February 1943.

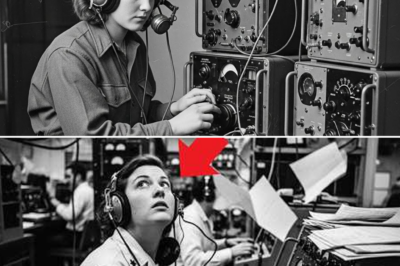

The Spitfire clawed its way up through the gray over the English Channel, engine howling, prop biting into the frozen air. Inside the cockpit, Flight Lieutenant James Cartwright watched the altimeter wind past fifteen thousand feet, then sixteen, then eighteen.

The sky ahead was a pale, featureless wall. Cloud. Fog. War.

His breath exploded out of him in sharp bursts inside his oxygen mask, heart pounding from the steep climb and the call that had sent his section scrambling from Tangmere a few minutes earlier.

“Bandits, angels eighteen, vector zero-seven-five.”

German fighters. Somewhere above the bombers, somewhere in this murk.

He glanced left to check his wingman’s position—

—and saw nothing.

The world beyond the curved Perspex canopy had vanished.

Not faded.

Not blurred.

Vanished.

White.

The glass had gone opaque from the inside, a milky curtain that turned a war machine into a coffin.

“Bloody hell,” Cartwright muttered, wiping at the canopy with his glove in a useless, frantic swirl. The frozen plastic smeared under his hand, the fog blurring into streaks.

His mind supplied what his eyes couldn’t see: Messerschmitts rolling down on them out of the cloud. Cannons. Tracers. His wingman somewhere out there, maybe too close, maybe too far.

The radio crackled in his headset.

“Leader, I’ve lost visual!”

“Where the devil are you?”

“I can’t see you, can’t see anything, can’t—”

Cartwright did the only thing his training and the previous weeks of experience had told him might work. He reached for the canopy handle, yanked it a few inches open.

A blast of arctic air hammered his face like a fist.

The roar of the slipstream surged into the cockpit, tearing at his mask, his scarf, his exposed cheeks. The fog cleared as the thick, frozen wind sheared away the condensation—but at a price. His fingers, already numb on the stick, flared with pain and then started to fade.

He squinted through watering eyes.

For a heartbeat, a Spitfire flickered into view off his left, so close he could see the pilot’s startled face.

Cartwright jerked the stick right, instinct pulling him away. The other pilot did the same, their wingtips missing by yards.

It was the third near-collision that week.

Three others hadn’t been near misses.

They’d been strikes.

Three pilots in his wing had died in the last ten days not from bullets or flak or mid-channel ditchings, but from simple blindness. From climbing into cloud, breathing like the scared, sweating men they were, and fogging their own canopies until they lost the horizon, their wingmen, and their lives.

The winter of 1943 was brutal over Northern Europe.

It wasn’t just the cold.

It was what the cold did to the machines.

The White Death

They called it the “white death.”

Not because of snow.

Because of fog.

Because moisture from a pilot’s own breath turned cockpit glass opaque within seconds at altitude, every time warm, humid air from lungs met the skin-freezing chill of Perspex hammered by two-hundred-mile-an-hour slipstream.

It happened on climbs, when fighters rushed up to meet enemy bombers. It happened in dives, when they chased targets down through layers of air. It happened in turns and rolls, when adrenaline spiked and breathing quickened.

Right when clarity mattered most.

You can’t dogfight what you can’t see.

You can’t escort bombers if you lose visual contact with them in cloud.

You can’t even get home if you can’t read your instruments through a cataract of condensed breath.

Standard procedure was crude and cruel.

Crack the canopy.

Let the freezing outside air pour in.

The slipstream would scour the fog from the inside of the canopy in seconds. It worked every single time.

It also turned the cockpit into a wind tunnel at three hundred miles an hour.

Temperatures inside the cabin plunged to twenty below.

Oxygen masks iced over. Fingers stiffened. Eyelids froze. Pilots returned from sorties with faces raw and mottled, eyes bloodshot, speech slurred from cold exposure. Some flew entire missions with the canopy open, choosing frostbite over blindness.

Ground crews wrapped them in blankets when they stumbled down the ladder, walked them to the medical tent while they shook and tried to light cigarettes with shaking hands.

Flight surgeons logged it as “cold exposure.”

Command logged it as “acceptable loss.”

But the numbers didn’t care what anyone called it.

Between December 1942 and March 1943, RAF Fighter Command recorded thirty-seven incidents of “spatial disorientation attributed to canopy fogging.” Eleven resulted in crashes. Eight in mid-air collisions.

The rest were chalked up as aborted intercepts, missed kills, bombers that got through to drop their loads because the people sent to stop them couldn’t see.

Luftwaffe intelligence noticed.

They weren’t stupid.

They circulated briefings to their fighter units: the RAF had a cold weather vulnerability. Their canopy design fogged badly. Their pilots had to crack their canopies in the cold.

Tactics adapted.

German fighters would bait Spitfires into climbing into cloud, then roll away and vanish, letting the Brits fly blind in that white hell, waiting for a mistake they could exploit.

It wasn’t heroics.

It was physics.

And physics was killing men in ways bullets never could.

Engineers at the Royal Aircraft Establishment at Farnborough knocked themselves out trying to fix it.

They tested anti-fog pastes.

They smeared too thick, too thin, they blurred.

They tested heated glass.

It cracked under stress, or it failed when battle damage cut a wire, leaving pilots worse off than before.

They added ventilation ducts.

They froze shut, or they channelled moist air into the wrong places.

Every solution added weight, added complexity, added something else that could break.

None of it worked under the violence of combat conditions.

So pilots adapted.

They breathed shallow.

They cracked their canopies from takeoff to landing.

They learned, by heart, the layout of their instrument panels so they could fly by feel instead of sight when the fog came.

It was resourceful, brave, and utterly insane.

On the ground at RAF Tangmere, a maintenance officer named Peter Holloway watched another frozen, exhausted pilot climb down from a Spitfire, cheeks white with frostbite where the mask had leaked, eyes red-rimmed, fingers barely able to unbuckle his harness.

Right then, he decided enough was enough.

The Man on the Ground

Peter Holloway wasn’t a designer.

He didn’t have a degree. He didn’t belong to any fancy society. He’d never stepped foot in an aeronautical engineering classroom.

He was, on paper, a “maintenance officer.”

Ground crew.

While pilots got their portraits painted and their names in the paper, men like Holloway walked the flight line with grease on their hands and oil on their sleeves, their work acknowledged mainly when it wasn’t done and something fell off an airplane.

But he understood machines.

He’d grown up in Coventry in the shadow of motor works, listening to his father come home from Daimler, talking about tolerances and torque over supper. His uncle worked at Armstrong Siddeley on assembled engines that rattled windows when they were tested.

By twelve, Peter could take apart a magneto and put it back together without losing a screw.

By fourteen, he was an apprentice rigger at Hawker’s Canbury Park facility, tensioning fabric over wooden airframes, learning the difference between “tight” and “too tight” in his fingertips.

By eighteen, he led riggers on Hart biplanes, the kind of aircraft that were dinosaurs by the time war rolled around, but which had taught him things no textbook ever would: how wood flexes in cold, how metal shrinks, how a misaligned fitting feels under a spanner.

He moved into hydraulics next.

Pressure, flow, leaks. The way fluids behaved under load. The way a single clogged line could lock a landing gear or freeze a control surface.

When war came, he enlisted without hesitation.

They didn’t need him in a cockpit.

They needed him under wings.

In 1941, he arrived at Tangmere as a flight sergeant.

By 1943, he’d clawed his way to warrant officer, acting as maintenance officer for an entire fighter squadron. He oversaw daily inspections, emergency repairs, battle damage fixes that had to be done in hours, not days.

He didn’t seek rank.

He sought solutions.

There was a reputation around him.

“Give it to Holloway,” pilots said when something was wrong with their airplane but nobody could find it. “He’ll sort it.”

When a gun jammed repeatedly, he figured out the microscopic burr inside the breach.

When a hydraulic line kept popping under G-load, he traced the vibrations that only appeared in one specific maneuver.

He read technical manuals, yes. But more importantly, he read the machines themselves.

He listened.

He watched.

He made connections others missed.

And now, watching a pilot stumble away from a frostbitten sortie for the third time that week, he realized the biggest threat to his pilots’ lives wasn’t something German.

It was condensation.

Asking the Wrong Questions

Holloway started with questions.

Simple ones, the kind anyone could’ve asked but somehow nobody had, or nobody had followed far enough.

Why does the canopy fog?

Because warm, moist air from the cockpit meets cold glass.

Why is the air moist?

Because the pilot exhales water vapor.

Why can’t it vent?

Because cockpits are sealed—pressurization, aerodynamics, structural strength.

Why can’t we just leave a gap?

Because open canopies cause drag, turbulence, and hypothermia.

Round and round and round.

Every answer led back to “that’s just how it is.”

He walked the flight line at dawn, hands in his jacket pockets, breath pluming the same way the pilots’ did a few hours later at altitude.

Ground crews were sliding canopies back to check gun sights and wipe down instruments. As they did, he noticed something he’d never really paid attention to before.

A thin line of frost formed along the interior rail where cold metal met warmer inside air.

A boundary.

A threshold.

It was a small thing.

Most men ignored it, or scraped it off with a gloved thumb.

But Holloway’s brain snagged on it.

If there was frost at that interface on the ground, what was happening in flight, when the temperature difference was much greater? Was condensation forming in predictable patterns, or at random?

He needed to see.

He started spending his evenings in the cockpit of a grounded Spitfire.

Not a glamorous duty. The aircraft was “off line” for a hydraulic repair. It was as good a test bed as he’d ever get.

He’d climb in at dusk, pull the canopy shut, and simply sit there breathing.

He watched where the fog formed.

First at the top.

Always at the top.

It started as a faint mist near the highest curve of the Perspex, where the canopy was furthest from his face and the air least disturbed. In seconds, under controlled conditions, it spread, crawling downward in a veil.

Thick near the frame, thinner in the center.

He touched the glass with a thermometer—nothing fancy, just one he’d liberated from stores. The top panels were coldest. The side panels slightly warmer. The area dead ahead, where his head blocked part of the air, stayed clearer slightly longer.

Patterns.

He saw patterns.

Meanwhile, official channels treated the fogging as a temperature problem: heat the glass, heat the cockpit, cool the air.

Holloway started to suspect that temperature was only the symptom.

The disease was stagnation.

Warm moist air hung near the glass too long. It didn’t move.

Stagnant air saturates.

Saturated air condenses.

If you could move the air—gently, constantly—you might never reach saturation at the surface.

Not with heaters that cracked the Perspex.

Not with fans that added weight and broke.

With flow.

Passive flow.

He dug out an old textbook on fluid dynamics from a stack of battered volumes someone had left in the station library. He’d taken it home once, thought it too abstract, then kept it anyway because he hated waste.

Now he read it by lamplight after his shift, pencil marking passages about laminar flow, boundary layers, pressure differentials.

Flight crews on the station played cards or wrote letters home.

Holloway ran his finger along diagrams of airflow over wings and thought: What if I treated the canopy like an airfoil surface, not a fishbowl lid?

What if, instead of fighting the slipstream, he used it?

The Mockery

At first, he did what the rulebook demanded.

He took his observations and tentative ideas to his commanding officer, a man who’d flown in the last war and now spent most of his time trying to juggle sortie counts with repair schedules.

“Canopy fogging,” Holloway said, laying sketches on the desk. “It’s killing our boys as surely as flak. I think I have a way to manage airflow inside the cockpit to prevent it.”

The CO skimmed the top sheet.

It showed a cross-section of the canopy rail with a narrow gap cut into it and a small deflector angled upward.

“Cut into the canopy?” the CO said.

“Into the rail,” Holloway clarified. “Not the main frame. A quarter-inch slot along here. The slipstream will push a thin sheet of air up across the inside of the Perspex. It will keep the boundary layer moving. No stagnation. No condensation.”

“You want to crack the canopy permanently,” the CO said, tone flat. “Deliberately bring cold air into the cockpit.”

“In a controlled way,” Holloway said. “Not full open like they do now. Just enough to keep the glass clear. The opening we’re forced to use now is inches. I’m talking fractions.”

The CO shook his head.

“Peter, we have protocols,” he said. “The canopy design’s been tested at Farnborough. Approved by the Air Ministry. You don’t just cut holes in it because you’ve got a bright idea. Unauthorized modifications to airframes are a court-martial offense.”

“I know the rules,” Holloway said. “I also know eleven pilots have died in three months because they couldn’t see. That doesn’t include near misses. James Cartwright nearly collided with his own wingman yesterday. I saw the paint they traded.”

The CO sighed, rubbing his temples.

“If you want to propose a modification, there’s a process,” he said. “You submit a report. It goes up the chain. The design folks examine it, maybe try it in a lab, maybe not. If they like it, they might trial it. At best, you’re looking at… four months?”

Holloway thought about four months of winter flying.

Four months of fogging.

Four months of funerals.

“Sir,” he said, “with respect—”

“There is no ‘with respect’ when it comes to cutting into a Spitfire without authorization,” the CO snapped. “I appreciate the initiative. I do. But we can’t have every maintenance officer in Fighter Command hacking up airframes based on gut feeling. This isn’t a garage, Holloway. It’s the RAF.”

Afterward, in the mess, when word got around that “Holloway wants to crack canopies on purpose,” the opinions were swift.

One pilot snorted into his tea.

“Next he’ll suggest we take our boots off so we can feel the rudder better,” he said.

Another shook his head.

“If I want a draft in my office, I’ll open the window myself,” he said. “Don’t need some ground pounder deciding to drill holes.”

Even one of the younger riggers, boys Peter had trained himself, looked doubtful.

“Sir,” he said quietly one evening, “they say you want to turn the Spits into open-cockpit kites again.”

Peter managed a thin smile.

“They’re already flying open cockpit half the time,” he said. “I’m trying to give them a way not to.”

But the mockery stung.

Not because his pride was delicate—life in the motor works had burned that out of him—but because it revealed a deeper problem.

Nobody up the chain could see past the idea that “tight” equals “safe.”

He wanted to introduce a gap, controlled, deliberate, in the right place.

They heard “gap” and imagined a hurricane.

So he stopped talking.

And started cutting.

The Unauthorized Cut

He picked his test subject carefully.

Spitfire Mk Vb, serial number P8672. Grounded for hydraulic issues, scheduled to be out of action for several days while parts came from the depot.

Good. He needed time.

He rolled her into the far bay of the hangar one evening, long after the last engine run had finished and most of the crew had drifted back to billets. The wind outside found every crack in the big doors, whistling through the rafters, rattling tools.

He climbed into the cockpit with a jeweler’s saw, files, emery cloth, and a deflector he’d fashioned from scrap aluminum.

The Perspex canopy sat on rails of sturdy metal. He ran a finger along the base just behind the armored windscreen, feeling the temperature differential between inside and out.

Then he marked a line, exactly a quarter inch high, running the width of the canopy’s lower edge.

He began to cut.

The saw’s tiny teeth whispered through the metal, each stroke soft, controlled. It was delicate work, like surgery. One slip and he’d gouge into the frame. One burr left behind and he’d create a crack point under load.

He worked by the light of a shaded lamp. The hangar smelled of metal filings and oil.

He didn’t think about court-martials, or demotion, or what his father would say about cutting into a “perfectly good machine.” He thought about breath fogging on cold glass, about pilots groping for canopies with gloved hands while trying not to die.

He finished the cut, smoothed it, ran a cloth over it until it felt like one continuous surface.

Then he climbed out, moved around to the side, and held his hand against the rail from the outside. At rest, there was no gap big enough to notice. Only by leaning close, eye at level, could he see the hairline slit.

He screwed the little deflector inside, a curved lip that would encourage any incoming air to arc upward toward the canopy instead of blasting straight into the pilot’s face.

When he was done, he wiped his hands on a rag, stood in the cold hangar, and let himself feel something like hope.

Then he put the tools away, closed the logbook with its tidy lies about “hydraulic checks completed,” and went back to his quarters.

He slept badly, dreaming of cracked canopies shattering at altitude.

Flight Lieutenant Cartwright

The next problem was finding someone crazy—or desperate—enough to fly it.

He considered flying the test himself. He was rated on light aircraft, had a few dozen hours in training planes. But a Spitfire at altitude wasn’t a Tiger Moth in a field. If something went wrong—if the canopy failed structurally, if the airflow upset the tail, if some unforeseen resonance set up a vibration—the pilot needed to be someone who could handle it without panicking.

That wasn’t him.

He needed a combat pilot who trusted him more than they trusted the regulations.

He found his answer, ironically, in the same man whose near miss had started this.

Flight Lieutenant James Cartwright.

Cartwright was twenty-four and looked older in that way men did when they’d spent too much time cheating death. He had the calm, deliberate manner of someone who knew that flinging himself at the enemy in a burst of heroics was less useful than coming back alive and doing it again tomorrow.

He’d flown sixty-two combat sorties. He’d shot down German fighters. He’d escorted bombers. He’d lost friends.

He’d also been grounded twice for cold injuries.

Holloway found him in the dispersal hut, sitting on an overturned crate, hunched over a mug of tea gone lukewarm.

The room smelled of wet wool, cigarettes, and tension. A map on the wall showed routes and altitudes and little pins marking where “incidents” had occurred. Some pins had names beside them. Some just had dates.

“You got a minute, sir?” Holloway asked.

Cartwright glanced up, polite but wary.

“A minute’s about all I’ve got, Warrant,” he said. “We’re likely to be scrambled any time Jerry gets bored.”

Holloway nodded.

“I’ve been working on the fogging issue,” he said, getting to the point. “I think I have a fix. I’ve tested it on the ground. I need someone to test it in the air.”

Cartwright watched him for a second, looking for a joke.

“You and every boffin at Farnborough,” he said. “They’ve smeared so much paste on my canopy I can’t tell if I’m in a Spit or a fish tank.”

“This isn’t paste,” Holloway said. “It’s airflow. A small controlled gap in the canopy rail to pull slipstream inside and wash the glass from the inside. It kept a cockpit clear at fifteen below in tests last night. On the ground, mind. Not at twenty thousand feet.”

Cartwright’s eyebrows rose.

“You cut a gap in the canopy?” he asked. “On purpose?”

“Yes.”

“Is that… permitted?”

“No.”

Cartwright let out a short, humorless laugh.

“They’re already making us fly with the canopy cracked half open like bloody barnstormers,” he said. “And you’re the one in trouble for making a smaller gap?”

“Something like that,” Holloway said.

Cartwright picked up his mug, swirled the dregs, then set it down.

“Which kite?” he asked.

“P-eight-six-seven-two,” Holloway said.

Cartwright knew them all by number and quirk.

“Hydraulic bird,” he said. “She’s fit to fly?”

“As fit as any of them,” Holloway said. “I’ve tested controls. No issues.”

Cartwright considered the ceiling, the damp slowly creeping into its planks.

“What’s the worst that happens?” he asked. “Cold draft and no improvement?”

“Worst?” Holloway said. “If I’ve misjudged the flow, it could cause buffeting. It might make more noise. If I’ve somehow weakened the rail—which I don’t believe I have—stress at certain angles could crack the canopy. You’d have to turn back.”

“And the best?” Cartwright asked.

“Best, you climb to twenty, breathe like a normal human, and still see the horizon,” Holloway said.

Cartwright looked at him, really looked, weighing experience against rank, a man’s character against a system’s rules.

“You know they’ll hang you out to dry if this goes sideways,” he said.

“I know,” Holloway replied.

He also knew that if he did nothing, more pilots would die because of condensation and cowardice at desks.

Cartwright stood.

“Right then,” he said. “Let’s see if your bloody quarter-inch gap does what the Air Ministry couldn’t.”

The Test Flight

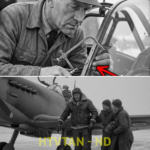

Morning broke sullen and cold over Tangmere.

Low cloud clamped down on the station like a lid. Temperature reports from Met came in bleak: minus thirty at twenty thousand feet, humidity high enough to make fog from a whisper.

Perfect.

Holloway walked out to P8672, hands shoved in his coat pockets, the breath from his own lungs fogging in front of his face like mockery.

The Spitfire squatted on her wheels, frost limning the edges of her wings, exhaust stains along the fuselage like war paint.

Cartwright appeared, zipped into his flight gear, helmet dangling from one hand.

Ground crew swarmed, checking oil, topping off fuel, tugging chocks.

No one paid particular attention to Holloway.

That was how it should be.

He joined the small flurry at the nose, checking cowling fasteners, running a hand along the leading edge of the wing, tapping the oleo struts.

“Anything I should know?” Cartwright asked quietly as he climbed the portable ladder up to the cockpit.

“You’ll feel a slight draft near your shoulder,” Holloway said. “Not a gale. If anything feels wrong, anything, you abort. There’s no heroism in proving a point.”

“There’s no heroism in flying blind either,” Cartwright said. “We’ll see.”

He settled in, strapping down, his body moving through the ritual of preflight checks like a choreographed dance.

Holloway leaned up, pointing to the rail without making it obvious.

The gap was invisible from where Cartwright sat, but the pilot nodded anyway, acknowledging.

“Good luck,” Holloway said, stepping back.

Cartwright started the engine.

The Merlin coughed, spat, then roared to life, spinning up into a hungry growl that vibrated through the concrete. Vapor streamed from exhaust stacks, dissipating in the cold.

After the run-up, the tower cleared him.

He taxied to the end of the runway, paused, then pushed the throttle forward.

The Spitfire leapt like a living thing, tail up, wheels lifting, sky reaching out to meet her.

Holloway watched, binoculars raised, as P8672 climbed into the low cloud and vanished.

He stood there, stationary in the chill wind, watching empty air, until his fingers, gripping the binoculars, went numb.

Up in the cockpit, Cartwright climbed.

Five thousand feet.

Ten.

So far, his breath fogged his mask but not the glass. That was normal in the early climb. Most fogging incidents didn’t start until fifteen or so.

At twelve thousand, he flexed his fingers deliberately, watching his own breath billow inside the mask, feeling his heart rate creak up as the altimeter climbed.

Fifteen thousand.

A faint whitening at the top of the canopy.

Habit screamed: crack it open, clear it now, don’t be stupid.

He didn’t.

He tightened his grip on the stick, forced himself to breathe normally, not shallow, not panting. It went against training, against muscle memory.

The faint whitening stayed faint.

The quarter-inch gap along the rail whispered against his left shoulder, a thread of air cold enough to remind him the outside world still existed, nothing like the gale that used to hit when he slid the canopy back.

He climbed more.

Eighteen thousand.

Twenty.

The canopy stayed clear.

Not pristine; a faint film clung to corners, like the veil you get on your glasses when you go from air conditioning into humidity and back.

But he could see.

He could see the horizon where cloud and sky met.

He could see vague shapes of country beneath, where breaks in cloud revealed the patchwork of fields.

He could see his own wing tip, the RAF roundel crisp against the gray.

He rolled left, gentle at first, then more aggressively.

Usually, a hard turn like this would fog the glass instantly. Blood pressure up, breathing up, moisture up.

The fog didn’t come.

All he got was a slight increase in the whisper of air, the draft brushing his shoulder, running up the inside of the canopy and out somewhere behind him.

He keyed the radio.

“Tower, Cartwright,” he said. “Level at two-zero, conducting maneuvers.”

“Roger, Cartwright,” came the clipped reply. “Report any abnormalities.”

Abnormalities.

He almost laughed.

The most abnormal thing in his cockpit right then was that he could see.

He gave the aircraft a workout.

Loops, barrel rolls, high-G turns, simulated interceptions, diving chases and snapping climbs, pushing his own breathing hard on purpose. He wanted to flood the cockpit with as much moisture as he could.

The canopy never fogged beyond a faint suggestion that cleared as fast as it formed.

Forty minutes later, he brought her back.

Holloway saw the landing lights wink on, felt the buzz in his bones as the Spitfire curved back toward the field, wheels dropping, flaps lowering.

She touched down, bounced once, then settled, rolling to a stop near the dispersal.

The canopy slid back.

Cartwright pulled off his helmet.

His hair was damp from sweat, his face reddened from the climb, but not frost-bitten.

Holloway climbed the ladder two rungs and looked in.

“Well?” he asked.

“It worked,” Cartwright said, simply.

He said it with the weight of a man who did not exaggerate.

Holloway let himself breathe fully for what felt like the first time in an hour.

Quiet Revolution

The next few days were measured in flights, not hours.

Cartwright flew again—in cloud this time, where cold and moisture should have conspired to make a mockery of any idea.

He came back with the same report: clear.

Then two more pilots flew the modified Spitfire.

Then three.

They were handpicked: men who had experienced the fogging firsthand and who had lost friends to it.

Each one returned with variations of the same story.

A faint cold draft.

A bit more noise near the shoulder.

And clear glass.

It wasn’t perfect; some times required a bit of glove wipe or a head tilt. Nothing is perfect in war.

But the days of the canopy turning into a white wall the second breathing spiked were gone in that machine.

Word spread through the mess like a rumor of extra leave.

“Cartwright, that your crate with the magic wind?”

“Heard you can breathe like a horse and still see.”

“What’d Holloway do, install a Merlin under your seat?”

The laughter was still there, but now it was tinged with curiosity, not dismissal.

Pilots started asking discreetly in the hangar which aircraft had “the gap.” Ground crew winked and obliged where they could.

Holloway modified three more Spitfires under cover of other repairs.

Aileron cable replacement.

Hydraulic leak fix.

Refitting gun mountings.

In the margin, always that quiet, unauthorized cut and the screw of the deflector.

It felt like smuggling.

Like forging passes, but for airflow.

He kept records. Temperatures, altitudes, pilot reports. He built his case the way he’d built his machines: methodical, careful, with no extra weight.

Then reality caught up.

One afternoon, the squadron engineer officer—Flight Lieutenant Briggs, a thin man with thick glasses and a permanent worry line between his brows—came to him with a piece of paper in one hand and a stripped screw in the other.

“What have you been doing to my aircraft, Holloway?” he asked.

Holloway looked at the screw.

“Looks like you’ve been over-torquing your screws,” he said.

Briggs didn’t smile.

“I’m talking about this,” he said, holding out the paper.

It was a maintenance log with notations in Briggs’s neat hand but with a late addition in pencil.

Canopy rail modification? — see Holloway.

“Pilot says his kite flies different,” Briggs said. “Says he can see. Says you’re a magician. I inspected the canopy. There’s a gap.”

Holloway took off his cap, ran a hand through his hair, considered lying, decided against it.

“Field modification to address fogging,” he said. “Tested. Working.”

Briggs’s eyes widened.

“Unauthorized,” he said.

“Yes,” Holloway said.

“You know the regs.”

“Yes,” Holloway repeated.

Briggs pinched the bridge of his nose.

“Bloody hell, Peter,” he said. “You can’t just hack into a Spitfire. If this goes south, they’ll string you up.”

“If this goes south, pilots die,” Holloway said. “They’re already dying. This stops it.”

Briggs looked at him for a long moment.

“What’s your data?” he asked.

Holloway handed him a slim notebook from his pocket.

“I knew you’d find out sooner or later,” he said. “There. Flights. Conditions. Results.”

Briggs flipped through, his engineer’s mind tallying numbers, cross-checking altitudes, turning anecdotes into patterns.

Ten flights.

Zero fogging incidents severe enough to blind.

One report of a cold left ear.

Briggs exhaled slowly.

“I have to report this,” he said. “If I don’t, and someone else finds out, it’s both our careers.”

“I know,” Holloway said.

Briggs held up a finger.

“I also outrank you,” he said. “Which means I can choose when to report. You have forty-eight hours to bring this upstairs yourself. Make it your idea. Your solution. If you don’t, I will. After that, it’s out of my hands.”

He handed the notebook back.

“Good luck,” he said, and walked away.

The Showdown

Forty-eight hours.

That was the window between quiet revolution and official condemnation.

Holloway went back to the small room beside the hangar that served as his office and workshop. He placed his hands on the scarred wooden desk, the one dented by years of dropped tools and slammed reports, and took a breath.

Prove it.

He stayed up most of the night drafting.

He’d never been fond of paperwork.

He’d seen too many good men buried under it.

But he knew how to frame a problem.

He wrote what he knew.

Not in the dense language of committees and memoranda, but plainly.

Fogging incidents. Numbers. Times. Altitudes. Collisions. Near misses. Pilot injuries. Cold injuries from open canopy mitigation.

He described the current “solution”: cracking the canopy, the effects it had on pilot performance.

He drew diagrams of airflow inside the cockpit as it existed—a stagnation bubble forming near the canopy, moisture condensing—and as he proposed it with his modification—a laminar flow sheath across the canopy interior.

He was careful to note that structural members weren’t compromised.

He included pilot testimony, transcribed from notes: Cartwright, McKay, two others.

He described the modification installation process: one hour per aircraft, no special tools, minimal material cost.

He didn’t apologize for having gone ahead.

He didn’t make excuses.

He simply laid out problem, intervention, result.

He submitted the report to his station commander the next morning.

By afternoon, he was summoned.

The CO’s office looked like every CO’s office Holloway had ever seen. A big desk, maps on the walls, chairs that were just comfortable enough to sit in but not lounge in.

Today there were three people waiting inside.

The CO.

A man in civilian clothes with an RAE badge on his lapel.

And a wing commander with Fighter Command tabs on his shoulders.

The air was thick with tobacco and significance.

“Holloway,” the CO said. “Sit down.”

Holloway did, back straight.

“This is Mr. Nichols from Farnborough,” the CO said. “And Wing Commander Foster from HQ. They’ve had a look at your… proposal.”

Nichols, the engineer, held the report loosely like it was a bird that might peck him.

“Unauthorized field modification to a critical airframe component,” he said, his tone somewhere between admiration and disapproval. “You’ve got brass, Warrant Officer.”

“Brass doesn’t clear fog,” Holloway said before he could stop himself.

Foster coughed into his hand, hiding a smile.

“We’ve heard from your pilots,” he said. “Cartwright, McKay. They’re very keen on your ‘Holloway gap.’”

“Their words,” Nichols added dryly. “Not ours.”

He set the report down.

“Explain to me, in non-textbook terms, why this works,” Nichols said.

Holloway took a breath.

“Canopy fogging isn’t just about temperature,” he said. “It’s about air that doesn’t move. Warm, moist air from the pilot’s lungs rises until it hits the cold Perspex. If it hangs there, motionless, it saturates. Once it saturates, it condenses on the glass. Our current design seals the cockpit so tight there’s nowhere for that moisture to go. It just sits there, condensing.”

He tapped the diagram with his finger.

“What we need isn’t more heat,” he said. “More heat just increases capacity and then we’re back where we started. What we need is flow. A thin, fast-moving layer of air across the inside of the canopy that strips the moisture away before it can condense. The gap uses the slipstream, which we’ve got in abundance, to create that flow without adding weight, fans, or heaters.”

“And the cold?” Foster asked. “We’ve been cracking canopies open all winter. That’s a brute-force solution but it works, except when it freezes the pilots half to death. How does your gap compare?”

Holloway pulled a sheet from his folder.

“Average cockpit temperature drop with full canopy crack: fifteen to twenty degrees Fahrenheit,” he said. “With the gap: four. Pilots report a localized draft, not an arctic gale. They can still feel their fingers when they land.”

Nichols leaned forward.

“And structural integrity?” he asked. “You’ve cut into the rail. You certain you haven’t introduced stress concentrations? Micro cracks? Things that won’t show up until someone pulls six G in a dive and the whole thing lets go?”

“I cut into the rail, not the loadbearing frame,” Holloway said. “The stress is carried through these members and the mounting points. The rail itself is more like a track. I’ve tested the modified canopy at ground on torsion and load. It flexes within normal limits. No crack propagation.”

Nichols’s gaze flicked up.

“You’ve read fluid dynamics,” he said.

“Yes,” Holloway admitted.

“On your own time.”

“Yes.”

Nichols rubbed his chin.

“You’re not supposed to be clever,” he muttered. “You’re supposed to be obedient.”

That got a small laugh from Foster.

“We’ve lost nineteen pilots in my group to fogging-related incidents,” the wing commander said quietly. “That’s just in the last three months. I’ve written letters to wives, to mothers, to girls whose names I shouldn’t know. I’ve visited wrecks where the wings are whole and the nose is buried in a hillside. No flak, no bullets. Just impact. If this makes even a fraction of a dent in that, I’m inclined to lean toward clever over obedient.”

Nichols leaned back, looking at Holloway with something like respect now, or at least professional curiosity.

“You went about this backwards,” he said. “You cut first, then asked. But damn me if the numbers aren’t promising.”

The CO cleared his throat.

“Farnborough wants to test it formally,” he said. “Ten aircraft. Two squadrons. Controlled implementation. If the initial results hold up, they’ll recommend wider adoption.”

Holloway nodded.

“It’ll work,” he said.

“If it doesn’t,” Nichols said, “you’ll be the most famous court-martial in the engineering corps in a decade.”

Foster smiled, thin and fierce.

“If it does,” he said, “we’ll be fitting the Holloway gap on every Spitfire from here to Malta, and Jerry can take his fogging tactics and shove them up his… Alps.”

Stopping a Tactic Cold

Pilots talk.

The test wasn’t as controlled as Nichols might have liked.

Word spread faster than official memos ever could.

Within weeks, there were twenty modified Spitfires flying in active squadrons.

Then fifty.

Then hundreds.

At first, only a handful of sketches and a rough instruction sheet made their way from Tangmere to other stations, smuggled in envelopes, tucked into toolboxes.

“Cut here. Quarter inch. Smooth edges. Fit deflector at thirty degrees.”

Pretty soon, it was in official channels, too.

A typed directive from Fighter Command, stamped and initialed, instructing forward maintenance units to implement “cockpit airflow management modification per attached diagrams” on all Spitfire Mk V and IX airframes as soon as practical.

In some places, it was still mocked.

“Another damn mod,” one old crew chief grumbled as he filed yet another slit into a canopy rail. “Pretty soon there’ll be more holes than Spitfire.”

But the numbers spoke.

Between April and December 1943, incidents of severe canopy fogging reported in Combat Reports dropped by more than forty percent compared to the previous winter.

Spatial disorientation logs went down.

Mid-air collisions in cloud went down.

Cold injury rates from full canopy cracking plummeted.

That was just in the numbers that got written down and sent up.

The things that never made it into reports were harder to measure.

The moment a pilot rolled his Spitfire into cloud on bomber escort and, for the first time in months, didn’t feel terror when the world went white outside, because the world didn’t.

The first evening a flight of fighters came back from a messy intercept in bad weather with all aircraft accounted for, and the squadron adjutant realized he wouldn’t be drafting condolence letters that night.

The way German pilots noticed, grudgingly.

Reports started turning up in captured Luftwaffe documents months later. English fighters maintaining visual contact “with unexpected persistence” in poor conditions. The tactic of baiting them into blind climbs “less effective than in previous winter.”

They didn’t know why.

They chalked it up to better training, better discipline, improved instruments.

Nobody briefed them on a quarter-inch strip of nothing cut into the base of a canopy hundreds of miles away and dozens of decisions ago.

At Tangmere, pilots stopped swinging their canopies open at altitude unless they absolutely had to.

They still got frostbite sometimes. War is indifferent to incremental engineering improvements.

But not from routine contact with twenty-below gale inside their office.

They still died sometimes, too.

Fog was only one killer in a sky full of them.

But one killer had been pushed back.

And that mattered.

After

The war moved on, as wars do.

Spitfires got replaced by newer marks.

Then by jets.

Holloway was promoted to squadron leader, then shuffled sideways into technical liaison roles as the RAF discovered he was more useful solving problems than saluting.

He traveled between stations, his hands touching Hurricanes and Typhoons and Mustangs, listening to the gripes of ground crews and translating them into solutions where he could.

He never liked London.

Too many bars on windows, not enough oil on the air.

After the war, he went home to Coventry.

He took a job designing ventilation systems for factories.

The problem, in essence, was the same.

Get stale air out.

Get fresh air in.

Manage temperature and flow without making people miserable.

He married. He had a family. He didn’t talk much about the war.

If someone asked what he did, he said, “I kept airplanes in the air.”

If someone pushed, he might mention the canopy thing, but always with a shrug, as if it had been obvious.

“Any fool could’ve done it,” he’d say. “I just got there first.”

Pilots from Tangmere and other fields didn’t see it that way.

They held reunions.

They drank to absent friends.

They told stories about Merlin engines and ground loops and the night Jerry came over in force and the flak looked like fireworks.

Sometimes, after the third pint, someone would mention the winter of ’43.

“Remember when you couldn’t see past your own bloody nose if you breathed too hard?” someone would say.

Another would snort.

“I remember thinking I’d die in a snow globe,” he’d say.

They’d talk about the open canopies, the cold that made their bones hurt.

And then about the little gap that changed everything.

“The Holloway slit,” some called it.

“The fix,” others said.

Even years later, none of them could quite believe that Command hadn’t come up with it first.

They’d wonder what else could’ve been solved if someone had let the men in the hangars tinker a bit more.

At one reunion in the late sixties, held at a modest hotel not far from Tangmere’s old runways, a group of surviving pilots insisted that Holloway attend.

He showed up a little late, uncomfortable in his suit, fussing with a tie that felt like a noose after years of overalls and flight line jackets.

He sat in the back, content to listen.

At the end of the evening, one of the old squadron leaders—gray-haired now, thickening around the middle in that universal way—stood and tapped his glass with a fork.

All heads turned.

“I’d like to propose a toast,” he said. “To the ground crews. To the riggers. To the men who kept the kites flying.”

Glasses raised.

“And one in particular,” the man continued. “To Peter Holloway, who had the bloody nerve to cut a hole in a Spitfire and tell the Air Ministry they’d been doing it wrong.”

There was laughter.

There was applause.

Holloway tried to wave it off.

He stood just enough to be seen, nodded once, and sat back down.

Later, someone asked him what it had been like, breaking rules in wartime.

He looked at them, an old man now, eyes still sharp behind the lines.

“There are rules to keep people safe,” he said. “And rules to keep people comfortable. You don’t break the first. You ignore the second when they get in the way of the first.”

He sipped his beer.

“Besides,” he added, “it wasn’t my idea they cracked the canopy in the first place. Mine just made it smaller.”

The story of the Holloway gap ended up in textbooks.

Not in the main chapters.

In sidebars.

Case studies.

“Field modification addressing environmental control under combat conditions,” they called it.

Elegant.

Simple.

Effective.

The kind of solution engineering professors pointed to when they told their students that sometimes the answer isn’t a new material or a bigger budget.

It’s listening to the people who are suffering and trusting that the man with oil on his hands might see something the man behind the desk does not.

When Peter died in 1979, his obituary in the local paper mentioned his war service in a sentence between notes about his family and his work in ventilation.

It didn’t mention Spitfires.

It didn’t mention fog or cloud or German tactics blunted.

But somewhere, in a file in an air ministry archive, a memo still sits.

It’s one page, stamped and initialed, dated May 1943.

It recommends that Warrant Officer Peter Holloway be commended “for initiative and technical ingenuity in addressing a critical operational hazard by means of simple and effective modification.”

Below that, in a smaller hand, someone has penciled in a line.

He saw what we did not.

They mocked his canopy-cracked cockpit idea.

They laughed at the notion of intentionally cutting a gap into the sleek line of a Spitfire.

Then they flew behind a sheet of clear glass in a winter sky while the men who hadn’t listened coughed on condensation and froze.

You don’t always know in the moment which ideas will matter.

You don’t always know which rules are worth breaking.

Sometimes, you only know that something is killing people who don’t deserve to die.

And that physics, unlike bureaucracy, can be persuaded with a quarter-inch of nothing in exactly the right place.

THE END

News

Sister Mocked My “Small Investment” Until Her Company’s Stock Crashed

If there’s one thing I learned growing up Morrison, it’s this: Thanksgiving at my parents’ estate was never about…

My Grandson Called Me From The Police Station Saying “Coach Webb Beat Me… But They Think I Att…”

In thirty-eight years as an educator, I learned that phone calls after midnight never bring good news. Parents don’t…

IN COURT, MY SON POINTED AT ME AND YELLED, “THIS OLD WOMAN JUST WASTES WHAT SHE NEVER EARNED”

If you had told me that one day my own child would stand up in a courtroom, point at…

How an 11-Second Signal From a Farm Girl Prevented 38,412 Deaths in a Valley Built to Kill

At 05:46 in the morning, under a low ceiling of fog rolling across the French bocage, an entire Allied…

My Fiancée’s Dad Called Me “Trash” at Dinner—Then Begged Me Not to Cancel the Merger…

The champagne flute hit the marble floor like a gunshot. Crystal shattered, Dom Pérignon arced in a slow-motion spray…

My Wedding Planner Stole My Dream Wedding For My Fiancé’s Ex… I Had My Plans Too

Six weeks before my wedding, my phone lit up with Madison’s name. I was standing in the kitchen, half-listening…

End of content

No more pages to load