Eugene Patterson was eighteen and looked younger, a narrow-shouldered kid from rural Georgia whose helmet kept sliding down over his eyebrows. His boots were too big. His gloves were too thin.

“Ever worked a quad?” Barnes asked him.

“Yessir,” Patterson said. “Three weeks training back in the States. I…uh…haven’t shot at anything that shot back yet.”

Barnes snorted. “Welcome to Bastogne,” he said. “You’ll get your chance.”

He looked at his crew—nineteen-year-old gunner, twenty-one-year-old assistant, eighteen-year-old loader—all with that same raw edge around their eyes.

“We’re scraping the bottom of the barrel,” he said that evening, standing with them in the fading light. “You boys are good, but you’re green. So here’s how we survive. You follow my orders exactly. You stay alert. You don’t panic. And you remember that this gun is the difference between our guys living and dying. Understood?”

“Yessir,” they chorused.

They understood, or thought they did.

None of them, including Barnes, had any idea what was going to happen in less than twelve hours.

The evening of January 16th felt almost calm by Bastogne standards.

No major air raids. No heavy armor probing the lines. Artillery came in sporadic, random shells rather than sustained barrages. The snow crunched underfoot. Breath hung in the air in small, smoky ghosts.

Barnes set the guard rotation with the precision of a man who’d seen what happened when you got sloppy. Of the three gunners on Gun Three, Mitchell drew the 0200 to 0400 shift.

“The dead zone,” Torres called it. “Most boring, most dangerous part of the night.”

“Stay awake,” Barnes told him, jabbing a finger at his chest. “I swear to God, if I wake up and find you snoring in my gun—”

“You won’t, Sergeant,” Mitchell said.

At 0145, Torres shook his shoulder in the dugout next to the gun.

“Your turn,” Torres said. “Nothing happening. Quiet night. Stay awake. Barnes’ll have your ass if you fall asleep.”

James crawled out of the dugout and into the teeth of the cold.

The sky was clear, stars sharp and indifferent. The trees at the forest edge were black cutouts. The snow reflected just enough starlight to turn the world into a grainy silver photograph.

He climbed into the gunner’s seat, settled his hands on the grips, and tried to will himself alert.

Doctrine rattled around in his head like loose rounds in an ammo can. Watch the sky. Listen for aircraft engines. At the first sign, wake the crew. Get Barnes. Don’t fire until ordered. Don’t, under any circumstances, waste ammunition on ground targets.

He’d been trained on this gun for six days. He knew the rules, knew the reasons behind them. Anti-aircraft ammunition was heavy, hard to resupply. The M51 was a strategic asset. You didn’t swing it around like some oversized machine gun to rake the ground.

But doctrine didn’t say anything about the crushing boredom.

The first hour passed in glacial stretches. His eyes scoured the sky, but there was nothing up there except distant stars and mockingly peaceful silence. No engines. No shadows. Just the creak of trees and the occasional crack of freezing timber.

His body wanted to sleep. His brain kept trying to drift. Each time, he jerked himself back with a start, fingers tightening on the grips.

At 0315, he heard something.

Not engines. Not the long roar of artillery. Not the distant thud of tanks.

Something smaller. Softer. Metal on metal, maybe. Cloth brushing against something. A scuff of boots.

He held his breath.

There it was again. Faint, but unmistakable. The muffled clink of equipment. The sound of…movement.

His training said aircraft. His ears, honed by Nebraska marshes, said game in the woods.

He leaned forward, eyes straining toward the dark line of trees. The forest was a black wall. He could see maybe twenty, thirty yards into it, and that only barely.

Could be his imagination. He was exhausted. Cold. It would be easy to hear things that weren’t there.

Standard procedure: wake Barnes. Report possible contact. Request permission to fire illuminating flares.

He hesitated.

Barnes had been clear about not panicking, not raising false alarms. Men needed sleep. The last thing he wanted to do was yank everyone out of their blankets because he’d let the wind spook him.

The sound came again. Closer this time. More of them. Multiple…somethings moving.

The hairs on the back of his neck stood up.

In the duck blind back home, there had been mornings when the marsh was perfectly still and then, without knowing how he knew, he’d felt birds approaching before he heard them. The air changed. The silence changed.

That was what this felt like.

Predators, his instincts said. Coming in careful. Staying low. Closing.

At 0320, he saw movement.

Not in the sky.

On the ground.

At the tree line, three hundred yards out, something shifted against the snow. A darker shadow within the dark. Then another. And another. Low shapes, hunched, moving with purpose. Too many to be a stray patrol, too coordinated to be random.

They were heading straight toward American lines.

His heart jumped.

Could be Americans, his training whispered. A returning patrol. A supply party. Men caught outside the wire after dark.

But American patrols didn’t move like that. At least, not the ones he’d seen. These shapes were spread out just so. They kept low like they’d done this a thousand times. They moved like hunters.

Standard operating procedure was a checklist: wake Barnes, report sighting, get confirmation, then—maybe—engage.

He watched the shapes cross the first open stretch of snow.

They were fast. They were committed. In seconds, they’d be past the point where a flare would do any good. Once they were inside the perimeter, lines would blur. The quad 50 became useless in close fighting. Chaos would reign.

He didn’t have seconds, not the way the book defined them. Doctrine lived in an orderly universe. This didn’t.

His hands were already moving.

He swung the traverse handles, bringing the barrels down. The quad groaned softly as it tilted, the sight ring dropping from the sky to the horizon, then lower. He found the dark mass of moving shapes and centered the ring over them.

He could feel his pulse in his throat, in his ears, in his fingers.

This is wrong, he thought. This is absolutely, completely wrong.

He pressed the firing pedal.

Four .50 caliber Browning machine guns screamed to life as one.

The quad 50’s roar was less a sound and more a physical force. It hammered his chest, his teeth, the bones of his skull. Muzzle flashes lit the night like strobe lights, turning the world into a series of frozen images: trees, snow, dark figures, then nothing, then again.

Tracers ripped across the snow at nearly three thousand feet per second, red lines skimming just above the frozen ground. They reached the tree line in a fraction of a breath.

The shapes he’d been aiming at—the ones his hunting instincts had tagged as predators—were German infantry from the 2nd SS Panzer Division’s reconnaissance battalion. Over two hundred of them in that first wave alone, moving in absolute silence, black uniforms blending with the night, white smocks blending with the snow.

They had slipped past sentries. They had mapped listening posts. They’d been moving under cover of darkness with chilling efficiency, preparing to slip through gaps in the American line.

They were not prepared for this.

.50 caliber rounds are designed to chew through aircraft skin and engine blocks. Against flesh, they are obscene. Each bullet carries over eighteen hundred foot-pounds of energy. At three hundred yards, they still hit with bone-breaking force.

The first burst caught the Germans completely in the open.

Men went down like scythed wheat. Some simply dropped, strings cut. Others were hit mid-stride and thrown sideways as if yanked by unseen ropes. Snow leapt up in red fountains. Bodies spun, jerked, slammed into each other.

The assault force snapped from stealth to chaos in an instant. Shouts erupted in German. Some men tried to dive for cover. There was none. The ground between the forest edge and the American line was a treeless, shell-pocked field of white.

Mitchell held the pedal down.

He tracked the gun like he would have tracked a flock of geese—sweeping through the densest part, leading just enough, not overcorrecting. Fifteen seconds of sustained fire. Fifty rounds per second, two thousand rounds per minute, chewing a horizontal stripe of death across three hundred yards of snow.

He smelled cordite and hot metal, the biting reek of burnt powder mixing with the clean cold air. He barely heard his own voice over the roar as he blurted, “Oh God. Oh God, what did I do?”

The guns stopped when he let off the pedal. The sudden silence was shocking, a vacuum that rang in his ears.

“Mitchell! What the hell are you shooting at?”

Barnes exploded out of the dugout, Torres and Patterson on his heels, all of them half-awake, faces wild.

“We under air attack?” Torres shouted, looking up into the sky.

Mitchell was shaking so hard he could barely point. “Down there,” he gasped. “Ground. I saw…they were…they were coming at us.”

Barnes swore and snatched up his binoculars. He lifted them to his eyes and peered into the darkness where the tracers had gone.

From their position, three hundred yards away, it was hard to see detail. But the silhouette of the field had changed. Mounds where there had been flat snow. Dark spots. Movement that was wrong—not organized advances, but random twitching.

Barnes’s swearing stopped.

His expression shifted in three beats: fury at the unauthorized firing, shock at what he was seeing, and then something like awe.

“Holy mother of God,” he breathed.

“What is it?” Torres demanded.

“Get on the radio,” Barnes snapped without looking away. “Now. Tell battalion we’ve got enemy infantry—battalion strength at least—attempting to infiltrate. Mitchell just stopped a goddamn night assault.”

Torres lunged for the field telephone, fingers fumbling as he dialed.

“Red Three to Red One,” he shouted into the handset. “This is Gun Three. Ground contact. I say again, ground contact. Heavy Kraut infantry at our front. We engaged. We need flares and immediate alert along the line.”

Within minutes, the entire sector woke up.

Flares hissed into the sky, arcing upward before bursting into harsh white light. Shackled to parachutes, they drifted down slowly, bathing the snow in a cold, theatrical glow.

The field in front of them was a butcher’s yard.

Where there had been a smooth blanket of snow, there were now dozens and dozens of sprawled shapes. Men in gray and white, limbs twisted at impossible angles, dark stains spreading underneath them. Some tried to crawl. Some didn’t move at all.

They counted later. There were over eighty German dead and dying in that first swath alone.

The survivors had retreated back into the tree line, dragging wounded men, scrambling for any scrap of cover.

The infiltration was blown.

What none of the Americans on the line realized—what no one in that cold gun pit could have known at that moment—was that this reconnaissance force had been the lead edge of something much larger.

The planned German night assault had been a masterpiece of brutal efficiency on paper. SS-Sturmbannführer Klaus Hoffman’s reconnaissance battalion had spent five days watching American positions, mapping sentry routes, listening posts, weak points. They’d observed exhausted GIs nodding over their rifles in the small hours. They’d noted which sectors of the perimeter seemed least active.

The plan was simple and devastating: his infiltrators would slip inside the American lines under cover of darkness. Once in, they’d sow confusion, cut communication wires, hit command posts, create the illusion of chaos. At 0330, a main assault force of over fifteen hundred infantrymen, supported by armor, would attack through the now-breached sector against defenders who were half-awake and disorganized.

Everything depended on surprise.

Mitchell’s fifteen-second violation of doctrine took surprise, shredded it with .50 caliber fire, and tossed it into the snow.

When no signal came from Hoffman’s infiltrators and, instead, American positions suddenly lit the night with flares and shouted orders, German commanders realized their element of surprise had died with the eighty men caught in Gun Three’s opening burst.

The main assault was called off.

Two American battalions—the 501st Parachute Infantry and elements of the 327th Glider Infantry—never knew just how close they’d come to being hit in their sleep.

The immediate aftermath was a whirlwind of noise and questions.

For the rest of that night, the line stayed on hair-trigger. Every rustle in the woods brought guns up. Every flare turned shadows into possible enemies. No one slept.

At dawn, officers descended on Gun Three.

Battalion wanted to know how a nineteen-year-old kid on his first full night as primary gunner had detected an infiltration that sentries, listening posts, and forward observers had all missed. Division intelligence wanted to know what he’d heard, what he’d seen, in excruciating detail. The regimental commander wanted to look him in the eye and gauge whether he was a reckless idiot or something else.

Mitchell stood in front of them, eyes bloodshot, hands still trembling, and tried to explain something that he himself didn’t fully understand.

“I grew up hunting,” he said. “In the woods. In the marsh. You learn to hear things that don’t belong. Ducks coming in. A deer stepping wrong. This…” He gestured toward the forest. “I heard equipment. I saw shapes. I just…reacted. I didn’t think. I just did what felt right.”

“You violated every rule of anti-aircraft employment,” Colonel Marcus Hayes, the battalion commander, told him the next morning.

Hayes was a tall man with tired eyes and a uniform that looked like it had been slept in for a week. He sat behind a makeshift desk in a room that used to be somebody’s parlor, maps tacked to the walls, a damp smell seeping from cracked plaster.

“You fired a strategic air defense weapon at ground targets without authorization,” Hayes continued. “You wasted ammunition. You compromised our anti-air posture. Do you understand that?”

“Yes, sir,” Mitchell said quietly.

Hayes stared at him for a long moment, fingers steepled.

“You also detected an infiltration nobody else saw,” he went on. “You reacted faster than trained sentries. You disrupted a major German assault. You saved at least two thousand American lives.”

He exhaled.

“So here’s what’s going to happen,” Hayes said. “Officially, this never happened. We do not need higher headquarters asking questions about why an anti-aircraft gun was chewing up ground targets. Officially, alert sentries detected the infiltration and called for fire support. Unofficially…”

Hayes’s mouth twitched in something almost like a smile.

“Unofficially, you just did something remarkable. Understood?”

“Yes, sir,” Mitchell said.

The colonel nodded. “Good. Now get some sleep before you fall over in my office.”

The story spread anyway, as such stories always do.

By January 18th, every AA crew in the 101st Airborne’s sector had heard about the gunner who’d pointed a quad 50 at the ground and stopped an SS assault cold. By January 20th, they were telling the story in Third Army mess tents, adding embellishments as it went. By the end of the month, instructors back at Fort Bliss were referencing “a certain incident in Belgium” in hushed tones as an example of initiative.

It would be months before the full extent of what had been prevented came to light.

SS-Sturmbannführer Klaus Hoffman, the German reconnaissance battalion commander, survived the war just long enough to be captured three weeks after Bastogne. In a drafty interrogation room, wrapped in a blanket over his SS uniform, he told his side to American intelligence officers.

“We had infiltrated successfully,” he said, according to transcripts. His English was rough; an interpreter smoothed the words.

“Your sentries were asleep or inattentive. We were inside your perimeter, preparing to signal the main assault. Then suddenly one of your anti-aircraft weapons engaged us at ground level.”

He shook his head, the memory still raw.

“The fire was devastating. We lost over eighty men in the first burst. The attack was compromised completely.”

They asked him about his reconnaissance.

“For five days,” Hoffman said. “We observed your positions. We mapped sentry posts, patrol routes. We determined that your forces were exhausted, that you maintained minimal night security. The plan depended on surprise. Once inside, we would create chaos while the main assault overwhelmed your defenders.”

He looked up at the Americans.

“Your anti-aircraft gunner destroyed that plan,” he said. “We had accounted for sentries, for patrols, for listening posts. We never considered that someone would be watching the ground with an anti-aircraft weapon. It was unexpected. Impossible to plan for.”

The war rolled on.

The 796th Battalion stayed in Belgium through February, pushing east with the rest of the Allied forces as the Bulge was hammered flat and the front line marched toward the Rhine. Battery B’s quad 50s went back to their core job: raking the sky whenever a cross emerged in it.

Mitchell and his crew engaged German aircraft on multiple occasions, scoring two confirmed kills and three probable. Each time, he slid into the rhythm of tracking, leading, firing, the way he’d done on the marsh. Each time, he felt the old knot of nausea when a plane went down, knowing there was a man inside.

None of those engagements would ever loom as large as the fifteen seconds on January 17th.

On February 23rd, orders caught up with him.

He was being rotated stateside. Instructor duty at Fort Bliss.

“You’re famous,” Torres told him, grinning, as they read the orders.

Barnes pulled him aside that night.

They stood next to Gun Three. The snow was thinner now. Mud poked through in ugly patches. The barrels of the quad were blackened from months of firing.

“You know what you did, right?” Barnes asked.

“What everyone says I did,” James said.

“Kid, you saved lives,” Barnes said. “Maybe mine. Definitely a lot of other guys’. You did good.”

“I got lucky, Sergeant,” James replied. “I did everything wrong and it…happened to work out.”

Barnes shook his head. “No. You did everything different and it worked out. There’s a difference.”

He pointed at the gun.

“Sometimes doing things by the book gets people killed,” he said. “Sometimes the book ain’t caught up with reality yet. Sometimes you need someone who doesn’t know the book well enough to be chained to it.”

James didn’t know what to say.

“Just don’t let some colonel use you as an excuse to get kids killed,” Barnes added gruffly. “Teach ’em to think. Not just to follow.”

“I’ll try,” Mitchell said.

Fort Bliss in March felt like a different planet.

The sun was hot again. The sand was back. The sky was an endless blue instead of a low gray lid.

James walked into the same classroom where, six months earlier, he’d listened to Sergeant Hansen talk about forty-five-minute life expectancies. Hansen was gone—sent back overseas or rotated out. New instructors stood where he’d stood, younger, some with fresh combat ribbons.

They made room for Mitchell at the front of the class.

He taught the same eight-week program he’d gone through, but with addenda.

He showed them how to track fast-moving targets, how to lead properly, how to trust the subtle twitch in their hands when their eyes said one thing and their instincts said another. He talked about aircraft silhouettes. He talked about malfunction drills.

He also talked—quietly, off the official syllabus—about the ground.

“Look,” he’d tell his students, chalk in hand, drawing circles on the board. “They tell you your job is the sky. That’s true. That’s priority. But you’re not blind. You’re not bolted to the clouds. You’ve got a gun that can throw lead like nothing else, and you’ve got eyes. Use both.”

He never mentioned Bastogne by name. He never said, “Here’s what I did.” But he’d say, “If you hear something that doesn’t fit, you don’t ignore it just because it’s not in the manual.”

In March 1945, the Anti-Aircraft Artillery Command issued Field Circular 12-45, officially recognizing ground engagement as a legitimate use of anti-aircraft weapons under certain circumstances. The circular cited “lessons learned from the European theater, particularly Belgian operations.” It didn’t mention him.

By Korea, using AA guns against ground targets was normal. The quad 50’s successor, the M45, came with improved sights and lower elevation limits specifically to make it better at raking ground targets. In Vietnam, quad mounts became the backbone of convoy defense and firebase protection. The idea that these weapons were dual-purpose was baked into doctrine.

James seldom thought of himself as the hinge in that evolution.

He got out of the Army on November 3rd, 1945. Sergeant now. Bronze Star pinned on his uniform for “meritorious achievement in connection with military operations near Bastogne, Belgium.” The citation used careful phrases like “exceptional alertness” and “initiative” and did not, in any way, suggest that he’d violated orders.

He went home to Lincoln.

The farm looked smaller. The fields were the same, but he wasn’t.

He used the GI Bill to attend the University of Nebraska. Forestry appealed to him: trees, streams, firebreaks, soil conservation. There was something healing about planning how to care for land instead of how to fight over it.

He graduated in 1949, married a local girl named Dorothy Hansen in 1950, and moved into a small house with a porch that looked west over a flat horizon. He took a job with the Nebraska National Forest Service, driving a truck instead of a truck being blown up under him, walking through woods looking for beetle kill instead of infiltration.

They had kids. He taught them to hunt with the same care his father had given him. He showed them how to listen to the woods. He did not talk much about why.

His wife knew he’d been in an anti-aircraft battalion. His children knew he’d been at a place called Bastogne. They knew he had a Bronze Star in a box in the closet. They did not know the details.

It wasn’t shame exactly. It was more that he didn’t know how to explain something that, even fifty years later, still didn’t make complete sense to him.

How do you tell your grandson that the thing people call your moment of heroism felt, from the inside, like a frantic mistake?

In 1994, the world seemed very far removed from the winter of 1945.

James Mitchell was sixty-eight, retired, a grandfather. His hair had gone white. His hands still remembered the shape of the M51’s grips when he wrapped them around a snow shovel.

A reunion notice came in the mail.

The 796th Anti-Aircraft Artillery Battalion was gathering in Washington, D.C. Fifty years after the Battle of the Bulge. There would be speeches. Dinners. A visit to memorials. A chance to see old faces before there were no faces left to see.

He’d ignored such invitations before. The idea of being trotted out as “that guy” made him uncomfortable. But Dorothy put the letter on the kitchen table and gave him a look.

“You owe it to yourself,” she said. “Go. See them. Tell the story.”

So he did.

The reunion hotel ballroom was full of men who walked with canes and had ribbons on their lapels. Photos from the war were displayed on easels around the room: young, hard faces in helmets, guns in the background, guns in the foreground, guns filling the frame.

He found Barnes, older and grayer, still with the same gravel in his voice. Torres was there. Patterson. They hugged in that awkward way men of their generation did, thumping backs, eyes watery.

“Still remember how to pull a trigger, Nebraska?” Barnes asked.

“Only on a duck,” James said.

In a corner, a younger man in a sport coat and a college tie moved between groups, a notebook in his hand. He was a military historian, someone said, working on a book about anti-aircraft operations in the Battle of the Bulge.

He’d been trying to track down “the Bastogne incident” and had found conflicting accounts.

That evening, over hotel roast beef and mashed potatoes, the historian sat down with James.

“I’ve got the official reports,” he said, flipping open his notebook. “They talk about alert sentries, supporting fires, coordinated action. And then I’ve got these unofficial stories, and they’re all pointing at some nineteen-year-old kid on a quad 50.”

He looked at James. “I think that kid was you.”

James took a breath.

He’d told parts of the story before at reunions, in bits and pieces. He’d never unfolded the whole thing in one sitting.

So he did.

He talked about Nebraska marshes. About Fort Bliss. About Hansen’s forty-five-minute lecture. About Bastogne’s cold. About Walsh and Torres and Barnes. About that night—about the boredom, the sound in the trees, the shapes at the tree line, the churning panic in his chest.

“I didn’t think,” he said finally. “That’s the truth of it. They teach you to say you made a decision, like you weighed options. I didn’t. I just…did it. It felt wrong. The woods. I grew up in the woods. And it felt wrong. So I fired.”

The historian listened, sometimes asking for clarification, sometimes just nodding.

When James finished, he felt oddly drained, as if those fifteen seconds had finally caught up to him.

“Do you realize what you actually did?” the historian asked quietly.

“I shot where I wasn’t supposed to,” James said.

“You didn’t just stop one attack,” the historian said. “You nudged doctrine. Before Bastogne, anti-aircraft guns were thought of as single-purpose weapons. After Bastogne, people started to treat them like multi-role systems. That shift? That mentality? It probably saved thousands of lives in Korea and Vietnam.”

James frowned. “I was scared,” he said. “I heard something. I saw something. I did what seemed right in the moment. That’s all.”

“That’s always all it is,” the historian replied. “Nobody makes brilliant tactical decisions in combat. They make snap judgments with limited information and then hope the universe doesn’t kill them for it. The difference between disaster and success is usually just luck.”

He smiled, not unkindly.

“You were lucky,” he said. “But you were also alert, trained, and willing to act. That combination is what matters.”

The words didn’t magically make everything neat, but they shifted something.

For fifty years, James had carried a quiet sense that he was a fraud. The citation made him sound like a hero. He knew he’d felt like a kid with his finger jammed on the trigger and no idea what he was doing.

Maybe, he thought, that was what a lot of “heroism” actually looked like from the inside.

Maybe the bronze stars and sanitized histories smoothed out the ragged edges because people liked their stories to make sense. The real thing never did.

He started going to more reunions after that. He spoke at anti-aircraft veterans’ association meetings when they invited him, telling his story not as a legend but as an example of how messy combat decisions really were.

When the 796th’s official history was published in 1996, he bought a copy.

The chapter on January 17th described “alert anti-aircraft crews” detecting and engaging “a German infiltration attempt,” preventing “a potentially catastrophic night assault.” It mentioned him by name as part of a battery that “responded with effective fire.”

He read the section, smiled at its careful phrasing, and closed the book.

The official history had smoothed everything into cause and effect. It was what official histories did.

The real story was simpler.

A nineteen-year-old kid from Nebraska, trained for eight weeks to shoot at airplanes, sat alone in the freezing dark and heard something that bothered him. His hunting instincts told him that something was wrong on the ground. He swung a gun he wasn’t supposed to swing that way and fired at shapes he could barely see.

Everything that came afterward—the saved battalions, the field circulars, the doctrinal shifts—was accident and interpretation.

James Edward Mitchell died on March 12th, 2006, at the age of eighty.

His obituary in the Lincoln Journal Star mentioned that he had served in the 796th Anti-Aircraft Artillery Battalion and had been awarded the Bronze Star. It talked about his thirty years with the Nebraska National Forest Service, his love of hunting and fishing, his wife Dorothy, his children and grandchildren.

It didn’t talk about Bastogne.

It didn’t need to.

His kids knew the story now. His grandchildren had heard him tell it at Thanksgiving, sometimes when the conversation turned to war and they asked him what it was like. He’d always start by saying, “Mostly, it was cold,” and then, if they pressed, he’d describe the night when he had done everything wrong and somehow, impossibly, it had turned out right.

The M51 quad mount he had used that night was probably melted down decades ago. The steel that had once vibrated under his hands might be part of a bridge, or a car bumper, or the skeleton of a building somewhere.

What remained of that night was less tangible but more enduring.

Modern doctrine, in thick manuals, now says things like “weapons systems should be designed for multi-role employment” and “commanders will encourage initiative and adaptability among subordinates.” Young soldiers are taught that they might have to make decisions outside of written procedure. That sometimes the situation on the ground demands something the book doesn’t cover.

Those ideas didn’t start in a classroom. They started in foxholes and gun pits, in places like Bastogne, where somebody violated the rules and the universe, for once, rewarded it.

The memorial to the 796th Anti-Aircraft Artillery Battalion at Fort Bliss is a simple stone with a bronze plaque, surrounded by well-kept grass. It lists names in neat rows: men who served, men who died.

James E. Mitchell is one among many.

There’s no asterisk. No extra line that says “accidentally saved two battalions.” No explanation.

Maybe that’s fitting.

His story isn’t about a single man’s glory. It’s about the chaotic way war actually works.

Plans matter. Training matters. Doctrine matters.

So do scared nineteen-year-olds in the dark who are willing to trust their instincts.

On a freezing night in January 1945, manning his first anti-aircraft gun, James Mitchell did exactly what he wasn’t supposed to do.

He heard something. He saw something. He put his foot down on the pedal.

He was wrong according to every rule in the book.

And because he was willing to be wrong, two thousand men who never knew his name lived to see the dawn.

THE END

News

CH2 – The German Boy Who Hid a Shot-Down American Pilot from the SS for 6 Weeks…

The SS officer’s boot stopped six inches from the boy’s nose. Fran Weber stood in the barn doorway with his…

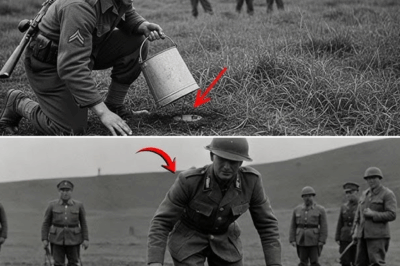

How One Private’s “Stupid” Bucket Trick Detected 40 German Mines — Without Setting One Off

The water off Omaha Beach ran red where it broke over the sandbars. Corporal James Mitchell felt it on his…

Germans Couldn’t Believe This “Invisible” Hunter — Until He Became Deadliest Night Ace

👻 The Mosquito Terror: How Two Men and a Radar Detector Broke the German Night Fighter Defense The Tactical Evolution…

How One General’s “IMPOSSIBLE” Promise Won the Battle of the Bulge

The Impossible Pivot: George S. Patton, the 72-Hour Miracle, and the Salvation of Bastogne I. The Storm of Despair in…

They Mocked His ‘Mail-Order’ Rifle — Until He Killed 11 Japanese Snipers in 4 Days

🎯 The Unconventional Weapon: How John George’s Civilian Rifle Broke the Guadalcanal Sniper Siege Second Lieutenant John George’s actions…

“They Tried to Erase Me from the Family Celebration—But My Military Power Left Them Speechless”..

“Didn’t you used to play waitress?” Aunt Kendra’s laugh cut through the air like broken glass. I froze in the…

End of content

No more pages to load