December 16, 1944

Ardennes Forest, Belgium

0530 hours

Snow fell like it was being poured out of the sky in slow motion—thick, heavy curtains that blurred the line between ground and heaven. The dark shapes of fir trees loomed like bones in a ghost’s rib cage. Somewhere in those trees, the German army was supposed to be finished.

That’s what they’d told the boys of the 106th Infantry Division, anyway.

“Quiet sector,” the briefing officers had said. “Good place to break in the new units. Germans are on their last legs. You’ll mostly be holding the line.”

Now the line was being blown off the map.

At 5:30 a.m., the forest didn’t just wake up—it detonated.

Artillery roared from the east like a thousand doors slamming shut at once. Shells screamed overhead and plunged into the American positions, ripping up snow and dirt and men. The ground heaved. Trees shattered, showering splinters and branches and steel.

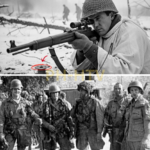

In a shallow foxhole dug into frozen earth, Private Joe Malloy flinched and curled tighter around his M1 Garand. He was nineteen, from Ohio, and the army had told him this rifle was the greatest battle implement ever devised.

Right now it just felt like eight rounds of borrowed time.

“Jesus,” he muttered as another shell hit nearby, showering him with snow. “They said the Krauts were done.”

His foxhole buddy, a lanky kid from Kansas, spat into the snow. “Yeah, well, the Krauts didn’t get that memo.”

Machine-gun fire jabbered out in the distance, sharp and fast. Somewhere to Malloy’s right, a man was screaming. He tried not to hear it.

Then the German infantry came.

They emerged from the trees like shadows made solid—men in white smocks over field gray, moving in small groups, rifles and MP40 submachine guns held low. Above the din of artillery, the higher, harsher note of automatic weapons carved the air.

Malloy raised his M1 over the lip of the foxhole and fired. The rifle kicked into his shoulder, that familiar steady shove. A German in a white smock dropped, snow puffing up around his body. Malloy swung the muzzle, fired again, and again. Men fell. Men kept coming.

He fired his seventh round and knew, somewhere under the pounding of his heart, that he had one shot left.

He didn’t have time to count carefully, not really. No one did. They were supposed to. The manuals said so. But manuals didn’t factor in artillery shaking your teeth or the way a man’s brain turned to static when he could see the whites of an enemy’s eyes.

Malloy pulled the trigger again.

The eighth round went, the bolt locked back with a metallic clang, and the empty en-bloc clip sprang free with that bright, unmistakable ping.

The sound cut through the chaos like a bell in a quiet church.

Twenty yards away, a German sergeant heard it and grinned. He’d been fighting long enough to recognize that music. That little note meant an American was holding a long, heavy chunk of nothing.

“Vorwärts!” he shouted, and surged forward, dragging three men with him.

Malloy ducked, fumbling at the bandoleer that crossed his chest, fingers numbed by cold and fear. The manual’s neat diagrams of “proper reload procedure” seemed like something from another planet now.

Empty clip ejects. Right hand retrieves full clip. Insert from above. Thumbs clear. Bolt forward.

Nice and easy. In a classroom.

In a frozen hole with a German sprinting toward you, it was like trying to thread a needle in an earthquake.

He got the clip in his hand, his fingers slipping on the cold metal. His head was below the lip of the foxhole; he couldn’t see anything. He could feel the rifle, open and empty, hanging on his sling.

Four seconds, they’d told him in training. That’s how long a reload takes in combat.

Four seconds was enough time for a German soldier to cover twenty feet. Enough time for three aimed rifle shots. Enough time for a man’s life to blink out.

Somewhere down the line, another M1 pinged empty. Somewhere else, a German squad surged at the sound.

The people who wrote the manuals had never stood where Malloy was standing.

They had never felt that tiny sound turn into a death sentence.

What the brass in their warm offices did not know, what no one in Supreme Headquarters quite understood, was that an answer to that sound had already been found.

Not in a laboratory. Not on a test range.

In the mud of Italy, by a man who by all rights had no business changing anything.

A textile worker from Pennsylvania who held his rifle wrong.

The Boy Who Fixed Things Nobody Asked Him To

David Marshall had been born into noise.

The noise of machines in the textile mill. The noise of coal carts rattling along tracks. The noise of arguments muffled through thin apartment walls.

He came into the world on a raw November night in 1919, in a two-room house on the edge of a company town in western Pennsylvania. His father, Tom Marshall, was a coal miner who had lost three fingers in a machinery accident. His mother worked nights cleaning offices.

They were poor, but so was everyone they knew. Poverty was the water they swam in.

The hills around town were thick with trees and game. As soon as he was old enough to hold a .22 rifle, David was sent out into those hills.

“Don’t miss,” his father would say, adjusting the boy’s grip with his blunt-fingered hand. “Every bullet you waste is meat we don’t eat.”

So David learned not to miss.

He learned to hit squirrels high in the shoulder so they wouldn’t tear themselves apart when they fell. He learned to move quietly, to feel the way the wind shifted. He learned to strip the rifle down and clean it without anyone telling him how.

When he wasn’t in the hills, he was in the mill.

At fourteen, he dropped out of school after eighth grade to work full-time. He stood by the looms for ten, twelve hours a day, watching the complicated dance of threads and hooks and metal fingers. At first the motion overwhelmed him. So many moving parts. So much that could go wrong.

Then he began to see patterns.

He could tell, from the way one arm stuttered or one thread just barely quivered, which machine was about to jam. He could hear a change in pitch and know exactly which belt needed tightening.

His foreman, a sour-faced man named Kline, complained that David was always messing with the machines.

“You’re not an engineer,” Kline snapped once, catching him adjusting a tension arm with a screwdriver. “You’re here to feed thread. You get me?”

“Yes, sir,” David said.

He went on listening to the machines anyway.

“Boy fixes things nobody asked him to fix,” one of the older workers said once, half amused and half annoyed, when a loom that should have died kept running because David had fished a bit of wire out of the gears before it snapped.

The habit stuck.

He fixed leaky pipes with rubber scraps. He fixed broken chairs with carriage bolts. He fixed the radio at home by stripping it down on the kitchen table and staring at its guts until they made sense.

He wasn’t a genius. He didn’t think of himself that way. He just couldn’t stand seeing something almost work.

When the war came, it came first as rumors.

Hitler had taken this, bombed that. The Japanese were pushing here, there.

Then it came as a summons.

He enlisted in 1941, before Pearl Harbor, more out of restlessness than patriotism. The mill would keep running without him. The hills would still be there when he got back.

The army, on paper, saw nothing special.

Service record:

Education: completed eighth grade.

Civilian occupation: textile worker.

Marksmanship: acceptable.

Special skills: none noted.

He was assigned as a replacement rifleman to the 36th Infantry Division, the “Texas Division,” full of boys with drawls and cowboy stories. A Pennsylvania coal-town kid with a flat, quiet voice didn’t stand out much.

He didn’t mind. He didn’t want to stand out.

He wanted to listen.

So he did.

He listened to the way sergeants yelled. He listened to the way officers briefed. He listened to the way guns sounded when they worked and when they didn’t.

Then the army handed him an M1 Garand.

A Masterpiece With a Flaw

The first time he fired the M1 on the range at Camp Edwards, the rifle kicked his shoulder and made him grin despite himself.

Eight rounds. Semi-automatic. No bolt to work. Just aim-squeeze, aim-squeeze, aim-squeeze.

The instructors were proud of it.

“This is what makes you better than the Krauts,” one staff sergeant barked, pacing in front of the line. “They got their bolt guns. You got this. Greatest battle implement ever devised.”

The sergeant pointed at a chart.

“Rate of fire for a trained rifleman with a bolt action? Fifteen rounds per minute, maybe. You?” He thumped the M1. “Forty to fifty aimed rounds per minute. You put more lead in the air, faster, with more hits. That’s how you win. Now—reload drills. Eyes on me.”

The reload was simple. Elegant, in its way.

Fire eight shots. Bolt locks back. Clip flies out with a neat little ping.

Tilt rifle back, reach into bandoleer, pull out a fresh eight-round en-bloc clip, thumb it down into the open receiver until it clicks. Move thumb clear, let the bolt slam forward, chambering the first round.

All one fluid motion. On the range, with no one shooting back, the men learned to do it in about two and a half seconds.

“Count your shots,” the sergeant said. “Reload during lulls. Don’t get caught with an empty rifle. Questions?”

No one had questions.

They took the manuals at their word.

David watched that clip system and thought about his father’s old bolt-action .30-30 back home, the way you could drop rounds into the top one at a time any time you wanted. He thought about the looms, about how a system that worked perfectly in a clean, controlled environment could choke itself to death when a little dust or grit got in.

He thought, but he kept his mouth shut.

He was a private with an eighth-grade education. Weapons engineers in Springfield had designed this thing. Boards and colonels had signed off. Who was he to question?

Then Salerno happened.

The Wall in Italy

September 1943. Salerno, Italy.

The air smelled like cordite, dust, and the sea.

The landing had been a mess. The German defenses were stronger than intel had promised. Tanks had rolled close enough to see the expressions on the faces of men clinging to their armor. Mortars had turned olive groves into slaughterhouses.

David Marshall, now a buck sergeant after a few months of showing he knew how to keep his head when others lost theirs, found himself pinned behind a low stone wall.

The wall ran along the edge of a little vineyard. Before the war, someone had probably leaned there on quiet evenings, sipping wine and watching the sun go down. Now, it was pocked with bullet scars and splashed with dirt.

German machine-gun fire raked the field beyond, sowing dust and bits of vine. Every time David raised his head above the wall, the air snapped and hissed around his helmet.

He’d already been there too long. Ammunition was low. Men on his left had fallen back or fallen flat. On his right, he could hear someone moaning.

He fired, felt the rifle recoil, saw a tan uniform crumple near a broken tree.

He fired again. Again. Seven shots. Eight.

That last pull of the trigger brought the familiar empty click, the bolt locked back, and then the metallic ping of the clip ejecting.

He flinched as a bullet smacked into the wall inches from his fingers.

Standard doctrine said he should drop below cover, hold the rifle at waist level, and reload with his right hand.

But the wall was too low.

If he dropped down, the bulk of the rifle rose above the stone. If he stood, his head rose with it.

Either way, he was going to give that German machine-gunner a perfect little silhouette to chew on.

His brain, in that stretched-out second, ran through options like a machine checking circuits.

He could risk it, pop up, reload fast, hope the gunner was looking elsewhere.

He could hunker down and pray someone else put fire on that nest.

He could, theoretically, throw the rifle and run.

He didn’t like any of those choices.

His eyes went to his hands, to the rifle, to the way gravity pulled at it.

A thought hit him—stupid, wrong, backwards.

But backwards was sometimes how you fixed a jammed loom. Sometimes you had to run it in reverse before it would run forward again.

He took a breath and moved.

He flipped the rifle upside down.

Instead of keeping his right hand on the stock and reaching with his left for a new clip—the approved motion—he did the opposite.

His left hand dove into the bandoleer, fingers closing around the familiar ridged rectangle of an eight-round clip. His right hand held the rifle by the fore-end, rolling it so the open receiver was below, facing the ground.

The German machine gun hammered, bullets tracing along the top of the wall, chewing stone and dirt. Chips flew, stinging his face.

David shoved the clip up into the receiver from below.

His thumb guided it in. His fingers stayed clear of the bolt’s hungry teeth.

The clip clicked into place. He snapped his hand free.

He let the rifle rotate back, feeling the weight shift. In the same motion, he brought it back up, stock to shoulder, as the bolt slammed forward with a satisfying metallic snarl.

He felt, rather than saw, the astonishment in his own body.

He’d just reloaded in what felt like the length of a heartbeat.

He raised the sights over the wall and fired.

A German helmet jerked back in the distance. The machine gun stuttered, stopped.

He ducked again, chest heaving.

“Jesus, Sarge!” someone yelled from a few yards down the wall. “How’d you—”

“Reload!” David barked automatically. “They ain’t done yet!”

Later, when the fight moved on and the vineyard fell behind them, when they were eating lukewarm rations in a ditch, he tried to reconstruct what he’d done.

He took an empty rifle and an empty clip and worked through the motion slowly, feeling it.

Left hand clip, inserted from below. Rifle upside down. Right hand holding the front, guiding the whole thing. Thumb pushing the clip up. Fingers safe. Rotate back. Fire.

It felt wrong.

The training sergeants would have yelled themselves hoarse if they saw it.

But it had worked.

Under fire. Under panic.

He timed it mentally. Then he pulled aside a private and asked him to count.

He went through the motions as fast as he could.

“Time,” the private said.

“How long?” David asked.

“’Bout… one,” the private said, brow furrowing. “One and a half? That seemed…fast, Sarge.”

Standard reload, the manuals said: 2.5 seconds in ideal conditions. Longer under stress.

His backwards reload had come in under two. Under one and a half, if he trusted the kid’s stammered count.

He did it again. Again.

Each time, it felt smoother.

Something inside him clicked into place along with the clip.

He had just broken the machine and made it run smoother.

Fixing What No One Asked Him To Fix

For a while, he kept it to himself.

In a war where any minute someone could be blown apart or shot through the throat, it felt almost arrogant to say, I found a better way to hold my rifle.

But he couldn’t shake the feeling that this wasn’t just a trick. It was a difference between alive and dead in fights like Salerno.

So he practiced.

Behind latrine huts. On the far side of ammo dumps. In quiet corners of rest areas where no officers looked too closely.

He scrounged dummy rounds from a friendly supply sergeant—spent brass filled with sand, bullets pinned back into the necks.

At first, his fingers fumbled. The clip slipped. The bolt tried to bite his thumb.

He cursed softly, adjusted, tried again.

The textile mill had trained him for this. Repetition. Minute adjustments. Checking what worked and what didn’t.

The rifle became another machine to listen to.

Left hand retrieves the clip while the right keeps the rifle aimed roughly downrange. Rotate counterclockwise. Insert from below, letting gravity assist, not fight. Thumb presses. Fingers clear the bolt. Rotate back. Sights on target.

Hours passed that way.

On one of those evenings, while the light turned Italy’s dust gold, Private First Class Anthony Caruso came around the corner of a bombed-out farmhouse and stopped short.

“What in God’s name are you doing to that rifle?” Caruso demanded.

Caruso was broad and dark-haired, his Brooklyn accent thickened by stress and cigarettes.

“Reloading,” David said, not stopping the motion.

Caruso squinted.

“You’re gonna break it,” he said. “You’re holding it upside down.”

“Still works,” David said calmly, finishing the cycle with a clack. “Reloaded in a second and a half.”

Caruso snorted. “Bull.”

“You got a watch?” David asked.

Caruso grinned. “Now you’re speakin’ my language.”

The first time, with Caruso timing, came in at 1.4 seconds.

The second, 1.3.

Caruso stared at the cheap wristwatch like it had betrayed him.

“Do it again,” he said.

David did.

“Son of a—” Caruso shook his head. “You know how long it takes me to reload? Like, all day. I could write home in the time it takes me to stuff a new clip in.”

“Let me show you,” David said.

It took Caruso longer to learn than it had taken David to invent it, but not much. His hands were quick. He’d grown up juggling wrenches in a garage.

By the end of the week, Caruso could reload in under two seconds consistently.

He started showing off.

“Watch this,” he’d say, grinning, to some skeptical private. “Sarge here taught me how to reload wrong.”

Then he’d fire a string of blanks, ping, flip the rifle, and have it loaded again before the onlookers had finished raising their eyebrows.

Word traveled faster than orders.

Within a month, the entire squad knew the inverted reload. Within two, half the platoon. Men from other companies started drifting over, asking gruffly if the rumors about the “backwards grip” were true.

It wasn’t just speed.

David realized, watching them, that the technique also changed how a man used cover. By keeping the right hand on the stock and changing only the orientation of the rifle briefly, a soldier could stay lower, pop up less, show less of his head and shoulders.

Small advantages. Tiny fractions.

But war, he knew, was a math problem of fractions.

Not everyone was happy.

In January 1944, after one company cook mentioned the “trick reload” in front of an officer who took doctrine personally, David found himself standing at attention in front of Captain William Harris.

The captain held a paper in one hand—the report David had written up, three pages of careful diagrams and step-by-step instructions he’d submitted in naive hope that someone might make it official.

He dropped it on the table between them.

“Sergeant Marshall,” Harris said. “What you’re describing here is a fundamental violation of established reload doctrine.”

“Yes, sir,” David said. “With respect, sir, it also works.”

“That’s not the point,” Harris snapped. “The Infantry Board has studied this problem extensively. Do you think you’re the first man to wish his rifle reloaded faster? We have engineers. We have experts. If there were a better way, they’d have found it.”

David kept his eyes on a spot just over the captain’s shoulder.

“I learned it at Salerno, sir,” he said quietly. “Behind a wall that was too low. I’ve done it under fire. It works under fire.”

Harris’ jaw clenched.

“You are a textile worker,” he said. “You are not a weapons engineer. You will cease teaching this… improvisation… to anyone outside your squad. And you will not, under any circumstances, present your ideas directly to higher command again. Am I understood?”

“Yes, sir,” David said.

Three days later, the reprimand arrived in his file: Teaching unauthorized weapons handling techniques to personnel outside his immediate command.

He folded it, put it in his pack, and went back to doing what he’d been doing.

He kept teaching.

He fixed what no one had asked him to fix.

The Colonel Who Listened

The numbers didn’t lie.

By the spring of 1944, someone in some dim room with stacks of paper started to notice that one company in the 36th Division was bleeding less than it should.

After-action reports from Italy were grim reading. Hill taken. Hill lost. Casualties: heavy.

But in Company E, 2nd Battalion, a pattern emerged.

In close combat engagements—fights under fifty meters—fewer men were dying. They were being wounded at the same rate. They were in the same fights. But when things got close and ugly, that company kept a few more men alive than the numbers predicted.

The reports crossed a desk in Fifth Army headquarters.

The man behind that desk had a reputation for being a troublemaker in the best sense.

Lieutenant Colonel Robert Frederick had built the First Special Service Force—the “Devil’s Brigade”—out of Americans and Canadians who weren’t supposed to be able to do what he asked them to do. He had pushed for winter raids, parachute insertions, mountain assaults, things that made more conservative officers gnash their teeth.

He had seen too many “impossible” things done by men who hadn’t read the part of the manual that said they couldn’t.

So when he saw a statistical anomaly tied to a rumor about a sergeant who reloaded his rifle backwards, he didn’t laugh.

He sent for him.

The summons came in March 1944 near Anzio, where the front had bogged down into a deadly chess match of artillery and patrols.

“Sergeant Marshall?” a runner said, ducking into the squad’s dugout, where David was cleaning his rifle by lantern light.

“Yes?”

“Colonel Frederick wants to see you. Sir.”

That “sir” at the end wasn’t for David. It was for Frederick. You put respect into that name.

David wiped his hands on a rag and went.

The farmhouse they’d chosen as a temporary headquarters was mostly rubble from waist height up. One wall still stood. A roof beam leaned like a drunk against the sky. Inside, a table had been set up, maps weighted down with rocks.

Twelve officers stood or sat around the room, some in crisp uniforms that looked like they belonged more in Washington than in Italy. One of them, a compact man with sharp eyes, wore the silver oak leaves of a lieutenant colonel.

Frederick.

Another officer, a tall man with a narrow face and a little mustache you could have used as a straightedge, watched David enter with barely concealed disdain. He introduced himself later as Lieutenant Colonel James Patterson of the Infantry Board, but at first he was just a look.

“Sergeant Marshall reporting, sir,” David said, snapping to attention.

“At ease,” Frederick said. His voice was calm, almost conversational. “I appreciate you coming, Sergeant. I know you’ve got better things to do than humor a bunch of staff officers.”

A few of the men in the room bristled at that. Frederick ignored them.

“I’ve heard interesting things about how you handle that rifle,” he said. “I’d like to see it.”

He held up a stopwatch, one of those big, round ones with a thumb button on top. Its face gleamed in the dusty light.

“This is completely informal,” he went on. “No boards. No committees. Just you, your rifle, and some skeptical old men.”

The skeptical old men shifted again.

Patterson cleared his throat. “Colonel Frederick, the Board has already—”

“The Board,” Frederick said, “isn’t currently pinned down under German fire. My men are. Humor me, James.”

Patterson subsided, lips tight.

David swallowed.

“Yes, sir,” he said.

They handed him a standard M1, cleaned and ready, with clips loaded.

“You’re going to fire eight rounds into that sandbag wall,” Frederick said, nodding toward one end of the room where they’d stacked some bags. “Reload using whatever technique you’ve been teaching. Fire again. We’ll time from the empty shot to the first shot of the next clip. Understood?”

“Yes, sir.”

Frederick nodded. “Whenever you’re ready.”

David shouldered the rifle. The familiar weight settled into his hands like an old tool.

He sighted on a patch of stained burlap.

He exhaled. Fired.

The rifle barked, the sound echoing strangely in the ruined farmhouse. Dust sifted from the rafters.

Two. Three. Four. Five. Six. Seven.

The eighth shot cracked. The bolt locked back. The clip pinged.

Frederick’s thumb hit the stopwatch button.

David’s hands moved.

Left hand to bandoleer—clip. Right hand steadying the rifle, rotating it. Clip inserted from below. Thumb pressed. Click. Rotate back. Bolt forward.

He drove the stock back into his shoulder and fired.

Frederick clicked the stopwatch again.

The room was very quiet.

“Time?” Patterson demanded.

Frederick looked at the face of the watch. Then he looked around at the officers.

“1.3 seconds,” he said.

“That’s not possible,” Patterson snapped. “He must have—there has to be some… trick.”

“I like tricks that keep my men alive, James,” Frederick said mildly. “Do it again, Sergeant.”

They did it again.

This time, David didn’t bother counting his shots. He let his body do the work.

Ping. Empty. Flip. Insert. Rotate. Fire.

“1.4,” Frederick said. “Still significantly faster than the standard.”

Patterson stood up.

“This is a parlor trick,” he insisted. “Under actual combat conditions—”

“I’ve done it under actual combat conditions, sir,” David said quietly, surprising himself by interrupting. “Behind a wall at Salerno with an MG-42 sweeping over my head. I’ve done it in mud and rain. I’ve taught it to my squad. They’ve used it. It works.”

Patterson flushed.

“You’re asking soldiers to violate established doctrine,” he said, turning back to Frederick. “To release their firing hand, to reverse their grip, to—”

“I’m asking them to live longer,” Frederick said. “And I’m asking you to look at the watch.”

He tapped it with one finger.

“Numbers don’t care about doctrine.”

He turned to David.

“Sergeant, I’m authorizing you to train a pilot group of fifty soldiers in this technique,” he said. “We’ll match them with fifty using standard doctrine. Sixty days. We’ll track engagements, casualties, reload times. That enough for your Board, James?”

Patterson’s jaw worked. “It’s highly irregular,” he muttered.

“So is war,” Frederick said. “But it keeps showing up anyway.”

He held out his hand.

“Thank you, Sergeant,” he said. “Whatever the Board decides, I appreciate a man who tries to fix what’s killing us.”

David shook his hand, the motion automatic.

He walked out of the farmhouse feeling like he’d just stepped into a machine much larger than any loom he’d ever seen.

The Numbers

They called it a trial.

To the fifty men David trained over the next few weeks, it felt like a lifeline.

They were drawn from three companies. Some were fresh replacements. Others were veterans with that particular look in their eyes that came from having lived too long on borrowed time.

He showed them the inverted grip in bombed-out courtyards, in olive groves, in empty houses with broken roofs. He corrected their thumbs. He rapped their knuckles when they let the bolt bite them.

“Keep your fingers clear,” he said. “Bolt’s like a mean dog. You stick your hand where it doesn’t belong, it’ll take a piece.”

He made them do it until their hands did it without thinking.

“Again,” he’d say, as dust and sweat streaked their faces. “Again. Faster. But clean. No fumbling. You fumble under fire, you die.”

At the same time, another fifty soldiers in other companies kept using the standard reload. They drilled the way the manuals said. They practiced timing their reloads between volleys.

The war did the rest.

For sixty days, the two groups went into the same kind of fights.

Patrols in ravines. House-to-house in cracked Italian villages. Hill assaults where the enemy was so close you could smell their cigarettes.

Some came back. Some didn’t.

Behind the lines, staff officers tracked everything they could.

How long did each soldier spend reloading in recorded engagements? When did they get hit? Were they empty when they died? Were they moving? Were they firing?

At the end of the trial, Frederick called another meeting in another ruined building.

Patterson was there, thin lips pressed together, papers in hand.

“The trial group,” Patterson began, “consisting of fifty soldiers trained in the Marshall method, participated in twenty-three documented close combat engagements. They suffered four killed in action and eleven wounded.”

He looked up, expression unwillingly sober.

“The control group—fifty soldiers using standard doctrine—participated in twenty-one close combat engagements. They suffered eleven killed in action and nineteen wounded.”

He cleared his throat.

“In situations where soldiers were caught in the open while reloading, the control group lost seven men killed,” he said. “The Marshall group lost one.”

Frederick nodded slowly, like a man watching an engine come online just the way he’d hoped.

“So, if my math’s right,” he said, “we’re talking about reducing close combat fatalities by more than half.”

“Approximately sixty-three percent, sir,” an analyst said from the back of the room, pushing his glasses up.

Frederick turned to Patterson.

“Well?”

Patterson hesitated. The weight of the numbers pressed down even on his well-insulated doctrine.

“The technique… appears to have merit,” he said stiffly. “I… recommend further study. Broader trials. The Board will need to—”

“The Board will do what it always does,” Frederick said dryly. “Study until the war’s almost over. I’ve got men in harm’s way now.”

He looked at David.

“You’ll keep teaching,” he said. “Officially, unofficially, I don’t care. I’ll start pushing this up the chain. Let’s see how far common sense can travel before bureaucracy shoots it down.”

He turned back to Patterson.

“You may tell your experts,” he said, “that a textile worker from Pennsylvania just embarrassed the hell out of them.”

Fifteen Men on a Hill

August 4, 1944

Near Fiesole, on the Gothic Line

The olive groves climbed the hillside in crooked terraces, low stone walls holding back dirt and thin trees that had seen centuries of peace before this war turned them into cover.

The Gothic Line was supposed to be the Germans’ last great defensive stand in Italy. They had dug in hard—machine-gun nests buried in hillsides, interlocking fields of fire, mortars zeroed in on every likely approach.

Marshall’s squad was part of a company tasked with taking one section of that line.

“You’ve seen worse,” their lieutenant said, kneeling in the dust, pointing at the map. “We hit fast, we hit hard, we keep moving. German infantry, maybe a couple of MGs. No armor. We can do this.”

They’d all seen worse.

That didn’t mean the knot in David’s stomach was any smaller.

They moved up through the olive groves just before dawn.

The air smelled of dust and sap. The trees cast long shadows. Their boots scuffed gravel and old leaves.

Halfway up the slope, the world exploded.

Machine-gun fire laced the air from the terraces above, tracers glowing briefly in the dim light. Bullets snapped into tree trunks, sending splinters flying.

“Cover!” someone yelled, as if there was any to be had.

David dove behind the knee-high wall of a terrace, stones digging into his ribs.

He risked a glance.

Twenty or so Germans were dug into the next terrace up, behind their own stone wall reinforced with sandbags. He saw the stubby muzzle of an MP40 poking over the top, cutting the air. Other men fired Mausers, their bolts working in quick motions.

They had the high ground. They had cover. They had a perfect angle down into the approach.

The Americans had rocks and wills.

“Marshall!” his lieutenant shouted from somewhere to his left. “We gotta get them out of there!”

“No kidding,” Caruso muttered next to David, jamming a fresh clip into his M1.

David’s mind did the math.

Twenty Germans. Two machine pistols. Rifles. Grenades, probably. His squad down to nine men after the slog north.

He checked his ammunition. Three full clips on his bandoleer. One in the rifle, already short a few rounds.

Not enough if he wasted them. Plenty if he used them well.

He took a breath.

“Cover me,” he said.

“Cover you with what?” Caruso demanded, but he was already raising his own rifle, popping up to throw a few shots toward the German wall.

David moved.

He sprinted low along the terrace, feet slipping in loose dirt, bullets zipping around him like angry bees.

He dropped behind a clump of stones closer to the enemy line, heart pounding, lungs burning.

He rose just enough to bring the sights of his M1 over the wall and fired.

A German in a field cap jerked and toppled. Another tried to move to the machine gun; David swung and fired again.

Ping.

Empty.

He didn’t flinch. His hands moved before conscious thought could intervene.

Flip. Clip. Rotate. Fire.

He was back on target in less than a second and a half.

On the enemy line, the surviving Germans blinked as if reality had stuttered.

They knew the sound of an M1 running dry. They’d been taught, long before this hill, to listen for that little note.

Somewhere in their training, some Unteroffizier had probably said:

“When you hear that ping, boys, that American is empty. That’s when you move.”

And so, on instinct, two of them moved.

They rose from behind their wall, bayonets fixed, rifles out, shouting as they charged.

They expected to cross the distance during the American’s four-second reload window.

They got three rounds in their chests instead.

They fell before they’d taken five steps.

Behind them, another German, an older man with a lined face and a sergeant’s chevrons, froze halfway up from cover. He stared, eyes wide, as David dropped him with a shot that hit just below the breastbone.

“Thought I was empty,” David muttered.

He fired again. And again.

The fight compressed into a series of pings and shots and men appearing and disappearing behind stone.

Ping. Flip. Clip. Fire.

It became a rhythm that left no room for fear.

He moved from cover to cover, never staying in one place long enough for the Germans to zero him. His rifle seemed never to rest, never to pause. When the ping came, the next shot followed almost instantly, like an echo.

On his periphery, he was aware of his squad advancing, emboldened by the disruption.

Caruso was laughing like a madman, firing and reloading with his own backwards grip.

The Germans tried to time their rushes. They heard the ping, started forward, and found themselves walking into bullets.

From their perspective, it must have felt like magic.

One man—Feldwebel Hans Dietrich of the 362nd Infantry Division—would later describe it in an interrogation room.

“We heard the American grand empty,” he said through an interpreter, voice still holding a trace of awe. “We knew the sound. We were trained to attack when we heard that sound. But this American… his rifle made the empty sound and then immediately he was shooting again. We thought it was a new weapon. Some kind of automatic rifle we hadn’t seen before. It was not possible that it was the same weapon.”

On that hillside, “not possible” died under olive trees.

The engagement lasted perhaps three minutes.

In those three minutes, David Marshall shot fifteen German soldiers.

He did it with one rifle and a handful of clips, moving and firing and reloading so quickly that no one watching could quite remember, later, what his hands had looked like.

They remembered the effect.

“I’d hear that ping,” Private Robert Wittman wrote later, “and before I could even blink, he was shooting again. The Germans couldn’t figure it out. They were timing their rushes for when they thought he’d be reloading and he just cut them down.”

When it was over, when the German fire sputtered and stopped, when the survivors raised their hands or fled, when the smoke began to thin, David’s squad collapsed behind the captured wall.

Caruso dropped onto his rear and let his rifle rest across his knees.

“You know how many times I saw you reload just now?” he panted.

David wiped sweat from his eyes with a filthy sleeve.

“No.”

“Neither do I,” Caruso said. “Felt like never. Like the damn thing just kept feeding itself.”

He grinned, teeth white against his grime-blackened face.

“They’re gonna want to pin a medal on you, Sarge,” he said.

David snorted, breathing hard.

“Let ’em pin it to the rifle,” he said. “I’m just the idiot holding it wrong.”

The Bulge

By October 1944, the Fifth Army had done something the War Department didn’t always excel at.

They’d admitted they were wrong.

Official training literature started to mention the “optional Marshall method” for reloading the M1 in close combat. Instructors were certified. Soldiers heading overseas learned both the standard reload and the backwards grip.

It was too late for a lot of men.

It wasn’t too late for some.

When the German offensive in the Ardennes hit in December, it hit like a hammer into glass. The front shattered into a thousand separate fights—platoons cut off, companies surrounded, villages changing hands half a dozen times in a day.

In that chaos, little things mattered.

Four seconds versus one and a half.

In a farmhouse outside Malmedy, Staff Sergeant William Chen of the 30th Infantry Division found himself in a room that smelled of plaster dust and fear, four Americans against eight or nine Germans.

Later, he would sit in a hospital bed with bandages on his arm and tell anyone who’d listen about it.

“They’d come in the front door,” he said. “We were on the stairs and behind furniture, shooting down. Close, you know? You could see their faces. My rifle went empty, I heard it ping, and I swear two of those Germans heard it too. They started to move—rush the doorway.

“I did that reload, the backwards one. I’d laughed at it in training, figured it was some stupid trick. I flipped the rifle and got the clip in and already I was firing again before their boots hit the floorboard. We killed six of them. Two dropped their guns and put their hands up. All four of us walked out of that house.”

In Bastogne, surrounded and frozen, Lieutenant Thomas Garrett of the 101st Airborne had written a letter to his wife when the fighting paused long enough for ink to dry.

He wrote about the cold. The hunger. The way the artillery shook the ground.

And he wrote about a moment in a shattered street when his rifle had gone dry with Germans twenty feet away.

“There was a moment I was sure I was about to die,” he wrote. “My rifle was empty, and there were Germans not 20 feet away. I did that reload, the one they taught us, the backwards one, and I got my rifle up before they got me. That sergeant, wherever he is, he saved my life. He saved a lot of lives.”

Somewhere, in another part of the snow-choked front, a private in the 106th Division lay in his foxhole with his heart stuttering in his throat as a German squad rushed his position.

His rifle pinged empty.

He had learned the old way and the new way in basic.

His hands chose the new one.

Flip. Clip. Rotate.

The Germans’ faces changed as they realized the window they’d trusted was gone.

A man in Pennsylvania, who had never seen the Ardennes, was there anyway—in the way fingers moved, in the way an empty sound no longer meant the same thing.

After the Guns

Wars end in treaties and dates.

They don’t end in the minds of the men who fought them.

When it was over in Europe—when the headlines screamed V-E DAY and the cities erupted in parades—David Marshall found himself sitting on a bench in a processing center, duffel at his feet, papers in his hand, orders in his pocket.

He’d been brought to Washington, briefly, in March 1946.

The War Department wanted to see him. The Army Chief of Staff wanted a demonstration.

He stood in a polished room with flags on the walls and did his trick with the M1 in front of men with stars on their shoulders.

He hit 1.2 seconds once. 1.4 most of the time.

They murmured. They nodded. They asked questions that made it sound like they’d known all along.

He gave an interview of sorts to a man with round glasses and a pencil.

“I’m not a professor,” he said. “I’m not an expert. I just figured out something that worked and I wanted to share it so other guys wouldn’t get killed. That’s all. I don’t need medals for that. I don’t need my name in papers. I just want to go home.”

A committee formed. Reports were written. People whose boots had never seen Italian mud debated whether the Marshall method should replace the standard reload entirely.

In the end, the army did what armies often do when faced with something new that works but scares the manual writers.

They split the difference.

Both techniques would be taught. Soldiers could choose.

It satisfied no one entirely.

By then, David was already thinking of hills that didn’t have guns on them.

He went back to Pennsylvania as Staff Sergeant David M. Marshall, honorably discharged.

He did not go back to the textile mill.

The GI Bill paid for a modest storefront on Main Street. He painted MARSHALL’S GUNS & REPAIR on the window in careful, blocky letters.

He fixed hunting rifles and shotguns. He cleaned family heirlooms that smelled of oil and dust and stories. He taught teenagers how to hold a .22 steady, how to keep a barrel pointed away from anything they didn’t want to destroy.

He preached safety like a country preacher preached sin.

“Finger off the trigger until you’re ready to shoot,” he’d say. “Know what’s behind what you’re aiming at. Treat every gun like it’s loaded. You remember those and you’ll live longer than I probably ought to have.”

He married a woman from town whose brother hadn’t come back from Normandy. They had two kids. He mowed his lawn. He paid his taxes. He listened to the radio.

In 1952, a reporter from the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette knocked on the shop door.

“Sergeant Marshall?” the man asked, notebook in hand. “We’re doing a piece on wartime innovations. I’ve seen your name in some old reports. You figured out that rifle reload thing, right?”

David wiped grease from his hands and shook his head.

“Those boys who didn’t come home,” he said. “They’re the ones who deserve stories. Not me. I just showed people a different way to hold their rifle. It wasn’t heroic. It was just practical.”

The reporter, faced with that quiet refusal, wrote about something else.

The story of the “backwards grip” drifted into training manuals and after-action reports and faded photocopies.

The man behind it went back to repairing broken firing pins and teaching kids how to breathe before they squeezed the trigger.

Ripples

Ideas don’t stay put.

When the M14 rifle replaced the M1 Garand in Army service, it came with a detachable box magazine instead of an en-bloc clip. The mechanics changed. The principle didn’t.

Instructors, many of whom had come up through Italy and France, emphasized keeping the firing hand on the grip, using the support hand to strip and insert magazines. They talked about minimizing exposure. They talked about shaving fractions of seconds.

They didn’t always mention the man in Italy who’d flipped his rifle under a hail of bullets.

When the M16 arrived in Vietnam, with its plastic furniture and high-velocity rounds, the language shifted again.

“Speed reload,” they called it now. Drop the empty magazine, slap in a full one, hit the bolt release. Keep the muzzle downrange. Keep your eyes up.

But in the background, old-timers would sometimes demonstrate a technique that looked suspiciously like an inverted reload.

“Fastest reload,” one instructor told a class of impatient draftees, “is the one that keeps your firing hand where it belongs. Don’t overthink it. Do what works.”

In competitive shooting circles decades later, trainers with fancy sunglasses and shooting jerseys would stand under bright lights and demonstrate magazine changes that echoed the same insight: the rifle is a system. Your body is part of that system. You find the path that removes wasted motion.

Somewhere in that chain of muscle memory and doctrine, there was a loop of thread in a noisy mill, a boy watching a machine and seeing where it skipped.

The Man Who Held His Rifle Wrong

In 1985, the 36th Infantry Division held a reunion in a hotel ballroom that smelled faintly of stale coffee and aftershave.

Nametags hung on suit jackets that strained over old shoulders. Pictures of young men in old uniforms sat propped on tables, smiling out of frames while the older versions of those faces drank and laughed and wiped their eyes.

David went because an old friend nagged him into it.

“You can’t hide in that shop forever,” Caruso had said over the phone, his Brooklyn accent softened by time but still there. “They’re calling us ‘the Greatest Generation’ now, you hear that? Might as well show up and see if anyone believes it.”

So he went.

He shook hands with men who looked nothing like the skinny kids he remembered and exactly like them.

He listened as stories were told and retold, details shifting a little with each iteration.

He did his best to deflect any mention of “that reload thing” with a shrug.

Near the end of the evening, as the bar began to wind down and people gathered in clusters of three or four, a man in a colonel’s uniform approached him.

The man was in his sixties, hair silver at the temples, posture still straight despite the years.

“Sergeant Marshall?” he asked.

David blinked.

“Not for a long time,” he said. “But yeah.”

The man swallowed, his eyes shining a little more than the room’s fluorescent lights could explain.

“I’ve waited forty years to say this to you,” he said, extending his hand.

David took it.

“Because of you, I came home,” the man said. His voice broke on the word home. “Because of you, I had a family. Because of you, I’m standing here.”

David squeezed the man’s hand gently.

“You’re welcome,” he said, because anything else felt too big for the space between them. “Glad you made it.”

He changed the subject—asked what the man had done after the war, what his kids were like, what he thought of modern rifles.

But when he went back to his room that night and sat on the edge of the bed, listening to the hum of the hotel air conditioner, he let himself feel the weight of those words.

Because of you, I’m standing here.

He thought about the men who weren’t standing anywhere.

He thought about the ones who had their names carved in stone overseas and the ones whose graves lay under modest markers in American cemeteries.

He thought about the way a little metal clip had clanged on stone in Salerno and how, for no good reason other than his refusal to accept that the experts knew best, he’d decided to do something backwards.

He wasn’t a man given to prayer, not now.

But he bowed his head and closed his eyes and sat with the memory of those three minutes on a hill near Fiesole, and the boys in the Ardennes, and the four seconds that might as well have been forever.

David Marshall died in 1987 at the age of sixty-eight, in the same Pennsylvania town where he’d been born.

His obituary in the local paper mentioned his gun shop, his work with youth groups, his service in World War II.

It did not mention his contribution to infantry tactics.

That omission would have pleased him.

He had never liked being the center of a story.

The stories belonged, in his mind, to the boys who hadn’t come home.

But somewhere, in the way soldiers today are taught to handle their rifles, in the way instructors talk about minimizing downtime and keeping a weapon in the fight, there is a ghost of a young man behind a wall in Italy, flipping his rifle upside down because the wall was too low and the bullets were too close.

There’s a quiet thread that runs from a textile mill in western Pennsylvania to the Ardennes, to Vietnam, to training ranges around the country.

The greatest innovations rarely come from where we expect them.

They come from the observers. The tinkerers. The people who refuse to accept that the way things have always been done is the way things must always be done.

David Marshall had no degree, no rank high enough to impress the boards, no permission to question the experts.

He questioned them anyway.

And in the frozen forests of Belgium, in farmhouses outside Malmedy and foxholes near Bastogne, American boys paid something other than their lives when their rifles pinged empty.

They paid a fraction of a second to a backwards grip, to a man who held his rifle wrong.

They mocked his “backwards” rifle grip.

Then, on a hill in Italy, he shot fifteen Germans without ever giving them the empty moment they were counting on.

And because of that—because of him—hundreds of other men got the chance to grow old enough to sit in hotel ballrooms and tell stories.

THE END

News

CH2 – How a “Rejected” American Tank Design Beat Germany’s Best Armor

December 1944 Ardennes Forest, Belgium Snow chewed at the edges of the world. It came sideways, carried on a cruel…

My Coworker Tricked Me Into Dinner At Her Place, Then Told Her Parents, “This Is My Boyfriend.”

The rain was doing that thing it only seems to do in the city—coming down sideways, ricocheting off glass…

CH2 – The Postman Who Outsmarted the Gestapo – The Untold WWII Story of Victor Martin…

Pins in the Map January 15, 1943 Avenue Louise, Gestapo Headquarters Brussels, German-Occupied Belgium Klaus Hoffman hated the color…

At 15, I was kicked out in the rain because of a lie my sister told. My mom yelled, “You’re not…

I remember the exact temperature that night. Fifty-three degrees. It was one of those random, useless bits of information your…

At the airport, my sister-in-law burst into laughter when the staff removed my name from the boarding list. “Guess who’s not coming along?” she taunted. My husband watched with a smug smile. But only minutes later, the pilot emerged from the jet bridge, paused in front of me, and gave a crisp salute. “Ma’am, the jet is ready for you.”

If I had to pinpoint the exact moment my old life cracked, it wasn’t when I found out my husband…

“Where’s the Mercedes we gave you?” my father asked. Before I could answer, my husband smiled and said, “Oh—my mom drives that now.” My father froze… and what he did next made me prouder than I’ve ever been.

If you’d told me a year ago that a conversation about a car in my parents’ driveway would rearrange…

End of content

No more pages to load