They Banned His “Hollow Log Sniper Hide” — Until It Dropped 14 Germans

At 8:47 a.m. on September 18th, 1944, Private First Class Eddie Brennan lay inside a dead tree and wondered if this was the stupidest thing he’d ever done.

The Herkin Forest pressed in around him—black trunks, gray fog, wet earth. He couldn’t see any of that directly. What he saw was a circle of the world, no bigger than a dinner plate, framed by the jagged rim of a knot hole.

Forty, fifty, sixty yards out, shapes moved in the fog.

Thirteen Germans, by his count.

They were setting up an MG42 position directly astride the forest trail where Baker Company was due to walk in two hours.

Eddie watched them work.

The felwebel, a scar across his cheek like a knife slash in raw steak, pointed and jabbed, placing men the way a foreman placed steel beams. The gun crew unfolded the tripod with practiced speed. The barrel assembly came out of its case. Ammunition belts—neat, shiny—were laid out in loops within arm’s reach.

They looked like they’d done this before.

They looked like they expected nothing to interrupt them.

Eddie’s Springfield rested on a leather pad under his shoulder, muzzle pushed just far enough into the knot hole that the scope had a clear line. He could see the feldwebel’s scar, the grease on the MG42’s feed tray, the stubble on a young private’s jaw.

His orders were clear.

Observe and report.

Do not engage unless compromised.

From where he lay, the orders looked an awful lot like a death sentence—for somebody else.

Three thousand miles away and eight years earlier, a fourteen-year-old boy in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, stared at a broken crane and understood, for the first time, that when systems failed, people paid.

Bethlehem Steel loomed over Johnstown like a steel cathedral. The rolling mills roared day and night. The blast furnaces lit up the night sky with orange flame. Men went in on two feet and came out…the way they came out.

Eddie’s father had worked the furnaces until the day a ladle chain snapped and dumped fifty tons of molten metal halfway across the bay.

Three men died outright.

Two more, including Brennan’s father, lived long enough to wish they hadn’t.

They said later some engineer had miscalculated the load on the chain. Or maybe someone had signed off on a maintenance log they shouldn’t have. Either way, the math had been wrong, and his father’s legs had been in the way.

After that, there wasn’t any question about who was bringing home money.

At fourteen, Eddie went to work in the salvage yard.

It was a world built out of other people’s failures. Twisted I-beams. Cracked housings. Motors that had seized under load. Machines that had done their job until something finally snapped.

His job was to strip them down and find what was still worth something.

He learned to see value in wreckage.

He learned to find the tiny stress fracture in a support beam that told you why a structure had collapsed. The hairline crack in a casting. The one gear tooth that had sheared in a gear train.

On Saturdays, when the yard was quiet, he slung his grandfather’s .22 over his shoulder and walked out into the bony wasteland of the strip mines east of town.

Groundhogs were good practice.

They were cautious. They sat up for a second to look around and then dropped. If you rushed the shot, you missed. Ammunition cost more than he made in an hour. Missing wasn’t an option.

So he lay still in the tall grass for hours, watching. Waiting.

He learned to let the whole world shrink down to the ring of his front sight and the inch or two of space between it and a small patch of fur.

Sometimes, when the mine police rode past on their rattling trucks, he lay even stiller—back pressed against a slag pile, skin prickling with fear, rifle flattened along his side.

He got good enough at it that men in uniforms looked right at him and saw nothing.

What he took from those days wasn’t so much that he could shoot a small target at long range. It was that if you understood how things worked—machines, men, eyes—you could do more with less.

The mine cops looked for kids who scrambled and ran.

They didn’t look for a kid who became part of the slag.

Systems had habits.

Once you knew the habits, you knew where the weaknesses were.

The Army recruiter who came to Johnstown in December 1942 had a grin like a politician and a stamp that hit paperwork with brutal finality.

“What do you know how to do, son?” he asked, pen hovering.

“I can shoot,” Eddie said. “And stay still.”

The recruiter laughed.

“Good enough for infantry,” he said, stamping “RIFLEMAN” on the sheet.

By September 1944, Eddie had survived North Africa, Sicily, and Normandy. He’d seen enough combat to understand that survival was as much about luck as skill.

But luck had a way of favoring people who paid attention.

In the hedgerows of Normandy, somebody had noticed that PFC Brennan seemed to make his shots count. Eight Germans in three days, all over three hundred yards, all single shots.

They’d pulled him aside and handed him a Springfield with a Unertl scope.

“Keep doing what you’re doing,” the lieutenant had said.

He’d tried.

But the Hürtgen Forest didn’t care about what he’d done in hedge country.

The forest ate men who did what the manual said.

American doctrine said snipers stayed two to three hundred yards behind the line, in slightly elevated positions, providing overwatch and selective fire.

Herkin laughed at that.

The trees grew thick and close, trunks as wide as truck tires, branches tangled overhead. The canopy blocked light, and sometimes sky, and nearly all long sightlines.

At twenty yards, you could lose a squad.

At fifty, you could lose a company.

The Germans had spent months turning that patch of woods into a killing ground.

Interlocking machine-gun nests dug into earth and logs so thick American mortars just chewed bark off the front. Mines laid along the obvious trails, then along the non-obvious ones. Artillery pre-registered on every likely clearing. Snipers up in platforms in the branches, invisible until you moved.

The American answer was straight out of the book:

Advance company-strength along the trails. Probing fire. Call artillery when you met resistance. Clear each strongpoint in turn.

The American results were straight out of a nightmare.

In three weeks, Eddie’s battalion had lost ninety-seven men.

He knew the number because he kept a list.

Not for morbid curiosity. Not to wallow.

He wanted the names to mean something.

PFC Tommy Adler from Brooklyn. Shot through the neck trying to flank a bunker, air bubbling through blood with every ragged attempt at a breath.

Sergeant Frank Yablonsky from Detroit. One step and a shoe mine turned his leg into meat. The medic got to him in time to hear his last joke.

Corporal James Harper from San Francisco. Hit by tree-burst artillery—shells that detonated in the canopy and sent jagged steel down like rain. Eddie remembered the sound more than the sight: a high whistle turning into a crashing, the thunk of shrapnel hitting trunks.

Every night, when they dug in, he scratched another name into the margins of his little notebook.

Every morning, he got back up and watched more men walk into a forest that didn’t care about their plans.

Snipers were supposed to make that better.

In Herkin, the doctrine turned them into spectators.

From two hundred yards back, all Eddie saw was fog and trunks and the occasional flash of muzzle fire. He could fire into that mess, but he might as well have been shooting at nothing.

He went to Captain Holloway after Harper died.

The captain sat on an ammo crate in the command post, map laid out on his knees. Holloway was one of those regular Army officers who wore exhaustion like a uniform item—perfect crease in his trousers, three days’ growth on his jaw, eyes red.

“Sir,” Eddie said, “the doctrine doesn’t work here.”

Holloway looked up.

“Oh?” he said, one eyebrow rising. “And what should we be doing instead, PFC Brennan?”

“I need to get forward,” Eddie said. “Deep in their lines. Find where they’re setting up before we walk into it. I can’t see anything from back here.”

Holloway stared at him like he’d just suggested switching sides.

“Forward of the advance?” he repeated. “That’s suicide, Brennan. And it violates every principle of sniper employment.”

“Sir, they’re killing us with machine-gun ambushes,” Eddie said. “If somebody doesn’t get ahead of them, they’re just going to keep doing it. Thirty men a week at least.”

“We advance as a unit,” Holloway said. “We coordinate. We do not send one man off to play cowboy. You follow orders.”

“Yes, sir,” Eddie said tightly.

Holloway went back to his map.

Back in his foxhole that night, Eddie sat with his back against the dirt, rifle across his knees, and did the math.

Thirty men this week. Thirty next. Thirty the week after.

Four weeks to rotation.

One hundred and twenty more names in his notebook.

He stared into the dark and thought about his father.

Thought about the ladle chain that had snapped because someone somewhere had decided the system was “good enough.”

Sometimes the system kills you.

Sometimes you break the system.

The next morning, he tried a different route.

First Sergeant Patrick McKenna was a coal miner from West Virginia who had survived Kasserine Pass by not being stupid enough to do what the colonel told him.

He had a voice like gravel and a way of listening that made you feel like your words weighed something.

Eddie laid it out for him. The doctrine. The casualties. The idea.

McKenna poked a finger into his chest.

“You saying you can get out there, by yourself, and not get dead?” he asked.

“Yes, First Sergeant,” Eddie said.

“You saying you can sit still for twelve hours in Kraut country and not sneeze?”

“Yes, First Sergeant.”

“You saying you can get back after?”

Eddie hesitated a fraction.

“Yes, First Sergeant,” he said.

McKenna’s eyes narrowed.

“Then you take it to S2,” he said. “And you don’t mention my name.”

Lieutenant Robert Hayes, battalion intelligence, looked like he should have been playing tennis on weekends, not parsing German order of battle charts.

Harvard educated. Smooth hands. Hollow eyes.

There was a time he’d believed wars were chess. He’d since learned they were bar fights in the dark.

He studied Eddie’s map, tracing with a finger.

“Three hundred yards into German-held forest,” he said. “Alone. No radio. No guaranteed exfil route.”

“Yes, sir,” Eddie said.

“Can you infiltrate without being detected?” Hayes asked.

“Yes, sir,” Eddie said.

“Can you survive twelve hours alone out there?” Hayes asked.

“Yes, sir.”

“Can you get out if it goes sideways?”

Eddie lied a little smoother this time.

“Yes, sir.”

Hayes looked at him for a long moment, weighing something.

The S2 tent smelled of canvas and damp. Outside, somebody was boiling coffee that smelled like it had died twice.

Finally, Hayes opened his map case and tapped a grid square.

“Baker Company will advance down this trail tomorrow at eleven hundred,” he said. “Intelligence suggests German positions along this ridge. I need eyes on. Location. Strength. Weapons. You go in tonight. You leave before dawn. You observe. You come back.”

His gaze hardened.

“You do not engage,” he said. “Unless compromised. If you’re captured, you’re a private out freelancing. Nobody ordered you to do anything. Understood?”

Understood.

If it worked, Hayes had a success story.

If it failed, he had plausible deniability.

“I understand, sir,” Eddie said.

The lieutenant’s mouth twitched in what might have been a flicker of guilt.

“Get some sleep,” he said. “You’ll need it.”

Eddie didn’t.

He went out into the trees instead.

The forest was different at night.

It felt closer. Alive in a way daylight hid.

Eddie moved along the edge of the American perimeter, the silhouettes of foxholes and saddles of helmets outlined against the faint glow of cigarette embers.

He wasn’t sure what he was looking for, not exactly.

He just knew the regular options were all wrong.

He couldn’t dig. Fresh earth screamed “man here.”

He couldn’t go up in the trees. The German snipers already owned the branches, and they’d had months to build platforms and lanes.

If he wanted to get forward and stay alive, he needed something that had been there before anybody started wearing uniforms.

Half an hour later, he found it.

The oak lay on its side in a mild depression, its roots like fossilized tentacles reaching into the air. The trunk, maybe three feet in diameter, had rotted from the inside. Years of water and bugs and fungi had hollowed it out, leaving a tunnel just wide enough for a man to worm his way in.

To anyone walking past, it was just one more dead log in a forest full of them.

Eddie crouched and peered inside.

The smell hit him first—damp rot, mushrooms, rodent droppings, the cold, sour scent of old wood. The interior was soft where the rot had eaten the heart out of the tree. The outer ring was still solid, bark hanging in strips.

Knots showed as dark, oval holes in the surface.

One of them, facing toward the faint trace of the German lines, was the size of a kid’s fist.

He lay down and rolled his shoulder against the log, imagining the angle.

If he crawled in feet first, scooted up until his chest was near that knot, and braced his elbows just so, he could get his rifle’s scope right behind that opening.

He tried sitting back, then stepped away and circled the log.

From twenty yards, it looked like a log.

From ten yards, it looked like a log.

Up close, nose almost brushing the bark, he could see the slight disturbance where he’d scraped away moss. That would be gone by morning dew.

Good enough.

He went back to his foxhole, packed his kit—a rubberized poncho to lay down inside and keep the rot off his uniform, canteen, K-ration, entrenching tool he probably wouldn’t use, forty rounds of .30-06—and tried to close his eyes.

At 0315, he was up again.

Two scouts from recon, Privates Angelo and Sanchez, met him at the line.

“You sure about this, Brennan?” Angelo whispered.

Eddie shrugged.

“Sure as I’m gonna be,” he said.

They moved through the trees, slow and careful, stepping where he stepped.

The log loomed out of the fog, a darker shape against dark.

“You’re going to die in there,” Angelo muttered. “You know that, right?”

“Probably not today,” Eddie said.

He slid in feet first.

The inside was narrower than he’d thought. His shoulders rubbed both sides. Beetles scuttled. Something furry—rat, maybe squirrel—scrambled past his hand and squeezed out the far end.

He pulled the poncho under his chest, laid the Springfield along it, and wormed forward until the knot hole aligned with where he knew the trail would be.

He pushed the rifle forward until the scope sat just behind the hole.

The field of view snapped into place.

He could see sixty yards of the forest in front of him—trail, logs, low rise—wrapped in fog.

Perfect.

He wriggled his hands into position, one on the stock, one under the forestock, settled his cheek against the cold wood.

His left leg went numb first.

By 0600, he couldn’t feel either.

He kept breathing.

Kept watching.

Dawn came slowly in the forest. Not so much light as a lightening—shadows losing their edges, fog shifting from black to gray.

At 0847, he heard them.

Boots. Metal clinks. Low voices in a language he’d learned to recognize by tone if not words.

Thirteen of them, by the time he finished counting.

They spilled into his field of view like actors hitting their marks.

The feldwebel’s scar showed white against his stubble. The MG42 tripod legs clicked into place in the dirt. The gunner lifted the barrel with both hands, sliding it into the cradle with care that looked almost reverent.

They were setting the gun in a shallow depression with a clean arc covering the trail, less than a hundred yards from where the first Americans would appear in a little over two hours.

Eddie watched their hands more than their faces.

Ammunition boxes popped open. Belts came out. One soldier stacked spare barrels in a neat line.

These men knew exactly what they were doing.

He knew what that gun could do.

Twelve hundred rounds a minute—more, if the crew was good.

He knew, because they’d all been told, that Baker Company had a hundred and forty-three men.

If those men walked into this gun, maybe half would walk out. Maybe.

The rest would be names in somebody else’s notebook.

His finger twitched on the trigger.

His orders sat heavy in the back of his head.

Observe. Report. Do not engage unless compromised.

Captain Holloway’s voice, flat and tired: “We need intelligence, not cowboys.”

He adjusted his position half an inch to ease the ache in his shoulder.

The log creaked.

One of the Germans turned his head.

Eddie stopped breathing.

The kid—he couldn’t have been more than nineteen—stared directly at the log.

Six seconds. Seven. Eight.

Then he scratched his cheek, turned back to stacking ammunition, and said something to his buddy that made him grin.

Eddie let out his breath in a slow sigh through his nose.

He could feel his heartbeat in the rotten wood under his cheek.

He watched the Germans finish setting up.

At 0945, one of them walked straight toward the log.

Eddie’s body went still in a way that had nothing to do with discipline and everything to do with raw animal fear.

The soldier stopped six feet away, unbuttoned his fly, and relieved himself into the ferns.

Steam rose from the damp earth.

He finished, buttoned up, and walked away.

Eddie thought, not for the first time that morning, that God had a dark sense of humor.

At 1015, he heard Baker Company.

Sound in the forest traveled strangely. The canopy muffled some, magnified others.

He picked out the familiar noises—murmured commands, gear rattling, the metallic clack of an M1 bolt being eased forward.

They were close. Close enough that if he yelled, somebody might hear.

If he yelled, somebody else would, too.

He brought his eye back to the scope.

The MG42 sat on its tripod like a predator at rest. The gunner adjusted the traverse and elevation wheels, sighting down the barrel, getting his lanes just right.

The assistant gunner fed a belt into the feed tray and draped the rest lovingly.

They were ready.

He knew the plan Baker Company had been briefed on. He’d studied the map the night before. Forest trail, push across the ridge, link up with Charlie on the far side.

He knew the men.

He’d shared coffee with Adler the week before. Had listened to Yablonsky talk about his wife’s cooking. Had traded one of his cigarettes for a roll of Harper’s precious stateside gum.

He did the math.

Thirteen Germans. One MG42. One rifle. One man inside a log.

Observe and report.

Or break the rules.

Four pounds of pressure on the trigger.

He peeled off a breath, held it, and squeezed.

The Springfield’s report was a whip crack in the muffled forest.

The machine gunner’s head snapped back. For an instant, his features evaporated in a pink mist. His body dropped out of sight behind the MG42’s shield.

Everything froze—for exactly one heartbeat.

Then time snapped back.

The assistant gunner lunged for the weapon.

Eddie’s bolt came back in a smooth, practiced motion. A spent casing spun off into the darkness behind him. His hand slid forward, a fresh round slid home, the bolt went down.

Second shot.

The assistant gunner folded over the receiver, arms flung wide.

The ammo belt hung from his hand, draped over the dead gunner.

Two down.

The Germans stared, caught in that moment between confusion and reaction—the brain’s slow acceptance that one of the people a few feet away is now a sack of meat.

The feldwebel was the first to recover.

He shouted something guttural and urgent, flinging his arm toward the ridge line in a snapping gesture.

Eddie’s scope moved with his hand.

The radio operator, twenty yards behind the gun, scrambled for his handset.

Eddie caught the glint of the metal in his peripheral vision, swung, and squeezed.

The operator dropped onto his pack, one hand still reaching.

Three.

Rifle fire erupted.

Not from Baker Company. From the Germans.

They fired at where they thought shots should come from—trees, the ridge, a stand of brush to the right.

Nobody shot the log.

Yet.

Eddie worked the bolt again.

A rifleman popping up from behind a stump presented a shoulder. The shot took him through the collar bone, slammed him back.

Four.

One of the younger Germans, eyes wild, spun around.

He’d seen the radio man fall. Seen the spray of dust halfway between the line and the log. His mouth opened.

“Da drüben—!”

Eddie had him in the scope already.

Five.

The kid crumpled, the syllable truncated into a wet grunt.

The German fire shifted, almost as if the bullets themselves could sense the line of Eddie’s shots.

Rounds tore through the bark over his head.

The log shuddered.

Splinters rained down on his helmet, stinging the exposed back of his neck.

He flattened himself, chin in the rot, fingers instinctively curling in.

The volley went on for five seconds, maybe ten.

Then it stuttered and stopped.

Gunfire is coordinated when people are shooting together at something they can see.

Shooting at a log on faith burns through nerve and ammunition faster than most people can maintain.

The feldwebel made the call Eddie would have made in his position.

He yelled for withdrawal.

The remaining Germans began to peel back in twos, one firing, one bounding, then swapping.

It was a good drill, well executed.

It was also exactly the kind of pattern Eddie had practiced on groundhogs—learn the rhythm, find the holes.

He slid his elbows under him again, ignoring the needles of pins-and-needles fire in his numb legs, and came back up on the scope.

A soldier in mid-bound, half-turned to fire, chest exposed.

Six.

Another, backing toward the trees, muzzle flashing.

Seven.

The feldwebel himself, moving in a low crouch, head swiveling, professional.

Eddie led him and took the shot, trusting the math.

Eight.

The man went face-first into the loam.

Somewhere in the chaos, another German went down in the blur of motion and smoke.

Nine. Probable.

The last few vanished into the trees.

Eddie kept his eye on the scope until his vision blurred and the only things moving were leaves.

He counted to sixty in his head.

Nothing moved.

He eased himself back.

His legs didn’t feel like they belonged to him. They were numb up to mid-thigh, feet pins and needles. Some part of his brain noted this fact dispassionately and filed it under “deal with later.”

Getting out of the log was harder than getting in.

He pulled himself backward on his elbows, bark scraping his helmet, rotten wood dragging against his jacket.

When he finally slid out into the open air, the forest felt too big. Too bright.

His legs folded under him. He sat with his back against the log, rubbing feeling back into his calves with both hands.

He smelled cordite and sap and old damp wood.

He smelled German blood, metallic and sharp.

He heard Baker Company coming, closer now—different cadence to their movement, different weight.

They popped into view on the trail a few minutes later, rifles at low ready, uniforms damp.

Lieutenant Strickland—a thin-faced man with fatigue settling into his bones—stopped dead.

“What the hell—” he started, then took in the scene.

The MG42. The bodies around it. The trails of spilled ammunition. The dark smears in the dirt where men had tried, briefly, to get away.

His gaze traveled slowly from the carnage to the log to the man sitting against it with a Springfield across his knees.

“Brennan?” he said.

“Sir,” Eddie said.

Strickland walked to the machine gun, stood behind it, sighted down its barrel along the line of the trail.

His jaw clenched.

He walked back.

“What happened?” he asked.

“They were setting up an ambush, sir,” Eddie said. “I stopped it.”

“You were supposed to observe and report,” Strickland said.

“Yes, sir.”

“Not engage.”

“Yes, sir.”

“How many?”

“Eight confirmed, sir. One probable. Five got away.”

Strickland looked back at the trail his men had just marched down.

“I’m supposed to dress you down for disobeying orders,” he said quietly. “Captain Holloway’s going to want your head.”

“Yes, sir,” Eddie said.

Strickland unsnapped his canteen, took a swig, then offered it to him.

“You also just saved my company,” he said.

Eddie took the canteen. The water tasted like metal and chlorine, and something like relief.

“Just doing my job, sir,” he said.

Strickland barked a humorless laugh.

“That’s not in the job description,” he said. “But it ought to be.”

He keyed his radio.

“Baker Six to battalion,” he said. “Contact at grid Echo Seven. Enemy MG position neutralized. Multiple KIA. Requesting instructions.”

The reply came back after a pause full of static.

“Baker Six, send PFC Brennan to Battalion HQ immediately,” Captain Holloway’s voice said.

Here it comes, Eddie thought.

The battalion command tent was a sagging cathedral of canvas and mud.

Maps hung from strings. Radios hissed. A typewriter clacked in one corner, spitting out orders that would be obsolete by the time the ink dried.

Captain Holloway stood just outside, arms crossed, jaw working.

Lieutenant Hayes was there, hands jammed into his pockets, looking like someone who’d been told a test he’d written just got somebody killed.

First Sergeant McKenna leaned against a tent pole, cigarette unlit between his fingers, gaze flat.

“Brennan,” Holloway said as Eddie approached. “You disobeyed direct orders.”

“Yes, sir,” Eddie said.

“You engaged enemy forces after being explicitly told to observe only.”

“Yes, sir.”

“You operated alone, forward of the line, without authorization, and risked compromising ongoing intelligence operations.”

“Yes, sir.”

“You also neutralized a machine gun position that would have turned Baker Company into hamburger,” Holloway said.

He pulled a folded map from his pocket, smoothed it on a field table, and jabbed a finger at a spot.

“That trail looked like good terrain to staff officers in a tent,” he said. “That gun was going to prove them wrong.”

Hayes stepped in.

“Sir,” he said, pointing, “we’ve seen this pattern three times this week. Germans establish MG positions along predictable approach routes. They have the forest registered. They know where we’re going to be before we do. These ambushes have been responsible for sixty percent of our casualties in this sector.”

He flipped through a file and pulled out a sheet.

“Forty-two men dead in three engagements we walked into blind,” he said. “Brennan just took one of those pieces off the board before it could fire.”

Holloway’s eyes flicked to the list.

On some level, Eddie knew those names were already in his notebook.

He stared straight ahead.

“How did you find it?” Holloway asked him.

“Infiltrated forward under darkness, sir,” Eddie said. “Found a hide. Waited.”

“A hide,” Holloway repeated. “In a rotten log.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Alone.”

“Yes, sir.”

“For seven hours.”

“Closer to seven and a half, sir.”

Holloway shook his head as if trying to dislodge the image.

“That’s insane,” he said.

“It worked,” Eddie replied quietly.

McKenna snorted.

“Sir, with respect, what’s insane is doing the same thing and hoping the Germans forget their own terrain,” he said.

Holloway shot him a look.

“That’s not how this army works, Sergeant,” he snapped.

“Maybe it should be,” McKenna said.

Silence settled, dense as fog.

Hayes coughed softly.

“Sir, I gave him permission to infiltrate and observe,” he said. “He exceeded his orders, yes, but the result speaks for itself. If we hammer him for this, what message does that send?”

“That initiative gets you court-martialed,” McKenna said. “That you’re better off letting your buddies die than doing something about it.”

Holloway paced, boots squelching in the mud.

“If I let this stand, every sniper in Third Army is going to think they can go off and play one-man war,” he said. “No coordination. No control. Just a bunch of cowboys with scopes.”

“Or,” McKenna said, “we get a bunch of kids who give a damn about keeping their friends alive and have the guts to do something about it.”

Holloway stopped pacing.

He looked at Eddie.

“You understand you should be facing a court-martial right now,” he said.

“Yes, sir,” Eddie said.

“You understand that ‘I saved my friends’ doesn’t usually carry much weight in an army built on doctrine.”

“Yes, sir.”

“And you’d do it again,” Holloway said.

It wasn’t a question.

Eddie didn’t hesitate.

“If it saved American lives, yes, sir,” he said.

Holloway stared at him for a long time.

Finally, he blew out a breath like a man surrendering to gravity.

“Get out of my sight,” he said. “Report to Lieutenant Hayes for mission planning.”

Eddie blinked.

“Sir?” he said.

“If you’re going to be a cowboy,” Holloway said, “you’re going to be a supervised cowboy. Now move.”

“Yes, sir,” Eddie said.

McKenna’s mouth twitched around the unlit cigarette.

“That’s about as close to an apology as you’re going to get,” he muttered as Eddie passed.

Rumors moved faster than official orders.

By evening, word about “Brennan’s hollow log” had reached every foxhole in the battalion.

Some men shook their heads.

“How long was he in there?” one asked.

“Seven hours,” another said. “Didn’t move.”

“No thanks,” a third muttered. “I’ll take my chances in a hole I can stand up in.”

Others were less dismissive.

Staff Sergeant Marcus Wheeler from Charlie Company found Eddie after chow, sitting on an ammo crate, cleaning his rifle.

“You the log ghost?” Wheeler asked, settling down without waiting for an invitation.

Eddie looked up.

“Guess so,” he said.

“Need to know how you did it,” Wheeler said.

“Did what?”

“Picked your spot. Got there. Got out,” Wheeler said. “We been getting chewed up on the east side. Ambushes on the trails. You found a way to snake around that. I want in.”

Eddie wiped a patch of carbon off the Springfield’s bolt.

“It’s not complicated,” he said. “Germans like efficiency. Ambushes take work. You put them where they pay off—trails, road junctions, clearings. If you want to kill an ambush, you have to get there before the gun.”

“Digging in ain’t an option,” Wheeler said.

“No,” Eddie said. “They see fresh dirt, they shoot it. Trees are bad—too many eyes up there already. You need something that’s been there. Something they’ve walked past a hundred times and ignored.”

“Logs,” Wheeler said slowly.

“Logs. Rocks. Burned-out barns. Culverts. Anything natural,” Eddie said. “You find one that lines up with their likely sightline, you check it from their angle. If it doesn’t look like a sore thumb, you crawl in. Then you stay.”

“How long?” Wheeler asked.

“Until something happens,” Eddie said.

Wheeler nodded slowly.

“I got a kid,” he said. “Taylor. Farm boy. Shoots flies off the barn door for fun. Think he could do what you did?”

“Can he sit in one place for ten hours?” Eddie asked.

“He’s used to sitting in a duck blind till his butt freezes,” Wheeler said.

“Then yeah,” Eddie said. “If he can take orders from a tree.”

Wheeler grinned.

“Charlie Company pushes east day after tomorrow,” he said. “Germans been spotting for mortars from a little rise near a burned-out farm. Think you can show us where to stick him?”

“Bring your map,” Eddie said.

They spent the next hour bent over paper, trading knowledge.

Wheeler knew where the Germans had been shooting from. Eddie knew where they’d be next.

The collapsed barn foundation at grid Delta Four. A drainage ditch that cut across a likely approach. A pile of boulders on the German side of the line that nobody had given a second look.

“Pick one,” Eddie said. “Get him there before dawn. Make sure he has water. And make him pee before he goes in. You do not want to be in a hole you can’t get out of with a full bladder.”

Wheeler laughed.

“You sound like my grandma,” he said.

“Your grandma ever killed fourteen Germans from a pile of rot?” Eddie asked.

“Not that she mentioned,” Wheeler said. “But she ran a boarding house, so I wouldn’t bet against her.”

Two days later, Taylor slid into the blackened rubble of the barn.

At 0920, six Germans moved into view, one with binoculars, a wire running back to where mortars sat under camo netting.

Taylor waited until the observer called in his first correction.

Then he shot him through the eye.

Three more fell before the rest fled.

Charlie Company walked through that sector without losing a man.

The story grew legs.

By the end of September, there were a dozen “log men” in the division.

Not all of them used logs.

One wedged himself into a culvert under a road.

Another built his hide out of a latrine pit the Germans had abandoned.

One particularly deranged sergeant spent twelve hours in the wreckage of a burned-out half-track, the smell of charred metal and meat clinging to him for days afterward.

It didn’t matter what they used.

What mattered was that American fire was suddenly coming from places the Germans hadn’t planned for.

German doctrine liked neatness.

Fire here. Response there. Patterns.

Herkin started to feel messy.

In early October, a German Hauptmann named Otto Richter wrote a letter home that never reached his wife.

“All is not as it was,” he wrote, careful in his script. “The Americans have changed how they fight. Their snipers no longer sit safely behind their lines. They come forward. They lie in the ground itself. We set up our machines and they die before they fire.

“The men call this phantom ‘der Geist’—the ghost. They found one of his positions after he left. It was in a tree stump. A tree stump, Elise. It looked like every other stump in the forest. How can a man fight an enemy who is the forest?”

Allied intelligence read the letter, translated it, and filed it.

Someone in a tent somewhere underlined “tree stump” and scribbled “interesting” in the margin.

Lieutenant Hayes’ S2 section compiled their own reports.

Before September 20th, ambushes along trails had killed or wounded an average of twenty men a day in the battalion.

After forward infiltration began, that number dropped by more than half.

The numbers didn’t care about doctrine.

They just counted bodies.

Captain Holloway reluctantly forwarded Hayes’ report up to regiment.

Regiment forwarded to division.

Division, with bigger problems on its plate, let it sink into the growing swamp of suggestions, memos, and after-action reports.

No one in a position to officially change doctrine stuck their neck out.

But not everyone who mattered wore a star.

Lieutenant Colonel Marcus Webb, the battalion XO, spread casualty reports and S2 summaries on a table one rainy night and frowned at the trend lines.

“We have nineteen snipers in this battalion,” he said. “Twelve of them are crawling into God-knows-what and shooting Germans in the back. Our casualties are down. Our forward units are reporting better warning times. And the manual still says snipers sit behind the line like pretty little prairie dogs.”

He looked at Holloway, Hayes, and McKenna.

“Should we formalize this?” he asked.

Hayes pushed his glasses up his nose.

“If we formalize it, division will kill it,” he said. “They don’t like anything that smells like partisans. Men operating behind enemy lines in disguise? Summary execution if captured. There are rules about this.”

McKenna snorted smoke through his nose.

“Rules didn’t help Harper,” he said.

Holloway rubbed his temples.

“If we make it doctrine,” he said, “we own it. If a guy gets caught in a culvert and shot as a spy, his family’s going to get a folded flag and a letter from some colonel who never heard his name. If we keep it…unspoken…it stays their choice.”

“Sir,” Hayes said, “they’re already doing it. Officially or not. The only question is whether we give them guidelines or let them keep winging it.”

Webb tapped a pencil on the table.

“Guidelines,” he said. “Not doctrine. Not yet. Something anonymous. ‘Technical bulletin.’ ‘Recommendations.’ Enough to give cover, not enough to get anyone’s hackles up.”

He glanced up.

“This is how change happens in this outfit,” he said. “You don’t rewrite the book. You slip in a new page and hope nobody notices until it’s indispensible.”

Two weeks later, a mimeographed sheet circulated, folded into operations orders.

“Technical Bulletin DR-44,” it said at the top.

“Subject: Designated Marksman Employment in High-Density Forest Environments.”

It was written in that bland, bloodless language the Army uses when it doesn’t want to scare itself.

“In conditions where conventional overwatch is restricted,” it read, “designated marksmen may, at commander’s discretion, establish observation posts forward of main line of resistance, provided (a) prior approval is obtained; (b) exfiltration routes are reconnoitered; (c) communication protocols are established if practicable.”

Translation:

If you’re going to do what Brennan did, tell somebody first.

It didn’t mention hollow logs.

It didn’t mention Herkin.

It didn’t mention that the whole thing had started because a kid from a salvage yard decided he was done scratching names in a notebook.

But the snipers knew.

They passed the sheet around, smirking.

“We got our permission slip,” one of them said.

“Yeah,” another replied. “We were doing it anyway.”

On November 8th, Eddie made his twenty-third forward infiltration.

This one wasn’t in a log.

It was in a collapsed root cellar three hundred yards into German ground.

The cellar had one intact wall and three feet of overhead cover where soil and stones had settled.

He slid in before dawn, lay in the damp, and watched a rise where his gut said somebody was going to stick a mortar tube.

At 0930, six Germans showed up.

He killed four of them before the rest scattered.

It felt routine.

He went back to the line that night, mud up to his knees, and handed in his report.

The next morning, First Sergeant McKenna called him over and dropped a form in his lap.

“Silver Star,” McKenna said.

Eddie blinked.

“For what?” he asked.

“For the log,” McKenna said. “For the cellar. For every damn time you went somewhere we couldn’t see and came back with fewer Germans out there and more of our boys still breathing.”

He jabbed a finger at the form.

“Captain signed it,” he said. “Colonel signed it. Don’t get your hopes up, but it’s in the pipe.”

Division killed it.

“Insufficient documentation of actions under fire,” the typed note said.

Translation:

We’re not in the habit of giving medals to men who prove the manual wrong.

He found out in the way men in that war found out about things like that—third hand, over cold coffee.

He shrugged.

“You mad?” McKenna asked.

“Wouldn’t have minded some shiny metal,” Eddie said. “But I’m not the one who has to look at casualty reports and explain them to mothers.”

McKenna grunted.

“That’s the first time I’ve heard you sound like an officer,” he said.

“Don’t,” Eddie said. “I have enough problems.”

The Hürtgen campaign chewed on men until December, then moved on.

Strategically, it ended in a muddle.

Thirty-three thousand American casualties. Twenty-eight thousand German. A forest nobody would remember in the same breath as Bastogne or Omaha, but which had been every bit as deadly and twice as pointless.

For one battalion in one division, something else had happened.

Men had walked into fewer unseen machine guns.

They’d had more warnings, more artillery on target before the first burst of automatic fire.

They’d learned that sometimes, the only way to keep from getting killed by the system was to step out of it.

By the time the war ended, forward infiltration tactics had spread.

They showed up in other forests, under other skies. The men who used them didn’t know a private in Herkin’s hollow log had started it. They just knew somebody, somewhere, had figured out a way to make life suck a little less.

After Germany surrendered, a whole battlefield’s worth of lessons had to be sifted, sorted, and turned into manuals.

Operational analysis teams convened.

Charts were drawn.

Reports were written with titles like “Effectiveness of Small Arms Fire in Suppression of Enemy Movement, ETO” and “Sniper Employment: Deviations From EFM 23-10 and Resultant Outcomes.”

One such report, classified for a decade, had a paragraph that read:

“Unconventional employment of designated marksmen in forward concealment positions demonstrated significant tactical advantages in dense terrain. Recommend further study and incorporation into revised doctrine.”

It didn’t mention Eddie’s name.

By 1954, the Army’s sniper school had a section called “Hide Site Selection.”

The instructors in pressed fatigues and crisp boots told their students:

“Use natural features. Logs. Rocks. Culverts. Farm ruins. Think like the enemy. Get where they don’t expect you.”

They showed photographs from Herkin black-and-white prints of charred barns and fallen pines with faint circles inked around them.

“This is where the German thought you’d be,” the instructor would say, pointing. “This is where you actually need to be.”

The students took notes.

Nobody told them where the idea had come from.

Eddie went home.

The war folded itself up into trunks and footlockers and went into attics. Men put their uniforms at the back of the closet. Hung their medals where they saw them only when they went looking.

Johnstown’s mills were still going then.

The salvage yard still needed someone who knew a stress fracture when he saw one.

Eddie slid back into that world almost seamlessly. The crane’s controls were different from a Springfield’s bolt, but the principle was the same—smooth input, predictable output.

He married Helen, who’d patched up more than one soldier in a stateside hospital and who knew better than to push when his eyes went distant in the fall.

They had three kids.

He took them fishing.

He did not show them how to shoot groundhogs in a strip mine.

On some October mornings, when the leaves turned and the air got that particular wet chill that had soaked his bones in Herkin, he’d get quiet. Sit on the porch with a cup of coffee gone cold.

Helen would look at him once, then at the sky, and change the subject if anybody asked.

He never talked about the hollow log.

Never mentioned how long he’d lain in rotting wood, breath shallow, waiting for men who never knew his name to walk into his crosshairs.

When the kids asked what he’d done in the war, he said, “I was in the infantry.”

That was enough.

In 1963, a man with a briefcase and a fascination with the footnotes of history knocked on his door.

“Mr. Brennan?” he asked when Eddie opened it.

“That’s me,” Eddie said.

“My name is Dr. Alan Reynolds,” the man said, holding out a hand. “I’m a historian. I’m working on a study of sniper tactics in Europe. I wonder if I could ask you a few questions.”

Eddie looked past him, out to the street where kids rode bikes that looked different from the ones he’d seen in the forties, but not that different.

He looked back.

“You can come in,” he said. “But I can’t promise I remember much that’s useful.”

Reynolds had a copy of Technical Bulletin DR-44 in his briefcase. He had after-action reports. He had Hayes’ S2 summaries. He had one scrap of paper, browned with age, that mentioned “PFC Brennan” in a margin note.

“On September 18th, 1944, you were operating in the Hürtgen Forest,” Reynolds said, flipping through his notes. “There was an incident with an MG42 along a trail. Do you recall it?”

Eddie shrugged.

“A lot happened,” he said. “Forest. Guns. Germans. You’ll have to be more specific.”

Reynolds laid the S2 report on the coffee table.

“Forward infiltration,” he said. “Hollow log. Thirteen Germans. Machine gun position. Baker Company.”

The words lay there like dried leaves.

Eddie stared at the paper for a long time.

“Somebody wrote a lot about it,” he said finally.

“That ‘somebody’ says your actions led directly to the development of what we now call forward infiltration doctrine,” Reynolds said. “That you saved an estimated two hundred American lives, directly and indirectly, in that sector alone.”

He pulled out another sheet.

“Sniper schooling at Fort Benning teaches your methods,” he said. “They just don’t put your name on it.”

He nodded toward the report.

“You did that,” he said.

Eddie picked up the paper.

The language was dry. The numbers weren’t.

Casualties before and after. Ambushes neutralized. Warning times increased. Doctrinal shifts.

He imagined Harper’s name coming off his list and someone else’s not going on it because a kid in a log had killed a gunner.

He set the paper down.

“I didn’t want to watch any more kids die,” he said. “That’s all it was.”

Reynolds stared at him, pen poised over his notebook.

“Is there anything you want people to know?” he asked. “Something you’d say to the men learning from what you did?”

Eddie thought about that for a while.

“When the book and the ground don’t agree,” he said, “you go with the ground.”

Reynolds smiled faintly.

“I’ll quote you on that,” he said.

He did.

“The Evolution of American Sniper Doctrine, 1944–1965” was published in 1967 in a journal read by about fourteen hundred people.

It traced a line from European forests to Southeast Asian jungles, from Springfield rifles to scoped M14s, from a hollow oak in Herkin to the training ranges at Fort Benning.

In a paragraph on page seventeen, it said:

“Forward infiltration tactics were first employed ad hoc by PFC Edward Brennan of the 28th Infantry Division, who, in September 1944, established a concealed sniper position within a hollow log forward of friendly lines and successfully neutralized an enemy machine gun position poised to ambush his company. Subsequent unofficial adoption of similar techniques contributed to significant reductions in ambush casualties and ultimately informed post-war sniper doctrine.”

Outside of the small circle of men who taught and studied such things, nobody noticed.

Eddie didn’t get a copy.

He didn’t ask for one.

He died in April 1992, lungs finally giving out after too many years of steel dust and wet air.

The Johnstown Tribune-Democrat ran a four-paragraph obituary.

It mentioned he was a World War II veteran.

It mentioned he’d worked forty-seven years at the salvage yard.

It mentioned his wife, his kids, his grandkids.

It said, briefly, that he had served as an infantry sniper.

It didn’t mention Herkin.

It didn’t mention the hollow log.

There was no honor guard, no rifles fired in salute. Just a pastor saying the right things and a family lowering a simple coffin into a hole in the ground in Grandview Cemetery, overlooking the valley where Bethlehem’s furnaces had gone dark years before.

If there was a ghost there that day, it probably rolled its eyes at the idea of making a fuss.

In 2015, the Army Sniper School at Fort Benning dedicated a memorial to the evolution of their craft.

Seven bronze plaques curved along a low stone wall.

The first showed a doughboy in a trench with an iron-sighted Springfield, 1918.

The second, a Marine on a Pacific ridge, 1943.

The fourth plaque—right in the middle—showed a dark, stylized forest. A fallen log. The faint outline of a rifle barrel poking from a knot hole.

The inscription read:

“European Theater, 1944: Forward infiltration and natural concealment techniques emerge in response to dense terrain and enemy ambush tactics. Snipers begin operating in concealed positions forward of friendly lines to disrupt enemy preparations. These methods form the basis of modern hide site doctrine.”

It did not mention a name.

Names complicate clean narratives.

Half a continent away, in a quiet corner of Arlington National Cemetery, a different memorial took a different approach.

A plain granite wall bore a grid of names—soldiers whose innovations had changed the way America fought, but whose contributions had gone largely unremarked.

Down ten rows, three columns in, between a Marine who’d come up with disruptive camouflage patterns in the Pacific and a sailor who’d revised convoy routing to minimize torpedo attacks, one name was etched.

EDWARD BRENNAN

PFC, USA

HÜRTGEN FOREST, 1944

PIONEERED FORWARD INFILTRATION SNIPER TACTICS

Most visitors walked past without stopping.

Now and then, a student from the sniper course would be brought there on a field trip, bus idling in the parking lot, an instructor pointing.

“That name,” the instructor might say, “belongs to a guy who lay in a rotten log for seven hours because he thought his friends were worth it.”

The students, boys and girls from farms and cities and suburbs, shifted on their boots, hands in their pockets.

They’d heard the story in class, stripped of mud and smell.

Seeing the name made it real.

Nobody knew what Eddie would have thought about it.

Probably, he’d have shrugged and gone back to work.

In the end, that was what his whole life had been: seeing where the system was going to fail, then doing something about it, whether anybody thanked him or not.

They banned his “hollow log sniper hide” at first.

They told him it was insane. Out of line. Against everything the book said.

Then it dropped fourteen Germans, kept Baker Company off a casualty list, cut ambush deaths in one battalion by more than half, and rippled outward through the Army until men on other continents, in other wars, were sliding themselves into logs and culverts and rock piles because a private had once decided following the rules wasn’t as important as keeping his buddies alive.

That’s how doctrine changes.

Not because a board of generals decides it should.

Because somebody, someplace, writes a new rule in the only ink that matters out there: blood or the lack of it.

In Herkin, on a foggy morning in September 1944, the new rule was simple:

When the book and the ground don’t agree, listen to the ground.

THE END

News

After my husband hit me, I went to sleep without a single word. The next morning, he woke up to the smell of pancakes and a table full of food. He said, “Good, you finally get it.” But the moment he saw who was actually sitting at the table, his face changed instantly…

After my husband hit me, I went to sleep without a single word. The next morning, he woke up to…

At the divorce trial, my husband lounged back confidently and said, “You’re never getting a cent of my money again.” His mistress added, “Exactly, baby.” His mother sneered, “She’s not worth a dime.” The judge opened the letter I’d submitted before the hearing, skimmed it for a few seconds… and suddenly laughed out loud. He leaned forward and murmured, “Well… this just got interesting.” All three of their faces went pale instantly. They had no clue… that letter had already ended everything for them.

At the divorce trial, my husband lounged back confidently and said, “You’re never getting a cent of my money again.”…

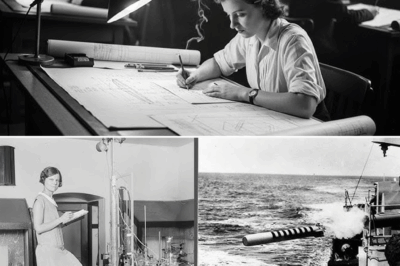

CH2 – The Female Engineer Who Saved 500 Ships With One Line of Code

By the winter of 1942, the Battle of the Atlantic sounded like a broken heartbeat. Convoys vanished off the map…

CH2 – Paralyzed German Women POWs Were Shocked By the British Soldiers’ Treatment…

On a desolate stretch of road in northern Germany, in the wet, uncertain spring of 1945, a convoy of British…

CH2 – How One Mechanic’s ‘CRAZY’ Trick Let Him Fight 50 Japanese Zeros ALONE — And Saved 1,000 Allies…

At 8:43 on the morning of August 15th, 1943, First Lieutenant Kenneth Walsh watched his wingman scatter across the…

CH2 – How One Crewman’s “Mad” Rigging Let One B-17 Fly Home With Half Its Tail Blown Off

At 20,000 feet above the Tunisian desert, the tail of All-American started to walk away. Tail gunner Sam Sarpalus felt…

End of content

No more pages to load