November 1943

Bougainville Island, Solomon Islands

The rain came in sideways, fine and warm and full of red clay.

It turned the floor of the foxholes into soup and glued every cigarette paper to wet fingers. It clung to helmets, slicked the bark off trees, filled the bottoms of boots. Somewhere out beyond the tree line, a bird shrieked and then cut off in the middle of the sound.

Private First Class Raymond Beckett lay on his belly in the muck and watched tracers float.

They weren’t supposed to float. According to the ordnance pamphlets back in Washington, the little .30 caliber carbine round left the muzzle at nearly two thousand feet per second and stayed flat out to three hundred yards. Effective range, they called it. Neat columns of numbers. Confidence in print.

Out here, in the volcanic mud of Bougainville, those numbers lied.

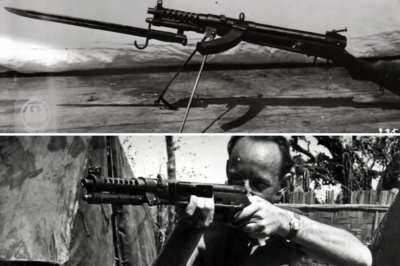

Beckett squeezed the trigger again. The M1 carbine kicked lightly against his shoulder. Fifty yards in front of him, the muzzle flash was a brief yellow spit; three hundred yards out, the tracer arced like someone had hung it on a string and tugged it down.

The glowing red line drifted left, then right, caught the breeze, and hit somewhere that did not matter while the jungle in front of him stayed alive and full of invisible rifles.

“Any luck?” someone hissed over to his right.

Beckett didn’t take his cheek off the stock.

“Depends what you call luck,” he muttered.

He worked the bolt lever with the side of his hand, felt the next round chamber, and watched the notch of the rear sight cut another notch of sky.

Past two hundred yards, that little bullet gassed out. Past three hundred, it started to fall like a thrown rock. At four hundred, with the faint wind running crosswise through the trees, he could watch his rounds wander eight, ten inches from where he wanted them.

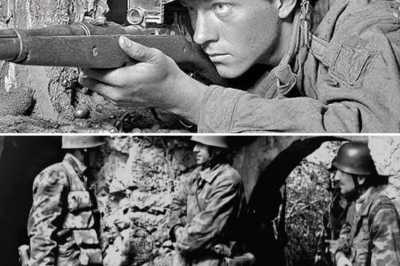

The Japanese snipers knew it.

They had done their own math.

They were sitting out at three-fifty, four hundred yards, tucked into triple-trunk trees and bamboo clumps, the long 6.5mm Arisaka rifles steady against roots or branches. That distance was just inside their comfort zone and just outside his.

It wasn’t an accident. Nothing about this fight was.

The first man to die had been Corporal James Whittaker.

November 4th. Overcast morning. The rain right then had been a fine mist instead of a true downpour. Whittaker had been two foxholes over, sharing a joke about canned hash, when they’d heard the first sharp, clean crack.

It wasn’t like a machine gun. It wasn’t like anything American to Beckett’s ear. Just a single heavy smack of sound, like someone slamming a door far away.

Whittaker had been standing up, one hand on the lip of his hole. The round had gone in low, right under the jaw, and exited someplace the corpsman didn’t even bother trying to find. He’d dropped straight down with a surprised look that stuck to Beckett’s eyelids for three nights after.

November 6th, Private Hayes went next.

He’d been trying to spot the muzzle flash. The company had poured fire into an entire stretch of tree line after Whittaker fell, chewing leaves, chopping branches, destroying nothing in particular. The captain had sent Hayes up on a root to get eyes above the rest.

Hayes had lifted his head.

Crack.

The bullet had taken his eye and a good piece of his brain. He’d gone over backward without a sound.

November 9th, Sergeant Riggs—Beckett’s own squad leader—had been crouched over a map, one hand gesturing toward a gully he wanted the 60mm mortar to walk rounds into.

Beckett had watched him trace the line with a stub of pencil.

A shot. A spatter of red. Riggs had made a noise like someone letting air out of a tire and then folded over the map.

By November 12th, the company was locked to the ground.

Eleven men dead in seventy-two hours. Snipers could do that to you. Not because of the body count, though that was bad enough, but because of the way every head learned to stay low and every foot learned not to move unless someone else was drawing fire.

Machine guns you could muscle through. Mortar fire you could outrun or crawl under. But a man with a rifle who knew how to use it from a place you couldn’t find—that froze a unit.

They all knew, in the abstract, where the shots were coming from. Every time a man fell, every rifle that could still move spat rounds into the tree line. They were generous with ammunition. Thompson submachine guns chattered. BARs chewed. M1 Garands cracked and echoed.

And still, when the smoke cleared, the trees stood, and somewhere inside them, a man with a scoped rifle adjusted his sling and waited for someone else to move.

Beckett could feel the fear setting up shop like a long-term tenant.

Men refused to move in daylight. Messages that should have been hand-carried waited for darkness. They pissed in their foxholes rather than stand up long enough to use a slit trench.

And the carbines, light and handy and “effective to three hundred yards” when you read the manual, were about as useful as slingshots against a single man at four hundred.

Beckett had something most of the men around him didn’t have, though.

He had a memory of another place where steel and wood talked louder than pamphlets.

Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, smelled like coal dust and old oil in the summer of 1933.

The northeast wind pushed the soot down into the valley, and the breakers on the hill kept chewing up rock and bone. Men went into those buildings and came out bent, coughing, and gray.

Raymond Beckett’s father was one of them. He came home limping, knees permanently ground down by a lifetime of hauling rock.

Beckett loved him, but he did not love the breaker.

His sanctuary was on South Main Street, in a brick garage that had once housed automobiles and now housed what his uncle called “a different kind of machine.”

Guns.

It wasn’t a factory. It was one man, one bench, a sparkling of tools carefully hung and carefully cleaned, a slow stream of rifles and shotguns and revolvers in every state of disrepair.

Miners brought in their deer rifles with pitted bores. Farmers brought in old Winchesters that had been left behind in barns during bad winters. State troopers came in with service pistols that had taken too much grit on a muddy road and needed their innards scraped out and polished.

“Can’t buy another,” they’d say. “You fix this one or I go without.”

At twelve, Beckett swept the shavings off the floor and collected the brass that fell from customers’ pockets. He watched his uncle work until watching wasn’t enough, and the old man slid a file into his hand.

“Metal’ll talk to you if you listen,” his uncle said. “You just have to learn the language.”

The language wasn’t in books. It was in fingertips.

He learned that a factory crown on a muzzle—the tiny bevel at the rifle’s mouth—was supposed to be perfect but almost never was. You could feel a tiny burr catch your thumbnail; you could see a bullet hit a bit wide and know gas had escaped one side a hair faster.

He learned that “standard” stock length fit almost no one perfectly. Men with long arms craned their necks. Men with short arms fought the rifle out of cover. He watched his uncle take a rasp to a beautiful piece of walnut, shave off half an inch, round a corner, and turn a gun that fought its owner into one that slid into the pocket of a shoulder as naturally as a handshake.

He learned that military specifications were compromises. They were written by men who had never seen half the people who’d hold the guns. They were trying to equip thousands, not to satisfy one man’s cheek weld.

“You think the Army cares if this fits you or the scarecrow down the road?” his uncle would say. “They care that it can be made fast and the same, over and over. The rest is on you.”

By sixteen, Beckett could look at a rifle on a rack and tell you what was wrong with it before it fired a shot. By eighteen, he could take a hacksaw to a barrel or a rasp to a stock and make the thing do something its designer hadn’t intended while still sleeping at night.

He learned that the trick wasn’t disrespecting the weapon.

It was knowing it could be better.

That knowledge stuck with him long after he left Pennsylvania.

September 1942, Camp Lejeune, North Carolina.

The Marine Corps handed him an M1 carbine like they handed one to every radio man and runner who wasn’t expected to hump a full-size Garand everywhere.

To most of the recruits, it was a dream compared to the long Springfield they’d trained with on the range.

Light. Short. Handy. Fifteen rounds in a magazine, not five in a clip. You could carry twice as much ammunition for the same weight.

To Beckett, it felt… off.

He accepted it the way he’d been taught—stock first, muzzle down, eyes on the man passing it over—and as soon as it was his, he shouldered it.

The length of pull—the distance from the trigger to the buttplate—was just wrong enough to matter. Fine if you had time and space to mount it carefully, wrong if you had to snap it to your shoulder from a crouch behind something.

He sighted in.

The rear aperture sat a little high. The front sight post looked too wide, a thick blade that would cover a man at distance instead of slicing him neatly.

He ran his fingers down the barrel. Eighteen inches, thin, gas port near the end. The elves at Winchester and Inland had done their homework, but he could feel where they’d optimized for reliability in all conditions, not maximum precision.

Somewhere, an ordnance officer had signed off on a drawing that said this was the right balance.

Somewhere, that man had never been shot at.

In 1942, Privates did not tell ordnance officers their geometry was wrong.

So Beckett kept his mouth shut.

On the range, he adjusted. He re-learned his hold. He played with how hard he pulled it into his shoulder, how much cheek pressure, how far he leaned into recoil that barely existed.

He qualified expert. Two hundred thirty-eight out of two hundred fifty.

The instructor chalked his score up to natural talent. Beckett knew better. It was ten percent rifle and ninety percent hands remembering what a file could do if he’d been allowed to use one.

Then he shipped out.

Bougainville was not the kind of island the travel posters promised.

There were no beautiful beaches for more than about ten yards inland before the jungle closed in like a fist. The ground rose and fell in steep, slippery ridges. The soil was volcanic and red. The mud grabbed your boots and held on.

The Japanese had been there for months.

They weren’t stupid. They hadn’t lined up on the water line waiting to be bombarded. They’d pulled back into the trees, into the ravines, into the buried bunkers and spider holes they’d had time to carve.

They’d walked the ridges and gullies. They’d sat on their heels in the shadows and watched the landing beaches through binoculars.

They’d done what any good marksman does: they’d measured.

The American landing on November 1st had been bloody, but successful. The Third Marine Division had shoved a toe into Bougainville and refused to give it up.

The problem was everything past the toe.

By the second week of November, the Japanese had the Americans measured, too.

They didn’t waste ammunition. They didn’t take long, showy shots. They didn’t fire into crowds unless they had to.

They picked.

Radio men. Squad leaders. Anyone who stood up for more than a second. Anyone who thought he could crawl fast enough in daylight.

They were careful with their own exposure.

Three hundred fifty yards. Maybe four hundred fifty, at the outside.

Arisaka rifles, long as a man’s arm, lay heavy and steady on branches they’d tested three, four times. Their scopes, when they had them, weren’t as good as American glass, but they didn’t have to be.

Distance was their armor.

Every time a bullet flashed past Beckett’s position and someone screamed or didn’t, he watched where the bark flew. He watched how the leaves shook half a second later.

He watched where his own bullets went when he tried to answer.

They spun off too soon and fell too fast.

One night, sticky with sweat even in the damp, he made it official.

He crept over to Lieutenant Porter’s foxhole and cleared his throat.

“Sir,” he said. “Requesting a change in weapon.”

Porter looked up from the map he was studying, face drawn in the flickering yellow of a shielded flashlight.

“To what, Beckett?” Porter asked.

“Garand, sir,” Beckett said. “The .30-06 has the reach for this kind of work. My carbine rounds are dropping into the mud halfway to those sons of bitches.”

Porter took his time answering. He was a good officer, as such things went—earnest, by-the-book, more worried than he let on.

“Radio men and scouts carry carbines,” he said finally. “That’s how the table of organization runs. Riflemen carry Garands.”

“With respect, sir,” Beckett said, “the table of organization isn’t getting shot at from four hundred yards.”

Porter’s jaw clenched.

“We can’t disrupt ammunition logistics because your ballistics don’t agree with Washington,” he said. “The carbines run on different ammo. You start mixing weapons and cartridges across roles, and suddenly we’ve got confusion in a fight.”

Beckett thought of troops in other wars, with mismatched rifles and mismatched calibers and mismatched everything, and somehow they’d still managed to fire the right bullets at the right time.

“That’s a mess we can sort out, sir,” he said.

Porter’s voice took on the tone every enlisted man knew.

“This isn’t a debate, Beckett,” he said. “You have your carbine. Make it work.”

Beckett swallowed what he wanted to say next.

“Yes, sir,” he said. “Permission to return to post.”

“Granted.”

He crawled back to his hole.

Somewhere out beyond the perimeter, a sniper adjusted his sling.

Beckett lay on his side in the shallow ditch full of red water and thought about rules.

The Marine Corps was not going to fix this.

The supply chain was not going to fix this.

If the carbine was going to do something it had never done before, he’d have to make it.

He’d have to stop being Private First Class Raymond Beckett, serial number such-and-such, and be twelve-year-old Ray with a file in his hand and his uncle standing over his shoulder.

There were worse things to be.

He waited until the company armorer went on watch.

Sergeant Polansky was a big man with moments of kindness, but he believed in everything being “by the book” so hard he probably would’ve court-martialed his own mother if she’d touched a weapon without the right requisition.

At 2300, Polansky trudged off toward the far edge of the perimeter to relieve a guard.

Beckett lay still, listening to the sound of his boots in the mud get softer.

Then he moved.

The supply tent was a sagging piece of canvas that smelled of oil, mildew, and paper. Rifles stood in racks. Boxes of carbine ammo sat in stacks, stenciled and sealed. On a crate in the back, a canvas tool bag slumped, buckle undone.

Beckett’s heart thudded as loud as a mortar in his own ears, but his hands stayed steady. He lifted the flap.

A hacksaw with a short handle. A triangular file, edges worn from years of use. A couple of screwdrivers. A small bottle of gun oil.

He pulled what he needed, rearranged the rest so nothing looked missing, slid the bag back into place, and slipped outside.

The secondary fighting hole he’d picked was shallow and half-collapsed, too exposed during daylight to be worth using. At night, it made the perfect little workshop.

He slid into it, pulled his poncho over his head and his hands, and became a dark lump in the mud.

The hacksaw teeth bit steel with a sound that seemed, to him, as loud as artillery. To anyone more than ten yards away, it was no more than a bug’s wings against the rain.

He sawed.

Conventional wisdom said longer barrels meant more accuracy. Every hunting magazine he’d read before the war had said it. Every sergeant he’d ever heard hold forth on marksmanship had said it.

Longer barrel, more velocity. More velocity, flatter trajectory.

That was true—up to a point.

Beckett wasn’t chasing velocity. The carbine had enough to get the bullet out where it needed to go. The problem was what the barrel did as that bullet left.

Eighteen inches of military steel vibrated when it fired. It whipped and twisted in a pattern no two carbines shared exactly. The bullet left when that whip was in a different place each time, depending on tiny differences in how the gun was held, how the trigger was pulled, how the gas system cycled.

Shorten the barrel and you stiffen it. Less whip. Less variance.

You lost a little velocity, but you gained consistency.

That was a trade he was willing to make. At four hundred yards, he wasn’t trying to hit a bullseye on a paper target. He was trying to hit a man behind a tree.

He counted strokes in his head. The hacksaw rasped, metal filings dusting his fingers. His arms burned. He wondered when the whole company would hear the noise and climb out of their holes to watch him ruin government property.

After eighteen minutes that felt like eight hours, the barrel fell away with a small, final snap.

He held the carbine up under the poncho.

The end looked wrong without its front sight housing, short and ugly, the steel raw and bright where the bluing had ended three inches back.

He’d just taken a service weapon and made it into contraband with one cut.

Now it needed a new crown.

The last inch of barrel was where any rifle earned its hits. If that surface wasn’t perfectly square and smooth, gas escaping unevenly behind the bullet would kick it as surely as a finger flicking it from one side.

In a shop, his uncle would have set the barrel up in a lathe, used a facing tool, micrometers, gauges. Perfect circles. Measured thousandths.

In a foxhole on Bougainville, Beckett had a file and his thumb.

He wrapped his left hand around the barrel end, thumb pressed flat across the muzzle, fingernail feeling the edge where steel and air met. With his right hand, he took the triangular file and held it at an angle, shaving tiny bites of steel off the outer edge in even passes.

Three strokes. Rotate the barrel a quarter turn. Three strokes. Rotate again.

He worked by feel, not sight. He’d done this before in his uncle’s shop, closing his eyes and letting his thumb tell him when the edge was even all the way around.

The trick was not to hurry. Hurry left high spots that ruined bullets.

The rain pattered on his poncho. Somewhere, someone coughed in their sleep. The night smelled like wet jungle and cordite ghosts and the faint chemical tang of gun oil on his fingers.

He checked the edge with his thumbnail.

Smooth. No catches. The inside edge of the bore, where it met the new crown, felt sharp and even.

He let out a breath he hadn’t known he was holding.

The barrel was three inches shorter. The muzzle was square.

Now the rifle had to fit him.

He unscrewed the buttplate, wedged it against a root, and took the rasp to the stock.

Military stocks were made to a length that fit a theoretical “average” man. Beckett had never met that man. If he had, he would’ve told him he was a statistical lie.

Beckett’s own arms were a hair shorter than the average. When he mounted a standard carbine, he either had to stretch for the trigger or compromise his cheek weld.

He didn’t want to compromise anything.

He shaved the stock back, coarse teeth biting walnut. An inch. Maybe a hair more. He rounded off the bottom corner that dug into his shoulder pocket, smoothed a ridge that caught on web gear.

He held it up under the poncho, mounted it, felt it slide into place.

Better.

He ran the rasp lengthwise to smooth the worst of the ridges, knowing the raw wood would drink every drop of moisture in Bougainville, swell, and then settle again.

That was a problem for the future.

Last were the sights.

At distance, the thick front sight blade of the carbine covered a man’s chest. If you lined the top of that blade up dead center on a target, you were essentially guessing at where his edges began and ended behind the steel.

He needed a finer post.

He took the file and kissed the top of the front sight, then worked it down slowly, thinning it, lowering it, making it a slimmer blade that would sit lower in the rear aperture and let him see not just a blot of jungle but the edges of a shadow inside it.

If he went too far, he’d throw point of impact too high. He trusted his hands not to go too far.

By 0200, his shoulders screamed, his hands were slick with a mix of sweat and rain and oil, and the carbine in his lap looked like something a junk dealer might turn up his nose at.

The barrel stubbed short of where everyone knew a barrel was supposed to end. The stock had raw, pale wood exposed, rounded and rough. The front sight was a slim tool-steel sliver instead of a fat blade.

It looked ridiculous.

But when he shouldered it, it came up like it had grown out of his torso.

The balance point had shifted back. The barrel cleared the lip of the foxhole faster. The stock settled into his shoulder without a fight. The new crown glinted faintly in his imagination, delivering each bullet the same gentle send-off.

He lowered it, wiped the tools down, slid them back into the canvas bag.

He returned the bag to the supply tent exactly where he’d found it.

By the time Sergeant Polansky came back off watch, Beckett was in his hole again, carbine tucked under his chest, eyes closed.

He slept better that night than he had in a week.

Dawn on November 15th came with a cracked egg of sky and low, rolling thunder that wasn’t thunder.

The Japanese snipers didn’t wait for full light.

At 0623, a radio man three holes over waved to get someone’s attention and started to stand.

The crack of the Arisaka sounded almost before his knees left the mud.

He dropped, hand still half in the air, a neat hole in his throat. Blood came out like someone had turned on a faucet.

“Sniper! Down!” someone yelled, though nobody needed telling.

Every head flattened. Every hand clenched around a rifle.

Four minutes later, a lieutenant—young, thin, and too proud to crawl—popped up to shout an order.

Crack.

The bullet hit his shoulder instead of his skull, but the force spun him, threw him halfway out of his hole. He screamed, then bit it off.

At 0700, the company was welded to the ground.

Sullivan, a private first class from Ohio, had the misfortune to be nearest the wounded lieutenant. He looked over at the officer’s pale face, saw the blood pouring out, and made the decision nobody wanted to make.

“I’m going,” he said, and before anyone could stop him, he pushed himself up and scrambled forward.

He didn’t make it three yards.

The sniper’s bullet took him low in the belly. He went down screaming, clutching at his midsection, legs kicking.

He screamed for four minutes.

There was no morphine that far forward. No one who could reach him without joining him.

Platoon Sergeant Grantham crawled over to Beckett’s hole, mud streaked up his neck, jaw clenched.

He was a big man with a kind face that had gone tight and flat over the last week.

He pulled himself up alongside Beckett and raised his head just enough to see the carbine.

He stared.

The barrel was obviously cut. You didn’t have to be a gunsmith to know it. Every Marine in the Pacific had seen enough carbines to know where the muzzle was supposed to be.

“Jesus Christ,” Grantham whispered. “That barrel is cut.”

“Yes, Sergeant,” Beckett said.

“You know that’s destruction of government property?” Grantham asked quietly. “You know they send you to Leavenworth for that? They teach you that in boot, or were you asleep that day?”

“Yes, Sergeant,” Beckett said again.

Grantham looked past him, out toward the triple-trunk tree Beckett had been watching all week. It rose from the jungle floor like three fingers, coming together halfway up. The branches near the top were thick enough to hide a man. It was a perfect perch.

He looked back at Sullivan’s body, lying in the open, shuddering.

He looked at the cut barrel again.

“Do you see where that shot came from?” he asked.

“Yes, Sergeant,” Beckett said. “Triple-trunk tree, about four hundred yards. Eleven o’clock from us.”

Grantham’s voice dropped even lower.

“Can you hit him with a regulation carbine?”

“No, Sergeant,” Beckett said. There was no point lying.

“With this,” Grantham said, nodding at the illegal carbine, “can you?”

“Maybe,” Beckett said.

Grantham’s eyes held his for a long second.

This was where training manuals and reality parted company forever.

“Make it count,” Grantham said. “Or I’ll put you in the brig myself, after they send you home.”

“Yes, Sergeant,” Beckett said.

He moved.

He slid up to the lip of the foxhole, keeping as much of himself under cover as possible. The poncho was gone—the rain was lighter now, just enough to bead on the barrel.

He didn’t look for a man.

He looked for the absence of nature.

The triple-trunk tree was ahead, dark against a lighter patch of sky. Leaves shifted in the faint breeze. Branches moved.

There, in the crook where two limbs met, was a shadow too dense. A spot where the leaves seemed arranged more carefully than chance.

The wind was coming from the left, maybe five miles an hour, if he judged by the way the fronds on a nearby palm fluttered. At four hundred yards, a carbine bullet would drift nearly ten inches in that wind.

He shouldered the carbine.

It came up fast, more like a pistol than a rifle, stock settling into the groove it had been cut for.

The rear aperture circled the world. The front sight blade, now thinner and lower, found the space just left of the shadow, not the shadow itself.

He raised it a little higher than felt natural. At four hundred yards, with the carbine zeroed for two hundred, the bullet would drop nearly a foot. He’d fired enough rounds on enough ranges to feel that arc in his bones.

He drew in a breath and let it out until his lungs were half empty. The world seemed to quiet down, even with Sullivan’s ragged gasps still audible and men muttering prayers under their breath.

He pressed the trigger.

The modified crown spat the bullet into the world with a sound that was sharper, somehow, than before—less barrel to damp it, more bite to it.

He felt the stock bump his shoulder. The sights lifted and settled.

He did not wait to see.

He worked the bolt lever with a fast jerk and brought the front sight back to the tree.

For a heartbeat, nothing moved.

Then the shadow shifted.

A dark shape came tumbling out of the canopy, arms limp, rifle clattering against branches as it fell. It hit the jungle floor with a thud they could hear even through the distance and the foliage.

Sullivan stopped screaming.

He was beyond saving anyway.

The company lay there, stunned.

A carbine wasn’t supposed to do that.

Grantham’s hand closed on Beckett’s shoulder.

“Again if you have to,” he murmured. “He might not be alone.”

He wasn’t.

Nineteen minutes later, a shot cracked from a bamboo cluster farther along the ridge, this one angling in from their right, targeting a corpsman who’d made the mistake of lifting his head.

The bullet took the brim of the corpsman’s helmet, clipped it, and sent it spinning.

Beckett was already moving.

The carbine now felt like an extension of his hands. He slid along the foxhole lip, found a new angle, shouldered in one motion.

Bamboo is a tricky target. Slender, flexible, it can deflect bullets or hide men almost completely.

He watched for a suggestion of outline, a glimpse of cloth among green, the tiny flat glint of glass.

There—a sliver of pale where a face might be behind the stalks.

He fired three shots in quick succession, adjusting a hair between each, walking them in.

The first chopped a piece of bamboo. The second punched deeper into the cluster. The third produced a sharp, high scream and sent a rifle tumbling from inside, barrels and stock clacking against the ground.

“Two,” Grantham whispered.

Word spread, even as the company stayed pinned. Men whispered to one another along the line, eyes flicking toward Beckett’s position.

They’d all seen the cut barrel now. They knew what it meant. Every man who’d ever been yelled at on the rifle range knew that altering a weapon was the kind of sin that had you cleaning grease traps in the brig until your fingers fell off.

They also knew that in the last half hour, they’d watched something happen that hadn’t happened in days.

The enemy had bled in daylight.

Over the next two days, the math of the battlefield changed.

Snipers, used to dictating the rhythm of fear, found themselves being hunted by a weapon they thought they understood but didn’t.

Beckett didn’t sleep much. He lived in a thin slice of time between the crack of an enemy shot and the crack of his own.

One sniper set up on a ridge farther back than the rest, thinking distance was safety. Beckett watched him for half a day, mapping the angle in his head.

“Four hundred sixty, maybe seventy yards,” he told Grantham. “That’s stupid big for this cartridge.”

“Can you hit it?” Grantham asked.

“On paper? No,” Beckett said. “Out here? I don’t know. But I’ll try.”

He aimed what felt like two feet over the man’s position. It was guesswork. Gut. A combination of all the firing tables he’d never officially seen and every shot he’d ever taken.

The modified front sight blade floated over empty air. The triple trunks of another tree stood thirty yards in front of the target. His brain tried to tell him he was aiming at nothing.

He pressed the trigger anyway.

The bullet arced out, slowed, dropped.

A second later, the distant figure—no more than a smear even through the sights—jerked, rolled, and disappeared.

Another time, two snipers opened up almost simultaneously, one left, one right, trying to shock the Americans into exposing themselves.

Beckett swung, fired, swung again, fired, his hands moving faster than his thoughts. Eleven seconds. Two targets. Two bodies falling.

By the end of forty-eight hours, he’d dropped nine men.

The siege wasn’t broken in one dramatic charge. There was no bugle, no shouted “Follow me!”

It broke in silence.

The company realized, gradually, that no one had been shot that day, or the next, or the next.

They stood up in daylight again, first hunched, then fully. They moved messages by hand. They shifted positions. They advanced the line a hundred yards and then another hundred.

The Arisaka cracks still came, but not as often. And when they did, there was always the possibility that somewhere, Beckett was already bringing the carbine to his shoulder.

Sometimes courage is getting up after you’ve been knocked down.

Sometimes it’s trusting a man with a hacked-up rifle more than you trust the manual.

On November 18th, Captain Hendricks called Beckett into the makeshift command post—a dugout with a poncho for a roof and a folding table for a desk.

The illegal carbine sat on the table, looking uglier than ever under the weak light.

The barrel, three inches shorter than God and the Ordnance Department had intended, looked stubby and wrong. The stock’s raw wood had darkened some, but the rasp marks were still visible. The front sight was a thin, shark-fin sliver.

Hendricks stood behind the table, hands resting on its edge. He was tired, like every officer on the island, but his eyes were clear.

“You did this?” he asked.

Beckett stood at attention, boots leaving red prints on the floor.

“Yes, sir,” he said.

“You know,” Hendricks said quietly, “that this is destruction of government property.”

“Yes, sir,” Beckett said.

“You know that’s a court-martial offense,” Hendricks continued. “They tattoo that into your skull in boot camp.”

“Yes, sir,” Beckett said again.

Hendricks picked up the carbine.

He hefted it, feeling the balance. He brought it to his shoulder, sighted along the barrel, noticed how quickly it came up, how snugly the cut stock settled in.

He lowered it and looked at Beckett.

“Platoon Sergeant Grantham tells me you’ve accounted for nine snipers in two days with this thing,” he said.

“Yes, sir,” Beckett replied.

“Since you started using it,” Hendricks went on, “our casualty reports have dropped from about four percent a day to damn near zero.”

He let that hang in the air for a second.

“I have a problem,” he said finally.

“Yes, sir?” Beckett said.

“If I court-martial you,” Hendricks said, “I lose my best shooter at a time when snipers are killing my men. If I commend you, every private in the Pacific is going to take a hacksaw to his rifle because he thinks he’s John Browning.”

A faint, unwilling smile tugged at the corner of Beckett’s mouth. He killed it before it fully formed.

“Sir,” he said, “I didn’t do it for a medal.”

“I know why you did it, son,” Hendricks said. “You did it because the people in Washington think in tables and ranges, and you think in dirt and blood.”

He set the carbine back down.

“So here’s what we’re going to do,” he said. “Officially, this rifle does not exist. Officially, it was lost, damaged beyond repair, or eaten by a crocodile for all I care. This is a field expedient modification. It never happened.”

“Yes, sir,” Beckett said.

“You will not speak of it to anyone outside this company,” Hendricks continued. “You will not write home about it. You will not share the details of what you did to anyone who doesn’t have bars on his shoulders.”

Beckett swallowed.

“Yes, sir,” he said.

“I am not going to pin a medal on you for this,” Hendricks said. “Even if I thought you deserved it—and I do—because the minute I do, some colonel in the rear will be obligated to explain why one of his privates broke every rule in the book and got praised for it.”

“Yes, sir,” Beckett said again.

“But,” Hendricks said, “you are going to train two other men in how you hunt snipers. Not with a hacksaw. With your head. With your eyes. With your patience. You understand?”

“Yes, sir,” Beckett said.

Hendricks nodded once.

“Dismissed,” he said.

Beckett turned to go.

“Beckett,” Hendricks called after him.

“Sir?”

“You keep that rifle clean,” Hendricks said. “And you keep my men alive.”

“Yes, sir,” Beckett said.

War has a way of losing track of things.

In early 1944, Beckett took shrapnel from a mortar round near Hill 700. It tore through his left thigh and his side. The corpsmen did what they could in a clearing, then put him on a stretcher and carried him back to a field hospital, where a surgeon with steady hands and not enough sleep dug out steel and stitched him up.

He left Bougainville on a hospital ship, staring at the gray water, missing a piece of himself and the carbine that had become an extension of his arms.

The rifle went into a pile.

Somewhere behind the line, a supply sergeant looked at a beat-up carbine with a cut barrel and a shaved stock and marked it “unserviceable.” Maybe he shook his head at the vandalism. Maybe he didn’t care.

It likely ended its days in a smelter, becoming part of something else. A jeep axle. A ship’s deck fitting. A new rifle that would be made to spec and never know what a hacksaw felt like.

Beckett went home to Pennsylvania with a scar that ached in the winter and a few ribbons in his duffel.

He went back to the gunsmith shop on South Main Street.

The coal dust was still in the air. The rifles were still on the rack. His uncle was older, hands a little slower, but the bench was the same.

Beckett married a girl he’d written to from the island. They raised three kids. He fixed hunting rifles and shotguns for state troopers, miners, and farmers. He recrowned barrels on deer rifles and cut stocks on .22s for young boys whose eyes shone like his had at twelve.

Sometimes, when he had a file in his hand and the curl of steel came away just right, he’d think of Bougainville and a barrel that no longer existed.

In 1953, a Marine Corps historian sent him a letter.

It was typed, formal, on Government stationery.

Dear Mr. Beckett,

We are conducting a study on field modifications to small arms during the Bougainville campaign. There are rumors regarding modified M1 carbines used with unusual effectiveness. We understand you served with Third Marine Division during that period. Would you be willing to provide any recollections?

Respectfully,

Captain ——, USMC Historical Section

Beckett read the letter twice.

He thought of Sullivan screaming in the mud. He thought of Grantham’s face. He thought of Hendricks’ eyes when he’d said “this never happened.”

He wrote back in his neatest script.

Dear Captain,

Thank you for your letter. I’m afraid I do not recall anything out of the ordinary regarding small arms on Bougainville beyond the usual wear and tear.

Respectfully,

Raymond L. Beckett

In 1967, a journalist tracked him down, having dug through old after-action reports and found the phrase “unauthorized but effective field expedient modification of an M1 carbine.”

The man showed up at the shop, notebook in hand, tape recorder in a bag.

“Mr. Beckett,” he said, “I’m writing a series on unsung innovations from the Second World War. The Marines at Bougainville—”

Beckett wiped his hands on a rag.

“I don’t have anything for you,” he said.

“Sir, I’ve seen your name in—”

“You need something fixed?” Beckett asked, nodding at the empty hands. “Otherwise I’ve got work.”

The journalist left with an empty notebook and a quote that said nothing.

In 1981, the Marine Corps’ official history of the Bougainville campaign came out in a thick, serious book.

One paragraph, halfway down a page near the back, mentioned “unofficial but effective modifications to M1 carbines carried out at unit level to extend practical engagement distances against Japanese snipers.”

No names.

Beckett bought the book.

He put it on a shelf in his living room.

He never opened it.

Why the silence?

Why turn down the chance to tell a story that would have made him, if not famous, at least a name in a footnote?

Because, in his mind, he hadn’t done it for the story.

He’d done it because men were dying.

He’d looked at a tool, seen that it wasn’t doing the job someone said it could, and fixed it the only way he knew how.

The Corps got the benefit.

The rulebook stayed the same.

He took his payment in the form of nine men who never fired another shot and a couple dozen who lived who might not have otherwise.

For a craftsman, that was enough.

Beckett died in 1994, in a small house not far from where the coal dust still settled on cars every morning.

His obituary ran three paragraphs in the local paper. It mentioned his service in the Marine Corps, his long career as a gunsmith, his wife, his children, and his grandchildren.

It did not say a word about the hacksaw.

It did not mention nine Japanese snipers.

It did not talk about Bougainville or the three inches of steel that regulations said he wasn’t allowed to cut.

Somewhere, in a misfiled logistics report from 1944, there is probably still a paragraph talking about a carbine that didn’t match any known model and a captain who chose not to ask too many questions as long as the casualty reports kept dropping.

Most people will never see that paragraph.

What they might see, if they look closely enough at stories like his, is the space between what a manual says and what a battlefield demands.

Sometimes that space is measured in yards.

Sometimes it’s measured in inches of barrel.

Sometimes it’s measured in the willingness of one man, waist-deep in mud, to trust his hands more than the rulebook and risk everything to make the cut.

THE END

News

CH2 – What Rommel Admitted in Private After Patton Outsmarted His Counterattack Plan

The first word out of Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s mouth wasn’t in German. “Unmöglich,” he said. Then, in English—spitting…

CH2 – How a 20-Year-Old’s ‘Human Bait Trick’ Killed 52 Germans and Saved His Brothers in Arms

On the morning of February 1st, 1944, the world narrowed down to a lump of frozen earth, a too-heavy…

CH2 – American Engineers Test Captured Japanese Type 100 Submachine Gun — Then Realized Why It Failed

March 1944 Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland The crate looked like every other crate that passed through the ordnance receiving…

CH2 – Sniper’s “Stupid” Mirror Trick — The Secret That Tripled His Speed

Metz, France November 3, 1944 — 6:47 a.m. The bakery had died before dawn. Its front wall was half…

CH2 – Sniper’s “Stupid” Mirror Trick — The Secret That Tripled His Speed

February 14, 1943 0347 hours North Atlantic, 600 miles east of Newfoundland The SS Robert Perry broke in half in…

CH2 – How One Metallurgist’s “FORBIDDEN” Alloy Made Iowa Battleship Armor Stop 2,700-Pound AP Shells

November 14th, 1942 Philadelphia Navy Yard, Pennsylvania The projectile hung in the cold air like an accusation. A 2,700-pound steel…

End of content

No more pages to load