They called it a tank with wings.

Not to its face, not officially—not in front of the commander or the intelligence officer with the clipboard—but in the muddy space behind the revetments at Henderson Field, under camouflage netting that smelled like wet rope and gasoline, men said it anyway. Quietly. With that particular kind of humor pilots use when the alternative is admitting they’re scared.

“Hellcat?” one of the old Wildcat guys snorted, wiping coral dust off his hands. “More like Hell—what? You fly that thing long enough, you’ll be dead of old age before you finish a turn.”

Laughter moved through the line of men like a warm current, quick and sharp. It felt good to laugh at something when everything else in the Solomon Islands was made of rot, heat, and the distant, daily promise of fire.

The Pacific had a way of making every piece of metal feel temporary.

Out past the strip, the ocean sat flat and gray-blue under the haze. The jungle pressed in from all sides, a green wall that sweated and whispered. Henderson Field itself was a scar: crushed coral and dirt, carved from the island by bulldozers and stubbornness, shelled by Japanese destroyers on nights when the moon made the runway too easy to find.

The tents were muddy. The food was indifferent. The flight suits never really dried. The air always tasted like salt and fuel and something metallic—spent brass, maybe, or fear.

And parked in the dispersal area, where the sun hit the wings and turned the paint into a dull shine, sat the newest argument in the Navy: the Grumman F6F Hellcat.

Heavier than the Zero by more than two thousand pounds.

Slower in the climb.

Wider in the turn.

Stable in the way a freight train is stable.

It had six .50-caliber machine guns, armor behind the seat, self-sealing fuel tanks. It could take punishment the Zero couldn’t dream of surviving.

But none of that mattered if you couldn’t bring the nose onto a target before the Zero slid away like a knife through water.

That was the fear nobody joked about.

Firepower means nothing if you cannot line up the shot.

And every man on that airfield had heard the same gospel repeated until it felt like a prayer:

Don’t dogfight Zeros.

Don’t turn with them.

Boom and zoom.

Dive, shoot, climb away.

Never commit to a sustained turning fight.

It was good advice. It kept men alive. It also put the enemy in charge of the rules.

Lieutenant Commander Edward O’Hare listened to the jokes without joining them.

He stood slightly apart, as he often did, lean and quiet, face sunburned to a permanent bronze, expression unreadable. He was twenty-eight years old, and already carried the kind of reputation that made other men measure their voices around him.

A year earlier, he’d earned the Medal of Honor for single-handedly attacking nine Japanese bombers threatening the carrier Lexington. He’d shot down five, damaged three more, saved the ship.

But that had been in a Wildcat. That had been desperate. That had been a moment that made sense only because the alternative was watching the carrier die.

This—this was doctrine.

This was formation flying.

This was survival by the numbers.

The Hellcat didn’t inspire love. It inspired arguments. It inspired veterans to complain and rookies to stare at it like it was a test they hadn’t studied for.

O’Hare walked around his Hellcat, running a hand along the panel seams, checking rivets, inspecting the prop, testing surfaces. He moved like a man solving a problem, not like a man greeting an old friend.

Some pilots thought that meant he didn’t have nerves.

The men who’d flown beside him knew better.

O’Hare had nerves. He just didn’t waste them on theater.

When the squadron’s laughter faded into the sound of tools and engines, one of the younger pilots—fresh enough that his fear hadn’t yet hardened into jokes—leaned toward his buddy.

“Think he buys it?” the kid whispered, nodding at O’Hare.

“Buys what?”

“All this.” The kid’s eyes flicked to the Hellcat’s broad wings and thick fuselage. “That it can fight a Zero.”

His buddy shrugged. “He doesn’t buy things. He figures them out.”

And that was the difference.

To most men, the Hellcat was a verdict: too heavy, too slow, too forgiving to win a knife fight.

To O’Hare, it was a set of parameters.

A boundary you could work within.

A machine with rules, and therefore loopholes.

He climbed into the cockpit, strapped in, and started the engine.

The Pratt & Whitney R-2800 roared to life—eighteen cylinders of American engineering shaking the airframe like a controlled explosion. The sound wasn’t elegant. It was confident.

The air around the plane trembled. Mechanics stepped back. The prop wash kicked up coral dust and sent it swirling across boots and canvas.

O’Hare checked gauges. Oil pressure. Fuel. Ammunition feeds.

Then he looked up at the sky.

It was hazy. Thick. Wet.

The kind of sky where distance lies to you.

Ahead, somewhere beyond stacked clouds that looked like distant mountains, Rabaul waited.

A fortress carved into volcanic ridges and hidden under jungle canopy. The keystone of Japanese air power in the South Pacific. Hundreds of aircraft, thousands of troops, an air defense network that turned the air above it into a hornet’s nest.

To strike Rabaul was to fly into a place that wanted you dead and had the experience to make it happen.

The mission brief that morning had been simple.

Escort the bombers.

Keep the Zeros off their backs.

Get home alive.

O’Hare listened to the brief without expression. Weather report. Fuel calculations. Estimated enemy strength.

No jokes. No bravado.

Then he walked out to his Hellcat as if the mission had already happened and all that remained was execution.

The other pilots watched him.

Some with respect.

Some with doubt.

Because even if you respected the man, you could still question the machine.

And this war—this air war—was still a question mark written in aluminum and blood.

Japanese fighters owned the turning radius.

American planes owned the firepower.

The question was who got to write the rest of the sentence.

Edward Henry O’Hare had grown up far from coral strips and burning skies.

St. Louis, Missouri. March 1914.

His father was a lawyer with connections to organized crime. His mother was devout and disciplined, determined her son would grow up honest in a house full of contradictions—wealth and danger, ambition and faith.

Edward was quiet as a child. Not shy. Observant. He watched people. He listened more than he spoke. He liked puzzles and systems. He liked understanding how things worked and why they failed.

When he was a teenager, his father turned informant against Al Capone.

The family knew what that meant.

A week before the trial, his father was found shot to death in his car. The case was never solved.

Edward didn’t talk about it.

He carried it.

In 1933, he enrolled at the Naval Academy in Annapolis. His classmates remembered him as calm under pressure. Good with numbers. Excellent in navigation. Not flashy. Not a natural stick-and-rudder showman.

Steady.

Reliable.

The kind of pilot who thought three steps ahead.

He earned his wings in 1940. By the time Pearl Harbor was attacked, he was a seasoned carrier pilot with hundreds of hours in the cockpit. He understood fuel consumption. Deflection angles. That air combat wasn’t about courage.

It was about geometry and timing and knowing your aircraft better than the enemy knew his.

So when he transferred to the F6F program in late 1942, he didn’t complain about its weight or its reputation.

He studied it like an engineer.

He flew it in every configuration. Tested stall characteristics. Measured roll rate at different speeds. Learned where it bled energy and where it held it. Where the controls stiffened. Where the airplane wanted to do something stupid if you asked the wrong question.

Other pilots saw limitations.

O’Hare saw boundaries.

The Hellcat could not outturn a Zero in a slow-speed scissors. That was a fact.

But it could sustain a high-speed turn without losing energy.

It could reverse direction faster in a rolling maneuver.

It had better visibility, better radios, better gunsight tracking.

It was not more agile.

It was more controllable.

So O’Hare developed a theory the way he developed everything: quietly, methodically, through testing.

If you could force the Zero to fight at higher speeds, you could neutralize its turning advantage.

If you used vertical maneuvers instead of horizontal ones, you could leverage power and energy rather than pure radius.

If you kept speed above 250 knots, the Zero’s controls stiffened and its magic disappeared.

He tested this in mock fights—against captured Zeros when he could, against squadron mates when he couldn’t. He refined techniques. He didn’t write a manual. He didn’t brag.

He just flew and remembered.

By the time the formation headed toward Rabaul in February 1943, O’Hare had flown more hours in the Hellcat than almost anyone in the Navy.

He knew what it could do.

He knew what it could not.

And he knew the men mocking it hadn’t tested its edges.

The raid was a calculated risk.

Sixteen bombers. Eight fighters. Hundreds of miles over open ocean. No radar warning. No rescue if you went down.

Rabaul’s early warning network was meticulous. Coastwatchers hidden in jungle had already radioed sightings. By the time the American formation crossed the coast, the Zeros were airborne and climbing.

The bombers made their run. Bombs tumbled toward fuel dumps and revetments. Anti-aircraft fire filled the sky with black puffs that looked like dirty flowers blooming and dying instantly.

The air became a harsh, loud geometry problem.

Then the Zeros arrived.

They came in flights of three and four, slashing through the formation with brutal efficiency. American fighters broke to engage. Contrails tangled. Gunfire stitched air. The sky turned into a wheeling, screaming maze.

O’Hare’s eyes tracked motion the way a good mechanic tracks vibrations—reading patterns before they become disasters.

He saw a flight of six Zeros climbing toward a straggling bomber.

The bomber’s tail gun was silent. It was smoking. It was alone.

The Zeros were seconds away from tearing it apart.

There was no time to call for backup. No time to negotiate.

O’Hare shoved the throttle forward and dove.

The Hellcat accelerated like a falling anvil.

Air speed climbed past 300 knots. The controls grew heavy but precise—less like a feather and more like a tool with weight, something you could lean into and trust.

He lined up on the trailing Zero and opened fire.

Six guns converged.

The Zero disintegrated in a spray of metal and fuel.

One moment it was an aircraft. The next it was fragments spinning into the tropical haze.

The other five broke hard, scattering like birds.

Then they regrouped.

And they turned toward him.

Five to one.

Exactly what doctrine said never to do.

O’Hare didn’t run.

He pulled the Hellcat into a steep climbing turn.

The Zeros followed.

They were lighter. They should have closed the gap. They should have been inside his turn like knives finding soft places.

But O’Hare held speed. Tight but fast. Not trying to turn tighter than a Zero. Turning faster—using power and energy like a lever.

The big engine howled. The airframe shuddered but held. He could feel the airplane’s protest, but he could also feel its willingness. It wasn’t a dancer. It was a brawler who knew how to take a punch.

The Zeros tried to cut inside.

O’Hare reversed.

He rolled inverted and pulled through, converting altitude into airspeed, then snapped back into a climbing spiral.

The Zeros followed, but now something subtle changed.

They had bled speed in the initial turn. They were trying to dogfight at 200 knots.

O’Hare’s Hellcat stayed above 250.

At that speed, the Hellcat wasn’t a freight train. It was a blade with weight behind it.

He came around again and fired a burst.

A second Zero spun away, trailing smoke.

The others tightened their circle.

Experienced pilots, these. They understood angles and timing too. They weren’t panicking. They were hunting.

But they were hunting a plane that refused to behave as expected.

The Hellcat should have been bleeding energy. It should have been a sitting target.

Instead it was turning with a kind of disciplined violence—fast arcs, sharp reversals, a refusal to slow down.

Another Zero pulled lead and fired. Tracers arced past O’Hare’s canopy, close enough to look like glowing beads thrown by a careless hand.

O’Hare pulled harder, felt the G-force press him into his seat. He kept the turn going.

The Zero overshot—slid past the Hellcat’s nose by just enough.

O’Hare reversed again.

He fired.

The Zero’s wing crumpled. It broke away and fell, the aircraft suddenly wrong, tumbling like a wounded animal.

Three down.

Three still hunting.

Now the air felt crowded.

Other American fighters were arriving, drawn by radio calls and the visible chaos. The Zeros saw the odds shifting, saw the fight turning from a clean five-to-one to something uncertain.

They broke off and dove toward cloud cover.

O’Hare didn’t chase.

He rejoined the smoking bomber and escorted it home.

That, more than the kills, was the point.

He hadn’t fought because he wanted a scoreboard.

He’d fought because the bomber was dying and someone had to make the math change.

His wingman arrived minutes later, breathless over the radio, voice pitched high with disbelief.

He’d seen the whole thing.

Six Zeros. Four kills. No hits taken. In a Hellcat. In a turning fight.

At Henderson Field, when the planes rolled back in and the engines ticked as they cooled, the debrief was quiet in the way that follows something nobody can easily file into “normal.”

The intelligence officer asked O’Hare to describe his maneuvers.

O’Hare shrugged.

He said he kept his speed up.

He said he used the engine.

He said the Hellcat turned fine if you didn’t let it slow down.

The other pilots exchanged glances.

Some skeptical.

Some beginning to feel that maybe the problem wasn’t the aircraft.

Maybe it was the doctrine.

For months, American fighter tactics had been built around one assumption:

The Zero outturns everything.

Therefore, do not turn with it.

It was good advice.

It also made every fight reactive. Defensive. It let the Zero dictate the terms.

O’Hare knew that.

He also knew manuals written in Florida and California did not always match the reality above Rabaul and Truk.

Manuals assumed you always had altitude.

That you always had backup.

That the enemy cooperated.

But combat was chaos. Bombers separated. Wingmen got shot down. You found yourself alone with a crippled bomber and six predators closing fast.

In that moment, the manual could become a coffin.

O’Hare had been thinking about that since his Medal of Honor mission. He had saved the Lexington not by obeying doctrine, but by ignoring it—pressing close, trusting aim and nerve.

Now he was doing it again.

But this time he wasn’t improvising.

He was applying principles.

He had thought through the physics. Tested the limits. Built a mental model of what the Hellcat could do if you stopped asking it to be a Wildcat or a Zero and let it be itself.

After Rabaul, he began sharing his techniques.

Not in formal briefings, at first.

In casual conversations. In the mud. By the planes.

He showed younger pilots how to manage energy, how to use the throttle like a weapon, how to read the Zero’s nose position and predict an overshoot, how to reverse without bleeding speed.

Some listened.

Some ignored him.

The skeptics said he got lucky. Said the Zeros were inexperienced. Said a Hellcat was still too slow.

But word spreads in war the way smoke spreads—fast, unavoidable.

Other pilots tried his methods.

They reported back.

The Hellcat turns better than we thought.

You can force a Zero into a high-speed fight.

You can win if you stay aggressive.

Training command took notice. Observers arrived to interview O’Hare. They wanted to standardize his tactics, turn them into doctrine, stamp them into the next wave of pilots before those pilots were stamped into the sea.

O’Hare resisted the idea of a neat manual.

He said every fight was different.

You couldn’t write a checklist for chaos.

You could only teach principles.

And there was tension.

Older pilots resented the attention. Said he was reckless. Said he was teaching young men to take unnecessary risks. Said dogfighting a Zero was suicide no matter what you told yourself.

O’Hare didn’t argue.

He just pointed to results.

His pilots were coming home.

The Zeros were not.

By November 1943, the war’s appetite had grown.

The Navy prepared for Operation Galvanic—the invasion of Tarawa. The fleet gathering in the Pacific was the largest yet assembled: dozens of carriers, thousands of aircraft, the kind of force that made the ocean feel too small.

The stakes were existential.

If the landings failed, the offensive stalled.

The Japanese knew it too. They threw everything at the fleet—night torpedo bombers, high-altitude scouts, tactics that felt like early drafts of something darker.

The tempo was unrelenting. Pilots were exhausted. Mechanics worked until their hands cracked. Sleep came in short pieces.

O’Hare was now air group commander aboard the USS Enterprise.

Responsibility changed a man. It didn’t make him louder. It made him sharper.

He was no longer just flying his own fight. He was coordinating defense. Balancing risk. Keeping the fleet alive.

Night fighting was still a black art. Radar-guided interceptions were experimental, half science and half prayer. The ocean at night had no horizon. No reference points. Just blackness and the faint glow of instruments.

On the night of November 26, radar picked up Japanese bombers approaching.

The report hit the ship like a cold hand.

O’Hare volunteered to lead a night intercept.

It was dangerous work. Not glamorous. Not the kind of fight where you could see the enemy clearly and believe you were in control.

Two wingmen launched with him.

They flew into a sky that felt like a sealed room—dark, tight, untrustworthy.

The radar controller vectored them in. Green blips on a scope. Voices clipped and urgent. Numbers and headings.

O’Hare flew by instrument and instinct. The Hellcat’s cockpit was cramped and dark. The engine’s blue exhaust flames flickered beyond the windscreen like small ghosts.

Then he saw it.

A Japanese “Betty” bomber, silhouetted against clouds.

He closed to point-blank range.

He fired.

The bomber exploded in a flash of orange and white.

The blast rocked his Hellcat, a sudden violence that felt too close.

He pulled up and scanned for more targets.

The radio crackled. Confused voices. Someone firing.

But at what?

A burst of tracer fire crossed in front of O’Hare’s nose.

Then silence.

His wingman called out, voice tight with alarm. He had lost sight of O’Hare.

The controller called for position.

No response.

The radio stayed silent.

Edward O’Hare did not return.

For days, search planes combed the ocean.

Nothing.

No wreckage.

No raft.

No body.

The official report listed him as missing in action, presumed dead.

Cause unknown.

Friendly fire.

Enemy gunner.

Mechanical failure.

The night keeps its secrets.

He was twenty-nine years old.

And the loss hit hard—not just because of what he had done, but because of what he was still teaching.

His methods were just beginning to spread.

His influence was just beginning to reshape tactics across the fleet.

But ideas, once released into desperate hands, don’t politely die when their owner disappears.

By mid-1944, the F6F Hellcat was the dominant fighter in the Pacific.

It accounted for nearly seventy-five percent of the Navy’s air-to-air kills.

The kill ratio against the Zero was thirteen to one.

Pilots who once mocked it now swore by it.

The tactics O’Hare pioneered became standard: high-speed maneuvering, energy management, aggressive reversals. Training syllabi changed. New pilots were taught to respect the Hellcat’s strengths instead of mourning its limitations.

Veterans spoke of O’Hare with quiet reverence.

Not as a loud maverick.

Not as a lone wolf.

Methodical. Thoughtful.

A pilot who understood the war as a system and found its leverage points.

Engineers at Grumman received feedback from pilots using those methods and refined the Hellcat—control surfaces adjusted, tuning improved, little changes built on what had been proved in combat.

The Hellcat became the most produced American fighter of the war—over twelve thousand built.

More enemy aircraft destroyed than any other Allied fighter.

Not the fastest. Not the most agile.

The most effective.

And its effectiveness was rooted, in part, in lessons teased out by a quiet pilot who refused to accept that “heavier” meant “helpless.”

His name was given to an airfield outside Chicago.

Millions of travelers pass through it every year.

Few know the story.

Fewer still know that the man it honors didn’t disappear in a daylight dogfight.

He vanished in the dark, leading from the front, pushing into uncertainty because somebody had to.

His Medal of Honor citation mentions heroism.

It does not mention curiosity.

Patience.

The willingness to question assumptions and test theories under fire.

But those qualities mattered as much as any kill count.

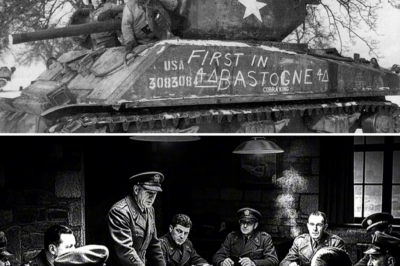

There was a photograph taken weeks before his last mission.

O’Hare stands beside his Hellcat, arms crossed, flight helmet under one arm. Face calm. Eyes tired but clear. No smile.

Men who flew with him remembered that look.

They said it was the look of someone who knew the risks and calculated them anyway—who did not pretend to be invincible, but refused to be paralyzed by fear.

The sky over Rabaul is long silent now. The jungle reclaimed the strips. The wrecks rusted into dust.

But somewhere, in log books and fading reports, O’Hare’s handwriting remained neat and precise.

The handwriting of a man who believed the answer to fear wasn’t faith.

It was preparation.

And the answer to impossible odds wasn’t luck.

It was understanding.

They mocked his “too slow” Hellcat.

They said it was too heavy, too forgiving, too stable to win a knife fight.

Then Edward O’Hare took it into combat and came back with answers.

He turned doctrine into data.

He made the possible larger.

And in doing so, he gave the pilots who followed him something more valuable than any metal ever could:

Permission.

Permission to trust their judgment.

Permission to test the limits.

Permission to survive.

THE END

News

CH2 – The Ghost Shell That Turned Tiger Armor Into Paper — German Commanders Were Left Stunned Silence

The first time Lieutenant Jack Mallory saw the Tiger, it wasn’t on a battlefield. It sat behind a chain-link fence…

CH2 – The Line Bradley Spoke When Patton Saved the 101st From Certain Destruction

The room in Verdun, France, was so cold the breath of sixteen commanders hung in the air like cigarette smoke….

CH2 – They Mocked His “Homemade Tank” — Until It Crushed 4 Panzers in Battle

The first time I saw the drawing, it looked like a kid’s bad idea made real. A boxy slab of…

CH2 – German general almost fainted: POW food was better than his in Germany

Captain Jack Henderson didn’t like speaking in front of crowds. He’d stood in the open with artillery walking toward him….

At The Hospital, My STEPBROTHER Yelled “YOU BETTER START…!” — Then Slapped Me So Hard I Did This…

Blood was dripping from my mouth onto the cold linoleum floor of the gynecologist’s waiting room. You’d be surprised…

A Karen Demanded the Window Seat for “Better Photos” — But the Passenger Refused to Move

Samuel had picked 14A the way some people picked wedding dates. Three weeks before departure, he’d opened the airline’s…

End of content

No more pages to load