The SS officer’s boot stopped six inches from the boy’s nose.

Fran Weber stood in the barn doorway with his hands behind his back, palms slick against the rough crust of black bread he was hiding. He stared straight ahead at leather and dust and the small pebble embedded in the heel, and he willed his eyes to stay down, his breathing to stay steady, his voice to belong to someone older and braver than eleven.

Above him, in the loft where hay dust turned the afternoon light into pale gold, Lieutenant Robert Hayes held his breath and tried not to shake.

“Wir haben Berichte erhalten,” the SS officer said, his German crisp, educated, Berlin clean. “There are reports of an American pilot in this area.”

His voice didn’t need to be loud. It carried anyway, sharp as glass.

“Have you seen any strangers?”

Fran lifted his chin. The officer’s face was all hard angles and cold, pale eyes. Behind him, three more men in black uniforms moved through the barn, bayonets already fixed. Steel glittered, thin and hungry.

“No, Herr Offizier,” Fran said. His voice did not tremble. He was mildly astonished to hear that.

The officer studied him in a silence that lasted forever and no time at all. He took a slow step closer until Fran could smell sweat and tobacco under the starch of wool.

“You understand,” the officer said, “what happens to people who hide enemies of the Reich?”

“Yes, sir.” The words scratched his throat.

“Your father is at the Eastern Front. Your mother works the farm alone.” He tilted his head, as if observing an interesting insect. “If we found you were lying…”

He didn’t finish. He didn’t have to. The rest hung in the air like a noose.

Fran met his eyes anyway. He heard his father’s voice from another, gentler afternoon—war makes people do terrible things, but it does not change who you are inside—heard it so clearly that it might as well have been spoken in the barn with them.

“I have not seen any Americans, sir,” Fran said.

Eight feet above, pressed flat in the hay, Hayes felt his heart beat against the boards. He could see the scene below through a crack in the loft floor: the boy’s small shoulders squared, chin lifted, a smear of dirt on his cheek that made him seem even younger. Eleven years old, lying to the SS without flinching.

Why? Hayes thought, stunned. Why would he risk this?

His right leg throbbed with every pulse. It was broken in at least two places. Every small shift sent a hot bolt of pain up his spine, but he didn’t move. Couldn’t. Not with bayonets sliding into hay bales, punching through bundles with brutal, practiced jabs.

One of those bayonets punched through the bale three feet from Hayes’s head, close enough that he felt the rush of air and smelled the oil on the metal.

He closed his eyes and thought, very distinctly, This is it.

Fran did not know this would be the first of three times he would have to lie to save Hayes’s life.

Right now, there was only this moment. One boy. Four soldiers. A barn full of hay and secrets.

The officer tilted his head again, then turned to his men. “Finish searching the barn,” he snapped. “Every corner.”

They obeyed. Steel stabbed. Hay tore. Dust rose. A bayonet passed so close to Hayes’s ribs that he heard the whisper of fabric tearing as it sliced through his flight jacket.

He did not breathe.

Fran’s fingers clawed into the bread hidden behind his back. Do not look up, he told himself. Do not flinch when they stab the loft. Do not give him away.

Ten minutes stretched into ten eternities. Then, as suddenly as they had arrived, the SS were done.

“Nothing here, Herr Untersturmführer,” one of the soldiers called.

The officer gave Fran one last, probing look, then nodded to his men. “Weiter. Next farm.”

The boots turned. The trucks growled. Breath returned to the barn like air after a storm.

Fran stood in the doorway until the last trace of black uniform disappeared down the road. Then his legs folded. He slid down the doorframe and sat in the packed dirt, shaking so hard his teeth clicked.

Above, Hayes let out a strangled breath that was almost a sob. He stared at the rafters for a long moment, then forced himself to move.

“Fran?” he called down softly in bad, halting German. “Junge? Are…you okay?”

There was a pause. Then the boy laughed weakly, a small, broken sound.

“I am alive,” he called back. “So are you.”

Four weeks earlier, Fran Weber had not questioned anything.

He had believed what the posters said, what the films in Herr Müller’s classroom showed, what the town loudspeaker blared on market days. Americans were savages—faces twisted, hands grabbing, towering over dead German children with bloody boots in the propaganda reels. The narrator’s voice had slithered into every corner of his eleven-year-old mind: They know no mercy. They will burn your homes. They will murder your families. They are animals.

In class, other boys had whispered the slogans like secret passwords. At recess, they drew Americans in the dirt with horns and claws. Fran had sat in the third row, back straight, hands folded, feeling his stomach knot as bombs flashed on the classroom screen. The images weren’t real, he told himself. They were films. But the voice that narrated them sounded real enough.

In town, a poster hung near the butcher shop. An American pilot loomed over a dead German child, red block letters screaming: SIE KENNEN KEINEN RACHENDE. They know no mercy.

Fran believed it. He was eleven. What else was he supposed to believe?

At home, his mother never mentioned the films.

Maria Weber woke before dawn and worked past dusk. She scrubbed with lye soap until her hands were cracked and raw. She managed their fifty acres of barley and potatoes outside Meiningen, Bavaria, with a grim determination that brooked no argument. Fran helped as best he could—feeding chickens, hauling water, fixing the plow with hands already calloused.

His father had gone east in 1943, worn a field-gray uniform and kissed Fran on the forehead in a stiff, awkward way. His last image of him was a blur of wool and leather, a promise to return, a scent of pipe tobacco. Then the train had taken him away toward a front Fran only saw as red arrows on newsreel maps.

A few days before he left, they had fixed the barn door together. The hinges had complained. The wood was swollen from winter damp. Fran remembered the afternoon clearly: the weight of the hammer in his father’s hand, the smell of fresh-cut oak, the dust motes swirling in the sunlight like tiny planets.

“Are you scared?” Fran had asked, because fear was sitting in his chest like a stone.

His father had set the hammer down, wiped sweat from his brow, and crouched so they were eye-level.

“Franz,” he’d said—using the full name his mother favored when she was angry, but soft, not sharp. “War makes people do terrible things. It pushes them. It scares them. It…twists them. But it does not change who you are inside. Not really.”

Fran had frowned, not quite understanding.

“You remember that,” his father went on, tapping two fingers lightly against Fran’s chest. “You remember what is right. No matter what anyone tells you. No matter what uniform they wear. Understand?”

“Yes, Papa,” Fran had said, because that was what you said. But the words lodged somewhere under his ribs, waiting.

Twenty minutes. That’s how long he would get to decide what those words meant.

On March 12th, 1945, the sky over the Weber farm was crisp and cold, the late winter air carrying the damp smell of thawing earth and last year’s straw.

Fran was in the barn spreading fresh hay, the tines of the pitchfork making a steady, familiar rhythm, when he heard the engines.

He paused, fork in mid-swing. German planes had a certain whine—sharp, high, mechanical. These engines were deeper, throatier, like big cats clearing their throats.

He stepped out into the yard, shading his eyes with one hand.

They came from the west: a formation of P-51 Mustangs, silver and sleek, sunlight flashing off wings and canopies as they roared eastward. They were smaller than the lumbering German bombers, sleeker, more dangerous-looking somehow. Fran had seen pictures of them in the school posters, labeled with snarling captions.

His heart hammered. Americans.

Then the guns started.

The sound was a tearing, ripping thing, alien to the quiet rhythms of farm life—long bursts of machine-gun fire that stitched invisible lines through the sky. In the distance, somewhere nearer town, he heard the faint crump of explosions. Somewhere, something metal screamed.

One of the Mustangs peeled out of formation.

Fran’s heart lurched as the plane tilted, trailing black smoke from its underside. It spiraled, not gracefully, but in a fight against its own destruction—nose up, wing wobbling, then dipping again.

He watched it fall toward the forest west of their fields, a dark streak buried in white exhaust.

The crash came a long second or two later, dull and distant—a murmur under the receding roar of the other planes. The smoke rose in a gray smear above the trees.

They know no mercy, Herr Müller’s voice whispered in his memory. They kill children, burn villages.

Fran’s mother appeared beside him, wiping flour from her hands onto her apron. “Inside,” she said sharply, eyes on the sky. “Go, Franz.”

“But—” he started.

“Now,” she said. Her voice brooked no argument.

He went. But that night, lying in his narrow bed under a thin blanket, he couldn’t stop thinking about the falling Mustang.

The poster in town showed a pilot as a monster, looming over a dead child. The films showed them as hungrily triumphant, grinning as bombs fell. But when Fran replayed the scene in his mind—the spiraling plane, the smoke, the distant impact—it looked different.

He imagined the pilot in that cockpit. Imagined the moment the controls stopped responding, the panic when the engine coughed and died. Imagined being alone above a foreign land, knowing the sky had turned from a highway into a grave.

He was probably dead. That’s what Fran told himself. But the thought wouldn’t settle.

If not dead, then dying, he thought. If not dying…

He stared up at the dark ceiling, at the faint pattern of knots in the wood. If the pilot had survived, he might be crawling through the woods right now, bleeding, scared, and very much the enemy.

“What would I do?” Fran whispered to the dark. “What should I do?”

Between propaganda and the vague, noble ache of his father’s words, he twisted.

They know no mercy, the posters said. You remember what is right, his father had told him. The two truths sat on opposite ends of a plank inside his chest. He didn’t know which would tip.

He got his answer at dawn.

The morning of March 13th was colder. A thin frost crusted the ground, crunching under Fran’s boots as he crossed the yard. His mother was already a distant figure in the south field, bent over the soil.

He dressed quickly, grabbed a piece of hard black bread from the kitchen, dense and precious, and stuffed it into his pocket.

He told himself he was just looking. Just checking.

He walked toward the forest, following the still-visible smear of smoke that hung low over the trees. The path wound through patches of scrub and between dark trunks. The air smelled of sap and something else—metallic, acrid.

The crash site was not hard to find.

Broken branches lay snapped and flung aside like straw. A trench of churned earth and torn roots marked where the plane had plowed through before finally stopping. The wreck itself was a mangled, smoking carcass of aluminum and steel, one wing torn off, the nose buried in dirt. A star-and-bar insignia was just visible under soot and splintered metal.

There was no body in the cockpit.

He swallowed. His mouth had gone dry.

He ejected, Fran thought. He parachuted.

He scanned the treeline. Bits of white fabric were tangled high in the branches of an oak a little ways off—parachute silk, fluttering faintly in the morning breeze. Below, propped against a fallen log, was Lieutenant Robert Hayes.

At the time, Fran did not know his name. He only knew he was looking at something he had never really imagined: an American up close.

The man was young—older than Fran, but not by much, maybe mid-twenties. He wore a torn flight suit, tan stained dark with dirt and blood. His hair was plastered to his forehead with sweat. His face was gray with pain.

His right leg…Fran’s stomach churned. The leg was bent at an angle no leg should ever bend, swollen under the fabric, the boot twisted.

For a moment, the pilot looked like one of the monsters from the posters—distant, dangerous, enemy. Then his eyes fluttered open, blue and unfocused, and he saw Fran.

He tried to sit up. Pain grabbed him by the spine and yanked. He fell back with a sharp gasp, teeth clenched.

“H–Hilf,” he said, in terrible, mangled German. “Hilf…uns.” Help.

For ten seconds, Fran just stared.

Everything he had been taught screamed at him. This is the enemy. A killer. A man who would murder children, burn your home, shoot your father in the back. Run. Tell the police. Tell the SS. This is what good Germans do.

But propaganda films never showed the way a man’s hand shook when he was in pain. Posters never painted eyes like this—raw, frightened, very human. The pilot’s fear looked exactly like the fear Fran felt when SS patrols came through the village, when sirens wailed at night, when he thought about his father in the snow of Russia.

He is just a person, Fran thought, abruptly and clearly. He is scared and hurt and alone.

The pilot must have seen something change in his face because he reached out weakly, fingers trembling.

“Please,” he said again in English, the one word Fran recognized from the radio. Then, carefully, in rough German: “Bitte…nicht…SS.”

Fran flinched at the word. Everyone flinched at the word.

The SS. Black uniforms. Skulls on caps. Stories of people taken away in the night and never seen again.

Fran’s heart pounded. His father’s voice whispered: You remember what is right. No matter what anyone tells you.

He swallowed. His throat felt tight.

“Kommt,” he said finally, gesturing toward the direction of the farm. “Komm mit mir. Come and see.”

Getting Hayes back to the farm took three hours that felt like thirty.

The pilot was strong, but strength didn’t mean much when your leg was broken in two places. Every time he tried to move, pain slammed into him like a hammer. Fran slid under his right arm, small shoulder braced against the taller man’s ribs, and they started a slow, awkward journey through the trees.

They moved in tiny increments. H hop, drag, breathe. Fran took as much of the pilot’s weight as his eleven-year-old frame could bear, face twisted with effort. Branches cracked underfoot. Once, Hayes stumbled, and they both went down hard. The pilot bit down on a cry, sweat popping on his forehead.

“Wait,” Fran said, panting. “We rest.”

Hayes nodded, jaw clenched. After a minute, he looked at Fran, brows knitted in concentration. “Name?” he asked in German thickened by English. “Wie…heißt du?”

“Fron,” the boy said. Everyone in the village said it that way, dropping the “z.” Officially, he was Franz, but only the schoolteacher and his mother used that.

“Fron,” Hayes repeated carefully, rolling the unfamiliar sound around in his mouth. Then, switching languages, “I am…Lieutenant Robert Hayes.” He grimaced. “United States Army Air Forces.”

Fran didn’t understand the English string. He understood Robert. He understood Hayes. He understood the tone when the pilot added, “Danke. Thank you.”

Gratitude. Not cruelty. Not gloating.

In the propaganda films, American pilots laughed as villages burned. This man was sweating and pale and looked like he might pass out again at any second, thanking a German farm boy for not running away.

Maybe Herr Müller was wrong, Fran thought, heart going in two directions at once. Maybe the films were wrong.

They reached the edge of the Weber property just before noon. Fran could see his mother as a small, bent figure in the distance, still working the south field. Smoke rose from the farmhouse chimney. Chickens scratched near the fence.

“Stay low,” he told Hayes in German, pointing. “My mother…meine Mutter. Field. We go…Scheune. Barn.”

He led Hayes to the barn, shoulders burning from strain. Inside, the air shifted from cold to dusty warmth, smelling of old hay, manure, and the rough comfort of a place that had seen more winters than wars. Sunlight snuck in through cracks between boards, laying thin beams across the packed earth.

The ladder to the loft creaked under their combined weight. Each rung sent a spike of pain through Hayes’s leg. By the time they reached the hayloft, his face was almost as white as the parachute silk tangled in the trees.

Fran had chosen this spot because he knew its secrets. Old hay and forgotten tools made a hidden hollow near the far wall where the roof slanted down low. If you were small—or made yourself small—you could vanish.

He helped Hayes ease down into the hay. The pilot collapsed, panting, eyes shut.

“Bleiben Sie hier,” Fran said, forcing the German words to be slow and clear. “Stay here. I will bring water. Essen. Food. You understand? Stay quiet.”

Hayes managed a nod. “Versteh… I understand.”

Fran ran.

At the pump behind the house, he filled a bucket with cold water from the ground, lungs burning. He wiped his hands quickly on his pants and went inside, trying for normal.

“You’re late,” his mother said mildly from the stove, stirring a pot. “The cows are complaining.”

“Sorry,” Fran said, grabbing a cup. His voice coming out too high, too fast. “I was…ah…in the field.”

She chuckled. “You were daydreaming, that’s what you were.”

He filled the cup and carried it back toward the barn, forcing himself not to run.

Hayes drank like a man who’d been crawling through a desert. Water spilled down his chin. When he finished, he set the empty cup down carefully, as if it were the most precious thing he’d ever held.

“Why?” he asked after a moment, in English first, then again in German. “Warum?”

Fran didn’t have an answer, not one neat enough for words. He thought about the posters, the films, Herr Müller’s lectures. Then he thought about the way Hayes had said Bitte, the way his eyes had looked when he was lying under that tree, the way his father’s voice had sounded fixing the barn door.

He shrugged.

Above an American pilot. Below, a German boy. Between them, a decision that could kill them both.

The first day was chaos.

Fran snuck food from the kitchen—thin slices of bread, a scrap of cheese, once an apple he’d been saving for himself. His mother noticed.

“You’re eating more,” she said, eyeing him as he came back for a second slice of bread that afternoon.

“I am growing,” he answered, and it wasn’t even fully a lie. His wrists had been itching for weeks with the ache that came before a growth spurt.

That night, after he was sure she was asleep, he crept from his bed, moving across the creaking floorboards with the careful precision of someone who had practiced sneaking out for years. He hadn’t, but necessity made quick learners.

The barn felt different at night—quieter, more vulnerable. The animals shifted and snorted softly. The air smelled of warm breath and old straw and the faint tang of manure.

In the loft, Hayes was shivering.

The broken leg had swollen grotesquely, the fabric stretched tight. The skin above his boot was an ugly purple. Fran knew nothing about medicine. The only broken bone he’d ever seen set was a neighbor’s cow that had slipped in the mud. He’d watched as the neighbor bound the leg with boards and rope, the cow bellowing.

He remembered that now, in flashes.

“Your Bein,” Fran said, pointing. “Your leg. There is…Schmerz. Pain. Doctor?” He flipped through his thoughts, reaching for the right word.

Hayes shook his head sharply. “No doctor,” he said in German. “Doctor means…questions. Questions mean SS. SS means…” He drew a finger across his throat.

Fran’s stomach clenched. He understood.

So he did what he could with what he had.

He found old boards in a corner of the loft—pieces of broken crates, a length of wood from a discarded tool handle. Working from memory of the cow, he fashioned a crude splint. Hayes gritted his teeth, sweat beading on his forehead, as the boy slid the boards along his leg and tied them in place with strips torn from an old sheet.

“Bist du bereit?” Fran asked. Are you ready?

Hayes nodded and took a leather strap between his teeth—an old rein from a horse harness. “Mach,” he said around it. Do it.

Fran tightened the bindings carefully, eyes narrowed in concentration. The leg shifted with a wet, grinding sound that turned his stomach. Hayes’s vision went white. He didn’t scream, but a low, strangled noise escaped him, half growl, half sob.

By the time Fran finished, both of them were shaking.

Hayes reached out with a trembling hand and gripped Fran’s shoulder. “Mutig,” he said in rough German. “Brave.”

Nobody had called Fran brave before. He’d been called helpful, responsible, quiet, a good boy…but not that.

He felt something flare in his chest that wasn’t just fear.

On the second day, Fran brought a book.

He’d found it in a box under his father’s old desk: a German–English dictionary, pages dog-eared, margins scribbled with notes. His father had worked at a factory before the war, one that exported machine parts. English had been useful then.

The book felt like a bridge.

Hayes’s eyes lit up when he saw it. “Look at you,” he said, smiling lopsidedly. “Professor Fran.”

They spent an hour pointing at words, stumbling through pronunciation. Fran learned broken, leg, pain, hungry. Hayes learned safe, hide, patrol, SS. They laughed when they mangled each other’s sounds, keeping their voices low.

When Fran pointed at hungry, Hayes nodded vigorously. “Yes,” he said. “Always.”

Fran snorted. “American stomach, very big.”

Hayes put a hand over his heart. “Texan stomach,” he corrected, then, seeing Fran’s puzzlement, flipped through the dictionary until he found Texas. “My home,” he said. “United States…Texas.”

He gestured out past the barn walls as if he could see across an ocean. “Hot. Big sky. My mother’s…pecan pie.” He found the word for pie and tapped it.

Fran tried to imagine a sky bigger than the one over their fields. He tried to imagine a woman baking pies in a kitchen somewhere in America, worrying about a son she didn’t know was lying in a German barn loft with a broken leg.

It was easier to picture than the grinning pilot on the poster in town.

That night, as they squinted at the book by the glow of a lantern hooded with a rag, Hayes tapped another word.

“Doctor,” he read. “Teacher.”

He pointed to himself first, then shook his head. “I am…pilot now,” he said. “But before war, I wanted to be teacher.”

He pointed to Fran. “You? What do you want?”

Fran frowned. Nobody had asked him that. His life had always seemed mapped out in furrows and fields.

“I do not know,” he said honestly. “Maybe…farm. Maybe…” He hesitated, thinking of Herr Müller at the blackboard. “Maybe also teacher.” He added, half-grinning, “But not like Herr Müller.”

Hayes laughed softly. “Good choice.”

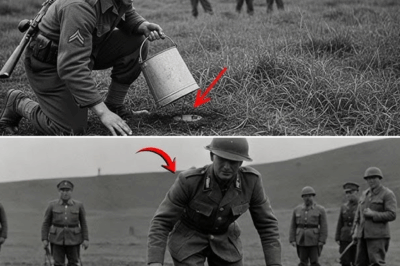

The first SS visit came on the third day.

Fran was on his way to the barn with a slice of bread in one hand and an apple in the other when he heard the sound—trucks on the road, heavy engines grinding over ruts.

He froze.

Dust rose over the hedges, and then he saw them: gray trucks, black uniforms in the back, glints of rifles.

His heart tried to punch its way out of his chest.

He shoved the bread under his shirt, the apple into his pocket, and ran.

In the loft, he burst in on Hayes with a hissed, “SS! SS kommt!”

Hayes’s eyes went wide. He nodded once, the fear in his face sharp, immediate. He flattened himself into the hay, dragging loose straw over his body, making himself as small as he could.

“Don’t move,” Fran whispered. “Don’t breathe.”

Boots thudded into the barn below. Voices barked. The language was familiar enough. The tone was not.

“We have reports,” the officer said, the same one who would later stop six inches from Fran’s nose. “An American pilot in this area.”

Fran’s feet carried him down the ladder before his mind could catch up. He landed on the barn floor, chest heaving, just as the officer stepped through the doorway.

Everything that followed—the questions, the threats, the cold eyes—would replay in Fran’s nightmares for years. But he pulled the bread from behind his back and answered as if it were simple.

“No, sir,” he said. “I have not seen any Americans.”

When the bayonet tore through the hay a few feet from Hayes’s head, the pilot felt the world narrow to the width of that steel blade. He heard it slice through his jacket, felt the sting as it grazed his skin. His lungs burned from holding his breath.

I’m going to die in a barn in Germany, he thought wildly. And my mother’s going to…

The bayonet withdrew. The soldier grunted something to his comrade. The officer said, “Next farm.”

The trucks left.

Fran waited until the last engine noise faded before he let his knees give out.

That night, when he brought soup to the loft—a whole bowl his mother had made with potatoes and a bone and every scrap she had—Hayes stared at it like it was a feast.

“Your mother,” he said carefully in German, pausing between words. “She…knows?”

Fran shook his head quickly. “No,” he said. “Secret.”

“If she knew, she would be in danger, too,” he thought. “Better she doesn’t know. Better she can deny everything if they come back.”

Hayes ate slowly, savoring each mouthful. When he was done, he set the bowl aside and looked at Fran for a long time.

“The films,” he said finally, searching for words in both languages. “The propaganda…about Americans.” He tapped his chest. “About me.” He shook his head. “Lies.”

Fran’s mouth twisted. “Lies,” he agreed.

“Germans too,” Hayes went on. “We saw films. About Germans. Also lies.”

Fran felt something shift inside him. It was like someone had opened a window in a room he hadn’t realized was stuffy.

“They lied to you about us,” he thought, stunned. “Just like they lied to us about them.”

“War is…” Hayes searched the dictionary with a frustrated huff. He couldn’t find the word he wanted. He finally made a gesture with both hands—spreading, tearing, destroying.

“Schlecht,” Fran supplied quietly. “Bad.”

Hayes snorted. “Very bad,” he agreed.

They sat together in the loft: boy and pilot, enemy and protector, sharing the same air while outside, the world tore itself apart.

Days blurred.

Fran built a routine that settled over him like a blanket: morning chores, quick trip to the barn with food concealed, school when he could go, fields, another trip to the barn. Nights were for water, blankets, checking the swelling of Hayes’s leg, changing bandages with gentle, clumsy hands.

In between, they talked.

Sometimes it was practical. “If patrol comes, you go here,” Fran would say, pointing to the tight space between the roof beams and the stacked hay near the far wall. Hayes would nod, eyes serious.

Sometimes it was language. They would pick a page at random in the dictionary and point at words: cloud, gun, cow, home. Hayes taught Fran to say Thank you and You’re welcome with a Texas drawl that made the boy laugh. Fran taught Hayes how to curse in German, which the pilot took to with unseemly enthusiasm.

Sometimes it was stories.

Hayes talked about Texas: flat land stretching forever, hot summers that made the air shimmer, the way you could see thunderstorms coming for miles. He described his mother’s pecan pie—how the crust flaked, how the filling was sweet and sticky, how he’d always burned his tongue, too impatient to wait for it to cool.

He told Fran about Betty, the girl back home with dark hair and a laugh you could hear across a dance hall. “She writes me letters,” he said, voice soft. “Tells me about school, about rationing. She hates this war. Calls it stupid. I think she’s right.”

Fran told him about the farm: about the way the fields looked under snow, about the smell of potatoes roasting in the coals, about the time he’d fallen into the pond in November and thought he’d never be warm again. He told him about his father—the firm handshake, the way he whistled when he worked, the last conversation by the barn door.

“Your father,” Hayes said one evening, the light fading through the cracks. “He would be proud of you. Very proud.”

Fran swallowed hard. “I do not remember him much,” he said. “He wrote a letter from Russia once. Then nothing.”

“He taught you what matters,” Hayes said. “You show me that every day.”

Fran looked away, blinking too fast.

That night, when he came into the kitchen, his mother pointed wordlessly to an extra loaf of bread cooling on the table. She didn’t ask why he’d been eating more. She didn’t say anything about how he lingered near the barn now, or how he started when he heard engines. She just baked more.

Some things mothers knew without being told.

The second SS patrol came on a bright, cruel morning when the war outside the farm was reaching its loudest, ugliest pitch.

This time, Fran was in the field with his mother when he heard the trucks. The sound drifted over the low hill—different engines than the American ones, familiar enough that his stomach turned to ice.

He dropped his hoe.

“Franz!” his mother called as he started to run. “Where are you—”

“Barn!” he shouted over his shoulder. “I forgot—I must—”

He didn’t finish. He sprinted.

By the time he burst into the barn, chest heaving, Hayes was already sitting up in the hayloft, head cocked. He’d heard them too.

“SS?” Hayes asked.

“Yes,” Fran gasped. “Again. Up. You know where.”

Hayes’s leg was better now—splinted and healing, though it still screamed at him with every movement. He grabbed the makeshift crutch Fran had fashioned from a broken rake handle and limped toward the narrow gap Fran had pointed out days earlier.

It was a cruel little space, created where the roof beams met the hay storage. The angle was sharp, the opening barely wide enough. Hayes sucked in his stomach, flattening himself, using his arms to wedge and pull until he was jammed into the cavity, hay pressed against his face, wood beams digging into his back.

“Don’t come up,” he whispered. “Stay below. Don’t let them see you afraid.”

Fran nodded, throat too tight to speak. He clambered down the ladder as boots stormed into the barn.

This officer was younger than the first, face hard with a different kind of tension—more anger, less patience.

“We know there is an American pilot somewhere in this area,” he barked. “We have witnesses. We will search everything. Tear this barn apart if you have to.”

Fran’s blood turned to ice. Witnesses. Smoke from the crash. Parachute silk. It was all catching up.

The soldiers spread out, bayonets already stabbing. They were more thorough this time. They didn’t just jab at random. They tore into bales, ripped open corners, climbed.

Fran listened to boots on the ladder. He watched the outline of a man rise into the loft, rifle first, bayonet gleaming. He heard hay being shoved, felt dust drift down.

Up above, Hayes pressed himself flatter, every muscle screaming. The tiny space barely allowed him to breathe. Hay scratched his cheeks. A splinter dug into his shoulder. He could hear the soldier’s boots inches away, could smell the polish on the leather.

If the man moved one more bale. If he bent down. If he sneezed.

The soldier paused. His boots turned, boards creaked. For a second, Hayes was sure those cold gray eyes would appear inches from his own.

“Nothing up here, sir!” the soldier called down.

Hayes didn’t realize he’d been holding his breath until his lungs demanded air in a panicked rush. He forced himself to take shallow sips, terrified even his breathing would give him away.

After an eternity, the boots retreated. The ladder creaked again. The officer shouted something about the next farm. The trucks left.

Fran stood in the doorway, hands fisted at his sides, until the dust settled. Only then did he let himself sag.

When he climbed back up, Hayes was still wedged in the gap, sweat streaking the dust on his face. His hands were shaking.

“I thought…” Fran said. The rest caught in his throat.

“Me too,” Hayes managed. “I thought that was it.”

He wriggled out of the hiding place, moving inch by inch. When he finally collapsed back onto the hay, he looked at Fran with fierce intensity.

“Listen to me,” he said in German, the words thick but clear. “If they come again—if they find me—you tell them I forced you. You tell them I threatened your mother. Do you understand? You say I made you. I had a gun. I…you were scared. You had no choice.”

“No,” Fran said immediately, shaking his head so hard his hair flopped into his eyes.

“Yes,” Hayes insisted. “You have to protect yourself. Your mother. You’re a kid. They’ll believe you. You tell them the American bastard made you.”

“No,” Fran repeated, voice rising. “I chose this. I chose to help you.”

Hayes stared at him. For a moment, the boy’s face looked like a stranger’s—older, harder.

Then Hayes’s shoulders slumped. A small, tired smile tugged at his mouth. “You showed more courage than I ever did in that cockpit, kid,” he said quietly. “You know that?”

Fran didn’t feel courageous. He felt like his bones were made of jelly.

But beneath the fear, there was something else. A thin, stubborn line of certainty. He might not understand the whole war. He might not understand the politics or the borders or the speeches. But he understood this: he had made his choice.

Whatever happened now, he would not undo it.

By week three, Hayes could hobble around the loft with the aid of the crutch. By week four, he could put a little weight on his broken leg without seeing stars. The pain didn’t disappear, but it receded enough that his world expanded beyond the tight circle of hay and fear.

Their conversations stretched longer.

Hayes taught Fran English phrases that weren’t in the dictionary—shoot the breeze, on the level, back home. Fran tried them out carefully, rolling unfamiliar vowels over his tongue.

“Back home,” Hayes said one evening, staring through a crack in the wall at the setting sun. “My mom’s probably in the kitchen right now, listening to the radio. Betty’s probably yelling at a newsreel. My brother’s probably trying to sneak an extra piece of pie.” He smiled at the picture in his mind.

“You miss them,” Fran said.

“Every minute,” Hayes answered. “But if I had to be stuck in enemy territory…” He shrugged. “Could’ve done a lot worse than your barn, kid.”

Fran snorted. “Our barn is famous,” he said. “Very luxurious.”

They both laughed.

Sometimes the levity cracked, and other truths came out.

One night, staring up into the dark rafters, Hayes said softly, “I bombed a town once.”

Fran turned his head. “What?”

“Somewhere in Germany,” Hayes said. “Factory target. That’s what they told us. I don’t know the name. I just know there were houses around it. Streets. Probably a school, a church, a bakery. We dropped the bombs because that’s what we’re trained to do. I watched them fall. I watched the fire.” His voice went flat. “I don’t know who lived there. I don’t know who I killed.”

Silence settled heavy between them.

“I’m sorry,” Hayes said finally. “I am so damn sorry.”

Fran didn’t know what to do with that. The films had shown American pilots laughing at such things. He’d never pictured one lying in the dark of his barn, voice cracking with guilt.

“The war made you,” Fran said carefully, searching for the words. “Not you made the war.”

Hayes let out a shaky breath, somewhere between a laugh and a sob. “You are eleven,” he said. “How are you this wise?”

Fran shrugged. He didn’t feel wise. He felt like a boy who’d been forced to grow up faster than he’d wanted.

Outside, artillery rumbled in the distance.

By week five, the war itself felt closer.

The distant thud of guns became a constant undercurrent. The ground sometimes trembled faintly. At night, the horizon to the west glowed a dull red-orange. Refugees started to pass on the road past the farm—gaunt figures pushing carts, leading thin horses, all moving east with the same weary urgency.

The propaganda on the radio grew more frantic. Announcers shouted about glorious last stands and miracle weapons. His mother turned the volume down and muttered under her breath.

One afternoon, Fran and Hayes sat side by side in the loft, backs against a beam, watching dust motes dance.

“I hear artillery,” Hayes said quietly. “Getting closer.”

“How close?” Fran asked.

Hayes closed his eyes, listening. Growing up in Texas, artillery had been something from books. Now he knew its language. “A few days,” he said. “Maybe three. Maybe less. They’re coming, Fran. Your side’s losing.”

Fran swallowed. He knew it. Everyone knew it, even if no one said it out loud.

“When they come,” Hayes went on. “I’m going to tell them what you did. About you. Your mother. About the SS. I’m going to make damn sure they know.”

Fran’s heart lurched. “No,” he said quickly. “If Germans find out, after, they will…they will say we were traitors.”

“Germany is losing the war, Fran,” Hayes said gently. “The Reich…this thing, it’s dying. You and your mother will be okay.”

Fran wasn’t sure it was that simple. Wars didn’t just stop because someone signed a paper. The hate lingered.

“What will I do when he is gone?” he wondered later, lying in his bed. The thought of the barn empty, of the loft quiet and full of only hay and his own breathing, made his chest ache.

Hayes had become more than a secret. He’d become a friend. A teacher. Proof that the world wasn’t as simple as posters and films and speeches made it out to be.

The idea of losing him—of losing that living contradiction—hurt.

When the rumble of tanks finally reached their doorstep, the feeling was as much dread as relief.

Day thirty-nine.

Fran was in the barn when he felt it first: a vibration through the boards. A low, mechanical growl that wasn’t like the whine of German trucks or the distant boom of artillery.

He went to the crack in the wall. Dust puffed in the air. Outside, in the lane, a column of vehicles was rolling into view—tanks and trucks and jeeps, draped in canvas and gear, men in olive drab uniforms perched on top.

White stars.

“Americans,” Hayes breathed, appearing at his shoulder. “That’s armor. They made it.”

Fran’s heart tried to accelerate right out of his chest. His mouth was dry.

“Stay with me,” Hayes said, squeezing his shoulder. “Stay close. We do this together.”

They descended the ladder carefully. Hayes’s leg complained with every rung, but he gritted his teeth.

Fran’s mother stood in the yard, apron dusted with flour, eyes wide as the tanks rumbled past, flattening ruts into the road. A jeep turned into their drive, brakes squealing a little. Two soldiers in dusty uniforms and helmets rode in it, rifles across their laps.

When they saw Hayes limping out of the barn, their eyes went wider still.

“Holy hell,” one of them said in English. “Lieutenant?”

Hayes straightened as much as his leg would allow. “Lieutenant Robert Hayes,” he said, voice strong despite the weeks of hiding. “United States Army Air Forces. Serial number 1847962. Been enjoying your hospitality on a German farm for the past six weeks.”

The younger soldier blinked. “Sir, you look like hell,” he said.

“Feel like it, too,” Hayes admitted. Then he turned, gesturing to Fran. “Because of this boy. Fran Weber. He hid me. Fed me. Kept the SS off my back. Saved my life.”

The soldiers’ gazes shifted to Fran. He stood in the yard with his hands fisted at his sides, chin up, trying to look less terrified than he felt. He didn’t understand all the English, but he understood saved my life from the tone alone.

One soldier lowered his rifle. The other gave him something like a salute.

“Jesus,” the older soldier murmured, looking between them. “Kid, you got some guts.”

“Sir,” the younger one said to Hayes. “We’ve got a medic with the column. We need to get you looked at. That leg…”

“I know,” Hayes said. “But first…”

He limped the last few steps to Fran and went down on one knee despite the scream of protest from his leg. He looked the boy straight in the eye.

“Fran,” he said. “Listen to me. You are the reason I am alive. You are the reason I am going home. You are the reason I get to see Betty again. You are the reason I get to see my mother. My family.”

Fran’s throat burned. Tears pricked his eyes. “You would do the same,” he said, voice shaking.

“I hope I would,” Hayes said. “I don’t know if I’d be as brave.”

He reached up, fingers fumbling at his chest. His pilot’s wings were pinned there, silver dulled by weeks of dust and sweat. He unpinned them, hands careful, almost reverent, and pressed the metal into Fran’s palm.

“These are yours now,” Hayes said. “You earned them more than I did.”

Fran stared down at them. They were heavier than he expected. Cool. Solid. Real.

“I cannot,” he whispered. “I did nothing. You—”

“You hid an enemy pilot from the SS for six weeks,” Hayes said. “You risked your life. Your mother’s life. You lied when it mattered. You fed me when your family barely had enough. You flew where it actually counts, kid. You flew in here.” He tapped his own chest. “Take them.”

Fran’s fingers closed around the wings.

He would carry them for fifty-eight years.

For now, he just nodded, unable to trust his voice.

The Americans loaded Hayes into the back of a jeep. The medic fussed over his leg, shaking his head at the crude but effective splint.

“Who did this?” he asked.

Hayes jerked his chin toward Fran. “Kid’s got a future in orthopedics if this teaching thing doesn’t pan out,” he said.

Fran didn’t know the word orthopedics. He knew the tone was half pride, half joke.

The jeep pulled away in a cloud of dust, following the column toward the rumble of the front.

Fran stood in the yard, wings pressed into his palm so hard the edges bit his skin, watching until the jeep was just a dot and then nothing.

His mother stepped up beside him. Her hand settled on his shoulder.

“What you did was dangerous,” she said quietly.

“I know,” Fran answered.

“And brave.”

He looked up at her. She was crying, tracks of tears carving clean lines through the dust on her cheeks.

“Your father,” she said, voice thick. “He would be so proud.”

Three weeks later, the war in Europe ended.

That summer, Fran’s father came home—thinner, older, eyes with shadows they hadn’t had before—but alive. The first night, after the hugs and the tears and the awkward laughter, Fran told him everything.

His father listened without interrupting, his big hands folded together so tightly his knuckles were white. When Fran finished, the man pulled his eleven-year-old son into his arms and held him for a long time.

“You remembered,” he whispered into Fran’s hair. “You remembered what is right.”

Fran Weber did not see Robert Hayes again for fifteen years.

Life filled in the spaces. He finished school in a Germany that was trying to figure out who it was now that the banners were gone and the rubble remained. He worked the farm with his father, watched new houses rise where old ones had burned, saw American occupation troops leave and new uniforms replace them.

The pilot’s wings stayed in his pocket.

He carried them everywhere, a small, solid weight against his thigh—a reminder of a barn loft, of a young American with a broken leg, of lies told for the right reasons. Sometimes, when he felt himself tempted by bitterness or the easy comfort of new kinds of propaganda, he would slip his fingers into his pocket and touch the cool metal.

In the late 1950s, Fran went back to school. He earned his teaching certificate. When he stood in front of a class of restless eleven-year-olds, he thought of Herr Müller and, just as often, of Hayes.

He never lectured about the war directly. His students learned history from textbooks and curriculum. What they learned from Fran was subtler: that every person deserved to be treated with dignity, that slogans were dangerous, that their first duty was to their own conscience.

In 1960, a letter arrived with an American stamp and handwriting that tugged at something in his memory.

Dear Fran,

I hope this letter finds you and your family well.

I think about you often. I think about those six weeks in the barn, about your bravery, about the choice you made when you were just eleven years old.

I am married now—to Betty, the girl I told you about. We have a son. His name is Thomas, and he is eleven years old, the same age you were when you saved my life.

I would like to visit, if you will have us. I would like Thomas to meet you. I want him to understand what real courage looks like.

Your friend,

Robert Hayes

Fran read it twice. Three times. Then he sat down at the table with his wife and parents and read it aloud.

They came in August.

Hayes walked with a limp—permanent reminder of a broken leg set by a German boy in a hayloft—but his smile was the same, wide and guileless. His hair was thinner at the temples. There were new lines at the corners of his eyes.

Beside him walked a woman whose laugh Fran recognized before he was introduced. Betty. Between them, slightly behind, walked a boy with curious eyes and his father’s jawline.

“Fran,” Hayes said, stepping forward, arms open.

They hugged in the farmyard like brothers.

For a moment, Fran smelled hay and dust and fear again. Then the present rushed back in—the hum of a distant tractor, the chatter of children, the clink of dishes from the kitchen where his wife and mother were talking with Betty.

“Thomas,” Hayes said, drawing his son forward. “This is Fran Weber. The man I told you about.”

The boy stuck out his hand solemnly. “My dad says you’re a hero,” he said in careful English.

Fran laughed, the sound rolling out unexpectedly. “I was just a boy who did what was right,” he replied, in English good enough to make Hayes grin.

“That’s what heroes do,” Thomas said, utterly sincere.

They spent three days together.

They walked the farm, taller now but still the same patchwork of fields and fences. Hayes and Fran climbed the ladder to the loft, a little slower this time, joints creaking in different ways.

The hay smelled the same.

“Right there,” Hayes said, pointing to the corner. “That’s where you shoved me when the SS came. And up there—that miserable little hole—I’m pretty sure I left my soul wedged between those beams.”

Thomas climbed up carefully, peering into the gap. “You hid in there?” he asked, incredulous. “Dad, it’s tiny.”

“So was I once,” Hayes said dryly. “Your mom hadn’t had a chance to fatten me up yet.”

On the last evening, they sat outside as the sun sank behind the trees, turning the sky pink and orange. The air was warm. Crickets chirped in the grass.

Thomas chased fireflies in the yard, laughing as he cupped them in his hands, then let them go.

“I never thanked you properly,” Hayes said, eyes on his son. “For giving me my life back. For giving me…this.” He gestured toward Thomas. “That boy exists because you lied to the SS.”

Fran shook his head. “I did not lie,” he said. “I just chose a different truth.”

Hayes looked at him, then chuckled.. “Still teaching me things,” he said.

“I learned from the best,” Fran replied.

He watched Thomas for a long moment, running in the fading light. “You showed me,” he said, “that the enemy is not who they tell you it is. That propaganda is poison. That people are just people, no matter which uniform they wear.”

“You knew that before you found me,” Hayes said. “You knew it the moment you decided to help instead of turn me in. Eleven years old and you understood something most adults never learn.”

They called Thomas over.

He came, breathless, face flushed with exertion.

“Thomas,” Hayes said, resting a hand on his son’s shoulder. “I want you to listen to Fran. Really listen. What he’s about to tell you is the most important thing you’ll ever learn.”

Thomas nodded, serious now.

Fran reached into his pocket.

The pilot’s wings were there, as they had been every day for fifteen years—silver dulled, edges smooth from years of his fingers running over them.

“Your father gave me these,” Fran said, holding them out. “Because he said I showed more courage than he did.”

“He was wrong,” Hayes interjected automatically.

Fran smiled. “We both flew to the same place,” he said. “We just took different paths to get there.”

“What place?” Thomas asked, brow furrowing.

“Understanding,” Fran said.

He closed Thomas’s fingers around the wings. “Understanding that the person they tell you to fear might be the person who saves you. That the enemy might become your friend. That in war, the bravest thing you can do is choose humanity.”

Thomas looked down at the wings, silver glinting in the last light. “My dad says you saved his life,” he said quietly.

“And he saved mine,” Fran said. “By showing me that everything I had been taught was a lie. By proving that kindness is stronger than hate. By being human when I expected a monster.”

Hayes’s eyes were wet. He didn’t bother to hide it.

“You kept these all this time,” he said, voice rough.

“Of course,” Fran answered simply. “They remind me of what matters.”

Years later, Fran would stand in quieter classrooms and pass on the same lesson without ever mentioning wings or SS boots or barn lofts. His students would leave believing, dimly, that slogans were dangerous and that the people they were told to hate were rarely as simple as that.

Robert Hayes returned to Germany three more times before his death in 1989. Each time, he brought family. Each time, he and Fran walked to the barn, climbed the ladder, stood in the loft, and remembered.

When Fran died in 2003, his obituary was brief.

It mentioned his career as a teacher, his family, his service to his community. It did not mention the six weeks in 1945 when an eleven-year-old boy stood in a barn doorway with bread hidden behind his back and lied to the SS.

At his funeral, in a small cemetery under a wide sky, an older man from Texas stood at the grave and told the story.

Thomas Hayes was in his fifties now, gray at the temples, his German accented but fluent.

He spoke of a shot-down American pilot who had expected hatred and found mercy. Of a boy who had been told that Americans were monsters but who had looked at a broken leg and a frightened face and seen a person instead. Of six weeks in a barn, two visits from the SS, and three lies that saved a life.

“My father told me,” Thomas said, “that heroes do not look like what we expect. Sometimes they are just eleven-year-old boys with calloused hands and brave hearts. Sometimes they are the person we are supposed to hate, choosing to love us instead.”

He bent and placed something on Fran’s grave.

A pair of pilot’s wings, silver and a little tarnished, passed from one man to another and carried across an ocean and half a century.

Above the cemetery, a plane drew contrails across the clear blue sky. The same kind of sky where Hayes had fallen in 1945. The same sky Fran had watched through barn cracks while deciding to save him. The same sky that had witnessed a choice that proved propaganda wrong—that showed a child’s conscience could be stronger than an empire’s hate, that demonstrated how six weeks of courage could echo across sixty years.

Thomas watched the contrails fade.

Then he walked away from the grave, carrying forward a story about the moment an eleven-year-old boy in wartime Germany decided that the enemy was not the man bleeding in his barn, but the hate that had taught him to fear that man.

He would tell that story back home in Texas. He would tell it to his children, to students, to anyone who tossed around the word enemy too easily.

Because in the end, that was what the German boy who hid a shot-down American pilot from the SS for six weeks had understood better than most grown men:

The enemy is not the person they tell you to hate.

The enemy is the hate itself.

THE END

News

How One Private’s “Stupid” Bucket Trick Detected 40 German Mines — Without Setting One Off

The water off Omaha Beach ran red where it broke over the sandbars. Corporal James Mitchell felt it on his…

Germans Couldn’t Believe This “Invisible” Hunter — Until He Became Deadliest Night Ace

👻 The Mosquito Terror: How Two Men and a Radar Detector Broke the German Night Fighter Defense The Tactical Evolution…

How One General’s “IMPOSSIBLE” Promise Won the Battle of the Bulge

The Impossible Pivot: George S. Patton, the 72-Hour Miracle, and the Salvation of Bastogne I. The Storm of Despair in…

They Mocked His ‘Mail-Order’ Rifle — Until He Killed 11 Japanese Snipers in 4 Days

🎯 The Unconventional Weapon: How John George’s Civilian Rifle Broke the Guadalcanal Sniper Siege Second Lieutenant John George’s actions…

“They Tried to Erase Me from the Family Celebration—But My Military Power Left Them Speechless”..

“Didn’t you used to play waitress?” Aunt Kendra’s laugh cut through the air like broken glass. I froze in the…

During my grandmother’s 85th birthday celebration, my husband suddenly leaned in and whispered, “Get your bag. We’re leaving. Don’t ask, don’t act weird.” I thought he was being dramatic… until we got in the car, he locked the doors, and his voice trembled: “There’s something really, really wrong in that house.” Ten minutes later, I called the police—and what they found sent my whole family into chaos.

During my grandmother’s 85th birthday celebration, my husband suddenly leaned in and whispered, “Get your bag. We’re leaving. Don’t ask,…

End of content

No more pages to load