The first time I saw the drawing, it looked like a kid’s bad idea made real.

A boxy slab of mismatched steel plates. Angles that didn’t match any manual. A turret that resembled a factory boiler someone had slapped on top in a hurry. Tracks that belonged on a farm, not a battlefield.

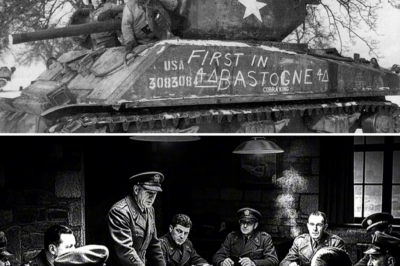

And yet, the caption typed beneath it in an old Army translation packet was dead serious:

IMPROVISED ARMORED PLATFORM. JULY 27, 1944. 0815 HOURS. NEAR REV, SOVIET UNION.

I was sitting in a fluorescent-lit room at Fort Belvoir, Virginia, in 1967—two decades after the war—because the Pentagon liked to collect lessons the way some men collect coins. The Cold War had turned history into a live weapon. Every scrap mattered. Even the scraps that looked like scrap.

Across the table, a civilian analyst with horn-rimmed glasses slid another page toward me.

“Here’s the interview excerpt,” he said. “The mechanic’s words. Translated twice. Russian to German to English.” He tapped the paper. “And here’s the after-action assessment. Soviet and German records both mention it.”

I’d been brought in because I could write. Because I could make a thing feel like a thing instead of a stack of reports. My job was to take this bundle of steel-and-blood arithmetic and turn it into a story that American officers would remember the next time somebody argued that only expensive, perfect equipment wins wars.

I stared at the drawing again. The turret looked like it would fall off if you sneezed on it.

“Who was he?” I asked.

The analyst shrugged like it didn’t matter. Like men were just data points on a chart.

“Senior Sergeant,” he said. “Dmitri Pavlovich—spelled three different ways in the file. Farm mechanic. Built it out of salvage. They called it ‘Dmitri’s coffin.’”

I let the name sit in my mouth for a second. Dmitri’s coffin.

“You’re telling me,” I said, “a guy welded a tractor into a tank and took out four German panzers?”

“Two destroyed,” the analyst corrected automatically. “One mobility kill. One forced withdrawal. Total time in combat: nineteen minutes.”

He said it like he was reading a weather report.

I looked down at the typed timeline:

0815—Vehicle advances.

0817—Lead Panzer fires, round deflected.

0818—Sakalov fires, turret ring hit, Panzer disabled.

0820—Second Panzer immobilized by track hit.

0821—Turret penetration, one Soviet crewman killed, one wounded.

0823—Third Panzer destroyed by side penetration, ammunition detonation.

0824—Fourth Panzer withdraws.

0834—Vehicle returns to Soviet lines at 3 mph.

A nineteen-minute argument against conventional wisdom.

Outside the window, Virginia summer pressed against the glass. Trucks hummed along Route 1. Somewhere, a jet cut a white line through the sky. America was building the future at a furious pace.

Inside the room, I was about to climb into a different machine entirely—a machine built from desperation, welded by a man who’d spent his life keeping harvest tractors alive with whatever metal he could find.

If you wanted to understand how it happened, you had to start where he started: not in a design bureau, not in a factory, not in a parade.

You had to start in mud.

He was born in 1915, in a small village near Tula, south of Moscow—agricultural country. Collective farm country. The kind of place where winter doesn’t ask permission and the soil doesn’t care about ideology.

His father, Pavl, drove the early Soviet tractors, STZ machines that turned human exhaustion into mechanical grind. Dmitri grew up around the sound of engines that never quite ran right. He learned to listen the way some kids learn to read—by the age of ten he could operate a tractor, and by fifteen he was the one older men called over when a machine made a noise they didn’t like.

There’s a kind of intelligence that doesn’t come from classrooms. It comes from standing in a field with the sun beating down and a harvest depending on you, and you’ve got a broken part, no replacement, and a pile of junk behind the shed.

You learn stress and torque without calling them that. You learn that “elegant” doesn’t matter if the wheat rots. You learn that a machine doesn’t need to be pretty; it needs to work.

By twenty he was the senior mechanic at the collective farm, responsible for equipment the entire harvest depended on. That meant repairs under pressure, improvisation as a reflex, making do as a philosophy.

Then June 1941 arrived.

Germany invaded, and the war didn’t knock. It kicked in the door.

Dmitri was drafted days after the invasion, his mechanical background flagged as “useful,” but usefulness in 1941 was a luxury the Red Army couldn’t always afford. He was assigned as an enlisted soldier to a rifle regiment—infantry first, specialist second—with a secondary duty keeping company vehicles alive.

The first months were catastrophe. Whole armies lost. Equipment abandoned. Tanks left behind not because they were dead, but because the crews didn’t know how to fix a broken track or start an engine in panic.

Dmitri watched functional machines become corpses simply because there was no time, no training, no fuel, no plan.

By September 1941, his regiment was down to thirty percent strength. Equipment losses exceeded ninety percent.

But Dmitri kept a few vehicles moving through improvised repairs, using salvage from destroyed equipment. It wasn’t magic. It was the same skill he’d used in the fields—look at what you have, understand what it needs, build the bridge between them with whatever metal is left.

A company commander noticed. Dmitri was formally assigned to maintenance. Not because the war suddenly valued mechanics, but because winter was coming and winter destroys vehicles faster than bullets if you let it.

The winter counteroffensive around Moscow turned the world into ice and smoke. Tanks broke down from cold. Trucks refused to start. Artillery tractors seized up like frozen hearts.

Dmitri kept equipment functional through improvisation that would have violated every technical manual—if manuals had still existed in the way the world used to exist.

In January 1942, a T-34 threw a track during combat. Standard procedure was to abandon it. Track repair under fire was considered impossible.

Dmitri didn’t accept “impossible” the way officers did. Impossible was a word people used when they didn’t know how.

He scavenged a wrecked German halftrack’s winch system and improvised tools. Under German artillery fire, he remounted the track in four hours. The tank returned to combat and later destroyed three German vehicles.

That incident didn’t just establish his reputation. It planted a splinter under his skin.

Because the lesson wasn’t only that he could fix a tank.

The lesson was that many Soviet tanks weren’t being defeated only by German guns—they were being defeated by systems. Poor training. Inconsistent supply. Inadequate maintenance. Doctrines that treated machines like they were invincible until they weren’t.

A well-maintained T-34 with a trained crew and adequate ammunition could beat German armor.

But those conditions rarely existed at the same time.

So Dmitri began asking a question that didn’t fit doctrine:

Why keep sending sophisticated tanks into situations where the conditions that made them effective didn’t exist?

Why throw precision machines into meat grinders?

By summer 1942, he’d been promoted to senior sergeant and assigned to a tank maintenance battalion near Rev, supporting armored forces. That gave him access to wrecks, salvage, workshop facilities—and a front-row seat to the problem repeating itself.

Soviet attacks would throw inadequately prepared tanks against prepared German defenses. Losses would be catastrophic. Gains would be thin.

Dmitri watched, and the frustration hardened into an idea.

Not a pretty idea. Not an idea that looked good on a chalkboard.

A brute idea.

What if the breakthrough vehicle didn’t need to be fast?

What if it didn’t need to be elegant?

What if it just needed to survive long enough to do one job—cross open ground under fire, absorb hits, keep moving, and deliver a gun where it mattered?

Agricultural tractors were built for reliability under harsh conditions with minimal maintenance.

If you added armor and a gun to a tractor chassis, you could create a slow breakthrough platform that could survive what tanks couldn’t.

It violated doctrine. Tanks were supposed to be speed and maneuver, not crawling steel boxes.

But Dmitri wasn’t trained by doctrine. He was trained by broken machines and stubborn seasons.

In March 1943, he requested permission to experiment with an improvised armored vehicle. The battalion commander, Major Victor Romanenko, was skeptical—but the kind of skeptical that comes from being desperate enough to listen.

“Build your tractor tank,” Romanenko said. “But it comes from maintenance stocks, not combat allocations. And if it doesn’t work, you’re back to regular duties.”

Dmitri took the deal.

He started with an STZ-5 agricultural tractor abandoned near the front. The engine was a tractor motor designed to plow at five miles per hour, not fight a war. Fifty-five horsepower. Low speed, high torque. Built to pull, not sprint.

Perfect for moving heavy loads slowly—exactly what he intended.

He built armor from whatever he could scavenge: destroyed Soviet tanks, damaged German vehicles, even boiler plate from an armored train blown apart nearby.

Nothing matched. Nothing fit properly. The thickness varied from quarter-inch mild steel to three-inch tank plate.

The welding was crude. Stick welding with inconsistent electrodes on dissimilar metals, ugly seams that looked like scars.

But Dmitri wasn’t building a showpiece. He was building a refusal to die.

He used multipass welding with slag removal between passes, creating joints stronger than the base metal in some places. Not because he knew metallurgy in the academic sense, but because he knew what failed and what held.

He understood something the mockers didn’t: you didn’t need a perfect design if you had enough steel in the right places.

The front glacis—the face that would take the worst fire—was three inches of salvaged tank armor angled at forty-five degrees.

The sides were two-inch plate from destroyed German vehicles.

The rear was only quarter-inch steel, enough for fragments but not direct hits. He accepted that weakness as part of the bargain, counting on his design to keep the enemy in front of him.

He improvised compartmentalization—separating crew from engine with additional armor plate—because he’d seen what happened when a single penetration turned a tank into a furnace.

The main gun was a 76 mm weapon salvaged from a destroyed T-34, mounted in a crude turret welded from boiler plate.

The recoil mechanism was damaged. A tank gun without proper recoil is a hammer with no handle—it tears apart whatever holds it.

Dmitri designed an improvised recoil system using hydraulic cylinders from tractor steering systems, springs from truck suspensions, and fluid-filled dampers fabricated from pipe and seals.

He tested by firing while the mount was secured to heavy timber framework. Three tests. Two redesigns. Finally: it absorbed enough recoil to be functional—“sort of,” as the file dryly noted.

The turret traverse was manual: a hand crank salvaged from an artillery piece, driving a rotating upper ring on ball bearings taken from destroyed trucks.

It was slow. Twenty seconds for forty-five degrees.

But slow was still movement. Slow was still a gun turning when it needed to.

By May 1943, it was complete.

It looked like a child’s sculpture made from scrap metal—mismatched plates, odd angles, a boiler turret on a tractor.

The mockery came immediately.

Mechanics called it Dmitri’s coffin, predicting it would kill its crew before it ever saw a German tank.

Tankers dismissed it as a tractor with delusions.

Officers considered it a waste of materials.

Even Major Romanenko had doubts.

And yet, when June 1943 brought German offensive operations near Kursk and every platform mattered, Romanenko authorized a combat trial.

The mission was simple: provide fire support for infantry defending against a German tank-infantry assault.

Dmitri’s vehicle rolled into position, crewed by four men—including himself—and waited.

Three Panzer III tanks appeared around eight hundred yards.

The improvised vehicle fired six times. Two hits. One mobility kill.

But the key detail—the detail that began to kill the mockery—was that it absorbed five return hits without penetration.

The thick front armor deflected shells that would have destroyed conventional vehicles.

It also revealed weaknesses: the slow traverse made tracking moving targets difficult. The crude sights prevented accurate fire beyond six hundred yards. The engine overheated after forty minutes. Ammunition storage improvised from wooden crates was vulnerable.

So Dmitri did what he always did: he modified.

He improved traverse using gearing from a destroyed tank. He fabricated better sights using optics salvaged from German vehicles. He installed additional cooling. He lined ammunition storage with fire-resistant material.

By September 1943, the jokes had gotten quieter.

The vehicle survived three engagements without catastrophic damage. It destroyed or disabled eight German armored vehicles.

It still looked ridiculous.

It still violated every principle of proper tank design.

But it kept working.

Function began to beat form in the eyes of men who cared most about not dying.

Combat employment through late 1943 was mixed. Heavy armor prevented penetration in many cases, but slow speed made repositioning difficult. Crude systems required constant maintenance. Crew losses forced repeated training.

By January 1944, Dmitri had trained three separate crews. One crew died in an artillery strike. Another was reassigned while the vehicle was down for repairs.

The third crew, including Corporal Ivan Petrov as gunner and Private Alexei Volkov as loader, developed proficiency with the crude systems.

The vehicle’s reputation became something like grudging respect.

It wasn’t elegant.

But it survived when conventional tanks didn’t.

Then July 27, 1944 arrived.

And the file’s nineteen-minute timeline became the reason I’d been called into that Virginia room.

0815 hours. Near Rev, Soviet Union.

The improvised armored vehicle rumbled forward with a sound like industrial machinery approaching its breaking point.

Inside, Senior Sergeant Dmitri Pavlovich—Sakalov, Soalof, however the letters landed in translation—gripped controls he’d fabricated from truck steering components and agricultural machinery parts.

A tractor motor designed for plowing at five miles per hour was now being asked to push thirty-two tons of welded steel plate, salvaged tank parts, and desperate innovation across a cratered battlefield at seven miles per hour max.

It could do seven, but only if you didn’t ask for more. The engine was governed for low-speed, high torque. It didn’t care what the war wanted. It cared what physics allowed.

Through a vision slit cut into quarter-inch boiler plate, Dmitri saw the reason this absurd machine had been authorized for a desperate assault:

Four German Panzer IV tanks, hull-down behind earthworks, dominating the approach to a critical bridge.

The bridge was needed for the Soviet offensive to advance. And the offensive was stalling.

The conventional Soviet tanks that should have taken the bridge—T-34s and KV-1s—were burning wrecks scattered across the killing ground. German 88 mm anti-tank guns had destroyed them in the first fifteen minutes.

Now German reinforcements were approaching.

The battalion commander had made an impossible decision:

Send forward the ridiculous improvised vehicle the mechanics had been mocking for weeks.

Let the crazy tractor mechanic try what proper tanks couldn’t.

Inside the turret, Petrov and Volkov worked their stations with the unnatural calm of men who’d been afraid too many times to waste fear now.

They all knew the numbers.

Open approach. No concealment. The Germans would see them from a thousand yards. They’d be under fire for at least five minutes before reaching effective range. The panzers were hull-down, minimal target profile.

Everything favored the Germans.

But Dmitri knew his vehicle’s singular advantage:

Its front armor didn’t care about doctrine.

It cared about thickness and angle.

At 0817, the lead Panzer spotted the approaching scrap heap and fired.

The round struck the front glacis at roughly six hundred yards.

The impact sounded like a giant hammer hitting an anvil.

Inside the vehicle, the air filled with the smell of burned metal and the ringing echo of steel striking steel.

Dmitri didn’t flinch away. He felt the hit in his bones the way you feel a tractor hit a stone buried under soil.

But the three-inch angled plate deflected the round.

In that moment, “Dmitri’s coffin” refused to become one.

Petrov began traversing the turret using the manual hand crank. Slow, brutal work. Twenty seconds for forty-five degrees.

The Germans fired again. And again.

Shells struck thick front armor and glanced off angled sides. Most deflected.

One penetrated thinner rear armor but failed to reach the crew compartment because Dmitri’s compartmentalization absorbed damage that would have disabled a conventional tank.

The vehicle kept moving.

Seven miles per hour felt glacial when you knew every second was a target.

But it was movement.

It was inevitability.

Dmitri aligned the 76 mm gun using crude sights fabricated from truck mirrors and welding glass.

The gun fired.

The improvised recoil system—tractor hydraulics and truck suspension parts—absorbed the shock enough to keep the mount from ripping itself apart.

The shell was armor-piercing, salvaged from ammunition stores.

At six hundred yards, it struck the lead Panzer’s turret ring—the junction between turret and hull, the structural weakness on every tank design.

The turret jammed.

Smoke erupted from hatches.

The crew began bailing out.

One kill.

The other three panzers shifted fire to the new threat.

Multiple shells hit Dmitri’s vehicle from different angles.

Most deflected. Some gouged. Some rang the interior like a church bell struck by a hammer.

Dmitri continued advancing because the tractor engine would do one thing reliably: keep pushing if you kept feeding it.

At five hundred yards, Dmitri fired again.

The second Panzer took a hit to its track and road wheels.

It stopped moving.

A mobility kill is a kind of death that still breathes for a moment—metal alive but trapped.

The crew abandoned it rather than face continued fire from an opponent they couldn’t effectively damage.

At four hundred yards, the third Panzer scored a direct hit on the improvised turret.

The shell penetrated the crude boilerplate armor.

Corporal Ivan Petrov—gunner, believer, the man who’d learned Dmitri’s hand-cranked turret like it was a musical instrument—was killed instantly.

Private Alexei Volkov, loader, was wounded.

The turret became a shattered space filled with smoke and splintered metal.

But the engine and drivetrain remained functional.

The compartmentalization Dmitri had built—the separation between crew and engine—saved his life.

And now, with his gunner dead and his loader wounded, Dmitri had to do the impossible inside a broken turret:

Load and fire the main gun himself while simultaneously operating the vehicle.

It was nearly impossible.

But desperation creates capability the way pressure makes coal into diamond. Not clean. Not pretty. Real.

At three hundred fifty yards, alone in the shattered turret, Dmitri loaded a shell.

Aimed.

Fired.

The shell struck the third Panzer’s hull, penetrated side armor, and ignited ammunition.

The internal explosion was catastrophic.

The turret blew completely off the hull.

Debris went two hundred feet into the air.

A kill so violent it taught a lesson without words.

The fourth Panzer—having watched three companions destroyed or disabled by what appeared to be a mobile scrap heap—made a decision that said everything about war’s psychological side:

It withdrew.

It reversed behind cover and retreated toward secondary defensive positions.

The bridge approach was clear.

The ridiculous thing had achieved what conventional forces couldn’t.

Nineteen minutes in combat.

Eight shells fired.

Five hits.

Two confirmed kills.

One mobility kill.

One tactical kill through forced withdrawal.

One Soviet crewman dead.

One wounded.

And a vehicle that limped back to Soviet lines at three miles per hour trailing smoke and leaking fluids, barely functional—alive.

The file called it “vindication.”

But that word doesn’t capture what it means to be mocked for building something ugly, and then watch it work when everything else burns.

It doesn’t capture what it means to win and still carry a death in your pocket.

Dmitri had built a machine that refused to stop fighting.

And the price was Ivan Petrov.

Back in Virginia, in 1967, I read the Soviet after-action assessment and heard the same cold tone I’d heard in American reports:

Subject vehicle: improvised armored platform based on agricultural tractor chassis.

Engaged four Panzer IV tanks in prepared defensive positions.

Results: two destroyed, one mobility kill, one withdrawal.

Friendly casualties: one KIA, one WIA.

Vehicle damage: moderate, repairable in field conditions.

Comparative analysis: previous assault by six T-34 tanks resulted in complete loss with zero enemy casualties.

Recommendation: document construction methodology for potential replication in similar situations.

Note: effectiveness situation dependent. Not universal replacement.

Clinical precision.

But I couldn’t stop staring at the human line buried inside the numbers:

One KIA: Corporal Ivan Petrov.

Later, in a 1967 interview conducted for military historical archives—this part of the file was why the Pentagon cared now—Dmitri reflected on the mockery his vehicle had received.

“People laughed at it because it didn’t look like a tank,” the translation read. “But I wasn’t building a tank. I was building an armored platform that could survive long enough to complete a mission. Appearance doesn’t matter if function is adequate. The vehicle did what it needed to do. That’s the only measure that counts.”

The interviewer asked about the July 1944 engagement.

Dmitri’s response carried the moral weight the after-action report couldn’t:

“We destroyed German tanks, but Ivan Petrov died doing it. Was the trade-off worth it? From military perspective, certainly. From human perspective, I’m not as certain. Ivan believed in what we were doing. He died succeeding. Perhaps that’s the best any soldier can hope for.”

In my American chair, under American fluorescent lights, I felt the old, familiar contradiction tighten in my chest.

We love stories where ingenuity beats the odds.

We love heroes who build something out of nothing.

We love victories that prove the mockers wrong.

But war doesn’t give you victories without receipts.

If the machine lives, it does so because men pay.

And Dmitri, farm mechanic turned soldier, seemed to understand that with a clarity that made his triumph heavier, not lighter.

The file went on, because history always goes on.

The July 1944 success brought consequences Dmitri hadn’t wanted.

Higher headquarters ordered him to construct additional improvised vehicles using similar methodology.

Dmitri resisted—not because he didn’t believe in his work, but because he understood why it worked.

His vehicle wasn’t a product. It was an answer to a specific question with specific materials at a specific time.

Mass production would require standardization that would erase the custom adaptation that made it effective.

Instead, he trained mechanics on principles, not blueprints:

Understand tactical requirements.

Assess available materials.

Design for survivability in the expected threat environment.

Accept crude execution if the function holds.

Build, test, modify.

By October 1944, other maintenance battalions built similar vehicles customized to their own materials and needs.

Some worked. Others failed catastrophically.

The difference wasn’t welding skill.

The difference was understanding.

Dmitri’s original vehicle continued through fall 1944, participating in twelve additional engagements, achieving seven confirmed kills and numerous assists.

But tempo, wear, and damage finally rendered it non-functional in December 1944.

By then, Dmitri had been promoted to junior lieutenant and assigned to a tank training command to teach improvised vehicle construction and modification—because the war had taught the Soviet machine what farmers always knew:

Sometimes the best mechanic is as valuable as the best gun.

The war ended in May 1945 with Dmitri serving as a maintenance officer near Moscow.

He’d survived four years of brutality.

He’d created a weapon that “shouldn’t have been possible,” according to men who only believed in what factories produced.

He’d trained hundreds of mechanics in improvisation.

He retired from military service in 1953 as a captain and returned to agricultural machinery work—back to the world that had trained him, back to harvests and engines and mud that didn’t explode.

He rarely discussed his wartime service. Not because he was ashamed. Because he viewed it as necessity, not glory.

The physical vehicle that destroyed the panzers was scrapped in 1945. Salvaged for parts after damage made it uneconomical to repair. No photographs of that specific machine survived, though images of similar improvised vehicles existed in archives.

But Dmitri’s drawings—found among his papers after his death in 1981—showed sophistication beneath the crude execution:

Armor placement accounting for likely impact angles.

Internal compartmentalization maximizing survivability.

Mounting systems using principles that would not be formalized in texts for decades.

What looked crude from a distance was deliberate up close.

Dmitri died in 1981 at sixty-six, in his hometown near Tula. His obituary focused on his postwar work and family, mentioning his decorations, then moving on—because history, in the places it happens, often treats its quiet geniuses as ordinary men.

German records documented the loss of four tanks on July 27, 1944 to an “unusual Soviet heavy armored vehicle, possibly experimental.”

The Germans spent resources trying to identify a tank that didn’t exist.

And that, too, was part of the story: the psychological impact of facing something you can’t categorize.

In the file’s final pages, American analysts—men like the one sitting across from me—had added their own commentary. They listed factors behind the vehicle’s success beyond armor thickness:

The tractor base provided reliability; farm equipment was designed for harsh conditions with minimal maintenance.

Mismatched armor plates at random angles created complex deflection geometry.

Slow speed forced deliberate tactics, reducing reckless exposure.

Simple systems had fewer failure points than sophisticated designs.

Crew psychology—knowing they were vulnerable—encouraged caution and better judgment.

And then, because Americans always translate war into budgets sooner or later, the cost analysis:

The improvised vehicle was built from salvaged materials, minimal new procurement. Estimated cost if purchased: about 2,000 rubles wartime currency.

A factory-built T-34: roughly 130,000 rubles.

Less than two percent of the cost, and in that one nineteen-minute slice of hell, it achieved mission success where six T-34s had died for nothing.

A cheap answer that outperformed the expensive one in a specific, brutal problem set.

The lesson in plain English:

Sometimes the best solution isn’t the most advanced one.

Sometimes it’s the one designed exactly for the problem at hand.

Even if it looks ridiculous.

Even if people laugh.

Even if it runs on a tractor engine that never wanted to be in a war.

The analyst across from me leaned back, watching my face.

“Well?” he asked.

I looked at the drawing one last time. The ugly turret. The mismatched plates. The vision slit cut into boiler steel.

I imagined Dmitri inside it at 0817 when the first Panzer round hit—how the interior would have rung, how the smell of burned metal would have filled his nose, how the whole thing might have felt like it was coming apart.

I imagined him hand-cranking the turret while shells slapped steel. Loading the gun himself after Petrov died. Driving and firing inside smoke and shattered metal because stopping meant the bridge stayed closed and more men died.

Then I imagined the other side: Petrov’s body, the wound in Volkov, the limp back to friendly lines at three miles per hour trailing smoke.

Victory and cost welded together.

“It’s a hell of a story,” I said.

The analyst nodded like that was the only acceptable answer. “Can you write it?”

I slid the packet closer, the way you pull a heavy object toward you because it has to be moved.

“Yeah,” I said. “But I’m not going to write it like a miracle.”

He frowned. “Why not?”

Because miracles make war sound clean.

Because “they mocked him until he crushed four panzers” is true, but it’s not the whole truth.

Because if you don’t say Ivan Petrov out loud, you turn a man into a footnote.

Because the machine wasn’t brave.

The men were.

I tapped the timeline on the page—0815 to 0834.

“Nineteen minutes,” I said. “That’s all it took to turn a joke into doctrine.”

Then I tapped the casualty line.

“And that’s all it took to remind everybody what doctrine costs.”

The analyst didn’t answer. He didn’t need to. In the end, files are made of silence as much as ink.

I gathered the pages into a neat stack, already hearing the rhythm of the story in my head—tractor engine strain, steel ringing, a hand crank turning slow, men choosing to keep moving because stopping was worse.

Outside, the Virginia afternoon went on, indifferent and bright.

Inside, the ugly machine from a distant battlefield kept rumbling forward—still refusing to stop fighting, even on paper.

THE END

News

CH2 – The Ghost Shell That Turned Tiger Armor Into Paper — German Commanders Were Left Stunned Silence

The first time Lieutenant Jack Mallory saw the Tiger, it wasn’t on a battlefield. It sat behind a chain-link fence…

CH2 – They Mocked His “Too Slow” Hellcat — Until He Outturned 6 Zeros and Shot Down

They called it a tank with wings. Not to its face, not officially—not in front of the commander or the…

CH2 – The Line Bradley Spoke When Patton Saved the 101st From Certain Destruction

The room in Verdun, France, was so cold the breath of sixteen commanders hung in the air like cigarette smoke….

CH2 – German general almost fainted: POW food was better than his in Germany

Captain Jack Henderson didn’t like speaking in front of crowds. He’d stood in the open with artillery walking toward him….

At The Hospital, My STEPBROTHER Yelled “YOU BETTER START…!” — Then Slapped Me So Hard I Did This…

Blood was dripping from my mouth onto the cold linoleum floor of the gynecologist’s waiting room. You’d be surprised…

A Karen Demanded the Window Seat for “Better Photos” — But the Passenger Refused to Move

Samuel had picked 14A the way some people picked wedding dates. Three weeks before departure, he’d opened the airline’s…

End of content

No more pages to load